Temporal Variability of Arsenic in the Caplina Aquifer, La Yarada Los Palos, Peru: Implications for Risk-Based Drinking Water Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

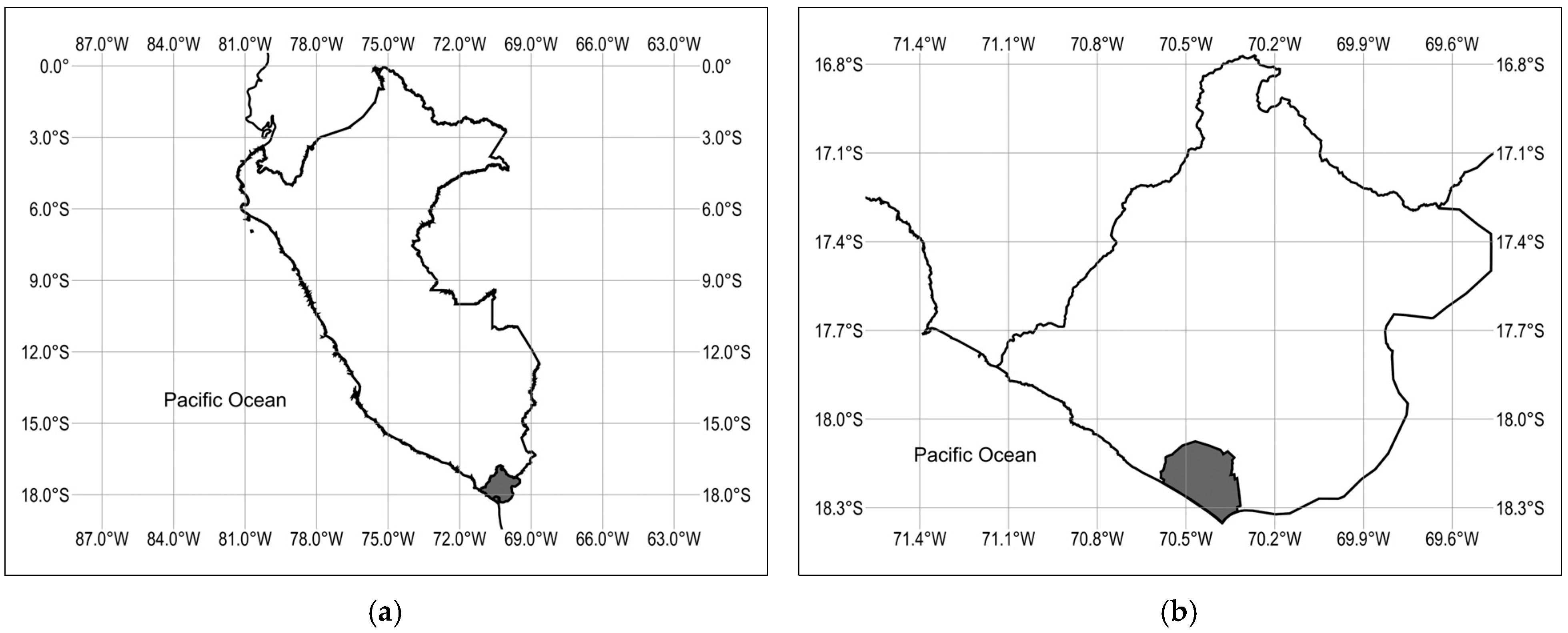

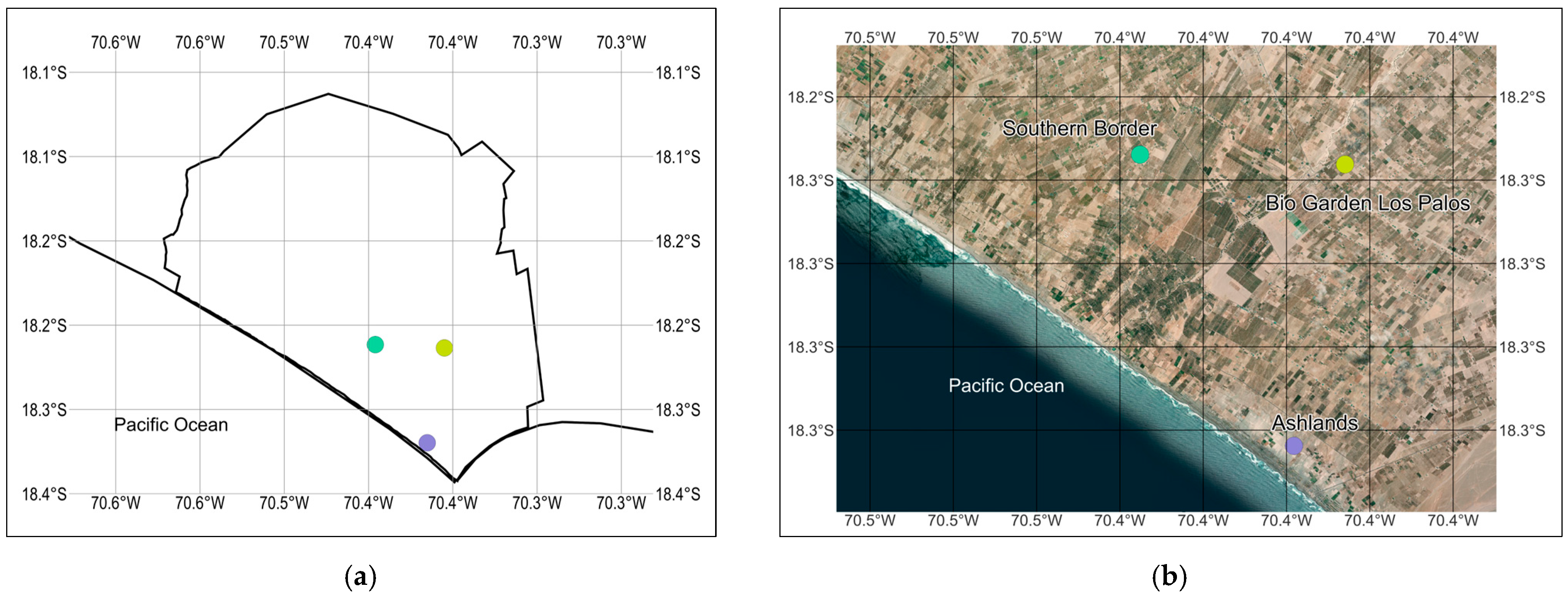

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling Design

2.3. In Situ Measurement

2.4. Sampling, Preservation, and Analysis of As

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. Temporal Variability

- -

- : arsenic concentration (µg/L) at visit ;

- -

- : number of visits per point (24);

- -

- : mean;

- -

- : sample standard deviation;

- -

- : 25th and 75th percentiles;

- -

- : median of the absolute changes between consecutive visits; summarizes the typical fortnightly oscillation and provides information about the risk of missing transient peaks;

- -

- The median of is computed ignoring missing values and retains the measurement units (µg/L).

2.5.2. Exceedances of the Health-Based Threshold (10 µg/L)

- -

- : is the indicator function (=1 if the condition holds; 0 otherwise);

- -

- is the proportion of measurements with As > 10 µg/L; the Wilson method performs well with moderate n and proportions near 0 or 1 [62].

2.5.3. Correlation Analysis with In Situ Variables

- -

- : As (µg/L); : EC, TDS, pH, or temperature (evaluated at each point);

- -

- : Spearman’s coefficient; ρₛ and its p-value are reported (two-sided test, with α = 0.05);

2.5.4. Sampling Schemes and Compliance Assessment

- where

- -

- : sampling scheme (day 1, day 15, fortnightly);

- -

- : set of observation indices included under scheme (used in the formulas above);

- -

- : annual non-compliance indicator (=1 if under scheme there is any measurement > 10 µg/L);

- -

- : change in status relative to the fortnightly reference (0 = agrees; 1 = misclassifies);

- -

- : exceedance proportion under scheme ;

- -

- : fraction of exceedance episodes captured by the monthly scheme relative to those observed with the fortnightly reference.

3. Results

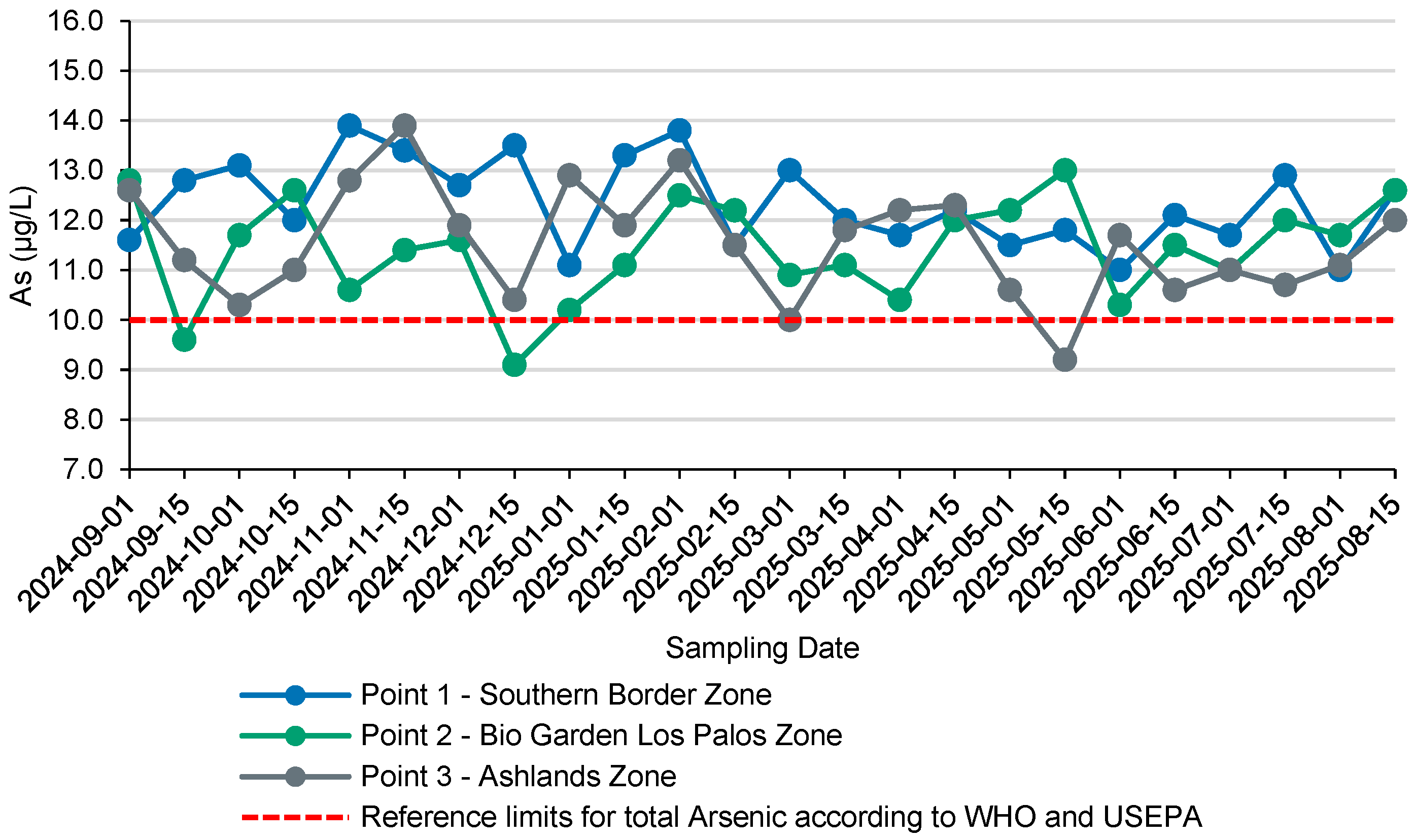

3.1. Overall As Concentrations and Comparison with the 10 µg/L Threshold

3.2. Intra-Annual Variability of As: Point-Wise Descriptive Statistics

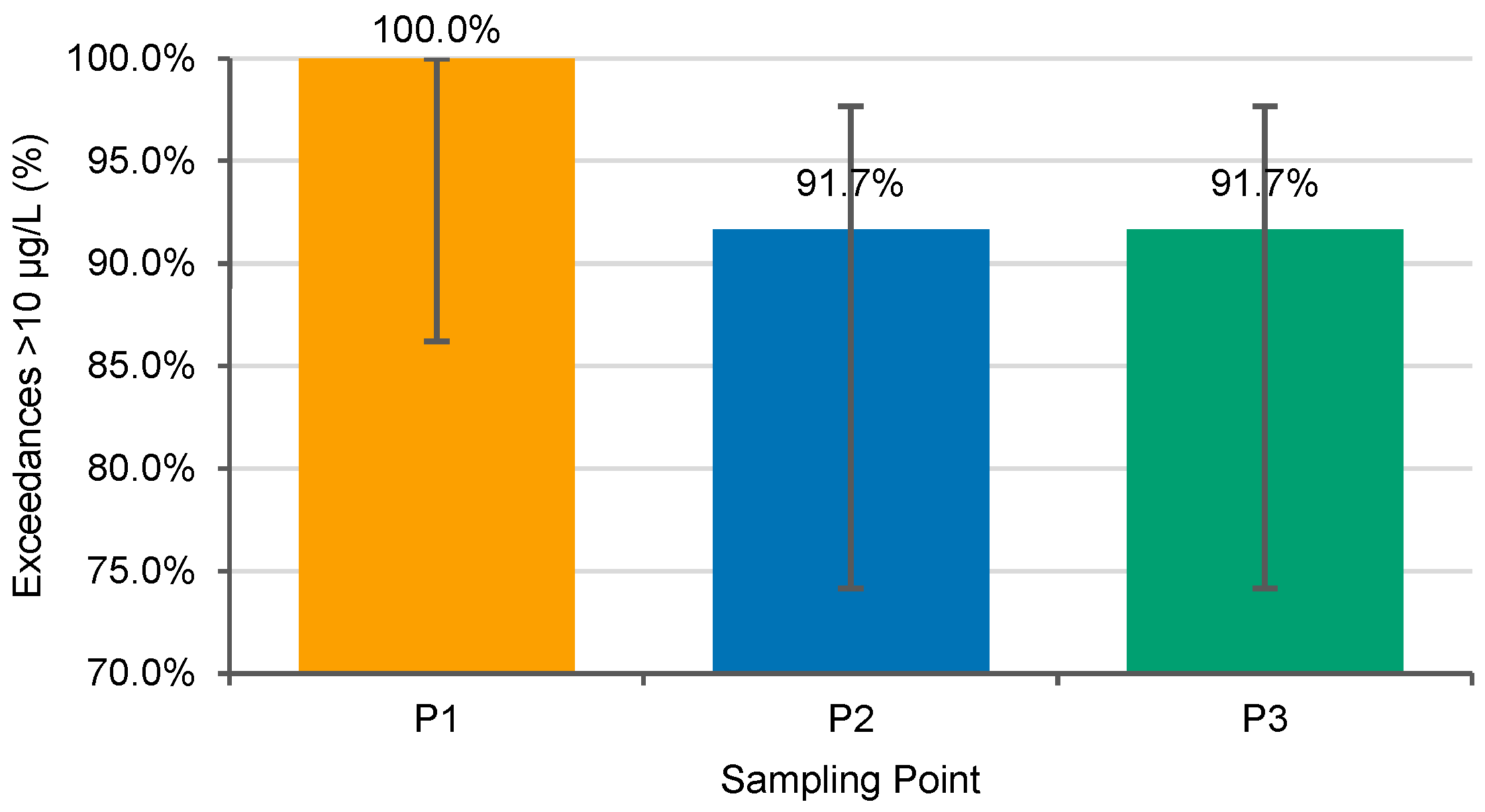

3.3. Exceedances of the 10 µg/L Health-Based Threshold

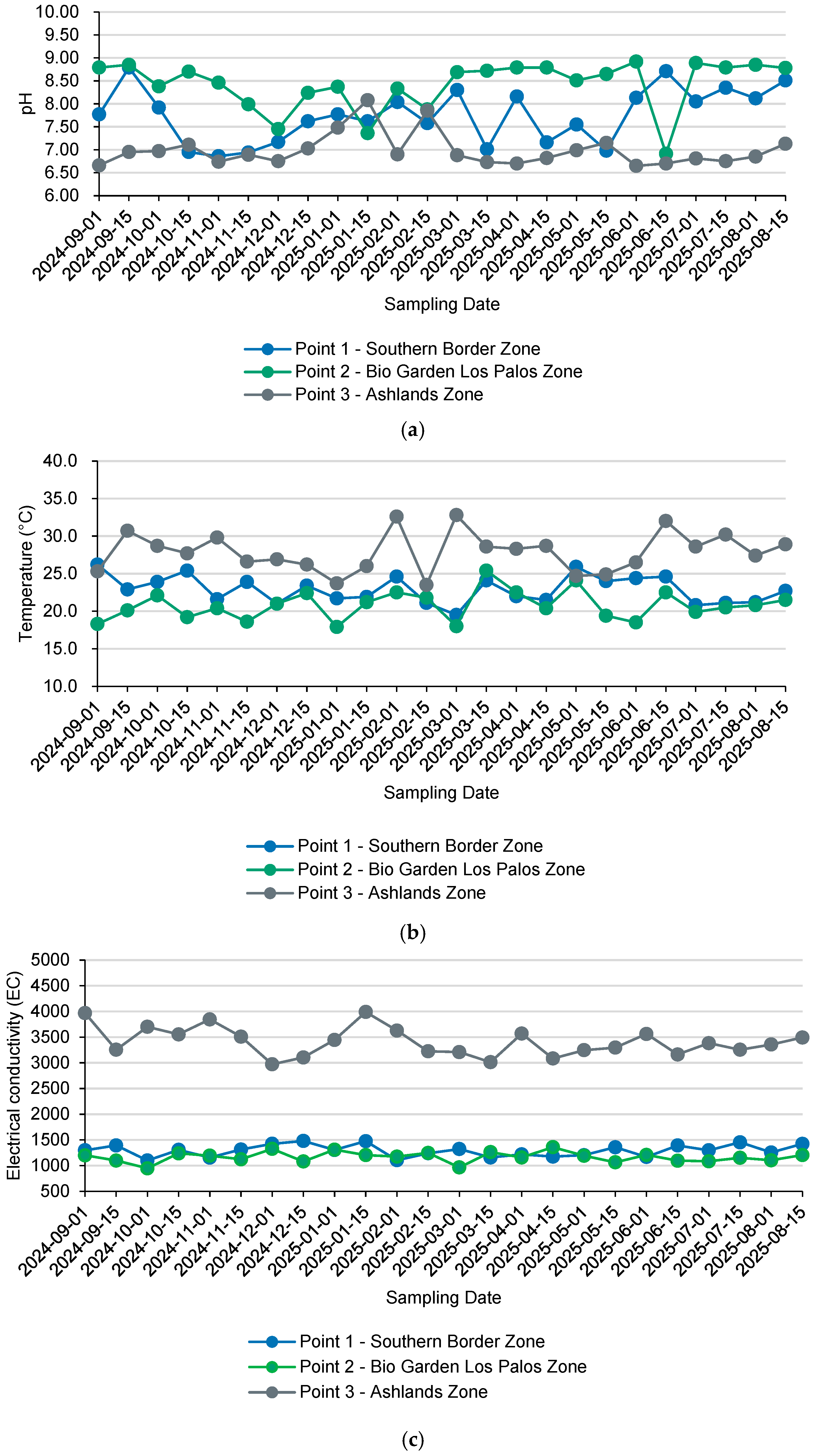

3.4. Operational Associations with In Situ Variables

3.5. Exceedance Frequency of the 10 µg/L Threshold by Point and Semester

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings and Magnitude of Fluctuations

4.2. Hydrogeochemical Drivers of Arsenic Variability

4.3. Implications for Monitoring and Risk Management

4.4. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mukherjee, A.; Coomar, P.; Sarkar, S.; Johannesson, K.H.; Fryar, A.E.; Schreiber, M.E.; Ahmed, K.M.; Alam, M.A.; Bhattacharya, P.; Bundschuh, J.; et al. Arsenic and Other Geogenic Contaminants in Global Groundwater. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Arsenic. Fact Sheet; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (Ed.) Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality; Fourth edition incorporating the first and second addenda; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-92-4-004506-4. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Arsenic in Drinking-Water: Background Document for Development of WHO Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Genchi, G.; Lauria, G.; Catalano, A.; Carocci, A.; Sinicropi, M.S. Arsenic: A Review on a Great Health Issue Worldwide. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, M.A.; Daniel, J.; Jeddy, Z.; Hay, L.E.; Ayotte, J.D. Assessing the Impact of Drought on Arsenic Exposure from Private Domestic Wells in the Conterminous United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 1822–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, P.U.; Heuzard, A.G.; Le, T.X.H.; Zhao, J.; Yin, R.; Shang, C.; Fan, C. The Impacts of Climate Change on Groundwater Quality: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundschuh, J.; Armienta, M.A.; Morales-Simfors, N.; Alam, M.A.; López, D.L.; Delgado Quezada, V.; Dietrich, S.; Schneider, J.; Tapia, J.; Sracek, O.; et al. Arsenic in Latin America: New Findings on Source, Mobilization and Mobility in Human Environments in 20 Countries Based on Decadal Research 2010–2020. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 51, 1727–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, F.C.R.; Moreira, V.R.; Guimarães, R.N.; Moser, P.B.; Amaral, M.C.S. Arsenic in Natural Waters of Latin-American Countries: Occurrence, Risk Assessment, Low-Cost Methods, and Technologies for Remediation. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 184, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.P.; Jia, Y.F.; Guo, H.M.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, B. Quantifying Geochemical Processes of Arsenic Mobility in Groundwater From an Inland Basin Using a Reactive Transport Model. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR025492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgorski, J.; Berg, M. Global Threat of Arsenic in Groundwater. Science 2020, 368, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanel, S.R.; Das, T.K.; Varma, R.S.; Kurwadkar, S.; Chakraborty, S.; Joshi, T.P.; Bezbaruah, A.N.; Nadagouda, M.N. Arsenic Contamination in Groundwater: Geochemical Basis of Treatment Technologies. ACS Environ. Au 2023, 3, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaji, E.; Santosh, M.; Sarath, K.V.; Prakash, P.; Deepchand, V.; Divya, B.V. Arsenic Contamination of Groundwater: A Global Synopsis with Focus on the Indian Peninsula. Geosci. Front. 2021, 12, 101079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, M.W.; Qureshi, F.; Ahmed, S.; Kamyab, H.; Rajendran, S.; Ibrahim, H.; Yusuf, M. A Comprehensive Review on Arsenic Contamination in Groundwater: Sources, Detection, Mitigation Strategies and Cost Analysis. Environ. Res. 2025, 265, 120457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, W.H.; Klein, E.M.; Vengosh, A. The Global Biogeochemical Cycle of Arsenic. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2022, 36, e2022GB007515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, A.; Pino-Vargas, E.; Verma, M.P.; Chucuya, S.; Chávarri, E.; Canales, M.; Torres-Martínez, J.A.; Mora, A.; Mahlknecht, J. Hydrodynamics, Hydrochemistry, and Stable Isotope Geochemistry to Assess Temporal Behavior of Seawater Intrusion in the La Yarada Aquifer in the Vicinity of Atacama Desert, Tacna, Peru. Water 2021, 13, 3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autoridad Nacional del Agua; Consejo de Recursos Hídricos de la Cuenca Caplina–Locumba. Plan de Gestión de Recursos Hídricos de la Cuenca Caplina–Locumba, Actualizado al 2023; Autoridad Nacional del Agua: Lima, Peru, 2023; Available online: https://repositorio.ana.gob.pe/handle/20.500.12543/5652 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- González-Domínguez, J.; Mora, A.; Chucuya, S.; Pino-Vargas, E.; Torres-Martínez, J.A.; Dueñas-Moreno, J.; Ramos-Fernández, L.; Kumar, M.; Mahlknecht, J. Hydraulic Recharge and Element Dynamics during Salinization in an Overexploited Coastal Aquifer of the World’s Driest Zone: Atacama Desert. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, E.; Alvarez, V.; Gonzales, K. Two Decades of Groundwater Variability in Peru Using Satellite Gravimetry Data. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fano-Sizgorich, D.; Gribble, M.O.; Vásquez-Velásquez, C.; Ramírez-Atencio, C.; Aguilar, J.; Wickliffe, J.K.; Lichtveld, M.Y.; Barr, D.B.; Gonzales, G.F. Urinary Arsenic Species and Birth Outcomes in Tacna, Peru, 2019: A Prospective Cohort Study. UCL Open Environ. 2024, 6, e3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chucuya, S.; Vera, A.; Pino-Vargas, E.; Steenken, A.; Mahlknecht, J.; Montalván, I. Hydrogeochemical Characterization and Identification of Factors Influencing Groundwater Quality in Coastal Aquifers, Case: La Yarada, Tacna, Peru. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fano, D.; Vásquez-Velásquez, C.; Aguilar, J.; Gribble, M.O.; Wickliffe, J.K.; Lichtveld, M.Y.; Steenland, K.; Gonzales, G.F. Arsenic Concentrations in Household Drinking Water: A Cross-Sectional Survey of Pregnant Women in Tacna, Peru, 2019. Expo Health 2020, 12, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MINAM. Decreto Supremo No. 004-2017-MINAM: Estándares de Calidad Ambiental (ECA) para Agua; El Peruano: Lima, Peru, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gopang, M.; Yazdi, M.D.; Moyer, A.; Smith, D.M.; Meliker, J.R. Low-to-Moderate Arsenic Exposure: A Global Systematic Review of Cardiovascular Disease Risks. Environ. Health 2025, 24, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigra, A.E.; Moon, K.A.; Jones, M.R.; Sanchez, T.R.; Navas-Acien, A. Urinary Arsenic and Heart Disease Mortality in NHANES 2003–2014. Environ. Res. 2021, 200, 111387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, K.A.; Oberoi, S.; Barchowsky, A.; Chen, Y.; Guallar, E.; Nachman, K.E.; Rahman, M.; Sohel, N.; D’Ippoliti, D.; Wade, T.J.; et al. A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Chronic Arsenic Exposure and Incident Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1924–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issanov, A.; Adewusi, B.; Saint-Jacques, N.; Dummer, T.J.B. Arsenic in Drinking Water and Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review of 35 Years of Evidence. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2024, 483, 116808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issanov, A.; Adewusi, B.; Dummer, T.J.B.; Saint-Jacques, N. Arsenic in Drinking Water and Urinary Tract Cancers: A Systematic Review Update. Water 2023, 15, 2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notario-Barandiaran, L.; Compañ-Gabucio, L.M.; Bauer, J.A.; Vioque, J.; Karagas, M.R.; Signes-Pastor, A.J. Arsenic Exposure and Neuropsychological Outcomes in Children: A Scoping Review. Toxics 2025, 13, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Qu, J. Review on Heterogeneous Oxidation and Adsorption for Arsenic Removal from Drinking Water. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 110, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demissie, S.; Mekonen, S.; Awoke, T.; Mengistie, B. Assessing Acute and Chronic Risks of Human Exposure to Arsenic: A Cross-Sectional Study in Ethiopia Employing Body Biomarkers. Environ. Health Insights 2024, 18, 11786302241257365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, L.; Stearns, D.; Daniel, J.; Tomazin, R.; Harvey, D.; Williams, T.; Peterson-Wright, L.; Strosnider, H.; Freedman, M.; Yip, F. Changes in Exposure to Arsenic Following the Installation of an Arsenic Removal Treatment in a Small Community Water System. Water 2025, 17, 1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahidul Hassan, H. A Review on Different Arsenic Removal Techniques Used for Decontamination of Drinking Water. Environ. Pollut. Bioavailab. 2023, 35, 2165964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraaijeveld, E.; Rijsdijk, S.; Van Der Poel, S.; Van Der Hoek, J.P.; Rabaey, K.; Van Halem, D. Electrochemical Arsenite Oxidation for Drinking Water Treatment: Mechanisms, by-Product Formation and Energy Consumption. Water Res. 2024, 253, 121227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALSamman, M.T.; Sotelo, S.; Sánchez, J.; Rivas, B.L. Arsenic Oxidation and Its Subsequent Removal from Water: An Overview. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 309, 123055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neisan, R.S.; Saady, N.M.C.; Bazan, C.; Zendehboudi, S.; Al-nayili, A.; Abbassi, B.; Chatterjee, P. Arsenic Removal by Adsorbents from Water for Small Communities’ Decentralized Systems: Performance, Characterization, and Effective Parameters. Clean Technol. 2023, 5, 352–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Nguyen, T.V.; Vigneswaran, S.; Ha, N.T.H.; Ratnaweera, H. A Review of Theoretical Knowledge and Practical Applications of Iron-Based Adsorbents for Removing Arsenic from Water. Minerals 2023, 13, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Zeng, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhao, W.; Han, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, D. Selective Adsorption of Arsenic by Water Treatment Residuals Cross-Linked Chitosan in Co-Existing Oxyanions Competition System. Environ. Res. 2024, 263, 120192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojiri, A.; Razmi, E.; KarimiDermani, B.; Rezania, S.; Kasmuri, N.; Vakili, M.; Farraji, H. Adsorption Methods for Arsenic Removal in Water Bodies: A Critical Evaluation of Effectiveness and Limitations. Front. Water 2024, 6, 1301648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, M.; Ruffner, B.A. Field Study of an Arsenic Removal Plant for Drinking Water Using Activated Carbon and Iron in a Rural Community in the Province of Pisco, Peru. J. Water Health 2024, 22, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.K.; Yadav, H.K.; Naz, A.; Koul, M.; Chowdhury, A.; Shekhar, S. Arsenic Removal Technologies for Middle- and Low-Income Countries to Achieve the SDG-3 and SDG-6 Targets: A Review. Environ. Adv. 2022, 9, 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Igwegbe, C.A.; Malloum, A.; Elmakki, M.A.E.; Onyeaka, H.; Fahmy, A.H.; Aquatar, M.O.; Ahmadi, S.; Alameri, B.M.; Ghosh, S.; et al. Sustainable Technologies for Removal of Arsenic from Water and Wastewater: A Comprehensive Review. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 427, 127412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayotte, J.D.; Belaval, M.; Olson, S.A.; Burow, K.R.; Flanagan, S.M.; Hinkle, S.R.; Lindsey, B.D. Factors Affecting Temporal Variability of Arsenic in Groundwater Used for Drinking Water Supply in the United States. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 505, 1370–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Geological Survey. Rapid Fluctuations in Groundwater Quality—Featured Study: Temporal Variability of Arsenic in Groundwater. USGS Water Resources. 2019. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/mission-areas/water-resources/science/rapid-fluctuations-groundwater-quality (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Yin, S.; Yang, L.; Wen, Q.; Wei, B. Temporal Variation and Mechanism of the Geogenic Arsenic Concentrations in Global Groundwater. Appl. Geochem. 2022, 146, 105475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-W.; Yan, Y.-N.; Zhao, Z.-Q.; Li, X.-D.; Guo, J.-Y.; Ding, H.; Cui, L.-F.; Meng, J.-L.; Liu, C.-Q. Spatial and Seasonal Variations of Dissolved Arsenic in the Yarlung Tsangpo River, Southern Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 760, 143416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, E.V. El Acuífero Costero La Yarada, Después de 100 Años de Explotación Como Sustento de Una Agricultura En Zonas Áridas: Una Revisión Histórica. Idesia 2019, 37, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori Sosa, L.J.P. Efficiency Evaluation of a Photovoltaic-Powered Water Treatment System with Natural Sedimentation Pretreatment for Arsenic Removal in High Water Vulnerability Areas: Application in La Yarada Los Palos District, Tacna, Peru. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, E.V.; Coarita, F.A. Caracterización Hidrogeológica Para Determinar El Deterioro de La Calidad Del Agua En El Acuífero La Yarada Media. Rev. Investig. Altoandinas 2018, 20, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno Regional de Tacna. Proyecto Especial “Afianzamiento y Ampliación de los Recursos Hídricos de Tacna” (PET) Programa de Distribución de Agua del Sector Hidráulico Mayor Uchusuma Caplina—Clase B: Periodo Agosto 2024–Julio 2025; Anexo 80 de la Resolución Directoral No. 1041-2024-ANA-AAA.CO.; Gobierno Regional de Tacna—Proyecto Especial (PET): Tacna, Perú, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Degnan, J.R.; Levitt, J.P.; Erickson, M.L.; Jurgens, B.C.; Lindsey, B.D.; Ayotte, J.D. Time Scales of Arsenic Variability and the Role of High-Frequency Monitoring at Three Water-Supply Wells in New Hampshire, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 709, 135946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ANA. Protocolo Nacional Para el Monitoreo de la Calidad de los Recursos Hídricos Superficiales; Autoridad Nacional del Agua (ANA): Lima, Perú, 2016.

- U.S. Geological Survey. National Field Manual for the Collection of Water-Quality Data: U.S. Geological Survey Techniques of Water-Resources Investigations; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2015; Book 9.

- Ministerio del Ambiente (MINAM). Manual de Buenas Prácticas en la Investigación de Sitios Contaminados: Muestreo de Aguas Subterráneas; Ministerio del Ambiente: Lima, Perú, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 5667-3:2024; Water Quality—Sampling; Preservation and Handling of Water Samples; Revision Underway. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; ISBN 978-0-539-22390-3.

- ISO 17294-2:2016; Water Quality—Application of Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS); Determination of Selected Elements Including Uranium Isotopes; Withdrawn. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-0-580-82291-9.

- Creed, J.T.; Brockhoff, C.A.; Martin, T.D. Method 200.8, Revision 5.4: Determination of Trace Elements in Waters and Wastes by Inductively Coupled Plasma–Mass Spectrometry; Methods for the Determination of Metals in Environmental Samples—Supplement I; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1994.

- ASTM D516-22; Test Method for Sulfate Ion in Water. D19 Committee ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D888-18 D19; Test Methods for Dissolved Oxygen in Water. Committee ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Mori Sosa, L.J.P.; Morales Cabrera, D.U.; Florez Ponce De León, W.D.; Hinojosa Ramos, E.A.; Torres Ventura, A.Y. Study of Arsenic Contamination in the Caplina Basin, Tacna, Peru: Arsenite and Arsenate Analysis Using Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. Sustainability 2025, 17, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, C.; Little, R.J.A.; Louis, T.A.; Slud, E.V. Comparative Study of Confidence Intervals for Proportions in Complex Sample Surveys. J. Surv. Stat. Methodol. 2019, 7, 334–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, J.P.; Degnan, J.R.; Flanagan, S.M.; Jurgens, B.C. Arsenic Variability and Groundwater Age in Three Water Supply Wells in Southeast New Hampshire. Geosci. Front. 2019, 10, 1669–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.R.; Uddin, A.; Lee, M.-K.; Nelson, J.; Zahid, A.; Haque, M.M.; Sakib, N. Geochemistry of Arsenic and Salinity-Contaminated Groundwater and Mineralogy of Sediments in the Coastal Aquifers of Southwest Bangladesh. Water 2024, 16, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, P.M.; Hicks, E.C.; Levitt, J.P.; Lloyd, D.C.; McDonald, M.M.; Romanok, K.M.; Smalling, K.L.; Ayotte, J.D. A Brief Note on Substantial Sub-Daily Arsenic Variability in Pumping Drinking-Water Wells in New Hampshire. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 919, 170838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailloux, B.J.; Procopio, N.A.; Bakker, M.; Chen, T.; Choudhury, I.; Ahmed, K.M.; Mozumder, M.R.H.; Ellis, T.; Chillrud, S.; Van Geen, A. Recommended Sampling Intervals for Arsenic in Private Wells. Groundwater 2021, 59, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiberg, C.; Sjöstedt, C.; Eriksson, A.K.; Klysubun, W.; Gustafsson, J.P. Phosphate Competition with Arsenate on Poorly Crystalline Iron and Aluminum (Hydr)Oxide Mixtures. Chemosphere 2020, 255, 126937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Ren, Y.; Dong, Q.; Li, Z.; Xiao, S. Enrichment of High Arsenic Groundwater Controlled by Hydrogeochemical and Physical Processes in the Hetao Basin, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-Y.; Guo, H.-M.; Xiu, W.; Bauer, J.; Sun, G.-X.; Tang, X.-H.; Norra, S. Indications That Weathering of Evaporite Minerals Affects Groundwater Salinity and As Mobilization in Aquifers of the Northwestern Hetao Basin, China. Appl. Geochem 2019, 109, 104416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, K.S.; Hwang, H.-K.; Choi, H. Adsorptive Removal of Arsenic by Mesoporous Iron Oxide in Aquatic Systems. Water 2020, 12, 3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, I.; Prommer, H.; Berg, M.; Siade, A.J.; Sun, J.; Kipfer, R. The River–Groundwater Interface as a Hotspot for Arsenic Release. Nat. Geosci. 2020, 13, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.; Knight, R.; Fendorf, S. Overpumping Leads to California Groundwater Arsenic Threat. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisbie, S.H.; Mitchell, E.J.; Molla, A.R. Sea Level Rise from Climate Change Is Expected to Increase the Release of Arsenic into Bangladesh’s Drinking Well Water by Reduction and by the Salt Effect. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0295172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, O.; Burke, K. Binomial Confidence Intervals for Rare Events: Importance of Defining Margin of Error Relative to Magnitude of Proportion. Am. Stat. 2024, 78, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zweel, K.N.; Gourdol, L.; Iffly, J.F.; Léonard, L.; Barnich, F.; Pfister, L.; Zehe, E.; Hissler, C. One Year of High-Frequency Monitoring of Groundwater Physico-Chemical Parameters in the Weierbach Experimental Catchment, Luxembourg. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 2217–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, S.; Mishra, S.; Kumar, V.; Agnihotri, R.; Sharma, P.; Tiwari, R.K.; Gupta, A.; Singh, A.P.; Kumar, S.; Sinam, G. A Comprehensive Review on Spatial and Temporal Variation of Arsenic Contamination in Ghaghara Basin and Its Relation to Probable Incremental Life Time Cancer Risk in the Local Population. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2023, 80, 127308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, B.J.; Gains-Germain, L.; Broms, K.; Black, K.; Furman, M.; Hays, M.D.; Thomas, K.W.; Simmons, J.E. Censoring Trace-Level Environmental Data: Statistical Analysis Considerations to Limit Bias. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 3786–3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hites, R.A. Correcting for Censored Environmental Measurements. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 11059–11060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demissie, S.; Mekonen, S.; Awoke, T.; Mengistie, B. Dynamics of Spatiotemporal Variation of Groundwater Arsenic in Central Rift Vally of Ethiopia: A Serial Cross-Sectional Study. Environ. Health Insights 2024, 18, 11786302241285391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Xie, X.; Jiang, J.; Zhu, X. Improved Physics-Informed Neural Network for Reactive Transport Modeling of Groundwater Arsenic Enrichment. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2025, 68, 2781–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Duan, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, C. Identification of Hydrobiogeochemical Processes Controlling Seasonal Variations in Arsenic Concentrations Within a Riverbank Aquifer at Jianghan Plain, China. Water Resour. Res. 2018, 54, 4294–4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadati, A.; Farshchi, F.; Hasanzadeh, M.; Liu, Y.; Seidi, F. Colorimetric and Naked-Eye Detection of Arsenic(III) Using a Paper-Based Microfluidic Device Decorated with Silver Nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 21836–21850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pungjunun, K.; Praphairaksit, N.; Chailapakul, O. A Facile and Automated Microfluidic Electrochemical Platform for the In-Field Speciation Analysis of Inorganic Arsenic. Talanta 2023, 265, 124906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Liu, M.; Wang, N.; Li, G. A Critical Review on Arsenic Removal from Water Using Iron-Based Adsorbents. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 39545–39560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, M.A.; Bryan, M.S.; Jones, D.K.; Bulka, C.; Bradley, P.M.; Backer, L.C.; Focazio, M.J.; Silverman, D.T.; Toccalino, P.; Argos, M.; et al. Machine Learning Models of Arsenic in Private Wells Throughout the Conterminous United States As a Tool for Exposure Assessment in Human Health Studies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 5012–5023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, R.; Deng, Y.; Du, Y.; Xie, X. Predicting Geogenic Groundwater Arsenic Contamination Risk in Floodplains Using Interpretable Machine-Learning Model. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 340, 122787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| UTM 19S (WGS 84) Coordinates | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling Point | Zone | East | North | Altitude (m.a.s.l.) |

| Point 1 | Southern Border | 347,704 m E | 7,981,265 m S | 45 |

| Point 2 | Bio Garden Los Palos | 353,151 m E | 7,980,461 m S | 68 |

| Point 3 | Ashlands | 352,342 m E | 7,973,450 m S | 19 |

| Point | n | Mean (µg/L) | SD | CV (%) | IQR (µg/L) | Median ΔAs (µg/L) | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point 1 | 24 | 12.34 | 0.89 | 7.21 | 1.35 | 1.00 | 11.0 | 13.9 |

| Point 2 | 24 | 11.42 | 1.03 | 8.99 | 1.38 | 0.90 | 9.1 | 13.0 |

| Point 3 | 24 | 11.53 | 1.11 | 9.65 | 1.55 | 1.30 | 9.2 | 13.9 |

| Point | n | ρₛ As–EC | p (As–EC) | ρₛ As–TDS | p (As–TDS) | ρₛ As–pH | p (As–pH) | ρₛ As–Temp | p (As–Temp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point 1 | 24 | 0.21 | 0.335 | 0.58 | 0.003 | −0.12 | 0.570 | −0.09 | 0.676 |

| Point 2 | 24 | 0.13 | 0.534 | 0.29 | 0.167 | −0.05 | 0.817 | 0.09 | 0.679 |

| Point 3 | 24 | 0.38 | 0.071 | 0.32 | 0.127 | −0.16 | 0.458 | −0.06 | 0.783 |

| Global | 72 | 0.06 | 0.638 | −0.06 | 0.605 | −0.05 | 0.704 | −0.04 | 0.733 |

| Point | Period | n | Exceed | 95% CI (Wilson)—L | 95% CI (Wilson)—U | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point 1 | Annual | 24.00 | 24 | 1.0000 | 86.2% | 100.0% |

| Point 1 | H1 (Sep–Feb) | 12.00 | 12 | 1.0000 | 75.7% | 100.0% |

| Point 1 | H2 (Mar–Aug) | 12.00 | 12 | 1.0000 | 75.7% | 100.0% |

| Point 2 | Annual | 24.00 | 22 | 0.9167 | 74.2% | 97.7% |

| Point 2 | H1 (Sep–Feb) | 12.00 | 10 | 0.8333 | 55.2% | 95.3% |

| Point 2 | H2 (Mar–Aug) | 12.00 | 12 | 1.0000 | 75.7% | 100.0% |

| Point 3 | Annual | 24.00 | 22 | 0.9167 | 74.2% | 97.7% |

| Point 3 | H1 (Sep–Feb) | 12.00 | 12 | 1.0000 | 75.7% | 100.0% |

| Point 3 | H2 (Mar–Aug) | 12.00 | 10 | 0.8333 | 55.2% | 95.3% |

| Scope | Period | n | Exceed | 95% CI (Wilson)—L | 95% CI (Wilson)—U | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global | Annual | 72.00 | 68 | 0.9444 | 86.6% | 97.8% |

| Global | H1 (Sep–Feb) | 36.00 | 34 | 0.9444 | 81.9% | 98.5% |

| Global | H2 (Mar–Aug) | 36.00 | 34 | 0.9444 | 81.9% | 98.5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mori Sosa, L.J.P.; Morales Cabrera, D.U.; Florez Ponce De León, W.D. Temporal Variability of Arsenic in the Caplina Aquifer, La Yarada Los Palos, Peru: Implications for Risk-Based Drinking Water Management. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11025. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411025

Mori Sosa LJP, Morales Cabrera DU, Florez Ponce De León WD. Temporal Variability of Arsenic in the Caplina Aquifer, La Yarada Los Palos, Peru: Implications for Risk-Based Drinking Water Management. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11025. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411025

Chicago/Turabian StyleMori Sosa, Luis Johnson Paúl, Dante Ulises Morales Cabrera, and Walter Dimas Florez Ponce De León. 2025. "Temporal Variability of Arsenic in the Caplina Aquifer, La Yarada Los Palos, Peru: Implications for Risk-Based Drinking Water Management" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11025. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411025

APA StyleMori Sosa, L. J. P., Morales Cabrera, D. U., & Florez Ponce De León, W. D. (2025). Temporal Variability of Arsenic in the Caplina Aquifer, La Yarada Los Palos, Peru: Implications for Risk-Based Drinking Water Management. Sustainability, 17(24), 11025. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411025