The Role of Heterogeneous Marine Environmental Regulation in SDGs-Integrated Marine Economic Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mechanism of Marine Environmental Regulation Affects the SDGs-Integrated Development of the Marine Economy

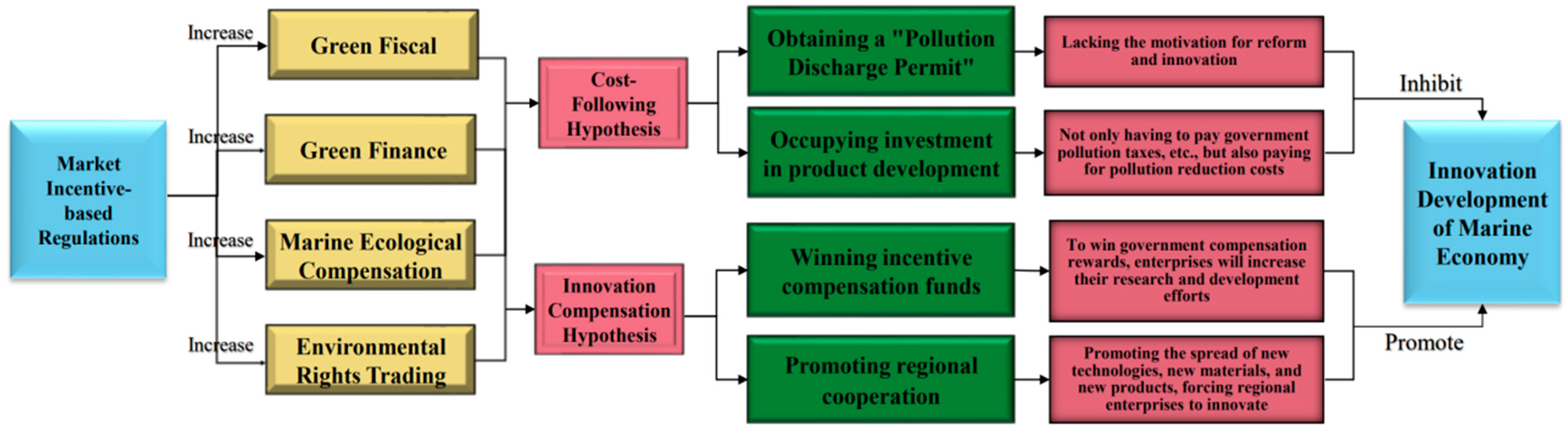

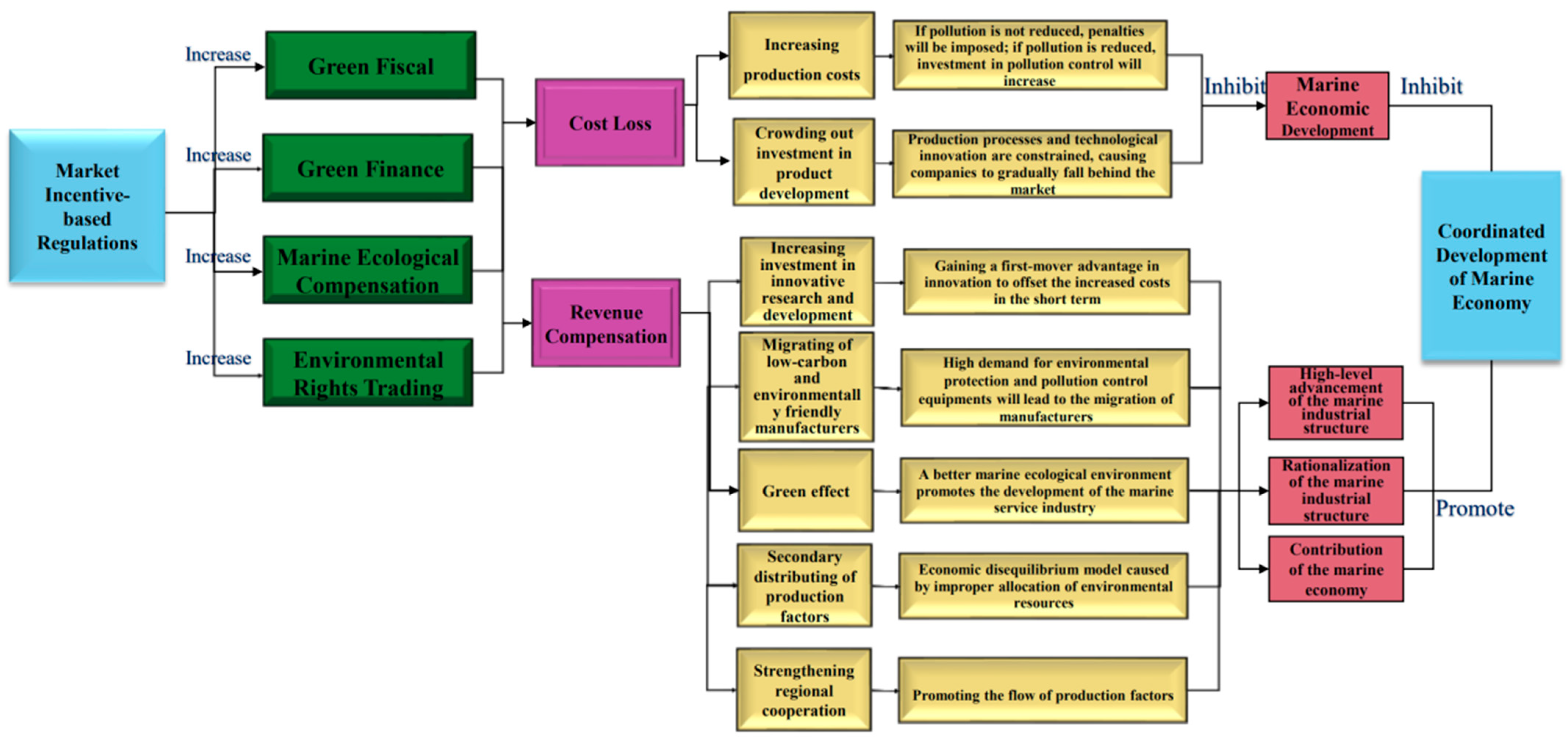

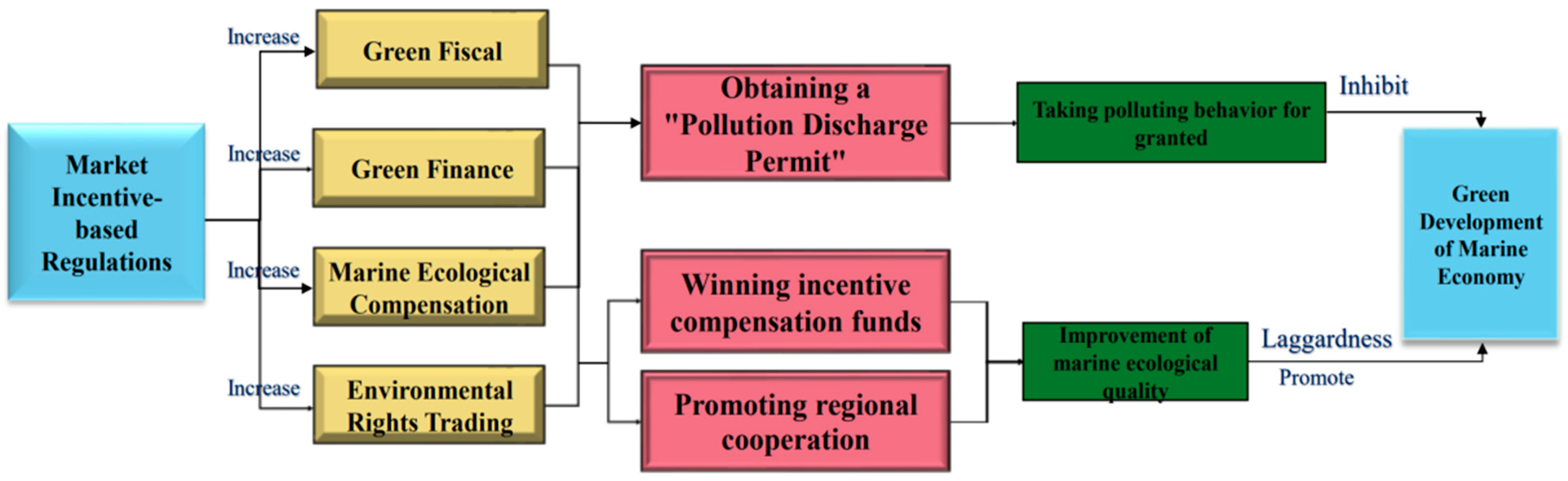

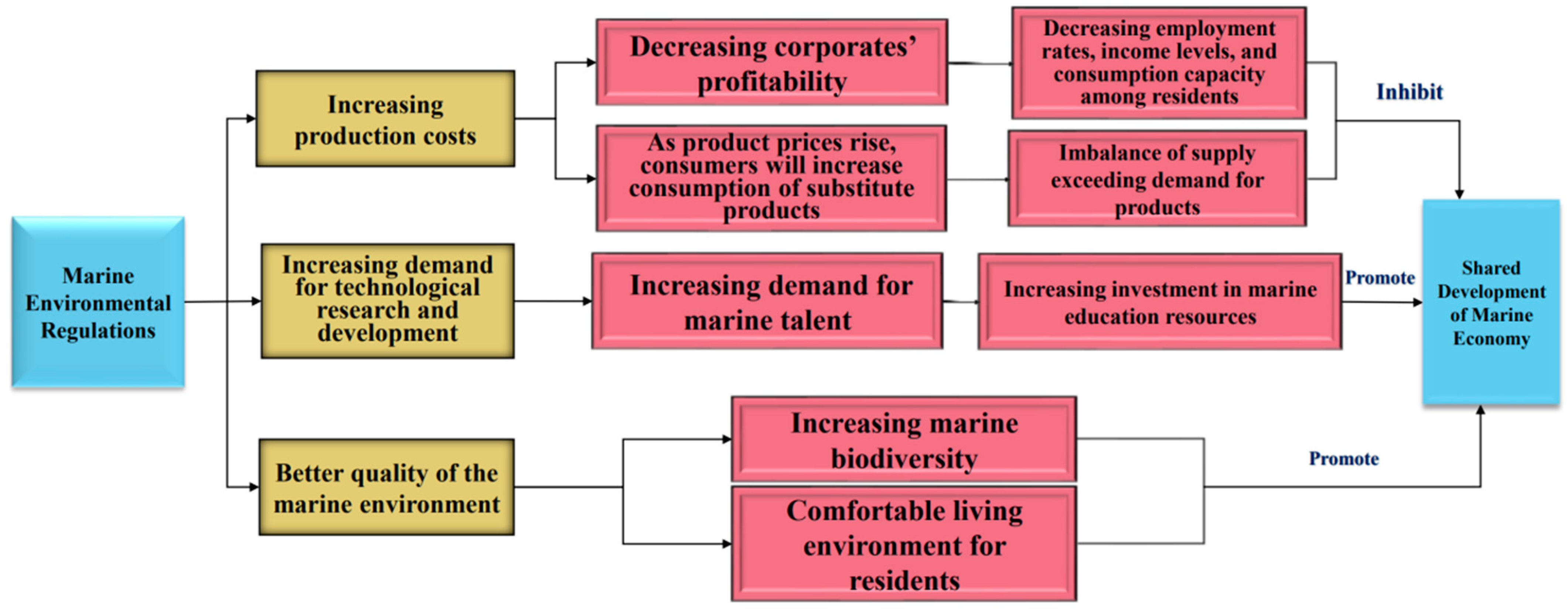

2.1. Market Incentive Regulations Mechanism

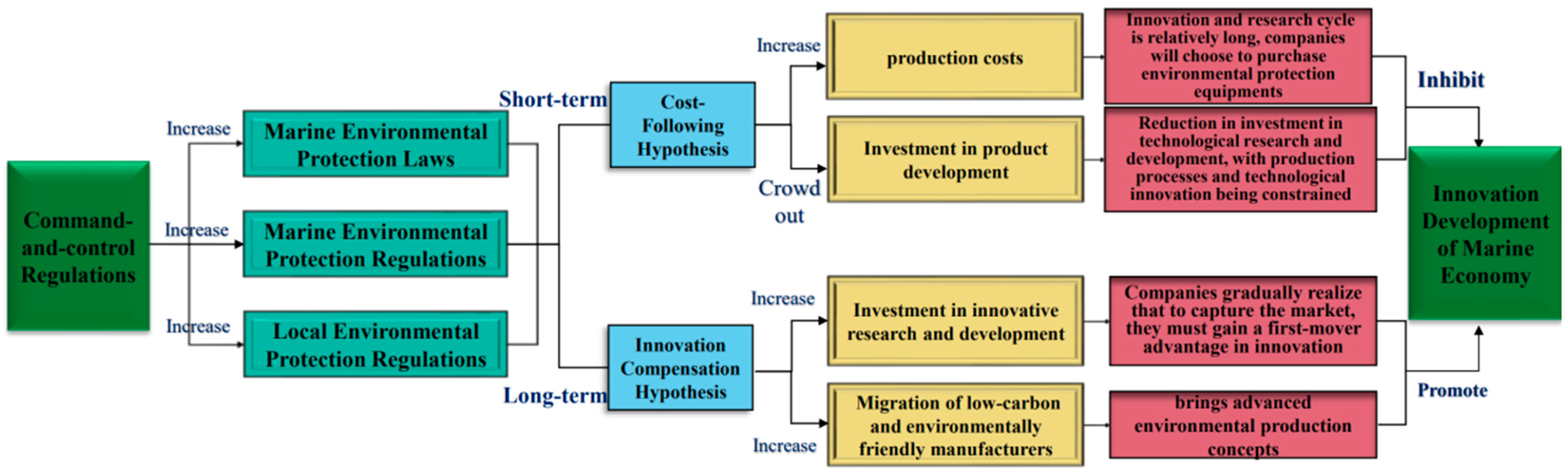

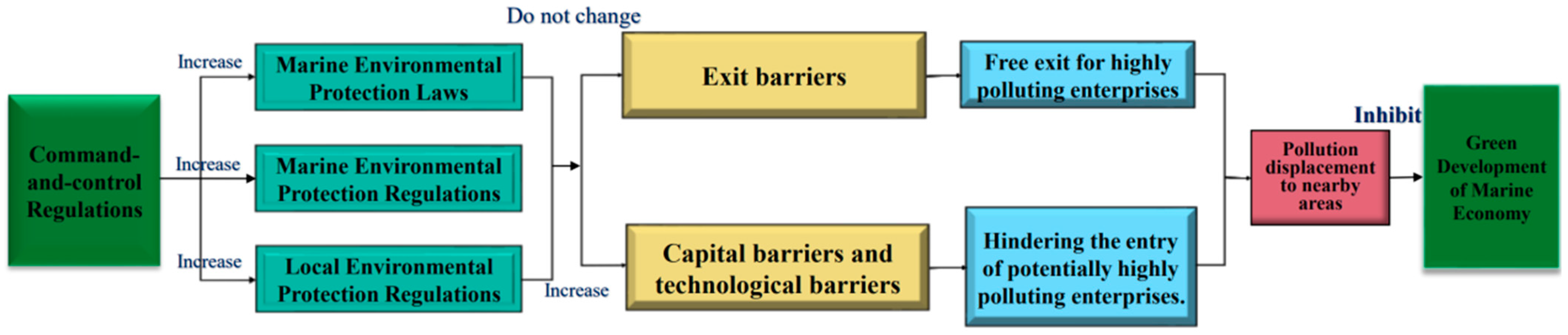

2.2. Command-and-Control Regulations Mechanism

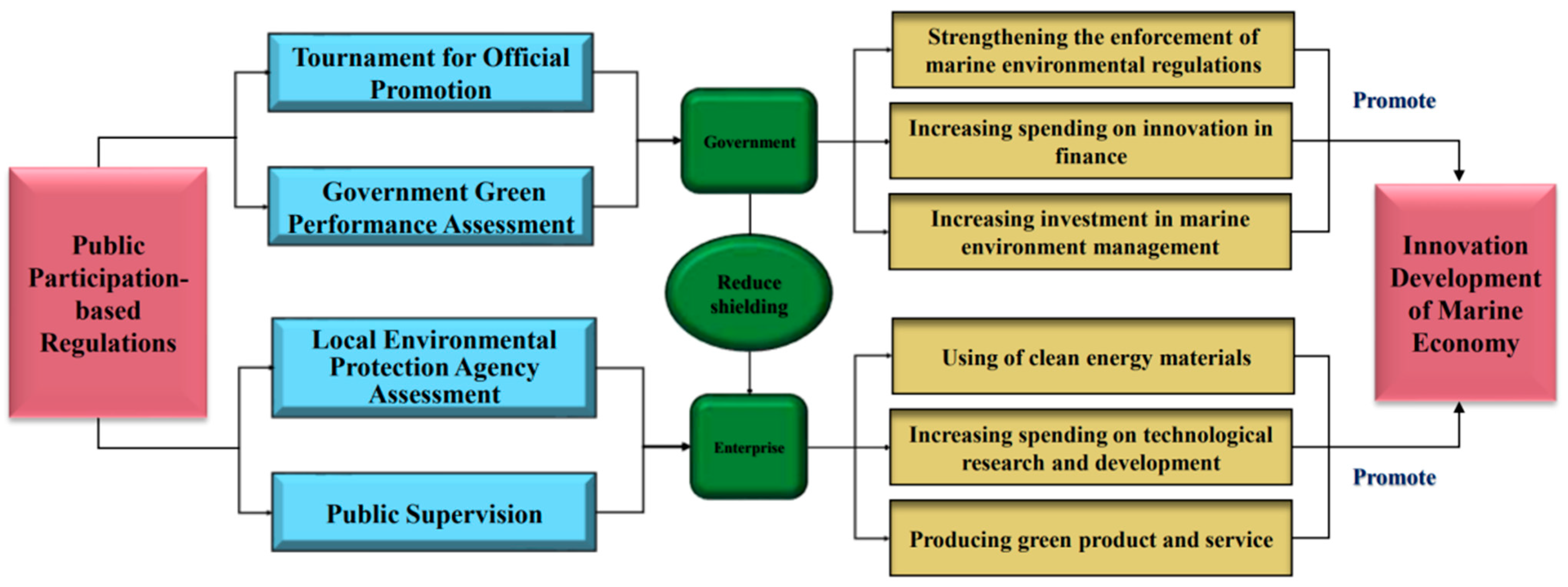

2.3. Public Participation Regulation Mechanisms

3. Research Design, Variable Description, and Data Sources

3.1. Marine Environmental Regulation Policies Selection

3.1.1. Selection of Market Incentive Regulation Policies

3.1.2. Selection of Command-and-Control Regulation Policies

3.1.3. Selection of Public Participation Regulation Policies

3.2. Research Method

3.2.1. Synthetic Control Method

3.2.2. Difference-in-Differences Approach

3.2.3. AHP-EW Combined-Weight Model

3.3. Data Sources and Indicator Selection

- (1)

- Dependent Variable: The score of SDGs-integrated development of the marine economy, calculated using the AHP-EW method.

- (2)

- Independent Variables: Dummy variables set according to the time and region of the implementation of marine environmental regulation policies, see in the previous text.

- (3)

- Control Variables: Using word frequency analysis to deeply explore the tendency opinions of scholars on the factors affecting the SDGs-integrated development of the marine economy in a total of twenty papers including those by Li Qiang and Xie Zhoutao (2023) [43]. Since the SDGs-integrated development of the marine economy is a comprehensive indicator, there are differences among scholars when constructing indicators. Therefore, the indicators already included in this study’s SDGs-integrated development of the marine economy are excluded in the word frequency analysis, and the related factors of marine environmental regulation are also excluded. The statistical information is presented in Table 3.

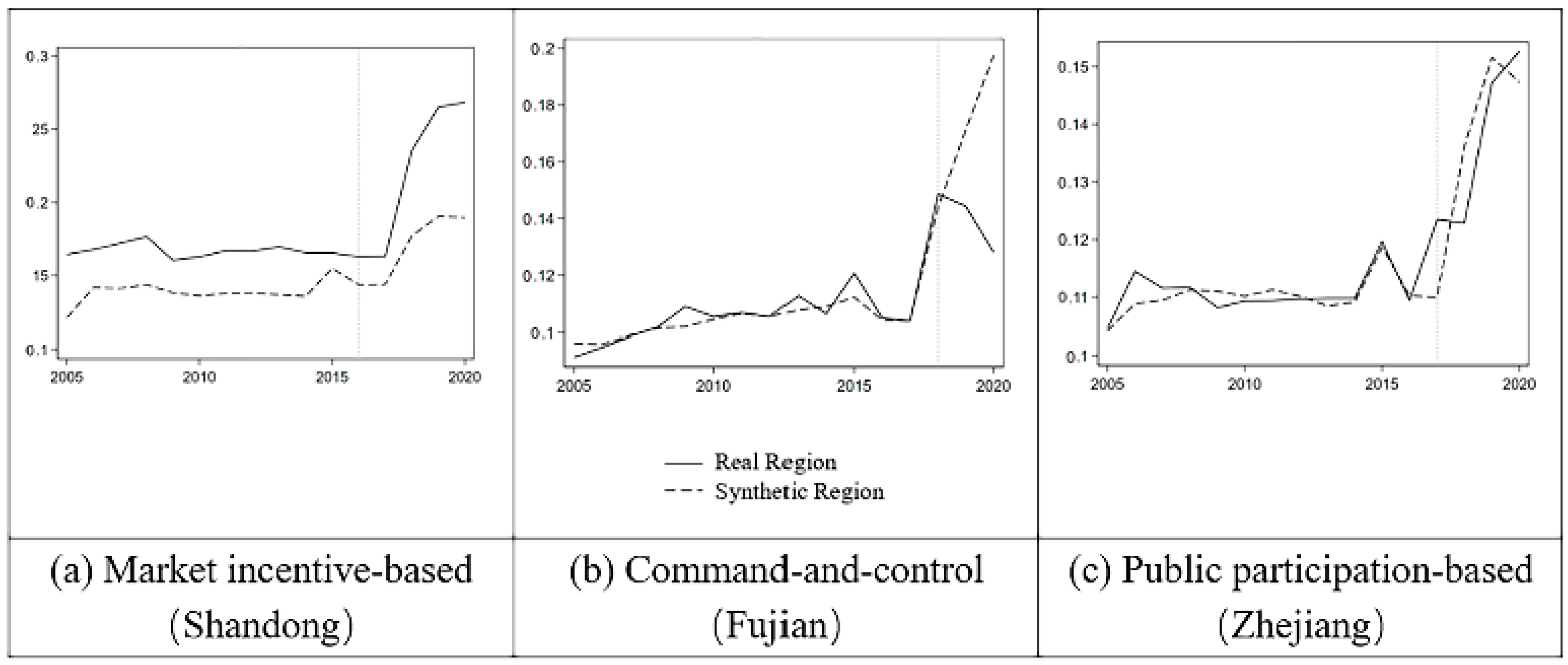

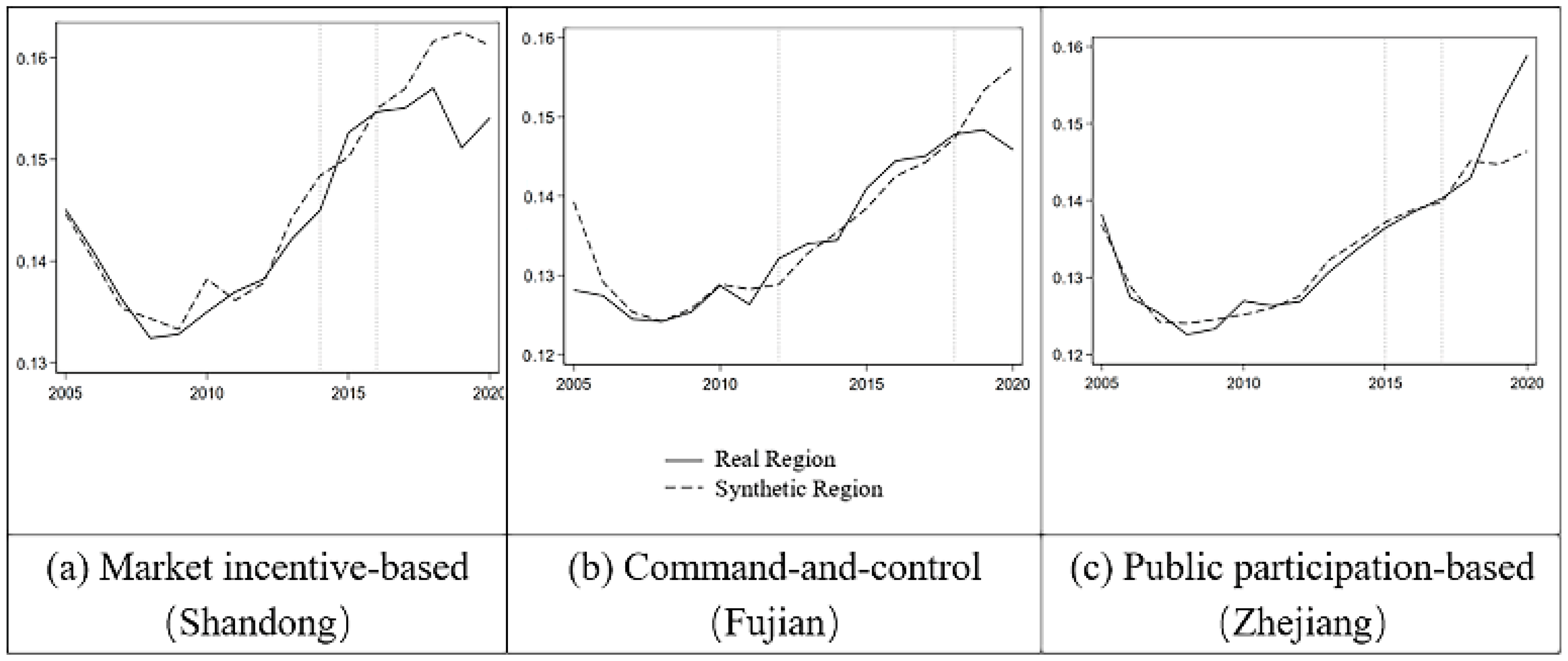

4. The Impact of Marine Environmental Regulation on the SDGs-Integrated Development of the Marine Economy

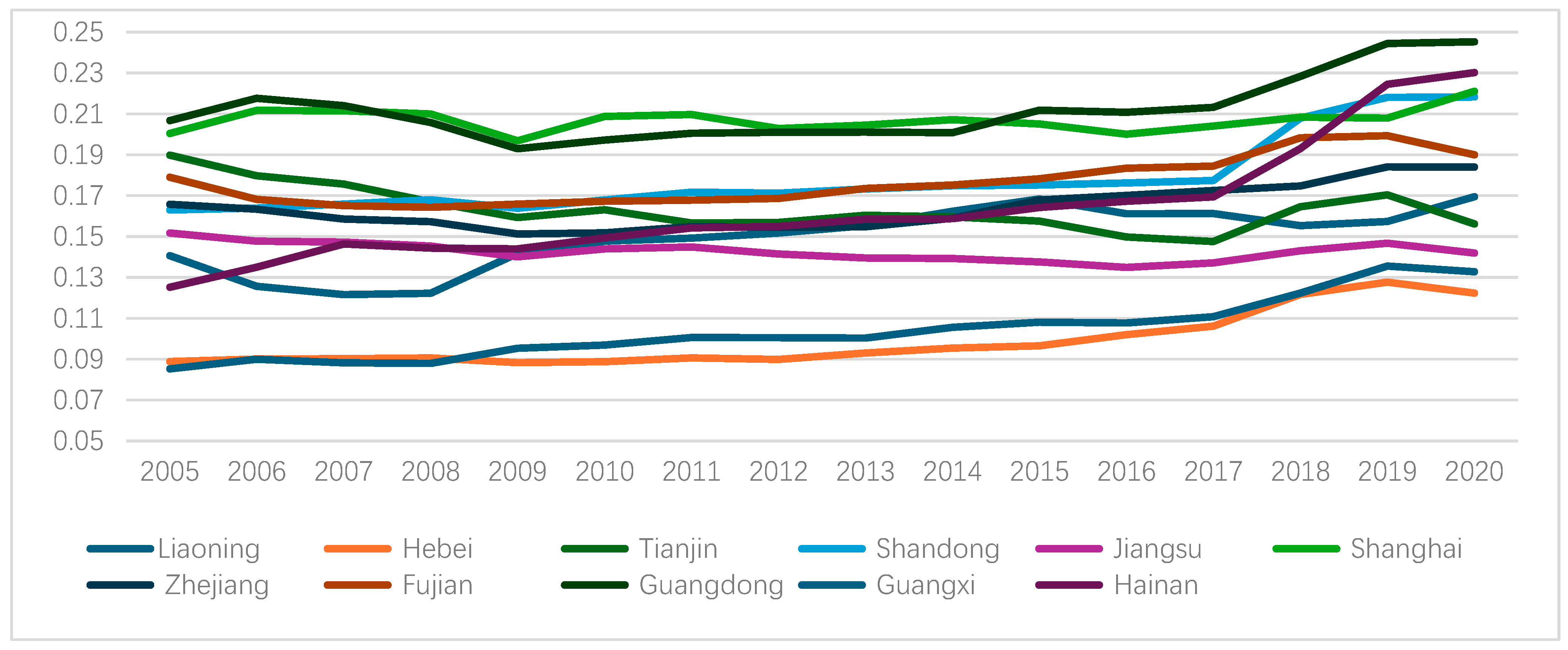

4.1. Comprehensive Evaluation of the SDGs-Integrated Development Level of the Marine Economy

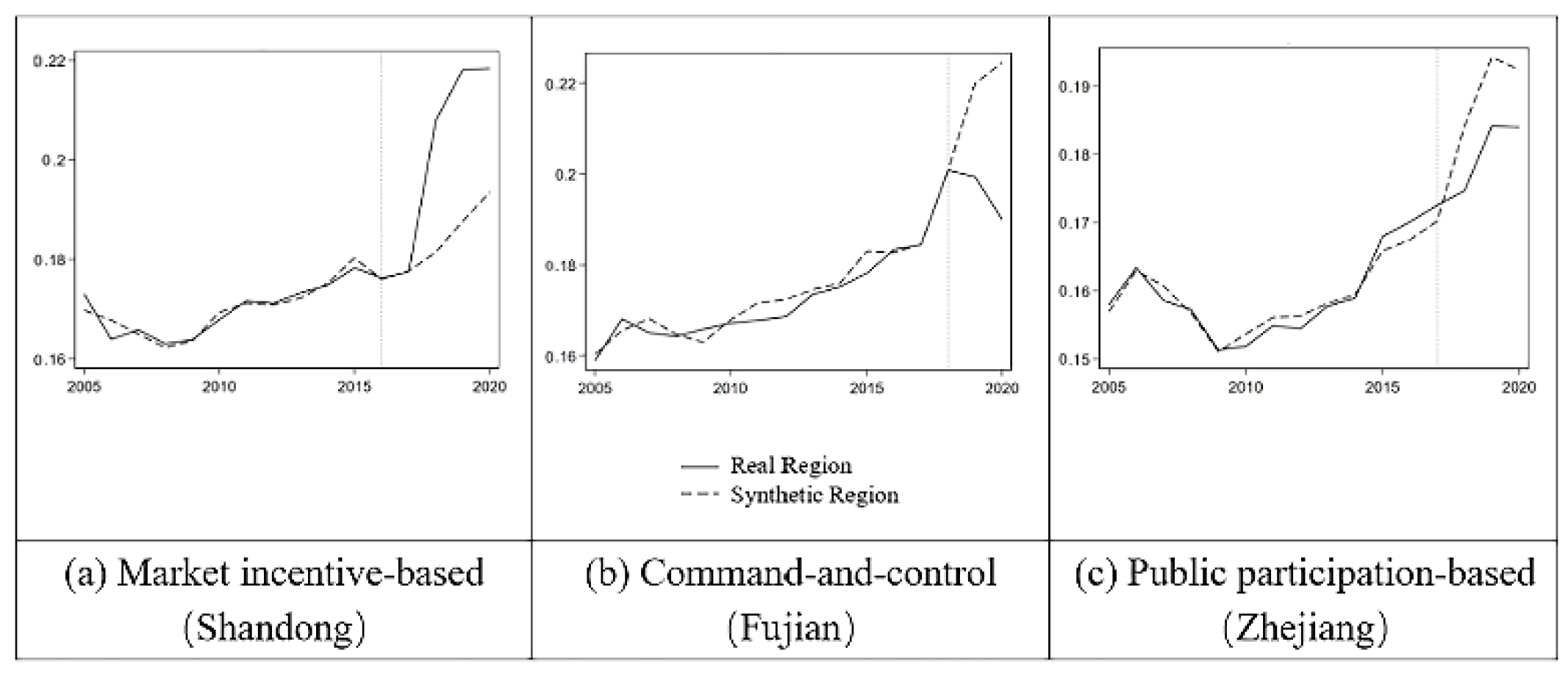

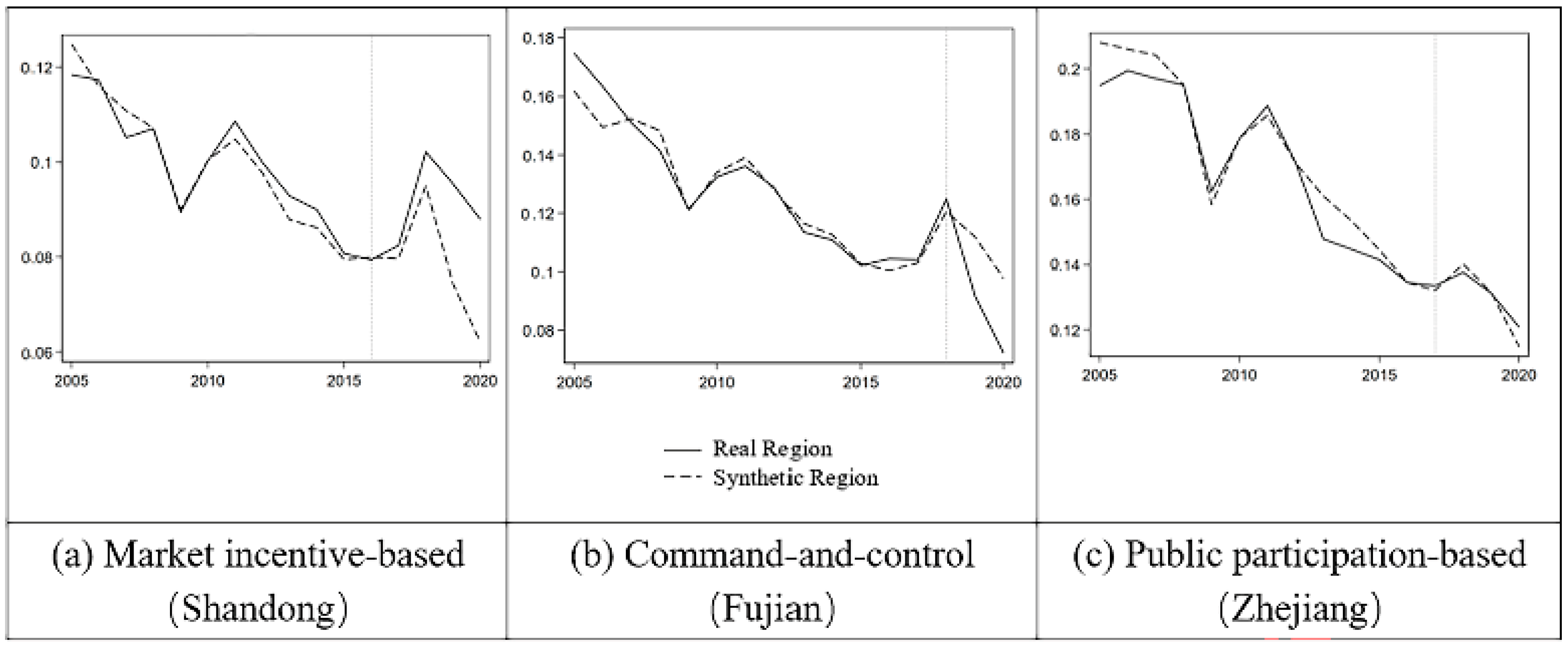

4.2. The Impact of Marine Environmental Regulation on the SDGs-Integrated Development of the Marine Economy

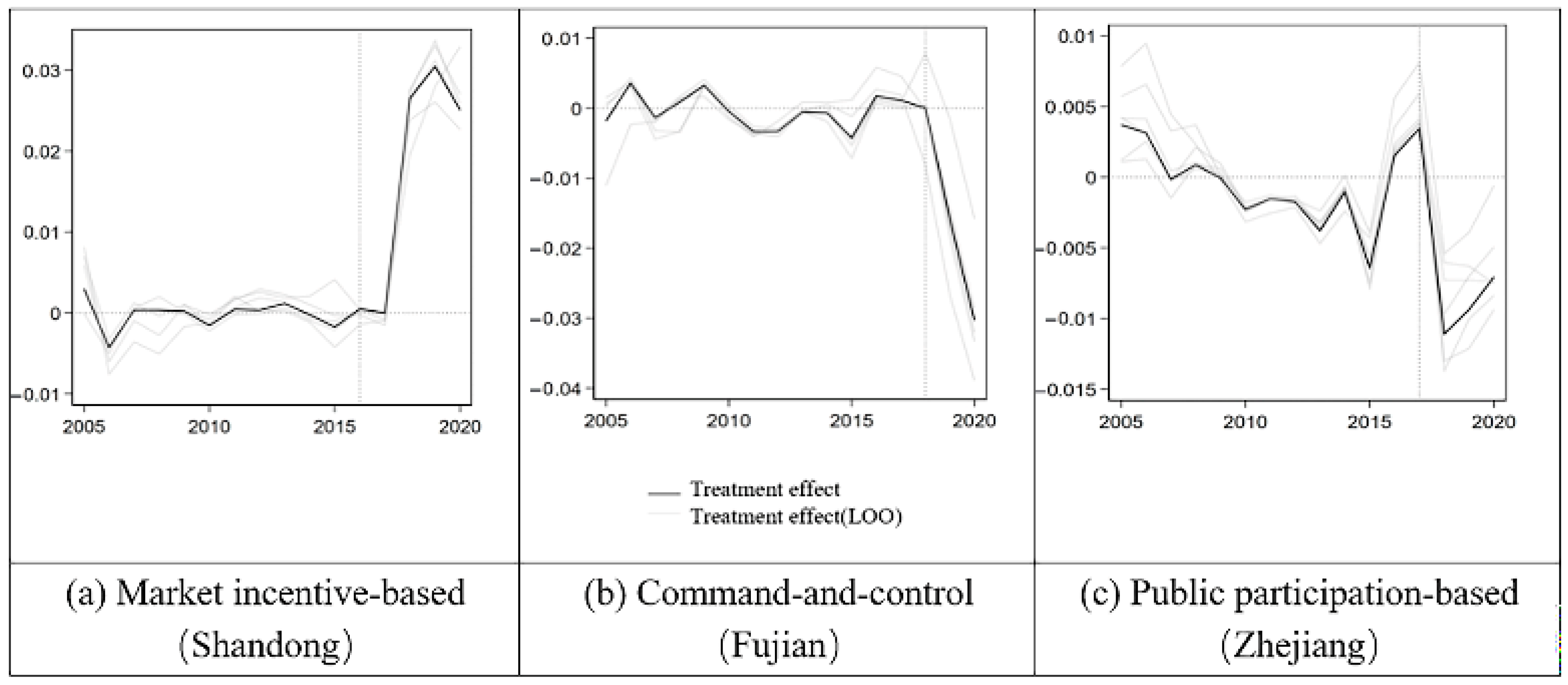

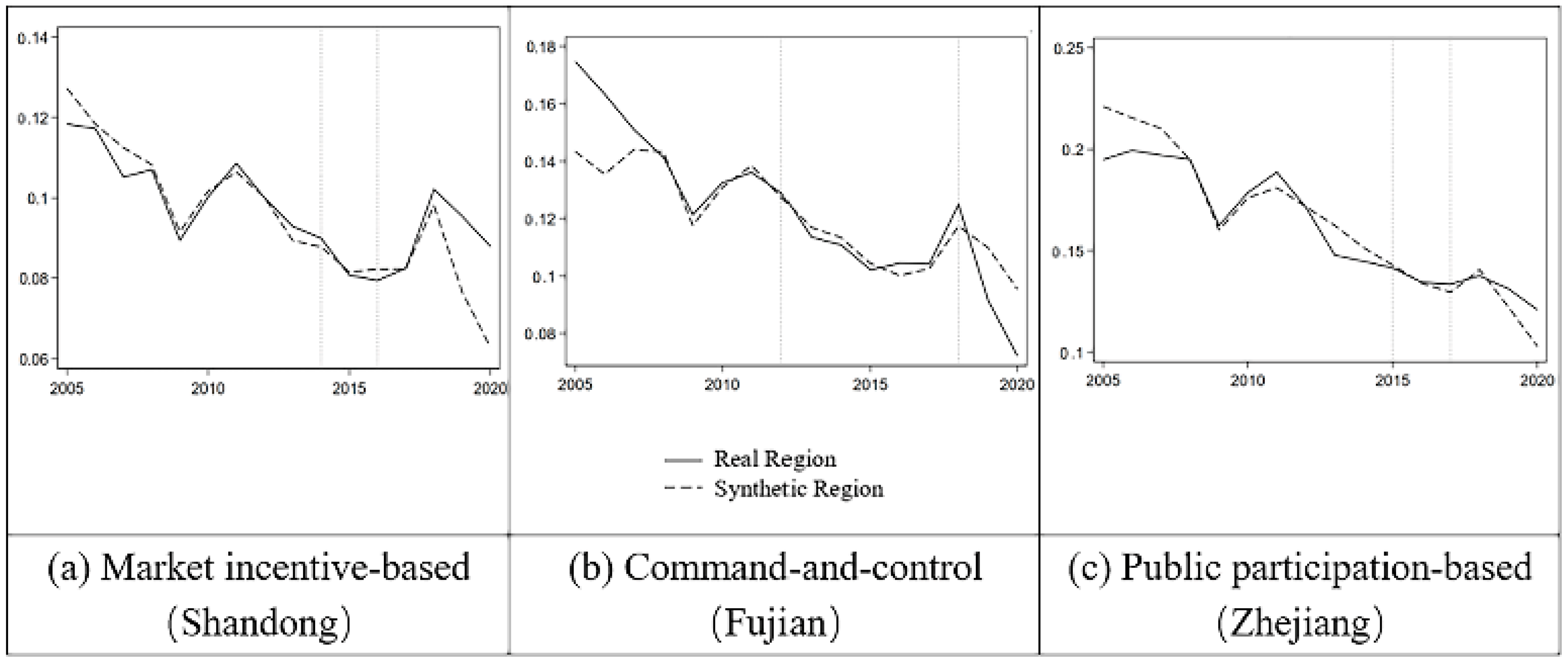

4.3. Validity Test

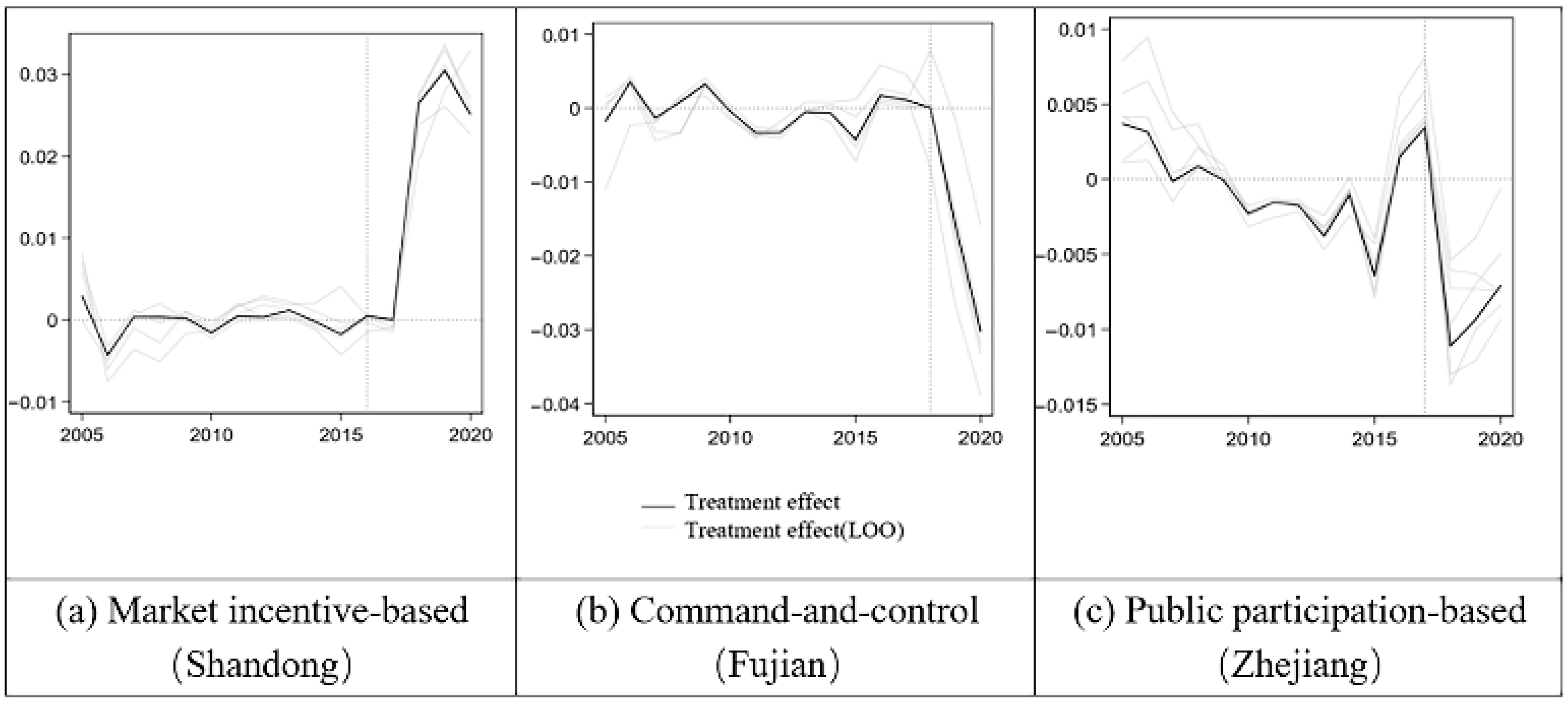

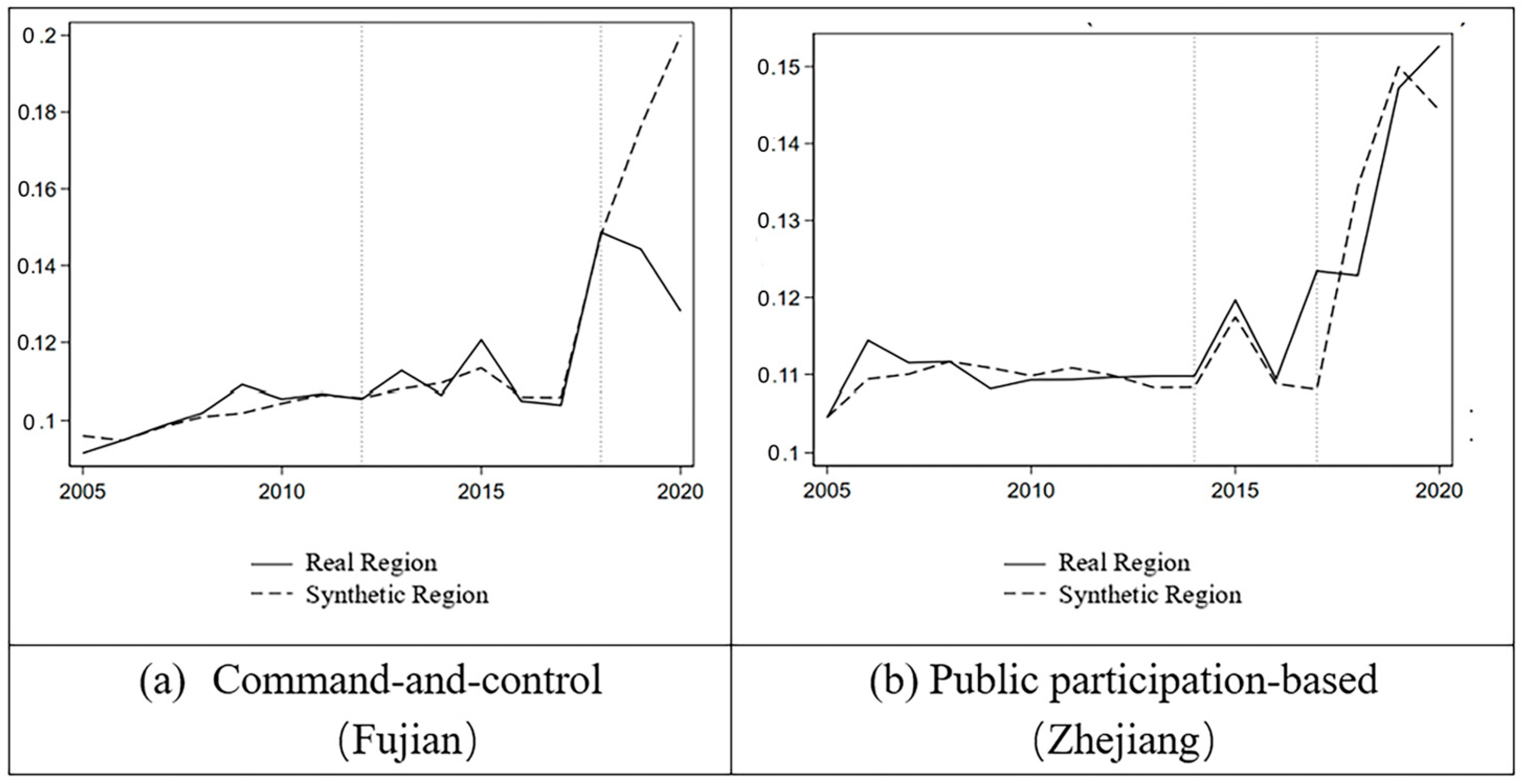

4.3.1. Permutation Test Method

4.3.2. Time Placebo Test

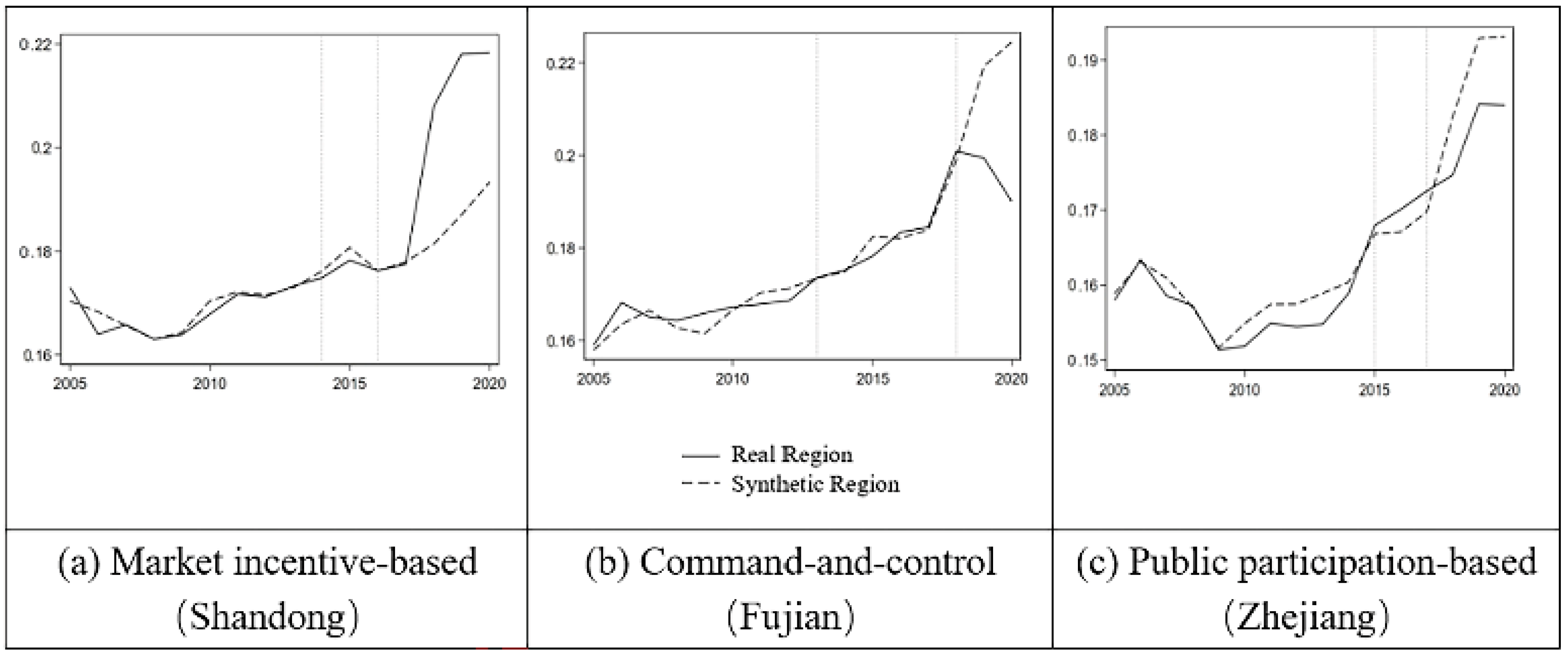

4.4. Robustness Test

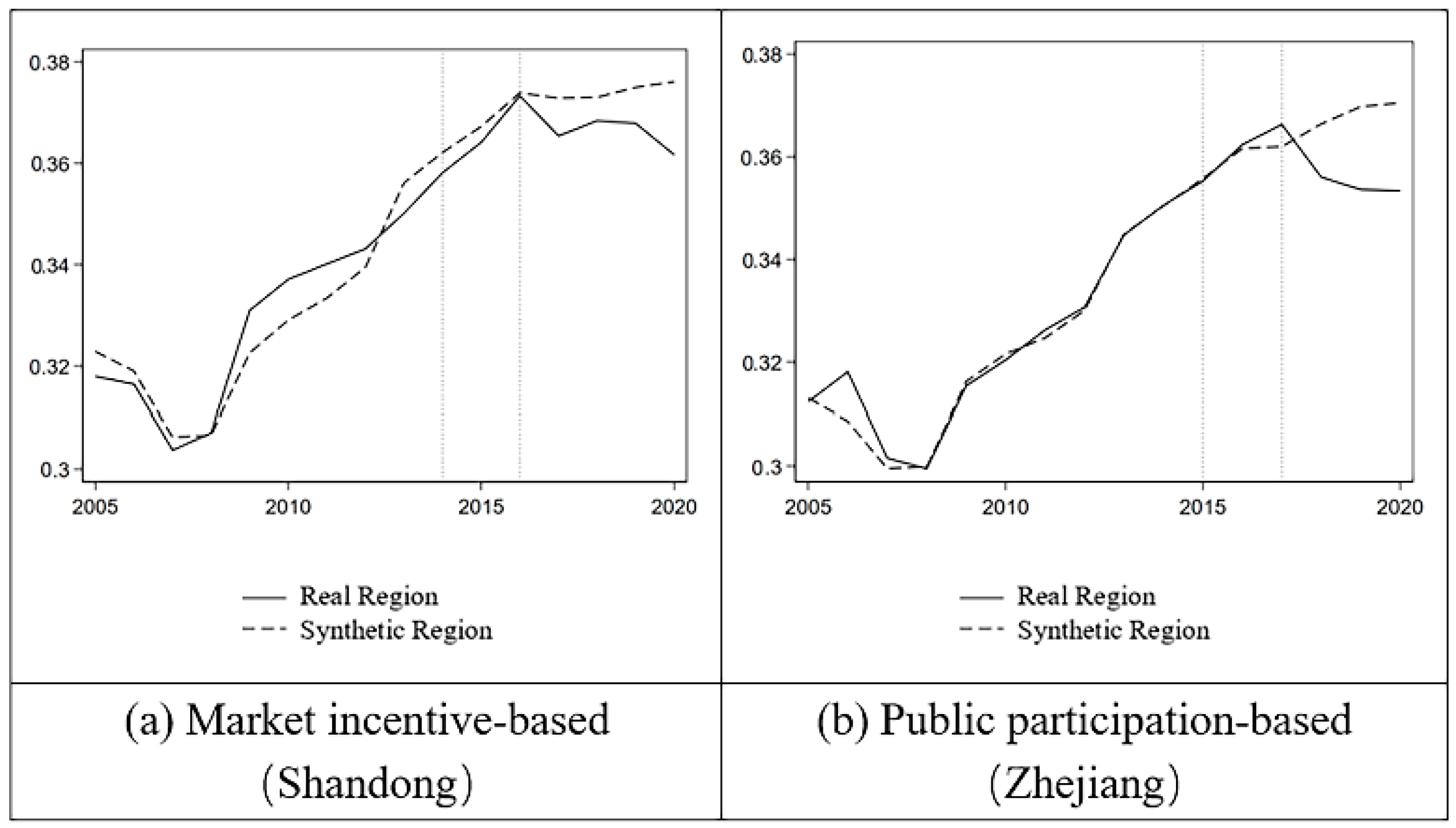

5. Further Analysis—The Impact of Marine Environmental Regulation on the Dimensions of SDGs-Integrated Development of the Marine Economy

5.1. Model Specification and Data Sources

- (1)

- Carefully examine the model’s assumptions and applicability: Firstly, we will recheck whether the assumptions of the two methods are met in the specific application scenarios. For example, is the “parallel trend” assumption of DID valid in the selected sample? Was the fitting quality of the SCM synthetic control group sufficient before the policy?

- (2)

- Deeply analyze the sources of differences: We will carefully analyze the potential reasons for the differences in the results, which might include the following: Are there any unobservable confounding factors affecting it? Does the difference in the scope of sample selection lead to bias? Does the policy effect itself have heterogeneity?

- (3)

- Report and discuss all findings: In the paper, we will present both the results of the SCM and DID analyses simultaneously and candidly discuss any existing inconsistencies. This discussion itself has significant value, as it can more comprehensively reveal the complexity of the policy effect and point the way for further research. The final conclusion will be reached based on the overall weighing and cautious interpretation of the results of the two methods, rather than simply choosing one.

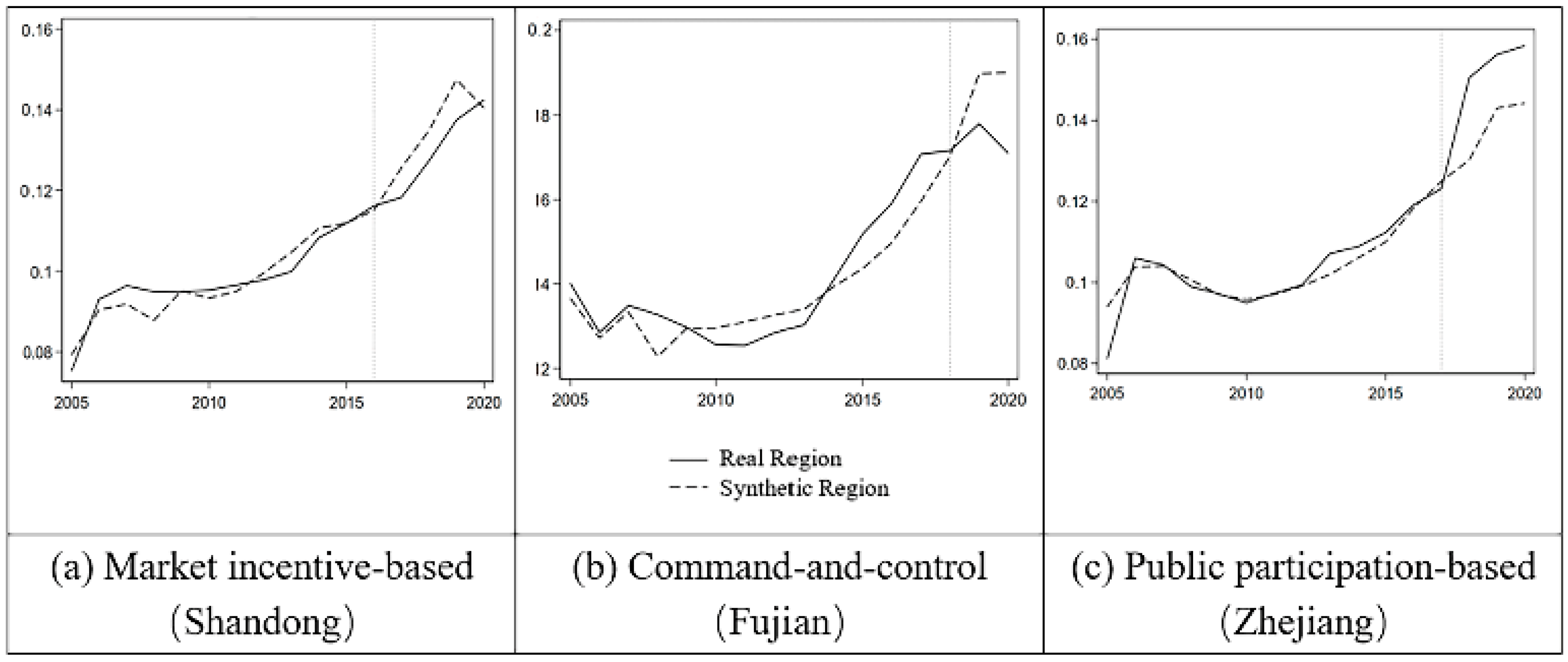

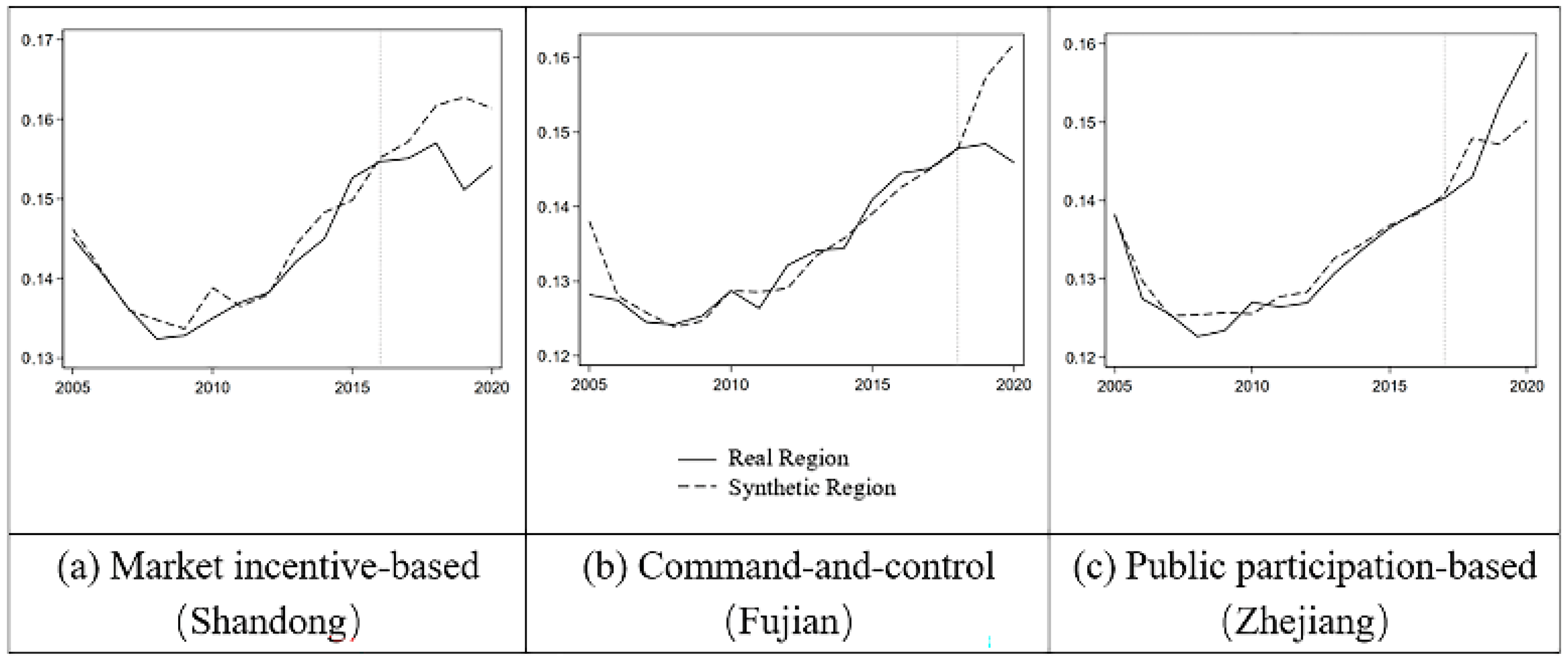

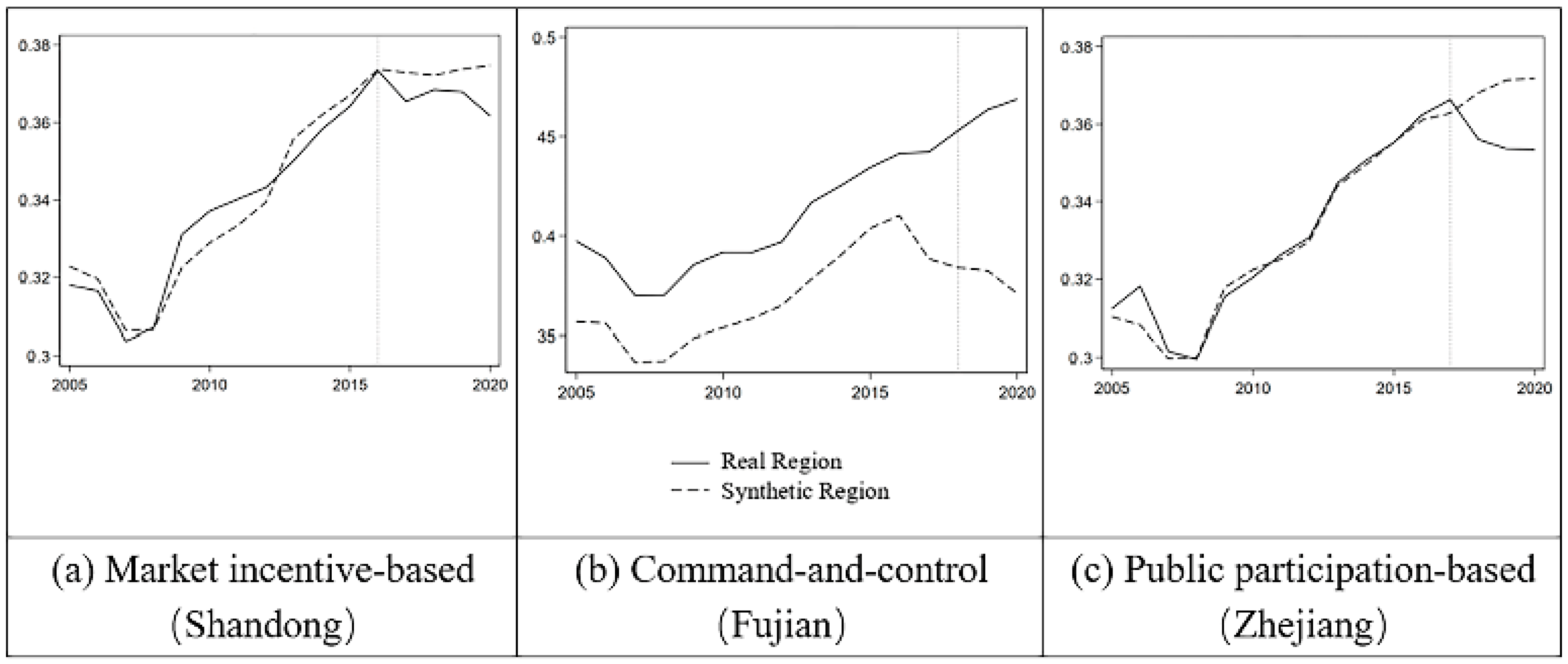

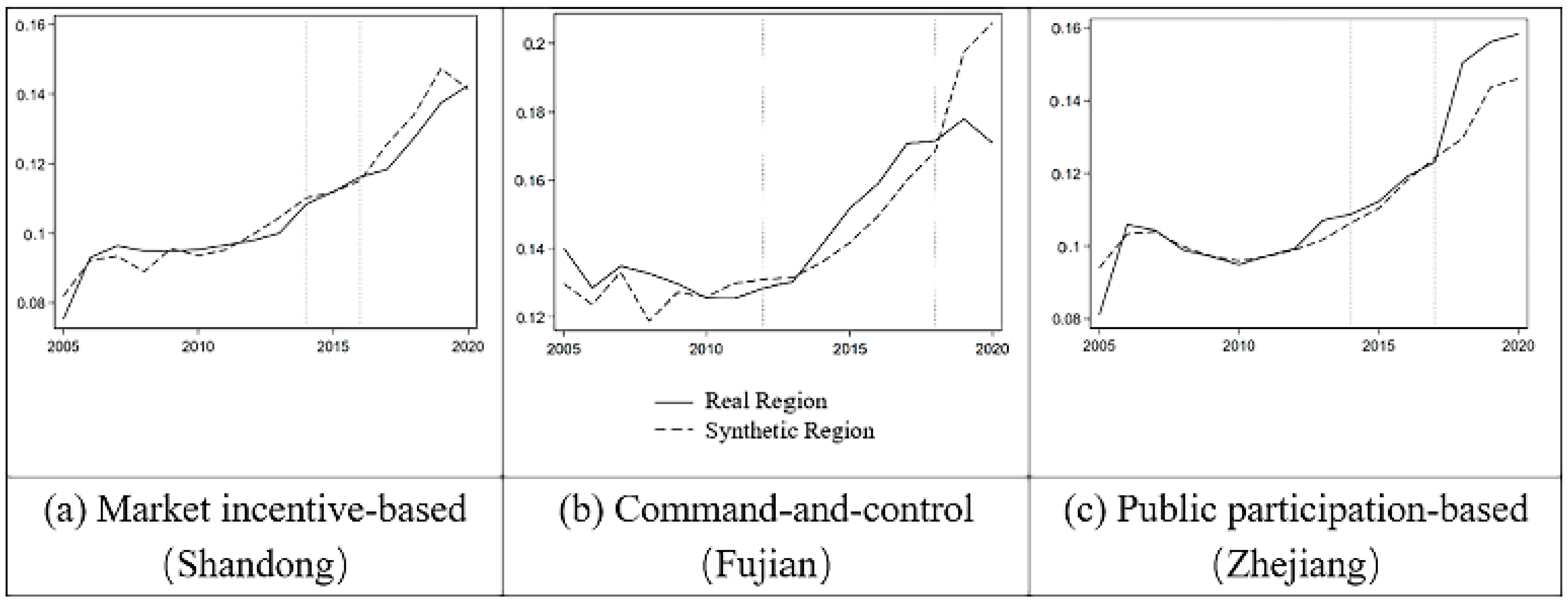

5.2. Results Analysis

5.3. Robustness Test

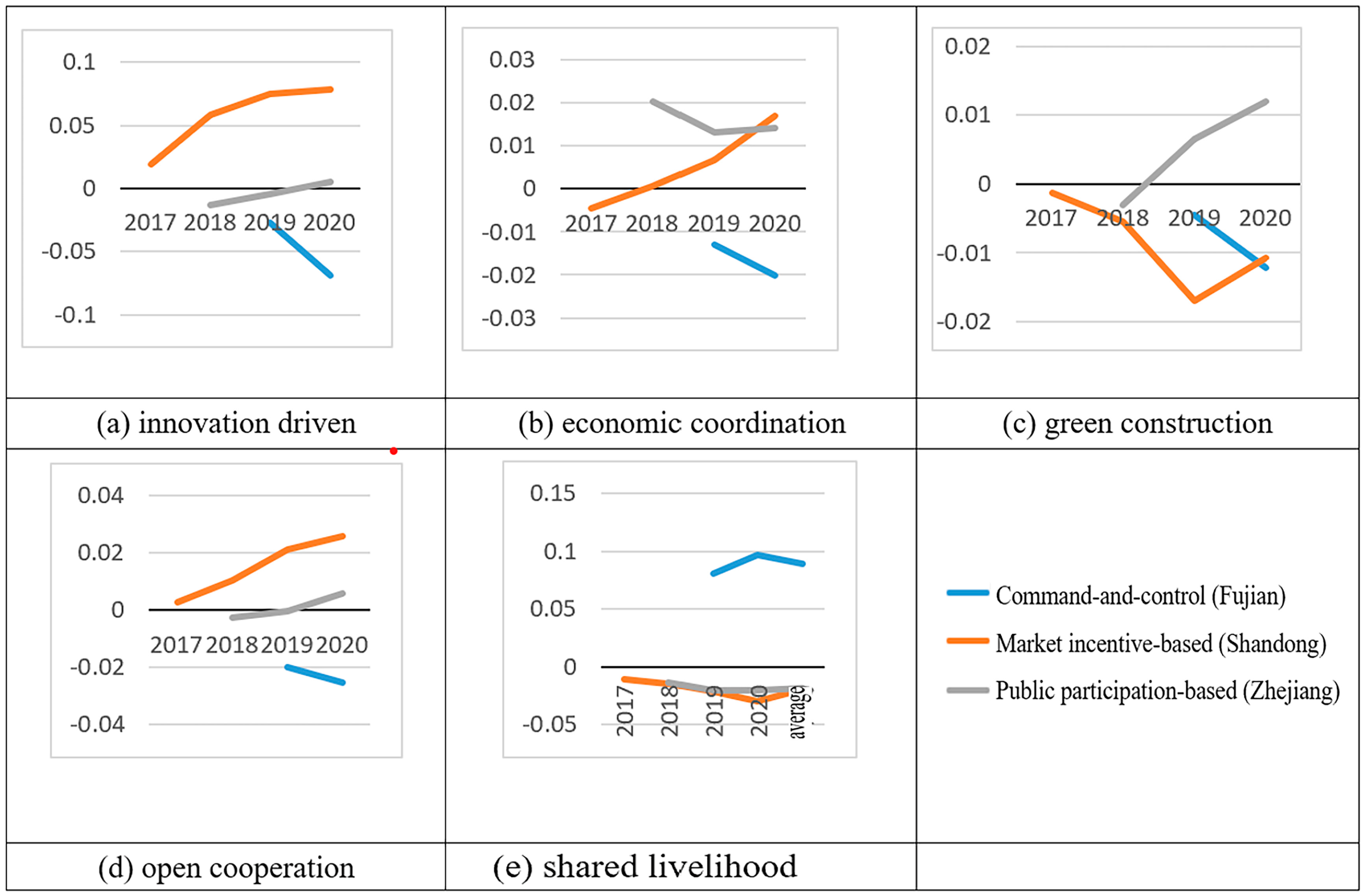

5.4. Comparative Analysis of the Impact of Marine Environmental Regulation on the Dimensions of SDGs-Integrated Development of the Marine Economy

- (1)

- The market incentive regulation generally has a promotional average impact on the SDGs-integrated development of the marine economy (0.0207), with the most significant promotion on the innovation-driven dimension (0.0578), followed by open cooperation (0.0151), while it has an inhibitory effect on the industrial coordination, green construction, and sharing of livelihoods dimensions.

- (2)

- The command-and-control regulation generally has an inhibitory average impact effect on the SDGs-integrated development of the marine economy (−0.0262), with a positive promotion effect only on the dimension of the sharing of livelihoods (0.0889), and a negative effect on the other four dimensions, with the strongest inhibitory effect on the innovation-driven dimension (−0.0481).

- (3)

- The public participation regulation generally has an inhibitory average impact effect on the SDGs-integrated development of the marine economy (−0.0096), with inhibitory effects on the innovation-driven (−0.0041) and sharing of livelihoods (−0.0179) dimensions, with the most significant inhibition on the innovation-driven dimension, while it has a promotional effect on the industrial coordination, green construction, and open cooperation dimensions.

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Suggestions

7.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- The empirical results of the synthetic control method show that market incentive regulation uniquely promotes SDGs-integrated marine economic development (avg. +0.0207 annually), whereas command-and-control and public participation measures inhibit it (avg. −0.0262 and −0.0096). The findings, robust across multiple statistical tests, validate both the theoretical framework and the applied methodology.

- (2)

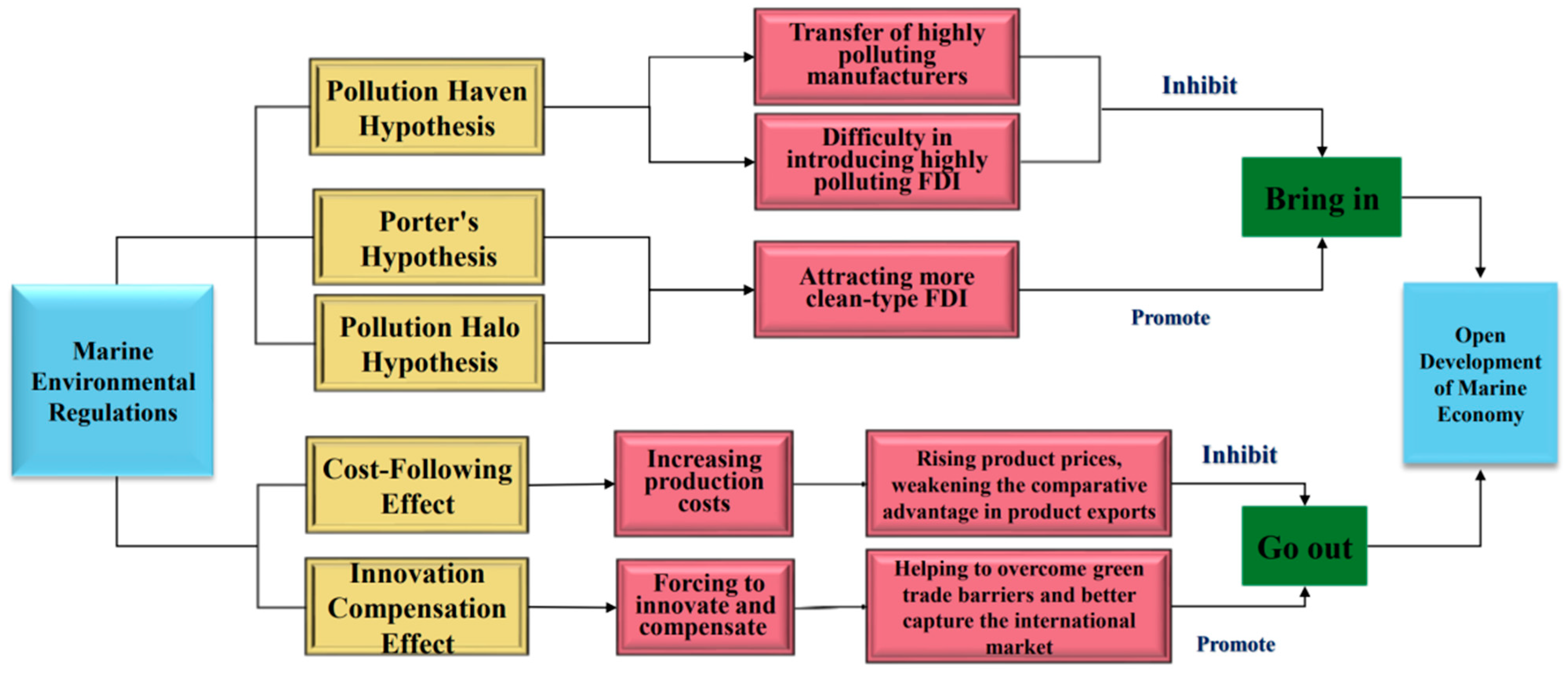

- Further analysis using the synthetic control method and the difference-in-differences method shows the differences in the impact of heterogeneous marine environmental regulation policies on the five dimensions of SDGs-integrated development of the marine economy: ① Innovation-driven effect: The impact of command-and-control and market incentive regulations on innovation is determined by the interplay between their cost effect and innovation compensation effect. In contrast, public participation regulation imposes only a soft constraint without direct production impact. Market incentive regulation demonstrates superior effectiveness in stimulating innovation, thereby supporting the narrow Porter hypothesis and extending its applicability to the marine context. ② Industrial coordination effect: Regarding industrial coordination, public participation regulation demonstrates the strongest promotional effect, whereas both market incentive and command-and-control types exhibit inhibitory effects, primarily by influencing the rationalization of the industrial structure. ③ Green construction effects: Marine environmental regulation prompts the participation of the government, market, and public in governance together, but the effects vary. The research results show that public participation marine environmental regulation is different from the spontaneous and confrontational “nepotism movement”. It exerts pressure on local governments and polluting enterprises through information disclosure and public opinion supervision, reducing local protectionism and the shielding of pollution behaviors. At the same time, through public education and publicity, it enhances public environmental awareness, changes consumption preferences, and forces enterprises to undergo green transformation from the demand side. As “supervisors” scattered throughout various places, the public can make up for the deficiency of government regulatory power and increase the probability of discovering environmental violations. This government-led, orderly public participation has had a slight promoting effect on green construction in the long term; completely spontaneous and disorderly public participation may indeed hinder ecological improvement due to “nepotism”, and then top-down measures need to be taken. ④ Open cooperation effect: The impact of marine environmental regulation on open cooperation is driven by cost, pollution havens, race-to-the-bottom effects on “bringing in,” and cost and innovation compensation effects on “going out.” Experimentally, market incentive regulation most strongly promotes openness with sustained growth, public participation follows, while command-and-control regulation exerts an inhibitory effect. ⑤ The sharing of livelihoods effect: In its impact on the sharing of livelihoods—reflected in employment, quality of life, and education—command-and-control regulation shows a significant promotional effect, whereas both market incentive and public participation regulations exhibit weak inhibition.

7.2. Suggestions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park, M.H.; Lee, W.J. Marine oil spill analyses based on Korea Coast Guard big data from 2017 to 2022 and application of data-driven Bayesian Network. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 436, 140630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Linde, C. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. America’s Green Strategy. In Business and the Environment: A Reader; Welford, R., Starkey, R., Eds.; Taylor and Frensis: Washington, DC, USA; Earthscan Publication Limited: London, UK, 1996; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Denison, E.F. Accounting for slower economic growth: The United States in the 1970’s. Econ. J. 1981, 91, 1044–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintrakarn, P. Environmental regulation and US states’ technical inefficiency. Econ. Lett. 2008, 100, 363–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Zhang, Y. Environmental Regulation, Industrial Structure Adjustment, and High-Quality Economic Development—An Analysis Based on the PVAR Model of 11 Provinces and Cities in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Stat. Inf. Forum 2021, 36, 21–29. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Su, X.; Yan, B. Study on the Impact of Marine Environmental Regulation on the High-Quality Development of the Marine Economy—An Empirical Analysis Based on Spatial Econometric Model. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 38, 139–147. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.; Jin, Y. Research on the Theoretical Construction and Governance Mechanism of Marine Environmental Regulation. Pac. J. 2020, 28, 90–99. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jouffray, J.-B.; Blasiak, R.; Norström, A.V.; Österblom, H.; Nyström, M. The blue acceleration: The trajectory of human expansion into the ocean. One Earth 2020, 2, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Iraldo, F.; Frey, M. The Effect of Environmental Regulation on Firms’ Competitive Performance: The Case of the Building Construction Sector in Some EU Regions. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 2136–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, H.; Ting, W.; Jing, H. Does Environmental Regulation Indirect Affect International Competitiveness—Based on the Dual Perspectives of Technological Innovation and Capital Investment. J. Int. Trade 2017, 11, 97–107. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, K.; Oates, W.E.; Portney, P.R. Tightening environmental standards: The benefit-cost or the no-cost paradigm? J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C. The Duality of Environmental Regulation: Hindering or Promoting Technological Progress—Evidence from Wuhan Urban Circle. Prog. Sci. Technol. Policy 2017, 34, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Xiao, X. Environmental Regulation, Enterprise Profitability and Production Efficiency: A Re-examination Based on Porter’s Hypothesis. Financ. Trade Econ. 2015, 32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Wei, X. Market Incentive-Type Environmental Regulation, Government Subsidies and Enterprise Performance. Financ. Res. 2022, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Brink, D.V.M.; Woltjer, J. Market-based instruments for the governance of coastal and marine ecosystem services: An analysis based on the Chinese case. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 23, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.; Jin, G. Did environmental regulations lead to the relocation of pollution to nearby areas? Econ. Res. 2017, 52, 44–59. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S.; Youguo, Z. Environmental Regulation, Industrial Transfer and Regional Coordinated Development. Econ. Dyn. 2021, 68–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, W.B.; Shimshack, J.P. The effectiveness of environmental monitoring and enforcement: A review of the empirical evidence. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2011, 5, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jian, Y. The Impact of Market-Incentive Environmental Regulations on China’s Carbon Emission Reduction: Also Discussing the Moderating Effect and Threshold Effect. J. Resour. Dev. Mark. 2025, 41, 822–831. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, M.; Burdon, D.; Atkins, J.P.; Borja, A.; Cormier, R.; de Jonge, V.N.; Turner, R.K. “And DPSIR begat DAPSI(W)R(M)!”—A unifying framework for marine environmental management. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 118, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wan, G. The Impact of Environmental Regulation on the Entry of Foreign Capital. China Ind. Econ. 2021, 98–116. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gyu, M.B.; Chen, Y.W.; Na, L. Revisiting the Relationship Between the Strength of Environmental Regulation and Foreign Direct Investment. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 899918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, T.; Rui, X. The Social Welfare Effect of Environmental Regulation: Theoretical and Empirical Analysis from the Perspective of Public Perception. Stat. Res. 2022, 39, 125–137. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Lü, X. Research on the Interactive Relationship between the Professional Structure of Higher Education and the Industrial Structure—Taking Marine Economy as an Example. China High. Educ. 2021, 59–61. [Google Scholar]

- Liquete, C.; Piroddi, C.; Drakou, E.G.; Gurney, L.; Katsanevakis, S.; Charef, A.; Egoh, B. Current status and future prospects for the assessment of marine and coastal ecosystem services: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2017, 8, e67737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, G.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Y. Research on the Policy Formulation for Marine Ecological Environment Protection in the Development of Methane Hydrate—From the Perspective of Transaction Cost Theory. J. Xiangtan Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 44, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Chinese-style Decentralization and the Bias of Fiscal Expenditure Structure: The Cost of Competing for Growth. Manag. World 2007, 4–12+22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lu, Y.; Guo, L.; Yu, T.S. The intensity of environmental regulation and technological progress of production. Econ. Res. J. 2011, 2, 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- He, G.; Wang, S.; Zhang, B. Watering Down Environmental Regulation in China. Q. J. Econ. 2020, 135, 2135–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Li, M. Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity and Synergy of Carbon Emission Reduction Effects of Formal and Informal Environmental Regulations: An Empirical Analysis of 14 Prefectures and Cities in Xinjiang from 2007 to 2017. West. Forum. 2020, 30, 84–100. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guan, X.; Chai, C.; Zhao, C. Can Pressure of Local Government Performance Appraisal Improve Corporate Green Innovation Performance?—Empirical Evidence from Dual Mediation of Environmental Regulation and Environmental Subsidies. Res. Econ. Manag. 2023, 44, 113–131. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Shi, H. Research on the Impact of Different Types of Environmental Regulations on Industrial Structure Upgrading. China Price 2022, 47–49. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H.; Z, Y. Environmental Enforcement Supervision and Enterprise Environmental Performance: Empirical Evidence from Natural Experiments Based on Environmental Inspection Interviews. Nankai Manag. Rev. 2017, 20, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Shandong Provincial Finance Department; Shandong Provincial Department of Ocean and Fisheries. Notice on the Issuance of the “Shandong Province Marine Ecological Compensation Management Measures”. Shandong Prov. People’s Gov. Gaz. 2016, 88–90. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R.; Jiang, X. Progress in the Study of Marine Ecological Compensation Abroad (1960–2018). J. Ocean. Univ. China (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 4–93. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Regulations on the Protection and Utilization of the Coastal Zone in Fujian Province. Available online: https://sthjt.fujian.gov.cn/zwgk/flfg/201805/t20180508_2243679.htm (accessed on 10 October 2025). (In Chinese)

- Notice from the General Office of Zhejiang Provincial People’s Government on the Issuance of the Implementation Plan for the Creation of Zhejiang Marine Ecological Construction Demonstration Zone. Available online: https://www.doc88.com/p-54687158282885.html (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Chinese).

- Zhi, S.; Di, H. Is Inflation Targeting Effective?—New Evidence from the Synthetic Control Method. Econ. Res. 2015, 50, 74–88. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Abadie, A.; Diamond, A.; Hainmueller, J. Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: Estimating the effect of California’ s tobacco control program. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2010, 105, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yuan, F.; Li, X. Research on the Construction and Application of the Evaluation Index System for High-Quality Development of China’s Marine Economy—From the Perspective of the Five Major Development Concepts. Enterp. Econ. 2019, 38, 122–130. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, R.; Yin, W.; Han, L. Evaluation and Typological Division of High-Quality Development Level of Regional Marine Economy in China. Stat. Decis.-Mak. 2023, 39, 103–108. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Xie, Z. The Impact of Environmental Information Disclosure on High-Quality Economic Development—Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt. J. Manag. Sci. 2023, 36, 1–21. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, H. Study on the Impact of Fiscal and Tax Policies on Economic Growth. China Collect. Econ. 2024, 16, 25–28. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Tian, F.; Zhou, T. Study on the Impact of Green Finance on High-Quality Economic Development. J. Chongqing Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 28, 1–13. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y. Influencing Factors of China’s Marine Economic Development—An Empirical Study Based on Panel Data of Coastal Provinces and Cities. Resour. Ind. 2011, 13, 95–99. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, X. Spatial Relationship Analysis between Population Density and Economic Development. Anhui Archit. 2023, 30, 33–34+90. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Wang, Z. Can the Construction of Transportation Infrastructure Promote the Convergence of High-Quality Development in the Yangtze River Economic Belt? J. Soochow Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 44, 31–44. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Our Dimensions | Corresponding SDGs and Connotations |

|---|---|

| Innovation-Driven Development | Goal 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure (Promoting Technological Innovation and Sustainable Industrialization) |

| Industrial Coordination | Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth (Coordinating Inclusive, Sustainable Economic Structures) |

| Green Construction | Goals 11/13/15: Sustainable Cities/Climate Action/Terrestrial Ecosystems (Green Low-Carbon Development) |

| Open Cooperation | Goal 17: Global Partnerships (Achieving Development Goals through International Cooperation) |

| Sharing of Livelihoods | Goals 1/2/3/4: No Poverty/Zero Hunger/Good Well-Being/Quality Education/Health (Universal Access and Shared Benefits) |

| Goal Layer | Criterion Layer | Sub-Criterion | Element Layer | Indicator Attribute | Combined Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDGs-integrated Development of the Marine Economy | Innovation-Driven Development 0.345 | Input of Innovation | X1 Number of Marine Science and Technology R&D Personnel (people) | + | 0.127 |

| X2 Intensity of Scientific Research Funding (the ratio of internal expenditure on research and development (R&D) to gross domestic product (%)) | + | 0.111 | |||

| Output of Innovation | X3 Number of Marine Scientific Research Papers Published (articles) | + | 0.281 | ||

| X4 Number of Maritime Patent Applications/Total Number of Domestic Patent Applications (%) | + | 0.175 | |||

| Main Body of Innovation | X5 Proportion of Regional Marine Science and Technology Institutions to the National Total (%) | + | 0.196 | ||

| X6 Number of Marine Science and Technology Projects (items) | + | 0.111 | |||

| Industrial Coordination 0.188 | Industrial Structure | X7 Advanced Marine Industry Structure Ratio (%) (GDP of marine tertiary industry/GDP of marine economy) | + | 0.125 | |

| X8 Rational Marine Industry Structure Ratio (%) (GDP of marine tertiary industry/GDP of marine secondary industry) | + | 0.230 | |||

| Economic Status | X9 Contribution of Marine Economy (ratio of marine gross product to regional gross domestic product) (%) | + | 0.148 | ||

| X10 Marine Economic Location Entropy (ratio of marine gross product of coastal areas to total marine gross product of all coastal areas/ratio of GDP of coastal areas to total GDP of all coastal areas) (%) | + | 0.160 | |||

| Green Construction 0.152 | Ecological Carrying Capacity | X11 Wetland Area per Capita in Coastal Areas/Total Regional Population (thousand hectares per ten thousand people) | + | 0.337 | |

| Ecological Efficiency | X12 Ecological Efficiency (marine gross product/industrial wastewater and waste emission volume) (CNY ten thousand per ton) | + | 0.213 | ||

| X13 Land Efficiency (marine gross product/seawater farming area in coastal areas) (CNY hundred million per hectare) | + | 0.133 | |||

| X14 Energy Consumption Per Unit Marine GDP (energy consumption of coastal region’s GDP/proportion of marine GDP in regional GDP) (ten thousand tons of standard coal per CNY) | − | 0.108 | |||

| Ecological Protection | X15 Per Capita Area of Marine-Type Nature Reserves in Coastal Areas (square kilometers per ten thousand people) | + | 0.171 | ||

| X16 Density of Coastal Observation Stations Per Unit Length of Shoreline (number per meter) | + | 0.376 | |||

| Open Cooperation 0.155 | Port Opening | X17 Proportion of International Container Throughput in Ports to Total Regional Volume (%) | + | 0.177 | |

| Urban Opening | X18 Number of Inbound Tourists/Total Regional Population (%) | + | 0.263 | ||

| Trade Opening | X19 Proportion of Actual Utilized Foreign Investment to GDP (%) | + | 0.206 | ||

| X20 Degree of Economic Outward Orientation in Coastal Areas (total value of goods trade/gross domestic product) (%) | + | 0.354 | |||

| Sharing of Livelihoods 0.171 | Employment Opportunities | X21 Proportion of Marine-Related Employees to Total Regional Employees (%) | + | 0.114 | |

| Resident Living Standards | X22 Seafood Supply Capacity (aquaculture + fishing + deep-sea catch)/Total Regional Population (tons per ten thousand people) | + | 0.200 | ||

| X23 Per Capita Disposable Income of Coastal Area Residents (CNY per person) | + | 0.119 | |||

| X24 Engel’s Coefficient for Coastal Area Households (%) | − | 0.253 | |||

| Education Sharing | X25 Proportion of Students Enrolled in Marine Programs in General Higher Education (%) | + | 0.173 | ||

| X26 Number of Higher Education Institutions (institutions) Offering Marine Programs (number) | + | 0.142 |

| Influencing Factor | Frequency | Proportion (%) | Influencing Factor | Frequency | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government Intervention | 15 | 24.19 | Marketization Rate | 2 | 3.23 |

| Financial Scale | 12 | 19.35 | Urban and Rural Residents’ Savings Deposits Level | 1 | 1.61 |

| Industrial Scale | 9 | 14.52 | Social Capital Level | 1 | 1.61 |

| Population Density | 5 | 8.06 | Degree of Resource Endowment | 1 | 1.61 |

| Road Coverage Rate | 5 | 8.06 | Educational Expenditure | 1 | 1.61 |

| Urbanization Rate | 4 | 6.45 | Social Consumption Level | 1 | 1.61 |

| Information Technology Level | 3 | 4.84 | Total | 62 | 100.00 |

| Industrialization Level | 2 | 3.23 |

| Type | Region |

|---|---|

| Leading | Shanghai |

| Catching-Up | Fujian, Guangdong, Hainan, Shandong, Liaoning, Zhejiang |

| Lagging | Hebei, Guangxi, Tianjin, Jiangsu |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DID | 0.01617 ** | 0.04053 *** | 0.01308 *** |

| (0.00615) | (0.01174) | (0.00396) | |

| Other Control Variables | Control | ||

| Sample Size | 112 | 176 | 176 |

| R2 | 0.1437 | 0.1478 | 0.3456 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DID | 0.9158 *** | 0.7798 *** | 0.6348 *** |

| (0.1663) | (0.0793) | (0.0990) | |

| Other Control Variables | Control | ||

| Sample Size | 80 | 176 | 176 |

| R2 | 0.5291 | 0.2071 | 0.3179 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, L.; Yu, S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, F.; Yang, X. The Role of Heterogeneous Marine Environmental Regulation in SDGs-Integrated Marine Economic Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11141. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411141

Gao L, Yu S, Zhang L, Wang F, Yang X. The Role of Heterogeneous Marine Environmental Regulation in SDGs-Integrated Marine Economic Development. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11141. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411141

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Lehua, Shuang Yu, Longxuan Zhang, Fengyao Wang, and Xueke Yang. 2025. "The Role of Heterogeneous Marine Environmental Regulation in SDGs-Integrated Marine Economic Development" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11141. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411141

APA StyleGao, L., Yu, S., Zhang, L., Wang, F., & Yang, X. (2025). The Role of Heterogeneous Marine Environmental Regulation in SDGs-Integrated Marine Economic Development. Sustainability, 17(24), 11141. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411141