Recent Advances in Fly Ash- and Slag-Based Geopolymer Cements

Abstract

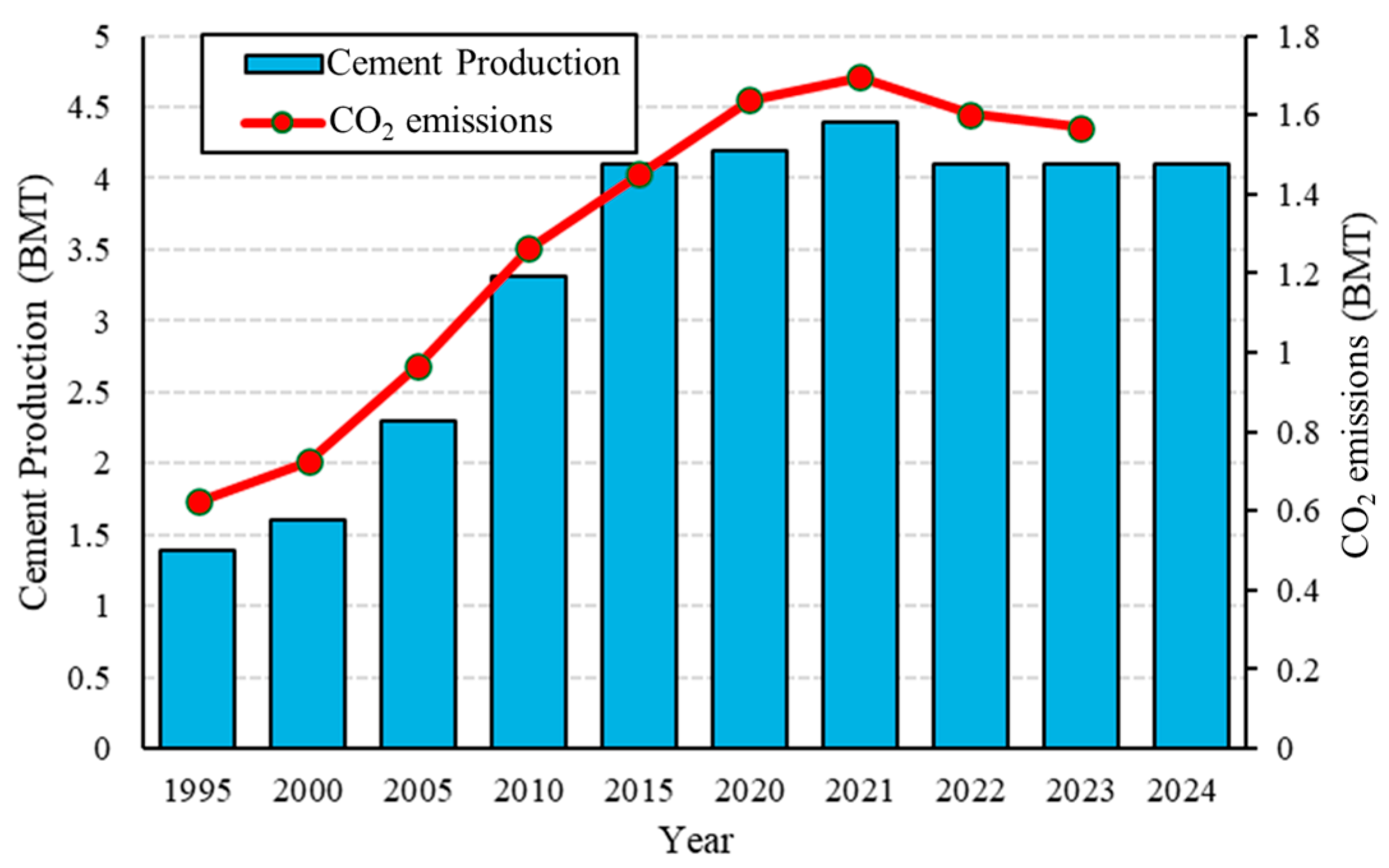

1. Introduction

Research Significance and Contribution

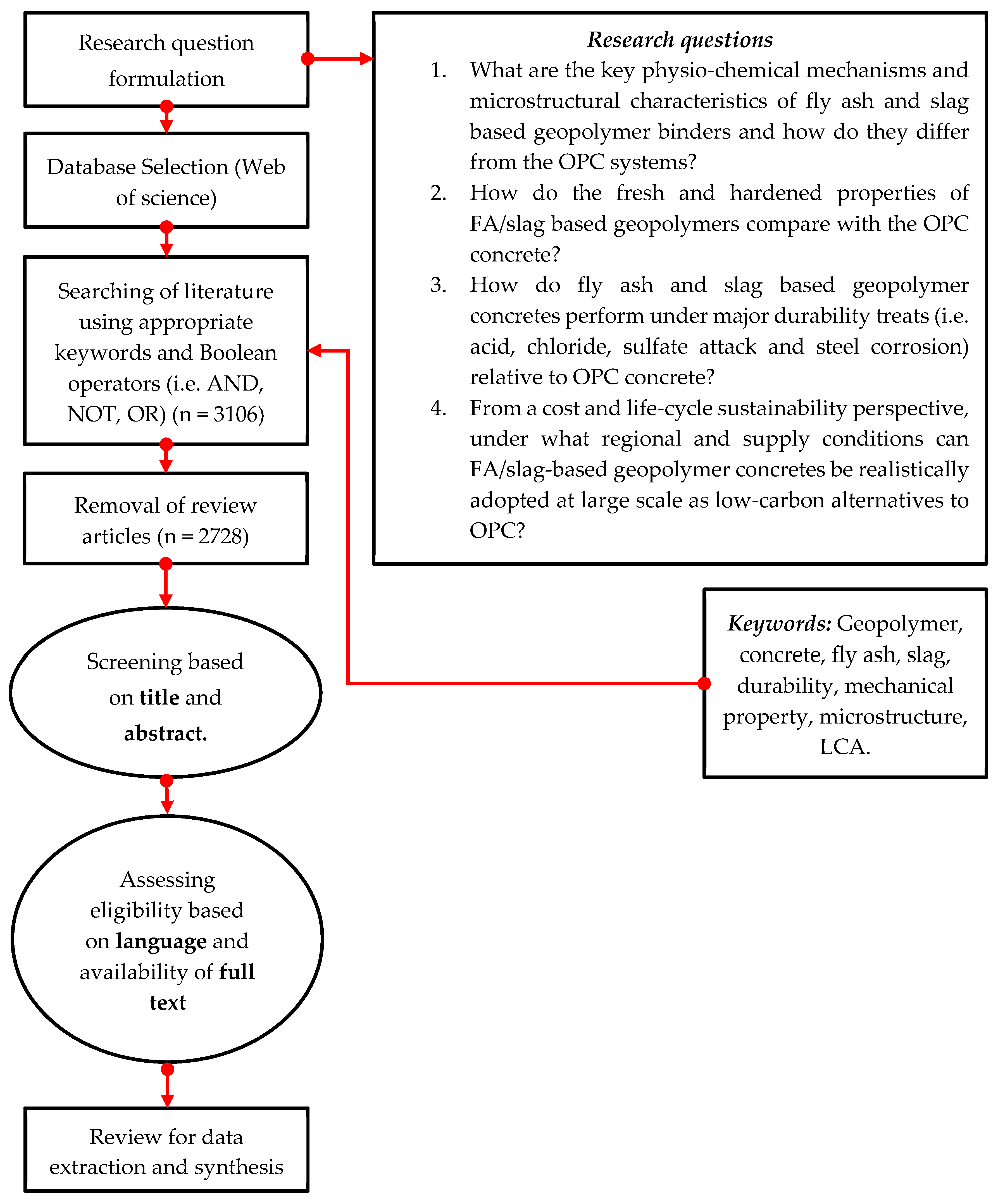

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Questions

- What are the key physio-chemical mechanisms and microstructural characteristics of fly ash- and slag-based geopolymer binders, and how do they differ from OPC systems?

- How do the fresh and hardened properties of FA/slag-based geopolymers compare with OPC concrete?

- How do fly ash- and slag-based geopolymer concretes perform under major durability treats (i.e., acid, chloride, sulfate attack, and steel corrosion) relative to OPC concrete?

- From a cost and life-cycle sustainability perspective, under what regional and supply conditions can FA/slag-based geopolymer concretes be realistically adopted at a large scale as low-carbon alternatives to OPC?

2.2. Database Selection and Literature Search

2.3. Literature Screening and Assessment

- Form of geopolymer materials (i.e., paste, mortar, and concrete);

- Type of pre-cursor material (i.e., fly ash, slag, fly ash + slag);

- Chemical and microstructural parameters based on XRF, XRD, FTIR, TGA, SEM, and TEM tool data;

- Physical properties of constituent materials based on density, water absorption, porosity;

- Fresh properties based on workability.

- Hardened properties based on compressive strength, tensile strength, flexural strength, modulus of elasticity.

- Durability properties based on resistance to acid, sulfate, chloride, and corrosion;

- Environmental impact based on regional variation.

- Cost of production based on regional variation.

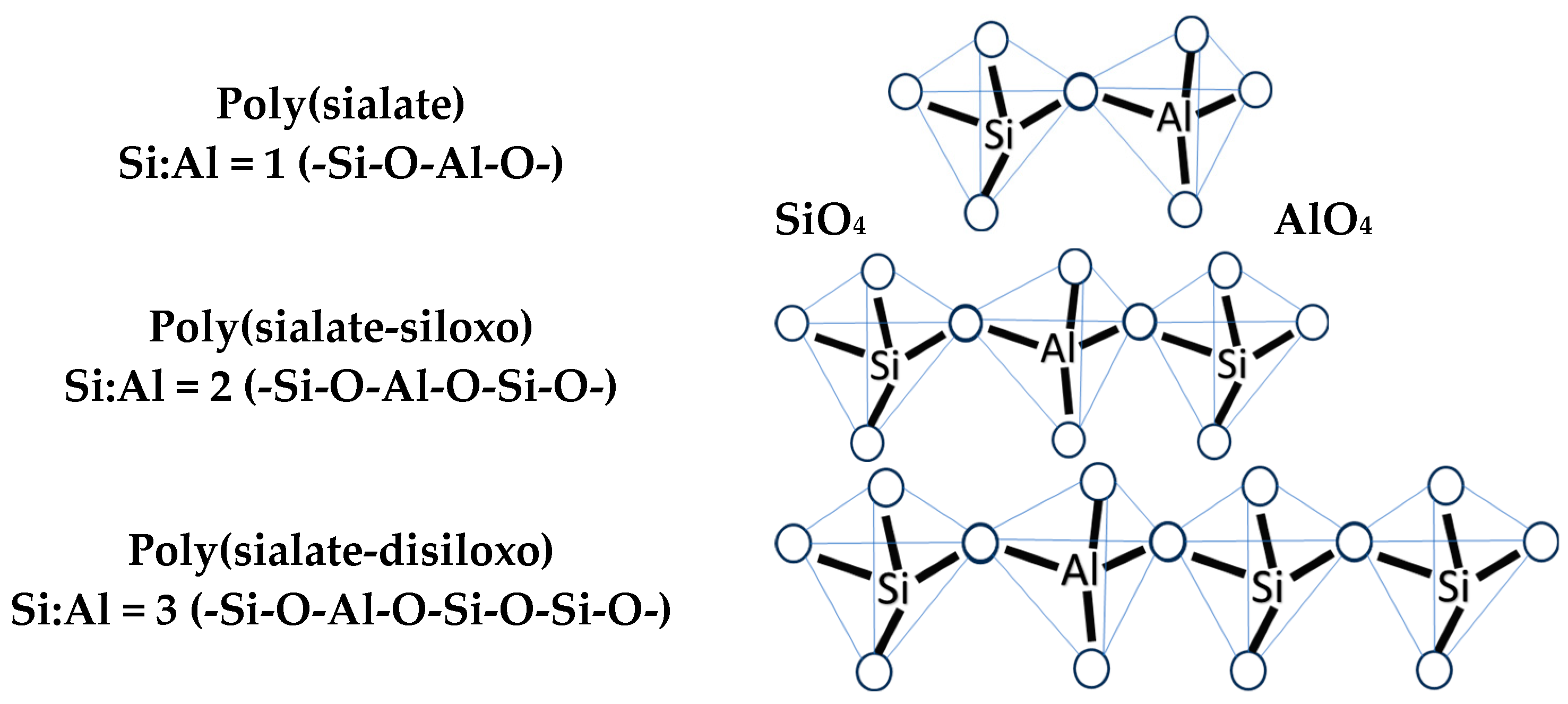

3. Background and Mechanism of GPC

3.1. Background of GPC

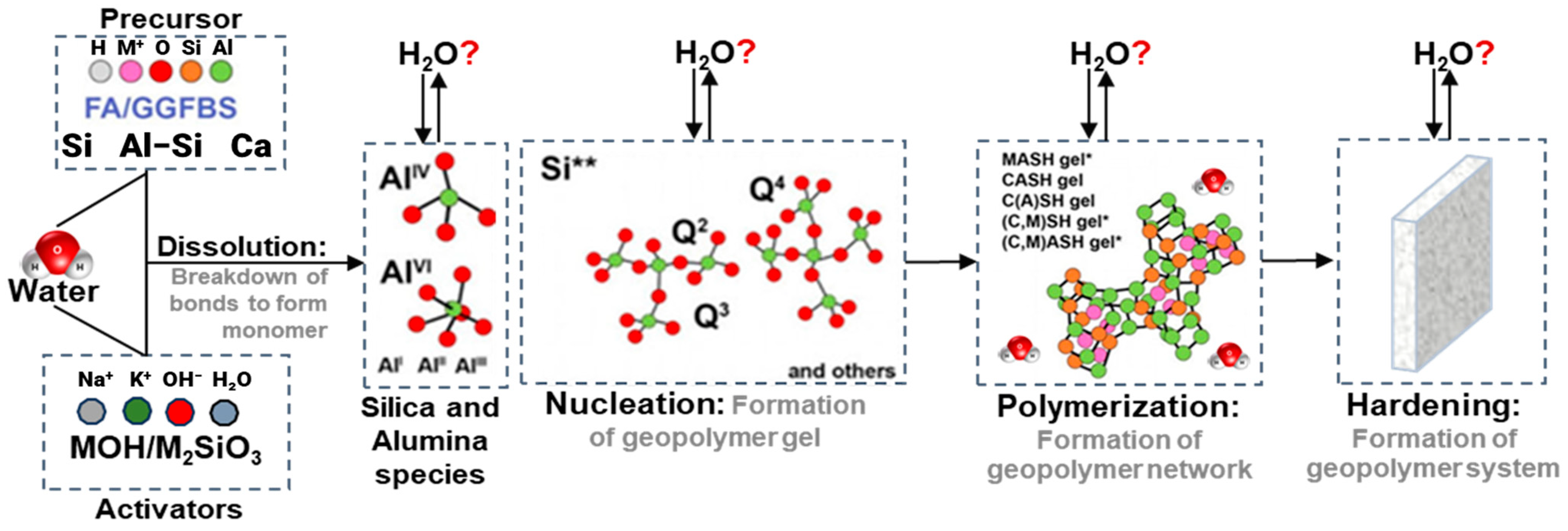

3.2. Mechanism of Geopolymerization

4. Physio-Chemical Characterization of GPC

4.1. Chemical Properties of FA-Based GPC

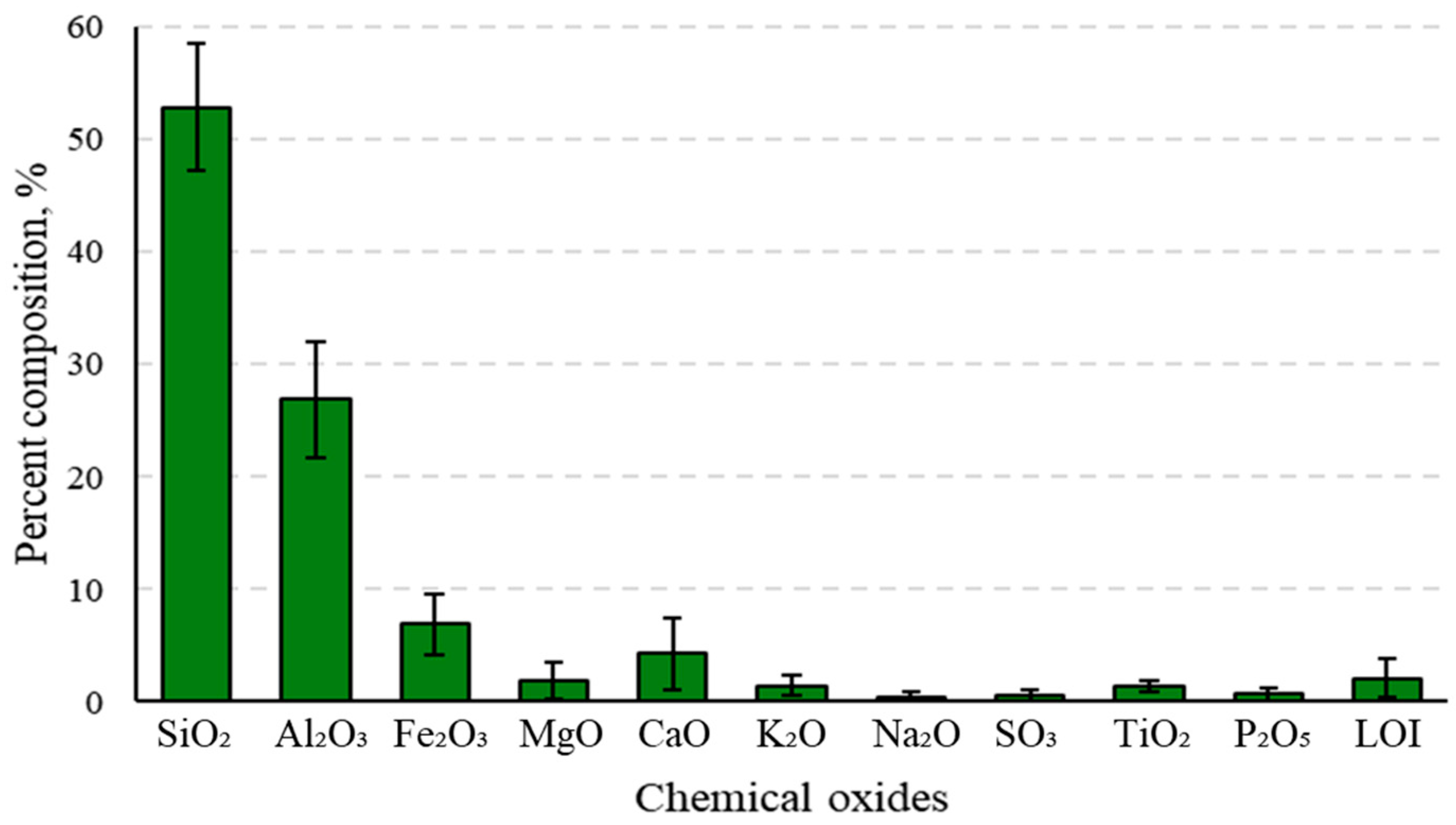

4.1.1. X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF)

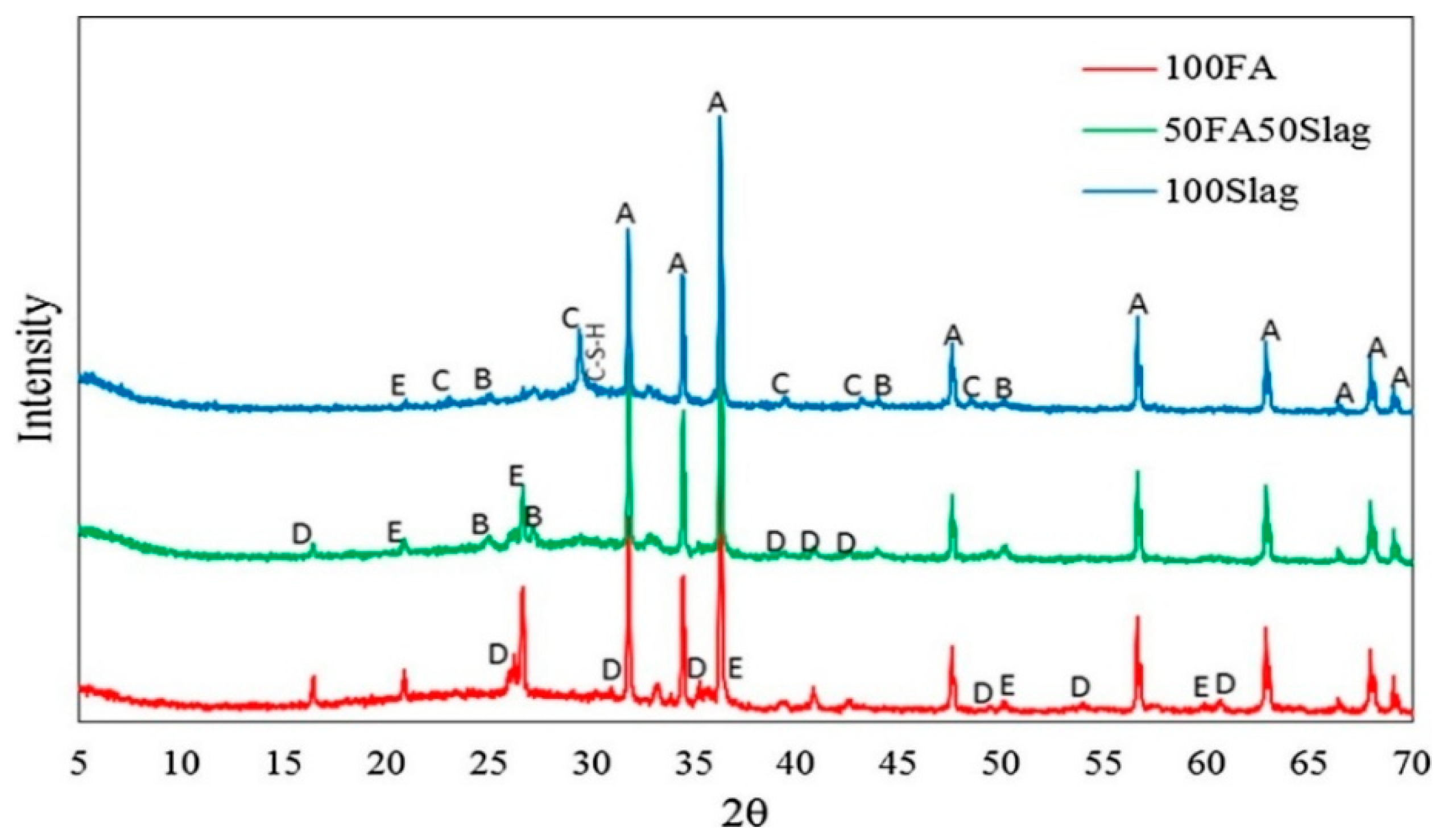

4.1.2. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

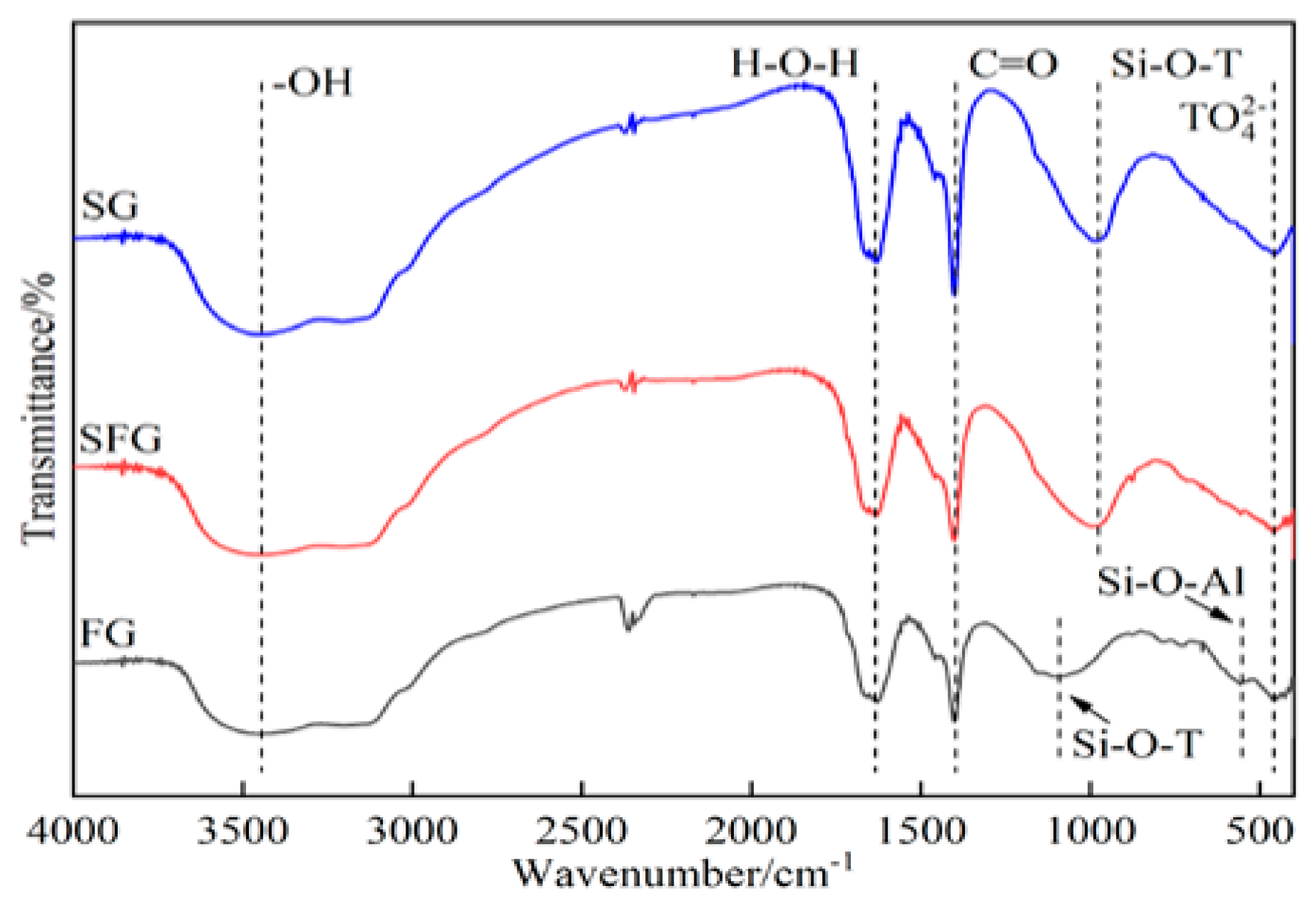

4.1.3. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

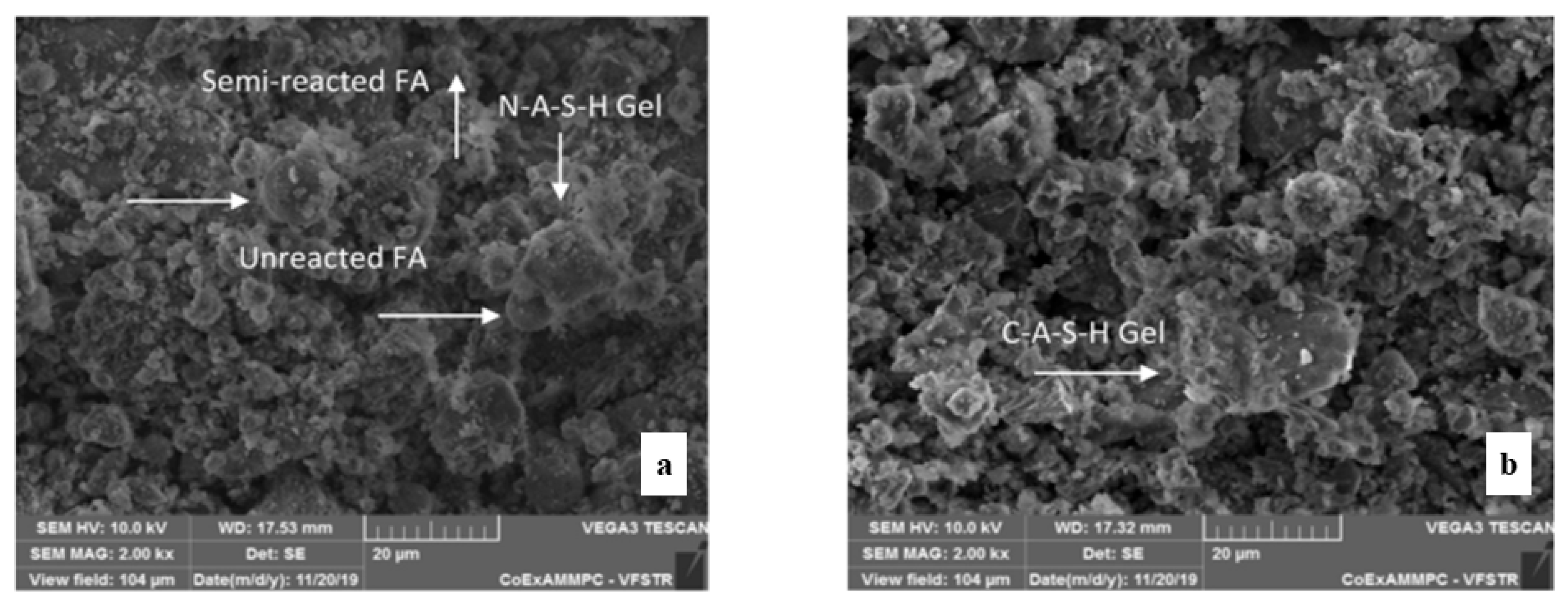

4.1.4. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

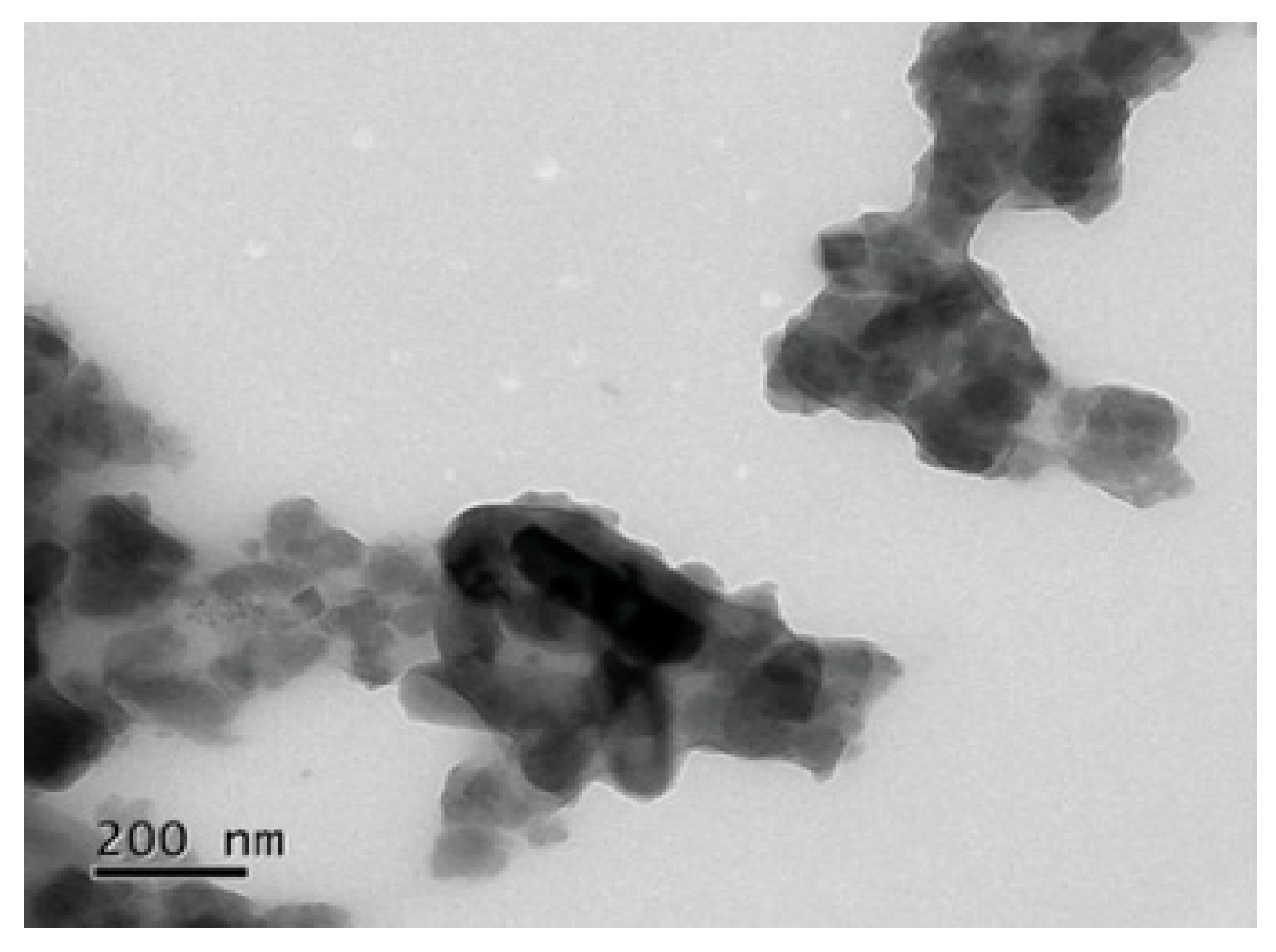

4.1.5. Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM)

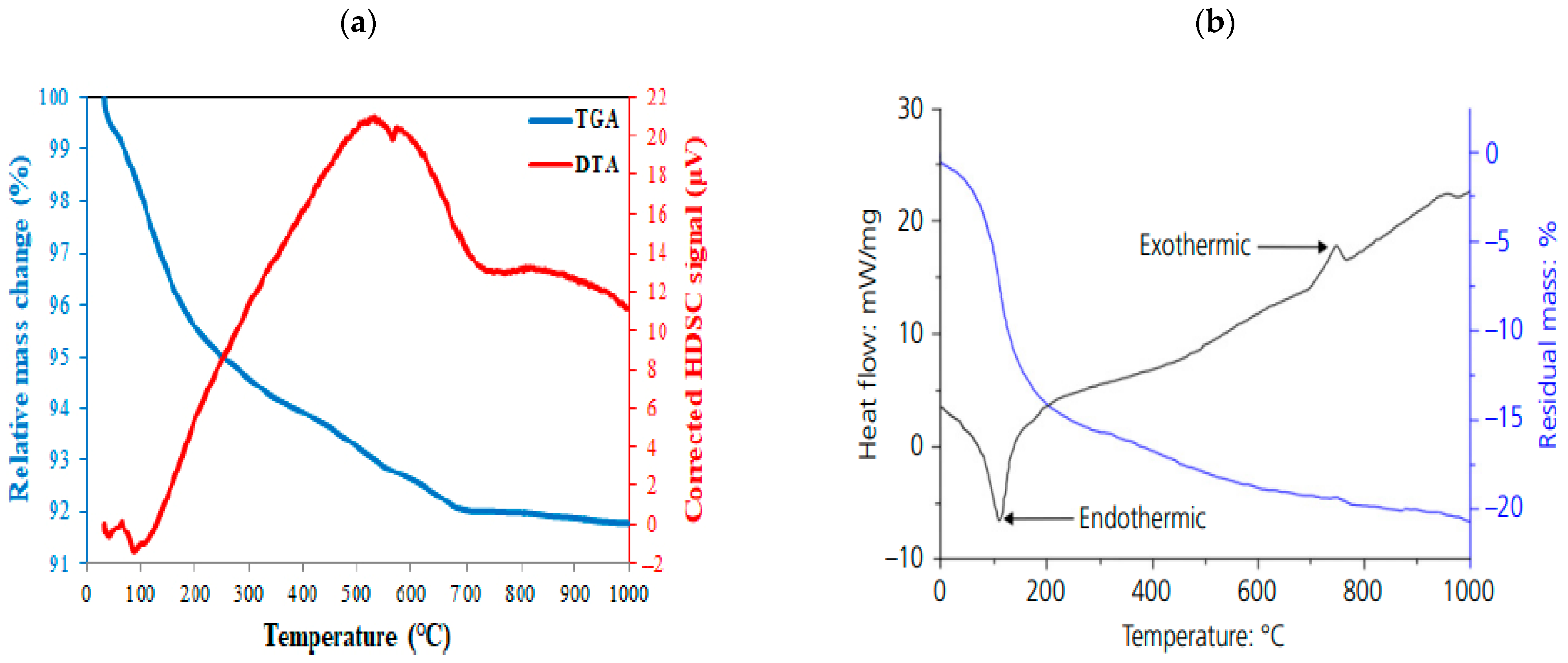

4.1.6. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

4.2. Physical Properties of FA-Based GPC

5. Fresh and Hardened Properties of FA-Based GPC

5.1. Workability

5.2. Hardened Properties

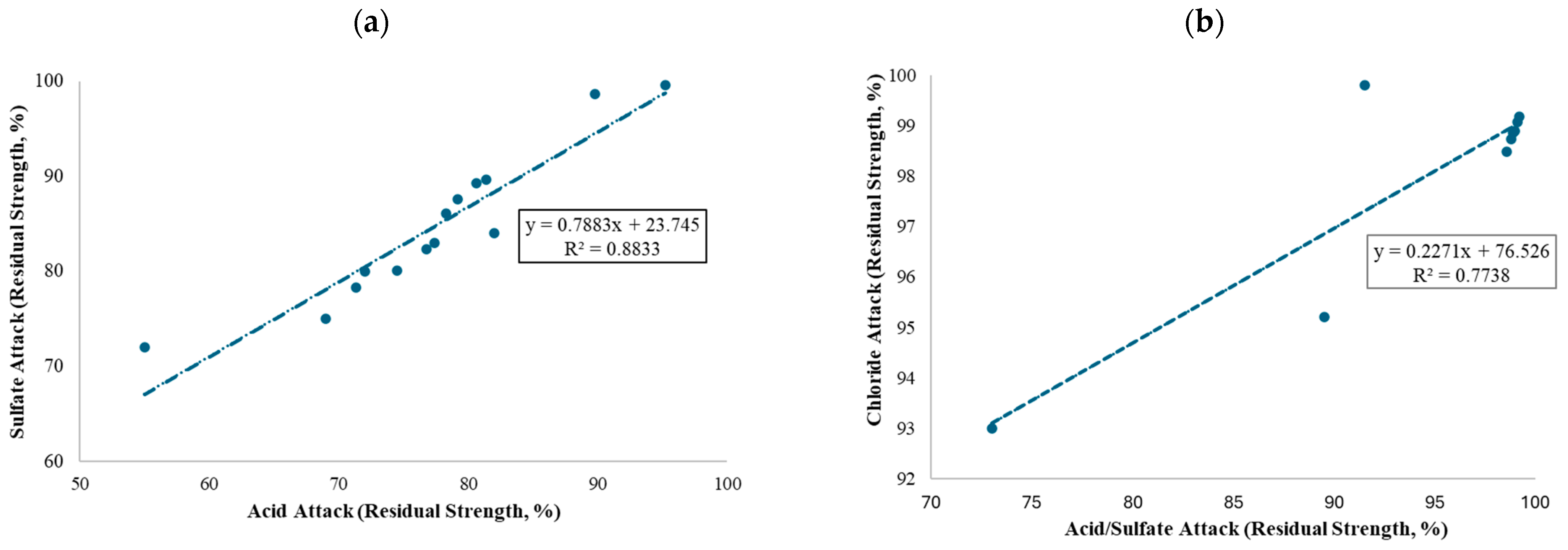

6. Durability Properties of FA-Based Geopolymer

6.1. Resistance to Acid Attack

6.2. Resistance to Chloride Attack

6.3. Resistance to Sulfate Attack

6.4. Resistance to Corrosion

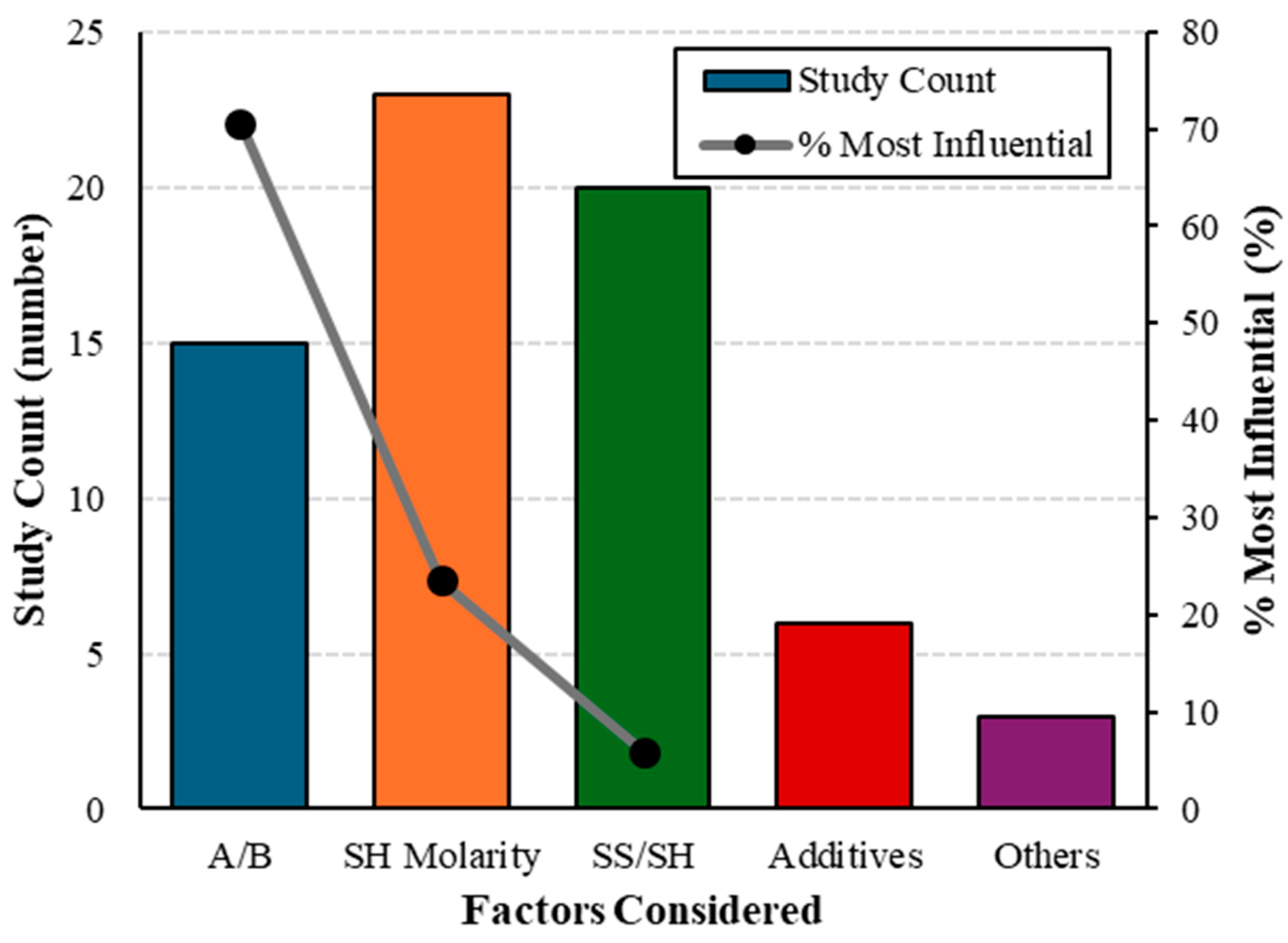

7. Methodological Quality and Limitations of Reviewed Articles

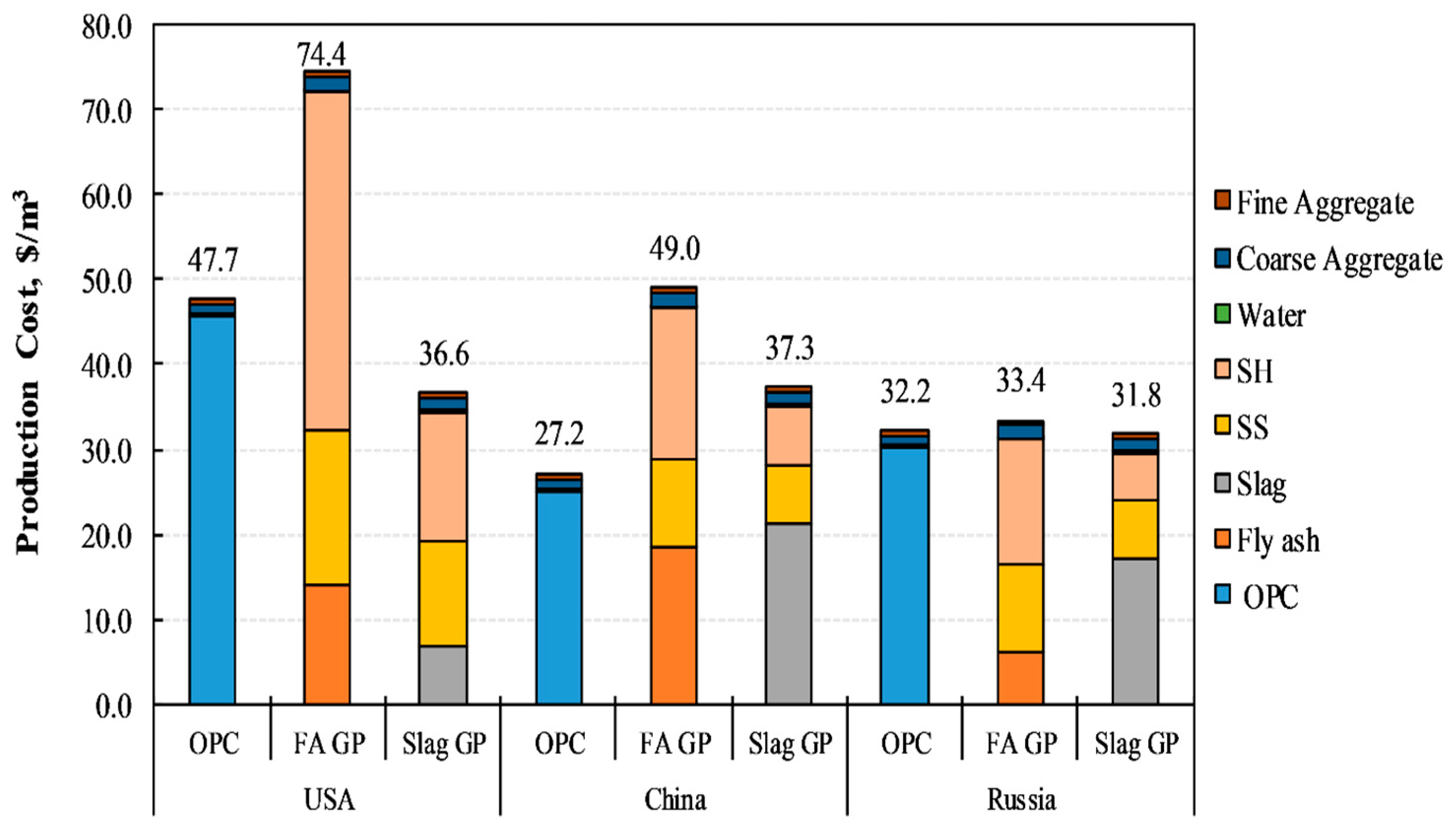

8. Cost and Sustainability Analysis of GPC

8.1. Regional Variation in Production Cost of GPC and OPC Concrete

8.2. Case Studies Sustainability Analysis

9. Conclusions and Future Research

9.1. Conclusions

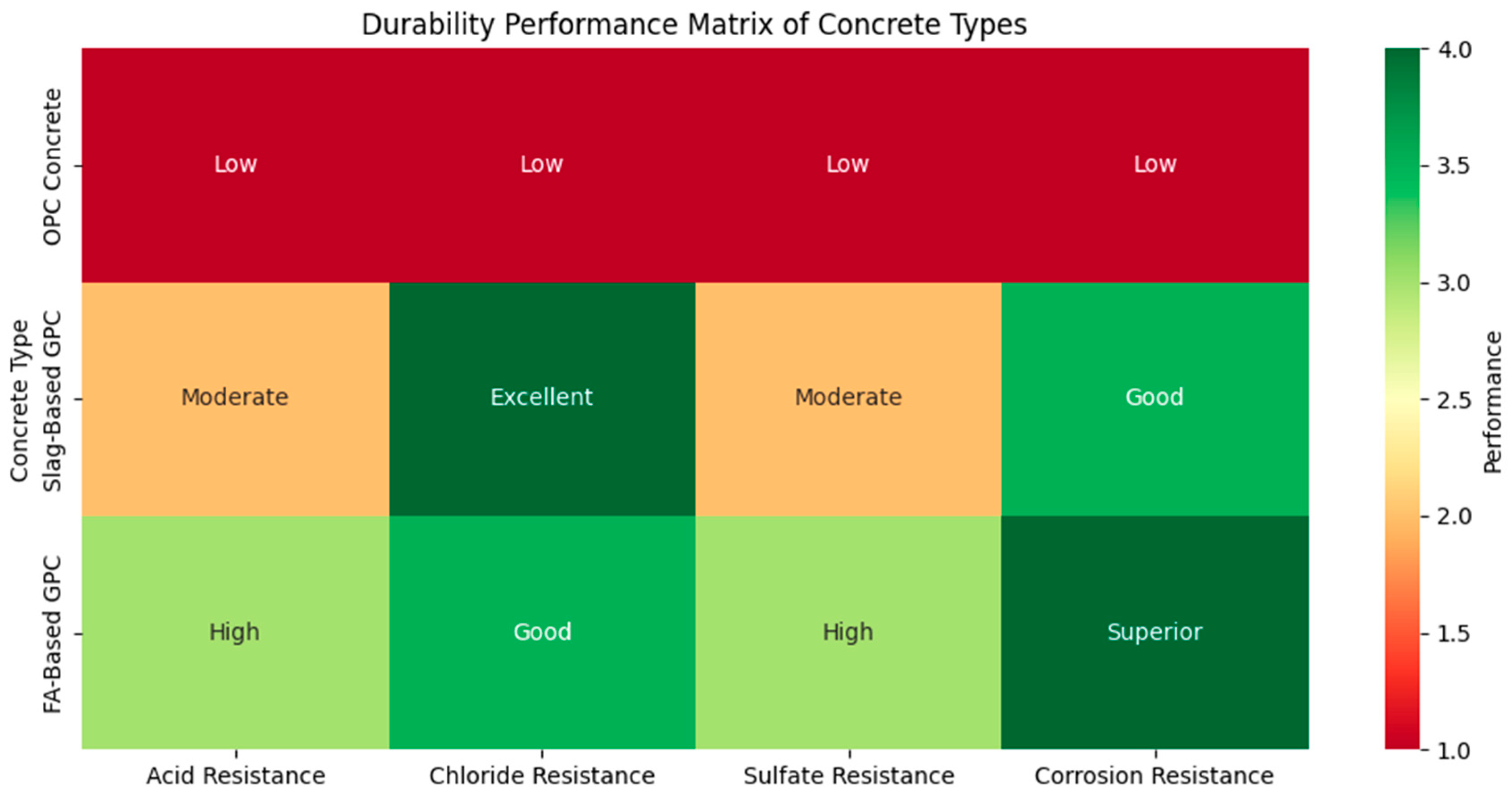

- GPC is synthesized by activating aluminosilicate precursors to produce N-A-S-H and C-A-S-H gels, which govern strength and durability. Low-Ca precursors such as FA predominantly form N-A-S-H, while high-Ca precursors like slag promote C-A-S-H gel formation, resulting in a denser microstructure and higher strength. However, this can also increase the risk of cracking due to the rapid geopolymerization process.

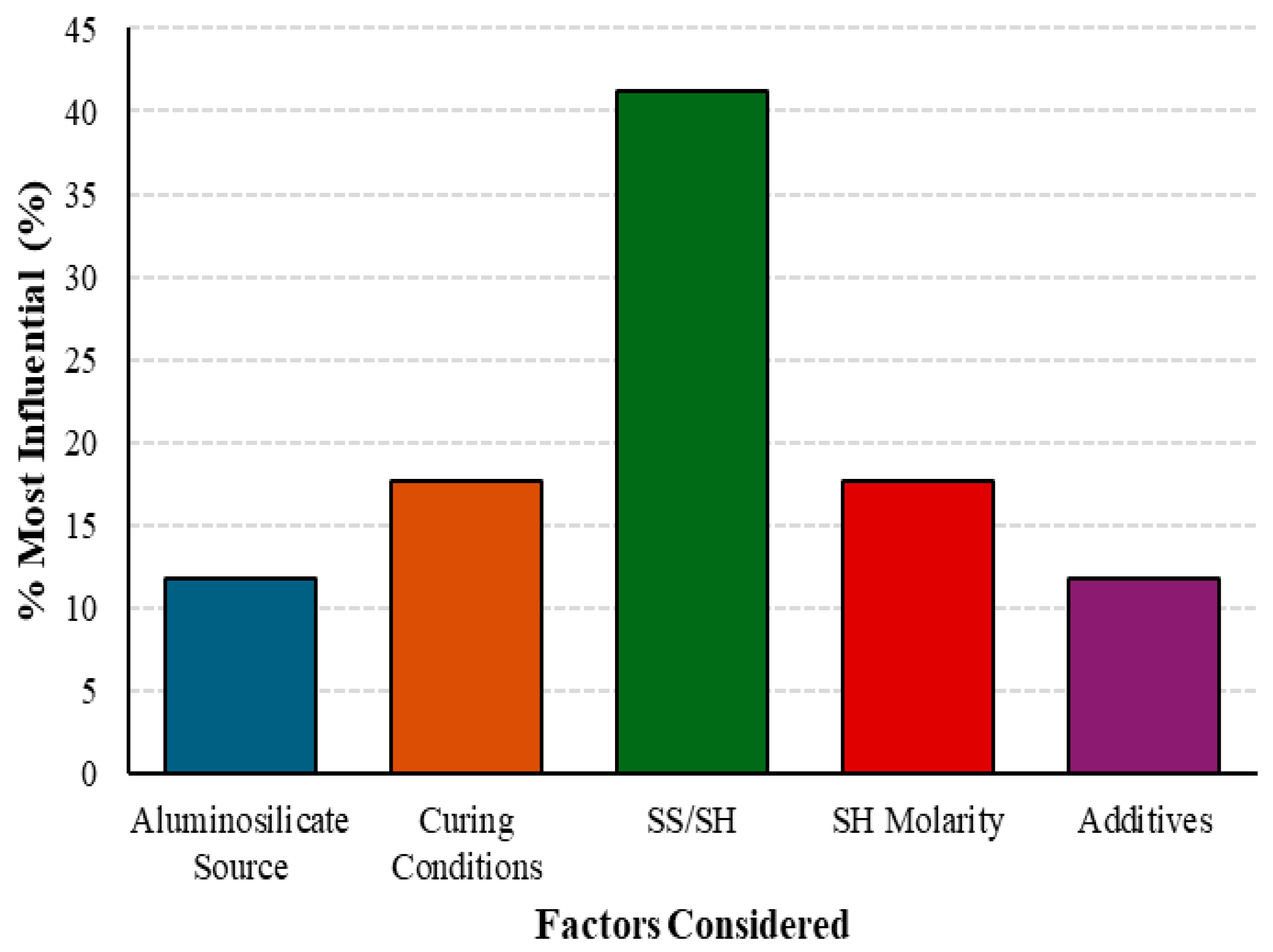

- Achieving optimal physical properties for net-zero GPC requires careful mix design, with particular attention to the SS/SH ratio. Characterization studies confirm that FA-based GPC primarily forms N-A-S-H gels, while slag-based GPC produces C-A-S-H phases, impacting strength and durability. These differences influence the reaction kinetics, gel structure, and thermal stability of the resulting matrix.

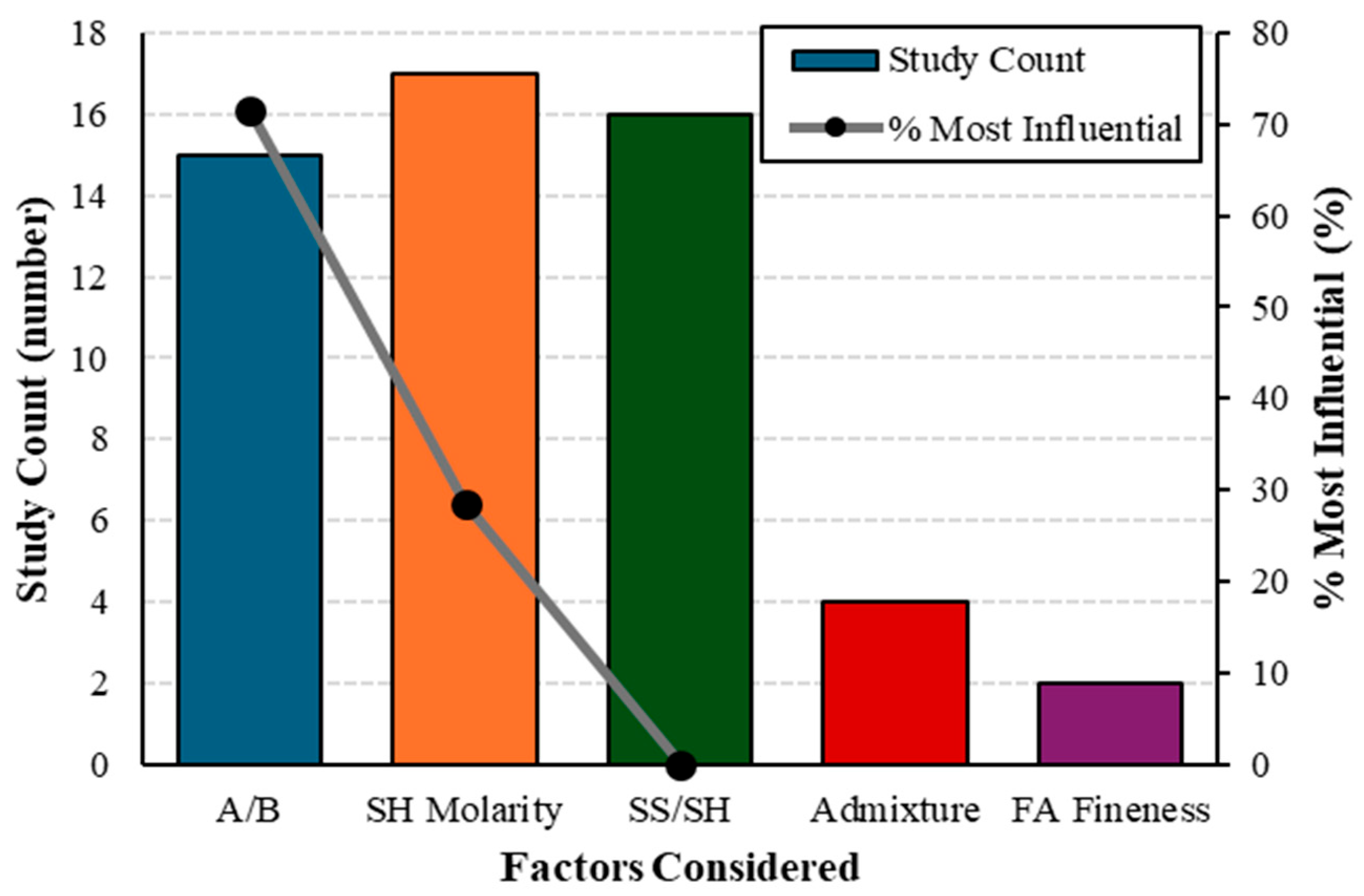

- The workability and mechanical properties of GPC, including compressive strength, tensile strength, and MOE, are significantly influenced by the A/B ratio. While high-Ca precursors improve mechanical strength due to the denser nature of C-A-S-H gels, they also accelerate setting time, reducing workability. Blending high- and low-Ca precursors and the use of admixtures can enhance workability without compromising strength, making GPC suitable for both precast and in situ applications.

- GPC exhibits superior resistance to acids, chlorides, sulfates, and corrosion compared to OPC concrete, owing to its aluminosilicate-based matrix that limits the formation of expansive degradation products. The durability of GPC is closely tied to its microstructural composition, and blending high- and low-Ca precursors can enhance its performance in aggressive environments. This strategic approach not only improves long-term durability but also supports the goal of achieving net-zero carbon GPC.

- The analysis, while assessing global feasibility, identifies FA-based GPC as the most viable alternative to OPC concrete due to its abundant global supply and potential to mitigate environmental and human health risks. However, sustainability assessments indicate that slag-based GPC exhibits lower overall environmental impacts compared to FA-based GPC. Using slag reduces reliance on SS, further decreasing the energy demand for GPC production.

- The review indicates that, based on precursor availability, curing techniques, and exposure environment, mass-level production of geopolymer concrete is feasible. However, adoption should be gradual—aligned with project-specific needs and progressing toward performance-based applications. In the meantime, alternative precursor materials are needed to address shortages of conventional precursors, and parallel research on new activators should continue.

9.2. Future Research

- With the declining availability of conventional precursors like FA and slag, future research should focus on identifying and optimizing alternative SCMs to ensure long-term sustainability. Potential sources such as agricultural residues, waste glass, and industrial byproducts offer promising low-carbon alternatives due to their abundance and reactivity. Investigating their geopolymerization kinetics, compatibility with different activators, and long-term performance is critical for developing sustainable, widely available, and cost-effective GPC binders that support carbon neutrality in construction.

- Optimizing GPC mix design through precise control of A/B and SS/SH ratios for given precursors is crucial to achieving net-zero carbon goals while ensuring high-performance standards. Future studies should focus on a systematic approach that tailors A/B and SS/SH ratios based on the specific precursors used to enhance workability, strength, and durability.

- While GPC is a more sustainable alternative to OPC, its feasibility for large-scale OPC replacement remains limited in many regions worldwide. Thus, future research should focus on minimizing the use of SH and SS in GPC activators due to their high cost and limited sustainability. The development and use of waste-based solid activators in one-part (“just add water”) GPC represents a promising alternative, as it can reduce embodied carbon, simplify handling, and enhance practical applicability for large-scale construction.

- Future research should explore emerging innovations such as CO2 curing and AI-driven mix design. CO2 curing has shown potential to enhance early-age strength, densify the GPC matrix, and reduce overall carbon emissions by promoting controlled carbonation. Similarly, artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques can be leveraged to optimize mix design by predicting the performance of GPC based on input variables such as precursor type, activator ratio, and curing conditions. These tools can minimize experimental trial-and-error and accelerate the development of high-performance, net-zero GPC systems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OPC | Ordinary Portland cement |

| GPC | Geopolymer concrete |

| SCM | Supplementary cementitious material |

| FA | Fly ash |

| BMT | Billion metric tons |

| CAC | Calcium aluminate cements |

| CSA | Calcium sulfoaluminate cements |

| MK | Metakaolin |

| BWWA | Brisbane West Well Camp Airport |

| XRF | X-ray fluorescence |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analysis |

| EDS | Energy-dispersive spectroscopy |

| LOI | Loss on Ignition |

| A/B | Activators to binder ratio |

| SH | Sodium hydroxide |

| SS | Sodium silicate |

| N-A-S-H | sodium-aluminate-silicate-hydrate |

| C-A-S-H | calcium-aluminate-silicate-hydrate |

| C-S-H | Calcium-silicate-hydrate |

| MoE | modulus of elasticity |

| RCPT | Rapid Chloride Permeability Test |

Appendix A

| Reference | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | MgO | CaO | K2O | Na2O | SO3 | TiO2 | P2O5 | LOI | PO |

| [75] | 55.60 | 29.80 | 5.91 | 1.08 | 1.59 | 1.94 | 0.23 | 0.45 | 1.63 | - | 0.47 | 91.31 |

| [76] | 52.06 | 20.54 | 5.50 | 3.29 | 14.07 | 0.69 | 0.57 | 0.57 | - | - | 0.10 | 78.10 |

| [77] | 53.70 | 28.10 | 6.99 | 1.59 | 4.32 | 1.89 | 0.87 | - | - | - | - | 88.79 |

| [78] | 57.90 | 31.11 | 5.07 | 0.97 | 1.29 | 1.00 | 0.09 | 0.05 | - | - | 0.04 | 94.08 |

| [79] | 48.40 | 39.60 | 12.10 | 1.30 | 2.70 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.30 | - | 1.70 | 100.10 | |

| [80] | 37.72 | 24.15 | 8.41 | 3.65 | 2.73 | 4.57 | - | 1.37 | 1.25 | 1.01 | - | 70.28 |

| [81] | 61.85 | 27.36 | 5.18 | 1.00 | 1.47 | 0.63 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 1.84 | 0.54 | 1.00 | 94.39 |

| [82] | 52.79 | 20.95 | 7.76 | 3.42 | 6.95 | 0.51 | 0.09 | - | 0.85 | - | - | 81.50 |

| [83] | 52.50 | 22.82 | 5.34 | 2.56 | 7.16 | 0.99 | 0.48 | 0.20 | - | - | 3.35 | 80.66 |

| [84] | 43.73 | 20.18 | 12.37 | 3.75 | 11.14 | 1.96 | 0.93 | 1.45 | - | - | - | 76.28 |

| [85] | 52.50 | 30.20 | 2.94 | 1.23 | 0.82 | 2.08 | - | - | 1.03 | - | 7.12 | 85.64 |

| [86] | 50.70 | 28.80 | 8.80 | 1.39 | 2.38 | 2.40 | 0.84 | 0.30 | - | - | 3.79 | 88.30 |

| [87] | 53.70 | 33.20 | 3.60 | 0.50 | 3.00 | 0.80 | - | 0.60 | 1.60 | 0.40 | 2.60 | 90.50 |

| [88] | 48.90 | 19.63 | 11.56 | 4.31 | 6.06 | 2.06 | 0.73 | 1.65 | - | - | 2.32 | 80.09 |

| [89] | 52.11 | 23.59 | 7.39 | 0.78 | 2.61 | 0.80 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.88 | 1.31 | - | 83.09 |

| [90] | 63.32 | 26.76 | 5.55 | 0.29 | 2.49 | 0.0002 | 0.0004 | 0.36 | - | - | 0.97 | 95.63 |

| [91] | 54.00 | 19.60 | 6.90 | 6.90 | 7.90 | 2.20 | - | - | 0.88 | 0.34 | 1.87 | 80.5 |

| [99] | 53.70 | 32.90 | 5.50 | 0.92 | 1.84 | 1.76 | 0.37 | 0.46 | 2.10 | 0.15 | - | 92.1 |

| [92] | 52.83 | 21.50 | 10.49 | 0.89 | 6.44 | 1.76 | 0.82 | - | 1.60 | 1.75 | 1.50 | 84.82 |

| [93] | 58.23 | 25.08 | 4.56 | 1.21 | 2.87 | 0.87 | 0.41 | 1.16 | 0.83 | 0.20 | 1.59 | 87.87 |

| [94] | 60.48 | 28.15 | 4.52 | 0.47 | 1.71 | 1.41 | 0.14 | - | - | - | 1.59 | 93.15 |

| [95] | 55.90 | 28.10 | 6.97 | 3.84 | 1.55 | - | - | 2.21 | - | 1.20 | 90.97 | |

| [96] | 44.83 | 29.23 | 4.66 | 1.62 | 4.47 | 0.68 | 1.32 | 0.62 | - | - | - | 78.72 |

| [97] | 49.10 | 34.80 | 4.50 | 0.40 | 4.90 | 1.30 | 0.40 | - | - | - | 2.30 | 88.4 |

| [98] | 55.00 | 26.00 | 10.17 | 0.80 | 2.09 | 1.65 | 0.40 | - | - | - | 3.89 | 91.17 |

| PO—Pozzolanic oxide. | ||||||||||||

References

- Gagg, C.R. Cement and concrete as an engineering material: An historic appraisal and case study analysis. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2014, 40, 114–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandanayake, M.; Bouras, Y.; Haigh, R.; Vrcelj, Z. Current sustainable trends of using waste materials in concrete—A decade review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.B.; Liang, J.F.; Li, W. Compression stress-strain curve of lithium slag recycled fine aggregate concrete. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0302176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, T.O.; Harun, M.Z.B.; Liu, J.; Fanijo, E.O. Effect of Oil Palm Broom Fiber on the Mechanical Properties of Rice Husk Ash–Blended Concrete. Recent Prog. Mater. 2025, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.A.; Horvath, A.; Monteiro, P.J.M. Impacts of booming concrete production on water resources worldwide. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanijo, E.; Babafemi, A.J.; Arowojolu, O. Performance of laterized concrete made with palm kernel shell as replacement for coarse aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 250, 118829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maywald, C.; Riesser, F. Sustainability—The Art of Modern Architecture. Procedia Eng. 2016, 155, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, F.; Jin, X.; Javed, M.F.; Akbar, A.; Shah, M.I.; Aslam, F.; Alyousef, R. Geopolymer concrete as sustainable material: A state of the art review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 306, 124762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA. 2019 Direct Carbon Intensities Quartile Metric Ton CO2/Metric Ton of Clinker Metric Ton CO2/Metric Ton of Cement Carbon Intensity. 2021. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text- (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- Ige, O.E.; Von Kallon, D.V.; Desai, D. Carbon emissions mitigation methods for cement industry using a systems dynamics model. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2024, 26, 579–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bărbulescu, A.; Hosen, K. Cement Industry Pollution and Its Impact on the Environment and Population Health: A Review. Toxics 2025, 13, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, N.; Muthusamy, K.; Embong, R.; Kusbiantoro, A.; Hashim, M.H. Environmental impact of cement production and Solutions: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 48, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtyar, B.; Kacemi, T.; Nawaz, A. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy A Review on Carbon Emissions in Malaysian Cement Industry. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2017, 7, 282–286. [Google Scholar]

- Ghafoor, M.T.; Khan, Q.S.; Qazi, A.U.; Sheikh, M.N.; Hadi, M.N.S. Influence of alkaline activators on the mechanical properties of fly ash based geopolymer concrete cured at ambient temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 273, 121752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhimova, N. Recent Advances in Alternative Cementitious Materials for Nuclear Waste Immobilization: A Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobili, A.; Telesca, A.; Marroccoli, M.; Tittarelli, F. Calcium sulfoaluminate and alkali-activated fly ash cements as alternative to Portland cement: Study on chemical, physical-mechanical, and durability properties of mortars with the same strength class. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 246, 118436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfimova, N.; Levickaya, K.; Elistratkin, M.; Buhtiyarov, I. Supersulfated Cements: A Review Analysis of the Features of Properties Raw Materials Production and Application Prospects. Bull. Belgorod State Technol. Univ. Named After. V. G. Shukhov 2024, 9, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mose, M.P.E.; Perumal, D.B. Latest Advances in Alternative Cementations Binders than Portland cement. IOSR J. Mech. Civ. Eng. 2016, 13, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, S.A.; de Gutierrez, R.M.; Rodríguez, E.D. Alkali-activated materials: Cementing a sustainable future. Ing. Y Compet. 2013, 15, 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, M.M.A.; Hussin, K.; Bnhussain, M.; Ismail, K.N.; Ibrahim, W.M.W. Mechanism and Chemical Reaction of Fly Ash Geopolymer Cement—A Review. Asian J. Sci. Res. 2011, 1, 247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Davidovits, J. Geopolymer Chemistry and Applications, 5th ed.; Geopolymer Institute: Saint-Quentin, France, 2008; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265076752 (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- Kumar, A.D.S.; Singh, D.; Reddy, V.S.; Reddy, K.J. Geo-polymerization mechanism and factors affecting it in Metakaolin-slag-fly ash blended concrete. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences, Chongqing, China, 20–22 November 2020; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, F.; Liu, Q. Geopolymerization and its potential application in mine tailings consolidation: A review. Miner. Process. Extr. Met. Rev. 2015, 36, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.Y.; Chen, L.; Komarneni, S.; Zhou, C.H.; Tong, D.S.; Yang, H.M.; Yu, W.H.; Wang, H. Fly ash-based geopolymer: Clean production, properties and applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 125, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Gao, Z.; Wang, J.; Guo, J.; Hu, S.; Ling, Y. Properties of fresh and hardened fly ash/slag based geopolymer concrete: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 270, 122389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puertas, F.; González-Fonteboa, B.; González-Taboada, I.; Alonso, M.M.; Torres-Carrasco, M.; Rojo, G.; Martínez-Abella, F. Alkali-activated slag concrete: Fresh and hardened behaviour. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 85, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Chen, W.; Wang, J.; Fang, C.; Zhang, B.; Liu, F. Coupling effects of recycled aggregate and GGBS/metakaolin on physicochemical properties of geopolymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 226, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouhet, R.; Cyr, M. Formulation and performance of flash metakaolin geopolymer concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 120, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaty, F.; Khoury, H.; Wastiels, J.; Rahier, H. Characterization of alkali activated kaolinitic clay. Appl. Clay Sci. 2013, 75, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Provis, J.L.; Reid, A.; Wang, H. Geopolymer foam concrete: An emerging material for sustainable construction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 56, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.B.; Middendorf, B. Geopolymers as an alternative to Portland cement: An overview. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 237, 117455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deventer, J.S.J.; Provis, J.L.; Duxson, P. Technical and commercial progress in the adoption of geopolymer cement. Miner. Eng. 2012, 29, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parathi, S.; Nagarajan, P.; Pallikkara, S.A. Ecofriendly geopolymer concrete: A comprehensive review. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2021, 23, 1701–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhou, C.; Ahmad, W.; Usanova, K.I.; Karelina, M.; Mohamed, A.M.; Khallaf, R. Fly Ash Application as Supplementary Cementitious Material: A Review. Materials 2022, 15, 2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, A.; Manzoor, S.O.; Youssouf, M.; Malik, Z.A.; Khawaja, K.S. Fly Ash: Production and Utilization in India—An Overview. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2020, 11, 911–921. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi, A.; Jain, M.K. Fly ash-waste management and overview: A Review. Recent Res. Sci. Technol. 2014, 6, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, D.L. Decrease in Fly Ash Spurring Innovation Within Construction Materials Industry. Nat. Gas Electr. 2019, 35, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranya, P.; Nagarajan, P.; Shashikala, A.P. Eco-friendly GGBS Concrete: A State-of-The-Art Review. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Hyderabad, India, 1–2 June 2017; Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desta, E.; Jun, Z. A Review on Ground Granulated Blast Slag GGBS in Concrete. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Advances in Civil and Structural Engineering, CSE, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 4 February 2018; pp. 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Suresh, D.; Nagaraju, K. Ground Granulated Blast Slag (GGBS) In Concrete-A Review. IOSR J. Mech. Civ. Eng. 2015, 12, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hoenig, V.; Schall, A.; Sultanov, N.; Papkalla, S.; Ruppert, J. Status and Prospects of Alternative Raw Materials in the European Cement Sector; The European Cement Research Academy (ECRA): Düsseldorf, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, S.V.; Karikatti, V.B.; Chitawadagi, M. Granulated Blast-Furnace Slag (GGBS) based Geopolymer concrete—Review Concrete—Review. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. 2018, 5, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Arif, M.; Shariq, M. Use of geopolymer concrete for a cleaner and sustainable environment—A review of mechanical properties and microstructure. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 223, 704–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakera, A.T.; Alexander, M.G. Use of metakaolin as a supplementary cementitious material in concrete, with a focus on durability properties. RILEM Tech. Lett. 2019, 4, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, M.; Rożek, P. The effect of calcination temperature on metakaolin structure for the synthesis of zeolites. Clay Miner. 2018, 53, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, A.M. Metakaolin as cementitious material: History, scours, production and composition-A comprehensive overview. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 41, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuenzel, C.; Neville, T.P.; Donatello, S.; Vandeperre, L.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Cheeseman, C.R. Influence of metakaolin characteristics on the mechanical properties of geopolymers. Appl. Clay Sci. 2013, 83, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, F.U.A. Review of mechanical properties of short fibre reinforced geopolymer composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 43, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Joshi, D.; Mangla, D.; Savvidis, I. Recent development in geopolymer concrete: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, G.; Alengaram, U.J.; Ibrahim, S.; Ibrahim, M.S.I. Effect of Fly Ash characteristics, sodium-based alkaline activators, and process variables on the compressive strength of siliceous Fly Ash geopolymers with microstructural properties: A comprehensive review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 437, 136808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Alouani, M.; Saufi, H.; Aouan, B.; Bassam, R.; Alehyen, S.; Rachdi, Y.; El Hadki, H.; El Hadki, A.; Mabrouki, J.; Belaaouad, S.; et al. A comprehensive review of synthesis, characterization, and applications of aluminosilicate materials-based geopolymers. Environ. Adv. 2024, 16, 100524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B. Durability of low-carbon geopolymer concrete: A critical review. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2024, 40, e00882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magotra, S.; Jee, A.A. A Review on durability and microstructure of Fly-Ash based geopolymer concrete (FA-GPC). Mater. Today Proc. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLellan, B.C.; Williams, R.P.; Lay, J.; Van Riessen, A.; Corder, G.D. Costs and carbon emissions for geopolymer pastes in comparison to ordinary portland cement. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1080–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajimohammadi, A.; Provis, J.L.; Van Deventer, J.S.J. Effect of alumina release rate on the mechanism of geopolymer gel formation. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 5199–5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.K.; Awang, A.Z.; Omar, W. Structural and material performance of geopolymer concrete: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 186, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabroum, S.; Moukannaa, S.; El Machi, A.; Taha, Y.; Benzaazoua, M.; Hakkou, R. Mine wastes based geopolymers: A critical review. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2020, 1, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burciaga-Díaz, O.; Díaz-Guillén, M.R.; Fuentes, A.F.; Escalante-Garcia, J.I. Mortars of alkali-activated blast furnace slag with high aggregate: Binder ratios. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 44, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouan, B.; Alehyen, S.; Fadil, M.; El Alouani, M.; Saufi, H.; Taibi, M. Characteristics, microstructures, and optimization of the geopolymer paste based on three aluminosilicate materials using a mixture design methodology. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 384, 131475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, G.S.; Lee, Y.B.; Koh, K.T.; Chung, Y.S. The mechanical properties of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete with alkaline activators. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 47, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidovits, J. Properties of geopolymer cements. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Alkaline Cements and Concretes, Kiev, Ukraine, 11–14 October 1994; pp. 131–149. [Google Scholar]

- Davidovits, J. Geopolymer chemistry and sustainable development. The poly (sialate) terminology: A very useful and simple model. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Geopolymer Cements and Concrete for the Promotion and Understanding of Green-Chemistry, Perth, Australia, 28–29 September 2005; pp. 2181–2278. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, M.; Mahmood, A.H.; Bahraq, A.A. History, recent progress, and future challenges of alkali-activated binders—An overview. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 426, 136141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, A.; Degirmenci, F.N.; Aygörmez, Y. Effect of initial curing conditions on the durability performance of low-calcium fly ash-based geopolymer mortars. Boletín Soc. Española Cerámica Vidr. 2024, 63, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmin, S.N.; Welling, J.; Krause, A.; Shalbafan, A. Investigating the Possibility of Geopolymer to Produce Inorganic-Bonded Wood Composites for Multifunctional Construction Material-A Review. Bioresources 2014, 9, 7941–7950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdila, S.R.; Abdullah, M.M.A.B.; Ahmad, R.; Nergis, D.D.B.; Rahim, S.Z.A.; Omar, M.F.; Sandu, A.V.; Vizureanu, P. Syafwandi, Potential of Soil Stabilization Using Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBFS) and Fly Ash via Geopolymerization Method: A Review. Materials 2022, 15, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; White, C.E. Modeling the Formation of Alkali Aluminosilicate Gels at the Mesoscale Using Coarse-Grained Monte Carlo. Langmuir 2016, 32, 11580–11590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Deskins, N.A.; Zhang, G.; Cygan, R.T.; Tao, M. Modeling the Polymerization Process for Geopolymer Synthesis through Reactive Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 6760–6773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleem, A.; Arumairaj, P.D.; Aleem, M.I.A. Pollution free geopolymer concrete with M-Sand. Poll Res. 2013, 32, 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Aleem, M.I.A.; Arumairaj, P.D. Geopolymer Concrete—A Review. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2012, 1, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo, A.; Fernández-Jiménez, A. Alkaline activation, procedure for transforming fly ash into new materials. Part I: Applications. In Proceedings of the World of Coal Ash (WOCA) Conference, Denver, CO, USA, 9–12 May 2011; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz, M.; Heitor, A.; Sivakumar, M. Geopolymers in construction—Recent developments. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 260, 120472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glukhovsky, V.D.; Pashkov, I.A.; Yavorsky, G.A. New building material, in Russian, Bulletin of Technical Information. Gosstrojizdat Kiev 1967, 245, 627. [Google Scholar]

- Amran, M.; Al-Fakih, A.; Chu, S.H.; Fediuk, R.; Haruna, S.; Azevedo, A.; Vatin, N. Long-term durability properties of geopolymer concrete: An in-depth review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2021, 15, e00661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Rout, P.K. Synthesis, Characterization and Properties of Fly Ash Based Geopolymer Materials. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2021, 30, 3213–3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Liu, Z.; Xu, G.; Peng, H.; Cai, C.S. Mechanical and thermal properties of fly ash based geopolymers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 160, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lirer, S.; Liguori, B.; Capasso, I.; Flora, A.; Caputo, D. Mechanical and chemical properties of composite materials made of dredged sediments in a fly-ash based geopolymer. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 191, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shehab, H.K.; Eisa, A.S.; Wahba, A.M. Mechanical properties of fly ash based geopolymer concrete with full and partial cement replacement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 126, 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, S.; Duan, W.H.; Pan, Z.; Hunter, E.; Korayem, A.H.; Zhao, X.L.; Collins, F.; Sanjayan, J.G. The properties of fly ash based geopolymer mortars made with dune sand. Mater. Des. 2016, 92, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerzouri, M.; Bouchenafa, O.; Hamzaoui, R.; Ziyani, L.; Alehyen, S. Physico-chemical and mechanical properties of fly ash based-geopolymer pastes produced from pre-geopolymer powders obtained by mechanosynthesis. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 288, 123135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, B.H.; Kadam, K.N. Properties of Fly Ash based Geopolymer Mortar. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2015, 4, 971–974. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Ren, Y. Effects of Si/Al ratio on the efflorescence and properties of fly ash based geopolymer. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosyidi, S.A.P.; Rahmad, S.; Yusoff, N.I.M.; Shahrir, A.H.; Ibrahim, A.N.H.; Ismail, N.F.N.; Badri, K.H. Investigation of the chemical, strength, adhesion and morphological properties of fly ash based geopolymer-modified bitumen. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 255, 119364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, R.M.; Man, Z.; Azizli, K.A. Concentration of NaOH and the Effect on the Properties of Fly Ash Based Geopolymer. Procedia Eng. 2016, 148, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Alouani, M.; Alehyen, S.; El Achouri, M.; Hajjaji, A.; Ennawaoui, C.; Taibi, M. Influence of the Nature and Rate of Alkaline Activator on the Physicochemical Properties of Fly Ash-Based Geopolymers. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 8880906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, F.N.; Durgaprasad, J.; Singh, N.B. Effect of silica fume on the mechanical properties of fly ash based-geopolymer concrete. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 3000–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Han, M. The influence of α-Al2O3 addition on microstructure, mechanical and formaldehyde adsorption properties of fly ash-based geopolymer products. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 193, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Görhan, G.; Kürklü, G. The influence of the NaOH solution on the properties of the fly ash-based geopolymer mortar cured at different temperatures. Compos. B Eng. 2014, 58, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zain, H.; Abdullah, M.M.A.B.; Hussin, K.; Ariffin, N.; Bayuaji, R. Review on Various Types of Geopolymer Materials with the Environmental Impact Assessment. In Proceedings of the MATEC Web of Conferences, Sibiu, Romania, 7–9 June 2017; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagajothi, S.; Elavenil, S.; Angalaeswari, S.; Natrayan, L.; Mammo, W.D. Durability Studies on Fly Ash Based Geopolymer Concrete Incorporated with Slag and Alkali Solutions. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 2022, 7196446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihan, M.A.M.; Alahmari, T.S.; Onchiri, R.O.; Gathimba, N.; Sabuni, B. Impact of Alkaline Concentration on the Mechanical Properties of Geopolymer Concrete Made up of Fly Ash and Sugarcane Bagasse Ash. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, R.; Choudhary, K.; Srivastava, A.; Sangwan, K.S.; Singh, M. Environmental impact assessment of fly ash and silica fume based geopolymer concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellum, R.R.; Venkatesh, C.; Madduru, S.R.C. Influence of red mud on performance enhancement of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2021, 6, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, S. Development of paving blocks from synergistic use of red mud and fly ash using geopolymerization. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 38, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.; Hussin, K.; Abdullah, M.M.A.B.; Yahya, Z.; Sochacki, W.; Razak, R.A.; Błoch, K.; Fansuri, H. The effects of various concentrations of naoh on the inter-particle gelation of a fly ash geopolymer aggregate. Materials 2021, 14, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulandari, K.D.; Ekaputri, J.J.; Triwulan; Kurniawan, S.B.; Primaningtyas, W.E.; Abdullah, S.R.S.; Ismail, I.; Imron, M.F. Effect of microbes addition on the properties and surface morphology of fly ash-based geopolymer paste. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 33, 101596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liang, J.; Ye, G. Effect of the sodium silicate modulus and slag content on fresh and hardened properties of alkali-activated fly ash/slag. Minerals 2020, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivasakthi, M.; Jeyalakshmi, R.; Rajamane, N.P. Fly ash geopolymer mortar: Impact of the substitution of river sand by copper slag as a fine aggregate on its thermal resistance properties. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błaszczyński, T.Z.; Król, M.R. Geopolymers in Construction/Zastosowanie Geopolimerów W Budownictwie. Civ. Environ. Eng. Rep. 2023, 16, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fernández-Jiménez, A.; Palomo, A.; Sobrados, I.; Sanz, J. The role played by the reactive alumina content in the alkaline activation of fly ashes. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2006, 91, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soutsos, M.; Boyle, A.P.; Vinai, R.; Hadjierakleous, A.; Barnett, S.J. Factors influencing the compressive strength of fly ash based geopolymers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 110, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, E.I.; Allouche, E.N.; Eklund, S. Factors affecting the suitability of fly ash as source material for geopolymers. Fuel 2010, 89, 992–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alehyen, S.; Achouri, M.E.L.; Taibi, M. Characterization, microstructure, and properties of fly ash-based geopolymer. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2017, 8, 1783–1796. [Google Scholar]

- Yazdi, M.A.; Liebscher, M.; Hempel, S.; Yang, J.; Mechtcherine, V. Correlation of microstructural and mechanical properties of geopolymers produced from fly ash and slag at room temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 191, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagalia, G.; Park, Y.; Abolmaali, A.; Aswath, P. Compressive Strength and Microstructural Properties of Fly Ash–Based Geopolymer Concrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2016, 28, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohra, V.K.J.; Nerella, R.; Madduru, S.R.C.; Rohith, P. Microstructural characterization of fly ash based geopolymer. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 27, 1625–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmad, J.; BiBi, A.; Al-Ghouti, M.A. Application of TiO2-loaded fly ash-based geopolymer in adsorption of methylene blue from water: Waste-to-value approach. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 25, 101138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Gong, W.; Syltebo, L.; Izzo, K.; Lutze, W.; Pegg, I.L. Effect of blast furnace slag grades on fly ash based geopolymer waste forms. Fuel 2014, 133, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, I.H.; Abdullah, M.M.A.B.; Salleh, M.A.A.M.; Azimi, E.A.; Chaiprapa, J.; Sandu, A.V. Strength development of solely ground granulated blast furnace slag geopolymers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 250, 118720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Mucsi, G.; Kristály, F.; Pekker, P. Mechanical activation of fly ash and its influence on micro and nano-structural behaviour of resulting geopolymers. Adv. Powder Technol. 2017, 28, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rożek, P.; Król, M.; Mozgawa, W. Spectroscopic studies of fly ash-based geopolymers. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2018, 198, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.K. Geopolymerization behavior of ferrochrome slag and fly ash blends. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 181, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfoud, E.; Maherzi, W.; Ndiaye, K.; Benzerzour, M.; Aggoun, S.; Abriak, N.E. Mechanical and microstructural properties of just add water geopolymer cement comprised of Thermo-Mechanicalsynthesis Sediments-Fly ash mix. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 400, 132626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.K.; Maitra, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Kumar, S. Microstructural and morphological evolution of fly ash based geopolymers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 111, 758–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhar, S.; Chaudhary, S.; Luhar, I. Thermal resistance of fly ash based rubberized geopolymer concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 19, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas, C.A.; Arredondo-Rea, S.P.; Gómez-Soberón, J.M.; Almaral-Sánchez, J.L.; Rosas-Casarez, C.A.; Arredondo-Rea, S.P.; Gómez-Soberón, J.M.; Alamaral-Sánchez, J.L.; Corral-Higuera, R.; Chinchillas-Chinchillas, M.J.; et al. Experimental Study of XRD, FTIR and TGA Techniques in Geopolymeric Materials, 2014. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274079395 (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Li, S.; Huang, X.; Muhammad, F.; Yu, L.; Xia, M.; Zhao, J.; Jiao, B.; Shiau, Y.; Li, D. Waste solidification/stabilization of lead-zinc slag by utilizing fly ash based geopolymers. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 32956–32965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öz, H.Ö.; Yücel, H.E.; Güneş, M.; Köker, T.Ş. Fly-ash-based geopolymer composites incorporating cold-bonded lightweight fly ash aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 272, 121963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, L.R.; Paiva, M.D.D.M.; Fairbairn, E.D.M.R.; Filho, R.D.T. Thermal, mechanical and microstructural analysis of metakaolin based geopolymers. Mater. Res. 2019, 22, e20180716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catauro, M.; Tranquillo, E.; Barrino, F.; Dal Poggetto, G.; Blanco, I.; Cicala, G.; Ognibene, G.; Recca, G. Mechanical and thermal properties of fly ash-filled geopolymers. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2019, 138, 3267–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Yan, C.; Duan, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Qiu, X.; Li, D. A comparative study of high- and low-Al2O3 fly ash based-geopolymers: The role of mix proportion factors and curing temperature. Mater. Des. 2016, 95, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Tang, N.; Sun, Y.; Nie, N.; Zhang, R.; Wang, K. Adhesion performance and enhancement mechanism of FA/GGBFS based geopolymer modified bitumen and acidic aggregate. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Fan, X.; Gao, C. Strength, pore characteristics, and characterization of fly ash-slag-based geopolymer mortar modified with silica fume. Structures 2024, 69, 107525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.K.; Kumar, S. Evaluation of the suitability of ground granulated silico-manganese slag in Portland slag cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 125, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Yu, Q.L.; Brouwers, H.J.H. Reaction kinetics, gel character and strength of ambient temperature cured alkali activated slag-fly ash blends. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 80, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Lei, Z.; Gao, M.; Sun, J.; Tong, L.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y. Designing low-carbon fly ash based geopolymer with red mud and blast furnace slag wastes: Performance, microstructure and mechanism. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 354, 120362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; He, M.; Pan, Z. Inhibition of efflorescence for fly ash-slag-steel slag based geopolymer: Pore network optimization and free alkali stabilization. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 48538–48550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Bao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ping, Y. Sustainable enhancement of fly ash-based geopolymers: Impact of Alkali thermal activation and particle size on green production. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 191, 478–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Gao, P.; Xu, F.; Sun, T.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, J.; Peng, C.; Lin, J. Effect of fine aggregate particle characteristics on mechanical properties of fly ash-based geopolymer mortar. Minerals 2021, 11, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagajothi, S.; Elavenil, S. Effect of GGBS Addition on Reactivity and Microstructure Properties of Ambient Cured Fly Ash Based Geopolymer Concrete. Silicon 2021, 13, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Jia, Y. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer Cementitious Composites. Minerals 2022, 12, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Yu, J.; Ji, F.; Gu, L.; Chen, Y.; Shan, X. Mechanical Property and Microstructure of Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer Activated by Sodium Silicate. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2021, 25, 1765–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, S.N.A.; Shafiq, N.; Guillaumat, L.; Farhan, S.A.; Lohana, V.K. Fire-Exposed Fly-Ash-Based Geopolymer Concrete: Effects of Burning Temperature on Mechanical and Microstructural Properties. Materials 2022, 15, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hager, I.; Sitarz, M.; Mróz, K. Fly-ash based geopolymer mortar for high-temperature application—Effect of slag addition. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 316, 128168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellum, R.R.; Muniraj, K.; Madduru, S.R.C. Influence of slag on mechanical and durability properties of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete. J. Korean Ceram. Soc. 2020, 57, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, Q.M.; Ngo, P.M.; Nguyen, H.T. Characteristics of a fly ash-based geopolymer cured in microwave oven. Key Eng. Mater. 2020, 850, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuenzel, C.; Ranjbar, N. Dissolution mechanism of fly ash to quantify the reactive aluminosilicates in geopolymerisation. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 150, 104421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.K.; Kumar, S. Role of particle fineness on engineering properties and microstructure of fly ash derived geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 233, 117294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Pan, J.; Li, X.; Tan, J.; Li, J. Electrical resistivity of fly ash and metakaolin based geopolymers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 234, 117868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.M.A.B.; Hussin, K.; Binhussain, M.; Nizar, I.K.; Razak, R.A.; Zarina, Y. Microstructure study on optimization of high strength fly ash based geopolymer. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 476, 2173–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Li, H.H.; Wang, Y.C.; Xu, D.L. Geopolymer microstructure and hydration mechanism of alkali-activated fly ash-based geopolymer. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 374, 1481–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, R.; Pasla, D. Assessment of mechanical and durability properties of FA-GGBS based lightweight geopolymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 426, 135984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, X.; Cai, C.; Li, F.; Jin, H.; Zhang, S.; Sheng, N.; Wang, T.; Ngo, T. Microstructure, strength development mechanism and CO2 emission assessments of molybdenum tailings collaborative fly ash geopolymers. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, R.; Zhang, L. Utilization of chitosan biopolymer to enhance fly ash-based geopolymer. J. Mater. Sci. 2013, 48, 7986–7993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Azizli, K.; Sufian, S.; Man, Z.; Siyal, A.A.; Ullah, H. Determination of anisotropy and multimorphology in fly ash based geopolymers. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceeding, Tronoh, Malaysia, 10–12 December 2014; American Institute of Physics Inc.: College Park, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çeli, S.; Öztürk, Z.B.; Atabey, İ.İ. High-temperature resistance of ceramic sanitaryware waste and fly ash-based geopolymer and hybrid geopolymer mortars produced at ambient curing conditions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 446, 137990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellum, R.R.; Al Khazaleh, M.; Pilla, R.K.; Choudhary, S.; Venkatesh, C. Effect of slag on strength, durability and microstructural characteristics of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete. J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil. 2022, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, H.L.; Liu, J.; Doh, J.H.; Ong, D.E.L. Influence of Si/Al molar ratio and ca content on the performance of fly ash-based geopolymer incorporating waste glass and GGBFS. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Doh, J.H.; Ong, D.E.L.; Dinh, H.L.; Podolsky, Z.; Zi, G. Investigation on red mud and fly ash-based geopolymer: Quantification of reactive aluminosilicate and derivation of effective Si/Al molar ratio. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 71, 106559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.; Wang, K.; Li, W.; Shi, G.; Lu, P. Effect of slag on the mechanical properties and bond strength of fly ash-based engineered geopolymer composites. Compos. B Eng. 2019, 164, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Li, K.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Fan, J.; Zhu, J. Self-healing behaviour of fly ash/slag-based engineered geopolymer composites under external alkaline environments. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liu, L.; Yang, Z.; Li, S. Physical and mechanical properties and micro characteristics of fly ash-based geopolymer paste incorporated with waste Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GBFS) and functionalized Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs). J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 401, 123339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Wu, G.; Jiang, L.; Sun, D. Characterization of multi-scale porous structure of fly ash/phosphate geopolymer hollow sphere structures: From submillimeter to nano-scale. Micron 2014, 68, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, N.; Mehrali, M.; Mehrali, M.; Alengaram, U.J.; Jumaat, M.Z. Graphene nanoplatelet-fly ash based geopolymer composites. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 76, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Hao, H.; Lu, Y.; Li, S. Effects of Cl- erosion conditions on Cl- binding properties of fly-ash-slag-based geopolymer. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 67, 105907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivasakthi, M.; Jeyalakshmi, R.; Rajamane, N.P.; Jose, R. Thermal and structural micro analysis of micro silica blended fly ash based geopolymer composites. J. Non Cryst. Solids 2018, 499, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, N.; Mehrali, M.; Alengaram, U.J.; Metselaar, H.S.C.; Jumaat, M.Z. Compressive strength and microstructural analysis of fly ash/palm oil fuel ash based geopolymer mortar under elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 65, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosan, A.; Haque, S.; Shaikh, F. Compressive behaviour of sodium and potassium activators synthetized fly ash geopolymer at elevated temperatures: A comparative study. J. Build. Eng. 2016, 8, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; Zhang, Y.J.; Xu, D.L. Novel activator for synthesis of fly ash based geopolymer. Mater. Res. Innov. 2014, 18, S2238–S2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Sun, R.; Rui, Y. Effects of the n(H2O: Na2Oeq) ratio on the geopolymerization process and microstructures of fly ash-based geopolymers. J. Non Cryst. Solids 2019, 511, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomayri, T.; Shaikh, F.U.A.; Low, I.M. Mechanical and thermal properties of ambient cured cotton fabric-reinforced fly ash-based geopolymer composites. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 14019–14028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, P.; Mei, L. Using silica fume for improvement of fly ash/slag based geopolymer activated with calcium carbide residue and gypsum. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 275, 122171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, R.; Polaczyk, P.; Zhang, M.; Hu, W.; Bai, Y.; Huang, B. A comparative study on geopolymers synthesized by different classes of fly ash after exposure to elevated temperatures. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 270, 122500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, H.; Neithalath, N. Novel synthesis of lightweight geopolymer matrices from fly ash through carbonate-based activation. Mater. Today Commun. 2018, 17, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Li, H.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, H.; Basheer, P.A.M.; Bai, Y. Alkali-activated fly ash cured with pulsed microwave and thermal oven: A comparison of reaction products, microstructure and compressive strength. Cem. Concr. Res. 2023, 166, 107104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfoud, E.; Ndiaye, K.; Maherzi, W.; Aggoun, S.; Abriak, N.-E.; Benzerzour, M. Carbonation in just add water geopolymer based on fly ash and dredged sediments mix. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 452, 138959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öz, H.Ö.; Güneş, M.; Yücel, H.E. Rheological and microstructural properties of FA+GGBFS-based engineered geopolymer composites (EGCs) capable of comparing with M45-ECC as mechanical performance. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 65, 105792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Xiao, R.; Zhang, M.; Hu, W.; Bai, Y.; Huang, B. A laboratory investigation of steel to fly ash-based geopolymer paste bonding behavior after exposure to elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 254, 119267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickard, W.D.A.; Van Riessen, A.; Walls, P. Thermal character of geopolymers synthesized from class Fly ash containing high concentrations of iron and α-quartz. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2010, 7, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, A.E.; Shashikala, A.P. Studies on the microstructure and durability characteristics of ambient cured FA-GGBS based geopolymer mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 347, 128538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öz, H.Ö.; Doğan-Sağlamtimur, N.; Bilgil, A.; Tamer, A.; Günaydin, K. Process development of fly ash-based geopolymer mortars in view of the mechanical characteristics. Materials 2021, 14, 2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, I.H.; Al Bakri Abdullah, M.M.; Heah, C.Y.; Liew, Y.M. Behaviour changes of ground granulated blast furnace slag geopolymers at high temperature. Adv. Cem. Res. 2020, 32, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, M.E.; Abo-El-Enein, S.A.; Sayed, A.Z.; EL-Sokkary, T.M.; Hammad, H.A. Incorporation of cement bypass flue dust in fly ash and blast furnace slag-based geopolymer. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2018, 8, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, K.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Shumuye, E.D.; Gong, X. Effect of elevated temperature on mechanical properties of high-volume fly ash-based geopolymer concrete, mortar and paste cured at room temperature. Polymers 2021, 13, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahoti, M.; Wijaya, S.F.; Tan, K.H.; Yang, E.H. Tailoring sodium-based fly ash geopolymers with variegated thermal performance. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 107, 103507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assi, L.N.; Deaver, E.E.; Ziehl, P. Effect of source and particle size distribution on the mechanical and microstructural properties of fly Ash-Based geopolymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 167, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Gong, L.; Shi, L.; Cao, W.; Pan, Y.; Cheng, X. Experimental investigation on the influencing factors of preparing porous fly ash-based geopolymer for insulation material. Energy Build. 2018, 168, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, D.; Yang, Q. Properties of Gangue Powder Modified Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer. Materials 2023, 16, 5719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, E.M.; Ramamurthy, K. Influence of production on the strength, density and water absorption of aerated geopolymer paste and mortar using Class F fly ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 156, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, X.; Song, Y.; Ban, X.; Zhang, N. Influence of different grinding degrees of fly ash on properties and reaction degrees of geopolymers. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, F.; Gu, G.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H.; Huang, X.; Zhu, J. Pore structure analysis and properties evaluations of fly ash-based geopolymer foams by chemical foaming method. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 19989–19997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Wang, D. Effects of Water on Pore Structure and Thermal Conductivity of Fly Ash-Based Foam Geopolymers. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019, 3202794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroehong, W.; Jaturapitakkul, C.; Pothisiri, T.; Chindaprasirt, P. Effect of Oil Palm Fiber Content on the Physical and Mechanical Properties and Microstructure of High-Calcium Fly Ash Geopolymer Paste. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2018, 43, 5215–5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartono, E.; Diana, W.; Nugraha, Y.; Afzalurrahman, M. View of Compaction Properties of the Fly-Ash Based Geopolymer on Silt Soil. Int. J. Geomate 2024, 26, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenepalli, J.S.; Neeraja, D. Properties of class F fly ash based geopolymer mortar produced with alkaline water. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 19, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, E.U.; Padmanabhan, S.K.; Licciulli, A. Synthesis and characteristics of fly ash and bottom ash based geopolymers-A comparative study. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 2965–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridtirud, C.; Chindaprasirt, P. Properties of lightweight aerated geopolymer synthesis from high-calcium fly ash and aluminium powder. Int. J. GEOMATE 2019, 16, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamhangrittirong, P.; Suwanvitaya, P.; Witayakul, W.; Suwanvitaya, P.; Chindaprasirt, P. Factors influence on shrinkage of high calcium fly ash geopolymer paste. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 610, 2275–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deraman, L.M.; Abdullah, M.M.A.B.; Ming, L.Y.; Hussin, K. Density and morphology studies on bottom ash and fly ash geopolymer brick. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings, Kaohsiung City, Taiwan, 8–9 December 2016; American Institute of Physics Inc.: College Park, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, A.G.; Strecker, K. Production of Fly Ash Based Geopolymers Using Activator Solution with Different Na2O and Na2SiO3 Compositions. Rev. Tecnológica Mar. 2017, 26, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui-Teng, N.; Cheng-Yong, H.; Abdullah, M.M.A.B.; Yong-Sing, N.; Bayuaji, R. Study of fly ash geopolymer and fly ash/slag geopolymer in term of physical and mechanical properties. Eur. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 5, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijeljić, J.; Ristić, N.; Grdić, D.; Pavlović, M. Possibilities of Biomass Wood Ash Usage in Geopolymer Mixtures. Teh. Vjesn. 2023, 30, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilal, A.A.; Nader, A.S.; Kurji, B.M. Producing Sustainable Lightweight Geopolymer Concrete Using Waste Materials. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2024, 20, 1120–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, W.M.W.; AL Mustafa Bakri Abdullah, A.M.; Victor Sandu, K.; Hussin, I.; Gabriel Sandu, K.; Nizar Ismail, A.; Abdul Kadir, M.; Binhussain, P.; Raja, B.; Pahat Johor, K.A. Processing and Characterization of Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer Bricks. Rev. Chim 2014, 65, 1340–1345. [Google Scholar]

- Nurgesang, F.A.; Wattanasiriwech, S.; Wattanasiriwech, D.; Aungkavattana, P. Mechanical Physical Properties of Fly Ash Geopolymer-Mullite Composites Suranaree. J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 23, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, W.M.W.; Hussin, K.; Abdullah, M.M.A.; Kadir, A.A.; Deraman, L.M. Effects of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution concentration on fly ash-based lightweight geopolymer. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings, Krabi, Thailand, 29–30 April 2017; American Institute of Physics Inc.: College Park, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.F.A.; Yun-Ming, L.; Al Bakri, M.M.; Cheng-Yong, H.; Zulkifly, K.; Hussin, K. Effect of Alkali Concentration on Fly Ash Geopolymers. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Bali, Indonesia, 25–26 October 2017; Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi, B.; Sanjayan, J.; Chai, J.X.H.; Lu, T.M. Properties of fresh and hardened glass fiber reinforced fly ash based geopolymer concrete. Key Eng. Mater. 2014, 594, 629–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, R.A.; Abdullah, M.M.A.B.; Yahya, Z.; Jian, A.Z.; Nasri, A. Performance of fly ash based geopolymer incorporating palm kernel shell for lightweight concrete. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings, Krabi, Thailand, 29–30 April 2017; American Institute of Physics Inc.: College Park, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tho-In, T.; Sata, V.; Chindaprasirt, P.; Jaturapitakkul, C. Pervious high-calcium fly ash geopolymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 30, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongsa, A.; Zaetang, Y.; Sata, V.; Chindaprasirt, P. Properties of lightweight fly ash geopolymer concrete containing bottom ash as aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 111, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.M.; Naje, A.S.; Al-Zubaidi, H.A.M.; Al-Kateeb, R.T. Performance evaluation of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete incorporating nano slag. Glob. Nest J. 2019, 21, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkeo, W.; Seekaew, S.; Kaewrahan, O. Properties of High Calcium Fly Ash Geopolymer Lightweight Concrete. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 17, 1423–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadharshini, P.; Ramamurthy, K.; Robinson, R.G. Excavated soil waste as fine aggregate in fly ash based geopolymer mortar. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 146, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ghafri, E.; Al Tamimi, N.; El-Hassan, H.; Maraqa, M.A.; Hamouda, M. Synthesis and multi-objective optimization of fly ash-slag geopolymer sorbents for heavy metal removal using a hybrid Taguchi-TOPSIS approach. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 35, 103721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalewajko, M.; Bołtryk, M. Use of Alkaline-Activated Energy Waste Raw Materials in Geopolymer Concrete. Materials 2024, 17, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naenudon, S.; Vilaivong, A.; Zaetang, Y.; Tangchirapat, W.; Wongsa, A.; Sata, V.; Chindaprasirt, P. High flexural strength lightweight fly ash geopolymer mortar containing waste fiber cement. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 16, e01121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Liu, R.; Pang, B. Impact of particle size of fly ash on the early compressive strength of concrete: Experimental investigation and modelling. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 323, 126444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dong, Y.; El-Naggar, M.R.; Wang, F.; Zhao, Y. The Influence of Particle Size and Calcium Content on Performance Characteristics of Metakaolin- and Fly-Ash-Based Geopolymer Gels. Gels 2024, 10, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Wan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, F.; Wang, J.; Kang, Y. Fly ash particle size effect on pore structure and strength of fly ash foamed geopolymer. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2019, 2019, 1098027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zheng, T.; Zheng, X.; Liu, Y.; Darkwa, J.; Zhou, G. Thermo-mechanical and moisture absorption properties of fly ash-based lightweight geopolymer concrete reinforced by polypropylene fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 251, 118960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irum, S.; Shabbir, F. Performance of fly ash/GGBFS based geopolymer concrete with recycled fine and coarse aggregates at hot and ambient curing. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 95, 110148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkawi, A.B.; Nuruddin, M.F.; Fauzi, A.; Almattarneh, H.; Mohammed, B.S. Effects of Alkaline Solution on Properties of the HCFA Geopolymer Mortars. Procedia Eng. 2016, 148, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, H.; Jiang, L.; Meng, L.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, J. Long-term physical and mechanical properties and microstructures of fly-ash-based geopolymer composite incorporating carbide slag. Materials 2021, 14, 6692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinde, P.; Patankar, S.; Sayyad, A. Investigation on effects of fineness of flyash and alkaline ratio on mechanical properties of geopolymer concrete. Res. Eng. Struct. Mater. 2018, 4, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikoloutsopoulos, N.; Sotiropoulou, A.; Kakali, G.; Tsivilis, S. The Effect of Solid/Liquid Ratio on Setting Time, Workability and Compressive Strength of Fly Ash Based Geopolymers. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 27441–27445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafa, S.A.; Ali, A.Z.M.; Awal, A.S.M.A.; Loon, L.Y. Optimum mix for fly ash geopolymer binder based on workability and compressive strength. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Langkawi, Malaysia, 4–5 December 2017; Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albitar, M.; Visintin, P.; Ali, M.S.M.; Drechsler, M. Assessing behaviour of fresh and hardened geopolymer concrete mixed with class-F fly ash. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2015, 19, 1445–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fan, C.; Wang, B.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z. Workability, rheology, and geopolymerization of fly ash geopolymer: Role of alkali content, modulus, and water–binder ratio. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 367, 130357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luga, E.; Atis, C.D. Optimization of heat cured fly ash/slag blend geopolymer mortars designed by “Combined Design” method: Part 1. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 178, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, M.N.S.; Zhang, H.; Parkinson, S. Optimum mix design of geopolymer pastes and concretes cured in ambient condition based on compressive strength, setting time and workability. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 23, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketana, N.S.; Reddy, V.S.; Rao, M.V.S.; Shrihari, S. Effect of various parameters on the workability and strength properties of geopolymer concrete. Proc. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 309, 01102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghizadeh, A.; Ekolu, S.O. Method for comprehensive mix design of fly ash geopolymer mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 202, 704–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodr, M.; Law, D.W.; Gunasekara, C.; Setunge, S.; Brkljaca, R. Compressive strength and microstructure evolution of low calcium brown coal fly ash-based geopolymer. J. Sustain. Cem. Based Mater. 2020, 9, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romadhon, E.S. The influence of low alkaline activator on the compressive strength and workability of geopolymer concrete. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Rapperswil, Switzerland, 3–12 October 2022; Institute of Physics: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, E. Influence of superplasticizer on workability and strength of ambient cured alkali activated mortar. Clean. Mater. 2022, 6, 100152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, P.S.; Nath, P.; Sarker, P.K. The effects of ground granulated blast-furnace slag blending with fly ash and activator content on the workability and strength properties of geopolymer concrete cured at ambient temperature. Mater. Des. 2014, 62, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishanth, L.; Patil, D.N.N. Experimental evaluation on workability and strength characteristics of self-consolidating geopolymer concrete based on GGBFS, flyash and alccofine. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 59, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagajothi, S.; Elavenil, S. Parametric studies on the workability and compressive strength properties of geopolymer concrete. J. Mech. Behav. Mater. 2018, 27, 20180019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuruddin, M.F.; Demie, S.; Ahmed, M.F.; Shafiq, N. Effect of Superplasticizer NaOHMolarity on Workability Compressive Strength Microstructure Properties of Self-Compacting Geopolymer Concrete. Int. J. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2011, 2, 122–129. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Majidi, M.H.; Lampropoulos, A.; Cundy, A. Effect of Alkaline Activator, Water. Superplasticiser and Slag Contents on the Compressive Strength and Workability of Slag-Fly Ash Based Geopolymer Mortar Cured under Ambient Temperature. Int. J. Civ. Environ. Struct. Constr. Archit. Eng. 2016, 10, 308–312. [Google Scholar]

- Rajput, B.S.; Rajawat, S.P.S.; Jain, G. Effect of curing conditions on the compressive strength of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 103, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Zhu, Z.; Peng, Y.; Wan, Y.; Xu, X.; Pu, S.; Song, S.; Wei, Y. Effect of steel slag on fresh, hardened and microstructural properties of high-calcium fly ash based geopolymers at standard curing condition. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 229, 116933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaid, M.T.; Kayali, O.; Khennane, A.; Black, J. A mix design procedure for low calcium alkali activated fly ash-based concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 79, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangarao, M.L.S.; Pradhan, B. Effect of chloride and blend of chloride and sulphate salts on workability, early strength and microstructure of FA-GGBS geopolymer concrete. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 65, 3907–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chithambaram, S.J.; Kumar, S.; Prasad, M.M.; Adak, D. Effect of parameters on the compressive strength of fly ash based geopolymer concrete. Struct. Concr. 2018, 19, 1202–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topark-Ngarm, P.; Chindaprasirt, P.; Sata, V. Setting Time, Strength, and Bond of High-Calcium Fly Ash Geopolymer Concrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2015, 27, 04014198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naenudon, S.; Wongsa, A.; Ekprasert, J.; Sata, V.; Chindaprasirt, P. Enhancing the properties of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete using recycled aggregate from waste ceramic electrical insulator. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 68, 106132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P.; Sarker, P.K. Effect of GGBFS on setting, workability and early strength properties of fly ash geopolymer concrete cured in ambient condition. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 66, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, R.M.; Butt, F.; Zhu, X.; Jiang, T.; Tufail, R.F. A comprehensive study on the factors affecting the workability and mechanical properties of ambient cured fly ash and slag based geopolymer concrete. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbayrak, A.; Kucukgoncu, H.; Atas, O.; Aslanbay, H.H.; Aslanbay, Y.G.; Altun, F. Determination of stress-strain relationship based on alkali activator ratios in geopolymer concretes and development of empirical formulations. Structures 2023, 48, 2048–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.; Ho, W.K.; Tu, W.; Zhang, M. Workability and mechanical properties of alkali-activated fly ash-slag concrete cured at ambient temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 172, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardhono, A.; Law, D.W.; Sutikno; Dani, H. The effect of slag addition on strength development of Class C fly ash geopolymer concrete at normal temperature. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings, East Java, Indonesia, 8–9 August 2017; American Institute of Physics Inc.: College Park, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi, B.; Sanjayan, J. Effect of different superplasticizers and activator combinations on workability and strength of fly ash based geopolymer. Mater. Des. 2014, 57, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Dang, X.; Zhang, J.; Yi, P.; Li, Y. Mechanical Properties of Fly Ash-Slag Based Geopolymer for Repair of Road Subgrade Diseases. Polymers 2023, 15, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunarsih, E.S.; As’ad, S.; Sam, A.R.M.; Kristiawan, S.A. Properties of Fly Ash-Slag-Based Geopolymer Concrete with Low Molarity Sodium Hydroxide. Civ. Eng. J. 2023, 9, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assi, L.N.; Deaver, E.; Elbatanouny, M.K.; Ziehl, P. Investigation of early compressive strength of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 112, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.K.; Yoo, S.W.; Jung, S.H.; Lee, K.M.; Kwon, S.J. Effect of Na2O content, SiO2/Na2O molar ratio, and curing conditions on the compressive strength of FA-based geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 145, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, A.A.; Horianto, X. The effect of temperature and duration of curing on the strength of fly ash based geopolymer mortar. Procedia Eng. 2014, 95, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Rashid, K.; Tariq, Z.; Ju, M. Utilization of a novel artificial intelligence technique (ANFIS) to predict the compressive strength of fly ash-based geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 301, 124251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantasinghar, S.; Singh, S.P. Effect of synthesis parameters on compressive strength of fly ash-slag blended geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 170, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukmak, P.; Horpibulsuk, S.; Shen, S.L. Strength development in clay-fly ash geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 40, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.U.; Mohammed, A.S.; Qaidi, S.M.A.; Faraj, R.H.; Sor, N.H.; Mohammed, A.A. Compressive strength of geopolymer concrete composites: A systematic comprehensive review, analysis and modeling. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2023, 27, 1383–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guades, E.J. Experimental investigation of the compressive and tensile strengths of geopolymer mortar: The effect of sand/fly ash (S/FA) ratio. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 127, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, M.; Horpibulsuk, S.; Arulrajah, A. Strength development of Recycled Asphalt Pavement—Fly ash geopolymer as a road construction material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 117, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suksiripattanapong, C.; Horpibulsuk, S.; Chanprasert, P.; Sukmak, P.; Arulrajah, A. Compressive strength development in fly ash geopolymer masonry units manufactured from water treatment sludge. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 82, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A.M.; Bakri, A.; Kamarudin, H.; Bnhussain, M.; Rafiza, A.R.; Zarina, Y. Effect of Na2SiO3/NaOHRatios NaOHMolarities on Compressive Strength of Fly-Ash-Based Geopolymer. ACI Mater. J. 2012, 109, 503–508. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, N.H.A.S.; Samadi, M.; Ariffin, N.F.; Hussin, M.W.; Bhutta, M.A.R.; Sarbini, N.N.; Khalid, N.H.A.; Aminuddin, E. Effect of Curing Conditions on Compressive Strength of FA-POFA-based Geopolymer Mortar. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Istanbul, Turkey, 8–9 August 2018; Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangdaeng, S.; Phoo-ngernkham, T.; Sata, V.; Chindaprasirt, P. Influence of curing conditions on properties of high calcium fly ash geopolymer containing Portland cement as additive. Mater. Des. 2014, 53, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulrajah, A.; Kua, T.A.; Horpibulsuk, S.; Phetchuay, C.; Suksiripattanapong, C.; Du, Y.J. Strength and microstructure evaluation of recycled glass-fly ash geopolymer as low-carbon masonry units. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 114, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.; Chen, R.; Zhu, S.; Lin, J.; Tai, P. Compressive strength of fly ash based geopolymer utilizing waste completely decomposed granite. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.U.; Mohammed, A.A.; Rafiq, S.; Mohammed, A.S.; Mosavi, A.; Sor, N.H.; Qaidi, S.M.A. Compressive strength of sustainable geopolymer concrete composites: A state-of-the-art review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, M.N.S.; Al-Azzawi, M.; Yu, T. Effects of fly ash characteristics and alkaline activator components on compressive strength of fly ash-based geopolymer mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 175, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meesala, C.R.; Verma, N.K.; Kumar, S. Critical review on fly-ash based geopolymer concrete. Struct. Concr. 2020, 21, 1013–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Li, X.; Tan, J.; Vandevyvere, B. Thermal and compressive behaviors of fly ash and metakaolin-based geopolymer. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 30, 101307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyamany, H.E.; Elmoaty, A.E.M.A.; Elshaboury, A.M. Setting time and 7-day strength of geopolymer mortar with various binders. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 187, 974–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dong, H.; Zhao, X.; Wang, K.; Gao, X. Utilisation of Bayer red mud for high-performance geopolymer: Competitive roles of different activators. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e05047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puligilla, S.; Mondal, P. Role of slag in microstructural development and hardening of fly ash-slag geopolymer. Cem. Concr. Res. 2013, 43, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, B.; Roy, L.B.; Rajjak, M. A statistical investigation of different parameters influencing compressive strength of fly ash induced geopolymer concrete. Struct. Concr. 2018, 19, 1268–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, F.; Aslani, F.; Valizadeh, A. Compressive and tensile strength fracture models for heavyweight geopolymer concrete. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2020, 231, 107023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Gao, K.; Zhang, P. Experimental and statistical study on mechanical characteristics of geopolymer concrete. Materials 2020, 13, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguy, H.H.; Lương, Q.H.; Choi, J.I.; Ranade, R.; Li, V.C.; Lee, B.Y. Ultra-ductile behavior of fly ash-based engineered geopolymer composites with a tensile strain capacity up to 13.7%. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 122, 104133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.N.; Qureshi, M.I.; Abid, M.M.; Zia, A.; Tariq, M.A.U.R. An Investigation of Mechanical Properties of Fly Ash Based Geopolymer and Glass Fibers Concrete. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, L.L.; Wang, W.S.; Liu, W.D.; Wu, M. Development and characterization of fly ash based PVA fiber reinforced Engineered Geopolymer Composites incorporating metakaolin. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 108, 103521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratap, B.; Mondal, S.; Rao, B.H. Development of geopolymer concrete using fly ash and phosphogypsum as a pavement composite material. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 93, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, J.C.; Ma, R.Y.; Xu, L.Y.; Li, Y.; Shen, Y.N.; Yao, J.; Wang, Y.S.; Xie, T.Y.; Huang, B.T. Fly ash-dominated High-Strength Engineered/Strain-Hardening Geopolymer Composites (HS-EGC/SHGC): Influence of alkalinity and environmental assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 447, 141182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, M.H.; Sharif, M.B.; Irfan-ul-Hassan, M.; Sahar, U.U.; Akmal, U.; Mohamed, A. Up-scaling of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete to investigate the binary effect of locally available metakaolin with fly ash. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivia, M.; Nikraz, H. Properties of fly ash geopolymer concrete designed by Taguchi method. Mater. Des. 2012, 36, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Pradeepa, J.; Ravindra, P.M. Experimental Investigations on Optimal Strength Parameters of Fly Ash Based Geopolymer Concrete. Int. J. Civ. Struct. Civ. Eng. Res. 2013, 2, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Rathod, G.; Sanni, P.S.H. Microstructure Studies on the Effect of Alkaline Activators to Flyash Ratio on Geopolymer Concrete. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2023, 11, 1220–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Abd, A.; Taman, M.; Behiry, R.N.; El-Naggar, M.R.; Eissa, M.; Hassan, A.M.A.; Bar, W.A.; Mongy, T.; Osman, M.; Hassan, A.; et al. Neutron imaging of moisture transport, water absorption characteristics and strength properties for fly ash/slag blended geopolymer mortars: Effect of drying temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 449, 138436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitarz, M.; Hager, I.; Choińska, M. Evolution of mechanical properties with time of fly-ash-based geopolymer mortars under the effect of granulated ground blast furnace slag addition. Energies 2020, 13, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Li, S. Effect of Curing Age on Tensile Properties of Fly Ash Based Engineered Geopolymer Composites (FA-EGC) by Uniaxial Tensile Test and Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity Method. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Mater. Sci. Ed. 2023, 38, 1319–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezabih, T.; Kanali, C.; Thuo, J. Effects of teff straw ash on the mechanical and microstructural properties of ambient cured fly ash-based geopolymer mortar for onsite applications. Results Eng. 2023, 18, 101123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adak, D.; Sarkar, M.; Mandal, S. Effect of nano-silica on strength and durability of fly ash based geopolymer mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 70, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarsa, P.; Gupta, R. Comparative study involving effect of curing regime on elastic modulus of geopolymer concrete. Buildings 2020, 10, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellum, R.R.; Muniraj, K.; Indukuri, C.S.R.; Madduru, S.R.C. Investigation on Performance Enhancement of Fly ash-GGBFS Based Graphene Geopolymer Concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadesh, P.; Nagarajan, V.; Karthik Arunachalam, K. Effect of nano titanium di oxide on mechanical properties of fly ash and ground granulated blast furnace slag based geopolymer concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 61, 105235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, P.S.; Khan, M.N.N.; Sarker, P.K.; Barbhuiya, S. Nanomechanical characterization of ambient-cured fly ash geopolymers containing nanosilica. J. Sustain. Cem. Based Mater. 2022, 11, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslanbay, Y.G.; Aslanbay, H.H.; Özbayrak, A.; Kucukgoncu, H.; Atas, O. Comprehensive analysis of experimental and numerical results of bond strength and mechanical properties of fly ash based GPC and OPC concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 416, 135175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellum, R.R. Influence of steel and PP fibers on mechanical and microstructural properties of fly ash-GGBFS based geopolymer composites. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 6808–6818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Wang, C.; Yang, H.; Chen, J.; Dong, Z.; Li, L.Y. Development of a ternary high-temperature resistant geopolymer and the deterioration mechanism of its concrete after heat exposure. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 449, 138291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.T.; Ahn, N.; Le, T.A.; Lee, K. Theoretical and experimental study on mechanical properties and flexural strength of fly ash-geopolymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 106, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, D.; Chen, K.; Mao, N.; Zhang, Z. Effect of Ca content on the synthesis and properties of FA-GGBFS geopolymer: Combining experiments and molecular dynamics simulation. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 94, 109908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Yuan, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Wen, T.; Li, J.; Li, F.; Ma, Z.J. Freeze-thaw resistance of Class F fly ash-based geopolymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 222, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]