Ultrasound-Induced Embedded-Silica Migration to Biochar Surface: Applications in Agriculture and Environmental Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

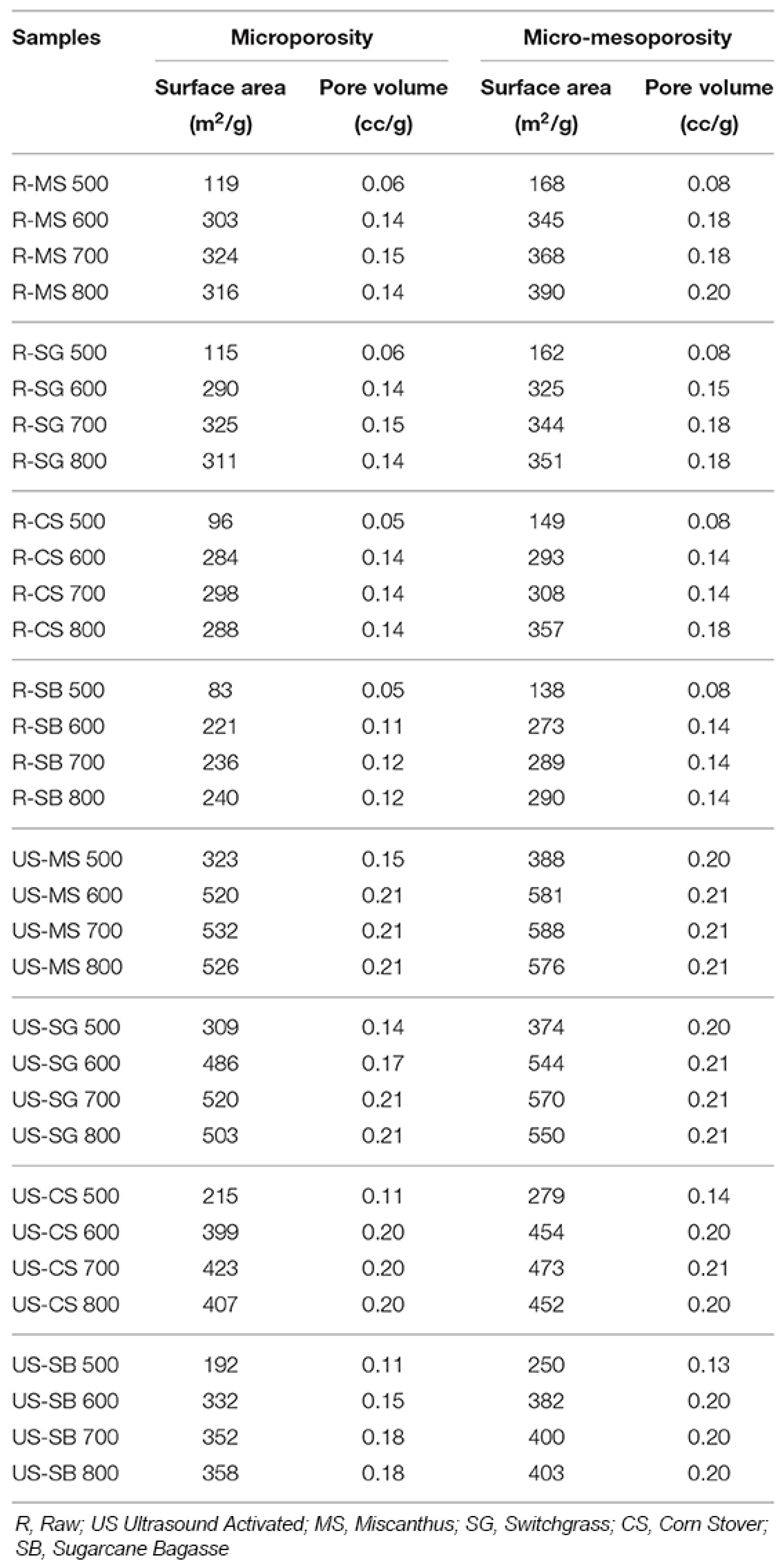

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussions

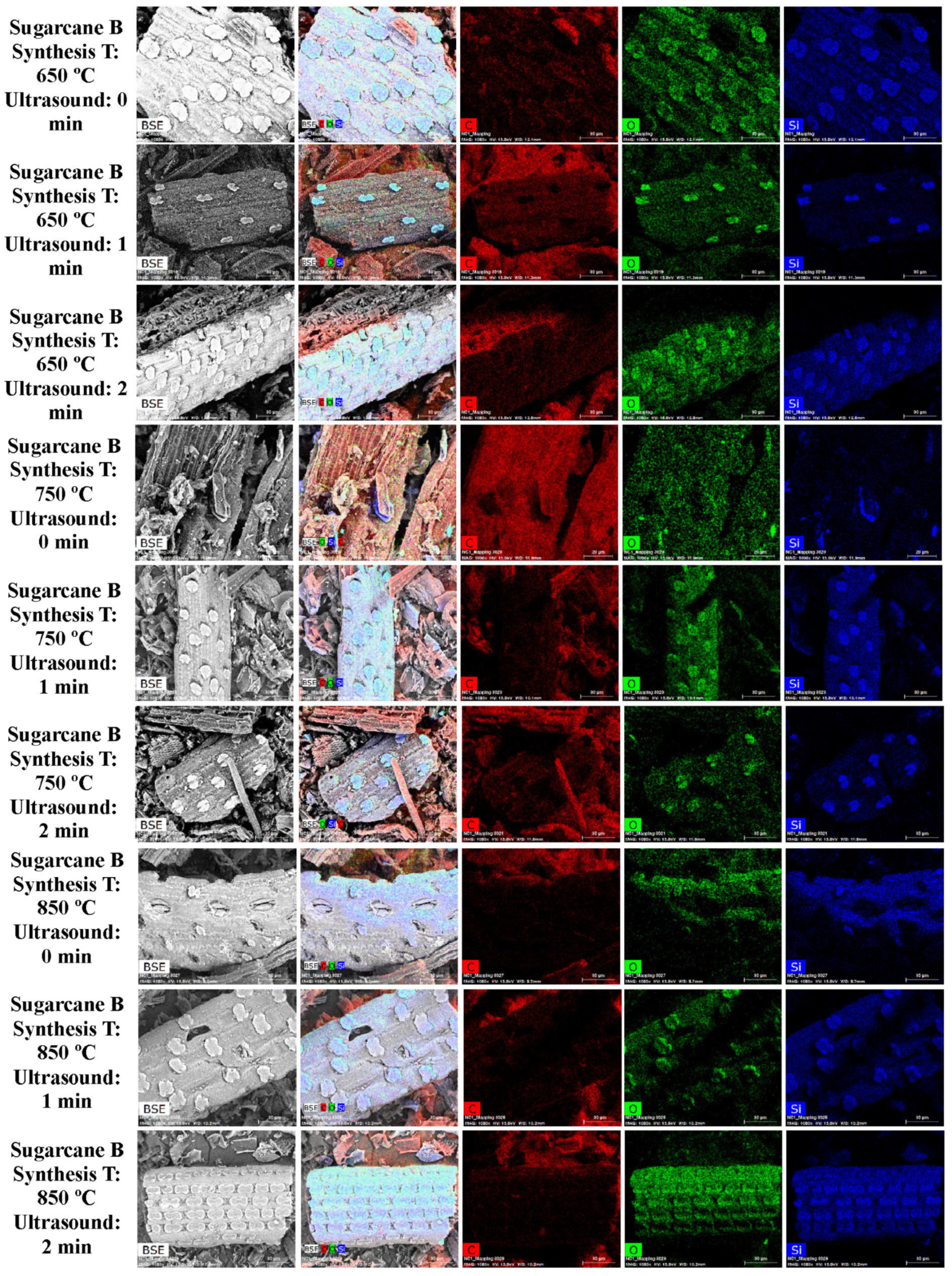

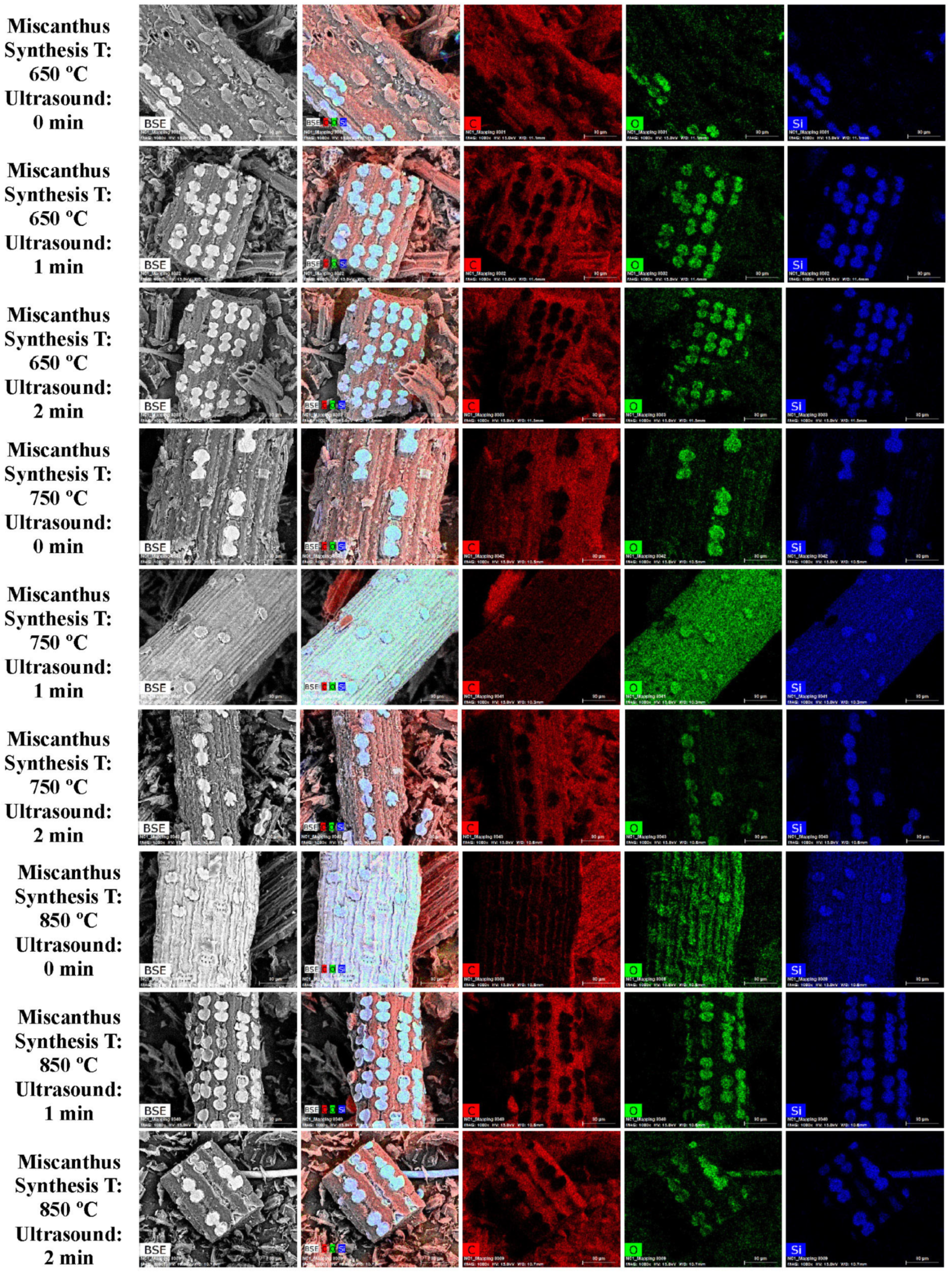

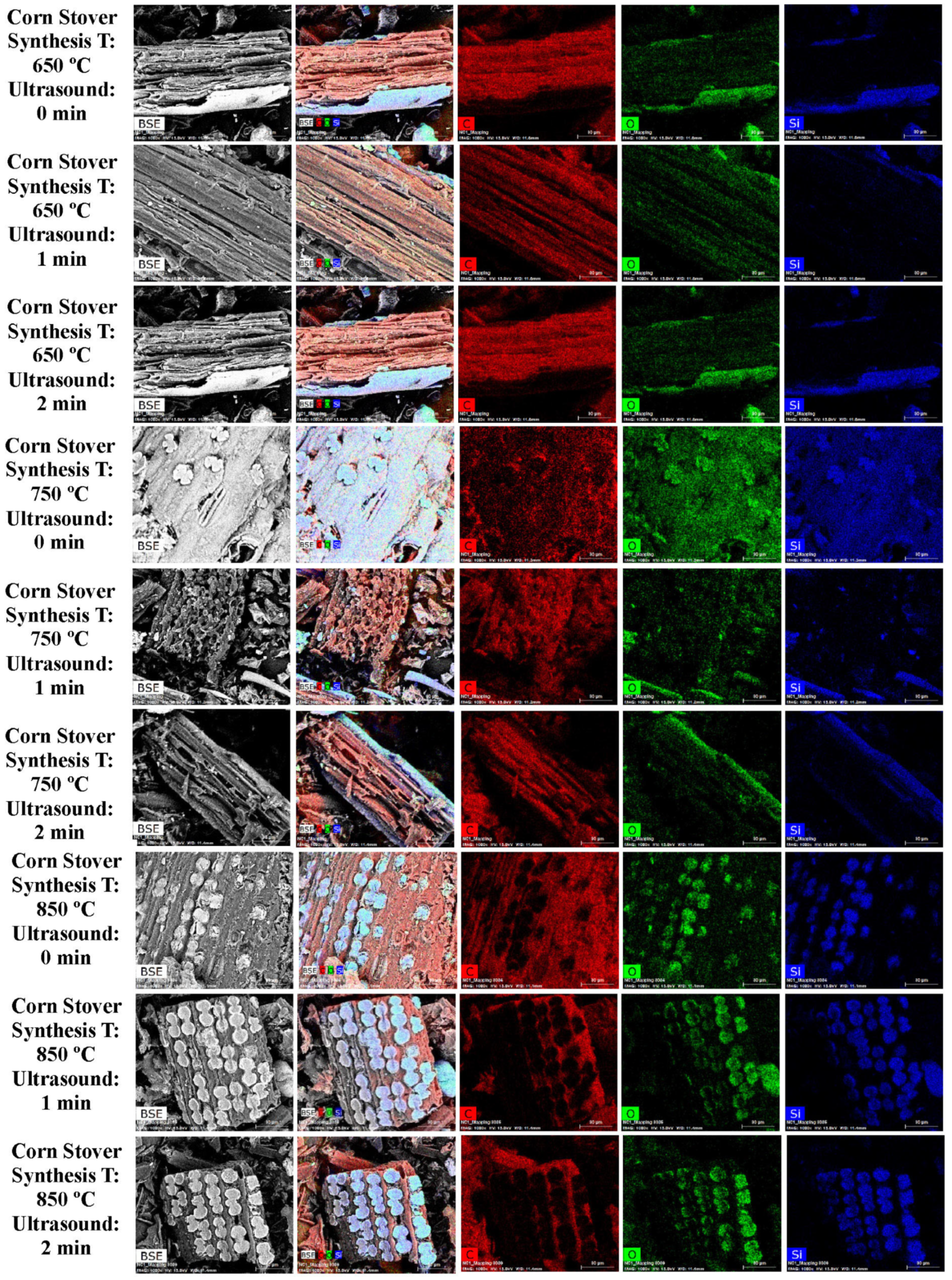

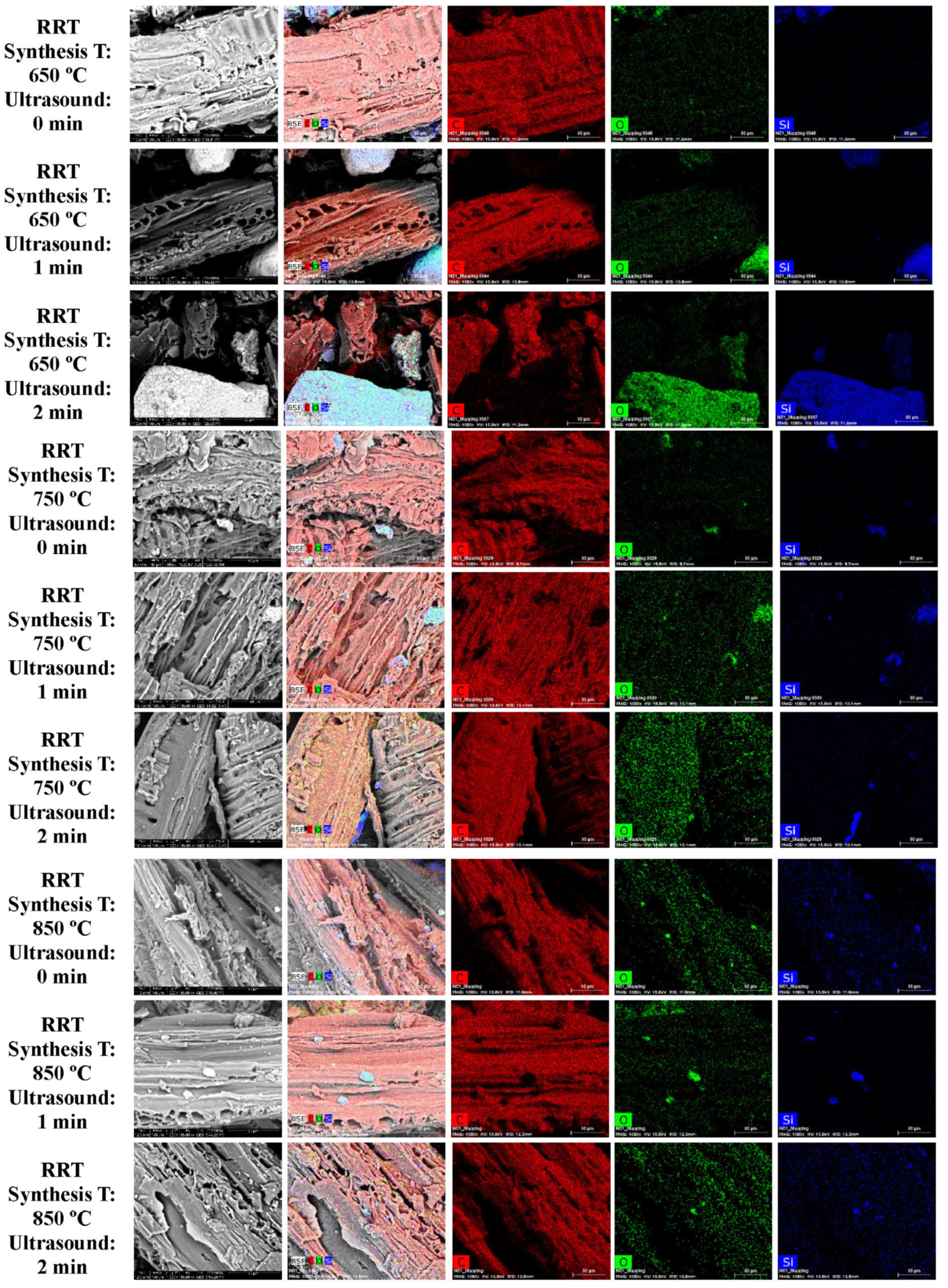

3.1. SEM and EDS Analysis

3.2. FTIR Analysis

3.3. Impact of Ultrasound on Si-Containing Functional Groups in Biochar

3.4. Applications of Pristine and Engineered Biochar

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| SG | Sugarcane Bagasse |

| MIS | Miscanthus |

| WS | Wheat Straw |

| CS | Corn Stover |

| RRTs | Railroad Ties |

| VOCs | Volatile Organic Compounds |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| EDS | Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

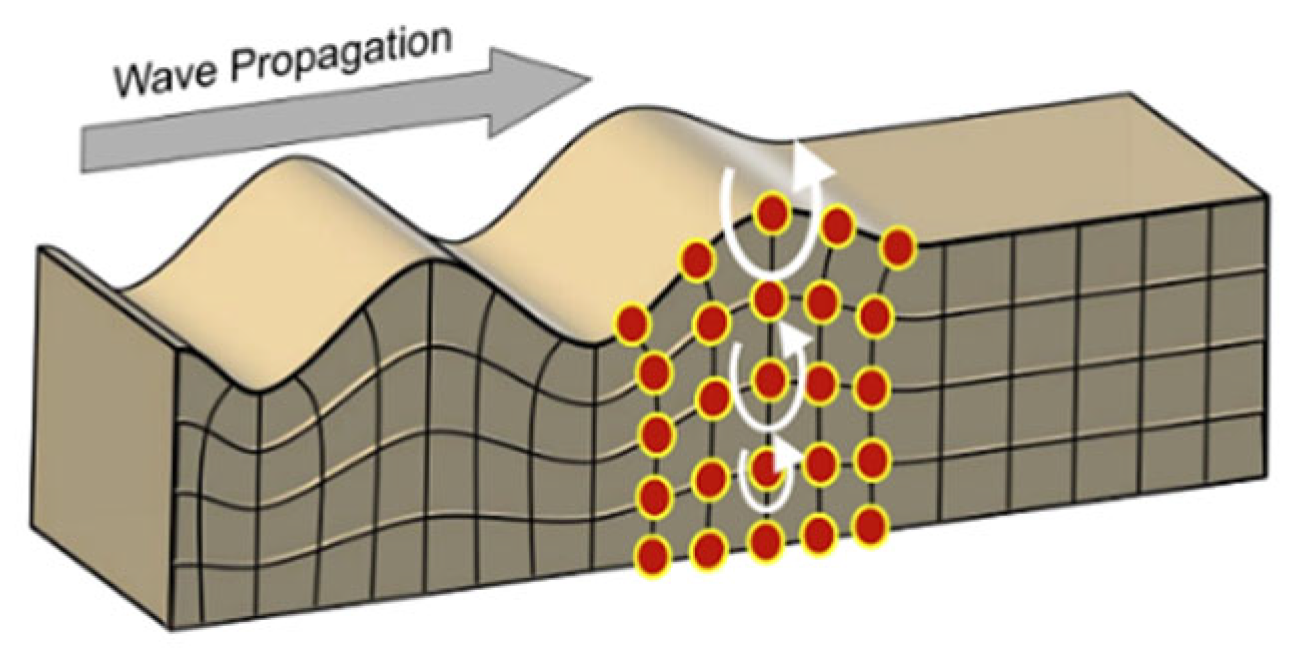

| SAWs | Surface Acoustic Waves |

| SRWs | Surface Rayleigh Waves |

| ITZ | Interfacial Transition Zone |

| PAHs | Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons |

References

- Raza, M.H.; Abid, M.; Faisal, M.; Yan, T.; Akhtar, S.; Adnan, K.M.M. Environmental and Health Impacts of Crop Residue Burning: Scope of Sustainable Crop Residue Management Practices. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Ma, J.; Song, S.; Ling, Z.; Macdonald, R.W.; Gao, H.; Tao, S.; Shen, H.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; et al. Health and environmental consequences of crop residue burning correlated with increasing crop yields midst India’s Green Revolution. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2022, 5, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, F.; Zhang, C.; Shi, Y.; Jin, G.; Yuan, S. Preparation of nano-silica materials: The concept from wheat straw. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2010, 356, 2781–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Ng, K.H.; Cheng, C.K.; Cheng, Y.W.; Chong, C.C.; Vo, D.-V.N.; Witoon, T.; Ismail, M.H. Biomass-derived carbon-based and silica-based materials for catalytic and adsorptive applications- An update since 2010. Chemosphere 2022, 287, 132222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedayati, A.; Lindgren, R.; Skoglund, N.; Boman, C.; Kienzl, N.; Öhman, M. Ash Transformation during Single-Pellet Combustion of Agricultural Biomass with a Focus on Potassium and Phosphorus. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 1449–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Deng, P.; Zhang, Z. Application of silica-rich biomass ash solid waste in geopolymer preparation: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 356, 129142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Paredes, C.A.; Rodríguez-Linzán, I.; Saquete, M.D.; Luque, R.; Osman, S.M.; Boluda-Botella, N.; Joan Manuel, R.-D. Silica-derived materials from agro-industrial waste biomass: Characterization and comparative studies. Environ. Res. 2023, 231, 116002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, S.V.; Baxter, D.; Andersen, L.K.; Vassileva, C.G. An overview of the chemical composition of biomass. Fuel 2010, 89, 913–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Dai, Y.; Yang, H.; Xiong, Q.; Wang, K.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, S. A Review of Recent Advances in Biomass Pyrolysis. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 15557–15578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Piao, Y.; Wang, R.; Su, Y.; Liu, N.; Lei, Y. Nonmetal function groups of biochar for pollutants removal: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 8, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Xu, Y.; Chen, B. Environmental Effects of Silicon within Biochar (Sichar) and Carbon–Silicon Coupling Mechanisms: A Critical Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 13570–13582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puri, L.; Hu, Y.; Naterer, G. Critical review of the role of ash content and composition in biomass pyrolysis. Front. Fuels 2024, 2, 1378361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, T.C.; Rajamma, R.; Soares, D.; Silva, A.S.; Ferreira, V.M.; Labrincha, J.A. Use of biomass fly ash for mitigation of alkali-silica reaction of cement mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 26, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Zi, C.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhao, W. Production of biosilica nanoparticles from biomass power plant fly ash. Waste Manag. 2020, 105, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhou, C.; Fang, H.; Zhu, W.; Shi, J.; Liu, G. Synthesis of ordered mesoporous silica from biomass ash and its application in CO2 adsorption. Environ. Res. 2023, 231, 116070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Peng, N.; Sun, J.; Lu, G.; Chen, M.; Deng, F.; Dou, R.; Nie, L.; Zhong, Y. Synthesis of silica-composited biochars from alkali-fused fly ash and agricultural wastes for enhanced adsorption of methylene blue. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 729, 139055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, R.; Sajjadi, B.; Chen, W.-Y.; Mattern, D.L.; Hammer, N.; Raman, V.; Dorris, A. Effect of Pyrolysis Temperature on PhysicoChemical Properties and Acoustic-Based Amination of Biochar for Efficient CO2 Adsorption. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, A.; Pourfattah, F.; Miklós Szilágyi, I.; Afrand, M.; Żyła, G.; Seon Ahn, H.; Wongwises, S.; Minh Nguyen, H.; Arabkoohsar, A.; Mahian, O. Effect of sonication characteristics on stability, thermophysical properties, and heat transfer of nanofluids: A comprehensive review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019, 58, 104701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.; Hedberg, J.; Blomberg, E.; Wold, S.; Odnevall Wallinder, I. Effect of sonication on particle dispersion, administered dose and metal release of non-functionalized, non-inert metal nanoparticles. J. Nanopart. Res. 2016, 18, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, L.; Machado, P.; Johnson, E. Elemental Maps to Dye for: Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectrometry Facilitates a Better Understanding of the Contrast Mechanisms in Common Electron Microscopy Stains. Microsc. Microanal. 2023, 29 (Suppl. S1), 1185–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, W.; Zhao, Z.; Musoke, F.S.N.; Wu, X. Ultrasonic Activated Biochar and Its Removal of Harmful Substances in Environment. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoo, D.Y.; Low, Z.L.; Low, D.Y.S.; Tang, S.Y.; Manickam, S.; Tan, K.W.; Ban, Z.H. Ultrasonic cavitation: An effective cleaner and greener intensification technology in the extraction and surface modification of nanocellulose. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022, 90, 106176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savkina, R.K.; Gudymenko, A.I.; Kladko, V.P.; Korchovyi, A.A.; Nikolenko, A.S.; Smirnov, A.B.; Stara, T.R.; Strelchuk, V.V. Silicon Substrate Strained and Structured via Cavitation Effect for Photovoltaic and Biomedical Application. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albanese, L.; Baronti, S.; Liguori, F.; Meneguzzo, F.; Barbaro, P.; Vaccari, F.P. Hydrodynamic cavitation as an energy efficient process to increase biochar surface area and porosity: A case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananda, A.A. Propagation of Rayleigh Waves in Thin-Films. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Physics at W&M University (William & Mary), Williamsburg, VA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, M.F. On Rayleigh Waves and Related Propagating Acoustic Waves. In Rayleigh-Wave Theory and Application; Ash, E.A., Paige, E.G.S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Young, R.J.; Backes, C.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhukov, A.A.; Tillotson, E.; Conlan, A.P.; Ding, F.; Haigh, S.J. Mechanisms of Liquid-Phase Exfoliation for the Production of Graphene. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 10976–10985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosevich, Y.A.; Syrkin, E.S.; Kossevich, A.M. Vibrations localized near surfaces and interfaces in nontraditional crystals. Prog. Surf. Sci. 1997, 55, 59–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, P. Surface Acoustic Waves in Materials Science. Phys. Today 2002, 55, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakslee, O.L.; Proctor, D.G.; Seldin, E.J.; Spence, G.B.; Weng, T. Elastic constants of compression-annealed pyrolytic graphite. J. Appl. Phys. 1970, 41, 3373–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, D.; Saroha, A.K. Effect of Pyrolysis Temperature on Chemical Composition of Biochar Obtained from Pyrolysis of Rice Straw. Chem. Eng. Process Tech. 2022, 7, 1062. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Su, Q.; Xiang, L.; Yuan, Y.; Tu, S. Effect of Pyrolysis Temperature on the Sorption of Cd(II) and Se(IV) by Rice Husk Biochar. Plants 2022, 11, 3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; O’Connor, D.; Zhang, J.; Peng, T.; Shen, Z.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Hou, D. Effect of pyrolysis temperature, heating rate, and residence time on rapeseed stem derived biochar. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindo, K.; Mizumoto, H.; Sawada, Y.; Sanchez-Monedero, M.A.; Sonoki, T. Physical and chemical characterization of biochars derived from different agricultural residues. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 6613–6621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.A.E.; Rodrigues, L.C.; Coradin, V.T.R.; Okino, E.Y.A.; Souza, M.R.d. Silica content of 36 Brazilian tropical wood species. Holzforschung 2013, 67, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjaer, E.D.; Kajornsrichon, S.; Lauridsen, E.B. Heartwood, Calcium and Silica Content in Five Provenances of Teak (Tectona grandis L.) 1. Silvae Genet. 1999, 48, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Marchewka, J.; Jeleń, P.; Rutkowska, I.; Bezkosty, P.; Sitarz, M. Chemical Structure and Microstructure Characterization of Ladder-Like Silsesquioxanes Derived Porous Silicon Oxycarbide Materials. Materials 2021, 14, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritz, M. Infrared and Raman Spectroscopy of Mullite Ceramics Synthesized from Fly Ash and Kaolin. Minerals 2023, 13, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mysen, B. Solution mechanisms of COHN fluids in melts to upper mantle temperature, pressure, and redox conditions. Am. Mineral. 2018, 103, 1780–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellerbrock, R.H.; Stein, M.; Schaller, J. Comparing silicon mineral species of different crystallinity using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Front. Environ. Chem. 2024, 5, 1462678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinová, A.; Huran, J.; Sasinková, V.; Perný, M.; Šály, V.; Packa, J. FTIR spectroscopy of silicon carbide thin films prepared by PECVD technology for solar cell application. In Proceedings of the Reliability of Photovoltaic Cells, Modules, Components, and Systems VIII, San Diego, CA, USA, 23 September 2015; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2015; Volume 9563. [Google Scholar]

- Launer, P.; Arkles, B. Infrared Analysis of Organosilicon Compounds. In Silicon Compounds: Silanes & Silicones; Gelest Inc.: Morrisville, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 175–178. [Google Scholar]

- Jeleń, P.; Bik, M.; Nocuń, M.; Gawęda, M.; Długoń, E.; Sitarz, M. Free carbon phase in SiOC glasses derived from ladder-like silsesquioxanes. J. Mol. Struct. 2016, 1126, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handke, M.; Handke, B.; Kowalewska, A.; Jastrzębski, W. New polysilsesquioxane materials of ladder-like structure. J. Mol. Struct. 2009, 924–926, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrokh Abadi, M.H. Effects of Annealing Temperature on Infrared Spectra of SiO2 Extracted from Rice Husk. J. Ceram. Sci. Technol. 2014, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Oufakir, A.; Khouchaf, L.; Elaatmani, M.; Louarn, G.; Fraj, A. Study of structural short order and surface changes of SiO2 compounds. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 149, 01041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongzhen, T.; Wang, A.; Chen, J.; Jiang, X.-Z.; Shi, J.; Zhang, C.; Mei, Y.; Wang, B. Treatment Effect Modeling for FTIR Signals Subject to Multiple Sources of Uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2021, 19, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaubey, A.K.; Pratap, T.; Preetiva, B.; Patel, M.; Singsit, J.S.; Pittman, C.U., Jr.; Mohan, D. Definitive Review of Nanobiochar. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 12331–12379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Chen, B. Biochar Impacts on Soil Silicon Dissolution Kinetics and their Interaction Mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Yang, X.; Jia, X.; Cai, M.; Bao, Y. Preparation of Si–Mn/biochar composite and discussions about characterizations, advances in application and adsorption mechanisms. Chemosphere 2021, 281, 130946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lura, P.; Wyrzykowski, M.; Tang, C.; Lehmann, E. Internal curing with lightweight aggregate produced from biomass-derived waste. Cem. Concr. Res. 2014, 59, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.; Gupta, S.; Pang, S.D.; Kua, H.W. Waste Valorisation using biochar for cement replacement and internal curing in ultra-high performance concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 238, 117876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Chen, H.; Zhang, R.; Liu, L. Characterization of the wall effect of concrete via random packing of polydispersed superball-shaped aggregates. Mater. Charact. 2019, 154, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Dai, J.; Fu, Z.; Li, C.; Wen, Y.; Jia, M.; Wang, Y.; Shi, K. Biochar for asphalt modification: A case of high-temperature properties improvement. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 804, 150194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Sun, M.; Geng, N.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Pan, H.; Yang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Lou, Y.; Zhuge, Y. A novel and recyclable silica gel-modified biochar to remove cadmium from wastewater: Model application and mechanism exploration. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 281, 116608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Ekanayake, A.; Tyagi, V.K.; Vithanage, M.; Singh, R.; Rao, Y.R.S. Emerging contaminants in polluted waters: Harnessing Biochar’s potential for effective treatment. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Bhattu, M.; Liew, R.K.; Verma, M.; Brar, S.K.; Bechelany, M.; Jadeja, R. Transforming rice straw waste into biochar for advanced water treatment and soil amendment applications. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 37, 103932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, V.K.H.; Nguyen, T.P.; Tran, T.C.P.; Nguyen, T.T.N.; Duong, T.N.; Nguyen, V.T.; Liu, C.; Nguyen, D.D.; Nguyen, X.C. Biochar-based fixed filter columns for water treatment: A comprehensive review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamali, M.; Appels, L.; Kwon, E.E.; Aminabhavi, T.M.; Dewil, R. Biochar in water and wastewater treatment—A sustainability assessment. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 420, 129946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, A.; Divyapriya, G.; Srivastava, V.; Laiju, A.R.; Nidheesh, P.V.; Kumar, M.S. Conversion of sewage sludge into biochar: A potential resource in water and wastewater treatment. Environ. Res. 2021, 194, 110656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Yang, X.; Ahmad, S.; Li, X.; Ri, C.; Tang, J.; Ellam, R.M.; Song, Z. Silicon (Si) modification of biochars from different Si-bearing precursors improves cadmium remediation. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 457, 141194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zheng, L.; Wang, S.-L.; Wu, Z.; Wu, W.; Niazi, N.K.; Shaheen, S.M.; Rinklebe, J.; Bolan, N.; Ok, Y.S.; et al. Sorption mechanisms of lead on silicon-rich biochar in aqueous solution: Spectroscopic investigation. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 672, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Lu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, S.; Duan, X.; Qiu, G. Mechanisms for synergistically enhancing cadmium remediation performance of biochar: Silicon activation and functional group effects. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 404, 130913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Tie, B.; Lei, M.; Wei, X.; Peng, O.; Du, H. Silicate-modified oiltea camellia shell-derived biochar: A novel and cost-effective sorbent for cadmium removal. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 281, 125390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zama, E.F.; Reid, B.J.; Sun, G.-X.; Yuan, H.-Y.; Li, X.-M.; Zhu, Y.-G. Silicon (Si) biochar for the mitigation of arsenic (As) bioaccumulation in spinach (Spinacia oleracean) and improvement in the plant growth. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 189, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafin, J.; Narkiewicz, U.; Morawski, A.W.; Wróbel, R.J.; Michalkiewicz, B. Highly microporous activated carbons from biomass for CO2 capture and effective micropores at different conditions. J. CO2 Util. 2017, 18, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Sun, Y.; Liu, L. Recent advances in biochar-based adsorbents for CO2 capture. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2022, 4, 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, S.; Sajjadi, B. Non-thermal plasma enhanced catalytic conversion of methane into value added chemicals and fuels. J. Energy Chem. 2024, 97, 265–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, Z.; Jeelani, S.; Rangari, V. Low temperature plasma treatment of rice husk derived hybrid silica/carbon biochar using different gas sources. Mater. Lett. 2021, 292, 129678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.; Sajjadi, B. Sustainable conversion of natural gas to hydrogen using transition metal carbides. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 90, 61–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ji, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, S.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Wu, C. The Application of Biochar for CO2 Capture: Influence of Biochar Preparation and CO2 Capture Reactors. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 17168–17181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Pan, Y.; Liu, S. Power ultrasound and its applications: A state-of-the-art review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020, 62, 104722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vouters, M.; Rumeau, P.; Tierce, P.; Costes, S. Ultrasounds: An industrial solution to optimise costs, environmental requests and quality for textile finishing. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2004, 11, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, R.; Sajjadi, B.; Mattern, D.L.; Chen, W.-Y.; Zubatiuk, T.; Leszczynska, D.; Leszczynski, J.; Egiebor, N.O.; Hammer, N. Ultrasound cavitation intensified amine functionalization: A feasible strategy for enhancing CO2 capture capacity of biochar. Fuel 2018, 225, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, R.; Sajjadi, B.; Chen, W.-Y.; Mattern, D.L.; Hammer, N.; Raman, V.; Dorris, A. Impact of Biomass Sources on Acoustic-Based Chemical Functionalization of Biochars for Improved CO2 Adsorption. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 8608–8627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.N. Potential use of silica-rich biochar for the formulation of adaptively controlled release fertilizers: A mini review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 307, 127188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Xiang, L.; Su, Q.; Liu, Z.; Wu, W.; Huang, Y.; Tu, S. Silicon-Rich Biochar Detoxify Multiple Heavy Metals in Wheat by Regulating Oxidative Stress and Subcellular Distribution of Heavy Metal. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Miscanthus (wt%) | Corn Stover (wt%) | Sugarcane Bagasse (wt%) | Wheat Straw (wt%) | Railroad Ties (wt%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed carbon | 13.06 | 16.7 | 13.41 | 13.89 | 18.9 |

| Volatile | 85.53 | 79.0 | 76.02 | 77.04 | 90.9 |

| Ash | 1.40 | 4.3 | 10.56 | 9.07 | 0.4 |

| Carbon | 50.64 | 48.7 | 45.24 | 45.02 | 61.3 |

| Hydrogen | 5.85 | 5.7 | 5.38 | 5.90 | 6.6 |

| Nitrogen | 0.21 | 0.7 | 0.36 | 1.06 | 0.4 |

| Oxygen | 41.88 | - | 38.41 | 38.82 | 28.8 |

| Sulfur | 0.01 | - | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.1 |

| Compound | Miscanthus (wt%) | Corn Stover (wt%) | Sugarcane Bagasse (wt%) | Wheat Straw (wt%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al2O3 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 7.20 | 2.77 |

| CaO | 18.34 | 8.99 | 2.74 | 10.83 |

| Fe2O3 | 1.20 | 1.12 | 2.40 | 2.99 |

| K2O | 6.44 | 26.38 | 4.46 | 15.45 |

| MgO | 9.03 | 6.09 | 1.30 | 2.69 |

| MnO | 1.11 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| Na2O | 0.18 | 0.08 | 1.30 | 1.16 |

| P2O5 | 3.58 | 2.79 | 0.95 | 2.15 |

| SiO2 | 52.31 | 51.99 | 79.19 | 58.16 |

| TiO2 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.40 | 0.11 |

| SO3 | 3.15 | 2.20 | 0.57 | 2.34 |

| Sample | Element | Atomic % |

|---|---|---|

| WS-850-0 | Silicon | 2.47346 |

| WS-850-1 | Silicon | 22.67204 |

| WS-850-2 | Silicon | 28.19271 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdullah, M.; Baig, S.; Martinez, M.P.H.; Sajjadi, B. Ultrasound-Induced Embedded-Silica Migration to Biochar Surface: Applications in Agriculture and Environmental Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10813. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310813

Abdullah M, Baig S, Martinez MPH, Sajjadi B. Ultrasound-Induced Embedded-Silica Migration to Biochar Surface: Applications in Agriculture and Environmental Sustainability. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10813. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310813

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdullah, Muhammad, Shanza Baig, Maria Paula Hernández Martinez, and Baharak Sajjadi. 2025. "Ultrasound-Induced Embedded-Silica Migration to Biochar Surface: Applications in Agriculture and Environmental Sustainability" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10813. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310813

APA StyleAbdullah, M., Baig, S., Martinez, M. P. H., & Sajjadi, B. (2025). Ultrasound-Induced Embedded-Silica Migration to Biochar Surface: Applications in Agriculture and Environmental Sustainability. Sustainability, 17(23), 10813. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310813