Spatiotemporal Distribution of Cross-Platform Public Opinion in the 2023 Dezhou Earthquake: Implications for Disaster-Resilient Emergency Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Research Progress on Disaster-Related Public Opinion

2.2. Theoretical Foundations and Research Progress of Cross-Platform Social Media and Disaster Public Opinion

2.3. Multi-Platform Characteristics and Research Gap

3. Data and Methodology

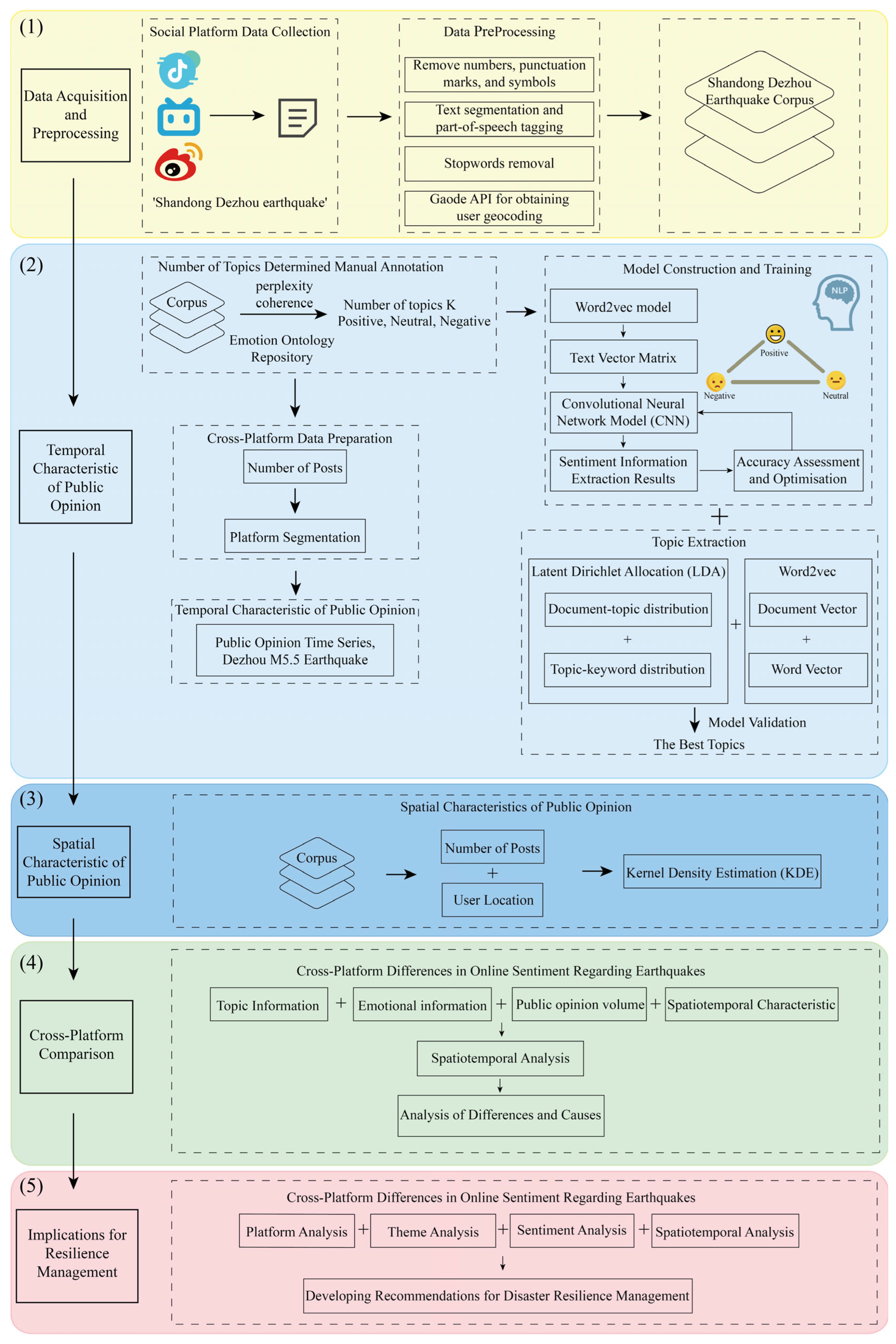

3.1. Framework for Earthquake Disaster Public Opinion Analysis

3.2. Overall Technical Process

3.3. Information Extraction from Social Media

3.3.1. Data Collection

3.3.2. Data Preprocessing

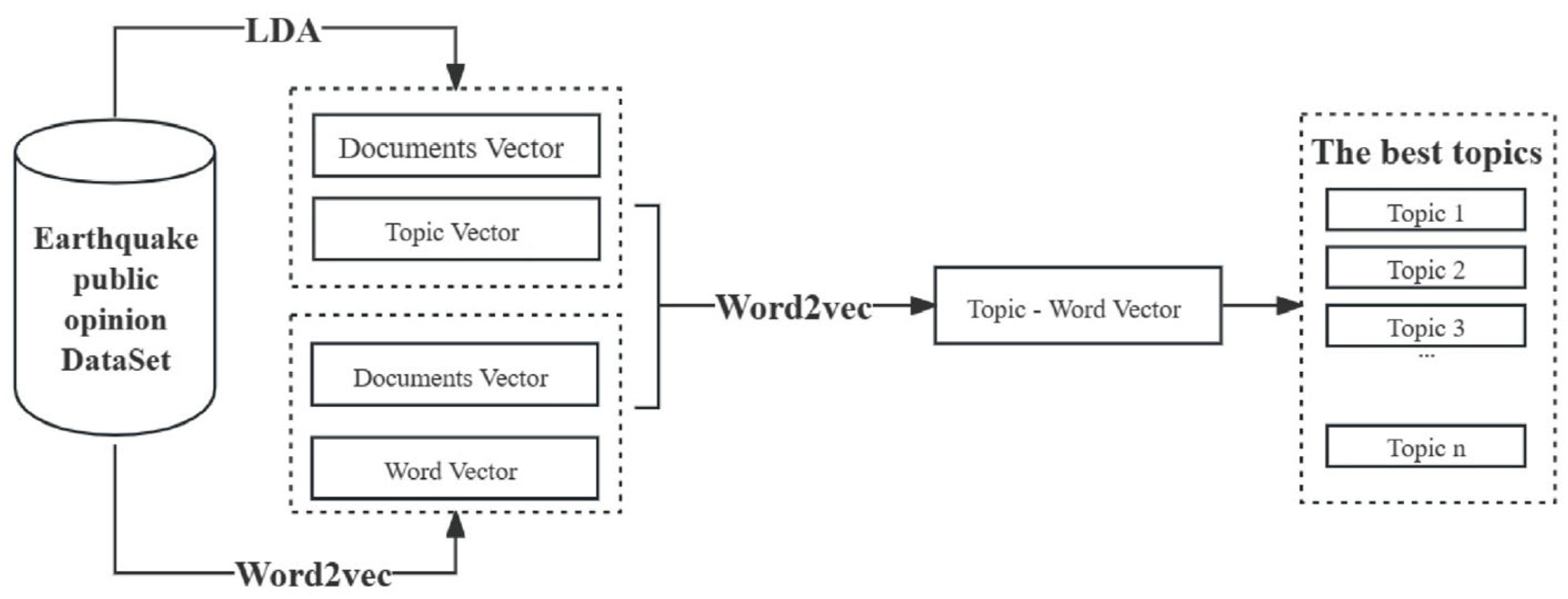

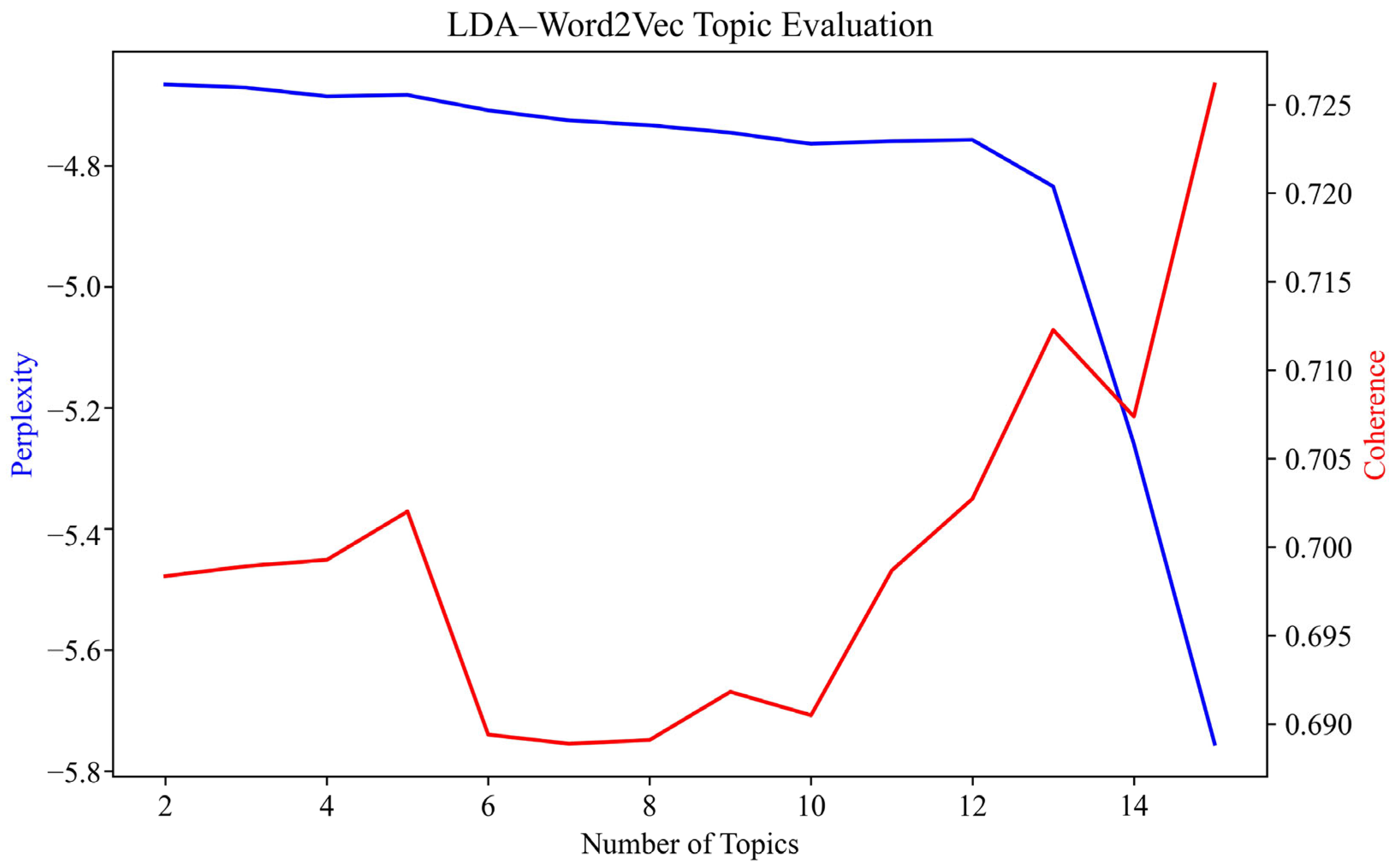

3.4. Topic Clustering Model Combining LDA and Word2Vec

3.4.1. Topic Extraction

3.4.2. Topic Clustering

3.4.3. Model Validation

3.5. Sentiment Classification and Accuracy Validation

3.6. Analysis of the Spatial Agglomeration Characteristics of Public Opinion

4. Results

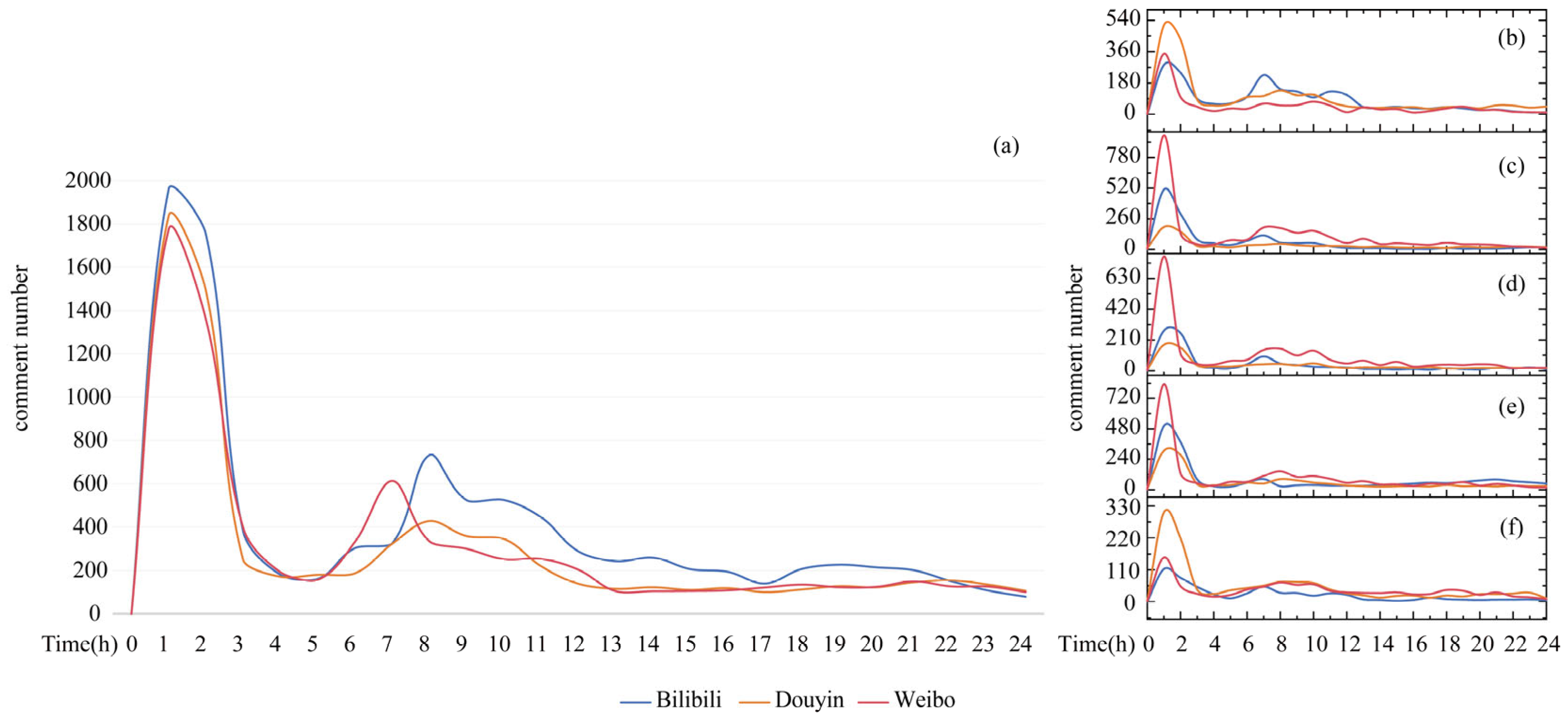

4.1. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Public Opinion

4.1.1. Temporal Characteristics of Public Opinion

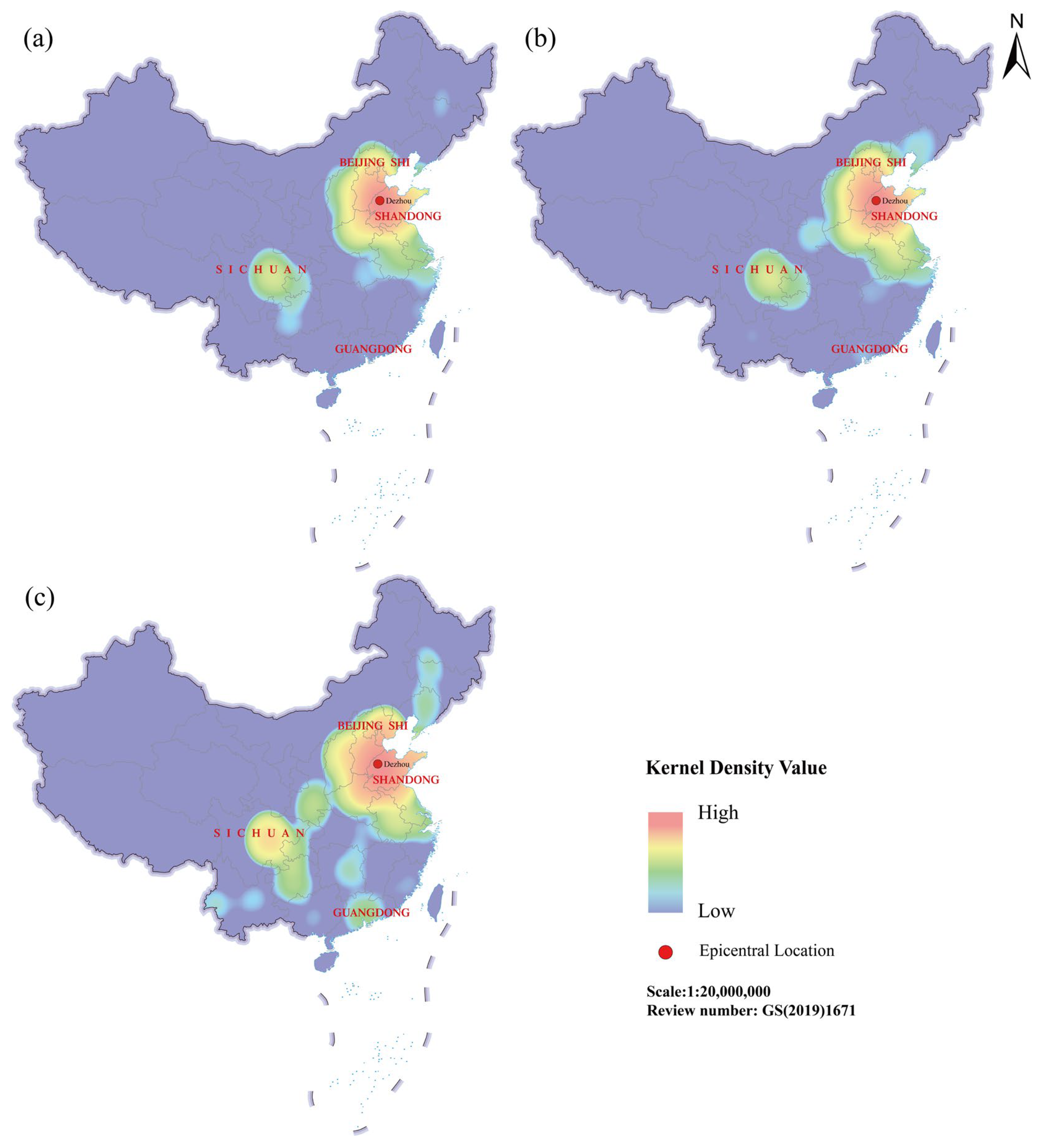

4.1.2. Spatial Characteristics of Public Opinion

4.2. Differences in and Reasons for Earthquake-Related Online Public Opinion Across the Three Platforms

5. Discussion

5.1. The Contributions of This Study to Existing Theories

5.2. Implications for Resilience Management Across Disaster Phases

5.2.1. Pre-Disaster: Public Sentiment Monitoring and Risk Communication Preparedness

5.2.2. In-Disaster: Real-Time Emotional Dynamics and Emergency Response Optimization

5.2.3. Post-Disaster: Regional Sentiment Divergence and Adaptive Psychological Support

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bi, X.; Tang, C.; Xiao, Q. Short Video Social Media Public Opinion Crisis Prevention. Library 2019, 6, 74–80+87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Fang, W.; Sun, R.; Hu, J. Risk Assessment and Survey of the Public Opinion on Three Earthquakes in Sichuan in 2022. J. Seismol. Res. 2024, 47, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Emergency Management Department of the Office of the National Disaster Prevention, Reduction and Relief Commission Released the Basic Situation of Natural Disasters in 2023. Available online: https://www.mem.gov.cn/xw/yjglbgzdt/202401/t20240120_475697.shtml (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Chu, M.; Song, W.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, T.; Chiang, Y.-C. Emotional contagion on social media and the simulation of intervention strategies after a disaster event: A modeling study. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Yang, S.; Wang, W. Social media-based disaster research: Development, trends, and obstacles. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 55, 102095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, E.; Yang, Z. Measuring emotional contagion in social media. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Yang, S.; Liu, Y.; Yao, K.; Wang, G. Typhoon Risk Perception: A Case Study of Typhoon Lekima in China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2022, 13, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Zhao, H.; Gu, Z.; Chen, X. Videolised Society; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, K.; Yang, S.; Tang, J. Rapid assessment of seismic intensity based on Sina Weibo—A case study of the changning earthquake in Sichuan Province, China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 58, 102217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albalawi, R.; Yeap, T.H.; Benyoucef, M. Using topic modeling methods for short-text data: A comparative analysis. Front. Artif. Intell. 2020, 3, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Liu, B.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Qin, K.; Guo, G. Social media information classification of earthquake disasters based on BERT transfer learning model. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 2024, 49, 1661–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Liu, K. Temporal, Spatial, and Socioeconomic Dynamics in Social Media Thematic Emphases during Typhoon Mangkhut. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, W.; Wei, B.; Zheng, G.; Feng, X.J. Spatiotemporal characteristics of public opinion and emotion analysis of Ms 6.4 Yunnan Yangbi earthquake based on Sina Weibo data. J. Nat. Disasters 2022, 31, 68–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhu, X.; Lu, P.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, S. Spatio-temporal evolution of public opinion on urban flooding: Case study of the 7.20 Henan extreme flood event. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 100, 104175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, D.; Shao, Q.; Yang, X.; Peng, H.; Bi, Q. Research on Operating Pattern of Network Public Opinion of Public Emergency from the Perspective of Information Ecology. Mod. Inf. 2022, 42, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Li, B. Information Perception Model of Network Public Opinion Risk of Environmental Emergencies in New Media Environment. Mod. Inf. 2023, 43, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Chang, J. Research on the Influencing Factors of Information Credibility of Public Health Emergencies in Social Media—Take Wechat as an Example. J. Mod. Inf. 2020, 40, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgay, S.; Aydin, A. Improving decision making under uncertainty with data analytics: Bayesian networks, reinforcement learning, and risk perception feedback for disaster management. J. Decis. Anal. Intell. Comput. 2025, 5, 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, R.; Yu, J. A topic modeling comparison between lda, nmf, top2vec, and bertopic to demystify twitter posts. Front. Sociol. 2022, 7, 886498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotham, K.F.; Campanella, R.; Lauve-Moon, K.; Powers, B. Hazard experience, geophysical vulnerability, and flood risk perceptions in a postdisaster city, the case of New Orleans. Risk Anal. 2018, 38, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, R.; Jarecki, J.B.; Meier, D.S.; Rieskamp, J. Risk preferences and risk perception affect the acceptance of digital contact tracing. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, J.L.; Weinhardt, J.M.; Beck, J.W.; Mai, I. Interpreting time-series COVID data: Reasoning biases, risk perception, and support for public health measures. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. Research on the Emotional Sentiment of TikTok Public Opinion in Response to Sudden Natural Disasters—A Case Study of the Zhengzhou Severe Rainstorm Disaster. Master’s Thesis, Zhengzhou University of Aeronautics, Zhengzhou, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, T.; Kong, Q.; McBride, S.K.; Sethjiwala, A.; Lv, Q. Cross-platform analysis of public responses to the 2019 Ridgecrest earthquake sequence on Twitter and Reddit. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvir-Gvirsman, S.; Sude, D.; Raisman, G. Unpacking news engagement through the perceived affordances of social media: A cross-platform, cross-country approach. New Media Soc. 2024, 26, 6487–6509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-J.; Lee, T.-R.; Lee, S.-J.; Jang, J.-S.; Kim, E.J. Machine learning-based data mining method for sentiment analysis of the Sewol Ferry disaster’s effect on social stress. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 505673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Han, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, Z. Risk perception and resilience assessment of flood disasters based on social media big data. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 101, 104249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, S.; Zhao, F. Social media-based urban disaster recovery and resilience analysis of the Henan deluge. Nat. Hazards. 2023, 118, 377–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, W.; Li, P. Spatiotemporal pattern evolution and influencing factors of online public opinion—Evidence from the early-stage of COVID-19 in China. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagliacci, F.; Russo, M. Socioeconomic effects of an earthquake: Does spatial heterogeneity matter? Reg. Stud. 2019, 53, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Pu, Z.; Zhu, Q. Influencing Factors of Microblog Public Opinion Dissemination: Based on the Perspective of Information Source Characteristic and Information Form. Inf. Doc. Serv. 2014, 35, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z. Analysis of the Characteristics, Challenges and Future Development Trends of Tik Tok. Mod. Educ. Technol. 2018, 28, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Z.; Li, S. Influence of Video Comments Characteristics on Viewers’Commenting Behaviors—Taking Bilibili as an Example. Lib. Inf. Serv. 2022, 66, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AutoNavi Open Platform. Available online: https://lbs.amap.com/api/webservice/guide/api/georegeo (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Text Analysis-Stop Words Set. Available online: https://download.csdn.net/download/cymlancy/10651346 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Lin, H.; Pan, Y.; Ren, H.; Chen, J. Constructing the Affective Lexicon Ontology. J. Chin. Soc. Sci. Tech. Inf. 2008, 27, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Z.; Chen, S. The evolution of online public opinion on earthquakes: A system dynamics approach. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Wu, J. Public perception of earthquake events: Evidence from social media—A case study of the 2025 Dingri earthquake. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk. 2025, 16, 2542196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ye, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Li, C.; Du, M. Evolution and spatiotemporal analysis of earthquake public opinion based on social media data. Earthq. Sci. 2024, 37, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhou, Y. An empirical study on factors influencing dissemination effect of short videos in popular science journals in China: Focusing on 50 Chinese outstanding popular science journals in 2020. Chin. J. Sci. Technol. Period. 2023, 34, 1616–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, H.; Li, G.; Han, B.; Yuan, Z.; Ma, H. A systematic review of resilience assessment and enhancement of urban integrated transportation networks. J. Transp. Geogr. 2025, 129, 104420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2023 New Media Ecological Insight: The Scale of Industry Users Is 1.088 Billion, and User Flow and Diversion Have Entered a New Stage. Available online: https://www.jiemian.com/article/10422640.html (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Li, S.; Shen, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y. Construction and Evolution Analysis of an Event Evolutionary Graph for Online Public Opinion on Mycoplasma Pneumonia. Inf. Sci. 2024, 43, 107–116+128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H. How Chinese user perceives ‘Positive Energy’ through short-form video platform Douyin. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Social Development and Media Communication (SDMC 2023), Hangzhou, China, 3–5 November 2023; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2023; pp. 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disaster Phase | Temporal Characteristic of Public Opinion | Spatial Characteristic of Public Opinion | Implications for Resilience Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Disaster Prevention Phase | Monitor routine early-warning topics and emotional preparedness | Map pre-event attention hotspots and population vulnerability areas | Develop public education campaigns and preparedness communication strategies tailored to at-risk regions |

| In-Disaster Response Phase | Analyze real-time emotional shifts and topic surges during key hours | Track spatial concern to inform response focus | Guide emergency info release and shape public opinion trajectory |

| Post-Disaster Recovery Phase | Monitor shifts in sentiment and topics | Identify continued high-concern areas and regional differences in public opinion | Support adaptive recovery planning and targeted communication interventions |

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Dataset | Earthquake-related posts from Sina Weibo (8775), Bilibili (12,219), and Douyin (7563) following the 2023 M5.5 Dezhou earthquake |

| Data Cleaning | Removal of URLs, emojis, and punctuation; Chinese word segmentation (Jieba); stopword filtering; duplicate removal |

| Feature Extraction | CountVectorizer default |

| Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) Parameters | K = 5; inference = variational Bayes; iter = 50 |

| Word2Vec Parameters | vector_size = 120; window = 5; min_count = 5; sg = 1; workers = 4; epochs = 30; seed = 42; hs = 1 negative = 0 |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) Parameters | vocabulary size = 10,000; maximum sequence length = 100; batch size = 128; dropout rate = 0.3; stride = 1 |

| Robustness Checks | seeds = [11, 22, 33, 44, 55]; passes = 15 (final model training passes) |

| Validation Metrics | coherence = ‘c_w2v’ (Word2Vec semantic coherence); perplexity (perplexity metric); optimal_k selection (select optimal topics based on max coherence) |

| Source | Username | Post Time | Comments | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li*ting | 6 August 2023 18:41 | I am based in Jinan City. The earthquake woke me up. Squatting on the bed, I felt the whole earth shaking. A five-or-so-pound fan fell (later found). | Jinan | |

| Bilibili | isca*iii | 6 August 2023 11:15 | In Pingyuan County, Dezhou City, I was very scared and numb because I didn’t expect an earthquake. | Dezhou |

| Douyin | zhon*ao | 6 August 2023 8:59 | I’m from Dezhou City. I slept in my car when the earthquake happened last night. | Dezhou |

| Category | Feature Words |

|---|---|

| Earthquake Experience | Obvious, Strong, Shocking, Shaking, Sensation, Dizzy, Bed Shaking, Awake from Shaking, Real, Awakened, Slight, Very Strong, Intense, Vibrating, Awakened by Shaking, Building, Swaying, Trembling, Violent |

| Science Popularization | Disaster Self-rescue, Knowledge, Evacuation Guide, Swift, Mastery, Scientific, Escape, Popular Science, Methods, History, Seismological Bureau, Region, Unusual Sky, S-waves, Geology, Fault Zone, Prediction, Technology, Seismic Resistance, Phenomenon, Trigger, Destructive, Meteorology, Formation, Construction, Tectonic Plate |

| Positive wishes | Safe and Sound, Hope, Safe and Well, Well-being, Blessing, Health, Safety Awareness, National Peace, Divine Protection, Prayers, Everyone, People, Fellow Countrymen, Wishing for Safety |

| Earthquake Information | Alarm, Mobile Phone, Reminder, Notification, Wake-up Call, Activate, Early Warning, Advance, Countdown, Function, Woken Up, Frenzy, Emergency Services, Safety, Natural Disasters, Steward, Push, Urgency, Heard, Emergency |

| Psychological State | Dazed, Scared to Death, Startled Awake, Hallucination, Confused, Fearful, Anxious, Panic, Nauseous, Nervous, Excited, Stimulated, Lingering Fear, Terrifying, Nightmares, Dizzy, Haunted, Unexpected, Comfortable, Scared, Sudden Death, Tired, Baffled |

| Topic Category | Platform | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sina Weibo (Entries) | Proportion (%) | Bilibili (Entries) | Proportion (%) | Douyin (Entries) | Proportion (%) | |

| Science Popularization | 687 | 7.8 | 1290 | 10.6 | 1193 | 15.8 |

| Psychological States | 2346 | 26.7 | 2639 | 21.6 | 1263 | 16.7 |

| Earthquake information | 1243 | 14.2 | 2564 | 21.0 | 752 | 9.9 |

| Earthquake Experience | 1705 | 19.4 | 3029 | 24.8 | 678 | 9.0 |

| Positive Wishes | 2183 | 24.9 | 1409 | 11.5 | 2198 | 29.1 |

| Positive | 3325 | 37.9 | 3946 | 32.3 | 3061 | 40.5 |

| Neutral | 3755 | 42.8 | 5571 | 45.6 | 2845 | 37.6 |

| Negative | 1693 | 19.3 | 2700 | 22.1 | 1560 | 20.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, C.; Wang, X.; Ye, Y. Spatiotemporal Distribution of Cross-Platform Public Opinion in the 2023 Dezhou Earthquake: Implications for Disaster-Resilient Emergency Management. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10937. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410937

Li C, Wang X, Ye Y. Spatiotemporal Distribution of Cross-Platform Public Opinion in the 2023 Dezhou Earthquake: Implications for Disaster-Resilient Emergency Management. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):10937. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410937

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Chen, Xurui Wang, and Yanjun Ye. 2025. "Spatiotemporal Distribution of Cross-Platform Public Opinion in the 2023 Dezhou Earthquake: Implications for Disaster-Resilient Emergency Management" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 10937. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410937

APA StyleLi, C., Wang, X., & Ye, Y. (2025). Spatiotemporal Distribution of Cross-Platform Public Opinion in the 2023 Dezhou Earthquake: Implications for Disaster-Resilient Emergency Management. Sustainability, 17(24), 10937. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410937