Declining Crop Yield Sensitivity to Drought and Its Environmental Drivers in the North China Plain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

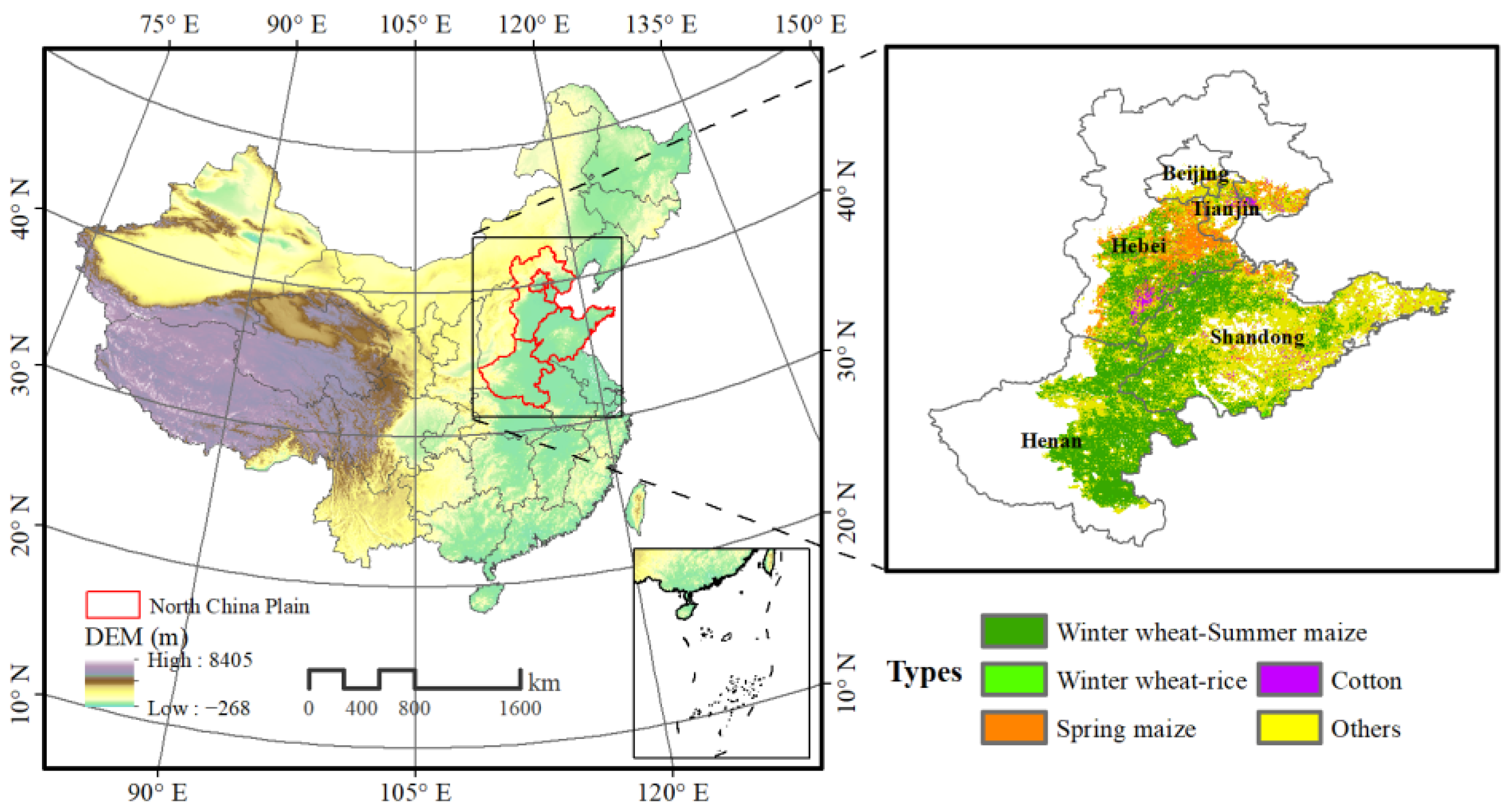

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.2.1. Wheat Yield Data

2.2.2. Multi-Scale SPEI and Climate Data

2.2.3. Atmospheric CO2 and Nitrogen Fertilizer Application Data

2.2.4. GRACE-Based Groundwater Storage Data

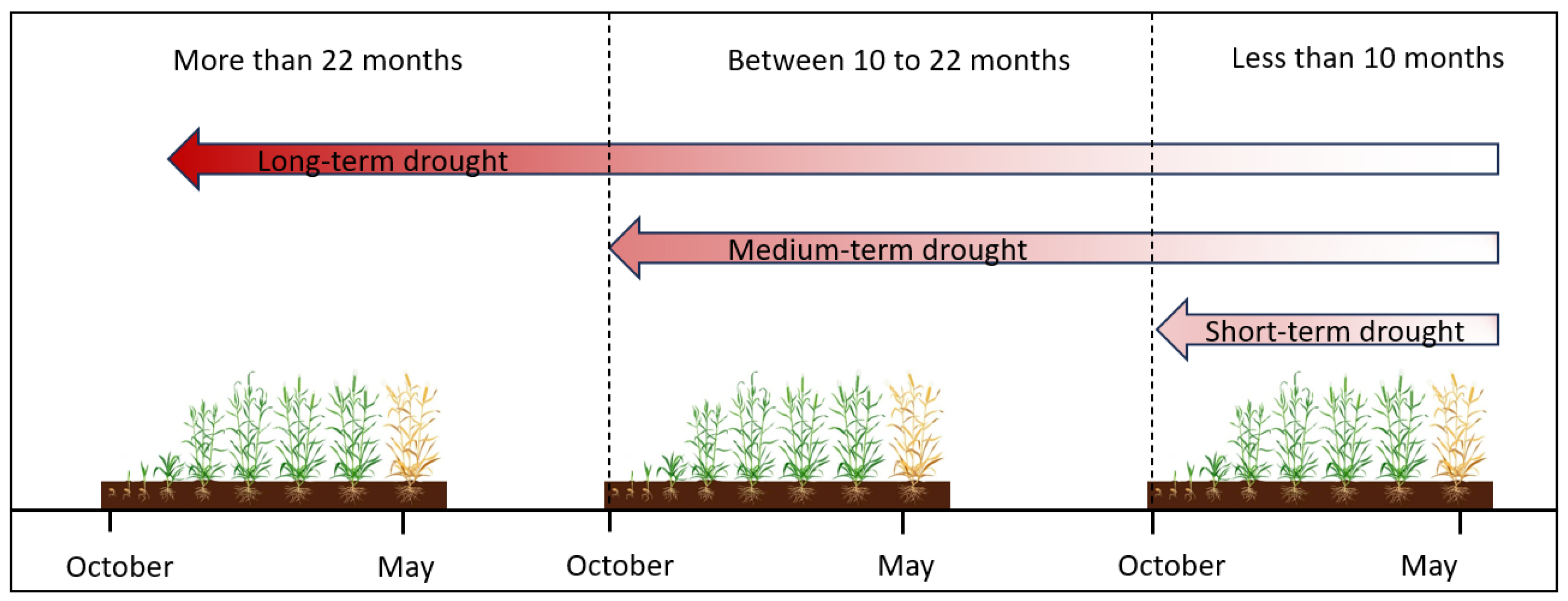

2.3. Life Cycle-Based Definition of Drought Durations

2.4. Statistical Methods

3. Results

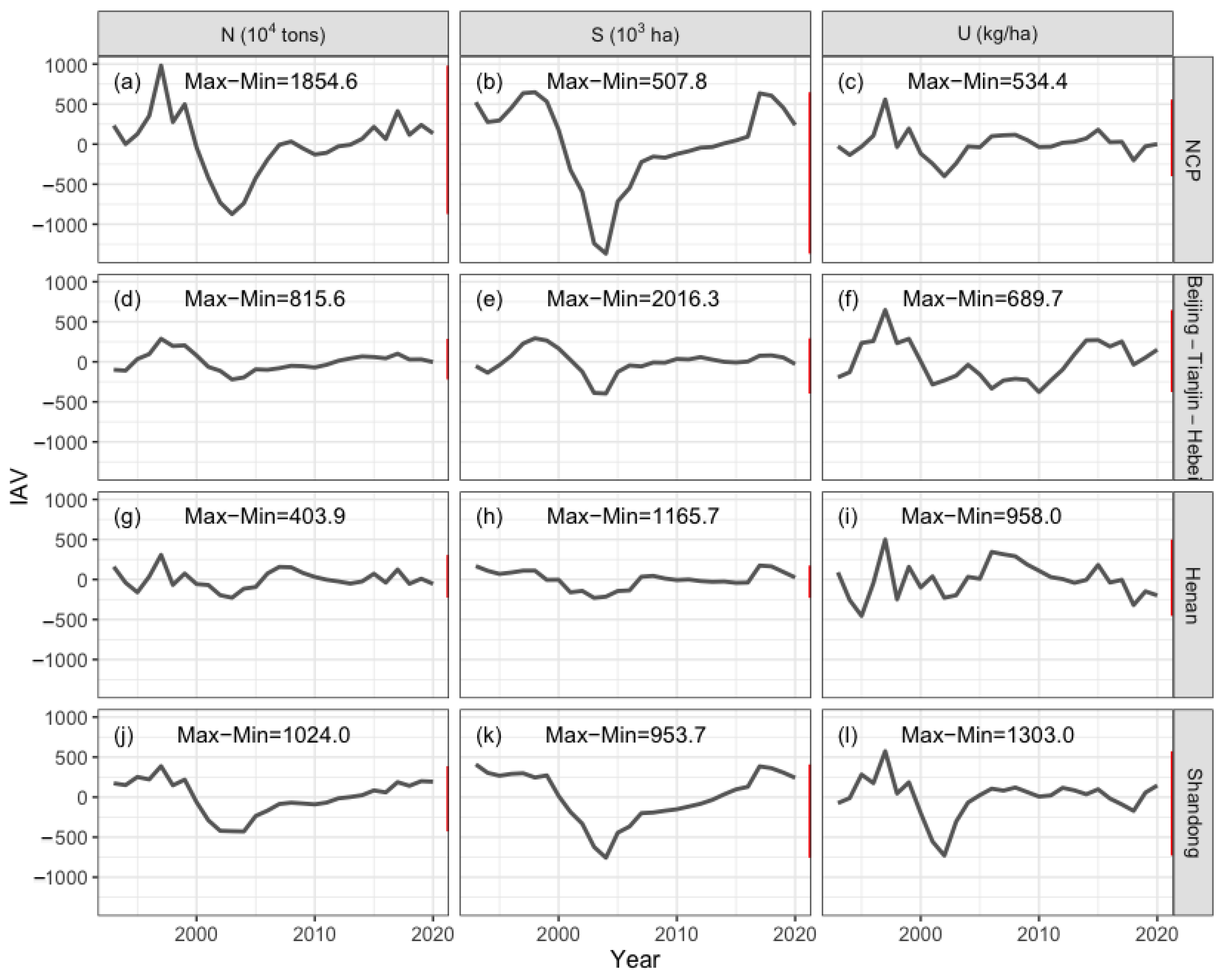

3.1. Wheat Yield Anomalies Across the NCP

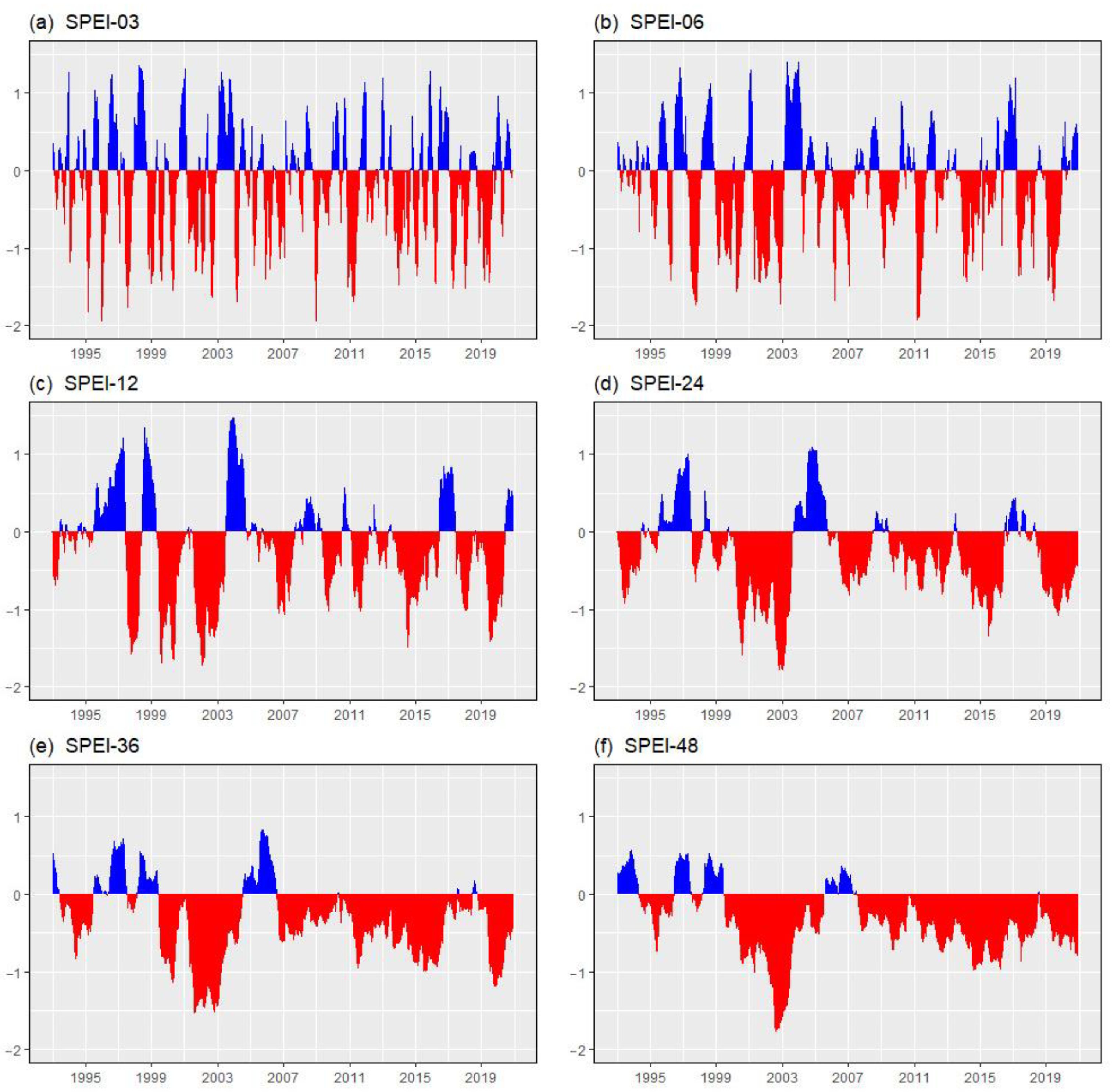

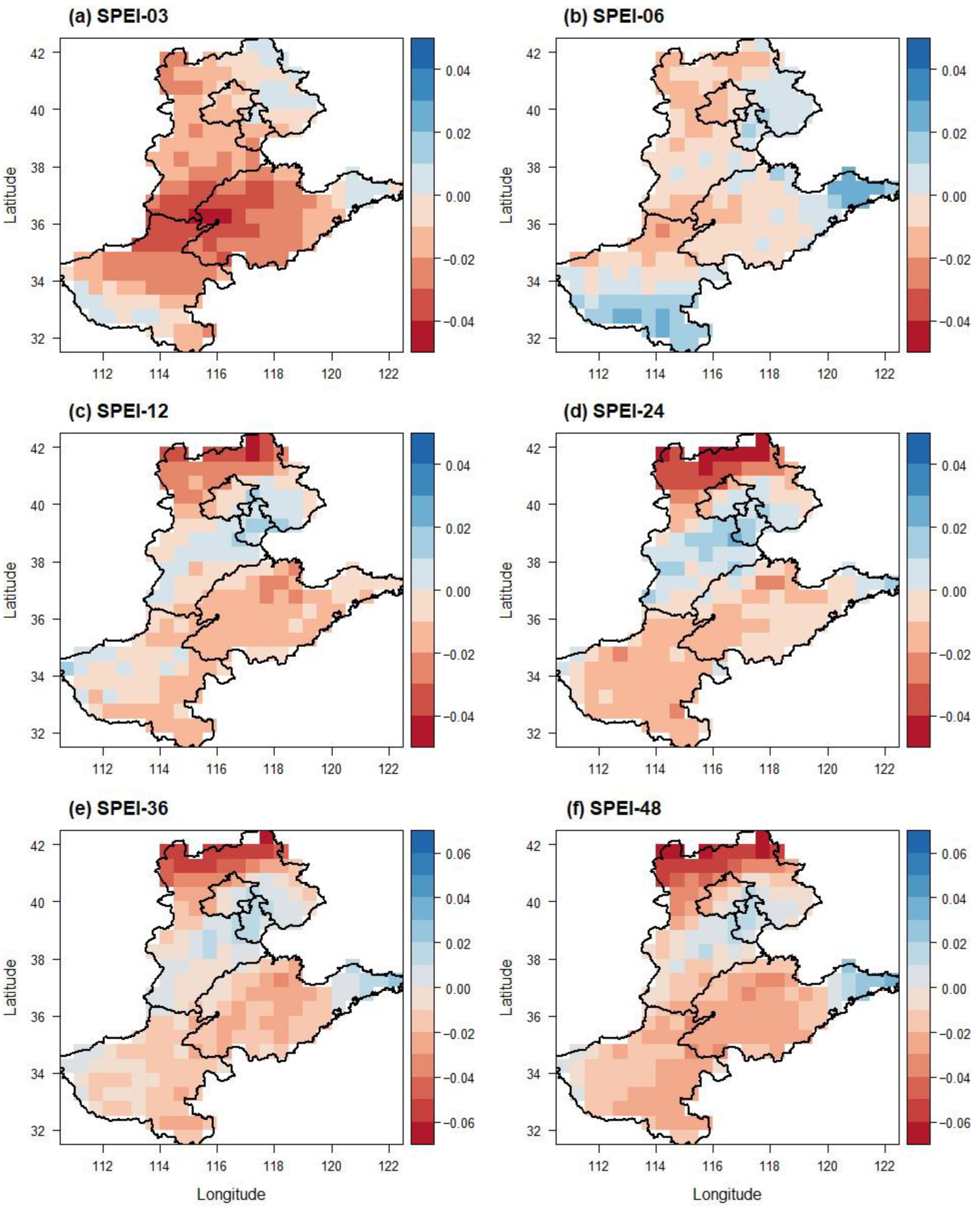

3.2. Multi-Scale SPEI Changes Across the NCP

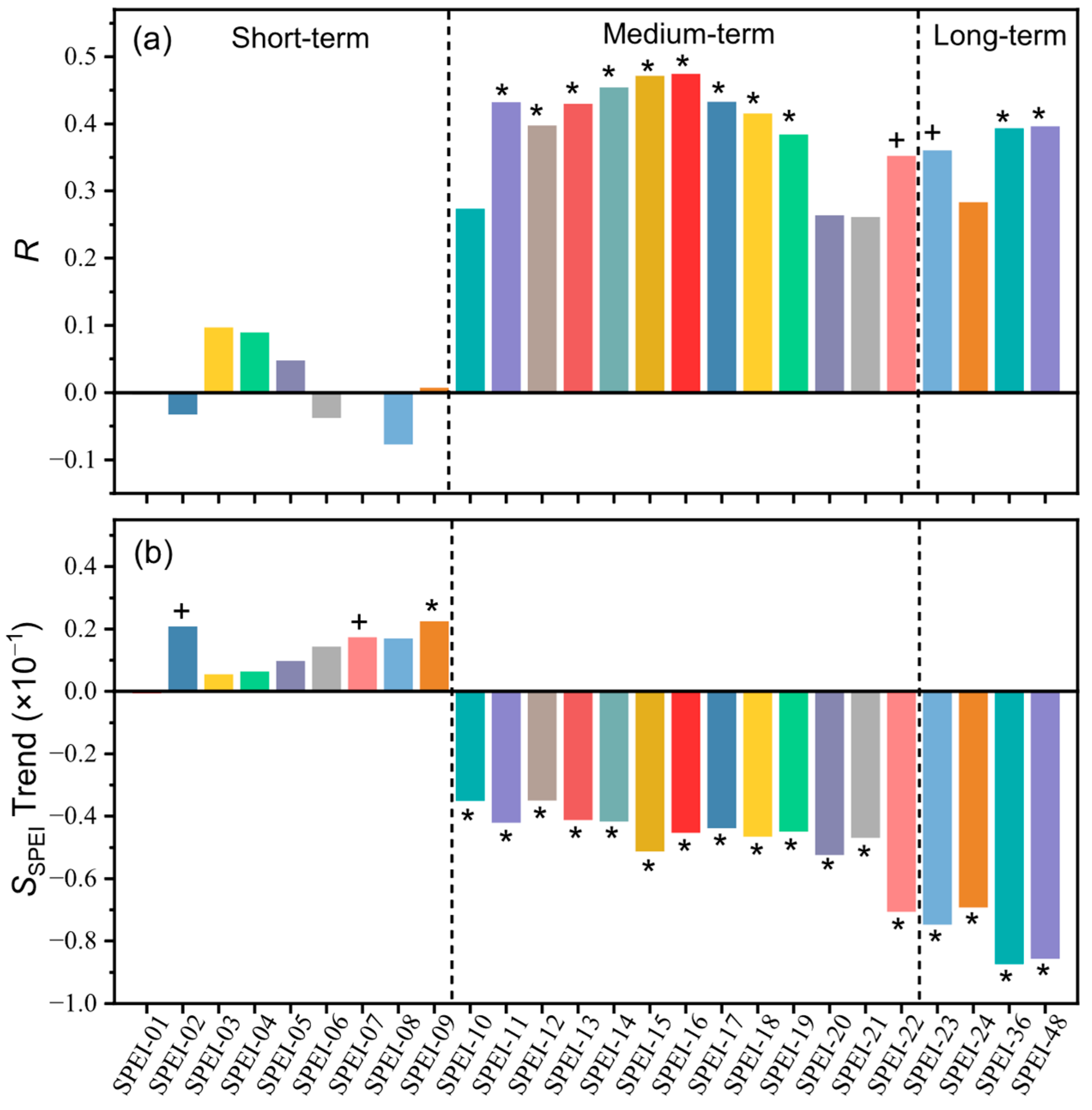

3.3. Sensitivity of Wheat Yield to Drought and Its Changes

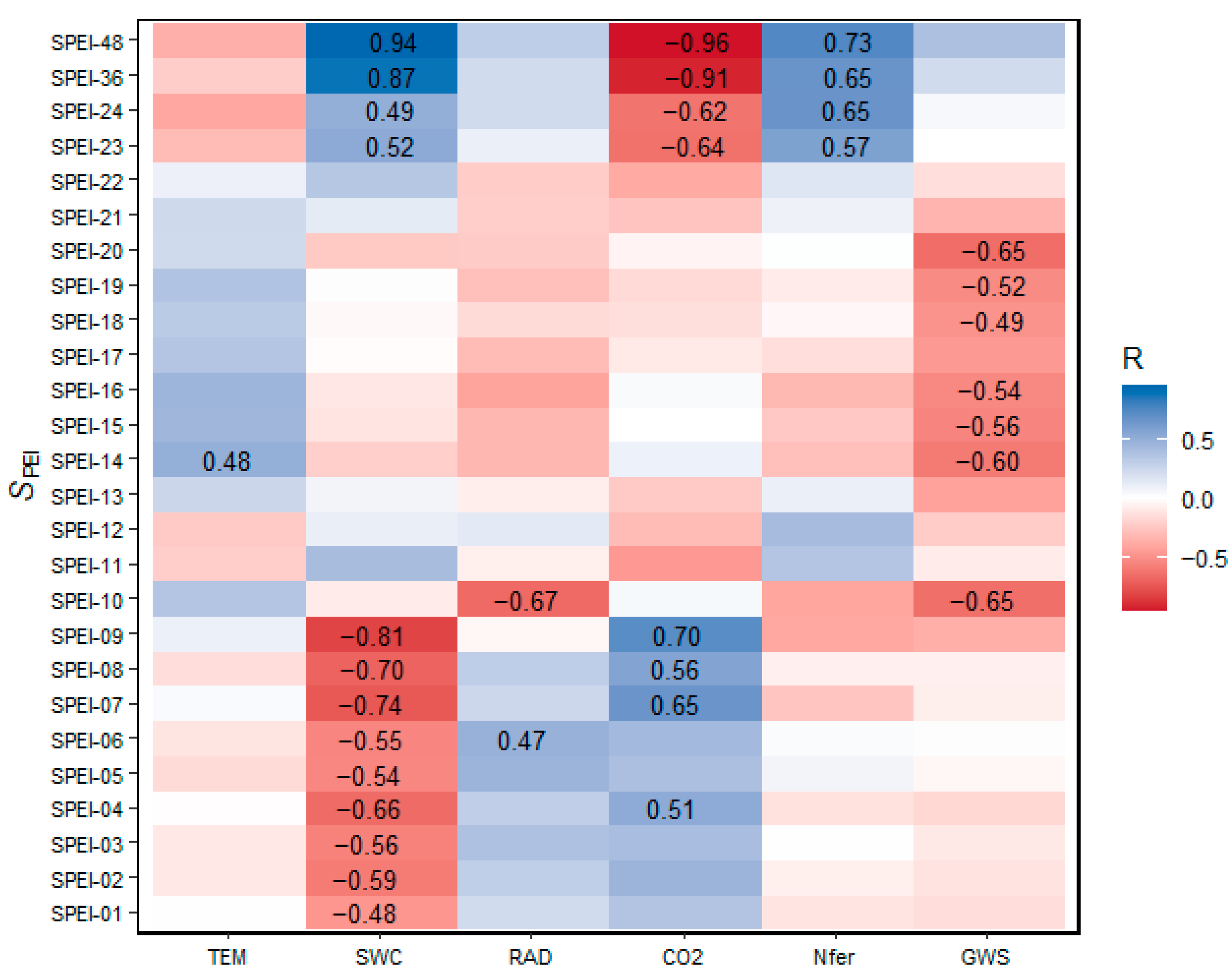

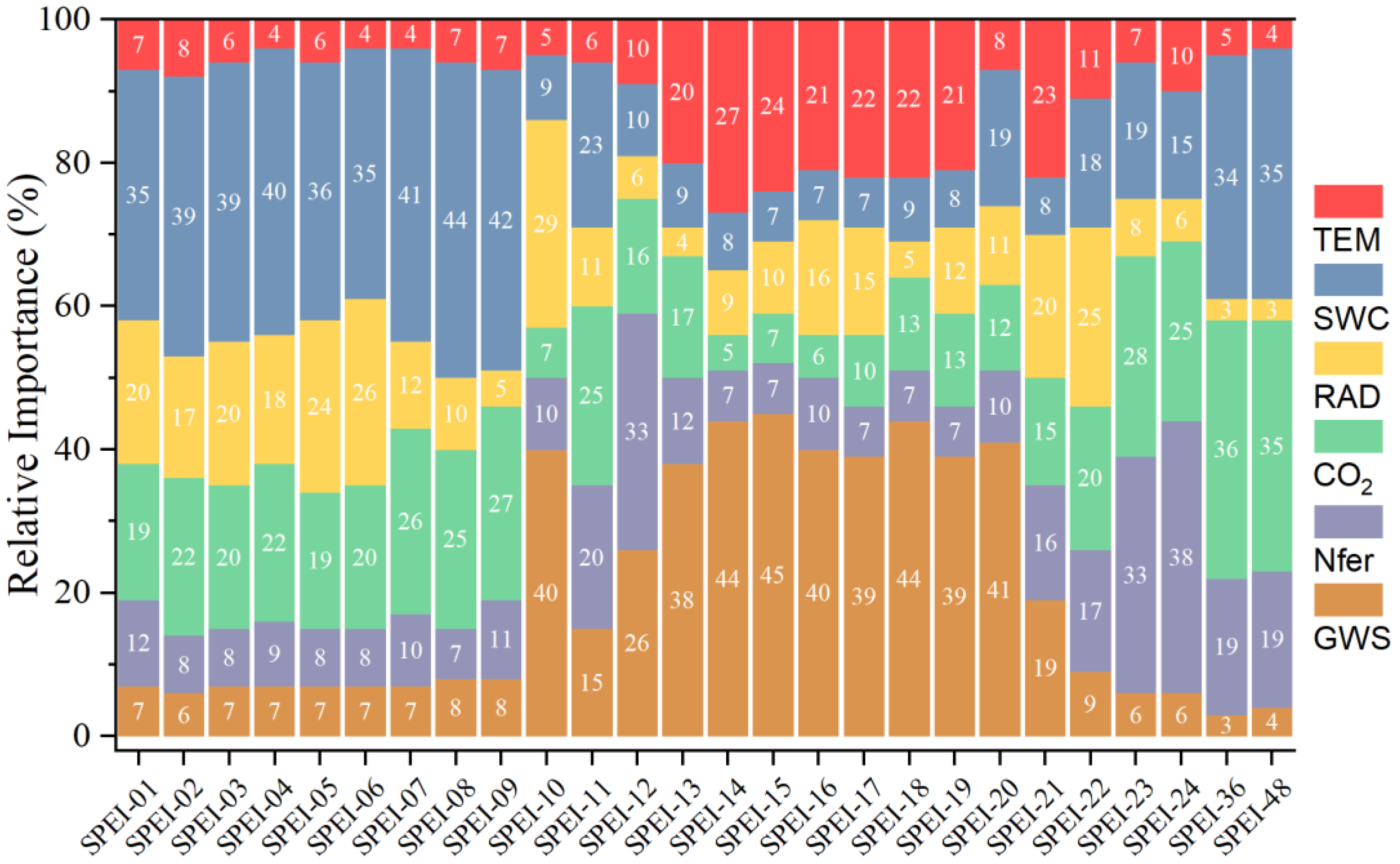

3.4. Environmental Drivers Regulating Wheat Yield SSPEI

4. Discussion

4.1. Declining Sensitivity of Wheat Yield Variations to Drought Overall the NCP

4.2. Environmental Drivers and Mechanisms Underlying the Changes in SSPEI

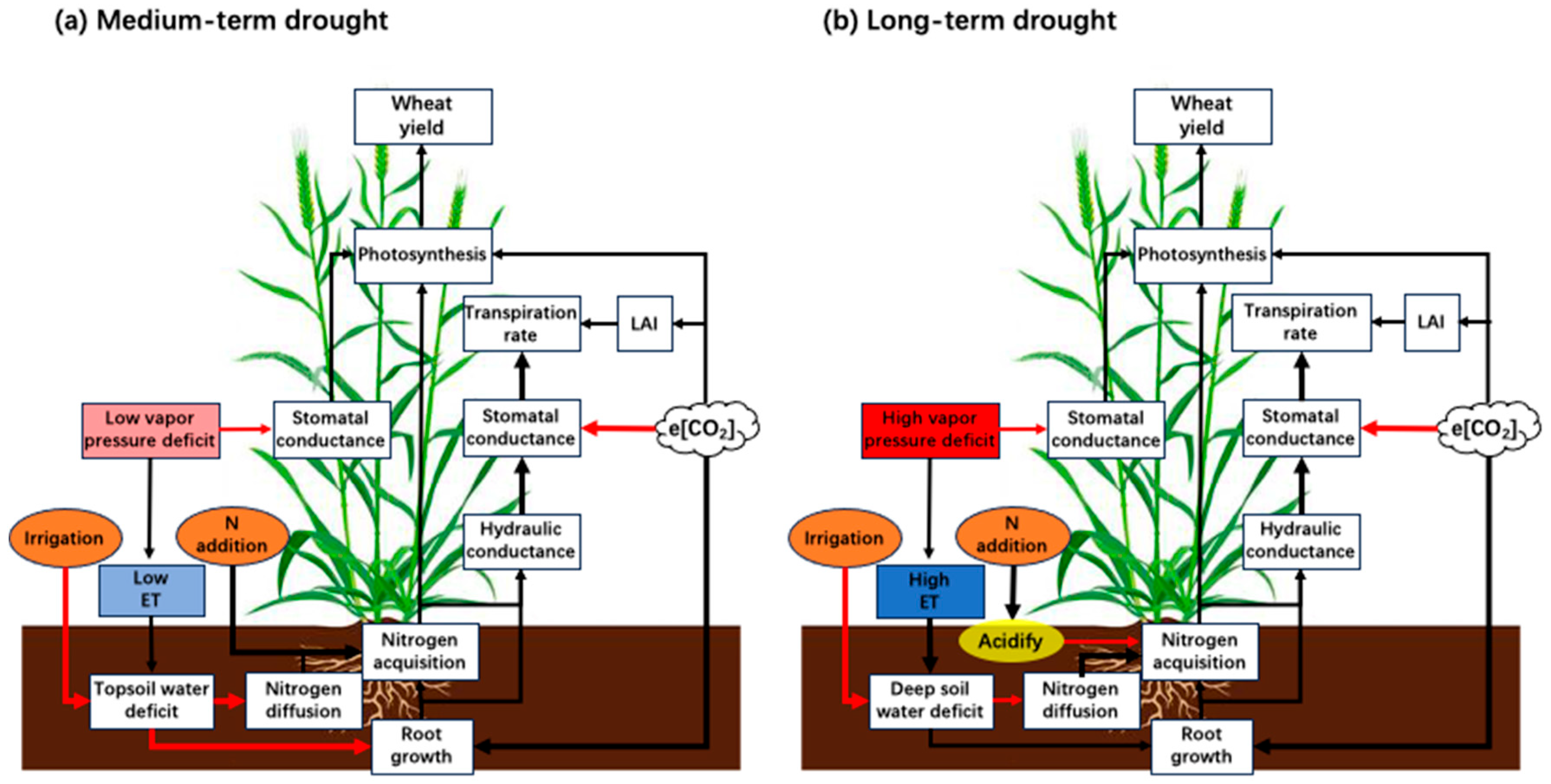

4.2.1. Effects of Soil Moisture and Groundwater on SSPEI

4.2.2. Effects of Atmospheric CO2 on SSPEI

4.2.3. Effects of Nitrogen Addition on SSPEI

4.2.4. Effects of Climate Regimes on SSPEI

4.3. Limitations and Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Samset, B.H.; Zhou, C.; Fuglestvedt, J.S.; Lund, M.T.; Marotzke, J.; Zelinka, M.D. Steady global surface warming from 1973 to 2022 but increased warming rate after 1990. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donat, M.G.; Lowry, A.L.; Alexander, L.V.; O’Gorman, P.A.; Maher, N. More extreme precipitation in the world’s dry and wet regions. Nat. Clim. Change 2016, 6, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalexiou, S.M.; Montanari, A. Global and Regional Increase of Precipitation Extremes Under Global Warming. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 4901–4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.K.; Zhang, X.; Zwiers, F.W.; Hegerl, G.C. Human contribution to more-intense precipitation extremes. Nature 2011, 470, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Quiring, S.M.; Pena-Gallardo, M.; Yuan, S.; Dominguez-Castro, F. A review of environmental droughts: Increased risk under global warming? Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 201, 102953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, Y.; Felfelani, F.; Satoh, Y.; Boulange, J.; Burek, P.; Gädeke, A.; Gerten, D.; Gosling, S.N.; Grillakis, M.; Gudmundsson, L.; et al. Global terrestrial water storage and drought severity under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, M.; Noce, S.; Antonelli, M.; Caporaso, L. Complex drought patterns robustly explain global yield loss for major crops. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.; Iizumi, T.; Nishimori, M. Global Patterns of Crop Production Losses Associated with Droughts from 1983 to 2009. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2019, 58, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.; Wang, L.; Smith, W.K.; Chang, Q.; Wang, H.; D’Odorico, P. Observed increasing water constraint on vegetation growth over the last three decades. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; He, W.; Zhou, Y.; Cheng, N.; Xiao, J.; Bi, W.; Liu, Y.; Sun, S.; Ju, W. Increased Sensitivity of Global Vegetation Productivity to Drought over the Recent Three Decades. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2023, 128, e2022JD037504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadez, V.; Grondin, A.; Chenu, K.; Henry, A.; Laplaze, L.; Millet, E.J.; Carminati, A. Crop traits and production under drought. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lesk, C.; Rowhani, P.; Ramankutty, N. Influence of extreme weather disasters on global crop production. Nature 2016, 529, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.L.; Terrer, C.; Berdugo, M.; Maestre, F.T.; Zhu, Z.C.; Peñuelas, J.; Yu, K.L.; Luo, L.; Gong, J.Y.; Ye, J.S. Nitrogen addition delays the emergence of an aridity-induced threshold for plant biomass. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2023, 10, nwad242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.P.; Lin, Z.H.; Mo, X.G.; Yang, C.L. Responses of crop yield and water use efficiency to climate change in the North China Plain. Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 97, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ma, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, H.; Hu, Y.; Ma, H. China’s strictest water policy: Reversing water use trends and alleviating water stress. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimel, D.; Stephens, B.B.; Fisher, J.B. Effect of increasing CO2 on the terrestrial carbon cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ju, W.; Chen, J.M.; Ciais, P.; Cescatti, A.; Sardans, J.; Janssens, I.A.; Wu, M.; Berry, J.A.; et al. Recent global decline of CO2 fertilization effects on vegetation photosynthesis. Science 2020, 370, 1295–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, T.F.; Hollinger, D.Y.; Bohrer, G.; Dragoni, D.; Munger, J.W.; Schmid, H.P.; Richardson, A.D. Increase in forest water-use efficiency as atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations rise. Nature 2013, 499, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, X.; Piao, S.; Chen, A.; Huntingford, C.; Fu, B.; Li, L.Z.X.; Huang, J.; Sheffield, J.; Berg, A.M.; Keenan, T.F.; et al. Multifaceted characteristics of dryland aridity changes in a warming world. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, T.R.; Rufty, T.W. Nitrogen and water resources commonly limit crop yield increases, not necessarily plant genetics. Glob. Food Secur. 2012, 1, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Chen, Q.M.; Tan, Q.H. Responses of wheat yields and water use efficiency to climate change and nitrogen fertilization in the North China plain. Food Secur. 2019, 11, 1231–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, G.; Chen, Y.; Sui, P.; Pacenka, S.; Steenhuis, T.S.; Siddique, K.H.M. Reduced groundwater use and increased grain production by optimized irrigation scheduling in winter wheat-summer maize double cropping system-A 16-year field study in North China Plain. Field Crops Res. 2022, 275, 108364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, P.; Song, C. Impact of Droughts on Winter Wheat Yield in Different Growth Stages during 2001–2016 in Eastern China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2018, 9, 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleeson, T.; Wada, Y.; Bierkens, M.F.P.; van Beek, L.P.H. Water balance of global aquifers revealed by groundwater footprint. Nature 2012, 488, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Min, L.; Chang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shen, Y.-J. Identifying hotspots of water table depth change by coupling trend with time stability analysis in the North China Plain. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 167002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Liu, T.; Xu, K.; Chen, C. The impact of high temperature and drought stress on the yield of major staple crops in northern China. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 314, 115092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Cui, L.; Tian, Z. Spatial and temporal distribution and trend in flood and drought disasters in East China. Environ. Res. 2020, 185, 109406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, D.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, G. Characteristics of spring drought in North China over the past 60 years and its relationship with sea surface temperature in the North Atlantic. Trans. Atmos. Sci. 2021, 44, 451–460. [Google Scholar]

- Hamani, A.K.M.; Abubakar, S.A.; Si, Z.; Kama, R.; Gao, Y.; Duan, A. Suitable split nitrogen application increases grain yield and photosynthetic capacity in drip-irrigated winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under different water regimes in the North China Plain. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1105006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ge, Q. The optimization of wheat yield through adaptive crop management in a changing climate: Evidence from China. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 3644–3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Liu, J.; Cao, G.; Kendy, E.; Wang, H.; Jia, Y. Can China Cope with Its Water Crisis?—Perspectives from the North China Plain. Ground Water 2010, 48, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, F.; Wang, J.; Song, Y. Characteristics of Climate Change in the North China Plain for Recent 45 Years. Meteorol. Mon. 2010, 36, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, P.; Song, C. Impacts of drought intensity and drought duration on winter wheat yield in five provinces of North China plain. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2019, 74, 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Beguería, S.; López-Moreno, J.I. A Multiscalar Drought Index Sensitive to Global Warming: The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 1696–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Liu, J.; Kattel, G. Historical nitrogen fertilizer use in China from 1952 to 2018. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 14, 5179–5194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, V.; Zscheischler, J.; Ciais, P.; Gudmundsson, L.; Sitch, S.; Seneviratne, S.I. Sensitivity of atmospheric CO2 growth rate to observed changes in terrestrial water storage. Nature 2018, 560, 628–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rateb, A.; Scanlon, B.R.; Pool, D.R.; Sun, A.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Clark, B.; Faunt, C.C.; Haugh, C.J.; Hill, M.; et al. Comparison of Groundwater Storage Changes from GRACE Satellites with Monitoring and Modeling of Major U.S. Aquifers. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2020WR027556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, V.; Gudmundsson, L. GRACE-REC: A reconstruction of climate-driven water storage changes over the last century. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1153–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Kusche, J.; Chao, N.; Wang, Z.; Loecher, A. Long-Term (1979-Present) Total Water Storage Anomalies over the Global Land Derived by Reconstructing GRACE Data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2021GL093492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, R. Asian meteorological droughts on three time scales and different roles of sea surface temperature and soil moisture. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 41, 6047–6064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhang, L.; Tang, Z.; Wu, S.; Battipaglia, G. A synthesis of ecosystem aboveground productivity and its process variables under simulated drought stress. J. Ecol. 2019, 107, 2519–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groemping, U. Relative importance for linear regression in R: The package relaimpo. J. Stat. Softw. 2006, 17, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, D.K.; West, P.C.; Clark, M.; Gerber, J.S.; Prishchepov, A.V.; Chatterjee, S. Climate change has likely already affected global food production. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, D.K.; Gerber, J.S.; MacDonald, G.K.; West, P.C. Climate variation explains a third of global crop yield variability. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesk, C.; Coffel, E.; Winter, J.; Ray, D.; Zscheischler, J.; Seneviratne, S.I.; Horton, R. Stronger temperature–moisture couplings exacerbate the impact of climate warming on global crop yields. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Yu, H.; Guan, X.; Wang, G.; Guo, R. Accelerated dryland expansion under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2016, 6, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutroulis, A.G. Dryland changes under different levels of global warming. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 655, 482–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.F.; Pan, Y.Z.; Zhu, X.F.; Yang, T.T.; Bai, J.J.; Sun, Z.L. Drought evolution and its impact on the crop yield in the North China Plain. J. Hydrol. 2018, 564, 984–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Huang, L.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H. Weakening sensitivity of global vegetation to long-term droughts. Sci. China-Earth Sci. 2018, 61, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denissen, J.M.C.; Teuling, A.J.; Pitman, A.J.; Koirala, S.; Migliavacca, M.; Li, W.; Reichstein, M.; Winkler, A.J.; Zhan, C.; Orth, R. Widespread shift from ecosystem energy to water limitation with climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, L.; Ding, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, X.; Cai, H. Adaptation of winter wheat varieties and irrigation patterns under future climate change conditions in Northern China. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 243, 106409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Singh, V.P. A review of drought concepts. J. Hydrol. 2010, 391, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, F. Chapter 2—Crop exposure to drought stress under elevated CO2: Responses in physiological, biochemical, and molecular levels. In Sustainable Crop Productivity and Quality Under Climate Change; Liu, F., Li, X., Hogy, P., Jiang, D., Brestic, M., Liu, B., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Riley, W.J.; Prentice, I.C.; Keenan, T.F. CO2 fertilization of terrestrial photosynthesis inferred from site to global scales. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2115627119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Jiao, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, L. Increased Global Vegetation Productivity Despite Rising Atmospheric Dryness over the Last Two Decades. Earths Future 2022, 10, e2021EF002634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eziz, A.; Yan, Z.; Tian, D.; Han, W.; Tang, Z.; Fang, J. Drought effect on plant biomass allocation: A meta-analysis. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 11002–11010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, A.; Wang, L.; Guo, X.; Niu, Y.; Liu, S.; Mi, G.; Gao, Q. Reducing basal nitrogen rate to improve maize seedling growth, water and nitrogen use efficiencies under drought stress by optimizing root morphology and distribution. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 212, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domec, J.C.; Smith, D.D.; McCulloh, K.A. A synthesis of the effects of atmospheric carbon dioxide enrichment on plant hydraulics: Implications for whole-plant water use efficiency and resistance to drought. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 40, 921–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.C.; Schmidhalter, U. Drought and salinity: A comparison of their effects on mineral nutrition of plants. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2005, 168, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korres, N.E.; Norsworthy, J.K.; Tehranchian, P.; Gitsopoulos, T.K.; Loka, D.A.; Oosterhuis, D.M.; Gealy, D.R.; Moss, S.R.; Burgos, N.R.; Miller, M.R.; et al. Cultivars to face climate change effects on crops and weeds: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 36, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Mi, Z.; Lin, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Wang, H.; Liu, L.; Zhu, B.; Cao, G.; et al. Shifting plant species composition in response to climate change stabilizes grassland primary production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 4051–4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Sack, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, K.; Zhang, Q.; He, N.; Yu, G. Relationships of stomatal morphology to the environment across plant communities. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Long, D.; Scanlon, B.R.; Burek, P.; Zhang, C.; Han, Z.; Butler, J.J.; Pan, Y.; Lei, X.; Wada, Y. Human Intervention Will Stabilize Groundwater Storage Across the North China Plain. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58, e2021WR030884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Piao, S.; Jeong, S.J.; Zhou, L.; Zeng, Z.; Ciais, P.; Chen, D.; Huang, M.; Jin, C.S.; Li, L.Z.; et al. Evaporative cooling over the Tibetan Plateau induced by vegetation growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 9299–9304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainsworth, E.A.; Rogers, A. The response of photosynthesis and stomatal conductance to rising [CO2]: Mechanisms and environmental interactions. Plant Cell Environ. 2007, 30, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tor-ngern, P.; Oren, R.; Ward, E.J.; Palmroth, S.; McCarthy, H.R.; Domec, J.-C. Increases in atmospheric CO2 have little influence on transpiration of a temperate forest canopy. New Phytol. 2015, 205, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manea, A.; Leishman, M.R. Leaf Area Index Drives Soil Water Availability and Extreme Drought-Related Mortality under Elevated CO2 in a Temperate Grassland Model System. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.Z.; Liang, C.; Cui, N.B.; Zhao, L.; Liu, C.W.; Feng, Y.; Hu, X.T.; Gong, D.Z.; Zou, Q.Y. Water use efficiency and its drivers in four typical agroecosystems based on flux tower measurements. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 295, 108200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gentine, P.; Luo, X.; Lian, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Michalak, A.M.; Sun, W.; Fisher, J.B.; Piao, S.; et al. Increasing sensitivity of dryland vegetation greenness to precipitation due to rising atmospheric CO2. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.X.; Mo, X.G.; Lin, Z.H.; Xu, Y.Q.; Ji, J.J.; Wen, G.; Richey, J. Crop yield responses to climate change in the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 97, 1195–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, G.; Fu, Z.; Ciais, P.; Feng, X.; Li, J.; Fu, B. Compound droughts slow down the greening of the Earth. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 3072–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; An, L.; Zhong, S.; Shen, L.; Wu, S. Declining coupling between vegetation and drought over the past three decades. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benlloch-Gonzalez, M.; Bochicchio, R.; Berger, J.; Bramley, H.; Palta, J.A. High temperature reduces the positive effect of elevated CO2 on wheat root system growth. Field Crops Res. 2014, 165, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yin, W.; Chai, Q.; Fan, Z.; Hu, F.; Zhao, L.; Fan, H.; He, W.; Cao, W. Enhancing crop production and carbon sequestration of wheat in arid areas by green manure with reduced nitrogen fertilizer. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manderscheid, R.; Dier, M.; Erbs, M.; Sickora, J.; Weigel, H.-J. Nitrogen supply—A determinant in water use efficiency of winter wheat grown under free air CO2 enrichment. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 210, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Chai, Q.; Li, G.; Zhao, C.; Yu, A.; Fan, Z.; Yin, W.; Hu, F.; Fan, H.; Wang, Q.; et al. Improving wheat grain yield via promotion of water and nitrogen utilization in arid areas. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sha, Z.; Zhang, J.; Kang, J.; Xu, W.; Goulding, K.; Liu, X. Reactive N emissions from cropland and their mitigation in the North China Plain. Environ. Res. 2022, 214, 114015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenka, S.; Singh, A.K.; Lenka, N.K. Water and nitrogen interaction on soil profile water extraction and ET in maize–wheat cropping system. Agric. Water Manag. 2009, 96, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Hu, C.; Olesen, J.E.; Ju, Z.; Zhang, X. Effect of warming and nitrogen addition on evapotranspiration and water use efficiency in a wheat-soybean/fallow rotation from 2010 to 2014. Clim. Change 2016, 139, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AghaKouchak, A.; Chiang, F.; Huning, L.S.; Love, C.A.; Mallakpour, I.; Mazdiyasni, O.; Moftakhari, H.; Papalexiou, S.M.; Ragno, E.; Sadegh, M. Climate Extremes and Compound Hazards in a Warming World. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2020, 48, 519–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevacqua, E.; Zappa, G.; Lehner, F.; Zscheischler, J. Precipitation trends determine future occurrences of compound hot–dry events. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zscheischler, J.; Mahecha, M.D.; von Buttlar, J.; Harmeling, S.; Jung, M.; Rammig, A.; Randerson, J.T.; Schoelkopf, B.; Seneviratne, S.I.; Tomelleri, E.; et al. A few extreme events dominate global interannual variability in gross primary production. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 035001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Liu, F.; Niu, B.; Xi, Z.; Zheng, Y. Declining Crop Yield Sensitivity to Drought and Its Environmental Drivers in the North China Plain. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10798. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310798

Wang Z, Cao Y, Liu F, Niu B, Xi Z, Zheng Y. Declining Crop Yield Sensitivity to Drought and Its Environmental Drivers in the North China Plain. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10798. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310798

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhipeng, Yanan Cao, Fei Liu, Ben Niu, Zengfu Xi, and Yunpu Zheng. 2025. "Declining Crop Yield Sensitivity to Drought and Its Environmental Drivers in the North China Plain" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10798. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310798

APA StyleWang, Z., Cao, Y., Liu, F., Niu, B., Xi, Z., & Zheng, Y. (2025). Declining Crop Yield Sensitivity to Drought and Its Environmental Drivers in the North China Plain. Sustainability, 17(23), 10798. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310798