Blue–Green Infrastructure Strategies for Improvement of Outdoor Thermal Comfort in Post-Socialist High-Rise Residential Areas: A Case Study of Niš, Serbia

Abstract

1. Introduction

- First, intensifying urbanization and densification have replaced permeable, shaded ground with hard, impervious surfaces, increasing runoff, suppressing evapotranspiration, and exacerbating the UHI effect [20]. The result is heightened exposure to heat stress and reduced opportunities for recreation and physical activity—impacts expected to worsen under climate change [21,22].

- Second, the transition from state-planned to market-oriented development after 1990 replaced long-range urban strategies with opportunity-led densification and privatization of formerly public land [23,24]. In the city of Niš, green areas within HRHAs have frequently been converted into construction land, while post-2000 General Regulation Plans stipulated a minimum of only 10% on-plot greenery [25]. Consequently, many post-socialist HRHAs have become predominantly “gray”, with green-space provision dropping to ~1.2 m2 per inhabitant—far below both the ~38.6% share recorded in socialist-era HRHAs and international norms of 20–40 m2 per resident [26].

- Third, fragmented development amid prolonged political and economic crises disrupted comprehensive planning reform. Developers often pursued plot-by-plot infill construction, maximizing yield while neglecting public interest and omitting OSs [27,28,29,30,31]. In the Municipality of Medijana (Niš), new residential blocks provide only ~0.34 m2 of green space per inhabitant (≈8.66% of the ground area), falling short of the prescribed 10% minimum [32]. The HRHA on Romanijska Street in Niš—an infill development within the Krivi Vir neighborhood—illustrates this pattern, with most surfaces paved and green coverage limited to ≈4.3% of the plot (~0.27 m2 per resident). Such conditions create a microclimatic environment conducive to strong UHI expression and thermal stress.

- Quantify air temperature (Ta), mean radiant temperature (Tmrt), wind speed, relative humidity, and PET under heatwave conditions;

- Test the cooling performance of four incremental surface-cover scenarios—S0 (concrete baseline), S1 (grass), S2 (grass plus deciduous trees), and S3 (S2 plus a ~40 m2 shallow reflecting pool);

- Formulate context-specific, cost-effective design recommendations for improving OTC in OSs in post-socialist HRHAs.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Outdoor Thermal Comfort Indices

2.2. Microclimate Simulation of OSs in HRHAs and the Cooling Performance of BGI

- Vegetation: Meta-analyses suggest that every 10% increase in canopy cover can reduce Tmrt by 4–6 °C and PET by 1–2 °C during mid-afternoon [79]. Even modest green areas can cool by 1–3 °C relative to paved surfaces; tree planting consistently reduces maximum air and surface temperatures, achieving average PET reductions of approximately 13% compared with existing vegetation [69].

- Albedo and permeability: Bright, permeable pavements operate 8–12 °C cooler than asphalt under direct sun; however, their PET impact is secondary when the sky-view factor (SVF) falls below ~0.35. Impervious pavements may reach 12–15 °C higher surface temperatures than adjacent grassed or tree-shaded zones, particularly under dense summer conditions [82].

2.3. The Western Balkan Evidence Gap

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Climate Conditions and Study Area

Selection of HRHA for Case Study

- Site coverage index: 0.43 (buildings occupy 43% of the parcel);

- Floor-area ratio (FAR): 3.27 (very high built intensity);

- Population density: extremely high (site-specific figures withheld for confidentiality).

3.2. Field Study, Measurement Indicators, and Instruments

3.2.1. Outdoor Microclimate Measurements

- P1—Central paved OS above the underground garage (no vegetation or equipment). Located in the geometric center, flanked by 8-story residential blocks on two long sides; the southwest short side hosts two single-story commercial buildings, while the northeast side remains largely undeveloped. As in many HRHA courtyards in Niš, occasional informal parking on the southeast margin further degrades the microclimate (heated vehicle masses and tailpipe emissions).

- P2—Asphalt parking area (southeast of R2, above the second underground garage). Originally conceived as part of the communal OS connected to the greenery along the Gabrovačka River, the area has been repurposed for parking.

- P3—The only larger lawn (northeastern sector). A small but critical grassed patch representing the sole sizeable permeable and vegetated surface within the courtyard.

- P4—Narrow paved corridor between R1, R2, and a commercial unit (no vegetation). A linear, high-aspect-ratio passage with limited sky view, analogous to P1 in its lack of vegetation.

3.2.2. Built-Environment Documentation

3.3. ENVI-Met Model Setup

3.4. Definition of the Project Scenarios

- S0—Base case: Existing condition with continuous concrete/asphalt paving, except for a ~420 m2 lawn above the garage at P3 and a ~30 m2 lawn in front of commercial building C2.

- S1—Grass: Replacement of selected paved areas by lawn over the ground-level slab of the underground garage between and in front of R1 and R2, focusing on P1 and P4.

- S2—Grass + Deciduous Trees: Scenario S1 plus deciduous canopy trees positioned on the ground-level slab of the underground garage (in load-appropriate planting pits), primarily around P1 and P4 and between R1 and R2.

- S3—S2 + Shallow Reflecting Pool: Scenario S2 augmented with a ~40 m2 shallow reflecting pool located on the ground-level slab of the underground garage near P1.

4. Results

4.1. Validation

4.2. Overview of Microclimatic Parameters and PET Values of Individual Parts of OS Scenario S0—Existing State

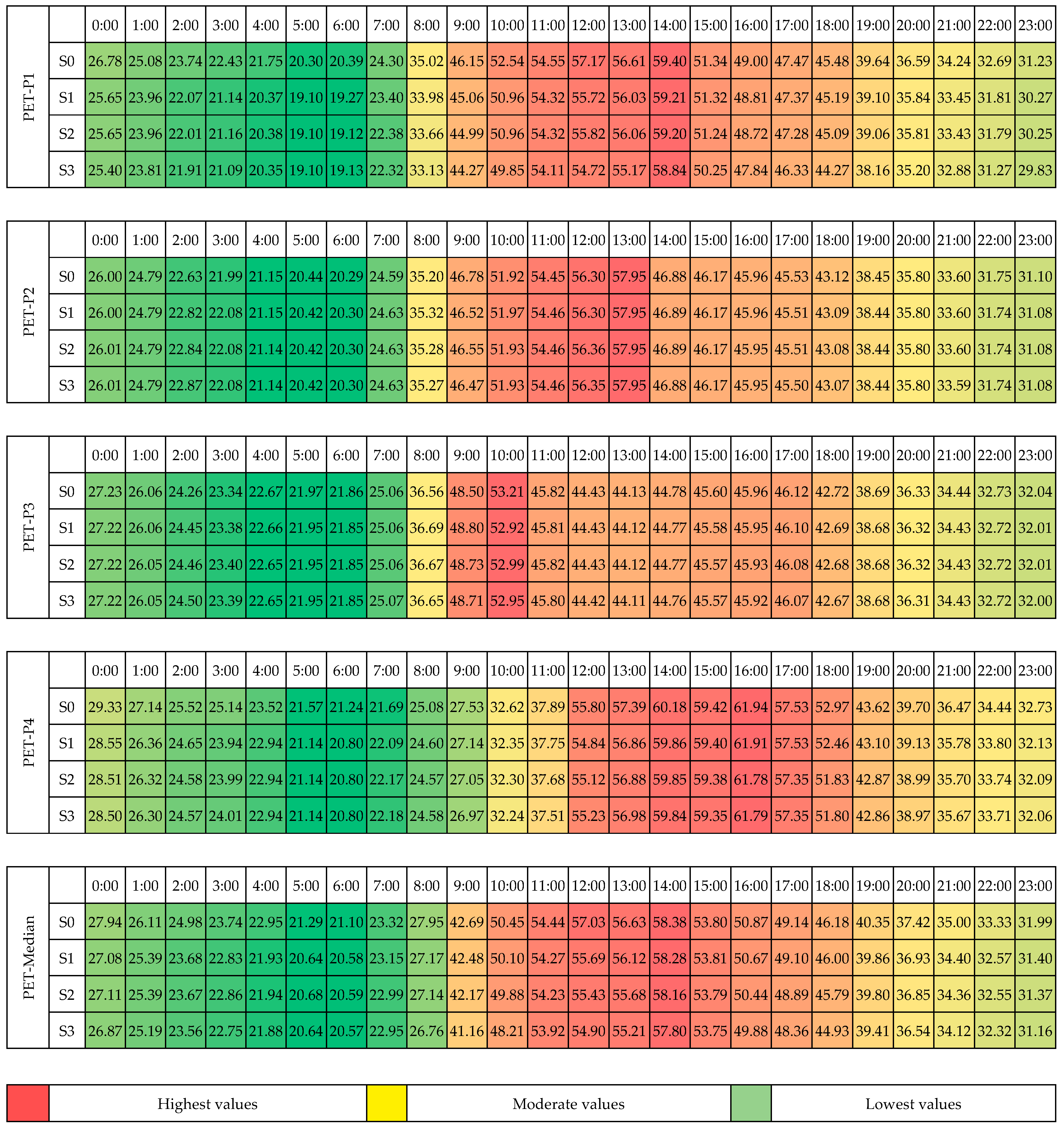

- At observation point P1, PAT decreased between 00:00 and 07:00 h, then rose to its maximum at 15:00 h. The PET curve generally followed this trend, with the lowest PAT occurring one hour after the most comfortable period. An inverse relationship was observed between PET and RH. Surrounding buildings and paved surfaces re-emitted stored heat, while the lack of ventilation contributed to PET rising starting at 05:00 h and reaching a relatively high maximum at 14:00 h. Despite façade shading after 15:00 h, thermal relief remained insufficient. Acceptable comfort occurred only between 00:00 and 03:00 and at 07:00 h, while pleasant conditions were limited to 03:00–06:00 h. By late evening (23:00 h), PET remained around 30.89 °C.

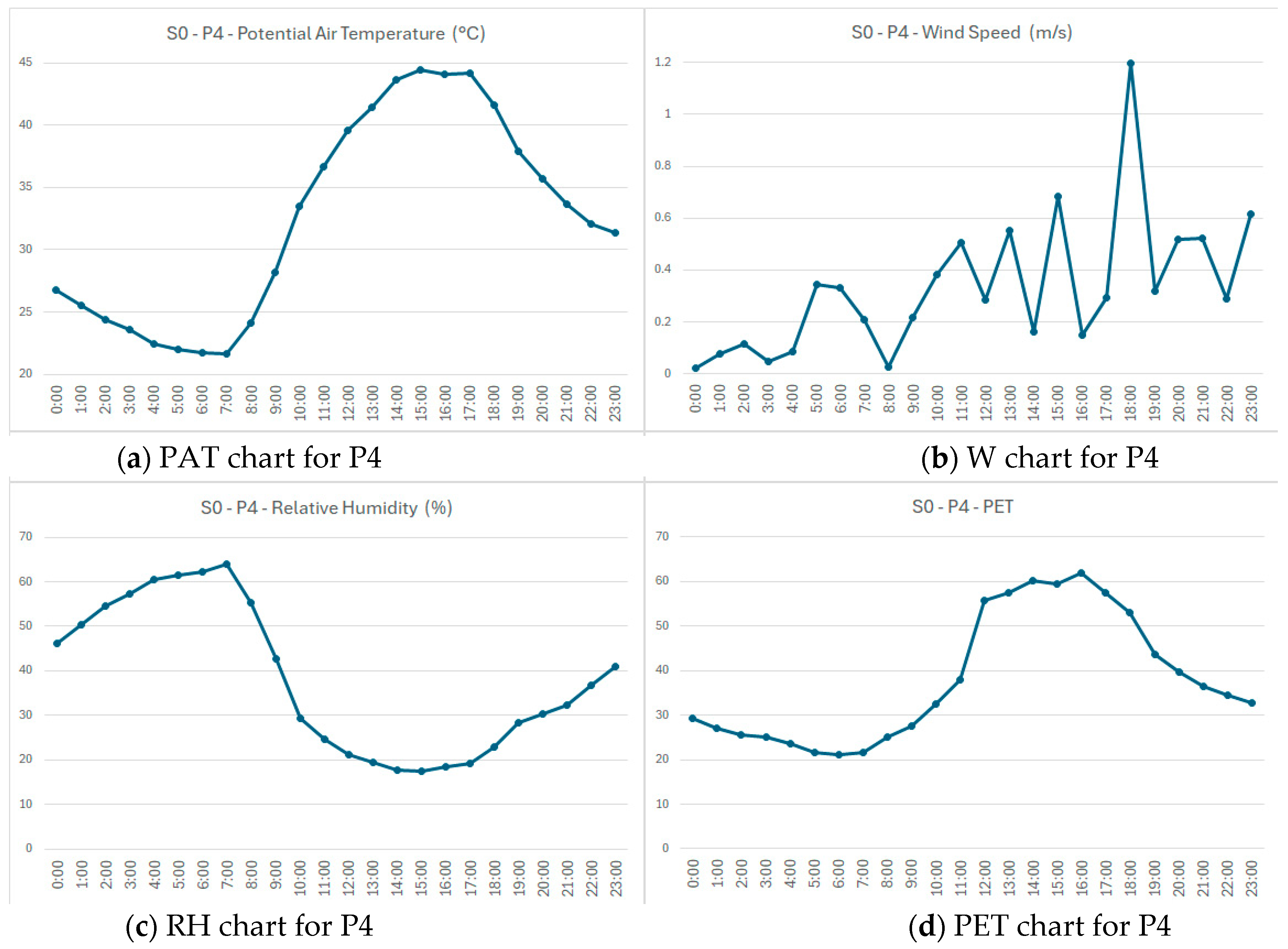

- At observation point P4, similar diurnal dynamics of PAT and RH were observed, with minor magnitude differences. The minimum PET occurred one hour earlier, while the maximum PET of 61.94 °C—the highest of all points—occurred one hour later than the maximum PAT. Due to limited air movement and strong heat accumulation caused by the enclosed geometry, OTC remained poor despite shading between 11:00 and 17:00–18:00 h. Pleasant comfort occurred only between 05:00 and 07:00 h.

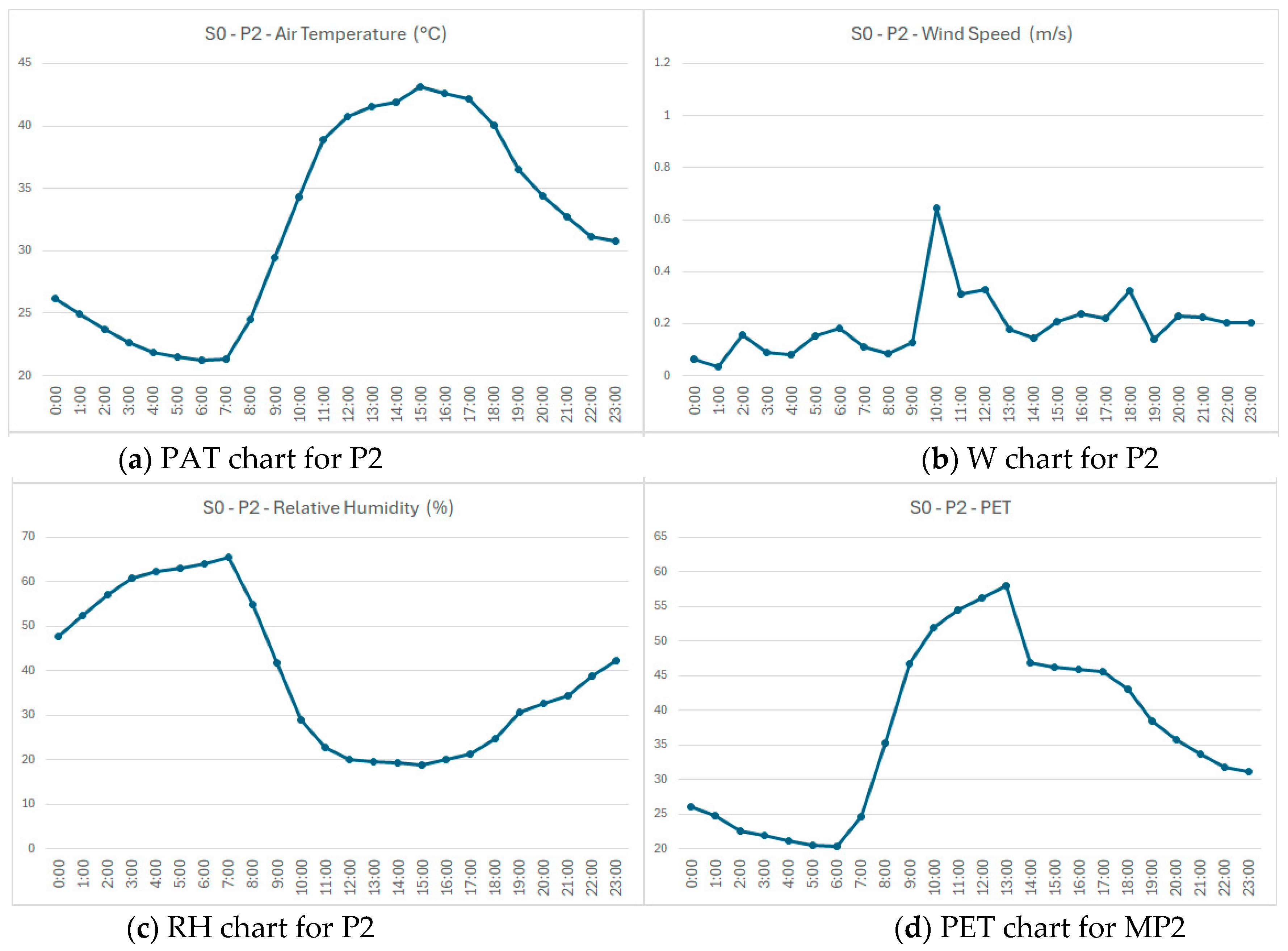

- At observation points P2 and P3, PAT decreased between 00:00 and 06:00 h and peaked at 15:00 h, with negligible differences between these two locations. RH varied inversely with PAT:

- At P2, PET decreased from 00:00 to 06:00 h and reached its maximum at 13:00 h—two hours earlier than the PAT peak—due to heat release from dark asphalt.

- At P3, PET also decreased from 00:00 to 06:00 h and peaked at 53.21 °C at 10:00 h, which is 4–6 °C lower than the maxima at P1 and P2. This early peak reflected the dry, easternly oriented lawn lacking shade, with relatively low RH and weak ventilation (low W). Pleasant comfort occurred between 04:00 and 06:00 h, and acceptable comfort was confined to the hours of 00:00–04:00 h and 07:00 h.

4.3. Overview of Microclimate Parameters and PET Values of Scenarios of Individual Parts of OS

- In Scenario S1, PAT followed a similar trend as in S0, being up to 1.2 °C lower in early morning and up to 0.9 °C higher at mid-day. PET values were slightly reduced—by less than 1.67 °C—compared to S0. Neither the presence of lawn nor façade shading after 15:00 h substantially improved OTC, which remained pleasant or acceptable only from 00:00 to 07:00 h, as in S0.

- In Scenario S2, PAT, RH, and W differed negligibly from S0, with PET reduced by about 1.2 °C only during early-morning hours, which was insufficient to improve daytime comfort. Pleasant or acceptable comfort persisted only from 00:00 to 07:00 h.

- In scenario S3, PAT and W differed minimally from S0, RH varied by up to 3.65%, and PET values were slightly lower—by up to 2.68 °C at 10:00 h. As in S0, shading after 15:00 h failed to bring conditions to acceptable levels; comfort remained confined to early-morning hours (00:00–07:00 h).

- In the base case (S0), PAT and PET both decreased during early-morning hours (07:00 h and 06:00 h, respectively). PET began rising one hour earlier and declined one hour later than PAT. The maximum PET of 61.94 °C occurred at 16:00 h, coinciding with minimum RH. Pleasant OTC occurred only between 05:00 and 07:00 h, and acceptable comfort only occurred during the periods of 01:00–04:00 h and 07:00–09:00 h.

- In scenarios S1 and S2, all parameters differed negligibly from S0. PET reductions were below 1 °C, and building shading in the morning did not improve OTC to acceptable levels.

- In scenario S1, OTC was pleasant from 04:00 to 07:00 h and acceptable during the hours of 00:00–04:00 h and 07:00–09:00 h.

- In Scenario S2, pleasant OTC occurred from 04:00 to 07:00 h, and acceptable OTC occurred during the hours of 00:00–04:00 h and 08:00–10:00 h.

5. Discussion

5.1. Synthesis of Key Findings

5.2. Suggestions for Planning and Design

- Tree canopy coverage should be prioritized in OSs where ventilation is less obstructed and shading can be timed to daily peak periods;

- Interventions in enclosed canyons (e.g., P4) are unlikely to provide substantial relief unless combined with structural or ventilation improvements;

- Grass and shallow water features offer only marginal cooling in deeply enclosed courtyards dominated by thermal storage and radiative trapping.

5.2.1. What the Study Supports (Evidence-Based)

- Remove dark asphalt from paved areas (P2-type surfaces)—In S0, dark asphalt advanced and amplified PET peaks relative to air-temperature peaks at P2; replacing small asphalt patches with lawn (S1) yielded ≤1.7 °C PET reductions at P1 but did not improve afternoon comfort (13:00–16:00 h).

- 2.

- Specify light-colored, low-heat-storage finishes on ground-level slabs of underground garage areas (P1/P4)—At P1, high thermal storage suppressed evening cooling; even in S3, afternoon PET remained within “strong–extreme” heat-stress classes.

- 3.

- Align shade with the daily peak (13:00–16:00 h)—In S2–S3, canopy shade arrived too late to mitigate the peak; PET reductions at P1 were ≤1.2 °C in early morning and ≤0.6 °C near the peak.

- 4.

- Small reflecting pools offer modest off-peak relief only—The ~40 m2 pool in S3 produced the largest observed reduction at P1 (ΔPET = 2.68 °C at 10:00 h) but did not change the afternoon heat-stress class.

- 5.

- Operational window for use—Across S0–S3, pleasant/acceptable OTC occurs mainly during the hours of 04:00–07:00 h; evenings retain heat due to storage, especially in narrow canyons (P4, PET max = 61.9 °C at 16:00 h).

5.2.2. What the Study Cannot Prescribe (Not Tested Here and Requires Further Research)

- Building height/spacing and plot coverage—Although results show that enclosure and radiative trapping drive overheating (e.g., P4), the study did not vary H/W, SVF, building spacing, or coverage.

- Minimum canopy coverage targets—While timing of shade is critical, the study did not investigate canopy fraction/continuity.

- Permeability of structural ground-level slabs above underground garages—The study assessed only small lawn patches placed on the structural slab but did not test fully permeable or hybrid permeable drainage systems. Such solutions typically require substantial capital investment, structural reinforcement, and long-term maintenance capacities that exceed current economic conditions in Serbian HRHA estates.

- Ventilation corridors—No openings, perforations, or spatial realignments were modeled to modify the prevailing wind paths. Although ventilation corridors can meaningfully improve courtyard airflow, their implementation generally entails major structural interventions, property consolidation, and significant financial resources—conditions not aligned with current economic and institutional capacities in Serbia.

5.3. Future Research Directions

- Multi-seasonal evidence: Extend field campaigns beyond heatwaves to cover spring–autumn (including shoulder seasons) and night-time periods, capturing humidity/radiation–wind co-variability and storage-release cycles that shape PET diurnals.

- Human perception and exposure: Pair microclimate measurements with on-site thermal sensation votes (TSVs), short exposure diaries, and observations of adaptive behaviors (e.g., shade seeking and timing of stay) to relate PET shifts to perceived comfort and plausible health risk.

- Parametric morphology tests: Systematically vary height–width ratios, the sky-view factor, building spacing/orientation, and canopy coverage/continuity to identify thresholds that move PET out of strong/extreme classes during the hours of 13:00–16:00 h (e.g., minimum SVF or canopy fraction for peak-hour relief).

- Ventilation and permeability levers: Evaluate ventilation-corridor geometries (openings and alignments) and the permeability underground garage-compatible slabs (substrate depth, porous systems) to quantify combined effects on afternoon PET under prevailing wind regimes.

- Regional transferability: Replicate the measurement–validation workflow across multiple western Balkan estates to derive context-specific benchmarks and planning targets suitable for regulation and design briefs.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

Appendix A

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | PAT | PET | PAT | PET | PAT | PET | PAT | PET |

| (h) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 0.00 | ||||||||

| 1.00 | ||||||||

| 2.00 | ||||||||

| 3.00 | Fall on 21.24 | Fall on 20.29 | Fall on 21.24 | |||||

| 4.00 | Fall on 21.57 | Fall on 20.30 | Fall on 21.30 | Fall on 21.85 | Fall on 21.68 | |||

| 5.00 | ||||||||

| 6.00 | ||||||||

| 7.00 | ||||||||

| 8.00 | Rise on 53.21 | |||||||

| 9.00 | max | |||||||

| 10.00 | Rise on 57.95 | |||||||

| 11.00 | Rise on 43.57 | Rise on 43.17 | max | |||||

| 12.00 | max | Rise on 59.40 | max | Rise on 42.90 | Rise on 44.43 | Rise on 61.94 | ||

| 13.00 | max | max | max | max | ||||

| 14.00 | ||||||||

| 15.00 | ||||||||

| 16.00 | ||||||||

| 17.00 | ||||||||

| 18.00 | ||||||||

| 19.00 | ||||||||

| 20.00 | Fall on 31.10 | Fall on 32.04 | Fall on 31.36 | Fall on 32.73 | ||||

| 21.00 | Fall on 30.80 | Fall on 30.87 | ||||||

| 22.00 | Fall on | Fall on 31.23 | ||||||

| 23.00 | 30.89 | |||||||

|

|

|

| |||||

| S0 | S1 | S2 | S3 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | PAT | PET | ∆PET | PAT | PET | ∆PET | PAT | PET | ∆PET | PAT | PET | ∆PET |

| (h) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 0.00 | ||||||||||||

| 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 2.00 | ||||||||||||

| 3.00 | Fall on | (0.5 h) | Fall on | Fall on | (0.5 h) | Fall on | ||||||

| 4.00 | Fall on | 19.10 | −1.2 | 20.94 | 19.10 | −1.20 | 19.10 | (0.5 h) | ||||

| 5.00 | Fall on | 20.3 | Fall on | Fall on | −1.20 | |||||||

| 6.00 | 21.57 | 20.98 | 20.93 | |||||||||

| 7.00 | ||||||||||||

| 8.00 | ||||||||||||

| 9.00 | ||||||||||||

| 10.00 | Rise on | Rise on | ||||||||||

| 11.00 | Rise on | Rise on | 59.21 | 59.20 | (14 h) | Rise on | ||||||

| 12.00 | 59.40 | 44.05 | max | (14 h) | Rise on | max | −0.20 | 58.84 | ||||

| 13.00 | Rise on | max | −0.19 | 44.01 | Rise on | max | (14 h) | |||||

| 14.00 | 43.57 | 43.86 | −0.56 | |||||||||

| 15.00 | ||||||||||||

| 16.00 | ||||||||||||

| 17.00 | ||||||||||||

| 18.00 | ||||||||||||

| 19.00 | ||||||||||||

| 20.00 | ||||||||||||

| 21.00 | Fall on | Fall on | Fall on | (23 h) | Fall on | Fall on | (23 h) | Fall on | Fall on | (23 h) | ||

| 22.00 | 30.89 | Fall on | 30.74 | 30.26 | −0.96 | 30.73 | 30.25 | −0.98 | 30.73 | 29.83 | −1.40 | |

| 23.00 | 31.23 | |||||||||||

|

|

|

| |||||||||

| S0 | S1 | S2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | PAT | PET | ∆PET | PAT | PET | ∆PET | PAT | PET | ∆PET |

| (h) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 0.00 | |||||||||

| 1.00 | |||||||||

| 2.00 | |||||||||

| 3.00 | Fall on | Fall on | (0.6 h) | Fall on | (0.6 h) | ||||

| 4.00 | Fall on | 21.24 | Fall on | 20.80 | Fall on | 20.80 | |||

| 5.00 | 21.68 | 21.42 | −0.436 | 21.41 | |||||

| 6.00 | −0.436 | ||||||||

| 7.00 | |||||||||

| 8.00 | |||||||||

| 9.00 | |||||||||

| 10.00 | |||||||||

| 11.00 | Rise on | Rise on 44.88 | Rise on 44.84 | ||||||

| 12.00 | 44.43 | Rise on | max | Rise on 61.91 | max | Rise on 61.78 | |||

| 13.00 | max | 61.94 | max | (16.0 h) | max | (16 h) | |||

| 14.00 | max | −0.037 | −0.163 | ||||||

| 15.00 | |||||||||

| 16.00 | |||||||||

| 17.00 | |||||||||

| 18.00 | |||||||||

| 19.00 | |||||||||

| 20.00 | Fall on | Fall on | Fall on | Fall on | (23 h) | Fall on | Fall on | (23 h) | |

| 21.00 | 31.36 | 32.73 | 31.11 | 32.13 | −0.602 | 31.09 | 32.09 | −0.643 | |

| 22.00 | |||||||||

| 23.00 | |||||||||

|

|

| |||||||

References

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Available online: https://www.un.org/uk/desa/68-world-population-projected-live-urban-areas-2050-says-un (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Yao, L.; Sun, S.; Song, C.; Li, J.; Xu, W.; Xu, Y. Understanding the spatiotemporal pattern of the urban heat island footprint in the context of urbanization, a case study in Beijing, China. Appl. Geogr. 2021, 133, 102496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, S.; Satyanarayana, A.N.V. Urban heat island intensity during winter over metropolitan cities of India using remote-sensing techniques: Impact of urbanization. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2018, 39, 6692–6730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voogt, J.A.; Oke, T.R. Thermal remote sensing of urban climates. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 86, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushore, T.D.; Mutanga, O.; Odindi, J.; Dube, T. Linking major shifts in land surface temperatures to long term land use and land cover changes: A case of Harare, Zimbabwe. Urban Clim. 2017, 20, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuce, P.M.; Cuce, E.; Santamouris, M. Towards Sustainable and Climate-Resilient Cities: Mitigating Urban Heat Islands Through Green Infrastructure. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Lafortezza, R.; Giannico, V.; Sanesi, G.; Zhang, X.; Xu, C. The unrelenting global expansion of the urban heat island over the last century. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 880, 163276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, T.R. The energetic basis of the urban heat island. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1982, 108, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, A.M.; Dennis, L.Y. A review on the generation, determination and mitigation of Urban Heat Island. J. Environ. Sci. 2008, 20, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amengual, A.; Homar, V.; Romero, R.; Brooks, H.E.; Ramis, C.; Gordaliza, M.; Alonso, S. Projections of heat waves with high impact on human health in Europe. Glob. Planet. Change 2014, 119, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppe, C.; Kovats, S.; Jendritzky, G.; Menne, B. Heat-Waves: Risks and Responses; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Marando, F.; Heris, M.P.; Zulian, G.; Udías, A.; Mentaschi, L.; Chrysoulakis, N.; Maes, J. Urban heat island mitigation by green infrastructure in European Functional Urban Areas. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 77, 103564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S). Copernicus Record-Breaking Heat Stress in Southeastern Europe During Summer 2024; Copernicus Climate Change Service; European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts: Reading, UK, 2025; Available online: http://climate.copernicus.eu/copernicus-record-breaking-heat-stress-southeastern-europe-during-summer-2024 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- UNICEF. Rising Heat Across Europe and Central Asia Kills Nearly 400 Children a Year. Press Release, 24 July 2024. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/serbia/en/press-releases/rising-heat-across-europe-and-central-asia-kills-nearly-400-children-a-year (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Republic of Serbia, Ministry of Environmental Protection. Climate Change Adaptation Programme for the Period 2023–2030; Adopted 12 July 2024. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/NAP_Serbia_2024.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Đurđević, V.; Vuković, A.; Vujadinović Mandić, M. Climate Changes Observed in Serbia and Future Climate Projections Based on Different Scenarios of Future Emissions; United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, October 2018; ISBN 978-86-7728-301-8. Available online: https://www.klimatskepromene.rs/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Observed-Climate-Change-and-Projections.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia (RHMSS). Seasonal Bulletin for Serbia, Summer 2024; Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2024. Available online: https://www.hidmet.gov.rs/data/klimatologija/eng/summer.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Vasilevska, L.; Vranic, P.; Marinkovic, A. The effects of changes to the post-socialist urban planning framework on public open spaces in multi-story housing areas: A view from Nis, Serbia. Cities 2014, 36, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanović Protić, I.; Mitković, P.; Vasilevska, L.J. Toward regeneration of public open spaces within large housing estates–A case study of Niš, Serbia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T. The Role of Green Infrastructure in Mitigating the Urban Heat Island Effect. Open J. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3155–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujovic, S.; Haddad, B.; Karaky, H.; Sebaibi, N.; Boutouil, M. Urban heat island: Causes, consequences, and mitigation measures with emphasis on reflective and permeable pavements. CivilEng 2021, 2, 459–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piracha, A.; Chaudhary, M.T. Urban air pollution, urban heat island and human health: A review of the literature. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanilov, K. Taking stock of post-socialist urban development: A recapitulation. In The Post-Socialist City: Urban Form and Space Transformations in Central and Eastern Europe after Socialism; Stanilov, K., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Nedučin, D.; Krklješ, M.; Perović, S.K. Demolition-Based Urban Regeneration from a Post-Socialist Perspective: Case Study of a Neighborhood in Novi Sad, Serbia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Urban Planning Niš. Plan of General Regulation of the City Municipality of Medijana; Official Gazette of the City of Niš, No. 72/12: Niš, Serbia, 2012; Available online: http://www.eservis.ni.rs/urbanistickiprojekti/ (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Republic of Serbia, City of Niš, City Planning and Construction Administration, Monitoring Department. Analysis of the Condition of Surfaces for the Needs of the Functioning of Facilities Within the Block; City of Niš: Niš, Serbia, 2025. Available online: https://publikacije.stat.gov.rs/G2023/pdf/G20234003.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2023).

- Sendi, R.; Kerbler, B. The Evolution of Multifamily Housing: Post-Second World War Large Housing Estates versus Contemporary Trends. Urbani Izziv 2021, 32, 4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tandarić, N.; Ives, C.D.; Watkins, C. From City in the Park to “Greenery in Plant Pots”: The Influence of Socialist and Post-Socialist Planning on Opportunities for Cultural Ecosystem Services. Land Use Policy 2022, 120, 106309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krištofić, B. Tranzicijska preobrazba stanovanja na super-periferiji Evrope. In Tranzicijska Preobrazba Glavnih Gradova, Zagreba i Podgorice, Kao Sustava Naselja; Svirčić Gotovac, A., Rade, Š., Eds.; Institut za Društvena Istraživanja u Zagrebu: Zagreb, Croatia, 2016; pp. 139–166. [Google Scholar]

- Nepravishta, F. Contemporary Architecture in Tirana during the Transition Period. S. East Eur. J. Archit. Des. 2016, 2016, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilevska, L.; Živković, J.; Vasilevska, M.; Lalović, K. Revealing the Relationship between City Size and Spatial Transformation of Large Housing Estates in Post-Socialist Serbia. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2020, 35, 1099–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City Administration for Construction, City of Niš. Information-Analytical Data: Monitoring the Green Space Index through Residential Blocks; Monitoring Unit of the City of Niš: Niš, Serbia, 2025; unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Đekić, J.; Vasilevska, L. Characteristics of multifamily housing development in the post-socialist period: Case study, the city of Niš. Facta Univ.—Ser. Archit. Civ. Eng. 2021, 19, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meili, N.; Acero, J.A.; Peleg, N.; Manoli, G.; Burlando, P.; Fatichi, S. Vegetation Cover and Plant-Trait Effects on Outdoor Thermal Comfort in a Tropical City. Build. Environ. 2021, 195, 107733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Doan, Q.V.; Kusaka, H.; He, C.; Chen, F. Insights into Urban Heat Island and Heat Waves Synergies Revealed by a Land-Surface-Physics-Based Downscaling Method. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2024, 129, e2023JD040531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liao, W.; Rigden, A.J.; Liu, X.; Wang, D.; Malyshev, S.; Shevliakova, E. Urban Heat Island: Aerodynamics or Imperviousness? Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, P.K.; Jim, C.Y.; Nichol, J.E. Urban Morphology and Thermal Stress in High-Density Cities: PET Assessment in Hong Kong. Build. Environ. 2021, 188, 107428. [Google Scholar]

- Höppe, P. The Physiological Equivalent Temperature—A Universal Index for the Biometeorological Assessment of the Thermal Environment. Int. J. Biometeorol. 1999, 43, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kántor, N.; Unger, J. The Most Problematic Variable in the Course of Human-Biometeorological Comfort Assessment—The Mean Radiant Temperature. Open Geosci. 2011, 3, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzarakis, A.; Mayer, H.; Iziomon, M.G. Applications of a Universal Thermal Index: Physiological Equivalent Temperature (PET). Int. J. Biometeorol. 1999, 43, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzarakis, A.; Endler, C. Climate Change and Thermal Bioclimate in Cities: Examples for Urban Areas in Freiburg, Germany. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2010, 54, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Ng, E. Outdoor Thermal Comfort and Outdoor Activities: A Review of Research in the Past Decade. Cities 2012, 29, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavković, M. Urbanistički Modeli Primene Integrisanih Pristupa Upravljanju Kišnim Oticajem u Funkciji Održive Regeneracije i Planiranja Područja Višeporodičnog Stanovanja. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Civil Engineering and Architecture, University of Niš, Niš, Serbia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gunawardena, K.R.; Wells, M.J.; Kershaw, T. Utilizing Green and Blue space to Mitigate Urban Heat Island Intensity. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 584, 1040–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, L.; Gaspari, J.; Fabbri, K. Outdoor Microclimate in Courtyard Buildings: Impact of Building Perimeter Configuration and Tree Density. Buildings 2023, 13, 2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unal, M.; Middel, A. Improving Thermal Comfort in Hot-Arid Phoenix, Arizona Courtyards: Exploring the Cooling Benefits of Ground Surface Cover and Shade. Build. Environ. 2025, 278, 113001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, J.; Dai, M. Improving Comfort and Health: Green Retrofit Designs for Sunken Courtyards during the Summer Period in a Subtropical Climate. Buildings 2021, 11, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Yang, J.; Huang, J.; Zhong, R. Examining the Effects of Tree Canopy Coverage on Human Thermal Comfort and Heat Dynamics in Courtyards: A Case Study in Hot-Humid Regions. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirt, S. Whatever happened to the (post)socialist city? Cities 2013, 32, S29–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sýkora, L.; Bouzarovski, S. Multiple transformations: Conceptualising the post-communist urban transition. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D.; Dushkova, D.; Haase, A.; Kronenberg, J. Green infrastructure in post-socialist cities: Evidence and experiences from Eastern Germany, Poland and Russia. In Post-Socialist Urban Infrastructures; Schindler, S., Díaz, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 140–160. [Google Scholar]

- Sharmin, T.; Steemers, K.; Humphreys, M. Outdoor Thermal Comfort and Summer PET Range: A Field Study in Tropical City Dhaka. Energy Build. 2019, 198, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.; Yan, J.; Cui, Y.; Song, D.; Yin, X.; Sun, N. Studies on the Specificity of Outdoor Thermal Comfort during the Warm Season in High-Density Urban Areas. Buildings 2023, 13, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Li, Z.; Meng, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Wu, X.; Liu, Q.; Wang, C. Simulation and Optimization of Thermal Comfort in Residential Areas Based on Outdoor Morphological Parameters. Build. Environ. 2023, 245, 110837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briegel, F.; Wehrle, J.; Schindler, D.; Christen, A. High-Resolution Multi-Scaling of Outdoor Human Thermal Comfort and Its Intra-Urban Variability Based on Machine Learning. Geosci. Model Dev. 2024, 17, 1667–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, K.F.A.; Justi, A.C.A.; Novais, J.W.Z.; de Moura Santos, F.M.; Nogueira, M.C.D.J.A.; Miranda, S.A.; Marques, J.B. Calibration of the Physiological Equivalent Temperature (PET) Index Range for Outside Spaces in a Tropical Climate City. Urban Clim. 2022, 44, 101196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimimoshaver, M.; Shahrak, M.S. The Effect of Height and Orientation of Buildings on Thermal Comfort. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 79, 103720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ENVI-Met. Official ENVI-Met Website. Available online: https://envi-met.info/doku.php?id=root:start (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Yang, X.; Zhao, L.; Bruse, M.; Meng, Q. Evaluation of a Microclimate Model for Predicting the Thermal Behavior of Different Ground Surfaces. Build. Environ. 2013, 60, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forouzandeh, A. Numerical Modeling Validation for the Microclimate Thermal Condition of Semi-Closed Courtyard Spaces between Buildings. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 36, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleghani, M.; Tenpierik, M.; van den Dobbelsteen, A.; Sailor, D. Thermal Comfort in Outdoor Urban Spaces: A Comparison of Different Strategies. Build. Environ. 2014, 77, 199–216. [Google Scholar]

- Salata, F.; Golasi, I.; de Lieto Vollaro, A.; de Lieto Vollaro, R. Urban Microclimate and Outdoor Thermal Comfort: A Proper Methodology for Heat Mitigation through Urban Planning. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 26, 27–47. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzidimitriou, A.; Yannas, S. Microclimate Design for Open Spaces: Ranking Urban Design Effects on Pedestrian Thermal Comfort in Summer. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 26, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, R.M.A.; Abdallah, A.S.H. Assessment of Outdoor Shading Strategies to Improve Outdoor Thermal Comfort in School Courtyards in Hot and Arid Climates. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 86, 104147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamei, E.; Chau, H.W.; Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Stojcevski, A. Review on the Cooling Potential of Green Roofs in Different Climates. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 791, 148407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, E.E.; Ortner, F.P.; Peng, S.; Yenardi, A.; Chen, Z.; Tay, J.Z. Climate-Responsive Urban Planning through Generative Models: Sensitivity Analysis of Urban Planning and Design Parameters for Urban Heat Island in Singapore’s Residential Settlements. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 114, 105779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Lau, K.K.L.; Ng, E. Urban Tree Design Approaches for Mitigating Daytime Urban Heat Island Effects in a High-Density Urban Environment. Energy Build. 2016, 114, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Yoon, H. Evaluating Planting Strategies for Outdoor Thermal Comfort in High-Rise Residential Complexes: A Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulation Study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 88641–88663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zölch, T.; Maderspacher, J.; Wamsler, C.; Pauleit, S. Using Green Infrastructure for Urban Climate-Proofing: An Evaluation of Heat Mitigation Measures at the Micro-Scale. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 20, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimoudi, A.; Nikolopoulou, M. Vegetation in the Urban Environment: Microclimatic Analysis and Benefits. Energy Build. 2003, 35, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashua-Bar, L.; Potchter, O.; Bitan, A.; Boltansky, D.; Yaakov, Y. Microclimate Modelling of Street Tree Species Effects within the Varied Urban Morphology in the Mediterranean City of Tel Aviv, Israel. Int. J. Climatol. 2010, 30, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, N.H.; Tan, C.L.; Kolokotsa, D.D.; Takebayashi, H. Greenery as a Mitigation and Adaptation Strategy to Urban Heat. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancewicz, A.; Kurianowicz, A. Urban Greening in the Process of Climate Change Adaptation of Large Cities. Energies 2024, 17, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghamolaei, R.; Azizi, M.M.; Aminzadeh, B.; O’Donnell, J. A Comprehensive Review of Outdoor Thermal Comfort in Urban Areas: Effective Parameters and Approaches. Energy Environ. 2023, 34, 2204–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzik, G.; Sylla, M.; Kowalczyk, T. Understanding Urban Cooling of Blue–Green Infrastructure: A Review of Spatial Data and Sustainable Planning Optimization Methods for Mitigating Urban Heat Islands. Sustainability 2025, 17, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, L.; Sommese, F.; Ausiello, G.; Polverino, F. New Green Spaces for Urban Areas: A Resilient Opportunity for Urban Health. In Resilience vs Pandemics: Innovations in Public Places and Buildings; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, D.; Lian, Z.; Liu, W.; Guo, C.; Liu, W.; Liu, K.; Chen, Q. A Comprehensive Review of Thermal Comfort Studies in Urban Open Spaces. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 742, 140092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Wu, Z.; Gao, W.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, D.; Li, J. Summer Outdoor Thermal Comfort Evaluation of Urban Open Spaces in Arid-Hot Climates. Energy Build. 2024, 321, 114679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, C.; Ürge-Vorsatz, D.; Carmeliet, J.; Bardhan, R. Cooefficacy of Trees across Cities Is Determined by Background Climate, Urban Morphology, and Tree Trait. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahem, S.A.; Taha, H.S.; Hassan, S.A. Effect of Water Features on the Microclimate of Residential Projects in a Hot-Arid Climate: A Comparative Analysis. Acta Sci. Pol. Adm. Locorum 2022, 21, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rising, H.H.; Deng, L. The Effects of Small Water Cooling Islands on Body Temperature. J. Urban Des. 2024, 29, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, J.S.; Carlson, J.; Kaloush, K.E.; Phelan, P. A Comparative Study of the Thermal and Radiative Impacts of Photovoltaic Canopies on Pavement Surface Temperatures. Sol. Energy 2007, 81, 872–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.P.; Matzarakis, A.; Hwang, R.L. Shading Effect on Long-Term Outdoor Thermal Comfort. Build. Environ. 2010, 45, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, R.L.; Lin, T.P.; Matzarakis, A. Seasonal Effects of Urban Street Shading on Long-Term Outdoor Thermal Comfort. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczerek, E. The Problem of Densification of Large-Panel Housing Estates upon the Example of Cracow. Land 2021, 10, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandić, L.; Đjukić, A.; Marić, J.; Mitrović, B. A Systematic Review of Outdoor Thermal Comfort Studies for the Urban (Re) Design of City Squares. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przesmycka, N.; Kwiatkowski, B.; Kozak, M. The Thermal Comfort Problem in Public Space during the Climate Change Era. Energies 2022, 15, 6504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia. Monthly Bulletin for Serbia: August 2024; Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2024. Available online: https://www.hidmet.gov.rs/data/klimatologija/ciril/Avgust.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Wikipedia. Niš. Available online: https://sh.wikipedia.org/wiki/Niš (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Google Maps. Niš. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Nis (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- GIS Niš. GIS Portal of the City Administration of Niš—gunisPublic. Available online: https://gis.ni.rs/smartPortal/gunisPublic (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Weather Atlas. Climate: Niš, Serbia. Available online: https://www.weather-atlas.com/en/serbia/nis-climate (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- ISO 7726; Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment—Instruments for Measuring Physical Quantities. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998.

- Koletsis, I.; Tseliou, A.; Lykoudis, S.; Tsiros, I.X.; Lagouvardos, K.; Psiloglou, B.; Founda, D.; Pantavou, K. Validation of ENVI-met Microscale Model with In-Situ Measurements in Warm Thermal Conditions across Athens Area. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Environmental Science and Technology, CEST2021, Athens, Greece, 1–4 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, X.; Cao, X.; Liu, Z. Numerical simulation of the thermal environment during summer in coastal open space and research on evaluating the cooling effect: A case study of May Fourth Square, Qingdao. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, A.; Kolokotroni, M. Microclimate Data for Building Energy Modelg: Study on ENVI-met Forcing Data. In Proceedings of the Building Simulation 2019, Rome, Italy, 2–4 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Middel, A.; Fang, X.; Wu, R. ENVI-met Model Performance Evaluation for Courtyard Simulations in Hot-Humid Climates. Urban Clim. 2024, 55, 101909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bande, L.; Afshari, A.; Al Masri, D.; Jha, M.; Norford, L.; Tsoupos, A.; Marpu, P.; Pasha, Y.; Armstrong, P. Validation of UWG and ENVI-met Models in an Abu Dhabi District, Based on Site Measurements. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsson, S.; Lindberg, F.; Eliasson, I.; Holmer, B. Different Methods for Estimating the Mean Radiant Temperature in an Outdoor Urban Setting. Int. J. Climatol. 2007, 27, 1983–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaverková, M.D.; Kosakiewicz, M.; Krysińska, K.; Strzeszewska, K. Sustainable Construction in Post-Industrial Ursus District in Warsaw: Biologically Active Areas on Roofs and Underground Garages. Inżyn. Bezpieczeństwa Obiektów Antropog. 2024, 3, 10–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ODU Green Roof. Liziera Residential Complex—Intensive Green Roof. 2022. Available online: https://odu-green-roof.com (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- ZinCo. Grønttorvet, Copenhagen—Park Above an Underground Car Park. 2023. Available online: https://zinco-greenroof.com (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Alsaad, H.; Hartmann, M.; Hilbel, R.; Voelker, C. ENVI-met Validation Data Accompanied with Simulation Data of the Impact of Facade Greening on the Urban Microclimate. Data Brief 2022, 42, 108200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.; Holzer, M.; Kretschmer, F. Implementing Blue-Green Infrastructures in Cities—A Methodological Approach Considering Space Constraints and Microclimatic Benefits. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 126, 106391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán-Marín, C.; Rivera-Gómez, C.; López-Cabeza, V.P.; Roa-Fernández, J. Courtyard Microclimate ENVI-met Outputs Deviation from the Experimental Data. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2220. [Google Scholar]

- López-Cabeza, V.P.; Diz-Mellado, E.; Rivera-Gómez, C.; Galán-Marín, C.; Samuelson, H.W. Thermal Comfort Modelling and Empirical Validation of Predicted Air Temperature in Hot-Summer Mediterranean Courtyards. J. Build. Perform. Simul. 2022, 15, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, W.; Sinsel, T.; Simon, H.; Morakinyo, T.E.; Liu, H.; Ng, E. Evaluating the Thermal-Radiative Performance of ENVI-met Model for Green Infrastructure Typologies: Experience from a Subtropical Climate. Build. Environ. 2022, 207, 108427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eingrüber, N.; Korres, W.; Löhnert, U.; Schneider, K. Investigation of the ENVI-met Model Sensitivity to Different Wind Direction Forcing Data in a Heterogeneous Urban Environment. Adv. Sci. Res. 2023, 20, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrowicz, O.; Saroglou, S.T.; Pearlmutter, D. Evaluation of Summer Mean Radiant Temperature Simulation in ENVI-met in a Hot Mediterranean Climate. Build. Environ. 2023, 245, 110881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, C. A study on the cooling effects of greening in a high-density city: An experience from Hong Kong. Build. Environ. 2012, 47, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middel, A.; Häb, K.; Brazel, A.J.; Martin, C.A.; Guhathakurta, S. Impact of urban form and design on mid-afternoon microclimate in Phoenix Local Climate Zones. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 122, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccolo, S.; Kämpf, J.; Scartezzini, J.-L.; Pearlmutter, D. Outdoor Human Comfort and Thermal Stress: A Comprehensive Review on Urban Microclimate Modeling. Urban Clim. 2018, 24, 165–181. [Google Scholar]

- Balany, F.; Livesley, S.J.; Fletcher, T.D. Studying the Effect of Blue-Green Infrastructure on Microclimate and Human Thermal Comfort in Melbourne’s Central Business District. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Yang, G.; Zhan, W.; Jin, S. A Critical Review on the Cooling Effect of Urban Blue-Green Infrastructures: Size, Configuration and Synergy. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 117, 106543. [Google Scholar]

- Probst, N.; Bach, P.M.; Cook, L.M.; Maurer, M.; Leitão, J.P. Blue-Green Systems for Urban Heat Mitigation: Mechanisms, Effectiveness and Research Directions. Blue-Green Syst. 2022, 4, 348–372. [Google Scholar]

| PET (°C) | Thermal Perception | Grade of Physiological Stress Level |

|---|---|---|

| <4 | Very cold | Extreme cold stress |

| 4–8 | Cold | Strong cold stress |

| 8–13 | Cool | Moderate cold stress |

| 13–18 | Slightly cool | Slight cold stress |

| 18–23 | Comfortable | No thermal stress |

| 23–29 | Slightly warm | Slight heat stress |

| 29–35 | Warm | Moderate heat stress |

| 35–41 | Hot | Strong heat stress |

| >41 | Very hot | Extreme heat stress |

| Variable | Resolution | Range | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outside Temperature | 0.1 °C | −40° to +65 °C | ±0.3 °C |

| Outside Relative Humidity | 1% | 1 to 100% RH | ±2% |

| Wind Speed | 0.1 m/s | 0 to 89 m/s | ±0.9 m/s or ±5% (whichever is greater) |

| Wind Direction | 1° | 1–360° | ±3° |

| Solar Radiation | 1 W/m2 | 0 to 1800 W/m2 | ±5% of full scale |

| Weather | Maximum Air Temperature (◦C) | Minimum Air Temperature (◦C) | Wind Speed (m/s) | Wind Direction | Relative Humidity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunny | 40.5 | 25.2 | 1.03 | South–West | 40 |

| OP | Shade Regime |

|---|---|

| P1 | Full sun 06:30–13:00 h; shaded by 27 m south façade thereafter |

| P2 | Sun-exposed until 16:00 h; partial shade afterwards |

| P3 | Sun-exposed until 16:00 h |

| P4 | Sun 08:00–13:30 h; shaded by 27 m and 6 m blocks |

| Vegetation Type | ENVI-Met Name | Shape | Height (m) | Crown Diameter (m) | Leaf Area Index (LAI) | Canopy Density | Evapotranspiration Coefficient (Ke) | Shortwave Albedo | Emissivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deciduous tree A | Cylindric, medium trunk, sparse, medium | Cylindric | 15 | 6 | 3.5 | Sparse | 0.80 | 0.18 | 0.95 |

| Deciduous tree B | Spherical, medium trunk, sparse, small | Spherical | 5 | 3 | 2.8 | Sparse | 0.75 | 0.20 | 0.95 |

| Grass cover | Grass, average density | Ground layer | 0.25 | – | 2.0 | Average density | – | 0.25 | 0.95 |

| Parameter | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation period | 14 August 2024, 00:00–24:00 | Niš Meteorological Station (WMO 13270) |

| Daily maximum air temp. | 38.2 °C (forcing) | Niš Meteorological Station (hourly series) |

| Synoptic maximum (reference) | 40.5 °C | Niš Meteorological Station (daily synoptic) |

| Relative humidity (mean) | 40% | Field survey calibration + station data |

| Wind speed/direction | 1.03 m·s−1/220° | Niš Meteorological Station |

| Spin-up period | 48 h | ENVI-met best practice |

| Grid dimensions | 215 × 210 × 40 | Model setup |

| Grid cell size | 2 m × 2 m × 2 m | Model setup |

| Calculation height for PET | 1.4 m | BioMet 5.7.1 |

| Human parameters | M = 80 W·m−2, clo = 0.6 | ISO 7726 standard |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bogdanović Protić, I.; Vasilevska, L.; Petrović, N. Blue–Green Infrastructure Strategies for Improvement of Outdoor Thermal Comfort in Post-Socialist High-Rise Residential Areas: A Case Study of Niš, Serbia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10876. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310876

Bogdanović Protić I, Vasilevska L, Petrović N. Blue–Green Infrastructure Strategies for Improvement of Outdoor Thermal Comfort in Post-Socialist High-Rise Residential Areas: A Case Study of Niš, Serbia. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10876. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310876

Chicago/Turabian StyleBogdanović Protić, Ivana, Ljiljana Vasilevska, and Nemanja Petrović. 2025. "Blue–Green Infrastructure Strategies for Improvement of Outdoor Thermal Comfort in Post-Socialist High-Rise Residential Areas: A Case Study of Niš, Serbia" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10876. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310876

APA StyleBogdanović Protić, I., Vasilevska, L., & Petrović, N. (2025). Blue–Green Infrastructure Strategies for Improvement of Outdoor Thermal Comfort in Post-Socialist High-Rise Residential Areas: A Case Study of Niš, Serbia. Sustainability, 17(23), 10876. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310876