Modeling Sustainable Marketing Innovation Strategies in the Pharmaceutical Industry: A Systemic Approach from Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Foundations: Innovation and Marketing Innovation

2.2. Conceptualizing the Six Marketing-Innovation Dimensions

2.3. Systemic Modeling and Fuzzy Analytical Methods

2.4. Empirical Evidence in Pharmaceuticals and Emerging Markets

2.5. Identified Research Gaps

- 1.

- Absence of a systemic perspective on marketing innovation.

- 2.

- Methodological limitations in capturing interdependencies.

- 3.

- Contextual gap for emerging markets, especially Indonesia.

2.6. Innovative Contributions and Positioning of the Present Study

- Theoretical contribution: It reconceptualizes marketing innovation in pharmaceuticals as a systemic configuration rather than a set of isolated categories, thereby advancing theory on how marketing capabilities co-evolve with organizational and process innovations;

- Methodological contribution: It applies an integrated fuzzy-ISM framework (combining expert linguistic judgments and systemic modeling) to map directional influences and to reveal reciprocal or cyclical patterns that ranking methods cannot detect;

- Empirical/contextual contribution: By situating the analysis in Indonesia—where prior Fuzzy AHP work established the relevance of the same six dimensions [48]—the study provides context-sensitive insights and prescriptive implications for sustainable marketing strategy in emerging-market pharmaceutical firms.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Conceptual Definitions of the Innovation Dimensions

3.3. Theoretical Basis for Selecting the Six Innovation Dimensions

3.4. Data and Expert Profiles

3.5. Analytical Procedure

3.6. Validity and Reliability

3.7. Research Context

3.8. Theoretical Foundations for Systemic Innovation Interdependencies

4. Results

4.1. Structural Self-Interaction Matrix (SSIM)

4.2. Binary Matrix (Significant Relationships > α)

4.3. Initial and Final Reachability Matrices

4.4. Level Partition Results

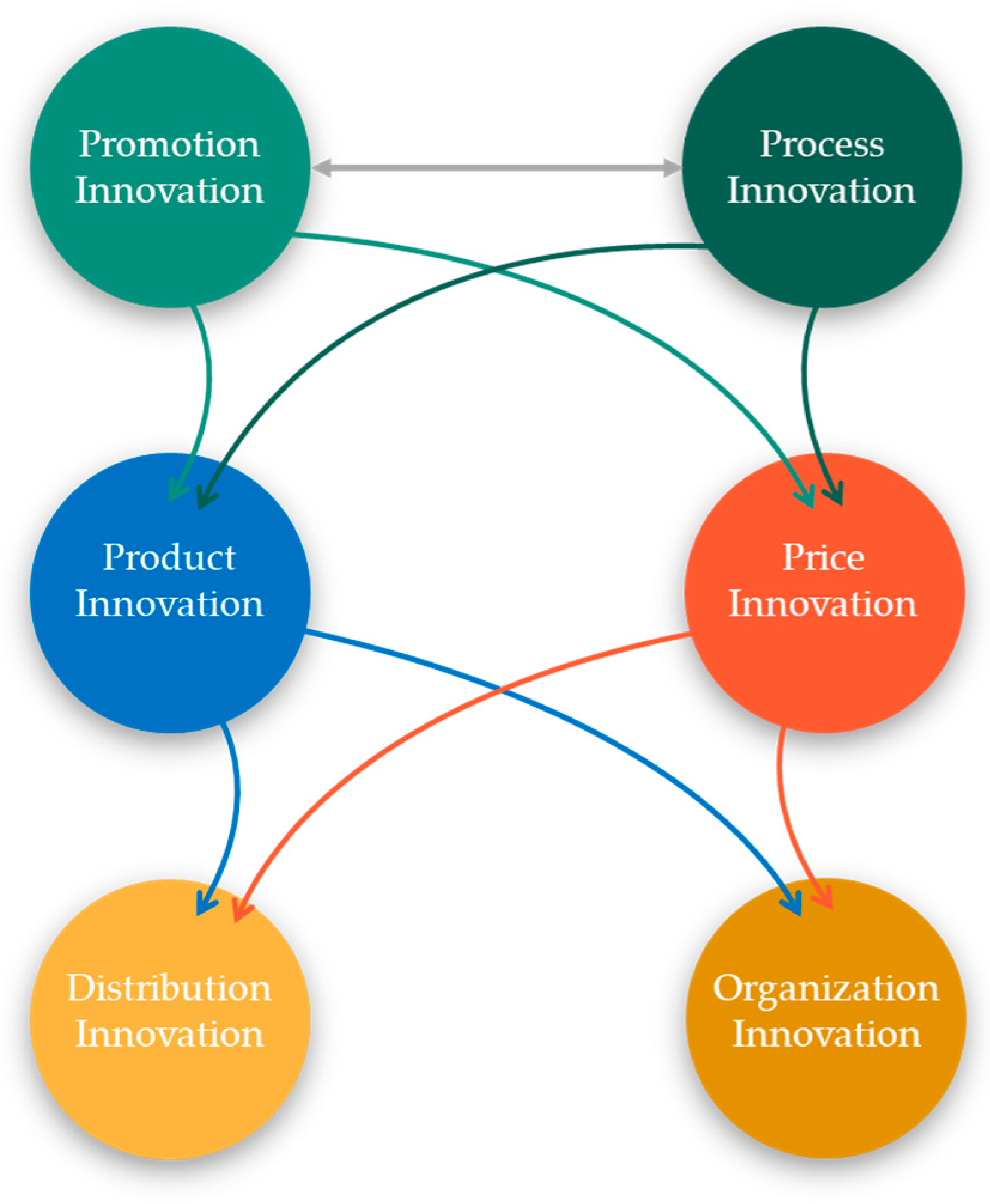

4.5. Integrated Cycle Model of Sustainable Marketing Innovation

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Policy Implications

5.4. Methodological Contributions

5.5. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Code | Description |

| NI | No Influence |

| II | Indirect Influence |

| SI | Strong Influence |

| WI | Weak Influence |

- Select only one category per item;

- Answer all questions;

- There are 30 evaluation items across six tables;

- Please base your answers on your professional knowledge, experience, and judgment.

| No. | A: Process Innovation | B: Affected Dimension | NI | II | SI | WI |

| 1 | Process Innovation | Product Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 2 | Process Innovation | Organizational Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 3 | Process Innovation | Price Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 4 | Process Innovation | Promotion Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 5 | Process Innovation | Distribution Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| No. | A: Product Innovation | B: Affected Dimension | NI | II | SI | WI |

| 1 | Product Innovation | Process Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 2 | Product Innovation | Organizational Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 3 | Product Innovation | Price Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 4 | Product Innovation | Promotion Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 5 | Product Innovation | Distribution Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| No. | A: Organizational Innovation | B: Affected Dimension | NI | II | SI | WI |

| 1 | Organizational Innovation | Process Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 2 | Organizational Innovation | Product Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 3 | Organizational Innovation | Price Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 4 | Organizational Innovation | Promotion Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 5 | Organizational Innovation | Distribution Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| No. | A: Price Innovation | B: Affected Dimension | NI | II | SI | WI |

| 1 | Price Innovation | Process Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 2 | Price Innovation | Product Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 3 | Price Innovation | Organizational Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 4 | Price Innovation | Promotion Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 5 | Price Innovation | Distribution Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| No. | A: Promotion Innovation | B: Affected Dimension | NI | II | SI | WI |

| 1 | Promotion Innovation | Process Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 2 | Promotion Innovation | Product Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 3 | Promotion Innovation | Organizational Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 4 | Promotion Innovation | Price Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 5 | Promotion Innovation | Distribution Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| No. | A: Distribution Innovation | B: Affected Dimension | NI | II | SI | WI |

| 1 | Distribution Innovation | Process Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 2 | Distribution Innovation | Product Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 3 | Distribution Innovation | Organizational Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 4 | Distribution Innovation | Price Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 5 | Distribution Innovation | Promotion Innovation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

Appendix B

| Process Innovation | Product Innovation | Organization Innovation | Price Innovation | Promotion Innovation | Distribution Innovation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process Innovation | – | 2 | 3 | – | 2 | 3 |

| Product Innovation | 3 | – | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Organization Innovation | 3 | 3 | – | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Price Innovation | 3 | 3 | 2 | – | 2 | 3 |

| Promotion Innovation | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | – | 2 |

| Distribution Innovation | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | – | – |

Appendix C

| Process Innovation | Product Innovation | Organization Innovation | Price Innovation | Promotion Innovation | Distribution Innovation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process Innovation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Product Innovation | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Organization Innovation | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Price Innovation | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Promotion Innovation | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| Distribution Innovation | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

Appendix D

| Process Innovation | Product Innovation | Organization Innovation | Price Innovation | Promotion Innovation | Distribution Innovation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process Innovation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Product Innovation | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Organization Innovation | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Price Innovation | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Promotion Innovation | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Distribution Innovation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Appendix E

| Process Innovation | Product Innovation | Organization Innovation | Price Innovation | Promotion Innovation | Distribution Innovation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process Innovation | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Product Innovation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Organization Innovation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Price Innovation | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Promotion Innovation | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Distribution Innovation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Appendix F

| Process Innovation | Product Innovation | Organization Innovation | Price Innovation | Promotion Innovation | Distribution Innovation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process Innovation | 1 | 1 * | 1 * | 1 * | 1 * | 1 |

| Product Innovation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Organization Innovation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Price Innovation | 1 | 1 | 1 * | 1 | 1 * | 1 |

| Promotion Innovation | 1 | 1 * | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 * |

| Distribution Innovation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 * | 1 |

Appendix G

| Element | Reachability Set (R) | Antecedent Set (A) | Intersection (R ∩ A) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process Innovation | {Distribution Innovation, Price Innovation, Organization Innovation, Product Innovation, Promotion Innovation, Process Innovation} | {Distribution Innovation, Price Innovation, Organization Innovation, Product Innovation, Promotion Innovation, Process Innovation} | {Distribution Innovation, Price Innovation, Organization Innovation, Product Innovation, Promotion Innovation, Process Innovation} |

| Product Innovation | {Distribution Innovation, Price Innovation, Organization Innovation, Product Innovation, Promotion Innovation, Process Innovation} | {Distribution Innovation, Price Innovation, Organization Innovation, Product Innovation, Promotion Innovation, Process Innovation} | {Distribution Innovation, Price Innovation, Organization Innovation, Product Innovation, Promotion Innovation, Process Innovation} |

| Organization Innovation | {Distribution Innovation, Price Innovation, Organization Innovation, Product Innovation, Promotion Innovation, Process Innovation} | {Distribution Innovation, Price Innovation, Organization Innovation, Product Innovation, Promotion Innovation, Process Innovation} | {Distribution Innovation, Price Innovation, Organization Innovation, Product Innovation, Promotion Innovation, Process Innovation} |

| Price Innovation | {Distribution Innovation, Price Innovation, Organization Innovation, Product Innovation, Promotion Innovation, Process Innovation} | {Distribution Innovation, Price Innovation, Organization Innovation, Product Innovation, Promotion Innovation, Process Innovation} | {Distribution Innovation, Price Innovation, Organization Innovation, Product Innovation, Promotion Innovation, Process Innovation} |

| Promotion Innovation | {Distribution Innovation, Price Innovation, Organization Innovation, Product Innovation, Promotion Innovation, Process Innovation} | {Distribution Innovation, Price Innovation, Organization Innovation, Product Innovation, Promotion Innovation, Process Innovation} | {Distribution Innovation, Price Innovation, Organization Innovation, Product Innovation, Promotion Innovation, Process Innovation} |

| Distribution Innovation | {Distribution Innovation, Price Innovation, Organization Innovation, Product Innovation, Promotion Innovation, Process Innovation} | {Distribution Innovation, Price Innovation, Organization Innovation, Product Innovation, Promotion Innovation, Process Innovation} | {Distribution Innovation, Price Innovation, Organization Innovation, Product Innovation, Promotion Innovation, Process Innovation} |

References

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Theory of Economic Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy; Harper & Brothers: New York, NY, USA, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Boer, H.; During, W.E. Innovation, what innovation? A comparison between product, process and organisational innovation. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2001, 22, 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowonder, B.; Dambal, A.; Kumar, S.; Shirodkar, A. Innovation strategies for creating competitive advantage. Res.-Technol. Manag. 2010, 53, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMasi, J.A.; Hansen, R.W.; Grabowski, H.G. The price of innovation: New estimates of drug development costs. J. Health Econ. 2003, 22, 151–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, D.G.; Amato, L.H.; Troyer, J.L.; Stewart, O.J. Innovation and misconduct in the pharmaceutical industry. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 144, 1052–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.J.; Botura Junior, G.; Riccó Plácido da Silva, J.C. Innovation and marketing strategy: A systematic review. J. Strateg. Mark. 2023, 31, 519–542. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, B. Contemporary Trends in Innovative Marketing Strategies; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ajmera, P.; Jain, V. A Fuzzy Interpretive Structural Modeling Approach for Evaluating the Factors Affecting Lean Implementation in Indian Healthcare Industry. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2020, 11, 376–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attri, R.; Attri, R.; Dev, N.; Sharma, V. Interpretive Structural Modelling (ISM) Approach: An Overview. Res. J. Manag. Sci. 2013, 2, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Chen, H. An ISM-based methodology for interrelationships of critical success factors for construction projects in ecologically fragile regions: Take Korla, China as an example. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.Y. Applications of the extent analysis method on fuzzy AHP. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1996, 95, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, J.J. Fuzzy hierarchical analysis. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1985, 17, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N. SmartISM 2.0: A roadmap and system to implement fuzzy ISM and fuzzy MICMAC. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Srivastava, S.K.; Srivastava, R.K.; Parveen, Z. Risk propagation and its impact on performance in food processing supply chain: A fuzzy interpretive structural modeling-based approach. J. Model. Manag. 2016, 11, 660–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damle, M.; Krishnamoorthy, B. Identifying critical drivers of innovation in the pharmaceutical industry using TOPSIS method. MethodsX 2022, 9, 101677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, W.E.; Sinkula, J.M. Market orientation, learning orientation and product innovation: Delving into the organization’s black box. J. Mark.-Focus. Manag. 2002, 5, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.K.; Kim, N.; Srivastava, R.K. Market orientation and organizational performance: Is innovation a missing link? J. Mark. 1998, 62, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sephani, A.R.; Rudijanto, A. Nutrisi parenteral: Literature review. J. Ilm. 2023, 12, 142–156. [Google Scholar]

- Fonjungo, F.; Banerjee, D.; Abdulah, R.; Diantini, A.; Kusuma, A.S.W.; Permana, M.Y.; Suwantika, A.A. Sustainable financing for new vaccines in Indonesia: Challenges and strategies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djurian, A.; Makino, T.; Lim, Y.; Sengoku, S.; Kodama, K. Trends of business-to-business transactions to develop innovative cancer drugs. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, Y.; Wang, H.; Kodama, K.; Sengoku, S. Drug discovery firms and business alliances for sustainable innovation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Lee, I.; Kim, H.; Shin, K. Factors affecting outbound open innovation performance in bio-pharmaceutical industry: Focus on out-licensing deals. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, S.; Kadama, K.; Sengoku, S. Characteristics and classification of technology sector companies in digital health for diabetes. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilia, F.; Bacenetti, J.; Sugni, M.; Matarazzo, A.; Orsi, L. From waste to product: Circular economy applications from sea urchin. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.R.; Kyriakopoulos, G.L.; Streimikiene, D.; Streimikis, J. Drivers of proactive environmental strategies: Evidence from the pharmaceutical industry of Asian economies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.; Frade, R.; Ascenso, R.; Martinho, F.; Martinho, D. Determinants of internationalization as levers for sustainability: A study of the Portuguese pharmaceutical sector. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovljevic, M.; Cerda, A.A.; Liu, Y.; García, L.; Timofeyev, Y.; Krstic, K.; Fontanesi, J. Sustainability challenge of Eastern Europe: Historical legacy, Belt and Road Initiative, population aging and migration. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.Y. What makes companies to survive over a century? The case of Dongwha Pharmaceutical in the Republic of Korea. Sustainability 2022, 14, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghondaghsaz, N.; Chokparova, Z.; Engesser, S.; Urbas, L. Managing the tension between trust and confidentiality in mobile supply chains. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niwash, M.N.K.; Cek, K.; Eyupoglu, S.Z. Intellectual capital and competitive advantage and the mediation effect of innovation quality and speed, and business intelligence. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Wu, F.; Qu, Y.; Guo, K.; Du, X. Green innovation’s promoting impact on the fusion of industry and talent: The case of pharmaceutical industry in the Yangtze River Economic Belt of China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habiyaremye, A. Optimal patent protection length for vital pharmaceuticals in the age of COVID-19. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fikri, M.K.; Firmansyah, F. Analysis of market structure and performance on the go public pharmaceutical industry in Indonesia. JEJAK J. Econ. Policy 2023, 15, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlangga, H.; Sifatu, W.O.; Wibisono, D.; Siagian, A.O.; Salam, R.; Mas’adi, M.; Oktarini, R.; Manik, C.D.; Nurhadi, A.; Sunarsi, D.; et al. Pharmaceutical business competition in Indonesia: A review. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 617–623. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, R.M. Contemporary Strategy Analysis; Wiley: Andover, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hillerbrand, R.; Werker, C. Ethical and strategic challenges in pharmaceutical R&D. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2019, 25, 1497–1517. [Google Scholar]

- Compagnucci, M.C.; Nilsson, N.; Stankovski Wagner, P.; Olsson, C.; Fenwick, M.; Minssen, T.; Szkalej, K. Non-fungible tokens as a framework for sustainable innovation in pharmaceutical R&D: A smart contract-based platform for data sharing and rightsholder protection. J. Intellect. Prop. Law Pract. 2023, 18, 441–452. [Google Scholar]

- Caiazza, R.; Volpe, T.; Stanton, J.L. Innovation in agro-foods: A comparative analysis of value chains. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2016, 28, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fain, D.; Volinsky, C.; Madigan, D. Infinite innovation and competition in the product life cycle. Mark. Sci. 2018, 37, 451–467. [Google Scholar]

- Hamsal, S.; Sundari, E. Strategi Pemasaran Usaha Produk Farmasi Masa Pandemi COVID-19 di PT. Ferron Par Pharmaceutical (Studi Kasus Peningkatan Volume Penjualan Produk Farmasi). SYARIKAT: J. Rumpun Ekon. Syariah 2022, 5, 46–54, Universitas Islam Riau. p-ISSN 2654-3923; e-ISSN 2621-6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomać-Pierzecka, E. Pharmaceutical Companies in the Light of the Idea of Sustainable Development—An Analysis of Selected Aspects of Sustainable Management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ievseitseva, O.; Mihalatii, O. The Importance of Marketing Innovations as the Basis of Management of the Enterprise’s Competitiveness. Management 2023, 38, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomać-Pierzecka, E. Innovation as an Attribute of the Sustainable Development of Pharmaceutical Companies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BPOM. Laporan Tahunan Badan POM 2023; BPOM RI: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2023; Available online: https://pusakom.pom.go.id/report/download/laporan-tahunan-2023 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Kementerian Kesehatan RI. Profil Kesehatan Indonesia Tahun 2023; Kementerian Kesehatan RI: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2023; Available online: https://repository.kemkes.go.id/book/1276 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Zuldekra; Hasbullah, R.; Asikin, Z.; Novianti, T. Prioritizing Sustainable Marketing Innovation for Pharmaceutical Firms in Indonesia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/Eurostat. Oslo Manual 2018: Guidelines for Collecting, Reporting and Using Data on Innovation; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L. Marketing Management, 16th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Warfield, J.N. Developing Interconnected Matrices in Structural Modeling. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1973, SMC-3, 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ragade, R.K. Fuzzy Interpretive Structural Modeling. J. Cybern. 1976, 6, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy Sets. Inf. Control 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Laarhoven, P.J.M.; Pedrycz, W. A Fuzzy Extension of Saaty’s Priority Theory. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1983, 11, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh Lotfi, F.; Allahviranloo, T.; Pedrycz, W.; Shahriari, M.; Sharafi, H.; Razipour Ghaleh Jough, S. Fuzzy Decision Analysis: Multi Attribute Decision Making Approach; Studies in Computational Intelligence Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay, A. A Critical Study of Joseph A. Schumpeter’s Theory of Economic Development. Int. J. Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 8, 452–466. [Google Scholar]

- Marimin, D.; Suharjito, H.; Utama, N.D.; Astuti, R.; Martini, S. Teknik dan Analisis Pengambilan Keputusan Fuzzy dalam Manajemen Rantai Pasok; IPB Press: Bogor City, Indonesia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe, S.J.A. Schumpeter and the Theory of Economic Evolution (One Hundred Years Beyond the Theory of Economic Development); Papers on Economics and Evolution; Max Planck Institute of Economics: Jena, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, S.G.; Epstein, D. The Price of Innovation—The Role of Drug Pricing in Financing Pharmaceutical Innovation: A Conceptual Framework. J. Market Access Health Policy 2019, 7, 1583536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakouhi, F.; Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, R.; Baboli, A.; Bozorgi-Amiri, A. A Competitive Pharmaceutical Supply Chain under the Marketing Mix Strategies and Product Life Cycle with a Fuzzy Stochastic Demand. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 324, 1369–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeyer, X.; Santos, S.C.; Liguori, E.; Walsh, S.T.; Mahto, R.V. The Ever-Evolving Relationship between Technology, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship: Current State and Future Research Needs. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 215, 124059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiazza, R.; Volpe, T. How Campanian SMEs Can Compete in the Global Agro-Food Industry. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2013, 19, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiazza, R.; Audretsch, D.B.; Volpe, T.; Singer, J. Policy and Institutions Facilitating Entrepreneurial Spin-Offs: USA, Asia and Europe. J. Entrep. Public Policy 2014, 3, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiazza, R.; Volpe, T. Main Rules and Actors of the Italian System of Innovation: How to Become Competitive in Spin-Off Activity. J. Enterprising Communities 2014, 8, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, B.; Dörfler, V.; MacBryde, J. Navigating the open innovation paradox: An integrative framework for adopting open innovation in pharmaceutical R&D in developing countries. J. Technol. Transf. 2023, 48, 2204–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzules-Falcones, W.; Novillo-Villegas, S. Innovation Capacity, Entrepreneurial Orientation, and Flexibility: An Analysis from Industrial SMEs in Ecuador. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, U.T.; Velidandi, A. An Overview on the Role of Government Initiatives in Nanotechnology Innovation for Sustainable Economic Development and Research Progress. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, P.H. Joseph A. Schumpeter’s Perspective on Innovation. Int. J. Econ. Commer. Manag. 2015, 3, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Yosefine da Costa, Y.; Hubeis, M.; Palupi, N.S. Pengembangan Strategi dan Kelayakan Usaha pada Industri Farmasi Lokal. J. Manaj. Bisnis Farm. 2021, 16, 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Asikin, Z.; Baker, D.; Villano, R.; Daryanto, A. The Use of Innovation Uptake in Identification of Business Models in the Indonesian Smallholder Cattle Value Chain. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2024, 14, 845–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhmacher, A. Pharma Innovation: How Evolutionary Economics Is Shaping the Future of Pharma R&D. Drug Discov. Today 2024, 29, 104222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKelvey, M.; Saemundsson, R.J. Biopharmaceutical Entrepreneurship, Open Innovation, and the Knowledge Economy. J. Bus. Innov. 2023, 45, 210–229. [Google Scholar]

- Petelos, E.; Antonaki, D.; Angelaki, E.; Lemonakis, C.; Alexandros, G. Enhancing Public Health and SDG 3 Through Sustainable Agriculture and Tourism. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvulit, Z.; Maznyk, L.; Horbal, N.; Melnyk, O.; Dluhopolska, T.; Bartnik, B. Harmonizing the Interplay Between SDG 3 and SDG 10 in the Context of Income Inequality: Evidence from the EU and Ukraine. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, C.; Macharete, R.; Rodrigues, C.A.; Kamia, F.; Moreira, J.; Freitas, C.R.; Nascimento, M.; Gadelha, C.G. Global Knowledge Asymmetries in Health: A Data-Driven Analysis of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Sustainability 2025, 17, 6449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Position/Profession | Institution | Core Expertise | Additional Competence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Professor of Pulmonology and Respiratory Medicine; Director of Postgraduate Programs | University of Indonesia; YARSI; Griffith University | Pulmonology, Respiratory Medicine, Environmental Health | Epidemiology, health policy, cross-national research |

| 2 | Consultant and Executive Coach; Former Marketing Director | STEM Healthcare; Pharos; Fresenius Kabi; Merck | Pharmaceutical Marketing Management | Brand management, sales excellence, leadership |

| 3 | Professor of Surgical Oncology | Udayana University | Surgical Oncology, Clinical Medicine | Cancer management, clinical research |

| 4 | Specialty Care Medical Lead (Regional) | Pfizer | Medical Affairs, Clinical Trials, Market Access | HEOR, compliance, pharmacovigilance |

| 5 | Country Group Head | Wellesta Indonesia | Strategic Management and Pharmaceutical Business Leadership | Business development, market expansion |

| 6 | Medical and Market Access Head | PT Anvita Pharma Indonesia | Market Access Strategy and Medical Affairs | Health economics, policy advocacy |

| 7 | Director General of Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices; Former Head of BPOM | Ministry of Health of Indonesia; BPOM | National Pharmaceutical Regulation and Policy | Governance, industry supervision |

| 8 | Director of Pharmaceutical Management and Services | Ministry of Health of Indonesia | Pharmaceutical Supply Chain and Distribution Management | Hospital service quality, regulatory compliance |

| Step | Description | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fuzzification: mapping linguistic judgments into numeric representations. | [53,54] |

| 2 | Pairwise recording and symbolic encoding. | [51,54] |

| 3 | Aggregation: maximum-rule aggregation of individual matrices. | [52,57] |

| 4 | Thresholding and binary conversion to form initial reachability. | [52,56] |

| 5 | Iterative transitive closure to obtain final reachability. | [51,56] |

| 6 | Level partitioning for structural interpretation. | [56,58] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zuldekra; Hasbullah, R.; Asikin, Z.; Novianti, T. Modeling Sustainable Marketing Innovation Strategies in the Pharmaceutical Industry: A Systemic Approach from Indonesia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11101. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411101

Zuldekra, Hasbullah R, Asikin Z, Novianti T. Modeling Sustainable Marketing Innovation Strategies in the Pharmaceutical Industry: A Systemic Approach from Indonesia. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11101. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411101

Chicago/Turabian StyleZuldekra, Rokhani Hasbullah, Zenal Asikin, and Tanti Novianti. 2025. "Modeling Sustainable Marketing Innovation Strategies in the Pharmaceutical Industry: A Systemic Approach from Indonesia" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11101. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411101

APA StyleZuldekra, Hasbullah, R., Asikin, Z., & Novianti, T. (2025). Modeling Sustainable Marketing Innovation Strategies in the Pharmaceutical Industry: A Systemic Approach from Indonesia. Sustainability, 17(24), 11101. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411101