Revisiting the Technology–Organization–Environment Framework: Disruptive Technologies as Catalysts of Digital Transformation in the Turkish Banking Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

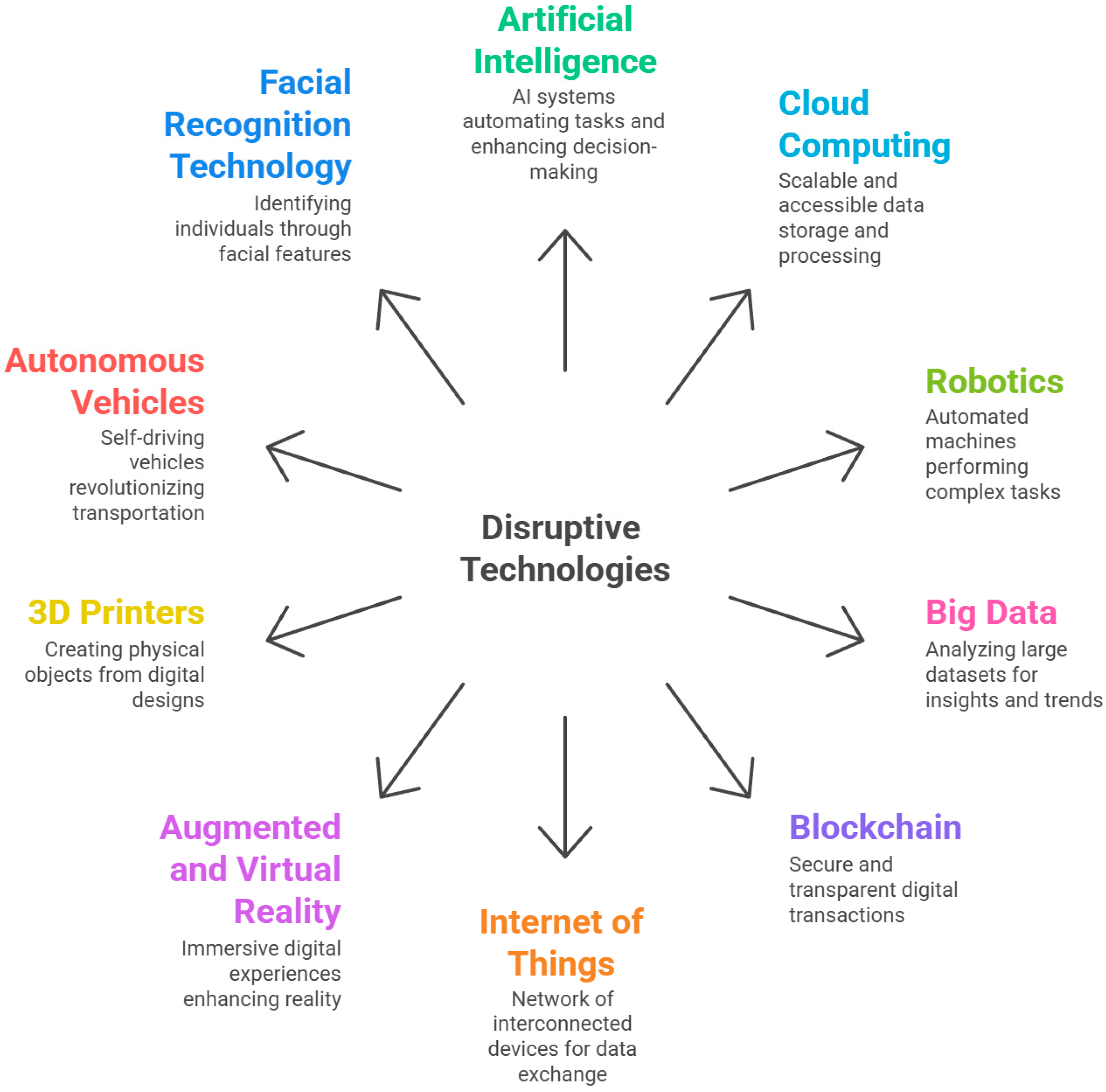

2.1. Disruptive Technologies

2.2. Digital Transformation and Organizations

2.3. TOE Framework

3. Materials and Methods

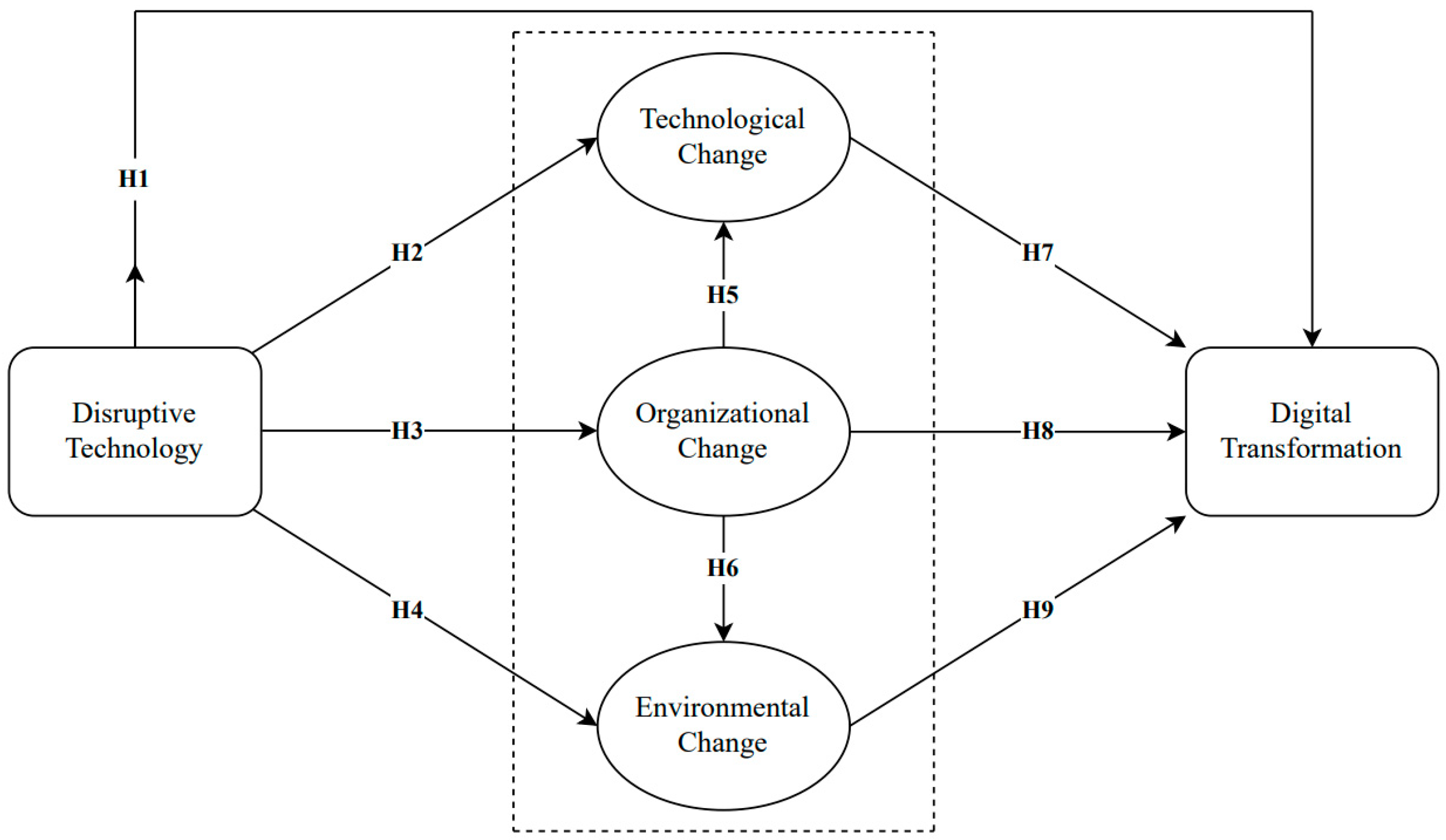

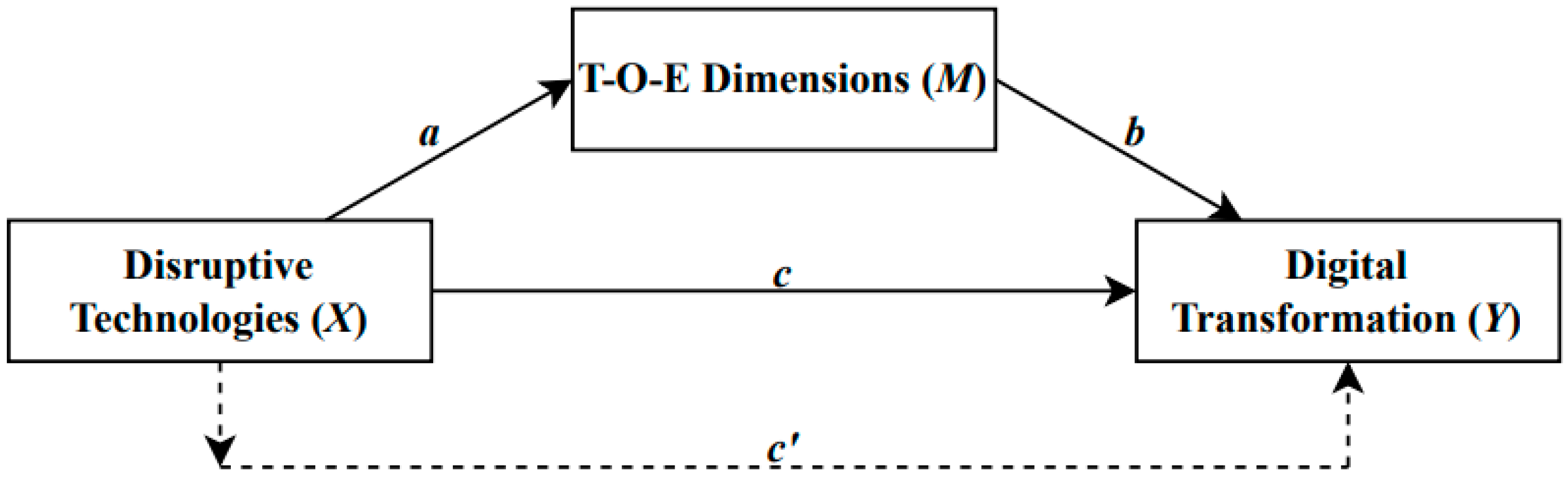

3.1. Research Model and Hypotheses Development

3.1.1. Disruptive Technologies and Digital Transformation

3.1.2. Disruptive Technologies and TOE

3.1.3. TOE Dimensions

3.1.4. TOE and Digital Transformation

3.2. Sampling Process and Data Collection Method

3.3. Data Analysis Methods

4. Results

4.1. Participant Demographics

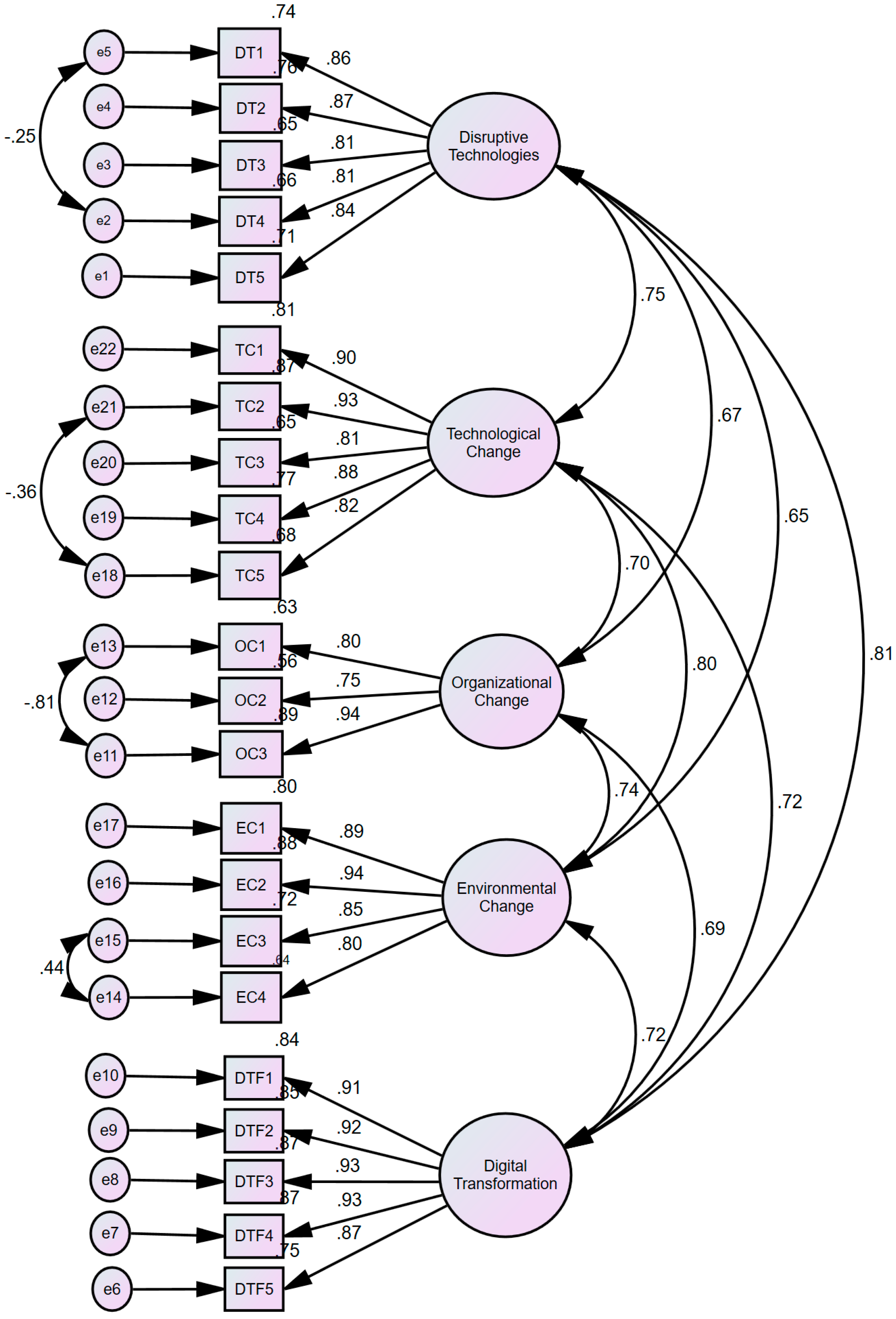

4.2. Reliability and Validity Values of the Factors

4.3. Measurement Model Results and Goodness-of-Fit Indices

4.4. Discriminant Validity

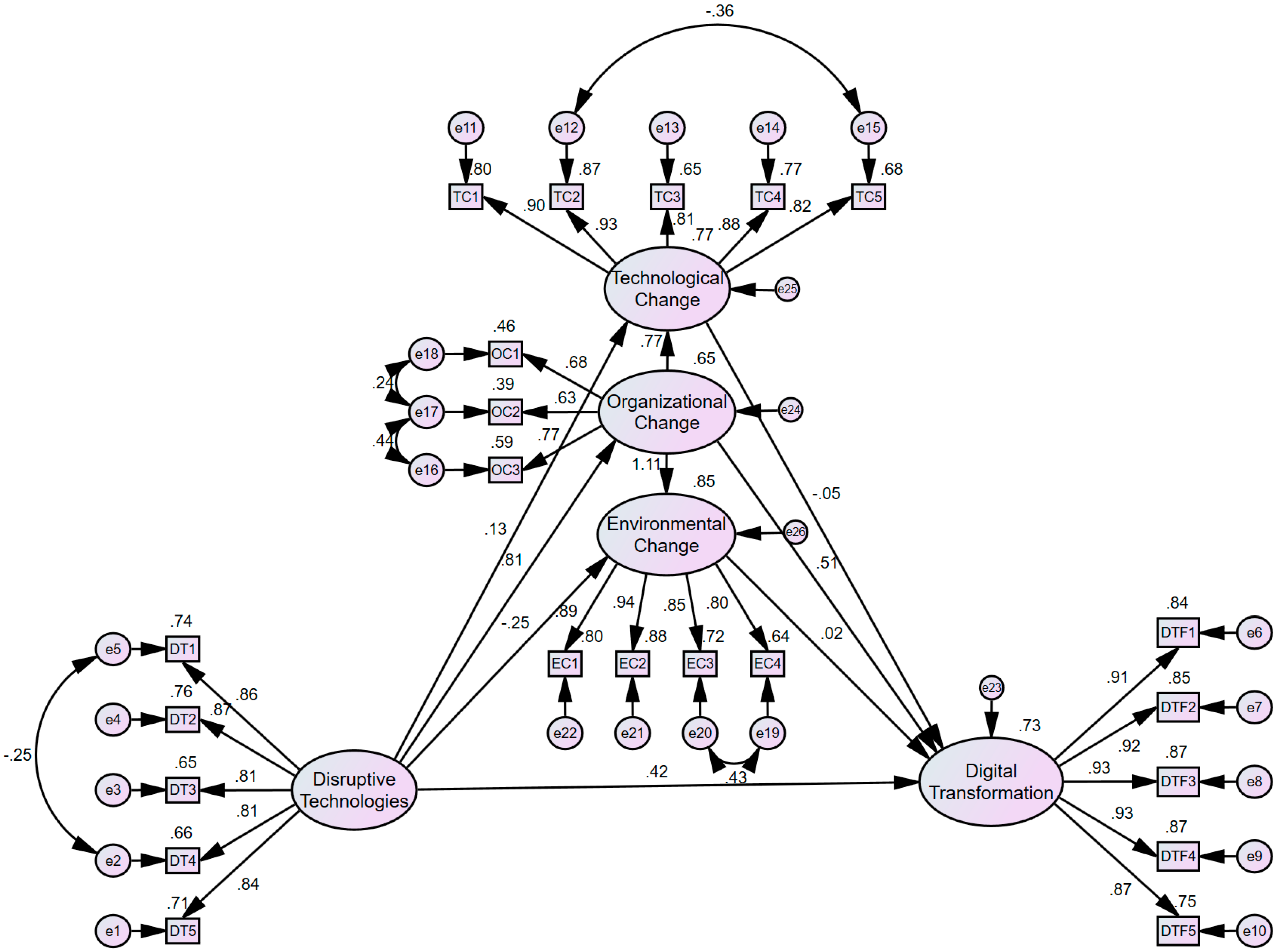

4.5. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

4.6. Findings of the Mediation Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Theoretical Contributions

7. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Constructs | Descriptions | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Disruptive Technology | Our institution makes significant use of e-learning technology. | [5] |

| Our institution makes significant use of artificial intelligence technology. | ||

| Cloud computing technology is used extensively in our institution. | ||

| Our institution makes extensive use of robotic technology. | ||

| Our institution makes extensive use of big data technologies. | ||

| Technological Change | Technologies used in recent years have changed. | [5] |

| Changes in working methods will be dependent on technological changes. | ||

| Changing the technology used will have a positive impact on the organization. | ||

| The technological infrastructure is constantly changing. | ||

| Our institution has full authority to change the technology used. | ||

| Organizational Change | External conditions necessitate organizational change within our institution. | [5] |

| Our institution has undergone organizational change in recent years. | ||

| Our institution has undertaken numerous initiatives aimed at continuous change in recent periods. | ||

| Environmental Change | Our organization operates in an environment where technological changes are rapidly evolving. | [35] |

| Technological changes present significant opportunities for the organization’s growth. | ||

| The demands of those receiving services from the organization regarding products and services frequently change. | ||

| Those receiving services from the organization tend to seek out new products and services. | ||

| Digital Transformation | Our institution has taken action in response to digital transformation efforts and has the ability to finance the process. | [36] |

| Our institution carries out strategic initiatives to create scalable, flexible, and value-generating operations aimed at achieving digital transformation. | ||

| Our institution carries out strategic initiatives to leverage digital information to provide better data optimization. | ||

| Our organization continuously executes strategic initiatives to monitor research and applications of digital platforms and technologies. | ||

| Our organization establishes intensive interactive digital connections with domestic and international organizations. |

References

- Adama, H.E.; Okeke, C.D. Digital Transformation as a Catalyst for Business Model Innovation: A Critical Review of Impact and Implementation Strategies. Magna Sci. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 10, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanelt, A.; Bohnsack, R.; Marz, D.; Antunes Marante, C. A Systematic Review of the Literature on Digital Transformation: Insights and Implications for Strategy and Organizational Change. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 1159–1197, Correction in J. Manag. Stud. 2022, 59, 583. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plekhanov, D.; Franke, H.; Netland, T.H. Digital Transformation: A Review and Research Agenda. Eur. Manag. J. 2023, 41, 821–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, J.L.; Christensen, C.M. Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1995, 73, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Aawawdeh, R. The Impact of Implementing Disruptive Technology on Organizational Change. Master’s Thesis, University of Petra, Amman, Jordan, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zighan, S. Disruptive Technology from an Organizational Management Perspective. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Business Analytics for Technology and Security (ICBATS), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 16–17 February 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faro, B. Continuous Transformation of Government Agencies in the Digital Era: A Technological and Non-Technological Assessment. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.; Hwang, J. Disruptive Technologies for Knowledge Management: Bibliometric Review and Patent Analysis. Kybernetes 2024, 53, 6977–7002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabakus, A.K.; Bahcekapili, E.; Ayaz, A. The Effect of Digital Literacy on Technology Acceptance: An Evaluation on Administrative Staff in Higher Education. J. Inf. Sci. 2025, 51, 930–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Geiggar, C. Business Sustainability: A Qualitative Study Exploring Digital Transformation as a Key Driver for Organizational Leaders. Ph.D. Thesis, National University, San Diego, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Elia, G.; Solazzo, G.; Lerro, A.; Pigni, F.; Tucci, C.L. The Digital Transformation Canvas: A Conceptual Framework for Leading the Digital Transformation Process. Bus. Horiz. 2024, 67, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornatzky, L.G.; Fleischer, M. Processes of Technological Innovation; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Shiau, W.L.; Liu, C.; Zhou, M.; Yuan, Y. Insights into customers’ psychological mechanism in facial recognition payment in offline contactless services: Integrating belief-attitude-intention and TOE-I frameworks. Internet Res. 2023, 33, 344–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.F.; Alam, M.M.; Rahmat, M.K.; Shahid, M.K.; Aslam, M.; Salim, N.A.; Al-Abyadh, M.H.A. Leading edge or bleeding edge: Designing a framework for the adoption of AI technology in an educational organization. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, G.; Mladenow, A.; Strauss, C.; Schaffhauser-Linzatti, M. Smart Contracts and Internet of Things: A Qualitative Content Analysis Using the Technology–Organization–Environment Framework to Identify Key Determinants. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 160, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsetoohy, O.; Ayoun, B.; Arous, S.; Megahed, F.; Nabil, G. Intelligent Agent Technology: What Affects Its Adoption in Hotel Food Supply Chain Management? J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2019, 10, 286–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, R.K.; Swain, S. Adoption of Technology Applications in Organized Retail Outlets in India: A TOE Model. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2022, 26, 1482–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, H. Navigating the Digital Landscape: An Exploration of the Relationship Between Technology-Organization-Environment Factors and Digital Transformation Adoption in SMEs. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 21582440241276198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.-H. Investigating Driving Factors of Digital Transformation in the Vietnam Shipping Companies: Applied for TOE Framework. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 21582440241301210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajili Ben Youssef, W.; Bouebdallah, N.; Long, H. Factors Influencing Generative Artificial Intelligence Adoption in Vietnam’s Banking Sector: An Empirical Study. Financ. Innov. 2025, 11, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Smadi, M.O. Factors Driving Digital Transformation: Technological, Organizational, and Environmental Perspectives from Jordanian Banks. Banks Bank Syst. 2025, 20, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annisa, S.; Sutjipto, M.R. Technology, Organization, Environment, and Digital Transformation for Sustainability. J. Ilm. Manaj. Kesatuan 2025, 13, 2591–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, C.M. The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Broekhuizen, T.; Bart, Y.; Bhattacharya, A.; Dong, J.Q.; Fabian, N.; Haenlein, M. Digital Transformation: A Multidisciplinary Reflection and Research Agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiyere, A.; Salmela, H.; Tapanainen, T. Digital Transformation and the New Logics of Business Process Management. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 29, 238–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, A.; Imran, F.; Helo, P.; Kantola, J. Strategic Design of Culture for Digital Transformation. Long Range Plan. 2024, 57, 102415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Gao, Q.; Peng, C.; Yang, K.; Liu, R. A Study on the Impact of Different Organizational Levels on Digital Transformation in Enterprises. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladimirov, Z.D.; Harizanova, O.B. The Mediating Role of Organizational Factors between Environmental Changes and SMEs’ Digital Transformation. Cent. Eur. Manag. J. 2025, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdurrahman, A.; Gustomo, A.; Prasetio, E.A. Impact of Dynamic Capabilities on Digital Transformation and Innovation to Improve Banking Performance: A TOE Framework Study. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakaş, E.Ö. Digital Transformational Leadership and Organizational Agility in Digital Transformation: Structural Equation Modelling of the Moderating Effects of Digital Culture and Digital Strategy. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2024, 35, 100517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’Dri, A.B.; Su, Z. Successful Configurations of Technology-Organization-Environment Factors in Digital Transformation: Evidence from Exporting Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in the Manufacturing Industry. Inf. Manag. 2024, 61, 104030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, E.; Akyuz, I.; Omay, G.G.; Bosat, M. Defining health mavens on demographic characteristics: A pilot study in Istanbul. Eur. Sci. J. 2016, 12, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Altunışık, R.; Coşkun, R.; Bayraktaroğlu, S.; Yıldırım, E. Sosyal Bilimlerde Araştırma Yöntemleri: SPSS Uygulamalı (Research Methods in Social Sciences: Applied with SPSS); Sakarya Yayıncılık: Sakarya, Turkey, 2015. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Lei, X. How Organizational Unlearning Leverages Digital Process Innovation to Improve Performance: The Moderating Effects of Smart Technologies and Environmental Turbulence. Technol. Soc. 2023, 75, 102395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sağlam, M. İşletmelerde Geleceğin Vizyonu Olarak Dijital Dönüşümün Gerçekleştirilmesi ve Dijital Dönüşüm Ölçeğinin Türkçe Uyarlaması (Realization of Digital Transformation as a Vision of the Future in Businesses and Turkish Adaptation of the Digital Transformation Scale). İstanbul Ticaret Univ. Sos. Bilim. Derg. 2021, 20, 395–420. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gürbüz, S. AMOS ile Yapısal Eşitlik Modellemesi (Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS); Seçkin Yayıncılık: Ankara, Turkey, 2024. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Saidi, S.S.; Siew, N.M. Investigating the Validity and Reliability of Survey Attitude towards Statistics Instrument among Rural Secondary School Students. Int. J. Educ. Methodol. 2019, 5, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, H.; Bircan, H. Ortaokul Öğrencilerinin Başarı Odaklı Motivasyonlarının Demografik Özelliklere Göre Belirlenmesi (Determining the Success-Oriented Motivations of Secondary School Students According to Demographic Characteristics). Turk. Res. J. Acad. Soc. Sci. 2023, 5, 134–144. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Gürcüoğlu, S.; Köseoğlu, İ. Kamu Çalışanlarında Yapay Zekâ Algısını Ölçmeye Yönelik Ölçek Geliştirme (Scale Development to Measure the Perception of Artificial Intelligence Among Public Employees). Karamanoğlu Mehmetbey Univ. J. Soc. Econ. Res. 2024, 26, 1009–1024. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Zang, W.; Li, L.; Yi, Z. Unveiling the Multifaceted Driving Mechanism of Digital Transformation in the Construction Industry: A System Adaptation Perspective. Systems 2024, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the Fit of Structural Equation Models: Tests of Significance and Descriptive Goodness-of-Fit Measures. Methods Psychol. Res. Online 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, W.M. A Typology of Validity: Content, Face, Convergent, Discriminant, Nomological and Predictive Validity. J. Trade Sci. 2024, 12, 155–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albahri, A.S.; Alnoor, A.; Zaidan, A.A.; Albahri, O.S.; Hameed, H.; Zaidan, B.B.; Yass, A.A. Based on the Multi-Assessment Model: Towards a New Context of Combining the Artificial Neural Network and Structural Equation Modelling: A Review. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 153, 111445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffaele, B.; Biagioli, V.; Cirillo, L.; De Marinis, M.G.; Matarese, M. Cross-Validation of the Self-Care Ability Scale for Elderly (SASE) in a Sample of Italian Older Adults. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2018, 32, 1398–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komal, B.; Janjua, U.I.; Anwar, F.; Madni, T.M.; Cheema, M.F.; Malik, M.N.; Shahid, A.R. The Impact of Scope Creep on Project Success: An Empirical Investigation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 125755–125775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffield, D.; Butler, C.W.; Richardson, M. Improving Nature Connectedness in Adults: A Meta-Analysis, Review and Agenda. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y. Statistical Notes for Clinical Researchers: Understanding Standard Deviations and Standard Errors. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2013, 38, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hox, J.J.; Bechger, T.M. An Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling. Fam. Sci. Rev. 1998, 11, 354–373. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.S.; Lai, K.H.; Cheng, T.E. Application of Structural Equation Modeling to Evaluate the Intention of Shippers to Use Internet Services in Liner Shipping. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 180, 845–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, G.; Jonker, L. An Introduction to Inferential Statistics: A Review and Practical Guide. Radiography 2011, 17, e1–e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS Procedures for Estimating Indirect Effects in Simple Mediation Models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roblek, V.; Meško, M.; Pušavec, F.; Likar, B. The Role and Meaning of the Digital Transformation as a Disruptive Innovation on Small and Medium Manufacturing Enterprises. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 592528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszak, C.; Pałys, M. Disruptive Technologies as a Driver to Organizational Success: Organizational Culture Perspective. In Proceedings of the 56th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 3–6 January 2023; pp. 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ji, J.; Qiao, Y.; Huang, J. How and When Does Digital Transformation Promote Technological Innovation Performance? A Study of Chinese High-Tech Firms. Technovation 2025, 146, 103294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadri, H.; Yitmen, I.; Tagliabue, L.C.; Westphal, F.; Tezel, A.; Taheri, A.; Sibenik, G. Integration of Blockchain and Digital Twins in the Smart Built Environment Adopting Disruptive Technologies-A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vural, M.F. Süreksiz Teknolojilere ve Tamamlayıcı Yeniliklere Çalışanlar Nasıl Uyum Sağlar? (How Do Employees Adapt to Discontinuous Technologies and Complementary Innovations?). Yönetim Bilimleri Derg. 2024, 22, 1925–1945. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindel Sibassaha, J.L.; Pea-Assounga, J.B.B.; Bambi, P.D.R. Influence of Digital Transformation on Employee Innovative Behavior: Roles of Challenging Appraisal, Organizational Culture Support, and Transformational Leadership Style. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1532977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q.; Parveen, S.; Yaacob, H.; Zaini, Z. The Management of Industry 4.0 Technologies and Environmental Assets for Optimal Performance of Industrial Firms in Malaysia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 52964–52983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.; Lu, H.; Ye, Y.; Wu, H. Does the Firms’ Digital Transformation Drive Environmental Innovation in China? Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 2139–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopeinig, J.; Woschank, M.; Olipp, N. Industry 4.0 Technologies and Their Implications for Environmental Sustainability in the Manufacturing Industry. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 232, 2777–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewapatarakul, D.; Ueasangkomsate, P. Digital Organizational Culture, Organizational Readiness, and Knowledge Acquisition Affecting Digital Transformation in SMEs from Food Manufacturing Sector. Sage Open 2024, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Shan, H.; Xian, P.; Xu, X.; Li, N. Impact of Digital Transformation on Green Innovation in Manufacturing under Dual Carbon Targets. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q. The Influence of Organizational Policies on Firm Environmental Performance through Sustainable Technologies and Innovation and Stakeholder Concerns. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsios, F.; Giatsidis, I.; Kamariotou, M. Digital Transformation and Strategy in the Banking Sector: Evaluating the Acceptance Rate of E-Services. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Shao, X. Research on the Impact of Digital Transformation on the Production Efficiency of Manufacturing Enterprises: Institution-Based Analysis of the Threshold Effect. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 2024, 91, 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, K.; Imran, F.; Butt, A. Digital Transformation and Changes in Organizational Structure: Empirical Evidence from Industrial Organizations. Res. Technol. Manag. 2025, 68, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Bhatia, M.S. Environmental Dynamism, Industry 4.0 and Performance: Mediating Role of Organizational and Technological Factors. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 95, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Hu, D.; Lou, X. The Impact of Digital Transformation on the Sustainable Growth of Specialized, Refined, Differentiated, and Innovative Enterprises: Based on the Perspective of Dynamic Capability Theory. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Song, G.; Zhao, S.; Zuo, C. Market Competition and Digital Transformation in Firms. Finance Res. Lett. 2025, 73, 106684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Frequency (f)/Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 365 (71.2) |

| Female | 148 (28.8) | |

| Age | 20–29 age | 73 (14.2) |

| 30–39 age | 196 (38.2) | |

| 40–49 age | 225 (43.9) | |

| 50 and above | 19 (3.7) | |

| Educational Status | Bachelor’s degree | 386 (75.2) |

| Master’s/Doctorate Degree | 127 (24.8) | |

| Income Level * | <50.000 TL | 53 (10.3) |

| 50.000–75.000 TL | 179 (34.9) | |

| 76.000–100.000 TL | 129 (25.1) | |

| 101.000–125.000 TL | 67 (13.1) | |

| 126.000–150.000 TL | 42 (8.2) | |

| >150.000 TL | 43 (8.4) | |

| Position in the Institution | Senior Executive | 234 (45.6) |

| Middle-Level Manager | 154 (30.0) | |

| Specialist and Technical Staff | 125 (24.4) | |

| Tenure in the Institution | 0–5 years | 126 (24.6) |

| 6–11 years | 96 (18.7) | |

| 12–16 years | 140 (27.3) | |

| 17–21 years | 111 (21.6) | |

| 22–26 years | 31 (6.0) | |

| 27 years and above | 9 (1.8) | |

| Tenure in the Position | 0–5 years | 270 (52.6) |

| 6–11 years | 133 (25.9) | |

| 12–16 years | 82 (16.0) | |

| 17–21 years | 24 (4.7) | |

| 22–26 years | 4 (0.8) | |

| 27 years and above | … (…) | |

| Type of Bank | Public Bank | 256 (49.9) |

| Private Bank | 257 (50.1) |

| Factor | Item | Factor Loadings | AVE | CR | MSV | Cronbach’s Alpha (α) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disruptive Technologies | DT1 | 0.858 | 0.705 | 0.923 | 0.649 | 0.920 |

| DT2 | 0.874 | |||||

| DT3 | 0.807 | |||||

| DT4 | 0.815 | |||||

| DT5 | 0.843 | |||||

| Technological Change | TC1 | 0.897 | 0.756 | 0.939 | 0.633 | 0.935 |

| TC2 | 0.935 | |||||

| TC3 | 0.808 | |||||

| TC4 | 0.877 | |||||

| TC5 | 0.824 | |||||

| Organizational Change | OC1 | 0.796 | 0.694 | 0.871 | 0.543 | 0.835 |

| OC2 | 0.751 | |||||

| OC3 | 0.941 | |||||

| Environmental Change | EC1 | 0.892 | 0.759 | 0.926 | 0.633 | 0.932 |

| EC2 | 0.939 | |||||

| EC3 | 0.847 | |||||

| EC4 | 0.801 | |||||

| Digital Transformation | DT1 | 0.915 | 0.835 | 0.962 | 0.649 | 0.961 |

| DT2 | 0.923 | |||||

| DT3 | 0.932 | |||||

| DT4 | 0.931 | |||||

| DT5 | 0.866 |

| Fit Index | Recommended Value | Model Fit |

|---|---|---|

| CMIN/df | ≤5 | 2.703 |

| GFI | ≥0.90 | 0.912 |

| AGFI | ≥0.80 | 0.886 |

| CFI | ≥0.90 | 0.971 |

| NFI | ≥0.90 | 0.955 |

| RFI | ≥0.85 | 0.947 |

| IFI | ≥0.90 | 0.971 |

| TLI | ≥0.90 | 0.966 |

| RMSEA | ≤0.08 | 0.058 |

| SRMR | ≤0.08 | 0.038 |

| Factor | DT | TC | OC | EC | DT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disruptive Technologies | 0.840 | ||||

| Technological Change | 0.751 | 0.869 | |||

| Organizational Change | 0.674 | 0.701 | 0.833 | ||

| Environmental Change | 0.646 | 0.796 | 0.737 | 0.871 | |

| Digital Transformation | 0.806 | 0.725 | 0.690 | 0.716 | 0.914 |

| Faktor | DT | TC | OC | EC | DT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disruptive Technologies | |||||

| Technological Change | 0.760 | ||||

| Organizational Change | 0.696 | 0.761 | |||

| Environmental Change | 0.654 | 0.795 | 0.795 | ||

| Digital Transformation | 0.810 | 0.738 | 0.707 | 0.721 |

| Fit Index | Recommended Value | Model Fit |

|---|---|---|

| CMIN/df | ≤5 | 2.771 |

| GFI | ≥0.90 | 0.911 |

| AGFI | ≥0.80 | 0.885 |

| CFI | ≥0.90 | 0.970 |

| NFI | ≥0.90 | 0.954 |

| RFI | ≥0.85 | 0.946 |

| IFI | ≥0.90 | 0.970 |

| TLI | ≥0.90 | 0.965 |

| RMSEA | ≤0.08 | 0.059 |

| SRMR | ≤0.08 | 0.038 |

| Hypotheses | Standardized Estimate (β) | Standard Error (S.E.) | Critical Ratio (C.R.) | p-Value | Hypothesis Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disruptive Technologies → Digital Transformation (H1) | 0.422 | 0.093 | 4.464 | 0.000 * | Accepted |

| Disruptive Technologies → Technological Change (H2) | 0.130 | 0.062 | 1.990 | 0.047 ** | Accepted |

| Disruptive Technologies → Organizational Change (H3) | 0.806 | 0.046 | 15.832 | 0.000 * | Accepted |

| Disruptive Technologies → Environmental Change (H4) | −0.250 | 0.080 | −2.743 | 0.006 * | Accepted |

| Organizational Change → Technological Change (H5) | 0.770 | 0.076 | 10.784 | 0.000 * | Accepted |

| Organizational Change → Environmental Change (H6) | 1.113 | 0.104 | 10.418 | 0.000 * | Accepted |

| Technological Change → Digital Transformation (H7) | −0.052 | 0.087 | −0.611 | 0.541 | Rejected |

| Organizational Change → Digital Transformation (H8) | 0.505 | 0.309 | 1.792 | 0.073 | Rejected |

| Environmental Change → Digital Transformation (H9) | 0.023 | 0.186 | 0.139 | 0.889 | Rejected |

| Path | Standardized Estimate (β) | Standard Error (S.E.) | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DT → DTF Total Effect (c) | 0.733 | 0.028 | 26.542 | 0.000 | 0.679 | 0.787 | 0.580 |

| DT → DTF Direct Effect (c′) | 0.449 | 0.036 | 12.495 | 0.000 | 0.378 | 0.519 | 0.466 |

| Total Indirect Effect (c−c′) | 0.284 | 0.044 | - | - | 0.212 | 0.385 | 0.114 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Küçükoğlu, U.; Kabakuş, A.K. Revisiting the Technology–Organization–Environment Framework: Disruptive Technologies as Catalysts of Digital Transformation in the Turkish Banking Sector. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310787

Küçükoğlu U, Kabakuş AK. Revisiting the Technology–Organization–Environment Framework: Disruptive Technologies as Catalysts of Digital Transformation in the Turkish Banking Sector. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310787

Chicago/Turabian StyleKüçükoğlu, Uğur, and Ahmet Kamil Kabakuş. 2025. "Revisiting the Technology–Organization–Environment Framework: Disruptive Technologies as Catalysts of Digital Transformation in the Turkish Banking Sector" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310787

APA StyleKüçükoğlu, U., & Kabakuş, A. K. (2025). Revisiting the Technology–Organization–Environment Framework: Disruptive Technologies as Catalysts of Digital Transformation in the Turkish Banking Sector. Sustainability, 17(23), 10787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310787