Identification of Local and Transboundary Sources and Mechanisms of PM2.5 and O3 Pollution on the Tibetan Plateau: Implications for Sustainable Air Quality Governance

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Develop an integrated MRG–HSW framework that couples statistical modeling with trajectory-based diagnostics;

- (2)

- Quantify the effects of local meteorological and emission-related factors on local pollutant concentrations;

- (3)

- Identify dominant source regions and transport pathways during high-pollution episodes;

- (4)

- Evaluate elevation-dependent mechanisms to support evidence-based and cooperative air-quality governance in complex plateau terrain.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Meteorological and Pollutant Data

2.2. Integrated Methodology: The MRG-HSW Attribution Framework

2.2.1. Local Attribution Block: MRG

- Meteorological factors model (Equation (1)): Excludes pollutant factors ;

- Pollutant factors model (Equation (1)): Excludes meteorological factors are excluded ;

- Combined factors model (Equation (1)): Includes both meteorological and pollutant factors ;

2.2.2. External Transport Block: HSW

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Variations of PM2.5 and O3

3.2. Local Attribution and Regression Model Performance

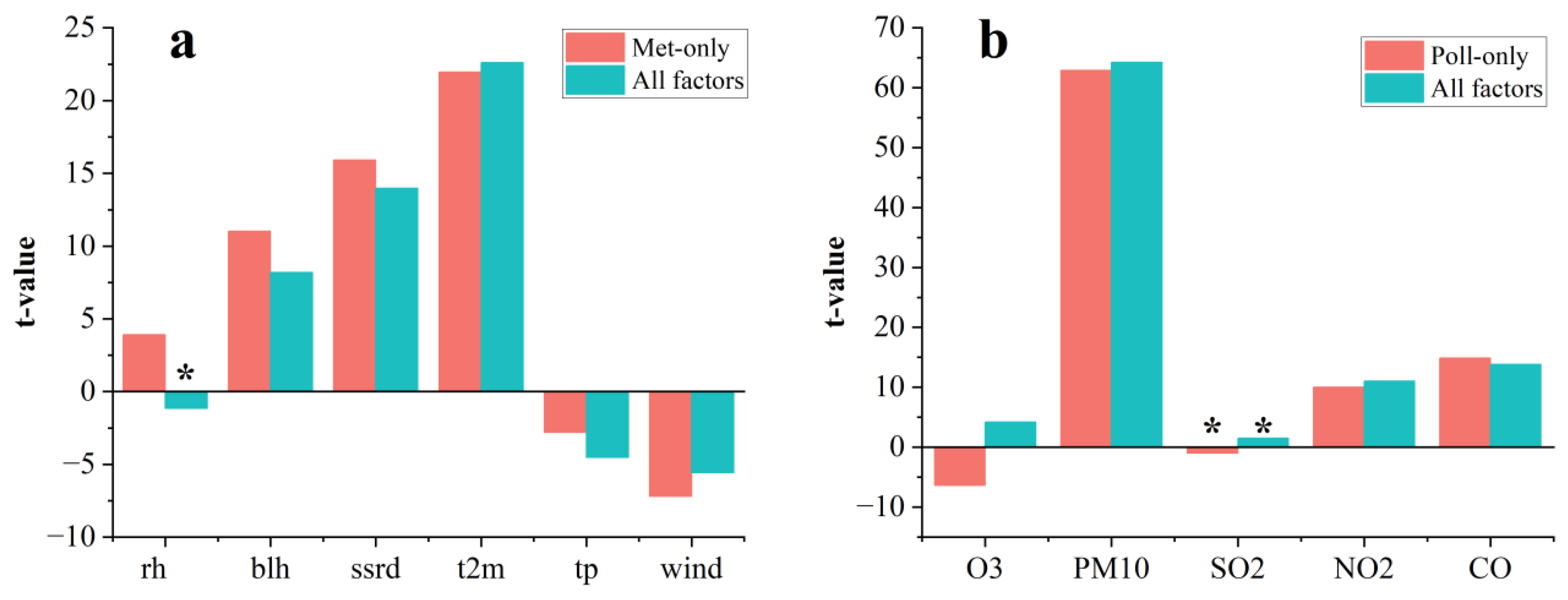

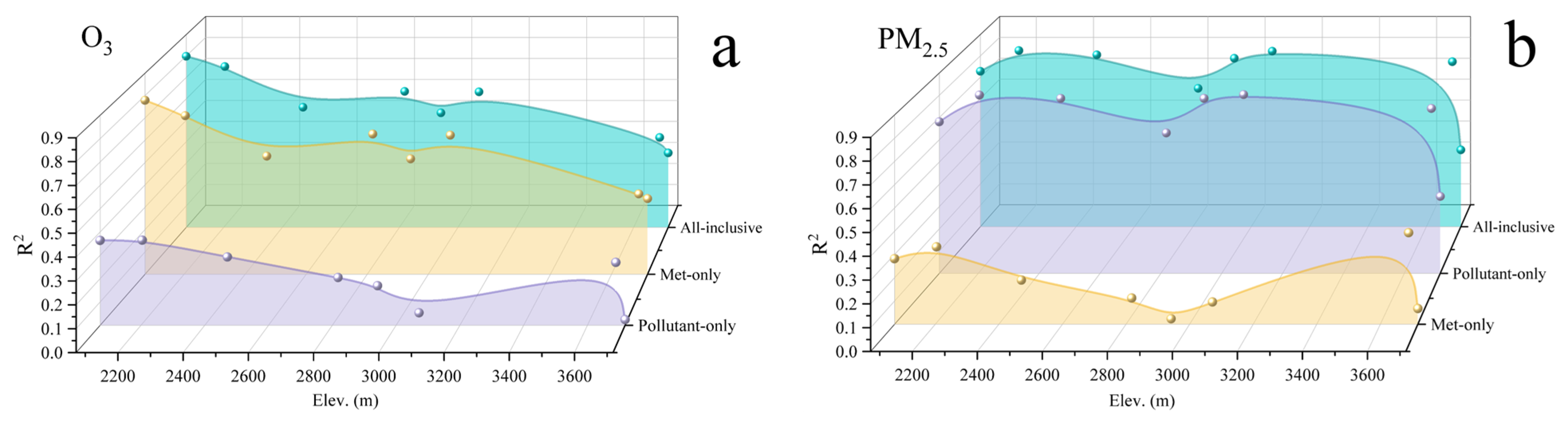

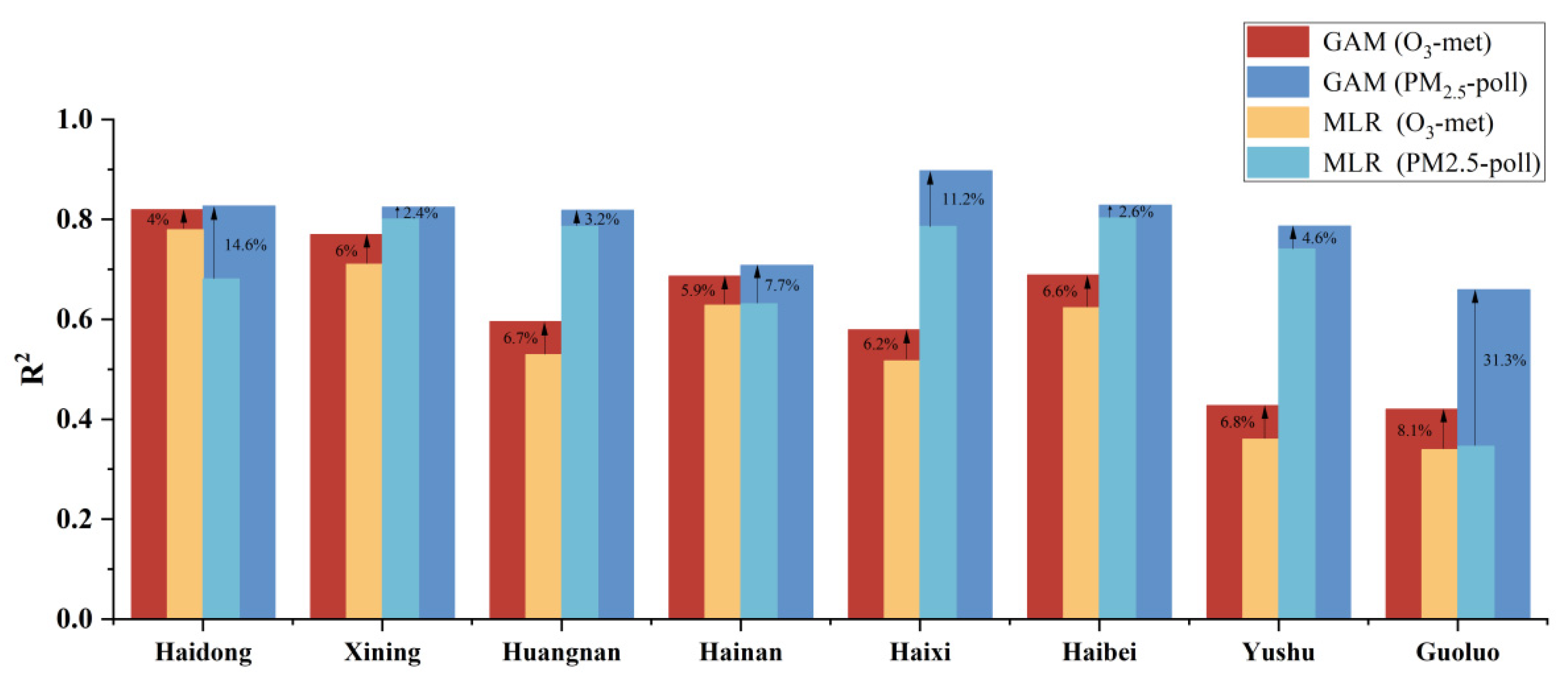

3.2.1. Linear Attribution with MLR

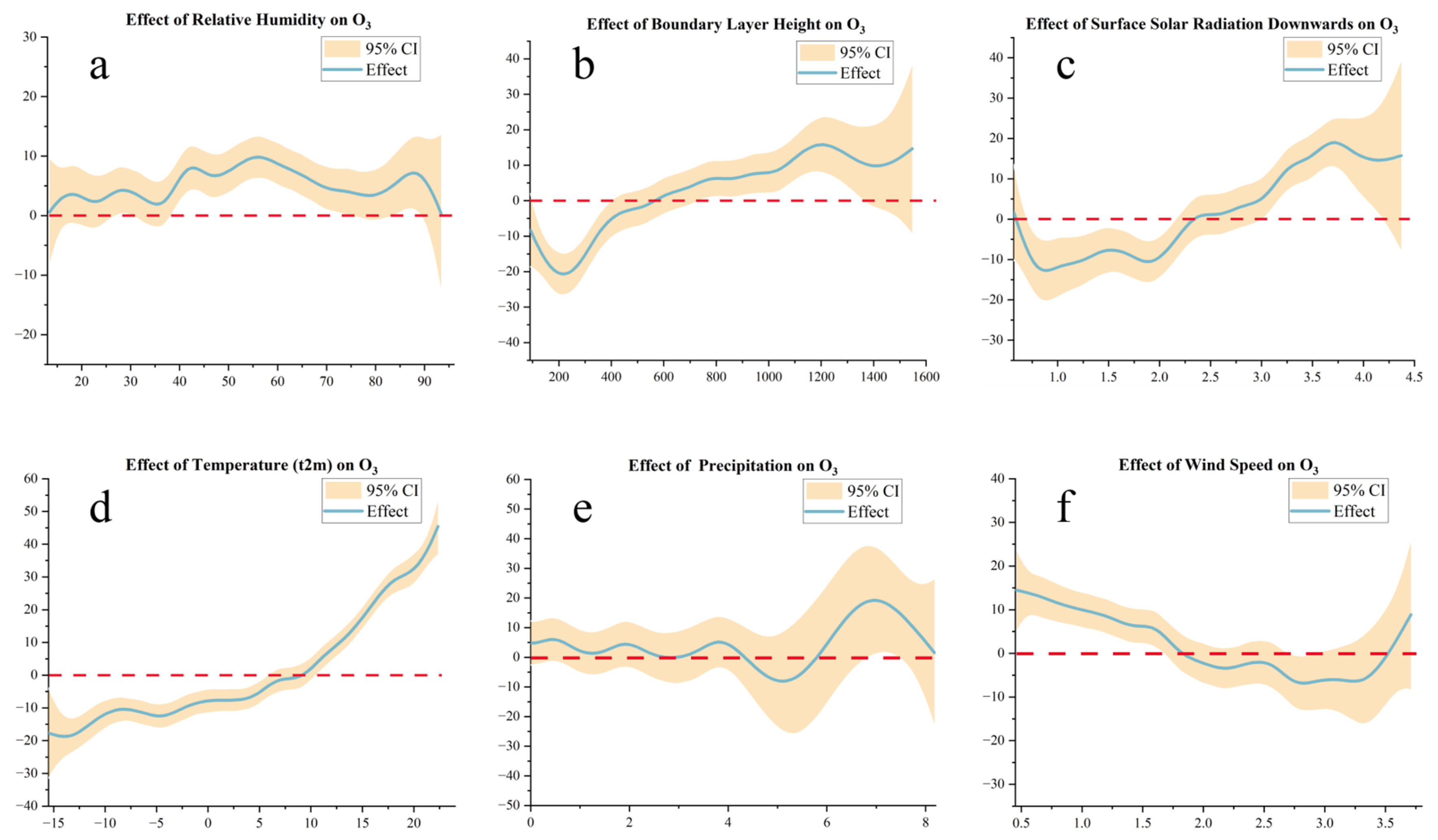

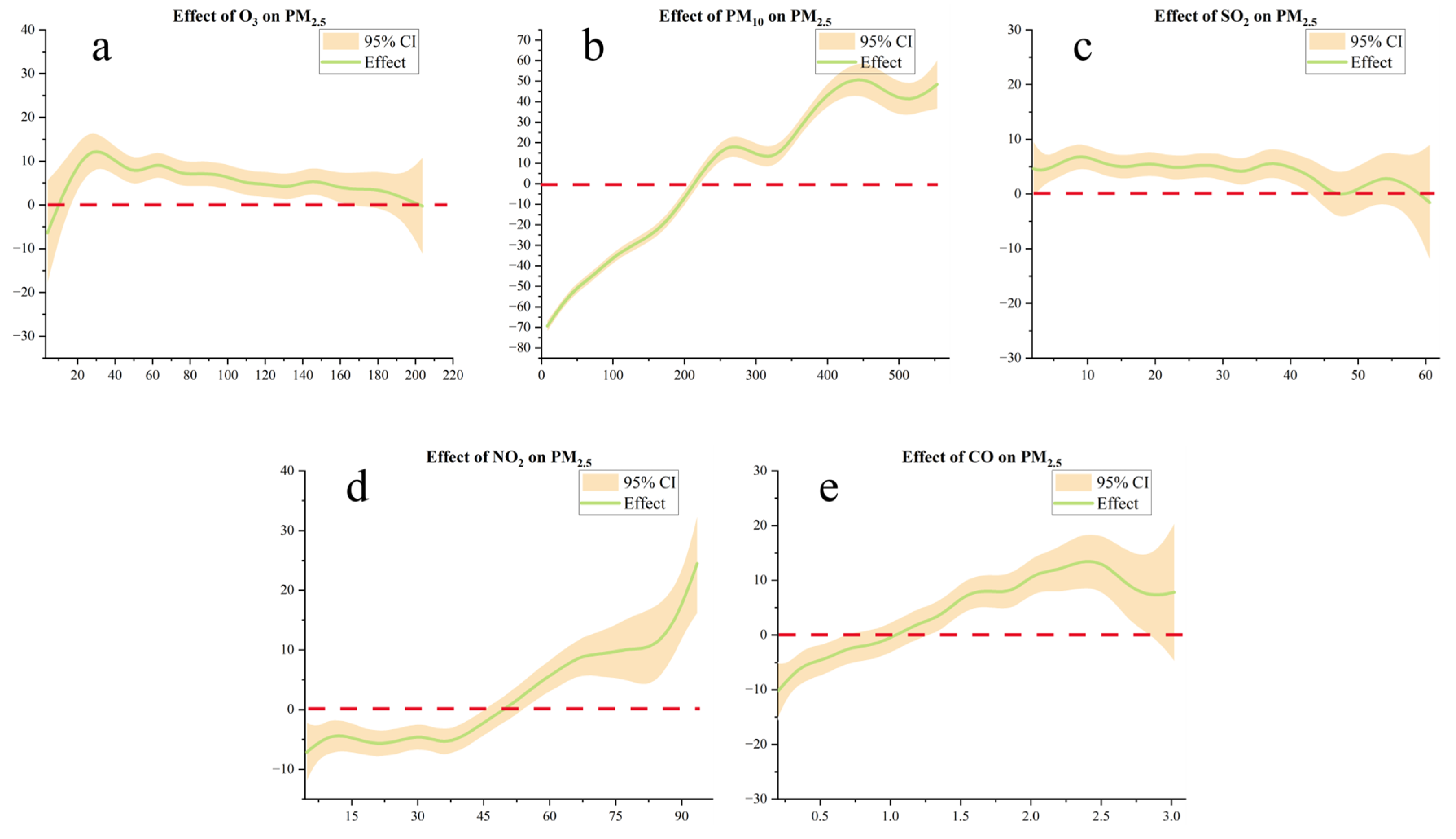

3.2.2. Nonlinear Supplementation with GAM

3.3. External Transport Analysis

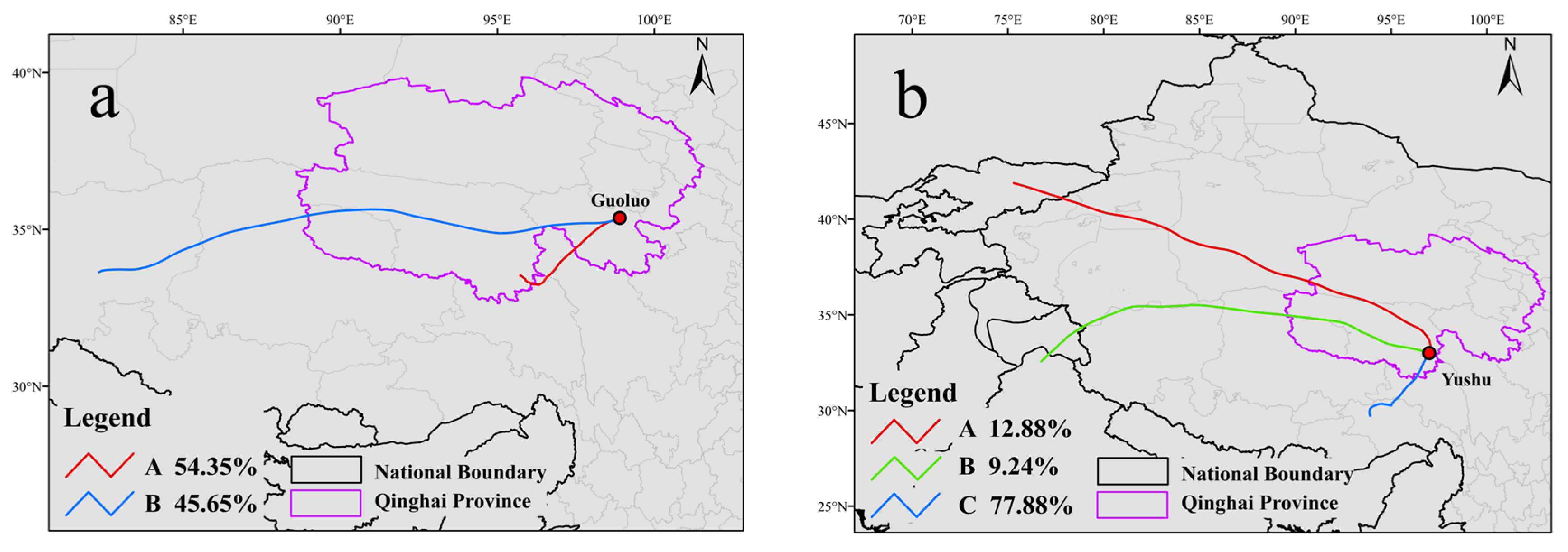

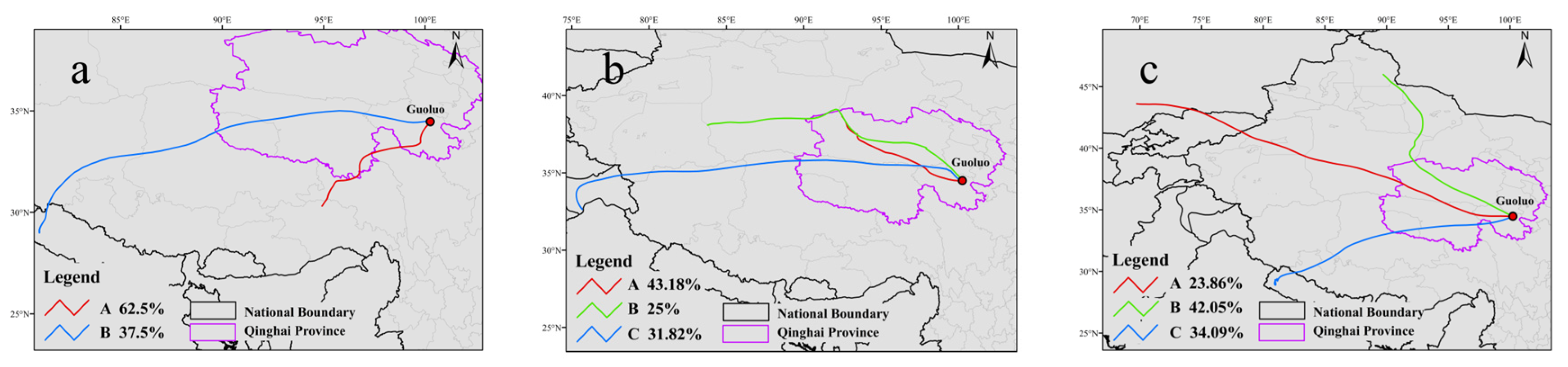

3.3.1. Trajectory Simulation, Clustering, and Source Pathway Analysis for Low-R2 Sites/Days

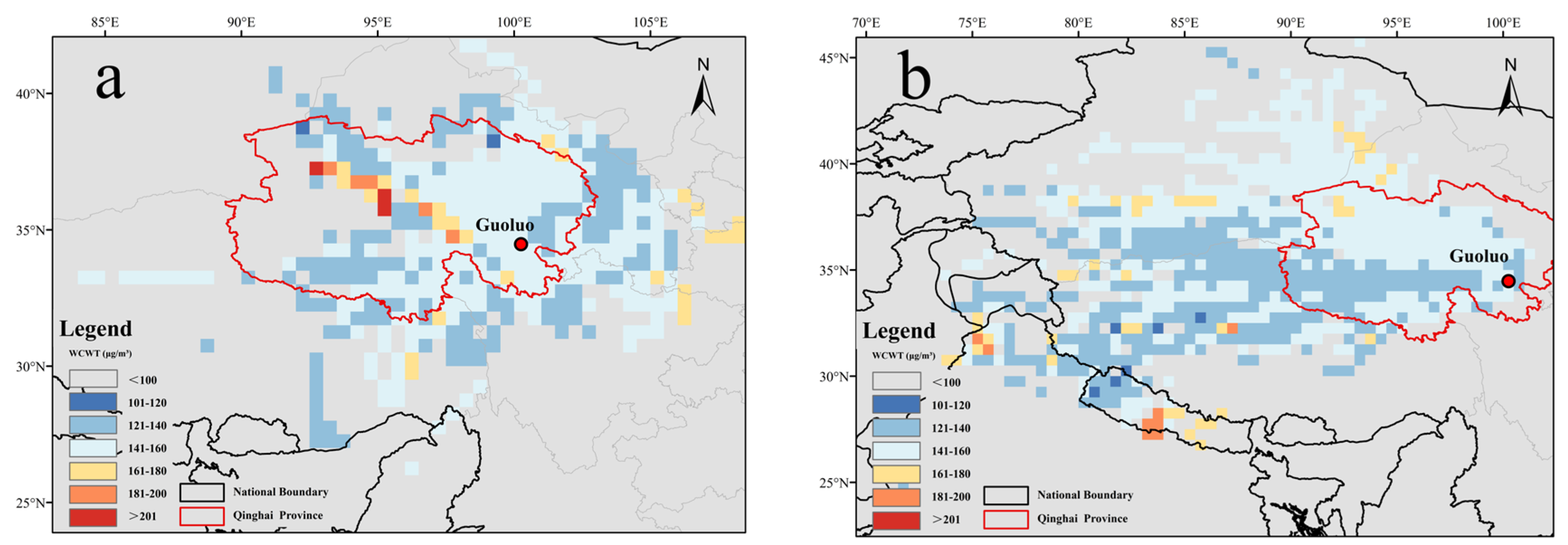

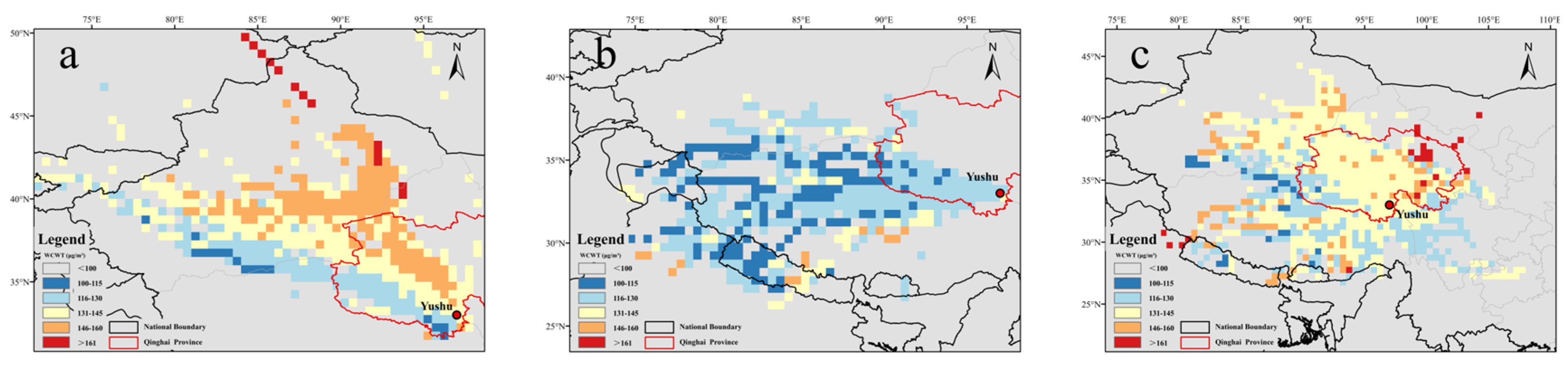

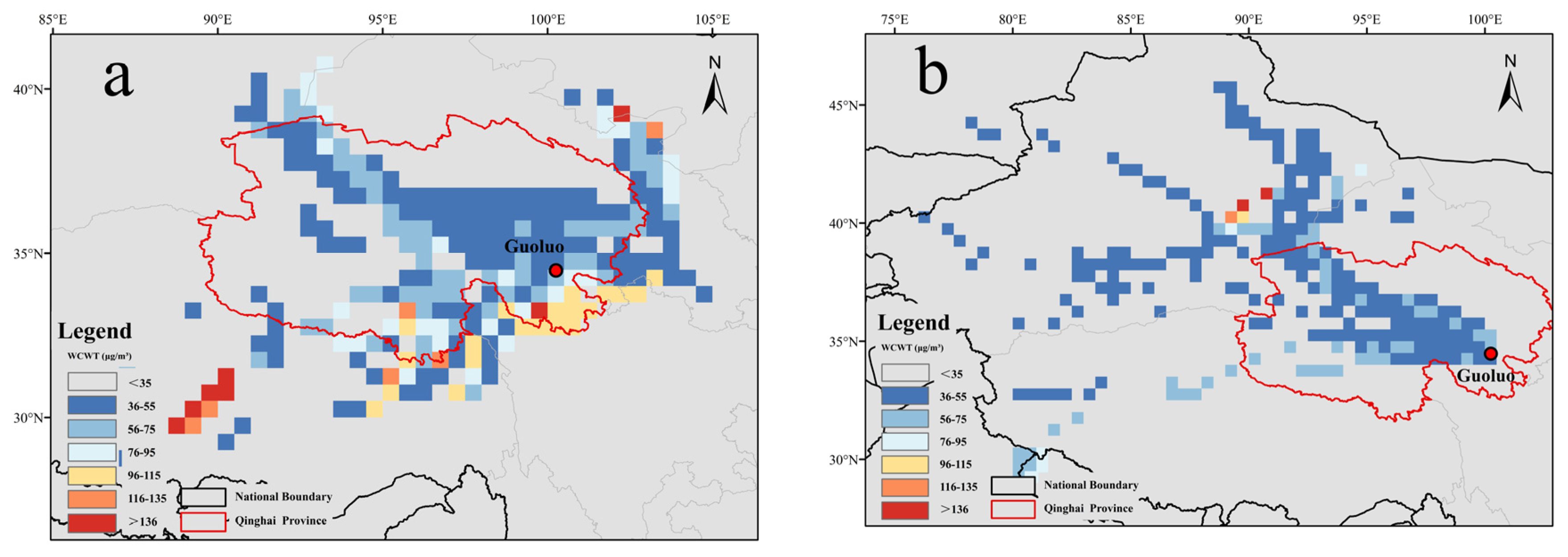

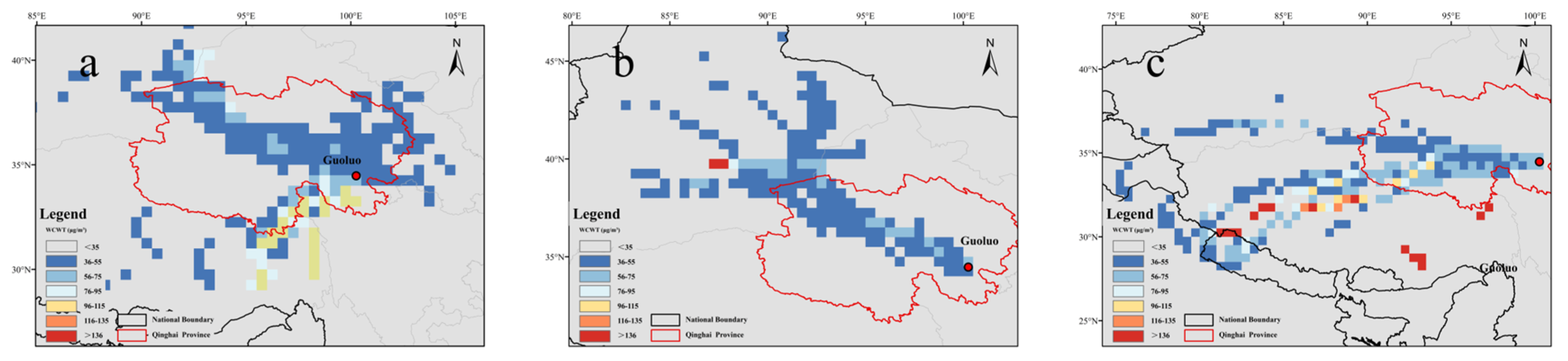

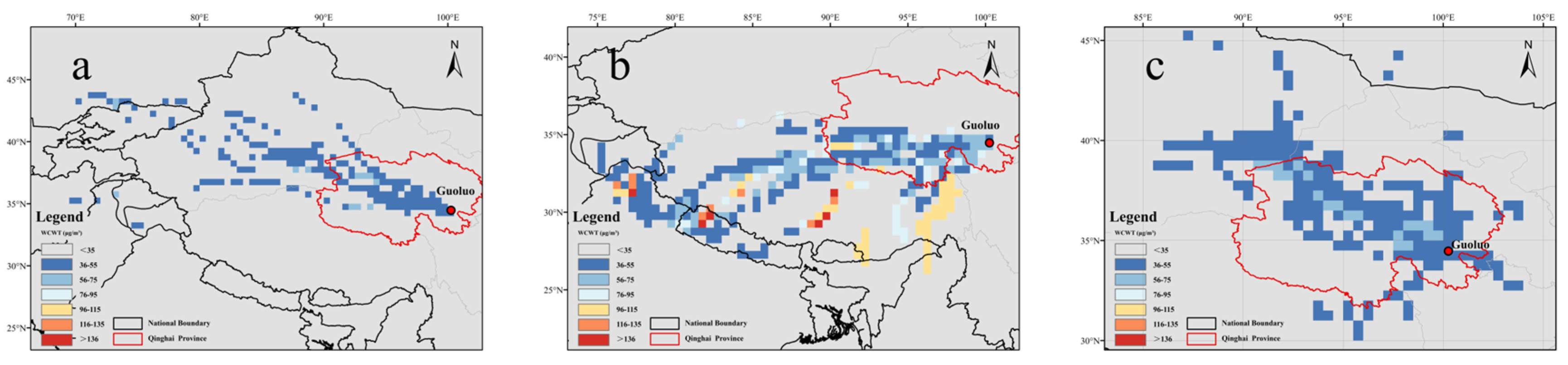

3.3.2. Spatial Identification of Potential Source Regions by WCWT

3.3.3. Case Study of Extreme Pollution Episodes and External Transport Characteristics

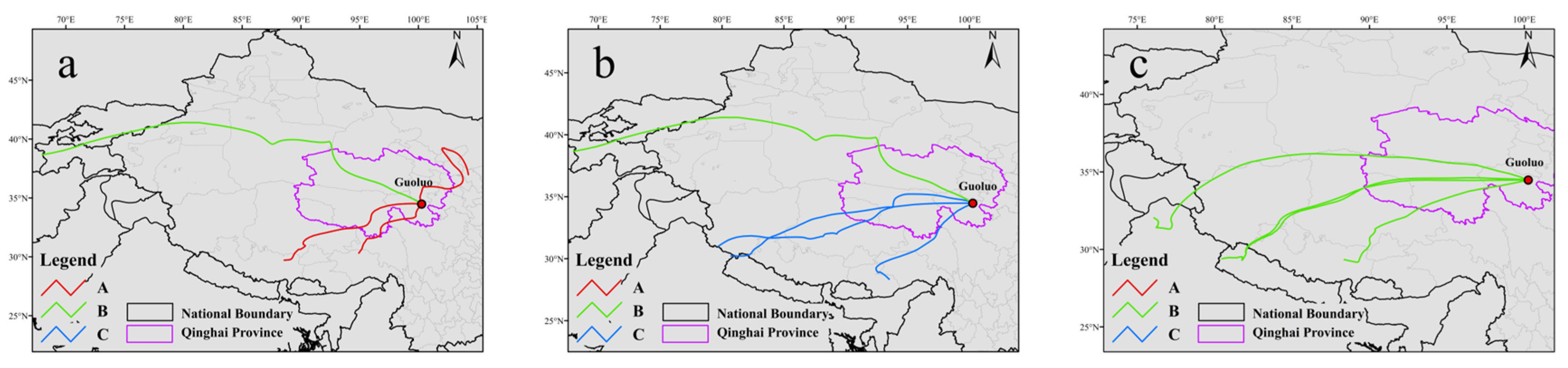

- Guoluo PM2.5 Pollution Episode (28 February 2021)

- 2.

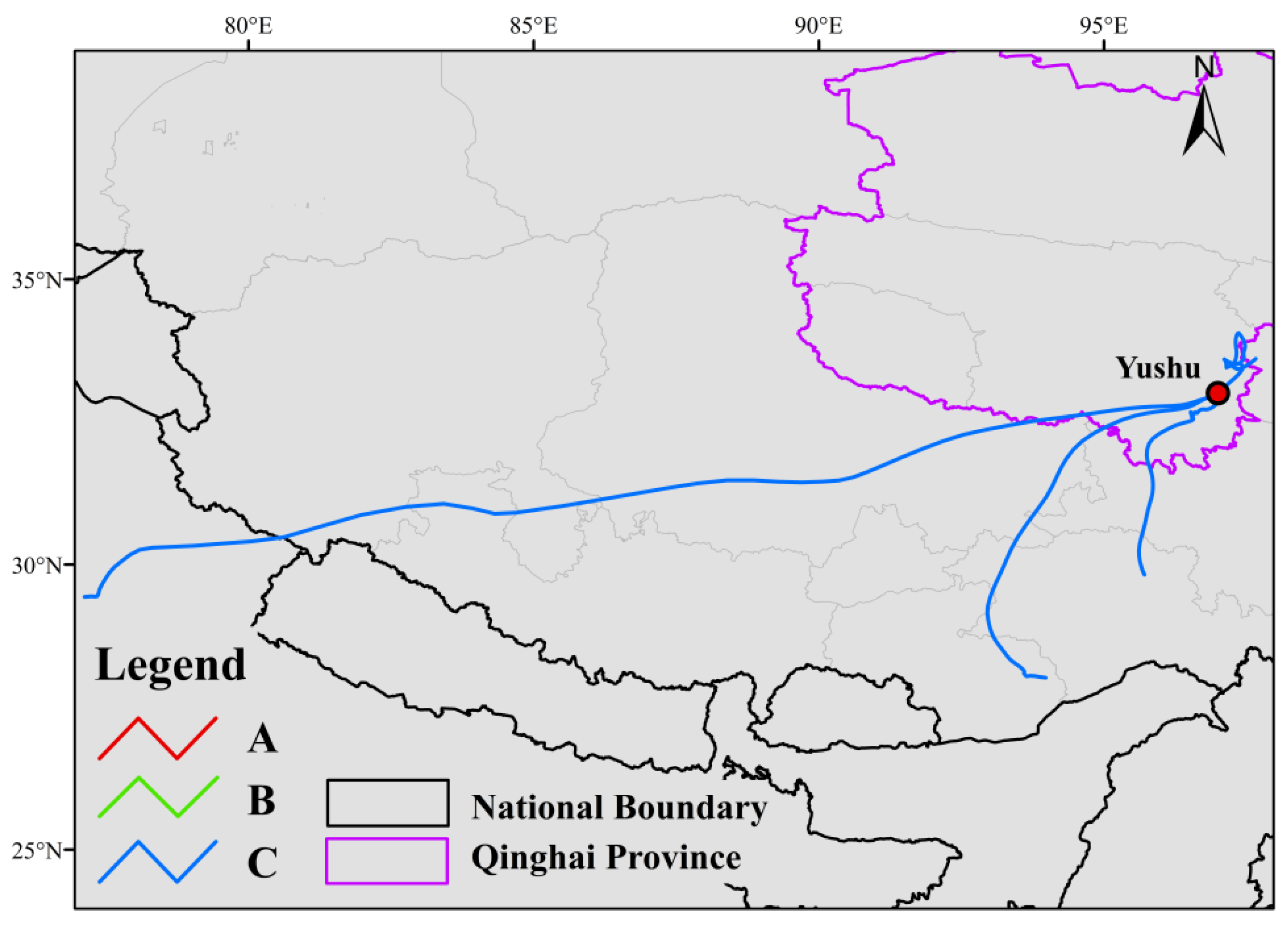

- Yushu O3 Pollution Episode (1 June 2024)

3.4. Integrated Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PM2.5 | Particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter less than 2.5 μm |

| O3 | Ozone |

| ERA5 | ECMWF Reanalysis v5 |

| GDAS | Global Data Assimilation System |

| CNEMC | China National Environmental Monitoring Center |

| MRG | Multiple Regression with residual-based screening and GAM |

| HSW | HYSPLIT–SOM–WCWT trajectory-based framework |

Appendix A

| City | R2 (O3–Meteorology) | R2 (O3–Pollutants) | R2 (O3–All Factors) | R2 (PM2.5–Meteorology) | R2 (PM2.5–Pollutants) | R2 (PM2.5–All Factors) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haibei | 0.623 | 0.054 | 0.633 | 0.096 | 0.803 | 0.822 |

| Huangna | 0.529 | 0.293 | 0.561 | 0.19 | 0.786 | 0.805 |

| Hainan | 0.628 | 0.205 | 0.635 | 0.113 | 0.631 | 0.648 |

| Guoluo | 0.339 | 0.025 | 0.348 | 0.068 | 0.346 | 0.36 |

| Yushu | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.42 | 0.394 | 0.741 | 0.773 |

| Haixi | 0.517 | 0.17 | 0.535 | 0.024 | 0.786 | 0.789 |

| Haidong | 0.779 | 0.364 | 0.799 | 0.282 | 0.681 | 0.728 |

| Xining | 0.71 | 0.365 | 0.751 | 0.333 | 0.801 | 0.825 |

References

- Lyu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wu, H.; Pang, X.; Qin, K.; Wang, B.; Ding, S.; Chen, D.; Chen, J. Tracking Long-Term Population Exposure Risks to PM2.5 and Ozone in Urban Agglomerations of China 2015–2021. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 854, 158599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ji, Y.; Yang, X.; Shi, J.; Xu, W.; Ma, J.; Shen, R.; Wang, B.; Zhang, J.; Feng, Y. Population Exposure Evaluation and Value Loss Analysis of PM2.5 and Ozone in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 376, 124480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Geng, G.; Xue, T.; Liu, S.; Cai, C.; He, K.; Zhang, Q. Tracking PM2.5 and O3 Pollution and the Related Health Burden in China 2013–2020. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 6922–6932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cheng, C.; Zhao, H. A Health Impact and Economic Loss Assessment of O3 and PM2.5 Exposure in China from 2015 to 2020. GeoHealth 2022, 6, e2021GH000531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, Q.; Qu, Y.; Wu, H.; Xie, M.; Li, M.; Li, S.; Zhuang, B. Spatiotemporal Variations of PM2.5 and O3 Relationship during 2014–2021 in Eastern China. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2023, 23, 230060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Yin, Z.; Cao, B.; Wang, H. Meteorological Influences on Co-Occurrence of O3 and PM2.5 Pollution and Implication for Emission Reductions in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2023, 66, 1258–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. China Ecological and Environmental Status Bulletin; Ministry of Ecology and Environment: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Chu, C. Assessing the Health Impacts Attributable to PM2.5 and Ozone Pollution in 338 Chinese Cities from 2015 to 2020. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 287, 117623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, T.; Wang, P.; Yu, W.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, D.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, H. Drivers of Alleviated PM2.5 and O3 Concentrations in China from 2013 to 2020. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 197, 107110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, B.; Li, R.; Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Tang, X.; Liu, J.; Liao, Z.; Xin, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Prediction of Daily PM2.5 and Ozone Based on High-Density Weather Stations in China: Nonlinear Effects of Meteorology, Human and Ecosystem Health Risks. Atmos. Res. 2023, 293, 106889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Zhang, C.; Liu, C.; Hu, Q. Variability of PM2.5 and O3 Concentrations and Their Driving Forces over Chinese Megacities during 2018–2020. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 124, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Ma, Y.; Feng, F.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, J.; Wang, H.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, Y. Influence of Weather and Air Pollution on Concentration Change of PM2.5 Using a Generalized Additive Model and Gradient Boosting Machine. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 255, 118437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Wang, Q.; Tan, T. Evaluating Drivers of PM2.5 Air Pollution at Urban Scales Using Interpretable Machine Learning. Waste Manag. 2025, 192, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jia, Z.; Yang, J.; Niu, B. Simulation and Prediction of PM2.5 Concentrations and Analysis of Driving Factors Using Interpretable Tree-Based Models in Shanghai, China. Environ. Res. 2025, 270, 121003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, W.; Wang, X.; Cheng, S.; Wang, R.; Zhu, J. Influencing Factors of PM2.5 and O3 from 2016 to 2020 Based on DLNM and WRF-CMAQ. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 285, 117512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Liu, H.; Peng, Z. Improving WRF-Chem PM2.5 Predictions by Combining Data Assimilation and Deep-Learning-Based Bias Correction. Environ. Int. 2025, 195, 109199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Väisänen, O.; Hao, L.; Virtanen, A.; Romakkaniemi, S. Trajectory-Based Analysis on the Source Areas and Transportation Pathways of Atmospheric Particulate Matter over Eastern Finland. Tellus B Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 2020, 72, 1799687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; He, Q.; Liu, X. Identification of Long-Range Transport Pathways and Potential Source Regions of PM2.5 and PM10 at Akedala Station, Central Asia. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.; Gao, B.; Li, S.; Yao, W.; Sun, W.; Cao, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, B. Pollution Characteristics, Potential Source Areas, and Transport Pathways of PM2.5 and O3 in an Inland City of Shijiazhuang, China. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2024, 17, 1307–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Song, X.; Zhong, G. Comparative Analysis of Three Methods for HYSPLIT Atmospheric Trajectories Clustering. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyana, M.R.; Aristiawan, Y.; Linggabinangkit, C.; Samodro, R.A.; Prasetia, H.; Fauziyyah, N.; Iswara, N.J.P.; Ega, A.V.; Prihhapso, Y. Urban Air Pollutant Mapping and Tracing Using Mobile In-Situ Measurements Combined with Clustering and Trajectory Analysis. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirwan; Siddiqui, A.; Shaeb, H.B.; Chauhan, P.; Singh, R.P. Gaseous Air Pollutants and Its Association with Stubble Burning: An Integrated Approach Using Ground and Satellite Based Datasets and Concentration Weighted Trajectory (CWT) Analysis. Res. Sq. 2023. published. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chham, E.; Orza, J.A.G. Evaluating the Impact of the Aerosol Sampling Time Interval on CWT and PSCF Source-Receptor Models: A Critical Perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 971, 179069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, D.; Xu, J.; Tan, H.; Zhou, M.; Henze, D.K. Assessing the Nonlinearity of Wintertime PM2.5 Formation in Response to Precursor Emission Changes in North China with the Adjoint Method. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 084048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Wang, S.; Xu, Q.; Ho, T. Source Apportionment Simulations of Ground-Level Ozone in Southeast Texas Employing OSAT/APCA in CAMx. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 253, 118370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irankunda, E.; Török, Z. Monitoring and Dispersion Modelling of Particulate Matter (PM2.5) in Rwanda. Aerosol Sci. Eng. 2025. published. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-C.; Song, H.-J.; Lee, C.-S.; Lim, Y.-J.; Ahn, J.-Y.; Seo, S.-J.; Han, J.-S. Characteristics and Source Identification for PM2.5 Using PMF Model: Comparison of Seoul Metropolitan Area with Baengnyeong Island. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttikunda, S.K.; Nishadh, K.A.; Gota, S.; Singh, P.; Chanda, A.; Jawahar, P.; Asundi, J. Air Quality, Emissions, and Source Contributions Analysis for the Greater Bengaluru Region of India. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2019, 10, 941–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Van Der, A.R.J.; Eskes, H.; Ding, J.; Mijling, B. Evaluation of Modeling NO2 Concentrations Driven by Satellite-Derived and Bottom-up Emission Inventories Using in Situ Measurements over China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 4171–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkurt, N.; Sari, D.; Akalin, N.; Hilmioglu, B. Evaluation of the Impact of SO2 and NO2 Emissions on the Ambient Air-Quality in the Çan–Bayramiç Region of Northwest Turkey during 2007–2008. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 456–457, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; Vinnikov, K.Y.; Li, C.; Krotkov, N.A.; Jongeward, A.R.; Li, Z.; Stehr, J.W.; Hains, J.C.; Dickerson, R.R. Response of SO2 and Particulate Air Pollution to Local and Regional Emission Controls: A Case Study in Maryland. Earth’s Future 2016, 4, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallik, C.; Ghosh, D.; Ghosh, D.; Sarkar, U.; Lal, S.; Venkataramani, S. Variability of SO2, CO, and Light Hydrocarbons over a Megacity in Eastern India: Effects of Emissions and Transport. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 8692–8706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, R.; Han, C.; Yang, Y. Evaluation of the Spatial and Temporal Variations of Condensation and Desublimation over the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau Based on Penman Model Using Hourly ERA5-Land and ERA5 Reanalysis Datasets. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, B.; Xie, Y.; Yao, C.; Liu, B.; Liu, B. Evaluating Rainfall Erosivity on the Tibetan Plateau by Integrating High Spatiotemporal Resolution Gridded Precipitation and Gauge Data. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 947, 174334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, J. Multi-Scale Assessment of ERA5 Hourly Pressure-Level Data on a Global Scale with in-Situ Observations. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2025, 156, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, M.; Dos Santos, G.B.; Muller Vieira, B. Multiple Linear Regression Analysis (MLR) Applied for Modeling a New WQI Equation for Monitoring the Water Quality of Mirim Lagoon, in the State of Rio Grande Do Sul—Brazil. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, S.R.; Jahani, A.; Kalantary, S.; Moeinaddini, M.; Khorasani, N. The Evaluation on Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) and Multiple Linear Regressions (MLR) Models for Predicting SO2 Concentration. Urban Clim. 2021, 37, 100837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, L.; Luo, R. Spatiotemporal Variations of PM2.5 and PM10 Concentrations between 31 Chinese Cities and Their Relationships with SO2, NO2, CO and O3. Particuology 2015, 20, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhu, J.; Liao, H.; Yang, Y.; Yue, X. Meteorological Influences on PM2.5 and O3 Trends and Associated Health Burden since China’s Clean Air Actions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 744, 140837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Liao, H.; Wang, Y.; Qian, J. Co-Occurrence of Ozone and PM2.5 Pollution in Urban/Non-Urban Areas in Eastern China from 2013 to 2020: Roles of Meteorology and Anthropogenic Emissions. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbululo, Y.; Qin, J.; Hong, J.; Yuan, Z. Characteristics of Atmospheric Boundary Layer Structure during PM2.5 and Ozone Pollution Events in Wuhan, China. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, Q.; Hong, Y.; Tan, H.; Liu, L.; Wang, C.; Zhu, J.; Chan, P.; Chen, C. The Modulation of Meteorological Parameters on Surface PM2.5 and O3 Concentrations in Guangzhou, China. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2021, 21, 200084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 3095-2012; Ambient Air Quality Standards. Ministry of Environmental Protection, General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of China: Beijing, China; China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Yan, Y.; Ren, P.; Meng, Q. Quantitative Evaluation of the Synergistic Effects of Multiple Meteorological Parameters on Air Pollutants Based on Generalized Additive Models. Urban Clim. 2024, 55, 101965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, X. An Analysis of the Impacts of Meteorological Factors on Ozone Concentration Using Generalized Additive Model in Tianjin, China. J. Atmos. Sol. -Terr. Phys. 2025, 277, 106669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Cui, K.; Sheu, H.-L.; Wang, L.-C.; Liu, X. Effects of Precipitation on the Air Quality Index, PM2.5 Levels and on the Dry Deposition of PCDD/Fs in the Ambient Air. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2023, 23, 220417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Tan, J.; Li, M. Concentration Prediction and Spatial Origin Analysis of Criteria Air Pollutants in Shanghai. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 327, 121535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, D.; Lang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, X. Process Analysis of the Impacts of Ship Emissions on PM2.5 and O3 in the Yangtze River Delta, China. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 147, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, O.E.; Fiore, A.M.; Massman, W.J.; Baublitz, C.B.; Coyle, M.; Emberson, L.; Fares, S.; Farmer, D.K.; Gentine, P.; Gerosa, G.; et al. Dry Deposition of Ozone Over Land: Processes, Measurement, and Modeling. Rev. Geophys. 2020, 58, e2019RG000670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, G.; Gong, G.; Gan, T.Y.; Chen, D.; Liu, J. Moisture Sources and Pathways of Annual Maximum Precipitation in the Lancang-Mekong River Basin. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2023GL107622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esther Kim, J.-E.; Yoo, C. Mechanisms of Synoptic Circulation Patterns Influencing Winter/Spring PM2.5 Concentrations in South Korea. Atmos. Environ. 2025, 343, 121016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.; Sun, W.; You, X.; Liao, C.; Zhang, B.; Wang, M.; Zhang, H. Transmission Pathways and Potential Source Regions for Atmospheric Fine Particulate Matter and Ozone in Urumqi. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 159, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakriti; Siddiqui, A.; Kannemadugu, H.B.S.; Khan, A.; Amaripadath, D.; Kumar, P.; Chauhan, P.; Singh, R.P. Deciphering Seasonal Variability and Source Dynamics of Urban Pollutants Over Delhi Under Surface Meteorological Influence Using Ground-Based and Trajectory Modeling Techniques. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025, 9, 1447–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Kong, F.; Nie, L.; Gao, W.; Zhao, N.; Lang, J. Ozone Pollution in the Plate and Logistics Capital of China: Insight into the Formation, Source Apportionment, and Regional Transport. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 313, 120144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-C.; Lim, Y.-J.; Han, J.-S. Characterization of Secondary Aerosol Formation via HONO and HNO3 Reactions and Source Apportionment in Daejeon and Iksan, Republic of Korea. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Luo, H.; Yuan, Z.; Xu, D.; Du, Y.; Zhang, S.; Hao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Identification of Close Relationship between Atmospheric Oxidation and Ozone Formation Regimes in a Photochemically Active Region. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 102, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Xing, C.; Hong, Q.; Liu, C.; Ji, X.; Liu, T.; Lin, J.; Lu, C.; Tan, W.; Li, Q.; et al. Diagnosis of Ozone Formation Sensitivities in Different Height Layers via MAX-DOAS Observations in Guangzhou. JGR Atmos. 2022, 127, e2022JD036803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Chen, H.; Wu, J.; Wang, W.; Zheng, J.; Chen, D.; Li, J.; Tang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, L.; et al. Characteristics of the Source Apportionment of Primary and Secondary Inorganic PM2.5 in the Pearl River Delta Region during 2015 by Numerical Modeling. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 267, 115418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, S.; Zhang, L.; Liu, C.; Lu, S.; Pan, W.; Zhang, Y. Multi-Scale Analysis of the Impacts of Meteorology and Emissions on PM2.5 and O3 Trends at Various Regions in China from 2013 to 2020 2. Key Weather Elements and Emissions. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 824, 153847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, K.; Wang, X.; Cai, X.; Yan, Y.; Jin, X.; Vrekoussis, M.; Kanakidou, M.; Brasseur, G.P.; Shen, J.; Xiao, T.; et al. Rethinking the Role of Transport and Photochemistry in Regional Ozone Pollution: Insights from Ozone Concentration and Mass Budgets. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 7653–7671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, L. Nonlinear Relationship between Air Pollution and Precursor Emissions in Qingdao, Eastern China. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2025, 19, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Winiwarter, W.; Van Grinsven, H.J.M.; Wang, X.; Li, K.; Pan, D.; Liu, Z.; Gu, B. Ambitious Nitrogen Abatement Is Required to Mitigate Future Global PM2.5 Air Pollution toward the World Health Organization Targets. One Earth 2024, 7, 1600–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G. Revealing the Nonlinear Responses of PM2.5 and O3 to VOC and NOx Emissions from Various Sources in Shandong, China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 489, 137655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.-S.; Hung, C.-M.; Hung, K.-N.; Yang, Z.-M.; Cheng, P.-H.; Soong, K.-Y. Route-Based Chemical Significance and Source Origin of Marine PM2.5 at Three Remote Islands in East Asia: Spatiotemporal Variation and Long-Range Transport. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2023, 14, 101762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Xiao, S.; Cai, R.-T.; Du, W.-T.; Mi, N.; Liu, S.-X.; Liu, J.-B. Characterization and Sources of Winter PM2.5 Organic and Elemental Carbon in the High-Altitude Region of Qinling Mountains. Environ. Earth Sci 2025, 84, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yang, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, L.; Dang, R.; Xue, D.; Li, B.; Tang, J.; Leung, L.R.; Liao, H. North China Plain as a Hot Spot of Ozone Pollution Exacerbated by Extreme High Temperatures. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022, 22, 4705–4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Russo, A.; Du, H.; Xiang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, C. Impact of Meteorological Conditions at Multiple Scales on Ozone Concentration in the Yangtze River Delta. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 62991–63007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Yao, S. Drivers of Fine Particulate Matter Improvement and Ozone Increase in Shandong, China from 2013 to 2017. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2025, 102724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yan, Y.; Kong, S.; Bai, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Gu, X.; Song, A.; Tong, Z. Effectiveness of Inter-Regional Collaborative Emission Reduction for Ozone Mitigation under Local-Dominated and Transport-Affected Synoptic Patterns. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 51774–51789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nautiyal, S.N.; Joshi, V.; Gautam, A.S.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, S.; Singh, K.; Gautam, S. Characterization and Source Apportionment of PM2.5 and PM10 in a Mountain Valley: Seasonal Variations, Morphology, and Elemental Composition. J. Atmos. Chem. 2025, 82, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, M.; Jayaratne, R.; Thai, P.; Christensen, B.; Zing, I.; Liu, X.; Morawska, L. Evaluating the Applicability of the Ratio of PM2.5 and Carbon Monoxide as Source Signatures. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 306, 119278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.-W.; Chen, T.-S.; Guan, C.-F.; Yin, M.-J.; Xiao, H.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, H.-Y. Trans-Regional NO2 Drives Winter Nitrate Source and Formation Disparities between the North China Plain and the Yangtze River Delta. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 499, 140241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, L.; Wang, S.; Henze, D.K.; Fu, T.-M.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X. Unraveling the Complexities of Ozone and PM2.5 Pollution in the Pearl River Delta Region: Impacts of Precursors Emissions and Meteorological Factors, and Effective Mitigation Strategies. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2025, 16, 102368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Z.; Kang, S.; Kawamura, K.; Liu, B.; Wan, X.; Wang, Z.; Gao, S.; Fu, P. Carbonaceous Aerosols on the South Edge of the Tibetan Plateau: Concentrations, Seasonality and Sources. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 1573–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Du, P.; Samat, A.; Xia, J.; Che, M.; Xue, Z. Spatiotemporal Pattern of PM2.5 Concentrations in Mainland China and Analysis of Its Influencing Factors Using Geographically Weighted Regression. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; An, Y.; Tan, Y.; Li, K.; Xu, J.; Hou, S. Highly Time-Resolved Chemical Characteristics and Aging Process of Submicron Aerosols over the Central Himalayas. EGUsphere 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Tian, P.; Zhao, Y.; Song, X.; Liang, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Guan, X.; Cao, X.; Ren, Y.; et al. Impact of Aerosol-Boundary Layer Interactions on PM2.5 Pollution during Cold Air Pool Events in a Semi-Arid Urban Basin. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 922, 171225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filonchyk, M.; Yan, H. Urban Air Pollution Monitoring by Ground-Based Stations and Satellite Data; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-3-319-78044-3. [Google Scholar]

- Filonchyk, M.; Yan, H. The Characteristics of Air Pollutants during Different Seasons in the Urban Area of Lanzhou, Northwest China. Environ. Earth Sci 2018, 77, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; He, J.; Li, J.; Ren, H.; Zhang, L.; Gong, S.; Wang, H.; Che, H.; Zhang, X. Identifying Spatio-Temporal Climatic Characteristics and Events of the South-Asian Aerosol Pollution Transport to the Tibetan Plateau. Atmos. Res. 2023, 286, 106683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Mukherjee, S.; Choudhary, N.; Ghosh, A.; Chatterjee, A.; Mandal, T.K.; Sharma, S.K.; Kotnala, R.K. Seasonal Transport Pathway and Sources of Carbonaceous Aerosols at an Urban Site of Eastern Himalaya. Aerosol Sci. Eng. 2021, 5, 318–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Zigler, C.; Selin, N.E. Statistical and Machine Learning Methods for Evaluating Trends in Air Quality under Changing Meteorological Conditions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022, 22, 10551–10566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhao, T.; Yang, Y.; Zong, L.; Kumar, K.R.; Wang, H.; Meng, K.; Zhang, L.; Lu, S.; Xin, Y. Seasonal Changes in the Recent Decline of Combined High PM2.5 and O3 Pollution and Associated Chemical and Meteorological Drivers in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhao, W.; Ying, N.; Nie, L.; Shao, X.; Zhang, W.; Dang, H.; Zhang, X. Revealing the Driving Effect of Emissions and Meteorology on PM2.5 and O3 Trends through a New Algorithmic Model. Chemosphere 2022, 295, 133756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, X.; Forster, G.L.; Nowack, P. A Machine Learning Approach to Quantify Meteorological Drivers of Ozone Pollution in China from 2015 to 2019. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022, 22, 8385–8402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y. Spatiotemporal Patterns and Regional Transport Contributions of Air Pollutants in Wuxi City. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorkin, A.A.; Voskresenskaya, E.N.; Zhuravskiy, V.Y. Simulation of Pollutants Trajectory in the Black Sea Region Atmosphere with Different Spatial Resolution. Preprints 2023, 2023111695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzaid, A.S.; Anil, I.; Aga, O. Simulation and Assessment of Episodic Dust Storms in Eastern Saudi Arabia Using HYSPLIT Trajectory Model and Satellite Observations. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Yuan, W. Evaluation of ERA5 Precipitation over the Eastern Periphery of the Tibetan Plateau from the Perspective of Regional Rainfall Events. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 41, 2625–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Yi, S.; Leng, C.; Xia, D.; Li, M.; Zhong, Z.; Ye, J. The Evaluation of IMERG and ERA5-Land Daily Precipitation over China with Considering the Influence of Gauge Data Bias. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qin, X.; Liu, Y.; Jin, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, J. Evaluation of Long-Term and High-Resolution Gridded Precipitation and Temperature Products in the Qilian Mountains, Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 906821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Xin, X.; Zhang, H.; Yu, S.; Li, L.; Ye, Z.; Liu, Q.; Cai, H. Evaluation of Six Data Products of Surface Downward Shortwave Radiation in Tibetan Plateau Region. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, P.; Chen, X.; Zhu, L. Applicability Assessment of ERA5 Surface Wind Speed Data Across Different Landforms in China. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Zhang, X.; Xiu, A.; Tong, Q.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, S.; Yang, G.; Zhang, M.; Xie, S. Intercomparison of Multiple Two-Way Coupled Meteorology and Air Quality Models (WRF v4.1.1–CMAQ v5.3.1, WRF–Chem v4.1.1, and WRF v3.7.1–CHIMERE V2020r1) in Eastern China. Geosci. Model Dev. 2024, 17, 2471–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, F.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, T.; Qi, M.; Song, H. Contribution of Dust Emissions from Farmland to Particulate Matter Concentrations in North China Plain: Integration of WRF-Chem and WEPS Model. Environ. Int. 2025, 195, 109191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Chen, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, W.; Guo, W.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, Y.; She, J. Effects of Chemical Boundary Conditions on Simulated O3 Concentrations in China and Their Chemical Mechanisms. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Type | Variable Name | Resolution | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air quality | PM2.5, PM10, SO2, NO2, CO, O3 | Hourly/Daily (O3: MDA8) | CNEMC http://www.cnemc.cn/ |

| Meteorology | rh, blh, ssrd, t2m, tp, wind | Hourly/Daily | ERA5 https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/ |

| Meteorological driver | GDAS1 fields | 6-hourly | GDAS1 (NCEP) https://www.ready.noaa.gov/gdas1.php (accessed on 1 July 2025) |

| City | Haibei | Huangna | Hainan | Guoluo | Yushu | Haixi | Xining | Haidong |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site code | 2671A | 2672A | 2673A | 2674A | 2675A | 2676A | 3055A | 3129A |

| Elev. (m) | 3072 | 2471 | 2818 | 3718 | 3689 | 2942 | 2204 | 2072 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, X.; Niu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L. Identification of Local and Transboundary Sources and Mechanisms of PM2.5 and O3 Pollution on the Tibetan Plateau: Implications for Sustainable Air Quality Governance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10853. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310853

Li Y, He Y, Wang Y, Li G, Zhang X, Niu H, Zhang Y, Wang L. Identification of Local and Transboundary Sources and Mechanisms of PM2.5 and O3 Pollution on the Tibetan Plateau: Implications for Sustainable Air Quality Governance. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10853. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310853

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yue, Yuejun He, Yumeng Wang, Guangying Li, Xuan Zhang, Hongjie Niu, Yuanxun Zhang, and Lijing Wang. 2025. "Identification of Local and Transboundary Sources and Mechanisms of PM2.5 and O3 Pollution on the Tibetan Plateau: Implications for Sustainable Air Quality Governance" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10853. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310853

APA StyleLi, Y., He, Y., Wang, Y., Li, G., Zhang, X., Niu, H., Zhang, Y., & Wang, L. (2025). Identification of Local and Transboundary Sources and Mechanisms of PM2.5 and O3 Pollution on the Tibetan Plateau: Implications for Sustainable Air Quality Governance. Sustainability, 17(23), 10853. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310853