Education Expenditure and Sustainable Human Capital Formation: Evidence from OECD Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

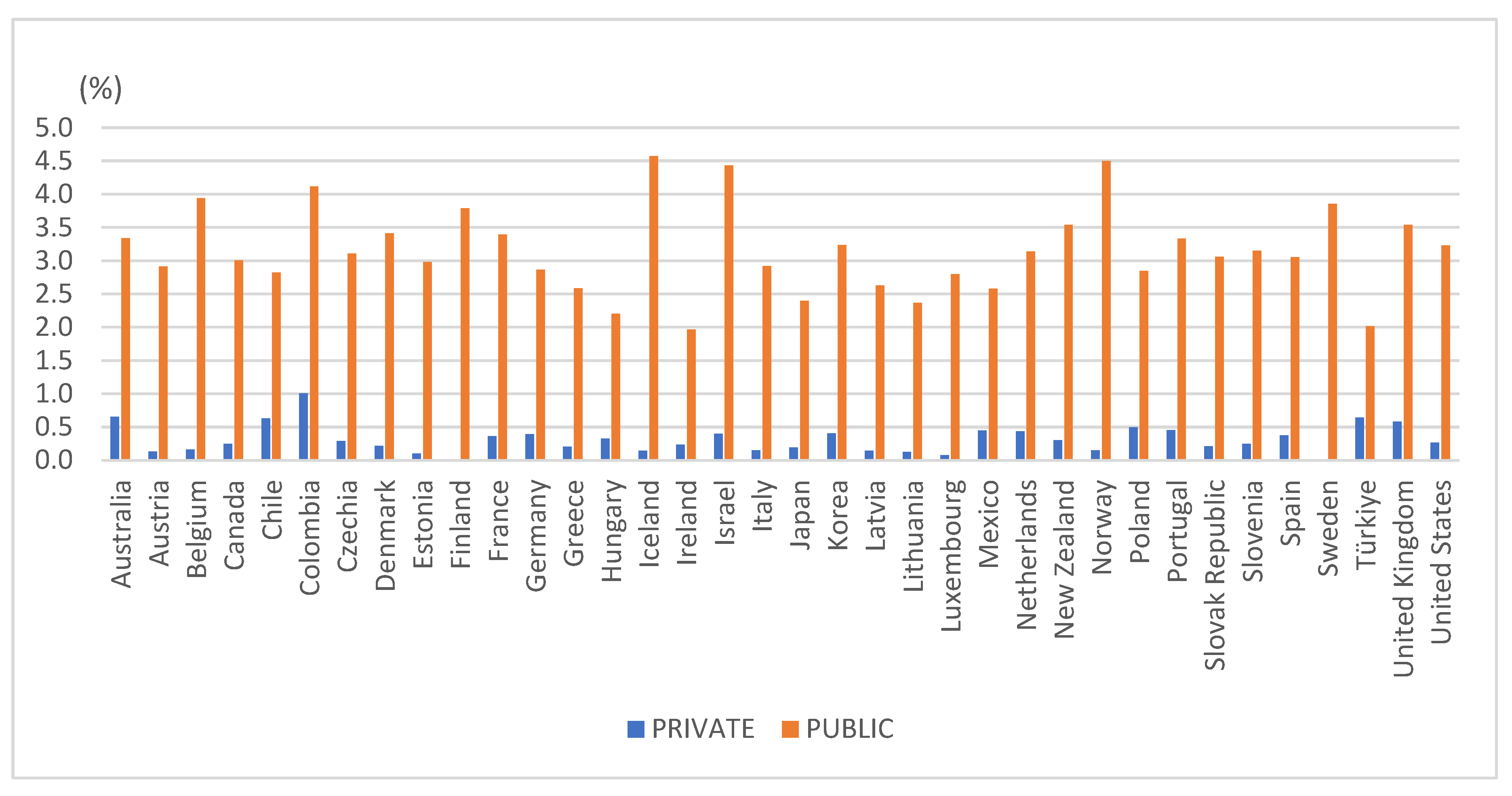

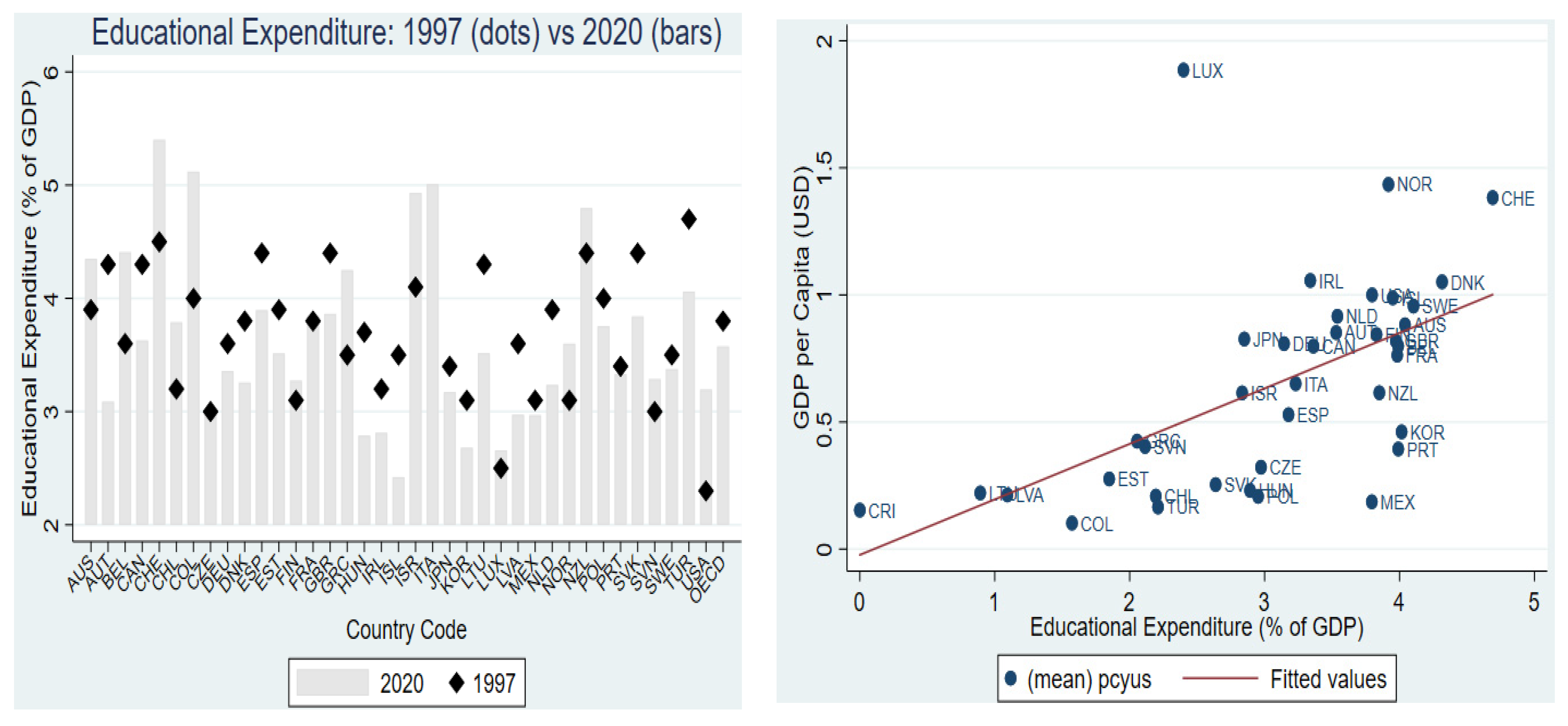

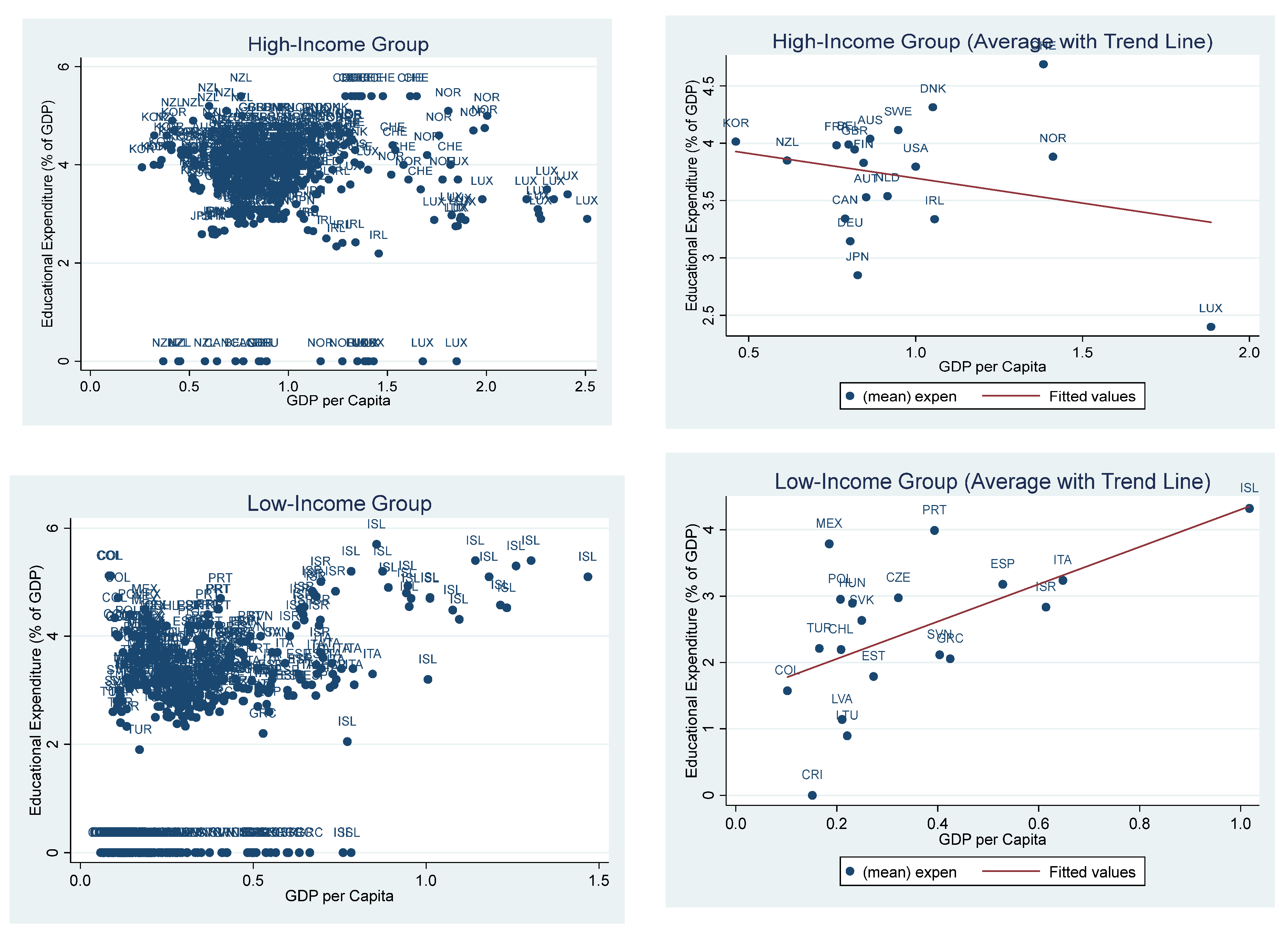

3.1. Data

3.2. Method

3.3. The Empirical Model

- Baseline Model

- B.

- Interaction Model

4. Empirical Result

4.1. Fixed-Effects Model

4.2. MMQR Model

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary of Analysis

5.2. Policy Recommendations

6. Limitations and Prospects

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| All Countries | High-Income Countries | Low-Income Countries | |

|---|---|---|---|

| lnpergdp | 0.261 *** (0.07) | 0.142 (1.53) | 4.401 *** (2.80) |

| −0.927 *** (0.34) | −0.457 * (1.71) | −6.194 *** (1.53) | |

| inequ | −3.240 * (1.79) | −2.039 *** (1.76) | 5.149 * (2.18) |

| ferti | −0.635 *** (0.35) | 0.257 (1.69) | −0.011 * (2.19) |

| eduqulity | 0.120 (0.01) | 0.051(0.07) | 0.741(2.35) |

| pop | 0.002 ** (0.00) | 0.000 (0.00) | 0.019 ** (0.02) |

| C | 6.076 *** (2.25) | 6.593 *** (2.13) | −6.223 ** (4.03) |

| 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.64 | |

| Obs. | 798 | 399 | 399 |

References

- Hwang, J.-Y. Income distribution and tertiary education expenditures: Focusing on OECD countries. Korean J. Public Financ. 2006, 20, 105–125. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2024: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank; UNESCO. Education Finance Watch 2024; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Education Financing. OECD Policy Issues. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/policy-issues/education-financing.html (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Alesina, A.; Ardagna, S. Large changes in fiscal policy: Taxes versus spending. In Tax Policy and the Economy; Brown, J.R., Ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010; Volume 24, pp. 35–68. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, D.B. The economics and politics of cost sharing in higher education: Comparative perspectives. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2004, 23, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, D.; Canning, D. Global demographic change: Dimensions and economic significance. In The Global Demographic Transition; Clark, T., Ed.; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Castles, F.G. Explaining public education expenditure in OECD nations. Eur. J. Political Res. 1989, 17, 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A.; Rodrik, D. Distributive politics and economic growth. Q. J. Econ. 1994, 109, 465–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterly, W.; Rebelo, S. Fiscal policy and economic growth: An empirical investigation. J. Monet. Econ. 1993, 32, 417–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylwester, K. Income inequality, education expenditures, and growth. J. Dev. Econ. 2000, 63, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perotti, R. Growth, income distribution, and democracy: What the data say. J. Econ. Growth 1996, 1, 149–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gregorio, J.; Lee, J.W. Education and income inequality: New evidence from cross-country data. Rev. Income Wealth 2002, 48, 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemmell, N.; Kneller, R.; Sanz, I. Does the composition of government expenditure matter for long-run GDP levels? Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2016, 78, 522–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldacci, E.; Clements, B.; Gupta, S.; Cui, Q. Social spending, human capital, and growth in developing countries: Implications for achieving the MDGs. World Dev. 2008, 36, 1317–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulos, K.; Malley, J.; Philippopoulos, A. Macroeconomic effects of public education expenditure. CESifo Econ. Stud. 2008, 54, 471–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulos, K.; Malley, J.; Philippopoulos, A. The welfare implications of resource allocation policies under uncertainty: The case of public education spending. J. Macroecon. 2011, 33, 176–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofimov, I.D. The optimum size of public education spending: The evidence from the developed, developing and transition economies. J. Econ. Res. 2021, 26, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artige, L.; Cavenaile, L. Public education expenditures, growth and income inequality. J. Econ. Theory 2023, 209, 105622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Education Public Expenditure Review Guidelines; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/27264 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Busemeyer, M.R. Skills and Inequality: Partisan Politics and the Political Economy of Education Reforms in Western Welfare States; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, J.S. The impact of private education expenses on low birth rates. Korea Econ. Assoc. 2024. Available online: https://www.fki.or.kr/fileOut/report/%EC%82%AC%EA%B5%90%EC%9C%A1%EB%B9%84%EA%B0%80%20%EC%A0%80%EC%B6%9C%EC%82%B0%EC%97%90%20%EB%AF%B8%EC%B9%98%EB%8A%94%20%EC%98%81%ED%96%A5.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Park, J.B. An empirical study on the effect and the contribute rate of housing price and private education expense on the total fertility rate. Korean Soc. Secur. Stud. 2021, 37, 65–92. [Google Scholar]

- Schady, F.C.; Behrman, J.A. Declining fertility and economic well-being: Do education and health ride to the rescue? IZA J. Labor Econ. 2015, 4, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bénabou, R. Inequality and growth. NBER Macroecon. Annu. 1996, 11, 11–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, S.; Evans, W. Income Inequality, the Median Voter, and the Support for Public Education; NBER Working Paper No. 16097; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Fu, Q. Effects of common prosperity on China’s education expenditure. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 91, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenker, R.; Bassett, G., Jr. Regression quantiles. Econometrica 1978, 46, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, J.A.F.; Santos Silva, J.M.C. Quantiles via moments. J. Econ. 2019, 213, 145–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, W.H. The effect of educational expenditure on income distribution in OECD countries. In Proceedings of the Korean Association of Public Finance Conference, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 8–9 August 2019; Korean Association of Public Finance: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2019; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig, J. What drives health care expenditure?—Baumol’s model of “unbalanced growth” revisited. J. Health Econ. 2008, 27, 603–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E. Education inequality and income inequality: Inverted-U relationship analysis using panel data. Korean J. Policy Stud. 2011, 28, 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tournemaine, F.; Tsoukis, C. Public expenditures, growth, and distribution in a mixed regime of education with a status motive. J. Public Econ. Theory 2015, 17, 673–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filmer, D.; Pritchett, L. The effect of household wealth on educational attainment: Evidence from 35 countries. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1999, 25, 85–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambor, T.; Clark, W.R.; Golder, M. Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Polit. Anal. 2006, 14, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psacharopoulos, G.; Patrinos, H.A. Returns to investment in education: A decennial review of the global literature. Educ. Econ. 2018, 26, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelló-Climent, A.; Hidalgo-Cabrillana, A. The role of educational quality and quantity in the process of economic development. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2012, 31, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, B.; Filmer, D.; Patrinos, H.A. Making Schools Work: New Evidence on Accountability Reforms; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Education Expenditure (Eduexp) | Total expenditure on educational institutions as a percentage of GDP (2018) | OECD DATA |

| Income Level (pergdp) | Gross domestic product, current prices (U.S. dollars), Population, CPI (Inflation, average consumer prices) | WEO |

| Income Inequality (inequ) | Gini Coefficient | OECD DATA |

| Fertility Rate (ferti) | Total Fertility | OECD DATA |

| Population Density (pop) | Population density (Persons per square kilometer) | OECD DATA |

| Variables | Max | Min | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eduexp | 5.7 | 1.91 | 3.097 | 1.489 |

| lnpergdp | 0.919 | 0.058 | 0.689 | 0.777 |

| inequ | 0.497 | 0.217 | 0.31 | 0.079 |

| ferti | 3.11 | 0.81 | 1.679 | 0.380 |

| pop | 5.806 | −1.309 | 2.525 | 1.513 |

| Classification (Economic Size) | Countries (Abbreviation) |

|---|---|

| High-Income Countries | USA, GBR, CAN, IRL, AUS, NZL, JPN, DEU, FRA, CHE, SWE, DNK, NOR, FIN, AUT, BEL, NLD, KOR, LUX |

| Low-Income Countries | ITA, GRC, PRT, ESP, POL, HUN, SVK, SVN, CZE, ISR, ISL, MEX, CHL, EST, TUR, COL, CRI, LVA, LTU |

| All Countries | High-Income Countries | Low-Income Countries | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.396 *** (0.17) | 0.241 (0.20) | 4.571 *** (1.53) | |

| −0.690 *** (0.21) | −0.515 (0.18) | −6.773 *** (2.92) | |

| inequ | −3.240 * (1.79) | −5.432 *** (1.49) | 3.149 * (3.02) |

| ferti | −0.835 *** (0.22) | 0.244 (0.21) | −0.221 * (0.45) |

| lnpop | 0.003 * (0.001) | 0.002 (0.00) | 0.046 ** (0.14) |

| C | 2.205 *** (1.00) | 6.891 *** (1.18) | −3.607 ** (2.32) |

| 0.41 | 0.32 | 0.31 | |

| Obs. | 912 | 456 | 456 |

| All Countries | High-Income Countries | Low-Income Countries | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnpergdp | 2.674 *** (0.51) | 5.497 *** (0.55) | 5.014 *** (0.46) | 1.384 (1.54) | 3.80 1 ** (1.91) | 3.978 *** (1.02) | 4.924 *** (2.54) | 4.687 * (2.64) | 4.515 *** (2.95) |

| −1.484 *** (0.15) | −1.566 *** (0.14) | −1.464 *** (0.15) | −0.603 ** (0.26) | −0.596 ** (0.25) | −1.451 *** (0.14) | −5.624 *** (2.81) | −5.487 *** (2.99) | 5.376 *** (2.65) | |

| Inequ | 0.411 * (0.53) | 1.574 (0.51) | 1.241 * (0.52) | −5.210 *** (1.00) | 1.247 (2.14) | 1.090 * (0.47) | −1.947 ** (0.52) | −2.341 ** (1.00) | −2.320 ** (1.10) |

| Ferti | −0.441 * (0.20) | −0.021 (0.11) | −0.424 * (0.20) | 0.788 (0.24) | 0.724 *** (0.15) | −0.756 ** (0.18) | −0.987 *** (0.29) | −0.548 *** (0.45) | −1.048 *** (0.32) |

| pergdp × ferti | 0.855 ** (0.33) | 0.814 ** (0.37) | −0.450 (0.54) | 0.807 * (0.22) | 2.054 ** (0.78) | 1.879 ** (0.88) | |||

| pergdp × inequ | −6.245 *** (2.00) | −6.740 *** (2.01) | −7.241 * (4.27) | −7.040 *** (2.13) | 5.917 (5.27) | 4.400 (5.03) | |||

| Lnpop | 0.001 ** (0.00) | 0.003 *** (0.00) | 0.003 *** (0.00) | 0.000 * (0.00) | 0.002 * (0.00) | 0.003 *** (0.00) | 0.021 *** (0.00) | 0.021 *** (0.00) | 0.023 *** (0.02) |

| C | 2.132 *** (0.24) | 1.541 (0.27) | 2.310 *** (0.32) | 3.475 (1.20) | 1.029 (1.42) | 9.406 *** (2.50) | 2.147 * (1.28) | 2.104 ** (1.64) | 2.614 *** (1.67) |

| 0.31 | 0.38 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.32 | |

| Obs. | 912 | 912 | 912 | 456 | 456 | 456 | 456 | 456 | 456 |

| All Countries | High-Income Countries | Low-Income Countries | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q.10 | Q.25 | Q.50 | Q.75 | Q.90 | Q.10 | Q.25 | Q.50 | Q.75 | Q.90 | Q.10 | Q.25 | Q.50 | Q.75 | Q.90 | |

| lnpergdp | 5.264 *** (1.17) | 7.112 *** (0.35) | 2.924 *** (0.33) | 2.141 *** (0.27) | 1.624 *** (0.30) | 0.998 (2.00) | 0.789 (0.53) | 2.014 *** (0.50) | 3.354 *** (0.14) | 3.954 *** (0.78) | 4.924 (3.37) | 6.001 *** (3.25) | 6.248 *** (2.20) | 9.405 (3.60) | 8.693 ** (3.33) |

| −1.925 ** (0.28) | −1.957 *** (0.20) | −1.624 *** (0.17) | −1.112 *** (0.20) | −1.095 * (0.21) | −0.354 (1.16) | −0.384 (0.20) | −0.705 *** (0.21) | −1.113 *** (0.13) | −1.164 *** (0.21) | −6.651 (5.50) | −7.625 *** (4.28) | −7.320 *** (4.30) | −9.854 (4.85) | −9.004 ** (4.62) | |

| inequ | −1.064 (0.70) | −0.752 (1.50) | −0.324 (1.50) | −0.687 (0.98) | −0.100 (0.92) | −2.241 (2.21) | −3.248 *** (2.31) | −3.756 ** (1.50) | 3.320 (1.60) | 2.754 (1.62) | 1.321 *** (0.43) | 1.357 ** (0.70) | 1.654 (1.10) | 1.762 (1.64) | 1.778 (1.71) |

| ferti | −0.536 (0.35) | −0.120 (0.27) | 0.367 *** (0.34) | 0.435 *** (0.27) | 0.467 *** (0.15) | 1.210 *** (0.19) | 1.124 *** (0.12) | 0.120 *** (0.12) | 0.121 *** (0.15) | 0.119 *** (0.20) | −0.627 ** (0.34) | −0.798 *** (0.31) | −0.627 ** (0.24) | −0.533 ** (0.21) | −0.492 ** (0.21) |

| lnpop | 0.002 ** (0.00) | 0.000 *** (0.00) | 0.001 * (0.00) | 0.001 *** (0.00) | 0.002 *** (0.00) | 0.002 * (0.00) | 0.002 *** (0.00) | 0.000 (0.00) | 0.000 (0.00) | 0.000 (0.00) | 0.022 *** (0.00) | 0.025 *** (0.00) | 0.010 *** (0.00) | 0.009 *** (0.00) | 0.009 *** (0.00) |

| c | 1.354 * (0.68) | 1.657 (0.72) | 1.546 ** (0.71) | 1.924 *** (0.68) | 3.648 *** (0.69) | 4.681 ** (1.62) | 4.038 *** (1.38) | 3.067 *** (0.67) | 2.681 ** (0.52) | 2.689 (0.68) | −3.910 (0.60) | −2.618 ** (0.54) | −1.985 ** (0.61) | 1.761 (1.10) | 1.927 *** (0.95) |

| Obs. | 912 | 912 | 912 | 912 | 912 | 456 | 456 | 456 | 456 | 456 | 456 | 456 | 456 | 456 | 456 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kwon, S.-H. Education Expenditure and Sustainable Human Capital Formation: Evidence from OECD Countries. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10848. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310848

Kwon S-H. Education Expenditure and Sustainable Human Capital Formation: Evidence from OECD Countries. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10848. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310848

Chicago/Turabian StyleKwon, Sun-Hee. 2025. "Education Expenditure and Sustainable Human Capital Formation: Evidence from OECD Countries" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10848. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310848

APA StyleKwon, S.-H. (2025). Education Expenditure and Sustainable Human Capital Formation: Evidence from OECD Countries. Sustainability, 17(23), 10848. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310848