Integrated Predictive Modeling of Shoreline Dynamics and Sedimentation Mechanisms to Ensure Sustainability in Damietta Harbor, Egypt

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Study Area

1.2. The Shoreline Changes

2. Methods

2.1. Digital Shoreline Analysis System (DSAS)

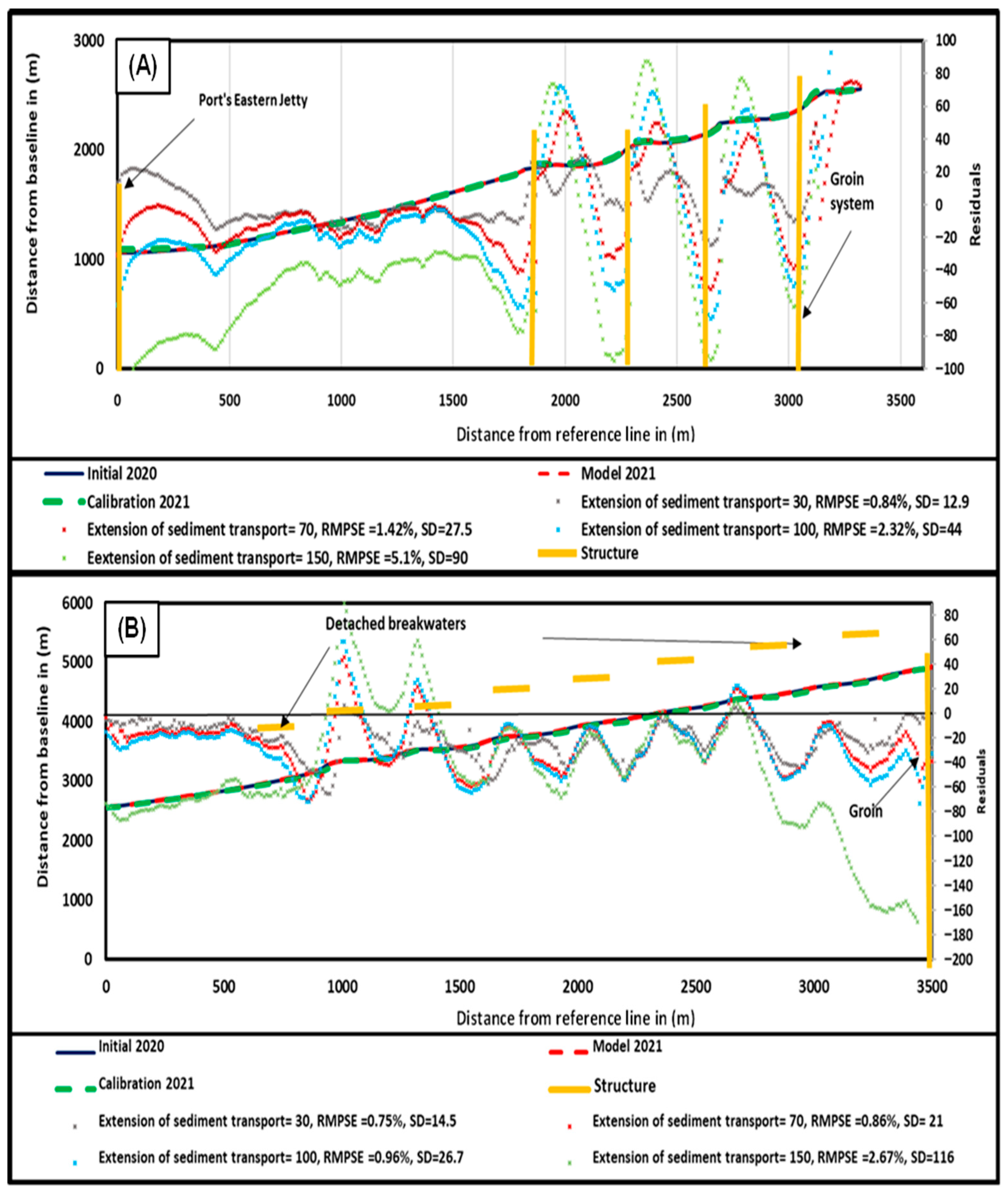

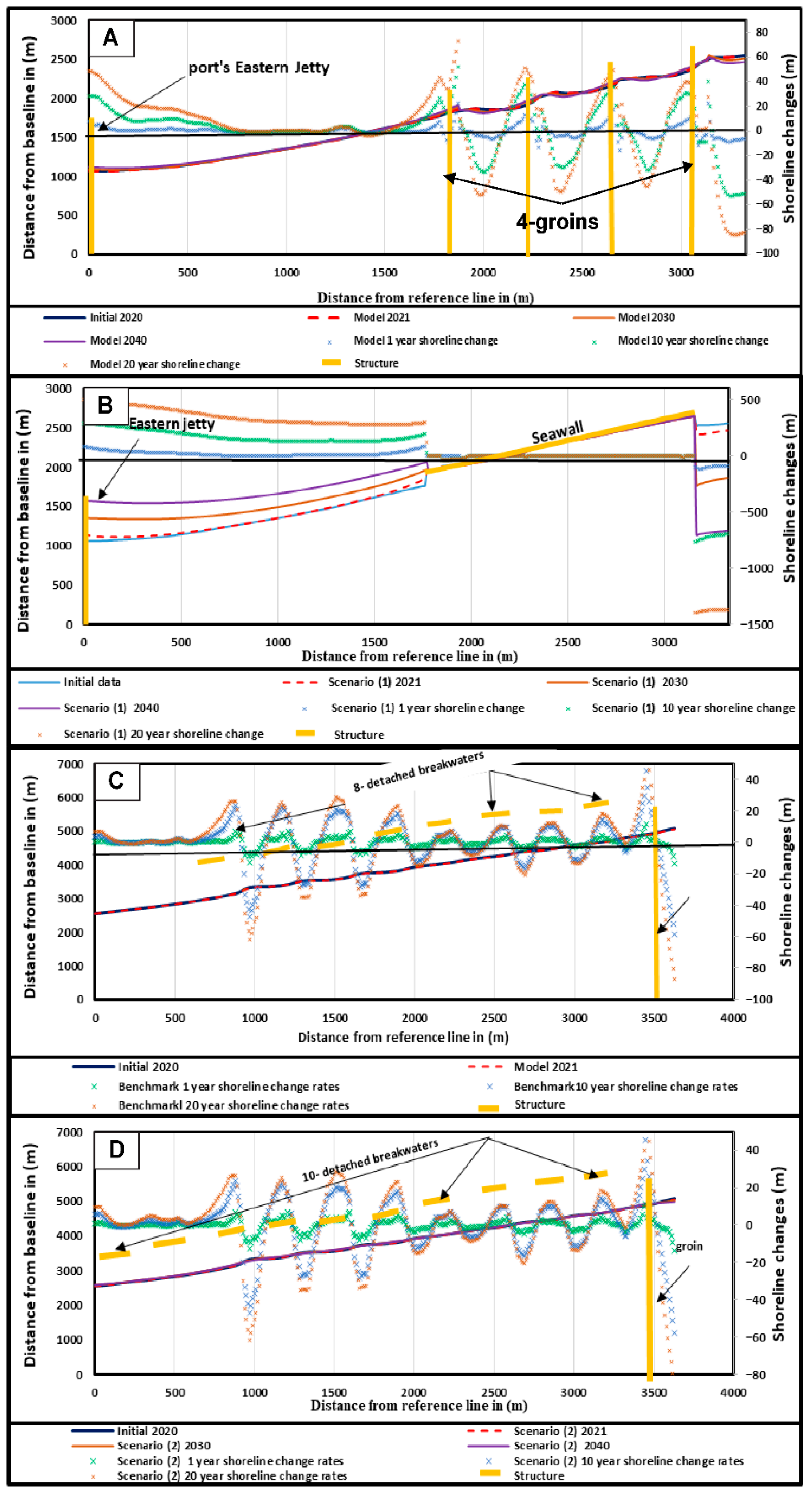

2.2. Litpack Model

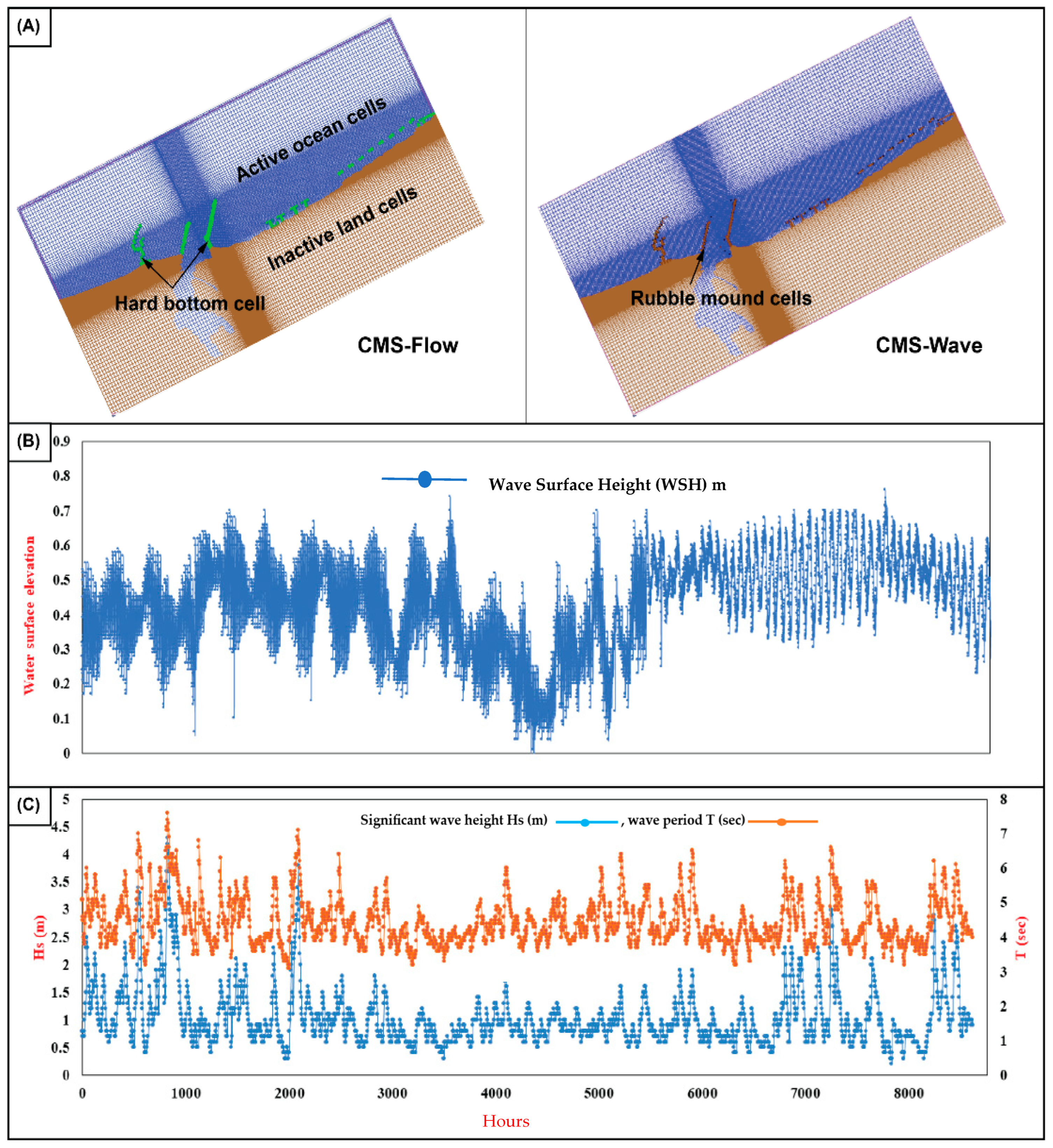

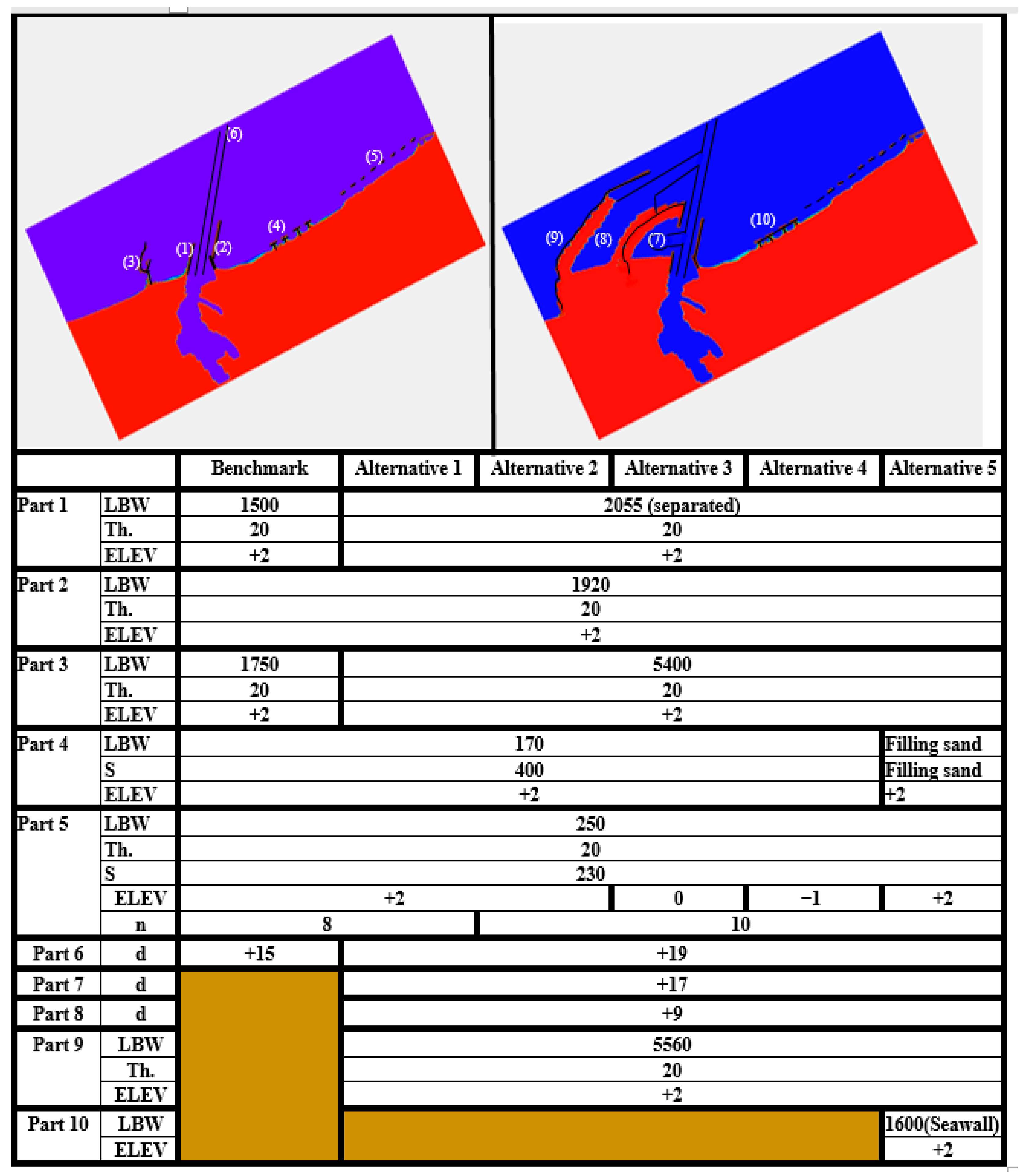

2.3. CMS Model

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Litpack

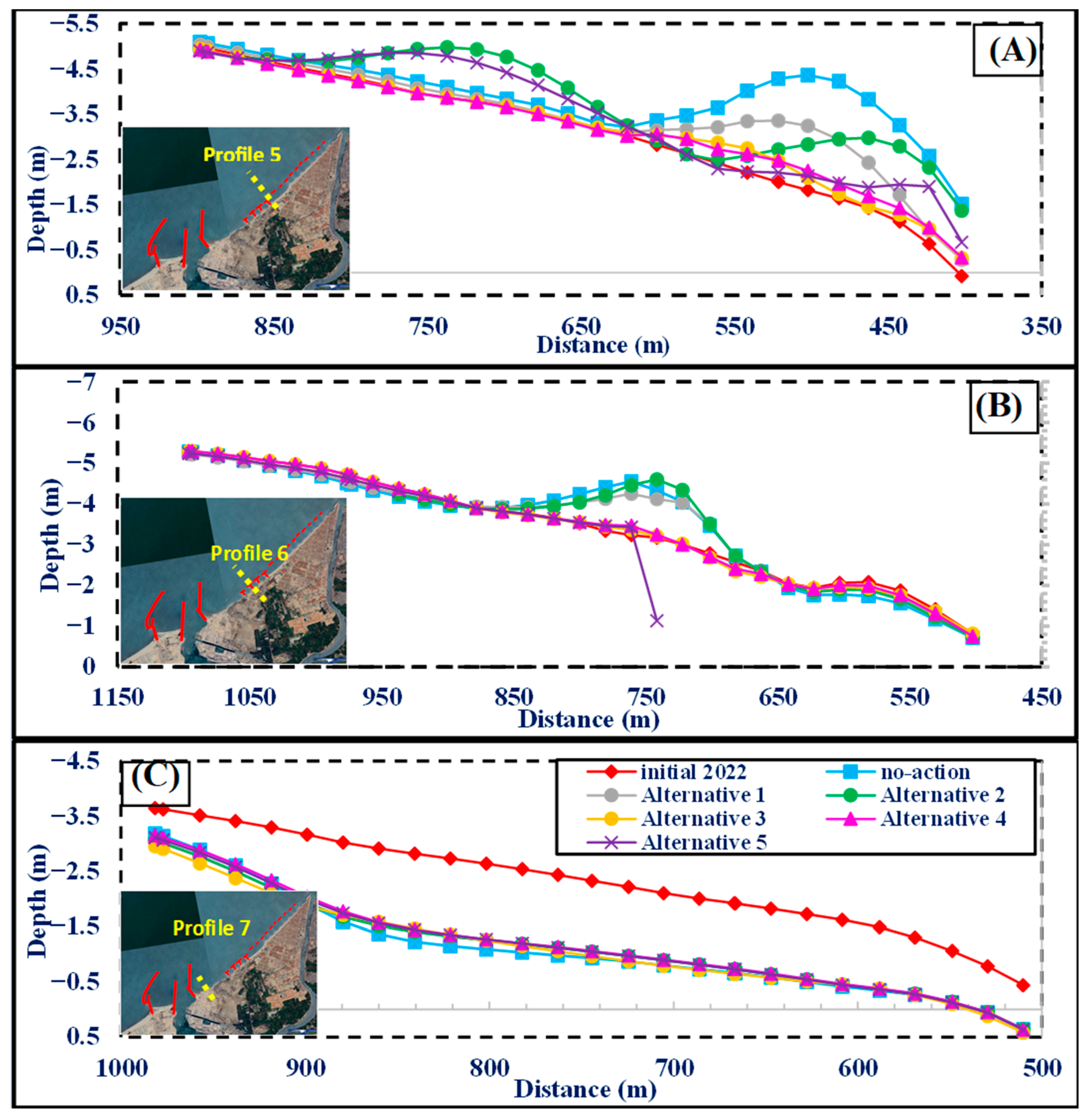

3.2. CMS Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- ElKotby, M.R.; Sarhan, T.A.; El-Gamal, M. Assessment of human interventions presence and their impact on shoreline changes along Nile delta, Egypt. Oceanologia 2023, 65, 595–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Asmar, H.M.; Taha, M.M.N. Monitoring Coastal Changes and Assessing Protection Structures at the Damietta Promontory, Nile Delta, Egypt, to Secure Sustainability in the Context of Climate Changes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Asmar, H.M.; Felfla, M.S.; ElKotby, M.R.; El-Kafrawy, S.B.; Naguib, D.M. Multi-Decadal shoreline dynamics of Ras El-Bar, Nile Delta: Unraveling human interventions and coastal resilience. Sci. Afr. 2025, 30, e02937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martín, R.; Valdemoro, H.; Jiménez, J.A. Unveiling coastal adaptation demands: Exploring erosion-induced spatial imperatives on the Catalan Coast (NW Mediterranean). Landsc. Urban Plan. 2025, 263, 105450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, S.H.; Suh, K.D. Effect of sea level rise on nearshore significant waves and coastal structures. Ocean Eng. 2016, 114, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Asmar, H.M. Short term coastal changes along Damietta-port Said coast northeast of the Nile Delta, Egypt. J. Coast. Res. 2002, 18, 433–441. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, B.; Wu, H.; Yang, S.; Zhang, J. Longshore suspended sediment transport and its implications for submarine erosion off the Yangtze River Estuary. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2017, 190, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacino, G.L.; Dragani, W.C.; Codignotto, J.O. Changes in wave climate and its impact on the coastal erosion in Samborombón Bay, Río de la Plata estuary, Argentina. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2019, 219, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Cai, Y.; Xie, M.; Qi, H.; Wang, Y. Wave dissipation and sediment transport patterns during shoreface nourishment towards equilibrium. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frihy, O.E.; Stanley, J.D. The modern Nile delta continental shelf, with an evolving record of relict deposits displaced and altered by sediment dynamics. Geographies 2023, 3, 416–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, K.S. Monitoring Coastline Dynamics Using Satellite Remote Sensing and Geographic Information Systems: A Review of Global Trends. Catrina Int. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 31, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eelsalu, M.; Montoya, R.D.; Aramburo, D.; Osorio, A.F.; Soomere, T. Spatial and temporal variability of wave energy resource in the eastern Pacific from Panama to the Drake passage. Renew. Energy 2024, 224, 120180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Asmar, H.M.; Felfla, M.S.; El-Kafrawy, S.B.; Gaber, A.; Naguib, D.M.; Bahgat, M.; El Safty, H.M.; Taha, M.M. A little tsunami at Ras El-Bar, Nile Delta, Egypt; consequent to the 2023 Kahramanmaraş Turkey earthquakes. Egypt J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2024, 27, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Asmar, H.M.; Felfla, M.S.; Ragab, M.T.; Naguib, D.M.; El-Kafrawy, S.B. New beach geomorphic features associated with a temporal climate storm event, coinciding with the February 6, 2023, little tsunami, Ras El-Bar, Nile Delta coast, Egypt. Geosci. Lett. 2025, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Heidarzadeh, M.; Satake, K.; Mulia, I.E.; Yamada, M. A tsunami warning system based on offshore bottom pressure gauges and data assimilation for Crete Island in the Eastern Mediterranean Basin. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2020, 125, e2020JB020293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Hamid, H.T. Geospatial analyses for assessing the driving forces of land use/land cover dynamics around the Nile Delta Branches, Egypt. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2020, 48, 1661–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElKotby, M.R.; Sarhan, T.A.; El-Gamal, M.; Masria, A. Evaluation of coastal risks to Sea level rise: Case study of Nile Delta Coast. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2024, 78, 103791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzichetto, M.; Sperandii, M.G.; Malavasi, M.; Carranza, M.L.; Acosta, A.T.R. Disentangling the effect of coastal erosion and accretion on plant communities of Mediterranean dune ecosystems. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2020, 241, 106758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, D.; Middleton, C.; Pratomlek, O. Precarity between a megacity and coastal erosion: A political economy of (un)managed retreat pathways in Thailand’s peri-urban Khun Samut Chin. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2025, 270, 107919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Nederhoff, K.; Gallien, T.W. Quantifying compound coastal flooding effects in urban regions using a tightly coupled 1D–2D model explicitly resolving flood defense infrastructure. Coast. Eng. 2025, 199, 104728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragab, M.T.M. The Use of Remote Sensing Techniques in the Observation and Evaluation of Sediments Movement in the Marine Belt Environment of Damietta Harbor. Master’s Thesis, Damietta University, Damietta, Egypt, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Damietta Port Authority. Annual Operational and Financial Report; Damietta Port Authority: Damietta, Egypt, 2023. Available online: https://www.dpa.gov.eg/?stats=yearly-statistical-report-for-2023 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- El-Asmar, H.M.; White, K. Changes in coastal sediment transport processes due to construction of New Damietta Harbour, Nile Delta, Egypt. Coast. Eng. 2002, 46, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerin Joe, R.J.; Pitchaimani, V.S.; Mirra, T.N.S.; Karuppannan, S. Shoreline dynamics and anthropogenic influences on coastal erosion: A multi-temporal analysis for sustainable shoreline management along a southwest coastal district of India. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 27, 100744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elhamid, H.F.; Zeleňáková, M.; Barańczuk, J.; Gergelova, M.B.; Mahdy, M. Historical trend analysis and forecasting of shoreline change at the Nile Delta using RS data and GIS with the DSAS tool. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Samra, R.M.; El-Gammal, M.; Al-Mutairi, N.; Alsahli, M.M.; Ibrahim, M.S. GIS-based approach to estimate sea level rise impacts on Damietta coast, Egypt. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewidar, K.; Bayoumi, S. Forecasting shoreline changes along the Egyptian Nile Delta coast using Landsat image series and Geographic Information System. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmail, M.; Mahmod, W.; Fath, H. Influence of Coastal Measures on Shoreline Kinematics Along Damietta coast Using Geospatial Tools. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 151, 012027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhan, T.; Mansour, N.A.; El-Gamal, M. Prediction of Shoreline Deformation Around Multiple Hard Coastal Protection Systems. Mansoura Eng. J. 2020, 45, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, A.M.; Soliman, M.R.; Yassin, A.A. Assessment of a combination between hard structures and sand nourishment eastern of Damietta harbor using numerical modeling. Alex. Eng. J. 2017, 56, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, Y.M.; Gemail, K.S.; Atia, H.M.; Mahdy, M. Insight into land cover dynamics and water challenges under anthropogenic and climatic changes in the eastern Nile Delta: Inference from remote sensing and GIS data. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 913, 169690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewidar, K.; Frihy, O.E. Automated techniques for quantification of beach change rates using Landsat series along the North-eastern Nile Delta, Egypt. J. Oceanogr. Mar. Sci. 2010, 1, 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- El-Zeiny, A.; Gad, A.-A.; El-Gammal, M.; Ibrahim, M. Space-borne technology for monitoring temporal changes along Damietta shoreline, Northern Egypt. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2016, 4, 459–468. [Google Scholar]

- Thieler, E.R.; Himmelstoss, E.A.; Zichichi, J.L.; Ergul, A. The Digital Shoreline Analysis System (DSAS) Version 4.0—An ArcGIS Extension for Calculating Shoreline Change; U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2008-1278; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Pareta, K. 1D-2D hydrodynamic and sediment transport modelling using MIKE models. Discov. Water 2024, 4, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriyono, W.; Wibowo, M.; Al Hakim, B.; Istiyanto, D.C. Modeling of Sediment Transport Affecting the Coastline Changes due to Infrastructures in Batang—Central Java. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 2015, 14, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, K.; Mahmod, W.E.; Masria, A.; Fath, H.; Nadaoka, K. Numerical simulation of shoreline responses in the vicinity of the western artificial inlet of the Bardawil Lagoon, Sinai Peninsula, Egypt. Appl. Ocean Res. 2018, 74, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athira, C.A.; Lekshmi Devi, C.A. Assessment of Longshore Sediment Transport Using LITPACK. Int. J. Adv. Trends Eng. Manag. 2023, 12, 1177–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Moghazy, N.H.; Soliman, A.; ELTahan, M. Effect of Human Interventions on Hydro-Dynamics of Sidi-Abdel Rahman Bay “North Western Coast of Egypt”. Int. Marit. Transp. Logist. 2024, 52, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolba, E. Impact of Coastal Erosion and Sedimentation Along the Northern Coast of Sinai Peninsula, Case Study: AL-ARISH Harbor Coast. Port-Said Eng. Res. J. 2012, 16, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, D.; Rahman, M.A. Simulation of longshore sediment transport and coastline changing along Kuakata Beach by mathematical modeling. IOSR J. Mech. Civ. Eng. 2022, 19, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanhory, A.; El-Tahan, M.; Moghazy, H.M.; Reda, W. Natural and manmade impact on Rosetta eastern shoreline using satellite Image processing technique. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 6247–6260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, T.; Yun, M.; Kim, I.; Do, K. alphaBeach: Self-attention-based spatiotemporal network for skillful prediction of shoreline changes multiple days ahead. Appl. Ocean Res. 2024, 153, 104292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, C.W.; Brown, M.E.; Sánchez, A.; Wu, W.; Buttolph, A.M. The Coastal Modeling System Flow Model (CMS-Flow): Past and Present. J. Coast. Res. 2011, 59, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masria, A.; Negm, A.M.; Iskander, M.M.; Saavedra, O.C. Hydrodynamic modeling of outlet stability case study Rosetta promontory in Nile delta. Water Sci. 2013, 27, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Rosati, J.D.; Brown, M.E.; Demirbilek, Z.; Li, H.; Reed, C.W.; Sanchez, A. Coastal Modeling System: Mathematical Formulations and Numerical Methods; Coastal and Hydraulics Laboratory: Vicksburg, MS, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nassar, K.; Masria, A.; Mahmod, W.E.; Negm, A.; Fath, H. Hydro-morphological modeling to characterize the adequacy of jetties and subsidiary alternatives in sedimentary stock rationalization within tidal inlets of marine lagoons. Appl. Ocean Res. 2019, 84, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.M.; Wang, P. Morphodynamics of barrier-inlet systems in the context of regional sediment management, with case studies from west-central Florida, USA. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 177, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masria, A.; El-Adawy, A.; Eltarabily, M.G. Simulating mitigation scenarios for natural and artificial inlets closure through validated morphodynamic models. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2021, 47, 101991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, N.; Sarhan, T.; Nassar, K.; El-Gamal, M. Examining hydro-morphological modulations in proximity to a drain’s estuarine outlet, case study: Kitchener Drain, Northern Coast of Egypt. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2024, 77, 103732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnabwy, M.T.; Elbeltagi, E.; El Banna, M.M.; Alshahri, A.H.; Hu, J.W.; Choi, B.G.; Kwon, Y.H.; Kaloop, M.R. Harbor Sedimentation Management Using Numerical Modeling and Exploratory Data Analysis. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2024, 2024, 1209460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnabwy, M.T.; Elbeltagi, E.; El Banna, M.M.; Elsheikh, M.Y.; Motawa, I.; Hu, J.W.; Kaloop, M.R. Conceptual prediction of harbor sedimentation quantities using AI approaches to support integrated coastal structures management. J. Ocean Eng. Sci. 2025, 10, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saengsupavanich, C.; Ariffin, E.H.; Yun, L.S.; Pereira, D.A. Environmental impact of submerged and emerged breakwaters. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, R.; Ohizumi, K.; Ishibashi, K.; Katayama, D.; Aoki, Y. Dynamics of beach scarp formation behind detached breakwaters. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2024, 298, 108651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulisz, W. Wave reflection and transmission at permeable breakwaters of arbitrary cross-section. Coast. Eng. 1985, 9, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.-M.; Van, D.D.; Duy, T.L.; Pham, N.T.; Dang, T.D.; Tanim, A.H.; Wright, D.; Thanh, P.N.; Anh, D.T. The influence of crest width and working states on wave transmission of Pile–Rock breakwaters in the coastal Mekong Delta. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rijn, L.C. Sediment transport, part II: Suspended load transport. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1984, 110, 1613–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rijn, L.C. Unified view of sediment transport by currents and waves. III: Graded beds. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2007, 133, 761–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Depth (m) | d50 | Roughness of Seabed | Fall Velocity (m/s) | Spreading Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +2: 0 | 0.812 | 0.012 | 0.085 | 0.901 |

| 0: −2 | 0.406 | 0.008 | 0.052 | 0.637 |

| −2: −4 | 0.134 | 0.004 | 0.013 | 0.366 |

| −4: −6 | 0.025 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.158 |

| −6: −8 | 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.0000423 | 0.084 |

| |||

| Accumulated sediment Volume of the active computed domain | Vin (m3) | Vout (m3) | Vnet (m3) |

| Benchmark | +8.83298 | −244,471 | −244,462 |

| Alternative 1 | +4.37523 | −245,318 | −245,314 |

| Alternative 2 | +1.18867 | −236,674 | −236,673 |

| Alternative 3 | +16.6677 | −243,654 | −243,637 |

| Alternative 4 | +1.16198 | −236,263 | −236,262 |

| Alternative 5 | +4.87119 | −235,797 | −235,792 |

| |||

| Accumulated sediment Volume of the active computed domain | Vin (m3) | Vout (m3) | Vnet (m3) |

| Benchmark | +18,247 | −165,427 | −147,180 |

| Alternative 1 | +16,306.6 | −83,798 | −67,491.4 |

| Alternative 2 | +67,428.1 | −66,823.7 | +604.457 |

| Alternative 3 | +37,572.5 | −29,605.4 | +7967.1 |

| Alternative 4 | +32,405.6 | −39,076.6 | −6670.95 |

| Alternative 5 | +66,417.8 | −64,935.7 | +1482.12 |

| |||

| Accumulated sediment Volume of the active computed domain | Vin (m3) | Vout (m3) | Vnet (m3) |

| Benchmark | +84,078.6 | −23,645.8 | +60,432.8 |

| Alternative 1 | +58,085.3 | −37,001.8 | +21,083.5 |

| Alternative 2 | +43,301.1 | −47,954.3 | −4653.18 |

| Alternative 3 | +51,847.9 | −66,818 | −14,970.1 |

| Alternative 4 | +55,184.1 | −65,554.5 | −10,370.3 |

| Alternative 5 | +42,007 | −48,424.7 | −6417.66 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

El-Asmar, H.M.; Elkotby, M.R.; Felfla, M.S.; Ragab, M.T. Integrated Predictive Modeling of Shoreline Dynamics and Sedimentation Mechanisms to Ensure Sustainability in Damietta Harbor, Egypt. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11174. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411174

El-Asmar HM, Elkotby MR, Felfla MS, Ragab MT. Integrated Predictive Modeling of Shoreline Dynamics and Sedimentation Mechanisms to Ensure Sustainability in Damietta Harbor, Egypt. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11174. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411174

Chicago/Turabian StyleEl-Asmar, Hesham M., May R. Elkotby, Mahmoud Sh. Felfla, and Mariam T. Ragab. 2025. "Integrated Predictive Modeling of Shoreline Dynamics and Sedimentation Mechanisms to Ensure Sustainability in Damietta Harbor, Egypt" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11174. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411174

APA StyleEl-Asmar, H. M., Elkotby, M. R., Felfla, M. S., & Ragab, M. T. (2025). Integrated Predictive Modeling of Shoreline Dynamics and Sedimentation Mechanisms to Ensure Sustainability in Damietta Harbor, Egypt. Sustainability, 17(24), 11174. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411174