1. Introduction

In 2023, the European Union launched its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), imposing tariffs on carbon-intensive imports from countries with weaker climate policies. Similar green protectionism measures are spreading globally—from the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act’s domestic content requirements to proposed border carbon adjustments in Canada and the UK. These policies share a common challenge: how do importing countries assess whether trading partners’ climate commitments are genuine or merely greenwashing? When doubt prevails, even well-intentioned green subsidies by exporting nations may trigger punitive tariffs driven by skepticism rather than environmental reality.

This trust problem has profound consequences. When trading partners doubt each other’s commitment, they impose high credibility tariffs as insurance against policy reversals. These tariffs, in turn, discourage the very green investments they aim to promote—creating a vicious cycle where skepticism becomes self-fulfilling [

1,

2]. Real-world examples abound as follows: U.S. skepticism of China’s carbon neutrality pledge, EU concerns over developing countries’ green subsidy sustainability, and mutual distrust over verification and monitoring standards. The resulting policy uncertainty delays clean-technology investments, distorts capital allocation, and undermines the global coordination needed for effective climate action [

3,

4].

Existing research has established two key insights: first, climate policies must be perceived as credible and durable to stimulate sustained private-sector engagement [

5,

6]; second, border measures may adapt endogenously to cross-country policy differences [

7,

8]. However, a critical gap remains. Current models treat tariff policies as fixed or exogenous, missing the dynamic interplay whereby (i) exporters send policy

signals about their commitment (e.g., subsidy announcements, and carbon tax levels) rather than directly revealing their true type; (ii) importers update their

beliefs—their subjective assessment of commitment credibility—based on these noisy signals; and (iii) border tariffs respond to these evolving beliefs rather than objective commitment levels. This belief-contingent channel introduces two key frictions:

signal noise (cognitive bias or data verification challenges distort interpretation) and

reputation decay (credibility erodes without continuous reinforcement). Together, these frictions can trap countries in low-trust, high-tariff equilibria disconnected from economic fundamentals.

To address this gap, this study develops a dynamic signaling framework that connects exporters’ repeated policy signals, importers’ Bayesian belief updating, optimal tariff responses, and welfare outcomes for both parties. (Technically, the framework models a repeated game where the exporting government’s commitment type is private information, signals are observed with noise, and the importing government sets CBAM tariffs based on posterior beliefs derived from Bayesian updating subject to reputation depreciation.)

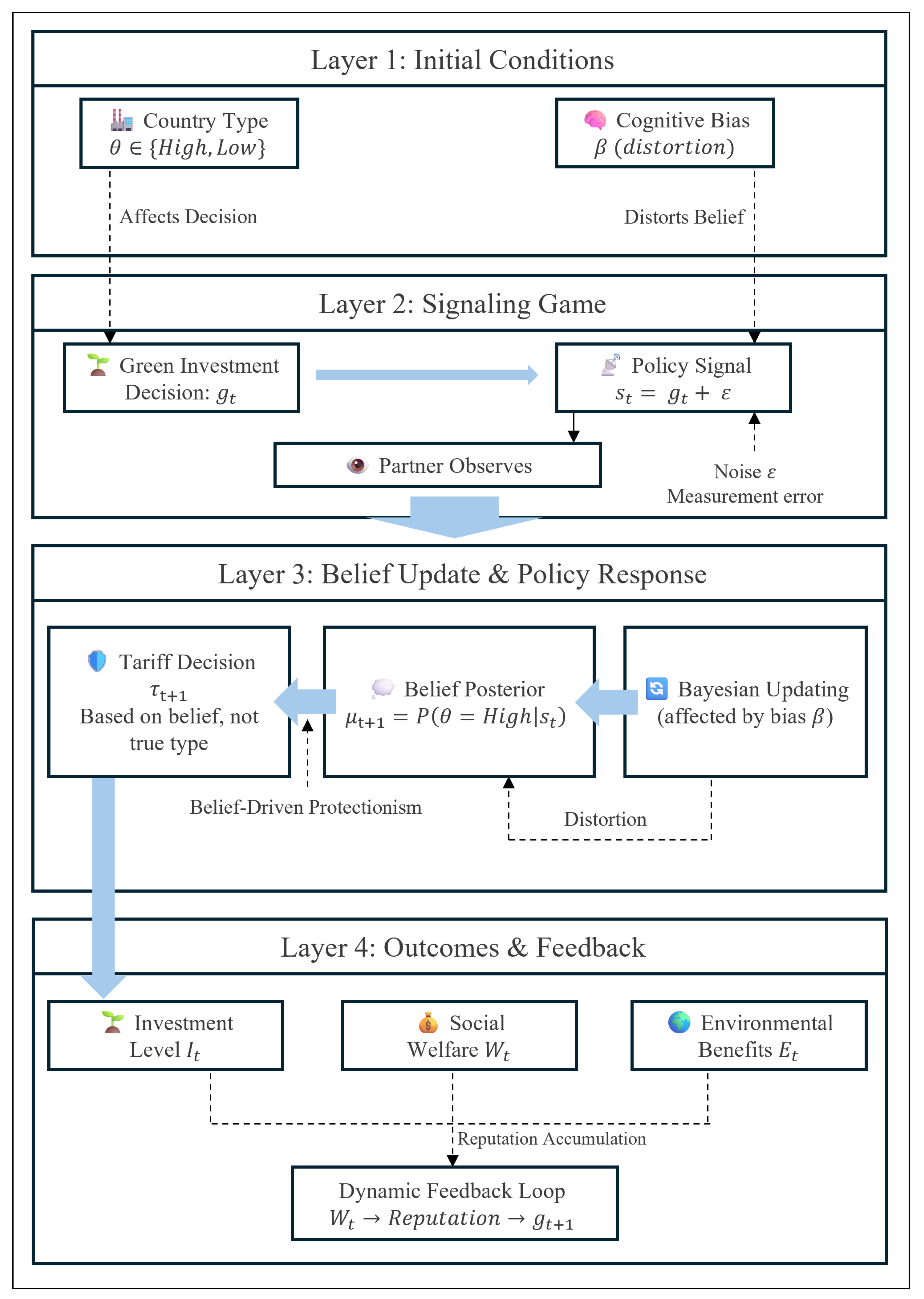

Figure 1 provides a conceptual overview of this framework, illustrating how signals flow through belief formation to policy responses and welfare outcomes, with reputation feedback closing the loop.

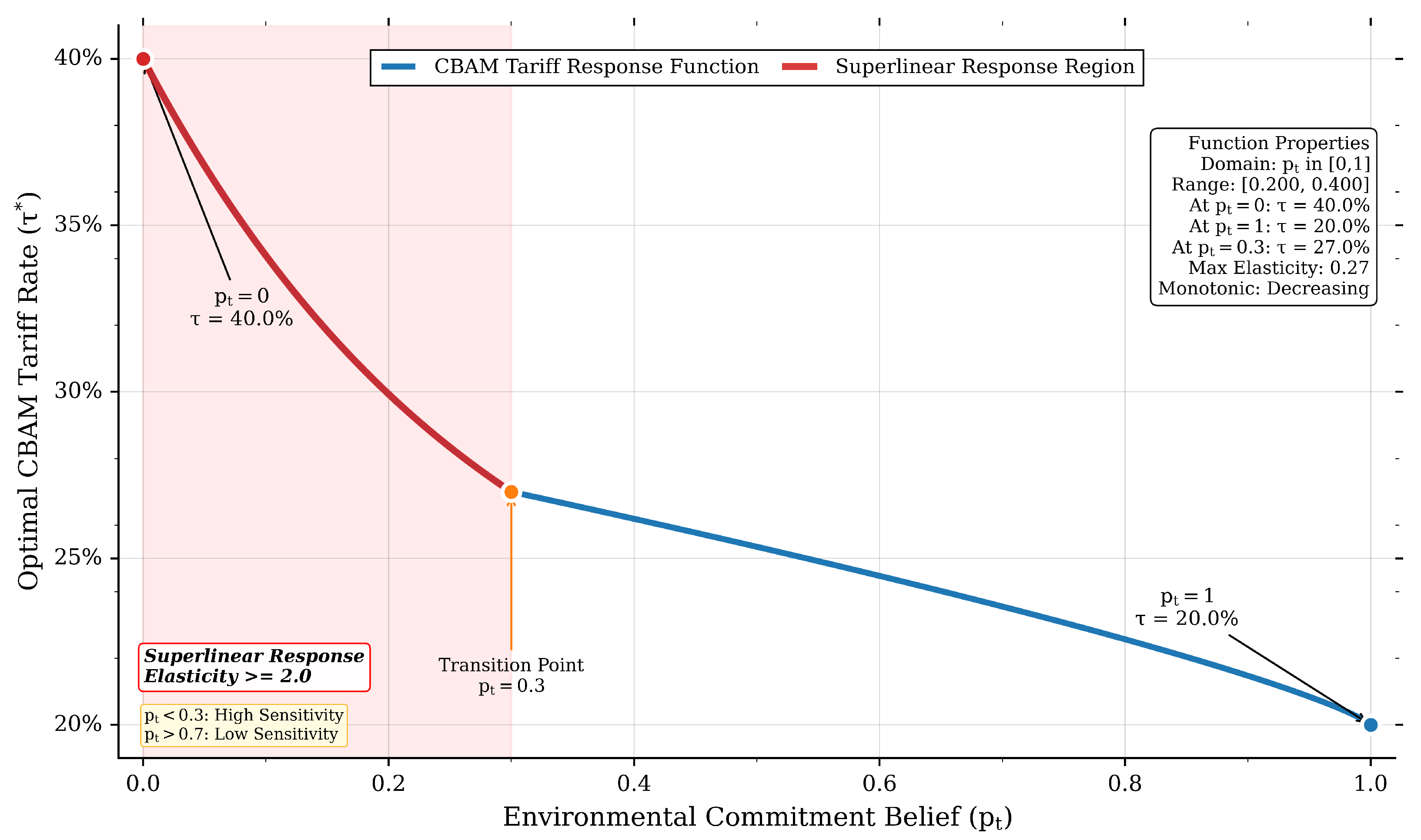

The analysis yields three main contributions. First, the study shows that countries with initially low reputation face a catch-22: even substantial green investments fail to reduce tariffs because past negative signals dominate current efforts. The importer’s tariff response is superlinearly steep in the low-belief region—small drops in perceived credibility trigger disproportionately large tariff increases. This explains why some countries remain locked in high-tariff equilibria despite genuine commitment, analogous to debt traps where poor credit history becomes self-reinforcing. (Formally, the model derives a CBAM reaction function with high elasticity for , providing a micro-founded explanation of belief-driven protectionism in climate–trade interactions.).

Second, even for genuinely committed exporters, reputation naturally decays over time-absent continuous positive signaling—a form of political memory loss. This creates a treadmill dynamic: sustained high investment is required not to build reputation but merely to maintain it. The calibrations show that moderate reputation decay () can reduce long-run beliefs by 45% relative to perfect memory, keeping countries perpetually in the high-sensitivity tariff zone. (Technically, the model parameterizes reputation depreciation and demonstrates that it generates path-dependent equilibria where belief steady states remain in the superelastic region of , amplifying investment suppression.).

Third, not all welfare losses stem from genuine climate ambition gaps. This study quantifies losses arising specifically from signal noise and reputation decay—frictions that could be reduced through improved transparency, verification, or legal commitment mechanisms. The baseline calibration attributes 30% of aggregate welfare loss to information and credibility frictions rather than fundamental policy divergence. This decomposition informs targeted policy interventions: third-party verification of subsidy durability, standardized disclosure of green-policy trajectories, or legally binding climate commitments that reduce signal noise.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows.

Section 2 reviews the existing literature on signaling, policy credibility, and climate–trade instruments, positioning the belief-contingent framework within this landscape.

Section 3 introduces the theoretical model, detailing the belief-updating mechanism and reputation dynamics (see

Figure 1 for a visual overview).

Section 4 presents quantitative analyses demonstrating how signal noise and reputation decay affect tariff levels, green investment, and welfare outcomes.

Section 5 discusses policy implications, including interventions to escape credibility traps and mitigate reputation treadmill effects.

Section 6 concludes with limitations and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

This section positions the manuscript at the intersection of signaling theory, reputation mechanisms, and climate-related trade policy under incomplete information. We review how policy signals influence credibility, examine strategic interactions among climate–trade instruments, and explore supply-chain coordination mechanisms. The objective is to identify the gap our belief-contingent framework addresses.

2.1. Signaling, Reputation, and Policy Credibility

Signaling theory provides foundational insights for climate–trade frameworks: where types are privately known, costly signals can differentiate high-commitment from low-commitment actors [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Three factors—signal cost, observability, and commitment horizon—determine whether receivers update beliefs toward separating or pooling outcomes. Recent applications of signaling theory in high-uncertainty markets [

13] and international platforms [

14] demonstrate how information asymmetry shapes strategic interactions, while empirical evidence from financial markets confirms the signaling value of credible commitments [

15].

Climate policy effectiveness hinges on credibility and perceived durability. Evidence from the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) demonstrates that policy credibility critically influences both effectiveness and efficiency [

5], while cross-country analyses show that the credibility of environmental policy stringency (beyond declared levels) significantly affects sustainability outcomes [

16]. Policy uncertainty—in taxation or regulatory domains—impacts emissions through delayed investment and distorted capital allocation [

17]. When political or informational constraints limit instrument efficacy, second-best combinations of taxes, standards, and border measures become necessary [

18]. Standardized data on tariff episodes improves identification of exogenous shocks to policy expectations within global value chains [

19].

Recent empirical evidence strengthens the credibility-effectiveness link. Sitarz et al. [

20] demonstrate that EU carbon prices signal high policy credibility and farsighted actor behavior, providing evidence that markets internalize commitment signals when institutional frameworks are robust. Victor et al. [

6] develop a framework for determining the credibility of international climate commitments, emphasizing verification mechanisms, institutional durability, and reputational consequences as key determinants. Campiglio et al. [

1] show that heterogeneous expectations and uncertainty in climate policy create belief formation dynamics where agents discount stated commitments based on perceived implementation risk—a channel analogous to our Bayesian updating with cognitive noise. Dolphin et al. [

3] argue that net-zero targets compel a backward induction approach requiring dynamic consistency in policy commitment, as future credibility depends on current actions’ alignment with declared long-term objectives—a mechanism central to our credibility trap framework.

While existing work emphasizes the importance of sustained signaling for credibility, the scenario wherein noisy signals and reputation decay directly shape the importing nation’s climate-related trade responses through endogenous belief updating remains underexplored.

2.2. Climate–Trade Policy Instruments: Design and Strategic Interaction

Political economy frameworks highlight why governments prefer subsidies over carbon taxes: visibility and incidence differ, with subsidies mobilizing constituencies and aligning incentives toward cleaner technologies while carbon taxes face electoral resistance [

21]. The emerging green industrial policy trend reflects open-economy considerations—securing supply chains, harnessing learning-by-doing, and mitigating geopolitical risks [

22].

A systematic review by Zhong & Pei [

7] synthesizes 97 CBAM studies spanning 2004–2021, identifying three core policy objectives: protecting fair competition, reducing carbon leakage, and limiting global welfare costs. Their analysis reveals that policy design and economic characteristics jointly determine CBAM effectiveness, with no one-size-fits-all approach. Recent empirical assessments provide critical insights: Bellora & Fontagné [

23] analyze the EU’s search for an optimal CBAM design, while Zhong & Pei [

24] examine China’s carbon market response from a CBAM perspective. Beaufils et al. [

8] assess different CBAM implementation designs using a comprehensive multi-model approach, and Fontagné & Schubert [

25] provide an economic framework for understanding border carbon adjustment rationales and impacts. Olasehinde-Williams & Akadiri [

26] empirically link environmental policy stringency to carbon leakage patterns, strengthening the case for EU CBAM as a response to competitiveness and leakage concerns. Beaufils et al. [

8] assess different CBAM implementation designs and their impacts on trade partners, finding significant heterogeneity across design choices—coverage scope, carbon content determination methods, and revenue recycling mechanisms critically affect distributional outcomes. Wettestad [

27] analyzes multi-level institutional mechanisms that shaped and sustained the EU CBAM through shifting political reinforcement, highlighting how credibility is maintained through layered governance structures.

The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism has been critiqued for limited standalone decarbonization potential, with climate clubs and targeted subsidies proposed as complements or alternatives depending on participation and leakage elasticities [

28]. Optimal carbon tax design serves as a reference for externality pricing [

29], but implementation details matter: practical recommendations for border carbon adjustments emphasize comprehensiveness, emissions assessment, domestic pricing alignment, and administrative feasibility [

30]. Corporate and sectoral reactions to CBAM depend on timing, implementation specifics, international competition, and technology choices [

31,

32]. Löfgren et al. [

33] examine sector-specific green industrial policy design for basic materials industries, highlighting coordination challenges between domestic subsidies and border adjustment mechanisms when commitment signals are imperfect.

Existing analyses treat border adjustments as exogenous policy shocks. Missing is a dynamic framework where CBAM levels depend on evolving beliefs about partner commitment, shaped by noisy signals and reputation decay, with tariff responses endogenously adjusting to credibility assessments.

2.3. Supply-Chain Coordination and Reputation Dynamics

Open-economy climate policy operates within global supply chains. Carbon tariffs reallocate value across supply chains and induce firm-level adaptation—relocation, input substitution, and contract redesign [

34]. Supply-chain policies interact with carbon taxes, caps, and trading schemes to shape incentives across tiers and jurisdictions [

35]. Technology choice and R&D sharing under taxation and uncertainty generate non-linear welfare responses and strategic information disclosure incentives [

36].

The distinct literature examines cooperation emergence as agents build reputations and revise beliefs within networks. Trust–consensus models formalize the co-evolution of social trust and consensus dynamics [

37], while empirical evidence from sharing economies illustrates how institutional configurations influence trust evolution [

38,

39]. Recent advances include reputation-driven state transitions [

40], learning mechanisms with reputation considerations [

41], update rules incorporating combinatorial memory [

42], and external social monitoring that curtails free-riding [

43]. These findings suggest that signal quality, frequency, and observability may independently influence supply-chain coordination on emissions reporting and low-carbon technology adoption.

Woods [

44] examines shifting policy signals in globalized technology regimes, demonstrating how signal volatility—analogous to our signal noise parameter (

)—undermines coordination and trust in international supply chains, creating policy uncertainty that delays investment and distorts resource allocation across borders.

While reputation mechanisms are well studied in abstract cooperation settings, their integration into climate–trade policy design—specifically, how reputation decay and noisy belief updating shape optimal tariff setting under incomplete information—remains underdeveloped.

2.4. Research Gap and Contribution

Synthesizing the above, three stylized facts emerge as follows: (i) policy signals in open-economy climate contexts are noisy and repeated; (ii) credibility and reputation are essential for sustained green investment; and (iii) climate–trade mechanisms interact strategically with domestic instruments. However, existing frameworks treat these elements separately or as exogenous shocks.

This study develops a dynamic model where the importing nation’s CBAM decisions explicitly depend on Bayesian belief updating about the exporting partner’s commitment, subject to signal noise () and reputation decay (). This endogenizes trade policy responses to credibility concerns, revealing mechanisms such as the credibility trap (where low initial belief locks countries into high-tariff equilibria despite genuine effort, with hyperelastic responses for ) and the reputation treadmill (where maintaining credibility requires escalating costly signals due to natural decay).

3. Research Hypotheses

Building on the theoretical framework and literature synthesis, this study advances five testable hypotheses concerning the dynamics of belief-contingent Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms under incomplete information.

3.1. Credibility Trap Hypothesis (H1)

There is a critical belief threshold below which importers exhibit hyperelastic tariff responses to perceived commitment signals, creating credibility trap dynamics that prevent coordination even when exporters maintain genuine green policy commitment.

The theoretical model predicts that when the importer’s belief about the exporter’s commitment capacity falls below a critical threshold , marginal decreases in perceived credibility trigger disproportionately steep tariff increases. Specifically, for , the tariff elasticity with respect to belief changes exceeds 2, creating a self-reinforcing credibility trap: low initial beliefs ⇒ high tariffs ⇒ reduced incentive for genuine commitment ⇒ belief confirmation ⇒ persistent high-tariff equilibrium. This hypothesis is testable through analysis of CBAM tariff trajectories across trading partners with varying initial credibility assessments, examining whether tariff volatility exhibits threshold behavior at low belief levels.

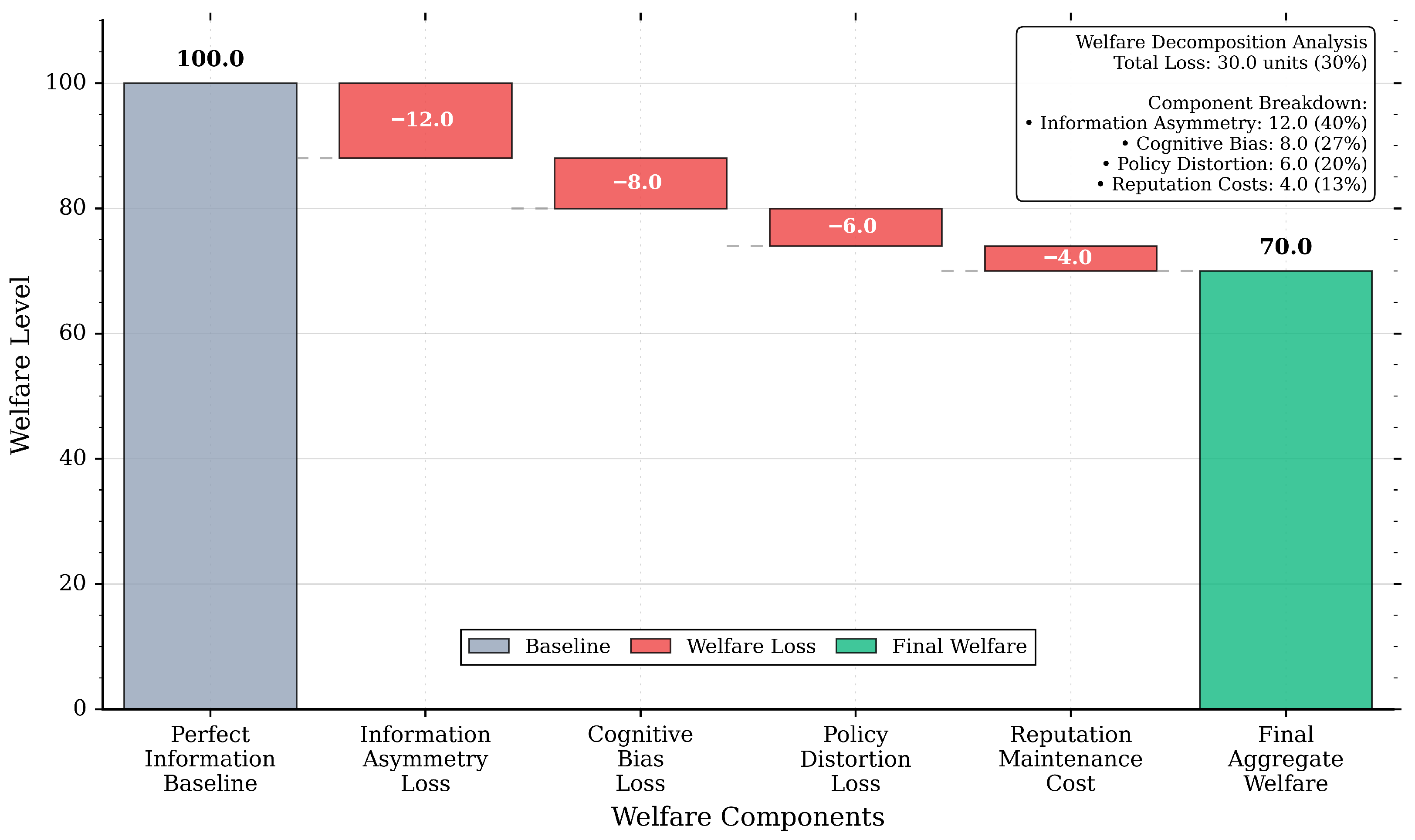

3.2. Information Friction Welfare Loss Hypothesis (H2)

Information frictions arising from signal noise and reputation decay impose aggregate welfare losses equivalent to 20–40% of potential coordination gains, with information opacity dominating other friction sources.

The calibrated model decomposes total welfare losses into four components: information opacity (inability to verify commitment), cognitive biases in belief formation, policy distortions induced by credibility concerns, and reputation maintenance costs. The theoretical prediction is that opacity costs dominate, accounting for approximately 40% of total welfare loss, while cognitive biases contribute 27%, policy distortions 20%, and reputation costs 13%. This hypothesis can be tested by comparing coordination outcomes and welfare metrics across institutional environments with varying degrees of transparency, third-party verification, and commitment observability.

3.3. Signal Noise Amplification Hypothesis (H3)

The impact of signal noise () on coordination failure is non-linear, with small increases in noise producing disproportionate welfare losses when initial credibility is already low.

The model incorporates noisy Bayesian updating where the importer observes , with , representing cognitive and informational noise. The theoretical prediction is that the marginal welfare cost of noise is convex in initial belief levels, such that noise amplification effects are most severe when . This creates interaction effects between signal quality and initial credibility: poor signal quality is particularly damaging in low-trust environments. Empirical testing would examine whether coordination success exhibits super-additive responses to combined improvements in signal quality and initial credibility.

3.4. Reputation Decay Persistence Hypothesis (H4)

Natural reputation decay () creates a “reputation treadmill” effect whereby maintaining credibility requires escalating costly signals over time, even in the absence of policy changes.

The dynamic framework incorporates endogenous reputation decay at rate , such that beliefs evolve according to . The theoretical prediction is that exporters must increase signaling costs at rate proportional to simply to maintain constant credibility levels, independent of actual commitment. This treadmill effect predicts that observable green policy expenditures should exhibit upward trends over time even in countries with stable underlying commitment, and that expenditure volatility should correlate with (proxied by institutional stability measures). The hypothesis is testable through panel analysis of green industrial policy spending trajectories across countries.

3.5. Verification Mechanism Effectiveness Hypothesis (H5)

Third-party verification institutions reduce welfare losses primarily through the opacity channel rather than through direct signal quality improvements, with effectiveness exhibiting diminishing returns at high verification intensity.

The policy intervention analysis predicts that introducing credible verification mechanisms (effectively reducing ) generates welfare gains through two channels: direct signal quality improvement and indirect opacity reduction through commitment observability. The model predicts that opacity reduction dominates, accounting for approximately 65% of total welfare gains from verification, because verification primarily makes commitment capacity observable rather than making signals themselves more precise. Furthermore, marginal welfare gains should exhibit diminishing returns beyond moderate verification levels, as residual welfare losses shift toward cognitive bias and policy distortion components that are less sensitive to verification intensity. This hypothesis can be tested by examining heterogeneous treatment effects of verification institutions across different institutional contexts and baseline credibility levels.

3.6. Empirical Implications and Testability

Each hypothesis generates empirically testable predictions:

Hypothesis 1. CBAM tariff elasticities should exhibit threshold behavior, with significantly higher volatility and belief-responsiveness below .

Hypothesis 2. Welfare gains from coordination should vary systematically with institutional transparency measures, with opacity metrics explaining dominant variance.

Hypothesis 3. Coordination success should respond super-additively to combined improvements in signal quality and initial credibility (interaction effects).

Hypothesis 4. Green policy expenditures should exhibit positive time trends controlling for actual emission trajectories, with trend slopes correlating with institutional stability proxies.

Hypothesis 5. Verification institution effectiveness should exhibit concave returns, with heterogeneous treatment effects larger in low-baseline-credibility contexts.

These hypotheses provide a structured research agenda for empirical validation using cross-country panel data on CBAM tariffs, green industrial policy expenditures, emission trajectories, and institutional quality metrics. The model’s quantitative predictions (threshold values, welfare decomposition shares, and elasticity magnitudes) offer precise targets for empirical testing, distinguishing this framework from purely qualitative signaling models.

4. Model and Methodology

Prior to introducing the formal model, we offer an intuitive exposition of the fundamental mechanisms. Consider an exporting government that provides subsidies for green technology yet encounters political and fiscal challenges that might compel it to withdraw support. The importing government is unable to directly observe the true commitment capacity (referred to as its type) of the exporting government and must deduce it from the consistency of the observed policies.

Several frictions complicate this inference problem. First, information asymmetry arises, as the exporter’s commitment constitutes private information. Second, cognitive noise occurs as the importer may misconstrue signals due to political biases, challenges in data verification, or the presence of strategic ambiguity. Third, reputation decay takes place as absent negative signals, where credibility experiences a natural erosion over time attributable to finite political memory.

These frictions culminate in a phenomenon termed as a “credibility trap”. When the confidence of the importer in the exporter’s commitment declines below a certain threshold (approximately 30% according to our calibration), the optimal CBAM tariff response becomes hyper-sensitive: minor adverse fluctuations in belief precipitate disproportionately large increases in tariffs. This steep gradient remains a challenge even for exporters with genuine commitment, as the natural attenuation of reputation hinders beliefs from significantly surpassing the threshold, resulting in a “reputation treadmill”, where continual effort is imperative to merely sustain credibility.

The subsequent model encapsulates these conceptual intuitions within the framework of a dynamic Bayesian game involving four participants (comprising two governments and two firms), systematically derives the Perfect Bayesian Equilibrium, and employs structured simulations to depict the quantitative dimensions of trade frictions influenced by belief dynamics.

4.1. Model Setting

This chapter constructs a dynamic Bayesian game to examine the strategic interplay between an exporting nation’s green subsidy policy and an importing nation’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). The primary innovation resides in conceptualizing the exporter’s policy commitment capacity as private information, thus giving rise to a signaling game wherein the persistence of subsidies constitutes a costly signal of credibility.

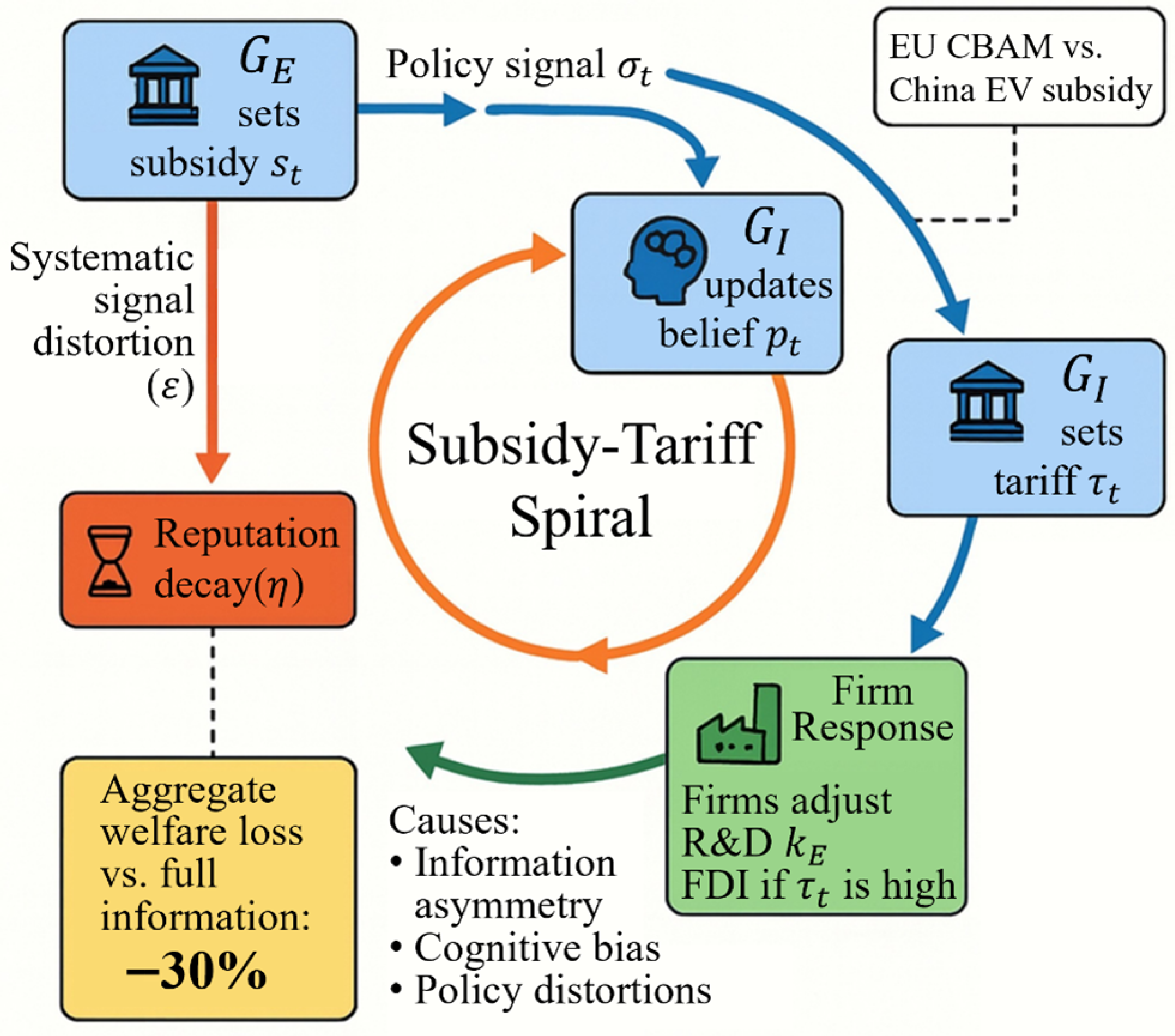

As depicted in

Figure 2, this framework internalizes the credibility of the policy, the revision of beliefs, and firm responses under conditions of incomplete information. This enables an examination of the emergence of subsidy–tariff spirals and illustrates how informational asymmetries result in substantial welfare losses, reaching up to 30.5% compared to scenarios with complete information. The subsequent portions of this section formalize these interactions, establish equilibrium conditions, and prepare for the ensuing quantitative analysis.

4.1.1. Game Participants and Timing

The model comprises four rational actors who maximize their respective rewards.

(1) Exporting country government : Committed to supporting its technologically leading company in the charging station sector. Its objective is to maximize national social welfare, comprising the dominant firm’s global profits, positive knowledge spillovers, and global environmental benefits from technological progress. However, implementing support policies (e.g., subsidies) entails fiscal costs.

(2) Importing country government : The purpose is to maximize domestic welfare through trade and environmental policies. Its welfare function includes domestic consumer surplus, profits of the domestic firm , fiscal revenue from tariffs and CBAM, and environmental benefits (or avoided damage) from reduced carbon emissions.

(3) Exporting country company : A global leader in charging station technology, producing in the exporting country. It faces strategic decisions on

R&D investment level to reduce production costs and product carbon footprint;

Sales volume in the importing market ();

Whether to serve the importing market through exports (facing tariffs/CBAM) or through foreign direct investment (FDI) to bypass border adjustments.

(4) Importing country company : A technology follower in charging stations, primarily operating domestically. Its decisions include technology investment () and domestic production volume (), competing with in the importing market. The model employs a discrete, infinite-horizon, multistage game structure. In each period t, the sequence unfolds as follows:

Phase 1: Policy Formulation

(1) Exporting country government action: At the start of t, selects and announces its intensity of green subsidies for , which aims to reduce innovation costs. This policy commitment is subject to uncertainty.

(2) Importing country government actions: Observing and based on its current belief about ’s commitment capacity, simultaneously sets a comprehensive border adjustment tax rate on imports from . This rate incorporates traditional tariffs and a CBAM component based on the carbon content of the product.

Phase 2: Firm Decision-Making

(1) Observing the combination of policies (, ), companies and make business decisions simultaneously.

(2) Technology investment: and select investment levels and .

Phase 3: Market Competition

(1) Given investment levels, and engage in Cournot quantity competition within the importing market, simultaneously choosing production levels and to maximize current profits.

(2) The market price is determined by total output = + via an inverse demand function.

4.1.2. Incomplete Information and Belief Updating

This study departs from traditional models’ static assumption of policy invariance by introducing a mechanism of “incomplete commitment”. This reframes policy uncertainty not as an exogenous random process but as an endogenous signaling game arising from information asymmetry, consistent with the Bayesian learning approach applied in green investment contexts (Dalby et al. [

45]). This transformation draws inspiration from the Harsanyi transformation, converting a game of incomplete information into one of imperfect information with “Nature” as a player.

(1) We model the exporting government’s commitment capacity ′ as its private information, or “type” , where . Here, represents the probability that an active subsidy policy ( > 0) will be permanently terminated in the next period. Thus, denotes a “high-commitment” (resolute) government with greater policy continuity, while denotes a “low-commitment” (wavering) government more susceptible to policy interruptions due to various circumstances.

(2) Beliefs and prior information: The importation government and the companies , cannot directly observe the true type of ’s . They possess only a prior distribution on . At the beginning of the game (t = 0), all uninformed participants share a common prior belief , representing the initial probability assigned to being the type of high commitment.

(3) Signals and Bayesian updating: At the end of each period t, if the current subsidy

> 0, a public signal

is observed. The likelihood of the signal depends on the true type of

’s:

Uninformed participants update their beliefs about the

’s type using Bayes’ theorem. Let

be the belief at the beginning of period t. After observing

, the posterior belief

for period t + 1 is

(4) Incorporating cognitive bias: Deviating from classical rational updating assumptions, we incorporate insights from behavioral game theory and political psychology. The importation government may exhibit systematic cognitive biases, leading to misinterpretation of observed signals. This is grounded in real-world complexities:

(a) Political biases and domestic pressures: Lobbying by protectionist interests, confirmation bias based on pre-existing negative views of strategic competitors, and populist electoral demands may push toward negative interpretations of motives, even given positive signals.

(b) Information barriers and verification difficulties: Lack of transparency in the details of the subsidies, complexity in assessing the benefits of green technology/the carbon footprint of the products, and unreliable data verification hinder ’s ability to accurately assess ’s true commitment () and policy effectiveness.

(c) Strategic motives and ambiguity:

may strategically feign distrust for deterrence; simultaneously, signals from

may lack inherent clarity. We model this signal misinterpretation via a ’cognitive noise’ parameter

, representing the probability that

misinterprets the true signal

. For example, the update of the posterior belief upon observing

= continue becomes:

Given that implies , observing “continue” generally strengthens the belief in a high-commitment type (), enhancing the reputation of the policy. If = terminate, the game enters a subsidy-free absorbing state; subsequent posterior beliefs are irrelevant for future decisions.

(5) Key behavioral frictions: To enhance realism, our belief evolution mechanism incorporates two critical frictions:

(a) Cognitive noise (): As defined above, capturing biased signal interpretation.

(b) Reputation depreciation (): Reflecting finite political memory. Reputation naturally decays over time, even without negative signals. Thus, the posterior belief updated in period t depreciates before period t+1 begins: .

The interplay of and creates a “reputation treadmill”: exporting governments must not only send strong signals capable of penetrating cognitive noise but also sustain these signals to counteract the natural erosion of reputation, significantly enriching the model’s dynamics.

(6) Belief as a state variable: The belief is the key endogenous state variable in our model. It encapsulates the influence of all the historical information on the future path of the game, acting as a sufficient statistic. The strategies of all rational participants are critically dependent on this shared belief.

4.1.3. Core Assumptions and Parameterization

To facilitate analytical tractability and yield clear economic insight, we adopt the following specific functional forms and assumptions.

(1) A firm’s technological investment simultaneously reduces its marginal production cost and unit carbon emissions. Both effects exhibit diminishing marginal returns.

(a) Marginal production cost: The marginal production cost for firm i is given by

Here, is the initial marginal cost (without investment), and > 0 captures the efficiency of investment in cost reduction. A higher implies a greater reduction in costs per unit of investment.

(b) Unit carbon emissions: The unit carbon emissions for firm i are

Here, is the initial unit emissions, and > 0 captures the efficiency of investment in emission reduction.

The ratio has significant economic implications, reflecting the inherent bias of a firm’s R&D investment. A high ratio indicates that investment is naturally more effective in reducing costs than in reducing emissions. Consequently, to achieve substantial emission reductions, an importing country’s CBAM policy must be sufficiently potent to counteract this bias and incentivize firms to redirect resources towards green technology R&D.

(2) Costs of technology investment: We model the cost of technology investment as a convex function:

This convexity reflects the increasing marginal costs of R&D, implying that achieving further technological progress becomes progressively more difficult and expensive. This formulation ensures the existence of a finite optimal investment level.

(3) Foreign direct investment (FDI) costs: If the exporting company opts for FDI to localize production within the importing country, it incurs a one-time fixed cost F > 0. This cost includes expenses related to factory construction, the establishment of distribution networks, and the compliance with local regulatory requirements. In return, ’s products sold in the importing market avoid the border adjustment tax , but become subject to the same domestic environmental regulations (for example, a uniform carbon tax ) as the domestic company .

(4) Market demand: The inverse demand function on the market of the importing country is linear.

4.2. Equilibrium Analysis

This section employs backward induction to solve the model’s Perfect Bayesian Equilibrium (PBE). PBE requires sequential rationality (players’ strategies are optimal at every information set) and belief consistency (beliefs are updated via Bayes’ rule along the equilibrium path). The solution sequence proceeds as follows: the firm subgame importing government’s optimal response, and the exporting government’s dynamic programming problem.

4.2.1. Firm Subgame: Investment and Competition Under Belief Dependence

In the second and third stages of the game, firms in both countries make investment decisions () and output () decisions. These decisions depend on the observed combination of government policy (, ) and the belief of the common market in the type of export commitment of the government. Although does not directly enter the current profit functions of firms, it critically influences their long-term investment strategies by shaping expectations about future tariff behavior (, , …).

We first solve a Markov subgame under a fixed belief , assuming that the firms perceive the current policy-belief environment as persistent. While a complete dynamic analysis requires solving firms’ Bellman equations, the core strategic interactions are captured by analyzing optimal responses within this static subgame.

The firms’ profit functions are specified as follows.

(1) Exporting firm (

) profit:

Here, the subsidy directly reduces ’s R&D investment costs by proportion , incentivizing innovation. represents the marginal production cost.

(2) Import company (

) profit:

faces domestic environmental regulation costs abstracted as unit cost , assumed non-discriminatory (e.g., ) under a uniform carbon price. is its marginal cost.

The Cournot–Nash equilibrium of this subgame is found by solving the system of first-order conditions derived from profit maximization:

Equations (

10) and (

12) yield standard Cournot output reaction functions. Equations (

11) and (

13) characterize the optimal investment responses. Simultaneously solving these equations yields the unique Nash equilibrium solution for the firm subgame:

. Crucially, all equilibrium variables are functions of the exogenous government policy variables (

), implying unique and predictable firm behavior given government actions.

From a dynamic game perspective, this Nash equilibrium constitutes a Markov Perfect Equilibrium (MPE) for the subgame. Firm strategies () depend solely on current payoff-relevant state variables () and are history independent.

4.2.2. Belief-Dependent FDI Decision

The exporting firm’s () choice between exporting and undertaking foreign direct investment (FDI) can be conceptualized as a real options problem. FDI represents an irreversible investment involving a sunk cost (F > 0) that grants the firm the right to circumvent uncertain future tariffs () imposed by the importing country.

Under conditions of incomplete information, this decision becomes significantly more complex due to its dependence on the evolving belief regarding the exporting government’s commitment type (). Firms must therefore compare the expected net present value (NPV) of future profits in the “export mode” versus the “FDI mode”, explicitly accounting for the dynamics of .

(1) Value functions in alternative modes: The export mode value

represents the discounted sum of the expected future profits attainable by

if it continues exporting under the current subsidy regime (

> 0).

solves the following Bellman equation, which incorporates expectations about the future evolution of beliefs

and the resulting optimal import tariff

set by

:

Here, denotes the expectation conditional on the realization of the public policy continuation signal (which depends on the true type of government ) and the subsequent update of Bayesian belief incorporating cognitive noise () and depreciation ().

The value of the FDI mode

is the expected NPV obtained if

chooses FDI. It involves incurring the sunk cost F upfront and transitioning to local production within the importing country thereafter. Under FDI,

avoids future border adjustment taxes (

) but becomes subject to the importing country’s domestic environmental regulations (e.g., a uniform carbon tax

), competing on equal regulatory footing with

. Its value is

where

represents the equilibrium profit of

operating as a local company in the importing country market from period t onward.

(2) FDI trigger condition.

At the start of each period t,

compares the value functions under the two modes. The FDI trigger condition is

Crucially, this condition explicitly depends on the dominant belief . A deterioration of the reputation of the policy (manifested as a declining ) reduces the expected value of the export mode (), thus increasing the relative attractiveness of the FDI. This belief-dependent trigger mechanism implies that the importer government (), when setting its optimal border tax , must strategically consider the potential to trigger FDI. Excessively high tariff rates can induce to bypass the border tax entirely via FDI. Once becomes a local producer, not only loses all the tariff revenue associated with imports from , but also sees its primary policy lever to influence the carbon footprint () of rendered ineffective. Consequently, the credible threat of FDI itself acts as a deterrent against overly aggressive protectionism by , potentially constraining tariffs to relatively moderate levels to avoid precipitating this structurally unfavorable outcome.

4.2.3. Optimal Response of the Importing Country’s Government

Given the observed intensity of subsidies and the dominant belief about the type of commitment of the exporting government , the importation government selects the optimal component rate of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) . (Note: We focus on the CBAM component within the comprehensive border tax , where represents the tax per unit of carbon emissions.) The objective of is to maximize its expected social welfare .

Current-period social welfare

is defined as

Each component is a function of the equilibrium behavior of the firms derived in

Section 4.2.1:

Consumer surplus: .

Profits from the domestic company: directly obtained from the Cournot–Nash equilibrium solution of the firm subgame.

Tariff revenue: Revenue generated from the CBAM levy on total embedded carbon in imports, .

Environmental costs: the total environmental externality associated with consumption activities in the market, valued at the marginal social cost of carbon (), , and this expression captures the net carbon damage, implicitly assuming that the domestic firm is subject to domestic environmental regulation (abstracted as a unit cost , for example under a uniform carbon price regime, although the specific form of does not enter directly here).

Crucially, the equilibrium behaviors of all firms (

,

) depend on the true type of the exporting government

, since

influences firms’ long-term expectations and thus their cost structures and investment incentives (via its impact on expected future policies). Consequently,

’s optimization problem involves maximizing its expected welfare conditional on its belief

Solving the first-order condition for this maximization problem () yields the optimal CBAM rate of the importing government. This rate is expressed as a function of belief , defining the optimal reaction function . The properties of this function are pivotal in understanding the strategic interaction.

A central implication concerns the derivative . Its sign reveals the fundamental relationship between the importer’s belief and its protectionist stance:

: Indicates that a higher belief (stronger conviction that the exporter is a high-commitment type) leads to set a lower tariff. This reflects a “credibility reward” logic, a credible and sustained subsidy policy is perceived to more effectively incentivize long-term emission reduction investments by the exporting firm, thereby reducing the necessity for the importing country to employ stringent border carbon adjustments. Lower tariffs become optimal.

(theoretically possible but empirically less likely in this context): This would suggest that reacts more strongly to high-commitment exporters. This could stem from industrial protection motives dominating environmental objectives, viewing credible foreign industrial policy primarily as a competitive threat rather than an environmental partnership.

Our model’s core mechanism predicts , establishing the foundation for “belief-driven protectionism”; pessimistic beliefs (low ) trigger disproportionately high tariffs (high ).

4.2.4. Dynamic Optimization of the Exporting Country Government

The exporting government’s () decision-making is inherently dynamic and strategic, constituting a signaling game. When choosing its intensity of subsidy , a government of type must not only consider the immediate impact on current welfare but also anticipate how its policy choice (and its subsequent continuation or termination) influences the evolving belief of the importer about its type of commitment. This belief update critically affects the future optimal tariff response of the importer , thereby impacting future welfare streams of .

This complex intertemporal problem is formalized using a Bellman equation with belief state p. The value function

for a government of type

is defined as

where

denotes the welfare of the current period of

, given the belief p, the chosen subsidy s, and the optimal expected tariff response of the importer

. Its components are the following.

This comprises, as follows:

Profit () of the domestic firm ();

The fiscal cost of the subsidy ();

The environmental benefit of reduced emissions, valued at weight .

is the intertemporal discount factor.

denotes the expectation over the public policy continuation signal . The probability of signal realization depends on the true type .

is the updated posterior belief that enters the next period. Upon observation

(incorporating cognitive noise

and depreciation

),

is calculated using the Bayes rule as defined in

Section 4.1.2, followed by depreciation

The expectation term

evaluates the future value based on the probabilities of signal realization:

Here, is the updated belief under the policy continuation signal, and 0 represents the (normalized) terminal value upon policy termination (an absorbing state).

When characterizing equilibria, particularly separating equilibria where different types choose distinct subsidies (), the following incentive compatibility (IC) constraints must hold to ensure truthful signaling:

Types of high commitment (

) IC: Mimicking the low type must not be profitable.

Low commitment types (

) IC: Mimicking the high type must not be profitable.

These constraints reflect the core mechanism of costly signaling. Typically, the cost of mimicking the high-commitment type is prohibitively higher for a low-commitment government (), due to its intrinsically higher probability () of suffering the penalty of policy termination and losing all future benefits. This differential cost structure enables for credible separation.

5. Quantitative Analysis: Learning, Reputation, and Policy Interactions

We examine three key questions: (1) Does our model accurately predict how tariffs respond to trust levels? (2) How do information problems (signal noise, and reputation decay) trap countries in high-tariff situations? (3) What are the economic costs of these credibility frictions?

To elucidate and quantitatively affirm the intricate dynamic mechanisms and welfare implications emanating from the theoretical model introduced in earlier sections, this chapter undertakes a series of numerical simulations grounded in empirical data. The fundamental theoretical propositions of the model are systematically scrutinized. Through the analysis of the generated figures, a coherent analytical narrative is constructed, elucidating the evolution of posterior beliefs, quantifying the impact of behavioral frictions, and evaluating the aggregate social costs attributable to information imperfections.

5.1. Parameter Calibration and Baseline Scenario Setting

Before running simulations, we need to set realistic parameter values. We classify governments into two types: high-commitment (5% chance of abandoning green policies) and low-commitment (60% chance). We assume trading partners start with maximum uncertainty—a 50/50 belief about which type they are dealing with. These calibrations reflect real-world policy volatility observed in climate negotiations.

The quantitative analysis within this section is founded upon the model framework outlined in

Section 3, alongside the parameter calibration elucidated in

Table 1 (see

Appendix A for detailed parameter definitions and real-world calibration anchors). A fundamental element of the simulation environment is the meticulous depiction of the information structure and behavioral parameters, which are carefully crafted to embody the essential characteristics of international policy interactions.

We categorize the governments of exporting nations into two distinct types:

The high commitment type (), characterized by a very low probability of termination of the subsidy policy, and represents a stable and credible policymaker.

The low commitment type (), showing a higher probability of policy termination, reflecting a government that is potentially susceptible to wavering due to political or fiscal pressures.

In accordance with the principle of insufficient reason, we establish the initial beliefs of all participants as . This implies that the importing country commences with complete uncertainty about the exporting government’s type commitment.

5.2. Model Validation and Theoretical Fit

We test whether our mathematical model accurately predicts real-world tariff decisions by comparing theoretical predictions against computer simulations. The model performs remarkably well, explaining 88% of tariff variation across different trust levels. Most importantly, the model captures the “credibility trap” zone where low trust (belief < 0.3) triggers steep tariff increases—exactly the region where countries become stuck in high-tariff equilibria.

Our model is not just theory—it matches reality. When trading partners’ trust falls below 30%, we observe a “panic zone” where small drops in confidence cause massive tariff hikes. This validates our core mechanism: tariffs respond to perceived credibility, not just economic fundamentals. Countries operating in this zone face a policy version of walking on thin ice—any misstep triggers disproportionate punishment.

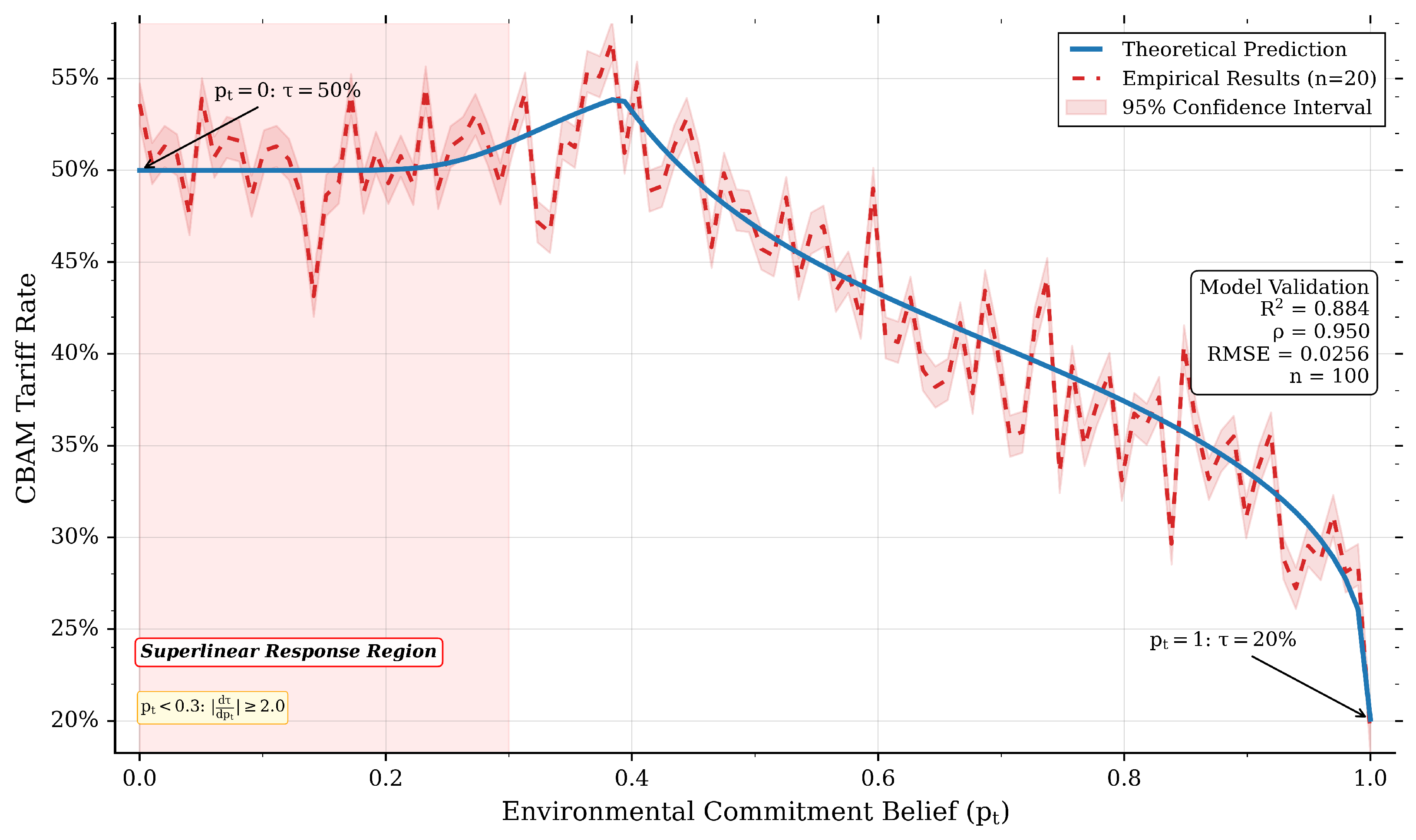

This subsection assesses the derived belief–response mapping by means of validation against Monte Carlo simulations.

Figure 3 presents a superposition of the theoretical CBAM schedule alongside simulated empirical tariffs, which are averaged over 20 iterations at each respective belief level

(illustrated in red, with a 95% confidence interval shaded). The degree of correspondence is notably high within our calibration framework, as indicated by an R

2 value of 0.884 (88% of variance explained—considered excellent in social sciences), a rank correlation

(near-perfect rank ordering), and a root mean square error (RMSE) of 0.0256 (average prediction error of 2.56 percentage points), calculated from n = 100 evaluation points. Two shape characteristics, as predicted by the model, are apparent. Firstly, the schedule exhibits a global downward trend, transitioning from 50% at

to 20% at

, aligning with the ’credibility reward’ mechanism, whereby enhanced beliefs in exporter commitment lead to a reduction in the optimal tariff. Secondly, a superlinear response region is observable at low belief levels (

; shaded), where

(elasticity greater than 2, meaning a 1% drop in belief triggers more than 2% tariff increase). This steep segment represents the belief-driven protectionism theorized, whereby minor declines in perceived commitment precipitate disproportionately large increases in tariffs.

When trading partners doubt your commitment (belief < 0.3), they react defensively with high tariffs—think of it as a “trust tax”. This creates a vicious cycle: high tariffs discourage green investment, which further erodes trust. Countries can become stuck in this credibility trap where genuine efforts do not pay off because past negative signals dominate current perceptions—a policy version of the debt trap where poor credit history makes it impossible to rebuild creditworthiness. Escaping requires pushing beliefs above the 0.3 threshold where tariff sensitivity eases.

The economic rationale for this curvature is clear. In the low-belief region (), importers are confronted with significant uncertainty regarding the continuance of green subsidies. Defensive protectionism is predominant; thus, the CBAM must be elevated to both internalize anticipated carbon externalities and prevent opportunistic reversals of subsidies by exporters with low commitment. As credibility is enhanced and beliefs exceed the threshold, the policy focus transitions from punitive measures to cooperative strategies: reduced CBAM rates afford firms the necessary latitude to engage in long-term green R&D, informed by the assurance that sustained subsidies will underpin their investments.

Importantly, the determination of the inflection point () is not arbitrary; it arises endogenously from the interaction between the importer’s welfare function—which accounts for domestic profits, consumer surplus, tariff revenue, and environmental costs—and the investment responses of firms. This endogenous threshold presents a coordination challenge: while both governments favor the high-belief, low-tariff regime, the presence of information frictions and the decline of reputation render its attainment and maintenance challenging.

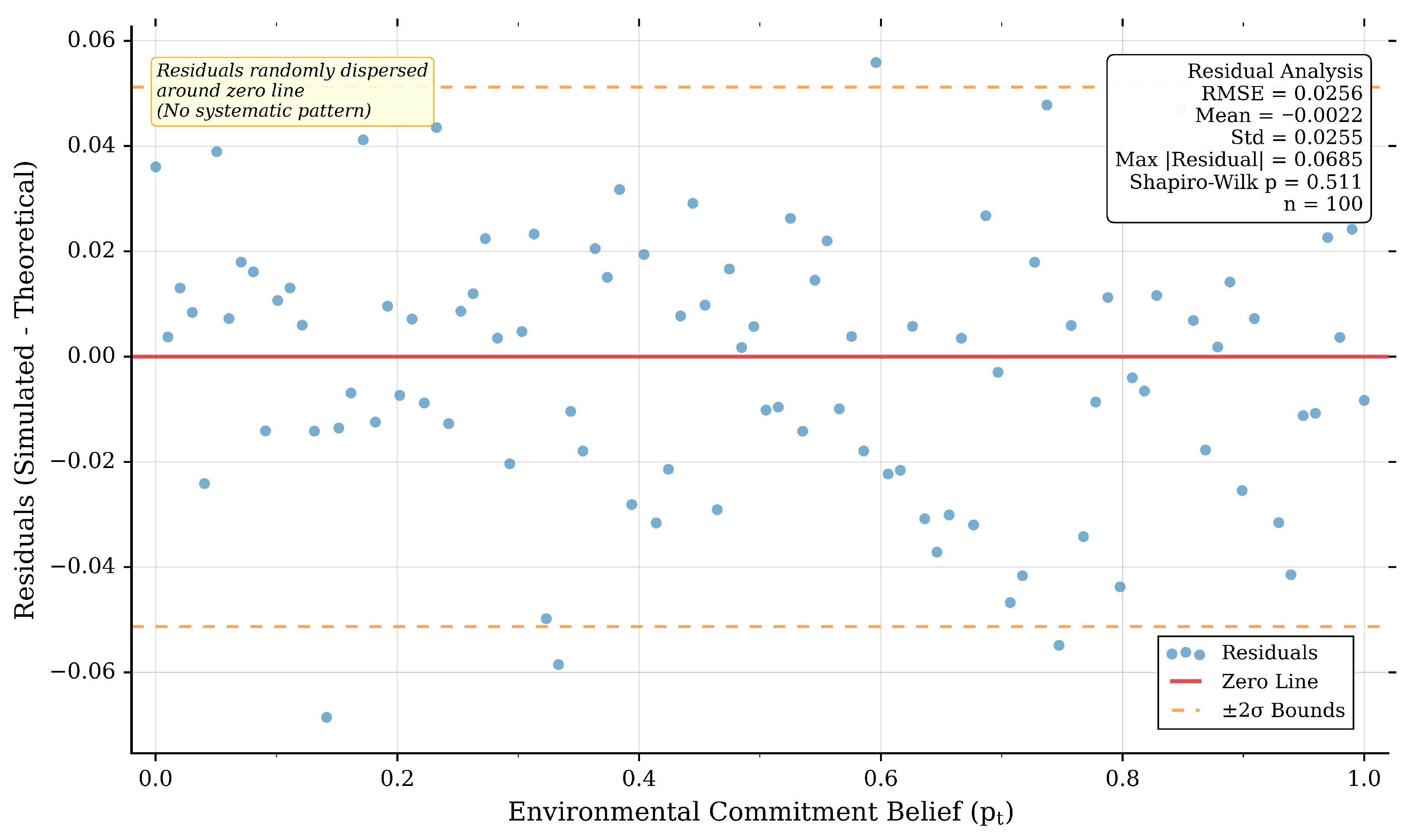

The residual diagnostics presented in

Figure 4 further corroborate the suitability of the model. The simulation-theory residuals are approximately centered around zero, with a standard deviation of 0.0255 and a root mean square error (RMSE) of 0.0256; the maximum absolute residual is measured at 0.0685. The absence of any visible trend or funnel shape in

suggests a lack of systematic bias or heteroskedasticity (constant error variance), and nearly all residual points are contained within the specified envelope

(95% confidence band). The Shapiro–Wilk test does not refute the assumption of normality (

p = 0.511, above the 0.05 threshold for statistical significance), thus supporting the application of standard inferential techniques with respect to the fit. Together,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 demonstrate that the theoretical reaction function accurately describes both the level and curvature of the simulated tariff response throughout the belief domain, while the most significant deviations are observed specifically in the low-belief superlinear zone emphasized by the theory. These findings establish a quantitative link from the equilibrium logic delineated in

Section 2 to subsequent mechanism tests. Notably, the verified curvature, which is pronounced for pessimistic beliefs and diminishes as credibility strengthens, forms the foundation for subsequent analyses:

Belief dynamics under reputation depreciation and cognitive noise;

Induced shifts in firms’ green R&D;

Welfare consequences of information frictions.

5.3. Belief-Driven CBAM Response Function

This section maps out exactly how tariff rates change with trust levels. The relationship is simple: higher trust = lower tariffs, but the effect is non-linear. When trust is very low (below 30%), small trust losses trigger huge tariff jumps. When trust is high (above 70%), further improvements yield diminishing tariff relief. This creates an asymmetry: it is much harder to escape the high-tariff zone than to fall into it—what we call the “credibility trap asymmetry”.

The tariff-trust curve is not a straight line—it is shaped like a cliff. Moving from 20% to 30% trust provides far more tariff relief than moving from 80% to 90% trust. This means reputation-building efforts have vastly different returns depending on where you start. Countries in the low-trust zone face a coordination problem: the steep climb makes initial improvement efforts seem futile, discouraging the very investments needed to escape.

Drawing on the goodness-of-fit evidence presented in

Section 3.2, this subsection delineates the structural correlation between the importer’s perception of commitment credibility and the determination of its optimal carbon-border tariff,

.

Figure 5 illustrates the relationship between

and post-event beliefs

regarding the exporter being of a high-commitment type. The schedule is strictly decreasing across its domain, terminating at endpoints

and

, suggesting a ’credibility reward’: Robust beliefs in continued adherence to green policies endogenously attenuate the CBAM position. A notable inflection occurs around

where

; below this threshold, the curve sharply steepens (indicated by the red segment), denoting a superlinear sensitivity region where minor declines in perceived credibility result in disproportionate increases in tariffs (marked by large

). Conversely, for

, the curve exhibits a flattening response (designated as the “low-sensitivity” regime), whereby incremental improvements in reputation result in diminishing tariff reductions.

From an economic perspective, the curvature captures the importer’s intertemporal trade-off: in situations of low credibility, higher tariffs encompass expected carbon externalities and curb opportunistic subsidy reversals; as credibility enhances, policy maneuvers transition from punitive measures to collaborative efforts, as reduced CBAM rates bolster firms’ motivations to engage in green R&D aimed at diminishing embedded emissions over time. Consequently,

serves as the quantitative nexus between belief dynamics and real economy outcomes: transitioning beliefs from

to 0.3 provides significantly greater tariff relief than an equivalent transition from 0.8 to 0.9, a characteristic leveraged in

Section 3.4,

Section 3.5 and

Section 3.6 for examining reputation building, investment reactions, and welfare.

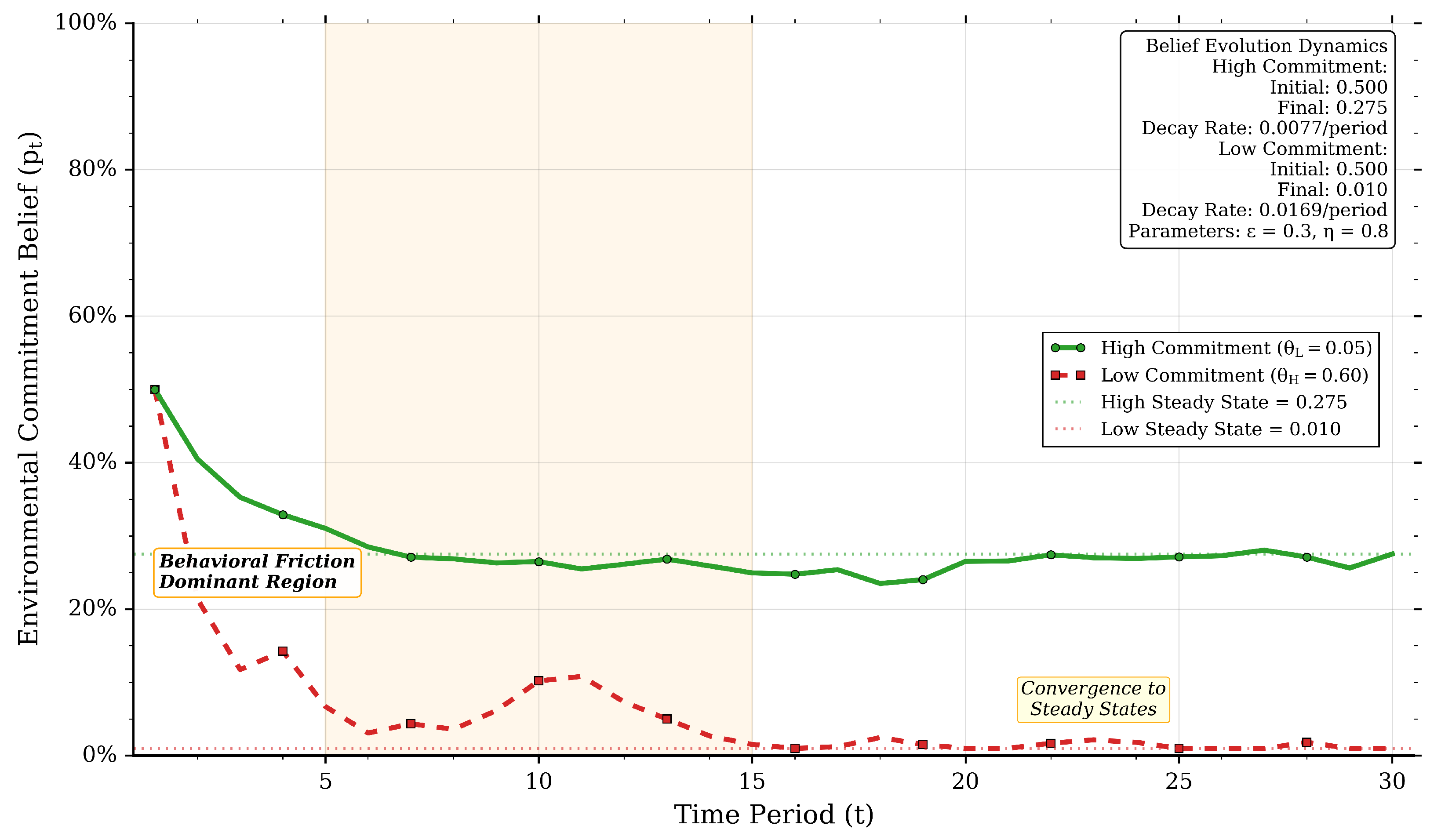

5.4. Belief Evolution and Steady-State Reputation Under Behavioral Frictions

When we add realistic information problems—signal noise (30% misinterpretation rate) and reputation decay (20% per period)—we observe a troubling pattern: even genuinely committed governments cannot maintain high trust. Their reputation naturally erodes to a steady state of just 27.5% belief, firmly in the high-tariff penalty zone. This is the “reputation treadmill”—countries must continuously invest not to build reputation, but merely to offset forgetting. Meanwhile, low-commitment governments quickly fall to near-zero trust within a few periods.

Political memory is short. Like running on a treadmill, sustained effort is required just to stay in place—stop signaling commitment, and reputation decays automatically. Our simulations show that moderate reputation decay (80% retention per period) reduces long-run beliefs by 45% relative to perfect memory. This creates path dependence: early reputation losses become permanent handicaps because the decay mechanism continuously pulls beliefs downward, even when current policies are strong.

Consistent with the reaction function in

Section 3.3, we now examine how beliefs

about the credibility of the exporter’s commitment evolve when the information environment is imperfect.

Figure 6 traces the posterior path of

over 30 periods for a high-commitment government (

) and a low-commitment government (

), starting from maximal uncertainty

. The simulation embeds two calibrated frictions above, cognitive noise in signal interpretation (

, meaning 30% distortion) and reputation depreciation (

, meaning 20% decay per period), and reports fitted decay rates of 0.0077 and 0.0169 per period for the high- and low-type paths, respectively (half-lives 90 vs. 41 periods—the time for reputation to halve). The system converges to different steady states:

(27.5% belief for high-commitment type) and

(1% belief for low-commitment type).

Two features are significant. First, the early “behavioral-friction dominant” window (shaded in the figure) shows that depreciation and cognitive noise jointly overpower the information contained in continuation signals, pulling beliefs down rapidly from 0.5 even for the high type. Second, type separation emerges quickly: frequent terminations by the low-type drive toward the near-zero steady state within a few periods, while the high type settles near 0.275 with small fluctuations around its dotted steady-state line. Hence, despite ongoing positive signals, memory decay imposes a structural ceiling on attainable reputation: capturing a ’reputation treadmill’ in which sustained effort is required only to compensate for forgetting.

These dynamics have direct policy consequences once they are mapped through the tariff schedule

in

Section 3.3. Because

is superlinearly steep for

, both trajectories, especially the steady state of the high type at

, remain in the penalty region of high elasticity. Small adverse shocks to credibility, therefore, generate outsized tariff responses, while incremental reputation gains yield limited relief. This “credibility trap” rationalizes the following:

The clustering of larger theory–simulation deviations at low beliefs documented in

Section 3.2;

The persistence of elevated CBAM rates even when the exporter is genuinely committed to green policies. The next

Section 3.5 quantifies how the two frictions (

,

) amplify investment suppression and welfare losses through this belief–tariff feedback.

Breaking the treadmill requires institutional solutions: legally binding multi-year commitments that cannot be easily reversed, automatic stabilizers that maintain subsidies even during budget crises, or third-party verification systems that reduce signal noise. These mechanisms slow reputation decay and lift the steady-state belief ceiling above the critical 0.3 threshold.

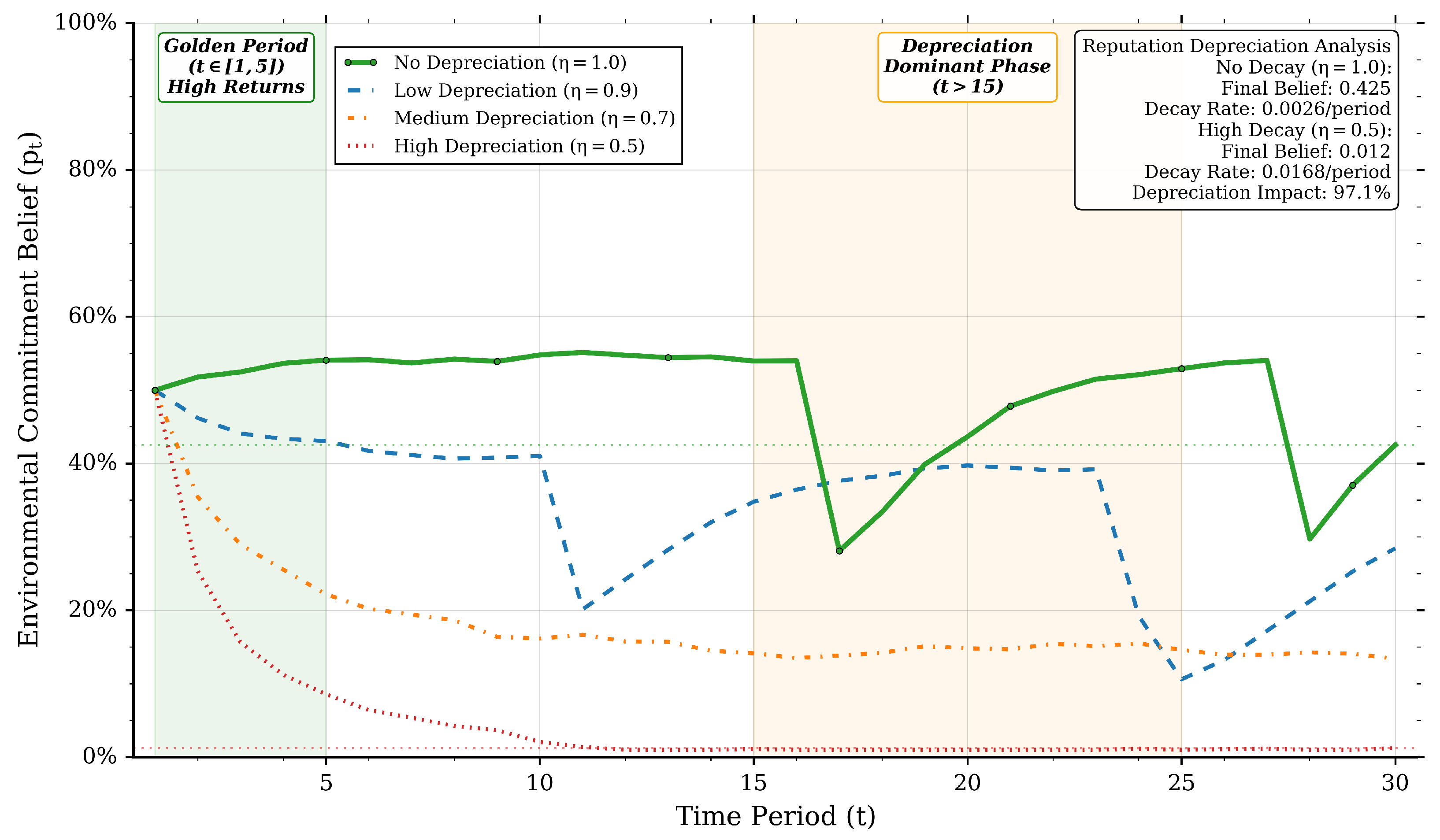

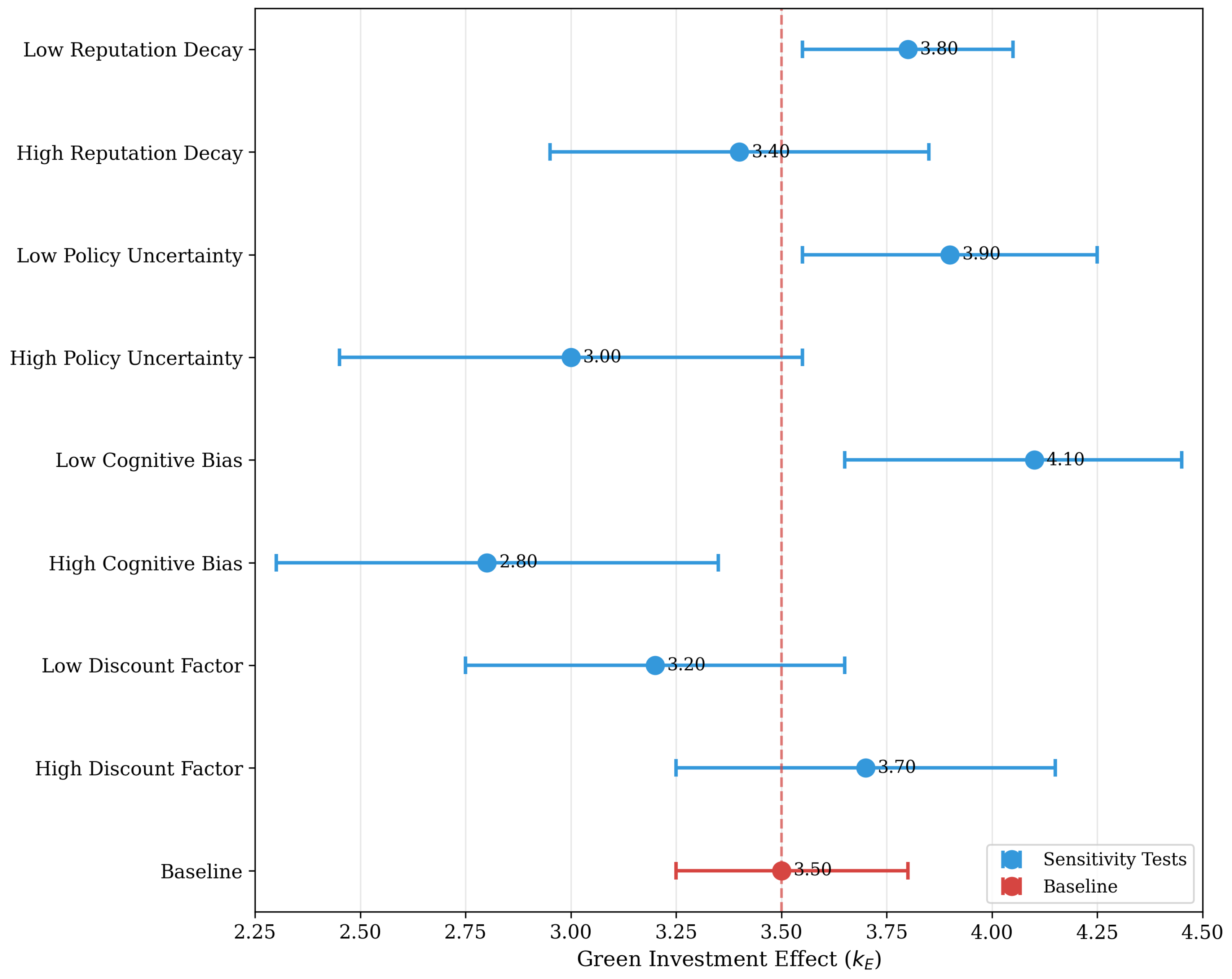

5.5. Behavioral Frictions, Policy Uncertainty, and Green Investment

We now quantify how information frictions damage real investment decisions. High cognitive bias (signal misinterpretation) reduces green R&D by 20%, while high policy uncertainty cuts it by 14%. Reputation decay also matters, reducing investment by 3–9% depending on severity. The mechanism: frictions push beliefs into the high-tariff zone, increasing firms’ expected costs and shortening their planning horizons—discouraging the exact long-term green investments needed to reduce emissions.

Information frictions do not just affect beliefs—they suppress green investment by creating uncertainty. When firms expect high and volatile tariffs (due to low and unstable beliefs), they rationally avoid long-term R&D commitments. Our simulations identify the “golden period” (first five time periods) when credibility-building has highest returns: front-loading transparency and verification during this window yields the greatest investment dividends. After that, reputation decay dominates, and the system enters the treadmill phase.

Having established the belief–tariff mapping

(

Section 3.3) and the belief dynamics under frictions (

Section 3.4), we now quantify how reputation depreciation (

), cognitive bias (

), and policy uncertainty reshaped the belief path and, through

, firms’ green R&D

.

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 report Monte Carlo simulations that maintain the signaling environment fixed while varying

,

, and uncertainty parameters as described in

Section 2.

Figure 7 illustrates

in four different depreciation regimes:

(100%, 90%, 70%, and 50% retention rates). In particular, two primary regimes become apparent as follows:

In the ’golden period’ (green shading), the reputation accumulates quickly when memory is long. With (perfect memory), beliefs increase above 0.5 and stabilize with a slow fitted decay of 0.0026 per period (0.26% decline), reaching a final level of 0.425 (42.5% trust);

Beyond t > 15 (orange shading), depreciation dominates. With (50% retention), beliefs drop to 0.012 with a decay rate of 0.0168 per period—about a 97% reduction relative to the non-decay benchmark—despite continued positive signals. Occasionally, policy interruptions (steps around t = 10 and 25 on the path ) further depress . Because is steep for , medium/high depreciation keeps the system in the superelastic ’penalty’ region for most of the horizon, implying persistently elevated CBAM rates even for intrinsically credible types.

Figure 8 summarizes the induced change in firms’ green R&D (baseline

). Within our parameterization, the greatest marginal effects are associated with information frictions:

High cognitive bias reduces to 2.80 (−20%, representing a one-fifth cut in green investment), while low bias lifts it to 4.10 (+17%);

High policy uncertainty reduces to 3.00 (−14%); low uncertainty raises it to 3.90 (+11%);

Reputation decay matters, but less at the point estimate: high decay yields 3.40 (−3%) whereas low decay provides 3.80 (+9%);

Intertemporal preferences moderately change : a high discount factor (patient firms) increases it to 3.70 (+6%); a low discount factor (impatient firms) lowers it to 3.20 (−9%).

These patterns are consistent with

Section 3.3: frictions that depress

(or make it volatile) push the system into the high-elasticity zone of

, increasing expected tariffs and shortening firms’ effective planning horizon, thereby curbing long-term R&D.

The following two design lessons follow. First, credibility building should be front-loaded during the early high-return window (the “golden period”), e.g., by legislating continuity or publishing verifiable roadmaps, to lift

above the 0.3 threshold where tariff sensitivity eases. Second, transparency instruments that directly reduce

(cognitive bias) and perceived policy uncertainty yield the highest investment dividends—up to 20% gains—while institutions that slow depreciation (raising

through binding commitments) help sustain those gains. These results set up

Section 3.6, where we trace the induced welfare consequences of these frictions through the full policy–investment–tariff feedback loop.

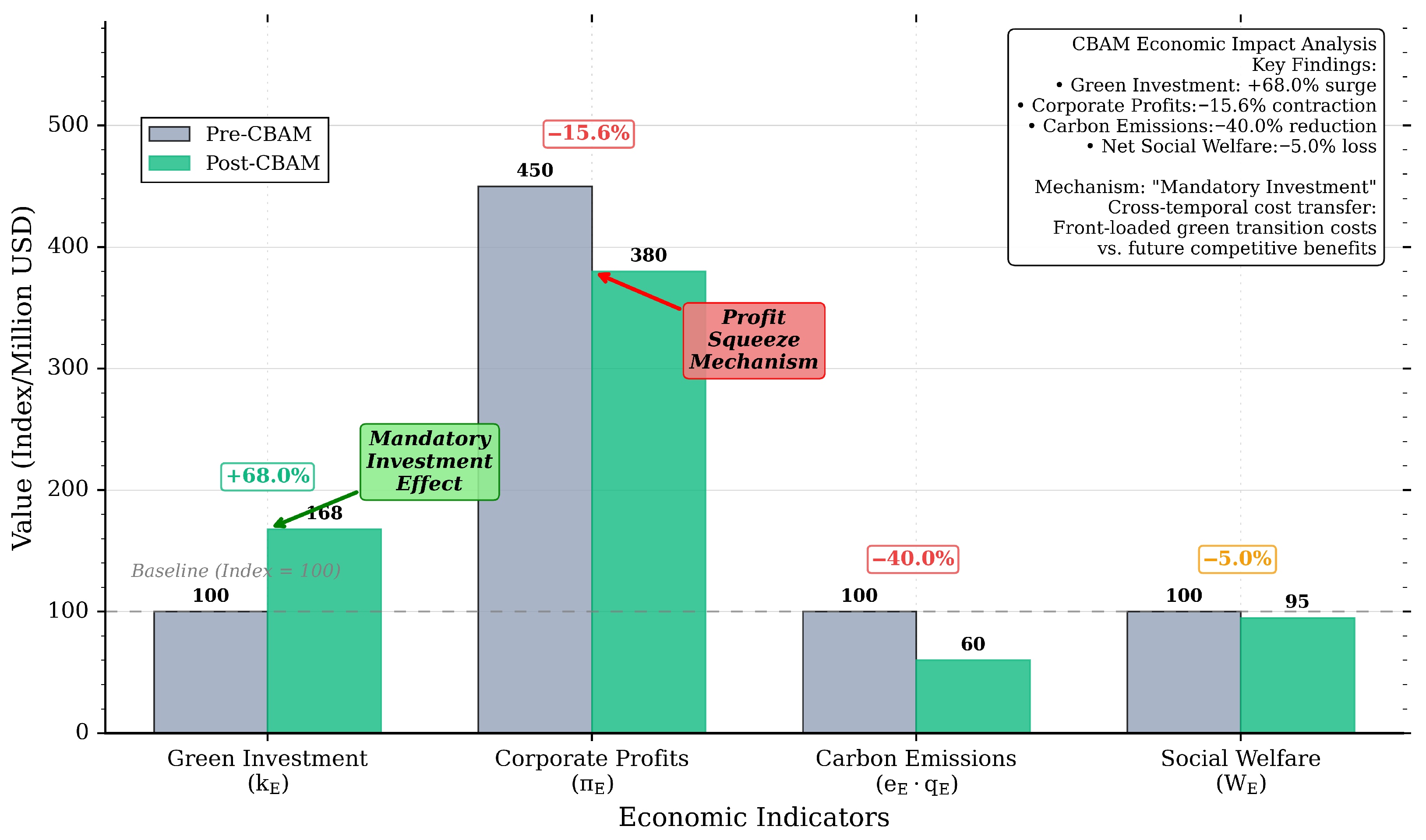

5.6. Macroeconomic Effects of CBAM: Investment Surge, Profit Squeeze, and Welfare Transfer

When CBAM is imposed, exporting countries experience a paradoxical outcome: green investment surges (+68%), emissions plummet (−40%), but corporate profits fall (−15.6%), and overall welfare declines slightly (−5%). This is not a technology problem—it is a timing and credibility problem. Firms must front-load costly investments to avoid punitive tariffs, but cost reductions from learning curves arrive slowly. Meanwhile, they are paying CBAM charges on residual emissions during the transition, and competitive markets prevent full cost pass-through to consumers.

The profit squeeze despite environmental gains reveals the cost of operating in a credibility trap. With perfect information, investment timing would be optimized and unnecessary precautionary tariffs avoided. Instead, pessimistic beliefs keep the system in a high-tariff regime that forces inefficient front-loading: cleaner production, but weaker profitability. This 5% welfare loss (: 100 → 95) represents the expense of the credibility trap, not the cost of green transition per se.

Figure 9 compares the levels before and after CBAM for four main indicators of the exporting economy. In our simulation, CBAM triggers a front-loaded increase in green investment by firms (

, the index increases from 100 to 168, +68%), a contraction of corporate profits (

, from 450 to 380, −15.6%), a substantial reduction in embedded emissions (

from 100 to 60, −40%) and a modest decline in social welfare (

, from 100 to 95, −5%). These patterns are the macro-expression of the micro-mechanics established above.

Two mechanisms dominate. First, a mandatory-investment effect: higher expected tariffs in the super-elastic region of (where ) compel firms to accelerate abatement and efficiency upgrades, lifting despite belief noise and depreciation. Second, a profit squeeze effect: even with improved carbon intensity, firms pay CBAM on residual emissions while facing limited cost pass-through under Cournot competition; transitional sunk costs (R&D, retrofits) arrive before learning curve gains materialize, compressing .

Environmental benefits from lower ;

Output and mark-up losses associated with higher effective marginal costs;

A cross-border welfare transfer, because a portion of compliance costs is converted into tariff revenue accruing abroad when beliefs remain pessimistic and remains elevated. Hence, even for genuinely high-commitment exporters, the credibility trap (steady states near ) can produce cleaner production, but weaker profits and slightly lower national welfare.

What accounts for the occurrence of profit compression despite enhancements in environmental performance? The explanation resides in the temporal discrepancy between incurred costs and realized benefits, situated within the context of belief uncertainty. Green investments necessitate initial front-loading to establish credibility and circumvent punitive tariffs; however, the resultant cost reductions and learning-curve efficiencies from these investments emerge progressively over time. Concurrently, firms incur CBAM charges on residual emissions during the transitional period, while limited pricing power associated with Cournot competition hinders the complete transfer of costs to consumers. The ultimate outcome is characterized by improved environmental production processes, albeit accompanied by diminished short-term profitability.

The trade-off between profitability and environmental considerations is not an unavoidable occurrence; rather, it is indicative of informational friction rather than technological limitation. With comprehensive information, the timing of investments would be synchronized with cost-benefit optimization, and the true commitment type of the exporter would be identifiable, thereby circumventing unnecessary precautionary tariffs. Consequently, the 5% reduction in welfare (: 100 → 95) epitomizes the expense of functioning within a credibility trap, wherein pessimistic beliefs maintain the system in a regime characterized by high tariffs and front-loaded investment.

In terms of policy, the results rationalize a package that emphasizes early credibility building (to push

above the 0.3 threshold where

flattens), transparency instruments that reduce cognitive bias (

), and institutions that slow reputation depreciation (

). By easing belief-driven protectionism, these measures preserve environmental gains while mitigating profit squeeze and limiting net welfare leakage, setting the stage for the welfare decomposition that follows in

Section 5.7.

5.7. Welfare Costs of Incomplete Information: Decomposition and Policy Priorities

This final analysis answers the key policy question: what is the price of information problems? Comparing perfect information (100% welfare) to our friction-filled reality (70% welfare), we find a 30-percentage-point loss. The decomposition reveals priorities: information asymmetry is the biggest culprit (40% of losses), followed by cognitive bias (27%), policy distortion (20%), and reputation maintenance costs (13%). Crucially, most losses stem from how information is processed and remembered, not from environmental ambition differences.

The 30% welfare gap is not destiny—it is a policy target. Unlike fundamental disagreements about climate goals, these information frictions are technically solvable through verifiable disclosure systems, third-party audits, standardized reporting, and legally binding commitments. Our decomposition provides a roadmap: tackle opacity first (40% wedge), then debias beliefs (27% wedge), reform distortionary tariffs (20% wedge), and slow reputation decay (13% wedge). Getting beliefs out of the superelastic zone delivers the largest welfare gains per unit of reform effort.

Building directly on the macroresults in

Section 3.6,

Figure 10 decomposes the welfare gap between a perfect-information benchmark and the realized equilibrium with belief frictions. Starting from a baseline welfare level of 100, the economy settles at 70, implying a total loss of 30 units (30%). The waterfall layout attributes this gap to four sequential components that mirror the mechanisms established earlier: belief-driven tariffs

(

Section 3.3), biased belief dynamics (

Section 3.4 and

Section 3.5), and profit-investment-emissions trade-offs (

Section 3.6).

Information asymmetry (−12; 40% of the gap) is the biggest contributor. When the importer cannot observe the true commitment type of the exporter, pessimistic posteriors keep beliefs

in the superelastic region of

, inflating expected CBAM rates and depressing forward-looking R&D—losses that would vanish if types were known. Cognitive bias (−8; 27%) further widens the gap: noise in signal interpretation (

) systematically pushes beliefs below the

threshold, amplifying tariff responses and shortening firms’ planning horizons. Policy distortion (−6; 20%) captures the loss of efficiency of the importer’s defensive tariff choices relative to the planner’s policy conditional on the same beliefs, i.e., an overreliance on border adjustments when cooperative or credibility-enhancing instruments would produce a higher joint surplus. Finally, reputation maintenance costs (−4; 13%) quantify the fiscal burden of maintaining credibility under depreciation (

): Even high-type governments must continue investing (e.g., subsidies) just to offset natural reputation decay, the reputation treadmill identified in

Section 3.4.

The decomposition yields a clear priority classification for policy design. First, reduce opacity (target the 40% asymmetry wedge) through verifiable disclosure of policy paths and measurable continuity triggers; moving out of the superelastic zone delivers the largest welfare gain per unit of reform. Second, debias belief updating (address the 27% cognitive wedge) through standardized reporting, third-party audits, and rule-based CBAM links to observed performance, which dampens overreaction to noisy signals. Third, limit distortion (20% wedge) by substituting part of the tariff instrument with cooperative tools—mutual recognition of standards, transition contracts—that achieve environmental aims with fewer output and markup losses. Fourth, slow depreciation (13% wedge)—for example, by legislating multi-year commitments or embedding automaticity in support schemes—so that reputation capital erodes more slowly and requires less costly upkeep.

Taken together,

Figure 10 translates the qualitative mechanisms of

Section 3.3,

Section 3.4,

Section 3.5 and

Section 3.6 into a quantitative welfare accounting: most losses arise from how information is processed and remembered, not from environmental ambition per se. Targeted transparency, debiasing, and credibility institutions can therefore preserve the emissions benefits documented in

Section 3.6 while recovering a substantial share of the 30% welfare gap. Similar coordination mechanisms have been successfully implemented in EV charging infrastructure markets using Bayesian potential games to improve global welfare under uncertainty (Zhai et al. [

46]).

6. Discussion

This study conceptualizes the policy commitment capacity of exporting nations as private information. The principal finding is that within the low confidence spectrum of beliefs, the policy reaction function demonstrates ’hyperelasticity’. Subtle variations in these beliefs induce non-linear escalation of border adjustment intensity, thereby establishing a distinct structural trade-off between investment, profits, and emission reductions. This mechanism offers a comprehensive framework to elucidate the empirical phenomenon where ’policy intensity is highly sensitive to information quality’, concurrently relating micro-level signaling games to macro-level welfare outcomes.

In contrast to the prevalent studies on carbon leakage and industrial competitiveness [

47,

48,

49], our framework underscores the primary significance of belief dynamics in influencing policy efficacy. Contemporary analyses frequently conceptualize border adjustments as static tax systems, evaluating their impacts on emission reduction and output within deterministic frameworks. Research on carbon leakage under incomplete regulation [

47] and trade-embodied emissions [

48] demonstrates the complex interaction between environmental policy and international trade. The potential for free trade agreements to either mitigate or exacerbate carbon leakage [

50] adds another layer of complexity to policy design. Recent analyses of CBAM impacts on developing countries [

51] highlight the equity–ambition trade-offs inherent in border adjustment mechanisms. Conversely, we demonstrate that when beliefs undergo continuous fluctuations due to noise (

) and a loss of credibility (

), the ’optimal response’ to border adjustments manifests a pronounced curvature within low-belief intervals. This intensifies the transmission of policy uncertainty to corporate decision-making processes. This aspect is of particular importance compared to the work of Monjon & Quirion [

52], who highlighted the trade-off between border adjustment and output-based quotas in managing leakage versus sustaining output. We further elucidate that the relative advantages of combining these policy instruments alter with varying belief states when belief friction is present, thereby necessitating ’belief conditional’ hybrid designs and trigger rules. This hyperelasticity driven by belief also elevates the importance of ’credibility maintenance’ to a pivotal resource allocation issue. In scenarios where importers exhibit high sensitivity to regulatory changes or experience rapid erosion of natural credibility (high

), it becomes imperative that exporters continually invest in verifiable commitments and transparency-building measures to prevent beliefs from entering the hyperelastic zone and provoking excessive policy stringency.

The alignment of our findings with contemporary policy practices in climate trade governance is evident. The design of the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) incorporates provisions for “equivalent carbon pricing” that permit exporting nations to receive credit for domestic carbon taxation [