Life Cycle Assessment of Small Passenger Cars in the Context of Smart Grid Integration and Sustainable Power System Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Plan, Program and Object of Research

2.2. LCA Method

2.3. ReCiPe 2016

2.4. IPCC 2021

2.5. Model CED

2.6. Model CML-IA Baseline

2.7. Ecological Scarcity 2021

3. Results and Their Analysis

3.1. Model ReCiPe 2016

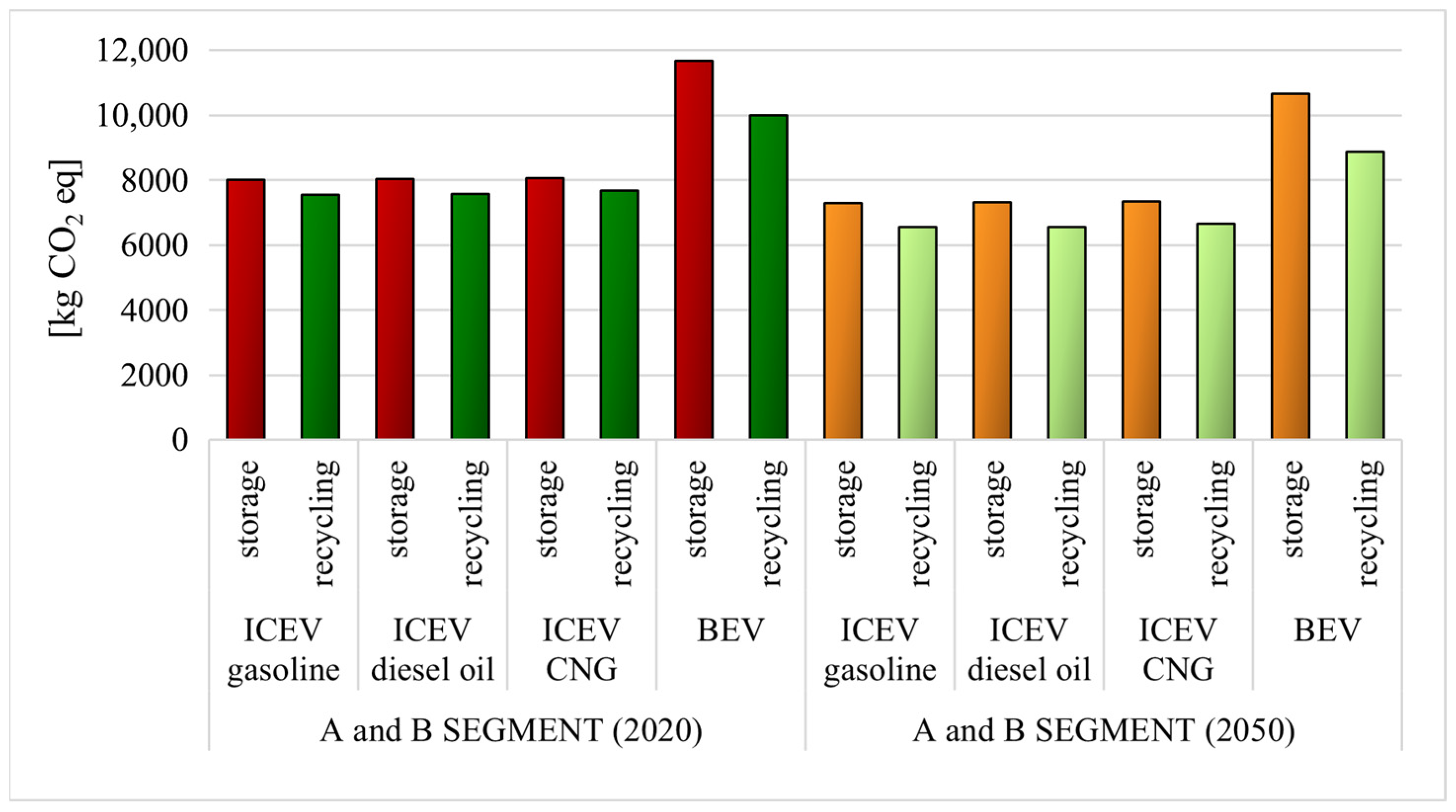

3.2. Model IPCC 2021

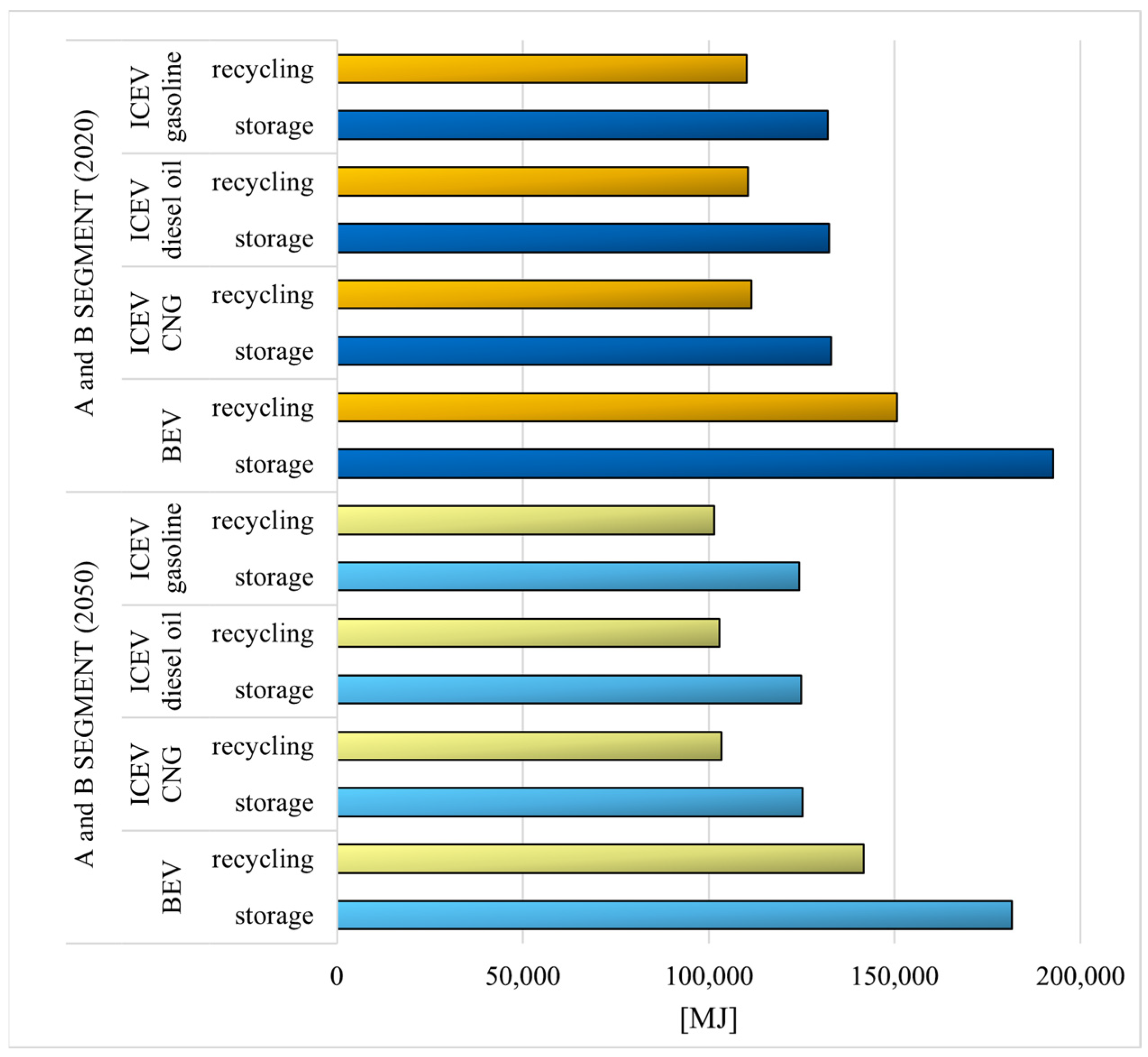

3.3. Model CED

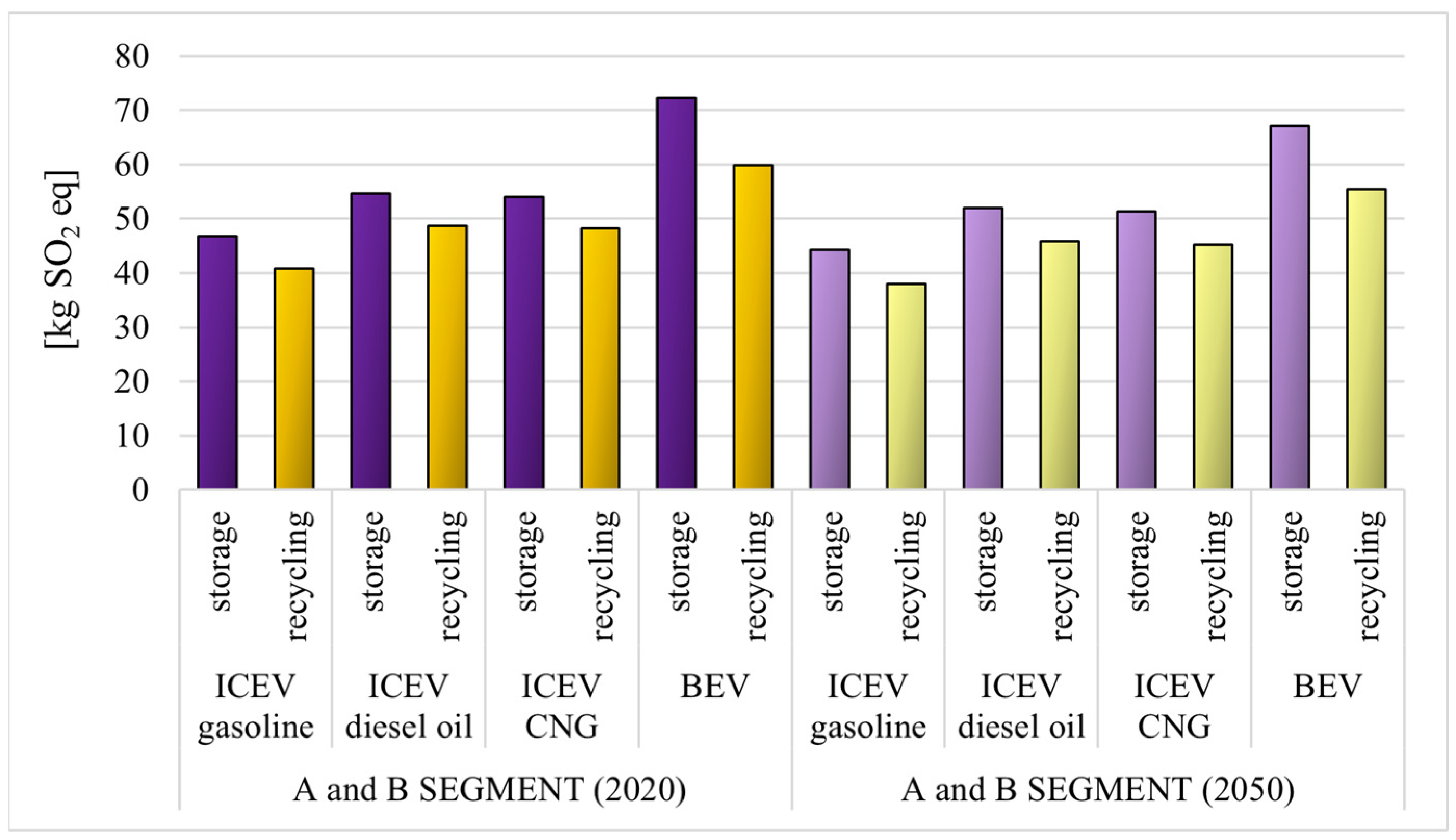

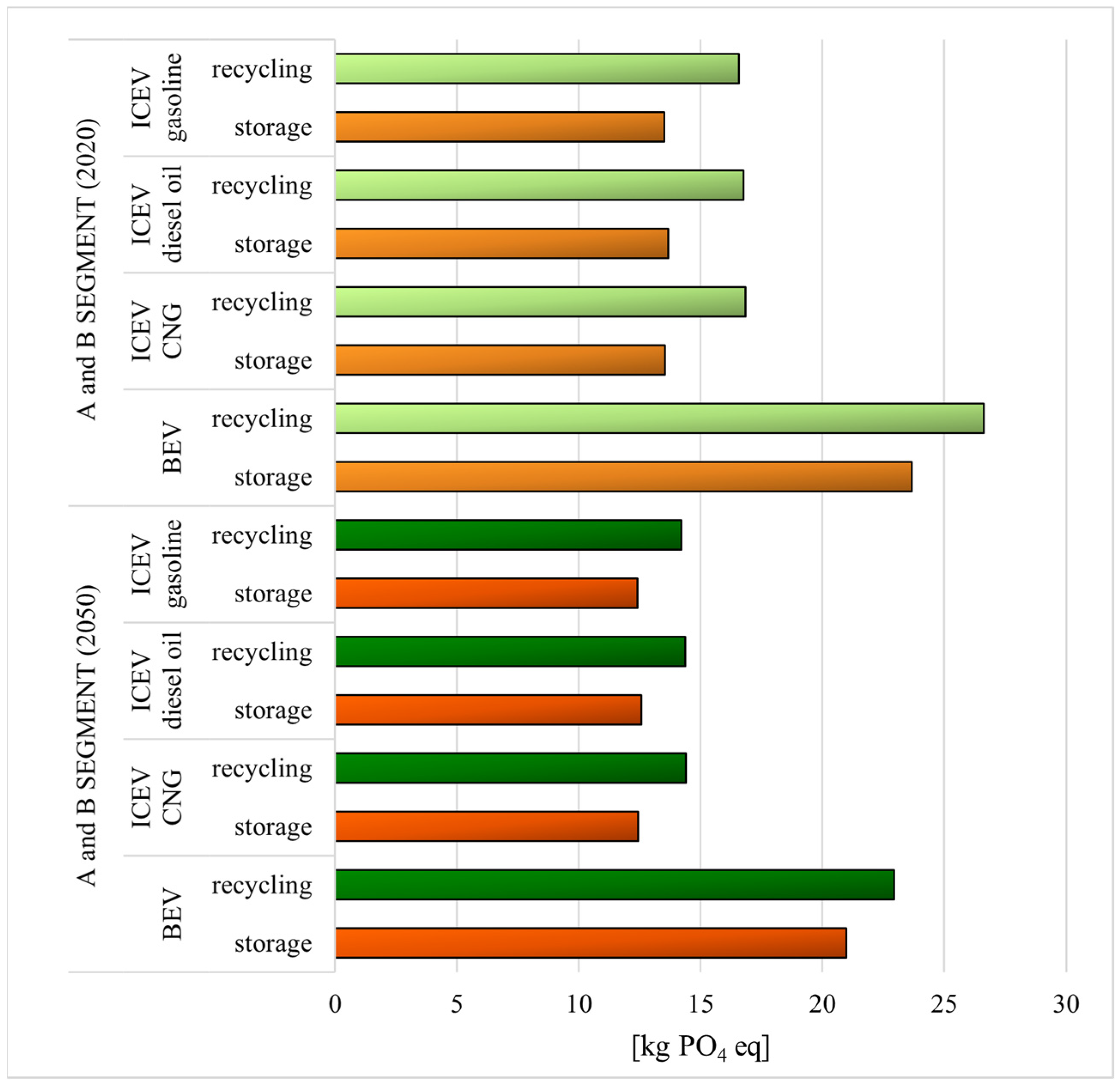

3.4. Model CML-IA Baseline

3.5. Model Ecological Scarcity 2021

4. Summary and Conclusions

- (1)

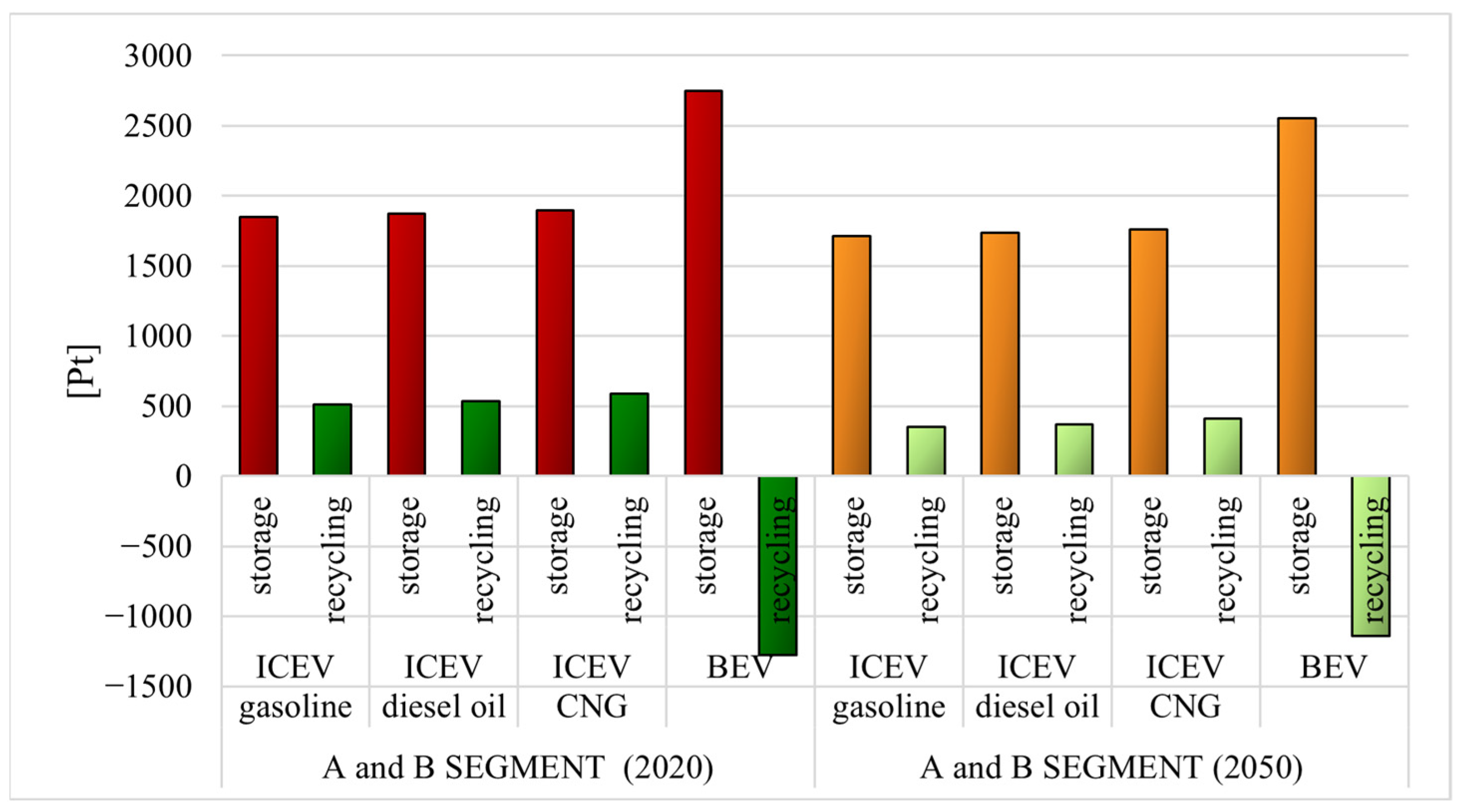

- All vehicles registered in 2020 have a significantly higher harmful impact on the environment compared to those expected to be registered in 2050 (analyses using the ReCiPe 2016 model, excluding fuel and energy cycles). This is visible, among others in the area of greenhouse gas emissions (IPCC 2021 model), energy intensity (CED V1.11 model), acidification and eutrophication of the environment (CML-IA baseline model), emissions of carcinogenic substances into the atmosphere, emissions of heavy metals into the soil, and land use change (Ecological Scarcity 2021 model).

- (2)

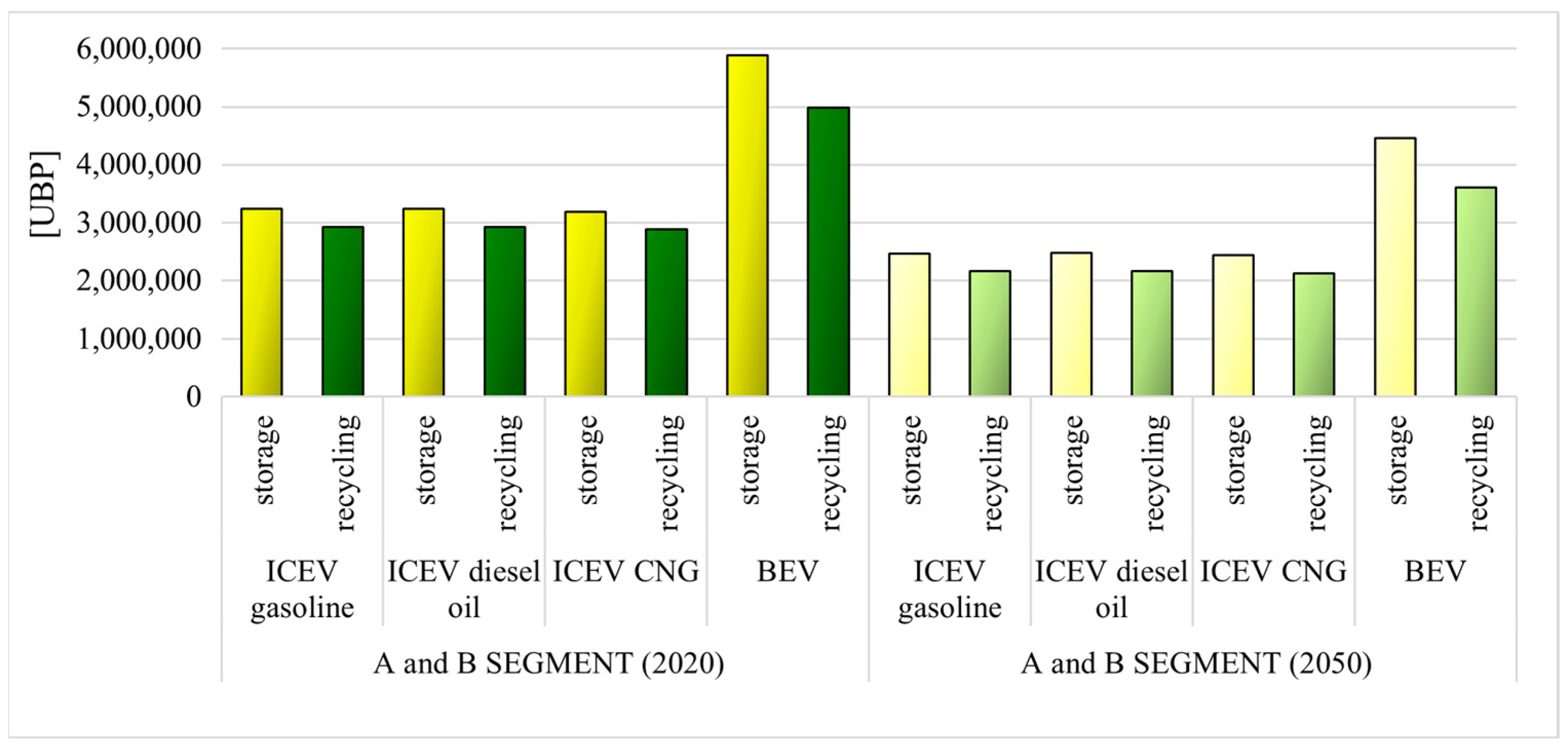

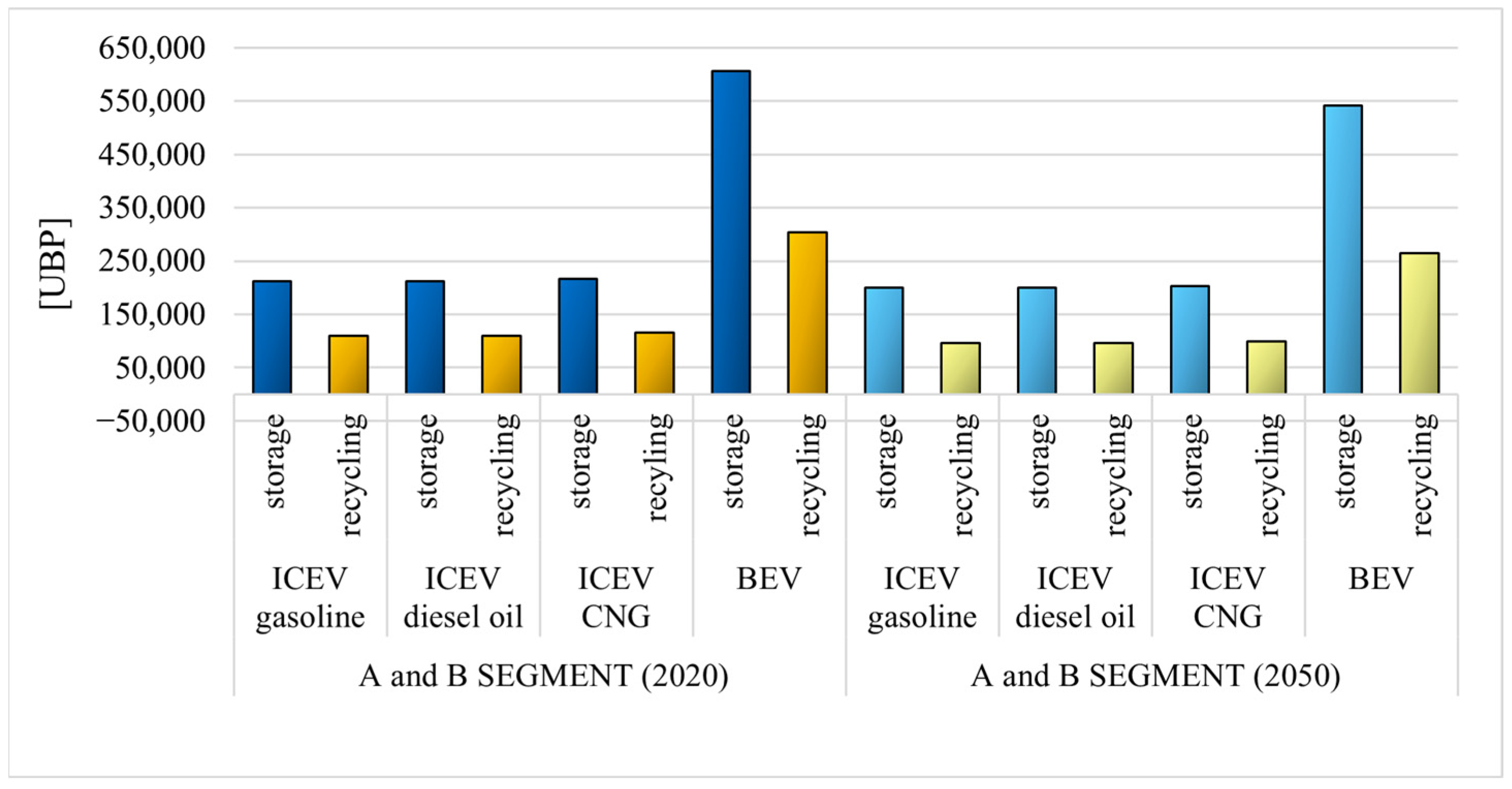

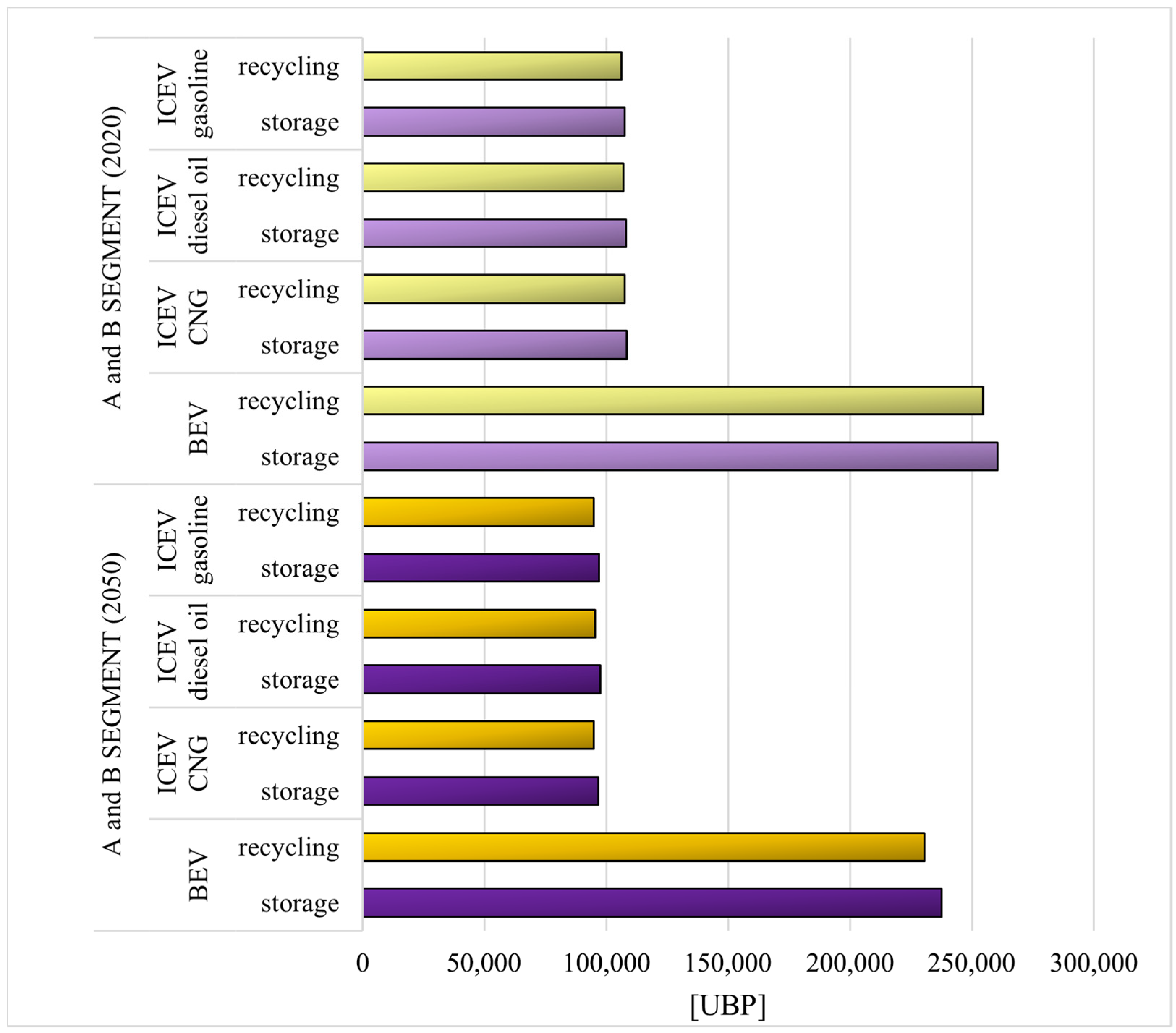

- The largest number of negative impacts was recorded in the context of the impact of the cars in question on human health, while the least—in relation to the problem of depletion of raw material resources (excluding fuel and energy cycles). The maximum level of total disruptive impacts was recorded for the lifetime of battery electric vehicles (BEVs), assuming their end-of-life storage. Recycling would make it possible to significantly reduce hazardous impacts over the entire life cycle of these vehicles (ReCiPe 2016 analyses).

- (3)

- Among the substances characterized by harmful effects on human health in the life cycles of all the evaluated cars, the maximum level of emissions was distinguished by chromium (VI), carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, zinc, fine particulate matter (PM), nitrogen oxide, arsenic, and methane (tests using the ReCiPe 2016 model).

- (4)

- The categories of impacts with the highest level of negative environmental consequences for the environment, identified in the life cycles of all the analyzed vehicles, including processes causing the depletion of water resources affecting human health and terrestrial ecosystems, emissions of substances causing the formation of fine particulate matter (PM), toxic substances with carcinogenic effects on humans and substances causing global warming (assessment using the use of ReCiPe 2016 model, which does not take into account fuel and energy cycles).

- (5)

- The life cycles of the tested cars (excluding fuel and energy cycles), assuming their form of post-consumer management in the form of landfilling instead of recycling, cause more destructive environmental consequences, including higher greenhouse gas emissions, higher energy intensity, higher degree of acidification of the environment, higher emissions of carcinogenic substances, heavy metals into the soil and wider changes in the way of land use (analyses using ReCiPe 2016, IPCC 2021, CED V1.11, CML-IA baseline and Ecological Scarcity 2021 models).

- (6)

- The maximum level of negative environmental impacts for each of the areas under consideration is distinguished by BEVs, whose plastics, materials and components would be landfilled. However, the use of recycling would result in a significant reduction in the level of destructive impacts over their entire life cycle (assessment using ReCiPe 2016, IPCC 2021, CED V1.11, and CML-IA baseline and Ecological Scarcity 2021 models, excluding fuel and energy cycles).

- (7)

- The life cycles of ICEVs were characterized by a similar level of hazardous environmental impact, both in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, energy intensity, eutrophication of the environment, emissions of carcinogenic substances into the atmosphere, emissions of heavy metals to the soil and land use change (analyses using the ReCiPe 2016, IPCC 2021, CED V1.11, and CML-IA baseline and Ecological Scarcity 2021 models, not taking into account fuel and energy cycles).

- (8)

- Among the processes related to energy generation, identified in the life cycles of the analyzed cars, characterized by the highest level of harmful environmental consequences for the environment, processes related to the use of non-renewable fossil fuels can be distinguished, in particular the processes of using natural gas, crude oil and hard coal (tests using the CED V1.11 model).

- (9)

- The maximum level of emissions among acidifying substances, in the life cycles of all the vehicles considered, was characterized by sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxide, ammonia and sulfur trioxide. On the other hand, among the compounds causing the deepening eutrophication of the environment, the highest level of emissions was characterized by phosphates, nitrates, and phosphorus (assessment using the CML-IA baseline model).

- (10)

- In the case of chemical compounds with a carcinogenic effect on humans, the highest level of emissions to the atmosphere in the life cycles of the analyzed cars were distinguished by benzo(α)pyrene, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzodioxin (TCDD), benzene, chloroethene, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). On the other hand, the maximum level of emissions among heavy metals was recorded for: chromium (VI), zinc, copper, nickel, cadmium, and lead (analyses using the Ecological Scarcity 2021 model).

- (11)

- Among the processes related to the change in land use, with the highest level of negative impacts in the life cycles of all the vehicles considered, the following processes can be distinguished: land occupation by landfills, occupation by the area of mineral resources extraction, occupation by an industrial area, occupation by construction sites, and consequently—built-up area, and occupation of agricultural land and its use for purposes other than plant cultivation (research on Ecological Scarcity 2021).

- (12)

- For all the cars analyzed, vehicles registered in 2020 have higher greenhouse gas emissions compared to those expected to be registered in 2050. Achieving the key targets of the Paris Agreement would result in a significant reduction in the considered emissions to the environment (assessment using the IPCC 2021 model).

- (13)

- Among the chemical compounds causing the deepening of the greenhouse effect, the highest level of emissions in the life cycles of all the cars assessed stood out: carbon dioxide, methane, tetrafluoromethane (CFC-14), nitrous oxide, sulfur hexafluoride, trifluoromethane (HFC-23) and hexafluoroethane (HFC-116) (assessment using the IPCC 2021 model).

- -

- promote the integration of vehicle charging infrastructure with smart grids, enabling bidirectional energy flows, demand-side management, and increased utilization of renewable electricity;

- -

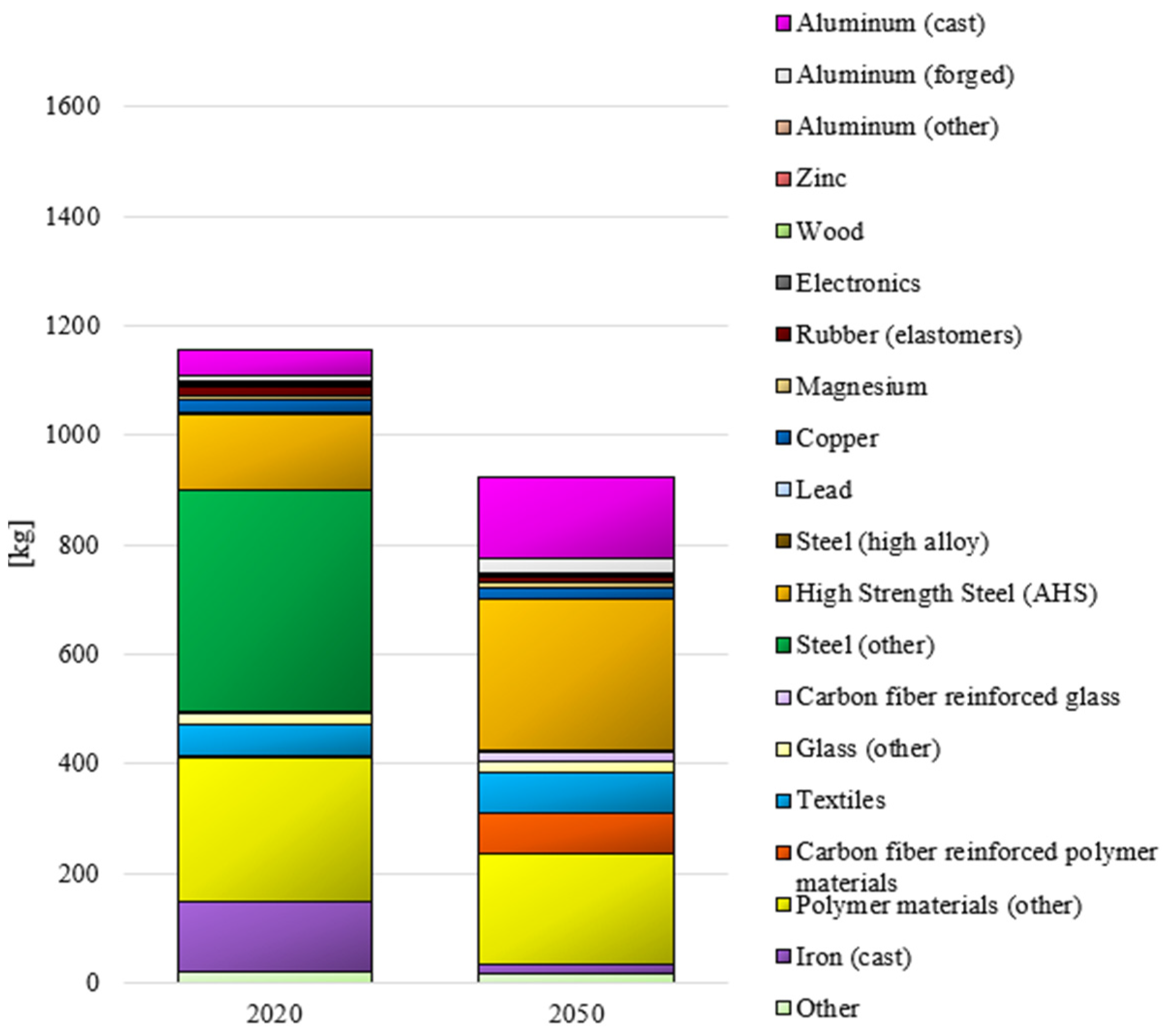

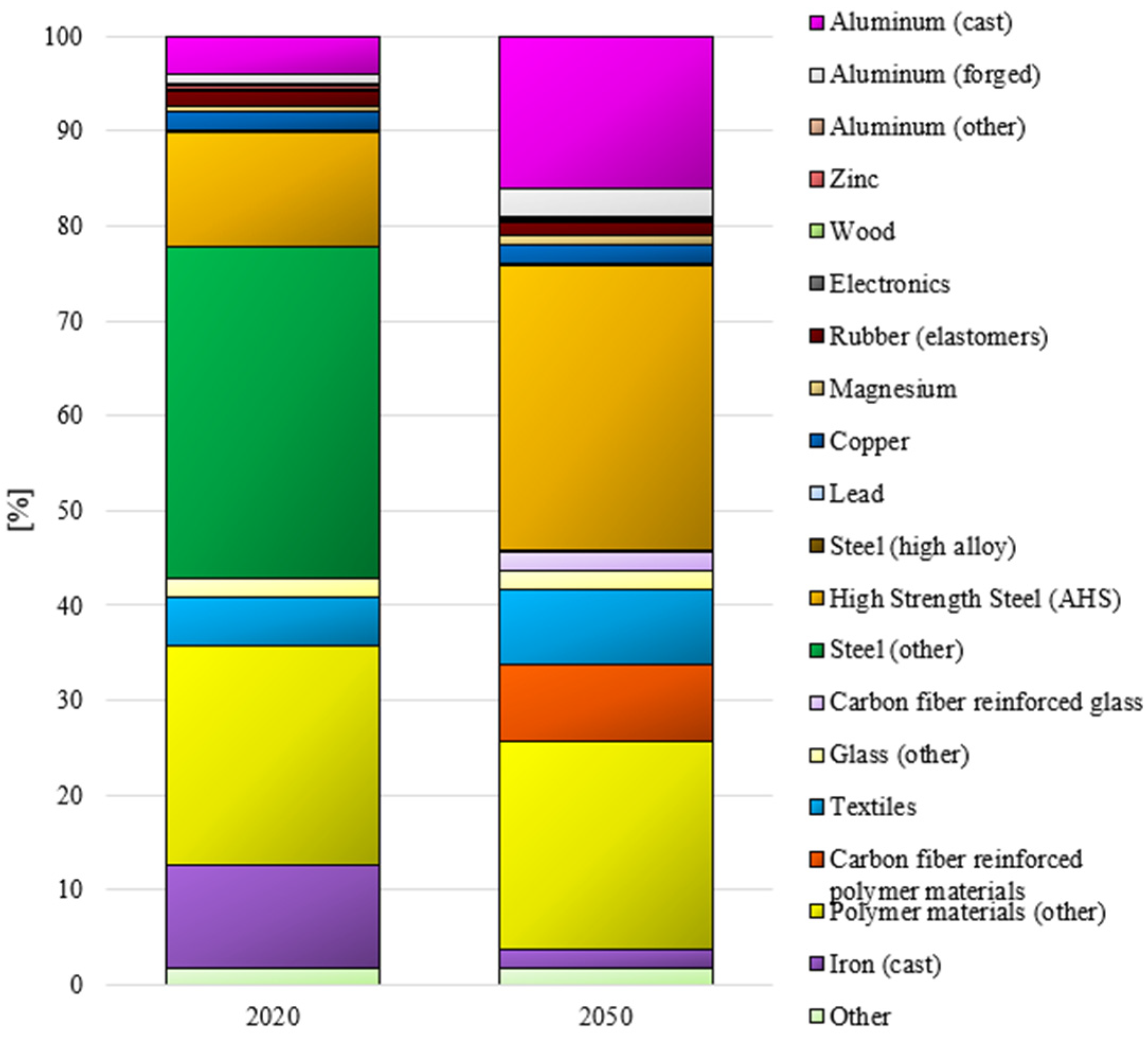

- encourage lightweight design and the use of advanced, recyclable materials such as high-strength steels, aluminum, and composite structures to improve vehicle energy efficiency and reduce life-cycle emissions;

- -

- expand recycling and circular material flows, particularly for traction batteries and critical metals, to minimize resource depletion and dependence on virgin raw materials;

- -

- support the harmonization and standardization of LCA methodologies across the European automotive industry, ensuring consistency, transparency, and comparability of environmental assessments;

- -

- promote R&D in next-generation battery technologies, focusing on improved durability, recyclability, and lower reliance on critical or hazardous elements such as cobalt and nickel;

- -

- strengthen policy incentives for manufacturers implementing closed-loop supply chains, eco-design principles, and modular architectures facilitating easier disassembly and material recovery;

- -

- integrate LCA-based decision tools into transport policy planning to evaluate environmental trade-offs and prioritize investments aligned with EU climate neutrality targets.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Council on Clean Transportation, Vision 2050. A Strategy to Decarbonize the Global Transport Sector by Mid-century. Available online: https://theicct.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/ICCT_Vision2050_sept2020.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Adoption of the Paris Agreement. 12 December 2015. Available online: http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/l09r01.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Tolley, R. Sustainable Transport; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, S.; Dwivedi, G.; Verma, P. Life cycle assessment of electric vehicles in comparison to combustion engine vehicles: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 49, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkisz-Guranowska, A.; Pielecha, J. Emisja Zanieczyszczeń z Pojazdów Samochodowych a Parametry Ruchu Drogowego; Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Warszawskiej: Warszawa, Poland; Poznań, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, T.; Gorham, R. Sustainable urban transport: Four innovative directions. Technol. Soc. 2006, 28, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, K.J.; Árnadóttir, Á.; Heinonen, J.; Czepkiewicz, M.; Davíðsdóttir, B. Review and meta-analysis of EVs: Embodied emissions and environmental breakeven. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Roadmap Agency, Technology Roadmap—Electric and Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles. 2011. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/technology-roadmap-electric-and-plug-in-hybrid-electric-vehicles (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Karaaslan, E.; Zhao, Y.; Tatari, O. Comparative life cycle assessment of sport utility vehicles with different fuel options. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018, 23, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temporelli, A.; Carvalho, M.L.; Girardi, P. Life Cycle Assessment of Electric Vehicle Batteries: An Overview of Recent Literature. Energies 2020, 13, 2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messagie, M. Life Cycle Analysis of the Climate Impact of Electric Vehicles Transport & Environment. Available online: https://www.transportenvironment.org/uploads/files/TE20-20draft20report20v04.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Bouter, A.; Hache, E.; Ternel, C.; Beauchet, S. Comparative environmental life cycle assessment of several powertrain types for cars and buses in France for two driving cycles: “worldwide harmonized light vehicle test procedure” cycle and urban cycle. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 1545–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picatoste, A.; Justel, D.; Mendoza, J.M. Circularity and life cycle environmental impact assessment of batteries for electric vehicles: Industrial challenges, best practices and research guidelines. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 169, 112941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerssen-Gondelach, S.J.; Faaij, A.P. Performance of batteries for electric vehicles on short and longer term. J. Power Sources 2012, 212, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, R.; Marques, P.; Moura, P.; Freire, F.; Delgado, J.; de Almeida, A.T. Impact of the electricity mix and use profile in the life-cycle assessment of electric vehicles. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 24, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsson, H.; Hall, R.P.; Marsden, G.; Zietsman, J. Sustainable Transportation—Indicators, Frameworks, and Performance Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Springer Texts in Business and Economics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkisz, J.; Pielecha, J.; Radzimirski, S. New Trends in Emission Control in the European Union; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Litman, T.; Burwell, D. Issues in sustainable transportation. Int. J. Glob. Environ. 2006, 6, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehlhart, G.; Möck, A.; Goldman, D. Effects on ELV Waste Management as a Consequence of the Decisions from the Stockholm Convention on Decabde, Dokument Öko-Institut, 2018, Fryburg. Available online: https://www.oeko.de/fileadmin/oekodoc/ACEA-DecaBDE-final-report.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Taszka, S.; Domergue, S. Prime à la Conversion des Véhicules Particuliers en 2018. Une Évaluation Socio-Économique ex Post; Ministère de la Transition Écologique et Solidaire: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bäumer, M.; Hautzinger, H.; Pfeiffer, M.; Stock, W.; Lenz, B.; Kuhnimhof, T.; Köhler, K. Fahrleistungserhebung 2014—Inländerfahrleistung; Berichte der Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen: Brema, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bieker, G. A Global Comparison of the Life-Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Combustion Engine and Electric Passenger Cars; ICCT: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Volume 49, p. 847129-102. [Google Scholar]

- European Automobile Manufacturers Association, Report: Vehicles in Use—Europe 2019. Available online: https://www.acea.be/uploads/publications/ACEA_Report_Vehicles_in_use-Europe_2019.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Kraftfahrt-Bundesamt, Raport: Fahrzeugzulassungen (FZ). Available online: https://www.kba.de/SharedDocs/Publikationen/DE/Statistik/Fahrzeuge/FZ/Fachartikel/alter_20110415.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Dun, C.; Horton, G.; Kollamthodi, S. Improvements to the Definition of Lifetime Mileage of Light Duty Vehicles; Report for European Commission—DG Climate Action, 2015, Brussels; Ricardo-AEA: London, UK, 2015; Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2016-11/ldv_mileage_improvement_en.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Baron, Y.; Kosinska-Terrade, I.; Loew, C.; Kohler, A.; Moch, K.; Sutter, J.; Graulich, K.; Adjei, F.; Mehlhart, G.; Hermann, A. Study to Support the Impact Assessment for the Review of Directive 2000/53/EC on End-of-Life Vehicles. Document Öeko-Institut, 2023, Brussels. Available online: https://mehlhart-consulting.de/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/ELV_IA_supporting-study_final_report_20230613_final.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- United Nations Environment Program. Used Vehicles and the Environment: A Global Overview of Used Light Duty Vehicles—Flow, Scale and Regulation; United Nations Environment Program: Nairobi, Kenya; Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/34175 (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Díaz, S.; Mock, P.; Bernard, Y.; Bieker, G.; Pniewska, I.; Ragon, P.L.; Rodríguez, F.; Tietge, U.; Wappelhorst, S. European Vehicle Market Statistics 2020/21; ICCT: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Harlow, J.E.; Ma, X.; Li, J.; Logan, E.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Ma, L.; Glazier, S.L.; Cormier, M.M.E.; Genovese, M.; et al. A wide range of testing results on an excellent lithium-ion cell chemistry to be used as benchmarks for new battery technologies. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, 3031–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Few, S.; Schmidt, O.; Offer, G.J.; Brandon, N.; Nelson, J.; Gambhir, A. Prospective improvements in cost and cycle life of off-grid lithium-ion battery packs: An analysis informed by expert elicitations. Energy Policy 2018, 114, 578–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciez, R.E.; Whitacre, J.F. Examining different recycling processes for lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argonne National Laboratory, The Greenhouse Gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy Use in Transportation Model (GREET). Available online: https://greet.es.anl.gov/index.php (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Słowik, P.; Lutsey, N.; Hsu, C.W. How Technology, Recycling, and Policy Can Mitigate Supply Risks to the Long-Term Transition to Zero-Emission Vehicles; ICCT: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Guinée, J.; Heijungs, R.; Huppes, G.; Zamagni, A.; Masoni, P.; Buonamici, R.; Rydberg, T. Life Cycle Assessment: Past, present, and future. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bałdowska-Witos, P.; Piasecka, I.; Flizikowski, J.; Tomporowski, A.; Idzikowski, A.; Zawada, M. Life Cycle Assessment of Two Alternative Plastics for Bottle Production. Materials 2021, 14, 4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kłos, Z.; Kalkowska, J.; Kasprzak, J. Towards a Sustainable Future—Life Cycle Management. Challenges and Prospects; Springer Nature: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamagni, A.; Buttol, P.; Porta, P.L.; Buonamici, R.; Masoni, P.; Guinée, J.; Heijungs, R.; Ekvall, T.; Bersani, R.; Bieńkowska, A.; et al. Critical Review of the Current Research Needs and Limitations Related to ISO-LCA Practice, ENEA, Italian National Agency for New Technologies; Energy and the Environment: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 14040:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- ISO 14044:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Heijungs, R.; Guinée, J.B.; Huppes, G.; Lankreijer, R.M.; Udo de Haes, H.; Wegener, A.; Sleeswijk, A. Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Products. Part I: Guide. Part II: Backgrounds; Multicopy Press: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Klöpffer, W.; Grahl, B. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): A Guide to Best Practice; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasecka, I.; Tomporowski, A.; Piotrowska, K. Environmental analysis of post-use management of car tires. Przemysł Chem. 2018, 97, 1649–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowska, K.; Kruszelnicka, W.; Bałdowska-Witos, P.; Kasner, R.; Rudnicki, J.; Tomporowski, A.; Flizikowski, J.; Opielak, M. Assessment of the Environmental Impact of a Car Tire throughout Its Lifecycle Using the LCA Method. Materials 2019, 12, 4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, C.; Hofer, J.; Althaus, H.-J.; Del Duce, A.; Simons, A. The environmental performance of current and future passenger vehicles: Life cycle assessment based on a novel scenario analysis framework. Appl. Energy 2015, 157, 871–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroma, M.S.; Costa, D.; Philippot, M.; Cardellini, G.; Hosen, M.S.; Coosemans, T.; Messagie, M. Life cycle assessment of battery electric vehicles: Implications of future electricity mix and different battery end-of-life management. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 831, 154859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekker, E.; Zijp, M.C.; van de Kamp, M.E.; Temme, E.H.M.; van Zelm, R. A taste of the new ReCiPe for life cycle assessment: Consequences of the updated impact assessment method on food product LCAs. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 2315–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Steinmann, Z.J.N.; Elshout, P.M.F.; Stam, G.; Verones, F.; Vieira, M.; Zijp, M.; Hollander, A.; van Zelm, R. ReCiPe2016: A harmonised life cycle impact assessment method at midpoint and endpoint level. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2017, 22, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamnatou, C.; Chemisana, D. Evaluation of photovoltaic-green and other roofing systems by means of ReCiPe and multiple life cycle–based environmental indicators. Build. Environ. 2015, 93, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashedi, A.; Khanam, T. Life cycle assessment of most widely adopted solar photovoltaic energy technologies by mid-point and end-point indicators of ReCiPe method. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 29075–29090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallela, G.; Mohamed, S.I. Environmental impact analysis of organic phase change materials for energy storage by using ReCiPe endpoint method. Mater. Today Proceedings. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, M.; Sudhakar, M. Carbon Utilization: Applications for the Energy Industry; Springer: Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, A. Time-adjusted global warming potentials for LCA and carbon footprints. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2012, 8, 1042–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, I.; Schmidt, J.H. Methane oxidation, biogenic carbon, and the IPCC’s emission metrics. Proposal for a consistent greenhouse-gas accounting. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 21, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frischknecht, R.; Wyss, F.; Büsser-Knöpfel, S.; Lützkendorf, T.; Balouktsi, M. Cumulative energy demand in LCA: The energy harvested approach. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2015, 20, 957–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig, R.; Fullana-Palmer, P.; Baquero, G.; Riba, J.R.; Bala, A.A. Cumulative Energy Demand indicator (CED), life cycle based, for industrial waste management decision making. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 2789–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scipioni, A.; Niero, M.; Mazzi, A.; Manzardo, A.; Piubello, S. Significance of the use of non-renewable fossil CED as proxy indicator for screening LCA in the beverage packaging sector. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borda, F.; Ingarao, G.; Ambrogio, G.; Gagliardi, F. Cumulative energy demand analysis in the current manufacturing and end-of-life strategies for a polymeric composite at different fibre-matrix combinations. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 449, 141775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neha, K.; Vinita, C.; Sonal, T. Life Cycle Analysis of Electric Vehicles; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinée, J. Handbook on Life Cycle Assessment: Operational Guide to the ISO Standards; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, M.; Xu, Z. Application of Life Cycle Assessment on Electronic Waste Management: A Review. Environ. Manag. 2017, 59, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acero, A.P.; Rodríguez, C.; Ciroth, A. Impact Assessment Methods in Life Cycle Assessment and Their Impact Categories; GreenDelta GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rebitzer, G.; Loerincik, Y.; Jolliet, O. Input-output life cycle assessment: From theory to applications. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2002, 7, 174–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frischknecht, R.; Krebs, L.; Dinkel, F.; Kägi, T.; Stettler, C.; Zschokke, M.; Braunschweig, A.; Ahmadi, M.; Itten, R.; Stucki, M. Swiss Eco-Factors 2021 According to the Ecological Scarcity Method. Methodological Fundamentals and Their Application in Switzerland; Federal Office for the Environment: Bern, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, P.J.; Shahiduzzaman, M.; Stern, D.I. Carbon dioxide emissions in the short run: The rate and sources of economic growth matter. Glob. Environ. Change 2015, 33, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsfold, P.; Townshend, A.; Poole, C.; Miró, M. Encyclopedia of Analytical Science, Reference Module in Chemistry, Molecular Sciences and Chemical Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig, A.; Arand, M.; Epe, B.; Guth, S.; Jahnke, G.; Lampen, A.; Martus, H.J.; Monien, B.; Rietjens, I.M.; Schmitz-Spanke, S.; et al. Mode of action-based risk assessment of genotoxic carcinogens. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 1787–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onat, N.C.; Kucukvar, M.; Tatari, O. Conventional, hybrid, plug-in hybrid or electric vehicles? State-based comparative carbon and energy footprint analysis in the United States. Appl. Energy 2015, 150, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Balthasar, F.; Tait, N.; Riera-Palou, X.; Harrison, A. A new comparison between the life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of battery electric vehicles and internal combustion vehicles. Energy Policy 2012, 44, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bembenek, M.; Melnyk, V.; Karwat, B.; Hnyp, M.; Kowalski, Ł.; Mosora, Y. Jerusalem Artichoke as a Raw Material for Manufacturing Alternative Fuels for Gasoline Internal Combustion Engines. Energies 2024, 17, 2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Li, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Meng, O.; Yu, Y.; Jin, Y.; Gao, X.; Guo, X.; Jia, L. Study on the regulation of performance and Hg0 removal mechanism of MIL-101(Fe)-derived carbon materials. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 379, 134939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Cheng, P.; Li, Z.; Fan, C.H.; Wen, J.; Yu, Y.; Jia, L. Efficient removal of gaseous elemental mercury by Fe-UiO-66@BC composite adsorbent: Performance evaluation and mechanistic elucidation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 372, 133463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhail, M.; Raj, S.; Zheng, G.; Xie, S.; Wang, C.H.; Dong, X.; Lin, Y.; Wang, C.H.; Junejo, N. Applications, classifications, and challenges: A comprehensive evaluation of recently developed metaheuristics for search and analysis. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhail, M.; Lin, H.; Xie, S.; Dong, X.; Lin, Y.; Shiva, C.H.; Fendzi Mbasso, W. An intelligent hybrid grey wolf-particle swarm optimizer for optimization in complex engineering design problem. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| A and B Segment | Human Health | Ecosystems | Raw Material Resources | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | ICEV gasoline | storage | 1.72 × 103 | 1.20 × 102 | 5.66 × 100 | 1.85 × 103 |

| recycling | 5.04 × 102 | −1.41 × 100 | 4.96 × 100 | 5.08 × 102 | ||

| ICEV diesel oil | storage | 1.74 × 103 | 1.20 × 102 | 5.68 × 100 | 1.87 × 103 | |

| recycling | 5.28 × 102 | −9.82 × 10−1 | 4.98 × 100 | 5.32 × 102 | ||

| ICEV CNG | storage | 1.77 × 103 | 1.22 × 102 | 5.74 × 100 | 1.90 × 103 | |

| recycling | 5.78 × 102 | 3.28 × 100 | 5.05 × 100 | 5.86 × 102 | ||

| BEV | storage | 2.60 × 103 | 1.39 × 102 | 1.19 × 101 | 2.75 × 103 | |

| recycling | −1.07 × 103 | −2.19 × 102 | 9.97 × 100 | −1.27 × 103 | ||

| 2050 | ICEV gasoline | storage | 1.59 × 103 | 1.16 × 102 | 5.42 × 100 | 1.71 × 103 |

| recycling | 3.48 × 102 | −6.06 × 100 | 4.72 × 100 | 3.48 × 102 | ||

| ICEV diesel oil | storage | 1.61 × 103 | 1.16 × 102 | 5.46 × 100 | 1.74 × 103 | |

| recycling | 3.72 × 102 | −5.62 × 100 | 4.74 × 100 | 3.70 × 102 | ||

| ICEV CNG | storage | 1.64 × 103 | 1.18 × 102 | 5.51 × 100 | 1.76 × 103 | |

| recycling | 4.06 × 102 | −3.04 × 100 | 4.81 × 100 | 4.08 × 102 | ||

| BEV | storage | 2.40 × 103 | 1.39 × 102 | 1.12 × 101 | 2.55 × 103 | |

| recycling | −9.61 × 102 | −1.88 × 102 | 9.33 × 100 | −1.14 × 103 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piotrowska, K.; Piasecka, I.; Opielak, M. Life Cycle Assessment of Small Passenger Cars in the Context of Smart Grid Integration and Sustainable Power System Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310788

Piotrowska K, Piasecka I, Opielak M. Life Cycle Assessment of Small Passenger Cars in the Context of Smart Grid Integration and Sustainable Power System Development. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310788

Chicago/Turabian StylePiotrowska, Katarzyna, Izabela Piasecka, and Marek Opielak. 2025. "Life Cycle Assessment of Small Passenger Cars in the Context of Smart Grid Integration and Sustainable Power System Development" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310788

APA StylePiotrowska, K., Piasecka, I., & Opielak, M. (2025). Life Cycle Assessment of Small Passenger Cars in the Context of Smart Grid Integration and Sustainable Power System Development. Sustainability, 17(23), 10788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310788