GIS-Based Spatial–Temporal Analysis of Development Changes in Rural and Suburban Areas

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

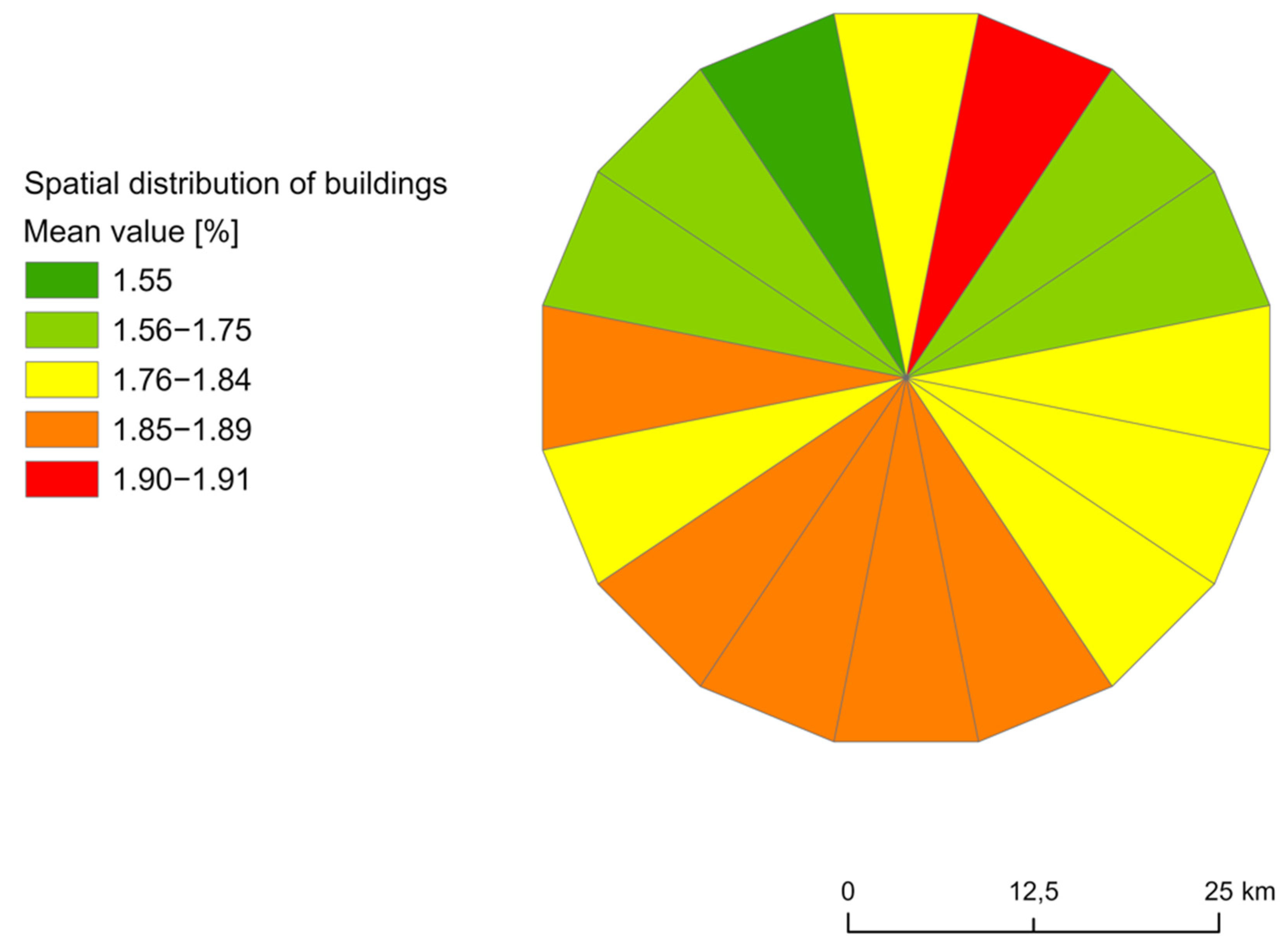

3.1. Main Development Directions in the Suburban and Rural Zones of the City of Białystok

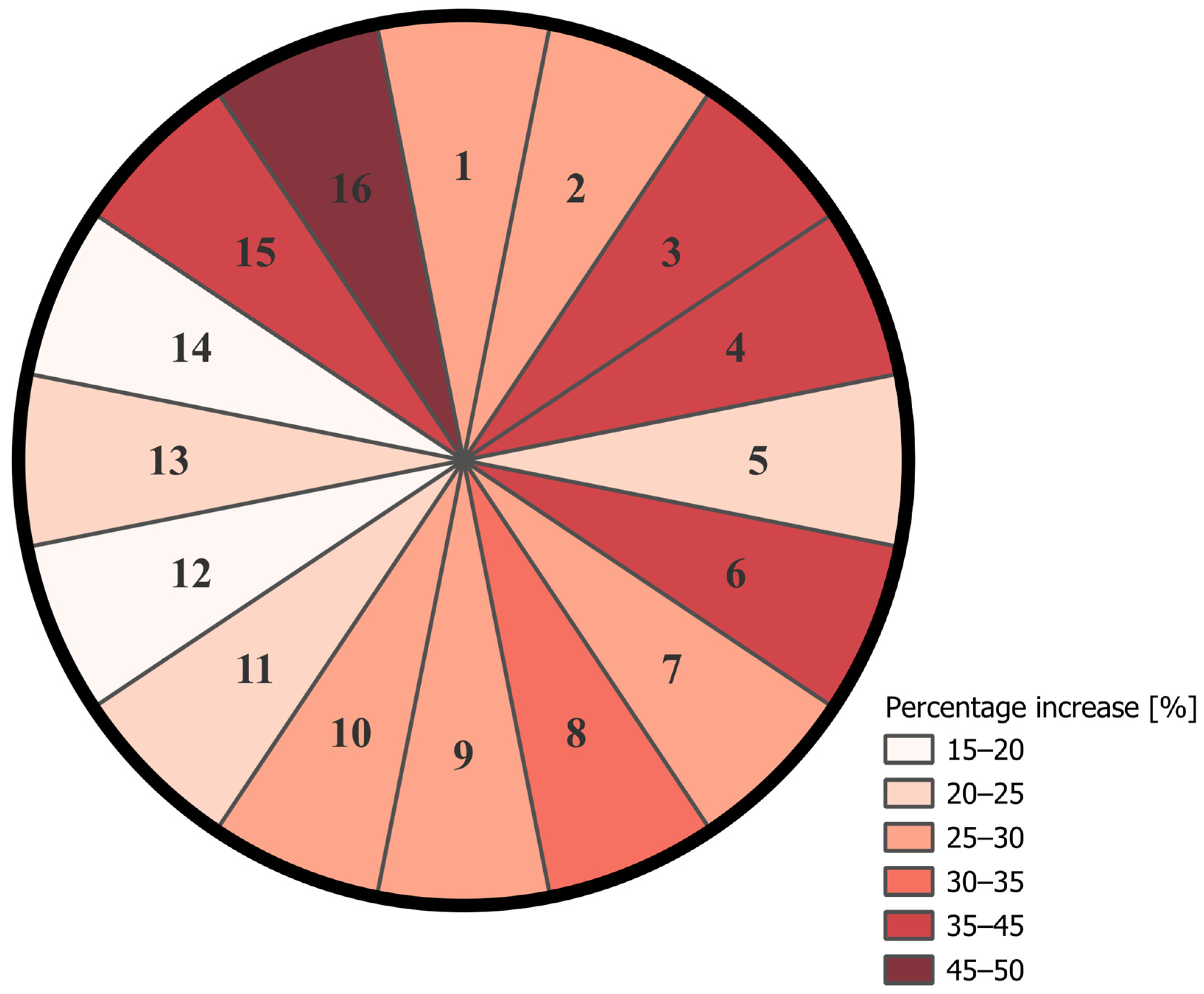

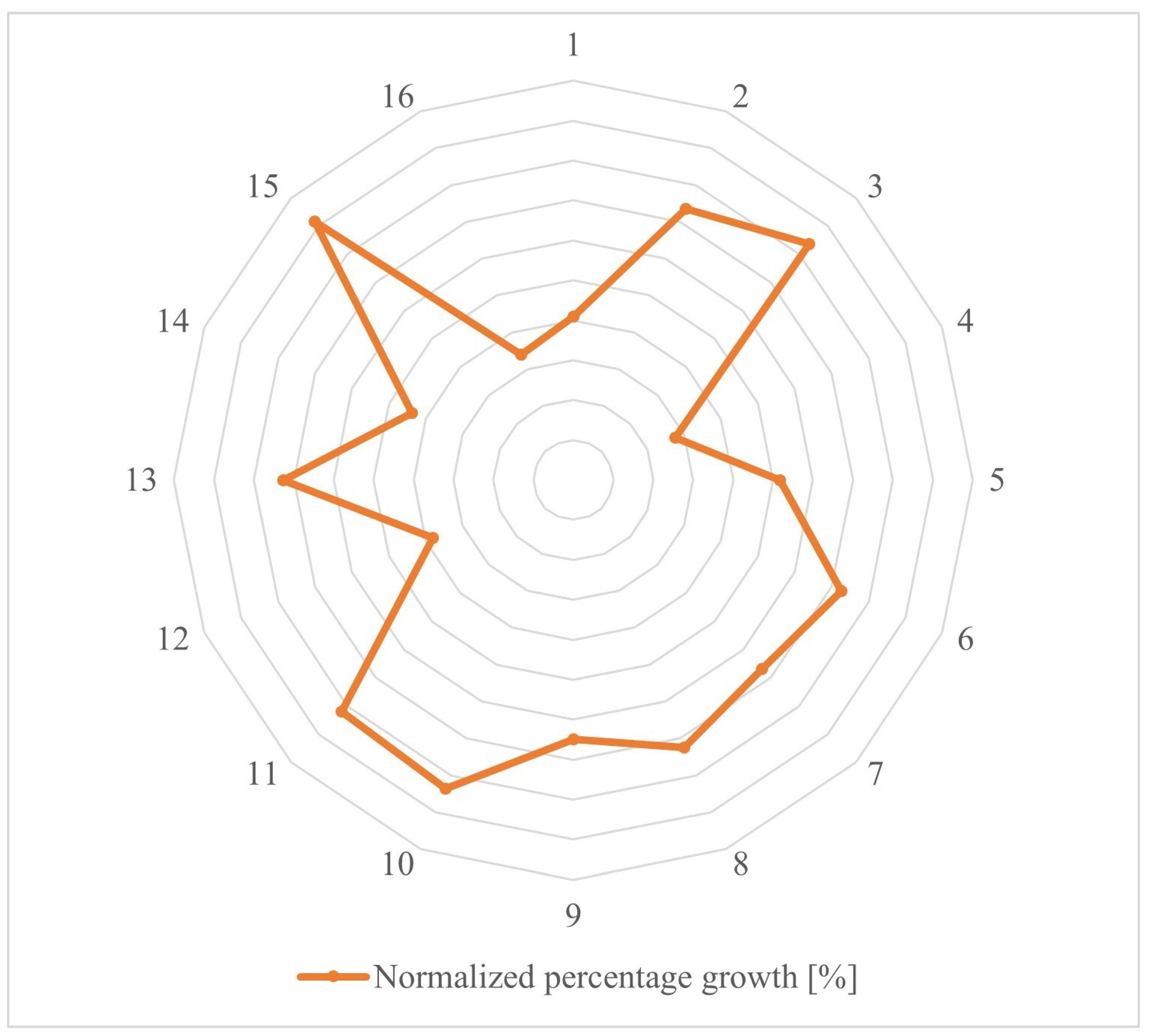

3.2. Dynamics of Residential Development from a Radial Perspective

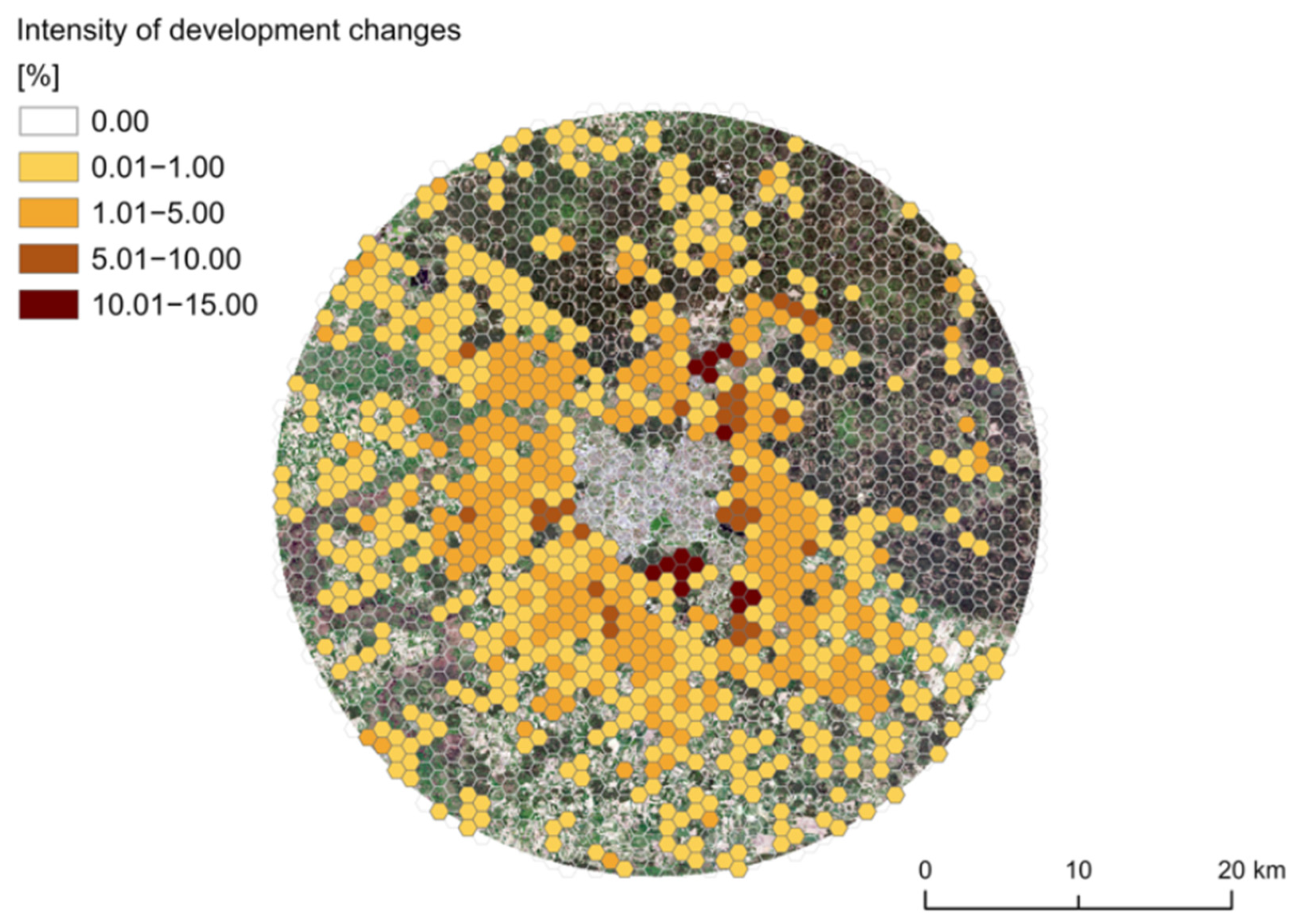

3.3. The Intensity of Development Changes in a Grid System Based on Hexagonal Fields

3.4. Correlation of Residential Development Intensity in Białystok’s Suburban Zone

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- A multivariate analytical approach—combining analyses at various levels of detail (global, directional, and local) is recommended, as this enables a comprehensive interpretation of suburbanisation processes. This approach allows for the identification of general and regional development trends, which are essential from the perspective of sustainable development.

- Integrating environmental data into suburbanisation analyses—including global analyses of information on land cover (protected areas, forests, etc.)—should be a standard procedure in spatial development studies, as it allows for the assessment of environmental factors and the identification of natural barriers to development.

- Directional analysis as a tool for spatial planning—analysis of 16 directions allows for the identification of preferred axes of city development, which can provide significant support to local governments in planning sustainable infrastructure development and the protection of green spaces. In this case, it is worth considering expanding the analysis to include the study of current and planned communication networks (roads, railways).

- Use of hexagonal grids—the hexagonal system is particularly useful in studying land use changes, as it eliminates distortions resulting from classic administrative divisions and allows for comparable spatial analysis.

- Possibility of replicating the methods in other urban and suburban centres—the multi-variant methodology used can be used in assessments in different cities and peripheral areas experiencing suburbanisation pressures in the vicinity of valuable natural areas.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y.; Long, H.; Liu, Y. Spatio-temporal pattern of China’s rural development: A rurality index perspective. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 38, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Jiang, G.; Wang, D.; Li, W.; Guo, H.; Zheng, Q. Rural settlements transition (RST) in a suburban area of metropolis: Internal structure perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 615, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widada, R.; Barus, B.; Bambang, J.; Mulatsih, S. The Differences in Factors that Influence Poverty in Urban, Suburban, and Rural Areas. J. Econ. Financ. Manag. Stud. 2023, 6, 1793–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Wang, L. The Effect of Urban-Suburban Interaction on Urbanization and Suburban Ecological Security: A Case Study of Suburban Wuhan, Central China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, M.; Siedentop, S. Suburbanisation and Suburbanisms—Making Sense of Continental European Developments. Raumforsch. Und Raumordnung. Spat. Res. Plan. 2018, 76, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliarin, S.; de Pascal, D. Regionalised sprawl: Conceptualising suburbanisation in the European context. Urban Res. Pract. 2018, 14, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Źróbek-Rożańska, A.; Źróbek-Sokolnik, A.; Lizińska, W. Suburbanisation of the rural areas and the implementation of local authorities’ own responsibilities: Needs and challenges. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2012, 24, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmytkie, R. The impact of residential suburbanization on chages in the morphology of villages in the suburban area of Wrocław, Poland. Environ. Socio-Econ. Stud. 2020, 8, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlaváček, P.; Kopáček, M.; Horáčková, L. Impact of Suburbanisation on Sustainable Development of Settlements in Suburban Spaces: Smart and New Solutions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryczka, P.; Sikorski, D.; Figlus, T.; Lisowska-Kierepka, A.; Musiaka, Ł.; Spórna, T.; Sudra, P.; Szmytkie, R. Defining suburbanization in Central and Eastern Europe: A systematic literature review. Cities 2025, 158, 105626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, R. After Suburbia: Research and action in the suburban century. Urban Geogr. Annu. Plenary Lect. 2018, 41, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pénzes, J.; Hegedűs, L.D.; Makhanov, K.; Túri, Z. Changes in the Patterns of Population Distribution and Built-Up Areas of the Rural–Urban Fringe in Post-Socialist Context—A Central European Case Study. Land 2023, 12, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcdonald, R.I.; Kareiva, P.; Forman, R.T.T. The implications of current and future urbanization for global protected areas and biodiversity conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 1695–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieślak, I.; Biłozor, A.; Szuniewicz, K. The Use of the CORINE Land Cover (CLC) Database for Analyzing Urban Sprawl. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutuga, F. The Effect of Urbanization on Protected Areas. The Impact of Urban Growth on a Wildlife Protected Area: A Case Study of Nairobi National Park. H2—Master’s Degree (Two Years). The International Institute for Industrial Environmental Economics. Lund, Sweden, June, 2009. Available online: https://www.lunduniversity.lu.se/lup/publication/1513631 (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Wilson, B.; Chakraborty, A. The Environmental Impacts of Sprawl: Emergent Themes from the Past Decade of Planning Research. Sustainability 2013, 5, 3302–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehara-Prado, M.; Fonseca, R.L. Urbanization and Mismatch with Protected Areas Place the Conservation of a Threatened Species at Risk. Biotropica 2007, 39, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, E.F.; Hafernik, J.; Levy, J.; Lee Moore, V.; Rickman, J. Insect Conservation in an Urban Biodiversity Hotspot: The San Francisco Bay Area. J. Insect Conserv. 2002, 6, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzyna, T. Global Urbanization and Protected Areas; California Institute of Public Affairs: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2007; Available online: https://webdoc.sub.gwdg.de/ebook/mon/2008/ppn%20566501791.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2007).

- Parnell, S.; Schewenius, M.; Sendstad, M.; Seto, K.C.; Wilkinson, C. Urbanization, Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Challenges and Opportunities; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; Available online: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/978-94-007-7088-1.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Vasárus, G.L.; Lennert, J. Suburbanization within City Limits in Hungary—A Challenge for Environmental and Social Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeczko, E.; Dąbrowski, R.; Budnicka-Kosior, J.; Woźnicka, M. Influence of Urbanization Processes on the Dynamics and Scale of Spatial Transformations in the Mazowiecki Landscape Park. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmis, E.; Özden, S.; Lise, W. Urbanization pressure on the natural forests in Turkey: An overview. Urban For. Urban Green 2007, 6, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaim, D.; Grabska, E. Assessing suburban transformations with freely available spatial data. Geogr. Stud. 2025, 178, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.C. Using 3D GIS as a Decision Support Tool in Urban Planning. In Proceedings of the ICEGOV’17: 10th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance 2017, New Delhi, India, 7–9 March 2017; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegedűs, D.L.; Túri, Z.; Apáti, N.; Pénzes, J. Analysis of the intra-urban suburbanization with GIS methods the case of Debrecen since the 1980s. Folia Geogr. 2023, 65, 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wolny, A.; Dawidowicz, A.; Źróbek, R. Identification of the spatial causes of urban sprawl with the use of land information systems and GIS tools. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-Econ. Ser. Sciendo 2017, 35, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogiannidis, S.; Spinthiropoulos, K.; Kalfas, D.; Chatzitheodoridis, F.; Tziampazi, F. Integration of Remote Sensing and GIS for Urban Sprawl Monitoring in European Cities. Eur. J. Geogr. 2025, 16, 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Zahriichuk, L.; Lozynskyy, R. Spatial Analysis of Land Use Changes Based on Remote Sensing Data (on the Example of the Suburban Area of Ivano-Frankivsk). In Proceedings of the International Conference of Young Professionals GeoTerrace-2024, Lviv, Ukraine, 7–9 October 2024; European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oșlobanu, C.; Alexe, M. Built-up area analysis using Sentinel data in metropolitan areas of Transylvania, Romania. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2021, 70, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianoş, I.; Sîrodoev, I.; Pascariu, G.; Henebry, G. Divergent patterns of built-up urban space growth following post-socialist changes. Urban Stud. 2015, 53, 3172–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucsi, L.; Liska, C.M.; Henits, L.; Tobak, Z.; Csendes, B.; Nagy, L. The Evaluation and Application of an Urban Land Cover Map With Image Data Fusion and Laboratory Measurements. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2017, 66, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Pacheco, J.; Gutiérrez, J. Exploring the limitations of CORINE Land Cover for monitoring urban land-use dynamics in metropolitan areas. J. Land Use Sci. 2013, 9, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izakovičová, Z.; Petrovič, F.; Pauditšová, E. The Impacts of Urbanisation on Landscape and Environment: The Case of Slovakia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolcsár, R.A.; Csikós, N.; Szilassi, P. Testing the limitations of buffer zones and Urban atlas population data in urban green space provision analyses through the case study of Szeged, Hungary. Urban For. Urban Green 2021, 57, 126942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerekes, A.-H.; Alexe, M. Evaluating Urban Sprawl and Land-Use Change Using Remote Sensing, Gis Techniques and Historical Maps. Case Study: The City of Dej, Romania. Analele Univ. Din Oradea Ser. Geogr. 2019, 29, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Development Strategy of the City of Białystok Until 2030. Available online: https://www.bialystok.pl/pl/dla_mieszkancow/rozwoj_miasta/strategia-rozwoju-miasta-bialegostoku-do-2030-roku.html (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Statistic Poland. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Satistical Office in Białystok. Available online: https://bialystok.stat.gov.pl/ (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Public Opinion Research Center. Available online: https://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2015/K_015_15.PDF (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Landré, M. Geoprocessing Journey-to-Work Data: Delineating Commuting Regions in Dalarna, Sweden. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2012, 1, 294–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marique, A.F.; Dujardin, S.; Teller, J.; Reiter, S. Urban Sprawl, Commuting and Travel Energy Consumption. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Energy 2013, 166, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, J.; Luo, Q.; Sun, L.; Wang, E. Simulating Urban Expansion from the Perspective of Spatial Anisotropy and Expansion Neighborhood. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, Y.; Pu, L.; Jiang, B.; Yuan, S.; Xu, Y. A Novel Model for Detecting Urban Fringe and Its Expanding Patterns: An Application in Harbin City, China. Land 2021, 10, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdziej, J. Using Hexagonal Grids and Network Analysis for Spatial Accessibility Assessment in Urban Environments—A Case Study of Public Amenities in Toruń. Misc. Geogr. 2019, 23, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, C.P.D.; Oom, S.P.; Beecham, J.A. Rectangular and Hexagonal Grids Used for Observation, Experiment and Simulation in Ecology. Ecol. Model. 2007, 206, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lityński, P. The Intensity of Urban Sprawl in Poland. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włoch-Szymla, A. Urban sprawl and smart growth versus quality of life. Tech. Trans. 2019, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeczko, E.; Budnicka-Kosior, J.; Dawidziuk, A.; Woźnicka, M.; Kwaśny, Ł.; Fornal-Pieniak, B.; Chyliński, F.; Goljan, A. Impact of Forest Landscape on the Price of Development Plots in the Otwock Region, Poland. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, N.; Feng, C.-C.; Wang, D.; Li, J.; Guo, L. The Effects of Rapid Urbanization on Forest Landscape Connectivity in Zhuhai City, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Shi, P.; Wu, X.; Ma, J.; Yu, J. Effects of urbanization expansion on landscape pattern and region ecological risk in Chinese coastal city: A case study of Yantai city. Scientific. World J. 2014, 2014, 21781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antrop, M. Landscape change and the urbanization process in Europe. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 67, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y. The Relationship Between the Urban Rail Transit Network and The Population Distribution in Shanghai. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Humanities and Social Science Research (ICHSSR 2018), Wuxi, China, 25–27 April 2018; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2018. Available online: https://www.atlantis-press.com/proceedings/ichssr-18/25895821 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Mara Almeida, M.; Loupa-Ramos, I.; Menezes, H.; Carvalho-Ribeiro, S.; Guiomar, N.; Pinto-Correia, T. Urban population looking for rural landscapes: Different appreciation patterns identified in Southern Europe. Land Use Policy 2016, 53, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lityński, P.; Hołuj, A. Urban sprawl costs: The valuation of households’ losses in Poland. J. Settl. Spat. Plan. 2017, 8, 11–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Źróbek-Różańska, A.; Zadworny, D. Can urban sprawl lead to urban people governing rural areas? Evidence from the Dywity Commune, Poland. Cities 2016, 59, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, G.; Hegedus, T. Urban sprawl or/and suburbanisation?: The case of Zalaegerszeg. Belvedere Meridionale 2016, 28, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.H.; Hurd, J.D.; Civco, D.L.; Prisloe, S.; Arnold, C. Development of a Geospatial Model to Quantify, Describe and Map Urban Growth. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 86, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galster, G.; Hanson, R.; Wolman, H.; Coleman, S.; Freihage, J. Wrestling Sprawl to the Ground: Defining and measuring an elusive concept. Hous. Policy Debate 2001, 12, 681–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewska, A.; Denis, M.; Krupowicz, W. Urbanization Chaos of Suburban Small Cities in Poland: ‘Tetris Development’. Land 2020, 9, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gachowski, M.; Walusiak, Ł. Urban Phenomena in Lesser Poland Through GIS-Based Metrics: An Exceptional Form of Urban Sprawl Challenging Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podawca, K.; Karsznia, K.; Zawrzykraj, A.P. The Assessment of the Suburbanisation Degree of Warsaw Functional Area Using Changes of the Land Development Structure. Misc. Geogr. 2019, 23, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudłacz, M.; Karwińska, A. The Specificity of Urban Sprawl in Poland: The Spatial, Social, and Economic Perspectives. Zarządzanie Publiczne 2021, 55, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawid, M.; Dawid, W.; Kudłacz, K. Suburbanization in Poland and Its Consequences: A Research and Analytical Perspective on the Phenomenon. Reg. Barometer. Anal. Progn. 2023, 19, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Year | Scale/Resolution | Data Source | Update/Availability | Data Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerial orthophotomap | 1997 | 0.50 m | Head Office of Land Surveying and Cartography (GUGiK) | Historical dataset | Raster (RGB) |

| Aerial orthophotomap | 2022 | 0.25 m | GUGiK | Latest available | Raster (RGB) |

| BDOT10k (buildings) | 2022 | 1:10,000 | Topographic Objects Database (BDOT10k) | Regular updates | Vector (polygons) |

| Forest and protected areas | 2022 | 1:10,000 | GUGiK | Regular updates | Vector |

| Floodplain | 2022 | 1:10,000 | GUGiK | Regular updates | Vector |

| 25-km buffer | — | 1952 km2 | Generated in GIS | — | Vector |

| 16-sector radial system | — | 122 km2 in sector | Generated in GIS | — | Vector |

| Hexagonal grid | — | 1 km2 per hexagon | Generated in GIS | — | Vector |

| Section | 1997 (ha) | 2022 r. (ha) | Growth (ha) | Growth [%] | Normalized Growth [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 187.66 | 239.77 | 52.11 | 27.77 | 4.1 |

| 2 | 365.49 | 459.25 | 93.76 | 25.65 | 7.4 |

| 3 | 238.18 | 344.73 | 106.55 | 44.74 | 8.4 |

| 4 | 80.02 | 155.22 | 35.2 | 43.99 | 2.8 |

| 5 | 265.67 | 331.69 | 66.02 | 24.85 | 5.2 |

| 6 | 217.39 | 309.93 | 92.54 | 42.57 | 7.3 |

| 7 | 290.38 | 375.73 | 85.35 | 29.39 | 6.7 |

| 8 | 293.95 | 386.49 | 92.54 | 31.48 | 7.3 |

| 9 | 314.35 | 397.09 | 82.74 | 26.32 | 6.5 |

| 10 | 382.03 | 488.57 | 106.54 | 27.89 | 8.4 |

| 11 | 496.04 | 600.59 | 104.55 | 21.08 | 8.2 |

| 12 | 260.19 | 308.66 | 48.47 | 18.63 | 3.8 |

| 13 | 401.52 | 494.24 | 92.72 | 23.09 | 7.3 |

| 14 | 295.83 | 351.64 | 55.81 | 18.87 | 4.4 |

| 15 | 332.12 | 449.02 | 116.90 | 35.20 | 9.2 |

| 16 | 91.22 | 134.62 | 43.40 | 47.58 | 3.4 |

| Sum | 4512.04 | 5827.24 | 1275.20 | X | 100 |

| Variant | Scope of Study | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| General layout—25 km buffer | The entire city’s peripheral zone | Easy interpretation of general development trends | Low level of detail |

| Ability to indicate the overall dynamics of change | Masking spatial variations in development | ||

| Suitable for regional comparisons | Inability to analyse individual cases | ||

| Sector layout—16 radial directions | Sectors | Ability to identify asymmetries and preferred directions of development | Location of changes limited to indicating general directions |

| Appropriate correspondence with the routes of major transportation routes | Oriental values for the occurrence of local development hotspots | ||

| Hexagonal layout | Regularly shaped units (hexagons) | Very high level of detail | Greater complexity of interpretation |

| Unambiguous location of the most dynamic areas | Significant dispersion of results | ||

| The possibility of any classification of changes | Longer analysis preparation time |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Budnicka-Kosior, J.; Gąsior, J.; Janeczko, E.; Kwaśny, Ł. GIS-Based Spatial–Temporal Analysis of Development Changes in Rural and Suburban Areas. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10782. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310782

Budnicka-Kosior J, Gąsior J, Janeczko E, Kwaśny Ł. GIS-Based Spatial–Temporal Analysis of Development Changes in Rural and Suburban Areas. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10782. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310782

Chicago/Turabian StyleBudnicka-Kosior, Joanna, Jakub Gąsior, Emilia Janeczko, and Łukasz Kwaśny. 2025. "GIS-Based Spatial–Temporal Analysis of Development Changes in Rural and Suburban Areas" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10782. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310782

APA StyleBudnicka-Kosior, J., Gąsior, J., Janeczko, E., & Kwaśny, Ł. (2025). GIS-Based Spatial–Temporal Analysis of Development Changes in Rural and Suburban Areas. Sustainability, 17(23), 10782. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310782