Digital Finance, Regional Infrastructure, and Urban Carbon-Emission Efficiency: A Spatial Nonlinear Analysis Based on the New Western Land–Sea Corridor

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Definition, Measurement, and Driving Factors of CEE

2.2. Economic and Environmental Effects of DF

2.3. The Impact of Infrastructure on the Economy and the Environment

2.4. Literature Summary

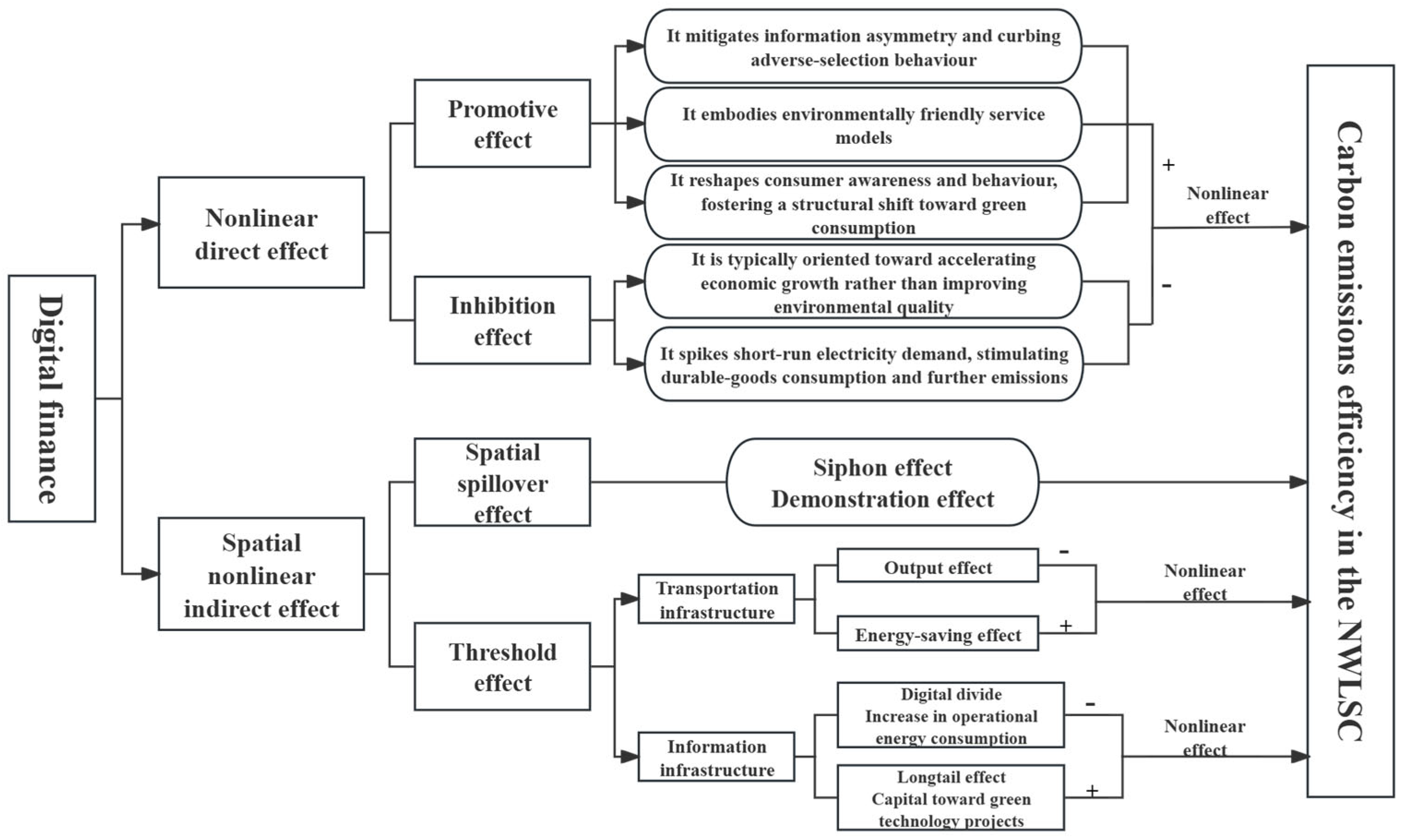

3. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

3.1. The Nonlinear Effect of DF on CEE

3.2. The Spatial Spillover Effect of DF on CEE

3.3. The Nonlinear Indirect Impact Pathways of DF on CEE

3.3.1. Nonlinear Indirect Effect of Transportation Infrastructure

3.3.2. Nonlinear Indirect Effect of Information Infrastructure

4. Methodology and Data

4.1. Econometric Model

4.2. Variables Selection

4.2.1. Explained Variable

4.2.2. Explanatory Variable

4.2.3. Transition Variables

4.2.4. Control Variables

4.2.5. NDDF with Desired and Undesired Outputs

4.3. Regional Background and Data Sources

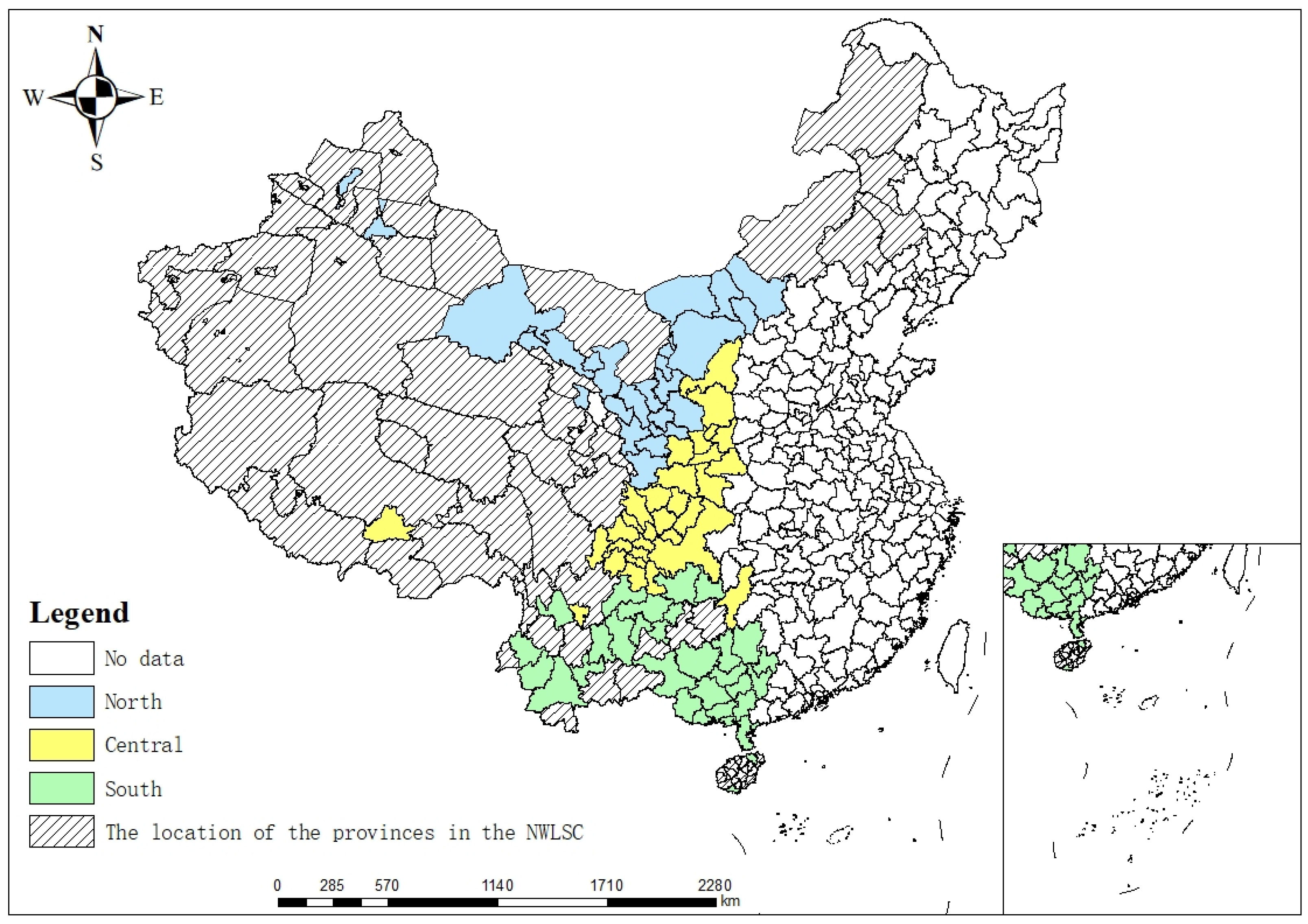

4.3.1. Research Background

4.3.2. Data Sources and Descriptive Statistics

5. Empirical Results

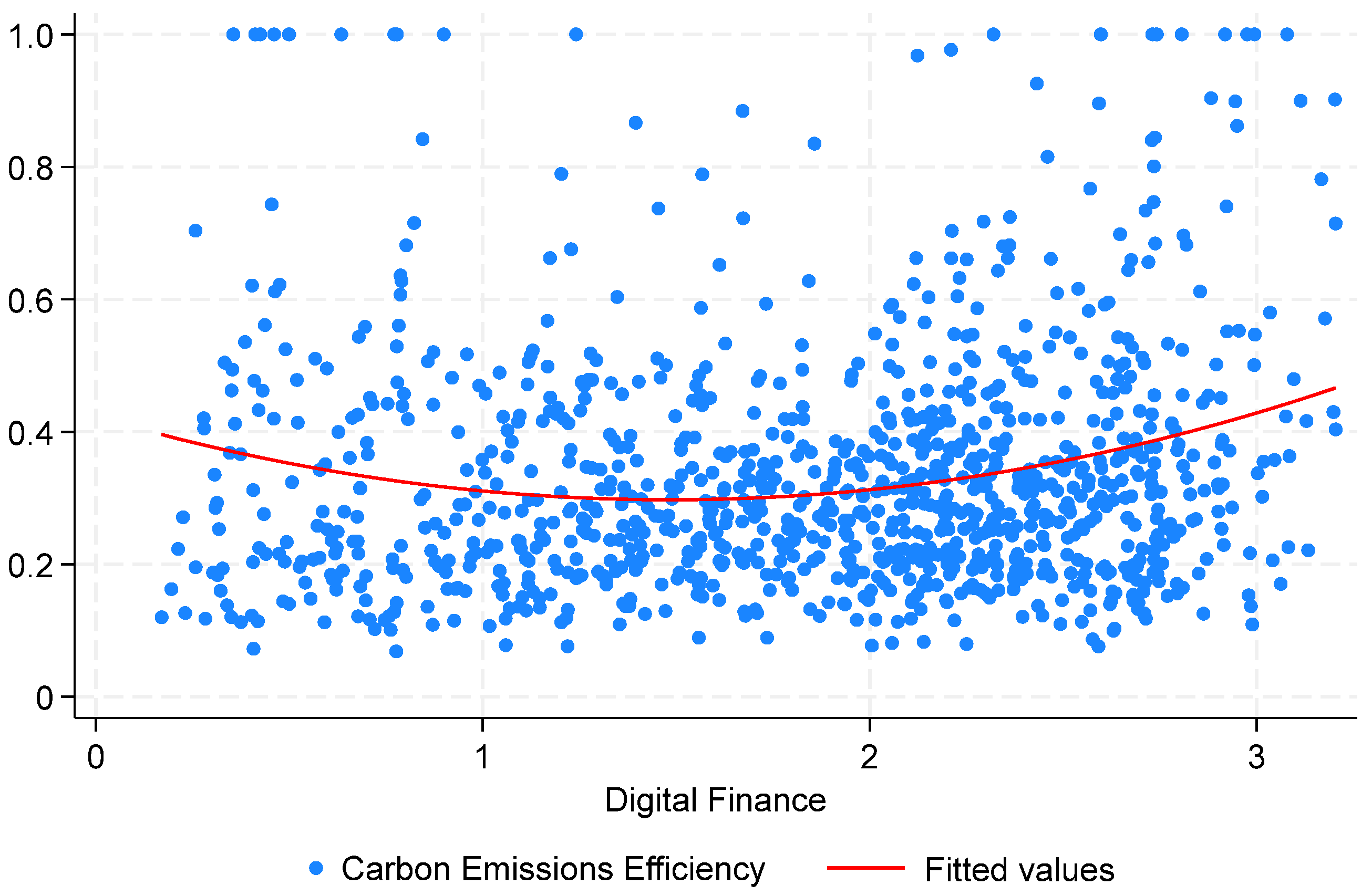

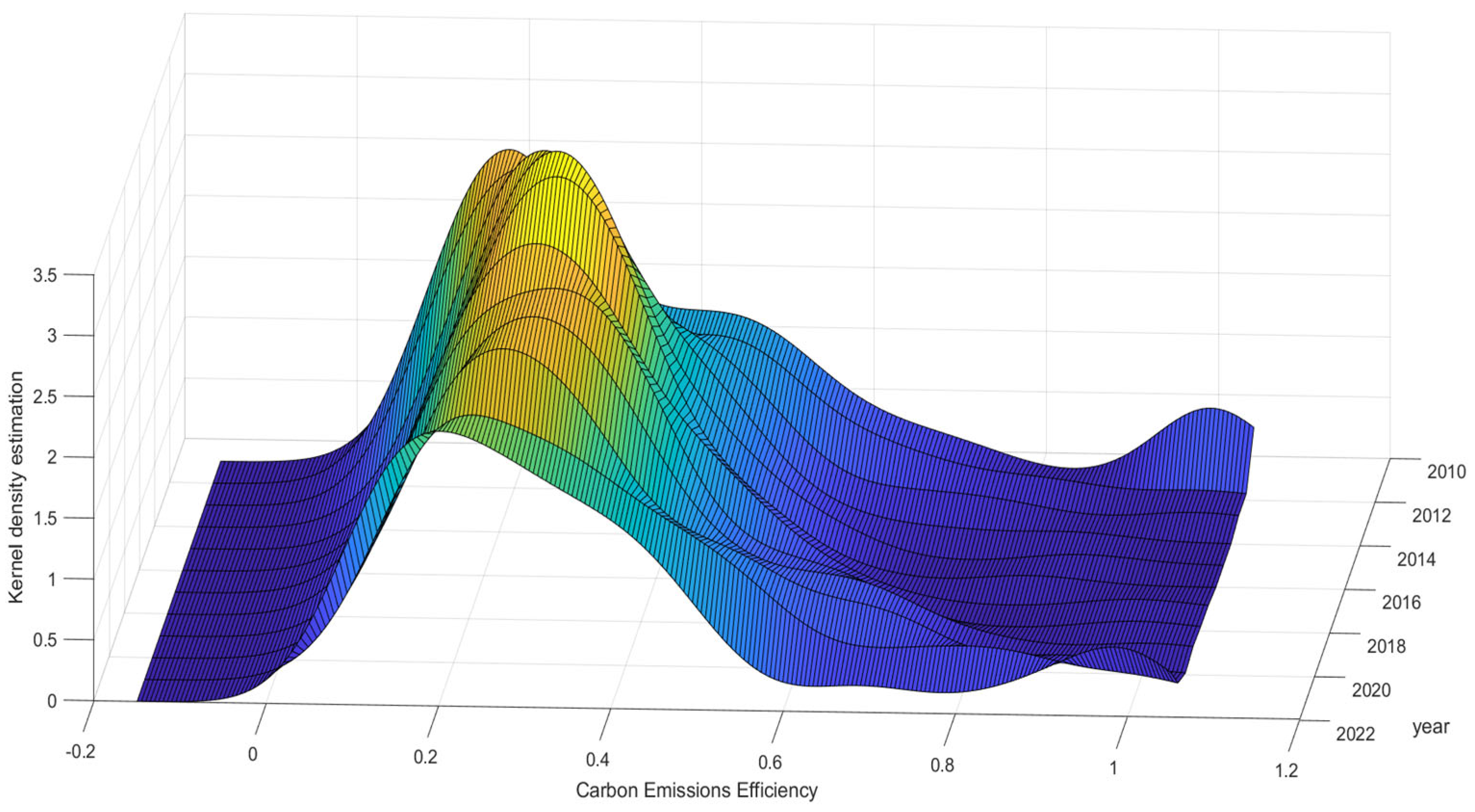

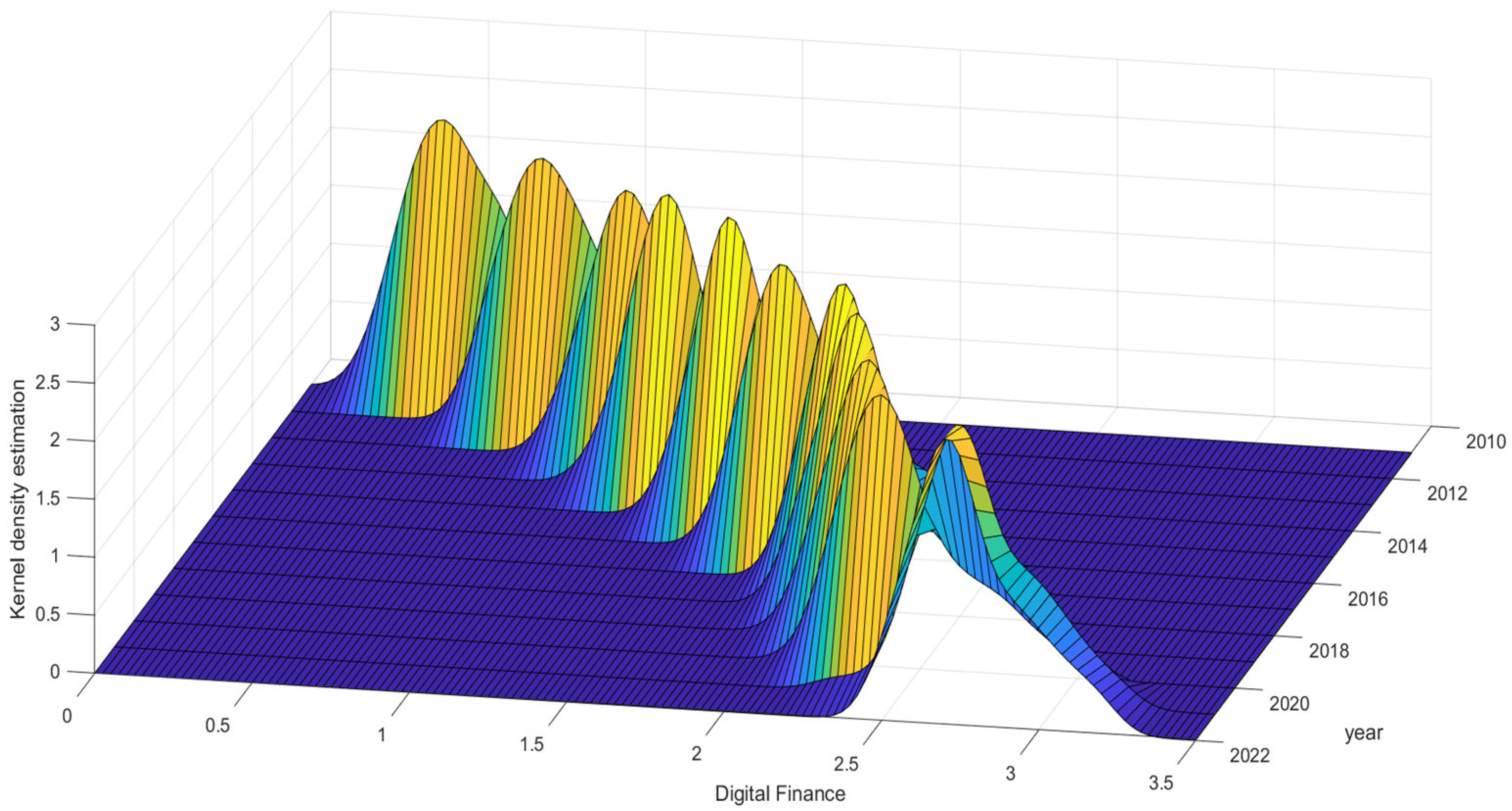

5.1. Analysis of the NWLSC Typical Facts

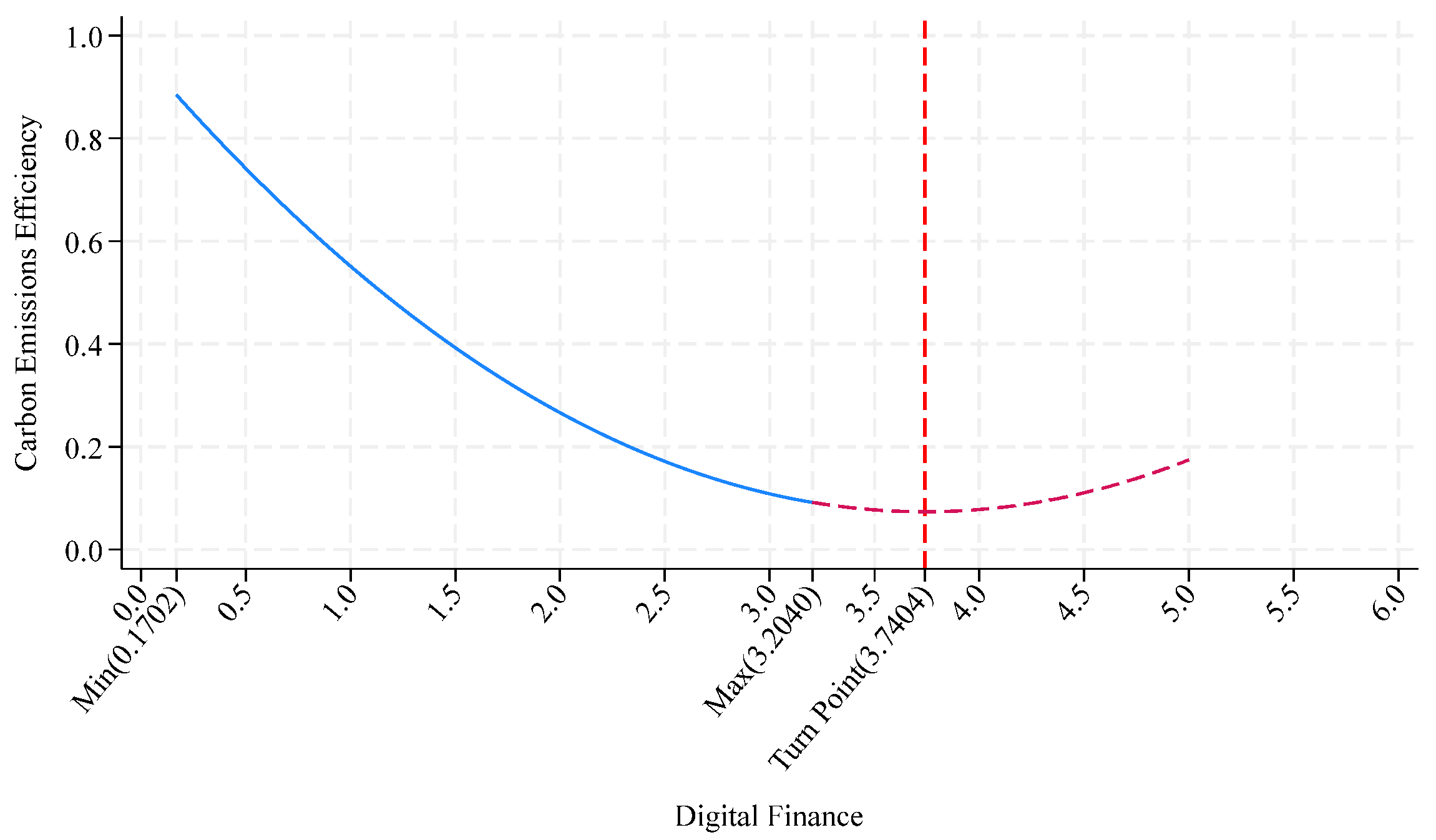

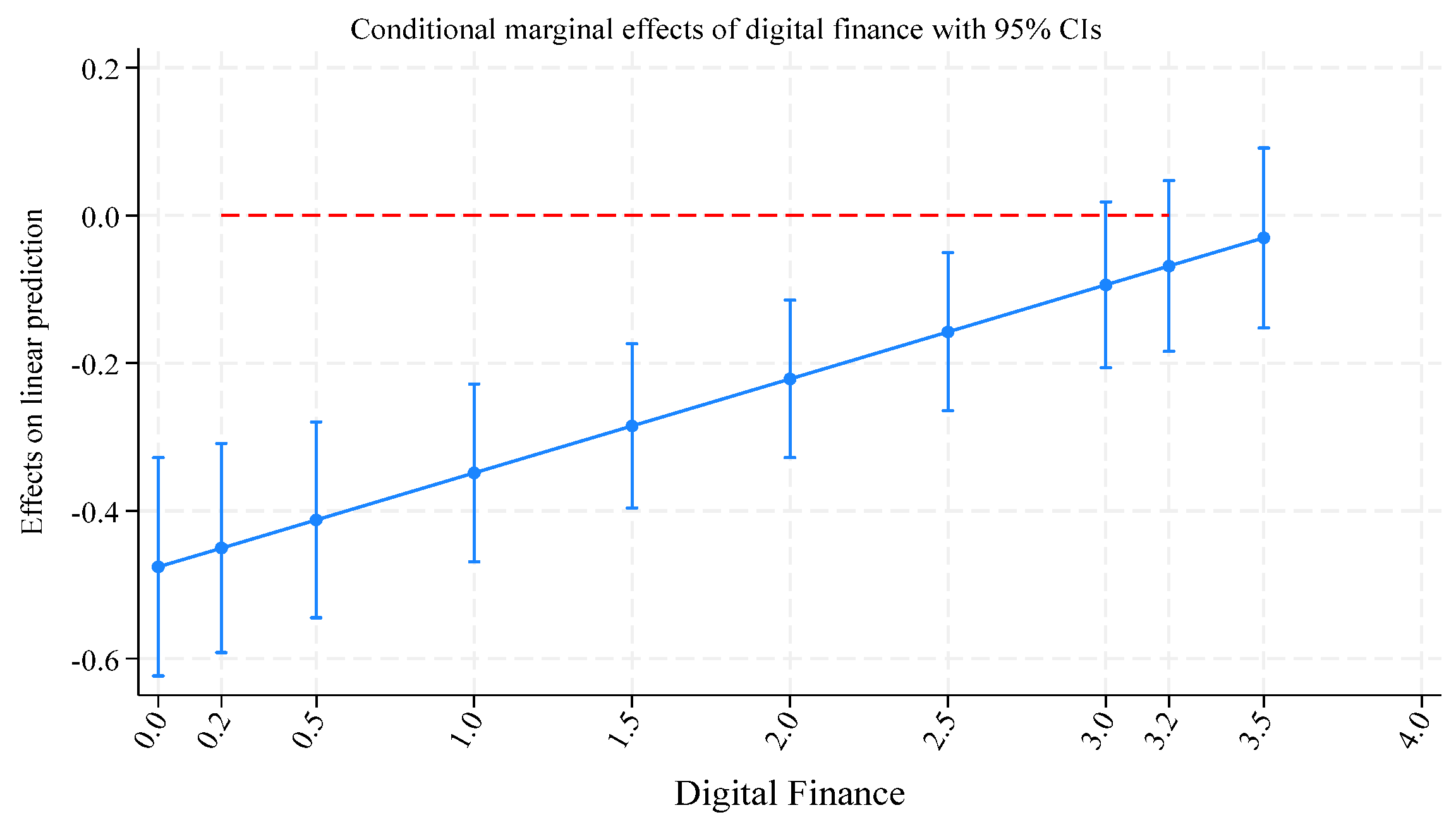

5.2. Benchmark Regression Results

5.3. Endogeneity Tests

5.4. Robustness Tests

5.4.1. Winsorization of Core Variables

5.4.2. Replace Explanatory Variable

5.4.3. Replace the Estimation Model

5.4.4. Estimation of Reduced Samples

5.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.5.1. Regional Heterogeneity

5.5.2. Temporal Heterogeneity

5.5.3. Quantile Estimation Results

5.6. Spatial Nonlinear Effect and Mechanism Analysis

5.6.1. Spatial Model Setting

5.6.2. Nonlinear Test and Model Selection

5.6.3. Parameter Estimation

6. Conclusion and Recommendation

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Policy Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF | −0.151 *** | −0.282 ** | −0.181 *** | −0.467 *** |

| (−4.473) | (−2.571) | (−8.570) | (−5.952) | |

| DF2 | 0.055 *** | 0.048 ** | 0.054 *** | 0.058 *** |

| (5.723) | (2.164) | (10.091) | (4.444) | |

| lnRGDP | −0.003 | 0.006 | 0.064 ** | 0.048 * |

| (−0.158) | (0.298) | (2.538) | (1.721) | |

| FSTE | 0.162 | 0.146 | 0.664 *** | 0.810 *** |

| (1.051) | (0.935) | (4.857) | (5.786) | |

| FD | 0.215 *** | 0.311 *** | −0.136 ** | −0.121 ** |

| (4.753) | (5.989) | (−2.388) | (−2.030) | |

| STRU | −0.035 *** | −0.033 *** | −0.020 ** | −0.038 *** |

| (−3.898) | (−3.507) | (−1.996) | (−3.488) | |

| ER | −0.035 *** | −0.038 *** | 0.000 | −0.001 |

| (−8.481) | (−8.937) | (0.123) | (−0.315) | |

| Constant | 0.406 ** | 0.558 *** | −0.274 | 0.008 |

| (2.226) | (2.874) | (−1.093) | (0.030) | |

| City FE | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| Year FE | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| N | 1056 | 1056 | 1056 | 1056 |

| R2 | 0.161 | 0.154 | 0.140 | 0.182 |

| Log-L | 392.149 | 401.730 | 1098.730 | 1124.846 |

| AIC | −768.299 | −787.459 | −2181.461 | −2211.692 |

| BIC | −728.601 | −747.761 | −2141.763 | −2117.409 |

References

- Xie, R.; Fang, J.; Liu, C. The effects of transportation infrastructure on urban carbon emissions. Appl. Energy 2017, 196, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, S.A.; Inekwe, J.; Ivanovski, K.; Smyth, R. Transport infrastructure and CO2 emissions in the OECD over the long run. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 95, 102857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhou, D.; Wang, Q. How information and communication technology drives carbon emissions: A sector-level analysis for China. Energy Econ. 2018, 81, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, Y. Influence of digital finance and green technology innovation on China’s carbon emission efficiency: Empirical analysis based on spatial metrology. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Zhao, M.; Liu, Z. How does digital trade impact urban carbon emissions efficiency? Evidence from China’s cross-border e-commerce pilot zones. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 456, 142363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Yan, J.; Cai, D. Exploring the spatial spillover effect of industrial structural upgrading on carbon emissions efficiency: Evidence from China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 391, 126539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Ma, R.; Wu, L. Market-based solution in China to finance the clean from the dirty. Fundam. Res. 2024, 4, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, J.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, X. Green credit, environmentally induced R&D and low carbon transition: Evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 89132–89155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Chen, T.; Wang, C. Spatial impact of digital finance on carbon productivity. Geosci. Front. 2024, 15, 101674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Ang, B.; Han, J. Total factor carbon emission performance: A Malmquist index analysis. Energy Econ. 2010, 32, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Hamilton, R.; Tippett, M. Cost efficiency of the Chinese banking sector: A comparison of stochastic frontier analysis and data envelopment analysis. Econ. Model. 2014, 36, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Zhang, N.; Zhou, P. Efficiency and abatement costs of energy-related CO2 emissions in China: A slacks-based efficiency measure. Appl. Energy 2012, 98, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, K.; Lu, H.; Yu, K. Sources of the potential CO2 emission reduction in China: A nonparametric meta-frontier approach. Appl. Energy 2014, 115, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Zeng, L.; Li, P.; Lu, H.; Hu, H.; Li, C.; Zheng, M.; Li, H.; Yu, Z.; Yuan, D.; et al. China’s transportation sector carbon dioxide emissions efficiency and its influencing factors based on the EBM DEA model with undesirable outputs and spatial durbin model. Energy 2022, 238, 121934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Deng, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, F.; Liang, S. Carbon emission efficiency in China: A spatial panel data analysis. China Econ. Rev. 2019, 56, 101313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, A.; Xue, Q.; Zhao, R.; Wang, D. Renewable energy technological innovation, market forces, and carbon emission efficiency. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 796, 148908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Tang, L. Environmental regulation and the growth of the total-factor carbon productivity of China’s industries: Evidence from the implementation of action plan of air pollution prevention and control. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 296, 113078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Zhao, S.; Tang, T. Does green finance agglomeration improve carbon emission performance in China? A perspective of spatial spillover. Appl. Energy 2024, 358, 112561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broby, D.; Hoepner, A.; Klausmann, J.; Adamsson, H. The Output and Productivity Benefits of Fintech Collaboration: Scotland and Ireland. SIFI Fintech 2018, 1–13. Available online: https://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/64269/1/Broby_etal_2018_The_output_and_productivity_benefits_of_fintech_collaboration_Scotland_and_Ireland.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Demertzis, M.; Merler, S.; Wolff, G.B. Capital markets union and the fintech opportunity. J. Financ. Regul. 2018, 4, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Pamuk, H.; Ramrattan, R.; Uras, B.R. Payment Instruments, Finance and Development. J. Dev. Econ. 2018, 133, 162–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Luan, L.; Wu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Hsu, Y. Can digital financial inclusion promote China’s economic growth? Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2021, 78, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Tang, X. The impact of digital inclusive finance on sustainable economic growth in China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 50, 103234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Song, J.; Lee, C.C. Can digital finance narrow the regional disparities in the quality of economic growth? Evidence from China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 76, 502–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Clercq, M.; D’Haese, M.; Buysse, J. Economic growth and broadband access: The European urban-rural digital divide. Telecommun. Policy 2023, 47, 102579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.A.H.; Hussain, M.; Zaman, Q.U. Dynamic linka-ges between financial inclusion and carbon emissions: Evidence from selected OECD countries. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 4, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; Wang, F. How does digital inclusive finance affect carbon intensity? Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 75, 174–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihombo, S.; Saud, S.; Ahmed, Z.; Chen, S. The effects of research and development and financial development on CO2 emissions: Evidence from selected WAME economies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 28, 51149–51159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wu, K.; Cao, Y.; Sun, H. Digital inclusive finance and consumption-based embodied carbon emissions: A dual perspective of consumption and industry upgrading. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P.; Bechtold, S.; Cassar, L.; Herz, H. The causal effects of competition on innovation: Experimental evidence. J. Law Econ. Organ. 2018, 34, 162–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum-Snow, N. Did highways cause suburbanization? Q. J. Econ. 2007, 122, 775–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duranton, G.; Turner, M.A. Urban growth and transportation. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2012, 79, 1407–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duranton, G.; Morrow, P.M.; Turner, M.A. Roads and trade: Evidence from the US. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2014, 81, 681–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum-Snow, N.; Brandt, L.; Henderson, V.J.; Turner, M.A.; Zhang, Q. Roads, railroads and decentralization of Chinese cities. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2017, 99, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeberese, A.B.; Chen, M. Intranational trade costs, product scope and productivity: Evidence from India’s golden quadrilateral project. J. Dev. Econ. 2022, 156, 102791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, E.; Lopez, E.; Monzon, A. Territorial cohesion impacts of high-speed rail at different planning levels. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 24, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Sun, W.; Zheng, S. Transportation network and venture capital mobility: An analysis of air travel and high-speed rail in China. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 88, 102852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Xiao, F. Research on the mechanism of information infrastructure affecting industrial structure upgrading. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominković, D.F.; Bačeković, I.; Pedersen, A.S.; Krajačić, G. The future of transportation in sustainable energy systems: Opportunities and barriers in a clean energy transition. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 1823–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, W.; Li, F.; Zhao, W. Congestion assessment for the Belt and Road countries considering carbon emission reduction. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Chen, Y. Will land transport infrastructure affect the energy and carbon dioxide emissions performance of China’s manufacturing industry? Appl. Energy 2020, 260, 114266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, F.; Tauqir, A. The effects of infrastructure development and carbon emissions on economic growth. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 36259–36273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Ma, C.; Chen, Y.; Wen, A.; Hu, M.; Luo, Q. Carbon Reduction Effects in Transport Infrastructure: The Mediating Roles of Collusive Behavior and Digital Control Technologies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, A.O.; Dzator, J.; Dzator, M.; Salim, R. Unveiling the effect of transport infrastructure and technological innovation on economic growth, energy consumption and CO2 emissions. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 182, 121843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Cao, S.; Xu, X. The development of highway infrastructure and CO2 emissions: The mediating role of agglomeration. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 337, 130501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Burnett, J.W.; Fletcher, J.J. Spatial analysis of China province-level CO2 emission intensity. Renew. Sustain. Energy. Rev. 2014, 33, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Du, K.; Shao, S. Transportation infrastructure and carbon emissions: New evidence with spatial spillover and endogeneity. Energy 2024, 297, 131268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Li, Y.; Qin, C.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, C. Information infrastructure and greenhouse gas emission performance in urban China: A difference-in-differences analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 316, 115252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, Y.; Ji, Z.; Liang, H.; Wang, T.; Zheng, Y. Has information infrastructure reduced carbon emissions?-Evidence from panel data analysis of Chinese cities. Buildings 2022, 12, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Li, L.; Fei, J. Can “new infrastructure” reverse the “growth with pollution” profit growth pattern? An empirical analysis based on listed companies in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 30441–30457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhou, C.; Wang, S. Does modernization affect carbon dioxide emissions A panel data analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 663, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, D.; Liu, J.; Liu, M.; Sun, J. Does information infrastructure and technological infrastructure reduce carbon dioxide emissions in the context of sustainable development? Examining spatial spillover effect. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 1599–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Long, R. Can a carbon emission trading scheme generate the Porter effect? Evidence from pilot areas in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdi, H.; Sbia, R.; Shahbaz, M. The nexus between electricity consumption and economic growth in Bahrain. Econ. Model. 2014, 38, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avom, D.; Nkengfack, H.; Fotio, H.K.; Totouom, A. ICT and environmental quality in Sub-Saharan Africa: Effects and transmission channels. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 155, 120028–120040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Wang, Z.; Liu, L. Digital Inclusive Finance and Carbon Emissions Efficiency: Evidence from China’s Economic Zones. Sustainability 2025, 17, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Xie, J. Digital Economy and carbon emissions efficiency in three major urban agglomerations of China: A U-shaped journey towards green development. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Xue, L.; Zhang, H.; Chen, P.; Yang, J.; Niu, B. Spatiotemporal analysis of carbon emissions efficiency across economic development stages and synergistic emissions reduction in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 377, 124609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Tan, Q.; Chen, Y. Digital Inclusive Finance, Factor Distortion and Green Total Factor Productivity. West Forum 2021, 31, 82–96. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Xiao, J. The Impact of Digital Finance on Household Consumption: Evidence from China. Econ. Model. 2020, 86, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Wu, H.; Li, R. Digital finance and household carbon emissions in China. China Econ. Rev. 2022, 76, 101872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Li, A.; Wu, J. How does digital finance affect environmental total factor productivity: A comprehensive analysis based on econometric model. Environ. Dev. 2022, 44, 100795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Laplante, B.; Mamingi, N. Pollution and Capital Markets in Developing Countries. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2001, 42, 310–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Gao, W.; Han, Q.; Qi, L.; Cui, Y.; Chen, Y. Digitalization and Carbon Emissions: How Does Digital City Construction Affect China’s Carbon Emission Reduction? Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 87, 104201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadorsky, P. The Impact of Financial Development on Energy Consumption in Emerging Economies. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 2528–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Song, F. Non-Linear Impacts and Spatial Spillover of Digital Finance on Green Total Factor Productivity: An Empirical Study of Smart Cities in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, G.; Yao, D.; Hu, Z. The spatial effect of the efficiency of regional financial resource allocation from the perspective of internet finance: Evidence from Chinese provinces. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade 2020, 56, 1211–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Hueng, C.J.; Hu, W. Measurement and spillover effect of digital financial inclusion: A cross-country analysis. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2021, 28, 1738–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joassart-Marcelli, P.; Stephens, P. Immigrant banking and financial exclusion in Greater Boston. J. Econ. Geogr. 2010, 10, 883–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, M.; Pais, J. Financial inclusion and development. J. Int. Dev. 2011, 23, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Bao, H. Transportation Infrastructure, Digital Economy and Trade Growth: A Research on the Regions along the New Western Land-Sea Route. Reform 2023, 06, 142–155. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- González, A.; Tersvirta, T.; Dijk, D.V. Panel Smooth Transition Regression Models. Res. Pap. 2005. Available online: https://mail.tku.edu.tw/niehcc/paper/GTD(2005-wp)PST-Hansen.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Bai, L.; Guo, T.; Xu, W.; Liu, Y.; Kuang, M.; Jiang, L. Effects of digital economy on carbon emission intensity in Chinese cities: A life-cycle theory and the application of non-linear spatial panel smooth transition threshold model. Energy Policy 2023, 183, 113792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidian, M.; Giltinan, D.M. Nonlinear models for repeated measurement data: An overview and update. J. Agric. Biol. Environ. Stat. 2003, 8, 387–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, S.; Xiang, J. Estimation of China’s urban fixed capital stock from 1996 to 2009. Stat. Res. 2012, 29, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, K.; Ma, R.; Du, L. Does digital inclusive finance affect the urban green economic efficiency? New evidence from the spatial econometric analysis of 284 cities in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 63435–63452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Tian, C.; Li, Y.; Song, H.; Ma, Z. Research on the effects of urbanization on carbon emissions efficiency of urban agglomerations in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 1374–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, W. The impact of digital inclusive finance on agricultural carbon emissions at the city level in China: The role of rural entrepreneurship and agricultural innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 505, 145469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Wang, J.; Wang, F.; Cheng, Z.; Kong, T.; Zhang, X. Measuring the development of China’s digital financial inclusion: Index compilation and spatial characteristics. Economics 2020, 19, 1401–1418. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, B. Understanding the green total factor energy efficiency gap between regional manufacturing—Insight from infrastructure development. Energy 2021, 237, 121553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lyu, Y. Toward inclusive green growth for sustainable development: A new perspective of labor market distortion. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2023, 32, 3927–3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Mao, W.; Dang, Y.; Luo, D. What inhibits regional inclusive green growth? Empirical evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 39790–39806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, D.; Zhou, J. Digital economy and carbon emission performance: Evidence at China’s city level. Energy Policy 2022, 165, 112927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Ang, B.W.; Wang, H. Energy and CO2 emission performance in electricity generation: A non-radial directional distance function approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 221, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Choi, Y. Total-factor carbon emission performance of fossil fuel power plants in China: A metafrontier non-radial Malmquist index analysis. Energy Econ. 2013, 40, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, H.; Weber, W.L. A directional slacks-based measure of technical efficiency. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2009, 43, 274–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.H. A global Malmquist-Luenberger productivity index. J. Prod. Anal. 2010, 34, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Du, K. The Energy Effect of Factor Market Distortion in China. Econ. Res. 2013, 48, 125–136. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bartik, T.J. How do the effects of local growth on employment rates vary with initial labor market conditions? Upjohn Inst. Work. Pap. 2009, 9–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Xu, D.; Zhong, R. How does the Development of Digital Finance Reduce CO2 Emissions?—Empirical Analysis Based on Prefecture-level Cities. Mod. Econ. Sci. 2023, 45, 15–28. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Escribano, A.; Jordá, O. Improved Testing and Specification of Smooth Transition Autoregressive Models. In Nonlinear Time Series Analysis of Economic and Financial Data; Rothman, P., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1999; pp. 289–319. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.J.; Teräsvirta, T. Testing the constancy of regression parameters against continuous structural change. J. Econometrics 1994, 62, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Lee, L. Estimating a spatial autoregressive model with an endogenous spatial weight matrix. J. Econom. 2015, 184, 209–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator Type | Variable | Indicator Description |

|---|---|---|

| Inputs | Capital stock (K) | Following Ke and Xiang (2012) [75], we estimate each city’s capital stock using the perpetual inventory method. |

| Labor force (L) | Number of employed people in prefecture-level cities at the end of the year [76]. | |

| Energy consumption (E) | Total energy consumption in each city [77]. | |

| Desirable output | Gross domestic product(Y) | Using 2011 constant prices, we deflate each city’s nominal gross domestic product (GDP) with the corresponding GDP deflator to obtain real GDP for every year [4]. |

| Undesirable output | CO2 emissions (C) | City-level CO2 emissions are sourced from the Emission Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR). The EDGAR provides a comprehensive time series dataset of China’s greenhouse gas emissions, which includes a time-series grid map depicting urban carbon-dioxide emissions, with a spatial resolution of 0.1 deg × 0.1 deg [78]. |

| Obs. | Mean | Std. | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEE | 1056 | 0.3356 | 0.1823 | 0.0684 | 1.0000 |

| DF | 1056 | 1.8481 | 0.7347 | 0.1702 | 3.2040 |

| COB | 1056 | 1.7971 | 0.7992 | 0.0186 | 3.5329 |

| USD | 1056 | 1.7076 | 0.6854 | 0.0429 | 2.9978 |

| DIL | 1056 | 2.2719 | 0.7867 | 0.0339 | 5.8123 |

| TIN | 1056 | 0.0818 | 0.0982 | 0.0040 | 0.6744 |

| INF | 1056 | 0.2452 | 0.2067 | 0.0266 | 3.1636 |

| lnRGDP | 1056 | 10.5797 | 0.6373 | 8.7729 | 12.4572 |

| FSTE | 1056 | 0.1871 | 0.0380 | 0.0526 | 0.3312 |

| FD | 1056 | 0.3425 | 0.1913 | 0.0506 | 0.9627 |

| STRU | 1056 | 1.1310 | 0.7305 | 0.1136 | 5.4192 |

| ER | 1056 | 1.2226 | 1.2928 | 0.0207 | 16.9312 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF | −0.476 *** | −0.467 *** | |||

| (−6.314) | (−5.952) | ||||

| DF2 | 0.064 *** | 0.058 *** | |||

| (5.376) | (4.444) | ||||

| COB | −0.349 *** | ||||

| (−6.036) | |||||

| COB2 | 0.039 *** | ||||

| (4.574) | |||||

| USD | 0.121 ** | ||||

| (2.231) | |||||

| USD2 | 0.003 | ||||

| (0.208) | |||||

| DIL | −0.093 *** | ||||

| (−2.808) | |||||

| DIL2 | 0.009 | ||||

| (1.392) | |||||

| lnRGDP | 0.048 * | 0.061 ** | 0.005 | −0.005 | |

| (1.721) | (2.122) | (0.195) | (−0.178) | ||

| FSTE | 0.810 *** | 0.875 *** | 0.912 *** | 0.861 *** | |

| (5.786) | (6.199) | (6.487) | (6.165) | ||

| FD | −0.121 ** | −0.121 ** | −0.094 | −0.098 | |

| (−2.030) | (−2.032) | (−1.558) | (−1.637) | ||

| STRU | −0.038 *** | −0.034 *** | −0.042 *** | −0.044 *** | |

| (−3.488) | (−3.176) | (−3.843) | (−4.029) | ||

| ER | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.000 | −0.002 | |

| (−0.315) | (0.274) | (−0.004) | (−0.637) | ||

| Constant | 0.964 *** | 0.388 | 0.082 | −0.026 | 0.469 * |

| (8.604) | (1.314) | (0.276) | (−0.088) | (1.704) | |

| City FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 1056 | 1056 | 1056 | 1056 | 1056 |

| R2 | 0.780 | 0.791 | 0.791 | 0.786 | 0.787 |

| Adj_R2 | 0.756 | 0.767 | 0.768 | 0.762 | 0.764 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L.CEE | 0.561 *** | 0.788 *** | |||

| (4.495) | (11.875) | ||||

| L.DF | −0.441 *** | ||||

| (−6.257) | |||||

| L.DF2 | 0.080 *** | ||||

| (6.438) | |||||

| DF | −0.467 *** | −1.931 ** | −0.223 ** | −0.237 ** | |

| (−5.953) | (−2.581) | (−2.065) | (−2.463) | ||

| DF2 | 0.058 *** | 0.113 *** | 0.084 *** | 0.073 *** | |

| (4.445) | (4.039) | (2.655) | (3.232) | ||

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| City FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Anderson LM | 136.869 | 9.508 | |||

| (p-val) | (0.000) | (0.002) | |||

| Cragg–Donald Wald F | 1.0 × 109 | 34.280 | |||

| 10% maximal IV size | 7.03 | 7.03 | |||

| AR(1) | 0.005 | 0.002 | |||

| AR(2) | 0.142 | 0.148 | |||

| Sargan | 0.328 | 0.353 | |||

| N | 968 | 1056 | 968 | 968 | 968 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF | −0.515 *** | −0.188 *** | −0.561 *** | |

| (−6.421) | (−4.603) | (−6.128) | ||

| DF2 | 0.063 *** | 0.056 *** | 0.080 *** | |

| (4.599) | (4.788) | (4.385) | ||

| FT | −0.102 *** | |||

| (−3.206) | ||||

| FT2 | 0.010 ** | |||

| (2.544) | ||||

| Constant | 0.425 | 0.284 | −0.297 | 0.389 |

| (1.450) | (1.037) | (−1.044) | (1.121) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| City FE | YES | YES | NO | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | NO | YES |

| N | 1056 | 1056 | 1056 | 1056 |

| R2 | 0.791 | 0.785 | 0.770 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | Central | South | 2011–2016 | 2017–2022 | |

| DF | −0.629 *** | −0.784 *** | −0.073 | 0.057 | −2.045 *** |

| (−4.104) | (−4.991) | (−0.590) | (0.258) | (−4.879) | |

| DF2 | 0.082 *** | 0.105 *** | 0.010 | −0.062 | 0.324 *** |

| (2.896) | (3.900) | (0.576) | (−1.382) | (4.264) | |

| Constant | −0.913 | 0.211 | 0.638 | −0.370 | 1.832 *** |

| (−1.635) | (0.359) | (1.586) | (−0.697) | (3.063) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| City FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 312 | 372 | 372 | 528 | 528 |

| R2 | 0.259 | 0.256 | 0.129 | 0.125 | 0.297 |

| Q10 | Q25 | Q50 | Q75 | Q90 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF | 0.108 *** | 0.097 *** | −0.033 | −0.286 *** | −0.687 *** |

| (4.369) | (4.401) | (−1.089) | (−5.538) | (−4.020) | |

| DF2 | −0.024 *** | −0.013 ** | 0.022 *** | 0.081 *** | 0.170 *** |

| (−3.879) | (−2.358) | (2.668) | (6.349) | (4.526) | |

| Constant | 1.005 *** | 1.287 *** | 0.500 | −0.399 | −3.744 ** |

| (3.307) | (4.367) | (1.468) | (−0.715) | (−2.208) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| City FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 1056 | 1056 | 1056 | 1056 | 1056 |

| R2 | 0.055 | 0.054 | 0.053 | 0.086 | 0.099 |

| Test | Moran’s I | SEM | SAR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LM(Error) | R-LM(Error) | LM(Lag) | R-LM(Lag) | ||

| Statistical value | 11.513 | 125.492 | 0.964 | 134.610 | 10.083 |

| (p-value) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.326) | (0.000) | (0.001) |

| Test | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer Variable (TIN) | Transfer Variable (INF) | |||

| Statistics | p-Value | Statistics | p-Value | |

| Linearity test | ||||

| 4.397 | 0.004 | 22.760 | 0.000 | |

| 2.454 | 0.023 | 12.219 | 0.000 | |

| 2.236 | 0.018 | 9.706 | 0.000 | |

| 2.263 | 0.008 | 8.555 | 0.000 | |

| Residual linearity test | ||||

| 2.996 | 0.050 | 0.045 | 0.957 | |

| 1.525 | 0.193 | 0.696 | 0.595 | |

| 1.643 | 0.132 | 1.524 | 0.167 | |

| 1.417 | 0.185 | 2.654 | 0.007 | |

| Test | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer Variable (TIN) | Transfer Variable (INF) | |||

| Statistics | p-Value | Statistics | p-Value | |

| Escribano–Jorda linearity test | ||||

| (HoL) | 2.592 | 0.017 | 4.385 | 0.002 |

| (HoE) | 2.164 | 0.044 | 4.700 | 0.001 |

| Teräsvirta sequential test | ||||

| 4.397 | 0.004 | 0.045 | 0.957 | |

| 0.517 | 0.671 | 3.175 | 0.042 | |

| 1.790 | 0.786 | 1.347 | 0.261 | |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer Variable (TIN) | Transfer Variable (INF) | Transfer Variable (TIN) | Transfer Variable (INF) | |||||

| / | / | / | / | |||||

| DF | −0.420 *** | 0.335 *** | −0.372 *** | 0.367 *** | −0.264 *** | 0.147 * | −0.280 *** | 0.321 *** |

| (−7.236) | (4.240) | (−6.633) | (3.449) | (−3.477) | (1.790) | (−4.776) | (3.366) | |

| W × DF | 0.425 *** | −0.316 *** | 0.356 *** | −0.333 *** | 0.390 *** | −0.179 ** | 0.327 *** | −0.274 *** |

| (7.359) | (−4.054) | (6.373) | (−3.215) | (5.378) | (−1.961) | (5.651) | (−2.926) | |

| 0.448 *** | 0.352 *** | 0.912 *** | 0.698 ** | |||||

| (9.204) | (6.976) | (3.256) | (2.494) | |||||

| γ | 5.659 *** | 2.528 *** | 5.604 *** | 2.561 *** | ||||

| (5.053) | (4.987) | (2.801) | (6.413) | |||||

| c | 0.635 *** | 0.212 *** | 0.375 *** | 0.212 *** | ||||

| (129.464) | (8.977) | (29.308) | (9.189) | |||||

| N | 1056 | 1056 | 1056 | 1056 | ||||

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer Variable (TIN) | Transfer Variable (INF) | Transfer Variable (TIN) | Transfer Variable (INF) | |||||

| / | / | / | / | |||||

| DF | −0.496 *** | 0.337 *** | −0.474 *** | 0.540 *** | ||||

| (−6.068) | (3.146) | (−7.069) | (4.898) | |||||

| W × DF | 0.521 *** | −0.366 *** | 0.448 *** | −0.503 *** | ||||

| (6.413) | (−3.458) | (6.717) | (−4.676) | |||||

| FT | −0.112 ** | 0.127 ** | −0.506 * | 0.517 * | ||||

| (−2.206) | (2.399) | (−1.778) | (1.826) | |||||

| W × FT | 0.086 * | −0.165 *** | 0.173 * | −0.167 * | ||||

| (1.860) | (−3.360) | (1.699) | (−1.781) | |||||

| 0.511 *** | 0.408 *** | 0.347 *** | 0.315 *** | |||||

| (8.050) | (6.275) | (6.800) | (6.166) | |||||

| γ | 5.097 *** | 2.959 *** | 4.147 *** | 4.010 *** | ||||

| (3.859) | (6.754) | (2.760) | (6.490) | |||||

| c | 0.370 *** | 0.192 *** | 1.229 *** | 0.070 *** | ||||

| (32.943) | (10.290) | (29.829) | (5.717) | |||||

| N | 900 | 900 | 1056 | 1056 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, M.; Hu, X.; Xie, Y. Digital Finance, Regional Infrastructure, and Urban Carbon-Emission Efficiency: A Spatial Nonlinear Analysis Based on the New Western Land–Sea Corridor. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11071. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411071

Zhang M, Hu X, Xie Y. Digital Finance, Regional Infrastructure, and Urban Carbon-Emission Efficiency: A Spatial Nonlinear Analysis Based on the New Western Land–Sea Corridor. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11071. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411071

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Minglong, Xia Hu, and Ying Xie. 2025. "Digital Finance, Regional Infrastructure, and Urban Carbon-Emission Efficiency: A Spatial Nonlinear Analysis Based on the New Western Land–Sea Corridor" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11071. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411071

APA StyleZhang, M., Hu, X., & Xie, Y. (2025). Digital Finance, Regional Infrastructure, and Urban Carbon-Emission Efficiency: A Spatial Nonlinear Analysis Based on the New Western Land–Sea Corridor. Sustainability, 17(24), 11071. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411071