Sustainability in the Built Environment Reflected in Serious Games: A Systematic Narrative Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the challenges and limitations of incorporating sustainability in the built environment in serious games?

- Which types of games are more successful in raising awareness of sustainability in education on the built environment?

- What aspects of sustainability have been included in games, and what topics are missing?

- How do games related to sustainability in the built environment address educational barriers?

- What engagement strategies have been applied in these games?

2. Methods

3. Results Analysis

3.1. Integration of Sustainability in Serious Games

3.1.1. Pedagogical Approaches in Sustainability Games

- Systems thinking and holistic learning emerges as a central pedagogical approach, enabling students to grasp the complex interdependencies among product life cycles, economic and legislative frameworks, and their broader social and environmental impacts [41]. By situating sustainability within both local and global contexts, across time scales and under conditions of uncertainty, games foster a deeper, more integrated understanding of sustainability challenges. They encourage learners to link individual decisions with systemic outcomes, reinforcing how sustainability is shaped by dynamic interactions across political, economic, and regulatory systems [35].

- Experiential, interactive, and reflective learning represents a key pedagogical strategy in sustainability games. Reviewed games create problem-based environments where players actively engage with sustainability challenges through decision-making and real-time feedback [10]. For instance, games that incorporate LEED principles exemplify this approach by offering interactive, metric-based scenarios that require students to make design decisions while reflecting on the sustainability implications of their choices [29]. Other games place learners in dynamic virtual environments, where they must adapt and apply sustainable design solutions under changing conditions, further enhancing interactivity and experiential depth [21]. These simulated environments provide safe spaces for experimentation, enabling players to explore complex sustainability challenges and develop practical decision-making skills [33,37]. Reflective learning is encouraged through feedback systems, such as badges and leaderboards, that reinforce understanding of trade-offs among environmental, social, and economic factors [38].

- Simulation-based learning and the use of visualizations represent another key pedagogical approach, where simulation tools enable players to assess the consequences of their decisions, such as ecological footprints, and evaluate the long-term impacts of material and design choices on profitability, sustainability, and performance [31,32]. Paired with simulation, visualizations support cognitive engagement by translating complex environmental processes—like land use and resource management—into accessible, interactive formats, making sustainability challenges more tangible and compelling [38].

- Collaborative learning has been effectively integrated into several games, engaging students in both synchronous and asynchronous activities such as quests and collective problem-solving [25]. These platforms often empower students to design their own scenarios, fostering deeper engagement and personalized, learner-driven experiences. Moreover, by simulating multi-stakeholder interactions and incorporating diverse perspectives, these games emphasize the value of openness, negotiation, and shared responsibility [41], highlighting that achieving sustainability in the built environment requires collective, interdisciplinary collaboration. Whether digital or non-digital, serious games immerse players in the complexities of sustainability and promote cognitive shifts from individual concerns to collective responsibility [23,27], reinforcing the need for holistic, globally coordinated action.

3.1.2. Communicating Sustainability Through Game Mechanics

3.2. Engagement in Serious Games

Engagement Strategies

- Immediate Feedback enhances decision-making by allowing players to quickly evaluate the impact of their choices and adjust strategies accordingly.

- Story-Driven Gameplay increases immersion and emotional connection, particularly when narratives are rooted in sustainability themes relevant to the target audience.

- Scaffolding for Challenging Concepts ensures that players remain engaged even when faced with complex sustainability scenarios, preventing frustration while supporting deeper learning.

3.3. Game Characteristics and Structures

- (1)

- The first category represents a temporal aspect of the game. Sustainable Development Goals often target long-term challenges, such as reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Consequently, it is expected that sustainability-oriented games will align closely with this long-term perspective. Indeed, many reviewed games specifically address long-term sustainability issues. For example, [37] address market and systemic inertia in adopting energy-efficient technologies in the built environment over time. However, effectively engaging users and illustrating abstract, long-term challenges within a game setting poses difficulties. As a result, some of the game designers opt to demonstrate an integration of time-sensitive and long-term topics. These games are mainly focused on sustainability challenges such as early-stage design decisions [32], urban development considering environmental impact [31], and behaviors that have lasting effects on product life cycles, costs, and sustainability [32].

- (2)

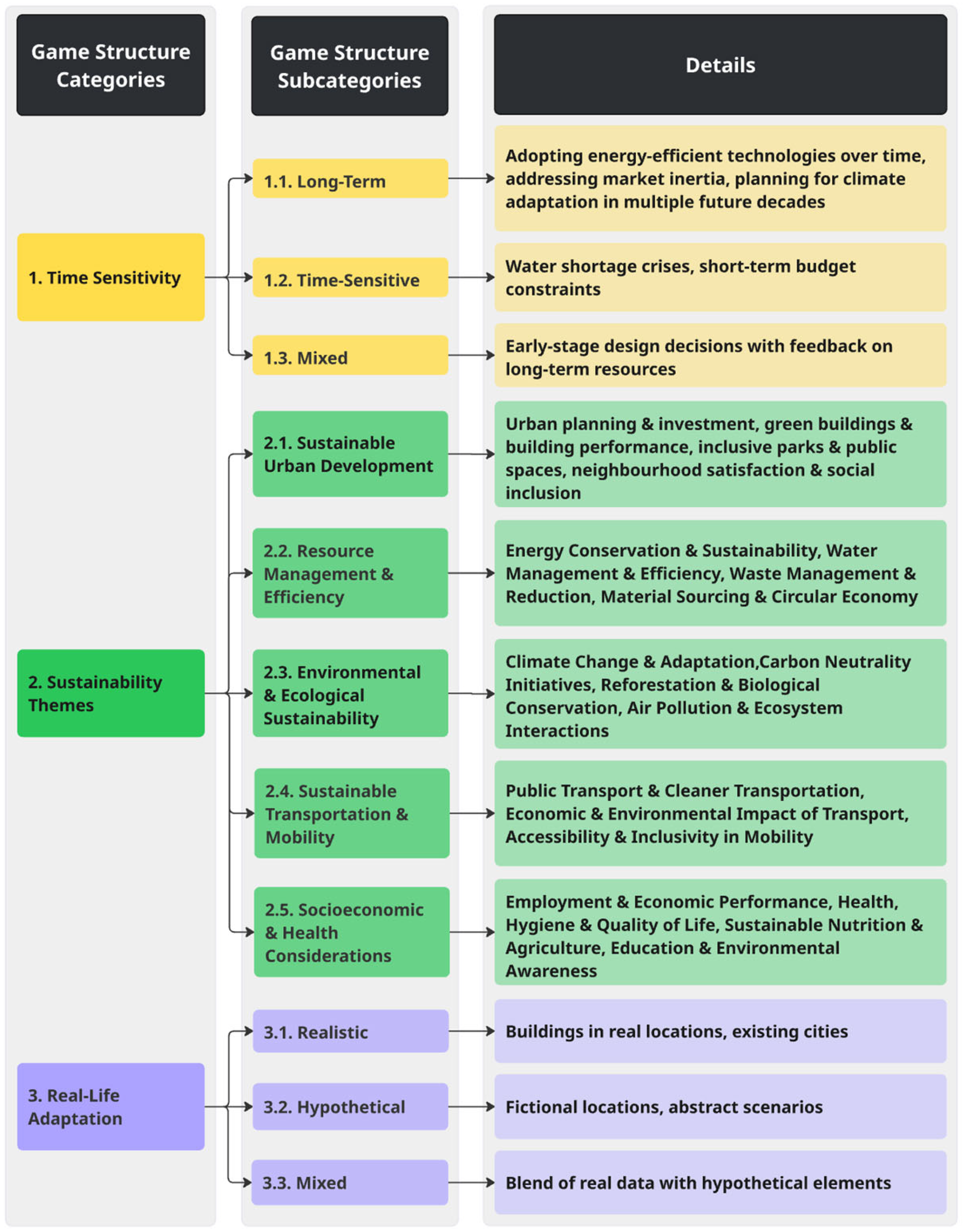

- The second difference in game structures is based on the game themes. As depicted in Figure 1, games address various issues within the built environment. Some games incorporate multi sustainability topics; for example, Tilvawala et al. [33] addresses key sustainability aspects: energy efficiency, waste management, water conservation, sustainable materials, and indoor environmental quality. On the other hand, Hayhow et al. [30] focuses on life cycle analysis for residential development. Five primary categories of themes have been recognized: (2.1) sustainable urban development, (2.2) resource management & efficiency, (2.3) environmental & ecological sustainability, (2.4) sustainable transportation & mobility, and (2.5) socioeconomic & health considerations. Sub-categories for each theme are represented in Figure 1.

- (3)

- The Third category in the game structure reflects the contextual framing of the subject. The subcategories include: (3.1) games based on realistic context, (3.2) hypothetical location, and (3.3) a mix of the two mentioned items. All three categories involve players in real-life challenges and missions; however, they are different in terms of the game’s location. The subcategories represent games in (3.1) real-world locations, (3.2) hypothetical locations, and (3.3) those that are not location dependent. The games in the first subcategory engage players in addressing a sustainability challenge in a defined location. For example, Tsai et al. [28] simulates Taiwan’s economic development process through teaching the balance between biological conservation and economic development. In Mohammed & Pruyt [37], the Dutch residential sector’s transition to sustainable energy technologies is explored. In another example [31], the environmental impact of the decisions is measured and reported to inform about the CO2 emission for the production and consumption of goods and services needed to sustain the lifestyles of the community settled in Milan, Italy. The second subcategory (3.2) focuses on addressing challenges rather than recreating a real location. For example, [19] deploys realistic scenarios to reflect real urban management challenges. Games in the third subcategory (3.3) address sustainability challenges independently of any specific geographic context. Games in this subcategory range from a small-scale problem, for example, addressing building design challenges [20], to large-scale issues, for instance, achieving multiple sustainable development goals [25].

4. Challenges and Optimization Paths

4.1. Challenges and Recommendations for Integration of Sustainability in Serious Games

4.2. Challenges and Recommendations for Engagement in Serious Games

5. Conclusions

5.1. Research Innovations

5.2. Practical Implications for Designers, Planners, and Educators

- Inclusive by design: Diverse stakeholders should be engaged in the co-creation process, with disability access, Indigenous and local knowledge systems, and culturally varied narratives systematically incorporated.

- SDG-anchored and systems-oriented: Game mechanics and outcomes should be explicitly mapped to relevant SDG targets and indicators, with cross-scale feedback and trade-offs represented rather than isolated metrics.

- Transparent and explainable: Model assumptions, data provenance, and scoring logic should be made explicit, and simulations should be paired with structured debriefs to address uncertainty and unintended effects.

- Scaffolded engagement: Role-based collaboration, authentic decision tasks, immediate feedback, and adaptive difficulty should be integrated, supported by facilitation guides and post-game reflection activities.

- Transfer to action: In-game decisions should be explicitly linked to real-world pathways, such as checklists, policy instruments, design heuristics, or campus/community projects, and accompanied by opportunities for reflection on long-term impacts.

5.3. Final Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abt, C.C. Serious Games; University Press of America: Lanham, MD, USA, 1987; Available online: https://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr=&id=axUs9HA-hF8C&oi=fnd&pg=PR13&dq=Serious+Games+Book+by+Clark+C.+Abt&ots=d0U4blvauQ&sig=aewDGfGToF7QqR0nIVfXgP7y5tI (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Deterding, S.; Dixon, D.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L. From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining “gamification”. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments, Tampere, Finland, 28–30 September 2011; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, J.; Djaouti, D. An Introduction to Serious Game Definitions and Concepts. Serious Games & Simulation for Risks Management. December 2011. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-04675725 (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Susi, T.; Johannesson, M.; Backlund, P. Serious Games: An Overview. Institutionen för Kommunikation Och Information. 2007. Available online: https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:his:diva-1279 (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- De Gloria, A.; Bellotti, F.; Berta, R. Serious Games for Education and Training. vol. 1, no. 1. 2014. Available online: https://journal.seriousgamessociety.org/~serious/index.php/IJSG/article/view/11 (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Stege, L.; Van Lankveld, G.; Spronck, P. Serious games in education. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Sport 2011, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Young, M.F.; Slota, S.; Cutter, A.B.; Jalette, G.; Mullin, G.; Lai, B.; Simeoni, Z.; Tran, M.; Yukhymenko, M. Our Princess Is in Another Castle: A Review of Trends in Serious Gaming for Education. Rev. Educ. Res. 2012, 82, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhonggen, Y. A Meta-Analysis of Use of Serious Games in Education over a Decade. Int. J. Comput. Games Technol. 2019, 2019, 4797032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P.; Wang, R.; Chatpinyakoop, C.; Nguyen, V.-T.; Nguyen, U.-P. A bibliometric review of research on simulations and serious games used in educating for sustainability, 1997–2019. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouariachi, T.; Olvera-Lobo, M.D.; Gutiérrez-Pérez, J. Serious Games and Sustainability. In Encyclopedia of Sustainability in Higher Education; Leal Filho, W., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1450–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanitsas, M.; Kirytopoulos, K.; Vareilles, E. Facilitating sustainability transition through serious games: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 924–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares-Rodríguez, C.; Villagra, P.; Mardones, R.E.; Cárcamo-Ulloa, L.; Jaramillo, N. Costa Resiliente: A Serious Game Co-Designed to Foster Resilience Thinking. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagra, P.; y Lillo, O.P.; Ariccio, S.; Bonaiuto, M.; Olivares-Rodríguez, C. Effect of the Costa Resiliente serious game on community disaster resilience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 91, 103686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A.; Boyatzis, R.E.; Mainemelis, C. Experiential learning theory: Previous research and new directions. In Perspectives on Thinking, Learning, and Cognitive Styles; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 227–247. Available online: https://api.taylorfrancis.com/content/chapters/edit/download?identifierName=doi&identifierValue=10.4324/9781410605986-9&type=chapterpdf (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in Systems: A Primer; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2008; Available online: https://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr=&id=CpbLAgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=systems+thinking+(Meadows,+2008)&ots=LBngmbqFTZ&sig=jIBVETmIeFTGNznG_156v7dWjIg (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Pineda-Martínez, M.; Llanos-Ruiz, D.; Puente-Torre, P.; García-Delgado, M.Á. Impact of Video Games, Gamification, and Game-Based Learning on Sustainability Education in Higher Education. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Haan, R.-J.; Van der Voort, M.C. On Evaluating Social Learning Outcomes of Serious Games to Collaboratively Address Sustainability Problems: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanne, K. An overview of game-based learning in building services engineering education. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2016, 41, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenia, S.; Barnabè, F.; Pompei, A. Game-Based Learning and Decision-Making for Urban Sustainability: A Case of System Dynamics Simulations. In EURO Working Group on DSS: A Tour of the DSS Developments over the Last 30 Years; Papathanasiou, J., Zaraté, P., Freire de Sousa, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayer, S.K.; Messner, J.I.; Anumba, C.J. Augmented Reality Gaming in Sustainable Design Education. J. Archit. Eng. 2016, 22, 04015012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dib, H.; Adamo-Villani, N. Serious Sustainability Challenge Game to Promote Teaching and Learning of Building Sustainability. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2014, 28, A4014007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehiyazaryan, E. Game-based Learning in Design and Technology-an Evaluation of a Multimedia Learning Environment. In Proceedings of the International Design and Technology Association Conference-Designing the Future DATA, Beijing, China, 23–25 October 2006; Available online: https://repository.lboro.ac.uk/articles/online_resource/Game-based_learning_in_Design_and_Technology_an_evaluation_of_a_multi-media_environment/9344933 (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Ho, S.-J.; Hsu, Y.-S.; Lai, C.-H.; Chen, F.-H.; Yang, M.-H. Applying game-based experiential learning to comprehensive sustainable development-based education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, Y.-K.; Chao, T.-W. Game-Based Learning for Green Building Education. Sustainability 2015, 7, 5592–5608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilanioti, I. Teaching a serious game for the sustainable development goals in the scratch programming tool. Eur. J. Eng. Technol. Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lameras, P.; Petridis, P.; Dunwell, I.; Hendrix, M.; Arnab, S.; de Freitas, S.; Stewart, C. A game-based approach for raising awareness on sustainability issues in public spaces. In Proceedings of the Spring Servitization Conference: Servitization in the Multi-Organisation Enterprise, Birmingham, UK, 20–21 May 2013; pp. 20–21. Available online: https://pure.coventry.ac.uk/ws/files/3939006/A%20game-based%20approach.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Lupini, S.; Bertella, G.; Font, X. Reflexive monitoring for sustainable transformations: A game-based workshop methodology for participatory learning. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2024, 5, 100149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.-C.; Liu, S.-Y.; Chang, C.-Y.; Chen, S.-Y. Using a Board Game to Teach about Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dib, H.; Adamo-Villani, N.; Niforooshan, R. A Serious Game for Learning Sustainable Design and LEED Concepts. In Proceedings of the Computing in Civil Engineering, Clearwater Beach, FL, USA, 17–20 June 2012; pp. 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayhow, S.; Parn, E.A.; Edwards, D.J.; Hosseini, M.R.; Aigbavboa, C. Construct-it: A board game to enhance built environment students’ understanding of the property life cycle. Ind. High. Educ. 2019, 33, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, M.; Rogora, A. A Serious Game Proposal for Exploring and Designing Urban Sustainability. In Technological Imagination in the Green and Digital Transition; Arbizzani, E., Cangelli, E., Clemente, C., Cumo, F., Giofrè, F., Giovenale, A.M., Palme, M., Paris, S., Eds.; The Urban Book Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurati, G.W.; Nylander, J.W.; Ferrise, F.; Bertoni, M. Sustainability awareness in engineering design through serious gaming. Des. Sci. 2022, 8, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilvawala, K.; Myers, M.D.; Sundaram, D. Designing Serious Games for a Sustainable World. 2019. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/confirm2019/25/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Mostafa, S.; Salim, H.; Stewart, R.; Bertone, E.; Liu, T.; Gratchev, I. A Framework for Game-based Learning on Sustainability for Construction and Engineering Students. In Proceedings of the REES AAEE 2021 conference: Engineering Education Research Capability Development, Perth, Western Australia, 5–8 December 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenia, S.; Ciobanu, N.; Kulakowska, M.; Myrovali, G.; Papathanasiou, J.; Pompei, A.; Tsaples, G.; Tsironis, L. An innovative game-based approach for teaching urban sustainability. In Proceedings of the 2019 Balkan Region Conference on Engineering and Business Education, Sibiu, Romania, 16–19 October 2019; pp. 338–343. Available online: https://iris.uniroma1.it/handle/11573/1454111 (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Isaacs, J.; Falconer, R.; Blackwood, D. A unique approach to visualising sustainability in the built environment. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Conference Visualisation, London, UK, 8–11 July 2008; pp. 3–10. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/4568665/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Mohammed, I.; Pruyt, E. Speeding Up Energy Transitions: Gaming Towards Sustainability in the Dutch Built Environment. In Infranomics; Gheorghe, A.V., Masera, M., Katina, P.F., Eds.; Topics in Safety, Risk, Reliability and Quality; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 24, pp. 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muenz, T.S.; Schaal, S.; Groß, J.; Paul, J. How a Digital Educational Game Can Promote Learning about Sustainability. Sci. Educ. Int. 2023, 34, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlili, A.; Agyemang Adarkwah, M.; Salha, S.; Huang, R. How environmental perception affects players’ in-game behaviors? Towards developing games in compliance with sustainable development goals. Entertain. Comput. 2024, 50, 100678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiannoutsou, N.; Kynigos, C.; Daskolia, M. Constructionist designs in game modding: The case of learning about sustainability. Proc. Constr. 2014, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurati, G.W.; Kwok, S.Y.; Ferrise, F.; Bertoni, M. A study on the potential of game based learning for sustainability education. Proc. Des. Soc. 2023, 3, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Paper Categorization | Number of Papers | Citations | Game Type | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analog Games | Digital Games | |||

| Game evaluation | 11 | [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28] | 4 | 4 |

| Game proposal | 5 | [29,30,31,32,33] | 2 | 3 |

| Game framework | 1 | [34] | 0 | 1 |

| Assessment of sustainability aspect(s) through games | 3 | [21,35,36,37,38,39] | 1 | 2 |

| Game review papers | 5 | [10,11,16,17,18] | - | - |

| Criteria | Sub-Criteria |

|---|---|

| Sustainability Incorporation | Overall Approach; SDG Inclusion; Themes; Character Inclusivity; Real-Life Context; Problem Timeframe; Awareness vs. Solutions; Teaching and Learning; Sustainability Integration; Sustainability Message Clarity; Challenges in Incorporating Sustainability |

| Engagement Strategies | Playability; Re-playability; Aesthetic Appeal; Context Application; Engagement Strategies; Guidance; Engagement Challenges |

| Game Characteristics and Structures | Game Name; Game Type; Participation Type; Gameplay; Time Limit; Scoring Systems; Target Audience; Built Environment Scale; Time Sensitivity; Sustainability Themes; Real-Life Framing |

| Cat. | Criteria | Source(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Learning Mechanics | Role-play | [21,23] |

| Randomized elements | [25] | |

| Topic expansion or modification options | [25] | |

| Adaptation to real life | [19,20,23] | |

| Immediate feedback | [19,20] | |

| Self-directed learning | [23] | |

| Collaborative decision-making | [20,30,32] | |

| Competitive elements | [24,28] | |

| Story-driven gameplay | [30] | |

| Rewards and advancement systems | [24,21] | |

| Active learning (problem-solving, critical thinking) | [19,20,23] | |

| Time pressure | [21,23] | |

| Progressively increasing difficulty | [21,25] | |

| Aesthetics | Multimedia or Immersive | [20,23] |

| Digital Effects | [20] | |

| Simplified Design | [30,32] | |

| Real-Life App. | Practical Solutions | [19,20,23] |

| Decision-Making | [19,23] | |

| Subject-Specified | [23,26] | |

| Theoretical | [25] | |

| Guidance | Fully teacher-guided | [20] |

| Tutorials provided | [20,23] | |

| Scaffolding provided for challenging concepts | [20,23] | |

| Guided scenarios | [20] | |

| In-game hints & feedback | [19,20] | |

| Peer-based guidance | [23] | |

| Post-game debriefing | [23] | |

| No Guidance | [25] |

| Game Characteristic | Category | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Game Type | Traditional board/card game | 3 | 8.60% |

| Hybrid game (mix of board and digital elements) | 6 | 17.10% | |

| Fully digital game with advanced interactions | 15 | 42.90% | |

| Participation Type | Solo Play | 2 | 5.70% |

| Supports Both Solo and Team-Based Play | 10 | 28.60% | |

| Team-Based | 12 | 34.30% | |

| Game Play | Collaborative (Individual Progression) | 3 | 8.60% |

| Mix of competition and collaboration | 7 | 20% | |

| Competition | 14 | 40% | |

| Time Limit | No Time Constraints | 4 | 11.40% |

| Mix of Limited Time Scenarios | 9 | 25.70% | |

| Strict time constraints to simulate real-world pressure | 11 | 31.40% | |

| Scoring System | Unstructured Scoring System | 5 | 14.30% |

| Qualitative Feedback System | 7 | 20% | |

| Structured Point-Based System | 12 | 34.30% | |

| Target Audience | General Public (Informal Learners) | 3 | 8.60% |

| Pre-University Students | 9 | 25.70% | |

| Higher education/professionals | 12 | 34.30% | |

| Built Environment Scale | Product-level decision-making | 3 | 8.60% |

| City/urban planning level | 6 | 17.10% | |

| Building-focused sustainability decisions | 15 | 42.90% |

| Challenge | Recommendations to Address These Challenges | Potential Barriers and Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of Inclusivity in Sustainability Games | Incorporating disability, Indigenous perspectives, and diverse ethnic representation in games. | Some aspects of inclusivity and accessibility are not purely physical, making it difficult to integrate qualitative aspects into games. |

| Insufficient Integration of the SDGs | Since the SDGs are clearly organized by targets and indicators, they can be integrated into games based on relevant topics. | Some game scenarios address multiple topics, making it difficult to categorize them under specific SDGs as they may span several goals. |

| Complexity and Decision-Making Challenges | Streamline complex scenarios into smaller, more manageable ones. | This might lead to oversimplifying complex sustainability challenges, reducing their educational value. |

| Lack of a Common Language Among Stakeholders | Use clearer scenarios and language that can be understood by a wider audience, including those outside the built environment field. | Oversimplification might make it difficult to convey nuanced sustainability challenges accurately. |

| Challenges in Real-World Applicability and Impact | Incorporate long-term impact considerations into game scenarios. | Accounting for long-term real-world scenarios might not be fully feasible due to the complexity and variety of influencing factors. |

| Cognitive Barriers to Sustainability Learning | Design games that accommodate diverse cognitive patterns, allowing players to explore sustainability concepts through different approaches (e.g., visual, experiential, or interactive learning). | Adapting to different cognitive styles may require extensive testing and customization, increasing development time and costs. |

| Aesthetic Limitations in Sustainable Design Games | Not all game elements need high realism; a balance can be struck where key parts have strong aesthetics to enhance learning. | Inconsistencies in design aesthetics may disrupt player immersion and engagement. |

| Consequences of Game Mechanics | Assess the long-term effects of gameplay on players and modify mechanics accordingly to reinforce sustainable behaviors. | Long-term player behavior is difficult to track and measure, making it challenging to determine the exact impact of game mechanics. |

| Engagement Strategy | Challenges | Potential Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Immediate feedback | Players struggled without real-time responses to their actions, making it hard to adjust strategies or understand consequences. | Incorporate dynamic, real-time feedback systems to guide decision-making and reinforce learning outcomes |

| Self-directed learning | Some players felt lost or overwhelmed when games lacked structure; others didn’t know how to explore effectively without prompts. | Balance open-ended exploration with optional guidance or learning checkpoints to maintain autonomy and prevent confusion |

| Collaboration (group work) | Disagreements and coordination issues reduced engagement; lack of real-time communication in digital formats further complicated collaboration. | Design well-structured collaborative mechanics and provide communication tools to support teamwork and goal alignment |

| Competitive elements | Excessive competition reduced cooperation and led to aggressive strategies that undermined educational goals. | Balance competitive and cooperative mechanics to maintain motivation while supporting shared learning |

| Story-driven gameplay | When not well-integrated, stories failed to engage or lacked connection to educational content. | Develop meaningful, context-rich narratives that tie directly to learning objectives and decision outcomes |

| Rewards and advancement systems | Players focused more on points than understanding concepts; extrinsic rewards sometimes overshadowed intrinsic motivation. | Use rewards to reinforce learning milestones, but ensure gameplay centers on meaningful sustainability decision-making |

| Active learning | Some games were too complex or fast-paced, limiting players’ ability to apply critical thinking effectively. | Incorporate scaffolding and pacing tools that allow deeper exploration and reflection on complex decisions |

| Time pressure | Fast-paced gameplay caused stress and impaired decision-making, especially for complex tasks. | Offer adjustable timing options or buffers to allow thoughtful decision-making while preserving challenge |

| Progressively increasing difficulty | Games that were too easy led to boredom, and those that were too hard caused frustration. Some lacked proper progression curves. | Implement adaptive difficulty systems to ensure players are consistently challenged at appropriate levels |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Olgen, B.; Hazbei, M.; Rahimi, N.; Rasoulian, H.; Cucuzzella, C. Sustainability in the Built Environment Reflected in Serious Games: A Systematic Narrative Literature Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11148. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411148

Olgen B, Hazbei M, Rahimi N, Rasoulian H, Cucuzzella C. Sustainability in the Built Environment Reflected in Serious Games: A Systematic Narrative Literature Review. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11148. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411148

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlgen, Burcu, Morteza Hazbei, Negarsadat Rahimi, Hadise Rasoulian, and Carmela Cucuzzella. 2025. "Sustainability in the Built Environment Reflected in Serious Games: A Systematic Narrative Literature Review" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11148. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411148

APA StyleOlgen, B., Hazbei, M., Rahimi, N., Rasoulian, H., & Cucuzzella, C. (2025). Sustainability in the Built Environment Reflected in Serious Games: A Systematic Narrative Literature Review. Sustainability, 17(24), 11148. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411148