Modeled Bed Stress Patterns Around Pervious Oyster Shell Habitat Units Using Large-Eddy Simulations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

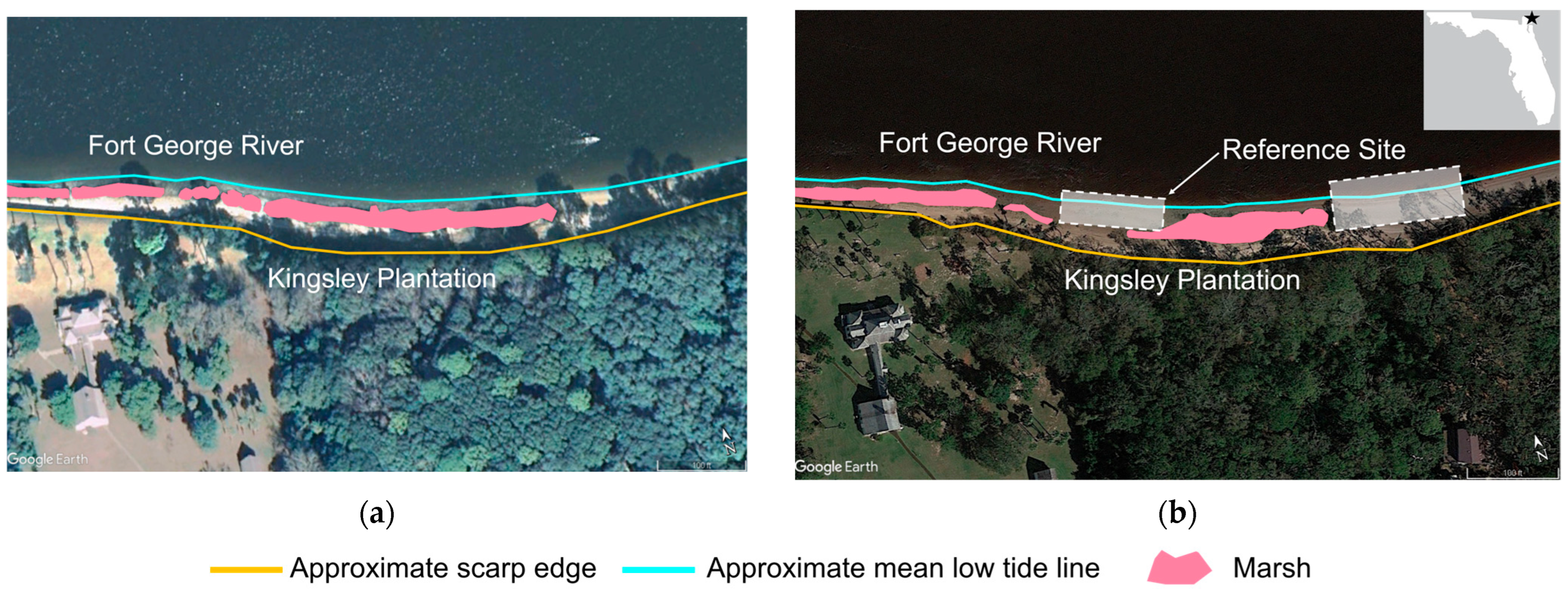

2.1. Study Site

2.1.1. Kingsley Plantation

2.1.2. POSH Unit Deployments

2.1.3. Preliminary Analyses

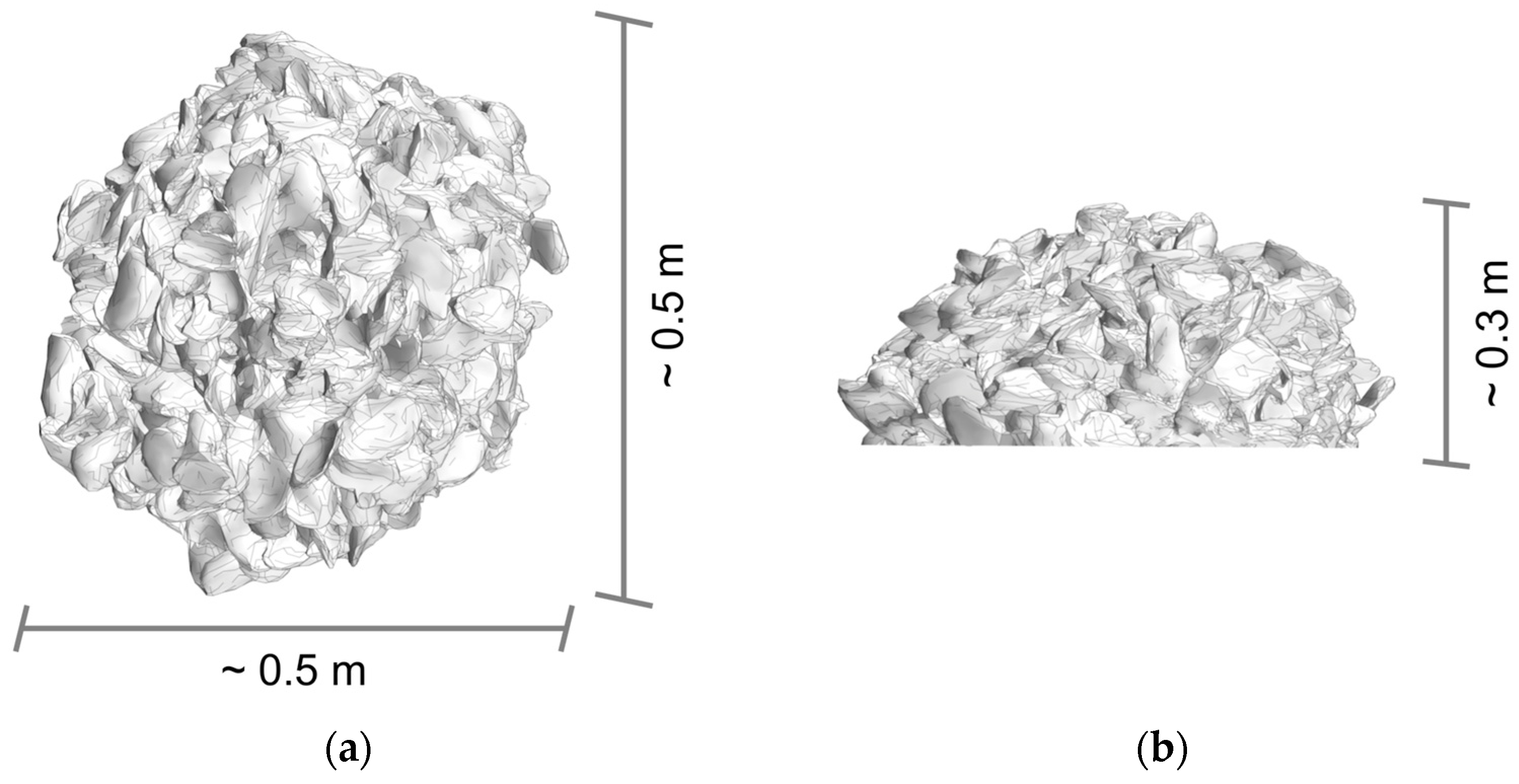

2.2. CFD Model Preparation

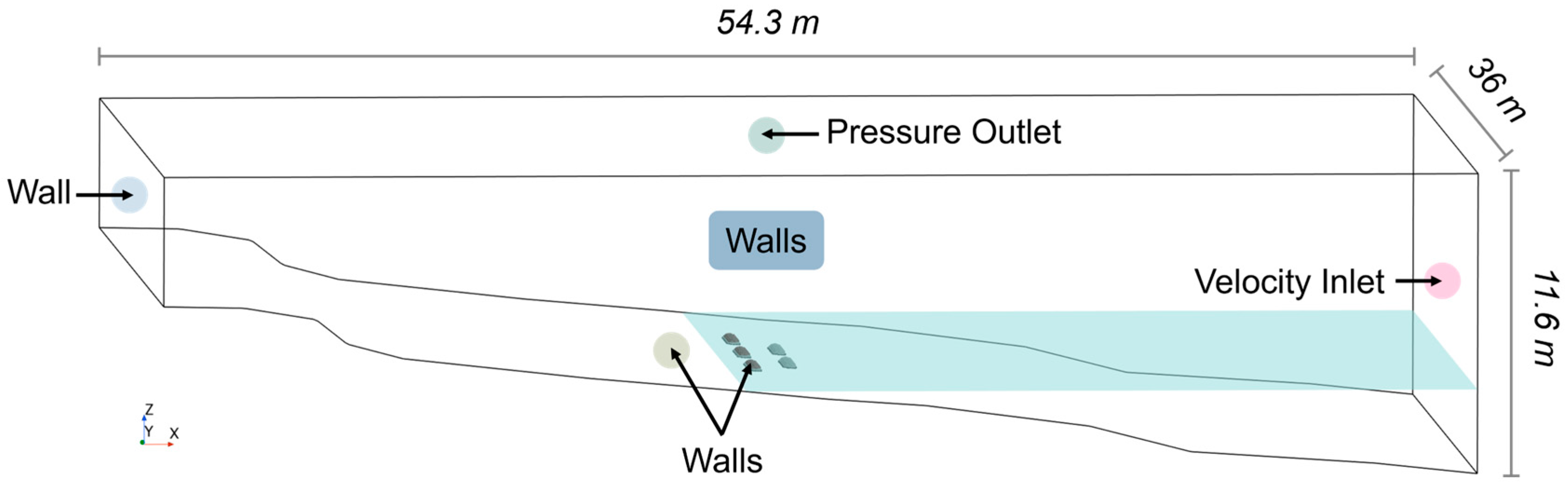

2.2.1. CFD Model Geometry and Mesh

2.2.2. CFD Model Physics

2.2.3. CFD Model Testing Conditions

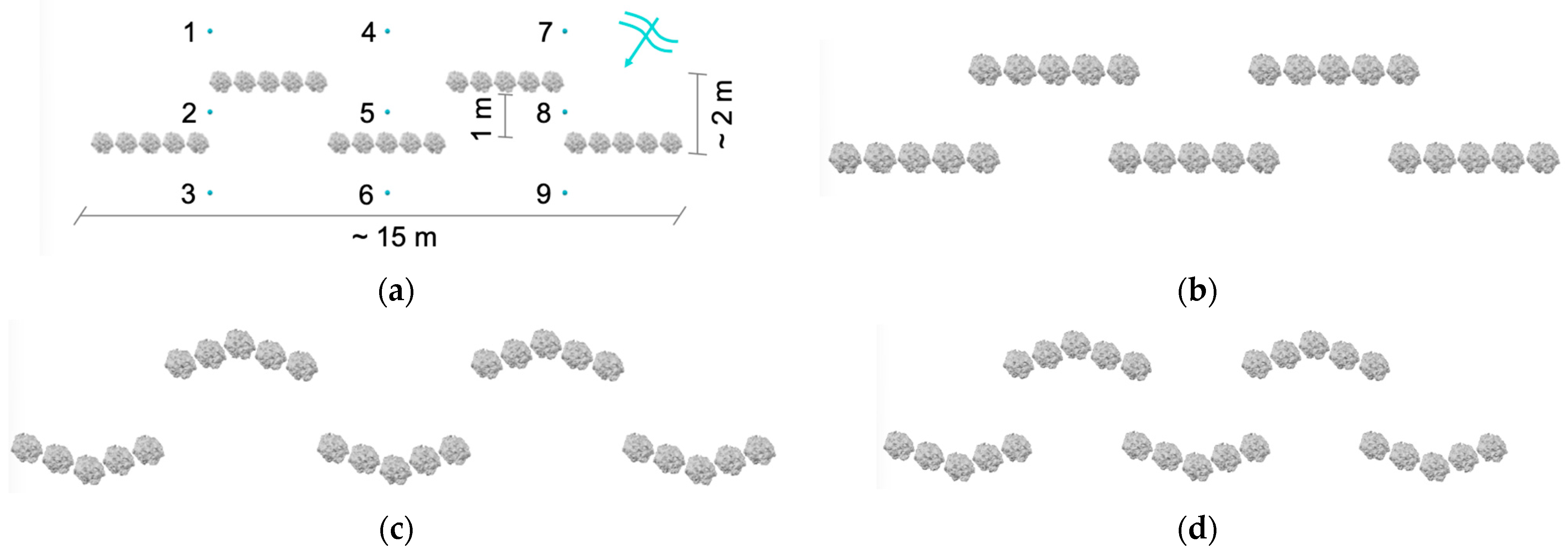

2.3. Modeled Bed Stress Data Collection

2.3.1. Bed Stress Distributions

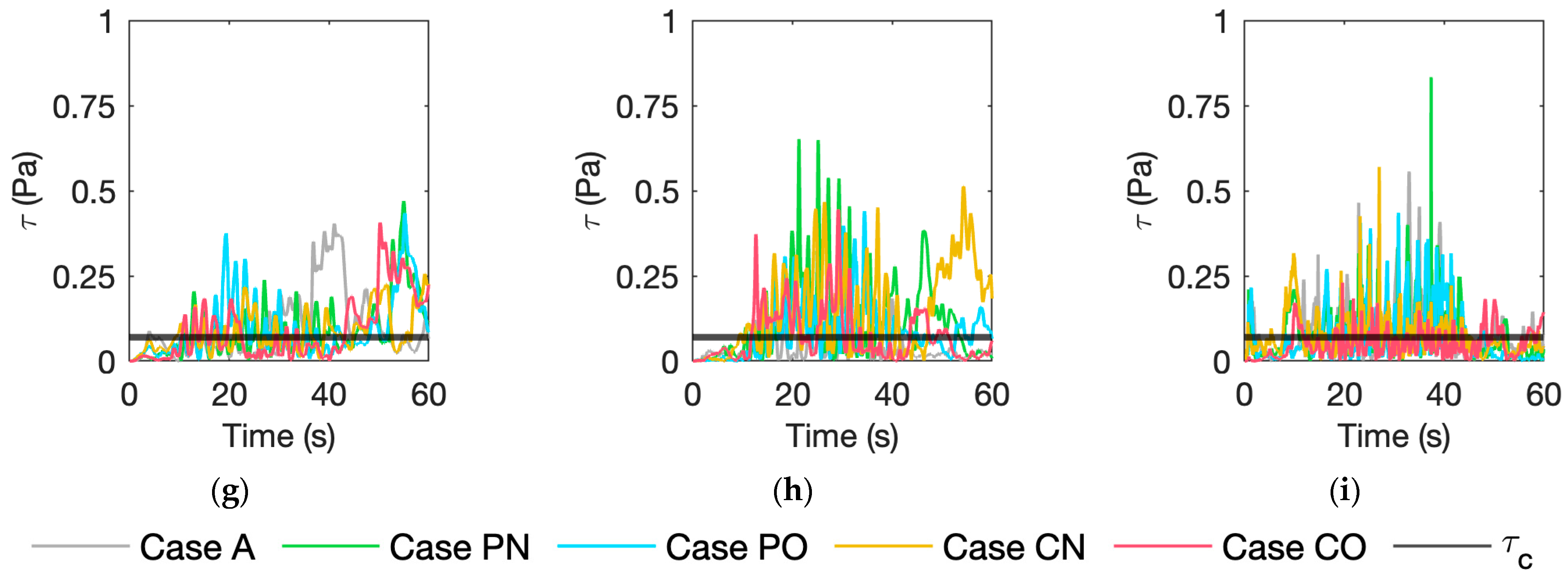

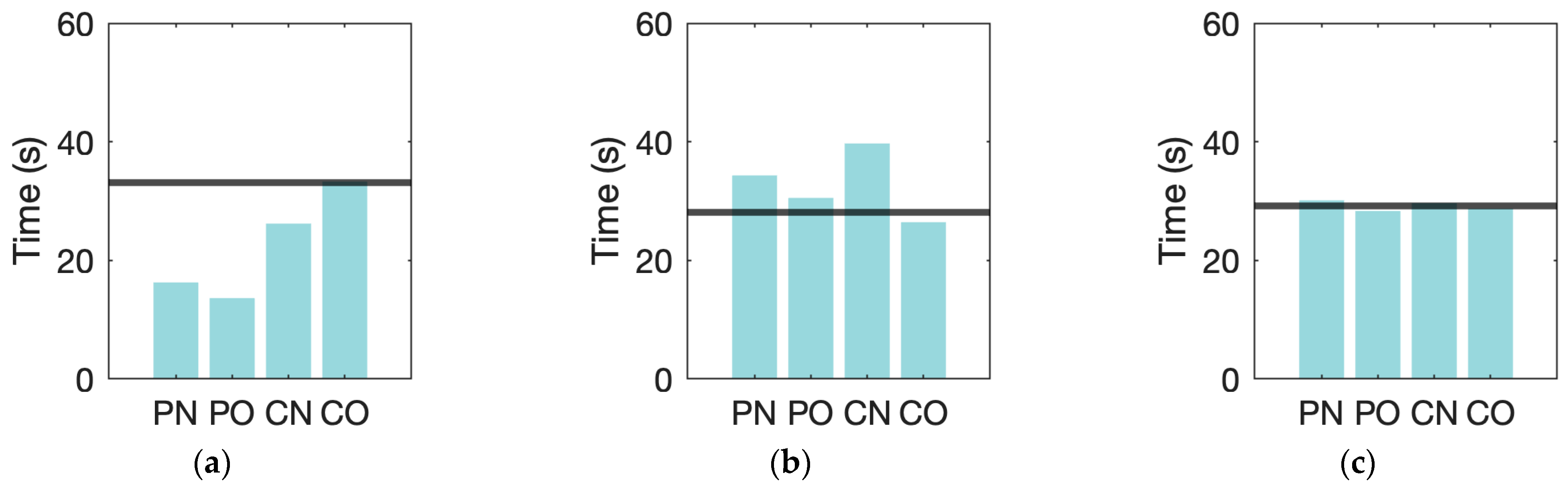

2.3.2. Bed Stress Time-Series

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Boat Wakes and Bed Stress

4.2. Effect of POSH Units on Bed Stress Patterns

4.2.1. Bed Stress Reductions

4.2.2. Bed Stress Amplifications

4.2.3. Arrangement Evaluation

4.3. Recommendations for Future Living Shoreline Designs

5. Conclusions

- (1)

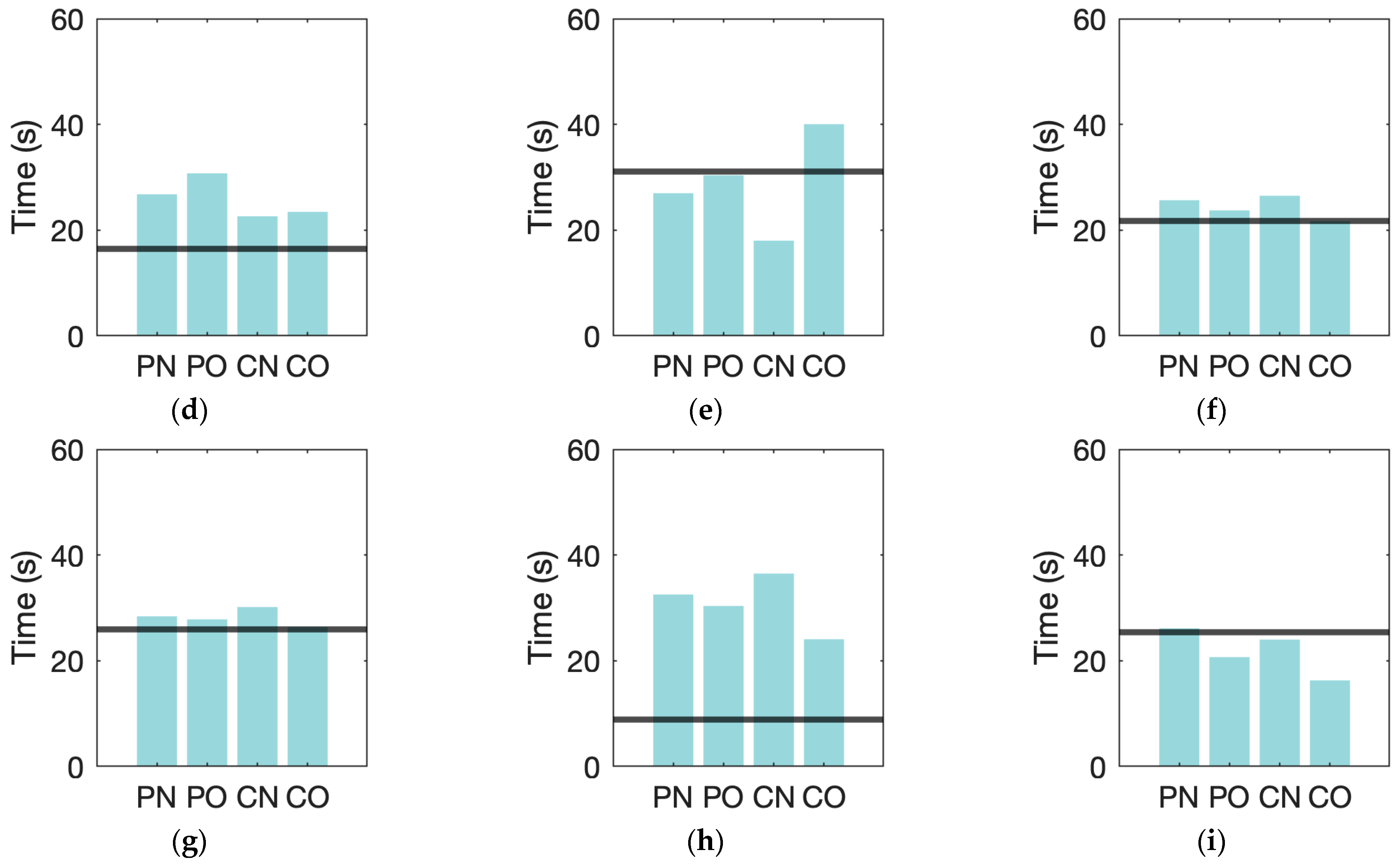

- Adding POSH units to a shoreline in a segmented breakwater arrangement can alter bed stress patterns. All four POSH unit arrangements changed bed stress patterns and resulted in areas of increased and decreased stress when compared to the control case. POSH units increased stress between the units and rows, where scouring and erosion could occur. However, they also reduced stress in other areas which could allow for accretion and sediment buildup.

- (2)

- Low-stress areas below can potentially allow for accretion. Modeled CFD results indicated that POSH units could provide lower stress in shadow zones in the vicinity of individual units and landward of the units. Field observations confirmed that sediment is being trapped landward of the structures. This accumulation will hopefully build up the shoreline in the long term and allow for benefits such as vegetation growth and expansion.

- (3)

- An overlapping chevron pattern may be beneficial for a living shoreline at a site with waves approaching at an oblique angle, such as boat wakes. Chevron patterns were the most effective at reducing the time the shoreline spent above the sediment’s and reducing high-stress areas between units. In addition, overlapping patterns appeared to reduce bed stress more than non-overlapping patterns, indicating that a slight overlap may be advantageous for blocking flow. In the context of practical engineering applications, this is the most important finding from this study. Results suggest that prior to installing a structure like a POSH unit cluster, the predominant incoming wave angle should be considered first, and the structures’ orientations should be engineered to be as close to perpendicular to this angle as possible. Doing so will reduce cost (fewer units needed) while increasing effectiveness of the installation. Or, at minimum, results suggest that short of wave angle information, an overlapping configuration will provide more benefit than a configuration with no overlaps.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Turner, R.E. Landscape Development and Coastal Wetland Losses in the Northern Gulf of Mexico. Am. Zool. 1990, 30, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridge, J.T.; Rodriguez, A.B.; Fodrie, F.J. Evidence of Exceptional Oyster-reef Resilience to Fluctuations in Sea Level. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 10409–10420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.W.; Brumbaugh, R.D.; Airoldi, L.; Carranza, A.; Coen, L.D.; Crawford, C.; Defeo, O.; Edgar, G.J.; Hancock, B.; Kay, M.C.; et al. Oyster Reefs at Risk and Recommendations for Conservation, Restoration, and Management. Bioscience 2011, 61, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennish, M.J. Coastal Salt Marsh Systems in the U.S.: A Review of Anthropogenic Impacts. J. Coast. Res. 2001, 17, 731–748. [Google Scholar]

- Radabaugh, K.R.; Powell, C.E.; Moyer, R.P. Coastal Habitat Integrated Mapping and Monitoring Program Report for the State of Florida; Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission: Tallahassee, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Forlini, C.; Qayyum, R.; Malej, M.; Lam, M.Y.-H.; Shi, F.; Angelini, C.; Sheremet, A. On the Problem of Modeling the Boat Wake Climate: The Florida Intracoastal Waterway. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2021, 126, e2020JC016676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, D.J.; Roland, R.; Douglass, S.L. Preliminary Evaluation of Critical Wave Energy Thresholds at Natural and Created Coastal Wetlands; WRP Technical Notes Collection (ERDC TN-WRP-HS-CP-2.2); US Army Engineer Research and Development Center: Vicksburg, MS, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Waggoner, J. Comparison between Pervious Oyster Shell Habitat (POSH) Unit and Reef Ball Performance along an Eroding Shoreline in Northeast Florida. Master’s Thesis, University of North Florida, Jacksonville, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gittman, R.K.; Scyphers, S.B.; Smith, C.S.; Neylan, I.P.; Grabowski, J.H. Ecological Consequences of Shoreline Hardening: A Meta-Analysis. Bioscience 2016, 66, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilkovic, D.M.; Mitchell, M.M.; La Peyre, M.K.; Toft, J.D. (Eds.) Living Shorelines; Series: Marine; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.S.N.; Walles, B.; Sharifuzzaman, S.; Shahadat Hossain, M.; Ysebaert, T.; Smaal, A.C. Oyster Breakwater Reefs Promote Adjacent Mudflat Stability and Salt Marsh Growth in a Monsoon Dominated Subtropical Coast. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.L.; Bilkovic, D.M.; Boswell, M.K.; Bushek, D.; Cebrian, J.; Goff, J.; Kibler, K.M.; La Peyre, M.K.; McClenachan, G.; Moody, J.; et al. The Application of Oyster Reefs in Shoreline Protection: Are We Over-engineering for an Ecosystem Engineer? J. Appl. Ecol. 2019, 56, 1703–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.S.N.; La Peyre, M.; Coen, L.D.; Morris, R.L.; Luckenbach, M.W.; Ysebaert, T.; Walles, B.; Smaal, A.C. Ecological Engineering with Oysters Enhances Coastal Resilience Efforts. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 169, 106320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.L.; La Peyre, M.K.; Webb, B.M.; Marshall, D.A.; Bilkovic, D.M.; Cebrian, J.; McClenachan, G.; Kibler, K.M.; Walters, L.J.; Bushek, D.; et al. Large-Scale Variation in Wave Attenuation of Oyster Reef Living Shorelines and the Influence of Inundation Duration. Ecol. Appl. 2021, 31, e02382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theuerkauf, S.J.; Burke, R.P.; Lipcius, R.N. Settlement, Growth, and Survival of Eastern Oysters on Alternative Reef Substrates. J. Shellfish. Res. 2015, 34, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.J.; Smith, K.J.; Hargis, C.W. Development of Pervious Oyster Shell Habitat (POSH) Concrete for Reef Restoration and Living Shorelines. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 295, 123685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, L.; Waggoner, J.; Mathews, H.; Smith Kelly, J.; Crowley, R. Effectiveness of Pervious Oyster Shell Habitat (POSH) Units at Reducing Shoreline Bed Stress and Erosion. In Proceedings of the Coastal Sediments, New Orleans, LA, USA, 11–15 April 2023; pp. 2048–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, L.; Waggoner, J.; Mathews, H.; Smith, K.J.; Crowley, R. Analysis of Pervious Oyster Shell Habitat (POSH) Unit Effectiveness Using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) and Field Observations. In Proceedings of the Geo-Congress 2023, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 26–29 March 2023; pp. 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemu, M.; Roster, M.; Cope, L.; Waggoner, J.; Crowley, R.; Richardson, R. A Method for Small-Scale Field Sediment Transport Investigation around Low-Crested Oyster-Based Structures along the Fort George River. Shore Beach 2024, 93, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, H.; Uddin, M.J.; Hargis, C.W.; Smith, K.J. First-Year Performance of the Pervious Oyster Shell Habitat (POSH) along Two Energetic Shorelines in Northeast Florida. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, L.; Mathews, H.; Shemu, M.; Roster, M.; Jeong, J.; Waggoner, J.; Smith, K.J.; Crowley, R.; Baynard, C.; Richardson, R. Enhanced Analysis of Pervious Oyster Shell Habitat (POSH) Units’ Performance for Reducing Bed Stress and Mitigating Shoreline Erosion. In Proceedings of the Geo-Congress 2024, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 25–28 February 2024; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2024; pp. 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, B.M.; Allen, R. Wave Transmission through Artificial Reef Breakwaters. In Proceedings of the Coastal Structures and Solutions to Coastal Disasters 2015, Boston, MA, USA, 9–11 September 2015; pp. 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.J.; Webb, B.M. Determination of Wave Transmission Coefficients for Oyster Shell Bag Breakwaters. In Proceedings of the Coastal Engineering Practice (2011), San Diego, CA, USA, 21–24 August 2011; pp. 684–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvin, J. Wave Attenuation by Constructed Oyster Reef Breakwaters. Master’s Thesis, Agricultural and Mechanical College, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiberg, P.L.; Taube, S.R.; Ferguson, A.E.; Kremer, M.R.; Reidenbach, M.A. Wave Attenuation by Oyster Reefs in Shallow Coastal Bays. Estuaries Coasts 2019, 42, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styles, R. Flow and Turbulence over an Oyster Reef. J. Coast. Res. 2015, 314, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsikoudis, V.; Kibler, K.M.; Walters, L.J. In-Situ Measurements of Turbulent Flow over Intertidal Natural and Degraded Oyster Reefs in an Estuarine Lagoon. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 143, 105688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simcenter STAR-CCM+; Version 2021.1.1; Siemens Industries Digital Software; Siemens: Munich, Germany, 2021.

- Google Earth Pro; version 7.3; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2018.

- Google Earth Pro; version 7.3; Landsat/Copernicus Imagery; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2019.

- Baillie, C.J.; Grabowski, J.H. Factors Affecting Recruitment, Growth and Survival of the Eastern Oyster Crassostrea Virginica across an Intertidal Elevation Gradient in Southern New England. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2019, 609, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proffitt, C.E.; Travis, S.E.; Edwards, K.R. Genotype and elevation influence spartina alterniflora colonization and growth in a created salt marsh. Ecol. Appl. 2003, 13, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, A. Application of Similarity Principles and Turbulence Research to Bed-Load Movement (Translated from German); Soil Conservation Service Cooperative Laboratory, California Institute of Technology: Pasadena, CA, USA, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Spiering, D.W.; Kibler, K.M.; Kitsikoudis, V.; Donnelly, M.J.; Walters, L.J. Detecting Hydrodynamic Changes after Living Shoreline Restoration and through an Extreme Event Using a Before-After-Control-Impact Experiment. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 169, 106306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manis, J.E.; Garvis, S.K.; Jachec, S.M.; Walters, L.J. Wave Attenuation Experiments over Living Shorelines over Time: A Wave Tank Study to Assess Recreational Boating Pressures. J. Coast. Conserv. 2015, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maza, M.; Lara, J.L.; Losada, I.J. Tsunami Wave Interaction with Mangrove Forests: A 3-D Numerical Approach. Coast. Eng. 2015, 98, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslov, D.; Johnson, J.; Pereira, E.; Duarte, D.; Miranda, T.; Lima, M.; Cruz, F.; Valente, I.; Pinheiro, M. Experimental Testing and CFD Modelling for Prototype Design of Innovative Artificial Reef Structures. In OCEANS 2019—Marseille; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androulakis, D.N.; Dounas, C.G.; Banks, A.C.; Magoulas, A.N.; Margaris, D.P. An Assessment of Computational Fluid Dynamics as a Tool to Aid the Design of the HCMR-Artificial-ReefsTM Diving Oasis in the Underwater Biotechnological Park of Crete. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.; Pinho, J.L.S.; Valente, T.; Antunes do Carmo, J.S.; Hegde, A.V. Performance Assessment of a Semi-Circular Breakwater through CFD Modelling. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revopoint. RevoScan 4.0.0.227a; Revopoint 3D Technologies Inc. Available online: https://www.revopoint3d.com/download/ (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Nicoud, F.; Ducros, F. Subgrid-Scale Stress Modeling Based on Teh Square of the Velocity Gradient Tensor. Flow. Turbul. Combust. 1999, 62, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, R.M.; Weggel, J.R. Development of ship wave design information. Coast. Eng. Proc. 1984, 19, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, R.G.; Broder, A.E.; Goodrich, M.S.; Donaldson, D.G. Model Tests of the Proposed P.E.P. Reef Installation at Vero Beach, Florida; Gainesville, FL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Everett, C.L.; Williams, O.; Ruggiero, E.; Larner, M.; Schaefer, R.; Malej, M.; Shi, F.; Bruck, J.; Puleo, J.A. Ship Wake Forcing and Performance of a Living Shoreline Segment on an Estuarine Shoreline. Front. Built Environ. 2022, 8, 917945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, R.; Turner, I.L. Shoreline Response to Submerged Structures: A Review. Coast. Eng. 2006, 53, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdravkovich, M.M. Flow Around Circular Cylinders: A Comprehensive Guide Through Flow Phenomena, Experiments, Applications, Mathematical Models, and Computer Simulations; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Zdravkovich, M.M. Flow Around Circular Cylinders: A Comprehensive Guide Through Flow Phenomena, Experiments, Applications, Mathematical Models, and Computer Simulations. Vol. 2, [Applications]; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Polk, M.A.; Eulie, D.O. Effectiveness of Living Shorelines as an Erosion Control Method in North Carolina. Estuaries Coasts 2018, 41, 2212–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijón Mancheño, A.; Jansen, W.; Uijttewaal, W.S.J.; Reniers, A.J.H.M.; van Rooijen, A.A.; Suzuki, T.; Etminan, V.; Winterwerp, J.C. Wave Transmission and Drag Coefficients through Dense Cylinder Arrays: Implications for Designing Structures for Mangrove Restoration. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 165, 106231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armono, H.D.; Manurung, A.; Sujantoko; Ketut Suastika, I. Wave Transmission Model over Hexagonal Artificial Reefs Using DualSPHysics. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1095, 12025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time (s) | Amplitude (m) |

|---|---|

| 0–2 | 0.03 |

| 2–4 | 0.04 |

| 4–6 | 0.045 |

| 6–8 | 0.04 |

| 8–10 | 0.075 |

| 10–12 | 0.065 |

| 12–14 | 0.08 |

| 14–16 | 0.105 |

| 16–18 | 0.09 |

| 18–20 | 0.05 |

| 20–22 | 0.04 |

| 22–24 | 0.03 |

| 24–26 | 0.01 |

| >26 | 0 |

| Probe | Case A | Case PN | Case PO | Case CN | Case CO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probe 1 | 0.34 | 0.20 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.22 |

| Probe 2 | 0.28 | 0.65 | 0.54 | 0.59 | 0.38 |

| Probe 3 | 0.57 | 1.37 | 0.75 | 0.64 | 0.46 |

| Probe 4 | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.22 | 0.50 |

| Probe 5 | 0.42 | 0.32 | 0.46 | 0.38 | 0.63 |

| Probe 6 | 0.98 | 1.06 | 0.82 | 0.45 | 0.57 |

| Probe 7 | 0.40 | 0.47 | 0.43 | 0.26 | 0.41 |

| Probe 8 | 0.18 | 0.65 | 0.44 | 0.51 | 0.45 |

| Probe 9 | 0.56 | 0.83 | 0.44 | 0.57 | 0.23 |

| Probe | Case A | Case PN | Case PO | Case CN | Case CO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probe 1 | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.18 |

| Probe 2 | 0.16 | 0.43 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.26 |

| Probe 3 | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.28 |

| Probe 4 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.22 |

| Probe 5 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.26 | 0.15 | 0.37 |

| Probe 6 | 0.29 | 0.49 | 0.33 | 0.22 | 0.18 |

| Probe 7 | 0.34 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.21 | 0.28 |

| Probe 8 | 0.12 | 0.37 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.23 |

| Probe 9 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.13 |

| Probe | Case A | Case PN | Case PO | Case CN | Case CO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probe 1 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.12 |

| Probe 2 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.11 |

| Probe 3 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| Probe 4 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.12 |

| Probe 5 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.20 |

| Probe 6 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.09 |

| Probe 7 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.14 |

| Probe 8 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.25 | 0.12 |

| Probe 9 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.07 |

| Probe | Case A | Case PN | Case PO | Case CN | Case CO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probe 1 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| Probe 2 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.06 |

| Probe 3 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Probe 4 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Probe 5 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.12 |

| Probe 6 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| Probe 7 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.05 |

| Probe 8 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.04 |

| Probe 9 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| Probe | Case A | Case PN | Case PO | Case CN | Case CO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probe 1 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| Probe 2 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.08 |

| Probe 3 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.09 |

| Probe 4 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| Probe 5 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.14 |

| Probe 6 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| Probe 7 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| Probe 8 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.07 |

| Probe 9 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cope, L.; Waggoner, J.; Crowley, R.; Shemu, M.; Roster, M.; Jeong, J.; Mathews, H.; Smith, K.J.; Uddin, M.J.; Hargis, C. Modeled Bed Stress Patterns Around Pervious Oyster Shell Habitat Units Using Large-Eddy Simulations. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11129. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411129

Cope L, Waggoner J, Crowley R, Shemu M, Roster M, Jeong J, Mathews H, Smith KJ, Uddin MJ, Hargis C. Modeled Bed Stress Patterns Around Pervious Oyster Shell Habitat Units Using Large-Eddy Simulations. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11129. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411129

Chicago/Turabian StyleCope, Lauren, Jacob Waggoner, Raphael Crowley, Makaya Shemu, Michael Roster, Junyoung Jeong, Hunter Mathews, Kelly J. Smith, Mohammad J. Uddin, and Craig Hargis. 2025. "Modeled Bed Stress Patterns Around Pervious Oyster Shell Habitat Units Using Large-Eddy Simulations" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11129. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411129

APA StyleCope, L., Waggoner, J., Crowley, R., Shemu, M., Roster, M., Jeong, J., Mathews, H., Smith, K. J., Uddin, M. J., & Hargis, C. (2025). Modeled Bed Stress Patterns Around Pervious Oyster Shell Habitat Units Using Large-Eddy Simulations. Sustainability, 17(24), 11129. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411129