Deep Learning-Enabled Policy Optimization for Sustainable Ship Registry Selection

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We apply Deep Reinforcement Learning to the flag-of-registry selection problem, addressing the limitations of traditional static discrete choice models. We formulate flag selection as a sequential decision process. This approach captures how current choices influence future inspection risks and operational costs, offering a new theoretical lens for sustainability trade-offs.

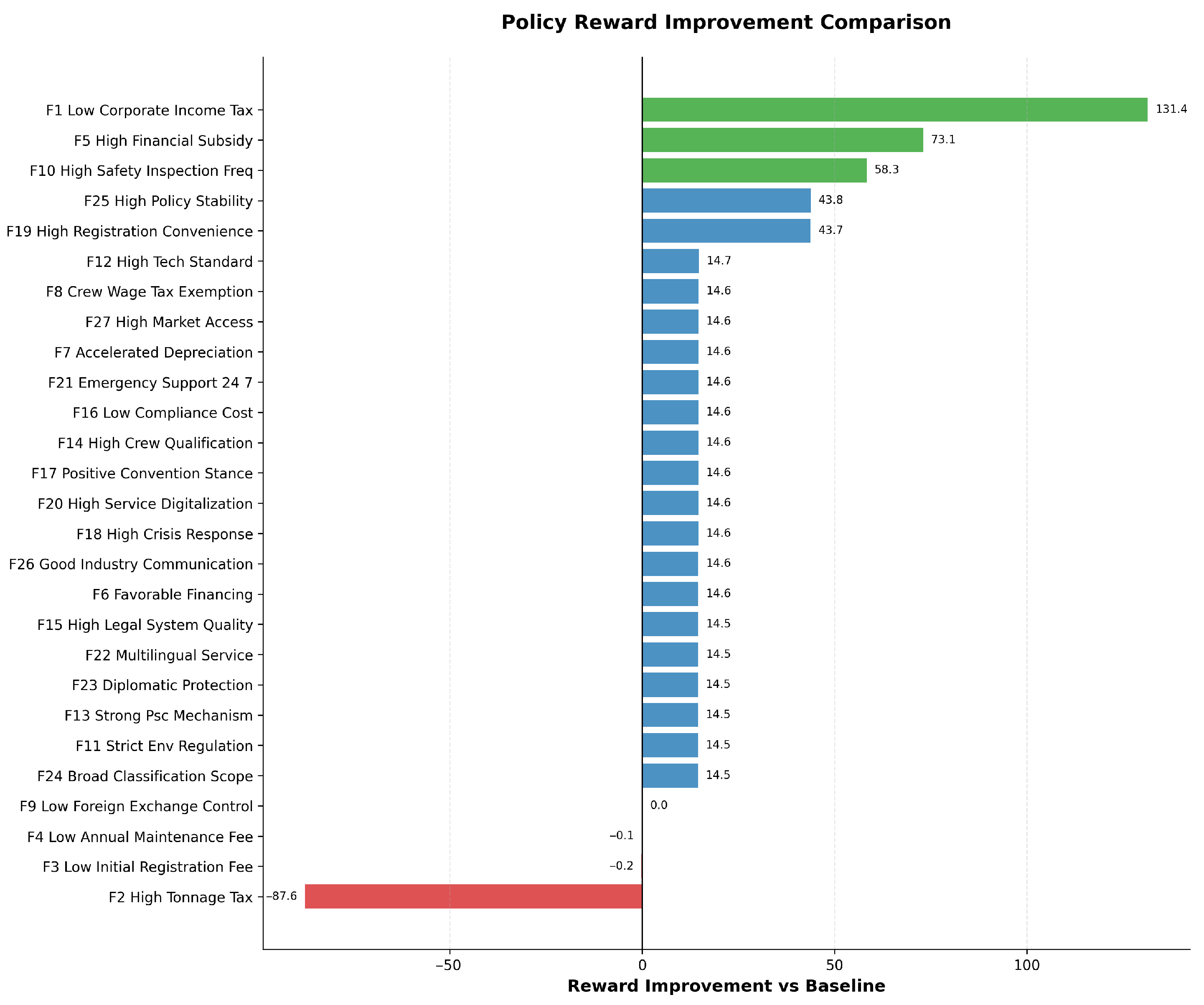

- We provide a systematic quantification of feature importance across 27 specific policy levers. Our results reveal significant heterogeneity in effectiveness, demonstrating that economic incentives (e.g., corporate tax reductions) can serve as the necessary foundation for environmental investments, while improper fiscal measures may trigger a “race to the bottom” dynamic.

- We develop a dynamic policy simulation framework that allows maritime administrations to conduct ex ante scenario analysis. This tool enables policymakers to estimate the potential long-term cumulative effects of integrated policy portfolios on fleet competitiveness and ESG performance before actual implementation, reducing trial-and-error costs in governance.

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. Problem Definition and Factor Identification

3.2. Sustainable Flag Selection Modeling Based on Reinforcement Learning

| Algorithm 1 Training Procedure of Sustainability-Oriented Attention-DQN |

|

3.3. Sustainability Policy Impact Quantification and Priority Ranking

- Implementation Feasibility: The administrative and legal complexity of enacting the policy.

- Fiscal Efficiency: The cost–benefit ratio from the government’s perspective.

- Strategic Alignment: Consistency with long-term national maritime goals.

4. Case Study and Data Description

4.1. Dataset Construction and Feature Engineering

- Tier 1 (Public Databases): 15 factors (e.g., corporate tax rates, convention ratifications) were sourced from open international databases such as OECD Statistics, IMO GISIS, and the World Bank.

- Tier 2 (Industry Reports): 8 factors (e.g., registration fees, compliance costs) were compiled from official registry fee schedules and industry reports (e.g., BIMCO, Drewry).

- Tier 3 (Constructed Indicators): 4 factors were synthesized methodologically. For instance, “Policy Stability” (F25) was calculated as the inverse variance of regulatory changes over a 5-year rolling window.

4.2. Baseline Parameter Configuration

5. Results and Analysis

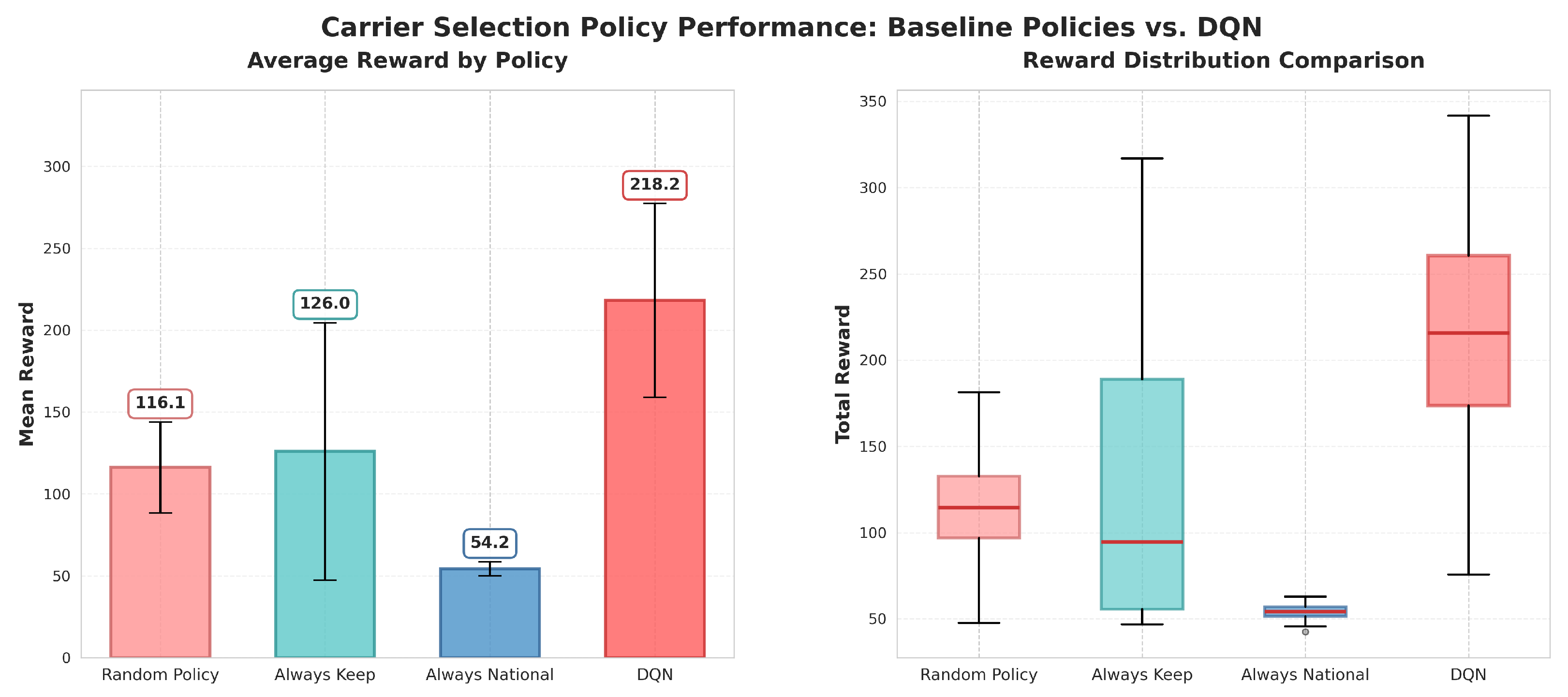

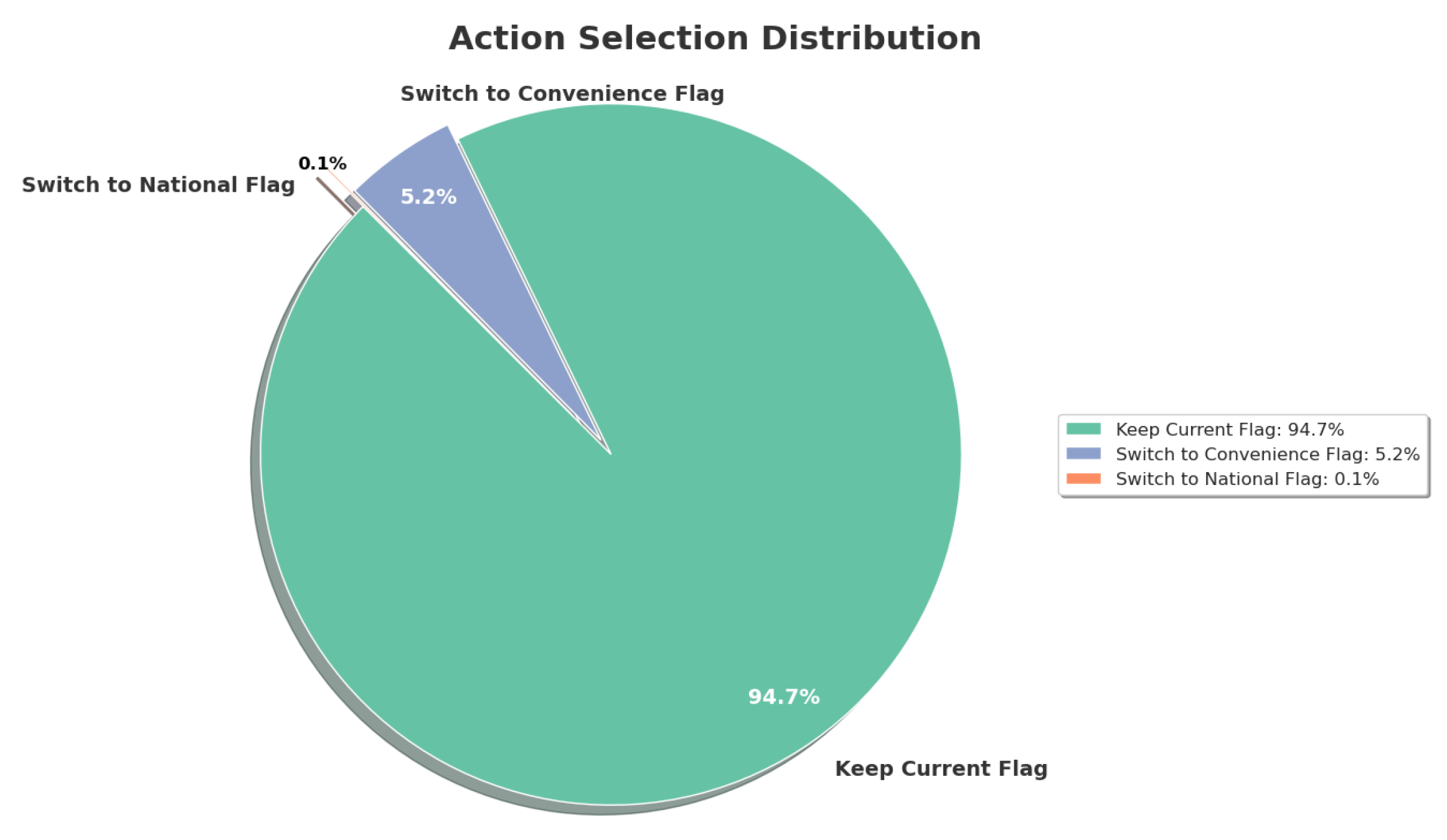

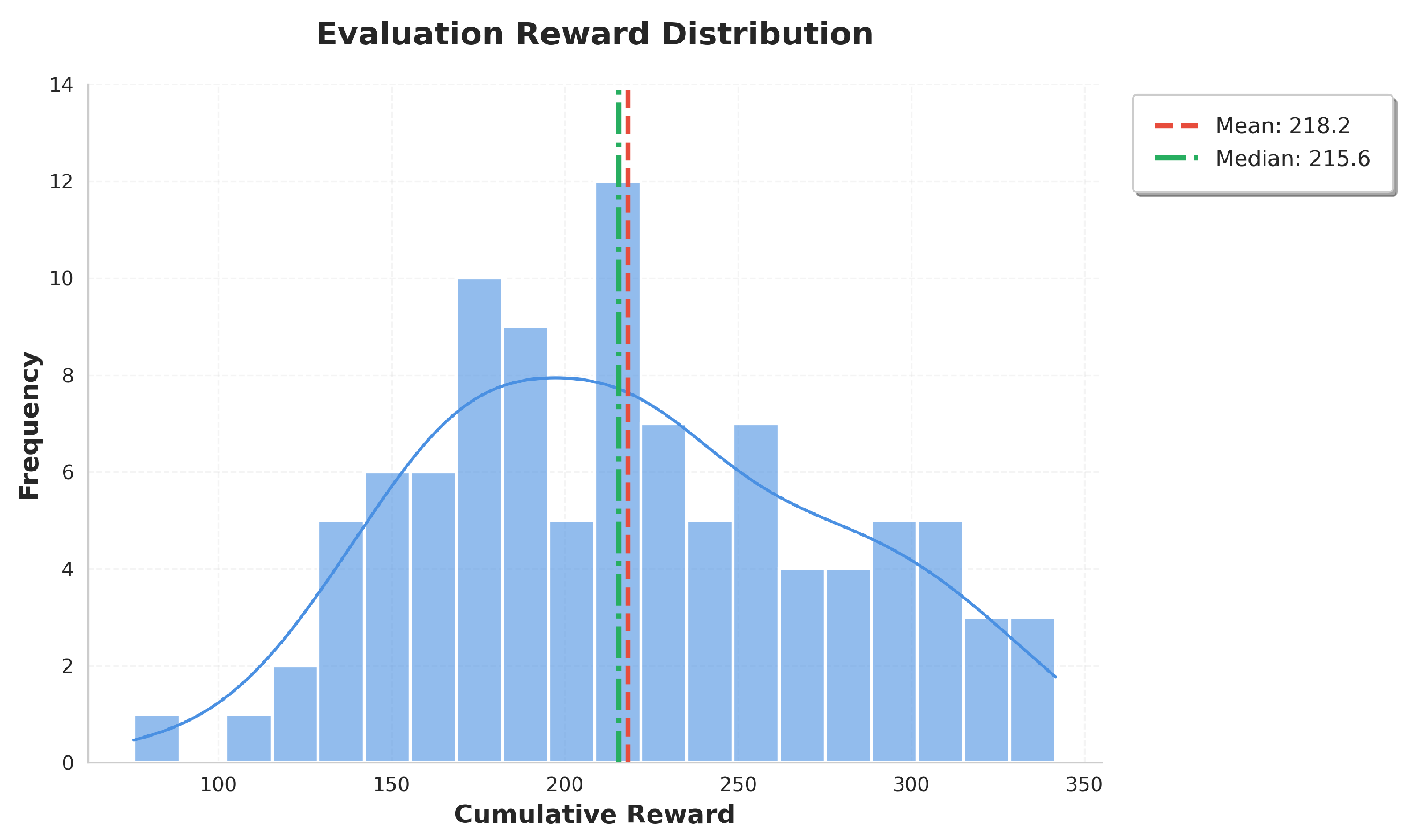

5.1. Model Performance Comparison: Validating Sustainable Policy Learning

5.2. Policy Reward Improvement Comparative Analysis

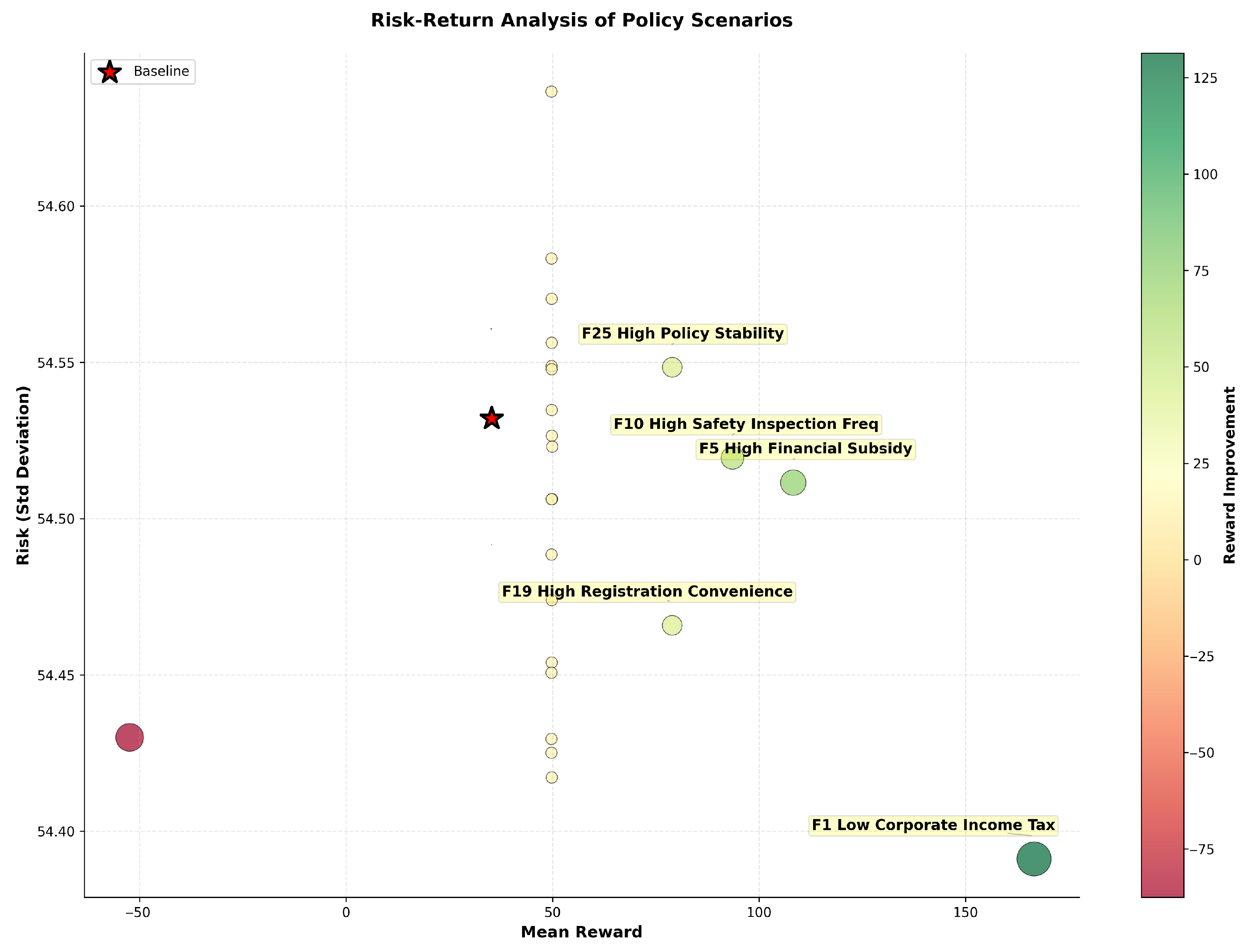

5.3. Risk-Return Profile Analysis

5.4. Multi-Dimensional Evaluation

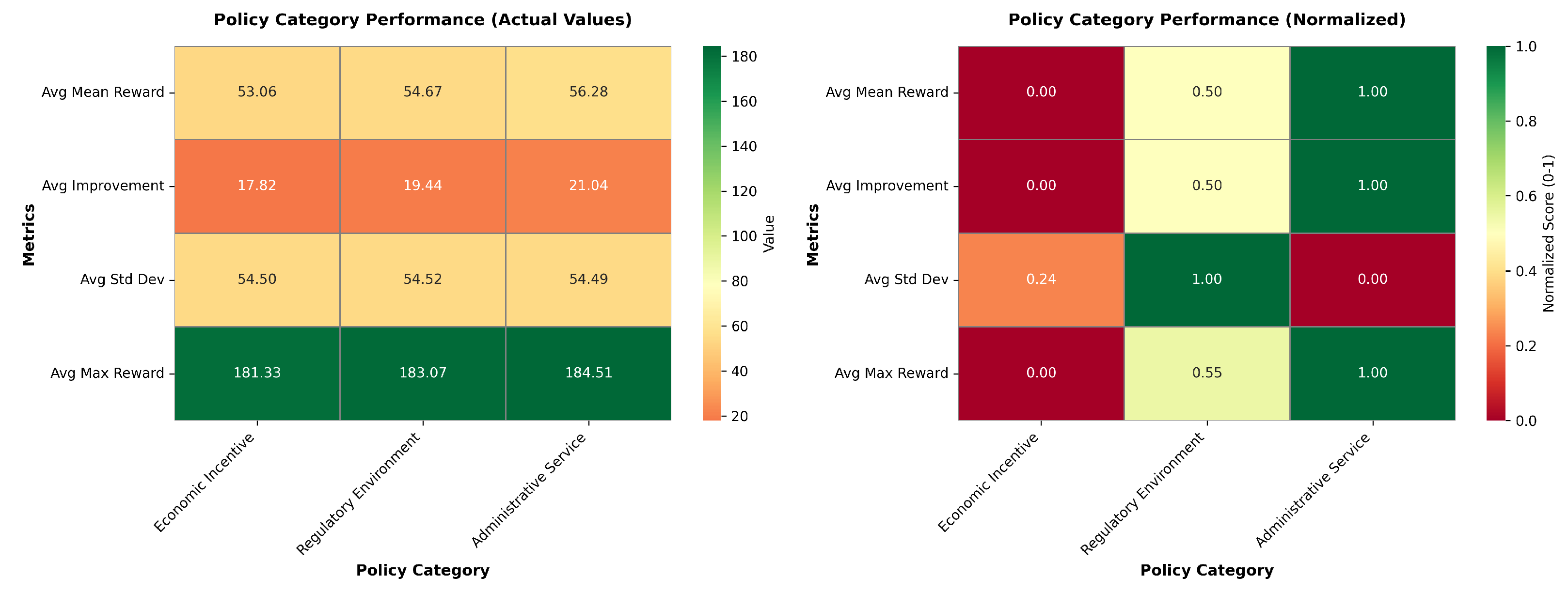

5.5. Category-Level Analysis

6. Policy Recommendations

6.1. Short-Term Priorities (0–12 Months): Establishing Economic Sustainability Foundations

6.2. Medium-Term Strategy (1–3 Years): Building Environmental–Social Excellence

6.3. Long-Term Vision (3+ Years): Sustainable Governance Leadership

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Review of Maritime Transport 2022; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, A.S.; Alex, T.L.; Nighojkar, A. Artificial Intelligence in Maritime Anomaly Detection: A Decadal Bibliometric Analysis (2014–2024). J. Inst. Eng. (India) Ser. C 2025, 106, 665–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Transport Workers’ Federation. The ITF FOC Campaign; ITF Global: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, J.; Rydbergh, T.; Stevenson, A. Decarbonizing Shipping: What Role for Flag States; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.C.; Jhang, C.W. Reducing speed and fuel transfer of the green flag incentive program in kaohsiung port taiwan. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2016, 46, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, B.; Foerster, A.; Lin, J. Net zero for the international shipping sector? An Analysis of the Implementation and Regulatory Challenges of the IMO Strategy on Reduction of GHG Emissions. J. Environ. Law 2021, 33, 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Pham, T. The impact of the flag of convenience regime into shipping industry. J. Marit. Res. JMR 2024, 21, 280–284. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, A. The customer is always right? Flags of convenience and the assembling of maritime affairs. Int. Relations 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaidea, J.I.; Piniella, F.; Rodr’ıguez-D’ıaz, E. The “Mirror Flags”: Ship registration in globalised ship breaking industry. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2016, 48, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, F. Flagging Standards: Globalization and Environmental, Safety and Labor Regulations at Sea. Glob. Environ. Politics 2008, 8, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, R.O. The history of a competitive industry. In The Global Shipping Industry; Routledge: London, UK, 1990; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit, A.K.; Pindyck, R.S. Investment Under Uncertainty; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, J.; Sanchez, R.J.; Talley, W.K. Determinants of vessel flag. Res. Transp. Econ. 2005, 12, 173–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Fan, L.; Li, K.X. Flag choice behaviour in the world merchant fleet. Transp. A Transp. Sci. 2013, 9, 429–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kavussanos, M.; Tsekrekos, A.E. The option to change the flag of a vessel. In International Handbook of Maritime Economics; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2011; pp. 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Cariou, P.; Wolff, F.-C. Do Port State Control inspections influence flag-and class-hopping phenomena in shipping? J. Transp. Econ. Policy (JTEP) 2011, 45, 155–177. [Google Scholar]

- Paris MoU. Paris MoU. Paris memorandum of understanding on port state control. In The Legal Order of the Oceans; Paris MoU: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lapeyrolerie, M.; Chapman, M.S.; Norman, K.E.A.; Boettiger, C. Deep reinforcement learning for conservation decisions. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2022, 13, 2649–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuccotto, M.; Castellini, A.; Torre, D.L.; Mola, L.; Farinelli, A. Reinforcement learning applications in environmental sustainability: A review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wen, S.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, B.; Huang, Y. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Energy Management Strategy for Green Ships Considering Photovoltaic Uncertainty. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.; Ejohwomu, O.A.; Chan, P.W. Sustainability challenges and enablers in resource recovery industries: A systematic review of the ship-recycling studies and future directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 329, 129787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Metaxas, B.N. The Economics of Tramp Shipping; The Athlone Press: London, UK, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, R.; Zhang, W.; Wang, S.; Kang, S. Deep reinforcement learning model for Multi-Ship collision avoidance decision making design implementation and performance analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Cant’on, S.; RuizdeMendoza, C.; Cervell’o-Pastor, C.; Sallent, S. Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning-Based Routing and Scheduling Models in Time-Sensitive Networking for Internet of Vehicles Communications Between Transportation Field Cabinets. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheriff, A.M.; Anantharaman, M.; Islam, R.; Nguyen, H.-O. An in-depth analysis of port state control inspections: A bibliometric analysis and systematic review. J. Int. Marit. Saf. Environ. Aff. Shipp. 2025, 9, 2454754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidheeswaran, V.; Jayakody, D.; Mulay, S.; Lo, A.; Alam, M.M.; Spadon, G. Goal-Conditioned Reinforcement Learning for Data-Driven Maritime Navigation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.01838. [Google Scholar]

- M"uller, M.; Finkeldei, F.; Krasowski, H.; Arcak, M.; Althoff, M. Falsification-Driven Reinforcement Learning for Maritime Motion Planning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.06970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, J.; Tao, H.; Liu, J.; Li, C.; Wang, K.; Xu, M. Autonomous dynamic formation for maritime target tracking using multi-agent reinforcement learning. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 154, 110904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, V.T.H. Capital solutions to promote fleet investment in shipping in countries such as Vietnam. Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 2022, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Zhang, S.; Yin, J. Structural analysis of shipping fleet capacity. J. Adv. Transp. 2018, 2018, 3854090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Fu, X.; Gao, X.; Cheng, T.; Yan, R. MSD-LLM: Predicting Ship Detention in Port State Control Inspections with Large Language Model. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.19568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, M.; Gong, F.; Wang, S.; Yan, R. Improving port state control through a transfer learning-enhanced XGBoost model. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 253, 110558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, M.-C. A Machine Learning-Based Model for Predicting High Deficiency Risk Ships in Port State Control: A Case Study of the Port of Singapore. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Tian, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, S. Equitable port state control in maritime transportation: A data-driven optimization approach. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2025, 180, 105303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitroussi, K.; Arghyrou, M.G. Institutional performance and ship registration. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2016, 85, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwunze, V. Has the Exception Become the Rule? Examining the Growing Dominance of Flags of Convenience in International Shipping. Int. J. Comp. Law Leg. Philos. (IJOCLLEP) 2021, 3, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Xiong, W.; Ouyang, X.; Chen, L. TPTrans: Vessel Trajectory Prediction Model Based on Transformer Using AIS Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.; Fablet, R. A transformer network with sparse augmented data representation and cross entropy loss for AIS-based vessel trajectory prediction. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 21596–21609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Hirayama, K.; Ren, H.; Wang, D.; Li, H. Ship anomalous behavior detection using clustering and deep recurrent neural network. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Hua, Y.; Shi, W.; Yang, Z.; Sha, M. Machine learning approaches for identifying substandard ships in port state control inspections with imbalanced data. Ocean Eng. 2025, 334, 121614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Tu, E.; Fu, X.; Yuan, G.; Han, Y. AIS Data-Driven Maritime Monitoring Based on Transformer: A Comprehensive Review. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.07374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Løvland, A.B. Predicting the Destination Port of Fishing Vessels. Master’s Thesis, UiT Norges Arktiske Universitet, Tromsø, Norway, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Alqithami, S. CH-MARL: Constrained Hierarchical Multiagent Reinforcement Learning for Sustainable Maritime Logistics. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.02060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltz, M.; Paulig, N.; Okhrin, O. 2-level reinforcement learning for ships on inland waterways: Path planning and following. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 274, 126933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.; Menzies, R.; Morarji, N.; Foster, D.; Mont, M.C.; Turkbeyler, E.; Gralewski, L. Multi-agent reinforcement learning for maritime operational technology cyber security. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.10149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Soares, C.G. Ship abnormal behaviour detection based on AIS data at the approach to ports. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 226, 111712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Weng, L.; Gao, R.; Li, Y.; Du, L. Unsupervised maritime anomaly detection for intelligent situational awareness using AIS data. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 284, 111313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontopoulos, I.; Chatzikokolakis, K.; Zissis, D.; Tserpes, K.; Spiliopoulos, G. Real-time maritime anomaly detection: Detecting intentional AIS switch-off. Int. J. Big Data Intell. 2020, 7, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Qin, X.; Pan, M.; Li, S.; Shen, H. Adaptive Temporal Reinforcement Learning for Mapping Complex Maritime Environmental State Spaces in Autonomous Ship Navigation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minßen, F.-M.; Klemm, J.; Steidel, M.; Niemi, A. Predicting vessel tracks in waterways for maritime anomaly detection. Trans. Marit. Sci. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sustainability Dimension | Policy Factors (Indicators) |

|---|---|

| Economic Sustainability | (F1) Corporate Income Tax Rate |

| (F2) Tonnage Tax Level | |

| (F3) Initial Ship Registration Fees | |

| (F4) Annual Ship Maintenance Fees | |

| (F5) Government Financial Subsidies and Incentives | |

| (F6) Favorable Financing Policies (e.g., low-interest loans) | |

| (F7) Accelerated Depreciation Policies | |

| (F8) Tax Exemptions on Crew Wages | |

| (F9) Foreign Exchange Control Policies | |

| Environmental Sustainability | (F10) Safety Inspection Standards and Frequency |

| (F11) Stringency of Environmental Regulations | |

| (F12) Ship Technical Standard Requirements | |

| (F13) Port State Control (PSC) Record and Environmental Performance | |

| (F16) Compliance Costs (e.g., environmental and safety compliance burden) | |

| (F17) Government’s Stance on International Maritime Conventions | |

| (F24) Scope of Recognized Classification Societies | |

| Social Sustainability | (F14) Crew Nationality and Labor Rights Requirements |

| (F15) Legal System and Maritime Dispute Resolution Mechanism | |

| (F18) Crisis Response and Maritime Security Capabilities | |

| (F19) Convenience and Efficiency of the Registration Process | |

| (F20) Level of Digitalization in Government Services | |

| (F21) 24/7 Emergency Response and Technical Support | |

| (F22) Multilingual Service Capability | |

| (F23) Diplomatic Protection and Consular Services | |

| (F25) Policy Stability and Predictability | |

| (F26) Communication and Consultation Mechanisms with the Industry | |

| (F27) Market Access Opportunities (e.g., cabotage rights) |

| Factor | Measurement Scale | Operationalization | Normalization Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 0–50% | Statutory corporate tax rate applicable to shipping companies | Min–Max: |

| F2 | Binary (0/1) | Availability of tonnage-based taxation option | Z-score: |

| F3 | USD/GT | One-time fee per gross tonnage for new registrations | Log: |

| F4 | USD/GT/year | Recurring annual fee per gross tonnage | Log: |

| F5 | 0–10 scale | Government subsidies as % of average vessel value (normalized) | Min–Max: |

| F6 | 0–10 scale | Access to policy bank loans (rate differential vs. market) | Min–Max: |

| F7 | Binary (0/1) | Availability of tax depreciation benefits for vessels | Min–Max: |

| F8 | 0–100% | Maximum allowed foreign equity ownership | Min–Max: |

| F9 | 0–1 (Chinn-Ito) | Inverse of capital account restrictiveness index | Direct (0–1 scale) |

| F10 | 0–100% | Annual PSC inspection rate (inspections/port calls) | Min–Max: |

| F11 | 0–10 scale | Composite score: IMO convention ratification + enforcement record | Direct (0–10 scale) |

| F12 | 0–10 scale | Classification society requirements beyond SOLAS minimum | Direct (0–10 scale) |

| F13 | 0–10 deficiencies | Average deficiencies per inspection before detention | Direct (0–10 scale) |

| F14 | 0–10 scale | MLC compliance score + additional crew welfare provisions | Direct (0–10 scale) |

| F15 | −2.5 to +2.5 | World Bank Rule of Law index (WGI) | Direct (−2.5–+2.5 scale) |

| F16 | USD/vessel/year | Estimated annual compliance costs (surveys, audits, reporting) | Direct (USD/year) |

| F17 | 0–10 scale | Extent of derogations/exemptions from international conventions | Direct (0–10 scale) |

| F18 | 0–10 scale | Inverse of security incident frequency + emergency response capability | Direct (0–10 scale) |

| F19 | Days | Average time from application to certificate issuance | Direct (Days) |

| F20 | 0–1 (EGDI) | UN E-Government Development Index score | Direct (0–1 scale) |

| F21 | 0–10 scale | Geographic coverage of registry offices + 24/7 support | Direct (0–10 scale) |

| F22 | 0–10 scale | PSC white/grey/black list status + industry perception surveys | Min–Max: |

| F23 | Number of missions | Count of embassies/consulates worldwide | Direct (Count) |

| F24 | Binary (0/1) | Acceptance of IACS-member classification societies only | Direct (Binary) |

| F25 | 0–10 scale | Inverse of regulatory change frequency (5-year rolling window) | Direct (0–10 scale) |

| F26 | 0–10 scale | Stakeholder engagement in policymaking (frequency + transparency) | Direct (0–10 scale) |

| F27 | 0–10 scale | Preferential access through bilateral shipping agreements | Direct (0–10 scale) |

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Learning Rate () | 0.001 |

| Batch Size | 32 |

| Discount Factor () | 0.95 |

| Replay Buffer Size | 10,000 |

| Target Network Update Frequency | 100 steps |

| Initial Rate () | 1.0 |

| Minimum Rate () | 0.01 |

| Exploration Decay Rate | 0.995 |

| State Dimension | 20 |

| Hidden Layer Dimension | 128 |

| Action Dimension | 3 |

| Training Episodes | 1000 |

| Evaluation Episodes | 100 |

| Random Seed | 42 |

| Economic () | 0.50 |

| Environmental () | 0.30 |

| Social () | 0.20 |

| Category | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Environment | Max Steps per Episode | 365 days |

| Discount Factor () | 0.95 | |

| Economic Volatility | 0.1 | |

| Random Seed | 42 | |

| Economic Baseline | Corporate Tax (National/FOC) | 0.25/0.05 |

| Regulatory Burden (National/FOC) | 0.8/0.3 | |

| Safety Inspection Prob. (National/FOC) | 0.1/0.4 | |

| Other Policies (F2–F9, F11–F27) | Neutral baseline | |

| RL Agent | Algorithm | DQN with Attention |

| Hidden Dimension | 128 | |

| Learning Rate | 0.001 | |

| Training Episodes | 1000 | |

| Evaluation Episodes | 100 | |

| Reward Weights | Economic () | 0.50 |

| Environmental () | 0.30 | |

| Social () | 0.20 |

| Rank | Policy | Mean | Improv. | Std Dev | Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reward | Level | ||||

| - | Baseline | 35.24 | 0.00 | 54.53 | HIGH |

| 1 | F1 Low Corporate Income Tax | 166.60 | 131.37 | 54.39 | HIGH |

| 2 | F5 High Financial Subsidy | 108.30 | 73.06 | 54.51 | HIGH |

| 3 | F10 High Safety Inspection Freq | 93.58 | 58.35 | 54.52 | HIGH |

| 4 | F25 High Policy Stability | 79.00 | 43.77 | 54.55 | HIGH |

| 5 | F19 High Registration Convenience | 78.98 | 43.74 | 54.47 | HIGH |

| 6 | F12 High Tech Standard | 49.94 | 14.71 | 54.52 | HIGH |

| 7 | F8 Crew Wage Tax Exemption | 49.89 | 14.65 | 54.51 | HIGH |

| 8 | F27 High Market Access | 49.84 | 14.60 | 54.42 | HIGH |

| 9 | F7 Accelerated Depreciation | 49.83 | 14.60 | 54.53 | HIGH |

| 10 | F21 Emergency Support 24 7 | 49.83 | 14.59 | 54.47 | HIGH |

| 11 | F16 Low Compliance Cost | 49.82 | 14.59 | 54.53 | HIGH |

| 12 | F14 High Crew Qualification | 49.82 | 14.58 | 54.56 | HIGH |

| 13 | F17 Positive Convention Stance | 49.81 | 14.58 | 54.45 | HIGH |

| 14 | F20 High Service Digitalization | 49.81 | 14.57 | 54.57 | HIGH |

| 15 | F18 High Crisis Response | 49.81 | 14.57 | 54.55 | HIGH |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, G.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Z. Deep Learning-Enabled Policy Optimization for Sustainable Ship Registry Selection. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10836. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310836

Xie G, Liang Y, Zhang B, Zhang Z. Deep Learning-Enabled Policy Optimization for Sustainable Ship Registry Selection. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10836. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310836

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Gengquan, Yarong Liang, Bin Zhang, and Zihui Zhang. 2025. "Deep Learning-Enabled Policy Optimization for Sustainable Ship Registry Selection" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10836. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310836

APA StyleXie, G., Liang, Y., Zhang, B., & Zhang, Z. (2025). Deep Learning-Enabled Policy Optimization for Sustainable Ship Registry Selection. Sustainability, 17(23), 10836. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310836