Considering the Sustainable Benefit Distribution in Agricultural Supply Chains from Sales Efforts: An Improved ‘Tripartite Synergy’ Model Based on Shapley–TOPSIS

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Literature Review

2. Methodology

2.1. Shapley

2.2. Shapley Value Method Improvement

TOPSIS-Based Computation of the Closeness Coefficient

- (1)

- Normalization. Each column is first normalized to eliminate the effects of different units:

- (2)

- Weighted normalized decision matrix. Using the weight vector , we obtain

- (3)

- Positive and negative ideal solutions. For benefit-type indicators, the positive ideal solution and negative ideal solution are defined as

- (4)

- Distances to ideal solutions. The Euclidean distances from member iii to the positive and negative ideal solutions are

- (5)

- Closeness coefficient. The TOPSIS closeness coefficient of member iii is finally given by

2.3. Supply Chain Profit Allocation Model Under the ‘Farmer–Cooperative–Retailer’ Agribusiness Linkage Method Based on an Improved Shapley Value Method

2.3.1. Theoretical Definition of the Tripartite Synergy Model

- (1)

- The expected profits for all parties under centralized decision-making are no lower than those under decentralized decision-making;

- (2)

- No single entity derives higher long-term expected returns by unilaterally deviating from the alliance (alliance stability);

- (3)

- The equilibrium level of sales effort is endogenously determined by overall profit maximization, with marginal returns matching marginal distribution weights (incentive compatibility);

2.3.2. Model Setup

- (1)

- This research focuses on a supply chain structured as ‘farmers–cooperative–retailers.’ All three parties are rational business entities, and the objective is to maximize collective (system-wide) profit.

- (2)

- The analysis considers only the distribution of supply chain benefits within a single cooperation period.

- (3)

- Within a cooperation period, retailers determine the order quantity q on the basis of market conditions. Farmers sell their output to the cooperative at price ; after processing, the cooperative sells to retailers at price ; and retailers then sell to consumers at retail price

- (4)

- The model incorporates retailers’ sales effort with level , , where x is the incremental input coefficient for sales effort. Following Ref. [34], the relationship between sales effort input and cost is specified as , where denotes the sensitivity of retailers’ sales cost to sales effort.

- (5)

- The market demand for the agricultural product is represented in additive form [35] as , Q = q, where is the initial market demand and where and denote the sensitivities of market demand to price and to product production quality, respectively.

- (6)

- The cost parameters are defined as follows: farmer unit input cost, ; cooperative unit processing cost, ; unit transportation cost, ; and retailer unit selling input cost,

2.3.3. Stakeholder Payoff Distribution Under Decentralized Decision-Making

2.3.4. Benefits Accrued to Multiple Parties Under Centralized Decision-Making

2.3.5. Allocation of Stakeholder Payoffs Based on the Shapley Value Method

2.3.6. Benefit Allocation via an Improved Shapley Value Method

3. Results

- (1)

- Under decentralized decision-making, the payoffs of the respective stakeholders are as follows:Optimal Revenue of Farmers:CNY, CNY/kgOptimal Revenue of Cooperatives:CNY, CNY/kgOptimal Revenues of Retailers:CNY, CNY/kgkg

- (2)

- The system-wide optimal profit of the supply chain under centralized decision-making is as follows:CNYkg, CNY/kg

- (3)

- Benefit allocation among the players under the traditional Shapley value method:Revenue of Farmers:CNYRevenue of Cooperatives:CNYRevenue of Retailers:CNY

- (4)

- Distribution of benefits among parties under the improved Shapley value method:

- (5)

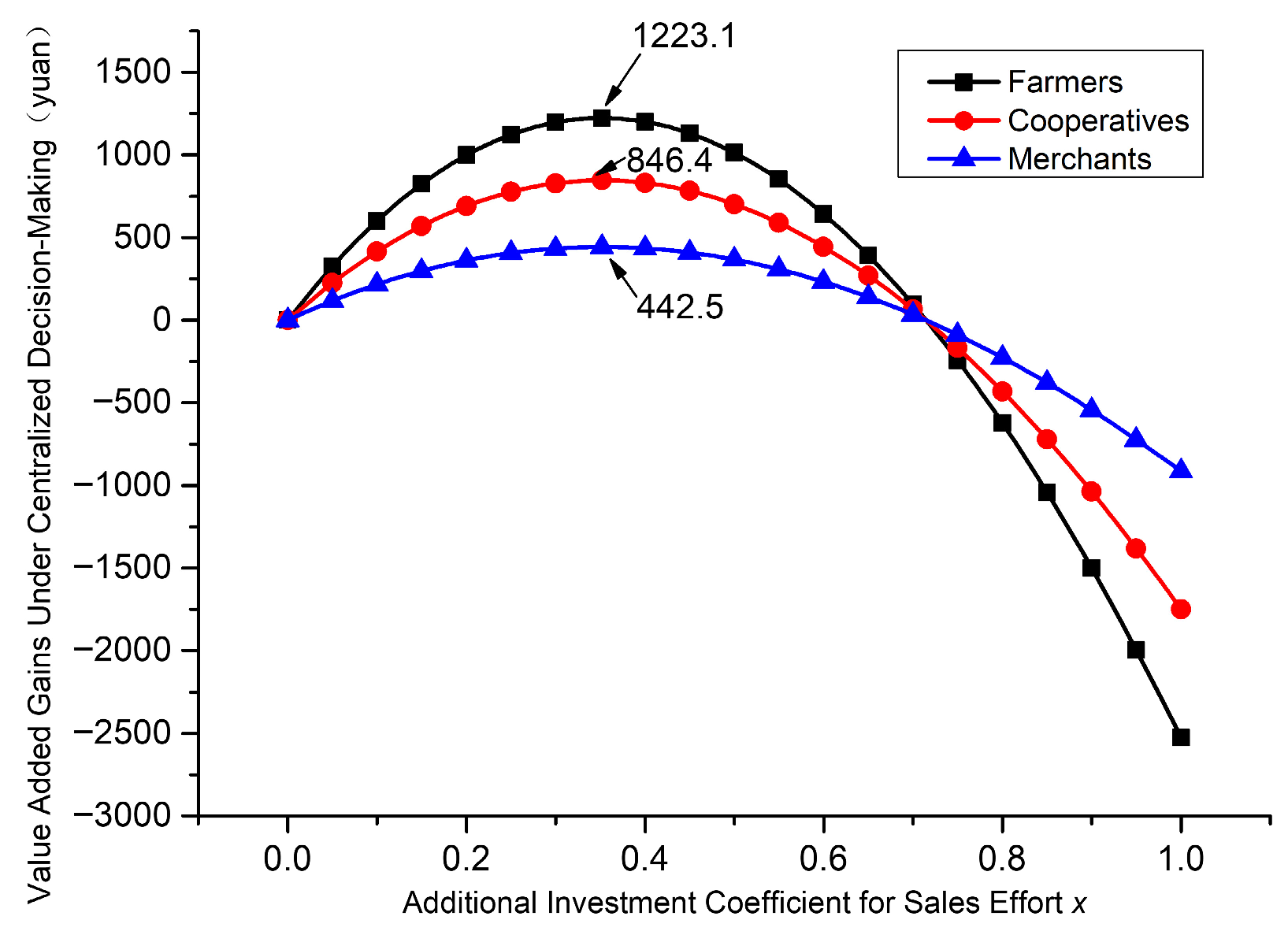

- Effect of the additional investment coefficient of sales effort on the payoffs of all parties:

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Main Conclusions

5.2. Contributions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhan, S.; Wan, Z.L. A study on benefit distribution of agricultural product quality governance under the perspective of digital supply chain. Agric. Econ. 2025, 71, 357–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, P.F.; Hou, W.H.; Wang, L.; Zhou, C. Research on the Operational Decision-Making Strategy of Contract Farming Supply Chain Under the Empowerment of Blockchain Technology and Government Subsidies. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2025, 16, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Luo, R.; Dai, Y.H.; Li, J.J.; Xu, H. Research on dynamic pricing and coordination model of fresh produce supply chain based on differential game considering traceability goodwill. RAIRO-Oper. Res. 2024, 58, 3525–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Cao, X.N.; Li, W.L. Research on Pricing and Coordination of Fresh Agricultural Product Supply Chain Considering the Smart Agriculture Technology under Different Power Structures. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2025, 33, 262–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S.; Kjorlien, S.; Ligon, E.; Shafran, A. Spatial Procurement of Farm Products and the Supply of Processed Foods: Application to the Tomato Processing Industry. Rev. Ind. Organ. 2024, 64, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaeli, S.; Kalvandi, R.; Sahebi, H. A multi-level multi-product supply chain network design of vegetables products considering costs of quality: A case study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, 0303054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.M.; Chen, H.R.; Liu, Z.; Qi, G.H. Strategies of pricing and channel mode in a supply chain considering Showrooms effect. Control Decis. 2021, 36, 2891–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L.; Li, G. Fresh Agricultural Products Supply Chain Coor Dination Research—Based on Risk Analysis of the Revenue Sharing Contract. J. Tech. Econ. Manag. 2014, 2, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Angelidis, G.; Varsakelis, N.C. Economic Shock Transmission through Global Value Chains: An Assessment using Network Analysis. Int. Adv. Econ. Res. 2023, 29, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, E.; Dadakas, D.; Angelidis, G. Shock Propagation and the Geometry of International Trade: The US–China Trade Bipolarity in the Light of Network Science. Mathematics 2025, 13, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Zhou, Z.C.; Yu, X.H.; Chen, J.T.; Li, P.N.; Wang, Z.Q. Research on Profit Allocation of Agricultural Products Co-Delivery Based on Modified Interval Shapley Value. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.J.; Xiang, G.C.; Ya, S.T. The effectiveness of the multilateral coalition to develop a green agricultural products market in china based on a TU cooperative game analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Qiang, C. Evolutionary game theoretic analysis on low-carbon strategy for supply chain enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 230, 981–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Wang, F.L.; Wang, J.Q.; Qian, C. Research on Food Safety Control Based on Evolutionary Game Method from the Perspective of the Food Supply Chain. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.B.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Wu, J.; Gonzalez, E.D.R.S. An evolutionary game model of manufacturers and consumers’ behavior strategies for green technology and government subsidy in supply chain platform. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 189, 109918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Fan, T.J.; Zhang, L. Revenue-Sharing Contract of Fresh Product in “Farming-Supermarket Docking” Mode. J. Syst. Manag. 2019, 28, 742–751. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.X.; Huang, L.; Ma, L.J. Research on agricultural product supply chain coordination contract with cost-sharing TPL service providers. J. Ind. Eng. Eng. Manag. 2021, 35, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.L.; Huang, Y.J.; E, C.G. Research on cooperative games of queuing networks for agricultural cooperative alliances under the mode of connecting agriculture with supermarkets. J. Syst. Sci. Math. Sci. 2016, 36, 1972–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.F. The Interests Distribution among the Agricultural Products Supply Chain Nodes Based on the Shapley Value Model —The Empirical Study of Laying Hens Industry in Jiangxi Province. Hubei Agric. Sci. 2016, 55, 1039–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.K.; Yadav, S. Price and profit structuring for single manufacturer multi-buyer integrated inventory supply chain under price-sensitive demand condition. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 139, 106208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Hu, Y.; He, L.; Avrutin, V. Research on Coordination of Fresh Agricultural Product Supply Chain Considering Fresh-Keeping Effort Level under Retailer Risk Avoidance. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2021, 2021, 5527215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xiong, M.; Yang, F.; Shi, W. Decision-making and Coordination of a Three-tier Fresh Agricultural Product Supply Chain Considering Dynamic Freshness-keeping Effort. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2024, 33, 2052–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Huang, N.; Hu, B.; Sun, W.; Shi, L.; Zhao, Y.; Han, C. Cross-border Supply Chain Coordination of Low-Carbon Agricultural Products under the Risk of Supply Uncertainty. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0309763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahato, S.; Mahato, F.; Mahata, G.C. Game Theoretical Analysis in Sustainable Supply Chain for Perishable Products Incorporating Transportation Strategies and Partial Backlogging under Carbon Emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 519, 145890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, V.D.; Levinsky, R.; Zeleny, M. The Shapley value, the Proper Shapley value, and sharing rules for cooperative ventures. Oper. Res. Lett. 2020, 48, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.Y.; Chi, L.; Li, J.X.; Xing, L.W.; Yang, L.; Wu, J.Z.; Meng, H. A Study on Revenue Distribution of Chinese Agricultural E-Commerce Supply Chain Based on the Modified Shapley Value Method. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, L.; Zhang, J.J.; Du, F.L. Study on the profit distribution of the mutton sheep industry chain based on the modified Shapley value method. Pratacultural Sci. 2023, 40, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Gao, B.H. Dual-Channel Supply Chain of Agricultural Products under Centralised and Decentralised Decision-Making. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Z.; Lu, L.; Liu, Z.L.; Sun, Y.X. Study on measurement and prediction of agricultural product supply chain resilience based on improved EW-TOPSIS and GM (1,1)-Markov models under public emergencies. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0321248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.Y.; Tang, X.M.; Zhao, C.; Liu, L.H.; Shi, H.B. Collaborative Preservation Strategy of Agricultural Product Suppliers and Retailers: An Evolutionary Game and Simulation Analysis. Econ. Comput. Econ. Cybern. Stud. Res. 2025, 59, 174–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Tian, X.Y.; Guo, M.C. Pricing decision and channel selection of fresh agricultural products dual-channel supply chain based on blockchain. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, L. Pricing Policies and Contracts Design in a “Farmer-Supermarket Direct Purchase” Supply Chain with Asymmetric Information. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2018, 26, 153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Q.; Fan, T.J. Design of incentive contract for fresh agricultural products supply chain considering risk preference. J. Ind. Eng. Eng. Manag. 2018, 32, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, P.; You, H.Y.; Fan, Y.C. Optimal quality effort strategy in service supply chain of live streaming e-commerce based on platform marketing effort. Control Decis. 2022, 37, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.Y.; Shi, B.L. Fresh Agricultural Product Supply Chain Coordination Considering the Level of Effort, Loss and Consumer Utility. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2019, 24, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.C.; Hou, G.S.; Rao, W.Z. Collaborative logistics for agricultural products of ’farmer plus consumer integration purchase’ under platform empowerment. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255 Pt A, 124521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.C.; Li, D.F. Improved Shapley Values Based on Players’ Least Square Contributions and Their Applications in the Collaborative Profit Sharing of the Rural E-commerce. Group Decis. Negot. 2022, 31, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Wei, L.B.; Wu, J.Q. The Creation and Allocation of Premium Price among Farmer-Supermarket Direct-Purchase—Analysis on Innovation of the mode of “Farmer+Cooperative+Supermarket”. Financ. Trade Econ. 2012, 33, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, S.J. Profit Allocation in Supply Chain Cooperative Games with Fuzzy Demand. J. Univ. Electron. Sci. Technol. China (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2014, 16, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.Z.; Liu, R.H. Three-stage Supply Chain Coordination of Connecting Agriculture with Supermarkets Considering Loss and Effort Level. Chin. J. Syst. Sci. 2018, 26, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.F.; Zhao, Q.H.; Xi, M.H. A retailer-supplier supply chain model with trade credit default risk in a supplier-Stackelberg game. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2017, 112, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Collaborative Entity | Risk Bearing | Effort Level | Financial Investment | Information Acquisition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmers | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Cooperatives | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| Retailers | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Coefficient x | Decentralized Decision-Making | Centralized Decision-Making with Improved Shapley Value Method | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmers | Cooperatives | Retailers | Farmers | Cooperatives | Retailers | |

| 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 0.05 | 167 | 83.5 | 41.8 | 325.0 | 224.8 | 117.6 |

| 0.10 | 308 | 154 | 77 | 599.9 | 415.1 | 217.0 |

| 0.15 | 423 | 211.6 | 105.8 | 824.7 | 570.7 | 298.4 |

| 0.20 | 513 | 256.3 | 128.1 | 998.3 | 690.8 | 361.2 |

| 0.25 | 576 | 288.2 | 144.1 | 1122.9 | 777.1 | 406.3 |

| 0.30 | 615 | 307.4 | 153.7 | 1197.5 | 828.7 | 433.3 |

| 0.3517 | 628 | 314.1 | 157 | 1223.1 | 846.4 | 442.5 |

| 0.40 | 617 | 308.3 | 154.2 | 1200.8 | 831.0 | 434.5 |

| 0.45 | 581 | 290.3 | 145.2 | 1130.8 | 782.4 | 409.1 |

| 0.50 | 521 | 260.3 | 130.2 | 1013.9 | 701.6 | 366.8 |

| 0.55 | 437 | 218.4 | 109.2 | 851.4 | 589.1 | 308.1 |

| 0.60 | 330 | 165 | 82.5 | 642.2 | 444.3 | 232.3 |

| 0.65 | 200 | 100.1 | 50.1 | 389.6 | 269.5 | 140.9 |

| 0.70 | 48 | 24.2 | 12.1 | 94.6 | 65.4 | 34.3 |

| 0.75 | −125 | −62.6 | −31.3 | −243.7 | −168.7 | −88.1 |

| 0.80 | −320 | −160 | −80 | −623.2 | −431.3 | −225.5 |

| 0.85 | −535 | −267.6 | −133.8 | −1042.7 | −721.7 | −377.3 |

| 0.90 | −770 | −385.1 | −192.6 | −1500.2 | −1038.2 | −542.7 |

| 0.95 | −1025 | −512.3 | −256.1 | −1995.4 | −1381.0 | −721.9 |

| 1.00 | −1297 | −648.6 | −324.3 | −2526.3 | −1748.3 | −913.9 |

| Collaborative Entity | Decentralized Decision-Making | Centralized Decision-Making | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Traditional Shapley Value Method | Improved Shapley Value Method | Modified Value | Total | ||

| Farmers | 16,828 | 29,449.1 | 29,449 | 32,774 | 3325 | 67,312 |

| Cooperatives | 8414.1 | 23,139 | 22,681 | −458 | ||

| Retailers | 4207 | 14,725 | 11,857 | −2868 | ||

| Coefficient x | Centralized Decision-Making | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improved Shapley Value Method | Value Redistribution (Performance-Based Distribution) | |||||

| Farmers | Cooperatives | Retailers | Farmers | Cooperatives | Retailers | |

| 0.00 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 0.05 | 325.0 | 224.8 | 117.6 | 162.1 | 112.2 | 393.7 |

| 0.10 | 599.9 | 415.1 | 217.0 | 298.9 | 206.8 | 726.3 |

| 0.15 | 824.7 | 570.7 | 298.4 | 409.3 | 283.2 | 1000.5 |

| 0.20 | 998.3 | 690.8 | 361.2 | 495.2 | 342.7 | 1212.1 |

| 0.25 | 1122.9 | 777.1 | 406.3 | 556.5 | 385.1 | 1363.3 |

| 0.30 | 1197.5 | 828.7 | 433.3 | 593.3 | 410.6 | 1455.1 |

| 0.3517 | 1223.1 | 846.4 | 442.5 | 605.6 | 419.1 | 1487.3 |

| 0.40 | 1200.8 | 831.0 | 434.5 | 595.1 | 411.8 | 1459.1 |

| 0.45 | 1130.8 | 782.4 | 409.1 | 560.0 | 387.6 | 1375.4 |

| 0.50 | 1013.9 | 701.6 | 366.8 | 503.1 | 348.1 | 1230.8 |

| 0.55 | 851.4 | 589.1 | 308.1 | 422.4 | 292.3 | 1033.2 |

| 0.60 | 642.2 | 444.3 | 232.3 | 319.9 | 221.4 | 778.7 |

| 0.65 | 389.6 | 269.5 | 140.9 | 194.6 | 134.6 | 471.8 |

| 0.70 | 94.6 | 65.4 | 34.3 | 47.3 | 32.8 | 112.9 |

| 0.75 | −243.7 | −168.7 | −88.1 | −121.8 | −84.3 | −294.9 |

| 0.80 | −623.2 | −431.3 | −225.5 | −312.9 | −216.5 | −750.6 |

| 0.85 | −1042.7 | −721.7 | −377.3 | −525.9 | −363.9 | −1251.2 |

| 0.90 | −1500.2 | −1038.2 | −542.7 | −759.0 | −525.2 | −1796.8 |

| 0.95 | −1995.4 | −1381.0 | −721.9 | −1014.0 | −701.7 | −2382.2 |

| 1.00 | −2526.3 | −1748.3 | −913.9 | −1290.1 | −892.8 | −3006.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, E.; Guo, Y.; Huang, J.; Zheng, B.; Lin, W. Considering the Sustainable Benefit Distribution in Agricultural Supply Chains from Sales Efforts: An Improved ‘Tripartite Synergy’ Model Based on Shapley–TOPSIS. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10868. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310868

Chen E, Guo Y, Huang J, Zheng B, Lin W. Considering the Sustainable Benefit Distribution in Agricultural Supply Chains from Sales Efforts: An Improved ‘Tripartite Synergy’ Model Based on Shapley–TOPSIS. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10868. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310868

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Enhao, Yumin Guo, Jiuzhen Huang, Bingqing Zheng, and Wenhe Lin. 2025. "Considering the Sustainable Benefit Distribution in Agricultural Supply Chains from Sales Efforts: An Improved ‘Tripartite Synergy’ Model Based on Shapley–TOPSIS" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10868. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310868

APA StyleChen, E., Guo, Y., Huang, J., Zheng, B., & Lin, W. (2025). Considering the Sustainable Benefit Distribution in Agricultural Supply Chains from Sales Efforts: An Improved ‘Tripartite Synergy’ Model Based on Shapley–TOPSIS. Sustainability, 17(23), 10868. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310868