Spatial Heterogeneity in Drought Propagation from Meteorological to Hydrological Drought in Southern China and Its Influencing Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Descriptions of Study Area

2.2. Data

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI)

2.3.2. Standardized Terrestrial Water Storage Index (STI)

2.3.3. Drought Propagation Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Distribution of MD and HD

3.2. Drought Propagation from MD to HD

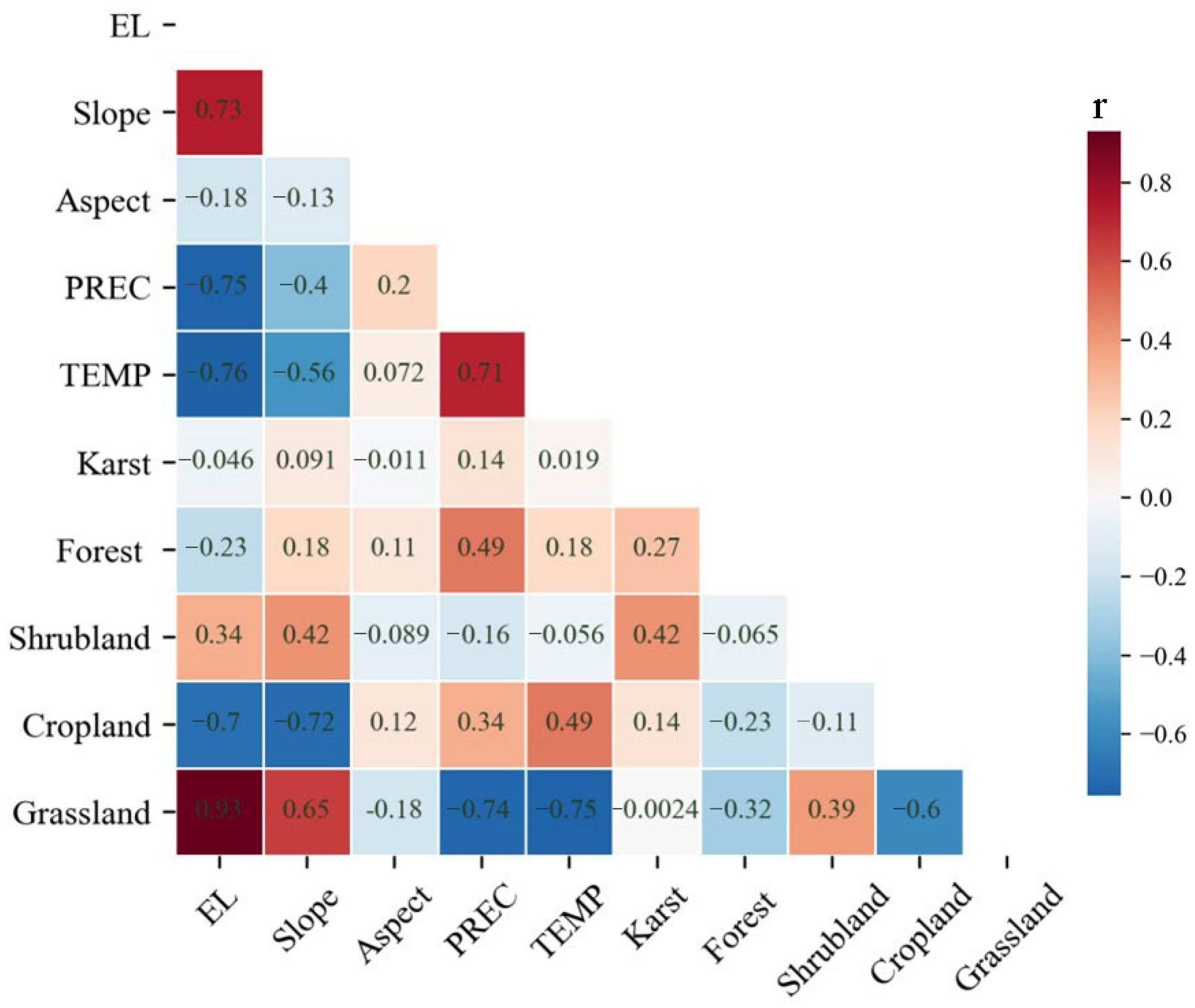

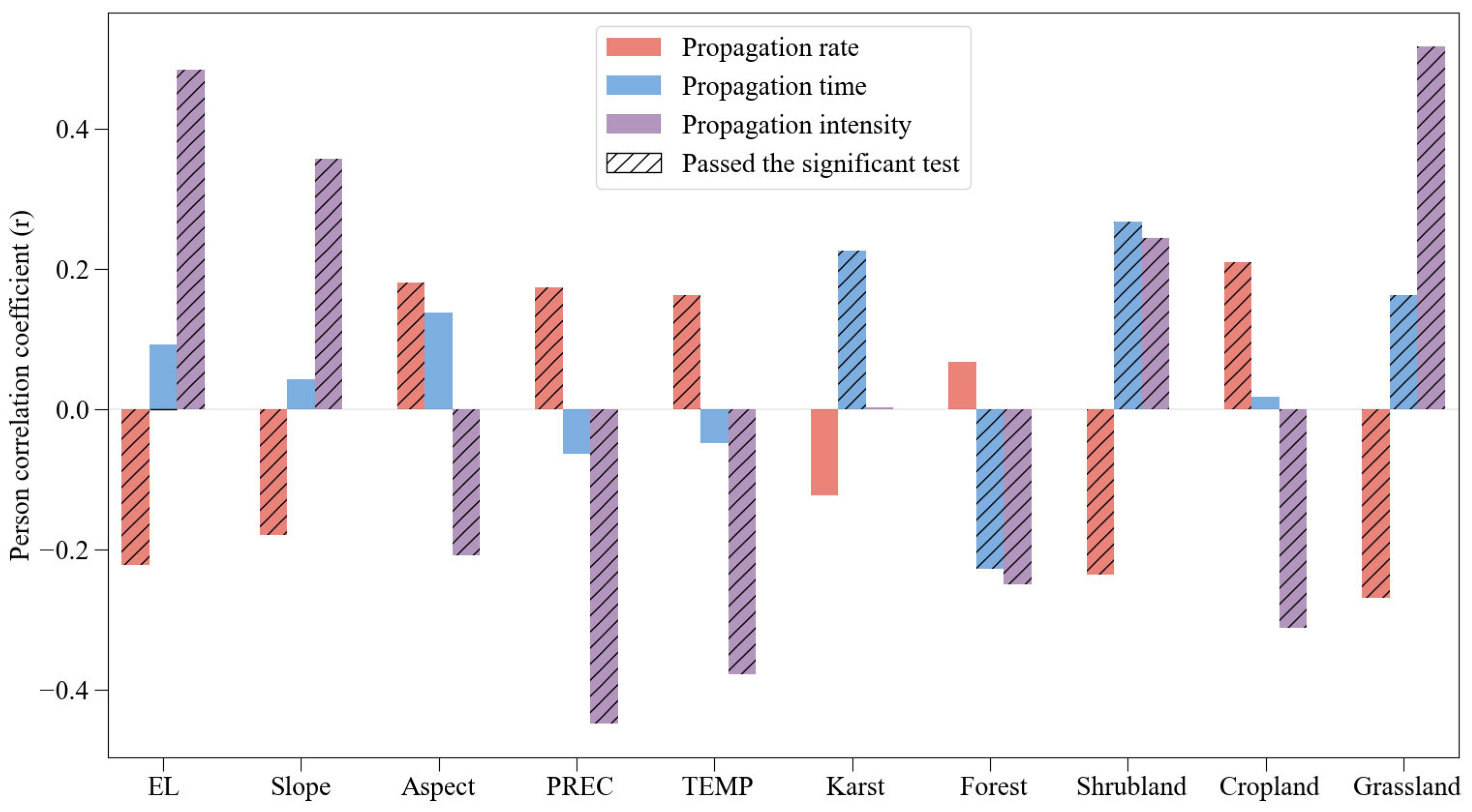

3.3. Correlation Analysis of Various Factors and the Three Drought Propagation Indicators

4. Discussion

4.1. The Controlling Factors for Drought Propagation

4.2. The Spatial Distribution Characteristics of HD

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MD | Meteorological Drought |

| HD | Hydrological Drought |

| TWS | Terrestrial Water Storage |

| GRACE | Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment |

| SPI | Standardized Precipitation Index |

| STI | Standardized Terrestrial Water Storage Index |

| CMFD | China Meteorological Forcing Dataset |

| PoMSE | Proportion of Moderate, Severe and Extreme Droughts to the total number of drought events |

References

- Mishra, A.K.; Singh, V.P. A Review of Drought Concepts. J. Hydrol. 2010, 391, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loon, A.F. Hydrological Drought Explained. WIREs Water 2015, 2, 359–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, K.; Kohn, I.; Blauhut, V.; Urquijo, J.; De Stefano, L.; Acácio, V.; Dias, S.; Stagge, J.H.; Tallaksen, L.M.; Kampragou, E.; et al. Impacts of European Drought Events: Insights from an International Database of Text-Based Reports. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2016, 16, 801–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanders, N.; Wada, Y.; Van Lanen, H.A.J. Global Hydrological Droughts in the 21st Century under a Changing Hydrological Regime. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2015, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, P.; Li, L.; Fu, Q.; Ding, Y.; Chen, P.; Xue, P.; Wang, T.; Shi, H. Recent Development on Drought Propagation: A Comprehensive Review. J. Hydrol. 2024, 645, 132196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Huang, S.; Huang, Q.; Leng, G.; Fang, W.; Wang, L.; Wang, H. Propagation Thresholds of Meteorological Drought for Triggering Hydrological Drought at Various Levels. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 712, 136502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hao, Z.; Singh, V.P.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, S.; Xu, Y.; Hao, F. Drought Propagation under Global Warming: Characteristics, Approaches, Processes, and Controlling Factors. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, L.J.; Hannaford, J.; Chiverton, A.; Svensson, C. From Meteorological to Hydrological Drought Using Standardised Indicators. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2016, 20, 2483–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Su, X.; Zhang, G.; Wu, H.; Wang, G.; Chu, J. Evaluation of the Impacts of Human Activities on Propagation from Meteorological Drought to Hydrological Drought in the Weihe River Basin, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 819, 153030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, A.; Li, J.; Zhou, Q.; Zhu, H.; Liu, H.; Yang, C.; Wu, G.; Li, Q. Propagation Dynamics from Meteorological Drought to GRACE-Based Hydrological Drought and Its Influencing Factors. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, X.; Cai, H.; Zhou, Z.; Sun, Y.; Shi, H. Propagation of Meteorological to Hydrological Drought for Different Climate Regions in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 283, 111980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslinger, K.; Koffler, D.; Schöner, W.; Laaha, G. Exploring the Link between Meteorological Drought and Streamflow: Effects of Climate-Catchment Interaction. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 2468–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fan, J.; Deng, Q.; Wang, X. Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity in Meteorological and Hydrological Drought Patterns and Propagations Influenced by Climatic Variability, LULC Change, and Human Regulations. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meresa, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, J.; Abrar Faiz, M. Understanding the Role of Catchment and Climate Characteristics in the Propagation of Meteorological to Hydrological Drought. J. Hydrol. 2023, 617, 128967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoelzle, M.; Stahl, K.; Morhard, A.; Weiler, M. Streamflow Sensitivity to Drought Scenarios in Catchments with Different Geology. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 6174–6183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loon, A.F.; Laaha, G. Hydrological Drought Severity Explained by Climate and Catchment Characteristics. J. Hydrol. 2015, 526, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senbeta, T.B.; Napiórkowski, J.J.; Karamuz, E.; Kochanek, K.; Woyessa, Y.E. Impacts of Water Regulation through a Reservoir on Drought Dynamics and Propagation in the Pilica River Watershed. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 53, 101812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, X.; Yao, H.; Gao, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, M. Non-Linear Relationship of Hydrological Drought Responding to Meteorological Drought and Impact of a Large Reservoir. J. Hydrol. 2017, 551, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Ma, M.; Zhang, X.; Leng, G.; Su, Z.; Lv, J.; Yu, Z.; Yi, P. Altered Drought Propagation under the Influence of Reservoir Regulation. J. Hydrol. 2021, 603, 127049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Xu, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, Q. The Impact of Climatic Conditions, Human Activities, and Catchment Characteristics on the Propagation From Meteorological to Agricultural and Hydrological Droughts in China. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2023, 128, e2023JD039735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Sun, G.; Huang, X.; Tang, R.; Jin, K.; Lai, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, D.; Yang, Z.-L.; et al. Urbanization Alters Atmospheric Dryness through Land Evapotranspiration. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2023, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wang, S.; Gan, Y.; Wang, C.; Horton, D.E.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Niyogi, D.; Xia, J.; Chen, N. Widespread Global Exacerbation of Extreme Drought Induced by Urbanization. Nat. Cities 2024, 1, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Miao, C.; Zheng, H.; Duan, Q.; Lei, X.; Li, H. Meteorological and Hydrological Drought on the Loess Plateau, China: Evolutionary Characteristics, Impact, and Propagation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2018, 123, 11569–11584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, Q.; Wang, L.; Lei, L.; Huang, M.; Xiang, J.; Feng, W.; Zhao, Y.; Xue, D.; Liu, C.; et al. Impact of Climate Change and Land-Use on the Propagation from Meteorological Drought to Hydrological Drought in the Eastern Qilian Mountains. Water 2019, 11, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Wang, W.; van Oel, P.R.; Lu, J.; Wang, G.; Wang, H. Impacts of Different Human Activities on Hydrological Drought in the Huaihe River Basin Based on Scenario Comparison. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2021, 37, 100909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Yue, W.; Wang, T.; Zheng, N.; Wu, L. Assessing the Use of Standardized Groundwater Index for Quantifying Groundwater Drought over the Conterminous US. J. Hydrol. 2021, 598, 126227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, S.; Roy, M.B.; Roy, P.K. Analysis of Groundwater Level Trend and Groundwater Drought Using Standard Groundwater Level Index: A Case Study of an Eastern River Basin of West Bengal, India. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Ren, J.; Kang, S.; Niu, J.; Tong, L. Spatial-Temporal Dynamics of Meteorological and Agricultural Drought in Northwest China: Propagation, Drivers and Prediction. J. Hydrol. 2025, 650, 132492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Cheng, H.; Liu, L. Assessing the Recent Droughts in Southwestern China Using Satellite Gravimetry. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 3030–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Lai, H.; Li, Y.; Feng, K.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, Q.; Zhu, X.; Yang, H. Dynamic Variation of Meteorological Drought and Its Relationships with Agricultural Drought across China. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 261, 107301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapley, B.D.; Bettadpur, S.; Watkins, M.; Reigber, C. The Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment: Mission Overview and Early Results. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004, 31, L09607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, A.; Li, J.; Zhou, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Zhu, R.; Liu, H.; Wu, G.; Li, Q. Use of a Multiscalar GRACE-Based Standardized Terrestrial Water Storage Index for Assessing Global Hydrological Droughts. J. Hydrol. 2021, 603, 126871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.C.; Reager, J.T.; Famiglietti, J.S.; Rodell, M. A GRACE-based Water Storage Deficit Approach for Hydrological Drought Characterization. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.; Shen, Y.; Sun, A.; Hong, Y.; Longuevergne, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, B.; Chen, L. Drought and Flood Monitoring for a Large Karst Plateau in Southwest China Using Extended GRACE Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 155, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Shen, Y. Temporal and Spatial Dynamics of Drought in Central Asia during 2002–2017 Based on Grace Data. Preprints 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Liu, S.; Mo, X. Assessment and Attribution of China’s Droughts Using an Integrated Drought Index Derived from GRACE and GRACE-FO Data. J. Hydrol. 2021, 603, 127170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; You, W.; Yang, X.; Fan, D. Improving Understanding of Drought Using Extended and Downscaled GRACE Data in the Pearl River Basin. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 58, 102277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Feng, X.; Ciais, P.; Fu, B.; Hu, B.; Sun, Z. GRACE Satellite-Based Drought Index Indicating Increased Impact of Drought over Major Basins in China during 2002–2017. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 291, 108057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Wen, C.; Wen, Z.; Gang, H. Drought in Southwest China: A Review. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. Lett. 2015, 8, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, W.; Haung, G.; Wang, T.; Wang, Q.; Su, X.; Ren, Z.; Chotamonsak, C.; Limsakul, A.; Torsri, K. Characteristics of Super Drought in Southwest China and the Associated Compounding Effect of Multiscalar Anomalies. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2024, 67, 2084–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Yang, X.; Xie, L.; Ye, Z.; Ren, L.; Zhang, L.; Wu, F.; Jiao, D. Propagation Characteristics of Meteorological Drought to Hydrological Drought in China. J. Hydrol. 2025, 656, 133023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Wen, T.; Shi, P.; Qu, S.; Zhao, L.; Li, Q. Analysis of Characteristics of Hydrological and Meteorological Drought Evolution in Southwest China. Water 2021, 13, 1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Qin, G.; Niu, J.; Wu, C.; Hu, B.X.; Huang, G.; Wang, P. Comparative Analysis of Meteorological and Hydrological Drought over the Pearl River Basin in Southern China. Hydrol. Res. 2018, 50, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Shi, H.; Fu, Q.; Ding, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S. Characteristics of Propagation From Meteorological Drought to Hydrological Drought in the Pearl River Basin. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2021, 126, e2020JD033959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Zhang, X.; Chen, N.; Li, B.; Ma, H.; Xu, L.; Li, R.; Niyogi, D. Drought Propagation Modification after the Construction of the Three Gorges Dam in the Yangtze River Basin. J. Hydrol. 2021, 603, 127138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Yeh, P.J.-F.; Pan, Y.; Jiao, J.J.; Gong, H.; Li, X.; Güntner, A.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, L. Detection of Large-Scale Groundwater Storage Variability over the Karstic Regions in Southwest China. J. Hydrol. 2019, 569, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wu, F.; Yuan, S.; Ren, L.; Sheffield, J.; Fang, X.; Jiang, S.; Liu, Y. Quantifying the Impact of Human Activities on Hydrological Drought and Drought Propagation in China Using the PCR-GLOBWB v2.0 Model. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR035443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Save, H.; Bettadpur, S.; Tapley, B.D. High-Resolution CSR GRACE RL05 Mascons. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2016, 121, 7547–7569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Yang, K.; Tang, W.; Lu, H.; Qin, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, X. The First High-Resolution Meteorological Forcing Dataset for Land Process Studies over China. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Zhu, D.; Weng, J.; Zhu, X.; Han, X.; Wang, X.; Cai, G.; Zhu, Y.; Cui, G.; Deng, Z. Karst Geology of China; Geological Publiching House: Beijing, China, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, M.; Svoboda, M.; Wall, N.; Widhalm, M. The Lincoln Declaration on Drought Indices: Universal Meteorological Drought Index Recommended. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2011, 92, 485–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, T.B.; Doesken, N.J.; Kleist, J. The Relationship of Drought Frequency And Duration To Time Scales. In Proceedings of the Eighth Conference on Applied Climatology, Anaheim, CA, USA, 17–22 January 1993; pp. 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Mhenni, N.; Shinoda, M.; Nandintsetseg, B. Assessment of Drought Frequency, Severity, and Duration and Its Impacts on Vegetation Greenness and Agriculture Production in Mediterranean Dryland: A Case Study in Tunisia. Nat. Hazards 2021, 105, 2755–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Liang, L.; Jun, H.; Yan, D.; Wang, X.; Li, C.; Sun, T. Thresholds for Triggering the Propagation of Meteorological Drought to Hydrological Drought in Water-Limited Regions of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 876, 162771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattar, M.N.; Lee, J.-Y.; Shin, J.-Y.; Kim, T.-W. Probabilistic Characteristics of Drought Propagation from Meteorological to Hydrological Drought in South Korea. Water Resour. Manag. 2019, 33, 2439–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Ye, A.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J. The Peer-To-Peer Type Propagation From Meteorological Drought to Soil Moisture Drought Occurs in Areas With Strong Land-Atmosphere Interaction. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58, e2022WR032846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wei, W.; Wang, L.; Chen, S.; Duan, W.; Zhang, Q.; Tong, B.; Han, Z.; Li, Z.; Chen, L. Trigger Thresholds and Propagation Mechanism of Meteorological Drought to Agricultural Drought in an Inland River Basin. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 311, 109378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Miao, C.; Guo, X.; Gou, J.; Su, T. Human Activities Impact the Propagation from Meteorological to Hydrological Drought in the Yellow River Basin, China. J. Hydrol. 2023, 623, 129752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilstedt, U.; Malmer, A.; Verbeeten, E.; Murdiyarso, D. The Effect of Afforestation on Water Infiltration in the Tropics: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. For. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 251, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Yang, H.; Guan, D.; Yang, M.; Wu, J.; Yuan, F.; Jin, C.; Wang, A.; Zhang, Y. The Effects of Land Use Change on Soil Infiltration Capacity in China: A Meta-Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 626, 1394–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Sun, L.; Jamshidi, A.H.; Liu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Fan, Z. Effect of Forest Conversion on Soil Water Infiltration in the Dabie Mountainous Area, China. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 59, 102351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namwong, C.; Suwanprasit, C.; Shahnawaz, S.; Wongpornchai, P. Assessing the Relationship between Forest Proportion, Soil Moisture Index and Net Primary Productivity in Pa Sak Ngam, Chiang Mai Province, Thailand. Int. J. Geoinform. 2023, 19, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Li, X.; Yang, N.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, Z. Spatio-temporal Variation of Vegetation and its Correlation with Soil Moisture in the Yellow River Basin. Hydrogeol. Eng. Geol. 2023, 50, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, Q.; Chang, X. Spatio-temporal Variation and Interrelationship of Vegetation Cover and Soil Moisture in Qinling-Daba Mountains. J. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2018, 20, 967–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Zhao, J.; Li, H.-Y.; Mishra, A.; Ruby Leung, L.; Hejazi, M.; Wang, W.; Lu, H.; Deng, Z.; Demissisie, Y.; et al. Hydrological Drought in the Anthropocene: Impacts of Local Water Extraction and Reservoir Regulation in the U.S. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2017, 122, 11313–11328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Cheng, H.; Wang, H.; Zhu, Y. Propagation from Meteorological to Hydrological Drought and Its Influencing Factors in the Huaihe River Basin. Water 2021, 13, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Tang, H.; Qu, S.; Zhao, L.; Li, Q. Drought Propagation in Karst and Non-Karst Regions in Southwest China Compared on a Daily Scale. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 51, 101628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Bai, X.; Wang, S.; Zhou, D.; Li, Y.; Peng, T.; Tian, Y.; Luo, G. Major Problems and Solutions on Surface Water Resource Utilisation in Karst Mountainous Areas. Agric. Water Manag. 2015, 159, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, R.; Lu, H.; Cao, J.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Z.; Luan, S. Characteristics of groundwater resources of karst areas in the Southern China and water resources guarantee countermeasures. Geol. China 2022, 49, 1139–1153, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

| Grade | SPI | STI |

|---|---|---|

| No drought | −0.5 < SPI | −0.5 < STI |

| Mild drought | −1 < SPI ≤ −0.5 | −1 < STI ≤ −0.5 |

| Moderate drought | −1.5 < SPI ≤ −1 | −1.5 < STI ≤ −1 |

| Severe drought | −2 < SPI ≤ −1.5 | −2 < STI ≤ −1.5 |

| Extreme drought | SPI ≤ −2 | STI ≤ −2 |

| Propagation Time | Propagation Rate | Propagation Intensity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Propagation time | 1 | −0.14 | 0.17 |

| Propagation rate | −0.14 | 1 | −0.85 * |

| Propagation intensity | 0.17 | −0.85 * | 1 |

| HD Characteristics | Mean Precipitation | Mean Temperature | Elevation | Slope | Grassland | Shrubland | Forest | Cropland | Karst |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD frequency | 0.3 * | 0.25 * | −0.36 * | −0.28 * | −0.44 | −0.39 | 0.14 | 0.24 | −0.23 |

| PoMSE | −0.305 * | −0.33 * | 0.32 * | 0.25 * | 0.25 * | −0.13 | 0.086 | −0.25 * | −0.46 * |

| HD severity | −0.649 * | −0.56 * | 0.63 * | 0.44 * | 0.65 * | 0.05 | −0.31 * | −0.46 * | −0.34 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, C. Spatial Heterogeneity in Drought Propagation from Meteorological to Hydrological Drought in Southern China and Its Influencing Factors. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410922

Chang Y, Liu L, Wang Z, Zhang C. Spatial Heterogeneity in Drought Propagation from Meteorological to Hydrological Drought in Southern China and Its Influencing Factors. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):10922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410922

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Yong, Ling Liu, Ziying Wang, and Changwei Zhang. 2025. "Spatial Heterogeneity in Drought Propagation from Meteorological to Hydrological Drought in Southern China and Its Influencing Factors" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 10922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410922

APA StyleChang, Y., Liu, L., Wang, Z., & Zhang, C. (2025). Spatial Heterogeneity in Drought Propagation from Meteorological to Hydrological Drought in Southern China and Its Influencing Factors. Sustainability, 17(24), 10922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410922