Leveraging Explainable AI to Decode Energy Poverty in China: Implications for SDGs and National Policy

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Robust feature screening through Spearman correlation analysis enhances the model’s generalizability and computational efficiency;

- (2)

- The CNN architecture captures complex temporal patterns and deep features in household panel data, achieving predictive accuracy (average 98.23%) that surpasses traditional machine learning models;

- (3)

- The incorporation of SHAP interpretability decomposes model predictions into feature-specific contributions, thereby transparently revealing key drivers of energy poverty and their operational mechanisms.

- (1)

- Can a model combining high accuracy and strong interpretability be developed for identifying energy poverty using household-level microdata?

- (2)

- Which economic, demographic, and energy expenditure characteristics at the household level are key determinants of energy poverty?

- (3)

- Did these key factors undergo significant dynamic changes between 2014 and 2020, and are such changes consistent with national policy priorities?

- (1)

- Construct an explainable AI (XAI) framework integrating CNN and SHAP to accurately identify energy poor households in China;

- (2)

- Uncover key drivers of energy poverty through feature contribution analysis and quantify their influence mechanisms;

- (3)

- Analyze temporal trends in these drivers and explore their policy implications and links to the SDGs.

- (1)

- Household economic capacity (e.g., per capita expenditure) is the most critical determinant of energy poverty.

- (2)

- Household energy expenditure burden (e.g., share of electricity or gas costs) continues to exert a significant independent effect on energy poverty even after controlling for economic capacity.

- (3)

- Between 2014 and 2020, energy structure optimization and subsidy policies reduced the relative importance of energy burden-related indicators.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Description

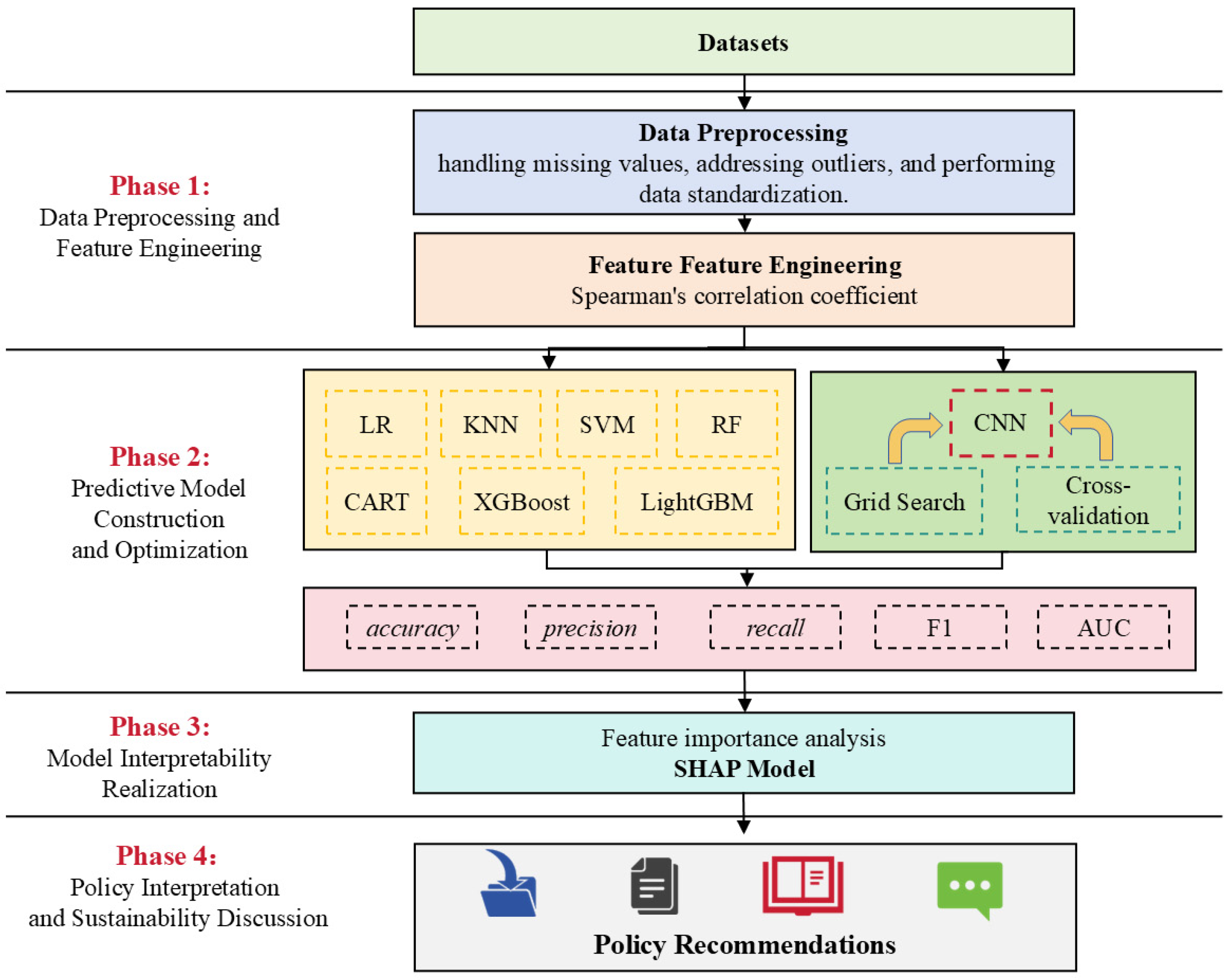

2.2. Research Framework/Theoretical Model

2.3. Methodology

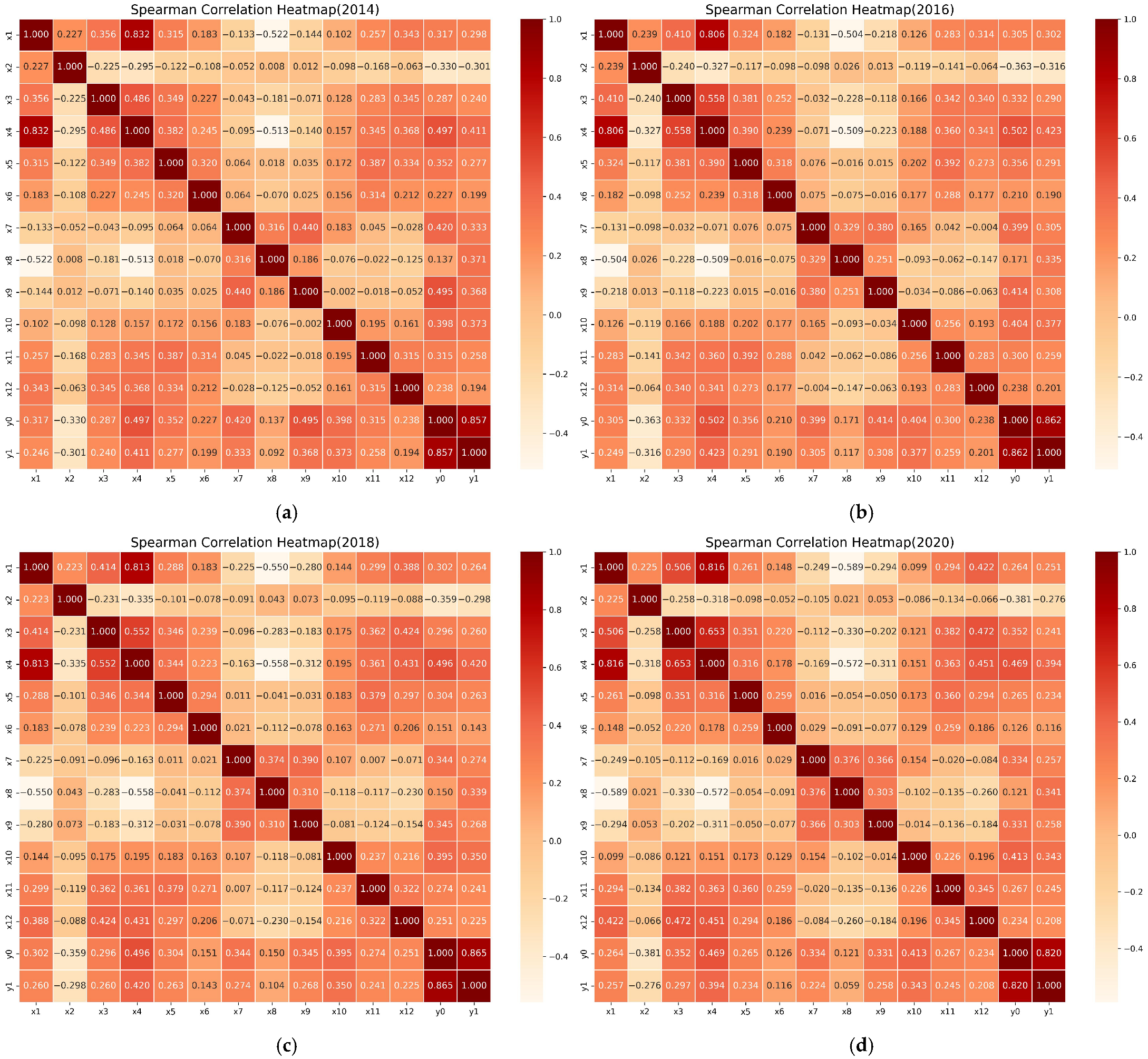

2.3.1. Feature Selection Method

2.3.2. Predictive Model (CNN)

2.3.3. Interpretability Method (SHAP)

2.3.4. Rationale for Model Selection

2.3.5. Benchmark Models

- (1)

- Logistic Regression (LR): A linear baseline model. It is included to establish a simple, interpretable benchmark and to highlight the potential non-linearity in the data if more complex models perform significantly better.

- (2)

- k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN): An instance-based learning algorithm. It is sensitive to the local structure of the data and serves as a non-parametric benchmark.

- (3)

- Support Vector Machine (SVM): A powerful classifier effective in high-dimensional spaces. We used a linear kernel for simplicity and computational efficiency, representing a maximum-margin classifier.

- (4)

- Random Forest (RF): A robust bagging ensemble of decision trees. It is known for its high accuracy and resistance to overfitting, making it a strong benchmark for structured data.

- (5)

- Classification and Regression Tree (CART): A single decision tree model. It provides a simple, interpretable benchmark against which the ensemble and deep learning models can be compared.

- (6)

- eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost): A highly efficient and effective gradient boosting framework. It is often a top performer in tabular data competitions and represents the state-of-the-art in tree-based ensembles.

- (7)

- Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM): Another high-performance gradient boosting framework, optimized for speed and memory efficiency. Its inclusion allows for a comparison with XGBoost to assess the impact of different boosting implementations.

2.4. Experimental Setup and Evaluation Metrics

- (1)

- The energy poverty indicator itself is a relatively stable and clearly defined binary classification;

- (2)

- The seven features retained after Spearman correlation screening exhibit strong discriminative power for identifying poverty;

- (3)

- The CNN is capable of capturing interactions among features.

3. Results

3.1. Feature Selection Results

3.2. Model Predictive Performance

3.3. Interpretability Analysis Results

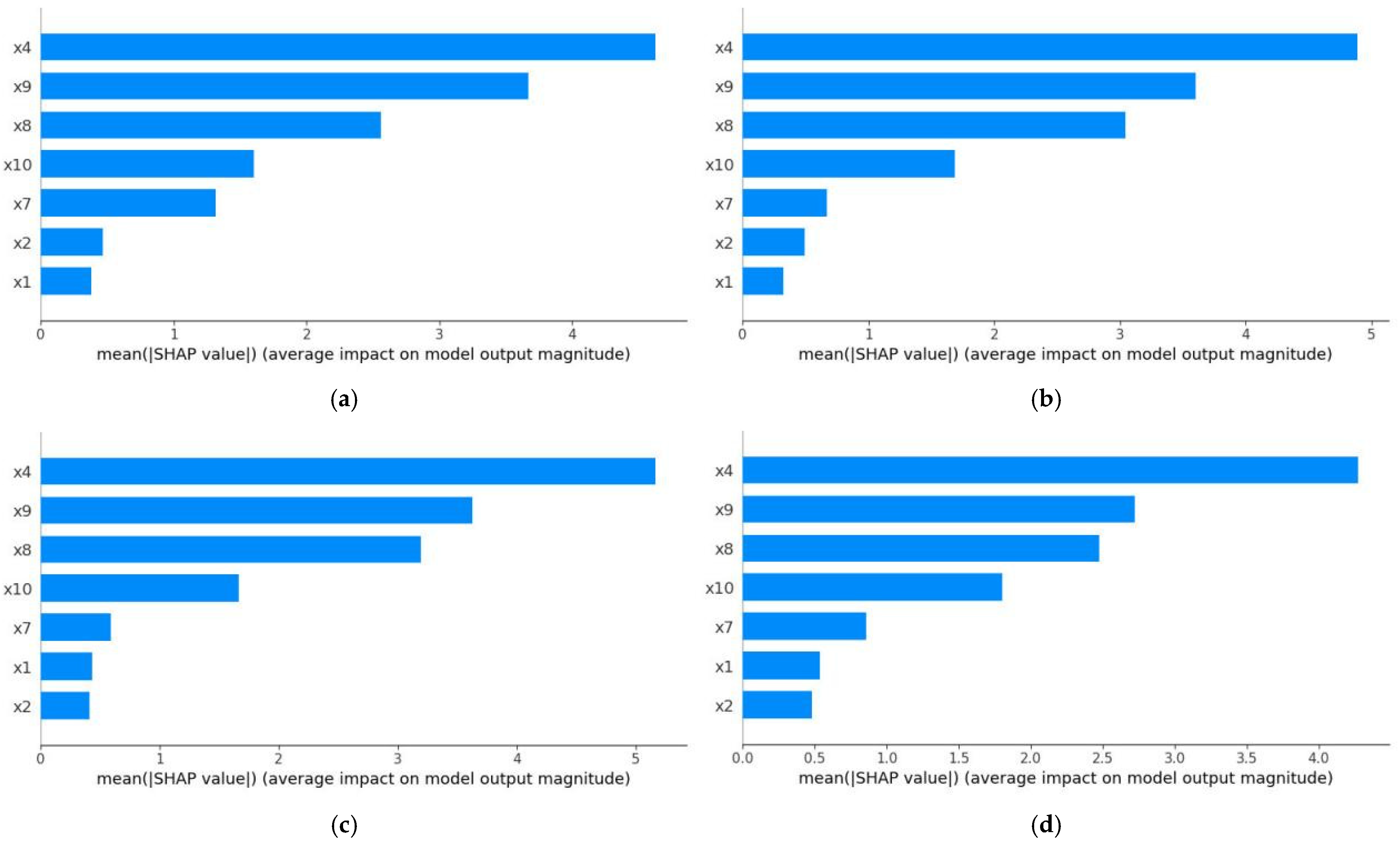

3.3.1. Global Feature Importance

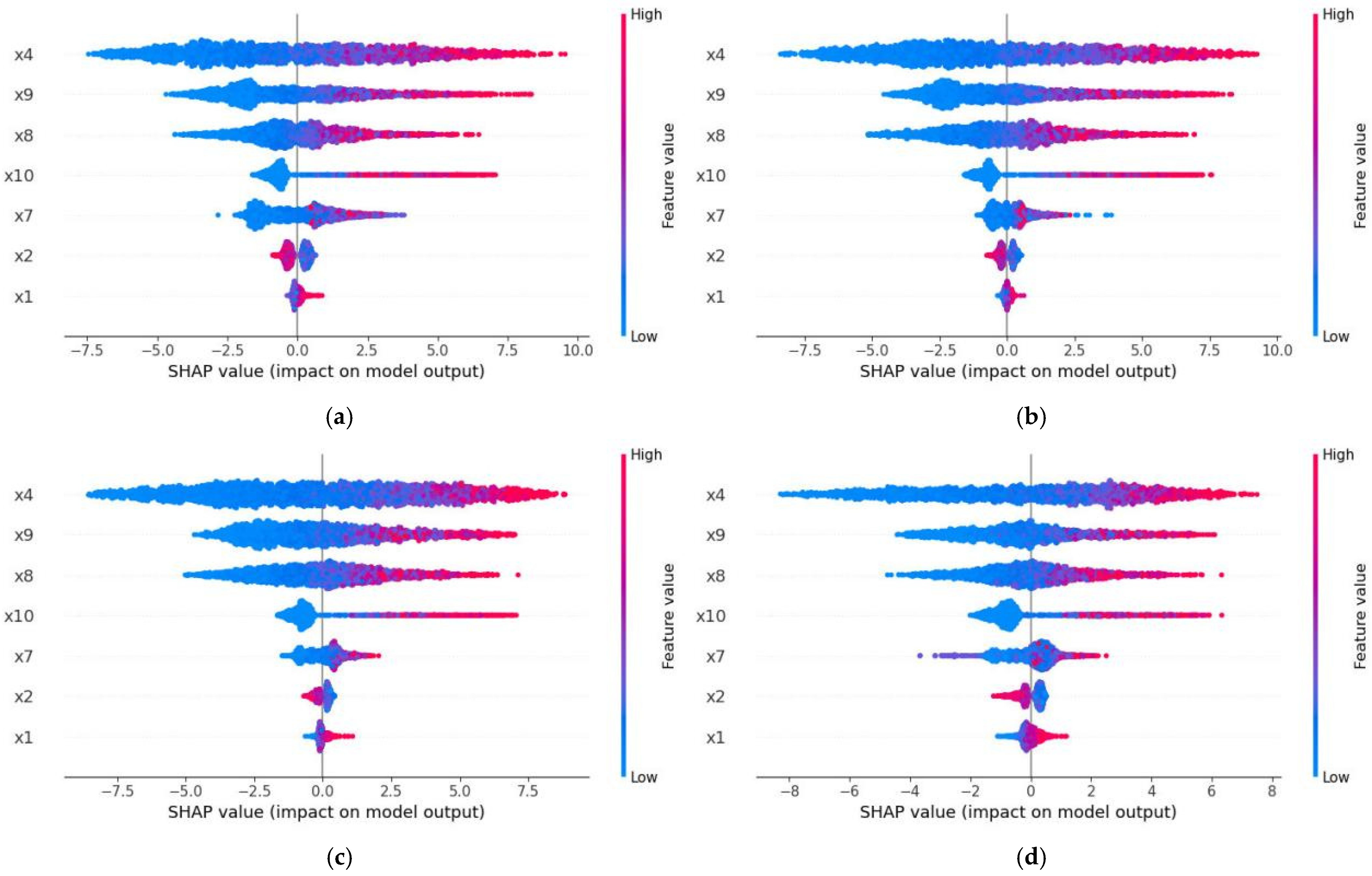

3.3.2. Feature Effect Direction and Mechanisms

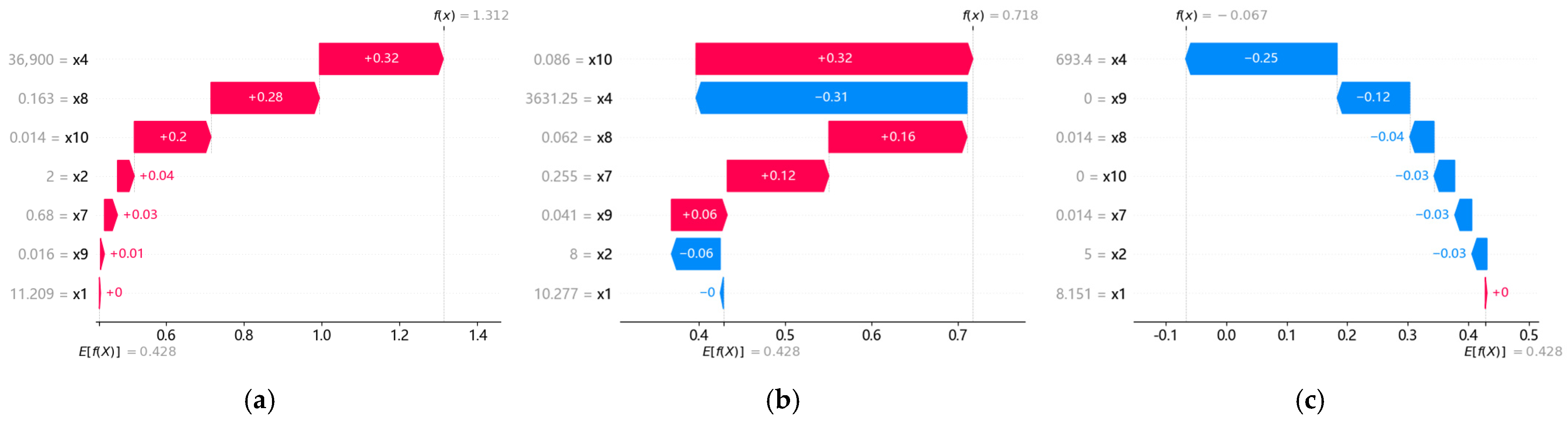

3.3.3. Local Interpretation: Representative Case Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Core Drivers of Energy Poverty: The Dual Interplay of Economic Capacity and Energy Burden

4.2. Dynamic Evolution and Policy Effectiveness: A Positive Signal

4.3. Policy Implications: From Universal Support to Targeted Intervention

4.4. Potential Implications of Other Features

4.5. Implications for Sustainable Development Goals

4.6. Consideration of Regional Heterogeneity

4.7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

- (1)

- The model achieved high accuracy across all years, indicating that a framework combining deep learning with interpretability techniques exhibits robustness and practical potential in energy poverty identification;

- (2)

- Household expenditure per capita consistently emerged as the most critical determinant, highlighting the foundational role of economic capacity in household energy well-being;

- (3)

- Energy burden indicators (such as the share of electricity and gas expenditures) continued to exhibit independent and significant poverty-inducing effects even after controlling for economic capacity, indicating that the energy pricing system and household energy structure remain important risk sources;

- (4)

- The importance of gas expenditure showed a declining trend over time, aligning with China’s recent clean heating initiatives, expansion of gas infrastructure, and diversified subsidy policies, reflecting the positive impact of policy interventions in improving household energy access.

- (1)

- Enhance targeted energy subsidies for low-income households, with particular focus on groups facing high energy expenditure burdens, to alleviate structural risks of energy poverty;

- (2)

- Promote the adoption of distributed energy resources and high-efficiency appliances to reduce household energy expenditure pressure by improving energy efficiency and optimizing energy structure;

- (3)

- Implement regionally differentiated energy governance strategies, developing tailored policy solutions according to the specific needs of urban and rural areas, as well as northern heating zones and southern regions;

- (4)

- Establish long-term monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to continuously track trends in household energy poverty indicators, linking them with SDG 7.1 (universal access to modern energy services) and SDG 1.1 (eradicating extreme poverty) to provide data support for achieving sustainable energy transition.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| KNN | k-Nearest Neighbor |

| SVM | Support Vector Machines |

| RF | Random Forest |

| CART | Classification and Regression Tree |

| XGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

| LightGBM | Light Gradient Boosting Machine |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| EPPE-FCS | Energy Poverty Prediction and Explanation Framework with CNN and SHAP |

| CFPS | China Family Panel Studies |

Appendix A

References

- Lee, B.X.; Kjaerulf, F.; Turner, S.; Cohen, L.; Donnelly, P.D.; Muggah, R.; Davis, R.; Realini, A.; Kieselbach, B.; MacGregor, L.S.; et al. Transforming Our World: Implementing the 2030 Agenda Through Sustainable Development Goal Indicators. J Public Health Policy 2016, 37, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanojia, S.; Kapoor, N.; Chhabra, M.; Sethi, P. Regional Disparities and International Spillover in Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) across the Globe. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, E.; Madaleno, M.; Inglesi-Lotz, R.; Taskin, D. Race and Energy Poverty: Evidence from African-American Households. Energy Econ. 2022, 108, 105908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalfountzou, E.; Papada, L.; Tourkolias, C.; Mirasgedis, S.; Kaliampakos, D.; Damigos, D. A Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Algorithms in Energy Poverty Prediction. Energies 2025, 18, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gao, M.; Luo, E.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X. Does Rural Energy Poverty Alleviation Really Reduce Agricultural Carbon Emissions? The Case of China. Energy Econ. 2023, 119, 106576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, P.; Li, Q.; Sousa-Poza, A. Energy Poverty and Subjective Well-Being in China: New Evidence from the China Family Panel Studies. Energy Econ. 2021, 103, 105548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, M.; Raimondi, P.P. Priorities and Challenges of the EU Energy Transition: From the European Green Package to the New Green Deal. Russ. J. Econ. 2020, 6, 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sy, S.A.; Mokaddem, L. Energy Poverty in Developing Countries: A Review of the Concept and Its Measurements. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 89, 102562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Dong, K.; Dong, X.; Shahbaz, M. How Renewable Energy Alleviate Energy Poverty? A Global Analysis. Renew. Energy 2022, 186, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Chen, S.; Weng, Z. Digital Technology Alleviates Intergenerational Energy Poverty: Evidence from Household Analysis. Appl. Energy 2025, 399, 126488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papada, L.; Kaliampakos, D. Measuring Energy Poverty in Greece. Energy Policy 2016, 94, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betto, F.; Garengo, P.; Lorenzoni, A. A New Measure of Italian Hidden Energy Poverty. Energy Policy 2020, 138, 111237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siksnelyte-Butkiene, I. A Systematic Literature Review of Indices for Energy Poverty Assessment: A Household Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Yu, L.; Xue, B.; Chen, X.; Mi, Z. Who Is Energy Poor? Evidence from the Least Developed Regions in China. Energy Policy 2020, 137, 111122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boardman, B. Fuel Poverty Synthesis: Lessons Learnt, Actions Needed: Fuel Poverty Comes of Age: Commemorating 21 Years of Research and Policy. Energy Policy 2012, 49, 143–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, J. Fuel Poverty: The Problem and Its Measurement; Department for Energy and Climate Change: London, UK, 2011.

- Nussbaumer, P.; Bazilian, M.; Modi, V. Measuring Energy Poverty: Focusing on What Matters. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.F.; Khandker, S.R.; Samad, H.A. Energy Poverty in Rural Bangladesh. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 894–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chien, F.; Hsu, C.-C.; Zhang, Y.; Nawaz, M.A.; Iqbal, S.; Mohsin, M. Nexus between Energy Poverty and Energy Efficiency: Estimating the Long-Run Dynamics. Resour. Policy 2021, 72, 102063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lan, Y.; Deng, M.; Zhang, Y. Accurate Identification of Energy Poverty in China: An Analysis Based on an Equivalent Scale. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2023, 40, 136–157. [Google Scholar]

- Arribas-Bel, D.; Patino, J.E.; Duque, J.C. Remote Sensing-Based Measurement of Living Environment Deprivation: Improving Classical Approaches with Machine Learning. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Zhan, Z.; Jin, L.; Huang, F.; Xu, H. Research on Method of Identifying Poor Families Based on Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 4th Advanced Information Management, Communicates, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IMCEC), Chongqing, China, 18–20 June 2021; Volume 4, pp. 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Liu, Y.; Hu, P.; Ding, S.; Gao, S.; Zhang, M. What Influence Farmers’ Relative Poverty in China: A Global Analysis Based on Statistical and Interpretable Machine Learning Methods. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Kez, D.; Foley, A.; Khald Abdul, Z.; Furszyfer Del Rio, D. Machine Learning-Based Approach for Predicting Energy Poverty in the United Kingdom Incorporating Remote-Sensing and Socioeconomic Data; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawusu, S.; Jamatutu, S.A.; Ahmed, A. Predictive Modeling of Energy Poverty with Machine Learning Ensembles: Strategic Insights from Socioeconomic Determinants for Effective Policy Implementation. Int. J. Energy Res. 2024, 2024, 9411326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.K.; Islam, M.; Hasan, M.M.; Razia, S.; Hassan, M.; Khushbu, S.A. Sentiment Analysis in Multilingual Context: Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning and Hybrid Deep Learning Models. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, V.; Khajuria, A.; Pachauri, R.K.; Gupta, V. Optimized Machine Learning Based Comparative Analysis of Predictive Models for Classification of Kidney Tumors. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makumbura, R.K.; Mampitiya, L.; Rathnayake, N.; Meddage, D.P.P.; Henna, S.; Dang, T.L.; Hoshino, Y.; Rathnayake, U. Advancing Water Quality Assessment and Prediction Using Machine Learning Models, Coupled with Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) Techniques like Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) for Interpreting the Black-Box Nature. Results Eng. 2024, 23, 102831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, B.; Srikanya, K.; Varshini, M.; Srijanya, S.; Reddy, G.; Shirisha, C. The Application of Machine Learning to the Task of Poverty Classification. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication and Applied Informatics (ACCAI), Chennai, India, 25–26 May 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machlev, R.; Heistrene, L.; Perl, M.; Levy, K.Y.; Belikov, J.; Mannor, S.; Levron, Y. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) Techniques for Energy and Power Systems: Review, Challenges and Opportunities. Energy AI 2022, 9, 100169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/sjzx/gksj/index.htm (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Al Kez, D.; Foley, A.; Lowans, C.; Del Rio, D.F. Energy Poverty Assessment: Indicators and Implications for Developing and Developed Countries. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 307, 118324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Xu, X. A Review of Rural Household Energy Poverty: Identification, Causes and Governance. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersha, M.A.; Yigezu, M.G.; Tonja, A.L.; Shakil, H.; Iskander, S.; Kolesnikova, O.; Kalita, J. Explainable AI: XAI-Guided Context-Aware Data Augmentation. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 289, 128364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Lei, T.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y. Using Explainable Artificial Intelligence to Identify Key Characteristics of Deep Poverty for Each Household. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Luo, X.; Deng, C.; Shu, K.; Zhu, W.; Griss, J.; Hermjakob, H.; Bai, M.; Perez-Riverol, Y. Deep Learning Embedder Method and Tool for Mass Spectra Similarity Search. J. Proteom. 2021, 232, 104070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amarkhil, Q.; Elwakil, E.; Hubbard, B. A Meta-Analysis of Critical Causes of Project Delay Using Spearman’s Rank and Relative Importance Index Integrated Approach. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2021, 48, 1498–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, Q.; Chen, Y.; Dai, B.; Li, D.; Fan, L. Prediction of Slope Safety Factor Based on Attention Mechanism-Enhanced CNN-GRU. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Cui, B.; Xu, L.; Wang, J.; Guo, Z. Coupling LSTM and CNN Neural Networks for Accurate Carbon Emission Prediction in 30 Chinese Provinces. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, R.S.; Longo, L. Explaining Deep Q-Learning Experience Replay with SHapley Additive exPlanations. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2023, 5, 1433–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppalapati, S.; Paramasivam, P.; Kilari, N.; Chohan, J.S.; Kanti, P.K.; Vemanaboina, H.; Dabelo, L.H.; Gupta, R. Precision Biochar Yield Forecasting Employing Random Forest and XGBoost with Taylor Diagram Visualization. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Zhang, X. A New Interpretable Streamflow Prediction Approach Based on SWAT-BiLSTM and SHAP. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 23896–23908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Yan, J.; Shan, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Hang, Y.; Li, R.; Liu, Y.; Liu, B.; Nie, Q.; Bruckner, B.; et al. Burden of the Global Energy Price Crisis on Households. Nat. Energy 2023, 8, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Gatto, A.; Sharifi, A.; Salvia, A.L.; Guevara, Z.; Awoniyi, S.; Mang-Benza, C.; Nwedu, C.N.; Surroop, D.; Teddy, K.O.; et al. Energy Poverty in African Countries: An Assessment of Trends and Policies. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 117, 103664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoch, O.R.; Sharma, R.; Parihar, S.; Nawaz, A. Energy Poverty and Its Impacts on Health and Education: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2023, 18, 411–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Symbol | Variable Description | Mean | Std. Dev. | Max | Min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | x1 | Log expenditure | 10.50 | 0.95 | 15.45 | 5.30 |

| x2 | Household size (persons) | 3.73 | 1.83 | 17.00 | 1.00 | |

| x3 | Annual net income per capita (yuan) | 14,420.96 | 19,829.06 | 980,000.00 | 0.25 | |

| x4 | Annual expenditure per capita (yuan) | 18,171.11 | 38,820.33 | 2,562,500.00 | 100.00 | |

| x5 | Modern fuel usage (1 = Yes, 0 = No) | 0.63 | 0.48 | 1.00 | 0.00 | |

| x6 | Piped utility access (1 = With, 0 = Without) | 0.69 | 0.46 | 1.00 | 0.00 | |

| x7 | Housing expenditure share (%) | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.98 | 0.00 | |

| x8 | Electricity expenditure share (%) | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.84 | 0.00 | |

| x9 | Gas expenditure share (%) | 0.03 | 0.58 | 0.90 | 0.00 | |

| x10 | Heating expenditure share (%) | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.80 | 0.00 | |

| x11 | Urban-rural (1 = Urban, 0 = Rural) | 0.49 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.00 | |

| x12 | Education level (0 = Illiterate/Semi-literate, 1 = Primary, 2 = Junior high, 3 = Senior high, 4 = College+) | 1.74 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | |

| 2016 | x1 | Log expenditure | 10.75 | 0.94 | 15.46 | 4.65 |

| x2 | Household size (persons) | 3.67 | 1.88 | 19.00 | 1.00 | |

| x3 | Annual net income per capita (yuan) | 17,466.76 | 30,417.94 | 1,806,000.00 | 0.45 | |

| x4 | Annual expenditure per capita (yuan) | 23,708.83 | 37,770.12 | 1,292,305.00 | 52.00 | |

| x5 | Modern fuel usage (1 = Yes, 0 = No) | 0.68 | 0.46 | 1.00 | 0.00 | |

| x6 | Piped utility access (1 = With, 0 = Without) | 0.75 | 0.44 | 1.00 | 0.00 | |

| x7 | Housing expenditure share (%) | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.98 | 0.00 | |

| x8 | Electricity expenditure share (%) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.57 | 0.00 | |

| x9 | Gas expenditure share (%) | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.86 | 0.00 | |

| x10 | Heating expenditure share (%) | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.60 | 0.00 | |

| x11 | Urban-rural (1 = Urban, 0 = Rural) | 0.50 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.00 | |

| x12 | Education level (0 = Illiterate/Semi-literate, 1 = Primary, 2 = Junior high, 3 = Senior high, 4 = College+) | 1.77 | 1.01 | 4.00 | 0.00 | |

| 2018 | x1 | Log expenditure | 10.78 | 0.96 | 14.52 | 4.80 |

| x2 | Household size (persons) | 3.57 | 1.91 | 21.00 | 1.00 | |

| x3 | Annual net income per capita (yuan) | 22,348.76 | 30,750.96 | 1,012,500.00 | 0.00 | |

| x4 | Annual expenditure per capita (yuan) | 25,462.83 | 35,298.46 | 1,614,900.00 | 120.00 | |

| x5 | Modern fuel usage (1 = Yes, 0 = No) | 0.74 | 0.44 | 1.00 | 0.00 | |

| x6 | Piped utility access (1 = With, 0 = Without) | 0.77 | 0.42 | 1.00 | 0.00 | |

| x7 | Housing expenditure share (%) | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.96 | 0.00 | |

| x8 | Electricity expenditure share (%) | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.96 | 0.00 | |

| x9 | Gas expenditure share (%) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.65 | 0.00 | |

| x10 | Heating expenditure share (%) | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.49 | 0.00 | |

| x11 | Urban-rural (1 = Urban, 0 = Rural) | 0.51 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.00 | |

| x12 | Education level (0 = Illiterate/Semi-literate, 1 = Primary, 2 = Junior high, 3 = Senior high, 4 = College+) | 1.95 | 1.03 | 4.00 | 1.00 | |

| 2020 | x1 | Log expenditure | 10.87 | 0.98 | 15.20 | 5.71 |

| x2 | Household size (persons) | 3.62 | 1.93 | 15.00 | 1.00 | |

| x3 | Annual net income per capita (yuan) | 32,606.21 | 51,798.04 | 2,011,200.00 | 0.00 | |

| x4 | Annual expenditure per capita (yuan) | 27,940.50 | 38,004.03 | 801,352.00 | 200.00 | |

| x5 | Modern fuel usage (1 = Yes, 0 = No) | 0.79 | 0.41 | 1.00 | 0.00 | |

| x6 | Piped utility access (1 = With, 0 = Without) | 0.83 | 0.38 | 1.00 | 0.00 | |

| x7 | Housing expenditure share (%) | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.95 | 0.00 | |

| x8 | Electricity expenditure share (%) | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.72 | 0.00 | |

| x9 | Gas expenditure share (%) | 0.03 | 0.48 | 0.72 | 0.00 | |

| x10 | Heating expenditure share (%) | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.00 | |

| x11 | Urban-rural (1 = Urban, 0 = Rural) | 0.53 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.00 | |

| x12 | Education level (0 = Illiterate/Semi-literate, 1 = Primary, 2 = Junior high, 3 = Senior high, 4 = College+) | 2.14 | 1.07 | 4.00 | 1.00 |

| Year | Model | Accuracy | Precision | F1 Score | Recall | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | LR | 73.28% | 72.78% | 63.09% | 66.36% | 81.05% |

| KNN | 88.86% | 91.27% | 82.30% | 86.19% | 95.34% | |

| SVM | 82.57% | 81.75% | 78.64% | 79.30% | 92.10% | |

| RF | 95.44% | 94.70% | 94.80% | 94.68% | 99.49% | |

| CART | 93.74% | 92.66% | 92.78% | 92.68% | 93.61% | |

| XGBoost | 97.69% | 97.23% | 97.36% | 97.29% | 99.81% | |

| LightGBM | 97.43% | 96.81% | 97.18% | 96.99% | 99.78% | |

| Gradient Boosting | 95.83% | 95.26% | 94.92% | 95.09% | 99.27% | |

| EPPE-FCS | 98.95% | 99.64% | 97.90% | 98.75% | 98.81% | |

| 2016 | LR | 77.51% | 78.37% | 71.62% | 74.07% | 85.98% |

| KNN | 84.12% | 83.53% | 82.01% | 82.40% | 92.19% | |

| SVM | 82.52% | 82.77% | 79.24% | 80.38% | 91.20% | |

| RF | 95.75% | 95.25% | 95.54% | 95.33% | 99.49% | |

| CART | 94.21% | 93.70% | 93.63% | 93.61% | 94.16% | |

| XGBoost | 97.73% | 97.34% | 97.63% | 97.48% | 99.81% | |

| LightGBM | 97.71% | 97.42% | 97.51% | 97.46% | 99.82% | |

| Gradient Boosting | 96.31% | 95.99% | 95.83% | 95.91% | 99.45% | |

| EPPE-FCS | 98.15% | 99.99% | 98.71% | 96.73% | 96.85% | |

| 2018 | LR | 77.19% | 77.86% | 80.42% | 78.71% | 84.94% |

| KNN | 89.44% | 91.14% | 88.91% | 89.86% | 96.19% | |

| SVM | 86.50% | 84.84% | 91.42% | 87.78% | 95.05% | |

| RF | 95.34% | 95.13% | 96.25% | 95.64% | 99.39% | |

| CART | 93.49% | 93.77% | 93.99% | 93.84% | 93.46% | |

| XGBoost | 97.83% | 97.79% | 98.11% | 97.95% | 99.83% | |

| LightGBM | 97.74% | 97.75% | 97.98% | 97.86% | 99.82% | |

| Gradient Boosting | 96.18% | 95.92% | 96.88% | 96.40% | 99.50% | |

| EPPE-FCS | 97.86% | 99.59% | 96.36% | 97.94% | 97.95% | |

| 2020 | LR | 72.42% | 72.57% | 82.63% | 77.26% | 77.59% |

| KNN | 83.78% | 85.92% | 85.42% | 85.66% | 90.99% | |

| SVM | 77.99% | 75.91% | 89.68% | 82.21% | 85.89% | |

| RF | 95.07% | 94.67% | 96.77% | 95.71% | 99.13% | |

| CART | 92.60% | 93.92% | 92.99% | 93.44% | 92.67% | |

| XGBoost | 96.98% | 96.80% | 97.91% | 97.35% | 99.67% | |

| LightGBM | 96.90% | 96.87% | 97.70% | 97.28% | 99.68% | |

| Gradient Boosting | 94.53% | 93.73% | 96.82% | 95.25% | 98.86% | |

| EPPE-FCS | 97.94% | 98.77% | 98.13% | 96.44% | 95.75% |

| Feature | Description | Mean SHAP Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2016 | 2018 | 2020 | ||

| x4 | Annual household expenditure per capita (in yuan) | 0.2173 | 0.2313 | 0.2332 | 0.2158 |

| x9 | Share of gas expenditure (%) | 0.1399 | 0.1345 | 0.1294 | 0.1159 |

| x8 | Share of electricity expenditure (%) | 0.0972 | 0.1187 | 0.1155 | 0.1047 |

| x10 | Share of heating expenditure (%) | 0.0956 | 0.0991 | 0.0943 | 0.1027 |

| x7 | Share of housing expenditure (%) | 0.0515 | 0.0352 | 0.0429 | 0.0475 |

| x2 | Household size (number of persons) | 0.0342 | 0.0331 | 0.0272 | 0.0331 |

| x1 | Logarithm of total expenditure | 0.0083 | 0.0107 | 0.0172 | 0.0231 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qi, H.; Xue, Q.; Shi, Y.; Qi, X.; Yang, J.; Zheng, J.; Ren, L. Leveraging Explainable AI to Decode Energy Poverty in China: Implications for SDGs and National Policy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11080. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411080

Qi H, Xue Q, Shi Y, Qi X, Yang J, Zheng J, Ren L. Leveraging Explainable AI to Decode Energy Poverty in China: Implications for SDGs and National Policy. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11080. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411080

Chicago/Turabian StyleQi, Hui, Qiang Xue, Ying Shi, Xiaobo Qi, Jing Yang, Jingjing Zheng, and Lifang Ren. 2025. "Leveraging Explainable AI to Decode Energy Poverty in China: Implications for SDGs and National Policy" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11080. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411080

APA StyleQi, H., Xue, Q., Shi, Y., Qi, X., Yang, J., Zheng, J., & Ren, L. (2025). Leveraging Explainable AI to Decode Energy Poverty in China: Implications for SDGs and National Policy. Sustainability, 17(24), 11080. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411080