1. Introduction

Tannery industrial wastes (solid wastes generated during the leather-processing steps, such as trimming, fleshing, shaving, splitting, buffing, and cutting) are renewable resources of valuable substances; there is also a great potential to convert them into environmentally friendly bioenergy [

1]. Utilization of tannery waste could be an important step towards sustainable development, due to valuable substances contained in it [

2]. The main components of raw leather or its wastes, including fleshings, trimmings, splits, and scorings, are protein, fat, and water, presented at 2.5–10.5% (

w/

w), 10.5% (

w/

w), and up to 80% (

w/

w), respectively. The tanned leather comprises about 15% mineral components, and 3.5–4.5% (

w/

w) Cr

2O

3. The chemical composition depends on the kind and quality of the raw material [

1,

3].

Leather processing involves three main stages: beamhouse, tanning, and finishing. During the beamhouse stage, processes aim to remove hair, non-collagenous proteins, and grease from rawhide and skin, while opening up collagen fibers to prepare for tanning. The tanning process involves the reaction of tannins with the collagen matrix to stabilize it [

4,

5]. Chromium-based compounds are the most commonly used tanning agents, constituting around 90% of the tanning process. Other tanning agents, such as other metals, synthetic tannins, and aldehydes, are also utilized in smaller proportions [

1,

6,

7,

8]. Chromium tanning relies on the formation of a trimeric chromium aqua complex before cross-linking with the carboxyl group of the collagen, affecting its intermolecular structure. This process yields light leathers with high resistance to thermal, bacterial, and thermochemical stress [

1,

9,

10,

11]. The final stage of leather processing is the finishing step, which depends on its further use and application [

4,

5,

12]. The wet leather after chrome tanning stabilization is called wet-blue. The wet state of the leather is held prior to the wet-end, drying, and finishing steps, thus wet-blue trimmings and wet-blue shavings (chrome shavings) represent typical chrome-tanned leather wastes [

13].

The leather industry aims to reduce waste and maximize reuse due to rising landfill costs and regulations [

14]. While replacing chromium increases production costs, chrome tanning remains the most reliable and cost-effective method. Plant-based agents offer a bio-based alternative, but may not be more environmentally friendly [

15]. Tannins, plant-derived phenolic compounds used in tanning, can pose environmental risks, as vegetable tanning wastewater often contains toxic or non-biodegradable organic compounds [

16,

17,

18,

19].

Wet-white procedures, which involve tanning without chromium using aluminum, zinc, titanium salts, or synthetic dyes, typically result in leather with good physical properties but weaker resistance to UV radiation or heat compared to chromium-tanned leather [

20,

21,

22]. Aluminum in these processes is loosely bound to collagen, making the reaction reversible when the leather is wetted or exposed to acidic environments [

23]. Synthetic tannins or syntans, organic compounds with high molecular weight (e.g., melamine-based, acrylic), are commonly made from aromatic substances such as cresols, phenols, and naphthalene, using formaldehyde and sulfuric acid. Components of syntans like phenol, formaldehyde, and tannins pose environmental challenges as they are difficult to biologically degrade [

24].

Current directions for the use of this protein-rich waste include protein hydrolysate in various fields, like animal feed, to obtain collagen or gelatin, and the extraction of fats for biodiesel production [

25,

26,

27]. Other potential directions are the production of activated carbon, biopolymers, surfactants, or organic fertilizers, as well as biodegradable re-tanning agents [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33].

Due to their structure, leather wastes are considered to be too stable for anaerobic degradation [

34], but the tannery residues’ characteristics suggest that anaerobic digestion is a potential alternative treatment [

35].

The main challenges to producing biogas from chromium-tanned leather are the efficiency of production compared to other types of waste, because chromium (III) removes a part of the organic load from the leather, and this organic part improves anaerobic digestion [

36]. The challenge is also the conversion/oxidation of Cr (III) to Cr (VI). Chromium (VI) is toxic and cancerogenic; it can cross the cellular membranes and react with intracellular molecules [

13]. The inhibitory concentrations of Cr that cause a 50% reduction in the cumulative methane production range from 27 to 3000 mg/L. Literature reports large differences, but the concentration depends on many factors, among others, carbon source and sludge characteristics [

37]. Zupancic and Jemec [

37] concluded that tannery wastes are appropriate substrates for biogas production at 286 mg/L of chromium (III). Gomes et al. also observed that the presence of chromium from 233 to 369 g/L had no effect on the fermentation process [

34]. Metals used in wet-white procedures have toxic effects on bacteria, too. Moreover, no information on this has been found in the literature in the context of the fermentation of leather waste tanned using this procedure. However, it has been reported that zinc inhibits anaerobic digestion—particularly inhibits growth of acetogenic and methanogenic bacteria—within a concentration range from 200 to 600 mg/L. While aluminum is generally considered less toxic than transition metals like Cu or Ni, it can still interfere with microbial enzymatic activity, particularly at elevated concentrations or in certain chemical forms [

38].

Scientists have explored various methods for handling leather waste, particularly focusing on its potential for biogas production through anaerobic digestion. This research has been driven by the dual goals of mitigating environmental pollution and extracting energy from waste materials. Early studies highlighted the challenges posed by chromium-tanned leather, which complicates biodegradation due to the binding of reactive sites and limited solubility. Vegetable-tanned leather and other types of tanning agents were also investigated to assess their biodegradability and potential for biogas generation. The central objective of these studies was to understand how the composition and treatment of leather waste affect its anaerobic digestion.

The effects of various substrates, pretreatments, and operating conditions were studied and discussed. For example, Priebe et al. [

13] tested chrome-tanned leather using sewage sludge as inoculum but found lower biogas yields compared to controls, due to chromium saturation. Agustini et al. [

39] achieved approximately 200 mL of biogas after 75 days by digesting wet-blue shavings with fermented sludge and a nutrient solution, observing a 20% reduction in mass. Other studies, such as those by Dhayalan et al. [

19], emphasized the importance of removing tanning agents before digestion to enhance gas production. Pretreatment methods like thermal autoclaving and hydrothermal processes were also assessed. Agustini et al. [

40] observed that thermal pretreatment improved biodegradability for vegetable-tanned leather but was less effective for chrome-tanned leather. Gomes et al. [

41] showed that pretreated samples led to quicker and more effective biogas production, achieving 416–460 L/kg in some cases.

The results of these studies provided valuable insights into the biogas potential of leather waste. Chrome-tanned materials, though challenging to degrade, yielded significant biogas when pretreated, with methane content sometimes exceeding 59%. Vegetable-tanned leather, while initially yielding lower gas volumes, benefited from detanning and pretreatment processes. In one notable case, Agustini et al. [

35] achieved maximum methane yields of 15.01 mL/gVSS and total biogas production of 27.9 mL/gVSS. Larger reactors demonstrated higher capacities, with up to 29.91 mL/gVSS biogas production and 59.1% methane content. Gomes et al. [

41] reported much higher biogas production for pretreated substrates compared to untreated ones, though methane content was not determined. Overall, the research underscores the need for tailored pretreatment strategies to maximize energy recovery from leather waste while addressing environmental concerns.

The experiments on leather waste digestion were conducted using reactors of various sizes, ranging from small laboratory-scale setups to larger bioreactors, to assess the impact of reactor volume on biogas production. Priebe et al. and Agustini et al. performed their studies in 300–350 mL batch reactors [

13,

35,

39,

42], while Gomes et al. [

41] used even smaller 65 mL reactors, which limited the organic dry matter available for fermentation. In contrast, larger-scale experiments, such as those by Agustini et al. [

42], involved 2.5 L reactors, which demonstrated higher biogas yields compared to smaller systems. Temperature control was another critical factor, with most studies maintaining mesophilic conditions at around 35 °C. This temperature range was chosen to optimize microbial activity and biodegradation efficiency. Some studies also explored thermal pretreatment methods, such as autoclaving at 121 °C for 5 min, to improve substrate breakdown before digestion. The findings indicate that reactor size and temperature significantly influence the efficiency of biogas production, with larger reactors often yielding better results due to improved microbial stability and process scalability [

40]. In addition, recent reviews highlight the relevance of advanced anaerobic biofilm-reactor configurations (such as moving-bed, upflow, and hybrid systems) and provide updated insights into operational challenges, kinetic behavior, and yield optimization across various substrates, further supporting the technological basis of this study [

43].

Analyzing the available literature, only two papers were found about the possibility of anaerobic digestion of synthetic tanned (wet-white leather) [

44,

45]. The researchers subjected chromium and chromium-free leather wastes to enzymatic hydrolysis since the non-hydrolyzed substrate did not undergo digestion. After proteolysis (enzymatic hydrolysis), they obtained 438 L/kg VS of biogas with a methane content of 76%.

In addition, the fermentation test procedure is rather an internal methodology for a given laboratory. To our knowledge, only two groups of researchers [

41,

44,

45] conducted fermentation test according to the VDI protocol or DIN 38414 [

46,

47].

This study aimed to investigate and compare the capability of anaerobic digestion of leather wastes regardless of the type of tanning agent used (chrome, vegetable, and synthetic). The aim was also to determine and compare methane fermentation (at 40 °C) by determining the dynamics of the process and final efficiency of biogas and methane in 2000 mL reactors, before and after chemical pretreatment, and without thermal pretreatment. For chemical pretreatment, the authors used organic compounds, which were used for the solubilization of leather wastes, but without research on biogas impact [

48]. Organic salts were also used with success for chrome leaching; the authors studied thermodynamics, kinetics, and mechanism [

49].

The aim was also to evaluate the influence of the type of tanning agent and pretreatment on the course of the fermentation process. The analysis of the biogas efficiency of the substrate was based on the modified German norm DIN 38414 and the standardized biogas guideline issued by the Association of German Engineers in Dresden, VDI 4630. The methodological approach applied in this study is consistent with the principles outlined in ISO 11734:2023, which describes the evaluation of the ultimate anaerobic biodegradability of organic compounds by measuring biogas production [

50]. The efficiency of biogas production is defined as the maximum amount of biogas and biomethane production during fermentation of the analyzed substrate under optimal, laboratory conditions.

In this study, an integrated test strategy was adopted, conceptually aligned with the framework proposed by Strotmann et al. [

51], in which anaerobic toxicity tests, static batch biodegradation assays, and continuous-reactor evaluations form a staged assessment of anaerobic treatability. As a preliminary investigation, the present work corresponds to the first component of such a strategy, where batch anaerobic digestion tests serve as the primary screening tool.

Batch tests are widely used as the initial methodological step because of their simplicity, reproducibility, and ability to provide essential baseline information on substrate biodegradability, digestion dynamics, and biogas potential. Conducting all experiments in a uniform batch system enabled direct comparison of different pretreatments, assessment of decomposition time under standardized conditions, and evaluation of the influence of tanning chemistry on digestion performance.

This approach made it possible to identify the most promising pretreatment pathways before proceeding to more advanced stages of process development, such as kinetic modeling, continuous reactor studies, or pilot-scale evaluation. While DIN 38414 S8 provides the procedural framework for static anaerobic assays, it does not prescribe a broader integrated testing strategy; therefore, the methodological structure applied in this work reflects a deliberate design consistent with established concepts for sequential anaerobic biodegradability assessment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Leather Wastes

The leather shavings were obtained from a factory that produces premium leather for the automotive industry. The samples of collected leather shavings were wet-blue (WB) chrome-tanned and wet-white (WW) synthetic-tanned shavings, and also wet-green (WG) olive-tanned shavings. Mesophilic anaerobic sludge was obtained from a local wastewater biogas plant. The leather samples before fermentation were kept at ambient temperature. The total solids were 60.56%, 58.95%, and 44.32%, whereas volatile solids were 86.58%, 84.72%. and 92.35%, respectively, for WB, WW, and WG. Nitrogen content in the analyzed samples was similar and amounted to 8.02%, 8.76%, and 8.53% for WB, WW, and WG, respectively. Total chromium content was 14.1 g/kg and 0.02 g/kg for WB and WW, respectively. Analyses were consistent with the literature [

13,

44,

45].

2.2. Inoculum

The inoculum was fermented sludge with characteristics: pH 7.8, total solids (TS) 3.1%, volatile solids (VS) 69.1%, total ammonia nitrogen 1.18 gN/kg fresh mass (FM), and 2.21 gN/kg TS. Inoculum was obtained from a mesophilic digester at a municipal wastewater treatment plant and was stored for two weeks before the fermentation process to finish its biogas production.

2.3. Pretreatment

The leather shavings were subjected to water and chemical pretreatments. The various pretreatment strategies consisted of water, organic acids, salts, and chemical oxidation (Fenton oxidation), as summarized in

Table 1. For each pretreatment, 30 g of leather shavings were immersed in 200 g of the corresponding solution, prepared using deionized water. Pretreatments were conducted at room temperature for 2 h under soaking and mixing conditions.

No pH adjustment was performed during pretreatment; the pH reflected the natural acidity or alkalinity of the prepared solutions (acids, salts, or oxidizing agents). For the Fenton pretreatment, the FeSO4 and H2O2 solution (500 mg/L FeSO4 and 300 mg/L H2O2) was prepared once and applied as a single mixture.

After pretreatment, the liquid phase was separated from the leather shavings using a Büchner funnel and collected for further physicochemical analyses. The shavings retained on the funnel were rinsed with deionized water until the filtrate reached neutral pH, after which the solids were used for the fermentation tests.

WG shavings were treated with a sulfate solution according to the procedure followed by Dutta [

52], whereas Fenton oxidation pretreatment was performed according to Thankappan [

24]. The Fenton process is a well-known advanced oxidation process, and has proved to be an efficient method for tannery wastewater due to its oxidizing properties against phenolic compounds [

16,

53]. Organic acids pretreatment was conducted according to Fernandez [

48] but without thermal pretreatment.

Pretreatment strategies were selected individually for each type of leather shaving due to differences in tanning chemistry. Chrome-tanned shavings (WB) contain Cr (III) cross-linking complexes; therefore, chelating agents (EDTA), organic acids (OA), and Fenton oxidation were applied to promote chromium leaching and disruption of the collagen matrix. Synthetic-tanned shavings (WW), which do not contain chromium, were treated only with acid-based and oxidative agents expected to interact with synthetic tannins. Olive-tanned shavings (WG) contain high levels of vegetable polyphenols; therefore, pretreatments targeting phenolic structures (borax, sodium sulfate, EDTA + OA) were included along with water and oxidative treatments. This targeted selection ensured that each pretreatment matched the chemical composition and expected inhibitory effects of the corresponding tanning system.

2.4. Methane Fermentation Test

Each reactor contains inoculum and the appropriate amount of substrate required to achieve an initial inoculum-to-substrate ratio of 2 (VS basis), in accordance with DIN 38314 S8 and VDI 4630. To prevent inhibition in the fermentation batch, the substrate should be in proper proportion to the seeding sludge; to maintain a balanced I/S ratio, it is essential to avoid acidification or overload of the system. To standardize the course of fermentation, the fermentation batch should contain 1.5% to 2% by weight of organic mass from the seeding sludge (no more and no less), ensuring a comparable biomass concentration across tests. Appropriate amounts of substrate and inoculum were calculated based on the determination of total solids (TS) and volatile solids (VS). Blank tests (containing only inoculum) were also included to correct for the background methane and biogas potential of the inoculum [

46,

47,

54]. Batch tests are commonly used at the laboratory scale to assess the anaerobic biodegradability of organic matter, determine maximum methane potential, and evaluate inhibition, including inoculum activity. This knowledge is crucial for the design, operation, and economic viability of biogas plants [

55,

56,

57,

58].

The methane fermentation process of leather wastes was carried out in glass reactors with a working volume of 1200 mL. Calculated amounts of tested substrates and inoculum were placed in the reactors. To maintain the appropriate conditions, the reactors were kept in a water bath with temperature control under mesophilic conditions (40 °C). Before fermentation, the reactors were flushed with nitrogen for two minutes to maintain strictly anaerobic conditions at the beginning of the process. The gas produced by each fermenter was collected in a cylindrical vessel filled with water and a barrier liquid to prevent biogas solubility in water. The system works on the principle of connected vessels. The experimental setup has been described and presented earlier [

59].

The study consisted of the digestion of three types of shavings before and after pretreatment under different conditions. Leather shavings without pretreatment were also fermented, as a control sample. As a reference, the inoculum itself was also fermented, which was taken into account in the calculations. All the experiments were carried out in triplicate.

2.5. Biogas Measurements

Biogas measurements were carried out every day at the same time with an accuracy of 10 mL. The qualitative and quantitative composition of fermentation gases was determined by a portable biogas analyzer (GA5000, Geotech, QED Environmental Systems Ltd., Coventry, UK) when the volume of biogas in the cylinder was at least 0.45 dm3. The analyzer had ATEX II 2G Ex ib IIA T1 Gb (Ta = −10 °C to +50 °C), IECEx and CSA quality certifications, and a UKAS ISO 17025 calibration certificate. The equipment allows the measurement of CH4, CO2, O2, H2, and H2S in the ranges 0–100%, 0–100%, 0–25%, 0–1000 ppm, and 0–5000 ppm, respectively. Calibration of the device was performed once per week.

When the volume of biogas was insufficie nt to use the analyzer (below 0.45 dm3), especially at the end of the process, a gas chromatograph (GC) was used for qualitative and quantitative determination, equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD). Argon with a flow rate of 0.6 mL/h was used as a carrier gas. A ShinCarbon ST (Restek Corporation, Bellefonte, PA, USA) with characteristics of 2 m/2 mm ID (inner diameter), 1/8″ OD (outer diameter), Silico was used.

According to DIN 38 414 8S, batch experiments were continued until daily biogas production was less than 1% of total biogas production. Volume of measured biogas was normalized to standard conditions (0 °C and 1.013 bar). This threshold was used as the operational definition of ‘decomposition time’ for all substrates and pretreatments.

The procedures for gas characterization and normalization followed standard analytical approaches for anaerobic digestion, consistent with recent methodological recommendations [

60].

2.6. Waste and Inoculum Analysis

The gravimetric method was used to determine total solids (TS) and volatile suspended solids (VSS) according to standard methods [

61]. VSS was also determined for the shavings after pretreatment; however, as this parameter is expressed as a percentage of total solids rather than an absolute mass, it reflects only the relative proportion of volatile to non-volatile matter. Therefore, VS values cannot be used to draw conclusions about solubilization or chemical modifications of the substrate.

The total Kjeldahl Nitrogen (TKN) was measured using the Kjeldahl method (KjelMaster K-355, Speed Digester K-436, Büchi Labotechnik AG, Flawil, Switzerland). For TKN samples digested in concentrated sulphuric acid in the presence of copper-based catalyst with titanium, the next step was a steam distillation into 3% boric acid solution with Tashiro indicator, then titrated with 0.1 N hydrochloric acid to measure the released ammonia.

2.7. Total Phenols Determination

Total phenols in liquid samples after WG pretreatments were estimated as gallic acid equivalents (GAE), according to the Folin–Ciocalteu assay [

62]. Quantitative determination of polyphenols is hampered by their structural complexity and diversity. The Folin–Ciocalteu method of assay is the simplest method available for the measurement of phenolic content in products [

63,

64].

The total volume of the reaction mixture was 10 mL. Six milliliters of water and 0.1 mL of sample were mixed in a 10 mL volumetric flask, then 0.5 mL of undiluted Folin–Ciocalteu reagent was subsequently added. After 2 min, 1.5 mL of 20% (w/v) Na2CO3 solution was added, and then the volume was made up to 10 mL with distilled water. After 30 min of incubation at 40 °C, the absorbance was measured at 760 nm and compared to the gallic acid calibration curve (0–500 mg/L) elaborated in the same manner. Data were presented as the average of duplicate analyses.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All anaerobic digestion experiments were performed in triplicate. Statistical analysis was conducted using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to evaluate differences in cumulative biogas and methane yields among pretreatment methods for each substrate type (WB, WW, and WG). ANOVA was performed separately for each substrate, since pretreatment sets differed between tanning types. Normality and homogeneity of variance were verified prior to analysis. A significance level of p < 0.05 was adopted. Statistical calculations were performed using SciPy (Python 3.10, The Python Software Foundation (PSF), Wilmington, DE, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

Batch tests are fundamental experiments because, despite their simplicity, they provide essential information about the biodegradability and biogas potential of a given substrate. The results obtained from such tests are extremely useful for planning further research, including the selection of appropriate process conditions and pretreatment methods. Moreover, they help determine whether there is a justified basis for proceeding to more advanced, continuous, or pilot-scale studies.

Data in

Table 2 presents the cumulative methane, biogas production, and cumulative biogas from different types of tanned shavings (chrome, synthetic, and olive tanned) and after various chemical pretreatment methods. The results are discussed in the following subsections.

3.1. Wet-Blue Shavings

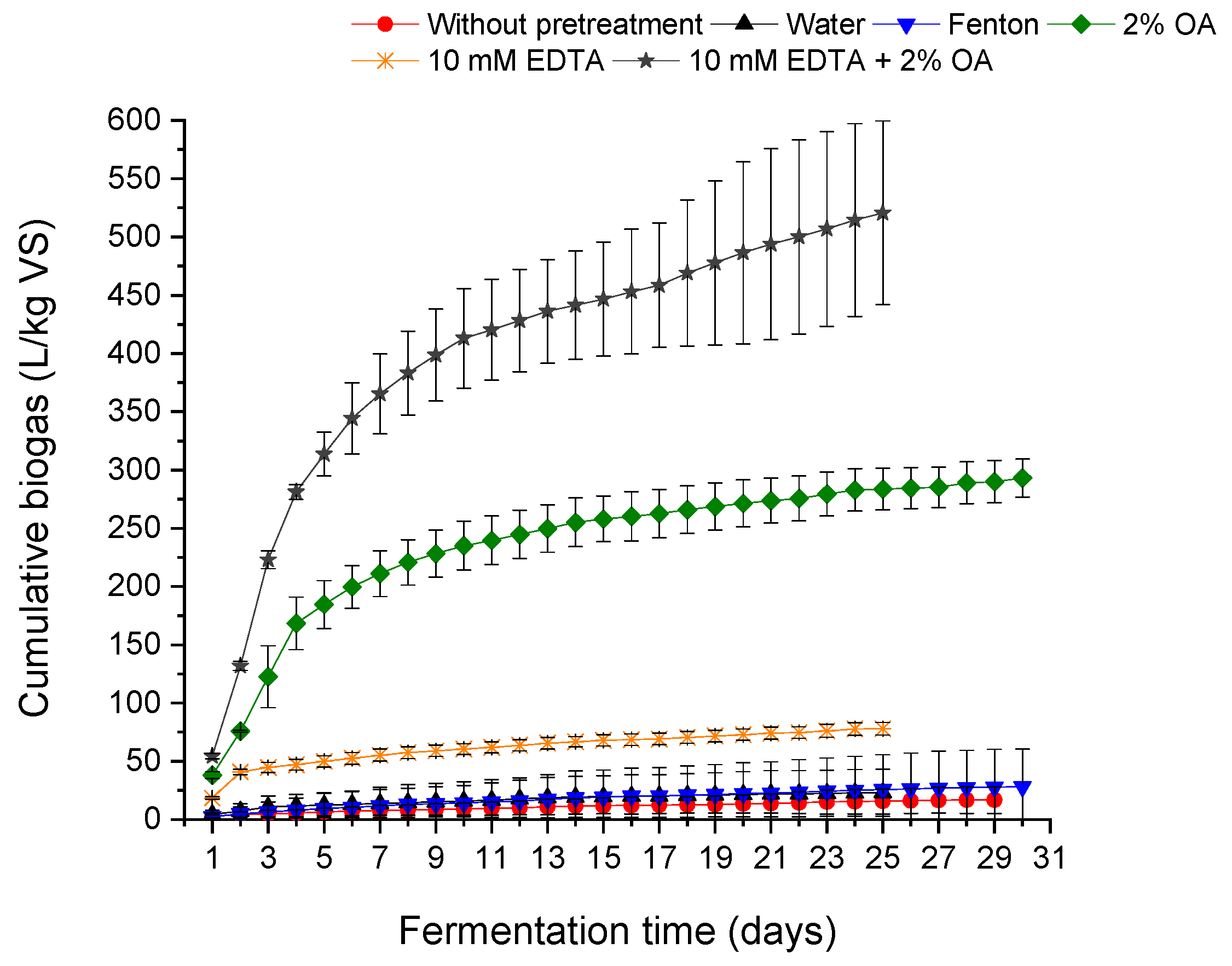

Figure 1 presents the cumulative biogas production of wet-blue shavings before and after chemical pretreatment.

The fermentation time for the substrate without treatment (raw chrome shavings) was 29 days. In the case of using an EDTA solution and a mixture of EDTA with OA, the fermentation time was shortened and amounted to 25 days; for the remaining ones, the fermentation time was 29–30 days. The dynamic of the fermentation process can be observed by comparing the rates of increase in biogas yield over time. Fermentation after pretreatment tends to show a more rapid increase in biogas production compared to the untreated substrate. For example, the 10 mM EDTA + 2% OA treatment shows a steep increase in biogas yield, indicating an efficient fermentation process.

At some point, the fermentation process reaches a plateau phase where the rate of increase in biogas yield decreases, indicating the exhaustion of available substrate or other limiting factors. It can be observed especially in the case of fermentation of raw material (WB shavings without pretreatment) and after pretreatment with EDTA, Fenton, a mixture of acids and water (the graph for water pretreatment overlaps with raw shavings fermentation).

As a result of anaerobic digestion of WB shavings, 16.78 L/kg VS of biogas and 12.31 L/kg VS of methane were obtained, but the biogas contained a high concentration of methane over 73%. Priebe et al. conducted research with blue shavings as a substrate, with nutrient solution, but biogas generation was inferior to the control sample. The reason was the saturation of reactive sites through chromium binding, as well as lower water solubility. They also concluded that anaerobic sludge was inadequate for leather digestion, unlike aerobic sludge [

13]. Fernandez et al. [

48] focused on the solubilization during fermentation; however, in the case of chrome-containing shavings, no significant changes were found, and no valuable biogas production occurred due to the recalcitrant nature of this type of waste. Agustini et al. in their studies obtained similar production of biogas (15.01 mL/g VSS); however, they used chromium sludge (from a wastewater treatment plant). Furthermore, the digestion time was much longer (80 days), and the methane concentration was lower (about 57%). Before the fermentation process, autoclaving as a thermal process was applied [

35]. In another study by the same author [

42], shavings and sludge from a beamhouse were fermented in batch reactors for 150 days at 35 °C. The maximum CH

4 yield in biogas was 9.42 mL/gVSS added, and the maximum biogas production was found to be 20.94 mL/gVSS in the case of fermentation in 300 mL bioreactors, while the content of methane in biogas was 59.3%. Similarly, in 2.5 L bioreactors, the maximum CH

4 yield in biogas was 11.5 mL/gVSS added, and the maximum biogas production was found to be 29.91 mL/gVSS with 59.1% of methane in biogas.

In general, each of the proposed treatments results in an increase in biogas yield over time, from about 37% up to 3000%, compared to the control sample. The highest biogas production was observed for the EDTA and OA mixture, followed by the OA solution, respectively, 520.60 L/kg VS and 293.08 L/kg VS, with methane content approx. 67% and 62%, respectively. However, the use of the 10 mM EDTA solution alone in the pre-treatment allowed for obtaining only 77.86 L/kg of biogas with an average methane content of approximately 59%. A mixture of 500 mg/L FeSO

4 with 300 mg/L H

2O

2 and water was the least effective; the amount of biogas obtained for this pretreatment was 27.95 L/kg VS (Fenton) and 23.02 L/kg VS (water), compared to the control sample (WB shavings without pretreatment; 16.78 L/kg VS). This corresponds to increases of approximately 66% (Fenton) and 37% (water), respectively. Interestingly, these two processing methods significantly reduced the methane content in biogas to an average of 45%. Dhayalan et al. also observed an increased level of gas after the detanning process compared to tanned shavings, but the composition of the produced gas was not determined. The researchers also observed that the concentration of analyzed fatty acids was higher in treated blue shavings than in raw substrate, which clearly indicates that pretreated leather is more biodegradable than tanned leather [

19].

The addition of FeSO

4 and H

2O

2 likely led to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including hydroxyl radicals (•OH), superoxide anions (O

2•–), and hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2), via Fenton-type reactions. These ROS are highly reactive and can induce oxidative stress by damaging biological macromolecules such as membrane lipids, proteins, and DNA. ROS undergo lipid peroxidation reactions with cellular membranes, compromising the integrity of microbial cells. Moreover, ROS have been shown to disrupt protein structure and function, which impairs key enzymatic processes. In anaerobic fermentation systems, ROS are particularly toxic to enzymes involved in central metabolic pathways. They can inhibit enzymes responsible for methanogenesis and other critical steps in organic matter degradation. This toxic effect on enzymes explains the observed suppression of methane production [

65,

66,

67]. The oxidative stress caused by ROS generation was identified as a key factor negatively affecting the hydrogen-producing microbial community. Similarly, ROS can inhibit enzymes involved in key metabolic pathways, such as glycolysis and the hydrogenase enzyme system, thereby disrupting microbial activity required for both hydrogen and methane production [

65,

68]. Therefore, the observed decrease in methane concentration in the FeSO

4 and H

2O

2 treatments can be attributed to the cytotoxicity induced by ROS and their inhibitory effects on the methanogenic microbial community and its enzymatic systems.

Gomes et al. [

41] investigated the biogas production from chromium-tanned shavings before and after pretreatment (extrusion and hydrothermal). The authors conducted digestion according to VDI 4630, but during experiments, only 65 mL reactors were used, which resulted in only 0.15 g organic dry matter being subjected to methane fermentation. They observed that biogas production for pretreated samples starts earlier, and the COD reduction is more effective. The biogas formation for all pre-treated samples was very similar (416–460 L/kg); the methane content was not determined, and the time required for degradation was shortened compared to untreated substrates. The obtained results were much better than those published before.

3.2. Wet-White Shavings

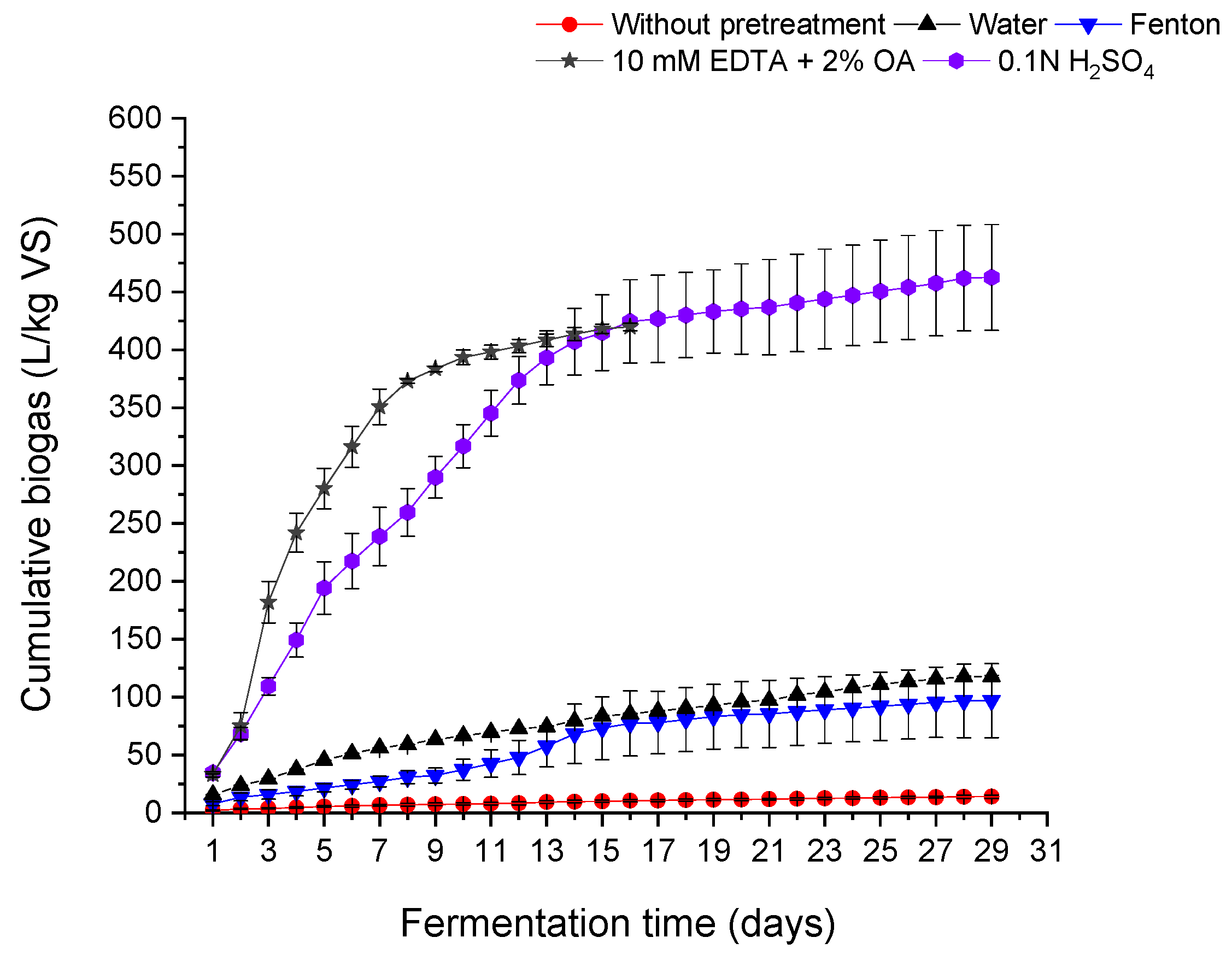

Figure 2 presents the cumulative biogas production of wet-white shavings without pretreatment and for four different chemical conditions (water, Fenton, mixture of oxalic acid and EDTA, and inorganic acid solution).

Regardless of the applied pretreatment, the anaerobic decomposition time was the same and amounted to 29 days in almost every case, i.e., compared to other organic substrates, it is quite long. The situation was different in the case of treatment with a mixture of organic acids, as the fermentation process was significantly shortened and lasted only 16 days. The use of a mixture of oxalic acid and EDTA shortened the fermentation by approximately 44%. The process duration corresponds solely to the time required to reach the <1% daily biogas production threshold defined by DIN, which may occur at similar times despite differences in intermediate fermentation dynamics. Treatments with organic and inorganic acids tend to show a more rapid increase in biogas production compared to wet-white shavings without pretreatment. The biogas generation for shavings after organic acids treatment indicates efficient biogas production. The biogas yield in the case of treatment with sulfuric acid solution was similar, but H2SO4 use did not affect the length of the process, and a flattening of the curve was observed, which may suggest the occurrence of factors inhibiting the fermentation process. A similar flattening of the curve (in the initial stage of the process) was also observed in the case of wet-white shavings fermentation after Fenton pretreatment, which may also suggest the appearance of factors inhibiting the process. The relatively high intensity of biogas production for the substrate treated with acids, compared to other substrates, indicates high microbiological activity or availability of the substrate, despite inhibitory factors when inorganic acid is used. The rate of biogas generation tends to slow down as fermentation progresses, indicating a depletion of easily fermentable substrates or the accumulation of inhibitory compounds.

As a result of fermentation of raw wet-white shavings (without pretreatment), biogas with a high methane content of over 76% was obtained; however, its amount was small and amounted only to 14.03 L/kg VS with 10.78 L/kg VS of methane, which is approximately 3 L less biogas per kg VS, compared to raw WB shavings. Wrzesińska-Jędrusiak et al. [

44] obtained 18 L of biogas per kg of VSS from white shavings, but after the enzymatic hydrolysis, they obtained 438 L of biogas per kg of VSS.

The largest amount of biogas obtained from WW shavings was observed after treatment with sulfuric acid solution. In this case, biogas yield increased from 14.03 L/kg VS (control) to 462.72 L/kg VS, corresponding to approximately a 3200% increase, with a methane concentration of 71.06% (328.74 L/kg VS methane). The second most effective pretreatment was the mixture of organic acids (10 mM EDTA + 2% OA), which resulted in 419.90 L/kg VS of biogas and 270.93 L/kg VS of methane, with a methane content of approximately 65%. The use of a mixture of 500 mg/L FeSO4 and 300 mg/L H2O2 (Fenton) resulted in 96.88 L/kg VS of biogas and 66.72 L/kg VS of methane, which is about seven times more biogas compared to the untreated sample. The methane content in the biogas was also relatively high (approx. 69%).

However, when comparing chemical treatments, the Fenton process was the least effective among acid-based and chelating strategies. In contrast, water-treated shavings produced 117.81 L/kg VS of biogas and 76.62 L/kg VS of methane, which not only exceeds the yield obtained after Fenton pretreatment but also presents an environmentally friendly option due to the absence of added chemicals. The methane content in biogas was at a comparable level (65%).

The results show that simple water pretreatment is a promising method for improving the biodegradability of wet-white shavings.

3.3. Wet-Green Shavings

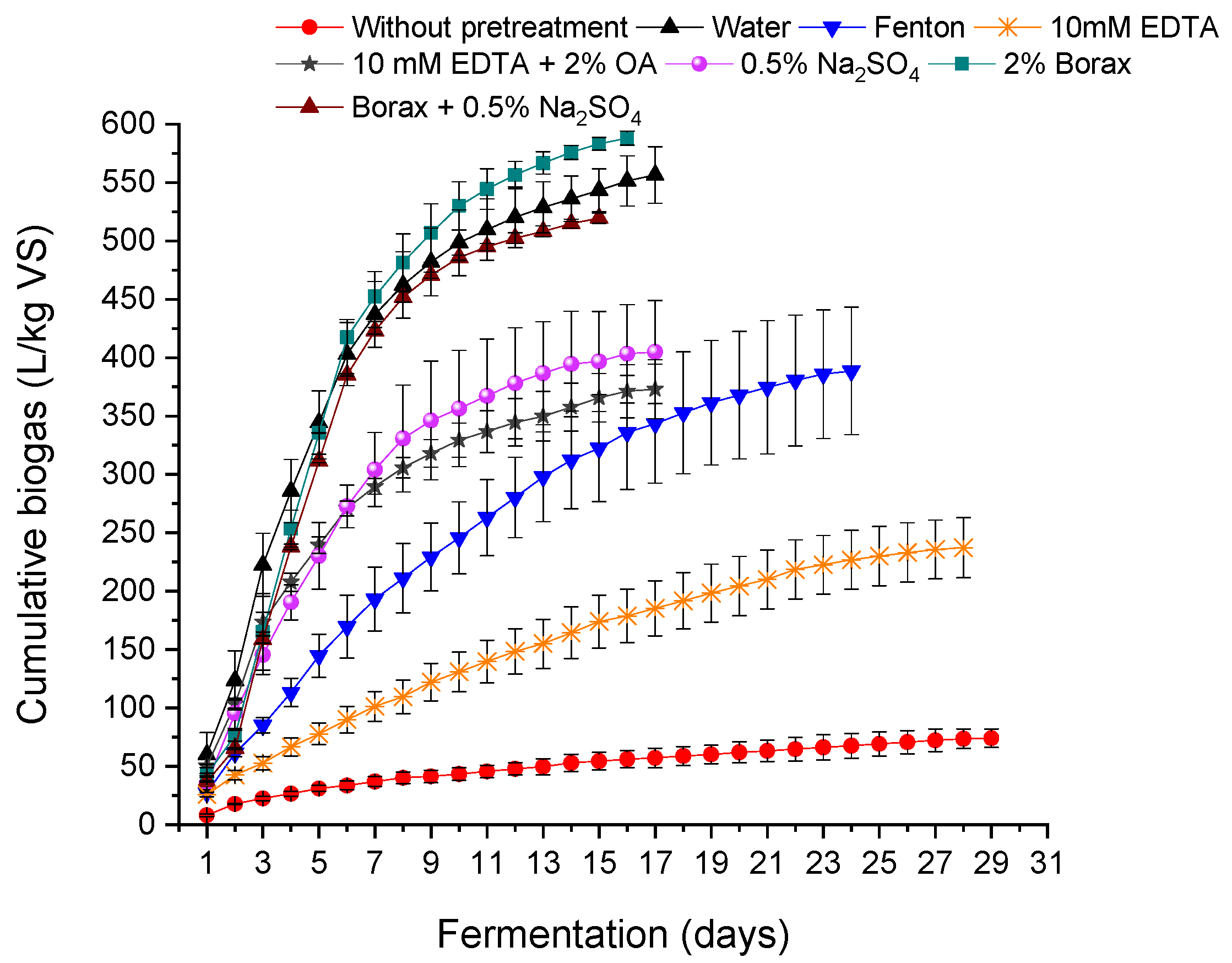

Figure 3 presents the cumulative biogas production of wet-green shavings without pretreatment, for water treatment, and six different chemical conditions. WG shavings were treated with water, Fenton, a mixture of organic acids, as in the case of WB and WW, but also with solutions of sodium salts, borate, sulfate, and their mixtures.

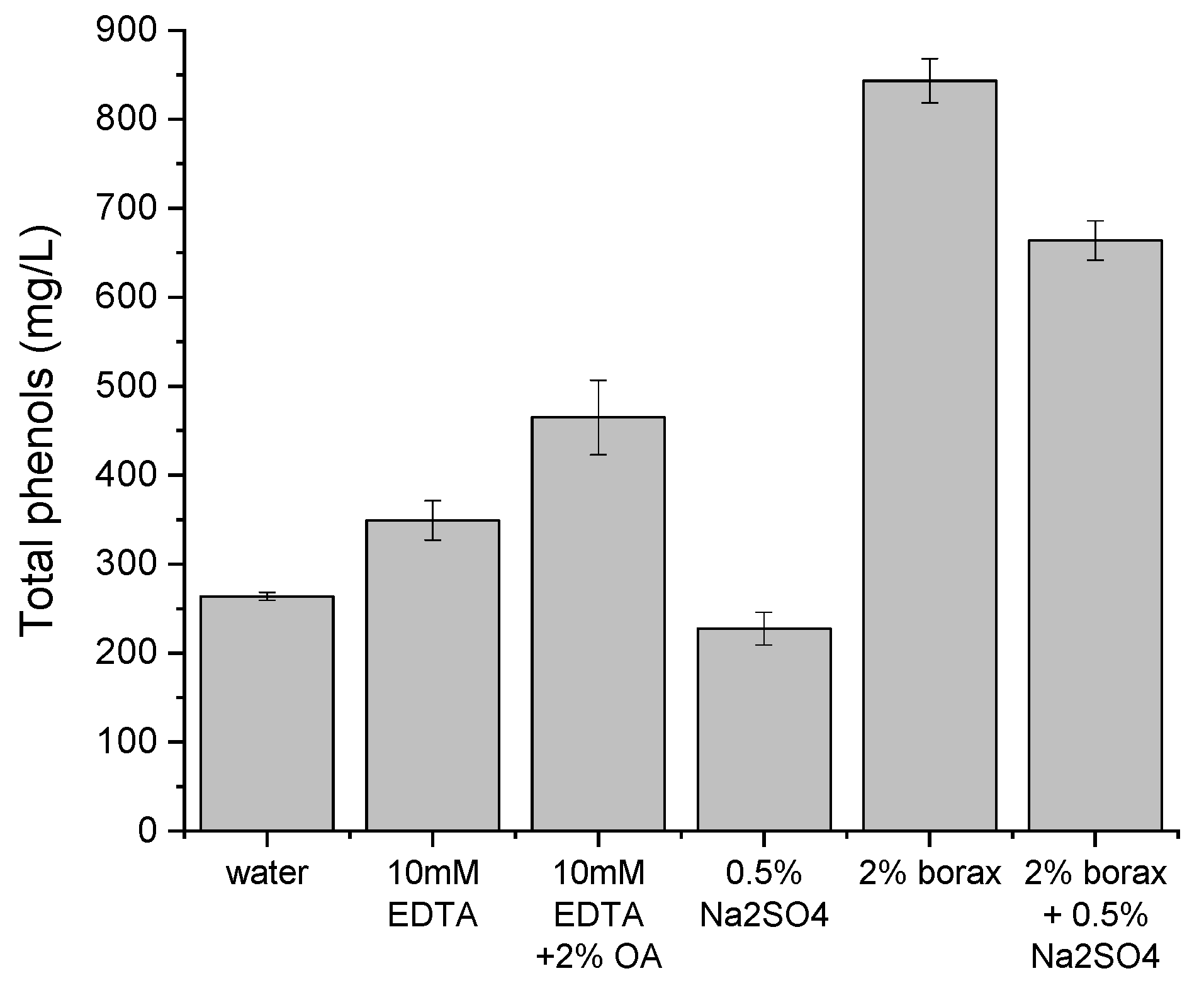

Figure 4 presents the concentration of total phenols in liquid samples after pretreatment.

Fermentation of WG shavings without pretreatment lasted as long as in the case of WB and WW, 29 days. The use of water as a pre-treatment shortened the fermentation time to 17 days. The fermentation time was also significantly shorter, up to 15 or 16 days, after treatment with organic acids, sodium salts, and their mixture. The fermentation time was also shorter as a result of the Fenton treatment, while the use of the EDTA solution practically did not affect the duration of the process.

As a result of WG anaerobic digestion, 74.01 L/kg VS of biogas and 40.82 L/kg VS of methane were obtained, with a methane content of 55.15%. Comparing the amounts of biogas obtained from untreated shavings, it was found that the raw WG substrate generated the largest amount of biogas—341% more than WB (16.78 L/kg VS) and 428% more than WW (14.03 L/kg VS). At the same time, it was observed that the methane content for WG was the lowest. This could indicate either incomplete conversion of organic matter to methane or the formation of higher amounts of non-methane gases such as CO2, H2, or trace volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Such outcomes may result from the specific composition of WG, which likely contains higher levels of non-proteinaceous organics or additives from prior processing that influence gas composition. It is also possible that some toxic byproduct might inhibit methanogenesis—this should be studied during future investigations.

Agustini et al. [

40] concluded that the low concentration of chromium in sludge is more suitable for digestion, while vegetable tanning sludge showed the opposite trend due to toxicity. Dhaylan et al. [

19], comparing chrome-tanned and vegetable-tanned materials using TKN and TOC analyses, concluded that vegetable-tanned leather may exhibit slightly higher biogas production due to the degradation of soluble organic compounds. However, the conducted shrinkage temperature studies were interpreted in such a way that the non-bioreactiveness of tanned materials results from the presence of tanning agents. They observed that vegetable-tanned material has slightly higher biogas production, compared to chrome material. They explained the slightly higher amount of obtained biogas by the possibility of degradation of soluble organic compounds contained in vegetable-tanned material. However, in the conducted fermentation studies, mixed cultures were used, which can more easily degrade such compounds.

The increase in biodegradability, which translates into an increase in the amount of biogas obtained, was observed by Dhayalan et al. [

19] who, during the anaerobic digestion of pretreated vegetable-tanned leather, observed an increase in the amount of fatty acids compared to the raw substrate.

The use of water as a pretreatment shortened the fermentation time to 17 days and resulted in 556.48 L/kg VS of biogas and 375.66 L/kg VS of methane, with a methane content of 67.51%. This represents a 652% increase in biogas compared to the untreated WG substrate.

In the case of WG, the treatment with EDTA solution turned out to be the least effective, although it resulted in 237.26 L/kg VS of biogas and 143.89 L/kg VS of methane, with an average methane content of 60%, corresponding to a 221% increase in biogas over the untreated sample.

The EDTA + OA treatment produced 373.00 L/kg VS of biogas and 226.42 L/kg VS of methane, with a methane content of 60.70%, corresponding to a 404% increase in biogas relative to the untreated substrate.

Fenton pretreatment generated 388.67 L/kg VS of biogas and 263.54 L/kg VS of methane, with a methane content of 67.81%, which corresponds to a 425% increase in biogas over the untreated WG shavings.

The largest amount of biogas from WG was obtained using 2% borax solution, reaching 588.14 L/kg VS of biogas and 405.75 L/kg VS of methane, with a methane content of 68.99%. This corresponds to a 695% increase in biogas compared to the untreated sample and represents the highest biogas yield among all WG pretreatments.

At the same time, the highest concentration of total phenols was found for the mixture of borax and water (843 mg/L,

Figure 4). The addition of sodium sulfate (SS) to the 2% borax solution reduced the amount of biogas obtained by approximately 12%. The 2% borax + 0.5% SS pretreatment resulted in 519.51 L/kg VS of biogas and 360.34 L/kg VS of methane, with a methane content of 69.36%, and the concentration of phenols decreased to 663 mg/L. Dhayalan et al. [

19] similarly demonstrated that borax–sulfate mixtures improve biogas production, although biogas composition was not measured in their study, and the process lasted twice as long.

The remaining chemical treatment methods (Fenton, SS, and EDTA + OA) also significantly increased cumulative biogas production. The average amount of biogas for these three pretreatments was approximately 390 L/kg VS, which confirms the improved biodegradability of WG shavings after chemical modification. In

Figure 3, it can also be observed that the biogas curves for Fenton and EDTA pretreatment are flattened compared to the other methods, indicating a depletion of available substrate or other limiting factors. Application of strong oxidizing agents (e.g., in Fenton) and chelating compounds (e.g., EDTA) may lead to the formation of toxic byproducts, such as aromatic aldehydes, quinones, or complexed heavy metals (e.g., Cr-EDTA complexes), which can disrupt microbial metabolism—particularly methanogenesis. These substances, along with residual oxidants (e.g., H

2O

2) or organic acids, could alter the microbial community or inhibit enzymatic activity in the later digestion phase. With regard to total phenols in water samples, no relationship was observed between concentration and the amount of biogas obtained. Phenols are only one group of potential inhibitors. Other compounds—such as tannins, sulfides, low-molecular-weight fatty acids, or transition metal complexes—could also contribute to inhibition.

In the context of these inhibitory effects, it is important to emphasize that anaerobic biodegradation cannot proceed when microbial toxicity exceeds critical thresholds. Chromium ions, phenolic compounds, or oxidative by-products formed during pretreatment may significantly impair methanogenic and acetogenic communities. The relevance of standardized microbial toxicity assessments is well established, and ISO/OECD microbiological test systems represent the current gold standard for evaluating inhibitory effects on microbial activity. A recent review provides a comprehensive overview of these methods, highlighting their applicability to studies where metals, tanning chemicals, or pretreatment residues may inhibit anaerobic digestion [

69].

The research of Agustini et al. [

35] reveals that removal of tanning agent is needed to obtain higher biogas production and higher methane-containing biogas. It was found that in the presence of a tanning agent, the total organic carbon decreased, which could have had an impact on the biogas production process. The fermentation test with chromium-containing sludge and vegetable tanned shavings showed that the maximum biogas production was found to be 27.9 mL/gVSS.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

One-way ANOVA confirmed that the pretreatment method had a statistically significant effect on both cumulative biogas and methane production for all substrate types (

Table 3). For WB shavings, significant differences were observed among pretreatments for biogas (F = 95.66,

p = 3.05 × 10

−9) and methane yields (F = 113.64,

p = 1.12 × 10

−9). Similarly, strong effects were found for WW shavings (biogas: F = 193.25,

p = 2.02 × 10

−9; methane: F = 413.58,

p = 4.68 × 10

−11) and WG shavings (biogas: F = 87.78,

p = 1.44 × 10

−11; methane: F = 93.86,

p = 8.59 × 10

−12). These results confirm that the choice of pretreatment significantly influences anaerobic digestion performance in all tanning categories. Treatments involving organic acids and borax-based combinations consistently formed statistically distinct high-yield groups, whereas water and Fenton pretreatments clustered among the lowest-performing groups.

4. Conclusions

Appropriate pre-treatment can increase the feasibility of producing energy from chromium leather waste. If implemented, this process can reduce costs for energy consumption and waste utilization, eliminate solid waste, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the microbiological degradation of tannery waste. As these results are based on batch anaerobic digestion tests, the study should be regarded as preliminary, providing indicative trends rather than definitive predictions of full-scale performance.

Pretreatment of chromium leather waste is crucial for enhancing biogas yield, with methods such as Fenton, oxalic acid (OA), EDTA, and their combinations showing marked improvements compared to untreated conditions. Specifically, the combination of 10 mM EDTA and 2% OA has demonstrated significant potential, increasing both methane content and overall biogas output. In addition, oxalic acid consistently enhances methane production from different tanned shavings. Fenton treatment is particularly effective for synthetic tanned shavings, and water pretreatment is beneficial for olive-tanned shavings.

Statistical analysis (one-way ANOVA) demonstrated that the pretreatment type had a significant effect on both biogas and methane production for all three substrate types. Acidic and borax-based pretreatments formed the highest-yield groups, whereas water and Fenton treatments produced significantly lower yields. These findings confirm that pretreatment selection is a key determinant of anaerobic digestion performance.

The data highlights the importance of pretreatment in enhancing biogas yield from the substrate. Preliminary mechanistic interpretation suggests that chemical pretreatments enhance digestibility by partially disrupting the collagen matrix and increasing the availability of soluble organic compounds. Acidic and chelating agents (e.g., OA, EDTA, and their mixtures) likely promote solubilization and destabilization of cross-linked structures, facilitating microbial access. In chrome-tanned shavings, pretreatment-induced leaching of Cr (III) reduces its known inhibitory impact on methanogenic microorganisms. For Fenton pretreatment, oxidative modification of organic matter may contribute to improved accessibility despite potential inhibitory effects of ROS on methanogenesis. These combined chemical effects help explain the observed increases in biogas and methane yields. Fenton treatment stands out as the most effective pretreatment method, consistently producing the highest biogas yield throughout the fermentation period. Other pretreatment methods, such as 10 mM EDTA + 2% OA and 2% Borax + 0.5% Na2SO4, also show promising results in terms of biogas production. Further research could explore optimization strategies for pretreatment methods to maximize biogas production efficiency and sustainability. The observed variability underscores the need for further research to understand the mechanisms behind these differences and to optimize pretreatment methods for maximum biogas production efficiency. Additionally, exploring the economic and environmental impacts in greater detail is essential to ensure the sustainability and scalability of these processes, aiming to maximize benefits while minimizing resource use and costs. From a practical perspective, the scalability and cost-effectiveness of the most promising pretreatments should also be considered. Water and borax treatments appear potentially more economically favorable due to low reagent requirements and minimal handling needs, whereas acid-, EDTA-, or Fenton-based pretreatments may involve higher chemical consumption, operational complexity, and downstream handling. A preliminary cost–benefit and scalability assessment is therefore important to determine which strategies are suitable for larger-scale applications. Preliminary technoeconomic analysis or life cycle assessment is recommended to validate the environmental and financial viability of these pretreatment methods at scale. Further research should also include a detailed cost–benefit and lifecycle evaluation to compare the most promising pretreatment strategies, including both chemical and non-chemical options, in terms of environmental burden, safety, and economic feasibility.

Another important aspect concerns the environmental management of the streams generated during the process. The liquid fraction obtained after pretreatment contains dissolved organic matter, residual reagents (such as EDTA, oxalic acid, borate, or sulfate), iron species from Fenton oxidation, and—depending on the tanning type—chromium or vegetable polyphenols. Appropriate post-treatment of this liquid phase would be necessary before discharge or reuse, potentially involving coagulation–flocculation, adsorption, ion exchange, or advanced oxidation. Similarly, the digestate may accumulate chromium, phenolic compounds, or chelating agents, which could limit its direct agricultural application and require stabilization or specific handling. These aspects may constitute the environmental bottleneck of the entire process and should be comprehensively assessed in future studies.

Future research should also address the upscaling potential of the proposed processes. While batch tests provide essential baseline data, further studies using continuous or semi-continuous reactors are necessary to evaluate process stability, long-term performance, and operational feasibility under realistic conditions. The integration of pretreatment methods into existing anaerobic digestion systems should also consider technical, economic, and environmental aspects to ensure scalability and industrial applicability.