Pasture Restoration Reduces Runoff and Soil Loss in Karst Landscapes of the Brazilian Cerrado

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

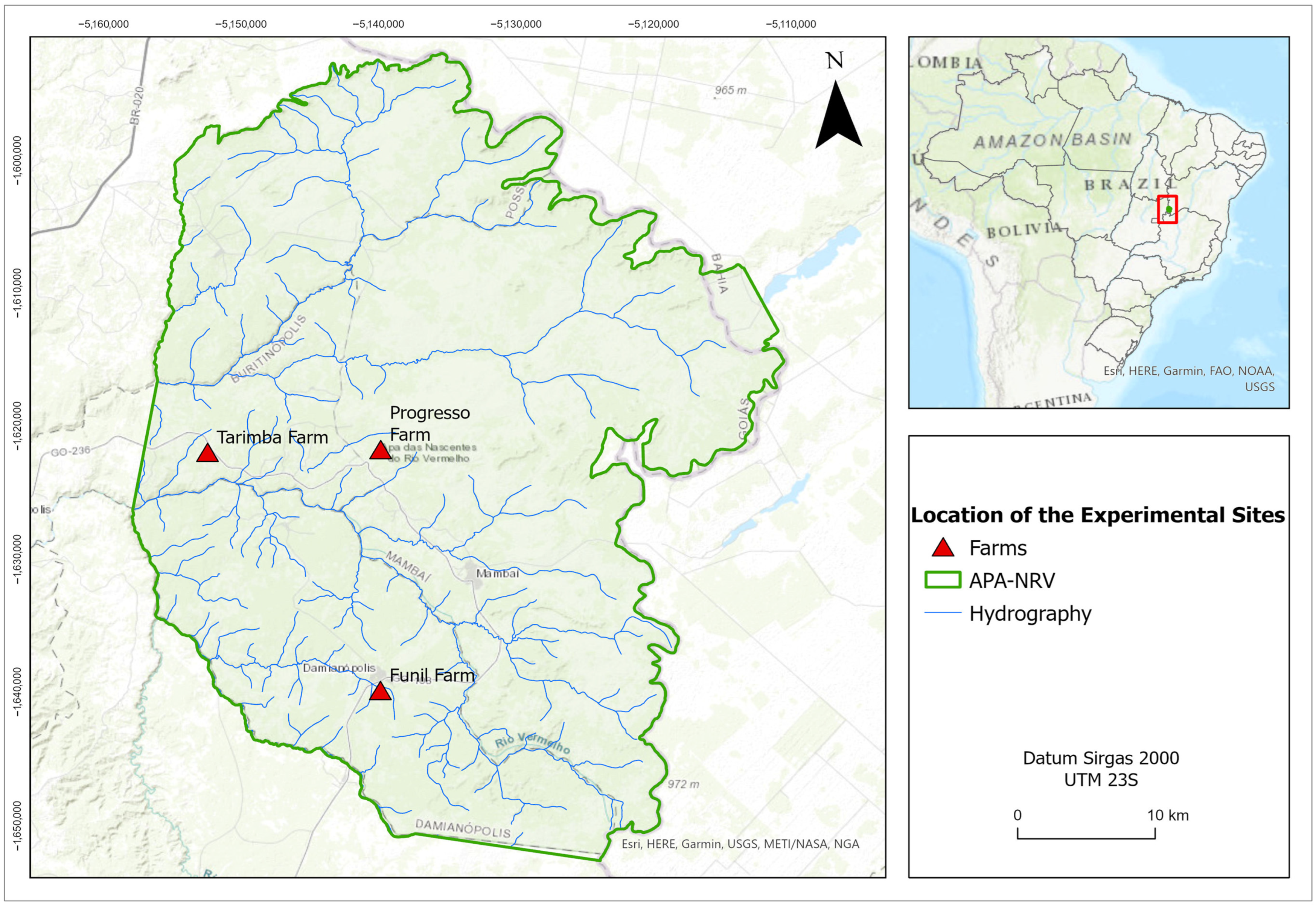

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Runoff Plots

2.3. Rainfall Erosivity

2.4. Runoff Sampling and Laboratory Analyses

2.5. Runoff Volume and Soil Loss

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Precipitation and Erosivity

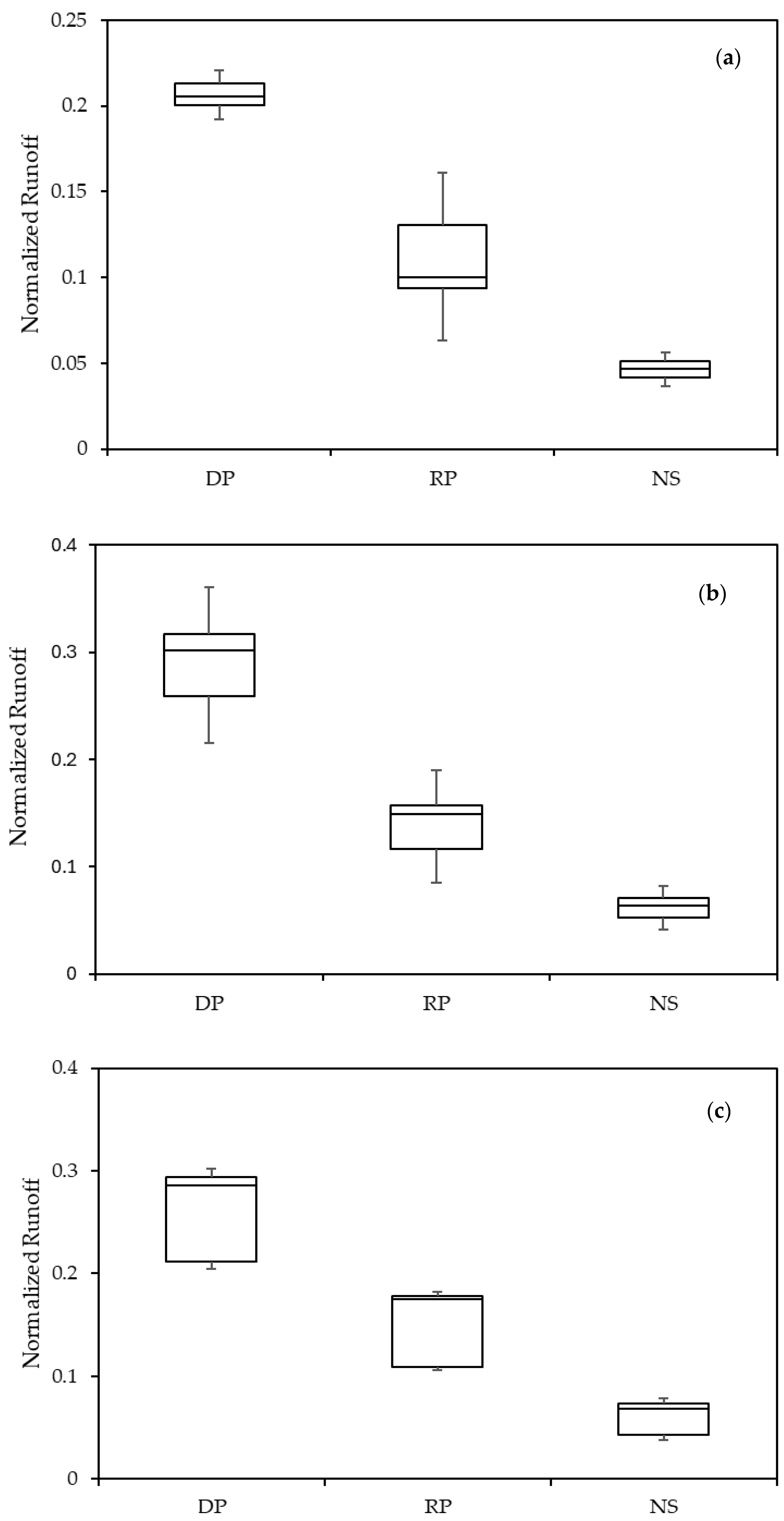

3.2. Runoff

3.3. Soil Loss

3.4. Relationship Between Runoff and Soil Loss and On- and Off-Site Tolerance

4. Discussion

4.1. Precipitation and Rainfall Erosivity

4.2. Runoff

4.3. Soil Loss

4.4. Practical Implications of the Study

4.5. Methodological Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DP | Degraded Pasture |

| RP | Restored Pasture |

| NS | Natural Savannah |

References

- Zhou, J.; Fu, B.; Gao, G.; Lü, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lü, N.; Wang, S. Effects of Precipitation and Restoration Vegetation on Soil Erosion in a Semi-Arid Environment in the Loess Plateau, China. Catena 2016, 137, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullan, D. Soil Erosion under the Impacts of Future Climate Change: Assessing the Statistical Significance of Future Changes and the Potential on-Site and off-Site Problems. Catena 2013, 109, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, M.R.S.; Uagoda, R.; Chaves, H.M.L. Runoff, Soil Loss, and Water Balance in a Restored Karst Area of the Brazilian Savanna. Catena 2023, 222, 106878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewski, P.; Märker, M. The Role of Soil-Protecting Forests in Reducing Soil Erosion in Young Glacial Landscapes of Northern-Central Poland. Geoderma 2019, 337, 1227–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewski, P.; Märker, M. Comparison of Topsoil Organic Carbon Stocks on Slopes under Soil-Protecting Forests in Relation to the Adjacent Agricultural Slopes. Forests 2021, 12, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majoro, F.; Wali, U.G.; Munyaneza, O.; Naramabuye, F.-X.; Mukamwambali, C. On-Site and Off-Site Effects of Soil Erosion: Causal Analysis and Remedial Measures in Agricultural Land—A Review. Rwanda J. Eng. Sci. Technol. Environ. 2020, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boardman, J.; Vandaele, K.; Evans, R.; Foster, I.D.L. Off-Site Impacts of Soil Erosion and Runoff: Why Connectivity Is More Important than Erosion Rates. Soil Use Manag. 2019, 35, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, D.C.; Nearing, M.A. Sediment Particle Sorting on Hillslope Profiles in the Wepp Model. Trans. ASAE 2000, 43, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, Y. Phosphorus Adsorption and Desorption Behavior on Sediments of Different Origins. J. Soils Sediments 2010, 10, 1159–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, P.H.; Kinnell, P.I.A.; Green, P. Transport of a Noncohesive Sandy Mixture in Rainfall and Runoff Experiments. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1978, 42, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Li, Z.; He, J.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, B.; Ma, W.; Lu, Y.; Zeng, G. Enrichment of Organic Carbon in Sediment under Field Simulated Rainfall Experiments. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 74, 5417–5425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacha, K.M.; Papanicolaou, A.N.T.; Abban, B.K.; Wilson, C.G.; Giannopoulos, C.P.; Hou, T.; Filley, T.R.; Hatfield, J.L. The Impact of Tillage Row Orientation on Physical and Chemical Sediment Enrichment. Agrosystems Geosci. Environ. 2020, 3, e20007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabelo, L.M.; Souza-Silva, M.; Ferreira, R.L. Priority Caves for Biodiversity Conservation in a Key Karst Area of Brazil: Comparing the Applicability of Cave Conservation Indices; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 27, ISBN 1053101815546. [Google Scholar]

- Cadamuro, A.L. Relatório dos Estudos das Atividades Antrópicas Potencialmente Contaminantes do Sistema Cárstico e Pontos de Pressão no Ambiente Espeleológico na Região da Área da Bacia do São Francisco; Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis: Brasília, Brazil, 2006.

- Anache, J.A.A.; Flanagan, D.C.; Srivastava, A.; Wendland, E.C. Land Use and Climate Change Impacts on Runoff and Soil Erosion at the Hillslope Scale in the Brazilian Cerrado. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 622–623, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, P.T.S.; Wendland, E.; Nearing, M.A. Rainfall Erosivity in Brazil: A Review. Catena 2013, 100, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checchia, T. Avaliação de Perda de Solo por Erosão Hídrica e Estudo de Emergia na Bacia do Rio Caeté, Alfredo Wagner-Santa Catarina; UFSC: Florianópolis, Brazil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, M.R.S.; Uagoda, R.; Chaves, H.M.L. Rates, Factors, and Tolerances of Water Erosion in the Cerrado Biome (Brazil): A Meta-Analysis of Runoff Plot Data. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms 2021, 47, 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, M.G.B.; Pilon, N.A.L.; Ribeiro, M.C.; Durigan, G. Abandoned Pastures Cannot Spontaneously Recover the Attributes of Old-Growth Savannas. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 55, 1164–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P.T.S.; Nearing, M.A.; Wendland, E. Orders of Magnitude Increase in Soil Erosion Associated with Land Use Change from Native to Cultivated Vegetation in a Brazilian Savannah Environment. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms 2015, 40, 1524–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagnini, F. Management for Sustainability and Restoration of Degraded Pastures in the Neotropics. In Post-Agricultural Succession in the Neotropics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 265–295. [Google Scholar]

- Galdino, S.; Sano, E.E.; Andrade, R.G.; Grego, C.R.; Nogueira, S.F.; Bragantini, C.; Flosi, A.H.G. Large-Scale Modeling of Soil Erosion with RUSLE for Conservationist Planning of Degraded Cultivated Brazilian Pastures. Land Degrad. Dev. 2016, 27, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buisson, E.; Le Stradic, S.; Silveira, F.A.O.; Durigan, G.; Overbeck, G.E.; Fidelis, A.; Fernandes, G.W.; Bond, W.J.; Hermann, J.M.; Mahy, G.; et al. Resilience and Restoration of Tropical and Subtropical Grasslands, Savannas, and Grassy Woodlands. Biol. Rev. 2019, 94, 590–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, H.M.L.; Concha Lozada, C.M.; Gaspar, R.O. Soil Quality Index of an Oxisol under Different Land Uses in the Brazilian Savannah. Geoderma Reg. 2017, 10, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, S.P.; Fonte, S.J.; García, E.; Smukler, S.M. Improving the Utility of Erosion Pins: Absolute Value of Pin Height Change as an Indicator of Relative Erosion. Catena 2018, 163, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.P.C. Soil Erosion and Conservation; Longman: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach, T. Hillslope Troughs for Measuring Sediment Movement. Rev. Geomorphol. Dyn. 1967, 17, 173. [Google Scholar]

- Mastura, S.A.S.; Toum, S. A Study on Surface Wash and Runoff Using Open System Erosion Plots. Trop. Agric. Sci. 2000, 23, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, B.; Montgomery, D. Design of Experiments: A Modern Approach; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Júnior, M.C.; Sarmento, T.R. Comunidades Lenhosas No Cerrado Sentido Restrito Em Duas Posições Topográficas Na Estação Ecológica Do Jardim Botânico de Brasília, DF, Brasil. Rodriguésia 2009, 60, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A.M. Rainfall Erosivity Map for Brazil. Catena 2004, 57, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.C. Design and Analysis of Experiments; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- NRCS. Chapter 9-Hydrologic Soil-Cover Complexes. In Part 630 Hydrology National Engineering Handbook; NRCS: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Las Heras, J.; Merino-Martin, L.; Wilcox, B.P. Plot-Scale Effects on Runoff and Erosion along a Slope Degradation Gradient. WRR 2009, 46, W04503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez, J.J.; Puricelli, M.; Unzu, F.L.; Francés, F. Parameter Extrapolation to Ungauged Basins with a Hydrological Distributed Model in a Regional Framework. Hydrol. Earth Sys. Sci 2009, 13, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nearing, M.A.; Foster, G.R.; Lane, L.J.; Finkner, S.C.F. A Process-Based Soil Erosion Model for USDA-Water Erosion Prediction Project Technology. Am. Soc. Agric. Biol. Eng. 1989, 32, 1587–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.F.; Dunkerley, D.; López-Vicente, M.; Shi, Z.H.; Wu, G.L. Trade-off between Surface Runoff and Soil Erosion during the Implementation of Ecological Restoration Programs in Semiarid Regions: A Meta-Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 712, 136477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilding, L.P.; Drees, L.R. Spatial Variability and Pedology. In Developments in Soil Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1982; pp. 83–116. [Google Scholar]

- Klik, A.; Rosner, J. Long-Term Experience with Conservation Tillage Practices in Austria: Impacts on Soil Erosion Processes. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 203, 104669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Site | Topography (Slope Grade) | Soil Type | Land Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Funil farm | Gentle (9.3%) | Red Orthox (sandy loam) | Pasture and savannah |

| Progresso farm | Gentle (6.8%) | Psamment (sand) | Pasture and savannah |

| Tarimba farm | Moderate (11.5%) | Orthent (silt loam) | Pasture and savannah |

| Experimental Site | Penetration Resistance, 0–10 cm (MPa) | Infiltration Rate (cm min−1) |

|---|---|---|

| Funil farm | 3.33 | 0.28 |

| Progresso farm | 0.78 | 0.91 |

| Tarimba farm | 1.95 | 0.80 |

| Site | Degraded Pasture | Restored Pasture | Natural Savannah | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | a | b | a | b | |

| --------------------------------- (m2) ----------------------------------------------- | ||||||

| Funil farm | 17.0 | 20.7 | 18.4 | 21.2 | 21.0 | 19.0 |

| Progresso farm | 12.7 | 22.3 | 15.1 | 21.6 | 20.0 | 22.0 |

| Tarimba farm | 28.5 | 22.7 | 20.9 | 20.8 | 20.0 | 16.0 |

| Month/Year | Funil Farm | Progresso Farm | Tarimba Farm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P (mm) | R (MJ mm ha−1 h−1) | P (mm) | R (MJ mm ha−1 h−1) | P (mm) | R (MJ mm ha−1 h−1) | |

| Aug/22 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Sep/22 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Oct/22 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Nov/22 | 252.7 | 155.9 | 150.0 | 84.2 | 242.2 | 116.8 |

| Dec/22 | 264.0 | 164.3 | 295.5 | 190.6 | 214.5 | 100.8 |

| Jan/23 | 176.2 | 100.9 | 166.5 | 95.4 | 225.7 | 107.2 |

| Feb/23 | 27.7 | 10.9 | 34.5 | 14.3 | 406.4 | 218.0 |

| Mar/23 | 108.7 | 56.4 | 105.0 | 54.7 | 126.7 | 53.5 |

| Apr/23 | 155.1 | 86.5 | 212.2 | 127.9 | 244.5 | 118.1 |

| May/23 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Jun/23 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Jul/23 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 984.5 | 7236.5 | 963.61 | 7140.9 | 1460.0 | 8994.0 |

| Aug/23 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 19.3 | 77.1 |

| Sep/23 | 12.6 | 4.1 | 49.7 | 19.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Oct/23 | 29.2 | 11.5 | 27.5 | 9.6 | 98.4 | 43.6 |

| Nov/23 | 98.3 | 49.5 | 84.6 | 37.1 | 69.7 | 28.8 |

| Dec/23 | 188.5 | 108.5 | 125.2 | 59.6 | 152.2 | 73.9 |

| Jan/24 | 170.6 | 96.2 | 228.5 | 123.0 | 183.9 | 92.8 |

| Feb/24 | 255.3 | 156.4 | 303.7 | 173.3 | 333.8 | 190.5 |

| Mar/24 | 136.3 | 73.3 | 165.2 | 83.2 | 173.5 | 86.5 |

| Apr/24 | 108.2 | 55.6 | 208.0 | 109.8 | 199.4 | 102.3 |

| May/24 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Jun/24 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Jul/24 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 999.0 | 6988.5 | 1192.5 | 7743.1 | 1231.9 | 7871.4 |

| Aug/24 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Sep/24 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Oct/24 | 283.6 | 161.0 | 156.1 | 99.3 | 261.6 | 124.1 |

| Nov/24 | 231.0 | 125.7 | 276.6 | 132.2 | 293.1 | 142.3 |

| Dec/24 | 167.8 | 85.5 | 481.1 | 257.6 | 271.5 | 129.8 |

| Jan/25 | 204.8 | 108.7 | 206.3 | 92.8 | 286.5 | 138.5 |

| Feb/25 | 105.2 | 48.7 | 122.6 | 49.5 | 129.7 | 53.2 |

| Mar/25 | 56.8 | 23.2 | 181.4 | 79.4 | 164.5 | 70.9 |

| Apr/25 | 125.7 | 60.3 | 126.4 | 51.4 | 105.9 | 41.7 |

| May/25 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Jun/25 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 27.1 | 8.1 |

| Jul/25 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 1174.9 | 7719.6 | 1550.5 | 9181.7 | 1540.0 | 8920.8 |

| Site | Treatment | Normalized Runoff |

|---|---|---|

| Funil farm | DP | 0.207 a |

| RP | 0.116 b | |

| NS | 0.046 c | |

| Progresso farm | DP | 0.283 a |

| RP | 0.133 b | |

| NS | 0.061 b | |

| Tarimba farm | DP | 0.242 a |

| RP | 0.134 ab | |

| NS | 0.055 b |

| Site | Treatment | Normalized Soil Loss (Mg hr−1 MJ mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Funil farm | DP | 0.0060 a |

| RP | 0.0020 b | |

| NS | 0.0005 b | |

| Progresso farm | DP | 6.05 × 10−4 a |

| RP | 2.80 × 10−4 ab | |

| NS | 6.61 × 10−4 b | |

| Tarimba farm | DP | 0.0070 a |

| RP | 0.0010 b | |

| NS | 0.0004 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Camargo, I.F.L.G.; Chaves, H.M.L.; Fonseca, M.R.S. Pasture Restoration Reduces Runoff and Soil Loss in Karst Landscapes of the Brazilian Cerrado. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11079. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411079

Camargo IFLG, Chaves HML, Fonseca MRS. Pasture Restoration Reduces Runoff and Soil Loss in Karst Landscapes of the Brazilian Cerrado. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11079. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411079

Chicago/Turabian StyleCamargo, Isabela Fernanda L. G., Henrique Marinho Leite Chaves, and Maria Rita Souza Fonseca. 2025. "Pasture Restoration Reduces Runoff and Soil Loss in Karst Landscapes of the Brazilian Cerrado" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11079. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411079

APA StyleCamargo, I. F. L. G., Chaves, H. M. L., & Fonseca, M. R. S. (2025). Pasture Restoration Reduces Runoff and Soil Loss in Karst Landscapes of the Brazilian Cerrado. Sustainability, 17(24), 11079. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411079