The Valuation of Assets as a Non-Monetary Contribution to a Water Management Company

Abstract

1. Introduction

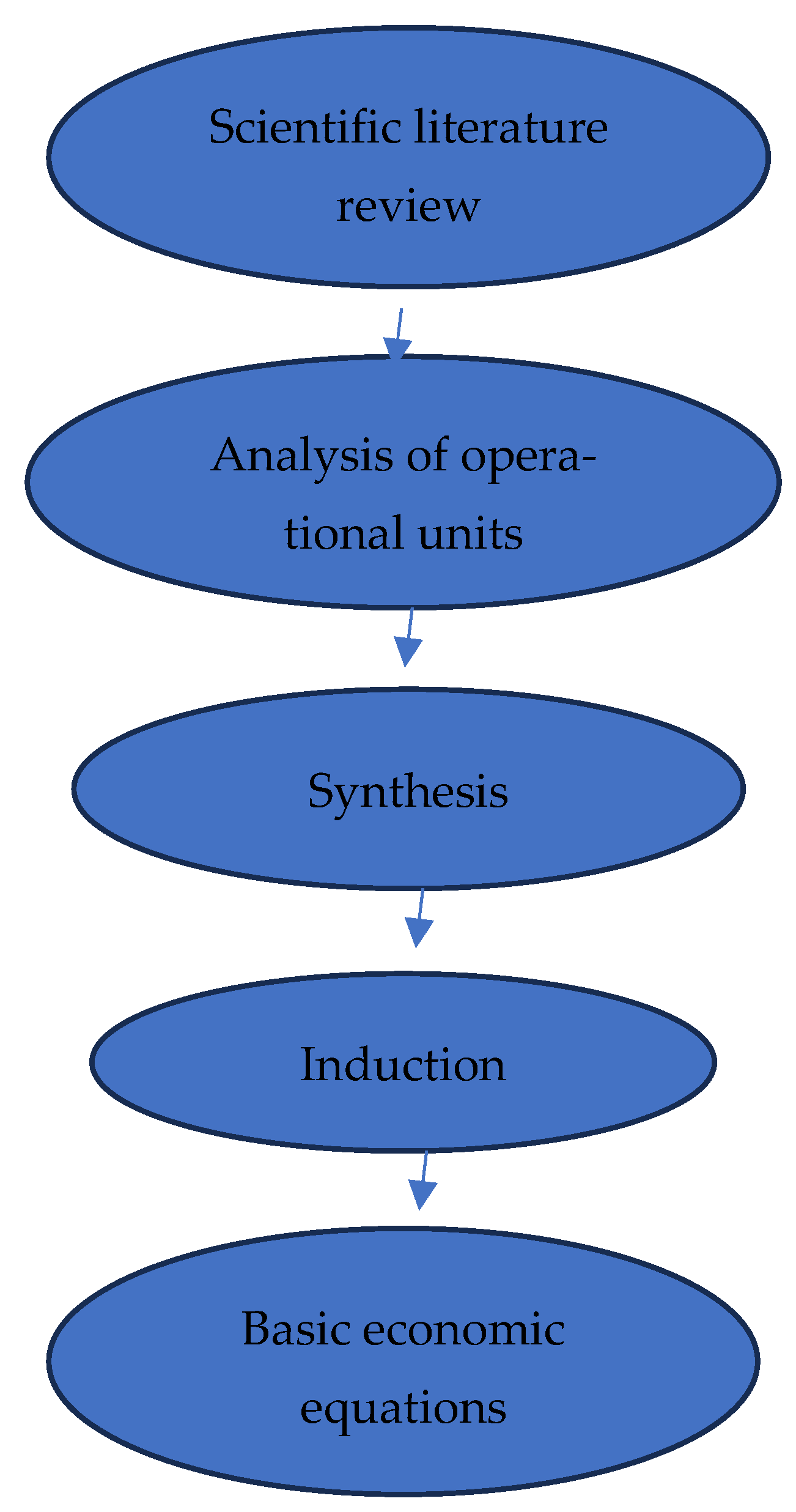

2. Material and Methods

- Asset records—the company’s asset management department.

- Records of fixed and variable costs related to assets—accounting department.

- Records of fixed and variable costs of municipal units related to assets—internal accounting department.

- Records of water supply and sewerage quantities within the company’s water and sewerage services—operational department.

- Records of water supply and sewerage quantities within the municipal units of the company—internal operational department.

- Determination of the number of shares issued for contributed assets in relation to the determined value of the assets—strategic department.

3. Results

- Revenues (from sales),

- Individual types of costs (excluding depreciation).

- Determination of the value of the assets contributed by the municipality,

- Determination of the value of the assets contributed by the municipality as a non-monetary contribution to the WMC.

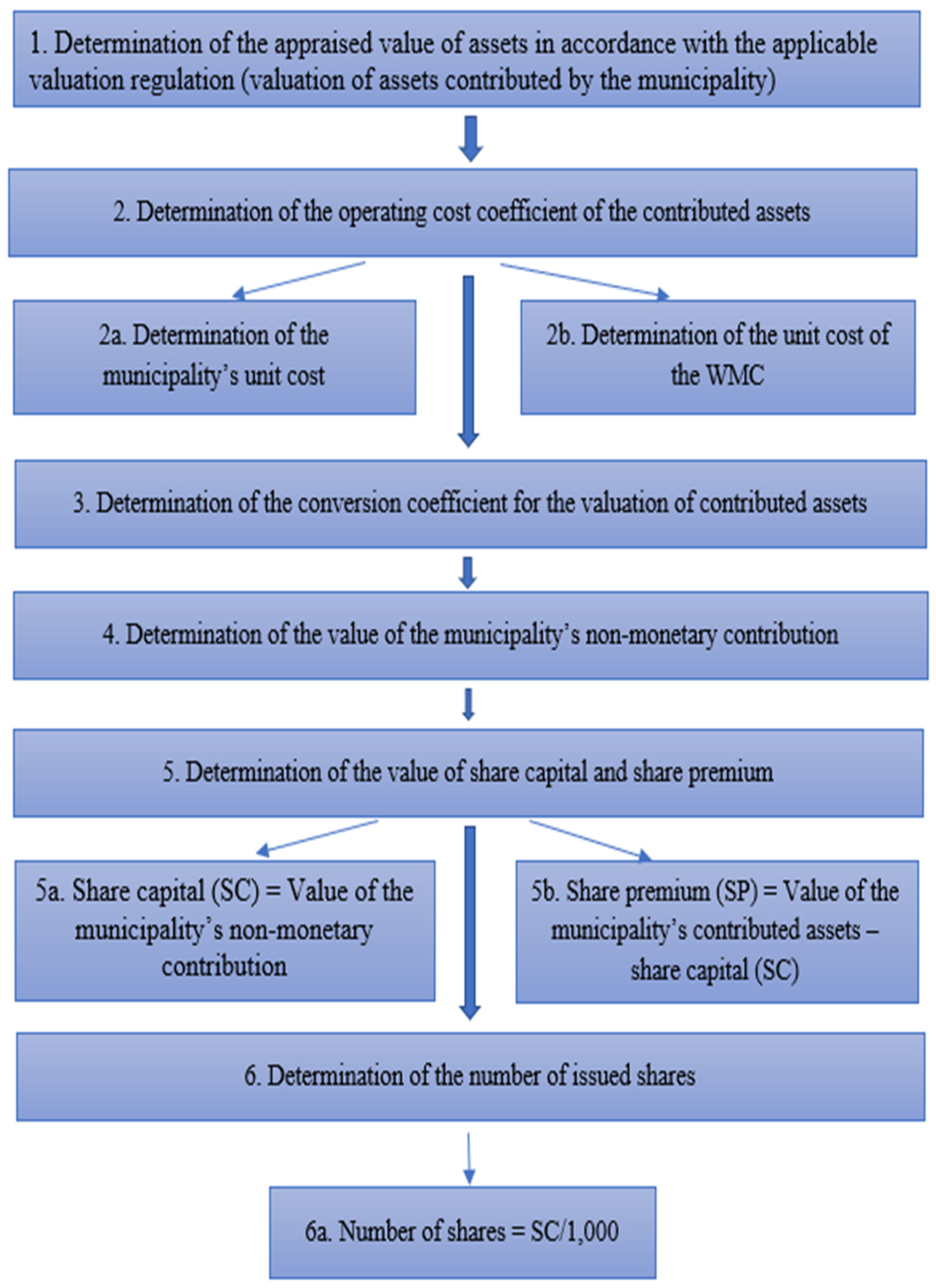

3.1. Determination of the Value of the Municipality’s Contributed Assets

3.2. Determination of the Asset Operation Cost Coefficient

- Direct material,

- Direct wages,

- Other direct costs,

- Indirect costs (production overhead, administrative overhead, depreciation, and the amount of rent for leased assets),

- Other costs.

- (a)

- Division of the total production costs in the WMC’s water/sewerage calculation formula into fixed and variable costs.

- Fixed costs include other depreciation, operating costs, production overhead, and administrative overhead.

- Variable costs include materials, energy, wages, and other direct costs, excluding other depreciation.

- FOC: Full own costs.

- FC: Fixed costs.

- VC: Variable costs.

- M: Material.

- E: Energy.

- W: Wages.

- ODC: Other direct costs (including other depreciation, wastewater treatment plant depreciation, infrastructure asset repairs, infrastructure asset rent, infrastructure asset renewal funds).

- OD: Other depreciation.

- OC: Operating costs.

- FiC: Financial Costs.

- FiR: Financial Revenues.

- POH: Production overhead.

- AOH: Administrative overhead.

- (b)

- Determination of unit fixed costs of water supply/sewerage in CZK/lm for the WMC.

- FCu: Unit fixed costs of the WMC.

- FC: Fixed costs of the WMC.

- OD: Other depreciation costs of the WMC.

- L: Length of the WMC’s network in linear meters.

- (c)

- Determination of unit variable costs of water/sewerage in CZK/m3 for the WMC:

- VCu: Unit variable costs of the WMC.

- VC: Variable costs of the WMC.

- V: Volume of billed water of the WMC in m3.

- (d)

- Determination of total fixed costs of water/sewerage for the municipality in CZK.

- FCm: Full fixed costs of the municipality.

- FCu: Unit fixed costs of the WMC.

- Lm: Length of the municipality’s contributed water/sewerage network in lm.

- ODm: Depreciation of the municipality’s contributed assets.

- (e)

- Determination of the amount of variable costs of water/sewerage services for the municipality in CZK:

- VCm: Variable cost of the municipality.

- VCu: Unit variable cost of the WMC.

- Vm: Volume of water consumed by the municipality in m3.

- (f)

- Determination of the full own costs of water/sewerage services for the municipality in CZK.

- FOCm: Full own costs of the municipality.

- FCm: Fixed costs of the municipality.

- VCm: Variable costs of the municipality.

- (g)

- Determination of the unit costs of water/sewerage services for the municipality (UCm) in CZK/m3.

- UCm: Unit cost of water/sewerage services for the municipality.

- FOCm: Full own costs of the municipality.

- Vm: Volume of water consumed by the municipality in m3.

- (h)

- Determination of the unit costs of the WMC (UCWMC) in CZK/m3.

- UCWMC: Unit cost of water/sewerage services of the WMC.

- FOC: Full own costs of water/sewerage services of the WMC.

- V: Volume of water supplied or discharged by water supply and sewerage network of the WMC in m3.

- (i)

- Determination of the asset cost coefficient of the municipality.

- ACC: Asset cost coefficient.

- UCm: Unit costs of the municipality in CZK/m3.

- UCWMC: Unit costs of the WMC in CZK/m3.

3.3. Determination of the Conversion Coefficient for the Value of Contributed Assets

- COc: Conversion coefficient.

- ACc: Asset cost coefficient determined in point (i).

- COc < 0.000 K: The value of the contributed assets will always be multiplied by a conversion coefficient of 0.3.

- 0.000 ≤ COc < 0.500: The value of the contributed assets will always be multiplied by a conversion coefficient of 0.5.

- 0.500 ≤ COc < 1.000: The value of the contributed assets will always be multiplied by the calculated conversion coefficient.

- COc ≥ 1.000: The value of the contributed assets will always be multiplied by a conversion coefficient of 1.0.

3.4. Determination of the Value of the Municipality’s Non-Monetary Contribution

- VNCm: Value of the non-monetary contribution of the municipality.

- VACm: Value of the assets contributed by the municipality.

- COc: Conversion coefficient.

3.5. Determination of the Value of the Share Capital and Share Premium

- SC: Share capital of the WMC.

- VNCm: Value of the non-monetary contribution of the municipality.

- SP: Share premium.

- VACm: Value of the assets contributed by the municipality.

- SC: Share capital of the WMC.

3.6. Determination of the Number of Issued Shares

4. Case Study

4.1. Determination of the Value of Assets Contributed by Individual Municipalities

4.2. Determination of the Cost Coefficient

4.3. Determination of the Conversion Coefficient

4.4. Determination of the Value of Municipal Non-Monetary Contributions

4.5. Determination of Share Capital and Share Premium Values

4.6. Determination of the Number of Issued Shares

- The value of the infrastructural assets, related to the relevant location and time, based on market value;

- The cost structure of the assets contributed by the municipalities, represented by fixed and variable costs;

- The performance of the contributed assets by the municipalities, represented by water consumption and sewerage discharge.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | Asset cost coefficient |

| ACc | Asset cost coefficient determined in point i) |

| AOH | Administrative overhead |

| COc | Conversion coefficient |

| CZK | Czech crown |

| E | Energy |

| FC | Fixed costs |

| FCm | Fixed costs of the municipality |

| FCu | Unit fixed costs of the WMC |

| FiC | Financial Costs |

| FiR | Financial Revenues |

| FOC | Full own costs |

| FOCm | Full own costs of the municipality |

| L | Length of the WMC’s network in linear meters |

| Lm | Length of the municipality’s contributed water/sewerage network in lm |

| M | Material |

| OC | Operating costs |

| OD | Other depreciation |

| ODC | Other direct costs (including other depreciation, wastewater treatment plant depreciation, infrastructure asset repairs, infrastructure asset rent, infrastructure asset renewal funds) |

| ODm | Depreciation of the municipality’s contributed assets |

| POH | Production overhead |

| SC | Share capital of the WMC |

| SP | Share premium |

| UCm | Unit cost of water/sewerage services for the municipality |

| UCm | Unit costs of the municipality in CZK/m3 |

| UCWMC | Unit cost of water/sewerage services of the WMC |

| UCWMC | Unit costs of the WMC in CZK/m3 |

| V | Volume of water supplied or discharged by water supply and sewerage network of the WMC in m3 |

| VACm | Value of the assets contributed by the municipality |

| VC | Variable costs |

| VCm | Variable cost of the municipality |

| VCu | Unit variable costs of the WMC |

| Vm | Volume of water consumed by the municipality in m3 |

| VNCm | Value of the non-monetary contribution of the municipality |

| W | Wages |

| WMC | Water Management Company |

References

- Ministry of Agriculture of the Czech Republic. Available online: https://mze.gov.cz/public/portal/mze/voda/osveta-a-publikace/publikace-a-dokumenty/modre-zpravy/modra-zprava-2024 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Ministry of Agriculture of the Czech Republic. Available online: https://mze.gov.cz/public/portal/mze/-a62828---bD_x83-o/vodovody-a-kanalizace-ceske-republiky-2023?_linka=a621442 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Vitkova, E. Management of Long-Term Assets of Water Management Companies. Habilitation Thesis, BUT, Brno, Czech Republic, 2024. Available online: https://www.vut.cz/uredni-deska/habilitace?fakulta=3&stav=&textnajit=V%C3%ADtkov%C3%A1&znak=v (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Yazdani, A.; Jeffrey, P. Complex Network Analysis Of Water Distribution Systems. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2011, 21, 016111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilarinho, H.; D’iNverno, G.; Nóvoa, H.; Camanho, A.S. The Measurement of Asset Management Performance of Water Companies. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2023, 87, 101545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidis, G.; Ioannidis, E.; Makris, G.; Antoniou, I.; Varsakelis, N. Competitive Conditions In Global Value Chain Networks: An Assessment Using Entropy And Network Analysis. Entropy 2020, 22, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Deng, Q.; Li, X.; Shao, Z. Fine Me If You Can: Fixed Asset Intensity And Enforcement Of Environmental Regulations In China. Regul. Gov. 2022, 16, 983–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocok, V.; Hinke, J.; Abrham, J. Leasing From The Perspective Of Environmental Management And Its Influence On Business Performance. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1272816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabor, J. Implementation of the Sustainable Development Concept in Manufacturing Companies. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 6, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuken, R.; Eijkman, J.; Savic, D.; Hummelen, A.; Blokker, M. Twenty Years of Asset Management Research for Dutch Drinking Water Utilities. Water Sci. Technol. Water Supply 2020, 20, 2941–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.Q.A.; Lai, F.-W.; Shad, M.K.; Hamad, S.; Ellili, N.O.D. Exploring the Effect of Enterprise Risk Management For Esg Risks Towards Green Growth. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2025, 74, 224–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laucelli, D.B.; Enriquez, L.V.; Ariza, A.D.; Ciliberti, F.G.; Berardi, L.; Giustolisi, O. A Digital Water Strategy Based on the Digital Water Service Concept to Support Asset Management in a Real System. J. Hydroinformatics 2023, 25, 2004–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masyita, D.; Susanti, L. Analysis of Risk-Based Asset Management Plan to Increase Performance of Water Local Company. J. Bisnis Dan Manaj. 2019, 20, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tscheikner-Gratl, F.; Caradot, N.; Cherqui, F.; Leitão, J.P.; Ahmadi, M.; Langeveld, J.G.; Le Gat, Y.; Scholten, L.; Roghani, B.; Rodríguez, J.P.; et al. Sewer Asset Management—State of the Art and Research Needs. Urban Water J. 2019, 16, 662–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caradot, N.; Sonnenberg, H.; Kropp, I.; Ringe, A.; Denhez, S.; Hartmann, A.; Rouault, P. The Relevance of Sewer Deterioration Modelling to Support Asset Management Strategies. Urban Water J. 2017, 14, 1007–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleidorfer, M.; Möderl, M.; Tscheikner-Gratl, F.; Hammerer, M.; Kinzel, H.; Rauch, W. Integrated Planning of Rehabilitation Strategies for Sewers. Water Sci. Technol. 2013, 68, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruaset, S.; Rygg, H.; Sægrov, S. Reviewing the Long-Term Sustainability of Urban Water System Rehabilitation Strategies with an Alternative Approach. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Act No. 151/1997 Coll.; On Property Valuation and Amendments to Certain Acts. Collection of Laws: Prague, Czech Republic, 1997.

- Decree No. 441/2013 Coll.; Implementing the Property Valuation Act. Collection of Laws: Prague, Czech Republic, 2013.

- Act No. 526/1990 Coll.; Price Law. Collection of Laws: Prague, Czech Republic, 1990.

- Radović, M.; Vitormir, J.; Popović, S.; Stojanović, A. The Importance of Establishing Financial Valuation of Fixed Assets in Public Companies Whose Founders Are Local Self-Government Units in the Republic of Serbia. Eng. Econ. 2023, 34, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkulipa, L.V. Analysis of the Methodology of Fixed Assets in Accordance With Ias 16 “Fixed Assets” and P(S)Bu 7 “Fixed Assets”: Theory and Practice. Sci. Bull. Natl. Acad. Stat. Account. Audit. 2018, 4, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chyrva, O.H.; Demchenko, T.A.; Kovalev, L.E.; Mykhailovyna, S.O. Role of Main Activities in Formation of the Capital of an Enterprise, Their Evaluation and Control. Financ. Crédit Act. Probl. Theory Pr. 2019, 3, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rady, A.; Meshreki, H.; Ismail, A.; Núñez, L. Variations in Valuation Methodologies and the Cost of Capital: Evidence from Mena Countries. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2019, 55, 2106–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawron, K.; Yakymchuk, A.; Tyvonchuk, O. The Bankrupt Entity’s Assets Valuation Methods: Polish Approach. Investig. Manag. Financ. Innov. 2019, 16, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Yamani, S.; Hajji, R.; Billen, R.; Ohori, K.A.; van der Vaart, J.; Hakim, A.; Stoter, J. Towards Extending Citygml for Property Valuation: Property Valuation Ade. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, X-4/W5-2024, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setijono, D. Behavioural shortcomings to avoid in asset valuation using comparable method—Insights from a survey experiment. J. Prop. Investig. Financ. 2025, 43, 340–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čibera, R.; Krabec, T. Asset Valuation in Insolvency in the Czech Republic: An Empirical Investigation. Int. Adv. Econ. Res. 2017, 23, 135–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fülöp, Á.-Z.; Bakó, K.-E.; Stanciu, A. Separation of Fixed and Variable Costs from Mixed Costs at a Water and Sewerage Operator. Analele Univ. Din Oradea. Ştiinţe Econ. 2021, 30, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, I.; Saldanha-da-Gama, F. The Impact of Fixed and Variable Costs in a Multi-Skill Project Scheduling Problem: An Empirical Study. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2014, 72, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.T. Fixed and Variable Costs: When Accounting is the Opposite of Cash Flow Reality. J. Corp. Account. Financ. 2016, 27, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabbush, V. Understanding Costs: How Cbos Can Build Business Acumen for Future Partnerships. Generations 2018, 42, 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Parmacli, D.; Soroka, L.; Bakhchivanji, L. Methodical Bases of Graduation of Indicators of Efficiency of Realized Production in Agriculture. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2019, 5, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machka, M.; Beran, T. Monitoring of Material and Energy Flows: Integration of Mfca System with an Open Input–Output Model Separating Variable and Fixed Costs. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2024, 29, 1053–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, P.; Skally, M.; Duffy, F.; Farrelly, M.; Gaughan, L.; Flood, P.; McFadden, E.; Fitzpatrick, F. Evaluation of Fixed and Variable Hospital Costs due to Clostridium Difficile Infection: Institutional Incentives and Directions for Future Research. J. Hosp. Infect. 2017, 95, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, K.; Defourny, N.; Tunstall, D.; Cosgrove, V.; Kirkby, K.; Henry, A.; Lievens, Y.; Hall, P. Variable and Fixed Costs in Nhs Radiotherapy; Consequences for Increasing Hypo Fractionation. Radiother. Oncol. 2022, 166, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyakova, O.V. Development of a Methodology for Sharing the Enterprise Total Costs into the Fixed and Variable Components in the Cost-Management Tools’ Improvement. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 913, 52024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktavia, M.; Aman, A.; Hanum, F. Utilization of Groundwater for the Bottled Water Industry by Minimizing Fixed and Variable Cost. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 299, 12036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synek, M. Manažerská Ekonomika, 4., Aktualiz. a Rozš. Vyd. In Expert; Grada: Praha, Czech Republic, 2007; Available online: http://www.digitalniknihovna.cz/mzk/uuid/uuid:f3007bd0-e42b-11e5-8d5f-005056827e51 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Máče, M. Účetnictví a Finanční Řízení. Grada. 2013. Available online: https://www.bookport.cz/kniha/ucetnictvi-a-financni-rizeni-2224/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Irwin, D. Finanční řízení. In Cesta K Finanční Svobodě; Profess Consulting: Prague, Czech Republic, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jegers, M.; Buts, C.; Van Puyvelde, S. Welfare Effects of Variable and Fixed Cost Subsidies in Profit, Non-Profit and Mixed Markets. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2024, 45, 4138–4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Municipality | Type of Intended Contributed Infrastructural Asset |

|---|---|

| 1 | Water supply infrastructure assets |

| 2 | Water supply infrastructure assets |

| 3 | Sewerage infrastructure assets |

| 4 | Water supply infrastructure assets |

| 5 | Sewerage and water supply infrastructure assets |

| 6 | Water supply infrastructure assets |

| 7 | Sewerage and water supply infrastructure assets |

| 8 | Sewerage infrastructure assets |

| 9 | Water supply infrastructure assets |

| 10 | Sewerage infrastructure assets |

| 11 | Sewerage and water supply infrastructure assets |

| Type of Infrastructure Network | Water Supply | Water Supply | Sewerage Network | Water Supply | Sewerage Network | Water Supply | Water Supply | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | VaK | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| A.—thous. m3 of water supplied | 7033.00 | |||||||

| B.—thous m3 of sewerage discharged | 7680.00 | |||||||

| C.—Full own costs—WATER SUPPLY CHARGES | 207,142.00 | |||||||

| D.—Total own costs—SEWERAGE DISCHARGE CHARGES | 269,549.00 | |||||||

| Average Cost—Water Supply charges (C/A) | 29.45 | 55.57 | 310.13 | 22.03 | 131.93 | 22.96 | ||

| Average Cost—Sewerage charges (D/B) | 35.10 | 232.19 | 35.76 | |||||

| Selling price by WMC—water supply charges | 30.61 | |||||||

| Selling Price by WMC—sewerage discharge charges | 38.96 | |||||||

| Municipality cost coefficient | 1.89 | 10.53 | 6.62 | 0.75 | 1.02 | 4.48 | 0.78 | |

| Increase in municipality price compared to WMC (%) | 88.67% | 952.96% | 561.56% | −25.19% | 1.88% | 347.95% | −22.06% | |

| Conversion coefficient | 0.11 | −8.53 | −4.62 | 1.25 | 0.98 | −2.48 | 1.22 | |

| Input value of municipality assets | 992,000 | 4,999,586 | 1,368,504 | 489,940 | 3,644,628 | 382,024 | 5,823,092 | |

| Municipal assets contributed | 968.90 | 1407.50 | 159.00 | 309.40 | 867.80 | 175.40 | 1104.30 | |

| Value of municipal non-monetary contribution | 496,000 | 1,499,876 | 410,551 | 489,940 | 3,575,968 | 114,607 | 5,823,092 | |

| Share capital value | 496,000 | 1,499,876 | 410,551 | 489,940 | 3,575,968 | 114,607 | 5,823,092 | |

| Share premium value | 496,000 | 3,499,710 | 957,953 | 0 | 68,660 | 267,417 | 0 | |

| Number of shares | 496 | 1500 | 411 | 490 | 3 576 | 115 | 5823 | |

| % of municipality non-monetary contribution relative to input asset value | 50.00% | 30.00% | 30.00% | 100.00% | 98.12% | 30.00% | 100.00% | |

| Type of Infrastructure Network | Water Supply | Sewerage Network | Sewerage Network | Sewerage Network | Water Supply | Sewerage Network | Water Supply | Sewerage Network | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | VaK | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |||

| A.—thous. m3 of water supplied | 7033.00 | ||||||||

| B.—thous m3 of sewerage discharged | 7680.00 | ||||||||

| C.—Full own costs—WATER SUPPLY CHARGES | 207,142.00 | ||||||||

| D.—Total own costs—SEWERAGE DISCHARGE CHARGES | 269,549.00 | ||||||||

| Average Cost—Water Supply charges (C/A) | 29.45 | 303.41 | 109.04 | 88.45 | |||||

| Average Cost—Sewerage charges (D/B) | 35.10 | 281.50 | 206.54 | 136.79 | 144.23 | 206.06 | |||

| Selling price by WMC—water supply charges | 30.61 | ||||||||

| Selling Price by WMC—sewerage discharge charges | 38.96 | ||||||||

| Municipality cost coefficient | 10.30 | 8.02 | 5.88 | 3.90 | 3.70 | 4.11 | 3.00 | 5.87 | |

| Increase in municipality price compared to WMC (%) | 930.17% | 702.05% | 488.47% | 289.74% | 270.21% | 310.95% | 200.30% | 487.10% | |

| Conversion coefficient | −8.30 | −6.02 | −3.88 | −1.90 | −1.70 | −2.11 | −1.00 | −3.87 | |

| Input value of municipality assets | 652,434 | 900,000 | 40,409,347 | 3,140,500 | 3,264,500 | 5,790,840 | 1,736,041 | 77,962 | |

| Municipal assets contributed | 276.00 | 464.80 | 6078.40 | 553.90 | 580.80 | 3549.30 | 1402.00 | 22.80 | |

| Value of municipal non-monetary contribution | 195,730 | 270,000 | 12,122,804 | 942,150 | 979,350 | 1,737,252 | 520,812 | 23,389 | |

| Share capital value | 195,730 | 270,000 | 12,122,804 | 942,150 | 979,350 | 1,737,252 | 520,812 | 23,389 | |

| Share premium value | 456,704 | 630,000 | 28,286,543 | 2,198,350 | 2,285,150 | 4,053,588 | 1,215,229 | 54,573 | |

| Number of shares | 196 | 270 | 12,123 | 942 | 979 | 1737 | 521 | 23 | |

| % of municipality non-monetary contribution relative to input asset value | 30.00% | 30.00% | 30.00% | 30.00% | 30.00% | 30.00% | 30.00% | 30.00% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vítková, E.; Korytárová, J.; Kocourková, G. The Valuation of Assets as a Non-Monetary Contribution to a Water Management Company. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11171. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411171

Vítková E, Korytárová J, Kocourková G. The Valuation of Assets as a Non-Monetary Contribution to a Water Management Company. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11171. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411171

Chicago/Turabian StyleVítková, Eva, Jana Korytárová, and Gabriela Kocourková. 2025. "The Valuation of Assets as a Non-Monetary Contribution to a Water Management Company" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11171. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411171

APA StyleVítková, E., Korytárová, J., & Kocourková, G. (2025). The Valuation of Assets as a Non-Monetary Contribution to a Water Management Company. Sustainability, 17(24), 11171. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411171