Accessibility by Design: A Systematic Review of Inclusive E-Book Standards, Tools, and Practices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

Benefits of Assistive Technologies in Accessible E-Books

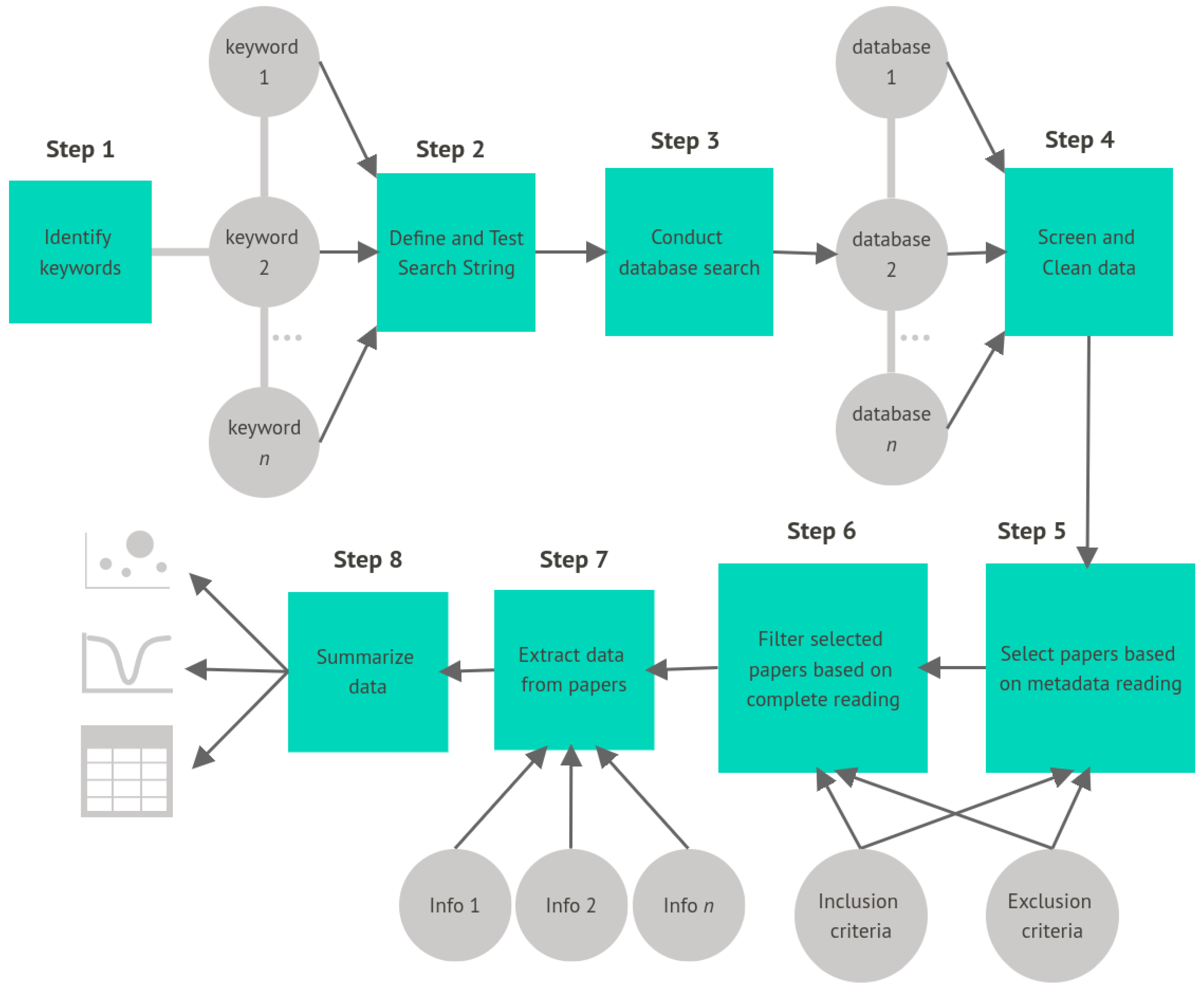

3. Systematic Literature Review Protocol

- define the research questions;

- define search strategies;

- a paper selection process; and

- extraction of relevant fields.

3.1. Challenges

- Underreporting of methods. Many papers omit which guidelines were applied, which features were implemented, or which checking tools were used, limiting reproducibility and synthesis [40].

3.2. Research Questions

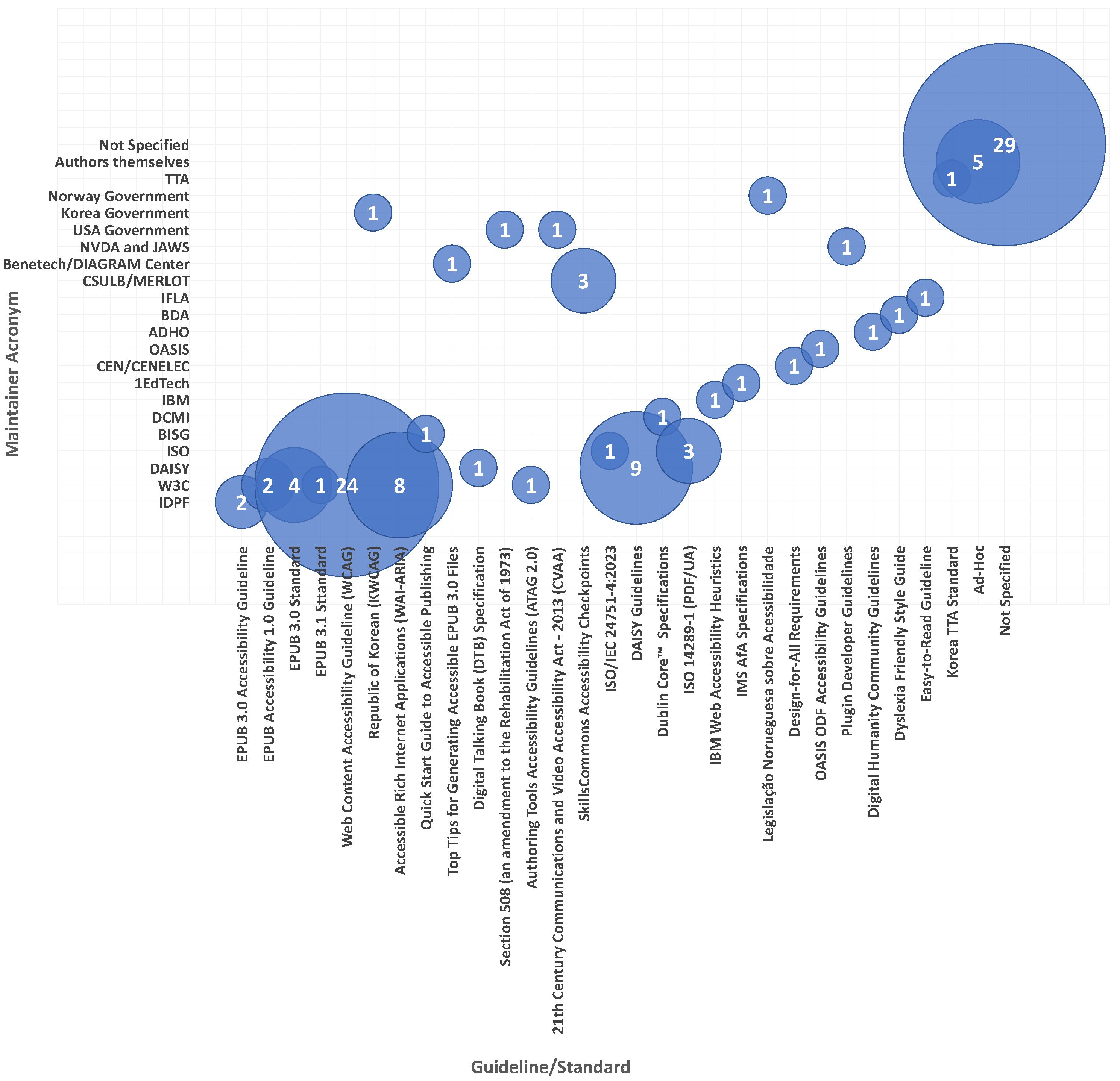

RQ1: What accessibility standards or guidelines are considered in e-books?

RQ2: What accessibility features are incorporated into e-books?

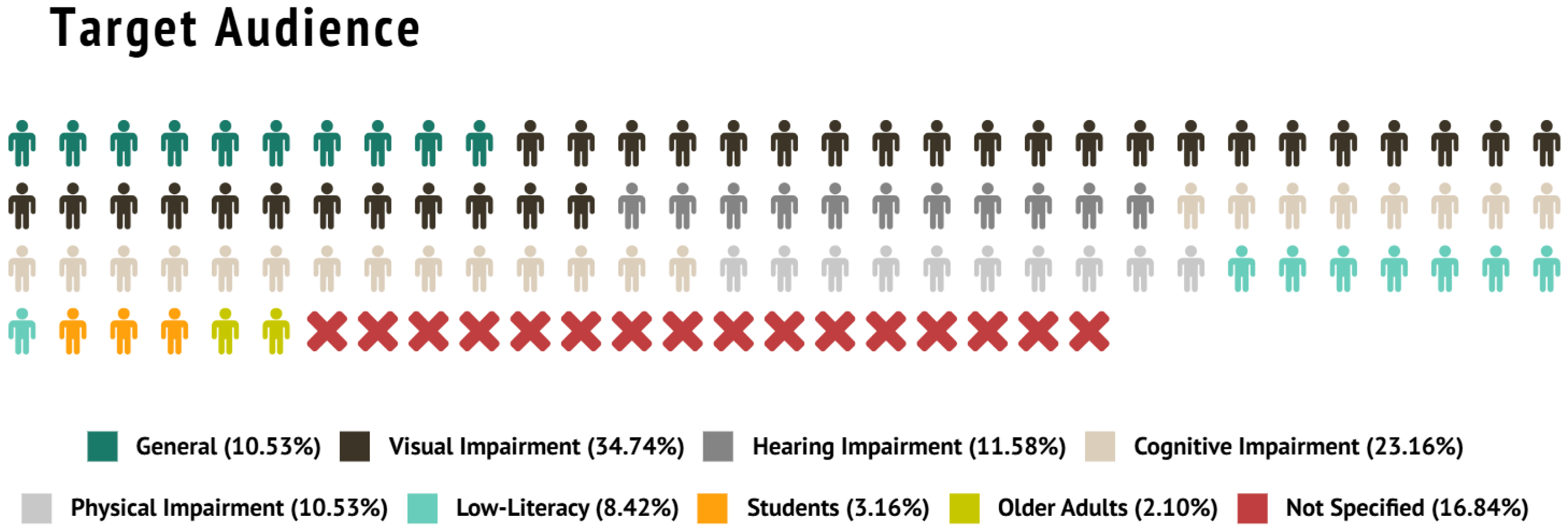

RQ3: Who is the target audience of the studies?

RQ4: What tools are being used to check the accessibility features of e-books?

3.3. Measurement Parameters and Operational Definitions

3.4. Search Strategies

3.4.1. Search Terms

3.4.2. Data Sources

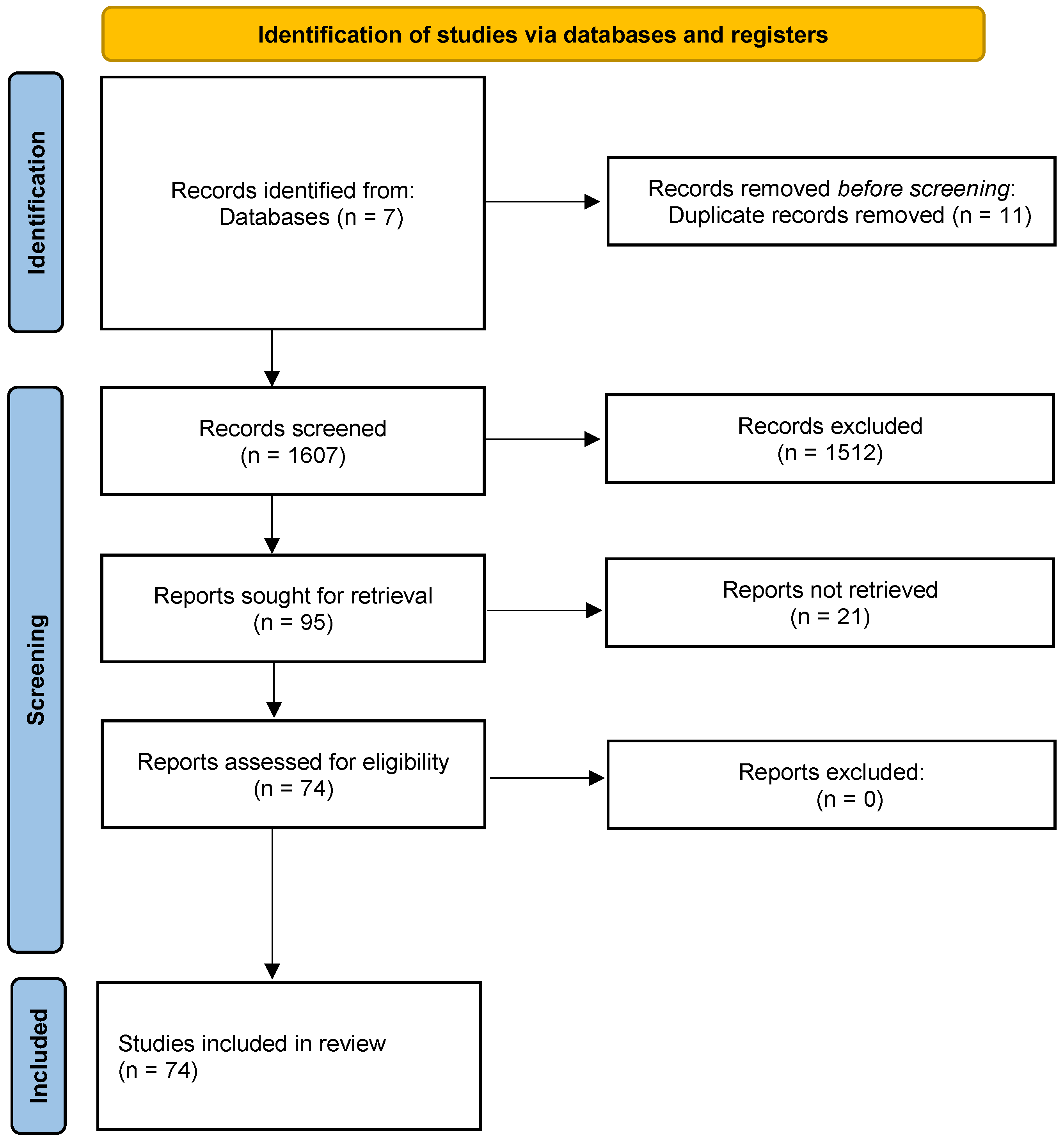

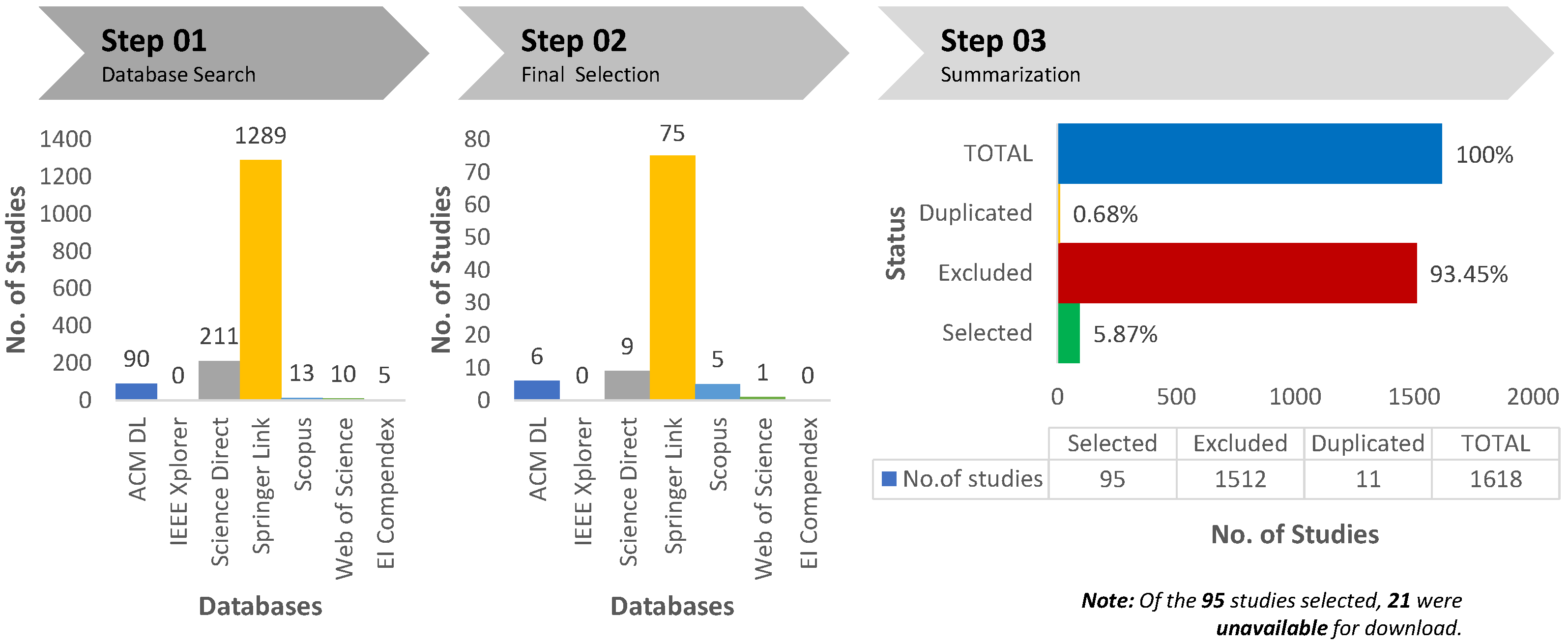

3.5. Selection Process

- a duplicate;

- does not focus on accessibility for e-books;

- not published as a conference paper or journal article (e.g., book, book chapter, magazine, and thesis); and

- not considered a complete study (less that five pages);

- unavailable for download.

3.6. Extraction of Relevant Fields

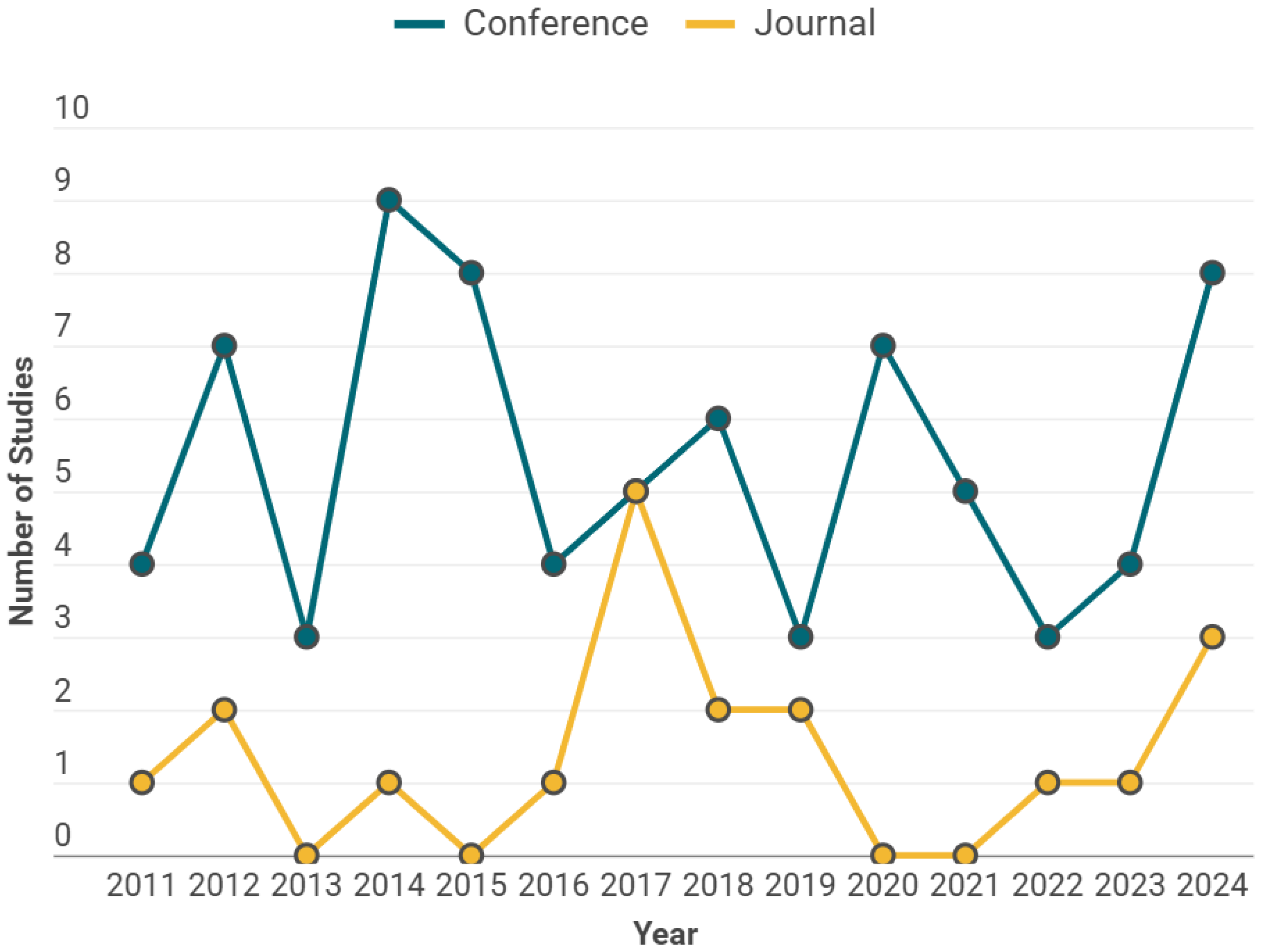

4. Findings

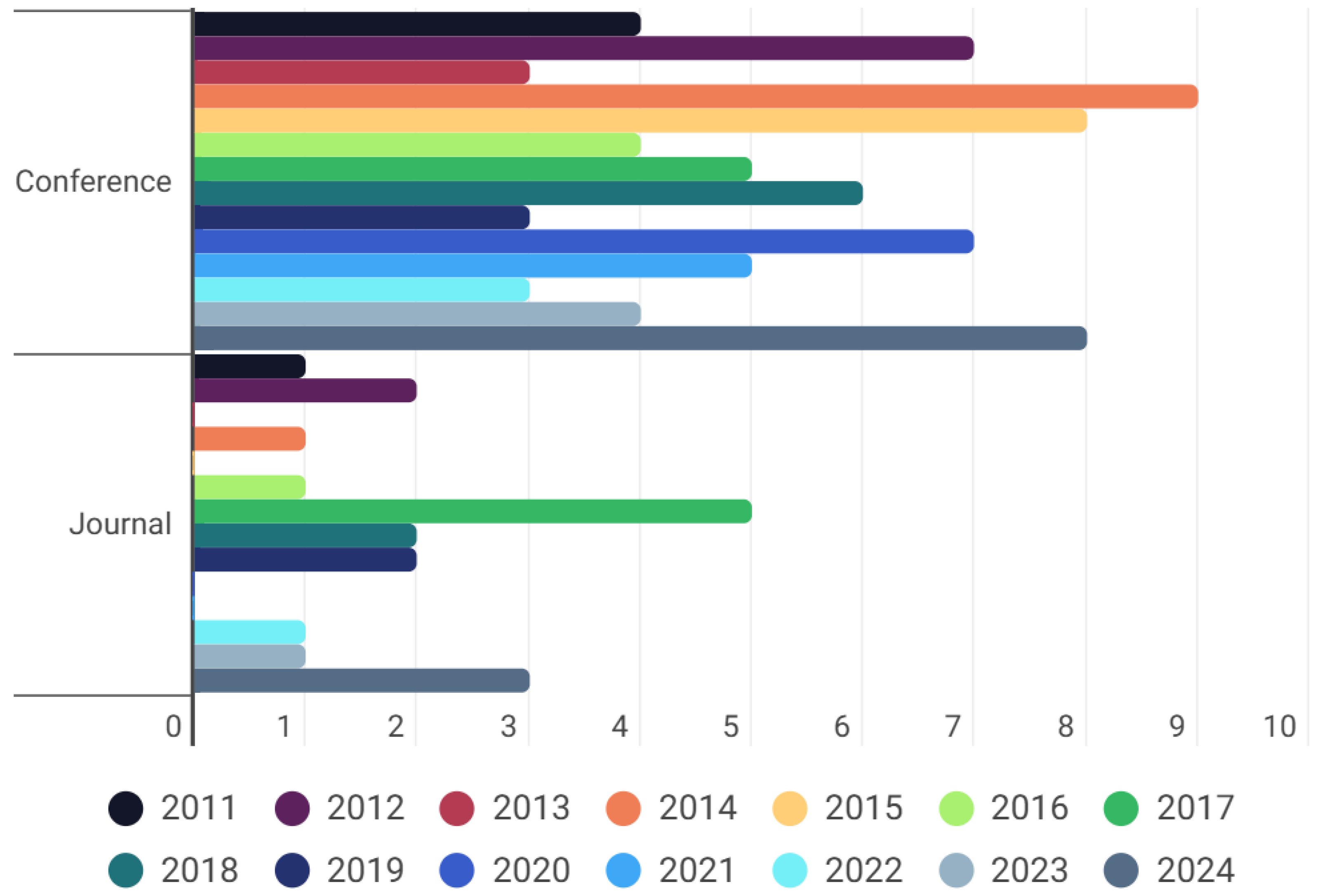

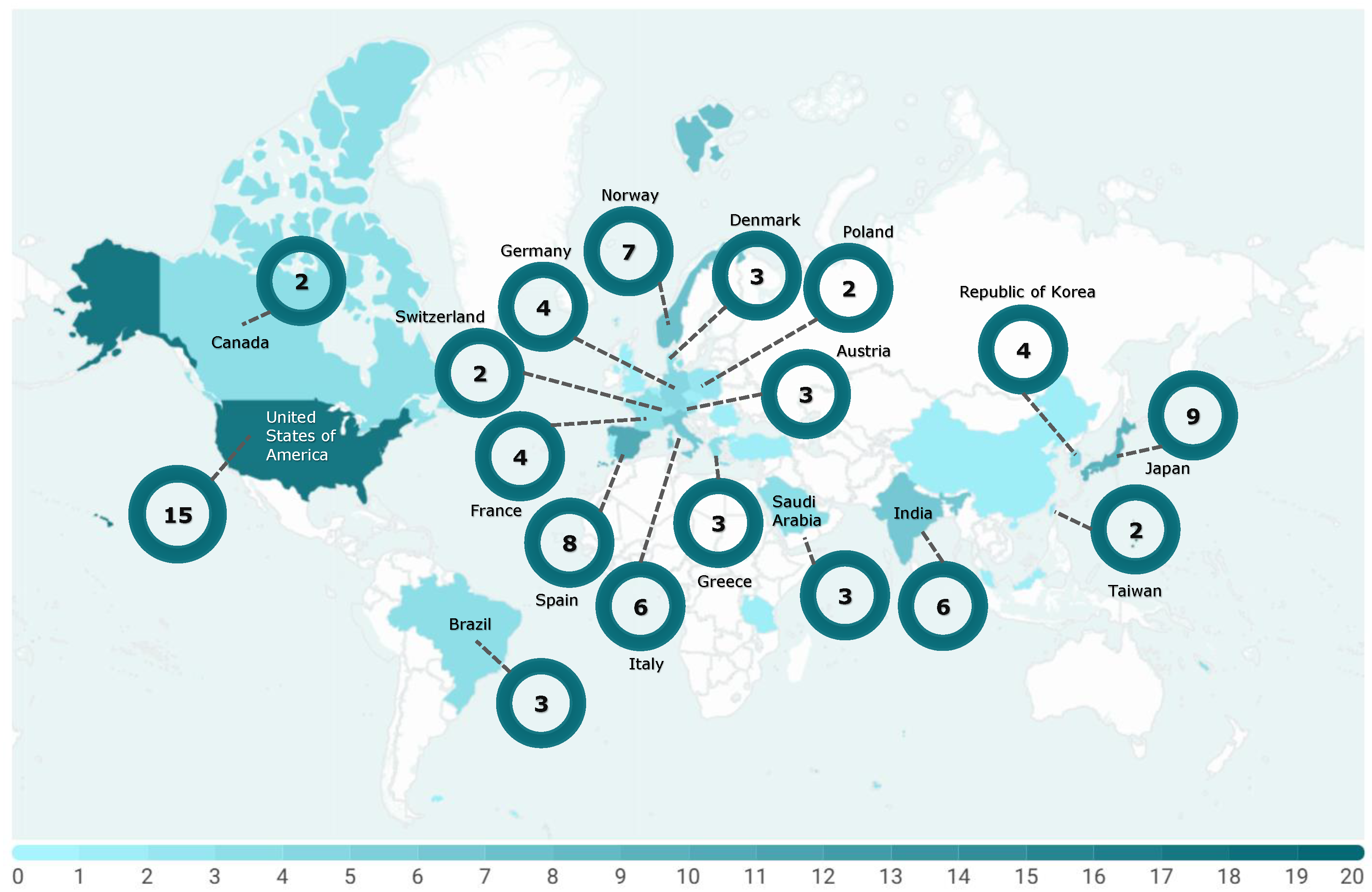

4.1. Summary of General Results

- International Conference on Computers Helping People with Special Needs;

- International Conference on Computers for Handicapped Persons;

- International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction;

- International Conference on Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction.

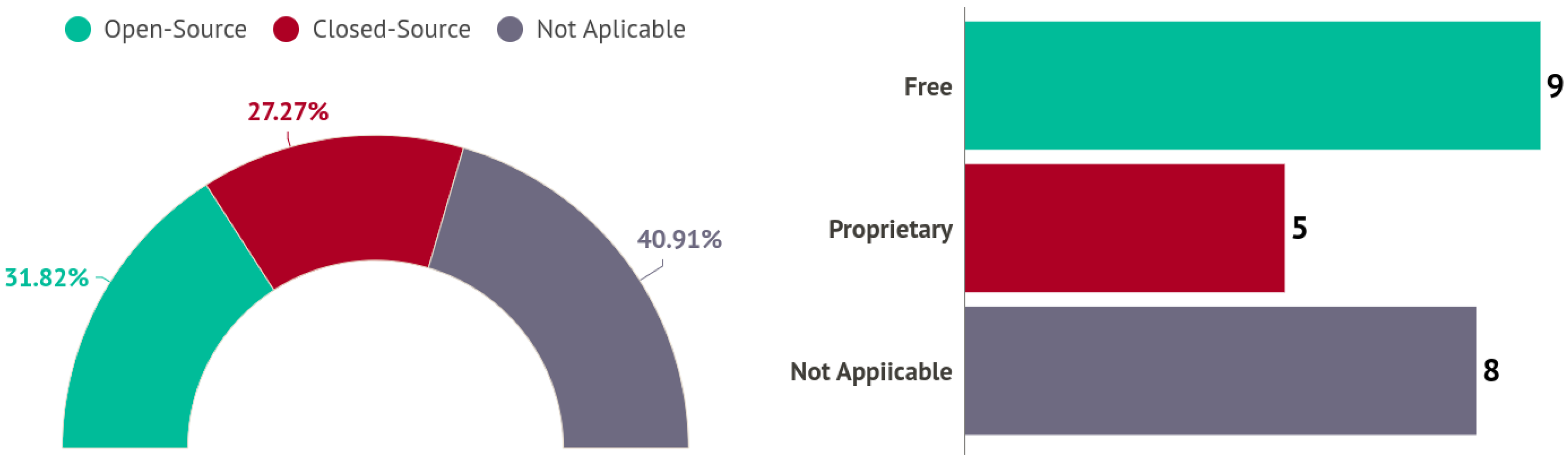

4.2. Summary of Specific Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of the Results

5.2. Design Innovations

5.3. Policy Recommendations

5.4. Practical Implications

- Integrate Features of Assistive Technologies (ATs): According to the World Health Organization (WHO), ATs “[…] is the application of organized knowledge and skills related to assistive products, including systems and services” [136]. Improving access to ATs can contribute to the achievement of the SDGs and ensuring that no one is left behind [137]. This ideology should be fully aligned with the e-book publishing market, as it serves as an essential tool for people of all ages and with all kinds of functional difficulties (e.g., cognition, communication, self-care, hearing, mobility, or vision) in all areas of life, including Education [136]. Examples of accessibility features that should be used in assistive products for Education include Alternative Text, Color Contrast, Text-to-Speech (TTS), and Metadata and Additional Information for Screen Readers.

- Content’s Structure and Navigation: The way the content of an e-book is structured and organized also needs to be inclusive, taking into account the characteristics of different reader groups [136]. Linked to this need, based on RSL, we highlight the usefulness of key marking elements to facilitate and make navigation more flexible to sections and content of particular interest to each reader at each moment of reading. To this end, the reading platforms need to provide resources that offer readers a rich learning experience through digital books. For example, multiple ways of navigating, focus order, and focus visible, page titled, heading and labels, link purpose, and the user’s location.

- Multimedia and Interactive Content: According to Costa et al. [1], the modernization of the digital publishing industry should focus on the creation, distribution, and accessibility of electronic books. The authors claim that the lack of interactivity, adaptivity, and immersive elements limits their ability to create engaging and personalized learning experiences, restricting students and educators from benefiting from cutting-edge educational tools. In this context, it is essential to establish a standardized yet flexible approach to developing interactive, immersive, and intelligent digital textbooks grounded in multimedia learning principles and universal design for learning.

- Allow Personalization and Customization: Each group of e-book users has its own interests and specific needs [136]. For example, these interests and needs may vary according to age, gender, area of residence, and the physical and mental condition of these users. Therefore, it is crucial to allow readers to personalize the presentation of a digital book’s content to fit their individual preferences. Additionally, they should be able to customize the features of the platform they use to access this content, such as e-readers.

- Testing and Validating using Accessibility Checkers Tools: Last but not least, it is mandatory that an accessible e-book be tested using official tools that verify compliance with key international guidelines (e.g., WCAG and EPUB Accessibility). Tools such as ACE by DAISY (https://daisy.org/activities/software/ace/, accessed on 10 February 2025) and EPUBCheck (https://www.w3.org/publishing/epubcheck/, accessed on 10 February 2025) verify and report on an e-book’s compliance with these guidelines, generating reports that can serve as checklists for publishers to identify gaps and inconsistencies for correction before publication. Other tools could be used in conjunction with the aforementioned checkers to make the validation of accessibility features in e-books more robust. A typical example of such a tool would be the NVDA screen reader (https://www.nvaccess.org/about-nvda/, accessed on 10 February 2025).

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Costa, B.; dos Santos, R.E.; Pimentel, B.; Cruz, N.; Fusco, J.; Silva, L.; Silva, R. PNLD Digital Textbook Reference Model: A Framework for Next-Generation Interactive and Intelligent Educational Resources. In Proceedings of the EDULEARN25 Proceedings, IATED, 17th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, Palma, Spain, 30 June–2 July 2025; pp. 5199–5208. [Google Scholar]

- da Costa, B.D.; dos Santos Escarpini, R.; Pimentel, B.A.; da Cruz, N.T.; Lobo, J.F.; Chaves, L.; de Amorim Silva, R. An evolutionary taxonomy for digital textbooks: Towards intelligent and immersive learning environments. In Proceedings of the EDULEARN25 Proceedings, IATED, 17th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, Palma, Spain, 30 June–2 July 2025; pp. 4117–4126. [Google Scholar]

- Fund, S. Sustainable Development Goals. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/inequality (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Literacy Definition. 2025. Available online: https://uis.unesco.org/en/glossary-term/literacy (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Leporini, B. An Accessible and Usable E-Book as an Educational Tool: How To Get It? In Proceedings of the CVHI, Granada, Spain, 28–31 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, H.; Gil, Y.H.; Yu, C.; Kim, H.K.; Lee, J.; Jee, H.K. Improved and accessible e-book reader application for visually impaired people. In Proceedings of the SIGGRAPH Asia 2017 Posters, Bangkok, Thailand, 27–30 November 2017; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrò, A.; Contini, E.; Leporini, B. Book4All: A tool to make an e-book more accessible to students with vision/visual-impairments. In Proceedings of the HCI and Usability for e-Inclusion: 5th Symposium of the Workgroup Human-Computer Interaction and Usability Engineering of the Austrian Computer Society, USAB 2009, Linz, Austria, 9–10 November 2009; Proceedings 5. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 236–248. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.R.; Naveed, M.A. Information accessibility for visually impaired students. Pak. J. Inf. Manag. Libr. 2021, 22, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, U.; Divya Venkatesh, J.; Muraleedharan, A.; Saluja, K.S.; JH, A.; Biswas, P. Accessibility analysis of educational websites using WCAG 2.0. Digit. Gov. Res. Pract. 2024, 5, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iniesto, F.; Rodrigo, C. The use of WCAG and automatic tools by computer science students: A case study evaluating MOOC accessibility. J. Univers. Comput. Sci. 2024, 30, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, D. The Marrakesh treaty to facilitate access to published works for persons who are blind, visually impaired or otherwise print disabled in the European Union: Reflecting on its implementation and gauging its impact from a disability perspective. IIC-Int. Rev. Intellect. Prop. Compet. Law 2024, 55, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntagwabira, V.; Ngabonziza, J.D.D.A.; Anguru, P.U. Factors Influencing Electronic Textbooks’ Reading Skills among Students in Secondary Schools of Muhanga District, Rwanda. Afr. J. Empir. Res. 2024, 5, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Masuudi, N.K.; Nawi, H.S.A.; Osman, S.; Al-Maqbali, H.A. Understanding the Barriers in Adopting the E-Textbooks Among Public School Students in Oman. TEM J. 2024, 13, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, D.C.; Taboubi, S.; Zaccour, G. Which business model for e-book pricing? Econ. Lett. 2014, 125, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkonen, P. Analyzing e-book pricing options and models based on FinELib e-book strategy. In Proceedings of the Presentation, World Library and Information Congress: 72nd IFLA General Conference and Council, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 20–24 August 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering; Technical Report; Schoolf of Computer Science and Mathematics, Keele University: Newcastle, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rello, L.; Kanvinde, G.; Baeza-Yates, R. A Mobile Application for Displaying More Accessible eBooks for People with Dyslexia. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2012, 14, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichten, C.S.; Asuncion, J.; Scapin, R. Digital Technology, Learning, and Postsecondary Students with Disabilities: Where We’ve Been and Where We’re Going. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 2014, 27, 369–379. [Google Scholar]

- Zdravkova, K. The potential of artificial intelligence for assistive technology in education. In Handbook on Intelligent Techniques in the Educational Process: Vol 1 Recent Advances and Case Studies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 61–85. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus-Quinn, A.; Fotiadis, T.; Yeratziotis, A.; Papadopoulos, G.A. Accessibility of e-books for Secondary School Students in Ireland and Cyprus. In Transforming Media Accessibility in Europe: Digital Media, Education and City Space Accessibility Contexts; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 229–245. [Google Scholar]

- Tlili, A.; Zhao, J.; Yang, K.; Wang, Y.; Bozkurt, A.; Huang, R.; Bonk, C.J.; Ashraf, M.A. Going beyond books to using e-books in education: A systematic literature review of empirical studies. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2024, 32, 2207–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, S.M. The E-books and Students’ Mathematics Performance: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Páginas Educación 2024, 17, e3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Op ‘t Eynde, E.; Depaepe, F.; Verschaffel, L.; Torbeyns, J. Shared Picture Book Reading in Early Mathematics: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Math. Didakt. 2023, 44, 505–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Sulaiman, W.; Mustafa, S. Usability Elements in Digital Textbook Development: A Systematic Review. Publ. Res. Q. 2020, 36, 74–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba Matraf, M.S.; Hashim, N.L.; Hussain, A. Visually Impaired Usability Requirements for Accessible Mobile Applications: A Checklist for Mobile E-book Applications. J. Inf. Commun. Technol. 2023, 22, 421–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Wide Web Consortium. Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1. W3C Recommendation (June 2018). 2018. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG21/ (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- DAISY Consortium. Accessible Publishing Knowledge Base. 2020. Available online: https://kb.daisy.org/ (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- UNESCO. Global Education Monitoring Report 2020: Inclusion and Education—All Means All; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Report on Assistive Technology; Technical Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDPF. EPUB Publications 3.0; International Digital Publishing Forum: Seattle, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vassiliou, M.; Rowley, J. Progressing the definition of “e-book”. Libr. Tech 2008, 26, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Messom, C.; Yau, K. e-Textbooks: Types, characteristics and open issues. J. Comput. 2012, 4, 2151–9617. [Google Scholar]

- Iwarsson, S.; Ståhl, A. Accessibility, usability and universal design—positioning and definition of concepts describing person-environment relationships. Disabil. Rehabil. 2003, 25, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, S.; Benedyk, R. Accessibility vs. Usability–Where is the Dividing Line? In Contemporary Ergonomics 2006; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 231–235. [Google Scholar]

- Yesilada, Y.; Brajnik, G.; Vigo, M.; Harper, S. Understanding web accessibility and its drivers. In Proceedings of the International Cross-Disciplinary Conference on Web Accessibility, Lyon, France, 16–17 April 2012; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Aizpurua, A.; Harper, S.; Vigo, M. Exploring the relationship between web accessibility and user experience. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2016, 91, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, B.; Cooper, M.; Reid, L.G.; Vanderheiden, G.; Chisholm, W.; Slatin, J.; White, J. Web content accessibility guidelines (WCAG) 2.0. WWW Consort. (W3C) 2008, 290, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Thirasi, W.; Illangasinghe, I.; Dickwella, U.; Jayakody, A.; Peiris, G.; Lokuliyana, S. Digital talking book. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2015, 121, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B. Procedures for performing systematic reviews. Keele Univ. 2004, 33, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lempola, A.; Poranen, T.; Zhang, Z. Comparing automatic accessibility testing tools. In Proceedings of the Annual Doctoral Symposium of Computer Science, CEUR-WS, Vaasa, Finland, 10–11 June 2024; pp. 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, C.A.; de Oliveira, A.F.; Mateus, D.A.; Costa, H.A.X.; Freire, A.P. Types of problems encountered by automated tool accessibility assessments, expert inspections and user testing: A systematic literature mapping. In Proceedings of the 18th Brazilian Symposium on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Vitoria, ES, Brazil, 22–25 October 2019; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, S.B. Publicly Funded Research Behind Private Paywalls: The Open Access Movement; SAGE Business Cases Originals; SAGE Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Collins, A.M.; Coughlin, D.; Kirk, S. The role of Google Scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichiliani, T.C.P.B.; Pizzolato, E.B. Cognitive disabilities and web accessibility: A survey into the Brazilian web development community. J. Interact. Syst. 2021, 12, 308–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.; de Souza Filho, J.C.; Bezerra, C.; Alves, V.A.; Lima, L.; Marques, A.B.; Teixeira Monteiro, I. Accessibility Evaluation of Web Systems for People with Visual Impairments: Findings from a Literature Survey. In Proceedings of the XXIII Brazilian Symposium on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Brasília, DF, Brazil, 7–11 October 2024; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, R.W.; Saldanha, I.J. How should systematic reviewers handle conference abstracts? A view from the trenches. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Almanza, A.; Rubio-González, C. Fixing dependency errors for Python build reproducibility. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis, Virtual, 11–17 July 2021; pp. 439–451. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, R.D. Reproducible research in computational science. Science 2011, 334, 1226–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collberg, C.; Proebsting, T.A. Repeatability in computer systems research. Commun. ACM 2016, 59, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.C.; de Carvalho César Sobrinho, Á.A.; Cordeiro, T.D.; Melo, R.F.; Bittencourt, I.I.; Marques, L.B.; da Cunha Matos, D.D.M.; da Silva, A.P.; Isotani, S. Applications of convolutional neural networks in education: A systematic literature review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 231, 120621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.C.; Sobrinho, Á.; Cordeiro, T.; da Silva, A.P.; Dermeval, D.; Marques, L.B.; Bittencourt, I.I.; dos Santos Júnior, J.J.; Melo, R.F.; dos Santos Portela, C.; et al. Assessing students’ handwritten text productions: A two-decades literature review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 250, 123780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.B.; Petersen, K.; Wohlin, C. A systematic literature review on the industrial use of software process simulation. J. Syst. Softw. 2014, 97, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brereton, P.; Kitchenham, B.A.; Budgen, D.; Turner, M.; Khalil, M. Lessons from applying the systematic literature review process within the software engineering domain. J. Syst. Softw. 2007, 80, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staples, M.; Niazi, M. Experiences using systematic review guidelines. J. Syst. Softw. 2007, 80, 1425–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlin, C. Guidelines for Snowballing in Systematic Literature Studies and a Replication in Software Engineering. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, New York, NY, USA, 13–14 May 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H.; Kim, H.Y.; Lim, S.B. Development of an electronic book accessibility standard for physically challenged individuals and deduction of a production guideline. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2019, 64, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mune, C.; Agee, A. Are e-books for everyone? An evaluation of academic e-book platforms’ accessibility features. J. Electron. Resour. Librariansh. 2016, 28, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leporini, B.; Minardi, L.; Pellegrino, G. Using InDesign Tool to Develop an Accessible Interactive EPUB 3: A Case Study; SciTePress: Setúbal, Portugal, 2019; pp. 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.T.; Vu, K.P.L.; Strybel, T.Z. A validation test of an accessibility evaluation method. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 2018, 607, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leporini, B.; Meattini, C. Personalization in the Interactive EPUB 3 Reading Experience: Accessibility Issues for Screen Reader Users; Association for Computing Machinery, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasdorf, B. Why accessibility is hard and how to make it easier: Lessons from publishers. Learn. Publ. 2018, 31, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roig, J.; Ribera, M.; Alcaraz, R. Authoring tools are critical to the accessibility of the documents: Recommendations for word processors, including interaction design. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Software Development and Technologies for Enhancing Accessibility and Fighting Info-Exclusion, New York, NY, USA, 31 August–2 September 2022; pp. 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roig, J.; Ribera, M. Implementation of the OOXML standard since its approval until today. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Software Development and Technologies for Enhancing Accessibility and Fighting Info-Exclusion, New York, NY, USA, 2–4 December 2020; pp. 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, T.; Aflatoony, L.; Leonard, L. “A Helping Hand”: Design and Evaluation of a Reading Assistant Application for Children with Dyslexia. In Proceedings of the 33rd Australian Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, New York, NY, USA, 30 November–2 December 2021; pp. 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayar, F.; Oriola, B.; Jouffrais, C. ALCOVE: An accessible comic reader for people with low vision. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, New York, NY, USA, 17–20 March 2020; pp. 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axtell, B.; Munteanu, C.; Demmans Epp, C.; Aly, Y.; Rudzicz, F. Touch-Supported Voice Recording to Facilitate Forced Alignment of Text and Speech in an E-Reading Interface. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, New York, NY, USA, 7–11 March 2018; pp. 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epp, C.D.; Munteanu, C.; Axtell, B.; Ravinthiran, K.; Aly, Y.; Mansimov, E. Finger tracking: Facilitating non-commercial content production for mobile e-reading applications. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, New York, NY, USA, 4–7 September 2017; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øiestad, S.; Bugge, M.M. Digitisation of publishing: Exploration based on existing business models. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2014, 83, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, J.L.; Piguet, Y.; Dormido, S.; Berenguel, M.; Costa-Castelló, R. New Interactive Books for Control Education. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, T.; Shinohara, S.; Tamura, Y. Typical Functions of e-Textbook, Implementation, and Compatibility Verification with Use of ePub3 Materials. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2013, 22, 1344–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gorghiu, L.M.; Gorghiu, G.; Bîzoi, M.; Suduc, A.M. The electronic book—A modern instrument used in teachers’ training process. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2011, 3, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Figueiredo, M.; Bidarra, J. The Development of a Gamebook for Education. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 67, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roskos, K.; Brueck, J.; Lenhart, L. An analysis of e-book learning platforms: Affordances, architecture, functionality and analytics. Int. J. Child-Comput. Interact. 2017, 12, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouh, E.; Karavirta, V.; Breakiron, D.A.; Hamouda, S.; Hall, S.; Naps, T.L.; Shaffer, C.A. Design and architecture of an interactive eTextbook—The OpenDSA system. Sci. Comput. Program. 2014, 88, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F. The impact of the book publishing transmedia storytelling model on business performance: The moderating role of the innovation environment. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2024, 37, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Fritz, R.M.; Yorba, L.; Manabat, A.K.M.; Katz, N.A.; Vu, K.P.L. E-book Accessibility Evaluations. In Advances in Human Factors in Training, Education, and Learning Sciences; Andre, T., Ed.; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 596, pp. 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, T.; Rajgopal, S.; Stiefelhagen, R. Accessible EPUB: Making EPUB 3 Documents Universal Accessible. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Miesenberger, K., Kouroupetroglou, G., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 10896, pp. 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartalesi, V.; Leporini, B. An Enriched ePub eBook for Screen Reader Users. In Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Access to Today’s Technologies; Antona, M., Stephanidis, C., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 9175, pp. 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarretta, E.; Ingrosso, A.; Carriero, A. Guidelines for Designing Accessible Digital (Text) Books: The Italian Case. In Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Access to Learning, Health and Well-Being; Antona, M., Stephanidis, C., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 9177, pp. 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartalesi Lenzi, V.; Leporini, B. Investigating an Accessible and Usable ePub Book via VoiceOver: A Case Study. In Human Factors in Computing and Informatics; Hutchison, D., Kanade, T., Kittler, J., Kleinberg, J.M., Mattern, F., Mitchell, J.C., Naor, M., Nierstrasz, O., Pandu Rangan, C., Steffen, B., et al., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 7946, pp. 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.T.; Manabat, A.K.M.; Chan, M.L.; Chong, I.; Vu, K.P.L. Accessibility Evaluation: Manual Development and Tool Selection for Evaluating Accessibility of E-Textbooks. In Advances in Neuroergonomics and Cognitive Engineering; Hale, K.S., Stanney, K.M., Eds.; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 488, pp. 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draffan, E.A.; McNaught, A.; James, A. eBooks, Accessibility and the Catalysts for Culture Change. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Miesenberger, K., Fels, D., Archambault, D., Peňáz, P., Zagler, W., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 8548, pp. 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobbe, C.; Frees, B.; Engelen, J. Accessibility Evaluation for Open Source Word Processors. In Information Quality in e-Health; Holzinger, A., Simonic, K.M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 7058, pp. 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.L.; Sun, Y.T.; Tesoro, A.M.; Vu, K.P.L. Development of a Scoring System for Evaluating the Accessibility of eTextbooks. In Advances in Neuroergonomics and Cognitive Engineering; Hale, K.S., Stanney, K.M., Eds.; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 488, pp. 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Yamaguchi, K. On Automatic Conversion from E-born PDF into Accessible EPUB3 and Audio-Embedded HTML5. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Miesenberger, K., Manduchi, R., Covarrubias Rodriguez, M., Peňáz, P., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12376, pp. 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, R.; Ito, K.; Yanagi, H.; Mima, Y. HapTalker: E-book User Interface for Blind People. In HCI International 2019—Posters; Stephanidis, C., Ed.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 1032, pp. 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B.W.; Moe, S. Accessibility in Multimodal Digital Learning Materials. In Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Universal Access to Information and Knowledge; Hutchison, D., Kanade, T., Kittler, J., Kleinberg, J.M., Kobsa, A., Mattern, F., Mitchell, J.C., Naor, M., Nierstrasz, O., Pandu Rangan, C., et al., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 8514, pp. 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbieh, D.; Punz, M.; Miesenberger, K.; Salinas-Lopez, V. Flex Picture eBook Builder—Simplifying the Creation of Accessible eBooks. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Miesenberger, K., Peňáz, P., Kobayashi, M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 14750, pp. 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierrès, O.; Schmitt-Koopmann, F.; Darvishy, A. PDF Accessibility in International Academic Publishers. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Miesenberger, K., Peňáz, P., Kobayashi, M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 14750, pp. 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballieu Christensen, L.; Chourasia, A. Document Transformation Infrastructure. In Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Universal Access to Information and Knowledge; Hutchison, D., Kanade, T., Kittler, J., Kleinberg, J.M., Kobsa, A., Mattern, F., Mitchell, J.C., Naor, M., Nierstrasz, O., Pandu Rangan, C., et al., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 8514, pp. 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.H.; Wang, C.M. Usability Analysis in Gesture Operation of Interactive E-Books on Mobile Devices. In Design, User Experience, and Usability. Theory, Methods, Tools and Practice; Marcus, A., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 6769, pp. 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berget, G.; Fagernes, S. Reading Experiences and Reading Efficiency Among Adults with Dyslexia: An Accessibility Study. In Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Access to Media, Learning and Assistive Environments; Antona, M., Stephanidis, C., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 12769, pp. 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourbetis, V.; Karipi, S.; Boukouras, K. Digital Accessibility in the Education of the Deaf in Greece. In Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Applications and Practice; Antona, M., Stephanidis, C., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12189, pp. 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyene, W.M. Realizing Inclusive Digital Library Environments: Opportunities and Challenges. In Research and Advanced Technology for Digital Libraries; Fuhr, N., Kovács, L., Risse, T., Nejdl, W., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 9819, pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, A.; Belani, M.; Bansal, A.; Jadhav, N.; Balakrishnan, M. Template Based Approach for Augmenting Image Descriptions. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Miesenberger, K., Kouroupetroglou, G., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 10896, pp. 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drümmer, O. Using Layout Applications for Creation of Accessible PDF: Technical and Mental Obstacles When Creating PDF/UA from Adobe Indesign CS 5.5. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Hutchison, D., Kanade, T., Kittler, J., Kleinberg, J.M., Mattern, F., Mitchell, J.C., Naor, M., Nierstrasz, O., Pandu Rangan, C., Steffen, B., et al., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 7382, pp. 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferati, M.; Beyene, W.M. Developing Heuristics for Evaluating the Accessibility of Digital Library Interfaces. In Universal Access in Human–Computer Interaction. Design and Development Approaches and Methods; Antona, M., Stephanidis, C., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 10277, pp. 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, M.; Lohmann, S.; Auer, S. Ontology-Based Representation of Learner Profiles for Accessible OpenCourseWare Systems. In Knowledge Engineering and Semantic Web; Różewski, P., Lange, C., Eds.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 786, pp. 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernier, A.; Burger, D. XML-Based Formats and Tools to Produce Braille Documents. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Hutchison, D., Kanade, T., Kittler, J., Kleinberg, J.M., Mattern, F., Mitchell, J.C., Naor, M., Nierstrasz, O., Pandu Rangan, C., Steffen, B., et al., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 7382, pp. 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, A.; Kouroupetroglou, G.; Riga, P. HERMOPHILOS: A Web-Based Information System for the Workflow Management and Delivery of Accessible eTextbooks. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Miesenberger, K., Bühler, C., Penaz, P., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 9758, pp. 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chourasia, A.; Tobias, J.; Githens, S.; Ding, Y.; Vanderheiden, G. ICT Access in Libraries for Elders. In Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population. Design for Aging; Zhou, J., Salvendy, G., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 9193, pp. 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansor, M.; Wan Adnan, W.A.; Abdullah, N. Slow Learner Children Profiling for Designing Personalized eBook. In Learning and Collaboration Technologies. Designing and Developing Novel Learning Experiences; Hutchison, D., Kanade, T., Kittler, J., Kleinberg, J.M., Kobsa, A., Mattern, F., Mitchell, J.C., Naor, M., Nierstrasz, O., Pandu Rangan, C., et al., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 8523, pp. 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchetti, R.; Erle, M.; Hofer, S. Mainstreaming the Creation of Accessible PDF Documents by a Rule-Based Transformation from Word to PDF. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Hutchison, D., Kanade, T., Kittler, J., Kleinberg, J.M., Mattern, F., Mitchell, J.C., Naor, M., Nierstrasz, O., Pandu Rangan, C., Steffen, B., et al., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 7382, pp. 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernier, A.; Burger, D. AcceSciTech: A Global Approach to Make Scientific and Technical Literature Accessible. In Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Applications and Services for Quality of Life; Hutchison, D., Kanade, T., Kittler, J., Kleinberg, J.M., Mattern, F., Mitchell, J.C., Naor, M., Nierstrasz, O., Pandu Rangan, C., Steffen, B., et al., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 8011, pp. 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.B.; Keegan, S.J.; Stevns, T. SCRIBE: A Model for Implementing Robobraille in a Higher Education Institution. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Hutchison, D., Kanade, T., Kittler, J., Kleinberg, J.M., Mattern, F., Mitchell, J.C., Naor, M., Nierstrasz, O., Pandu Rangan, C., Steffen, B., et al., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 7382, pp. 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, S.L. Developing Text Customisation Functionality Requirements of PDF Reader and Other User Agents. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Hutchison, D., Kanade, T., Kittler, J., Kleinberg, J.M., Mattern, F., Mitchell, J.C., Naor, M., Nierstrasz, O., Pandu Rangan, C., Steffen, B., et al., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 7382, pp. 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, J.; Chakraborty, D.; Chakraborty, B.; Basu, A. Effective Teaching Aids for People with Dyslexia. In Key Digital Trends Shaping the Future of Information and Management Science; Garg, L., Sisodia, D.S., Kesswani, N., Vella, J.G., Brigui, I., Misra, S., Singh, D., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 671, pp. 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.; Mueller, J. Blind and Deaf Consumer Preferences for Android and iOS Smartphones. In Inclusive Designing; Langdon, P.M., Lazar, J., Heylighen, A., Dong, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Megren, S.; Almutairi, A. Assessing the Effectiveness of an Augmented Reality Application for the Literacy Development of Arabic Children with Hearing Impairments. In Cross-Cultural Design. Applications in Cultural Heritage, Creativity and Social Development; Rau, P.L.P., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 10912, pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Lin, H.C.; Yueh, H.P. Explore Elder Users’ Reading Behaviors with Online Newspaper. In Cross-Cultural Design; Hutchison, D., Kanade, T., Kittler, J., Kleinberg, J.M., Kobsa, A., Mattern, F., Mitchell, J.C., Naor, M., Nierstrasz, O., Pandu Rangan, C., et al., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 8528, pp. 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidaroos, A.; Alkraiji, A. Evaluating the Usability of Library Websites Using an Heuristic Analysis Approach on Smart Mobile Phones: Preliminary Findings of a Study in Saudi Universities. In New Contributions in Information Systems and Technologies; Rocha, A., Correia, A.M., Costanzo, S., Reis, L.P., Eds.; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 353, pp. 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikułowski, D.; Brzostek-Pawłowska, J. Multi-sensual Augmented Reality in Interactive Accessible Math Tutoring System for Flipped Classroom. In Intelligent Tutoring Systems; Kumar, V., Troussas, C., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12149, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, T.; Jha, S.; Gupta, S.; Gote, A. Implementation of Braille Tab. In Innovations in Computer Science and Engineering; Saini, H.S., Sayal, R., Govardhan, A., Buyya, R., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2021; Volume 171, pp. 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.; Ordaz, M.G.; López, F.M. The Wisdom Innovation Model - Adjusting New Insights and Hosting New Perspectives to Human Augmented Reality. In ENTERprise Information Systems; Cruz-Cunha, M.M., Varajão, J., Powell, P., Martinho, R., Eds.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 219, pp. 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, A.; Al-Megren, S. Preliminary Investigations on Augmented Reality for the Literacy Development of Deaf Children. In Advances in Visual Informatics; Badioze Zaman, H., Robinson, P., Smeaton, A.F., Shih, T.K., Velastin, S., Terutoshi, T., Jaafar, A., Mohamad Ali, N., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 10645, pp. 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, L.K.; Azeta, A.; Misra, S.; Odun-Ayo, I.; Ajayi, P.T.; Azeta, V.; Agrawal, A. Enhancing the ow Adoption Rate of M-commerce in Nigeria Through Yorùbá Voice Technology. In Hybrid Intelligent Systems; Abraham, A., Hanne, T., Castillo, O., Gandhi, N., Nogueira Rios, T., Hong, T.P., Eds.; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1375, pp. 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Yamaguchi, K. Conversion of Multi-lingual STEM Documents in E-Born PDF into Various Accessible E-Formats. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Miesenberger, K., Kouroupetroglou, G., Mavrou, K., Manduchi, R., Covarrubias Rodriguez, M., Penáz, P., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 13341, pp. 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.; Luz, B.N.; Martins, V.F.; Dias, D.C.; De Paiva Guimarães, M. Teaching-Learning Environment Tool to Promote Individualized Student Assistance. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2015; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Misra, S., Gavrilova, M.L., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Torre, C., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 9155, pp. 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, K.; Suzuki, M. Accessible Authoring Tool for DAISY Ranging from Mathematics to Others. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Hutchison, D., Kanade, T., Kittler, J., Kleinberg, J.M., Mattern, F., Mitchell, J.C., Naor, M., Nierstrasz, O., Pandu Rangan, C., Steffen, B., et al., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 7382, pp. 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riga, P.; Kouroupetroglou, G.; Ioannidou, P.P. An Evaluation Methodology of Math-to-Speech in Non-English DAISY Digital Talking Books. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Miesenberger, K., Bühler, C., Penaz, P., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 9758, pp. 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyková, T.; Sporka, A.J.; Vystrčil, J.; Klíma, M.; Slavík, P. Pregnancy Test for the Vision-Impaired Users. In Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Applications and Services; Stephanidis, C., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 6768, pp. 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribera, M.; Pozzobon, R.; Sayago, S. Publishing accessible proceedings: The DSAI 2016 case study. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2020, 19, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.; Moon, G.; Kim, S.B.; Kim, J.; Kim, S. Improving webtoon accessibility for color vision deficiency in South Korea using deep learning. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2024, 24, 3049–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, E.; Valente, A. Interactivity and multimodality in language learning: The untapped potential of audiobooks. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2018, 17, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.J. Web accessibility of healthcare Web sites of Korean government and public agencies: A user test for persons with visual impairment. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2020, 19, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.Y.; Calabrèse, A.; Kornprobst, P. Towards accessible news reading design in virtual reality for low vision. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 27259–27278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslantas, T.K.; Gul, A. Digital literacy skills of university students with visual impairment: A mixed-methods analysis. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 5605–5625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zingoni, A.; Taborri, J.; Calabrò, G. A machine learning-based classification model to support university students with dyslexia with personalized tools and strategies. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penn State World Campus. Universal Design with Personas; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://sites.psu.edu/personas/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- CAST. Universal Design for Learning Guidelines (Version 3.0); Resource Website; CAST, Inc.: Woodcliff Lake, NJ, USA, 2024; Available online: https://udlguidelines.cast.org (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- ISO 14289-1; Document Management Applications—Electronic Document File Format Enhancement for Accessibility—Part 1: Use of ISO 32000-1 (PDF/UA-1). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Khanjani, A.; Sulaiman, R. The aspects of choosing open source versus closed source. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Symposium on Computers & Informatics, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 20–23 March 2011; pp. 646–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doblies, L.; Stolz, D.; Darvishy, A.; Hutter, H.P. PAVE: A Web Application to Identify and Correct Accessibility Problems in PDF Documents. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs. ICCHP 2014; Miesenberger, K., Fels, D., Archambault, D., Peňáz, P., Zagler, W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO and UNICEF. Global Report on Assistive Technology. Technical Report. World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/publications/i/item/9789240049451 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- WHO. Assistive Technology; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/assistive-technology (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Number | Field | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ID | Unique identifier for the study. |

| 2 | Title | Title of the study. |

| 3 | Authors | Authors of the study. |

| 4 | Year | Year of publication. |

| 5 | Country | Country of the first author of the study. |

| 6 | Type | Conference, journal, and workshop study. |

| 7 | Context | The research context of the study. |

| 8 | Goal | The goal of the study. |

| 9 | Solution | A brief description of the solution proposed in the study. |

| 10 | Accessibility Features | The accessibility features employed in the study. |

| 11 | Target Audience | For which users the solution was developed. |

| 12 | Guidelines | Which guidelines and/or standards were used in the study. |

| 13 | Accessibility Checkers Tools | Which tools for checking the accessibility of the e-books were used in the study. |

| 14 | Experiments | A brief experiment description carried out in the study. |

| 15 | Main results | Main results presented in the study. |

| 16 | Insights | Main insights discussed by the authors. |

| Publication Title | # Studies |

|---|---|

| Int. Conf. on Computers Helping People with Special Needs | 14 |

| Int. Conf. on Computers for Handicapped Persons | 10 |

| Int. Conf. on Human-Computer Interaction | 6 |

| Int. Conf. on Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction | 6 |

| World Conf. on Information Systems and Technologies | 3 |

| Int. Conf. on Software Development and Technologies for Enhancing Accessibility and Fighting Info-exclusion | 2 |

| Int. Conf. on Cross-Cultural Design | 2 |

| Iberoamerican Conf. on Applications and Usability of Interactive TV | 2 |

| Int. Conf. on Intelligent User Interfaces | 2 |

| Int. Conf. on Web Information Systems and Technologies | 1 |

| International Web for All Conference | 1 |

| Australian Conf. on Human-Computer Interaction | 1 |

| Int. Conf. on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services | 1 |

| International Federation of Automatic Control | 1 |

| Int. Conf. in Knowledge Based and Intelligent Information and Engineering Systems | 1 |

| Int. Conf. on Human Factors in Computing and Informatics | 1 |

| Int. Conf. on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics | 1 |

| Symposium of the Austrian HCI and Usability Engineering Group | 1 |

| Int. Conf. on Neuroergonomics and Cognitive Engineering | 1 |

| Int. Conf. of Design, User Experience, and Usability | 1 |

| Int. Conf. on Theory and Practice of Digital Libraries | 1 |

| Int. Conf. on Knowledge Engineering and the Semantic Web | 1 |

| Scandinavian Conf. on Information Systems | 1 |

| Int. Conf. on Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population | 1 |

| Int. Conf. on Technological Advancement in Embedded and Mobile Systems | 1 |

| Int. Conf. on Learning and Collaboration Technologies | 1 |

| Int. Conf. on Information Systems and Management Science | 1 |

| Cambridge Workshop on Universal Access and Assistive Technology | 1 |

| Int. Conf. on Intelligent Tutoring Systems | 1 |

| Int. Conf. on Innovations in Computer Science and Engineering | 1 |

| ENTERprise Information Systems | 1 |

| Int. Conf. on Advanced Computing Technology | 1 |

| International Visual Informatics Conference | 1 |

| Hybrid Intelligent Systems | 1 |

| World Conference on Information Systems for Business Management | 1 |

| Int. Conf. on Computational Science and Its Applications | 1 |

| Int. Conf. in Methodologies and intelligent Systems for Tech. Enhanced Learning | 1 |

| Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Applications and Services | 1 |

| Publication Title | # Studies |

|---|---|

| Universal Access in the Information Society | 4 |

| Procedia Computer Science | 2 |

| Computer Standards & Interfaces | 1 |

| Journal of Electronic Resources Librarianship | 1 |

| Learned Publishing | 1 |

| ACM Transactions on Accessible Computing | 1 |

| Technological Forecasting and Social Change | 1 |

| International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction | 1 |

| Science of Computer Programming | 1 |

| Journal of Organizational Change Management | 1 |

| Education, and Learning Sciences, Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing | 1 |

| Advances in Neuroergonomics and Cognitive Engineering | 1 |

| Multimedia Tools and Applications | 1 |

| Education and Information Technologies | 1 |

| Scientific Reports | 1 |

| ID | Title and Reference |

|---|---|

| 01 | Development of an electronic book accessibility standard for physically challenged individuals and deduction of a production guideline [58] |

| 02 | Are e-books for everyone? An evaluation of academic e-book platforms’ accessibility features [59] |

| 03 | Using InDesign tool to develop an accessible interactive EPUB 3: A case study [60] |

| 04 | A validation test of an accessibility evaluation method [61] |

| 05 | Personalization in the Interactive EPUB 3 Reading Experience: Accessibility Issues for Screen Reader Users [62] |

| 06 | Why accessibility is hard and how to make it easier: Lessons from publishers [63] |

| 07 | Authoring tools are critical to the accessibility of the documents: Recommendations for word processors, including interaction design [64] |

| 08 | Implementation of the OOXML standard since its approval until today [65] |

| 09 | “A Helping Hand”: Design and Evaluation of a Reading Assistant Application for Children with Dyslexia [66] |

| 10 | ALCOVE: an accessible comic reader for people with low vision [67] |

| 11 | Touch-Supported Voice Recording to Facilitate Forced Alignment of Text and Speech in an E-Reading Interface [68] |

| 12 | Finger tracking: facilitating non-commercial content production for mobile e-reading applications [69] |

| 13 | Digitisation of publishing: Exploration based on existing business models [70] |

| 14 | New Interactive Books for Control Education [71] |

| 15 | Typical Functions of e-Textbook, Implementation, and Compatibility Verification with Use of ePub3 Materials [72] |

| 16 | The electronic book—a modern instrument used in teachers’ training process [73] |

| 17 | The Development of a Gamebook for Education [74] |

| 18 | An analysis of e-book learning platforms: Affordances, architecture, functionality and analytics [75] |

| 19 | A Mobile Application for Displaying More Accessible eBooks for People with Dyslexia [17] |

| 20 | Design and architecture of an interactive eTextbook—The OpenDSA system [76] |

| 21 | The impact of the book publishing transmedia storytelling model on business performance: the moderating role of the innovation environment [77] |

| 22 | E-book Accessibility Evaluations [78] |

| 23 | Accessible EPUB: Making EPUB 3 Documents Universal Accessible [79] |

| 24 | An Enriched ePub eBook for Screen Reader Users [80] |

| 25 | Guidelines for Designing Accessible Digital (Text) Books: The Italian Case [81] |

| 26 | Investigating an Accessible and Usable ePub Book via VoiceOver: A Case Study [82] |

| 27 | Accessibility Evaluation: Manual Development and Tool Selection for Evaluating Accessibility of E-Textbooks [83] |

| 28 | eBooks, Accessibility and the Catalysts for Culture Change [84] |

| 29 | Accessibility Evaluation for Open Source Word Processors [85] |

| 30 | Development of a Scoring System for Evaluating the Accessibility of eTextbooks [86] |

| 31 | On Automatic Conversion from E-born PDF into Accessible EPUB3 and Audio-Embedded HTML5 [87] |

| 32 | HapTalker: E-book User Interface for Blind People [88] |

| 33 | Accessibility in Multimodal Digital Learning Materials [89] |

| 34 | Flex Picture eBook Builder - Simplifying the Creation of Accessible eBooks [90] |

| 35 | PDF Accessibility in International Academic Publishers [91] |

| 36 | Document Transformation Infrastructure [92] |

| 37 | Usability Analysis in Gesture Operation of Interactive E-Books on Mobile Devices [93] |

| 38 | Reading Experiences and Reading Efficiency Among Adults with Dyslexia: An Accessibility Study [94] |

| 39 | Digital Accessibility in the Education of the Deaf in Greece [95] |

| 40 | Realizing Inclusive Digital Library Environments: Opportunities and Challenges [96] |

| 41 | Template Based Approach for Augmenting Image Descriptions [97] |

| 42 | Using Layout Applications for Creation of Accessible PDF: Technical and Mental Obstacles When Creating PDF/UA from Adobe Indesign CS 5.5 [98] |

| 43 | Developing Heuristics for Evaluating the Accessibility of Digital Library Interfaces [99] |

| 44 | Ontology-Based Representation of Learner Profiles for Accessible OpenCourseWare Systems [100] |

| 45 | XML-Based Formats and Tools to Produce Braille Documents [101] |

| 46 | HERMOPHILOS: A Web-Based Information System for the Workflow Management and Delivery of Accessible eTextbooks [102] |

| 47 | ICT Access in Libraries for Elders [103] |

| 48 | Slow Learner Children Profiling for Designing Personalized eBook [104] |

| 49 | Mainstreaming the Creation of Accessible PDF Documents by a Rule-Based Transformation from Word to PDF [105] |

| 50 | AcceSciTech: A Global Approach to Make Scientific and Technical Literature Accessible [106] |

| 51 | SCRIBE: A Model for Implementing Robobraille in a Higher Education Institution [107] |

| 52 | Developing Text Customisation Functionality Requirements of PDF Reader and Other User Agents [108] |

| 53 | Effective Teaching Aids for People with Dyslexia [109] |

| 54 | Blind and Deaf Consumer Preferences for Android and iOS Smartphones [110] |

| 55 | Assessing the Effectiveness of an Augmented Reality Application for the Literacy Development of Arabic Children with Hearing Impairments [111] |

| 56 | Explore Elder Users’ Reading Behaviors with Online Newspaper [112] |

| 57 | Evaluating the Usability of Library Websites Using an Heuristic Analysis Approach on Smart Mobile Phones: Preliminary Findings of a Study in Saudi Universities [113] |

| 58 | Multi-sensual Augmented Reality in Interactive Accessible Math Tutoring System for Flipped Classroom [114] |

| 59 | Implementation of Braille Tab [115] |

| 60 | The Wisdom Innovation Model—Adjusting New Insights and Hosting New Perspectives to Human Augmented Reality [116] |

| 61 | Preliminary Investigations on Augmented Reality for the Literacy Development of Deaf Children [117] |

| 62 | Enhancing the ow Adoption Rate of M-commerce in Nigeria Through Yorùbá Voice Technology [118] |

| 63 | Conversion of Multi-lingual STEM Documents in E-Born PDF into Various Accessible E-Formats [119] |

| 64 | Teaching-Learning Environment Tool to Promote Individualized Student Assistance [120] |

| 65 | Accessible Authoring Tool for DAISY Ranging from Mathematics to Others [121] |

| 66 | An Evaluation Methodology of Math-to-Speech in Non-English DAISY Digital Talking Books [122] |

| 67 | Pregnancy Test for the Vision-Impaired Users [123] |

| 68 | Publishing accessible proceedings: the DSAI 2016 case study [124] |

| 69 | Improving webtoon accessibility for color vision deficiency in South Korea using deep learning [125] |

| 70 | Interactivity and multi-modality in language learning: the untapped potential of audiobooks [126] |

| 71 | Web accessibility of healthcare Web sites of Korean government and public agencies: a user test for persons with visual impairment [127] |

| 72 | Towards accessible news reading design in virtual reality for low vision [128] |

| 73 | Digital literacy skills of university students with visual impairment: A mixed-methods analysis [129] |

| 74 | A machine learning-based classification model to support university students with dyslexia with personalized tools and strategies [130] |

| Persona | Description | Difficulties | Needs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sean | A blind student who lost his sight in a car accident. | Lack of a clear heading structure, ambiguous link text, and assignments that require tools that rely on vision. | All course pages, external websites, and third-party tools are compatible with JAWS and keyboard commands. In addition, math content is provided in MathML. |

| Andy | A Human Resources professional, with experience working with individuals who are deaf and colorblind. | Videos that lack captions or transcripts, as well as visuals or text content where meaning is conveyed primarily through color. | Videos have captions, audio files have transcripts, and data representations in charts and graphs have good color contrast. |

| Linda | A vocational rehabilitation counselor with mobility impaired. | Content that cannot be accessed with a keyboard, and material readings are not provided in an accessible digital format. | Link text is meaningful and clearly identifies the destination and content type, as well as applications that allow speech-to-text input. |

| Phil | An older adult with low vision, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI). | Most readings are particularly PDFs that are low-quality scans and incompatible materials with magnifiers. | Content is provided as real text, online content can be magnified to 400% without distortion, and images have good resolution, high color contrast, and readable font. |

| Sarah | A student working part-time with depression and anxiety. | Text-heavy lesson pages with no headings to break up content, and highly structured sequential content. | Consistent navigation and pages have a clear heading structure. Additionally, videos are captioned and transcribed so that she can use transcripts for note taking. |

| Jenna | A student working part-time with ADHD (Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder). | Videos that are longer than five minutes, text displayed as an image without alternative text, and inconsistent navigation. | Hear the text read aloud, paragraphs of text are kept short and content is left aligned, as well as a logical heading structure and a clear outline where critical information is easy to find. |

| Micael | A student diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | Long readings that are just text, and a lack of support and a clear rubric for completing writing assignments. | Text is broken up visually with good images and icons, text font and color can be customized by the user, and consistent navigation and pattern. |

| Feature | # Studies |

|---|---|

| Assistive Technologies | 22 |

| Personalization/Customization | 17 |

| Alternative Text | 16 |

| Content’s Structure | 14 |

| Interactive Features | 15 |

| Navigation | 13 |

| Text-to-Speech (TTS)/Narration | 13 |

| Multimedia Content | 12 |

| Metadata and Additional Information | 12 |

| Color Contrast | 10 |

| Screen Reader | 10 |

| Semantic | 7 |

| Tagging | 6 |

| Exporting | 5 |

| Support Different Languages | 5 |

| Download | 4 |

| Support Braille | 4 |

| Multi-modal | 3 |

| Support MathML | 3 |

| OCR | 2 |

| Screen Magnifiers | 1 |

| Not Specified | 15 |

| Tool | # Studies | Enterprise | Distribution | License |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPUBCheck (https://www.w3.org/publishing/epubcheck/) | 3 | W3C (Cambridge, MA, USA) | Open-Source | Free |

| ACE (Accessibility Checker for EPUB: https://daisy.org/activities/software/ace/) | 2 | DAISY Consortium (Grave, The Netherlands) | Open-Source | Free |

| ODT Accessibility Checker (https://sourceforge.net/projects/accessodf/) | 1 | - | Open-Source | Free |

| PDF Accessibility Validation Engine (PAVE: https://pave-pdf.org/) | 1 | ZHAW—Accessibility Lab. (Winterthur, Switzerland) | Open-Source | Free |

| PDF Accessibility Checker (PAC: https://pac.pdf-accessibility.org/) | 2 | axes4 GmbH (Zurich, Switzerland) | Closed-Source | Free |

| MS Word wizard (https://www.microsoft.com/pt-br/microsoft-365/word) | 1 | Microsoft Corp. (Redmond, WA, USA) | Closed-Source | Proprietary |

| Adobe® Acrobat DC (https://get.adobe.com/br/reader/) | 1 | Adobe Inc. (San Jose, CA, USA) | Closed-Source | Proprietary |

| Non-AT Tools (non-assistive technology) | 1 | - | - | - |

| Color Contrast Analyzer (CCA: https://www.tpgi.com/color-contrast-checker/) | 1 | TPGi, LLC. (Clearwater, FL, USA) | Open-Source | Free |

| AT Tools (assistive technology) | 2 | - | - | - |

| JAWS (https://www.freedomscientific.com/products/software/jaws/) | 3 | Freedom Scientific, Inc. (Clearwater, FL, USA) | Closed-Source | Proprietary |

| Kurzweil 3000 (https://www.kurzweil3000.com/) | 1 | Kurzweil Education (Dallas, TX, USA) | Closed-Source | Proprietary |

| NVDA (https://www.nvaccess.org/) | 3 | NV Access (Brisbane, Australia) | Open-Source | Free |

| ZoomText (https://www.freedomscientific.com/products/software/zoomtext/) | 2 | Freedom Scientific, Inc. (Clearwater, FL, USA) | Closed-Source | Proprietary |

| Ad-hoc | 3 | - | - | - |

| Manual | 11 | - | - | - |

| Conversion Tools | 2 | - | - | - |

| Authoring Tools | 5 | - | - | - |

| Expressive Sign Language Test Application | 1 | - | - | - |

| WebRTC (JavaScript Library: https://webrtc.org/) | 1 | Apple (Cupertino, CA, USA), Google (Mountain View, CA, USA), Microsoft (Redmond, WA, USA), and Mozilla (San Francisco, CA, USA) | Open-Source | Free |

| Toptal Colorblind Web Page Filter (https://www.toptal.com/designers/colorfilter) | 1 | Toptal, LLC. (Wilmington, DC, USA) | - | Free |

| Not Specified | 43 | - | - | - |

| Tool | Content Type | Mode | Focus | Compliance | Reports | Languages | Correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPUB Check | EPUB | CLI/ Java Lib | EPUB structure validation | EPUB 3.3 | Simple, CLI | Multiple | Manual |

| Ace by DAISY | EPUB | CLI, JS node, Web API, GUI | EPUB accessibility | EPUB accessibility | Detailed HTML | English, others | Manual |

| PAVE | Web | PDF accessibility, with partial fixes | PDF/UA, WCAG | Gradually | German, English | Automatic (partial) | |

| PAC | Desktop | PDF/UA and WCAG compliance checking | PDF/UA, WCAG | Summary or Detailed | German, English | Manual | |

| CCA | Image, Web, PDF, PowerPoint and InDesign files | Desktop | WCAG color contrast checking | WCAG 2.0/2.1/2.2 | Exportable | 12 languages | Manual |

| NVDA | General (Screen Reader) | Desktop | Practical screen reader testing | Not Applicable | Simple | Multiple | Manual |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva, L.; Pimentel, B.; Duarte, B.; Escarpini, R.; Sousa, L.; Cruz, N.; Silva, R. Accessibility by Design: A Systematic Review of Inclusive E-Book Standards, Tools, and Practices. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11173. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411173

Silva L, Pimentel B, Duarte B, Escarpini R, Sousa L, Cruz N, Silva R. Accessibility by Design: A Systematic Review of Inclusive E-Book Standards, Tools, and Practices. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11173. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411173

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Lenardo, Bruno Pimentel, Breno Duarte, Romildo Escarpini, Laisa Sousa, Nicholas Cruz, and Rafael Silva. 2025. "Accessibility by Design: A Systematic Review of Inclusive E-Book Standards, Tools, and Practices" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11173. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411173

APA StyleSilva, L., Pimentel, B., Duarte, B., Escarpini, R., Sousa, L., Cruz, N., & Silva, R. (2025). Accessibility by Design: A Systematic Review of Inclusive E-Book Standards, Tools, and Practices. Sustainability, 17(24), 11173. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411173