Navigating Environmental Concerns: Assessing the Influence of Renewable Electricity and Eco-Taxation on Environmental Sustainability Using Nonlinear Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.2. Hypothesis Development

2.2.1. The Eco Tax and Environmental Degradation

2.2.2. Renewable Electricity and Environmental Degradation

2.2.3. Relations Between Economic Growth and Environmental Degradation

2.2.4. Relations Between Primary Energy Supply and Environmental Degradation

2.3. Conceptual Insights

3. Methodology

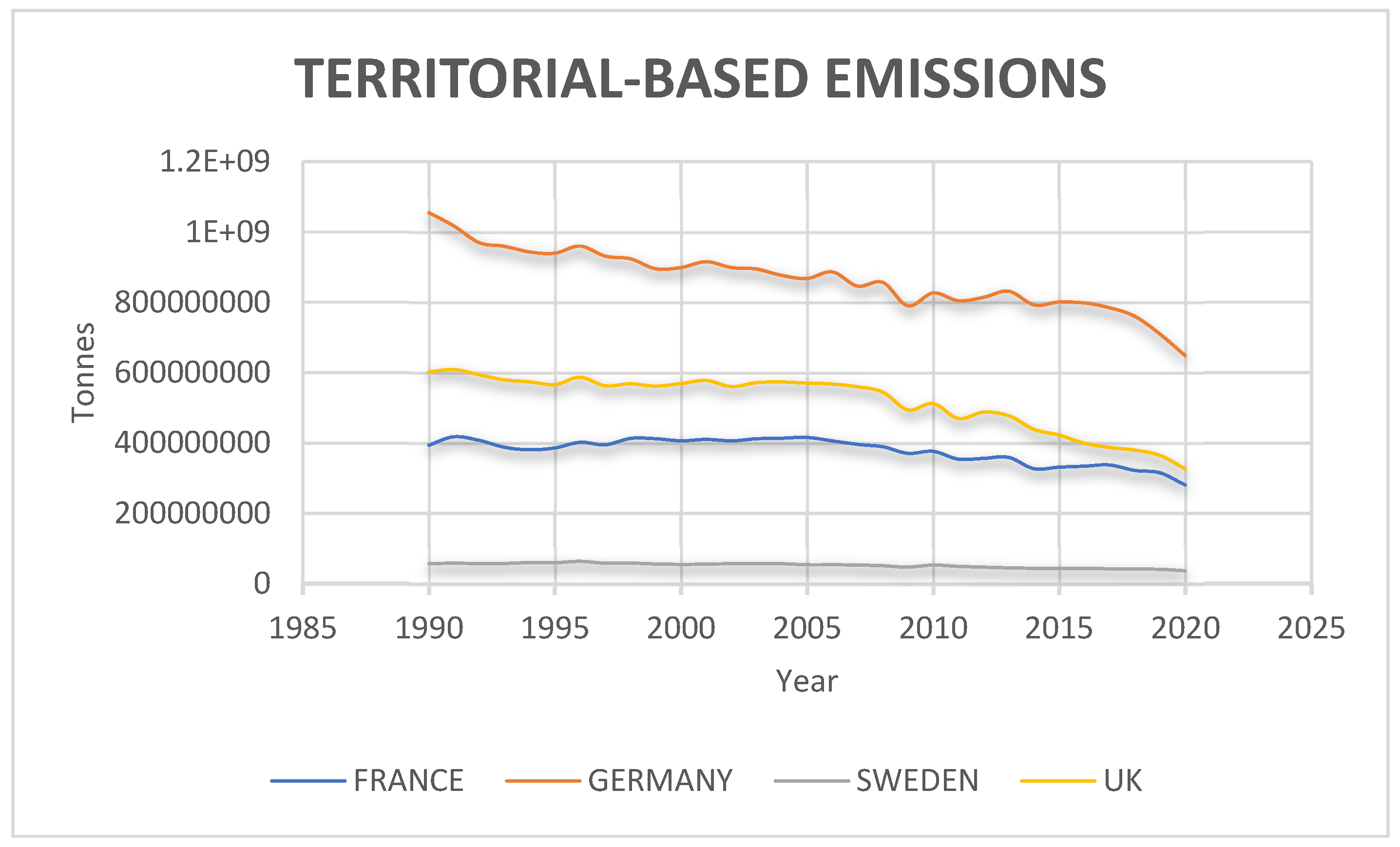

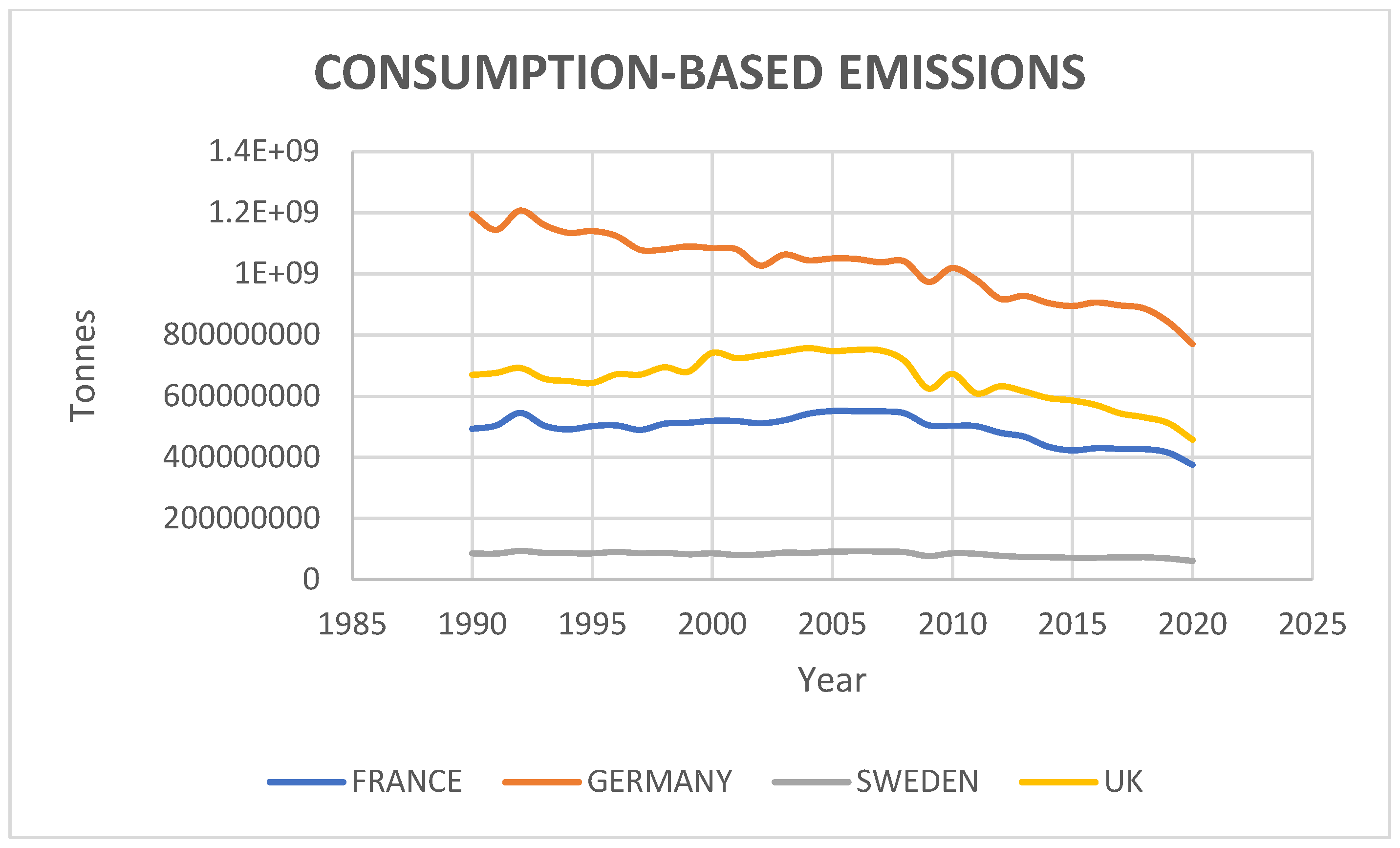

3.1. Data and Source

3.2. Theoretical Motivations

3.3. Estimation Procedure

3.3.1. BDS Tests

3.3.2. ADF Unit Root with Break Point

3.3.3. Fourier Autoregressive Distributive Lag (F-ADL) Cointegration Tests

3.3.4. Fourier Nonlinear ARDL Long-Run Equilibrium Estimation

4. Empirical Outcomes

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. The BDS (Nonlinear) Test

4.3. ADF Unit Root Test with Break Point

4.4. Fourier ADL Co-Integration Analysis

4.5. N—ARDL Bounds and Long Run Test

4.6. Discussion of Findings

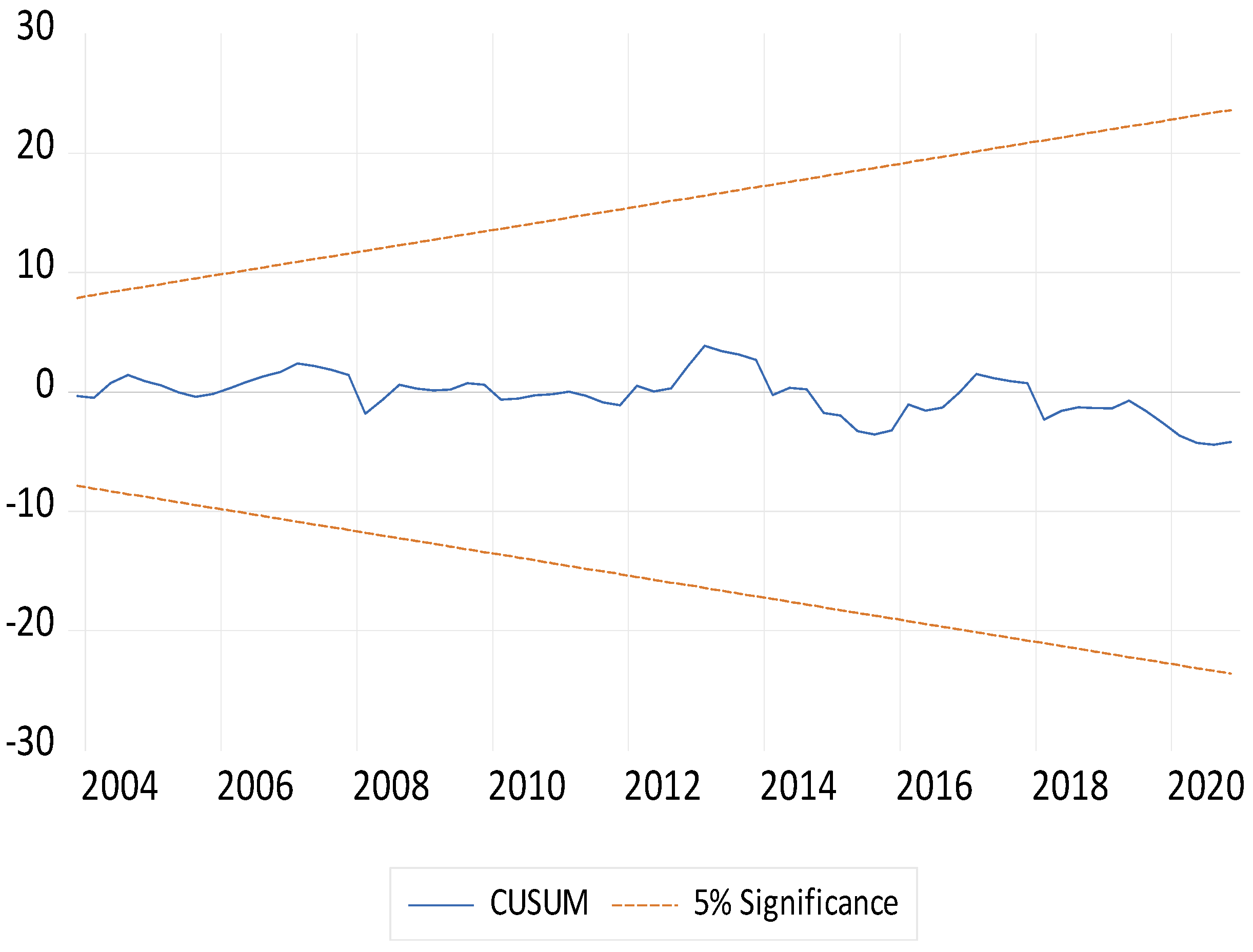

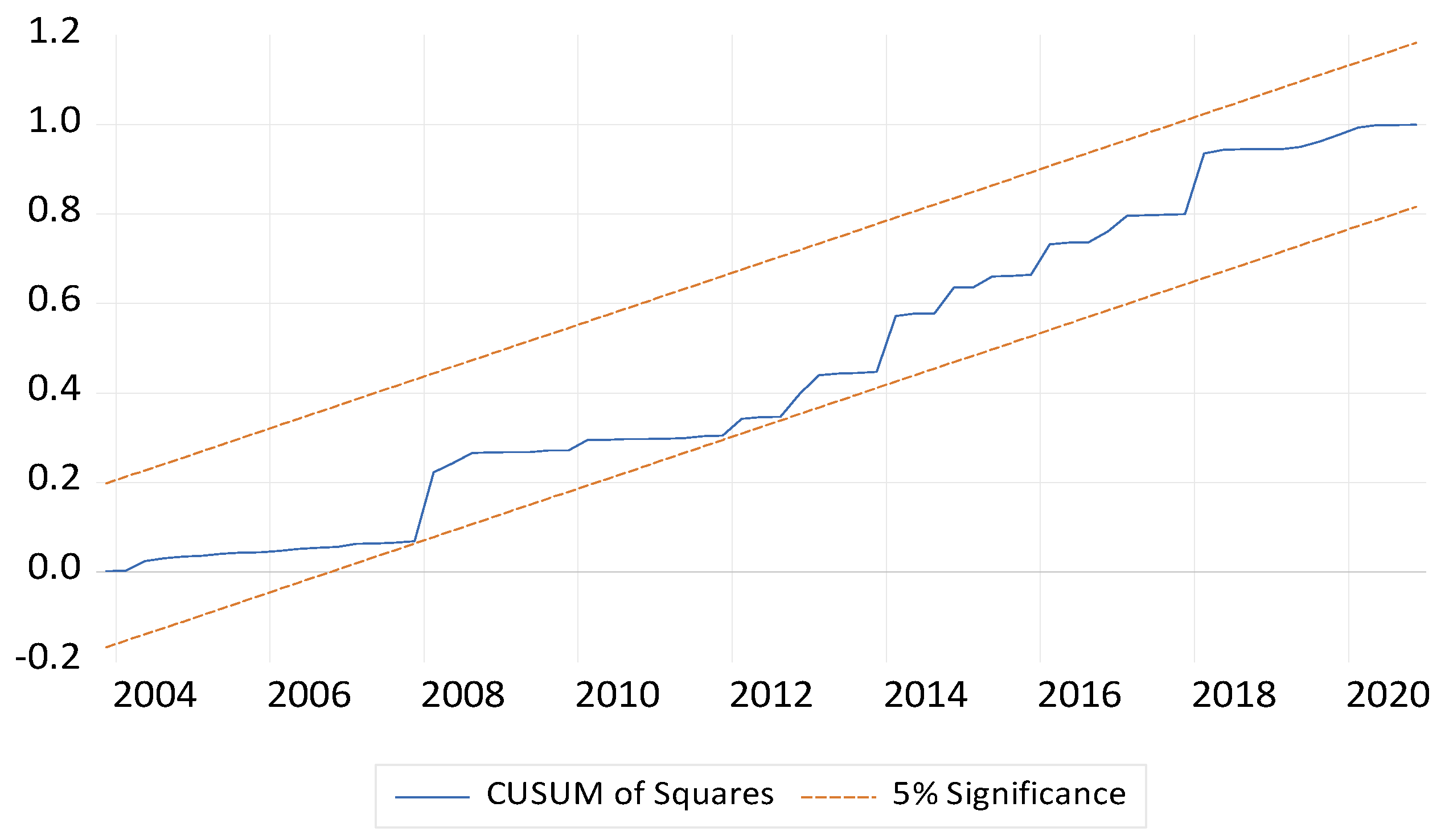

4.7. Model Stability Test

4.8. Residual Diagnostic Tests

4.9. Causality Test

5. Conclusions and Implications of the Study

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Policy Implications

5.3. Limitations of the Study and Future Considerations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alvarado, R.; Toledo, E. Environmental degradation and economic growth: Evidence for a developing country. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2017, 19, 1205–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMorran, R.; Nellor, D. Tax Policy and the Environment: Theory and Practice. 1994. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=883847 (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Lin, B.; Jia, Z. The energy, environmental, and economic impacts of carbon tax rate and taxation industry: A CGE-based study in China. Energy 2018, 159, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briguglio, E. The Impact of Taxation on the Ecological Transition. The Case of the So-Called Plastic Tax. 2025. Available online: https://tesidottorato.depositolegale.it/bitstream/20.500.14242/215192/1/Tesi_The%20impact%20of%20taxation%20on%20the%20ecological%20transition.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Cardenete Flores, M.A.; Lima, M.C.; Sancho, F. Technology Determinants of Carbon Emissions from Demand and Supply Perspectives; BSE, Barcelona School of Economics: Barcelona, Spain, 2024; Available online: https://ddd.uab.cat/record/299347 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Verma, R. Fiscal Control of Pollution; Springer: Singapore, 2021; Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-981-16-3037-8 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Taxing Energy Use 2019: Using Taxes for Climate Action; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nazarkevych, I.; Sych, O. Taxation as a tool of implementation of the EU Green Deal in Ukraine. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2023, 15, 144–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloche, J.P.; Tremblay-Racicot, F. Eco-Fiscal Tools and Municipal Finance: Current Practices and Opportunities. 2025. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1807/145382 (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Our World in Data. 2025. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/production-vs-consumption-co2-emissions?tab=table&country=FRA~SWE~DEU~GBR&tableFilter=selection (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Lin, B.; Jia, Z. Is emission trading scheme an opportunity for renewable energy in China? A perspective of ETS revenue redistributions. Appl. Energy 2020, 263, 114605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, A. Global renewable energy projections. Energy Sources Part B 2009, 4, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielen, D.; Gorini, R.; Wagner, N.; Leme, R.; Gutierrez, L.; Prakash, G.; Asmelash, E.; Janeiro, L.; Gallina, G.; Vale, G.; et al. Global Energy Transformation: A Roadmap to 2050. 2019. Available online: https://www.h2knowledgecentre.com/content/researchpaper1605 (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Moriarty, P.; Honnery, D. Global Renewable Energy Resources and Use in 2050. In Managing Global Warming; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holechek, J.L.; Geli, H.M.E.; Sawalhah, M.N.; Valdez, R. A global assessment: Can renewable energy replace fossil fuels by 2050? Sustainability 2022, 14, 4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyman, R.; Economist, E. Why renewable energy cannot replace fossil fuels by 2050. Friends Sci. Soc. 2016, 1–44. Available online: https://www.ourenergypolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Renewable-energy-cannot-replace-FF_Lyman1.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- de Azevedo, M.C. Recent Developments in the Environmental Debate Before and After the Kyoto Protocol: A Survey; ISAE, Istituto di Studi e Analisi Economica: Roma, Italy, 2002; Available online: https://lipari.istat.it/digibib/Isae%20Documenti%20Lavoro/wpcagiano25.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Grossman, G.M.; Krueger, A.B. Environmental Impacts of a North American Free Trade Agreement. 1991. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3386/w3914 (accessed on 26 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Panayotou, T. Demystifying the environmental Kuznets curve: Turning a black box into a policy tool. Environ. Dev. Econ. 1997, 2, 465–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.F.; Ma, B.; Bashir, M.A.; Radulescu, M.; Shahzad, U. Investigating the role of environmental taxes and regulations for renewable energy consumption: Evidence from developed economies. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraživanja 2022, 35, 1262–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumol, W.J. On Taxation and the Control of Externalities. Am. Econ. Rev. 1972, 62, 307–322. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1803378 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Oates, W.; Baumol, W. The instruments for environmental policy. In Economic Analysis of Environmental Problems; NBER: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1975; pp. 95–132. Available online: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c2834 (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Pigou, A.C. Co-operative Societies and Income Tax. Econ. J. 1920, 30, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M. Factors that affect innovation, deployment and diffusion of energy-efficient technologies–Case studies of Japan and iron/steel industry. In Proceedings of the In-Session Workshop on Mitigation at SBSTA22 (Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice, 22nd Session), Bonn, Germany, 23 May 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, M.S. Carbon taxation and fiscal consolidation: The potential of carbon pricing to reduce Europe’s fiscal deficits. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2019, 94, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulder, L.H. Environmental taxation and the double dividend: A reader’s guide. Int. Tax Public Financ. 1995, 2, 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, G.E. On the economics of a carbon tax for the United States. Brook. Pap. Econ. Act. 2019, 2019, 405–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Siriwardana, M.; McNeill, J. The environmental and economic impact of the carbon tax in Australia. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2013, 54, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Lin, C.; Lin, P. The determinants of pollution levels: Firm-level evidence from Chinese manufacturing. J. Comp. Econ. 2014, 42, 118–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Cheng, J.; Dai, S. Regional eco-innovation in China: An analysis of eco-innovation levels and influencing factors. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 153, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, U.S.; Bhutto, N.A.; Rajput, S.K.O. How do carbon emissions and eco taxation affect the equity market performance: An empirical evidence from 28 OECD economies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 46312–46324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, K.; Tian, Z.; Xue, J. Pollutant emission reduction effect through effluent tax, concentration-based effluent standard, or both. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2016, 14, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, T.; Junankar, S.; Pollitt, H.; Summerton, P. Carbon leakage from unilateral environmental tax reforms in Europe, 1995–2005. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 6281–6292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekins, P.; Speck, S. Environmental Tax Reform (ETR): A Policy for Green Growth; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, B.; Li, X. The effect of carbon tax on per capita CO2 emissions. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 5137–5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, S.; Sauma, E. Does a carbon tax make sense in countries with still a high potential for energy efficiency? Comparison between the reducing-emissions effects of carbon tax and energy efficiency measures in the Chilean case. Energy 2015, 88, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miceikiene, A.; Čiulevičienė, V.; Rauluskeviciene, J.; Štreimikienė, D. Assessment of the effect of environmental taxes on environmental protection. Ekon. Časopis 2018, 66, 286–308. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=685072 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Morley, B. Empirical evidence on the effectiveness of environmental taxes. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2012, 19, 1817–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krarti, M.; Dubey, K.; Howarth, N. Energy productivity analysis framework for buildings: A case study of the GCC region. Energy 2019, 167, 1251–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yufenyuy, M.; Pirgalıoğlu, S.; Yenigün, O. The asymmetric effect of biomass energy use on environmental quality: Empirical evidence from the Congo Basin. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 10241–10274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostakis, I. An empirical investigation of the nexus among renewable energy, financial openness, economic growth, and environmental degradation in selected ASEAN economies. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 354, 120398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, B.; Khalfaoui, R.; Bergougui, B.; Ghosh, S. Unveiling the impact of the digital economy on the interplay of energy transition, environmental transformation, and renewable energy adoption. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2025, 76, 102837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélaïd, F.; Youssef, M. Environmental degradation, renewable and non-renewable electricity consumption, and economic growth: Assessing the evidence from Algeria. Energy Policy 2017, 102, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, V.; Dubey, H.M.; Pandit, M.; Salkuti, S.R. A chaotic Jaya algorithm for environmental economic dispatch incorporating wind and solar power. AIMS Energy 2024, 12, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Lin, B. Green energy dynamics: Analyzing the environmental impacts of renewable, hydro, and nuclear energy consumption in Pakistan. Renew. Energy 2024, 232, 121025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, Y.; Audi, M. Exploring the Nexus of Economic Expansion, Tourist Inflows, and Environmental Sustainability in Europe. 2024. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/id/eprint/121529 (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Hartley, D. Renewables: A Key Component of our Global Energy Future. In Economics and Politics of Energy; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1996; pp. 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhani, S.; Shahbaz, M. What role of renewable and non-renewable electricity consumption and output is needed to initially mitigate CO2 emissions in the MENA region? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 40, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Solarin, S.A.; Mahmood, H.; Arouri, M. Does financial development reduce CO2 emissions in Malaysian economy? A time series analysis. Econ. Model. 2013, 35, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mulali, U.; Ozturk, I.; Lean, H.H. The influence of economic growth, urbanization, trade openness, financial development, and renewable energy on pollution in Europe. Nat. Hazards 2015, 79, 621–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, E.; Turkekul, B. CO2 emissions, real output, energy consumption, trade, urbanization, and financial development: Testing the EKC hypothesis for the USA. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegaki, A.N.; Tugcu, C.T. Rethinking the energy-growth nexus: Proposing an index of sustainable economic welfare for Sub-Saharan Africa. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 17, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serener, B.; Kirikkaleli, D.; Addai, K. Patents on environmental technologies, financial development, and environmental degradation in Sweden: Evidence from novel Fourier-based approaches. Sustainability 2022, 15, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmjoo, A.A.; Sumper, A.; Davarpanah, A. Development of sustainable energy indexes by the utilization of new indicators: A comparative study. Energy Rep. 2019, 5, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, L.S.; Yii, K.J.; Ng, C.F.; Tan, Y.L.; Yiew, T.H. Environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) hypothesis: A bibliometric review of the last three decades. Energy Environ. 2025, 36, 93–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pao, H.T.; Tsai, C.M. CO2 emissions, energy consumption, and economic growth in BRIC countries. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7850–7860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutascu, M. Beyond the EKC: Economic development and environmental degradation in the US. Ecol. Econ. 2025, 232, 108567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrabet, Z.; Alsamara, M. Testing the Kuznets Curve hypothesis for Qatar: A comparison between carbon dioxide and ecological footprint. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 70, 1366–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikayilov, J.I.; Mukhtarov, S.; Mammadov, J.; Azizov, M. Re-evaluating the environmental impacts of tourism: Does EKC exist? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 19389–19402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunjra, A.I.; Bouri, E.; Azam, M.; Azam, R.I.; Dai, J. Economic growth and environmental sustainability in developing economies. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2024, 70, 102341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destek, M.A.; Ulucak, R.; Dogan, E. Analyzing the environmental Kuznets curve for the EU countries: The role of ecological footprint. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 29387–29396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, M.O.; Solarin, S.A.; Yen, Y.Y. The impact of electricity consumption on CO2 emission, carbon footprint, water footprint and ecological footprint: The role of hydropower in an emerging economy. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 219, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solarin, S.A.; Al-Mulali, U.; Ozturk, I. Determinants of pollution and the role of the military sector: Evidence from a maximum likelihood approach with two structural breaks in the USA. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 30949–30961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, J.P.; David, D. Passenger transport and CO2 emissions: What does the French transport survey tell us? Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43, 1015–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuntuyi, B.V.; Lean, H.H. Environmental degradation, economic growth, and energy consumption: The role of education. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 1166–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degirmenci, T.; Aydin, M. The effects of environmental taxes on environmental pollution and unemployment: A panel co-integration analysis on the validity of double dividend hypothesis for selected African countries. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2023, 28, 2231–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Yu, B.; Greenwood-Nimmo, M. Modelling asymmetric cointegration and dynamic multipliers in a nonlinear ARDL framework. In Festschrift in Honor of Peter Schmidt: Econometric Methods and Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 281–314. [Google Scholar]

- Abegaz, B.E. Asymmetric impact of exchange rate on trade balance in Ethiopia: Evidence from a non-linear autoregressive distributed lag model (NARDL) approach. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0311675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka, A.; Ozdeser, H.; Seraj, M. The effect of GDP, renewable energy, and total energy supply on carbon emissions in the EU-27: New evidence from panel GMM. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 28206–28216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saboori, B.; Sulaiman, J.; Mohd, S. Economic growth and CO2 emissions in Malaysia: A cointegration analysis of the environmental Kuznets curve. Energy Policy 2012, 51, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarazkar, M.H.; Dehbidi, N.K.; Ozturk, I.; Al-Mulali, U. The impact of age structure on carbon emission in the Middle East: The panel autoregressive distributed lag approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 33722–33734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Development Indicator. 2025. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- IEA. International Energy Agency (IEA) Data and Statistics. 2024. Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Eurostat. European Commission Database. 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Stokey, N.L. Are There Limits to Growth? Int. Econ. Rev. 1998, 39, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.J. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J. Appl. Econom. 2001, 16, 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, J.P.; Perman, R. Unit Roots and Structural Breaks: A Survey of the Literature; University of Glasgow: Glasgow, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow, J.; Enders, W. Estimating non-linear ARMA models using Fourier coefficients. Int. J. Forecast. 2000, 16, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNown, R.; Sam, C.Y.; Goh, S.K. Bootstrapping the autoregressive distributed lag test for cointegration. Appl. Econ. 2018, 50, 1509–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilanci, V.; Ozgur, O.; Gorus, M.S. The asymmetric effects of foreign direct investment on clean energy consumption in BRICS countries: A recently introduced hidden cointegration test. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 117786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, R.F.; Granger, C.W. Co-integration and error correction: Representation, estimation, and testing. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1987, 55, 251–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, H.Y.; Yamamoto, T. Statistical inference in vector autoregressions with possibly integrated processes. J. Econom. 1995, 66, 225–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Arčabić, V.; Lee, H. Fourier ADL cointegration test to approximate smooth breaks with new evidence from crude oil market. Econ. Model. 2017, 67, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addai, K.; Ozbay, R.D.; Castanho, R.A.; Genc, S.Y.; Couto, G.; Kirikkaleli, D. Energy productivity and environmental degradation in Germany: Evidence from novel Fourier approaches. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Sheng, N. Clarifying the relationship among green investment, clean energy consumption, carbon emissions, and economic growth: A provincial panel analysis of China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 9038–9052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brock, W.A.; Taylor, M.S. The green Solow model. J. Econ. Growth 2010, 15, 127–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.L.; Durbin, J.; Evans, J.M. Techniques for testing the constancy of regression relationships over time. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 1975, 37, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, J.W. The Interaction of A Heated Air Jet with A Deflecting Flow; University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Nazlioglu, S.; Gormus, N.A.; Soytas, U. Oil prices and real estate investment trusts (REITs): Gradual-shift causality and volatility transmission analysis. Energy Econ. 2016, 60, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardizabal, E. France Defines Its Energy Roadmap Until 2035: Offshore Wind and the Transition to a Decarbonized Mix. 2025. Available online: https://strategicenergy.eu/france-defines-its-energy-roadmap-until-2035-offshore-wind-and-the-transition-to-a-decarbonized-mix/ (accessed on 28 June 2025).

| Variables | Abbreviation | Measurement | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon dioxide | LCO2 | Tons per year | [72] |

| Economic growth | LGDP | GDP (constant 2015 USD) Per Capita | [72] |

| Renewable electricity | REE | Mega-Watt-hours | [73] |

| Eco tax | POT | Taxes per year | [74] |

| Energy Used | LTES | Million tons of oil equivalent (Mtoe) | [72] |

| Code | LCO2 | LGDP | REE | POT | LTES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 2.527998 | 12.34732 | 14.50692 | 2.355769 | 3.468990 |

| Median | 2.541802 | 12.36056 | 13.68828 | 2.352500 | 3.471754 |

| Max. | 2.573643 | 12.42159 | 25.76187 | 2.567813 | 3.501445 |

| Min. | 2.388085 | 12.24683 | 9.764687 | 2.135938 | 3.365992 |

| Std. Dev. | 0.040137 | 0.047457 | 3.229695 | 0.131272 | 0.026311 |

| Skewness | −1.036139 | −0.649484 | 1.054900 | 0.037777 | −1.084429 |

| Kurtosis | 3.666659 | 2.438219 | 4.038433 | 1.692861 | 4.724851 |

| Jarque–Bera | 20.53468 | 8.679293 | 23.96159 | 7.428726 | 33.27590 |

| Probability | 0.000035 | 0.013041 | 0.000006 | 0.024371 | 0.000000 |

| Variables | LCO2 | LGDP | REE | POT | LTES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension | BDS Stat. | BDS Stat. | BDS Stat. | BDS Stat. | BDS Stat. |

| 2 | 0.17626 | 0.20726 | 0.16870 | 0.18038 | 0.17211 |

| 3 | 0.28820 | 0.35335 | 0.27344 | 0.30016 | 0.27826 |

| 4 | 0.36466 | 0.45481 | 0.33802 | 0.37553 | 0.34360 |

| 5 | 0.41850 | 0.52481 | 0.37753 | 0.41886 | 0.38873 |

| 6 | 0.45717 | 0.57368 | 0.40486 | 0.44265 | 0.41943 |

| Variable | ADF | Break Point | ADF | Break Point |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT LEVEL | 1st DIFF | |||

| LCO2 | −2.730 | 2018Q4 | −5.261 ** | 1997Q1 |

| LGDP | −3.130 | 2010Q2 | −6.086 *** | 2018Q4 |

| REE | −2.505 | 2011Q2 | −5.888 *** | 1998Q4 |

| POT | −3.978 | 2005Q1 | −5.499 ** | 1998Q1 |

| LTES | −2.851 | 2018Q4 | −5.804 *** | 2017Q1 |

| Model | Test Statistics | Frequency | Min AIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| LCO2 = f(LGDP, REE, POT, LTES) | −5.707 | 0.200 | −8.081 |

| N-ARDL Bounds Results | |

|---|---|

| F-statistics | 7.0760 |

| K | 8 |

| Variable | Coeff | Std. Error | t-Stats | Prob. | Coeff | Std. Error | t-Stats | Prob. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Shock Periods | Negative Shock Periods | ||||||||

| LGDP (+) | −0.484297 | 0.215801 | −2.244184 | 0.0280 | LGDP (−) | −0.234380 | 0.277286 | −0.845262 | 0.4008 |

| LTES (+) | 0.882688 | 0.205284 | 4.299834 | 0.0001 | LTES (−) | 1.341291 | 0.197400 | 6.794798 | 0.0000 |

| REE (+) | −0.005098 | 0.001014 | −5.026512 | 0.0000 | REE (−) | 9.79 × 10−5 | 0.000997 | 0.098216 | 0.9220 |

| POT | −0.043468 | 0.019489 | −2.230330 | 0.0289 | POT | 0.064726 | 0.019684 | 3.288184 | 0.0016 |

| Serial Correlation Approach | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-statistic | 0.0006 | Prob. | 0.979 | |

| Heteroskedasticity Test: Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey | ||||

| F-statistic | 1.28792 | Prob. F(28, 70) | 0.196 | |

| Ramsey RESET Test | ||||

| Value | df | Probability | ||

| t-statistic | 1.30149 | 0.69 | 0.197 | |

| t-Stat | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ho1 | REE does not cause LCO2 | 11.69345 | 0.039238 |

| Ho2 | POT does not cause LCO2 | 8.420643 | 0.077329 |

| Ho3 | LTES does not cause LCO2 | 3.1387 | 0.678 |

| Ho4 | LGDP does not cause LCO2 | 9.587872 | 0.087791 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alfiutouri, A.F.A.; Adedokun, M.W. Navigating Environmental Concerns: Assessing the Influence of Renewable Electricity and Eco-Taxation on Environmental Sustainability Using Nonlinear Approaches. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10846. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310846

Alfiutouri AFA, Adedokun MW. Navigating Environmental Concerns: Assessing the Influence of Renewable Electricity and Eco-Taxation on Environmental Sustainability Using Nonlinear Approaches. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10846. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310846

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlfiutouri, Alsideek Faraj A., and Muri Wole Adedokun. 2025. "Navigating Environmental Concerns: Assessing the Influence of Renewable Electricity and Eco-Taxation on Environmental Sustainability Using Nonlinear Approaches" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10846. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310846

APA StyleAlfiutouri, A. F. A., & Adedokun, M. W. (2025). Navigating Environmental Concerns: Assessing the Influence of Renewable Electricity and Eco-Taxation on Environmental Sustainability Using Nonlinear Approaches. Sustainability, 17(23), 10846. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310846