The Impact of Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction on University Teachers’ Work Engagement in the Context of Education for Sustainable Development: A Chain Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Does basic psychological need satisfaction affect university teachers’ work engagement?

- Does organizational identification mediate the relationship between basic psychological need satisfaction and university teachers’ work engagement?

- Does job satisfaction mediate the relationship between basic psychological need satisfaction and university teachers’ work engagement?

- Do organizational identification and job satisfaction sequentially mediate the relationship between basic psychological need satisfaction and university teachers’ work engagement?

2. Theoretical Foundation

2.1. Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) Model

2.2. Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction (BPNS) and Work Engagement (WE)

2.3. The Mediating Role of Organizational Identification (OI)

2.4. The Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction (JS)

2.5. The Chain Mediating Role of Organizational Identification and Job Satisfaction

3. Research Methods

3.1. Research Participants

3.2. Measurement Instruments

3.2.1. Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction Scale

3.2.2. Organizational Identification Scale

3.2.3. Job Satisfaction Scale

3.2.4. Work Engagement Scale

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Research Results

4.1. Participants Analysis

4.2. Common Method Bias

4.3. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

4.4. Convergent and Discriminant Validity Tests

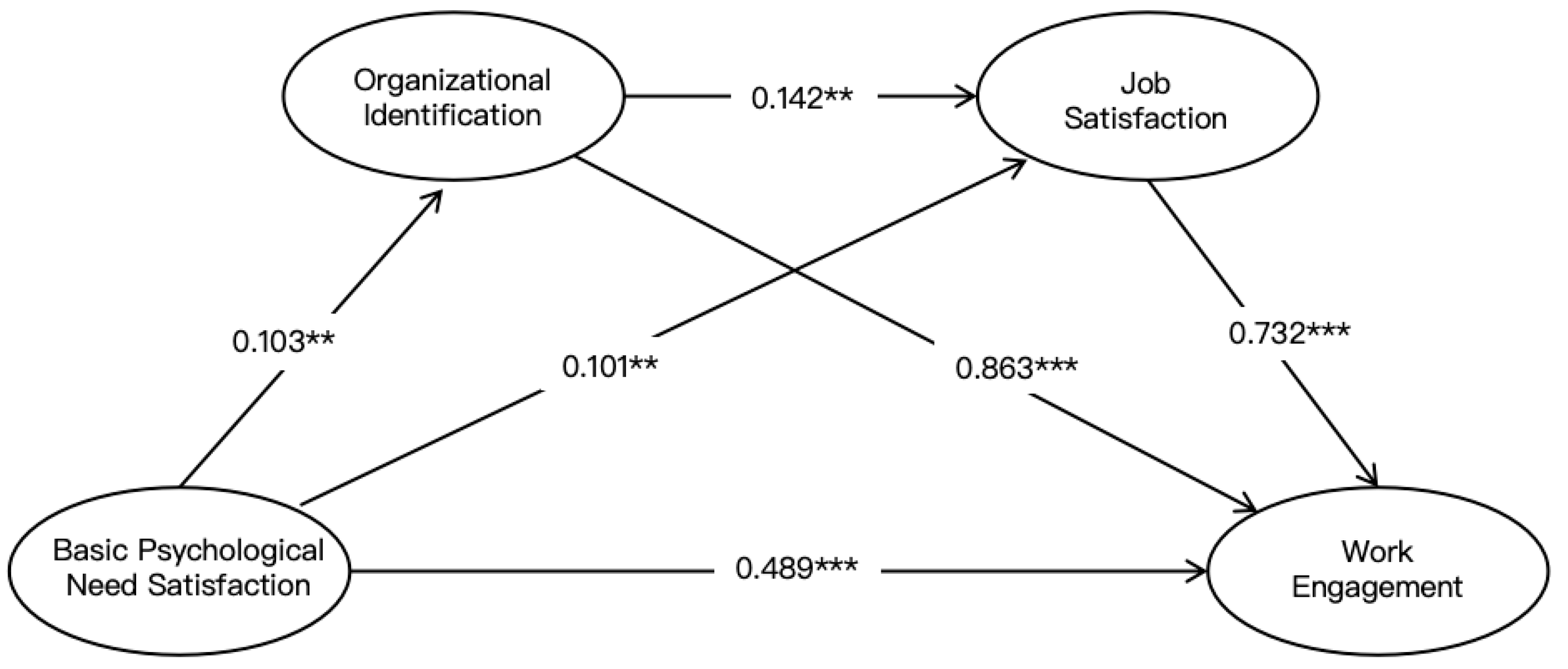

4.5. Chain Mediation Effect Test

5. Discussion and Limitations

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BPNS | Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction |

| WE | Work Engagement |

| OI | Organizational Identification |

| JS | Job Satisfaction |

Appendix A

| Items (In Simplified Chinese) | Items (In English) | |

| BPNS1 | 在工作中,我能与同事建立真诚、互信的关系 | I can build genuine and trusting relationships with my colleagues at work |

| BPNS2 | 我经常觉得自己缺乏完成教学或科研任务的能力 | I often feel unable to complete my teaching or research responsibilities |

| BPNS3 | 我的工作压力很大,常常感到身心俱疲 | I often feel physically and mentally drained due to my work |

| BPNS4 | 我相信自己能够高质量地完成所承担的专业工作 | I am confident in my ability to perform my professional duties at a high standard |

| BPNS5 | 我与学生、同事和领导之间保持着良好的互动 | I have positive interactions with students, colleagues, and supervisors |

| BPNS6 | 我在工作中很少有机会与他人深入交流或合作 | I seldom have opportunities to engage in meaningful communication or collaboration with others at work |

| BPNS7 | 我能够按照自己的学术兴趣和教育理念开展教学与研究 | I can carry out my teaching and research according to my academic interests and educational philosophy |

| BPNS8 | 我近期在专业能力或知识上取得了明显的进步 | I have recently achieved significant improvement in my professional abilities or knowledge |

| BPNS9 | 我的工作安排主要由他人决定,个人选择空间很小 | Most of my work is assigned by others, and I have little autonomy in choosing how to organize it |

| BPNS10 | 我感受到来自同事和团队的理解与支持 | I perceive understanding and support from my colleagues and team |

| BPNS11 | 我能从教学或科研工作中获得成就感和意义感 | I gain a sense of achievement and purpose from my teaching and research activities |

| BPNS12 | 在日常工作中,他人会尊重我的观点和专业判断 | Others respect my viewpoints and professional judgments in my daily work |

| BPNS13 | 我在工作中很少有机会发挥自己的专业特长 | I seldom have the chance to utilize my professional skills in my work |

| BPNS14 | 我在高校环境中缺乏可以信赖的同行或朋友 | I do not have trustworthy colleagues or friends in my university environment |

| BPNS15 | 我能够真实地表达自己的学术立场和教育主张 | I can genuinely express my academic stance and educational philosophy |

| BPNS16 | 周围的人对我并不真正认可或接纳 | Those around me do not truly acknowledge or accept me |

| BPNS17 | 我常常怀疑自己的专业能力和职业价值 | I often question my professional competence and sense of vocational worth |

| BPNS18 | 我在工作中很少能按自己的意愿做决定 | I seldom get to make work-related decisions based on my own choices |

| BPNS19 | 同事和学生普遍对我持友善和尊重的态度 | I am generally treated with friendliness and respect by colleagues and students |

| OI1 | 当听到别人称赞我所在的学校时,我感觉就像是在称赞我一样 | Hearing praise for my university makes me feel personally appreciated |

| OI2 | 我所在学校的成功就是我的成功 | I feel that the achievements of my university reflect my own success |

| OI3 | 我很想了解别人是如何评价我所在的学校的 | I care about others’ opinions regarding my university |

| OI4 | 当听到别人批评我所在的学校时,我感觉就像是在批评我一样 | Hearing criticism of my university makes me feel personally criticized |

| OI5 | 如果发现新闻媒体批评我所在的学校,我会感到不安 | I feel unsettled if news outlets criticize my university |

| OI6 | 当谈起我所在的学校时,我经常说”我们”而不是”他们” | I usually refer to my university as ‘we’ rather than ‘they’ when discussing it |

| JS1 | 我的工作能给我带来学习成长的机会 | I gain opportunities for personal and professional development through my work |

| JS2 | 我的工作很稳定,这使我感到满意 | My work is stable, which makes me feel satisfied |

| JS3 | 在工作中有被尊重的感觉 | I feel respected in my work |

| JS4 | 我从工作中获得很大的快乐 | I derive great joy from my work |

| JS5 | 我经常在工作中体验到成就感 | I often experience a sense of accomplishment in my work |

| JS6 | 学校给予教师工作足够的支持 | My university offers adequate support to teachers in their work |

| JS7 | 学校所提供的福利待遇让我感到满意 | I am satisfied with the benefits and compensation provided by my university |

| JS8 | 我对学校提供的办公条件感到满意 | I am satisfied with the working conditions provided by my university |

| JS9 | 自己目前薪酬与我实际的工作付出相较,让我感到满意 | I am satisfied with my current salary relative to the work I contribute |

| JS10 | 我对目前的工作负荷感到满意 | I am satisfied with my current workload |

| WE1 | 在工作中,我感到自己迸发出能量 | I feel energized and full of vitality in my work |

| WE2 | 工作时,我感到自己强大并且充满活力 | I feel powerful and energized while performing my work |

| WE3 | 我对工作富有热情 | I feel passionate and motivated in my work. |

| WE4 | 工作激发了我的灵感 | I feel inspired by my work |

| WE5 | 早上一起床,我就想要去工作 | When I wake up in the morning, I look forward to going to work |

| WE6 | 当工作紧张的时候,我会感到快乐 | I experience joy even during periods of high work pressure |

| WE7 | 我为自己所从事的工作感到自豪 | I experience joy even during periods of high work pressure |

| WE8 | 我沉浸于我的工作当中 | I become fully immersed in my work |

| WE9 | 我在工作时会达到忘我的境界 | When working, I become completely absorbed and lose track of time |

References

- Sterling, S. An Analysis of the Development of Sustainability Education Internationally: Evolution, Interpretation and Transformative Potential. In The Sustainability Curriculum; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bulut, B.; Elci Oksuzoglu, I. Teachers’ Beliefs About Education for Sustainable Development: Challenges and Opportunities. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, S.; Metzger, E. Barriers to Learning for Sustainability: A Teacher Perspective. Sustain. Earth Rev. 2023, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltner, E.-M.; Scharenberg, K.; Hörsch, C.; Rieß, W. What Teachers Think and Know about Education for Sustainable Development and How They Implement It in Class. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouin-Rousseau, S.; Morin, A.J.S.; Fernet, C.; Blechman, Y.; Gillet, N. Teachers’ Profiles of Work Engagement and Burnout over the Course of a School Year. Appl. Psychol. 2024, 73, 57–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkesmann, U.; Vorberg, R. The Influence of Relatedness and Organizational Resources on Teaching Motivation in Continuing Higher Education. Z. Für Weiterbildungsforschung 2021, 44, 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Chu, P.; Wang, J.; Pan, R.; Sun, Y.; Yan, M.; Jiao, L.; Zhan, X.; Zhang, D. Association between Job Stress and Organizational Commitment in Three Types of Chinese University Teachers: Mediating Effects of Job Burnout and Job Satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 576768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liao, X.; Li, Q.; Jiang, W.; Ding, W. The Relationship between Teacher Job Stress and Burnout: A Moderated Mediation Model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 784243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Leiter, M.P. Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-1-136-98087-9. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.-T.; Guo, M. Facing Disadvantages: The Changing Professional Identities of College English Teachers in a Managerial Context. System 2019, 82, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdaus, H.B.; Liza, S.A.; Al Masud, A.; Hossain, A. Impact of Knowledge Management on Knowledge Worker Productivity: Individual Knowledge Management Engagement as a Mediator. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2025, 23, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beurden, J.V.; Veldhoven, M.V.; Voorde, K.V.D. How Employee Perceptions of HR Practices in Schools Relate to Employee Work Engagement and Job Performance. J. Manag. Organ. 2025, 31, 1872–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, S. Faculty Work Engagement and Teaching Effectiveness in a State Higher Education Institution. Int. J. Educ. Res. Rev. 2021, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; Gamble, J.H. Teacher Burnout and Turnover Intention in Higher Education: The Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction and the Moderating Role of Proactive Personality. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1076277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, K.; Garvis, S. Teacher Educator Wellbeing, Stress and Burnout: A Scoping Review. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taris, T.W.; Schaufeli, W.B. The Job Demands-Resources Model. In The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of the Psychology of Occupational Safety and Workplace Health; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 155–180. ISBN 978-1-118-97901-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W. A Critical Review of the Job Demands-Resources Model: Implications for Improving Work and Health. In Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health: A Transdisciplinary Approach; Bauer, G.F., Hämmig, O., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 43–68. ISBN 978-94-007-5640-3. [Google Scholar]

- Airila, A.; Hakanen, J.J.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Luukkonen, R.; Punakallio, A.; Lusa, S. Are Job and Personal Resources Associated with Work Ability 10 Years Later? The Mediating Role of Work Engagement. Work Stress 2014, 28, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, D.I., Jr.; Ferreira, M.C.; Valentini, F. Work Demands, Personal Resources and Work Outcomes: The Mediation of Engagement*. Univ. Psychol. 2021, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Han, S.J.; Park, J. Is the Role of Work Engagement Essential to Employee Performance or ‘Nice to Have’? Sustainability 2019, 11, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetti, G.; Robledo, E.; Vignoli, M.; Topa, G.; Guglielmi, D.; Schaufeli, W.B. Work Engagement: A Meta-Analysis Using the Job Demands-Resources Model. Psychol. Rep. 2023, 126, 1069–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, R.; Vîrgă, D. Psychological Needs Matter More than Social and Organizational Resources in Explaining Organizational Commitment. Scand. J. Psychol. 2021, 62, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Broeck, A.; Ferris, D.L.; Chang, C.-H.; Rosen, C.C. A Review of Self-Determination Theory’s Basic Psychological Needs at Work. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1195–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungra, Y.; Srivastava, R.; Sharma, A.; Banerji, D.; Gollapudi, N. Impact of Digital Competence on Employees’ Flourishing through Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2024, 64, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapica, Ł.; Baka, Ł.; Stachura-Krzyształowicz, A. Job resources and work engagement: The mediating role of basic need satisfaction. Med. Pr. 2022, 73, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmadani, V.G.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Ivanova, T.Y.; Osin, E.N. Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction Mediates the Relationship between Engaging Leadership and Work Engagement: A Cross-National Study. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2019, 30, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maunz, L.A.; Glaser, J. Longitudinal Dynamics of Psychological Need Satisfaction, Meaning in Work, and Burnout. J. Vocat. Behav. 2024, 150, 103971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanouli, A.; Bidee, J.; Hofmans, J. Need Satisfaction and Organizational Citizenship Behaviour towards the Organization. A Process-Oriented Approach. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 10813–10824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M.R. Organizational Identification: A Conceptual and Operational Review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2005, 7, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zhu, W.; Zheng, X. Procedural Justice and Employee Engagement: Roles of Organizational Identification and Moral Identity Centrality. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simbula, S.; Margheritti, S.; Avanzi, L. Building Work Engagement in Organizations: A Longitudinal Study Combining Social Exchange and Social Identity Theories. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coxen, L.; van der Vaart, L.; Van den Broeck, A.; Rothmann, S. Basic Psychological Needs in the Work Context: A Systematic Literature Review of Diary Studies. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 698526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Angulo, L.; Lucia-Casademunt, A.M.; Gómez-Baya, D. Satisfaction of Basic Psychological Needs and European Entrepreneurs’ Well-Being and Health: The Association with Job Satisfaction and Entrepreneurial Motivation. Scand. J. Psychol. 2024, 65, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. What Is Job Satisfaction? Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1969, 4, 309–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, E.; Workineh, Y.; Abate, A.; Zeleke, B.; Semachew, A.; Woldegiorgies, T. Intrinsic Motivation Factors Associated with Job Satisfaction of Nurses in Three Selected Public Hospitals in Amhara Regional State, 2018. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2021, 15, 100340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, D.; Takada, N.; Hara, Y.; Sugiyama, S.; Ito, Y.; Nihei, Y.; Asakura, K. Impact of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation on Work Engagement: A Cross-Sectional Study of Nurses Working in Long-Term Care Facilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, W.; Ni, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Zeng, Y.; Yu, C. How Do Different Perceived School Goal Structures Affect Chinese Kindergarten Teachers’ Professional Identity? The Role of Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction and Growth Mindset. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1588334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufino, M.; Lorejo, E. Organizational Awareness, Identification and Commitment of Higher Education Instructors. J. Namib. Stud. Hist. Polit. Cult. 2022, 32, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriş, A.; Kökalan, Ö. The Moderating Effect of Organizational Identification on the Relationship Between Organizational Role Stress and Job Satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 892983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, P.P.; Colomeischi, A.A. Positivity Ratio and Well-Being Among Teachers. The Mediating Role of Work Engagement. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The Job Demands-Resources Model of Burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job Demands, Job Resources, and Their Relationship with Burnout and Engagement: A Multi-Sample Study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B. Applying the Job Demands-Resources Model: A ‘How to’ Guide to Measuring and Tackling Work Engagement and Burnout. Organ. Dyn. 2017, 46, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotič, L.P.; Man, M.M.K.; Soga, L.R.; Konstantopoulou, A.; Lodorfos, G. Job Characteristics for Work Engagement: Autonomy, Feedback, Skill Variety, Task Identity, and Task Significance. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2025, 44, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, J.W.; Agardh, A.; Östergren, P.-O. Validating a Modified Instrument for Measuring Demand-Control-Support among Students at a Large University in Southern Sweden. Glob. Health Action 2023, 16, 2226913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Beyers, W.; Boone, L.; Deci, E.L.; Van der Kaap-Deeder, J.; Duriez, B.; Lens, W.; Matos, L.; Mouratidis, A.; et al. Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction, Need Frustration, and Need Strength across Four Cultures. Motiv. Emot. 2015, 39, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F. The Need for and Meaning of Positive Organizational Behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The Measurement of Engagement and Burnout: A Two Sample Confirmatory Factor Analytic Approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Francisco, C.; Sánchez-Romero, E.I.; Vílchez Conesa, M.D.P.; Arce, C. Basic Psychological Needs, Burnout and Engagement in Sport: The Mediating Role of Motivation Regulation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, A.; Vansteenkiste, M.; de Witte, H.; Lens, W. Explaining the Relationships between Job Characteristics, Burnout, and Engagement: The Role of Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction. Work Stress 2008, 22, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C.; Madden, A.; Alfes, K.; Fletcher, L. The Meaning, Antecedents and Outcomes of Employee Engagement: A Narrative Synthesis. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C.; Brown, R.J.; Tajfel, H. Social Comparison and Group Interest in Ingroup Favouritism. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1979, 9, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social Identity Theory and the Organization. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Dukerich, J.M.; Harquail, C.V. Organizational Images and Member Identification. Adm. Sci. Q. 1994, 39, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P.C. Identity in Organizations: Building Theory through Conversations; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-7619-0948-4. [Google Scholar]

- Van Knippenberg, D.; Van Schie, E.C.M. Foci and Correlates of Organizational Identification. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2000, 73, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Verbeke, W. Using the Job Demands-Resources Model to Predict Burnout and Performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 43, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondeaux, G. Modernizing Public Administration: The Impact on Organisational Identities. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2006, 19, 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smollan, R.; Pio, E. Organisational Change, Identity and Coping with Stress. N. Z. J. Employ. Relat. 2020, 43, 56–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Lin, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Tang, J. Mediation Role of Work Motivation and Job Satisfaction between Work-Related Basic Need Satisfaction and Work Engagement among Doctors in China: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e060599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhao, Z. An Empirical Study on Job Satisfaction Among Primary School Teachers in Beijing. Res. Teach. Educ. 2012, 24, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömgren, M.; Eriksson, A.; Bergman, D.; Dellve, L. Social Capital among Healthcare Professionals: A Prospective Study of Its Importance for Job Satisfaction, Work Engagement and Engagement in Clinical Improvements. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 53, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Gancedo, J.; Fernández-Martínez, E.; Rodríguez-Borrego, M.A. Relationships among General Health, Job Satisfaction, Work Engagement and Job Features in Nurses Working in a Public Hospital: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 1273–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busque-Carrier, M.; Ratelle, C.F.; Le Corff, Y. Work Values and Job Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Basic Psychological Needs at Work. J. Career Dev. 2022, 49, 1386–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dick, R.; Christ, O.; Stellmacher, J.; Wagner, U.; Ahlswede, O.; Grubba, C.; Hauptmeier, M.; Höhfeld, C.; Moltzen, K.; Tissington, P.A. Should I Stay or Should I Go? Explaining Turnover Intentions with Organizational Identification and Job Satisfaction. Br. J. Manag. 2004, 15, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Wen, Y.; Xu, Y.; He, L.; You, G. The Relationship between Work Practice Environment and Work Engagement among Nurses: The Multiple Mediation of Basic Psychological Needs and Organizational Commitment a Cross-Sectional Survey. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1123580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanika-Murray, M.; Duncan, N.; Pontes, H.M.; Griffiths, M.D. Organizational Identification, Work Engagement, and Job Satisfaction. J. Manag. Psychol. 2015, 30, 1019–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tett, R.P.; Meyer, J.P. Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment, Turnover Intention, and Turnover: Path Analyses Based on Meta-Analytic Findings. Pers. Psychol. 1993, 46, 259–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-S.; Lin, L.-L.; Lv, Y.; Wei, C.-B.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, X.-Y. Reliability and Validity of the Chinese Version of the Basic Psychological Needs Scale. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2013, 27, 791–795. [Google Scholar]

- Yongxin, L.; Jiliang, S.; Na, Z. Revisioning Organizational Identification Questionnaire for Teachers. Stud. Psychol. Behav. 2008, 6, 176. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, T.C.; Ng, S. Measuring Engagement at Work: Validation of the Chinese Version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2012, 19, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Urreta, M.I.; Hu, J. Detecting Common Method Bias: Performance of the Harman’s Single-Factor Test. SIGMIS Database 2019, 50, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wen, Z. Item Parceling Strategies in Structural Equation Modeling. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 19, 1859–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Zheng, X.; Gao, L.; Cao, Z.; Ni, X. Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction Mediates the Link between Strengths Use and Teachers’ Work Engagement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Y.; Wu, D.; Bao, Y.; Li, J.; You, G. The Mediating Role of Psychological Needs on the Relationship between Perceived Organizational Support and Work Engagement. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2023, 70, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, J.F.S.; Marques, T.; Cabral, C. Responsible Leadership, Organizational Commitment, and Work Engagement: The Mediator Role of Organizational Identification. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2022, 33, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Kong, X.; Qian, M.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Gao, S.; Ning, L.; Yu, X. The Effect of Work-Family Conflict on Employee Well-Being among Physicians: The Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction and Work Engagement. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; He, J.; Fu, D. How Can We Improve Teacher’s Work Engagement? Based on Chinese Experiences. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 721450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Podsakoff, N.P.; Williams, L.J.; Huang, C.; Yang, J. Common Method Bias: It’s Bad, It’s Complex, It’s Widespread, and It’s Not Easy to Fix. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2024, 11, 17–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.E.; Cole, D.A. Bias in Cross-Sectional Analyses of Longitudinal Mediation. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Descriptor | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regions | East China | 198 | 41.0% |

| Central China | 126 | 26.1% | |

| West China | 121 | 25.1% | |

| Northeast China | 38 | 7.9% | |

| Institutional types | Comprehensive universities | 186 | 38.5% |

| Science and engineering universities | 98 | 20.3% | |

| Normal universities | 87 | 18.0% | |

| Medical universities | 65 | 13.5% | |

| Agricultural and other specialized institutions | 47 | 9.7% |

| Variable | M | SD | 1. BPNS | 2. OI | 3. JS | 4. WE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. BPNS | 3.933 | 1.360 | 0.81 | |||

| 2. OI | 2.939 | 1.073 | 0.131 ** | 0.78 | ||

| 3. JS | 2.966 | 1.115 | 0.140 ** | 0.138 ** | 0.80 | |

| 4. WE | 3.798 | 1.970 | 0.452 ** | 0.522 ** | 0.506 ** | 0.88 |

| Variable | Measurement Item | B | β | S.E. | C.R. | p | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPNS | BPNS1 | 1.000 | 0.799 | / | / | / | 0.973 | 0.656 |

| BPNS2 | 0.952 | 0.796 | 0.047 | 20.226 | <0.001 | |||

| … | … | … | … | … | <0.001 | |||

| BPNS19 | 1.050 | 0.822 | 0.050 | 21.137 | <0.001 | |||

| OI | OI1 | 1.000 | 0.767 | / | / | / | 0.903 | 0.609 |

| OI2 | 0.983 | 0.774 | 0.056 | 17.547 | <0.001 | |||

| … | … | … | … | … | <0.001 | |||

| OI6 | 1.027 | 0.793 | 0.057 | 18.058 | <0.001 | |||

| JS | JS1 | 1.000 | 0.805 | / | / | / | 0.948 | 0.648 |

| JS2 | 0.986 | 0.791 | 0.049 | 19.932 | <0.001 | |||

| … | … | … | … | … | <0.001 | |||

| JS10 | 0.994 | 0.796 | 0.049 | 20.092 | <0.001 | |||

| WE | WE1 | 1.000 | 0.914 | / | / | / | 0.973 | 0.782 |

| WE2 | 0.999 | 0.907 | 0.030 | 33.651 | <0.001 | |||

| … | … | … | … | … | <0.001 | |||

| WE9 | 0.991 | 0.911 | 0.029 | 24.606 | <0.001 |

| Effect | Path | Estimate | Effect Size | p | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Direct Effect | BPNS→WE | 0.489 | 73.87% | 0.000 | 0.395 | 0.585 |

| Indirect Effect | BPNS→OI→WE | 0.089 | 13.44% | 0.004 | 0.030 | 0.157 |

| BPNS→JS→WE | 0.074 | 11.18% | 0.009 | 0.018 | 0.130 | |

| BPNS→OI→JS→WE | 0.011 | 1.66% | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.027 | |

| Total Indirect Effect | 0.173 | 26.13% | 0.001 | 0.086 | 0.262 | |

| Total Effect | 0.662 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Yoon, M. The Impact of Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction on University Teachers’ Work Engagement in the Context of Education for Sustainable Development: A Chain Mediation Model. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11140. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411140

Zhang X, Yoon M. The Impact of Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction on University Teachers’ Work Engagement in the Context of Education for Sustainable Development: A Chain Mediation Model. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11140. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411140

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xiaohan, and Mankeun Yoon. 2025. "The Impact of Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction on University Teachers’ Work Engagement in the Context of Education for Sustainable Development: A Chain Mediation Model" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11140. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411140

APA StyleZhang, X., & Yoon, M. (2025). The Impact of Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction on University Teachers’ Work Engagement in the Context of Education for Sustainable Development: A Chain Mediation Model. Sustainability, 17(24), 11140. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411140