2. Methods

2.1. Study Area

As China’s economic and cultural center—as well as a leading global metropolis—Shanghai has developed a multilayered spatial structure and a distinctive historical character throughout its modern urbanization process. The historic districts embedded within the city’s urban fabric not only document the social life and architectural forms of various historical periods but also bear witness to Shanghai’s transformation from a traditional port city into an international metropolis [

11]. These areas serve not only as carriers of tangible heritage, but also as vital sources of collective memory and local identity for residents.

However, in the context of rapid urbanization and spatial restructuring, Shanghai’s historic districts face multiple challenges. Some areas are experiencing infrastructure deterioration, demographic shifts, and a weakening sense of cultural identity—factors that contribute to the gradual erosion of the social functions and symbolic significance of traditional spaces. Balancing the preservation of historical patterns with the demands of contemporary urban development has thus become a central issue in urban governance and design practice.

Based on archival research and field investigations, this study selected six historic districts within Shanghai’s inner ring—each retaining characteristic historical features—as the research objects (

Figure 1). These districts exhibit significant differences in spatial morphology, architectural style, and functional composition, encompassing both high-density commercial zones and residential or culture-oriented living areas (

Appendix A). By conducting cross-sectional comparisons of built-environment characteristics and perceptual differences across these various district types, the study aims to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the spatial expressions and perceptual mechanisms of historic districts in the context of a modern metropolis.

2.2. Analytical Framework

This study establishes an integrated analytical framework that combines spatial data, street-view imagery, and subjective perception evaluations to identify the mechanisms through which built-environment elements influence perceptual differences in historic districts (

Figure 2). The framework follows a three-tier logic: space, visual, and perception. First, the study delineates spatial boundaries and collects objective environmental data; second, visual features are extracted from street-view images using deep learning models; and finally, subjective perceptual responses are quantified through questionnaire-based evaluations. This approach enables correlation analysis between objective environmental characteristics and subjective perception outcomes.

First, the boundaries of the six selected historic districts in Shanghai were determined using data from the China Historical Architecture Conservation Network (

http://www.aibaohu.com/). Subsequently, the street network for each district was extracted from OpenStreetMap (

www.openstreetmap.org), and a grid of sampling points was generated in ArcGIS Pro 3.4 at 50-m intervals to ensure spatial uniformity and representativeness. Based on these sampling points, the Baidu Map API (

https://lbsyun.baidu.com/) was employed to collect information on POIs and corresponding street-view images within the study area, thereby constructing the foundational dataset for analysis.

Second, the street-view images were processed using the PSPNet semantic segmentation model to identify and quantify 150 categories of micro-environmental elements. These elements include buildings, vegetation, roads, advertisements, vehicles, pedestrians, and others. The proportion of pixels corresponding to each category was used to describe the visual composition of the streetscape, serving as input variables for subsequent perception modeling.

To obtain the public’s subjective perceptions of the district environment, an online anonymous questionnaire survey was designed and administered. Participants were required to be at least eighteen years old and to evaluate the environment in the street-view images across seven perceptual dimensions. Commonly used perceptual dimensions include safety, liveliness, beauty, wealthiness, depression, and boredom [

10]. The historic districts examined in this study are high-density everyday urban spaces with strong residential and local functions. In such contexts, cleanliness and orderliness have been repeatedly identified in environmental psychology and urban governance research as important determinants of comfort, safety, and place image [

34]. Therefore, this study includes cleanliness as one of the indicators to more accurately reflect the structure of environmental experience within the local context (

Table 1).

All questions were measured using a five-point Likert scale, and the survey design and implementation were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Shanghai for Science and Technology. A total of eight hundred and thirty-five valid responses were collected, and when combined with two hundred ninety-six thousand six hundred fifty-seven POI records and three thousand three hundred seventy-one street-view images, a comprehensive database integrating multiple sources of information was established.

Finally, the study employed the XGBoost model, using micro-environmental elements and POI features as independent variables and perceptual ratings as dependent variables, to identify the importance and direction (positive or negative) of various built-environment characteristics across different perceptual dimensions. This framework enabled systematic modeling of the relationship between objective environmental attributes and subjective perception outcomes, providing an operational pathway for quantifying environmental experience and informing design optimization strategies in historic districts.

2.3. Dependent Variable

To evaluate pedestrians’ subjective perceptions of different district environments, an anonymous online questionnaire survey was conducted from 19 May to 18 August 2025. Participants were invited to rate the presented street-view images across seven perceptual dimensions: beautiful, boring, depressing, lively, safe, wealthy, and clean. The questionnaire adopted an open-ended rating mechanism, allowing participants to evaluate only the dimensions they found relevant, rather than responding to all items sequentially. This design aimed to encourage respondents to answer based on their genuine impressions, thereby enhancing the authenticity and psychological validity of the perceptual responses.

Building on previous research, the Likert scale records subjective intensity in an ordinal format, allowing respondents to express both the direction and magnitude of their evaluations. It is particularly well-suited for quantifying continuous subjective experiences such as emotions and aesthetic judgments. The five-level progression from low to high enables participants to form stable judgments within a short time, thereby reducing cognitive load and improving response consistency. The Likert scale has been widely applied in studies of environmental perception, walking experience, and urban imagery, demonstrating strong comparability and interpretability. Accordingly, this study adopts the Likert scale and subsequently tests the reliability and validity of the scale items. For robustness analysis, ordinal-variable treatment approaches are also considered to minimize measurement error and enhance the stability of the results.

The questionnaire was distributed through a custom-developed program created by the research team. The system randomly selected images from the database and assigned them to each participant, generating a unique anonymous ID for every session. Each image set was linked to the corresponding ID and locked prior to submission to ensure that no image was reused, thereby preventing rating bias. Each participant was required to evaluate five street-view images. This number was determined based on pilot testing, which considered participants’ attention thresholds and response burden. The results indicated that when the number of images exceeded five, both completion rates and rating quality declined significantly, whereas five images effectively balanced data volume with participant focus and response reliability.

The survey followed the principles of voluntary and anonymous participation and complied with ethical review requirements. After excluding invalid, duplicate, or incomplete responses, a total of eight hundred and thirty-five valid questionnaires were retained. Most participants were university students and faculty members from the Shanghai region, many of whom had lived or studied in the city for an extended period and were therefore familiar with the everyday environments and spatial characteristics of local historic districts. This sample composition reflects a relatively high level of education and strong environmental sensitivity, providing a robust basis for the analysis of urban visual perception and environmental experience in this study.

2.4. Independent Variable: Environmental Features

2.4.1. Baidu Street View Image Environmental Features

Street-view imagery, with its high visual information density and ability to represent spatial structure, has become an important data source for studying the relationships between urban physical environments and spatial perception [

35].

In this study, SVIs were obtained in batches from the Baidu Map Open Platform based on the geographic coordinates of the sampling points. To more accurately simulate the human eye–level perspective and observation height, parameters such as azimuth angle, pitch angle, and viewpoint height were specified to ensure consistency and representativeness of the image views. A total of 3371 street-view images were ultimately collected for analysis.

Subsequently, pixel-level semantic segmentation was performed on the street-view images using the PSPNet model in combination with the ADE20K dataset, identifying and extracting approximately 150 feature categories (

Figure 3), including micro-environmental elements such as sky, roads, and pedestrians. The PSPNet model is an advanced deep convolutional neural network that incorporates a pyramid pooling module to effectively integrate global and local features, thereby enhancing overall scene interpretation. Through an optimized loss function design, the model achieves state-of-the-art segmentation performance, demonstrating high efficiency and accuracy in street-view image processing tasks [

36,

37].

2.4.2. POI Data

POIs are a core concept in geographic information systems, encompassing extensive information on public infrastructure and commercial facilities. They are characterized by large data volume, broad spatial coverage, high identification accuracy, and convenient accessibility [

38]. In recent years, with the continuous advancement of China’s digital urbanization, urban spatial entities have increasingly been abstracted into “points of interest” and visualized for users through mapping applications. POI data not only reflect the spatial distribution and attribute characteristics of urban functional facilities, but are also closely associated with human perceptions of urban space. As a result, they have been widely applied in studies of urban perception and human behavior [

7].

In this study, POI data within the research area were extracted using the Baidu Map API (

https://lbsyun.baidu.com/), obtaining information such as name, address, and geographic coordinates. After data cleaning, coordinate transformation, and sorting procedures, a total of 296,657 POI records were collected. Based on the official classification system, the POIs were categorized into eight major types (

Table 2): food, shopping, life services, travel sights, leisure and entertainment, institutional and business services, transportation services, and accommodation services.

2.5. Data Processing and Analysis

2.5.1. Reliability and Validity Testing of the Questionnaire

To ensure the validity of the questionnaire, both reliability and validity tests were conducted. For the reliability assessment, Cronbach’s α coefficient was used to evaluate the internal consistency of each set of variables. This coefficient is a widely used metric for assessing the consistency of interval or quasi-interval scale ratings and has been broadly applied in scale reliability evaluations [

39,

40]. A higher α value indicates stronger measurement reliability; generally, a coefficient above 0.6 is considered acceptable, while values above 0.7 indicate good internal consistency. This study adhered to these standards to ensure that the variable structures demonstrated high reliability [

41].

To further assess the structural suitability of the variable sets, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were conducted as part of the validity analysis. Together, these tests provided a preliminary basis for evaluating the structural validity of the questionnaire.

2.5.2. Analyzing the Influence Mechanisms Between Subjective Perception and Environmental Variables Based on the XGBoost Model

To explore the contribution and underlying mechanisms of built-environment variables across different perceptual dimensions, the XGBoost machine learning model was employed for analysis. XGBoost is a gradient boosting–based ensemble learning method that iteratively optimizes a set of weak learners, making it well-suited for research scenarios involving numerous variables, complex feature types, and nonlinear relationships. Its structure effectively captures interaction effects and nonlinear responses among high-dimensional features, and it has demonstrated strong predictive performance and stability in studies of urban spatial analysis, behavioral science, and environmental perception [

42,

43,

44]. Therefore, compared with other models, XGBoost demonstrates superior performance in analyzing complex nonlinear relationships that are essential for environmental research [

45].

However, for complex models such as XGBoost, the original model structure cannot be directly interpreted. Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) can overcome this limitation [

46]. Therefore, this study employed the SHAP method to enhance model transparency and result credibility. Originating from Shapley value theory, this approach quantifies the marginal contribution of each variable to the model’s prediction and identifies both the direction—indicating whether the variable promotes or suppresses perceptual ratings—and the relative importance of each factor [

47,

48].

Subsequently, the outputs of the XGBoost model were used to evaluate the predictive effects of built-environment variables across different perceptual dimensions, while SHAP analysis was employed to identify key variables and their directions of influence. To further reveal the nonlinear structures of these features, Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) were used to illustrate the average marginal effects of environmental variables on model outputs across different value ranges. PDPs visualize the marginal effects of individual features on the outputs of machine learning models and are particularly suitable for exploring non-monotonic relationships within high-dimensional and multifaceted data structures [

49]. This method isolates the target feature by holding other variables constant, enabling the observation of how variations in that feature influence perceptual ratings, thereby revealing potential threshold effects, saturation points, or nonlinear patterns [

50,

51]. SHAP and PDPs can be used to quantify feature importance and to visualize domain-specific outcomes, which supports the identification of the most effective interventions [

52]. This process facilitates an understanding of the sensitive intervals and critical turning points of specific environmental factors from the perspectives of urban design and spatial governance, providing empirical evidence for informed policy recommendations and design strategies.

3. Results

3.1. Questionnaire Validation Results

Before conducting the model analysis, a reliability test was performed on the questionnaire data. The model inputs consisted of two categories of variables: the first included eight POI indicators, and the second comprised eleven micro-level visual elements derived from street-view imagery. In total, these 19 variables were used to construct the built-environment feature matrix.

First, by examining the values of Cronbach’s α coefficients, the results (

Table 3) show that the POI variables achieved an α value of 0.789, exceeding the commonly accepted threshold of 0.7 and indicating stable internal consistency among these variables. The α value for the micro-level visual elements was 0.632—slightly below the 0.7 benchmark but still within an acceptable range. When all 19 variables were combined, the overall α coefficient reached 0.729, suggesting that the overall variable structure demonstrated good internal reliability.

It is important to note that environmental feature variables differ substantially from conventional psychological scales. Elements such as vegetation, building façades, public facilities, and open-space components in urban environments exhibit high heterogeneity in both type and spatial distribution; therefore, a level of internal consistency comparable to that of attitudinal scales should not be expected. Previous studies have pointed out that the diversity and complexity of urban environmental features often lead to relatively lower internal consistency, which in fact reflects the genuine heterogeneity of spatial landscapes rather than deficiencies in scale quality. Accordingly, this study considers the obtained reliability results to be both reasonable and valid, providing a stable data foundation for subsequent model analyses.

Secondly, as shown in

Table 4, the KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.753, exceeding the commonly accepted threshold of 0.7 and indicating strong inter-variable cohesion and suitability for factor analysis. In addition, Bartlett’s test of sphericity yielded a significant result (χ

2 = 8821.612, df = 171,

p < 0.001), suggesting good overall validity. These findings demonstrate that the data structure provides a solid statistical foundation to support subsequent model inference.

The implications of these results extend beyond statistical verification. In the context of urban spatial research, the reliability and validity of variables determine whether model inputs can accurately represent environmental structures and district characteristics. The higher internal consistency observed among POI variables suggests that urban functional facilities follow clear clustering logics and planning orientations, forming relatively stable spatial-functional patterns. In contrast, the more dispersed structural characteristics of micro-level visual elements indicate that environmental details within streetscapes are more diverse and open—jointly shaped by multiple factors such as building age, material selection, greenery maintenance, and community governance. This distinction reflects two complementary dimensions of the urban environment. On one hand, functional facilities are more likely to achieve standardization and order through institutional planning. On the other hand, street-level details tend to embody locality and everydayness, exhibiting visual and perceptual richness as well as uniqueness. Overall, the reliability and validity tests demonstrate that the variable system employed in this study possesses a strong data foundation and robust statistical applicability, thereby supporting subsequent perception modeling and contribution analysis based on machine learning. The model performance metrics for each perceptual dimension (MSE, RMSE, MAE, and R

2) are summarized in

Appendix B,

Table A2 for reference.

3.2. Correlation Characteristics and Mechanistic Interpretation of Perceptual Dimensions

The correlation matrix reveals distinct clustering patterns among the built-environment elements of historic districts (

Figure 4), with variables primarily forming two internally coupled structures. The first cluster comprises commercial and service-oriented functional elements, while the second cluster consists of spatial-scene and visual composition factors. This structure reflects the composite characteristics of functional density and scene representation within historic districts and further illustrates the symbiotic relationship between diverse urban activities and spatial semantics.

Within the functional cluster, the high correlations among shop, dining, leisure entertainment (leisure), transportation (trans), and institutional business (instBus) confirm the spatial logic of co-location between commercial and service facilities. Multiple urban functions within historic districts often overlap and interact, jointly shaping a commercial atmosphere characterized by high pedestrian density and a strong sense of vitality. This phenomenon may result not only from planning orientation but also from the combined effects of land-tenure configurations and concentrated consumer demand in high-density districts. However, some of these strong correlations may merely reflect co-location effects rather than direct causal linkages between functions; therefore, the direction and magnitude of such influences require further validation through subsequent modeling.

Variables related to spatial scene and structural composition exhibit another form of consistency. Building components (bldComp), street furniture (stFurn), sky, and road surface (roadSurf) show strong correlations, indicating that spatial openness, façade continuity, and the distribution of street facilities typically influence visual experience in an integrated manner. In narrow alleys, the simultaneous compression of road surface and sky, and in wider streets, their concurrent expansion, create a pattern of structural co-variation among these variables. The moderate positive correlation between green view (grnView) and natural surface (natSurf) also suggests a co-existence pattern among nature-related elements; however, it should be noted that these two variables partially overlap in their semantic definitions, and therefore the strength of their correlation should be interpreted with caution.

Cross-cluster relationships are generally weak, yet several connections hold interpretive significance. The correlations among human presence, dining, and commercial advertisements (commAds) may suggest the attraction effect of commercial facilities, but they may also simply reflect statistical co-occurrence patterns in densely populated areas. The moderate coupling between trans and multiple scene-related variables forms a structural linkage, indicating that transportation infrastructure serves as a critical mediator between functional clustering and spatial perception. Meanwhile, the slight negative correlations between grnView and both dining and trans are more likely to represent spatial differentiation among district segments rather than environmental conflicts, reflecting semantic distinctions between pedestrian-oriented zones and green, residential street environments.

The above correlation structures reveal the parallel variation patterns and semantic coupling logic among environmental elements in historic districts. Commercial functions, activity density, and visual characteristics jointly contribute to the construction of the perceptual framework of historic districts, whereas natural elements exhibit a more dispersed and selectively embedded pattern within the spatial structure (see

Appendix C for details).

3.3. Key Factors Influencing Subjective Perception

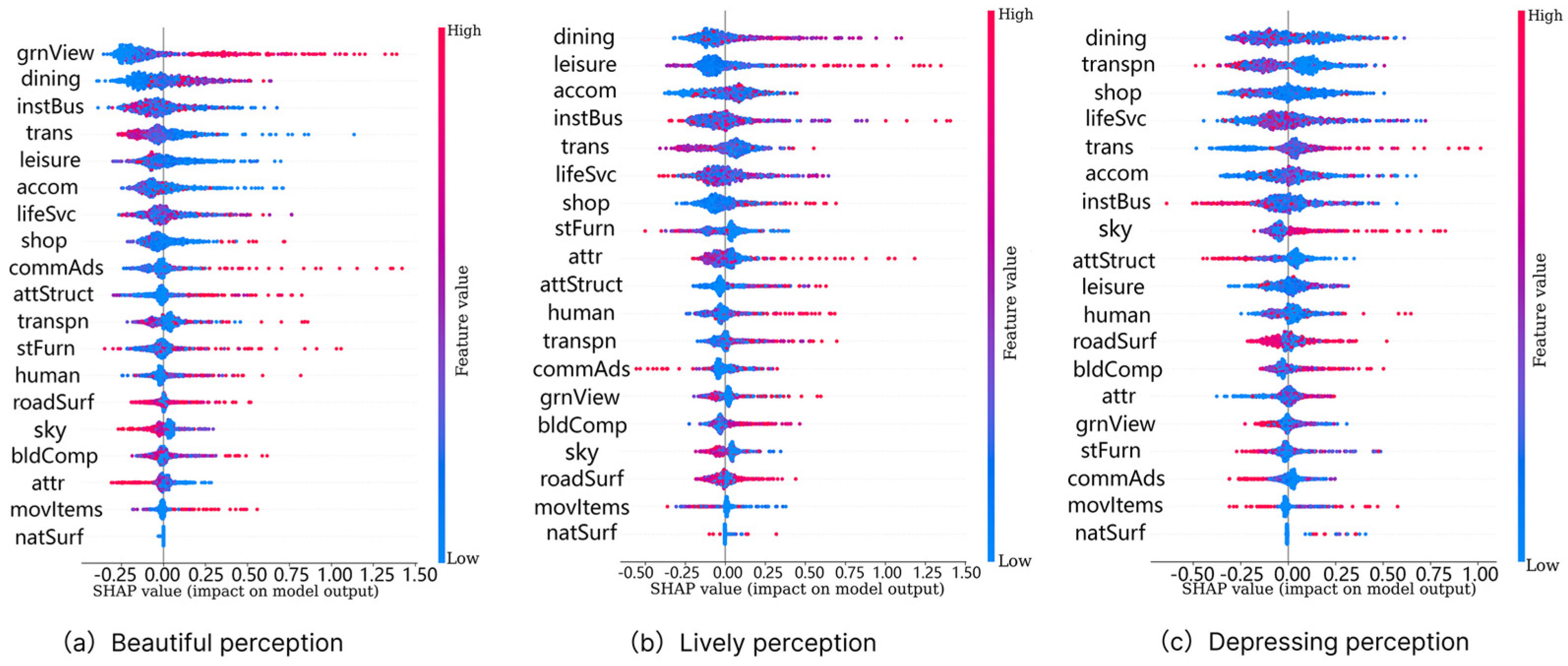

3.3.1. Major Variables Across Perceptual Dimensions

The variable importance results reveal a differentiated structural pattern across the seven perceptual dimensions. First, in the beautiful dimension (

Figure 5a), grnView exhibits a substantially higher contribution than all other variables. This finding indicates that natural elements play a decisive role in shaping visual preference, aligning with previous research emphasizing that “visual greenery is a key source of aesthetic experience”. Notably, greenery is perceived not only as an ecological component but also as a symbolic indicator of a pleasant and high-quality environment. This suggests that, within the visual evaluation of historic districts, greenery remains the most immediate aesthetic cue.

In contrast, the lively dimension is primarily driven by functional elements such as dining, leisure, accommodation (accom), instBus, and trans (

Figure 5b), while showing relatively weak dependence on natural landscapes. The results indicate that perceptions of urban vitality are mainly associated with the density of commercial facilities, the availability of activity opportunities, and spatial accessibility, rather than with green coverage. This finding resonates with a long-standing discussion in urban planning—that a pleasant urban experience arises not only from greenery but also from the richness of urban services and activity settings.

The safe, clean, and wealthy dimensions exhibit highly similar structural patterns (

Figure 6). All three are primarily supported by elements associated with order and management, including instBus, lifeSvc, accom, shop, and commAds, while the contribution of grnView remains relatively limited. In other words, residents and visitors tend to form impressions of safety, cleanliness, and affluence based more on social order, governance performance, and consumer symbolism than on the presence of natural environments. This pattern suggests that perceptions of urban quality are shaped largely by institutional capacity and commercial atmosphere rather than by greenery itself.

Among the emotion-related dimensions, boring and depressing display distinct underlying logics. In the boring dimension (

Figure 6d), grnView again demonstrates significant explanatory power, suggesting that the absence of natural elements tends to evoke feelings of monotony and emptiness. In contrast, in the depressing dimension (

Figure 6e), dining and trans dominate, implying that high-intensity environments characterized by commercial and traffic activities may induce crowding and psychological stress—particularly in historic districts where spatial carrying capacity is limited. This phenomenon indicates that urban vitality and psychological comfort do not follow a linear correspondence but instead exhibit potential perceptual thresholds.

Overall, distinct differentiation is observed across perceptual dimensions in terms of natural elements, functional facilities, and social-order cues. Natural landscapes enhance aesthetic experience, yet their positive effects are not universally applicable. Functional facilities improve convenience and vitality, but in high-density environments, they may also lead to spatial compression and psychological fatigue. Governance and consumer symbols contribute to perceptions of safety and quality, yet they may simultaneously diminish natural affinity and social warmth. These results highlight that spatial strategies in historic districts should vary according to perceptual objectives. Aesthetics, vitality, and psychological comfort cannot be enhanced through a single type of element alone; rather, they depend on the combined configuration and proportional balance of multiple environmental factors (see

Appendix D for details).

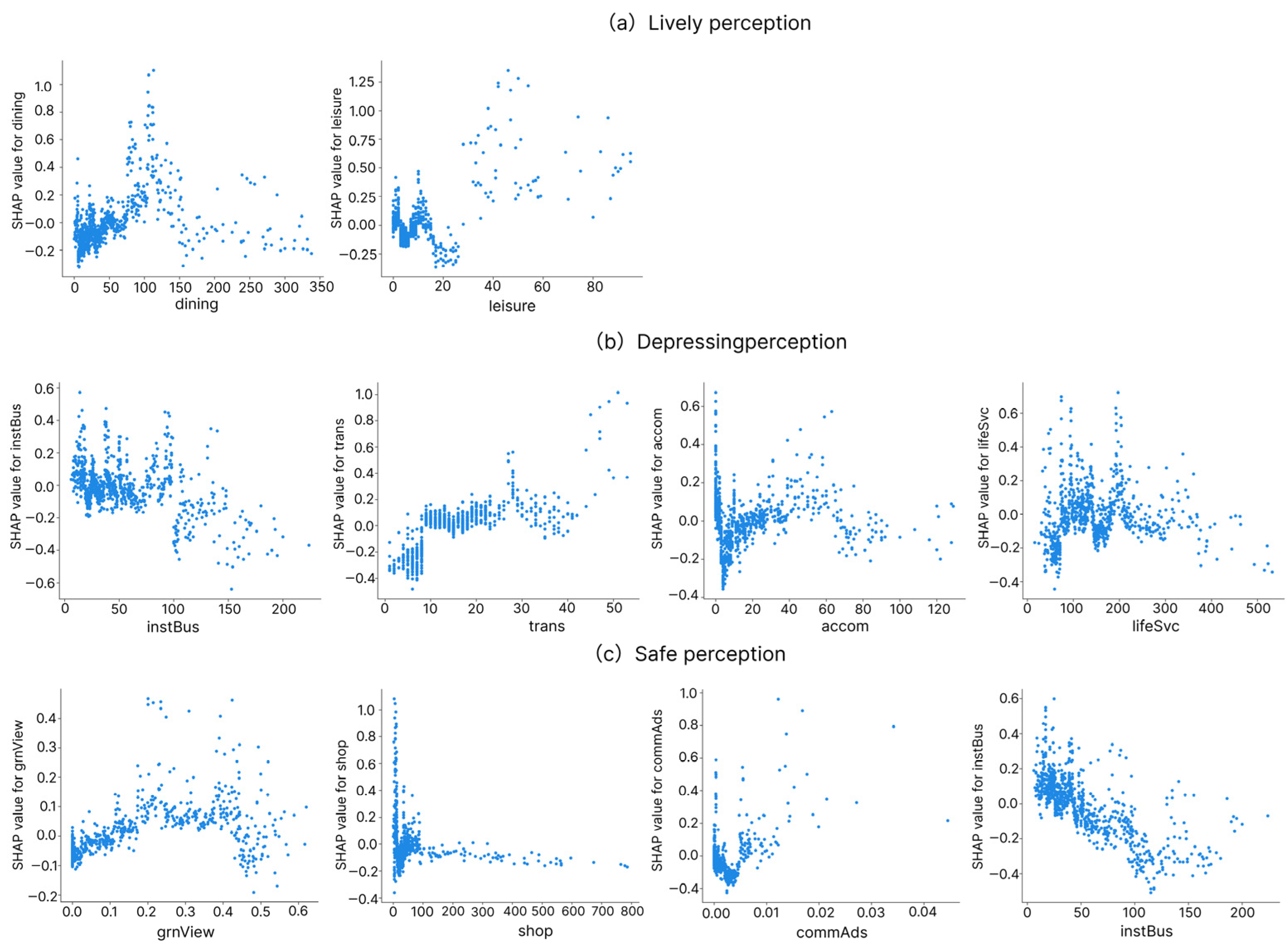

3.3.2. Positive and Negative Contribution Characteristics of Variables Across Perceptual Dimensions

The positive and negative contributions of variables reveal the differentiated roles of various environmental elements in perceptual formation. Overall, elements related to naturalness, functionality, and orderliness exhibit pronounced nonlinear and context-dependent characteristics across different perceptual dimensions, reflecting the complexity and multidimensional interactions underlying perceptual mechanisms in historic districts.

As shown in

Figure 7a, within the beautiful dimension, grnView exhibits the strongest positive contribution, with aesthetic perception rising sharply after moderate green coverage and approaching saturation in the higher-value range. This trend highlights the central role of green landscapes in shaping aesthetic experience, consistent with the existing theoretical consensus on the link between visual greenery and pleasurable perception. In contrast, the positive effects of dining and leisure stem primarily from social interaction and atmospheric liveliness rather than from visual greenery itself. A similar pattern of green enhancement can also be observed in the higher-value ranges of the clean and wealthy dimensions (

Appendix E), though with weaker magnitudes (

Appendix F). This indicates that the advantage of greenery is largely confined to aesthetic contexts, serving more as a supportive cue in perceptions of quality and affluence. Conversely, instBus and trans show negative effects in high-density areas, suggesting that institutional buildings and transport facilities may induce visual pressure and perceptual disturbance. This dual mechanism of “green enhancement and institutional suppression” reveals the underlying tension between aesthetic experience and spatial order.

Distinct from aesthetic experience, the lively dimension demonstrates a functionality-driven vitality mechanism (

Figure 7b). Dining and leisure significantly enhance street vitality, indicating that social interaction and activity diversity are key sources of emotional restoration and environmental attractiveness. However, when instBus and trans occupy excessively high proportions, social spaces become compressed by formal functions, leading to a decline in perceived liveliness. This inverse effect suggests that urban vitality does not simply depend on usage intensity, but rather on the balance between activity types and opportunities for social interaction. Notably, within the lively dimension, the contribution of grnView is markedly weaker, implying that greenery, when detached from social or activity contexts, offers limited psychological appeal. Correspondingly, in the boring dimension (

Appendix E), the absence of commercial facilities and pedestrians significantly increases perceived monotony, while green view can alleviate dullness in low-activity settings, though its influence remains weaker than that of social and commercial stimuli (

Appendix F). Together, these patterns illustrate a “social attraction and spatial emptiness inhibition” mechanism, highlighting the compensatory dynamics between human activity and environmental openness.

The safe, clean, and wealthy dimensions exhibit a highly consistent structural pattern (

Appendix E). The clustering of instBus, accom, shop, and stFurn collectively supports judgments of order and quality, while the role of green view remains relatively secondary (

Appendix F). Notably, in the safe dimension, trans and human variables exert positive effects within moderate ranges, reflecting a safety mechanism driven by appropriate levels of pedestrian presence and public surveillance. In contrast, the depressing dimension (

Figure 7c) reveals that high-density traffic and institutional spaces intensify negative emotions, forming a dual manifestation of “order and pressure”. This inverse relationship is evident in both the SHAP decision pathways and local response intervals (

Appendix F). Meanwhile, dining and shop variables mitigate negative emotions when moderately distributed, indicating that commercial and social activities serve as psychological buffers under certain conditions. These findings suggest that vitality and depression are often co-shaped by the opposite effects of the same types of elements operating at different density ranges, underscoring the nonlinear and context-dependent nature of environmental perception in historic districts.

Overall, green elements dominate the aesthetic dimension, social and recreational functions drive the vitality dimension, and transportation and institutional spaces reinforce the negative emotion dimension. This cross-dimensional contrast reveals the nonlinear logic of perceptual mechanisms: the positive effects of greenery are not universal; functional elements can both stimulate vitality and generate burden; and order-related facilities may shift from cues of attraction to sources of oppression depending on context. Such interwoven relationships underscore the complexity of perceptual structures in historic districts and provide insights for future spatial optimization. Only through a dynamic balance among greenery, order, and safety can the visual and emotional attractiveness of historic districts be sustained over time.

3.4. Analyzing Feature Effects Using Partial Dependence Plots

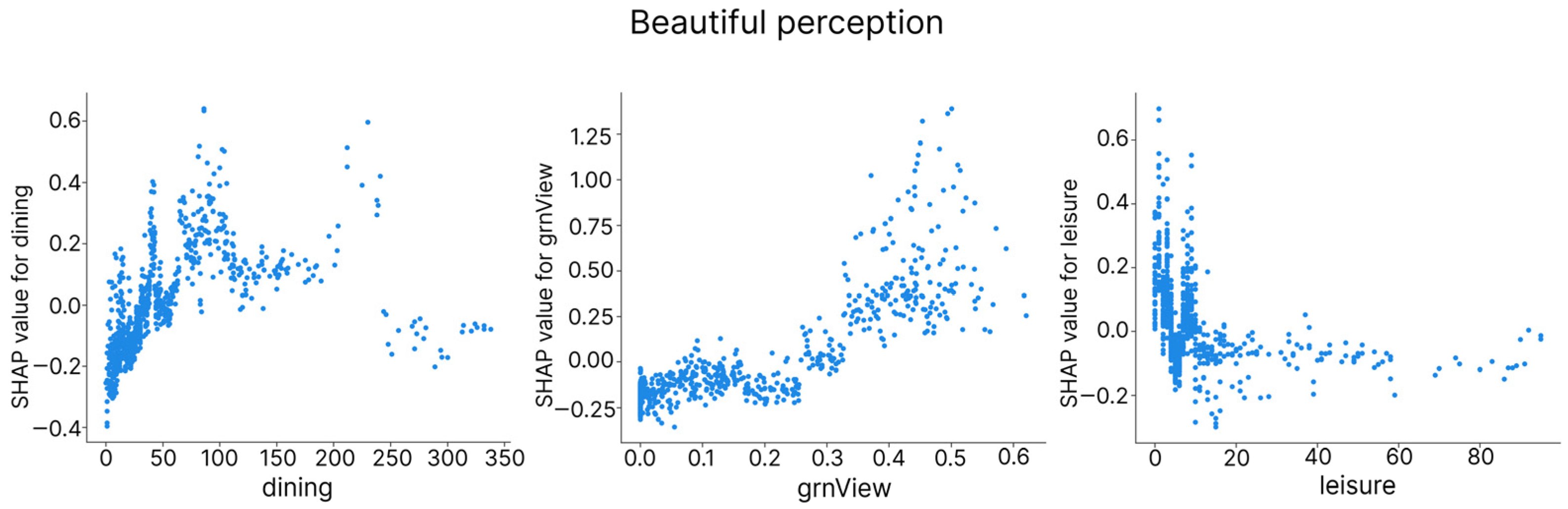

The results of the Partial Dependence analysis reveal that the relationships between built-environment elements and multidimensional perceptions generally exhibit nonlinear response patterns characterized by threshold, saturation, and reversal effects. This indicates that environmental perception does not accumulate linearly; rather, it is significantly activated within specific value ranges and tends to show marginal diminishing or even inverse effects at higher levels.

In the beautiful dimension (

Figure 8), grnView exhibits the most typical threshold pattern: when the green view ratio is below approximately 0.30, its effect is limited; once this threshold is exceeded, perceived beauty increases significantly and then plateaus around 0.55. Moderate clustering of dining and leisure (0.2–0.4) likewise enhances pleasantness, but excessive concentration (>0.6) leads to aesthetic fatigue, illustrating a balance between functional density and visual experience. In contrast, the boring dimension shows an inverse diversity–monotony pattern (

Appendix G). Moderate clustering of dining and lifeSvc (around 0.3) reduces the sense of emptiness, whereas excessive density of instBus and trans (>0.5) results in boredom. GrnView values above 0.4 continue to mitigate monotony, extending its positive aesthetic effect (

Appendix H). In the clean dimension, lifeSvc and accom increase perceived cleanliness within the 0.2–0.3 range, but their influence weakens when the proportion exceeds 0.6. Conversely, higher densities of transportation (>0.4) and commAds (>0.5) reduce the impression of cleanliness, reflecting the visual and cognitive burden caused by functional overconcentration (

Appendix H).

The lively and depressing dimensions form a striking mirror relationship. The former demonstrates a positive threshold effect of moderate enhancement, whereas the latter exhibits a negative threshold pattern characterized by overconcentration reversal. In the lively dimension (

Figure 9a), the proportions of dining and leisure significantly increase perceived vibrancy within the 0.3–0.5 range, peaking around 0.6–0.7 before reaching saturation. In contrast, trans turns negative beyond 0.5, indicating that vitality does not increase monotonically with density, but rather arises from a balanced distribution of pedestrian flow and activity intensity. Conversely, in the depressing dimension (

Figure 9b), instBus and transportation intensify depressive feelings when their proportions exceed 0.5. Accom and lifeSvc provide mild buffering effects at moderate levels, but likewise turn negative under high-density conditions. This reversal relationship suggests that when institutional or transport-oriented spaces become overly concentrated, environmental attractiveness may shift into psychological pressure.

A similar nonlinear threshold effect is also observed in the safe dimension (

Figure 9c). When grnView coverage exceeds 0.3, perceived safety increases significantly, suggesting that natural elements enhance the perception of order by improving visual openness and comfort. Shop and lifeSvc generate stable positive effects within the 0.2–0.4 range, whereas instBus and commAds above 0.5 noticeably weaken the sense of safety. These findings indicate that visual cleanliness and functional order constitute the perceptual foundation of safety. In comparison, the perception of affluence in the wealthy dimension is primarily shaped by commercial and accommodation elements (

Appendix G). Moderate levels of commAds and shop (approximately 0.3–0.5), together with accom (approximately 0.4–0.6), enhance perceived prosperity, whereas excessive density reverses this effect—extending the previously identified order–perception consistency pattern (

Appendix H).

Overall, although different perceptual dimensions emphasize distinct aspects, they all follow a common threshold–saturation–reversal pattern. grnView produces significant perceptual enhancement when exceeding approximately 30–40%, representing a cross-dimensional threshold shared among perceptual categories, whereas high-density zones of instBus and trans consistently generate negative experiences. These findings suggest that spatial optimization in historic districts should not pursue mere quantitative accumulation of elements, but rather aim for balanced functional configuration based on threshold identification, thereby maximizing psychological comfort and perceptual quality while preserving historical character.

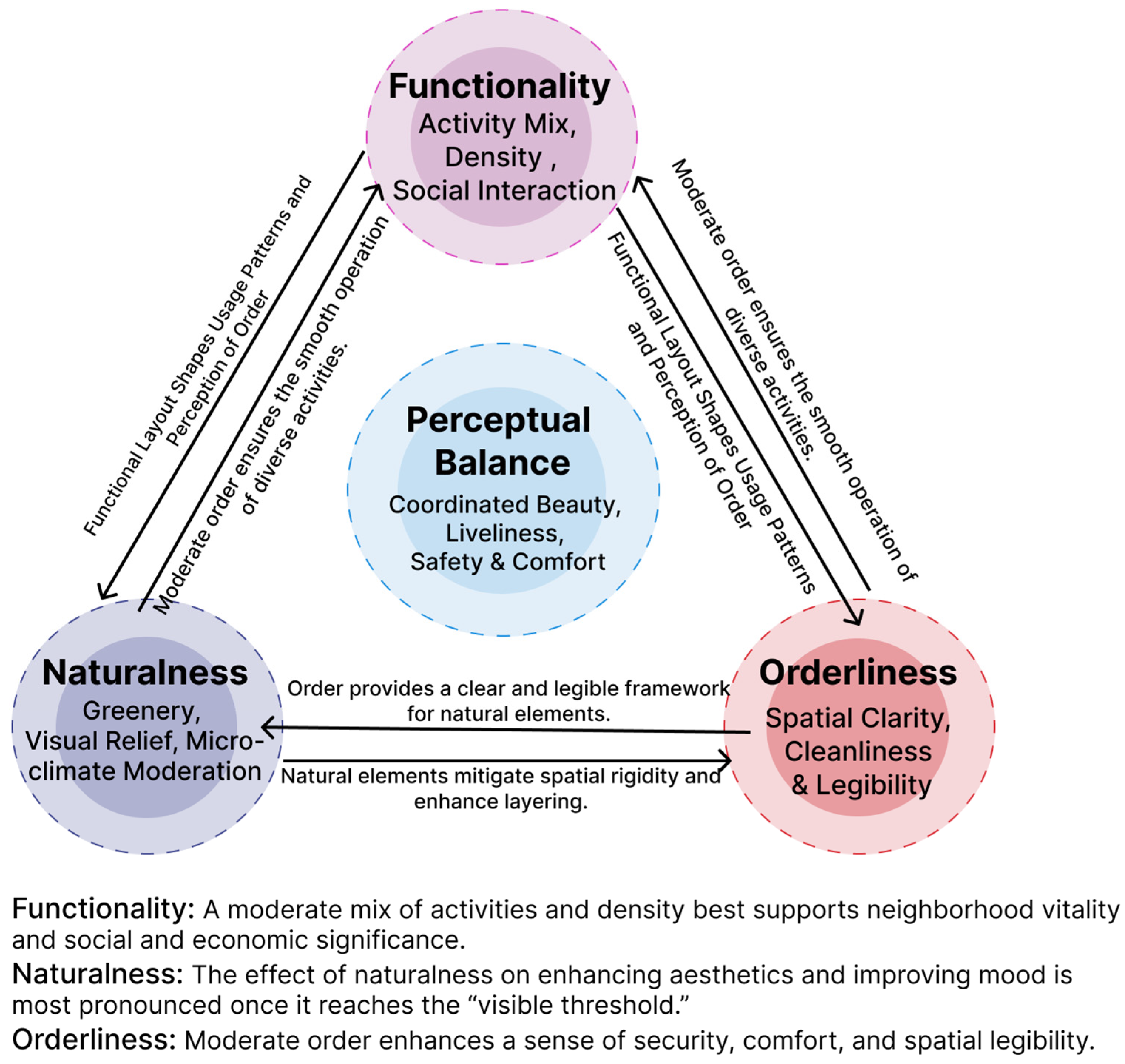

4. Discussion

This study develops a systematic understanding of perceptual mechanisms in historic districts through the integration of multisource spatial data. Its significance lies not only in identifying the directional influence of key environmental variables but also in revealing how these factors jointly structure the ways in which people experience historic districts. By integrating POI functional attributes, micro-scale environmental indicators, and subjective perceptions, the study proposes a perceptual balance framework centered on the triad of natural characteristics, functional characteristics, and orderliness (

Figure 10). This framework explains why historic districts can produce markedly different experiences of aesthetics, liveliness, safety, and comfort. In contrast to traditional approaches that emphasize the effects of single variables, the study demonstrates that experiential quality in historic districts arises from the proportional and structural coordination among these elements rather than from the simple accumulation of individual factors.

Natural characteristics, functional characteristics, and orderliness play distinct roles in shaping experiences within historic districts, yet their mechanisms of influence exhibit clear complementarities. Natural characteristics provide the foundation for positive perception. Their presence enhances aesthetic pleasure and improves overall experience by moderating microclimatic conditions and enriching visual depth. Functional characteristics form the driving system of street life, enabling diverse everyday scenarios such as social interaction, consumption, strolling, and lingering. Orderliness maintains the structural stability of street experience by shaping environmental clarity, visual cleanliness, and spatial legibility. The coexistence of these three dimensions allows historic districts to preserve cultural texture while maintaining everyday spatial flexibility, to support commercial activities while still offering a pleasant pedestrian environment. It is this structural balance, rather than the intensification of any single dimension, that produces street experiences that are simultaneously dynamic and cohesive.

The threshold effects identified in this study further deepen this understanding. The findings indicate that the influences of natural characteristics, functional characteristics, and orderliness do not increase linearly with intensity but instead exert significant effects within specific sensitivity ranges. Once natural characteristics surpass an initial level of visibility, their contributions to aesthetic enhancement and emotional improvement become most pronounced. Functional characteristics most effectively stimulate street vitality when present at moderate levels of mix and density, yet when their concentration exceeds a certain upper limit, they tend to induce visual fatigue, noise disturbance, and social pressure. This aligns with the concepts of moderate complexity and activity load thresholds widely discussed in urban design research. Orderliness strengthens perceptions of safety, comfort, and spatial legibility within an appropriate range, but excessive formalization can suppress social interaction and spatial openness. This result corresponds with recent research emphasizing that environmental order is most conducive to safety and comfort when maintained within a moderate range.

These findings encourage a reconsideration of spatial quality and governance strategies in historic districts. Traditional renewal practices often emphasize isolated improvements such as adding greenery, beautifying façades, or enhancing commercial functions. However, the results of this study indicate that the key to experiential quality lies in the structural coordination among elements across different scales rather than in the enhancement of any single component. Increasing commercial facilities may raise activity density, but it can also disrupt natural characteristics and orderliness, thereby pushing perceptual responses beyond critical thresholds. In contrast, smaller spaces with appropriate internal proportions of natural characteristics, functional characteristics, and orderliness often exhibit greater attractiveness than larger spaces.

Therefore, the perceptual balance model proposed in this study not only offers a new theoretical perspective for explaining experiential differences in historic districts but also provides a structured cognitive basis for urban design. At the macro level, functional configurations should avoid excessive concentration. At the meso level, orderliness should remain clear without becoming overly restrictive. At the micro level, natural elements should maintain a stable level of visual presence. This perspective shifts governance strategies from material upgrading toward experiential enhancement and from localized fixes toward structural adjustment. It also establishes a framework with stronger theoretical depth and practical relevance for the future renewal of historic districts grounded in cultural continuity, everyday life, and resilience.

4.1. Environmental Elements and Mechanisms of Perceptual Formation

The perceptual experience of historic districts is not a direct reflection of their physical attributes, but rather a process through which social meanings are generated in the interaction between people and the environment. The results indicate that grnView exerts a consistent positive effect on the beautiful, safe, and clean dimensions, suggesting that naturalness serves as a fundamental basis for shaping aesthetic experience and psychological safety [

53,

54]. This finding aligns with the Attention Restoration Theory [

55], which posits that natural elements can promote the formation of pleasure and a sense of order by reducing cognitive load. Notably, this effect exhibits a threshold pattern: when the green coverage ratio exceeds approximately 0.2–0.3, positive perceptions increase significantly, echoing the concept of a “recognizable threshold effect” in perceptual psychology. Within the context of historic districts, this naturalness effect is particularly crucial. Because these areas are constrained by spatial morphology and conservation regulations, greenery typically appears in micro-scale forms such as street trees, courtyard vegetation, or façade greening, whose visibility and recognizability become key determinants of psychological comfort. Natural elements provide visual relief and emotional regulation within dense historical fabrics, enabling residents to achieve a balance between a sense of history and a sense of everyday life.

At the same time, certain functional elements display reversal effects. Dining and leisure facilities enhance vibrancy and social interaction when maintained at moderate densities, yet their excessive concentration can induce a sense of pressure and fatigue. This phenomenon can be interpreted through anthropological and social-psychological perspectives: individual experiences of space are not passively received, but are shaped through the cultural meanings attributed to environments. When a place becomes overly shaped by the logic of the experience economy, its original social rhythms and everyday interactions are replaced by commercial imperatives, leading to place alienation and psychological detachment. For historic districts, such alienation is especially pronounced, as their uniqueness stems from heterogeneous rhythms of daily life and layers of cultural memory. When these qualities are replaced by commodified experiences, the complexity of perception reflects an ongoing tension between urban modernity and everyday authenticity, representing a core contradiction that defines the challenges of contemporary historic district renewal.

4.2. Functional Attributes and Social Imagery

Functional attributes not only determine spatial morphology but also profoundly shape the social imagery and cultural identity of urban districts. The significant influence of commercial advertisements and retail facilities on the wealthy and lively dimensions reveals the reproductive mechanism of consumer landscapes in shaping urban imagery. Through visual symbols and consumer atmospheres, commercial elements construct symbolic representations of “prosperity” and “modernity”, transforming historic districts into stages for the display of aesthetic and consumer identities. However, such symbolic prosperity is often accompanied by social exclusion and the erosion of everyday diversity, leading to a typical phenomenon of symbolic gentrification [

56]. Hence, while functional renewal can stimulate economic vitality, it may simultaneously erode the social memory and cultural continuity of historic districts.

This phenomenon becomes even more complex in the context of historic districts. The decline of traditional industries and the influx of high-end commerce often reshape the cultural representation of place, transforming the original spaces of living into spaces of display. From a tourism studies perspective, historic districts are no longer merely residential or commercial areas but have evolved into “places to be gazed upon” [

57]. Pedestrians experience “staged authenticity” through representational symbols, yet the cultural landscapes thus presented are frequently detached from residents’ real lives, creating a dual structure of experience. This tendency toward cultural commodification reveals the dilemma of heritage preservation in globalized cities: the challenge of maintaining economic sustainability while preventing spatial landscapes from being reduced to superficial experiential goods. In other words, functional differentiation is not simply a matter of economic stratification, but represents a redistribution of social identity, cultural capital, and symbolic power within the urban hierarchy.

4.3. Interactions Among Environmental Elements and Mechanisms of Perceptual Balance

Within the same perceptual dimension, the interactions among different environmental elements reveal the complex mechanisms underlying perceptual optimization. Greenery and spatial openness enhance visual permeability and psychological restoration, whereas order-related facilities [

58], while reinforcing a sense of safety, they may simultaneously weaken social interaction and spatial intimacy. This indicates that safety and aesthetics do not inherently coexist, but must be balanced within the tension between regulation and freedom. When urban governance overemphasizes order, it risks fostering the expansion of a “managed aesthetics”, causing districts to lose their everyday flexibility and social vitality.

This issue is particularly pronounced in historic districts. As spatial typologies that simultaneously pursue heritage preservation and modern governance, their renewal processes often encounter tensions among protection, regeneration, and management. The observed perceptual reversals—where order-related facilities contribute positively to the safe dimension but negatively to the depressing one—reflect the latent risks of over-rationalized spaces. Such spaces may appear clean and orderly on the surface, yet they often lack social warmth and interpersonal accessibility. Therefore, spatial governance in historic districts should move beyond a purely safety-oriented logic toward a model of perceptual balance planning, emphasizing micro-scale functional diversity, interface vitality, and maintenance of heterogeneity. Only by preserving social interaction and emotional attachment while safeguarding the historical fabric can historic districts truly achieve the coexistence of safety, aesthetics, and liveability, sustaining their temporal depth and social resilience as “living heritage”.

4.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although this study develops a perception model for historic districts using multisource data, current technological conditions still impose several constraints on urban visual datasets. These limitations do not arise from the research itself but stem from practical restrictions related to data availability and methodological applicability. At the same time, these constraints provide clear directions for methodological refinement and theoretical advancement in the next stage of research.

First, existing studies largely rely on street-view images that are static, captured during daytime, and collected from vehicle-mounted cameras. These forms of data make it difficult to capture the dynamic experiences of historic districts as they change across time and weather conditions. In reality, the atmosphere of a district and the emotional responses it evokes can vary significantly with differences in time of day, seasonal transitions, and climatic situations. However, most available street-view images are provided by commercial mapping platforms whose update frequency is limited. These platforms also face practical constraints in capturing images at night or under special weather conditions due to technical and operational limitations. Future research may explore more flexible image collection approaches, such as crowdsourcing to build street-view databases that cover multiple times of day and various weather situations, including additional nighttime images, seasonal updates, and visual information captured under different climatic conditions. At the same time, low-cost mobile data collection methods and community-based image generation approaches may be explored to overcome the structural limitations of commercial platforms in terms of timing, frequency, and acquisition conditions. Such supplementary data would help to provide a more comprehensive depiction of how historic districts are experienced under different situational contexts.

Second, the vehicle-mounted viewpoint has inherent limitations in viewing height and framing scope, making it difficult to capture spatial details at the pedestrian scale. Many key cues related to perceived safety, comfort, and everyday life—such as façade details, street-level activities, and community interactions—are often not clearly visible in vehicle-based imagery. Future research should incorporate pedestrian-perspective data sources such as wearable cameras, mobile mapping imagery, and immersive virtual reality roaming experiments. Integrating these visual materials with physiological responses such as eye tracking, skin conductance, and heart rate, and further combining them with behavioral trajectory data, can help establish a more robust connection between online visual evaluations and actual walking experiences.

Third, the subjective evaluation data used in this study were collected from participants who were able to take part in an online survey and were familiar with visual assessment tasks. This group demonstrated clear advantages in task comprehension, rating consistency, and cooperation with online experimental procedures, which helped ensure the quality and reliability of the data collection process. However, the social and cultural backgrounds of this sample group are relatively concentrated, which makes it difficult to fully represent the cognitive and experiential diversity of the broader population. In reality, differences in culture, lifestyle, and social experience can strongly shape how people understand environmental concepts such as safety, beauty, wealth, and boredom. Future research should gradually establish a comparative framework across cultures, regions, and communities, including expanding sample sources, developing multilingual systems, and conducting cultural calibration analyses. By creating standardized perception benchmarks across cities, the generalizability and theoretical explanatory power of the research can be further strengthened.

Fourth, the current infrastructure for urban data remains fragmented, which limits the multimodal integration of urban experience. Street-view imagery, soundscapes, microclimatic data, and human behavioral signals differ substantially in sampling frequency, spatial scale, and semantic representation, creating bottlenecks for cross-modal alignment and coordinated analysis. An important direction for future research is therefore the development of an aligned multimodal perception database, which would allow for a more systematic representation of experiential trajectories and deepen theoretical understanding of the mechanisms through which perception is formed.

Finally, advancing urban perception research to a higher level requires the coordinated development of technological systems, institutional arrangements, and data platforms. Establishing open data standards, building shared perception databases across cities, developing unified evaluation protocols for virtual and augmented reality, and linking these tools with urban computing frameworks such as digital twins will provide the foundation for comparative studies across cities and cultures. These efforts will further shift the renewal strategies of historic districts from evaluations focused on static landscapes toward integrated governance approaches that emphasize experience, culture, and resilience.

5. Conclusions

This study focused on six historic districts in Shanghai and constructed a framework linking environmental elements and human perception by integrating street-view imagery, POI data, and subjective evaluations. The results indicate that the experience of historic districts is not a direct projection of single physical attributes, but rather a dynamic equilibrium formed among naturalness, functionality, and orderliness. Green view enhances aesthetic appeal and comfort; commercial and service elements support vitality and opportunities for use; and institutional and transportation factors reinforce cues of order and safety. These three categories of elements exhibit directional variations under different intensities and combinations, suggesting that the perceptual structure of historic districts reflects multi-element synergies rather than simple additive effects.

At the theoretical level, this study first established a verifiable explanatory chain linking urban imagery, environmental elements, and psychological perception, thereby clarifying the primary cues and relative weights of different perceptual dimensions. Further results reveal that aesthetics and vitality are not necessarily aligned: while an increase in functional intensity may create more opportunities for social interaction, it can also induce crowding and stress, exposing a common experiential tension within historic districts. Hence, the attractiveness of historic districts arises from the combined effects of openness, activity, and cultural continuity, rather than from a unidirectional increase in either naturalness or functionality.

At the methodological level, this study established a scalable and reproducible quantitative pathway supported by multi-source spatial data and interpretable machine learning. Street-view pixel composition and POI functional structures were integrated into a unified modeling framework, in which feature contributions and local responses jointly provided directional and interval information for each variable, allowing the relationships between environmental factors and perceptual dimensions to be traced and verified. Compared with conventional appearance assessments that rely heavily on expert judgment, this framework ensures consistent measurement standards across multiple spatial scales.

At the practical level, this study highlights that the design and management of historic districts should pay close attention to threshold effects and proportional relationships among environmental cues. Based on the quantitative results, several practice-oriented principles can be proposed. First, visual greenery within the approximate range of 0.30 to 0.55 produces the most stable improvements in aesthetic quality and comfort. This suggests that historic districts should promote an appropriate level of visible greenery, primarily through street trees, green seams, and micro green spaces, while avoiding excessive coverage that obscures façades and historical patterns. Second, dining, leisure, and neighborhood service facilities support urban vitality most effectively when their combined presence falls within the approximate range of 0.20 to 0.40. When densities exceed about 0.60, issues such as noise, crowding, and visual fatigue are more likely to occur, indicating the need for micro-scale spatial arrangements and functional layering to regulate density. Third, institutional and traffic-related elements can enhance the perception of order when their visibility remains within moderate levels of approximately 0.20 to 0.50. However, excessive exposure of these features can weaken the sense of spatial affinity, and they should therefore be moderated through façade detailing, street furniture, and material integration. Overall, these principles converge on a central understanding: enhancing the experiential quality of historic districts does not rely on maximizing any single environmental element, but rather on maintaining an appropriate proportional balance among greenery, activity intensity, and spatial order. This proportional relationship can be translated directly into design control parameters, offering quantitative guidance for architectural renovation, streetscape improvement, façade conservation, and functional allocation. In doing so, historic districts can accommodate contemporary everyday use while simultaneously sustaining and enriching their cultural and experiential significance.

Under current conditions, this study still faces several domain-wide limitations. These constraints do not alter the directional validity of the conclusions but may affect the extent and granularity of their generalization. The street-view imagery used in this research originates from platform-based periodic collections, which lack sufficient coverage of nighttime scenes, extreme weather, and festive events—thus limiting the capture of temporal rhythms and group-specific variations. The update frequency and visibility rules of POI data are influenced by platform operations, leading to inconsistencies in timeliness and accuracy across business types. Moreover, most images reflect vehicular perspectives, potentially underrepresenting pedestrian micro-spaces and inner-block environments. The subjective evaluation samples were primarily collected from participants capable of engaging online, whose cultural backgrounds and lifestyles may influence their perceptual boundaries of safety, wealth, and cleanliness. Comprehensive improvements in temporal coverage, scene detail, and participant diversity would require higher data collection costs, cross-departmental collaboration, and the establishment of more mature open-data standards.

Building on the above understanding, future work should advance progressively rather than seeking immediate comprehensiveness. When conditions permit, temporal street-view data, pedestrian-perspective imagery, soundscape information, and microclimatic data can be incorporated to depict experiential trajectories across day–night cycles, seasons, and activity periods. Experimental settings could further integrate eye-tracking, physiological responses, and virtual reality roaming to compare the consistency between online image-based evaluations and real-world experiences. Additionally, developing standardized perception databases across cities and population groups would allow cultural and social heterogeneity to be embedded within the indicator system. These three research pathways—corresponding, respectively, to the temporal, sensory, and population dimensions—complement and naturally extend the analytical framework proposed in this study.

Overall, this study identified the key factors and principal ranges influencing the multidimensional perception of historic districts, providing quantitative evidence linking spatial composition to experiential quality. The value of this research lies not in resolving all issues at once, but in establishing a sustainable and extensible foundation for both technical exploration and cognitive understanding. With the continued advancement of data collection, open standards, and urban governance, the proportional relationships among greenery, activity, and order will be more precisely delineated, enabling the renewal of historic districts to evolve beyond physical restoration toward the integrated enhancement of experiential quality and cultural continuity.