Economic Dynamics of Informal Output in Romania: An ARDL Approach to Policy, Growth, and Institutional Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

- ➢

- RQ1: How do macroeconomic variables such as inflation, GDP per capita, and interest payments influence the informal economy in Romania in both the short and long run?

- ➢

- RQ2: Can institutional factors, such as political stability and fiscal balance, determine the size of Romania’s informal economy?

- ➢

- RQ3: Does self-employment contribute to the reduction in informality, and how does it reflect broader labor market transformations?

- ➢

- RQ4: What is the speed of adjustment of Romania’s informal economy toward long-run equilibrium following macroeconomic shocks?

2. Research Gap and Literature Review

2.1. Recent Contributions to the Study of Informality

2.1.1. Institutional Quality and Informality

2.1.2. Macroeconomic Volatility and Informal Economy

2.1.3. Fiscal Policy and Informality

2.1.4. Labor Market Dynamics and Self-Employment

2.1.5. Technological Advancement and Informality

2.1.6. Informality, Economic Sustainability, and Institutional Resilience

2.2. Research Gap, Conceptual Framework, and Contribution

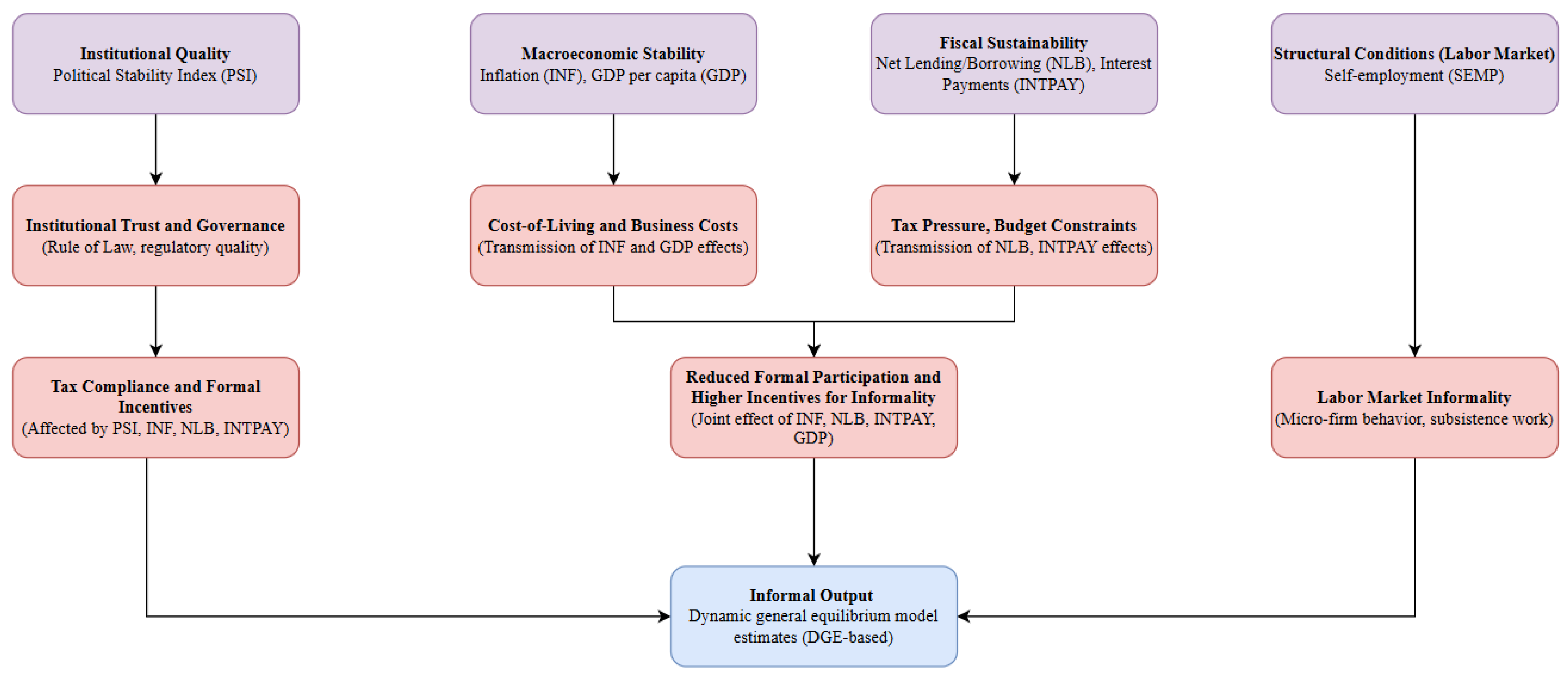

2.3. Conceptual Framework and Theoretical Mechanisms of Informal Output Dynamics

3. Data Collection and Methodology

- ➢

- Step 1—Unit root testing: We test whether the variables are stationary (I (0)) or become stationary after differentiation (I (1)), using ADF. ARDL can only be applied if none of them are I (2).

- ➢

- Step 2—Selecting optimal lags: We determine the optimal number of lags using the VAR criteria to ensure the correct dynamics of the model.

- ➢

- Step 3—Choosing ARDL model: Based on the selected lags, the ARDL structure is specified (, where is the lag of the dependent variable, and are the lags of the explanatory variables.

- ➢

- Step 4—Estimating the ARDL model with selected lags: We estimate the ARDL model through OLS, which allows us to obtain the short-run coefficients and the preliminary long-run relationship.

- ➢

- Step 5—Performing the Bounds Test for cointegration: We apply the cointegration test to check whether there is a long-run equilibrium relationship between the variables.

- ➢

- Step 6—Extracting the long-run coefficients: In the case of confirmation of cointegration, long-run coefficients are extracted from the levels of the variables in the ARDL model.

- ➢

- Step 7—Constructing the error-correction model (ECM): We construct the ECM based on the lagged error term, which measures the speed of adjustment towards the long-run equilibrium.

- ➢

- Step 8—Estimating short-run dynamics: We estimate the short-term coefficients of the variables, which capture transient effects and immediate adjustments.

- ➢

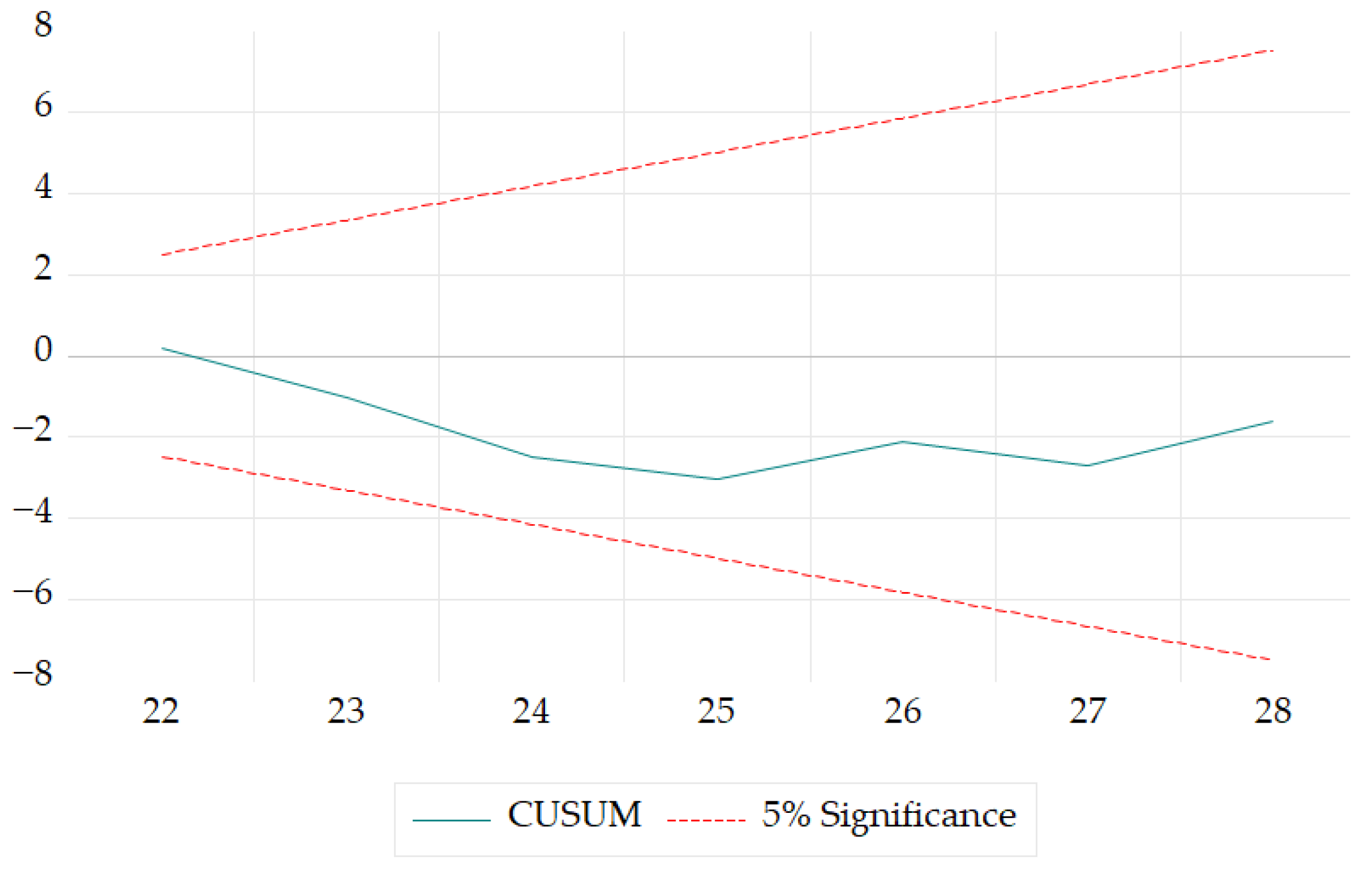

- Step 9—Running diagnostic tests: We apply standard validation tests—autocorrelation, heteroscedasticity, normality of residuals, and parameter stability (CUSUM, CUSUMSQ).

- ➢

- Step 1—Data preparation: the series were logarithmized, and we worked with ordinal variations first, which approximated the percentage rates.

- ➢

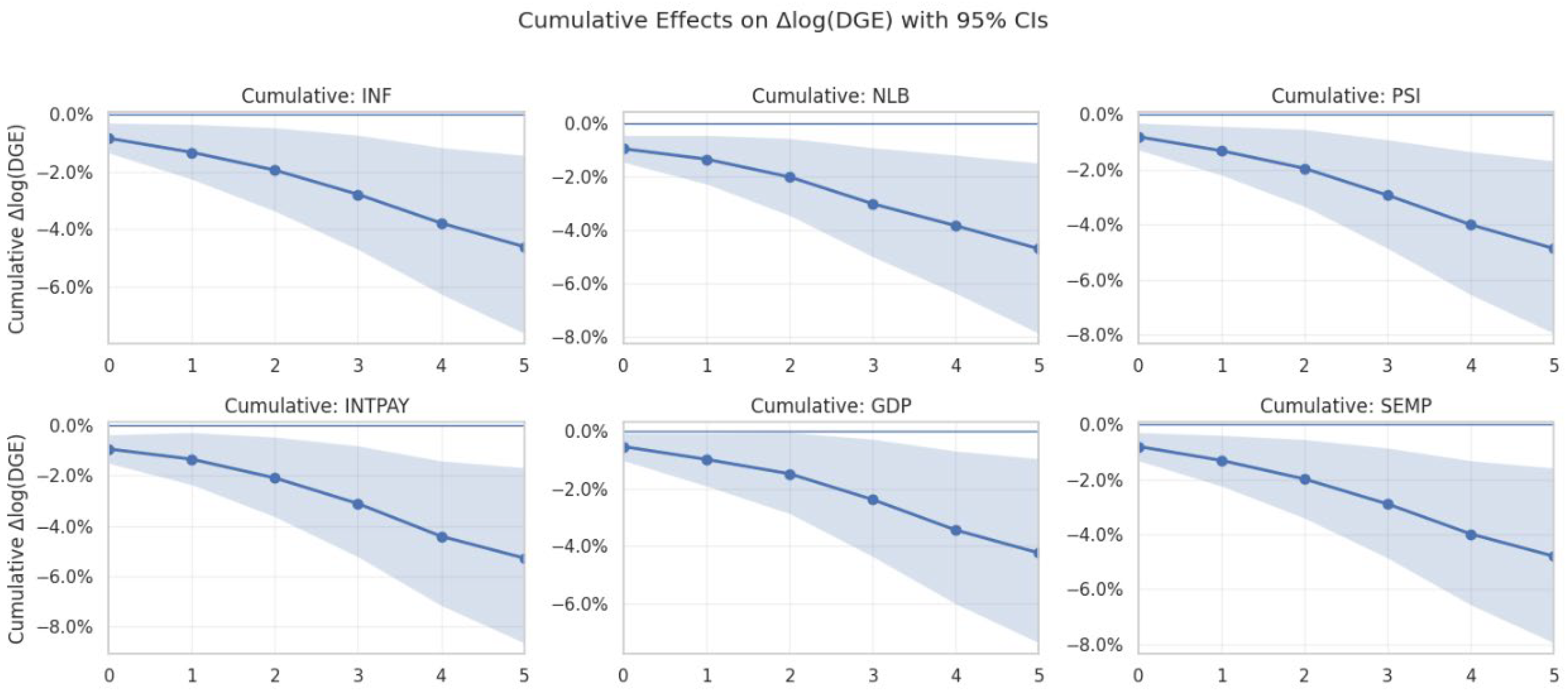

- Step 2—Local Projection specification for each horizon : For we estimated equations of the type expressed in relation (4), with . The coefficient was the dynamic response to a unit shock in .

- ➢

- Step 3—Ordinary Least Square (OLS) estimation: we built the regressor matrix and used numpy.linalg.lstsq for OLS. We repeated for each and for each shock variable.

- ➢

- Step 4—Bootstrap inference (95% Confidence Interval): for each h, we resampled the regression residuals and re-estimated on bootstrap samples, building confidence bands. The 5-year cumulative effects were obtained by applying relation (5).

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Robustness Checks Using CCR, FMOLS, and DOLS

| Variable | CCR Coefficient | CCR t-Statistic | FMOLS Coefficient | FMOLS t-Statistic | DOLS Coefficient | DOLS t-Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INF | 0.014023 *** | 5.7821 | 0.013830 *** | 7.4448 | 0.013568 *** | 6.6748 |

| NLB | 0.001292 | 0.5875 | 0.000861 | 0.5308 | 0.000443 | 0.2585 |

| PSI | 0.003473 | 0.2849 | 0.004644 | 0.4879 | 0.007482 | 0.7141 |

| INTPAY | 0.039803 *** | 11.407 | 0.039751 *** | 12.3239 | 0.039030 *** | 11.0481 |

| GDP | 0.253100 *** | 12.4026 | 0.256734 *** | 14.1033 | 0.253516 *** | 13.8757 |

| SEMP | 0.008706 | 0.3019 | 0.005441 | 0.1698 | 0.010804 | 0.3927 |

| C | 5.652873 *** | 18.525 | 5.705108 *** | 21.476 | 5.664736 *** | 20.478 |

| Statistic | CCR | FMOLS | DOLS |

|---|---|---|---|

| R-squared | 0.9897 | 0.9897 | 0.9906 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.9866 | 0.9866 | 0.9879 |

| S.E. of regression | 0.010229 | 0.010213 | 0.009922 |

| Long-run variance |

References

- Ameer, W.; Sohag, K.; Zhan, Q.; Shah, S.H.; Yongjia, Z. Do Financial Development and Institutional Quality Impede or Stimulate the Shadow Economy? A Comparative Analysis of Developed and Developing Countries. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mara, E.R.; Maran, R. Are Fiscal Rules Efficient on Public Debt Restraint in the Presence of Shadow Economy? Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 64, 105495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horodnic, I.A.; Williams, C.C.; Apetrei, A.; Mațcu, M.; Horodnic, A.V. Services Purchase from the Informal Economy Using Digital Platforms. Serv. Ind. J. 2023, 43, 854–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivan, A.-D.; Davidescu, A.A.; Agafiţei, M.-D.; Geambaşu, M.C. Applying Machine Learning Techniques to Estimate the Size of the Romanian Shadow Economy. Proc. Int. Conf. Bus. Excell. 2025, 19, 2525–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horodnic, I.A.; Williams, C.C.; Țugulea, O.; Stoian Bobâlcă, I.C. Exploring the Demand-Side of the Informal Economy during the COVID-19 Restrictions: Lessons from Iași, Romania. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackrill, R.; Igudia, E. Analysing the Informal Economy: Data Challenges, Research Design, and Research Transparency. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2024, 28, 1971–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, L.; Schneider, F. Shadow Economies Around the World: What Did We Learn over the Last 20 Years? IMF Working Papers; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Volume 18, p. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehn, A.; Schneider, F. Shadow Economies around the World: Novel Insights, Accepted Knowledge, and New Estimates. Int. Tax. Public Financ. 2012, 19, 139–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, N.; Rahman, M.M.; Murad, S.M.W. Asymmetric Role of the Informal Sector on Economic Growth: Empirical Investigation on a Developing Country. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2024, 69, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, E.; Katircioğlu, S.; Tecel, A. Gender Differences in the Impact of the Informal Economy on the Labor Market: Evidence From Middle Eastern Countries. Eval. Rev. 2024, 48, 865–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, F.; Enste, D.H. Shadow Economies: Size, Causes, and Consequences. J. Econ. Lit. 2000, 38, 77–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ștefoni, S.E.; Brașoveanu, I.V.; Butu, I. Social Aspects of the Informal Economy: Evidence from EU Countries. Theor. Appl. Econ. 2024, 31, 197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Gillanders, R.; Parviainen, S. Corruption and the Shadow Economy at the Regional Level. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2018, 22, 1729–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, J.; Embaye, A. Using Dynamic Panel Methods to Estimate Shadow Economies Around the World, 1984–2006. Public Financ. Rev. 2013, 41, 510–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, D.; Kraay, A. Growth without Governance. Economía 2002, 3, 169–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbahnasawy, N.G. Can E-Government Limit the Scope of the Informal Economy? World Dev. 2021, 139, 105341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedić, V.; Despotović, D.; Cvetanović, S.; Djukić, T.; Petrović, D. Institutional Reforms for Economic Growth in the Western Balkan Countries. J. Policy Model. 2020, 42, 933–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund; Dabla-Norris, E.; Koeda, J. Informality and Macroeconomic Fluctuations. In IMF Research Bulletin, December 2008; IMF Research Bulletin; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; Volume 8, p. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, C.M.; Nguyen, T.L. Fiscal Policy and Shadow Economy in Asian Developing Countries: Does Corruption Matter? Empir. Econ. 2020, 59, 1745–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgler, B.; Schneider, F.G. Shadow Economy, Tax Morale, Governance and Institutional Quality: A Panel Analysis. SSRN J. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.; Saunoris, J. Forms of Government Decentralization and Institutional Quality: Evidence from a Large Sample of Nations. In Central and Local. Government Relations in Asia; Yoshino, N., Morgan, P.J., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; pp. 395–420. [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo, A.M.; Thomas, M.; Karakurum-Ozdemir, K. Economic Informality: Causes, Costs, and Policies—A Literature Survey; World Bank Working Paper; 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.C.; Round, J. Evaluating Informal Entrepreneurs’ Motives: Evidence from Moscow. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2009, 15, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.P.; Schinckus, C.; Nguyen, Q.B.; Le Tran, D.T. Digitalization and Informal Economy: A Global Evidence of Internet Usage. J. Ind. Bus. Econ. 2024, 51, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, J.; Kamin, S.; Aguilar, A.; Guerra, R.; Tombini, A. Digital Payments, Informality and Economic Growth 2024. Available online: https://www.bis.org/publ/work1196.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Krichewsky-Wegener, L. Digital Transformation in the Informal Economy: Opportunities and Challenges for Technical and Vocational Education and Training in Development Cooperation. Available online: https://www.govet.international/en/129448.php (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Chacaltana Janampa, J.; Mattos, F.B.D.; García, J.M.; International Labour Organization. Employment Policy Department. In New Technologies, e-Government and Informality; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; ISBN 978-92-2-040568-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, O.T.; Hasan, M.A.; Saha, S.K. Resilience in the Informal Economy amidst the COVID-19 Crisis: The Experience of Street Vendors in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Urban Plan. Transp. Res. 2025, 13, 2502001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridayani, H.D.; Chiang, L.-C.; Atmojo, M.E.; Tai, K.-T. Empowering Resilience: How Digital Tools and Environmental Practices Can Foster Growth in the Informal Business Sector. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2025, 1475, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanie, M.; Frimpong, P.B.; Dramani, J.B.; Orehounig, K. The Impacts of the Informal Economy, Climate Migration, and Rising Temperatures on Energy System Planning. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, E.; Igudia, E. The Case for Mixed Methods Research: Embracing Qualitative Research to Understand the (Informal) Economy. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2024, 28, 1947–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, M.; Sekrafi, H.; Gheraia, Z.; Abdelli, H. Regulating the Unobservable: The Impact of the Environmental Regulation on Informal Economy and Pollution. Energy Environ. 2024, 35, 3463–3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nica, I.; Georgescu, I.; Delcea, C.; Chiriță, N. Toward Sustainable Development: Assessing the Effects of Financial Contagion on Human Well-Being in Romania. Risks 2023, 11, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgin, C.; Oztunali, O. Institutions, Informal Economy, and Economic Development. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2014, 50, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuong, N.V.; Shabbir, M.S.; Sial, M.S.; Khanh, T.H.T. Does Informal Economy Impede Economic Growth? Evidence from an Emerging Economy. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2021, 11, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouhessèwa Hounyonou, Q. How Does the Informal Economy Affect SDGs in Developing Countries? Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2025, 32, 589–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, A.; Ortiz, C. Exploring the Relationship between Productive Structure and the Informal Economy: Evidence from Latin American Countries. JEPP 2024, 13, 306–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyeonov, S.; Moroz, A.; Dudziuk, I.; Chuluunbaatar, E. Green Rules & Grey Markets: Do Environmental Policies Influence the Informal Economy? Econ. Sociol. 2025, 18, 313–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkadr, A.A.; Asnakew, Y.W.; Sendkie, F.B.; Workineh, E.B.; Asfaw, D.M. Analyzing the Dynamics of Monetary Policy and Economic Growth in Ethiopia: An Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) Approach. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanayo, O.; Maponya, L.; Semenya, D. Evaluating the Dynamic Effects of Environmental Taxation and Energy Transition on Greenhouse Gas Emissions in South Africa: An Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwaindepi, A. Taxation in the Context of High Informality: Conceptual Challenges and Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2025, 29, 1228–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Anno, R. Integrating National Accounting and Macroeconomic Approaches to Estimate the Underground, Informal, and Illegal Economy in European Countries. Int. Tax. Public Financ. 2025, 32, 526–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiafe, P.A.; Armah, M.; Ahiakpor, F.; Tuffour, K.A. The Underground Economy and Tax Evasion in Ghana: Implications for Economic Growth. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2024, 12, 2292918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polese, A.; Moisé, G.M.; Tokyzhanova, T.; Aguzzi, T.; Kerikmäe, T.; Sagynbaeva, A.; Sauka, A.; Seliverstova, O. Informality versus Shadow Economy: Reflecting on the First Results of a Manager’s Survey in Kyrgyzstan. Cent. Asian Surv. 2023, 42, 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgin, C.; Kose, A.; Ohnsorge, F.; Yu, S. Understanding Informality. 2021. Available online: https://cepr.org/publications/dp16497 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- World Bank Inflation, Consumer Prices (Annual %) 2025. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FP.CPI.TOTL.ZG (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- International Monetary Fund Primary Net Lending/Borrowing (Also Referred as Primary Balance) % of GDP 2025. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/GGXONLB_G01_GDP_PT@FM/ADVEC/FM_EMG/FM_LIDC/ROU (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- World Bank Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism: Percentile Rank 2025. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/PV.PER.RNK (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- World Bank Interest Payments (% of Revenue) 2025. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/GC.XPN.INTP.RV.ZS (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- World Bank GDP per Capita (Constant 2015 US$) 2025. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Jordà, Ò. Estimation and Inference of Impulse Responses by Local Projections. Am. Econ. Rev. 2005, 95, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgin, C.; Oztunali, O. Shadow Economies around the World: Model Based Estimates 2012. Available online: https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:bou:wpaper:2012/05 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Ihrig, J.; Moe, K.S. Lurking in the Shadows: The Informal Sector and Government Policy. J. Dev. Econ. 2004, 73, 541–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgin, C.; Kose, A.; Ohnsorge, F.; Yu, S. Shades of Grey: Measuring the Informal Economy Business Cycles 2019. Available online: https://www.imf.org/-/media/files/conferences/2019/7th-statistics-forum/session-ii-yu.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Copaciu, M.; Nalban, V.; Bulete, C. REM, 2.0, An Estimated DSGE Model for Romania. In Proceedings of the 11th Dynare Conference, Brussels, Belgium, 28–29 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lütkepohl, H.; Xu, F. The Role of the Log Transformation in Forecasting Economic Variables. Empir. Econ. 2012, 42, 619–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lütkepohl, H. New Introduction to Multiple Time Series Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; ISBN 978-3-540-40172-8. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.J. Bounds Testing Approaches to the Analysis of Level Relationships. J. Appl. Econom. 2001, 16, 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H. An Autoregressive Distributed-Lag Modelling Approach to Cointegration Analysis. In Econometrics and Economic Theory in the 20th Century: The Ragnar Frisch Centennial Symposium; Strøm, S., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 371–413. ISBN 978-0-521-63323-9. [Google Scholar]

- Xuan, V.N. An ARDL Approach to Investigating the Relationship between FDI, Renewable Energy, Economic Growth, Trade Openness, and CO2 Emissions in Australia. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 105668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkoro, E.; Uko, K. Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) Cointegration Technique: Application and Interpretation. J. Stat. Econom. Methods 2016, 5, 63–91. [Google Scholar]

- Delcea, C.; Nica, I.; Georgescu, I.; Chiriță, N.; Ciurea, C. Integrating Fuzzy MCDM Methods and ARDL Approach for Circular Economy Strategy Analysis in Romania. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, I.; Nica, I.; Delcea, C.; Chiriță, N.; Ionescu, Ș. Assessing Regional Economic Performance in Romania Through Panel ARDL and Panel Quantile Regression Models. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y. Canonical Cointegrating Regressions. Econometrica 1992, 60, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P.C.B.; Hansen, B.E. Statistical Inference in Instrumental Variables Regression with I(1) Processes. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1990, 57, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, J.H.; Watson, M.W. A Simple Estimator of Cointegrating Vectors in Higher Order Integrated Systems. Econometrica 1993, 61, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund. IMF Research Bulletin, December 2008; IMF Research Bulletin; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; Volume 9, p. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, C.M.; Nguyen, T.L. Shadow Economy and Income Inequality: New Empirical Evidence from Asian Developing Countries. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2020, 25, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, D.A.; Fuller, W.A. Distribution of the Estimators for Autoregressive Time Series with a Unit Root. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1979, 74, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoc, X.V. Determinants of Open Innovation in United State of America: New Evidence from ARDL Method. Innov. Green. Dev. 2025, 4, 100228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nica, I.; Georgescu, I.; Kinnunen, J. Evaluating Renewable Energy’s Role in Mitigating CO2 Emissions: A Case Study of Solar Power in Finland Using the ARDL Approach. Energies 2024, 17, 4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevik, S.; Miryugin, F. It’s Never Different: Fiscal Policy Shocks and Inflation; IMF Working Papers; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; ISBN 979-8-4002-4287-8. [Google Scholar]

- Sungurtekin Hallam, B. Emerging Market Responses to External Shocks: A Cross-Country Analysis. Econ. Model. 2022, 115, 105948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte The Digitalization Marathon: Implementing SAF-T in Romania. Available online: https://www.deloitte.com/ro/ro/services/tax/services/maratonul-digitalizarii-implementarea-saf-t-in-romania.html (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- European Commission eInvoicing in Romania. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-building-blocks/sites/spaces/DIGITAL/pages/467108898/eInvoicing+in+Romania (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- PricewaterhouseCoopers Romania: Corporate—Tax Administration. Available online: https://taxsummaries.pwc.com/romania/corporate/tax-administration (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- OECD. Tax Administration 2025: Comparative Information on OECD and Other Advanced and Emerging Economies; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025; ISBN 978-92-64-55706-2. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund ROMANIA—TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE REPORT ON IMPROVING REVENUES FROM THE RECURRENT PROPERTY TAX 2022. Available online: https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/CR/2022/English/1ROUEA2022001.ashx (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Kommission, E. (Ed.) 2023 Country Report Romania; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023; ISBN 978-92-68-03214-5. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2765/34357 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Kinnunen, J.; Georgescu, I.; Hosseini, Z.; Androniceanu, A.-M. Dynamic Indexing and Clustering of Government Strategies to Mitigate COVID-19. EBER 2021, 9, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing, E.; Van Stel, A.; Storey, D.J. Formal and Informal Entrepreneurship: A Cross-Country Policy Perspective. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 59, 807–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loayza, N.; Serven, L.; Sugawara, N. Informality in Latin America and the Caribbean. World Bank Policy Res. Work. Pap. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Enste, D. The Shadow Economy in Industrial Countries. IZA World Labor 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.C.; Horodnic, I.A. Explaining the Informal Economy in Post-Communist Societies: A Study of the Asymmetry Between Formal and Informal Institutions in Romania. In The Informal Economy in Global Perspective; Polese, A., Williams, C.C., Horodnic, I.A., Bejakovic, P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 117–140. ISBN 978-3-319-40930-6. [Google Scholar]

- Asllani, A.; Schneider, F. A Review of the Driving Forces of the Informal Economy and Policy Measures for Mitigation: An Analysis of Six EU Countries. Int. Tax. Public Financ. 2025, 32, 310–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, C.; Hassan, F.A.; Antohi, V.M.; Ahmad, W.; Fortea, C.; Cristache, N.; Alshammari, F.; Zlati, M.L. Informal Economy and Environmental Degradation in Developing Countries: The Conditioning Role of Institutional Quality. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1645194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loayza, N.V. The Economics of the Informal Sector: A Simple Model and Some Empirical Evidence from Latin America. Carnegie-Rochester. Conf. Ser. Public Policy 1996, 45, 129–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.C.; Schneider, F. Measuring the Global Shadow Economy: The Prevalence of Informal Work and Labour; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Acronym | Measurement Unit | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic general equilibrium model-based (DGE) estimates of informal output | DGE | % of official GDP | World Bank [45] |

| Inflation, consumer prices, annual | INF | % | World Bank [46] |

| Primary net lending/borrowing (also referred as primary balance) | NLB | % of GDP | International Monetary Fund [47] |

| Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism | PSI | [0, 100] | World Bank [48] |

| Interest payments (% of revenue) | INTPAY | % | World Bank [49] |

| Gross domestic product per capita | GDP | Constant 2015 USD | World Bank [50] |

| Self-employment (% of total employment) | SEMP | % | World Bank [45] |

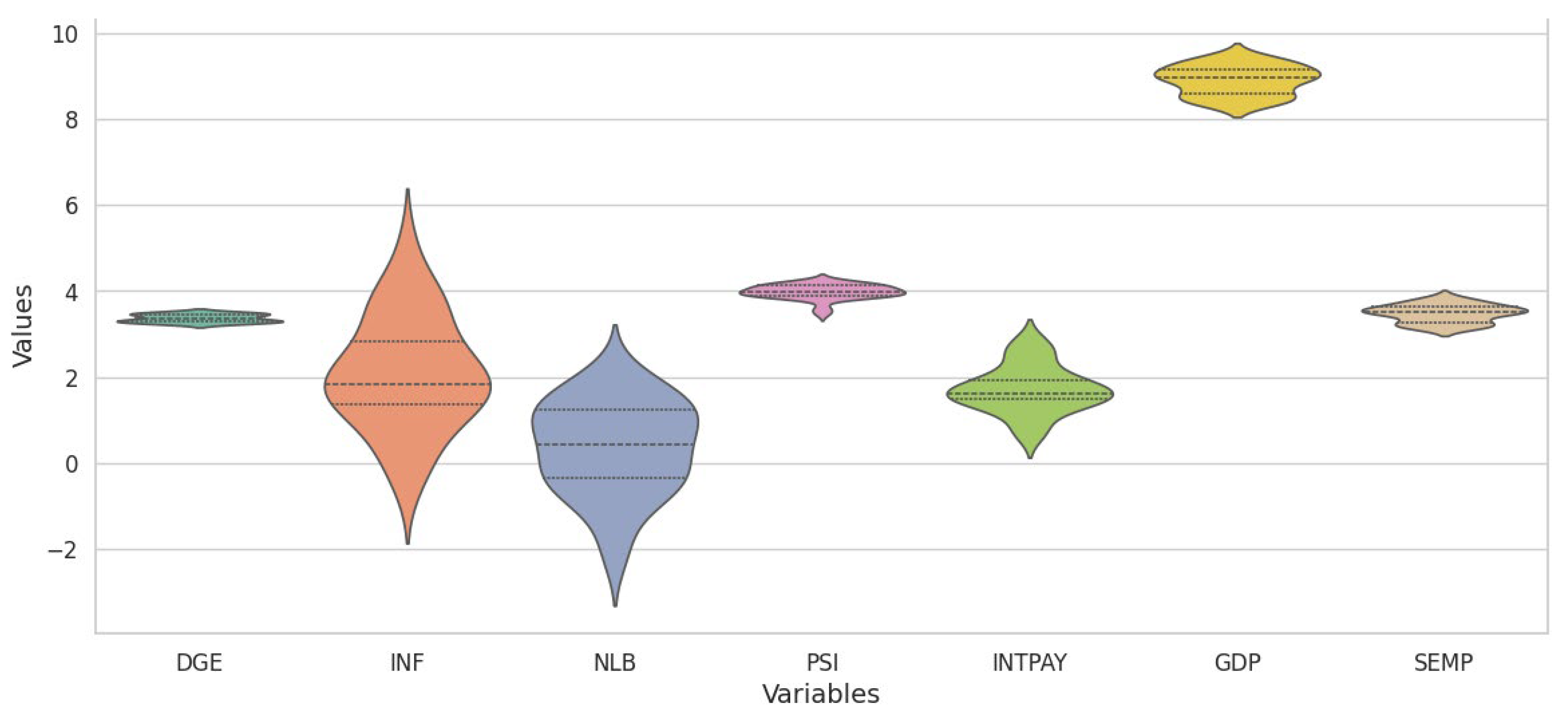

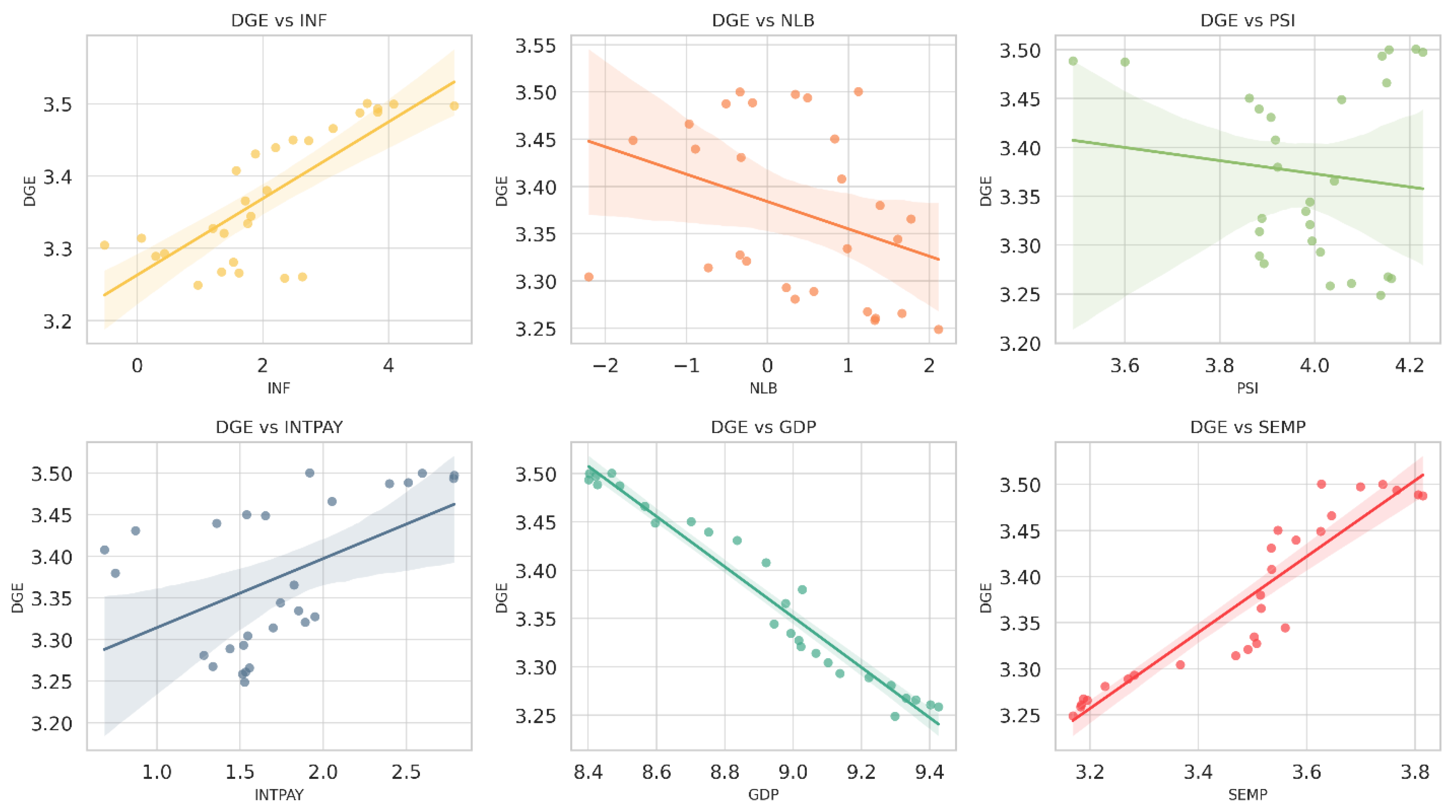

| DGE | INF | NLB | PSI | INTPAY | GDP | SEMP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 3.37386 | 2.091725 | 0.350445 | 3.987286 | 1.717855 | 8.91407 | 3.48348 |

| Median | 3.354971 | 1.843822 | 0.419143 | 3.991886 | 1.603157 | 8.985257 | 3.514817 |

| Maximum | 3.500589 | 5.041898 | 2.110213 | 4.22761 | 2.787912 | 9.425371 | 3.813962 |

| Minimum | 3.248898 | −0.520613 | −2.207275 | 3.490558 | 0.683352 | 8.401509 | 3.168301 |

| Std. Dev. | 0.090106 | 1.310409 | 1.082861 | 0.168541 | 0.541786 | 0.337954 | 0.20327 |

| Skewness | 0.13338 | 0.207701 | −0.449477 | −1.072122 | 0.263207 | −0.17715 | −0.185139 |

| Kurtosis | 1.472287 | 2.678119 | 2.534345 | 4.503594 | 2.878114 | 1.764363 | 1.938325 |

| Jarque–Bera | 2.805912 | 0.322194 | 1.195779 | 8.001674 | 0.34063 | 1.927716 | 1.474971 |

| Probability | 0.245869 | 0.851209 | 0.549971 | 0.0183 | 0.843399 | 0.381419 | 0.478315 |

| Variables | Level | First Difference | Order of Integration at 5% L.O.S. |

|---|---|---|---|

| T-Statistics | T-Statistics | ||

| DGE | −0.60 (0.854) | −4.05 *** (0.004) | I (1) |

| INF | −1.54 (0.497) | −6.23 *** (0.000) | I (1) |

| NLB | −2.60 (0.103) | −6.35 *** (0.000) | I (1) |

| PSI | −3.61 ** (0.012) | −5.93 *** (0.00)) | I (0) |

| INTPAY | −2.41 (0.148) | −5.39 *** (0.000) | I (1) |

| GDP | 0.10 (0.960) | −4.05 *** (0.004) | I (1) |

| SEMP | 0.03 (0.954) | −4.66 *** (0.001) | I (1) |

| Lag | LogL | LR | FPE | AIC | SC | HQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 56.43 | N/A | 3.80 | 3.46 | 3.70 | |

| 1 | 212.78 | 216.48 | 12.06 | 9.35 | 11.28 | |

| 2 | 301.19 | 74.80 * | * | 15.09 * | 10.01 * | 13.62 * |

| Test Statistic | Value | K (Number of Regressors) |

|---|---|---|

| F-Statistic | 5.76 | 6 |

| Critical value bounds | ||

| Significance | I (0) | I (1) |

| 10% | 1.99 | 2.94 |

| 5% | 2.27 | 3.28 |

| 1% | 2.88 | 3.99 |

| Variables | Coefficient | T-Statistics | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|

| INF | 0.03 | 4.01 | 0.005 *** |

| NLB | 0.02 | 2.50 | 0.040 ** |

| PSI | 0.12 | 2.31 | 0.053 * |

| INTPAY | 0.07 | 5.39 | 0.001 *** |

| GDP | 0.29 | 10.42 | 0.000 *** |

| SEMP | 0.18 | 2.19 | 0.064 * |

| C | 7.19 | 10.58 | 0.00 *** |

| Variables | Coefficient | T-Statistics | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|

| D (DGE (−1)) | 0.70 | 6.29 | 0.00 *** |

| D (INF) | 0.01 | 7.19 | 0.00 *** |

| D (INF (−1)) | −0.01 | −4.23 | 0.00 *** |

| D (NLB) | −0.01 | −9.59 | 0.00 *** |

| D (PSI) | −0.05 | −7.73 | 0.00 *** |

| D (PSI (−1)) | 0.03 | 5.02 | 0.00 *** |

| D (INTPAY) | 0.04 | 6.87 | 0.00 *** |

| D (INTPAY (−1)) | 0.02 | 4.30 | 0.00 *** |

| D (GDP) | 0.07 | 2.09 | 0.07 * |

| D (GDP (−1)) | −0.31 | −13.39 | 0.00 *** |

| D (SEMP) | −0.02 | −1.22 | 0.26 |

| CointEq (−1) | −0.79 | −9.60 | 0.00 *** |

| Validation Metrics | |||

| R-squared | 0.93 | ||

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.88 | ||

| Durbin–Watson stat | 2.55 | ||

| Akaike info criterion | −8.30 | ||

| Schwarz criterion | −7.72 | ||

| Hannan–Quinn criterion | −8.13 | ||

| Diagnostic Test | Decision Statistics [p-Value] | |

|---|---|---|

| SERIAL | There is no serial correlation in the residuals. | 2.52 [0.175] |

| ARCH | There is no autoregressive conditional heteroscedasticity. | 0.001 [0.971] |

| Jarque–Bera | Normal distribution | 0.76 [0.683] |

| Ramsey | Absence of model misspecification. | 1.21 [0.263] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Georgescu, I.; Nica, I.; Chiriță, N.; Kinnunen, J. Economic Dynamics of Informal Output in Romania: An ARDL Approach to Policy, Growth, and Institutional Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10920. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410920

Georgescu I, Nica I, Chiriță N, Kinnunen J. Economic Dynamics of Informal Output in Romania: An ARDL Approach to Policy, Growth, and Institutional Sustainability. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):10920. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410920

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeorgescu, Irina, Ionuț Nica, Nora Chiriță, and Jani Kinnunen. 2025. "Economic Dynamics of Informal Output in Romania: An ARDL Approach to Policy, Growth, and Institutional Sustainability" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 10920. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410920

APA StyleGeorgescu, I., Nica, I., Chiriță, N., & Kinnunen, J. (2025). Economic Dynamics of Informal Output in Romania: An ARDL Approach to Policy, Growth, and Institutional Sustainability. Sustainability, 17(24), 10920. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410920