A Cloud Model-Based Framework for a Multi-Scale Seismic Robustness Evaluation of Water Supply Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Selecting Quantitative Robustness Indicators

2.2. Quantifying WSN Robustness

2.2.1. Node Structural Failure Analysis

2.2.2. Node Water Shortages Analysis

2.2.3. Node Degree Analysis

2.3. Seismic Robustness Assessment of WSN Based on Cloud Model

2.3.1. Fundamental and Computational Techniques of the Cloud Model

2.3.2. Robustness Evaluation Based on Cloud Models

- (1)

- Based on M simulations, the RCG is applied to determine nodal cloud numerical characteristics. The expectation Exi, entropy Eni, Hei of node i are shown in Equations (11), (12), and (13), respectively. Here, R(i,m) denotes the i-th nodal robustness in the m-th simulation (m = 1, 2, …, M). M is the total number of simulations.

- (2)

- Total cloud droplet number is denoted as Ncloud. The FCG is adopted to generate the quantitative values xi,k of Ncloud cloud droplets and the membership degrees yi,k of the concept represented by each cloud droplet. Specifically, xi,k follows a normal random distribution with an expected value of Exi and a standard deviation of Enni; Enni follows a normal random distribution with an expected value of Eni and a standard deviation of Hei. yi,k is the membership degree (k = 1, 2, …, Ncloud), determining by Equation (13).

- (3)

- Obtain the robustness evaluation cloud chart.

3. Case Study

3.1. Case Study Introduction

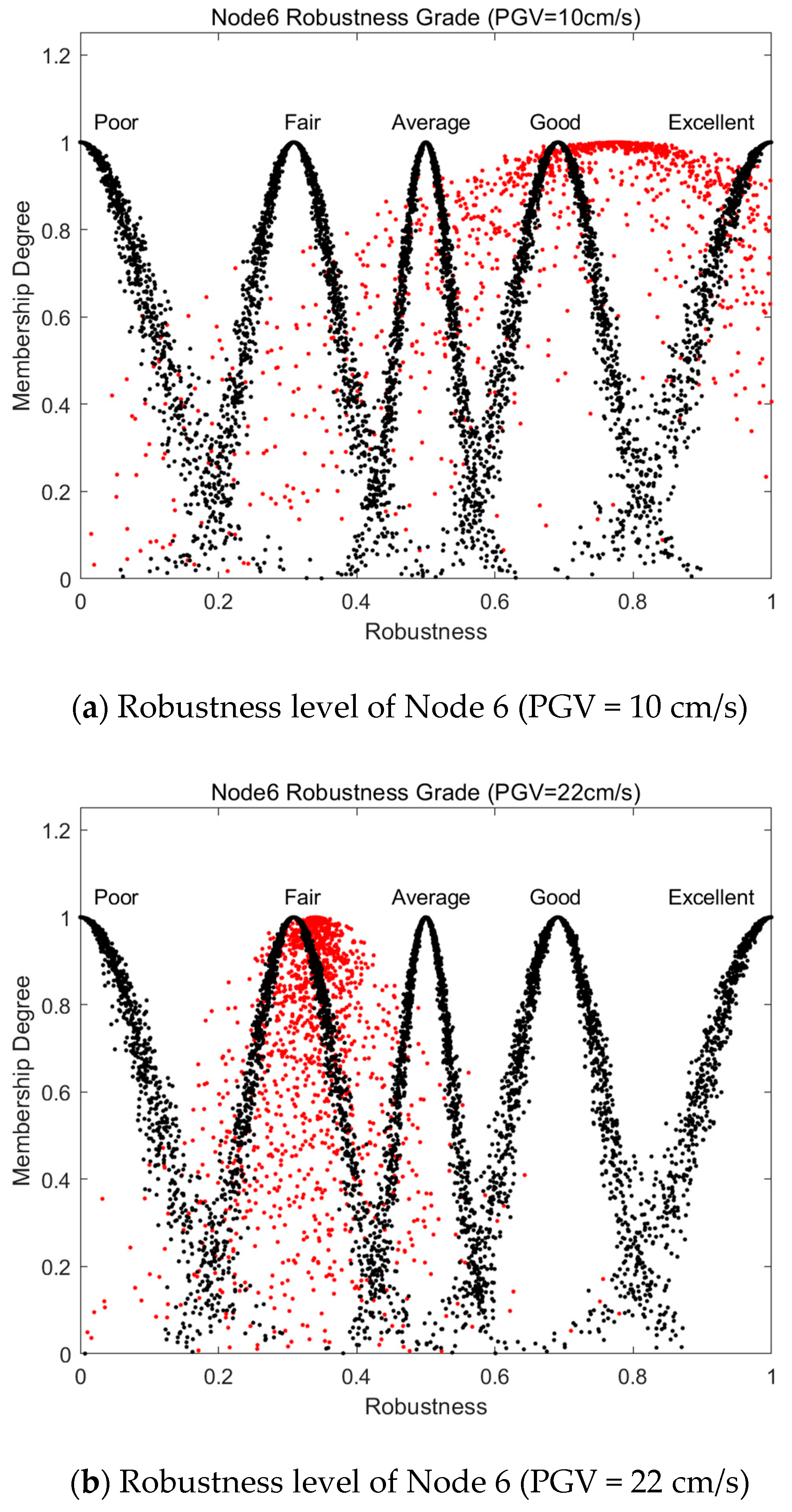

3.2. Result Analysis

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- As peak seismic velocity increases, the robustness of nodes and WSN also markedly decreases; however, the reliability and stability of the robustness results correspondingly increase. Nodes with identical robustness values can be effectively evaluated for their reliability and stability based on their cloud distributions.

- (2)

- This method can effectively evaluate WSN robustness and intuitively reflect its reliability and stability. Meanwhile, it converts quantitative robustness evaluation results into qualitative assessments, rendering them more readily comprehensible. The analysis results exhibit considerable dispersion.

5. Limitations and Future Research Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bloom, D.E.; Canning, D.; Fink, G. Urbanization and the Wealth of Nations. Science 2008, 319, 772–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenghelis, D. Cities, Wealth, and the Era of Urbanization. In National Wealth: What Is Missing, Why It Matters; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 315–340. ISBN 978-0-19-184411-9. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, C. Urbanization: Processes and Driving Forces. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2019, 62, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, E.; Vale, B.; Vale, R. Growth and Resources. In Collapsing Gracefully: Making a Built Environment that Is Fit for the Future; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 207–230. ISBN 978-3-030-77782-1. [Google Scholar]

- Apostolska, R.; Sheshov, V.; Salic Makreska, R.; Stojmanovska, M.; Bojadjieva, J.; Nanevska, A.; Kolic, M.; Mrvaljevic, D.; Zajazi, K.; Atalić, J.; et al. Enhancing Earthquake Disaster Risk Assessment: Insights from Pandemic Circumstances, Case Studies, and Lessons Learned. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 6777–6799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Che, A.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, F. Risk Assessment of Seismic Landslides Based on Analysis of Historical Earthquake Disaster Characteristics. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2020, 79, 2271–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Wang, F.; Sun, P. Landslide Hazards Triggered by the 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake, Sichuan, China. Landslides 2009, 6, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, C.; Rest, M. Calculating Risk, Denying Uncertainty: Seismicity and Hydropower Development in Nepal. Himalaya 2017, 37, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Birinci, Ş. Technical Efficiency of Post-Disaster Health Services Interventions: The 2023 Kahramanmaraş Earthquake in Turkey. Int. J. Health Manag. Tour. 2023, 8, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Yuan, H.; Du, G.; Zhang, M. A Demand-Based Three-Stage Seismic Resilience Assessment and Multi-Objective Optimization Method of Community Water Distribution Networks. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 250, 110279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, J.; Loureiro, D.; Cabral, M.; Covas, D. Comprehensive Resilience Assessment Framework for Water Distribution Networks. Water 2024, 16, 2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneau, M.; Chang, S.E.; Eguchi, R.T.; Lee, G.C.; O’Rourke, T.D.; Reinhorn, A.M.; Shinozuka, M.; Tierney, K.; Wallace, W.A.; Von Winterfeldt, D. A Framework to Quantitatively Assess and Enhance the Seismic Resilience of Communities. Earthq. Spectra 2003, 19, 733–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelieri, A.; Soldi, D.; Archetti, F. Network Analysis for Resilience Evaluation in Water Distribution Networks. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2015, 14, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, A.; Crittenden, J.C. Index of Network Resilience for Urban Water Distribution Systems. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. 2016, 12, 120–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahmandfar, Z.; Piratla, K.R.; Andrus, R.D. Resilience Evaluation of Water Supply Networks against Seismic Hazards. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. Pract. 2017, 8, 04016014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahmandfar, Z.; Piratla, K.R. Comparative Evaluation of Topological and Flow-Based Seismic Resilience Metrics for Rehabilitation of Water Pipeline Systems. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. Pract. 2018, 9, 04017027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, A.; Otoo, R.A.; Jeffrey, P. Resilience Enhancing Expansion Strategies for Water Distribution Systems: A Network Theory Approach. Environ. Model. Softw. 2011, 26, 1574–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, Z.; Gong, H. Effects Comparison of Different Resilience Enhancing Strategies for Municipal Water Distribution Network: A Multidimensional Approach. Math. Probl. Eng. 2015, 2015, 438063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahmandfar, Z.; Piratla, K.R.; Andrus, R.D. Flow-Based Modeling for Enhancing Seismic Resilience of Water Supply Networks. In Proceedings of the Pipelines 2015, Baltimore, MD, USA, 23–26 August 2015; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2015; pp. 756–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Ma, D.; Hou, B.; Wang, W. Seismic Resilience Enhancement of Urban Water Distribution System Using Restoration Priority of Pipeline Damages. Sustainability 2020, 12, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, J.; Peiravi, A.; Anvari-Moghaddam, A. Enhancing Integrated Power and Water Distribution Networks Seismic Resilience Leveraging Microgrids. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nariman, A.; Fattahi, M.H.; Talebbeydokhti, N.; Sadeghian, M.S. Assessment of Seismic Resilience in Urban Water Distribution Network Considering Hydraulic Indices. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 2023, 47, 1165–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.; Huang, J.; Miao, H.; Zhao, X.; Wu, S. Seismic Resilience Evaluation of Water Distribution Systems Considering Hydraulic and Water Quality Performance. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 93, 103756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Li, H.; Sun, G. Seismic Resilience Assessment Method and Multi-Objective Optimal Recovery Strategy for Large-Scale Urban Water Distribution Network System. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 127, 105689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Community Resilience Planning Guide for Buildings and Infrastructure Systems: Volume I; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2015.

- Laucelli, D.; Giustolisi, O. Vulnerability Assessment of Water Distribution Networks under Seismic Actions. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2015, 141, 04014082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.; Rahman, M.; Mortula, M.; Atabay, S.; Ali, T. Water Distribution Network Resilience Management Using Global Resilience Analysis-Based Index. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueñas-Osorio, L.; Craig, J.I.; Goodno, B.J. Seismic Response of Critical Interdependent Networks. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2007, 36, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, M.; Ayala, G. Pipeline Damage Due to Wave Propagation. J. Geotech. Eng. 1993, 119, 1490–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agathokleous, A.; Christodoulou, C.; Christodoulou, S.E. Topological Robustness and Vulnerability Assessment of Water Distribution Networks. Water Resour. Manag. 2017, 31, 4007–4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Liu, W.; Shu, S. Resilience-Based Post-Earthquake Recovery Optimization of Water Distribution Networks. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 74, 102934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Pan, Z.; Yang, H.; Yang, Y.; Liu, F. A Multi-Objective Method for Enhancing the Seismic Resilience of Urban Water Distribution Networks. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighi, M.; Delnavaz, A.; Safehian, M.; Delnavaz, M. Strategic Management and Seismic Resilience Enhancement of Water Distribution Network Using Artificial Neural Network Model. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. Pract. 2025, 16, 04024053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchin, P.; Cavalieri, F. Probabilistic Assessment of Civil Infrastructure Resilience to Earthquakes. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2015, 30, 583–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, R.K.; Salman, A.M.; Li, Y.; Yu, X. Seismic Functionality and Resilience Analysis of Water Distribution Systems. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. Pract. 2020, 11, 04019045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Yuan, Y. Node Vulnerability of Water Distribution Networks under Cascading Failures. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2014, 124, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Song, Z.; Ouyang, M.; Li, J. Recovery-Based Seismic Resilience Enhancement Strategies of Water Distribution Networks. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 203, 107088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Yu, X. (Bill) Resilience of Water Distribution Network: Enhanced Recovery Assisted by Artificial Intelligence (AI) Considering Dynamic Water Demand Change. In Proceedings of the Lifelines 2022, Virtual Conference, 31 January–11 February 2022; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2022; pp. 880–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Song, Z.; Ji, H.; Wang, F. Predicting Water Pipe Failures with Graph Neural Networks: Integrating Coupled Road and Pipeline Features. Water 2025, 17, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Li, H.-N.; Li, C.; Tian, L. Parametric Study on Seismic Behaviors of a Buried Pipeline Subjected to Underground Spatially Correlated Earthquake Motions. J. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 26, 6329–6351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.; Qu, R.; Ke, Z.; Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Feng, Y. The Cloud Model Theory of Intelligent Control Method for Non-Minimum-Phase and Non-Self-Balancing System in Nuclear Power. In Proceedings of the 2018 26th International Conference on Nuclear Engineering, London, UK, 22–26 July 2018; ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2018; p. V001T04A013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Lv, X.; Zhang, H.; Meng, X.; Xu, Z.; Chen, C.; Liu, T. Cloud Model-Based Intelligent Controller for Load Frequency Control of Power Grid with Large-Scale Wind Power Integration. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1477645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Wang, G.; Zhang, X. A Novel Hybrid Water Quality Time Series Prediction Method Based on Cloud Model and Fuzzy Forecasting. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2015, 149, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Lin, Y.; Deng, H.; Li, J.; Liu, C. Prediction of Rock Burst Classification Using Cloud Model with Entropy Weight. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2016, 26, 1995–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, L.; Yang, C.; Li, Z. The Comprehensive Evaluation of Smart Distribution Grid Based on Cloud Model. Energy Procedia 2012, 17, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Xu, W.; Li, G.; Zhou, M. Cloud Model Based Power Quality Comprehensive Assessment Interactive Decision-Making Approach. In Proceedings of the 2014 China International Conference on Electricity Distribution (CICED), Shenzhen, China, 23–26 September 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1338–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Han, X.; Cao, B.; Li, B.; Yan, F. Cloud-Model-Based Method for Risk Assessment of Mountain Torrent Disasters. Water 2018, 10, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Huang, Q.; Ren, Y.; Sun, H.-B. Condition Assessment of Suspension Bridges Using Local Variable Weight and Normal Cloud Model. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22, 4064–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, A.-J.; Stoianov, I.; Chazerain, A. Hydraulically Informed Graph Theoretic Measure of Link Criticality for the Resilience Analysis of Water Distribution Networks. Appl. Netw. Sci. 2018, 3, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikholeslami, R.; Kaveh, A. Vulnerability Assessment of Water Distribution Networks: Graph Theory Method. Int. J. Optim. Civ. Eng. 2015, 5, 283–299. [Google Scholar]

- Pagano, A.; Giordano, R.; Portoghese, I. A Pipe Ranking Method for Water Distribution Network Resilience Assessment Based on Graph-Theory Metrics Aggregated through Bayesian Belief Networks. Water Resour. Manag. 2022, 36, 5091–5106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimellaro, G.P.; Tinebra, A.; Renschler, C.; Fragiadakis, M. New Resilience Index for Urban Water Distribution Networks. J. Struct. Eng. 2016, 142, C4015014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.; Ma, X.; Diao, K.; Zhong, Z.; Wu, S. Seismic Performance Assessment of Water Distribution Systems Based on Multi-Indexed Nodal Importance. Water 2021, 13, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, G.; Zhao, Y. A Framework for Identifying the Critical Region in Water Distribution Network for Reinforcement Strategy from Preparation Resilience. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudeau, R.J. Introduction to Graph Theory. In Dover Books on Advanced Mathematics; Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-0-486-67870-2. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, P. Seismic Response Modeling of Water Supply Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.; Ma, D.; Hou, B.; Wang, W. Post-Earthquake Hydraulic Analyses of Urban Water Supply Networkbased on Pressure Drive Demand Model. Sci. Sin. 2019, 49, 351–362. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, S.S.; O’Rourke, T.D. Northridge Earthquake Effects on Pipelines and Residential Buildings. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2005, 95, 294–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Seismic Performance Evaluation of Water Supply Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, J.M.; Shamir, U.; Marks, D.H. Water Distribution Reliability: Simulation Methods. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 1988, 114, 276–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D. Uncertainty in Knowledge Representation. Eng. Sci. 2000, 2, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mares, M. Fuzzy Sets. Scholarpedia 2006, 1, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. Foundations and Applications of the Probability Theories; Beijing Normal University Press: Beijing, China, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. Interval Cloud Model and Interval Cloud Generator. In Proceedings of the 2010 Second WRI Global Congress on Intelligent Systems, Wuhan, China, 16–17 December 2010; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, E.K.P.; Żak, S.H. An Introduction to Optimization, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-118-27901-4. [Google Scholar]

| Grade | Cloud Digital Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Poor | (0, 0.103, 0.0131) |

| Fair | (0.3029, 0.064, 0.0081) |

| Average | (0.500, 0.039, 0.005) |

| Good | (0.691, 0.064, 0.0081) |

| Excellent | (1, 0.103, 0.0131) |

| Node | QInit (L/s) | Elevation (m) | HInit (m) | Node | QInit (L/s) | Elevation (m) | HInit (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21.44 | 16.14 | 79.79 | 38 | 1.13 | 21.30 | 67.29 |

| 2 | 0.83 | 16.01 | 79.44 | 39 | 1.13 | 21.90 | 66.60 |

| 3 | 3.09 | 16.44 | 78.09 | 40 | 1.13 | 20.83 | 67.60 |

| 4 | 25.15 | 21.14 | 73.34 | 41 | 14.4 | 14.50 | 78.69 |

| 5 | 30.75 | 18.81 | 71.16 | 42 | 34.93 | 12.70 | 80.11 |

| 6 | 19.77 | 17.40 | 72.51 | 43 | 20.53 | 11.00 | 80.53 |

| 7 | 8.34 | 19.80 | 70.00 | 44 | 20.53 | 10.00 | 81.09 |

| 8 | 27.35 | 15.30 | 74.46 | 45 | 20.53 | 24.60 | 63.56 |

| 9 | 1.69 | 12.42 | 82.37 | 46 | 20.53 | 41.53 | 46.58 |

| 10 | 30.49 | 19.10 | 74.82 | 47 | 34.93 | 22.43 | 69.29 |

| 11 | 19.04 | 20.64 | 71.96 | 48 | 56.98 | 12.60 | 81.33 |

| 12 | 43.31 | 19.50 | 71.50 | 49 | 35.54 | 12.08 | 81.43 |

| 13 | 22.42 | 28.00 | 62.69 | 50 | 47.1 | 11.50 | 81.57 |

| 14 | 55.27 | 37.50 | 53.16 | 51 | 11.56 | 14.20 | 78.66 |

| 15 | 32.82 | 39.00 | 50.27 | 52 | 28.84 | 27.72 | 65.02 |

| 16 | 12.32 | 45.00 | 42.91 | 53 | 66.99 | 28.66 | 64.00 |

| 17 | 12.32 | 47.00 | 40.74 | 54 | 69.79 | 29.25 | 63.31 |

| 18 | 42.05 | 24.60 | 65.36 | 55 | 59.01 | 32.04 | 60.44 |

| 19 | 21.71 | 22.50 | 66.95 | 56 | 43.44 | 47.41 | 44.39 |

| 20 | 11.38 | 24.50 | 63.58 | 57 | 44.62 | 47.12 | 43.78 |

| 21 | 11.38 | 28.50 | 59.33 | 58 | 14.99 | 54.51 | 35.54 |

| 22 | 23.7 | 28.50 | 59.96 | 59 | 12.65 | 58.84 | 30.82 |

| 23 | 23.7 | 32.33 | 55.56 | 60 | 12.65 | 66.40 | 22.09 |

| 24 | 28.8 | 18.80 | 71.55 | 61 | 12.65 | 75.00 | 13.32 |

| 25 | 18.67 | 21.00 | 68.86 | 62 | 23.79 | 40.64 | 49.75 |

| 26 | 23.14 | 18.00 | 77.18 | 63 | 17.35 | 45.24 | 44.51 |

| 27 | 0 | 16.56 | 77.35 | 64 | 12.65 | 61.58 | 26.89 |

| 28 | 2.92 | 17.86 | 76.32 | 65 | 56.98 | 25.00 | 68.02 |

| 29 | 16.27 | 21.35 | 69.79 | 66 | 90.58 | 26.42 | 66.06 |

| 30 | 9.72 | 18.01 | 71.75 | 67 | 33.6 | 37.07 | 54.46 |

| 31 | 10.81 | 18.66 | 70.23 | 68 | 33.6 | 38.25 | 52.26 |

| 32 | 11.94 | 19.42 | 69.32 | 69 | 48.52 | 35.20 | 55.18 |

| 33 | 13.85 | 20.08 | 68.31 | 70 | 25.39 | 19.00 | 75.23 |

| 34 | 19.16 | 22.29 | 67.45 | 71 | 23.06 | 21.60 | 71.92 |

| 35 | 14.53 | 24.72 | 64.15 | 72 | 38.44 | 25.20 | 66.09 |

| 36 | 2.62 | 24.11 | 64.68 | 73 | 59.14 | 30.51 | 59.97 |

| 37 | 3.63 | 22.87 | 65.86 | 74 | 42.16 | 20.53 | 72.23 |

| Pipelines | Sarting Node | Termination Node | Lp (m) | Pipelines | Sarting Node | Termination Node | Lp (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 75 | 1 | 76.7 | 48 | 30 | 31 | 325.8 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 307.5 | 49 | 31 | 32 | 378.9 |

| 3 | 2 | 3 | 150.9 | 50 | 32 | 33 | 279.8 |

| 4 | 3 | 4 | 501.6 | 51 | 29 | 34 | 310 |

| 5 | 4 | 5 | 424.2 | 52 | 34 | 35 | 378.9 |

| 6 | 5 | 6 | 347.8 | 53 | 35 | 36 | 375 |

| 7 | 6 | 7 | 341.7 | 54 | 36 | 37 | 369.2 |

| 8 | 6 | 8 | 217.2 | 55 | 37 | 38 | 320 |

| 9 | 2 | 9 | 322.6 | 56 | 38 | 39 | 277.8 |

| 10 | 9 | 10 | 426.8 | 57 | 39 | 40 | 356.8 |

| 11 | 10 | 11 | 384.5 | 58 | 40 | 33 | 375.1 |

| 12 | 11 | 12 | 556.7 | 59 | 35 | 32 | 318.6 |

| 13 | 12 | 13 | 273.7 | 60 | 1 | 48 | 753.7 |

| 14 | 13 | 14 | 260.1 | 61 | 48 | 10 | 289.5 |

| 15 | 14 | 15 | 263.9 | 62 | 48 | 49 | 265.1 |

| 16 | 15 | 16 | 415.8 | 63 | 49 | 50 | 290.2 |

| 17 | 16 | 17 | 410.0 | 64 | 50 | 42 | 315.4 |

| 18 | 18 | 19 | 424.2 | 65 | 50 | 51 | 547.8 |

| 19 | 19 | 20 | 400.4 | 66 | 51 | 52 | 372.1 |

| 20 | 20 | 21 | 407.1 | 67 | 52 | 53 | 467.7 |

| 21 | 12 | 8 | 343.9 | 68 | 50 | 53 | 635 |

| 22 | 24 | 6 | 432.5 | 69 | 53 | 54 | 363.5 |

| 23 | 24 | 18 | 444.7 | 70 | 54 | 55 | 410.1 |

| 24 | 18 | 22 | 400.1 | 71 | 55 | 56 | 541.5 |

| 25 | 22 | 23 | 400.1 | 72 | 56 | 57 | 463.7 |

| 26 | 23 | 17 | 329.2 | 73 | 57 | 58 | 337.0 |

| 27 | 23 | 21 | 315.6 | 74 | 58 | 59 | 320.4 |

| 28 | 12 | 24 | 262.0 | 75 | 59 | 60 | 347.0 |

| 29 | 24 | 25 | 406.9 | 76 | 60 | 61 | 409.6 |

| 30 | 25 | 7 | 421.8 | 77 | 48 | 65 | 371.6 |

| 31 | 25 | 19 | 450.6 | 78 | 65 | 66 | 457.2 |

| 32 | 14 | 18 | 559.9 | 79 | 66 | 67 | 555.6 |

| 33 | 10 | 41 | 268.0 | 80 | 67 | 68 | 397.8 |

| 34 | 41 | 42 | 269.9 | 81 | 68 | 69 | 532.1 |

| 35 | 42 | 43 | 278.0 | 82 | 57 | 62 | 467.5 |

| 36 | 43 | 44 | 294.6 | 83 | 62 | 63 | 394.8 |

| 37 | 44 | 45 | 586.5 | 84 | 63 | 64 | 360.1 |

| 38 | 45 | 46 | 584.4 | 85 | 64 | 61 | 308.3 |

| 39 | 15 | 46 | 370.4 | 86 | 62 | 69 | 445.5 |

| 40 | 42 | 47 | 476.1 | 87 | 26 | 70 | 442.8 |

| 41 | 47 | 14 | 590.7 | 88 | 70 | 71 | 399.9 |

| 42 | 1 | 26 | 367.2 | 89 | 71 | 72 | 532.6 |

| 43 | 26 | 27 | 524.0 | 90 | 72 | 73 | 369.3 |

| 44 | 27 | 28 | 312.6 | 91 | 73 | 69 | 263.0 |

| 45 | 28 | 4 | 207.3 | 92 | 55 | 66 | 488.1 |

| 46 | 27 | 29 | 968.8 | 93 | 71 | 74 | 402.1 |

| 47 | 29 | 30 | 217.3 | 94 | 74 | 66 | 533.2 |

| Nodes | PGV (10 cm/s) | PGV (22 cm/s) | Nodes | PGV (10 cm/s) | PGV (22 cm/s) | Nodes | PGV (10 cm/s) | PGV (22 cm/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Excellent | Excellent | 26 | Good | Fair | 51 | Good | Fair |

| 2 | Excellent | Good | 27 | Excellent | Good | 52 | Good | Fair |

| 3 | Excellent | Good | 28 | Good | Fair | 53 | Good | Fair |

| 4 | Excellent | Average | 29 | Good | Fair | 54 | Good | Fair |

| 5 | Excellent | Fair | 30 | Good | Fair | 55 | Good | Fair |

| 6 | Good | Fair | 31 | Good | Fair | 56 | Good | Fair |

| 7 | Good | Fair | 32 | Good | Fair | 57 | Average | Fair |

| 8 | Good | Fair | 33 | Good | Fair | 58 | Average | Fair |

| 9 | Excellent | Good | 34 | Good | Fair | 59 | Average | Fair |

| 10 | Excellent | Average | 35 | Good | Fair | 60 | Average | Fair |

| 11 | Excellent | Average | 36 | Good | Fair | 61 | Average | Fair |

| 12 | Excellent | Fair | 37 | Good | Fair | 62 | Average | Fair |

| 13 | Good | Fair | 38 | Good | Fair | 63 | Average | Fair |

| 14 | Good | Fair | 39 | Good | Fair | 64 | Average | Fair |

| 15 | Good | Fair | 40 | Good | Fair | 65 | Average | Fair |

| 16 | Good | Fair | 41 | Good | Fair | 66 | Average | Fair |

| 17 | Good | Fair | 42 | Good | Fair | 67 | Average | Fair |

| 18 | Good | Fair | 43 | Good | Fair | 68 | Average | Fair |

| 19 | Good | Fair | 44 | Good | Fair | 69 | Average | Fair |

| 20 | Good | Fair | 45 | Good | Fair | 70 | Average | Fair |

| 21 | Good | Fair | 46 | Good | Fair | 71 | Average | Fair |

| 22 | Good | Fair | 47 | Good | Fair | 72 | Average | Fair |

| 23 | Good | Fair | 48 | Good | Fair | 73 | Average | Fair |

| 24 | Good | Fair | 49 | Good | Fair | 74 | Average | Fair |

| 25 | Good | Fair | 50 | Good | Fair | 75 | Excellent | Excellent |

| WSN | Good | Fair |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, P.; Zhang, J.; Li, K.; Tang, X.; Du, G. A Cloud Model-Based Framework for a Multi-Scale Seismic Robustness Evaluation of Water Supply Networks. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11081. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411081

Liu P, Zhang J, Li K, Tang X, Du G. A Cloud Model-Based Framework for a Multi-Scale Seismic Robustness Evaluation of Water Supply Networks. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11081. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411081

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Pingyuan, Juan Zhang, Keying Li, Xueliang Tang, and Guofeng Du. 2025. "A Cloud Model-Based Framework for a Multi-Scale Seismic Robustness Evaluation of Water Supply Networks" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11081. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411081

APA StyleLiu, P., Zhang, J., Li, K., Tang, X., & Du, G. (2025). A Cloud Model-Based Framework for a Multi-Scale Seismic Robustness Evaluation of Water Supply Networks. Sustainability, 17(24), 11081. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411081