Municipal-Level Analysis of Peer Effects in China’s Sustainable Rural Development: Mechanisms and Imitation Patterns

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Hypothesis

2.1. Hypothesis on the Existence of Peer Effects in Rural Sustainable Development

2.2. The Mechanisms of Peer Effects in Rural Sustainable Development

3. Sample Selection and Model Specification

3.1. Sample Selection

3.1.1. Rural Sustainable Development Level

- Prosperous industries are crucial foundations for building a modern economic system in rural areas. This requires continuously strengthening the agricultural production capacity foundation, accelerating the upgrading of agricultural production efficiency, and enhancing the level of industrial integration. These efforts will advance the pace of agricultural modernization and reinforce agriculture’s foundational role in the national economy.

- Livable ecology is a key initiative in creating a “Beautiful China” and a priority task in comprehensively advancing rural sustainable development. The Chinese government has clearly stated that beautiful villages with ecological livability should be developed by promoting Green development in agriculture, continuously improving rural living environments, and strengthening rural ecological conservation.

- Civilized rural customs as a vital safeguard for modern civilization and constitute a sound cultural and institutional foundation. Generally, higher educational attainment of farmers greater progress in rural ideological and ethical development. Furthermore, transmission of traditional culture should be leveraged to disseminate civilized values and cultivate a harmonious rural ethos, thereby continuously elevating the overall level of civility in rural communities. It is also essential to vigorously develop rural public cultural services in rural areas, enhance the comprehensive quality of farmers, and promote harmonious coexistence among rural residents.

- Effective governance serves as a crucial safeguard for political development and the social foundation for sustainable rural progress. The Chinese government emphasizes the need to strengthen governance capabilities and governance initiatives, gradually establishing a rural governance system that integrates the rule of law, moral governance, and self-governance.

- Affluent life is an essential requirement of socialism and the fundamental goal of sustainable rural development. We must continuously raise farmers’ income levels and expand their income channels; improve farmers’ consumption structure and farmers’ living conditions to enhance the quality of life in areas such as clothing, food, housing, and transportation; strengthen rural infrastructure development level and improve the basic public service coverage level to enhance farmers’ sense of happiness and fulfillment, thereby progressively achieving common prosperity.

3.1.2. Control Variables

3.1.3. Definition of Peer Regions

3.1.4. Data Sources and Variable Description

3.2. Model Specification

- Endogenous effects occur when the rural sustainable development levels of peer regions directly influence the rural sustainable development level of the focal region.

- Exogenous effects occur when the focal region’s rural sustainable development outcome is affected by other characteristics of peer regions, such as economic development or urbanization levels.

- Correlated effects occur if the focal region and its peers share similar underlying traits, institutional environments, or face common systemic shocks. This may lead to omitted variable bias.

4. Analysis of Results

4.1. Baseline Regression Results

4.2. Robustness Tests Results

- In peer effects research, the average or median values are commonly used to represent peer influence. In this study’s baseline regression, the mean rural sustainable development level of peer regions is used as the proxy; however, for the robustness test, the mean is replaced with the median rural sustainable development level of peer regions. The results in Table 4, Column (1) remain positive and statistically significant, which is consistent with the baseline findings.

- Outliers or extreme values can distort the data distribution and potentially bias the results. To address this, all continuous variables are winsorized at the 1% and 99% quantiles. The regression results in Table 4, Column (2) remain positively significant. This confirms the robustness of the baseline estimates.

- Provincial capital regions differ from ordinary prefecture-level regions in terms of administrative status, economic functions, and resource endowments; this is particularly true with respect to policy resource allocation, transportation infrastructure, and concentration of educational resources. Provincial capitals may have a siphoning effect on surrounding areas; as such, they are excluded from the sample to make the sample more homogeneous and increase estimation accuracy. The empirical results in Table 4, Column (3) confirm that the peer effects remain positive and significant after this exclusion. This supports the robustness of the main findings.

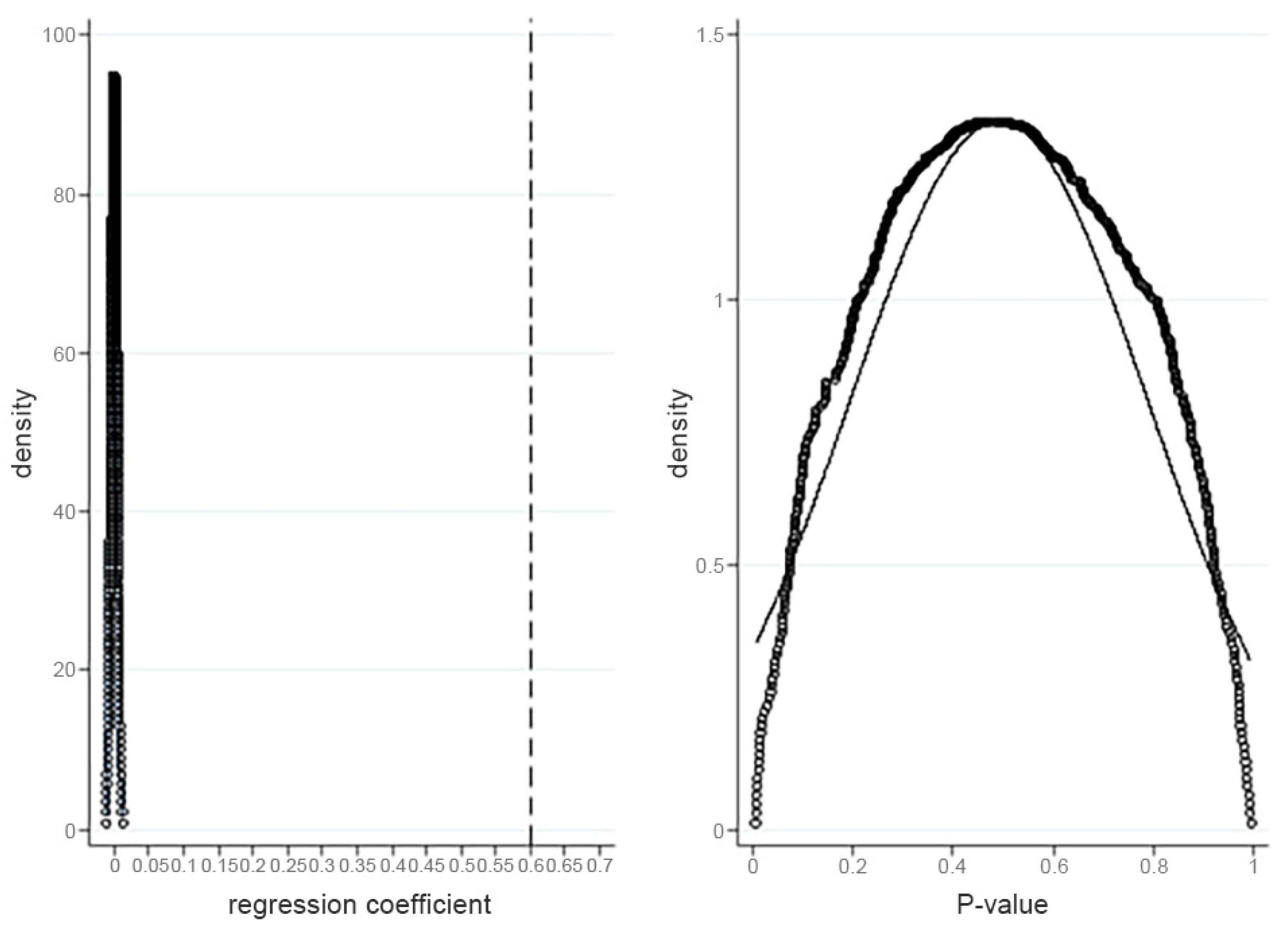

- Placebo test. Rural sustainable development may be influenced by unobserved factors. As such, a placebo test is conducted to assess the robustness of the baseline regression results. Specifically, if unobserved common factors drive the baseline results, the peer effects should remain significant, even when peer regions are randomly reassigned to focal regions. Given this, the mean rural sustainable development level of peer regions is randomly shuffled among all sample regions, and 500 simulation iterations are performed. Figure 1 shows that the distribution of the regression coefficients is centered around zero and follows a normal distribution, and all absolute values are smaller than the baseline coefficient. This indicates that the randomly assigned peer effects are not statistically significant. This eliminates the possibility that unobserved common factors drive the baseline results and confirms the robustness of the spatial association effect in local rural sustainable development levels.

- 5.

- Instrumental variable approach. To mitigate correlated effects, this study applies Zuo et al. [61]: the instrumental variable (IV) assessing the peer effects in rural sustainable development is defined as the average proportion of villages within the same province where the roles of village director and party secretary are concurrently held by the same individual. One person serving the dual role of village director and party secretary reflects grassroots governance efficiency; this impacts the effectiveness of rural sustainable development implementation within a locality. However, this variable is unlikely to directly influence rural sustainable development outcomes in other regions. As such, it satisfies the relevance and exclusion criteria of a valid instrument. The test results are presented in Table 4, Column (4). The LM test strongly rejects the null hypothesis of under-identification, and the Wald F-statistic significantly exceeds the conventional weak instrument critical value of 16.38 at the 10% significance level. This rejects the weak instrument hypothesis. The second-stage regression coefficient is 0.621 and is significant at the 1% level. This indicates that after controlling for endogeneity, the regional peer effects in rural sustainable development remain robust. This provides strong evidence for the validity of the baseline regression results.

4.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.3.1. Geographical Heterogeneity

4.3.2. Temporal Heterogeneity

4.4. Mechanism Analysis

4.4.1. Learning-Based Imitation

4.4.2. Competitive Imitation

- Assessment Pressure: GDP growth remains a central indicator for evaluating economic performance and official promotion prospects. To reflect assessment pressure specifically related to rural sustainable development, this study uses the growth rate of the total agricultural output value (GAGDP) as a proxy for governmental performance in this domain.

- Implicit Competitive Pressure: Government expenditure on agriculture, forestry, and water affairs (AFW) encompasses fiscal investments in agricultural modernization, forestry, water conservancy, poverty alleviation, and rural institutional reforms. Higher AFW spending is interpreted as reflecting greater governmental attention and resource commitment to rural development, thereby serving as an indicator of implicit competitive pressure.

5. Additional Analysis: Imitation Patterns

5.1. Redefining Peer Groups Based on Economic Structure

5.2. Redefining Peer Groups Based on Geographic Proximity

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

- There are significant peer effects with respect to China’s rural sustainable development. After a series of robustness checks, the results remain robust, indicating that local governments do not promote rural sustainable development in isolation; rather, they tend to imitate other regions.

- Heterogeneity analyses reveal that the peer effects are significant in China’s central and western regions, but not in the eastern region. The effect before the year 2017, when the national Rural Revitalization Strategy was officially introduced, was greater than that after.

- A mechanism analysis shows that both learning-based imitation and competitive imitation are important drivers of the peer effects. However, a region’s specific rural sustainable development experience does not inhibit its imitation behavior. Regions with higher economic development levels are more likely to become imitation targets. Government officials’ performance pressures and inter-regional competition further promote the peer effects.

- The redefinition analysis of peer groups indicates that in the rural sustainable development process, local governments primarily imitate regions within the same province that share similar economic structures and geographic proximity.

- Given the confirmed existence of peer effects, the central government should actively leverage and refine them to transform spontaneous imitation into an efficient and organized network for learning and innovation. This can be achieved by constructing a systematic national-level information and incentive platform, which would include a dynamically updated “Case Database for Sustainable Rural Development” to reduce learning costs for local governments. Incentives should also be provided to both widely emulated “front-runner” regions and “follower” regions that successfully implement localized innovations, thereby fostering a positive reinforcement cycle.

- In light of the observed heterogeneity, differentiated rural development strategies should be promoted. At the technical level, a diagnostic mechanism should be established to identify local comparative advantages, using tools such as the “Rural Development Suitability Assessment” to map local natural and cultural assets. This process will inform the long-term planning of sustainable rural development initiatives. At the institutional level, relevant government agencies should issue differentiated implementation guidelines. Eastern regions could prioritize rural innovation, for example, by fostering creative industries through digital technologies. Central and western regions should formulate resource-adaptive pathways, such as enhancing distinctive local agriculture or developing rural tourism, instead of mechanically replicating coastal models.

- Considering the results on imitation mechanisms, the performance evaluation system should be improved to guide healthy intergovernmental competition. First, within the assessment framework for grassroots leadership, indicators such as ecological livability, cultural vibrancy, and resident satisfaction should be incorporated, while reducing the relative weight of agricultural GDP growth. A multidimensional evaluation framework would help direct officials’ attention to the comprehensive development of rural areas. Second, to avoid extensive development driven by output-oriented singular subsidies, targeted financial support should be provided for local innovation. This could include establishing special funds to support research in distinctive and sustainable rural industries.

- Following the redefinition results of the peer group, provincial-level demonstration cities should be developed. First, each province should identify and certify demonstration cities for sustainable rural development by category, for example, establishing emonstrations in sectors such as “agriculture-led,” “tourism-led,” and “industry-integration-led.” This will ensure the availability of provincial benchmarks. Second, a provincial-level exchange mechanism for sustainable rural development should be established. This mechanism would involve regularly organizing paired exchanges, including study visits, training sessions, official rotations, and joint projects, among cities with similar economic structures and geographical proximity, thereby facilitating effective learning for less-developed areas.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burja, C.; Burja, V. Sustainable Development of Rural Areas: A Challenge for Romania. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2014, 13, 1861–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pe’er, G.; Bonn, A.; Bruelheide, H.; Dieker, P.; Eisenhauer, N.; Feindt, P.H.; Hagedorn, G.; Hansjürgens, B.; Herzon, I.; Lomba, Â. Action Needed for the Eu Common Agricultural Policy to Address Sustainability Challenges. People Nat. 2020, 2, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, A.P.; Prokopy, L.S. Farmer Participation in U.S. Farm Bill Conservation Programs. Environ. Manag. 2014, 53, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostyukov, A.V.; Pritula, O.D.; Davydova, S.G. Regional Aspects of Integrated Development of Rural Areas. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 852, 012053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawchenko, T.; Hayes, B.; Foster, K.; Markey, S. What Are Contemporary Rural Development Policies? A Pan-Canadian Content Analysis of Government Strategies, Plans, and Programs for Rural Areas. Can. Public Policy 2023, 49, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Peng, R. Effectiveness Test of Rural Revitalization Demonstration Policy on Rural Economic Development in China: Analysis of Did Based on the Data of Henan Province in China. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 21582440241242539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, I.; Nunes, J.; Mesias, F. Can Rural Development Be Measured? Design and Application of a Synthetic Index to Portuguese Municipalities. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 145, 1107–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duletić, R.; Đurić, K.; Tomaš-Simin, M. Ecotourism as a Factor of Sustainable Rural Development. J. Agron. Technol. Eng. Manag. 2024, 7, 1271–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabet, N.S.; Khaksar, S. The Performance of Local Government, Social Capital and Participation of Villagers in Sustainable Rural Development. Soc. Sci. J. 2024, 61, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winston, G.C.; Zimmerman, D.J. Peer Effects in Higher Education. In College Choices: The Economics of Where to Go, When to Go, and How to Pay for It; Discussion Paper; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ahern, K.R.; Duchin, R.; Shumway, T. Peer Effects in Risk Aversion and Trust. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2014, 27, 3213–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhao, G.; Yao, L. Peer Effects and Rural Households’ Online Shopping Behavior: Evidence from China. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Wang, Q. The Peer Effect of Corporate Financial Decisions around Split Share Structure Reform in China. Rev. Financ. Econ. 2020, 38, 474–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, W.; Yu, L.; Zhang, J. Peer Effects in Digital Inclusive Finance Participation Decisions: Evidence from Rural China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 208, 123645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; He, Q.; Fu, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, G. Peer Effects on Corporate Social Responsibility Engagement of Chinese Construction Firms through Board Interlocking Ties. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024, 150, 04024064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N. Economic Policy Uncertainty, Managerial Ability, and the Peer Effect of Corporate Investment. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 8231201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, T. Peer Effects of Enterprise Green Financing Behavior: Evidence from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1033868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Liang, H.; Zhan, X. Peer Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility. Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 5487–5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, R.; Yao, P.; Zhang, J. Assessing Chinese Governance Low-Carbon Economic Peer Effects in Local Government and under Sustainable Environmental Regulation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 61304–61323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhou, W.C. Peer Effects in Outward Foreign Direct Investment: Evidence from China. Manag. Decis. 2020, 58, 705–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, W. Research on Territorial Spatial Development Non-Equilibrium and Temporal–Spatial Patterns from a Conjugate Perspective: Evidence from Chinese Provincial Panel Data. Land 2024, 13, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Xiong, C. Peer Effects in Local Government Decision-Making: Evidence from Urban Environmental Regulation. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 85, 104066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Liu, L.; Chen, L. Rural Revitalization of China: A New Framework, Measurement and Forecast. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2023, 89, 101696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, A.; Chen, C.; Ao, Y.; Zhou, W. Measuring the Inclusive Growth of Rural Areas in China. Appl. Econ. 2022, 54, 3695–3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.; Zhai, B.; Yang, Y. The Realization Logic of Rural Revitalization: Coupled Coordination Analysis of Development and Governance. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0305593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J. How to Promote Rural Revitalization Via Introducing Skilled Labor, Deepening Land Reform and Facilitating Investment? China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2020, 12, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, E.; Li, J.; Li, X. Sustainable Development of Education in Rural Areas for Rural Revitalization in China: A Comprehensive Policy Circle Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhong, M.; Dong, Y. Digital Finance and Rural Revitalization: Empirical Test and Mechanism Discussion. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 201, 123248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Yang, Y.; Wang, L. Driving Rural Industry Revitalization in the Digital Economy Era: Exploring Strategies and Pathways in China. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Liu, Q.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Khanal, R. How the Rural Digital Economy Drives Rural Industrial Revitalization—Case Study of China’s 30 Provinces. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, M.; Qiong, H. Research on the Rural Revitalization Process Driven by Human Capital: Based on Farmers’ Professionalization Perspective. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 21582440241249252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, B.; Liu, S. Impact of Fiscal Poverty Alleviation Funds on Poverty Mitigation and Economic Expansion: Evidence from Provincial Panel Data in China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2024, 17, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.-S.; Kuang, X.; Klein, T. Does the Urban–Rural Income Gap Matter for Rural Energy Poverty? Energy Policy 2024, 186, 113977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, S. The Road to Common Prosperity: Can the Digital Countryside Construction Increase Household Income? Sustainability 2023, 15, 4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Qiao, Y.; Yao, R. What Promote Farmers to Adopt Green Agricultural Fertilizers? Evidence from 8 Provinces in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 426, 139123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-p.; Fu, B.-j.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, K.-b.; Zhao, M.M.; Ma, J.-f.; Wu, J.-H.; Xu, C.; Liu, W.-g.; Wang, H. Sustainable Development in the Yellow River Basin: Issues and strategies. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Xia, Q.; Zha, L. Urban Infrastructure Development in China: A Multi-Dimensional Spatial Peer Effect Perspective. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2025, 18, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Institutional Interaction and Decision Making in China’s Rural Development. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 76, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xing, S. How Could Local Environmental Innovations Become a National Policy?—A Qualitative Comparative Study on the Factors Influencing the Diffusion of Bottom-up Environmental Policy Innovations. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0325811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.-G.; Li, T.; Feng, T.-T. On the Synergy in the Sustainable Development of Cultural Landscape in Traditional Villages under the Measure of Balanced Development Index: Case Study of the Zhejiang Province. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, D. The Role of Grass-Roots Cadres in the Construction of All-Round Rural Revitalization. In Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference on Humanities Education and Social Sciences (ICHESS 2024), Ningbo, China, 11–13 October 2024; pp. 863–875. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M. Research on the Coordinated Co-Governance of Rural Grassroots Multi-Subjects under the Background of Rural Revitalization Strategy. J. Humanit. Arts Soc. Sci. 2022, 6, 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ge, D.; Sun, P.; Sun, D. The Transition Mechanism and Revitalization Path of Rural Industrial Land from a Spatial Governance Perspective: The Case of Shunde District, China. Land 2021, 10, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, W. Research on the Role of Digital Economy in Promoting Rural Revitalization: A Study from the Perspective of Industrial Agglomeration. Adv. Manag. Intell. Technol. 2025, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryanto, Y.; Anwarudin, O.; Yuniarti, W. Progressive Farmers as Catalysts for Regeneration in Rural Areas through Farmer to Farmer Extension Approach. Plant Arch. 2021, 21, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. Research on the Mechanism of the Benefit Linkage of the Whole Chain Linking Farmers with Farmers under the Background of Rural Revitalization. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Social Sciences and Big Data Application (ICSSBDA 2021), Xi’an, China, 10–12 December 2021; pp. 199–206. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wu, G.; Huang, X.; Sun, D.; Song, Z. Peer Effects of Corporate Product Quality Information Disclosure: Learning and Competition. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2023, 88, 101824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Payne, D.; Kinsella, S. Peer Effects in the Diffusion of Innovations: Theory and Simulation. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2016, 63, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Ye, A. Direct Imitation or Indirect Reference?—Research on Peer Effects of Enterprises’ Green Innovation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 41028–41044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Z.; Lian, Y.; Forson, J.A. Peer Effects in R&D Investment Policy: Evidence from China. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 26, 4516–4533. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, K.-Y.; Tsai, W.; Chen, M.-J. If They Can Do It, Why Not Us? Competitors as Reference Points for Justifying Escalation of Commitment. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jin, T.; Meng, X. From Race-to-the-Bottom to Strategic Imitation: How Does Political Competition Impact the Environmental Enforcement of Local Governments in China? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 25675–25688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Li, X.; Shen, Y. Indicator System Construction and Empirical Analysis for the Strategy of Rural Vitalization. Financ. Econ 2018, 11, 70–82. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, P.; Chen, H.; Lai, M.; Zhao, S. The Dynamics and Driving Mechanisms of Rural Revitalization in Western China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Yang, X. Sustainable Development Levels and Influence Factors in Rural China Based on Rural Revitalization Strategy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.T.; Roberts, M.R. Do Peer Firms Affect Corporate Financial Policy? J. Financ. 2014, 69, 139–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manski, C.F. Identification of Endogenous Social Effects: The Reflection Problem. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1993, 60, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Pan, Y.; Wu, R.; Feng, Y. Peer Effects of Environmental Regulation on Sulfur Dioxide Emission Intensity: Empirical Evidence from China. Energy Environ. 2025, 36, 1871–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, A.; Bergquist, M.; Schultz, W.P. Spillover Effects in Environmental Behaviors, across Time and Context: A Review and Research Agenda. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 573–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stastna, L. Spatial Interdependence of Local Public Expenditures: Selected Evidence from the Czech Republic. Czech Econ. Rev. 2009, 3, 7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, Y.; Yang, C.; Xin, G.; Wu, Y.; Chen, R. Driving Mechanism of Comprehensive Land Consolidation on Urban–Rural Development Elements Integration. Land 2023, 12, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.C. China’s Eleventh Five-Year Plan (2006–2010): From” Getting Rich First” to” Common Prosperity”. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2006, 47, 708–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q. China Develops Its West: Motivation, Strategy and Prospect. J. Contemp. China 2004, 13, 611–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijk, M.P. A Different Development Model in China’s Western and Eastern Provinces? Mod. Econ. Online 2011, 2, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, N.; Li, J.; Yan, Y. Sustainable Rural Development: Differentiated Paths to Achieve Rural Revitalization with Case of Western China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.-J.; Wu, D.-F.; Zhu, M.-J.; Ma, P.-F.; Li, Z.-C.; Liang, Y.-X. Regional Differences in the Quality of Rural Development in Guangdong Province and Influencing Factors. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Tao, R.; Xi, L.; Li, M. Local Officials’ Incentives and China’s Economic Growth: Tournament Thesis Reexamined and Alternative Explanatory Framework. China World Econ. 2012, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Tang, J.; Wan, J.; Chen, Y. Promotion Incentives for Local Officials and the Expansion of Urban Construction Land in China: Using the Yangtze River Delta as a Case Study. Land Use Policy 2017, 63, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wang, H.; Wang, X. Innovation Like China: Evidence from Chinese Local Officials’ Promotions. China Econ. Rev. 2024, 86, 102203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeSage, J.P. The Theory and Practice of Spatial Econometrics; University of Toledo: Toledo, OH, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

| Target Variable | Primary Indicators | Secondary Indicators | Specific Indicators | Influence Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural Sustainable Development | Prosperous industries | Agricultural production capacity foundation | Total agricultural machinery power per capita | + |

| Comprehensive grain production capacity | + | |||

| Agricultural production efficiency | Agricultural labor productivity (primary industry output/GDP per capita) | + | ||

| Level of industrial integration | Main business income of large-scale agricultural product processing enterprises | + | ||

| Livable ecology | Green development in agriculture | Intensity of pesticide and fertilizer use | - | |

| Utilization rate of livestock and poultry manure | + | |||

| Rural living environments | Proportion of administrative villages with domestic sewage treatment | + | ||

| Proportion of administrative villages with domestic waste treatment | + | |||

| Rural sanitary toilet coverage rate | + | |||

| Rural ecological conservation | Rural greening coverage rate | + | ||

| Civilized rural customs | Educational attainment of farmers | Proportion of rural household expenditure on education, culture, and entertainment | + | |

| Proportion of qualified teachers in rural compulsory education schools with bachelor’s degrees or above | + | |||

| Average years of schooling among rural residents | + | |||

| Transmission of traditional culture | Comprehensive population coverage of television programming | + | ||

| Proportion of administrative villages with internet broadband access | + | |||

| Rural public cultural development | Number of rural cultural stations | + | ||

| Effective governance | Governance capabilities | Proportion of villages where the same person holds village chief and Party secretary positions | + | |

| Governance initiatives | Proportion of administrative villages with completed village planning | + | ||

| Proportion of administrative villages where village revitalization projects have been implemented | + | |||

| Affluent life | Farmers’ income levels | Per capita net income of farmers | + | |

| Growth rate of per capita rural income | + | |||

| Urban–rural income ratio | - | |||

| Rural poverty incidence rate | - | |||

| Farmers’ consumption structure | Engel coefficient of rural residents | - | ||

| Farmers’ living conditions | Number of cars per 100 households | + | ||

| Per capita housing area of rural residents | + | |||

| Infrastructure development level | Village road hardening rate | + | ||

| Basic public service coverage level | Number of health technicians per 1000 rural residents | + |

| Variable Name | Variable Symbol | Observations | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural Sustainable Development Level | Rural | 3288 | 0.355 | 0.132 | 0.021 | 0.935 |

| Rural Sustainable Development Level in Peer Regions | 3288 | 0.355 | 0.122 | 0.044 | 0.547 | |

| Urbanization Rate | Urban | 3288 | 0.563 | 0.148 | 0.182 | 1 |

| Industrial Structure | Ind | 3288 | 42.578 | 9.586 | 14.36 | 80.49 |

| Level of Economic Development | GDP | 3288 | 2.598 | 3.13 | 0.134 | 32.39 |

| Government intervention | Gov | 3288 | 0.202 | 0.102 | 0.044 | 0.916 |

| Level of Trade Openness | Open | 3288 | 0.187 | 0.299 | 0 | 2.643 |

| Urbanization Rate in Peer Regions | 3288 | 0.563 | 0.082 | 0.269 | 0.835 | |

| Industrial Structure in Peer Regions | 3288 | 42.578 | 6.988 | 26.087 | 80.49 | |

| Economic Development Level in Peer Regions | 3288 | 2.598 | 1.615 | 0.249 | 9.964 | |

| Government Intervention in Peer Regions | 3288 | 0.202 | 0.068 | 0.094 | 0.495 | |

| Trade Openness Level in Peer Regions | 3288 | 0.187 | 0.168 | 0.007 | 0.753 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rural | Rural | Rural | |

| 0.986 *** | 0.656 *** | 0.601 *** | |

| (0.00771) | (0.0351) | (0.0378) | |

| Urban | 0.0211 | ||

| (0.0133) | |||

| Ind | 0.000306 * | ||

| (0.000173) | |||

| GDP | 0.00242 *** | ||

| (0.000579) | |||

| Gov | 0.0105 | ||

| (0.0203) | |||

| Open | −0.00149 | ||

| (0.00524) | |||

| 0.00971 | |||

| (0.0255) | |||

| −0.000409 | |||

| (0.000271) | |||

| 0.000923 | |||

| (0.00130) | |||

| 0.0557 * | |||

| (0.0285) | |||

| −0.00617 | |||

| (0.0125) | |||

| _cons | 0.00514 * | 0.102 *** | 0.0913 *** |

| (0.00289) | (0.0105) | (0.0176) | |

| Year | NO | YES | YES |

| City | NO | YES | YES |

| N | 3288 | 3288 | 3288 |

| R2 | 0.833 | 0.705 | 0.708 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substitution of Explanatory Variables | Winsorization of Data | Exclusion of Provincial Capital Cities | Instrumental Variable (IV) Approach | ||

| The First Stage | The Second Stage | ||||

| 0.424 *** | |||||

| (0.0324) | |||||

| IV | 0.0180 *** | ||||

| (0.000201) | |||||

| 0.602 *** | 0.571 *** | 0.621 *** | |||

| (0.0368) | (0.0393) | (0.0442) | |||

| _cons | 0.135 *** | 0.0849 *** | 0.0879 *** | 3288 | |

| (0.0171) | (0.0171) | (0.0185) | 0.708 | ||

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| Year | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| City | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| LM statistic | 2193.006 | ||||

| Wald F statistic | 7992.103 | ||||

| N | 3288 | 3288 | 3000 | ||

| R2 | 0.701 | 0.707 | 0.711 | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East | Center | West | 2011–2017 | 2018–2022 | |

| −0.0102 | 0.492 *** | 0.675 *** | 0.342 *** | 0.160 * | |

| (0.104) | (0.0746) | (0.0580) | (0.0654) | (0.0892) | |

| _cons | 0.333 *** | 0.0973 *** | 0.0361 | 0.131 *** | 0.270 *** |

| (0.0459) | (0.0344) | (0.0397) | (0.0311) | (0.0538) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| City | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 1164 | 1188 | 936 | 1918 | 1370 |

| R2 | 0.780 | 0.663 | 0.669 | 0.521 | 0.274 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural | Rural | Rural | Rural | |

| 0.548 *** | 0.463 *** | 0.556 *** | 0.451 *** | |

| (0.0338) | (0.0469) | (0.0417) | (0.0468) | |

| GRR | 0.0262 *** | |||

| (0.00248) | ||||

| 0.0135 ** | ||||

| (0.00658) | ||||

| PGDP | −0.00540 *** | |||

| (0.00118) | ||||

| 0.0143 *** | ||||

| (0.00291) | ||||

| GAGDP | −0.0273 * | |||

| (0.0149) | ||||

| 0.0671 * | ||||

| (0.0368) | ||||

| AFW | −0.000532 *** | |||

| (0.000103) | ||||

| 0.00143 *** | ||||

| (0.000268) | ||||

| _cons | 0.0924 *** | 0.146 *** | 0.103 *** | 0.152 *** |

| (0.0163) | (0.0208) | (0.0201) | (0.0209) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| City | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 3014 | 3288 | 3014 | 3288 |

| R2 | 0.783 | 0.711 | 0.668 | 0.711 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural | Rural | Rural | Rural | Rural | Rural | ||

| The different ranges of the absolute values of economic structure differences | Within-Province 0–0.05 | 0.214 *** | |||||

| (0.0258) | |||||||

| Within-Province 0.05–0.1 | 0.175 *** | ||||||

| (0.0221) | |||||||

| Within-Province 0.1–0.15 | 0.138 *** | ||||||

| (0.0240) | |||||||

| Outside-Province 0–0.05 | −0.144 *** | ||||||

| (0.0451) | |||||||

| Outside-Province 0.05–0.1 | −0.0458 | ||||||

| (0.0471) | |||||||

| Outside-Province 0.1–0.15 | −0.0199 | ||||||

| (0.0318) | |||||||

| _cons | 0.205 *** | 0.213 *** | 0.219 *** | 0.284 *** | 0.299 *** | 0.278 *** | |

| (0.0124) | (0.0122) | (0.0131) | (0.0254) | (0.0280) | (0.0220) | ||

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| Year | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| City | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| N | 3137 | 3035 | 2213 | 3248 | 3262 | 3265 | |

| R2 | 0.692 | 0.691 | 0.680 | 0.677 | 0.676 | 0.675 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural | Rural | Rural | Rural | Rural | Rural | ||

| The different ranges of geographical distance differences | Within-Province 0–200 | 0.340 *** | |||||

| (0.0299) | |||||||

| Within-Province 200–400 | 0.375 *** | ||||||

| (0.0306) | |||||||

| Within-Province 400–600 | 0.212 *** | ||||||

| (0.0307) | |||||||

| Outside-Province 0–200 | −0.00490 | ||||||

| (0.0299) | |||||||

| Outside-Province 200–400 | −0.149 *** | ||||||

| (0.0466) | |||||||

| Outside-Province 400–600 | −0.157 ** | ||||||

| (0.0647) | |||||||

| _cons | 0.166 *** | 0.154 *** | 0.210 *** | 0.251 *** | 0.273 *** | 0.313 *** | |

| (0.0149) | (0.0153) | (0.0189) | (0.0186) | (0.0241) | (0.0317) | ||

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| Year | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| City | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| N | 3168 | 3240 | 1632 | 2316 | 3156 | 3240 | |

| R2 | 0.702 | 0.702 | 0.693 | 0.678 | 0.681 | 0.685 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Hu, X. Municipal-Level Analysis of Peer Effects in China’s Sustainable Rural Development: Mechanisms and Imitation Patterns. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11122. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411122

Li X, Hu X. Municipal-Level Analysis of Peer Effects in China’s Sustainable Rural Development: Mechanisms and Imitation Patterns. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11122. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411122

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiao, and Xiaoqiang Hu. 2025. "Municipal-Level Analysis of Peer Effects in China’s Sustainable Rural Development: Mechanisms and Imitation Patterns" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11122. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411122

APA StyleLi, X., & Hu, X. (2025). Municipal-Level Analysis of Peer Effects in China’s Sustainable Rural Development: Mechanisms and Imitation Patterns. Sustainability, 17(24), 11122. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411122