Tourism-Driven Land Use Transitions and Rural Livelihood Resilience: A Spatial Production Approach to Sustainable Development in China’s Heritage Areas

Abstract

1. Introduction

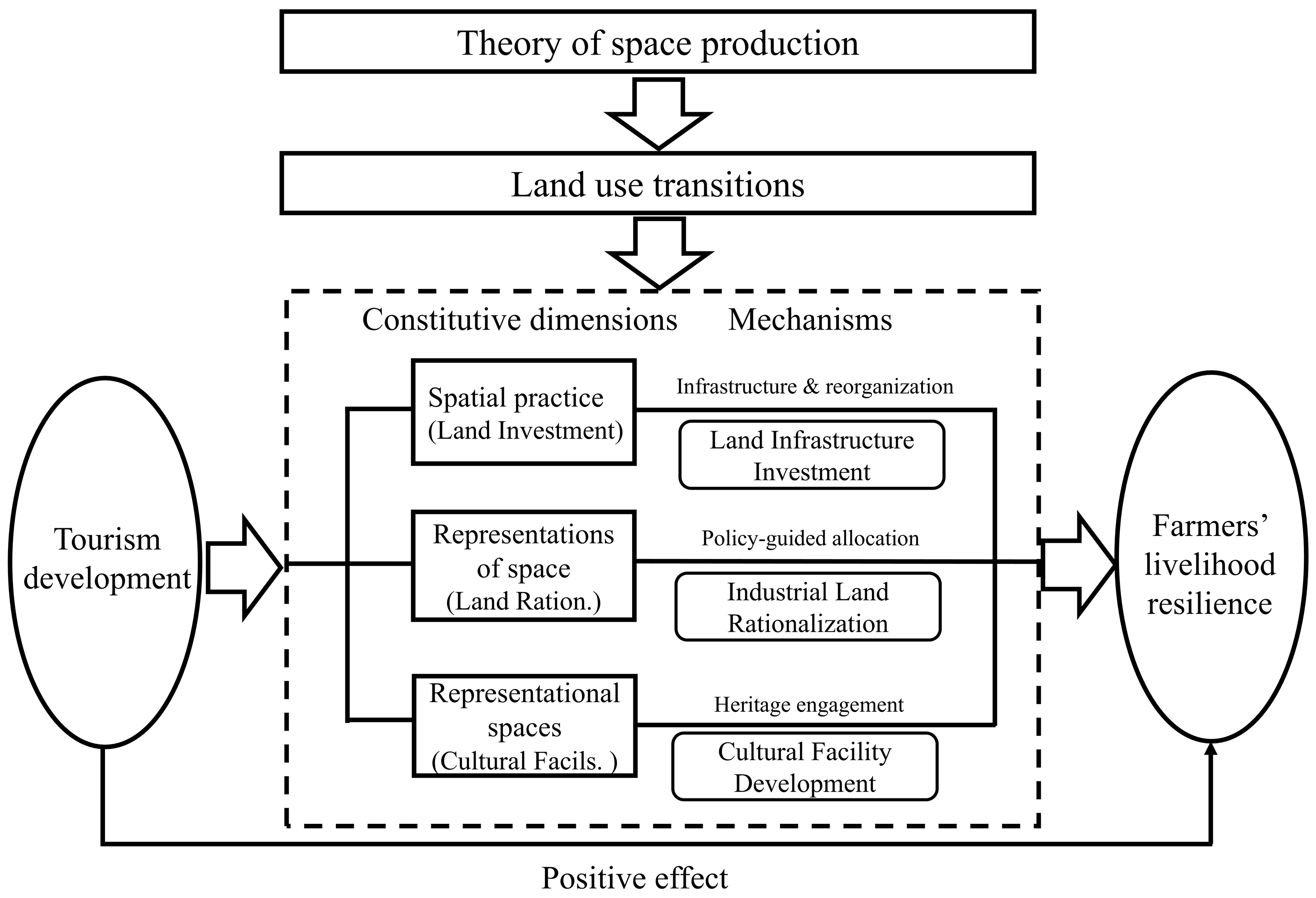

2. Theoretical Foundation and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical Foundation

2.2. Land Use Transitions Through Tourism Development and Farmers’ Livelihood Resilience

2.3. The Non-Linear Effects of Tourism-Driven Land Use Transitions on Farmers’ Livelihood Resilience

3. Research Design

3.1. Model Construction

3.2. Variable Definitions and Descriptions

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Core Explanatory Variable

3.2.3. Control Variables

3.2.4. Mediating Variables

3.3. Data Sources

3.3.1. Individual- and Household-Level Indicators

3.3.2. Regional-Level Indicators

3.4. Spatial Distribution of Key Variables

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Regression Results

4.2. Robustness and Endogeneity Tests

4.2.1. Instrumental Variable Approach

4.2.2. High-Dimensional Fixed Effects

4.2.3. Alternative Measures of the Dependent Variable

4.2.4. Subsample Regression Below the Median

5. Mechanism and Heterogeneity Analysis

5.1. Mechanism Analysis

5.2. Threshold Effect Analysis

5.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.4. Discussion

5.4.1. Tourism-Induced Land Transitions and Livelihood Resilience

5.4.2. Non-Linear Threshold Effects

5.4.3. Mediating Mechanisms in Comparative Perspective

5.4.4. Regional Heterogeneity and Policy Implications

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

6.1. Summary of Findings

6.2. Theoretical Implications

6.3. Policy Implications

6.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CFPS | China Family Panel Studies |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| ISEI | International Socio-Economic Index |

| 2SLS | Two-Stage Least Squares |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| R&D | Research and Development |

| PM2.5 | Particulate Matter 2.5 micrometers or smaller |

References

- Quandt, A. Measuring livelihood resilience: The household livelihood resilience approach (HLRA). World Dev. 2018, 107, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Wang, Y. Towards sustainable development: Understanding resilience capacity and well-being of rural households in the Dabie Mountainous Area, China. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 13673–13721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazilu, M.; Niță, A.; Băbăț, A.; Drăguleasa, I.A.; Grigore, M. Risk and sustainable tourism resilience in the post economic crisis and COVID-19 pandemic period. Present Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 18, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Zhou, Y. How rural tourism development affects farmers’ livelihood resilience: Based on comprehensive survey data of rural revitalization in China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1573149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Gao, Y.; Cao, X.; Yang, J. Contributions and resistances to vulnerability of rural human settlements system in agricultural areas of Chinese loess plateau since 1980. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Mishra, K.A.; Pramanik, S.; Mamidanna, S.; Whitbread, A. Climate risk, vulnerability and resilience: Supporting livelihood of smallholders in semiarid India. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Xiang, H.; Zhao, F. Measurement and spatial differentiation of farmers’ livelihood resilience under the COVID-19 epidemic outbreak in rural China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2023, 166, 239–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, Y. Unveiling the role of social networks: Enhancing rural household livelihood resilience in China’s Dabie Mountains. J. Geogr. Sci. 2025, 35, 335–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, J.; Zhu, C.; Li, Y.; Sun, W.; Li, J. Factors influencing livelihood resilience of households resettled from coal mining areas and their measurement—A case study of Huaibei City. Land 2023, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, J.; Ren, L.; Xu, J.; Li, C.; Li, S. Exploring livelihood resilience and its impact on livelihood strategy in rural China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 150, 977–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y. Measurement of livelihood resilience and its influencing factors for farmers in poverty alleviation areas: A case study of Yunnan Province, China. Appl. Econ. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Dong, J. Measuring livelihood resilience of farmers and diagnosing obstacle factors under the impact of COVID-19 in Jiangsu Province, China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1250564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Guo, D.; Zuo, J.; Yang, J.; Liu, S. Evolution characteristics and obstacle factors of rural resilience in Chinese minority areas in the background of rural tourism and COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, S.; Akter, S. Determinants of livelihood choices: An empirical analysis from rural Bangladesh. J. S. Asian Dev. 2014, 9, 287–308. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Nijkamp, P.; Xie, X.; Liu, J. A new livelihood sustainability index for rural revitalization assessment—A modelling study on smart tourism specialization in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Xian, Z.; Zhu, T.; Kang, X. Research on livelihood capital, endogenous development momentum and sustainable livelihoods of relocated farmers. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 102, 104259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Bai, Y.; Alatalo, J.M. Impacts of rural tourism-driven land use change on ecosystems services provision in Erhai Lake Basin, China. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 42, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Meng, J.; Wang, Q. Modeling the effects of tourism and land regulation on land-use change in tourist regions: A case study of the Lijiang River Basin in Guilin, China. Land Use Policy 2014, 41, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasso, A.; Dahles, H. Are tourism livelihoods sustainable? Tourism development and economic transformation on Komodo Island, Indonesia. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Yao, Y.; Li, J. Sociocultural impacts of tourism on residents of world cultural heritage sites in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wall, G. Heritage tourism in a historic town in China: Opportunities and challenges. J. China Tour. Res. 2022, 18, 1073–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, C.-H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.-L.; Li, K.; Shang, Y. Current challenges and opportunities in cultural heritage preservation through sustainable tourism practices. Curr. Issues Tour. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Gong, Y.; Chen, Q.; Jin, X.; Mu, Y.; Lu, Y. Driving innovation and sustainable development in cultural heritage education through digital transformation: The role of interactive technologies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.N.; Timothy, D.J. Governance of red tourism in China: Perspectives on power and guanxi. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R. Red Tourism in Rural Beijing: The Hierarchical Governance and Grassroots Community Engagement. In Cultural Tourism in the Asia Pacific: Heritage, City and Rural Hospitality; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 131–148. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Wen, J.; Jiao, M.; Xiao, L. The Impact of Integrating Agriculture and Tourism on Poverty Reduction in China’s Ethnic Minority Areas. J. Int. Dev. 2025, 37, 1082–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon-Fajardo, V. Future trends in Red Tourism and communist heritage tourism. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 28, 1185–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Guo, X. Consuming revolution: The politics of red tourism in China. J. Macromark. 2017, 37, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, G.; Zhao, N.R. China’s red tourism: Communist heritage, politics and identity in a party-state. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2017, 3, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ma, L.; Park, K.S. The effect of the red cultural atmosphere on tourists’ subjective well-being: An application of the stimulus-organism-response model. Curr. Issues Tour. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.T.; Nyaupane, G.P. Protected areas, tourism and community livelihoods linkages: A comprehensive analysis approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 673–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Hughey, K.F.; Simmons, D.G. Connecting the sustainable livelihoods approach and tourism: A review of the literature. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2008, 15, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, Q.H.; Wang, H. Study on the spatial effect and mechanism of rural tourism development promoting rural sustainable livelihood. J. Nat. Resour. 2023, 38, 490–510. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1991; pp. 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Capello, R. Space, growth and development: A historical perspective and recent advances. In Handbook of Regional Growth and Development Theories; Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 24–47. [Google Scholar]

- McCann, P.; Van Oort, F. Theories of agglomeration and regional economic growth: A historical review. In Handbook of Regional Growth and Development Theories; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 6–23. [Google Scholar]

- Buser, M. The production of space in metropolitan regions: A Lefebvrian analysis of governance and spatial change. Plan. Theor. 2012, 11, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Tang, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Pan, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Tian, C. Enhancement and Evolutionary Mechanism of Ethnic Rural Tourism Resilience Based on the Actor Network Theory: A Case Study of Hala New Village in Northeast China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Gong, J.; Zeng, X. Research progress on land use and analysis of green transformation in China since the new century. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Cheng, L. Tourism-driven rural spatial restructuring in the metropolitan fringe: An empirical observation. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, X. Spatial–Temporal differentiation and the driving mechanism of rural transformation development in the Yangtze River economic belt. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. Red tourism: Rethinking propaganda as a social space. Commun. Crit. Cult. Stud. 2015, 12, 328–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lai, Y.; Huo, C. How do environmental and cultural factors shape red tourism behavioral intentions: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1566533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Kenderdine, S.; Picca, D.; Egloff, M.; Adamou, A. Digitizing intangible cultural heritage embodied: State of the art. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2022, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Wen, L. Development and application of red cultural education resources based on artificial intelligence. J. Comput. Methods Sci. Eng. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. A study on high-quality development of China’s red tourism from the perspective of ceremony sense. Int. J. Res. Stud. Educ. 2023, 12, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B. A theory of the city as object: Or, how spatial laws mediate the social construction of urban space. Urban Des. Int. 2002, 7, 153–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, L. Multifunctional rural development in China: Pattern, process and mechanism. Habitat Int. 2022, 121, 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Wang, L. Spatial differentiation and influencing factors of red tourism resources transformation efficiency in China based on RMP-IO analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Sun, D.; Wang, Z. Exploring the rural revitalization effect under the interaction of agro-tourism integration and tourism-driven poverty reduction: Empirical evidence for China. Land 2024, 13, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, P.; Sun, Y.; Chen, P. Evaluation of Farmers’ Livelihood Vulnerability in Border Rural Tourism Destination and Its Influencing Factors—Take Tumen City, Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture, Jilin Province, as an Example. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, B.; Gursoy, D.; Wall, G. Residents’ support for red tourism in China: The moderating effect of central government. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 64, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, B.; Qiu, H. How a hierarchical governance structure influences cultural heritage destination sustainability: A context of red tourism in China. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 50, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Sun, G.; Zhou, W.; Lian, J.; Sun, Y.; Hu, Y. Promoting Rural Revitalization via Natural Resource Value Realization in National Parks: A Case Study of Baishanzu National Park. Land 2025, 14, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbumozhi, V. Improving the resilience of regional food value chains against climate change and natural disasters. In Vulnerability of Agricultural Production Networks and Global Food Value Chains Due to Natural Disasters; Breiling, M., Anbumozhi, V., Eds.; Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA): Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020; pp. 153–167. Available online: https://www.eria.org/uploads/media/Books/2020-Jan/Vulnerability-of-Agricultural-Production-Networks_Full-Report.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Lu, Y. Transforming China’s tourism industry: The impact of industrial integration on quality, performance, and productivity. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 18116–18153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, W.; Loang, O.K. China’s cultural tourism: Strategies for authentic experiences and enhanced visitor satisfaction. Int. J. Bus. Technol. Manag. 2024, 6, 566–575. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J. Revitalization of Old Revolutionary Base Areas: Challenges, Opportunities and Pathways. China Econ. 2024, 19, 55–84. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; Cui, X.; Hou, M.; Lu, W.; Xie, Y.; Xi, Z.; Liu, C.; Shao, H.; Shan, Y. Assessing the impact of the national revitalization plan for old revolutionary base areas on green development. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamidullaeva, L.; Vasin, S.; Tolstykh, T.; Zinchenko, S. Approach to regional tourism potential assessment in view of cross-sectoral ecosystem development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, B.; Russell, R. Chaos and complexity in tourism: In search of a new perspective. Pac. Tour. Rev. 1997, 1, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Incera, A.C.; Fernández, M.F. Tourism and income distribution: Evidence from a developed regional economy. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, L.; De Bruin, S.; Knoop, J.; van Vliet, J. Understanding land-use change conflict: A systematic review of case studies. J. Land Use Sci. 2021, 16, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speranza, C.I.; Wiesmann, U.; Rist, S. An indicator framework for assessing livelihood resilience in the context of social–ecological dynamics. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 28, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.B.; Yang, J.Q. Livelihood Resilience of Rural Household and Household Educational Expectation-Empirical Analysis Basedon the Data of CFPS. J. Shanxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 2023, 45, 16–30. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.B.; Tian, Y.P. Validity Analysis of Tourism Resources Competitiveness and Tourism Development Level in Pearl River Delt. Econ. Geogr. 2019, 39, 218–224+239. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Zhu, F.S.; Gan, C.; Xi, J.C. The coupling coordination relationship between industrial structure transformation and upgrade level and tourism poverty alleviation efficiency: A case study of Wuling Mountain Area. J. Nat. Resour. 2020, 35, 1617–1632. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. The development and institutional characteristics of China’s built heritage conservation legislation. Built Herit. 2022, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Wang, M.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Shen, W.; Yin, J.; You, J. Synergizing Conservation and Tourism Utilization in Agricultural Heritage Sites: A Comparative Analysis of Economic Resilience in Wujiang and Longsheng, China. Land 2025, 14, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanescu, B.; Eva, M.; Gheorghiu, A.; Iatu, C. Tourism-Induced Resilience of Rural Destinations in Relation to Spatial Accessibility. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2023, 16, 1237–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Călina, J.; Călina, A.; Vangu, G.M.; Croitoru, A.C.; Miluț, M.; Băbucă, N.I.; Stan, I. A Study on the Management and Evolution of Land Use and Land Cover in Romania During the Period 1990–2022 in the Context of Political and Environmental Changes. Agriculture 2025, 15, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drăguleasa, I.-A.; Niță, A.; Mazilu, M.; Curcan, G. Spatio-Temporal Distribution and Trends of Major Agricultural Crops in Romania Using Interactive Geographic Information System Mapping. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Specific Indicator | Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Buffer Capacity | Per Capita Income: Annual household disposable income per capita (Yuan) | 0.053 |

| Labor Force Status: (Labor Capacity × 0.5) + (Number of Laborers × 0.5) (Labor Capacity is the sum of working capacity of family members, where 1 = Children aged 0–9 and unhealthy members; 2 = Healthy children aged 10–15; 3 = Healthy elderly over 65; 4 = Healthy young adult helpers aged 16–18; 5 = Healthy adults aged 19–65. Number of Laborers is the number of family members aged 16–65) | 0.021 | |

| Average Education Level: Average years of schooling per household member (Years) | 0.023 | |

| Housing Capital: Net value of household housing assets (Yuan) | 0.059 | |

| Productive and Living Assets: Total value of household durable consumer goods and productive fixed assets (Yuan) | 0.082 | |

| Natural Capital: Value of household land assets (Yuan) | 0.124 | |

| Self-Organization Capacity | Social Network: Annual household expenditure on gifts and social courtesy (Yuan) | 0.075 |

| Social Interaction: Annual household expenditure on post, telecommunications, and communications (Yuan) | 0.058 | |

| Social Trust: Average level of trust family members place in their neighbors | 0.005 | |

| Social Prestige: Average International Socio-Economic Index (ISEI) occupational prestige score of the household’s labor force | 0.015 | |

| Learning Capacity | Education Level of Household Head: Years of schooling of the household head (Years) | 0.037 |

| Education and Training Expenditure: Annual household expenditure on adult education and training (Yuan) | 0.132 | |

| Non-Agricultural Employment: Proportion of household laborers engaged in non-agricultural occupations (%) | 0.300 | |

| Internet Usage: Perceived importance of the internet for information acquisition by family members (average) | 0.016 |

| Dimension | Specific Indicator | Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Foundation for Tourism Development | Ratio of Domestic Tourist Numbers to Local Resident Population | 0.025 |

| Proportion of Domestic Tourism Revenue in GDP | 0.026 | |

| Ratio of Tertiary Sector Employees to Local Resident Population | 0.028 | |

| Number of Heritage Tourism-Related Policies Issued | 0.203 | |

| Road Network Density | 0.023 | |

| Number of Travel Agencies | 0.028 | |

| Number of Art Performance Venues | 0.034 | |

| Tourism Resource Endowment | Number of Movable Historical Cultural Relics | 0.148 |

| Number of Immovable Historical Cultural Relics | 0.023 | |

| Number of Heritage Education Demonstration Bases/Study and Education Bases | 0.120 | |

| Number of National Heritage Tourism Sites | 0.041 | |

| Number of Heritage Tourism Routes | 0.037 | |

| Number of National Heritage Tourism Cases | 0.046 | |

| Number of Cultural and Heritage Tourism Enterprises | 0.022 | |

| Innovation Support for Tourism Development | Number of Tourism Technology Patents | 0.083 |

| R&D Expenditure in Tourism | 0.031 | |

| Number of Internet Broadband Access Subscribers | 0.048 | |

| Ecological Environment for Tourism Development | Forest Coverage Rate | 0.025 |

| PM2.5 Emissions | 0.007 | |

| Rate of Harmless Treatment of Household Waste | 0.003 |

| Type | Variables | Variable Definition | Observations | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Farmers’ Livelihood Resilience | Calculated based on the entropy weight method and the livelihood resilience measurement index system for rural households | 12,133 | 0.0680 | 0.0300 | 0.0100 | 0.391 |

| Core Explanatory Variable | Tourism Development Level | Calculated based on the entropy weight method and the tourism development level measurement index system (capturing land use transformation intensity associated with tourism) | 12,133 | 0.183 | 0.0730 | 0.0670 | 0.432 |

| Provincial Control Variables | Population Aging | Proportion of village population aged 65 and above | 12,133 | 0.138 | 0.0310 | 0.0860 | 0.229 |

| Rural Medical Level | Number of township health centers (units) | 12,133 | 1538 | 821.4 | 138 | 4490 | |

| Financing Convenience | Proportion of rural loans in GDP | 12,133 | 0.344 | 0.157 | 0.0170 | 0.653 | |

| Industrial Structure Advancement | Ratio of value-added of the tertiary sector to that of the secondary sector | 12,133 | 1.291 | 0.330 | 0.847 | 5.297 | |

| Land Transfer | Total area of transferred contracted cultivated land (10,000 mu) | 12,133 | 1917 | 1244 | 123.4 | 6590 | |

| Household Control Variables | Land Outflow | =1 if the household has land outflow; =0 otherwise | 10,705 | 0.141 | 0.348 | 0 | 1 |

| Household Head Control Variables | Gender of Household Head | =1 if male; =0 if female | 12,133 | 0.583 | 0.493 | 0 | 1 |

| Marital Status | =1 if married; =0 if unmarried | 12,133 | 0.947 | 0.225 | 0 | 1 | |

| Communist Party Member | =1 if yes; =0 if no | 11,408 | 0.0310 | 0.173 | 0 | 1 | |

| Mediating Variables | Industrial Structure Rationalization | ln(/) where TL, Y, L, n, and i represent the industrial structure rationalization index, gross output value of the three sectors (10,000 Yuan), total employment in the three sectors (10,000 persons), number of industrial sectors, and a specific sector, respectively. | 12,133 | 0.427 | 0.200 | 0.0380 | 1.810 |

| Rural Land-Based Investment | Total investment in fixed assets by rural households (100 million Yuan) | 12,133 | 365.9 | 238.4 | 4.200 | 958.6 | |

| Cultural Facility Construction | Ratio of the number of township cultural stations to the rural population | 12,133 | 0.639 | 0.214 | 0.302 | 1.090 |

| Variables | Farmers’ Livelihood Resilience | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |||

| Coef. | Robust Std. Err. | Coef. | Robust Std. Err. | |

| Tourism Development Level | 0.0629 ** | 2.0471 | 0.1086 *** | 2.7771 |

| Population Aging | −0.3796 *** | −3.3549 | ||

| Rural Medical Level | −0.0000 | −0.6943 | ||

| Financing Convenience | 0.0049 | 0.1490 | ||

| Industrial Structure Advancement | −0.0032 | −0.3306 | ||

| Land Transfer | −0.0000 | −0.2476 | ||

| Land Outflow (Household) | 0.0143 *** | 6.0454 | ||

| Gender of Household Head | 0.0056 *** | 3.6924 | ||

| Marital Status | −0.0011 | −0.2339 | ||

| Communist Party Member | 0.0284 *** | 6.2798 | ||

| Constant | 0.2001 *** | 35.4809 | 0.2774 *** | 3.9720 |

| Year Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | ||

| Province Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | ||

| N | 12,133 | 10,185 | ||

| R2 | 0.0808 | 0.0823 | ||

| Variables | Instrumental Variable Regression Results | |

|---|---|---|

| First Stage | Second Stage | |

| Tourism Development Level | 0.0649 * | |

| (2.65) | ||

| Interaction Term: Number of Founding Generals × Year | 52.7898 *** | |

| (24.03) | ||

| Control Variables | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes |

| Province Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes |

| N | 10,621 | 10,621 |

| F-statistic (Weak Instrument Test) | 577.43 | |

| Variables | Control Household Fixed Effects | Replace y with Equal Weighting for Indicators | Replace y with Equal Weighting for Dimensions | Subsample Regression (Below Median) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Tourism Development Level | 0.0340 *** | 0.0362 *** | 0.0370 *** | 0.0341 *** |

| (3.6417) | (3.0060) | (3.0674) | (4.7340) | |

| Control Variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Household Fixed Effects | Yes | No | No | No |

| N | 8438 | 10,621 | 10,621 | 5601 |

| R2 | 0.8130 | 0.0776 | 0.0777 | 0.0660 |

| Variable | Rural Land-Based Investment | Farmers’ Livelihood Resilience | Industrial Land Structure Rationalization | Farmers’ Livelihood Resilience | Cultural Facility Construction | Farmers’ Livelihood Resilience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Tourism Development Level | 1.7526 *** | 0.0311 *** | −0.0843 *** | 0.0328 *** | 27.8441 *** | 0.0890 *** |

| (14.2946) | (2.5812) | (−3.2045) | (2.7342) | (26.0103) | (17.2953) | |

| Rural Investment | 0.0016 * | |||||

| (1.7924) | ||||||

| Industrial Structure Rationalization | −0.0132 ** | |||||

| (−2.2923) | ||||||

| Cultural Stations per 10,000 People | 0.0001 ** | |||||

| (2.1869) | ||||||

| _cons | 4.8118 *** | 0.0405 * | 0.1798 *** | 0.0584 ** | 3.6863 *** | 0.0392 *** |

| (25.5814) | (1.7017) | (6.4492) | (2.4461) | (5.8722) | (12.9820) | |

| Control Variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 10,062 | 10,062 | 10,062 | 10,062 | 10,062 | 10,062 |

| R2 | 0.8918 | 0.0860 | 0.9439 | 0.0860 | 0.4887 | 0.0575 |

| Sobel | 0.075 (z = 1.775) * | 0.046 (z = 1.995) ** | 0.029 (z = 2.183) ** | |||

| Goodman-1 | 0.076 (z = 1.769) * | 0.051 (z = 1.95) * | 0.029 (z = 2.182) ** | |||

| Goodman-2 | 0.075 (z = 1.78) * | 0.041 (z = 2.043) ** | 0.028 (z = 2.184) ** | |||

| Threshold Variable | Number of Thresholds | Estimated Value | F-Value | p-Value | BS Reps | 10% Critical Value | 5% Critical Value | 1% Critical Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism Development Level | Single Threshold | 0.1546 | 24.68 *** | 0.000 | 300 | 8.960 | 10.099 | 11.209 |

| Double Threshold | 0.2092 | 10.02 ** | 0.050 | 300 | 8.736 | 10.017 | 12.902 |

| Variable | Threshold Model |

|---|---|

| Tourism_Land × I (Tourism_Land < 0.1546) | 0.171 *** (8.11) |

| Tourism_Land × I (0.1546 ≤ Tourism_Land < 0.2092) | 0.088 *** (6.73) |

| Tourism_Land × I (Tourism_Land ≥ 0.2092) | 0.076 *** (7.34) |

| Control Variables | Yes |

| Number of Observations | 9604 |

| Variable | Farmers’ Livelihood Resilience | |

|---|---|---|

| Heritage-Rich Region > 50% | Heritage-Rich Region ≤ 50% | |

| Tourism Development Level | 0.0566 *** | −0.0064 |

| (3.0199) | (−0.2626) | |

| _cons | 0.0562 *** | −0.0021 |

| (2.5931) | (−0.0500) | |

| Control Variables | Yes | Yes |

| Province Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes |

| N | 7091 | 2971 |

| R2 | 0.0762 | 0.1172 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, L.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y. Tourism-Driven Land Use Transitions and Rural Livelihood Resilience: A Spatial Production Approach to Sustainable Development in China’s Heritage Areas. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10839. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310839

Liu L, Liu X, Zhang Y. Tourism-Driven Land Use Transitions and Rural Livelihood Resilience: A Spatial Production Approach to Sustainable Development in China’s Heritage Areas. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10839. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310839

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Lijie, Xinmin Liu, and Yanan Zhang. 2025. "Tourism-Driven Land Use Transitions and Rural Livelihood Resilience: A Spatial Production Approach to Sustainable Development in China’s Heritage Areas" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10839. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310839

APA StyleLiu, L., Liu, X., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Tourism-Driven Land Use Transitions and Rural Livelihood Resilience: A Spatial Production Approach to Sustainable Development in China’s Heritage Areas. Sustainability, 17(23), 10839. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310839