1. Introduction

Climate change and environmental issues have emerged as critical challenges for humanity. The rapid acceleration of industrialization and urbanization has significantly increased greenhouse gas emissions, particularly carbon dioxide (CO

2), leading to global warming and extreme climate variations. These changes have resulted in severe consequences, including ecosystem disruption, rising sea levels, and an increase in the frequency of natural disasters, all of which pose direct threats to human survival [

1,

2,

3].

To address these challenges, the International Energy Agency (IEA) has proposed the “Net Zero by 2050” initiative, which aims to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 and limit the global temperature increase to within 1.5 °C [

4]. One such strategy, Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage/Utilization (BECCS/U), has garnered attention for its potential to both reduce atmospheric CO

2 and enhance biomass-based productivity in agricultural field [

5,

6]. Within this framework, the use of CO

2 enrichment in controlled environments-such as smart farms-offers a promising pathway to simultaneously promote plant growth and sequester carbon, making it highly relevant for sustainable agriculture and climate mitigation.

Photosynthesis, a vital process for plant growth and development, involves the absorption of CO

2 and the synthesis of carbohydrates. Numerous studies have sought to optimize photosynthesis by considering environmental conditions and various stages of plant growth. For example, Bhargava et al. [

7] examined the effects of CO

2 concentration and light intensity on plant nutrition, while Chen et al. [

8] optimized environmental factors such as temperature and illumination to enhance growth rates. Additionally, Jung et al. [

9] developed a model to analyze the environmental factors influencing photosynthesis in Romaine lettuce. However, these studies often relied on traditional analytical methods, which struggled to account for the variability inherent in plant growth data.

Recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) have provided more robust tools for addressing variability in photosynthesis predictions. Ying et al. [

10] developed a deep neural network (DNN) to predict photosynthetic rates based on light intensity, CO

2 concentration, and temperature. Zhang et al. [

11] employed machine learning models, such as XGBoost (eXtreme Gradient Boosting) and support vector machines (SVMs), using tabular data (e.g., leaf area, length, and width) to forecast photosynthesis rates. While effective, these approaches were limited to structured data formats and single-crop predictions. Kaneko et al. [

12] introduced a hybrid artificial neural network (ANN) model by preprocessing environmental data and integrating it with plant-specific information. Meanwhile, Niu et al. [

13] utilized a backpropagation neural network (BPNN) model optimized with the Incremental Constructive Extreme Learning Machine (IELM) for photosynthesis prediction. Additionally, Zhang et al. [

14] combined particle swarm optimization with DNNs to create a PSO-BP model for predicting photosynthesis rates based on fluorescence properties and environmental factors. However, significant limitations persist. Current models struggle to generalize across various crops, and most studies overlook image data, which has considerable potential for capturing growth variability and enhancing prediction accuracy.

To overcome these challenges, this study proposes a hybrid deep learning framework that integrates structured environmental data (e.g., CO

2 concentration, light conditions, temperature) with unstructured image data to predict short-term CO

2 uptake and release dynamics. Unlike existing approaches that focus solely on single crops or tabular inputs, this study generalizes to five leafy vegetables and leverages both visual and environmental cues. Combining CNN and YOLOv11-based image segmentation, it extracts plant-specific features (e.g., size, shape, and color patterns) and combines these with sensor data to generate accurate and time-resolved CO

2 dynamics predictions (

Figure 1). Importantly, this prediction model is extended to evaluate operational impacts, specifically water use efficiency and yield responses, under various CO

2 control strategies. This step is crucial in indoor agricultural systems, where irrigation and pumping are energy-intensive. The analysis in the present study suggests that optimizing CO

2 concentration can simultaneously reduce water use and increase crop yields, contributing to energy savings and sustainable crop production. By linking computer vision, sensor fusion, and plant physiology, this research highlights the role of proximity remote sensing as a scalable tool for monitoring and optimizing CO

2-related processes in smart agricultural settings.

2. Materials and Methods

This section describes the methodology for quantifying CO2 absorption and emission during the photosynthetic and respiratory processes of five leafy vegetable species. A deep learning model was utilized to predict the optimal CO2 concentration at each growth stage, with the goal of maximizing photosynthetic efficiency and productivity. Additionally, the study investigates variations in crop yield in response to changes in water consumption, employing evapotranspiration models.

2.1. Material Preparation and Characterization

The leafy vegetable species selected for this study were red skirt lettuce Lactuca sativa L. var. crispa ‘Red Skirt’), green skirt lettuce (L. sativa L. var. crispa ‘Green Skirt’), lettuce red (L. sativa L. var. acephala ‘Lettuce Red’), bok choy (Brassica rapa L. subsp. chinensis ‘Bok Choy’), and romaine lettuce (L. sativa L. var. longifolia ‘Romaine’) all obtained from ASIA SEED Co. (Seoul, Korea) These species were selected to represent two major families in leafy green production, Asteraceae (Lactuca spp.) and Brassicaceae (Brassica rapa), and to include varieties with different leaf pigmentation. All selected species utilize the C3 photosynthetic pathway. A high-purity CO2 gas (99.999%, KyungDong Gas, Busan, Korea) was used to regulate CO2 concentration within enclosed chambers. Seedlings were grown hydroponically for 21 days post-germination. For the experiment, plants were transplanted into the experimental chamber when they had developed 5–6 true leaves. This point of transplanting was designated as Day 1 of the experiment. Environmental conditions were continuously monitored using CO2 and temperature sensors. Additionally, high-resolution images of the plants were captured to document growth patterns and morphological changes over time. The camera used for this experiment was a Samsung S5KHM3 (Samsung Electronics, Suwon, Korea), with a resolution of 108 megapixels and an aperture of f/1.8. A single camera was used throughout the entire imaging process. A single camera was employed throughout the entire imaging process and was positioned at the center of the top surface of the chamber. During image capture, the lighting provided by the LED grow lights, which were used for plant growth, served as the only light source, ensuring consistency with the growth conditions.

2.2. Experimental Method

The selected plant species were cultivated in a hydroponic system under controlled environmental conditions (25–30 °C, 60–70% relative humidity). Following germination, the plants were exposed to 100 W·m

−2 LED lighting to promote growth. To ensure consistent nutrient availability, the hydroponic solution was replenished every three days. The experimental setup for measuring CO

2 concentration is illustrated in

Figure 2. It is important to note that the CO

2 chamber used in this study was designed with fully opaque black walls and external blackout curtains to completely eliminate incidental light during both the LED-illuminated phase and the dark phase. Because this light-shielding structure prevents interior photographs from capturing the chamber layout or sensor configuration, real images do not provide meaningful technical information; therefore, a schematic representation is provided instead.

Figure 2 presents a detailed schematic that clearly illustrates the internal configuration of the enclosed chamber, including the CO

2 inlet for concentration control, the environmental control unit, the arrangement of LED modules that define illumination conditions, the overhead camera mount, and the placement of CO

2 and temperature sensors.

For the CO2 absorption experiment, eight plants of the same species were placed in a sealed chamber, with external air introduced to stabilize temperature and CO2 levels. The CO2 concentration inside the chamber was initially elevated to 1200 ppm. Photosynthetic activity was then stimulated by activating the light source, and CO2 absorption was monitored until the concentration decreased to 400 ppm. Immediately following the absorption phase, a CO2 emission experiment was conducted. During this phase, the light source was turned off, and blackout curtains were employed to create a dark environment, simulating nighttime conditions and facilitating plant respiration. CO2 emissions were measured until the concentration returned to 1200 ppm. This rapid cycling protocol was designed to efficiently generate a dynamic dataset for model training. A total of five consecutive cycles were performed over a 24 h period for each measurement day. The CO2 concentration curves presented in the results represent the data from a single, representative cycle performed after an initial stabilization period, rather than an average of multiple cycles. Images were captured once per measurement cycle. Specifically, images were taken at the beginning of each light phase, when the CO2 concentration was at 1200 ppm, to correlate the plant’s morphological state with the subsequent CO2 absorption dynamics. Quantitative data on leaf area and color changes were extracted from the images and analyzed for correlations with CO2 absorption and emission rates. Furthermore, it is crucial to clarify that the CO2 exchange data represent the total values for the entire plant biomass in the chamber and are not normalized by leaf area. As the quantitative leaf area data were not systematically recorded, direct comparisons of the magnitude of CO2 uptake between species should be made with caution, as they are influenced by the overall plant size. This reveals rich and dynamic CO2 patterns, which are primarily used to train and validate deep learning prediction models.

2.3. Methodology for Hybrid Prediction Model

A predictive model for CO

2 absorption in crops was developed by integrating tabular data with the output of a hybrid deep learning model that combines ResNet50 and YOLOv11. The model was implemented in Python 3.9, a widely adopted language in machine learning research due to its extensive ecosystem of optimized libraries (TensorFlow 2.10, Keras 2.10, Scikit-learn for deep learning 1.2; NumPy 1.23, SciPy 1.10 for numerical computation) and robust GPU acceleration support through CUDA 11.8 integration. Python’s interpretability and rapid prototyping capabilities facilitated iterative model development and hyperparameter tuning. The implementation utilized an NVIDIA RTX 3090 4-way Ti GPU cluster for accelerated training and inference. Key machine learning and deep learning frameworks, including TensorFlow 2.10, Keras 2.10, Scikit-learn 1.2, and Ultralytics 8.0 [

15] were employed in the model development process.

The dataset used for training consisted of image data obtained from CO

2 absorption experiments. The training dataset consisted of 225 original images collected from five crop species at three growth stages: Days 1, 6, and 10 post-transplanting (DPT). Images were captured at 1050 × 1400 × 3 pixel resolution under CO

2 concentrations of 400–1200 ppm. Data augmentation (rotation ±20°, flips, spatial translations) was applied with an augmentation factor of 298×, yielding 67,050 total images. The dataset was split into training (70%, 46,935 images), validation (15%, 10,057 images), and test (15%, 10,058 images) sets. During the data preprocessing stage, data augmentation techniques were applied [

16]. In this process, various transformations were implemented while ensuring that the modifications did not extend beyond the original crop images. Specifically, rotation within a 20° range, vertical and horizontal flipping, and slight positional shifts in all directions were applied. Through data augmentation, the dataset size was increased by a factor of 298. Before training, data augmentation techniques were applied to enhance the model’s robustness. The dataset was then divided into training, validation, and test sets in a 7:1.5:1.5 ratio to ensure a balanced evaluation of the model [

17].

2.3.1. YOLOv11 Transfer Learning

To enable automated crop recognition and physical feature extraction, the YOLOv11 instance segmentation model was adapted through transfer learning. The model was initialized with weights pretrained on the COCO dataset (80 object categories) [

18], providing robust low-level feature detection (edges, textures, shapes) that generalizes across visual domains. Fine-tuning specialized the model for five crop species (RSL, GSL, LR, BC, RL) using selective layer freezing: backbone convolutional layers retained COCO-learned weights for general feature extraction, while detection and segmentation heads were retrained on crop-specific data to learn species-distinctive characteristics. Training employed stochastic gradient descent (momentum = 0.9) with initial learning rate 0.01 (cosine annealing decay), batch size 16, converging after approximately 100–150 epochs. The fine-tuned model outputs instance segmentation masks for each crop, enabling extraction of physical features: leaf area (cm

2), plant count, red pigmentation ratio (%), and green pigmentation ratio (%). These metrics quantify biomass and physiological characteristics directly related to photosynthetic capacity.

2.3.2. Hybrid Neural Network Architecture for CO2 Prediction

The CO

2 prediction model integrates three distinct data streams through a fully connected neural network architecture (schematically illustrated in

Figure 1; detailed architecture in

Figure 3). The first stream consists of physical features extracted from YOLOv11, comprising four quantitative metrics: leaf area, plant count, red pigmentation ratio, and green pigmentation ratio. These features explicitly characterize crop biomass and chlorophyll content. The second stream incorporates hierarchical visual features from ResNet50, a convolutional neural network pretrained on ImageNet. Feature maps are extracted from the final convolutional layer, yielding 2048-dimensional representations that encode complex visual patterns such as leaf texture, plant architecture, and subtle color variations not explicitly quantifiable through simple metrics. The third stream captures tabular environmental data through seven features: CO

2 concentration (ppm), temperature (°C), light status (binary: dark or illuminated), and crop species identity (one-hot encoded across five categories). The concatenated input vector of 2059 dimensions is processed through three sequential fully connected layers with 512, 256, and 128 nodes, respectively, each employing ReLU activation and dropout regularization (rate = 0.3) for the first two layers. The final output layer consists of a single node with linear activation to predict chamber CO

2 concentration change (ppm). Model training employed the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.001 and exponential decay, minimizing mean squared error loss with a batch size of 32, which was selected through optimization trials comparing batch sizes of 16, 32, and 64. Early stopping with 300-epoch patience was implemented, ultimately selecting model weights from epoch 100 where validation loss reached its minimum (0.95 ppm MAE). This architecture leverages complementary information: explicit physical measurements provide interpretable features directly linked to photosynthetic processes, while deep visual features capture subtle growth-stage cues that enhance prediction robustness across different crop species and developmental stages.

2.3.3. Model Training and Performance Evaluation

To quantify the model’s predictive accuracy, Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Mean Squared Error (MSE) were employed as the primary evaluation metrics. MAE measures the average magnitude of the errors between predicted and observed values, while MSE gives higher weight to larger errors. MSE was used as the loss function to guide model optimization during training, and MAE was used to assess the final validation performance. The metrics are defined in Equations (1) and (2), where

and

represent the predicted and observed values, respectively, and n is the total number of samples.

2.4. Analysis of Water Consumption, Energy Use, and Relative Yield

To analyze the impact of CO2 enrichment on resource efficiency, crop evapotranspiration, associated energy consumption, and relative changes in crop yield were estimated.

2.4.1. Evapotranspiration and Water Consumption Modeling

Evapotranspiration (

ET) was estimated using the Stanghellini models, as described in Equation (3) [

19]. These models are particularly suited for enclosed environments, such as greenhouses, rather than open-field conditions [

20]. The specific input parameters and environmental conditions used for the Stanghellini equation are detailed in

Table 1.

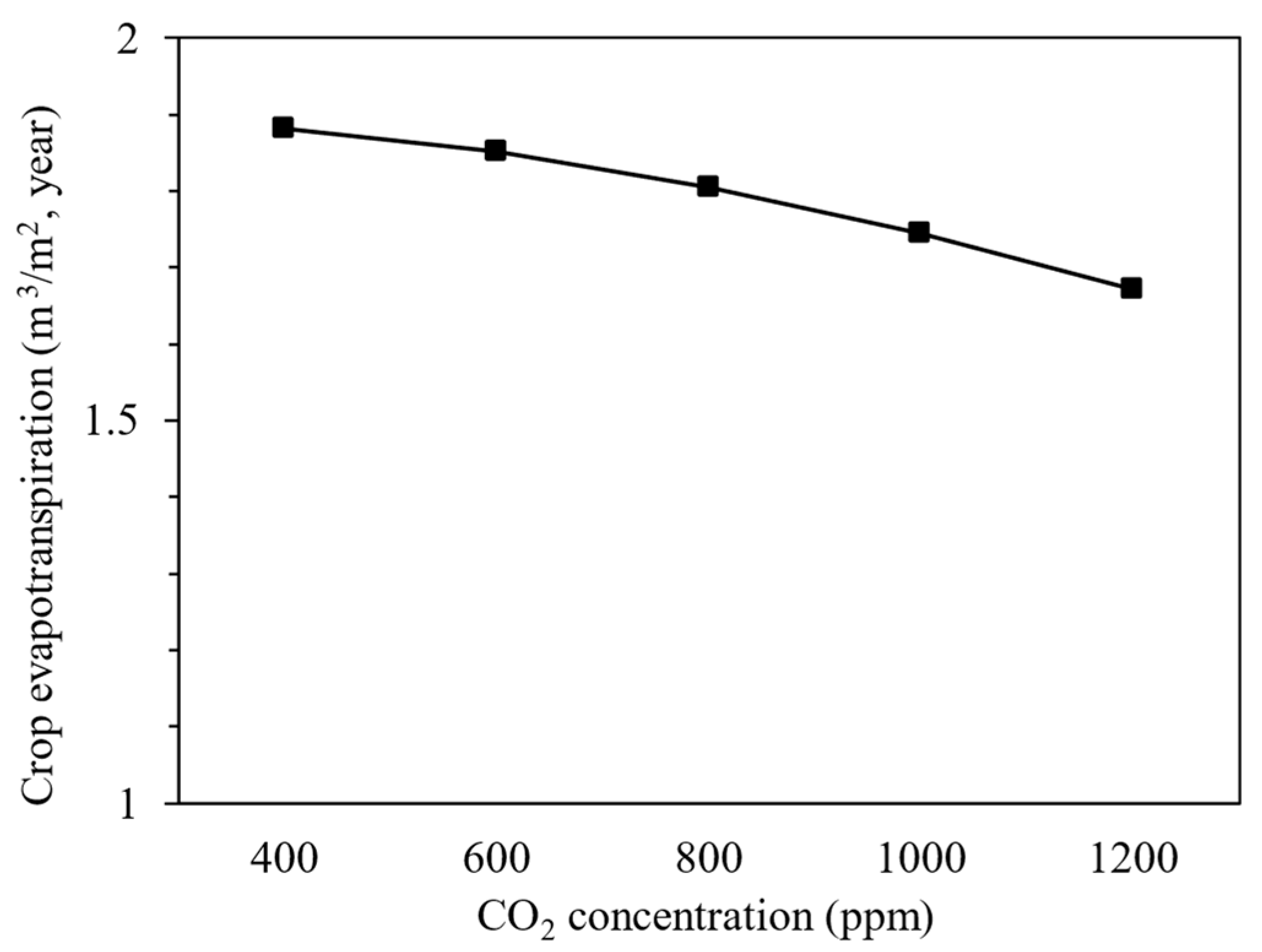

The internal crop resistance is a critical factor in ET estimation, as it varies directly with CO2 concentration levels. To investigate the effect of CO2 uptake on evapotranspiration, CO2 concentrations were varied from 400 ppm to 1200 ppm for analysis.

Evapotranspiration flux (ET) is expressed in [W m

−2], representing the rate of water vapor transfer from the crop surface to the atmosphere. The parameter

δ represents the slope of the saturation curve of the psychrometric chart, expressed in [Pa °C

−1]. Similarly,

Rn denotes the net radiation, given in [W m

−2]. The leaf area index (LAI) is a dimensionless parameter that quantifies the leaf surface area per unit ground area, influencing transpiration and photosynthesis rates. In this study, LAI was fixed at 4.4 because the objective was to isolate the physiological effect of CO

2 induced changes in internal crop resistance (

ri). Since LAI was not measured dynamically, and varying it without measured data could introduce structural errors. Since the immediate response of C3 plants to elevated CO

2 is stomatal closure reducing transpiration, fixing LAI allowed the analysis to focus on the CO

2–

ri relationship. The parameters

ρa and

Ca represent the air density [kg m

−3] and the specific heat capacity of air [J kg

−1 °C

−1], respectively. The vapor pressure deficit (VPD) is expressed in [Pa], while the psychometric constant (

γ) is given in [Pa °C

−1]. The internal crop resistance and external crop resistance (

re) are both measured in [s m

−1]. The internal leaf resistance can be approximated using the microclimate parameters of the greenhouse by applying Stanghellini’s equation, as presented in Equation (4).

The parameters influencing include , the minimum internal resistance; [W m−2] the solar radiation; [°C], the leaf surface temperature; , the CO2 concentration; and and [kPa], which represent the saturation vapor pressure and actual vapor pressure, respectively.

is a key parameter in this study and its effect on internal resistance is described by Equation (5).

In this study, the parameter

and the minimum internal resistance (

) are adopted from Stanghellini’s research, as presented in

Table 2.

By calculating Equation (3) using the derived parameters, the crop’s evapotranspiration can be estimated, enabling the quantification of water consumption during the growth period. Additionally, leaf conductance is defined as the reciprocal of internal resistance ().

2.4.2. Energy Consumption Modeling

To quantify the energy savings from reduced water consumption, the power required for groundwater pumping was calculated using Equation (6), as agricultural water in Korea primarily relies on groundwater.

The parameters used in this equation are summarized in

Table 3.

2.4.3. Relative Yield Estimation

It is important to clarify that the yield values presented in this study were not obtained from direct physical harvesting of the crops. Instead, they are simulated estimates of relative yield changes, calculated using the empirical model as shown in Equation (7) [

21]. This model predicts that a decrease in leaf conductance, the reciprocal of internal resistance, reduces the uptake of airborne pollutants through stomata, which can lead to improvements in yield. Specifically, when leaf conductance decreases by x%, the absorption of pollutants, such as ozone (O

3) and sulfur dioxide (SO

2), both measured in ppm, into leaf tissues also decreases by x%. To quantify the impact of pollutant absorption on crop yield, the following predictive models were used [

21]. To reflect conditions in Korea, average O

3 and SO

2 concentrations of 0.09 ppm and 0.008 ppm, respectively, were applied in the model based on monitoring data from Air Korea [

22,

23].

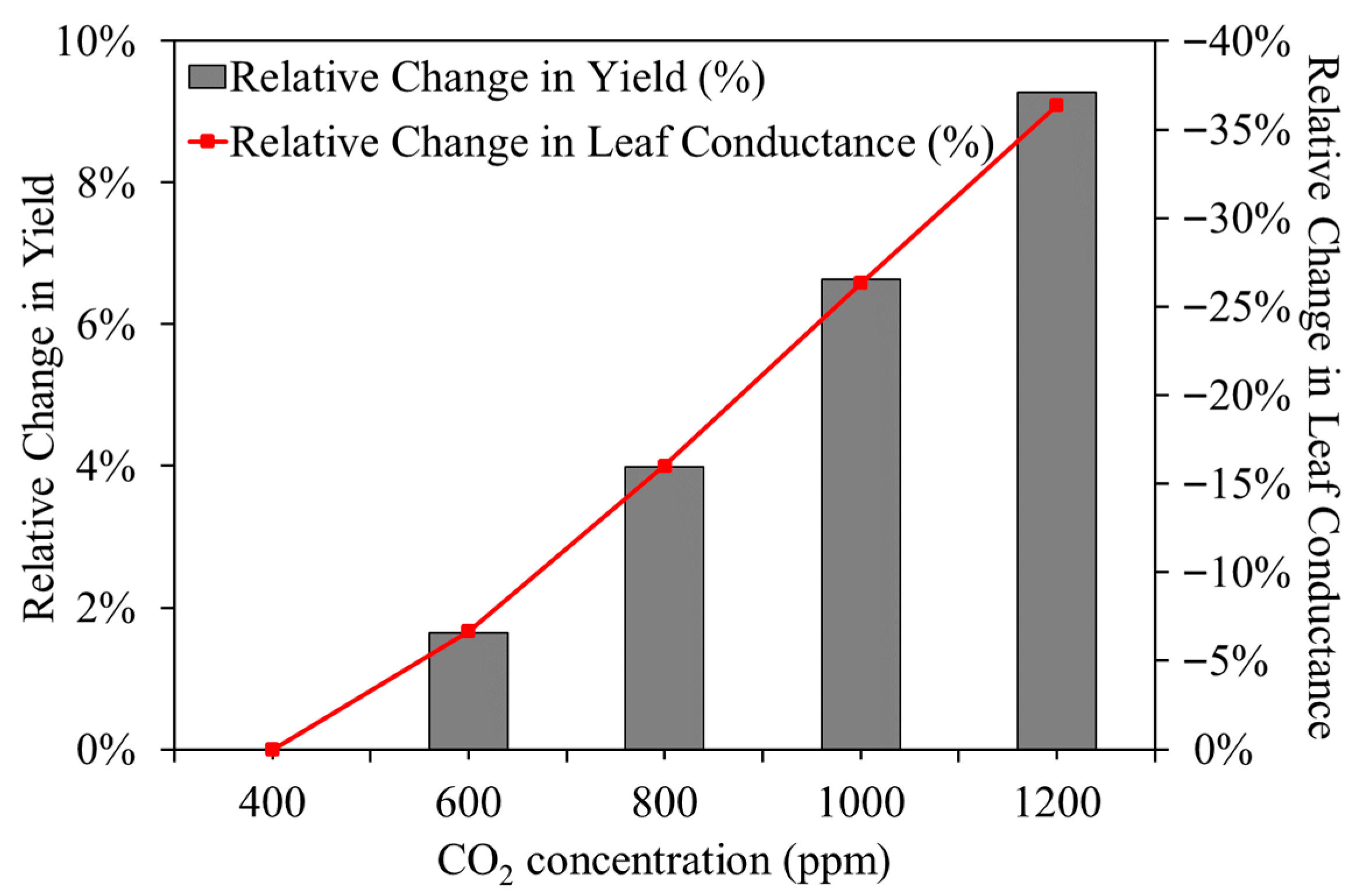

To analyze the effects of varying CO

2 concentrations, internal leaf resistance was calculated for CO

2 levels ranging from 400 to 1200 ppm. As CO

2 concentrations increased, internal leaf resistance also rose, while its reciprocal, leaf conductance, decreased. The reduction in leaf conductance at CO

2 concentrations of 600, 800, 1000, and 1200 ppm, relative to the baseline of 400 ppm, was computed using Equations (2) and (3). The average decline in leaf conductance across these conditions was subsequently utilized to estimate potential yield increases. While the empirical model has been extensively validated in greenhouse agriculture with typical accuracy of ±10–15%, our specific predictions require confirmation through controlled cultivation trials [

21]. We propose a randomized complete block design with three treatments replicated across 3–5 growth cycles comparing ambient CO

2 (~400 ppm), fixed enrichment (1200 ppm), and variable enrichment (1000–1100 ppm during early growth, 1150–1200 ppm during late growth). Direct measurements should include fresh weight at harvest to validate the 9.3% yield increase, cumulative water consumption to validate 11.1% savings, total energy costs, and temporal LAI dynamics. Statistical validation via ANOVA with α = 0.05 significance threshold would compare treatment effects. Trials should be conducted in operational smart farms to assess real-world performance under spatial heterogeneity and environmental fluctuations, quantifying return on investment and identifying any deviations from model predictions.

3. Results and Discussion

This study investigates the effects of CO2 concentration on the growth characteristics, water consumption, and CO2 absorption of five leafy vegetable species cultivated under smart farming conditions in Korea. Experiments were conducted in a sealed chamber with CO2 concentrations ranging from 400 to 1200 ppm. Based on the collected experimental data, a hybrid CNN model was developed to predict the CO2 absorption and emission rates of the crops. Additionally, the study presents a system-level analysis of crop growth, water consumption, and CO2 utilization using this predictive model.

3.1. Experimental Analysis of CO2 Concentration Changes

To investigate the relationship between CO

2 concentration and crop physiology, variations in CO

2 absorption and emission were analyzed at different time points post-transplanting. The experiment considered key environmental factors, including CO

2 concentration, temperature, light availability, crop species, and leaf characteristics.

Figure 4 illustrates the CO

2 concentration dynamics for five crop species during a representative measurement cycle, showing rapid absorption in the light phase and subsequent emission in the dark phase. A key observation is that the total CO

2 respired during the dark phase nearly equaled the amount assimilated during the light phase. It is important to note that this near-zero net carbon gain observed within a single cycle is a limitation of the short-cycle experimental design, which was specifically designed to generate model training data, and should not be interpreted as the plant’s overall carbon balance under a typical diurnal growth cycle.

Figure 5 presents the CO

2 absorption dynamics for the five crop species, measured at DPT 1, 6, and 10 to examine temporal variations in photosynthetic activity. The data represent the change in absolute CO

2 concentration within the chamber and is not normalized by leaf area. For green skirt lettuce and romaine lettuce (

Figure 5a,b), the rate of CO

2 absorption markedly increased from DPT 1 to DPT 10. This trend provides strong qualitative evidence that as the plants developed, their total leaf area expanded, thereby enhancing their overall photosynthetic capacity, even though the specific leaf area was not quantified. In contrast, for bok choy (

Figure 5c), the CO

2 absorption trend remained similar between Day 6 and Day 10. This plateau effect was likely attributed to growth saturation, suggesting that by Day 6, the plant’s leaf area had reached a point where further expansion was limited, causing CO

2 absorption rates to stabilize.

The red-pigmented species, red skirt lettuce and lettuce red (

Figure 5d,e), exhibited different characteristics. To investigate the impact of pigmentation, we analyzed the proportion of red-pigmented areas using the image segmentation capabilities of our model, with the results presented in

Figure 6 [

24].For red skirt lettuce (

Figure 6a), the proportion of red pigmentation increased from 2.8% at Day 1 to 38.2% at Day 10, which correlated with a slowdown in CO

2 absorption between Day 6 and Day 10. Conversely, for lettuce red (

Figure 6b), red pigmentation increased to 41.4% by Day 10, while CO

2 absorption continued to rise throughout the period. These differing trends suggest a complex relationship between anthocyanin accumulation (red pigmentation) and photosynthetic activity that may be species-specific.

3.2. Performance of the Trained Model

This study proposes a model for predicting CO

2 concentration in crops by integrating the outputs of a hybrid CNN model with tabular data. The hybrid model combines YOLOv11 and ResNet50 to improve prediction accuracy. The crop image data collected during the experiments were used to fine-tune YOLOv11, an instance segmentation model. The trained model effectively identified and highlighted the research crops, including green skirt lettuce, romaine lettuce, bok choy, red skirt lettuce, and lettuce red (

Figure 7). The features extracted from the segmented masks, such as crop size and color ratio, served as input variables for the predictive model.

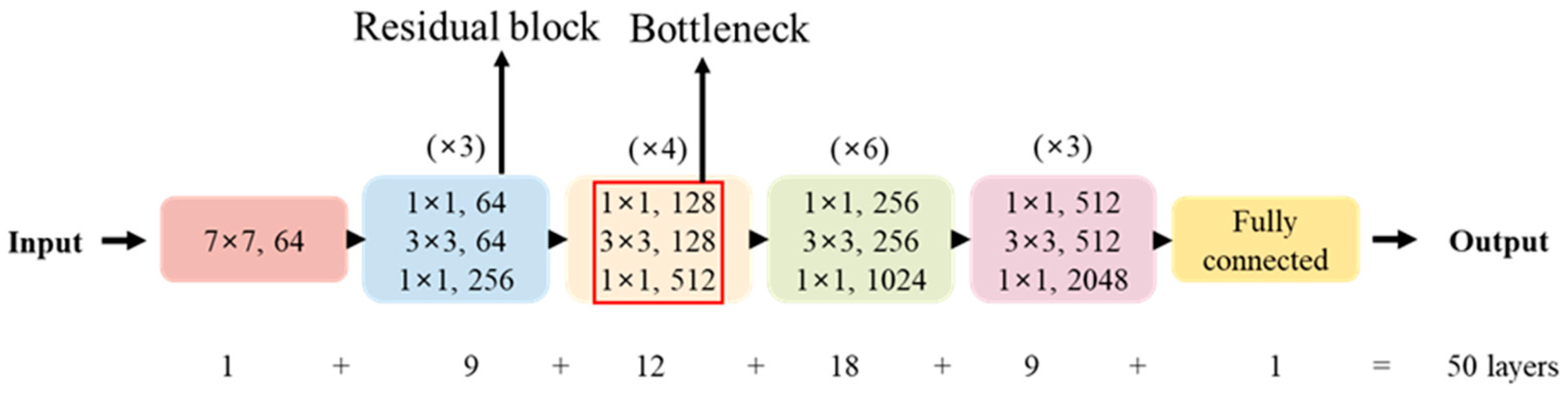

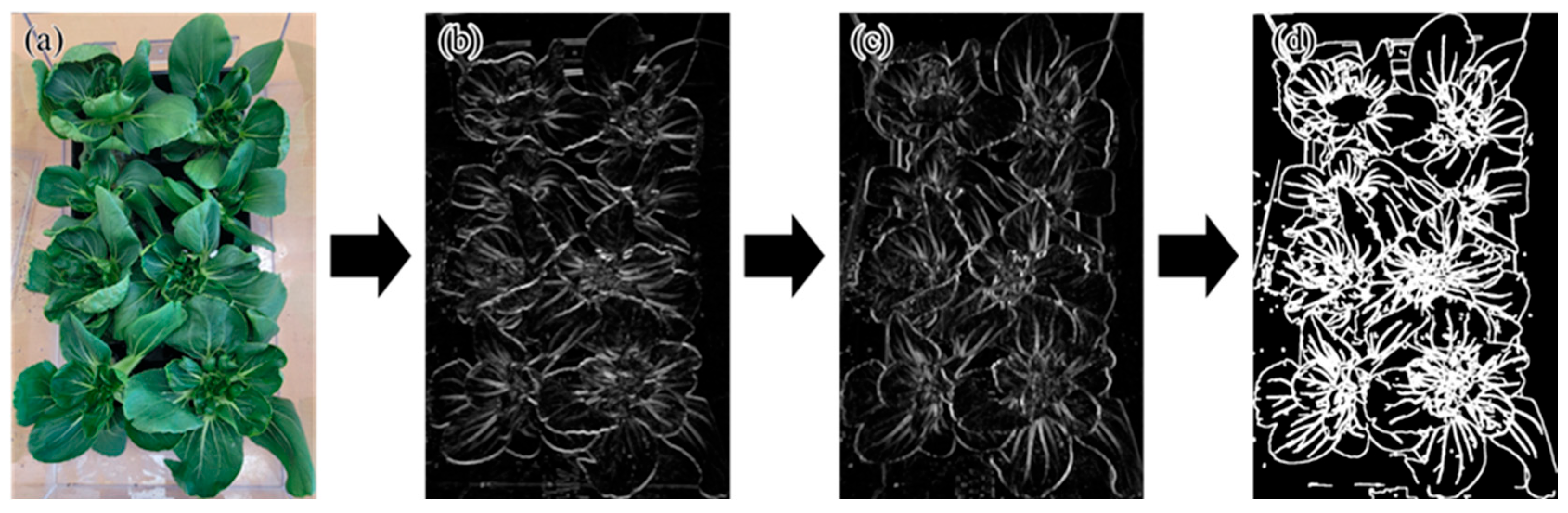

Additionally, ResNet50, a deep neural network comprising 50 layers, was utilized to extract hierarchical features including shape, texture, and color from the images [

17]. The resulting feature maps, shown in

Figure 8, provided valuable input for further analysis. It represented the original data in

Figure 8a. The middle images illustrated the feature extraction process, where

Figure 8b corresponded to the extraction of low-level features. At this step, the initial convolutional layers of ResNet50 detected and extracted low-level features such as edges, textures, and contrasts. This process was commonly referred to as edge detection, which played a crucial role in learning patterns within CNN architectures. In

Figure 8c, as the network depth increased, the model learned high-level features, allowing it to recognize plant shapes and structural patterns. This step facilitated the classification of crops based on leaf structure and morphological characteristics. It also presented a binarized contour image in

Figure 8d, demonstrating the segmentation process utilizing feature maps extracted by ResNet50. This technique enhanced plant contour detection, allowing for the analysis of plant growth status and the extraction of specific structural features.

The combination of YOLOv11 for instance segmentation and ResNet50 for feature extraction facilitated the precise identification of crop regions while providing additional data on size and color ratio. These extracted features were subsequently integrated to enhance the model’s predictive performance. Furthermore, the image-based data were combined with tabular data containing environmental parameters that influence CO2 absorption, as well as hierarchical and physical crop characteristics. The final integrated dataset served as input for the neural network model, enabling the prediction of CO2 absorption rates with high accuracy.

Furthermore, the extracted data were combined with tabular data, which included environmental factors affecting water CO2 absorption, as well as hierarchical and physical features. This integrated dataset was then used as input for the neural network model, to predict the CO2 absorption rates of the crops.

The model’s hyperparameters were optimized, and the final model was trained with a batch size of 32. As shown in

Figure 9, training was halted at 100 epochs using an early stopping protocol to prevent overfitting. The performance of this optimized model was evaluated on the test set, achieving a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 0.95 and a Mean Squared Error (MSE) of 1.62. This indicates a high level of predictive accuracy across the five different crop types and their growth stages. The corresponding training and validation loss curves demonstrate that the validation loss reached its minimum at approximately 100 epochs, after which it began to rise while the training loss continued to decrease indicating the onset of overfitting. Therefore, the model corresponding to the 100th epoch was selected as the optimal model for further analysis. Unlike previous studies that primarily focused on a single crop type, the proposed model successfully predicted CO

2 absorption patterns across five different crops and their respective growth stages. The following results compare the model’s predictions with experimental measurements to validate its performance across various crop conditions.

The predictive performance of the deep learning model was validated by comparing its predicted CO

2 concentrations with the experimentally measured values on DPT 1, as shown in

Figure 10. Under these conditions, the order of CO

2 absorption was observed as follows: green skirt lettuce > bok choy > lettuce red > romaine lettuce > red skirt lettuce. During the early growth stage, CO

2 concentrations ranged from 1000 to 1100 ppm, and from 1150 to 1200 ppm just before the late growth stage. These results indicate that the model successfully captured both crop-specific and time-dependent variations in CO

2 uptake. In addition, texture-based feature extraction from leaf images revealed that crops with reddish leaf coloration tended to exhibit slower growth and delayed CO

2 absorption. This observation supports the variation in uptake patterns, which can be attributed to phenotypic differences in leaf development during early growth.

3.3. Energy Conversion Results

To conduct the analysis using the empirical crop model, experimental data were collected under controlled smart farm conditions representative of Korea’s atmospheric environment. As previously described, average O

3 and SO

2 concentrations in Korea were applied in the model using one month of monitoring data from Air Korea, with values of 0.09 ppm and 0.008 ppm, respectively [

22,

23].

Figure 11 shows that as CO

2 concentration increased from 400 to 1200 ppm, leaf conductance decreased by 36.4%, while crop yield increased by 9.27%.

By applying the calculated internal resistance and other collected parameters, annual evapotranspiration per unit area across CO

2 concentrations was determined.

Figure 12 indicates that water required for evapotranspiration decreased by approximately 11%.

To quantify the energy savings associated with reduced evapotranspiration, the energy required for agricultural water use was calculated. In Korea, agricultural water primarily relies on groundwater [

25]. The power consumption required for groundwater pumping was determined using (7) [

26]. In

Table 3, W

lift represents total dynamic head in meters, and η denotes pump efficiency, typically set at 40% [

27]. Groundwater depth was estimated at approximately 33.7 m. Annual energy requirements per unit area were 0.43 kWh at 400 ppm CO

2 and decreased to 0.38 kWh at 1200 ppm, representing an 11% reduction in energy consumption.

It presents the variations in crop growth, water consumption, and CO

2 absorption for each method, as summarized in

Table 4 and

Figure 13. The developed model was utilized to maintain the CO

2 concentration within the range of 1000 to 1200 ppm during the growth stages, thereby optimizing the CO

2 concentration process. Continuing with this methodology, the optimization of CO

2 concentration resulted in increased photosynthetic activity, reduced leaf stomatal conductance, and consequently, a decrease in the CO

2 injection required to maintain the optimized concentration [

28]. As a result, water consumption was reduced, and crop growth was enhanced.

4. Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations should be acknowledged. The controlled environment employed fixed light intensity (100 W LED), temperature (25–30 °C), and CO2 range (400–1200 ppm), limiting extrapolation to variable field conditions. Chamber-scale experiments (8 plants) do not replicate commercial-scale spatial heterogeneity. The model was trained exclusively on five leafy vegetable species grown hydroponically; generalization to other crop types requires additional validation. CO2 measurements represent chamber-level integrated exchange, and LAI was held constant (4.4) due to equipment constraints, potentially underestimating temporal growth dynamics. Yield improvements (9.3%) and water savings (11.1%) are simulation-based estimates requiring validation through harvest trials. Despite these limitations, this study demonstrates that vision-based multi-species CO2 monitoring is feasible without invasive measurements, providing a validated framework for future pilot-scale implementation. Priority future work includes expanding crop diversity, testing variable environmental conditions, implementing continuous LAI measurement, and conducting harvest validation trials.

5. Conclusions

This study established a vision-based framework for non-invasive, multi-species CO2 monitoring in controlled environment agriculture, addressing the critical need for automated crop-responsive CO2 management without species-specific recalibration. Three key findings demonstrate practical feasibility.

First, the hybrid deep learning model integrating YOLOv11 segmentation, ResNet50 features, and environmental data achieved accurate CO2 prediction across five leafy vegetable species (MAE = 0.95 ppm, MSE = 1.62), eliminating the need for invasive gas exchange measurements.

Second, variable CO2 enrichment optimized through this monitoring approach yielded 7.4% greater cumulative CO2 absorption compared to fixed enrichment, translating to projected 9.3% yield improvements and 11.1% water savings through reduced evapotranspiration.

Third, energy analysis demonstrated net positive returns, with reduced water pumping requirements offsetting CO2 generation costs. The proposed system is scalable, non-destructive, and compatible with existing smart farm infrastructure, enabling real-time optimization of CO2 supplementation for enhanced resource efficiency. While harvest-level validation is necessary to confirm simulated yield benefits, the validated monitoring framework provides growers with a practical tool for implementing data-driven CO2 management strategies that improve both crop productivity and environmental sustainability in indoor agriculture.