Outdoor Learning in Belgium and Türkiye: Cultural Heritage Sensitivity and Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Cultural Heritage

1.2. Cultural Heritage Sensitivity Within the Axis of Sustainability

1.3. Problem Statement

- What is the immediate and end-of-term impact of Outdoor Learning activities on educational sustainability in Türkiye and Belgium?

- What is the impact of Outdoor Learning activities on sensitivity to cultural heritage in Türkiye and Belgium?

- What are the views of school administrators, teachers, and external observers regarding Outdoor Learning activities?

2. Methodology

- Le Mons Memorial Museum—https://musees-expos.mons.be/nos-lieux/mons-memorial-museum/mons-memorial-museum (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Pairi Daiza (Nature and Wildlife Park)—https://www.pairidaiza.eu/fr/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- SPARKOH! (Science Center)—https://sparkoh.be (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Doudou Museum—https://musees-expos.mons.be/fr/nos-lieux/musee-du-doudou (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Beffroi Museum—https://musees-expos.mons.be/fr/nos-lieux/beffroi (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Grand-Hornu—https://www.grand-hornu.eu/fr (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Nezahat Tokyoite Botanical Garden—https://www.ngbb.org.tr/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Topkapı Palace—https://www.millisaraylar.gov.tr/Lokasyon/2/topkapi-sarayi (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Museum of the History of Science and Technology—https://muze.gov.tr/muze-detay?SectionId=IBT01&DistId=MRK (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Naval Museum—https://www.turkishmuseums.com/museum/detail/22321-istanbul-deniz-muzesi/22321/1 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Dolmabahçe Palace—https://www.millisaraylar.gov.tr/Lokasyon/3/Dolmabahce-Sarayi (accessed on 10 May 2025).

3. Results

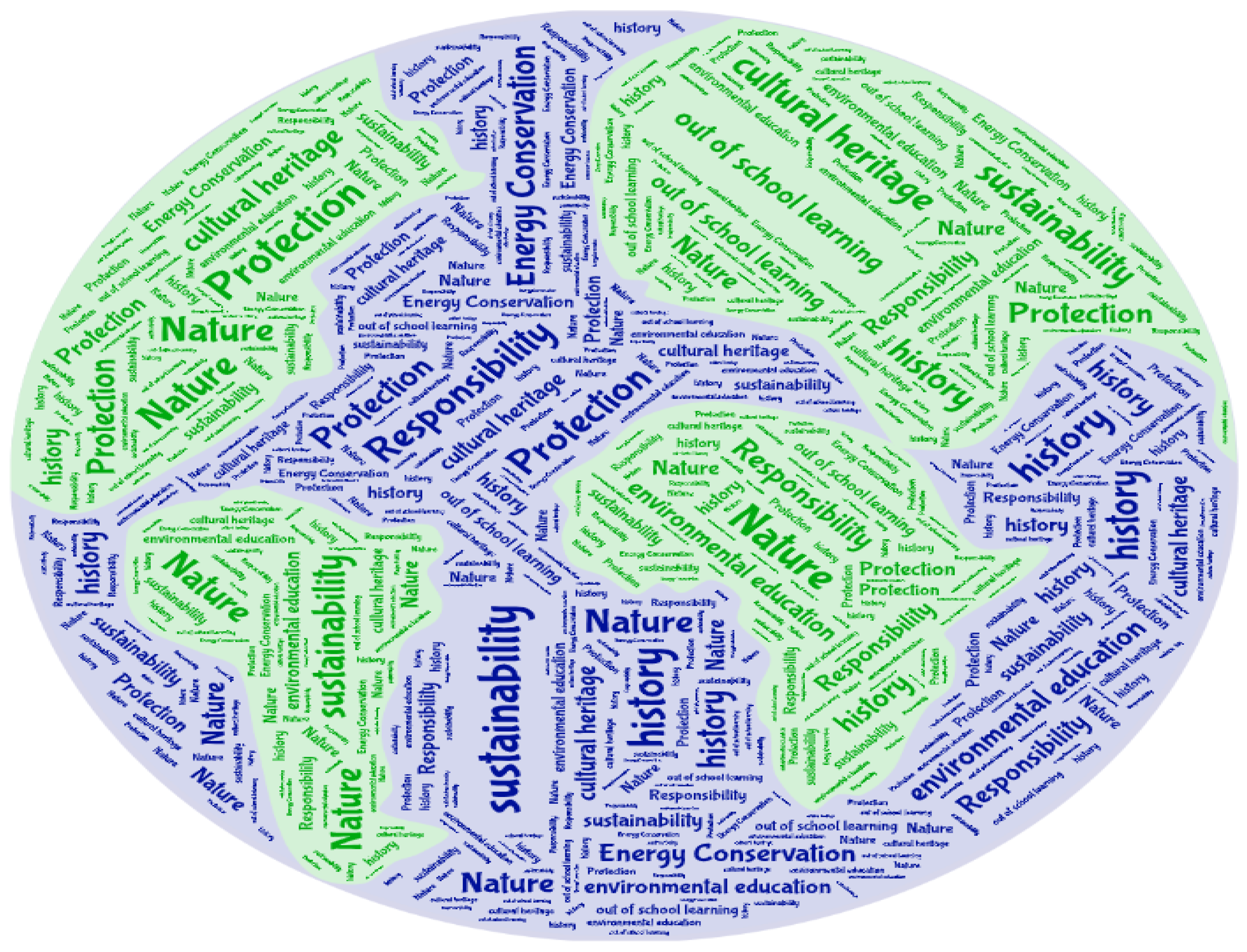

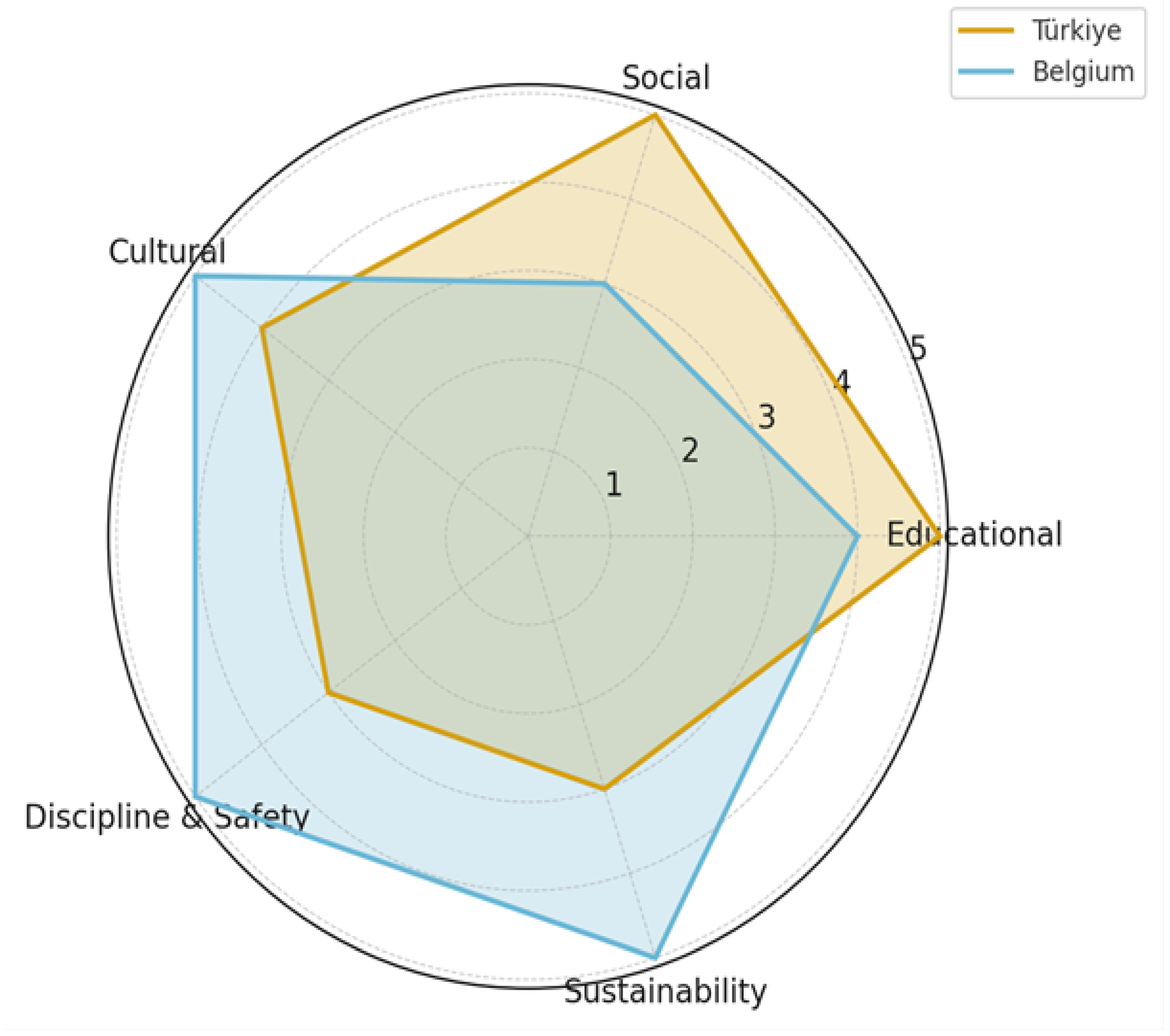

3.1. The Impact of Outdoor Learning Activities on Educational Sustainability

3.2. The Impact of Outdoor Learning Activities on Sensitivity to Cultural Heritage

3.3. Opinions of School Administrators, Teachers, and External Observers on Outdoor Learning Activities

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. The Role of Outdoor Learning in the Context of Sustainability

4.2. Strengthening Sensitivity to Cultural Heritage

4.3. Differences in Implementation and Systemic Challenges Between Türkiye and Belgium

- Implementation Systematics: In Belgium, OL practices are conducted more systematically and institutionally, supported by program integration and administrative frameworks. In Türkiye, the updated 2024 Maarif Curriculum [33] provided strong policy-level support. This parallels findings indicating that outdoor learning is more institutionalized in socioeconomically advanced countries [73,74]. The recent rise of guides, location inventories, and teacher facilitation efforts in Türkiye reflects growing institutional initiatives in this area.

- Implementation Challenges and Limitations: While teachers and administrators recognized OL’s pedagogical benefits, they also highlighted serious challenges such as safety, transportation, costs, crowded classrooms, logistics, and bureaucratic procedures. These obstacles, often noted in the literature [75,76], constrain OL’s potential. Overcoming them requires logistical support, teacher competence development, and policy-level institutional arrangements. The key limitations identified include large class sizes, lack of financial resources, transportation and logistics issues, and safety concerns. Moreover, when OL activities are conducted as one-time events, their long-term impact remains limited. Zhang et al. [77] emphasized the importance of sensory experiences in preserving cultural heritage.

4.4. Recommendations

- Integrate OL systematically into curricula, ensuring it becomes an organic and continuous component rather than a marginal activity.

- Provide in-service training for teachers focusing on the pedagogical, safety, and management aspects of OL. Training should center on sustainability and cultural heritage education.

- Enhance financial and logistical support to minimize challenges related to transportation, materials, and safety. Schools should be granted flexibility and funding to plan and implement activities.

- Address both tangible and intangible aspects of cultural heritage to instill in students a sense of collective identity and cultural consciousness.

- Develop standards for OL activities that ensure goal-oriented implementation, including pre- and post-activity preparation, site selection and diversity, and assessment tools measuring both academic and behavioral outcomes such as awareness and attitude change.

- As sustainability is a rather broad concept, environment and cultural heritage were focused in this study. Further research is recommended for intra-generational equity, gender equity, vulnerable groups and socioeconomic inequity within sustainability.

4.5. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bunting, C.J. Interdisciplinary Teaching Through Outdoor Education; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- SAPOE. Curriculum Beyond the Classroom: Our Strategy for 2024–2029. 2023. Available online: https://sapoe.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/sapoe-strategy-document-2024-2029.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- ETBI. ETB Outdoor Education and Training Provision: A Strategic Framework for the Sector 2021–2023. 2022. Available online: https://www.etbi.ie/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/FET-Outdoor-Education-Training-12.11.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Maynard, T.; Waters, J.; Clement, J. Moving outdoors: Further explorations of ‘child-initiated’ learning in the outdoor environment. Educ. 3–13 2013, 41, 282–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylward, T.; Coulter, M.; Farrelly, T. Outdoor learning on the edge of Europe: A systematic review of practices in Ireland. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2025, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. School field trips: Assessing their long-term impact. Curator Mus. J. 1997, 40, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. Experience and Education; Macmillan/Kappa Delta Pi: New York, NY, USA, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Rotaru, C. The triad: Grundtvig, Haret, Gusti—Outdoor education in the history of international pedagogy. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 142, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, D.R. Outdoor educators: The need to become credible. J. Environ. Educ. 1982, 14, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alleman, J.; Brophy, J. Taking advantage of out-of-school opportunities for meaningful social studies learning. Soc. Stud. 1994, 85, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foran, A. An outside place for social studies. Can. Soc. Stud. 2008, 41, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshach, H. Bridging in-school and out-of-school learning: Formal, non-formal, and informal education. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2007, 16, 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrendt, M.; Franklin, T. A review of research on school field trips and their value in education. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2014, 9, 235–245. [Google Scholar]

- Şimşek, A.; Kaymakçı, S. Okul Dışı Sosyal Bilgiler Öğretiminin Amacı ve Kapsamı. In Okul Dışı Sosyal Bilgiler Öğretimi; Şimşek, A., Kaymakçı, S., Eds.; Pegem Akademi: Ankara, Türkiye, 2015; pp. 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Beames, S.; Higgins, P.; Nicol, R.; Smith, H. Outdoor Learning Across the Curriculum: Theory and Guidelines for Practice, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Küçük, S. Environmental education and outdoor learning. J. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 16, 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Vivier, M.; Lee, J. Outdoor learning and environmental literacy. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 1250–1266. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.R. Environmental learning in informal contexts: Field trips to natural history museums. J. Mus. Educ. 2021, 46, 345–359. [Google Scholar]

- Uğurlu, A.; Sever, R. Examining the Anxiety Levels of Classroom Teachers Regarding Out-of-School Learning Environments. İnönü Univ. J. Fac. Educ. 2024, 25/2, 670–690. [Google Scholar]

- Özdemir, L.A. Views of Pre-Service Science Teachers About Informal Learning Environments Before and After Science and Technology Museum Visit. Master’s Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Türkiye, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Richmond, D.; Sibthorp, J.; Gookin, J.; Annarella, A.; Ferri, S. Complementing classroom learning through outdoor adventure education: Out-of-school time experiences that make a difference. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2017, 18, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernholm, M. Children’s out-of-school learning in digital gaming communities. Des. Learn. 2021, 13, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktaş, V.; Tokmak, A.; İlhan, G.O. Improving sensitivity to cultural heritage through out-of-school learning activities. Particip. Educ. Res. 2025, 12, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özyıldırım, H.; Durmaz, H. The effect of an interdisciplinary field trip on pre-service teachers’ attitudes toward outdoor learning activities. Trak. J. Educ. 2022, 12, 522–541. [Google Scholar]

- Taytaş, G. Evaluation of school trips based on teachers’ opinions. J. Int. Educ. Res. 2022, 2, 389–425. [Google Scholar]

- Ürey, M.; Kaymakçı, S. Elementary school teachers’ perceptions about out-of-school environments and applications in life studies course. Milli Eğitim 2020, 49, 7–32. [Google Scholar]

- Acar, L. Examination of Science Teachers’ Views About Out of School Learning Environments and Their Use of These Environments. Master’s Thesis, Trabzon University, Trabzon, Türkiye, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksson, A.-C. Primary school teachers’ perceptions of out-of-school learning within science education. LUMAT Int. J. Math Sci. Technol. Educ. 2018, 6, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W. Using process drama in museum theatre educational projects to reconstruct postcolonial cultural identities in Hong Kong. J. Appl. Theatre Perform. 2014, 19, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgriff, M. The reconceptualisation of outdoor education in the primary school classroom in Aotearoa New Zealand: How might we do it? Educ. 3–13 2015, 4, 2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Norodahl, K.; Johannesson, I.A. Children’s outdoor environment in Icelandic educational policy. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2015, 59, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of National Education (MEB). Outdoor Learning Guide; Ministry of National Education Publications: Ankara, Türkiye, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of National Education (MEB). Maarif Curriculum Report/2024 Detailed Maarif Curriculum Report; Ministry of National Education: Ankara, Türkiye, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Aktaş, V.; Yılmaz, A.; İlhan, G.O. Developing the spatial thinking skill scale in the scope of social studies teaching. RumeliDE J. Lang. Lit. Stud. 2023, Ö13, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubat, U. Science teacher candidates’ opinions about out-of-school learning environments. Mehmet Akif Ersoy Univ. J. Educ. Fac. 2018, 48, 111–135. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2003; Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Kara, İ.; Tokmak, A. The place and importance of social studies in teaching natural and cultural heritage. Nevşehir Hacı Bektaş Veli Univ. J. Soc. Sci. Inst. 2023, 13, 177–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D. Culturally sustainable development: Theoretical concept or practical policy instrument? Int. J. Cult. Policy 2017, 23, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, E. The Impact of Cultural Heritage on the Formation of Sustainable Destination Image: The Example of Istanbul Kalkhedon. Master’s Thesis, Kapadokya University, Nevsehir, Türkiye, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Auclair, E.; Fairclough, G. Theory and Practice in Heritage and Sustainability: Between Past and Future; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Soini, K.; Svels, K.; Abernethy, P.; Jokinen, M.; Ojala, A. Socially and Culturally Sustainable Natural Resource Governance (SOCCA). Luonnonvarakeskus (Luke): Helsinki, Finland,, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. Tourism Highlights; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2014; Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/epdf/10.18111/9789284416226 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Duxbury, N.; Hosagrahar, J.; Pascual, J. Why must culture be at the heart of sustainable urban development? Urban Sustain. 2021, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Çengelci, T. Cultural heritage education in social studies courses: Teachers’ views and experiences. Eğitim Bilim 2012, 37, 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Thurley, S. Into the Future. Our Strategy for 2005–2010. Conserv. Bull. 2005, 49, 26–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dönmez, C.; Yeşilbursa, C.C. The effect of cultural heritage education on attitudes toward tangible heritage. İlköğretim Online 2014, 13, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, D.J.; Seymour, J. Heritage education: Approaches and experiences. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2004, 10, 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Europa, N. Heritage and Education: A European Perspective. The Hague Forum 2004. Available online: http://www.europanostra.org (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Barghi, R.; Rahimian, M.; Ranjbar, V. Heritage education and sustainable cultural development. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 7, 298–314. [Google Scholar]

- WCED. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ismagilova, G.N.; Safiullin, L.N.; Bagautdinova, N.G. Tourism development in the region based on historical heritage. Life Sci. J. 2014, 11, 363–367. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Whitford, M.; Arcodia, C. Development of intangible cultural heritage as a sustainable tourism resource: The intangible cultural heritage practitioners’ perspectives. In Authenticity and Authentication of Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 34–47. [Google Scholar]

- Pai, C.H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.L.; Li, K.; Shang, Y. Current challenges and opportunities in cultural heritage preservation through sustainable tourism practices. Curr. Issues Tour. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, D. Proposing a sustainable marketing framework for heritage tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soini, K.; Birkeland, I. Cultural sustainability and heritage: From policy to practice. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021, 64, 1514–1530. [Google Scholar]

- Giliberto, F.; Labadi, S. Harnessing cultural heritage for sustainable development: An analysis of three internationally funded projects in MENA countries. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2022, 28, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soper, A.K. Developing Mauritianness: National Identity, Cultural Heritage Values and Tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2007, 2, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehia, E.F.; Ali Amer Alkhashil, M. The Power of Digital Storytelling in Preserving Saudi Cultural Heritage and Fostering National Identity. Herit. Soc. 2025, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Guo, W.; Xu, T. Heritage memory and identity: The central role of residents’ topophilia in cultural heritage tourism development. Curr. Issues Tour. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberle, E.; Zeni, M.; Munday, F.; Brussoni, M. Support factors and barriers for outdoor learning in elementary schools: A systemic perspective. Am. J. Health Educ. 2021, 52, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokuş, G. Integrating Outdoor School Learning Into Formal Curriculum: Designing Outdoor Learning Experiences and Developing Outdoor Learning Framework For PreService Teachers. Int. J. Educ. Technol. Sci. Res. 2020, 5, 1330–1388. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, A.; Şimşek, H. Qualitative Research Methods in Social Sciences; Seçkin Publications: Ankara, Türkiye, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, R.; Mou, S. Outdoor education for sustainable development: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, B. Advances, hotspots, and trends in outdoor education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jekel Könnel, E.; Geuer, L.; Schlindwein, A.; Perret, S.; Ulber, R. The effects of an outdoor learning program “GewässerCampus” in the context of environmental education. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, J.; Pedretti, E. Educators’ perceptions of bringing students to environmental consciousness through engaging outdoor experiences. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 22, 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauterbach, G. “Building Roots”—Developing Agency, Competence, and a Sense of Belonging through Education outside the Classroom. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M. Bichronous modes in heritage education for enhancing motivation and learning outcomes via the ARCS model. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labadi, S. Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Development: A Framework for Action; UCL Press: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lumby, J. Enjoyment and learning: Policy and secondary school learners’ experience in England. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 37, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blunsdon, B.; Reed, K.; McNeil, N.; McEachern, S. Experiential Learning in Social Science Theory: An investigation of the relationship between student enjoyment and learning. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2003, 22, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNew-Birren, J.; Gaul-Stout, J. Understanding scientific literacy through personal and civic engagement: A citizen science case study. Int. J. Sci. Educ. Part B 2022, 12, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, T.; Martin, P. The role and place of outdoor education in the Australian National Curriculum. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2012, 16, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Dolah, J. Mobile-enhanced outdoor education for Tang Sancai heritage tourism: An interactive experiential learning approach. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ürey, M.; Kaymakçı, S. Primary school teachers’ views on the use and implementation of out-of-school learning environments in life sciences courses. Milli Eğitim Derg. 2020, 49, 7–32. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksson, C. Teachers’ challenges in outdoor learning. Educ. Inq. 2018, 9, 143–160. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, L.; Cai, C.; Furuya, K. Toward sustainable and differentiated protection of cultural heritage: A multisensory analysis of Suzhou and Kyoto using deep learning. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frances, L. It makes me a better teacher: The benefits of outdoor education. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2025, 25, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akarsu, A.H. Beyond the walls: Investigating outdoor learning experiences of social studies teacher candidates in Türkiye. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2025, 154, 104876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Participants | N | Gender (F/M) | Age | Level of Education |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Türkiye | Students | 40 | 17F/23M | 11–12 | 5th grade |

| Teachers (social studies teachers) | 5 | 3F/2M | F: 39, 45, 46/M: 35, 41 | Bachelor’s degree | |

| School Principals | 3 | 0F/3M | 46, 49, 50 | Bachelor’s degree | |

| Exterior Observers | 2 | 1F/1M | F: 31/M: 29 | F: PhD candidate/M: Master’s degree | |

| Belgium | Students | 37 | 17F/20M | 11–12 | 5th grade |

| Teachers (history and geography teachers) | 4 | 3F/1M | F: 41, 45, 46/M: 44 | Master’s degree | |

| School Principals | 2 | 0F/2M | 45, 48 | Master’s degree | |

| Exterior Observers | 2 | 1F/1M | F: 32/M: 35 | F: PhD student/M: PhD |

| Country | Theme | Sub-Themes | Codes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Türkiye | Sustainability | Environmental Sustainability | Awareness of nature |

| Conservation of natural resources | |||

| Importance of biodiversity | |||

| Social Sustainability | Respect for cultural heritage | ||

| Social awareness | |||

| Learning local values | |||

| Empathy and sense of responsibility | |||

| Cultural and Educational Sustainability | Preservation of historical and cultural values | ||

| Gaining experience through out-of-school learning environments | |||

| Lifelong learning | |||

| Emotional and Personal Sustainability | Self-awareness and self-confidence | ||

| Curiosity and desire for exploration | |||

| Stress management and interaction with nature | |||

| Belgium | Climate Change Awareness and Green Transition | Reducing carbon footprint | |

| Participation in climate actions | |||

| Zero-waste culture | |||

| Multicultural Heritage and European Identity | Common European culture | ||

| Building local–international connections | |||

| Linguistic diversity | |||

| Innovative Learning and Urban Space Utilization | Science and technology parks | ||

| Urban learning spaces | |||

| Awareness of sustainable urbanism | |||

| Personal Initiative and Autonomy | Taking individual responsibility | ||

| Autonomy in learning | |||

| Willingness to innovate |

| Metaphor | Student Justification (In Their Own Words) |

|---|---|

| TR1—Sustainability is the breath of life. | I realized that protecting nature and resources is essential for life. |

| TR8—Sustainability is the compass of nature. | I understood that humans must live in balance with nature. |

| TR11—Environmental protection is the wings of life. | I thought that protecting nature makes the lives of both humans and living beings sustainable. |

| TR15—Sustainability is the window opening to the future. | I believed that protecting the environment means leaving a better world for children. |

| BE2—Sustainability is like the roots of a tree. | I thought that strong foundations are needed for future generations to grow up in a healthy environment. |

| BE5—Energy saving is the insurance of life. | I realized that unnecessary energy consumption will have negative effects in the future. |

| BE7—Forests are the lungs of the Earth. | I understood that protecting trees and green areas is vital for life. |

| Country | Theme | Sub-Themes | Codes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Türkiye | Sensitivity to Cultural Heritage | Awareness and Consciousness | Historical awareness |

| Connection with the past | |||

| Cultural awareness | |||

| Protection and Responsibility | Preservation of historical artifacts | ||

| Continuation of cultural elements | |||

| Restoration | |||

| Transmission to future generations | |||

| Identity and Belonging | National identity | ||

| Collective memory | |||

| Connection with local culture | |||

| Preservation and Transmission | Traditional arts | ||

| Oral culture (tales, folk songs, epics) | |||

| Environmental and Natural Heritage | Protection of natural beauty | ||

| Awareness of historical environment | |||

| Belgium | Awareness of European Cultural Heritage | Awareness of shared European history | |

| Awareness of multilingual heritage | |||

| Multiculturalism and Coexistence | Awareness of cultural diversity in history | ||

| Connection with contemporary multicultural life | |||

| On-Site Learning and Participation | Contact with local heritage | ||

| Participatory learning | |||

| Cultural Identity and European Citizenship | Linking local identity with European identity | ||

| Connection with the past | |||

| Intangible Cultural Heritage and Linguistic Diversity | Festivals and traditions | ||

| Linguistic diversity and cultural transmission |

| Metaphor | Student Justification (In Their Own Words) |

|---|---|

| TRS9—Bridge | “A bridge connects the past and the future. If we destroy the bridge, the two sides are separated, and we become detached from our roots.” |

| TRS26—Tree | “Its roots are in the past, and its branches reach into the future. If we don’t water those roots, the tree dries up—meaning our culture disappears.” |

| TRS6—Carpet | “Each motif tells a story. If one thread breaks, the whole pattern is ruined, meaning culture loses its values.” |

| BES12—Compass | “Because a compass helps us find our direction. Our culture shows us who we are and where we came from.” |

| BES11—Mirror | “Because it shows us who we are. If we don’t look at it, we cannot recognize ourselves.” |

| BES25—Clock | “It shows the past, the present, and the future together. If the clock breaks, we cannot tell the time; if culture breaks, we cannot understand the past.” |

| BES13–Treasure Chest | “It holds priceless values inside. If we do not take care of it, these treasures will be stolen or lost.” |

| Country | Theme | Sub-Themes | Codes | f |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Türkiye | Educational Contributions | Permanence of learning | Concretization of knowledge, learning through experience, complement to lessons | 3 |

| Application of theoretical knowledge | Field experience, observation, extension of the lesson | 2 | ||

| Contribution to the curriculum | Complementary tool, natural extension, permanent learning | 3 | ||

| Social Contributions | Communication and cooperation | Teamwork, sharing, empathy, acting together | 3 | |

| Development of social skills | Strengthening friendship ties, taking responsibility, solidarity | 3 | ||

| Belgium | Cultural Contributions | Cultural awareness | Recognition of historical and cultural sites, learning about the past | 2 |

| Cultural belonging | Reinforcement of identity, values education, social responsibility awareness | 2 | ||

| Discipline and Safety | Planning and organization | Organization of transportation, responsibility of guide teachers, careful preparation | 1 | |

| Priority of safety | Student safety, behavior control, risk prevention | 2 | ||

| Sustainability | Regular and repeated activities | Not one-time only, being part of the program | 2 | |

| Long-term learning strategy | Continuity, development of awareness, persistence in learning | 2 |

| Country | Theme | Sub-Themes | f |

|---|---|---|---|

| Türkiye | Learning Experience and Permanence | Reinforcement of knowledge through field experience | 5 |

| Concretization of theoretical knowledge | 3 | ||

| Increased interest in lessons | 2 | ||

| Continuity of learning | 2 | ||

| Communication and Cooperation | Development of communication skills | 4 | |

| Teamwork and taking responsibility | 3 | ||

| Empathy and sharing | 2 | ||

| Strengthening of friendship bonds | 3 | ||

| Belgium | Cultural Awareness and Belonging | Recognition of cultural heritage | 5 |

| Development of historical awareness | 3 | ||

| Awareness of social responsibility | 2 | ||

| Strengthening sense of identity and belonging | 3 | ||

| Organization and Risk Management | Safety measures | 5 | |

| Detailed planning | 4 | ||

| Discipline and behavior control | 4 | ||

| Guidance and sharing of responsibility | 2 | ||

| Planned and Continuous Practice | Regular and well-organized activities | 5 | |

| Permanent learning experience | 3 | ||

| Integration into the annual program | 2 | ||

| Avoidance of one-time activities | 3 |

| Dimension | External Observer 1 (BE) | External Observer 2 (TR) | External Observer 3 (BE) | External Observer 4 (TR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher | Took on a guiding role and provided opportunities for students to explore. | Could not give equal attention to all students due to the large group size. | Encouraged students’ curiosity through questions and supported inquiry. | Outdoor conditions made classroom management difficult, and some discipline issues occurred. |

| Student | Participated with motivation; cooperation and communication were strengthened. | Some students were distracted and could not fully engage in the process. | By connecting with real-life situations, they grasped knowledge more easily and enhanced social interaction. | Some students remained passive and could not benefit equally from the activity. |

| Process | The venue and materials enriched learning. | Noise and crowding negatively affected the process. | The harmony between content and environmental opportunities made learning more permanent. | Transportation and time management problems reduced the efficiency of the process. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

İlhan, G.O.; Tokmak, A.; Aktaş, V. Outdoor Learning in Belgium and Türkiye: Cultural Heritage Sensitivity and Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10849. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310849

İlhan GO, Tokmak A, Aktaş V. Outdoor Learning in Belgium and Türkiye: Cultural Heritage Sensitivity and Sustainability. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10849. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310849

Chicago/Turabian Styleİlhan, Genç Osman, Ahmet Tokmak, and Veysi Aktaş. 2025. "Outdoor Learning in Belgium and Türkiye: Cultural Heritage Sensitivity and Sustainability" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10849. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310849

APA Styleİlhan, G. O., Tokmak, A., & Aktaş, V. (2025). Outdoor Learning in Belgium and Türkiye: Cultural Heritage Sensitivity and Sustainability. Sustainability, 17(23), 10849. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310849