Bioprospecting Native Oleaginous Microalgae for Wastewater Nutrient Remediation and Lipid Production: An Environmentally Sustainable Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

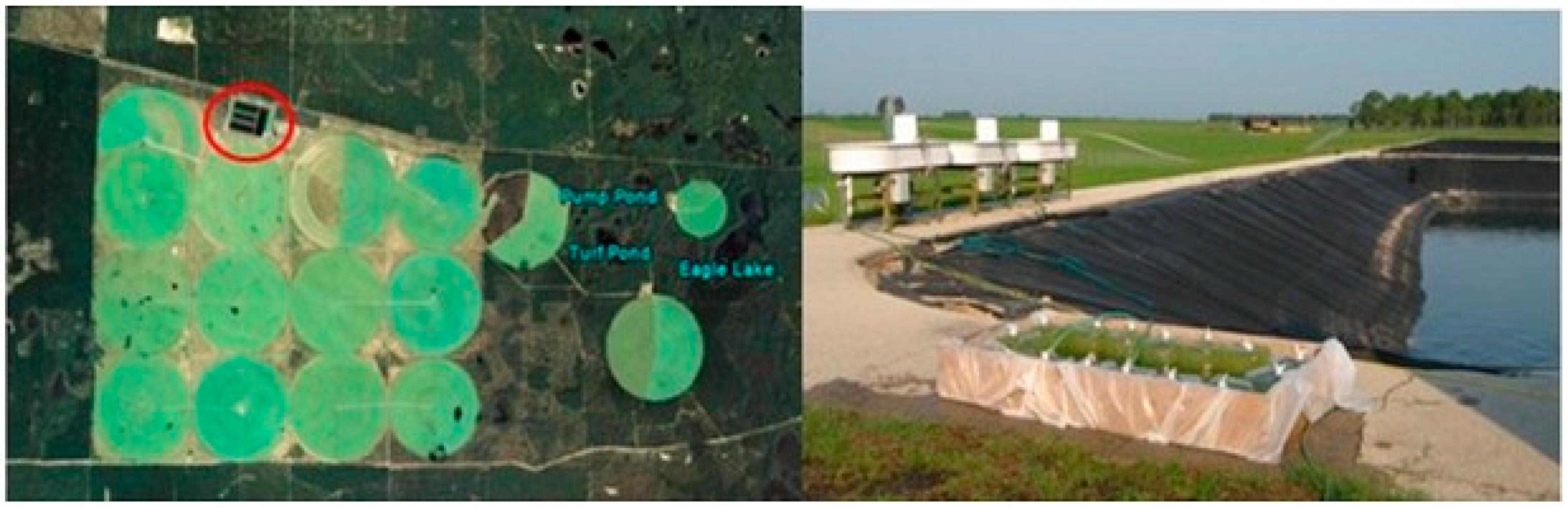

2.1. Wastewater Site Description and Sample Collection

2.2. Cell Sorting Using FACS

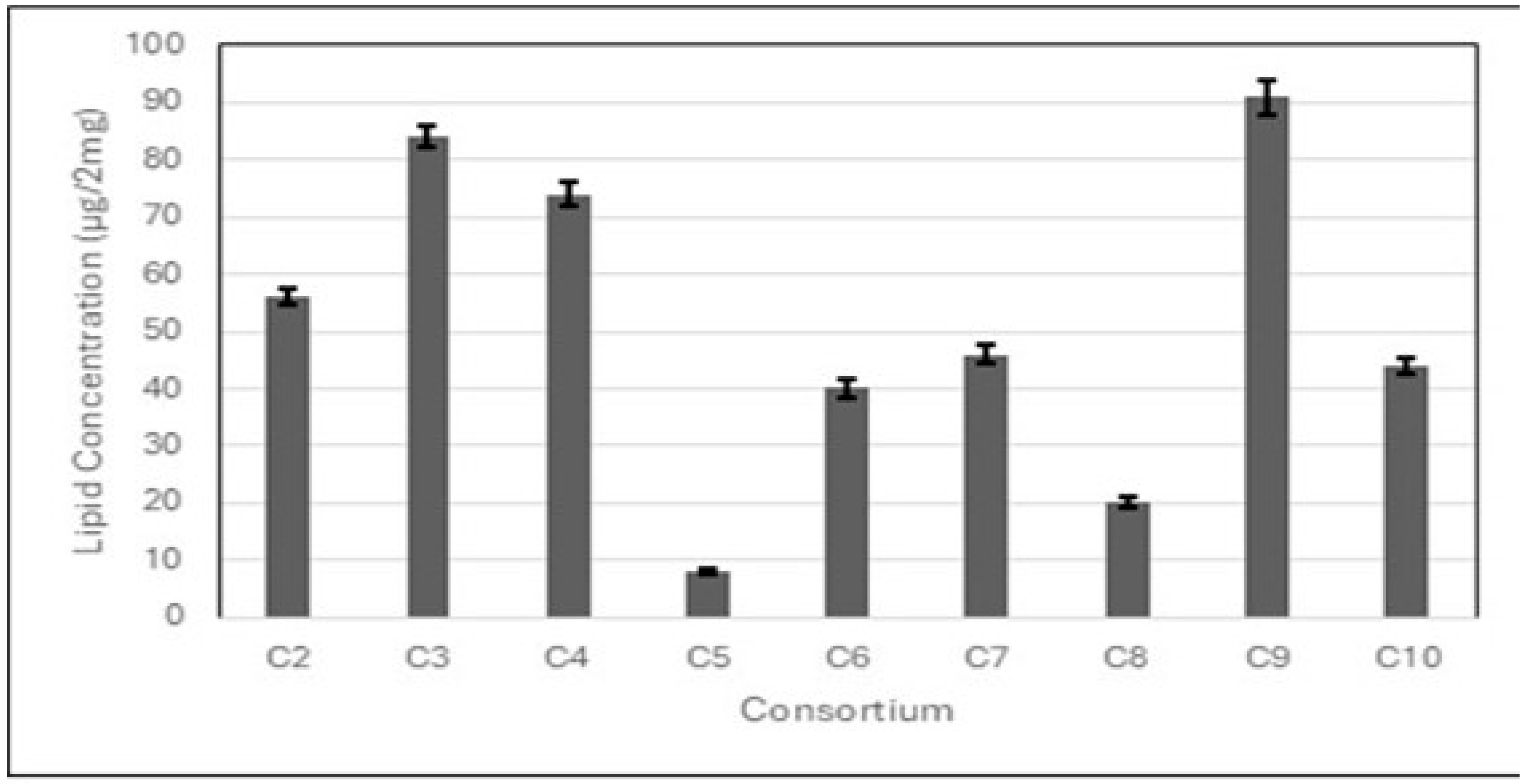

2.3. Screening of the Algal–Microbial Consortia for Lipid Production

2.4. Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis of the Isolated Strains

2.5. Nutrient Depletion from Wastewater Using the Isolated Consortia

2.6. Phosphate, Ammonia, and Nitrate Analyses

2.7. Metagenomic Sequence Accession Numbers

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Isolation of Microalgae from Wastewater Samples

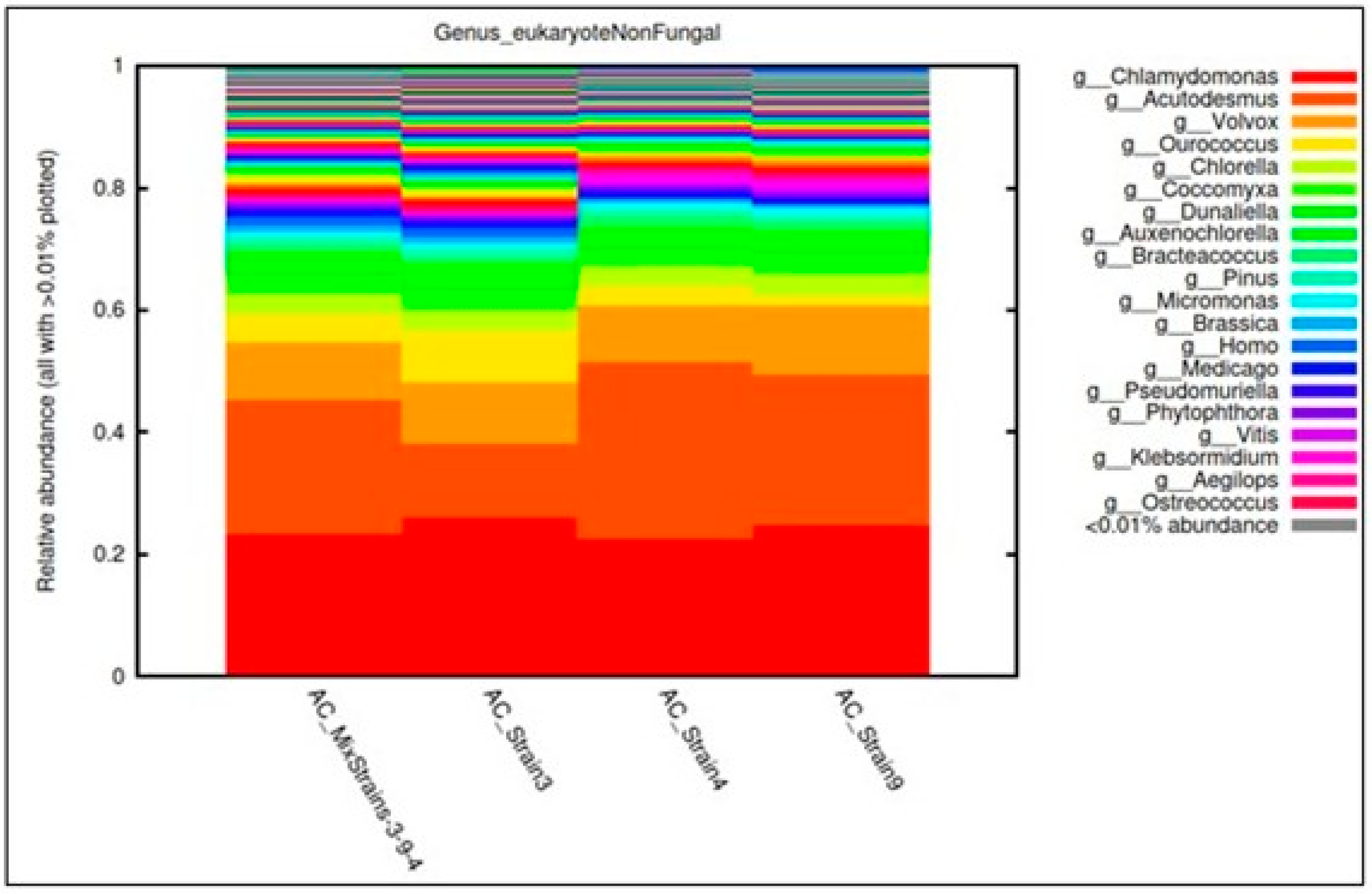

3.2. Identification of the Wastewater Consortium

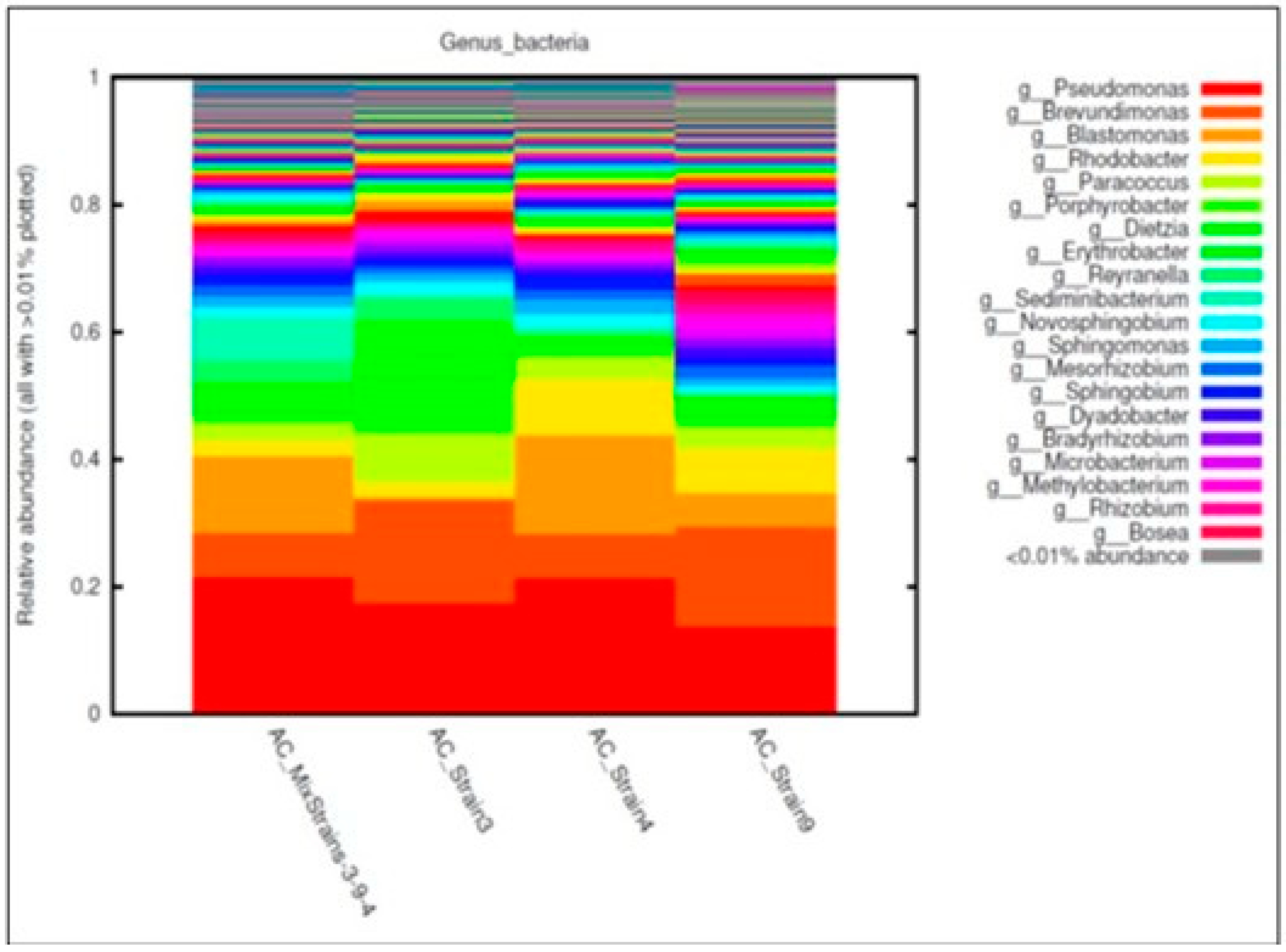

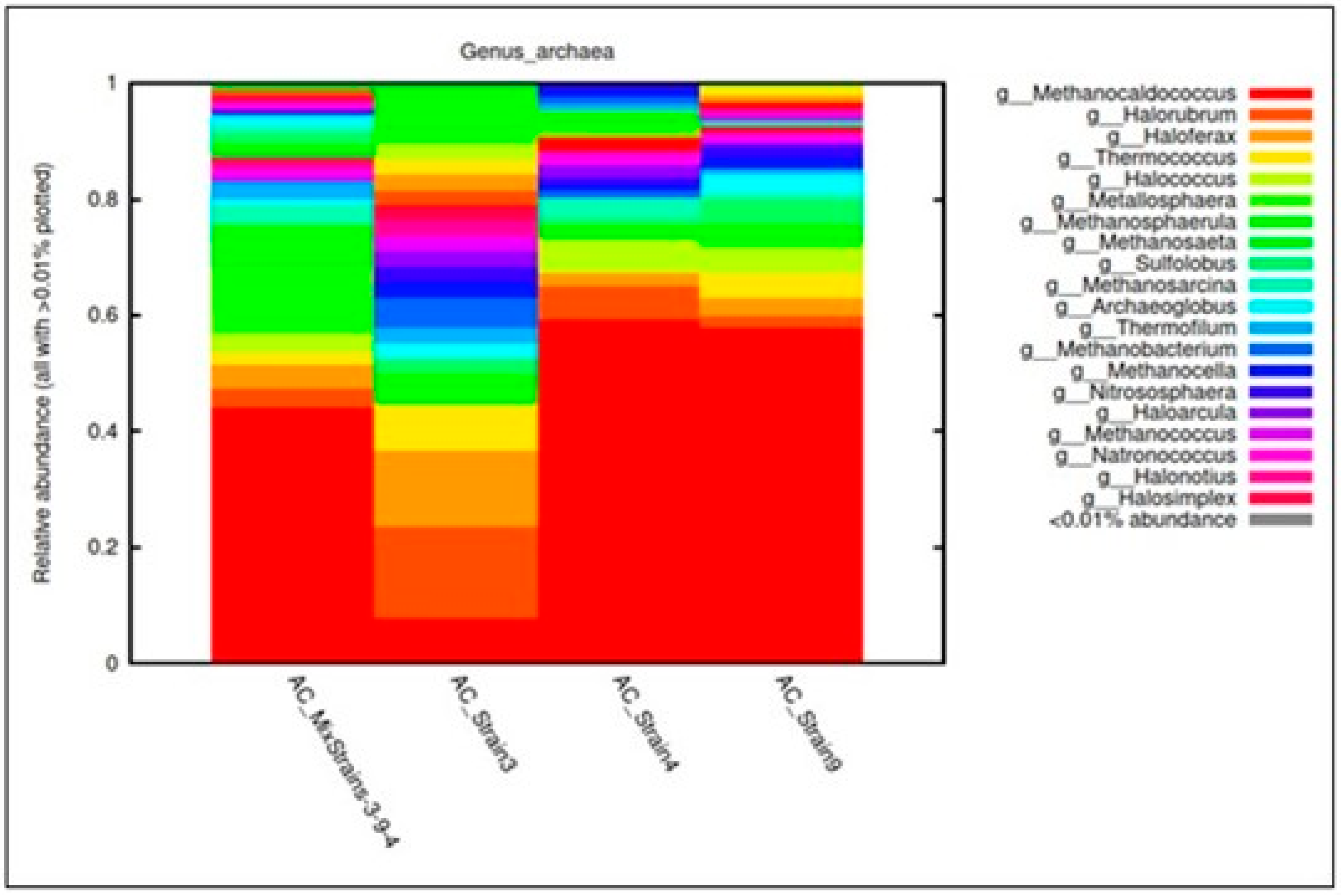

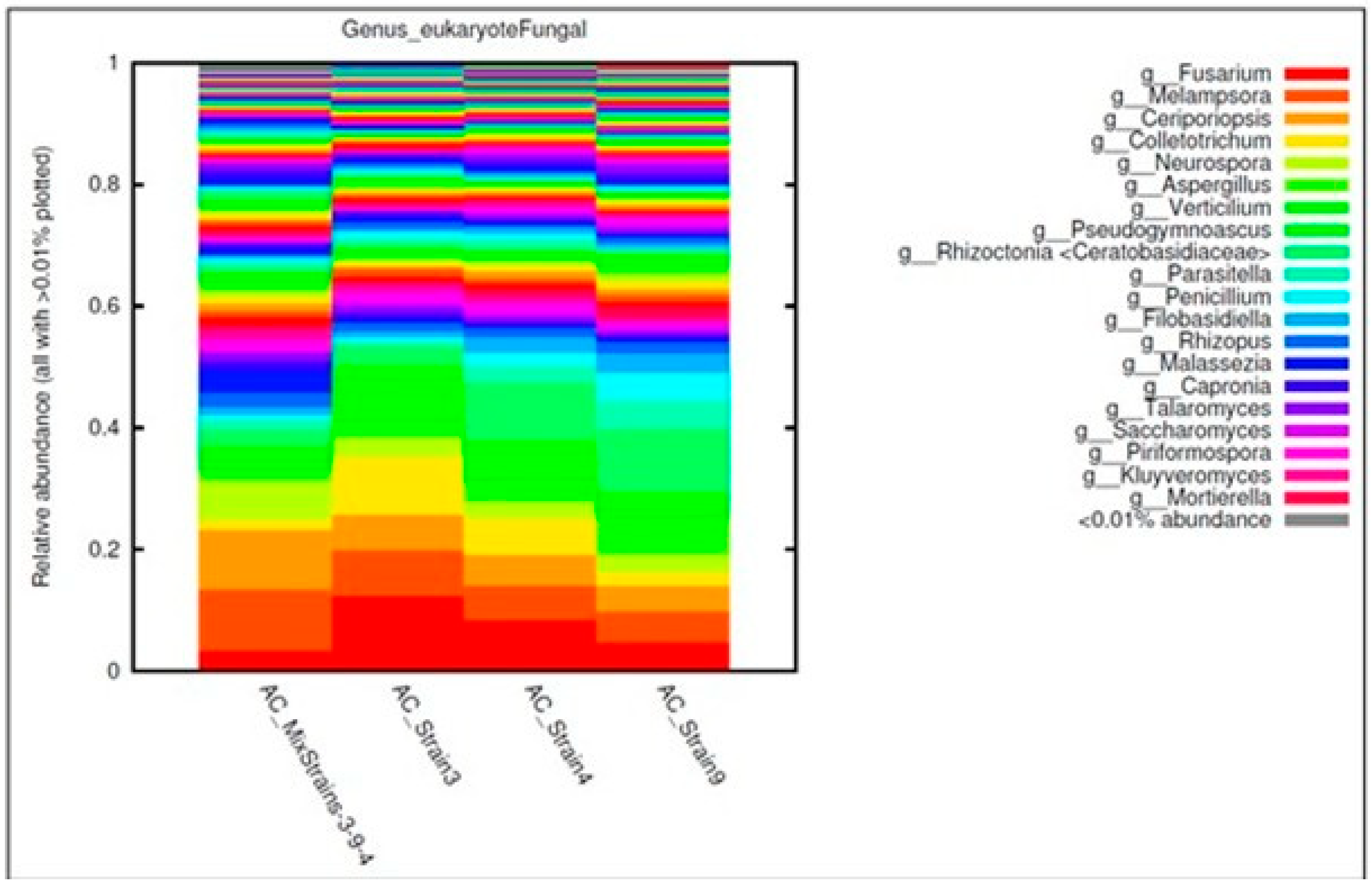

3.3. Bacterial, Archaeal, and Fungal Assemblages in the Consortia

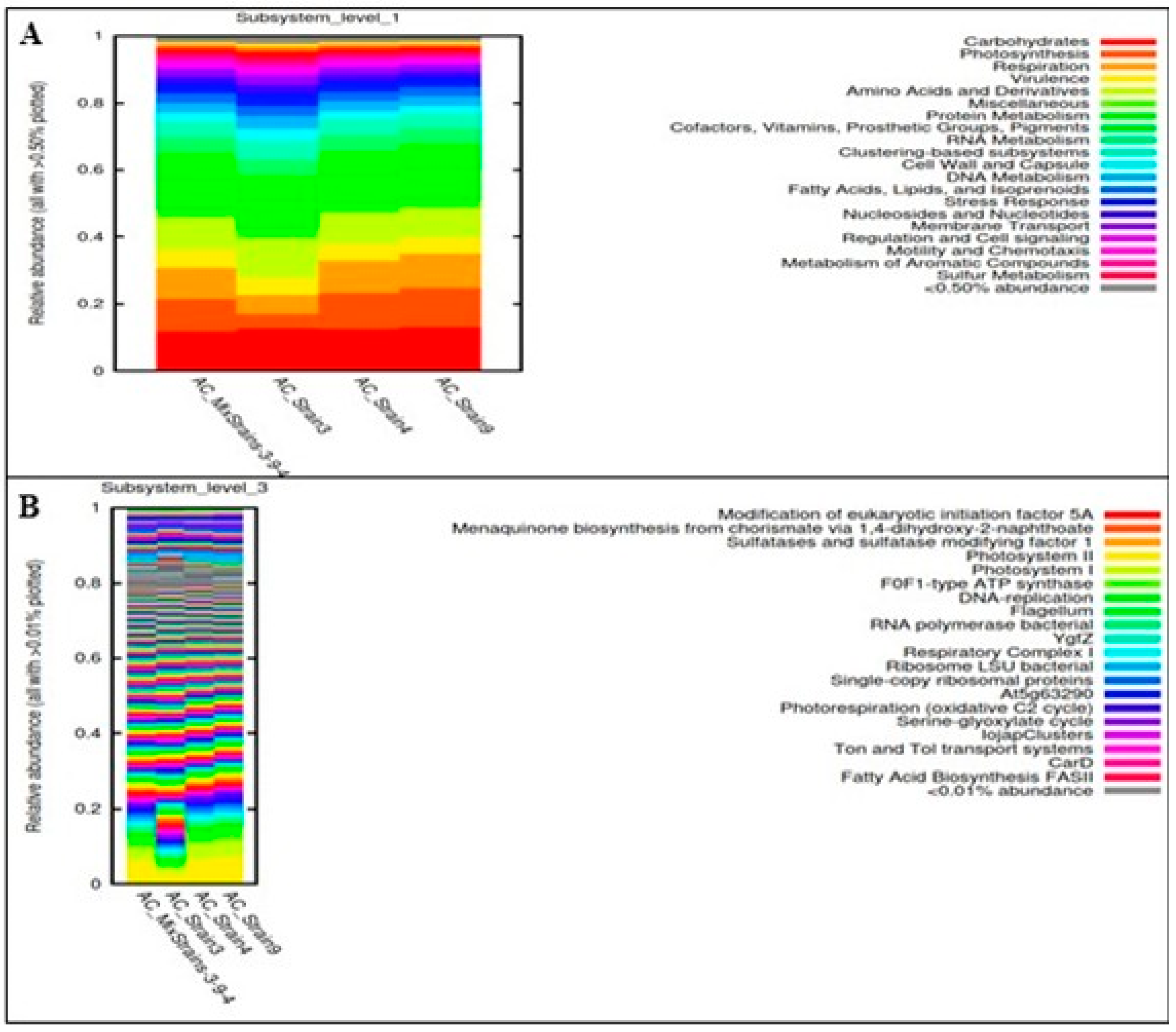

3.4. Gene Functional Analysis in the Consortia

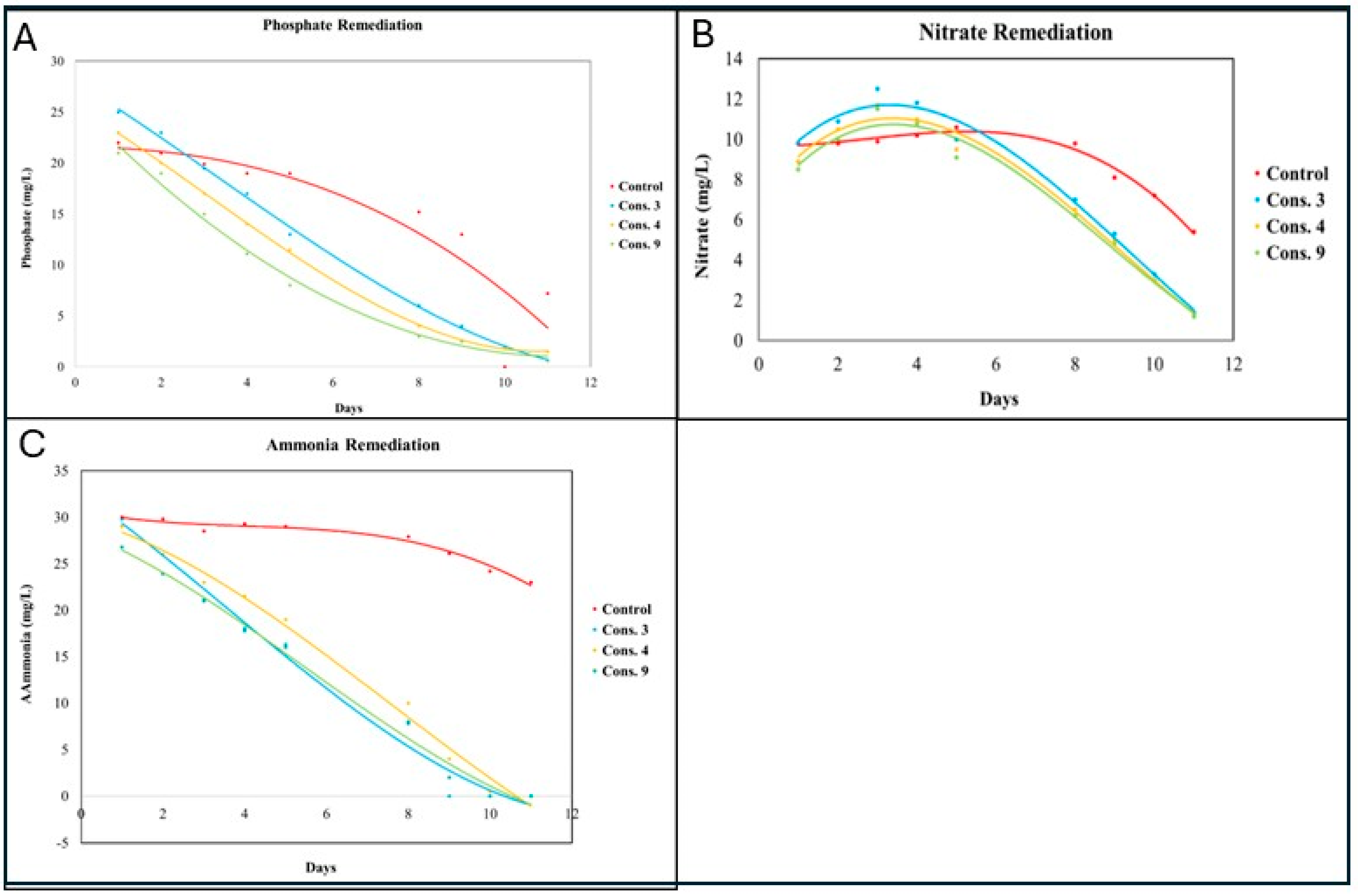

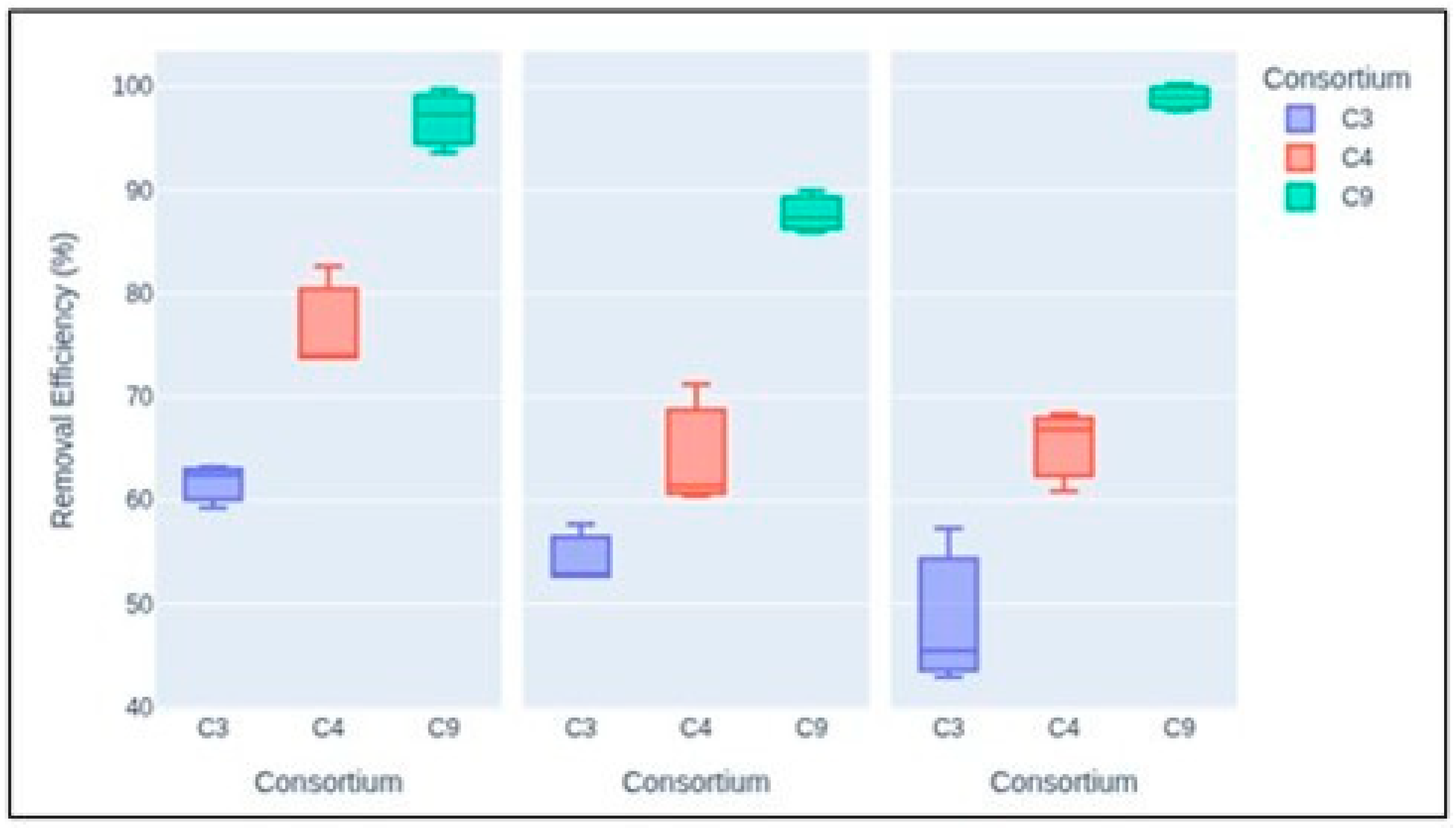

3.5. Wastewater Remediation by the Isolated Consortia

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Neste Corporation. 4 Reasons why the World Needs Biofuels, 2016. Available online: https://www.neste.com/news/4-reasons-why-the-world-needs-biofuels (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- US Department of Energy (DOE). Biofuel Basics. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/bioenergy/biofuel-basics (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Kozyatnyk, I.; Benavente, V.; Weidemann, E.; Jansson, S. Adsorption of organic contaminants of emerging concern using microalgae-derived hydrochars. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ye, X.; Bi, H.; Shen, Z. Microalgae biofuels: Illuminating the path to a sustainable future amidst challenges and opportunities. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2024, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P. Biofuel: Microalgae cut the social and ecological costs. Nature 2007, 450, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, K.; Wager, Y.Z.; Roostaei, J. Co-cultivation of microalgae and bacteria for optimal bioenergy feedstock production in wastewater by using response surface methodology. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthold, D.E.; Shetty, K.G.; Jayachandran, K.; Laughinghouse, H.D.; Gantar, M. Enhancing algal biomass and lipid production through bacterial co-culture. Biomass Bioenergy 2019, 122, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, G.; Wu, G.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhan, X.; Hu, H. Enhanced microalgae growth through stimulated secretion of indole acetic acid by symbiotic bacteria. Algal Res. 2018, 33, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Bernard, O.; Fanesi, A.; Perré, P.; Lopes, F. The effect of light intensity on microalgae biofilm structures and physiology under continuous illumination. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabanelas, I.T.D.; Slegers, P.M.; Böpple, H.; Kleinegris, D.M.; Wijffels, R.H.; Barbosa, M.J. Outdoor performance of Chlorococcum littorale at different locations. Algal Res. 2017, 27, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoro, V.; Azimov, U.; Munoz, J.; Hernandez, H.H.; Phan, A.N. Microalgae cultivation and harvesting: Growth performance and use of flocculants—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 115, 109364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Leavitt, P.R.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, B. Anthropogenic eutrophication of shallow lakes: Is it occasional? Water Res. 2022, 221, 118728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, H. Phosphorus in Wastewater: What Is It & Why Must It Be Removed? 2022. Available online: https://www.garrisonminerals.com/post/phosphorus-in-wastewater (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Pinelli, D.; Bovina, S.; Rubertelli, G.; Martinelli, A.; Guida, S.; Soares, A.; Frascari, D. Regeneration and modelling of a phosphorous removal and recovery hybrid ion exchange resin after long term operation with municipal wastewater. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.N.; Altaf, M.M.; Khan, N.A.; Khan, A.H.; Khan, A.A.; Ahmed, S.; Kumar, P.S.; Naushad, M.; Rajapaksha, A.U.; Iqbal, J.; et al. Recent technologies for nutrient removal and recovery from wastewaters: A review. Chemosphere 2021, 277, 130328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, R.; Santos, J.; Nguyen, H.; Carvalho, G.; Noronha, J.; Nielsen, P.H.; Reis, M.A.; Oehmen, A. Metabolism and ecological niche of Tetrasphaera and Ca. Accumulibacter in enhanced biological phosphorus removal. Water Res. 2017, 122, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, J.; Yang, Y.; WTsang, D.C.; Wang, H.; Chen, H.; Gao, B. Recovery of phosphorus from wastewater: A review based on current phosphorous removal technologies. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 53, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plouviez, M.; Brown, N. Polyphosphate accumulation in microalgae and cyanobacteria: Recent advances and opportunities for phosphorus upcycling. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2024, 90, 103207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P. Smith Water Reclamation Facility. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_P._Smith_Water_Reclamation_Facility (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Faried, M.; Khalifa, A.; Samer, M.; Attia, Y.A.; Moselhy, M.A.; Yousef, R.S.; Abdelbary, K.; Abdelsalam, E.M. Biostimulation of green microalgae Chlorella sorokiniana using nanoparticles of MgO, Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2, and ZnO for increasing biodiesel production. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Xiao, R.; Kong, F.; Zhao, L.; Xing, D.; Ma, J.; Ren, N.; Liu, B. Enhanced biomass and lipid accumulation of mixotrophic microalgae by using low-strength ultrasonic stimulation. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 272, 606–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laezza, C.; Salbitani, G.; Carfagna, S. Fungal Contamination in Microalgal Cultivation: Biological and Biotechnological Aspects of Fungi-Microalgae Interaction. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huy, M.; Kumar, G.; Kim, H.; Kim, S. Photoautotrophic cultivation of mixed microalgae consortia using various organic waste streams towards remediation and resource recovery. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 247, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acién Fernández, F.G.; María, J. Recovery of Nutrients from Wastewaters Using Microalgae. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 2, 396930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, W.; Gotaas, H. Photosynthesis in Sewage Treatment. Trans. Am. Soc. Civ. Eng. 1957, 122, 73–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanan, R.; Kim, B.; Cho, D.; Oh, H.; Kim, H. Algae–bacteria interactions: Evolution, ecology and emerging applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Dell’Orto, M.; D’Imporzano, G.; Bani, A.; Dumbrell, A.J.; Adani, F. The structure and diversity of microalgae-microbial consortia isolated from various local organic wastes. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 347, 126416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City of Tallahassee. Waste Water Services. Available online: https://www.talgov.com/you/wastewater (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Pfeffer, K. Tallahassee WRF: Stringent Limits and Information Modeling, 2025. Available online: https://www.hazenandsawyer.com/projects/process-and-information-modeling-tallahassee-wrf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Pereira, H.; Barreira, L.; Mozes, A.; Florindo, C.; Polo, C.; Duarte, C.V.; Custódio, L.; Varela, J. Microplate-based high throughput screening procedure for the isolation of lipid-rich marine microalgae. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2011, 4, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, T.; Ramanna, L.; Rawat, I.; Bux, F. BODIPY staining, an alternative to the Nile Red fluorescence method for the evaluation of intracellular lipids in microalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 114, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayati, M.; Rajabi Islami, H.; Shamsaie Mehrgan, M. Light Intensity Improves Growth, Lipid Productivity, and Fatty Acid Profile of Chlorococcum oleofaciens (Chlorophyceae) for Biodiesel Production. BioEnergy Res. 2020, 13, 1235–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.K.; Suh, W.I.; Farooq, W.; Moon, M.; Shrivastav, A.; Park, M.S.; Yang, J.-W. Rapid quantification of microalgal lipids in aqueous medium by a simple colorimetric method. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 155, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchfink, B.; Xie, C.; Huson, D.H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huson, D.H.; Auch, A.F.; Qi, J.; Schuster, S.C. MEGAN analysis of metagenomic data. Genome Res. 2007, 17, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, G.G.Z.; Green, K.T.; Dutilh, B.E.; Edwards, R.A. SUPER-FOCUS: A tool for agile functional analysis of shotgun metagenomic data. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Milledge, J.; Abubakar, A.; Swamy, R.; Bailey, D.; Harvey, P. Effects of centrifugal stress on cell disruption and glycerol leakage from Dunaliella salina. Microalgae Biotechnol. 2015, 1, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, M.; Karlberg, B.; Olsson, R.J. Determination of nitrate in municipal waste water by UV spectrophotometer. Anal. Chim. Acta 1995, 312, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivakumar, S.; Serlini, N.; Esteves, S.M.; Miros, S.; Halim, R. Cell Walls of Lipid-Rich Microalgae: A Comprehensive Review on Characterisation, Ultrastructure, and Enzymatic Disruption. Fermentation 2024, 10, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhariwal, A.; Chong, J.; Habib, S.; King, I.L.; Agellon, L.B.; Xia, J. Microbiome Analyst: A web-based tool for comprehensive statistical, visual and meta-analysis of microbiome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W180–W188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, Q.X.; Li, L.; Martinez, B.; Chen, P.; Ruan, R. Culture of microalgae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii in wastewater for biomass feedstock production. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2010, 160, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Simsek, H. Bioavailability of Wastewater Derived Dissolved Organic Nitrogen to Green Microalgae Selenastrum capricornutum, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, and Chlorella vulgaris with/without Presence of Bacteria. J. Environ. Sci. 2017, 57, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, S.; Nemati, A.; Montazeri-Najafabady, N.; Mobasher, M.A.; Morowvat, M.H.; Ghasemi, Y. Treating Urban Wastewater: Nutrient Removal by Using Immobilized Green Algae in Batch Cultures. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2015, 17, 1177–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutra, E.; Grammatikopoulos, G.; Kornaros, M. Microalgal post-treatment of anaerobically digested agro-industrial wastes for nutrient removal and lipids production. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 224, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, R.E. Green Algae as Model Organisms for Biological Fluid Dynamics. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2015, 47, 343–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, D.; Santos, K.N.; Nagpala, R.T.; Opulencia, R.B. Metataxonomic Characterization of Enriched Consortia Derived from Oil Spill-Contaminated Sites in Guimaras, Philippines, Reveals Major Role of Klebsiella sp. in Hydrocarbon Degradation. Int. J. Microbiol. 2023, 2023, 3247448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numberger, D.; Ganzert, L.; Zoccarato, L.; Mühldorfer, K.; Sauer, S.; Grossart, H.-P.; Greenwood, A.D. Characterization of bacterial communities in wastewater with enhanced taxonomic resolution by full-length 16S rRNA sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Qu, Y.-Y.; Zhang, X.-W.; Shen, W.-L.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Wang, J.-W.; Zhang, Z.-J.; Zhou, J.-T. Identification of the microbial community composition and structure of coal-mine wastewater treatment plants. Microbiol. Res. Spec. Issue Biodivers. 2015, 175, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, M.; Sforza, E. Exploiting symbiotic interactions between Chlorella protothecoides and Brevundimonas diminuta for an efficient single-step urban wastewater treatment. Water Sci. Technol. 2018, 78, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.-G.; Ko, S.-R.; Lee, J.-W.; Lee, C.S.; Ahn, C.-Y.; Oh, H.-M.; Jin, L. Blastomonas fulva sp. nov., aerobic photosynthetic bacteria isolated from a Microcystis culture. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 3071–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.; Ganzerli, S.; Rugiero, I.; Pellizzari, S.; Pedrini, P.; Tamburini, E. Potential of Rhodobacter capsulatus Grown in Anaerobic-Light or Aerobic-Dark Conditions as Bioremediation Agent for Biological Wastewater Treatments. Water 2017, 9, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabari, L.; Gannoun, H.; Khelifi, E.; Cayol, J.; Godon, J.; Hamdi, M.; Fardeau, M. Bacterial ecology of abattoir wastewater treated by an anaerobic digestor. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2016, 47, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi, P.; Li, J.; Boadi, P.O.; Meng, J.; Koblah Quashie, F.; Wang, X.; Ren, N.; Buelna, G. Efficiency of an upflow anaerobic sludge blanket reactor treating potato starch processing wastewater and related process kinetics, functional microbial community and sludge morphology. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 239, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerbergen, K.; Geel, M.V.; Waud, M.; Willems, K.A.; Dewil, R.; Impe, J.V.; Appels, L.; Lievens, B. Assessing the composition of microbial communities in textile wastewater treatment plants in comparison with municipal wastewater treatment plants. MicrobiologyOpen 2017, 6, e00413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Lorenzo, C.; Sipkema, D.; Rodríguez-Díaz, M.; Fuentes, S.; Juárez-Jiménez, B.; Rodelas, B.; Smidt, H.; González-López, J. Microbial community dynamics in a submerged fixed bed bioreactor during biological treatment of saline urban wastewater. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 71, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, N.D.; Miskin, I.P.; Kornilova, O.; Curtis, T.P.; Head, I.M. Occurrence and activity of Archaea in aerated activated sludge wastewater treatment plants. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 4, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, K.; Matsuyama, S.; Igarashi, K.; Utsumi, M.; Shiraiwa, Y.; Kuwabara, T. Anaerobic coculture of microalgae with Thermosipho globiformans and Methanocaldococcus jannaschii at 68 °C enhances generation of n-alkane-rich biofuels after pyrolysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 924–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaei, M.; Rahim, R.A.; Abdullah, N.; Wright, A.G.; Shirai, Y.; Sakai, K.; Sulaiman, A.; Hassan, M.A. Importance of the methanogenic archaea populations in anaerobic wastewater treatments. Process Biochem. 2010, 45, 1214–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karray, F.; Ben Abdallah, M.; Baccar, N.; Zaghden, H.; Sayadi, S. Production of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) by Haloarcula, Halorubrum, and Natrinema Haloarchaeal Genera Using Starch as a Carbon Source. Archaea 2021, 2021, 8888712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salwan, R.; Sharma, V. (Eds.) Physiological and Biotechnological Aspects of Extremophiles; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torregrosa-Crespo, J.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.; Esclapez, J.; Bautista, V.; Pire, C.; Camacho, M.; Richardson, D.; Bonete, M. Anaerobic Metabolism in Haloferax Genus: Denitrification as Case of Study. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 2016, 68, 41–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assress, H.A.; Selvarajan, R.; Nyoni, H.; Ntushelo, K.; Mamba, B.B.; Msagati, T.A.M. Diversity, Co-occurrence and Implications of Fungal Communities in Wastewater Treatment Plants. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Shangguan, M.; Zhou, C.; Peng, Z.; An, Z. Construction of a mycelium sphere using a Fusarium strain isolate and Chlorella sp. For polyacrylamide biodegradation and inorganic carbon fixation. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1270658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, A.; Budenkova, E.; Babich, O.; Sukhikh, S.; Dolganyuk, V.; Michaud, P.; Ivanova, S. Influence of Carbohydrate Additives on the Growth Rate of Microalgae Biomass with an Increased Carbohydrate Content. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Edwards, B., III; Simon, D.P.; Pathak, A.; Alvarez, D.; Chauhan, A. Bioprospecting Native Oleaginous Microalgae for Wastewater Nutrient Remediation and Lipid Production: An Environmentally Sustainable Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11166. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411166

Edwards B III, Simon DP, Pathak A, Alvarez D, Chauhan A. Bioprospecting Native Oleaginous Microalgae for Wastewater Nutrient Remediation and Lipid Production: An Environmentally Sustainable Approach. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11166. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411166

Chicago/Turabian StyleEdwards, Bobby, III, Daris P. Simon, Ashish Pathak, Devin Alvarez, and Ashvini Chauhan. 2025. "Bioprospecting Native Oleaginous Microalgae for Wastewater Nutrient Remediation and Lipid Production: An Environmentally Sustainable Approach" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11166. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411166

APA StyleEdwards, B., III, Simon, D. P., Pathak, A., Alvarez, D., & Chauhan, A. (2025). Bioprospecting Native Oleaginous Microalgae for Wastewater Nutrient Remediation and Lipid Production: An Environmentally Sustainable Approach. Sustainability, 17(24), 11166. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411166