Green Knowledge Management and Green Technology Innovation: Roles of Green Organizational Identity and Incentive Environmental Regulation

Abstract

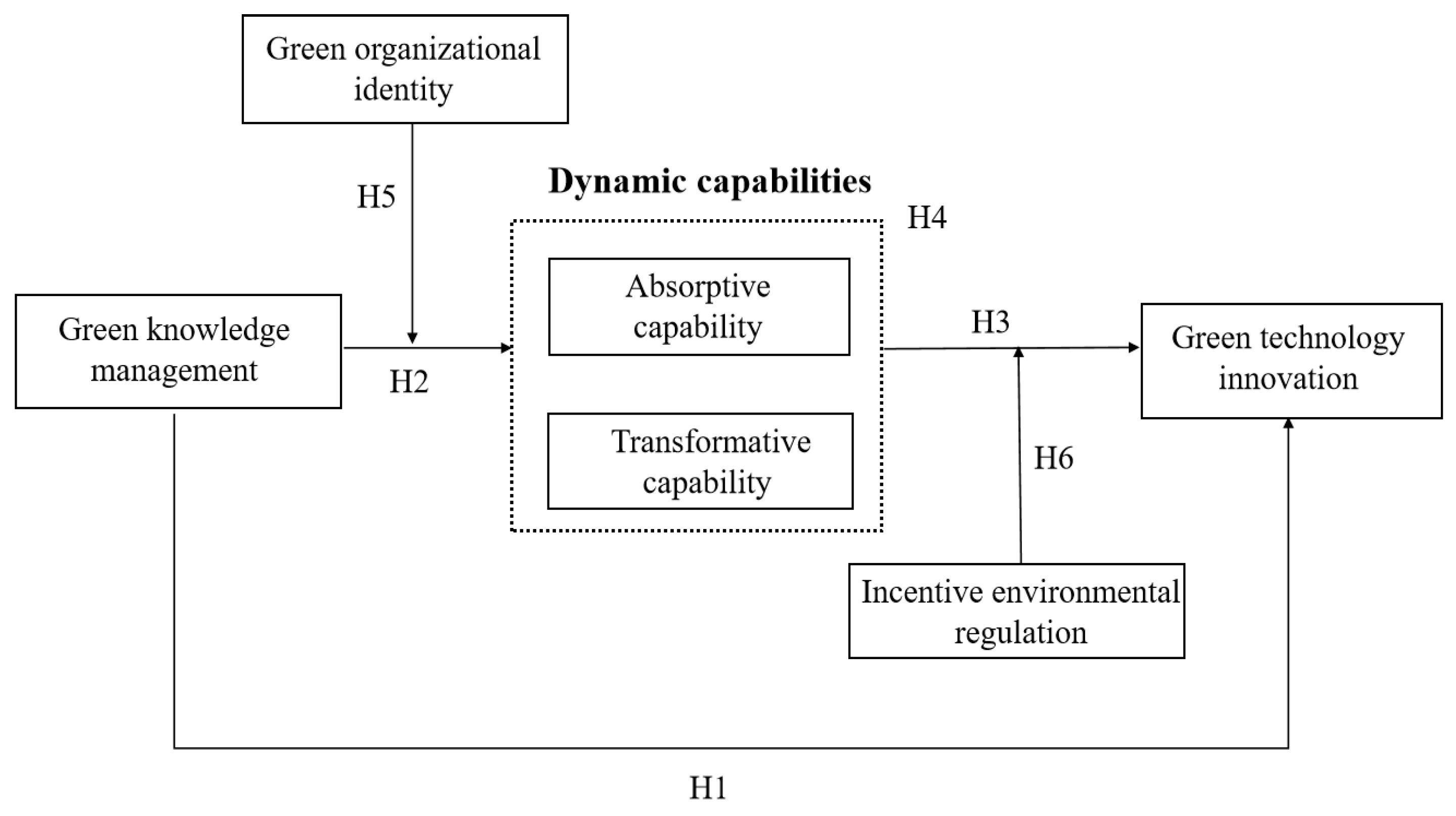

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypothesis

2.1. Dynamic Capabilities Theory

2.2. Green Knowledge Management and Green Technology Innovation

2.3. Green Knowledge Management and Dynamic Capabilities

2.4. Dynamic Capabilities and Green Technology Innovation

2.5. The Mediating Effect of Dynamic Capabilities

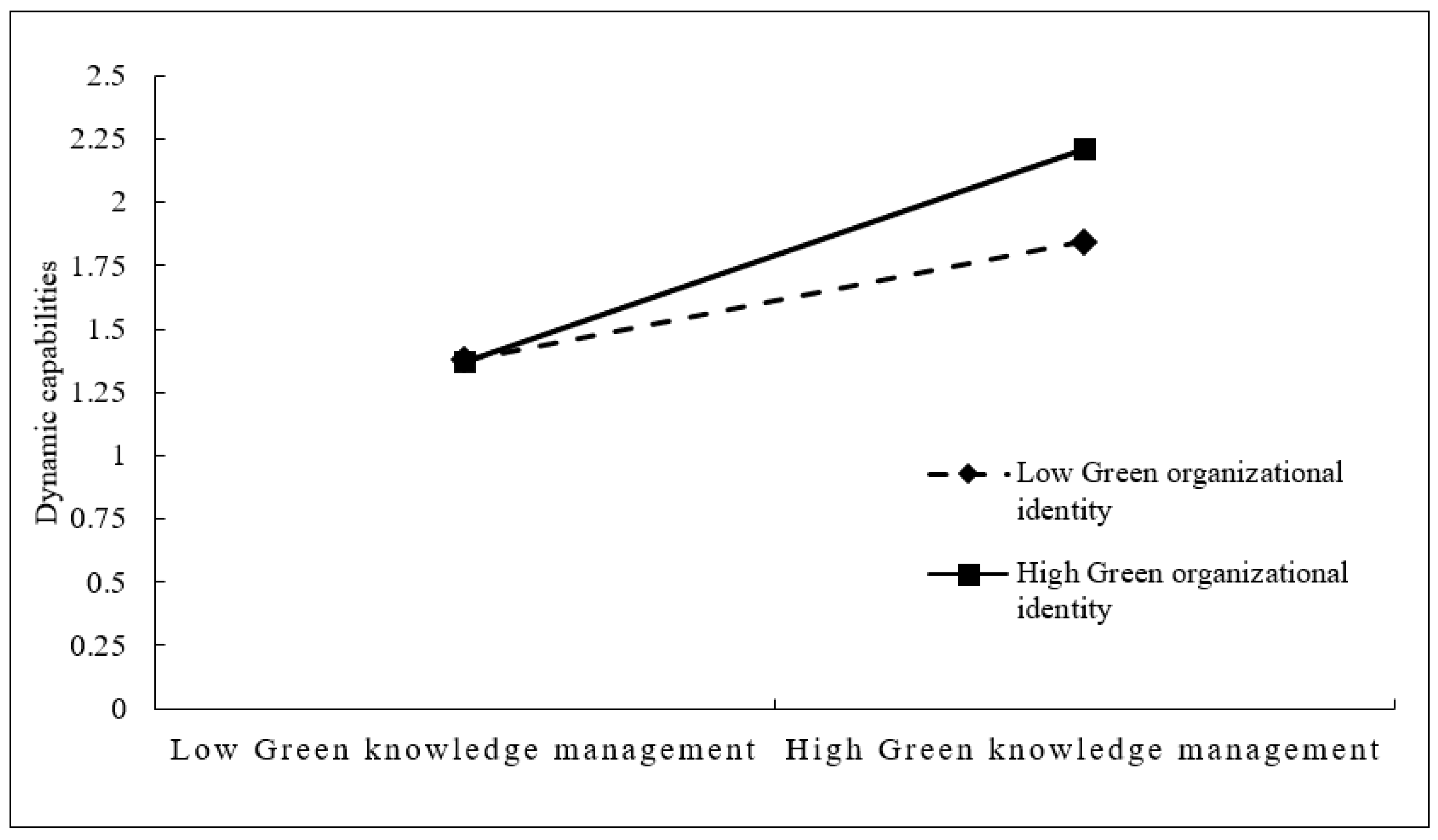

2.6. The Moderating Effect of Green Organizational Identity

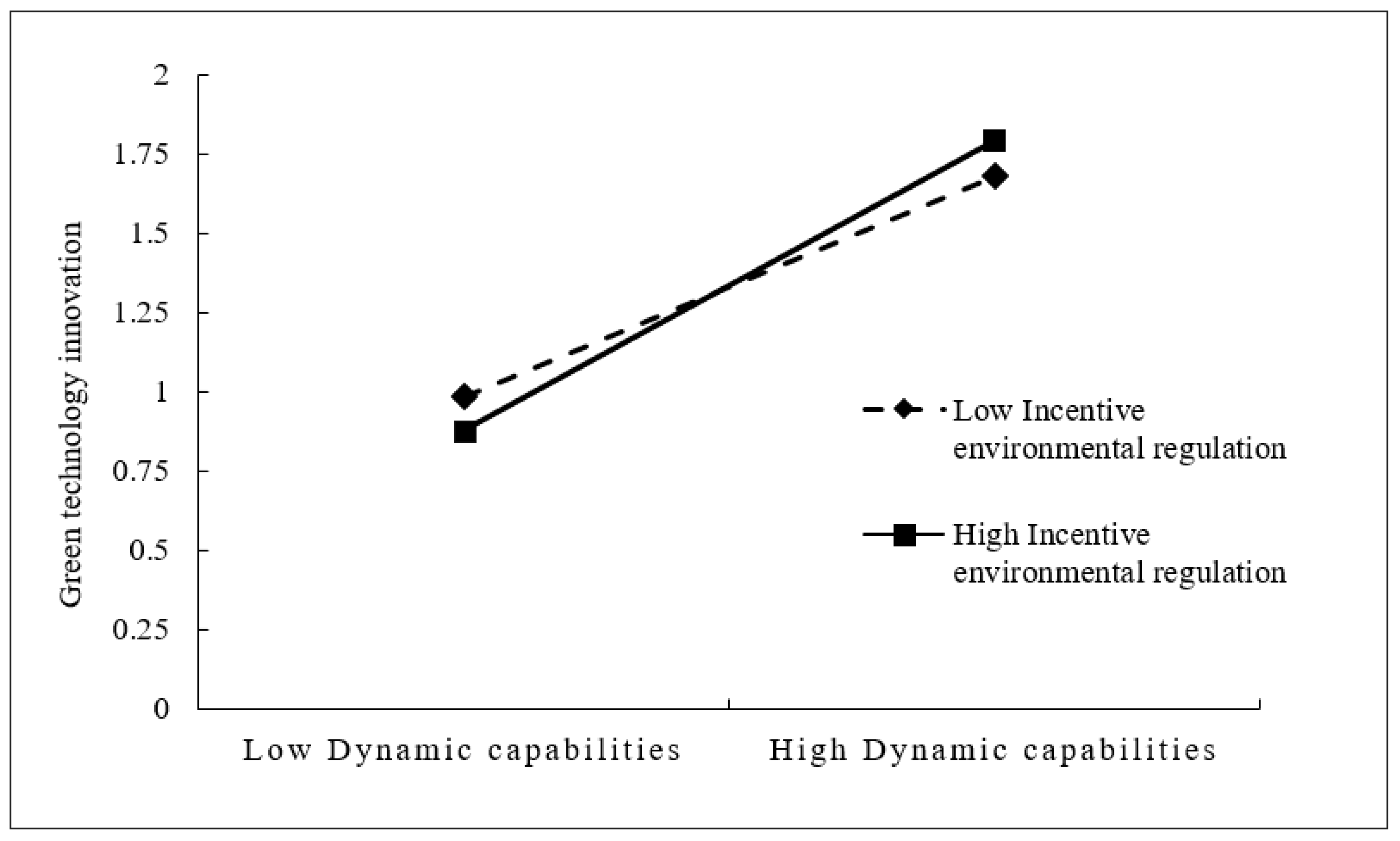

2.7. The Moderating Effect of Incentive Environmental Regulation

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measures

3.3. Common Method Bias

3.4. Reliability and Validity

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion, Implications, and Limitations

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

5.4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Constructs | Loadings |

|---|---|

| Green knowledge management (α = 0.888, CR = 0.890, AVE = 0.618) | |

| GKM-1: Employees and partners at our firm have easy access to information on best-in-class environmentally friendly practices. | 0.755 |

| GKM-2: Our firm has procedures in place to gain knowledge about the environmental practices of our competitors, suppliers, clients, and strategic partners. | 0.785 |

| GKM-3: Our firm has structured mechanisms in place to exchange best practices across multiple disciplines of business operations. | 0.823 |

| GKM-4: Our firm develops initiatives (such as seminars, periodic meetings, and collaborative projects) that promote green information exchange across divisions/stakeholders. | 0.797 |

| GKM-5: Our firm actively engages in processes that apply knowledge to solve new challenges across organizational departments and beyond departmental boundaries. | 0.768 |

| Green organizational identity (α = 0.891, CR = 0.893, AVE = 0.583) | |

| GOI-1: The firm’s top managers, middle managers, and employees have a sense of pride in the firm’s environmental goals and missions. | 0.804 |

| GOI-2: The firm’s top managers, middle managers, and employees have a strong sense of the firm’s history about environmental management and protection. | 0.738 |

| GOI-3: The firm’s top managers, middle managers, and employees feel that the firm has carved out a significant position with respect to environmental management and protection. | 0.828 |

| GOI-4: The firm’s top managers, middle managers, and employees feel that the firm have formulated a well-defined set of environmental goals and missions. | 0.838 |

| GOI-5: The firm’s top managers, middle managers, and employees are knowledgeable about the firm’s environmental traditions and cultures. | 0.688 |

| GOI-6: The firm’s top managers, middle managers, and employees identify strongly with the firm’s actions with respect to environmental management and protection. | 0.669 |

| Absorptive capability (α = 0.813, CR = 0.820, AVE = 0.604) | |

| AC-1: This firm has the necessary skills to implement newly acquired knowledge. | 0.752 |

| AC-2: This firm has the competences to transform the newly acquired knowledge. | 0.854 |

| AC-3: This firm has the competences to use the newly acquired knowledge. | 0.719 |

| Transformative capability (α = 0.895, CR = 0.895, AVE = 0.589) | |

| TC-1: People in this firm are encouraged to challenge outmoded practices. | 0.766 |

| TC-2: This firm evolves rapidly in response to shifts in our business priorities. | 0.728 |

| TC-3: This firm is creative in its methods of operation. | 0.828 |

| TC-4: This firm seeks out new ways of doing things. | 0.796 |

| TC-5: People in this firm get a lot of support from managers if they want to try new ways of doing things. | 0.825 |

| TC-6: This firm introduces improvements and innovations in our business. | 0.646 |

| Incentive environmental regulation (α = 912, CR = 0.912, AVE = 0.838) | |

| IER-1: The firm has been awarded a special fund for technological progress to support cleaner production. | 0.925 |

| IER-2: Tradable permits and pollution control subsidies have stimulated the innovation enthusiasm of the firm. | 0.906 |

| Green technology innovation (α = 877, CR = 0.878, AVE = 0.590) | |

| GTI-1: Our firm continuously optimizes the manufacturing and operational processes by using cleaner methods or green technologies to make savings. | 0.773 |

| GTI-2: Our firm is actively involved in the redesign and improvement of products or services in order to comply with existing environmental or regulatory requirements. | 0.768 |

| GTI-3: Our firm specializes in recycling practices to ensure that end-of-life products are recovered for reuse in new product manufacturing. | 0.713 |

| GTI-4: Our firm is rigorously involved in “eco-labeling” activities to make our clients conscious of our sustainable management practices. | 0.785 |

| GTI-5: The Research & Development team at our firm ensures that the current technical advancement is included in the development of new eco-products. | 0.798 |

References

- Naidoo, R.; Fisher, B. Reset Sustainable Development Goals for a pandemic world. Nature 2020, 583, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.X.; Ma, M.D.; Dong, T.Y.; Zhang, Z.Y. Do ESG ratings promote corporate green innovation? A quasi-natural experiment based on SynTao Green Finance’s ESG ratings. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 87, 102623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, E.; Wield, D. Regulation as a means for the social control of technology. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 1994, 6, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, F.S.; Sadiq, M.; Nawaz, M.A.; Hussain, M.S.; Tran, T.D.; Le Thanh, T. A step toward reducing air pollution in top Asian economies: The role of green energy, eco-innovation, and environmental taxes. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albino, V.; Dangelico, R.M.; Pontrandolfo, P. Do inter-organizational collaborations enhance a firm’s environmental performance? a study of the largest US companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 37, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.G.; Zhou, X.L. On the drivers of eco-innovation: Empirical evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 79, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Cheng, H.H.; He, J.H.; Song, Y.F.; Bu, H. The impacts of green credit policy on green innovation of high-polluting enterprises in China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 62, 105167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Xu, W.D. Green Credit Policy, Analyst Attention, and Corporate Green Innovation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Zarzoso, I.; Bengochea-Morancho, A.; Morales-Loge, R. Does environmental policy stringency foster innovation and productivity in OECD countries? Energy Policy 2019, 134, 110982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Shen, N.; Ying, H.Q.; Wang, Q.W. Can environmental regulation directly promote green innovation behavior?—Based on situation of industrial agglomeration. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 128044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfarrer, M.D.; Pollock, T.G.; Rindova, V.P. A tale of two assets: The effects of firm reputation and celebrity on earnings surprises and investors’ reactions. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 1131–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, A.; Chierici, R.; Ballestra, L.V.; Meissner, D.; Orhan, M.A. Harvesting reflective knowledge exchange for inbound open innovation in complex collaborative networks: An empirical verification in Europe. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 25, 669–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, J.; Igwe, V.; Tapang, A.; Usang, O. The innovation interface between knowledge management and firm performance. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2023, 21, 486–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, J.; Zhang, Z.P. Green knowledge management and strategic renewal: A discursive perspective on corporate sustainability. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2020, 69, 1797–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollo, M.; Winter, S.G. Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achi, A.; Adeola, O.; Achi, F.C. CSR and green process innovation as antecedents of micro, small, and medium enterprise performance: Moderating role of perceived environmental volatility. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, Z. Go for green: Green innovation through green dynamic capabilities: Accessing the mediating role of green practices and green value co-creation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 54863–54875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, U.; Lichtenthaler, E. A Capability-Based Framework for Open Innovation: Complementing Absorptive Capacity. J. Manag. Stud. 2009, 46, 1315–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Senaratne, C.; Rafiq, M. Success Traps, Dynamic Capabilities and Firm Performance. Br. J. Manag. 2015, 26, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.C.; Barbieux, D.; Reichert, F.M.; Tello-Gamarra, J.; Zawislak, P.A. Innovation and dynamic capabilities of the firm: Defining an assessment model. Rae-Rev. Adm. Empresas 2017, 57, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M.; Ince, H.; Imamoglu, S.Z. Effects of Standardized Innovation Management Systems on Innovation Ambidexterity and Innovation Performance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoemaker, P.J.H.; Heaton, S.; Teece, D. Innovation, Dynamic Capabilities, and Leadership. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2018, 61, 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albort-Morant, G.; Leal-Millán, A.; Cepeda-Carrión, G.; Henseler, J. Developing green innovation performance by fostering of organizational knowledge and coopetitive relations. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2018, 12, 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soewarno, N.; Tjahjadi, B.; Fithrianti, F. Green innovation strategy and green innovation: The roles of green organizational identity and environmental organizational legitimacy. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 3061–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Y.; Wang, X.C.; Shen, W.; Tan, Y.Y.; Matac, L.M.; Samad, S. Environmental Uncertainty, Environmental Regulation and Enterprises’ Green Technological Innovation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. The foundations of Enterprise performance: Dynamic and ordinary capabilities in an (economic) theory of firms. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 28, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Ahmed, P.K. Dynamic capabilities: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2007, 9, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; George, G. Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandza, K.; Holt, R. Absorptive and transformative capacities in nanotechnology innovation systems. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2007, 24, 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman Kabadurmus, F.N. Antecedents to supply chain innovation. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2020, 31, 145–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, Y.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Wah, W.X. Pursuing green growth in technology firms through the connections between environmental innovation and sustainable business performance: Does service capability matter? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.W.; Li, Y.H. Green Innovation and Performance: The View of Organizational Capability and Social Reciprocity. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Dong, C.H. Quantity or quality? The impacts of environmental regulation and government R&D funding on green technology innovation: Evidence from China. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2025, 32, 697–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Del Giudice, M.; Chierici, R.; Graziano, D. Green innovation and environmental performance: The role of green transformational leadership and green human resource management. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 150, 119762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Kumar, A.; Upadhyay, A. How do green knowledge management and green technology innovation impact corporate environmental performance? Understanding the role of green knowledge acquisition. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabdellah, A.C.; Zekhnini, K.; Cherrafi, A.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Kumar, A. Design for the environment: An ontology-based knowledge management model for green product development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 4037–4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cegarra-Navarro, J.G.; Kassaneh, T.C.; Caro, E.M.; Martínez, A.M.; Bolisani, E. Technology Assimilation and Embarrassment in SMEs: The Mediating Effect on the Relationship of Green Skills and Organizational Reputation. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 70, 4278–4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.T.; Xin, L. Research on green innovation countermeasures of supporting the circular economy to green finance under big data. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2022, 35, 1305–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Sagsan, M. Impact of knowledge management practices on green innovation and corporate sustainable development: A structural analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Govindan, K.; Xie, X.B. How fairness perceptions, embeddedness, and knowledge sharing drive green innovation in sustainable supply chains: An equity theory and network perspective to achieve sustainable development goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 120950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubit, R. Tacit knowledge and knowledge management: The keys to sustainable competitive advantage. Organ. Dyn. 2001, 29, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, F.; Park, W.Y.; Chan, F.T.S. Innovation shock, outsourcing strategy, and environmental performance: The roles of prior green innovation experience and knowledge inheritance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1572–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, A.; Ravasan, A.Z.; Trkman, P.; Afshari, S. The role of business analytics capabilities in bolstering firms’ agility and performance. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 47, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.H.; Wang, H. Big data for small and medium-sized enterprises (SME): A knowledge management model. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 881–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Qu, Y.; Zafar, A.U.; Rehman, S.U.; Islam, T. Exploring the influence of knowledge management process on corporate sustainable performance through green innovation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 2079–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, J.L.; Deng, Z.H. Information technology resource, knowledge management capability, and competitive advantage: The moderating role of resource commitment. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 1062–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusliza, M.Y.; Yong, J.Y.; Tanveer, M.I.; Ramayah, T.; Faezah, J.N.; Muhammad, Z. A structural model of the impact of green intellectual capital on sustainable performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 249, 119334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Xue, D.D.; He, X. A balancing strategy for ambidextrous learning, dynamic capabilities, and business model design, the opposite moderating effects of environmental dynamism. Technovation 2021, 103, 102225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baert, C.; Meuleman, M.; Debruyne, M.; Wright, M. Portfolio entrepreneurship and resource orchestration. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2016, 10, 346–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, X.E.; Teng, X.Y. How to convert green entrepreneurial orientation into green innovation: The role of knowledge creation process and green absorptive capacity. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 1260–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhloufi, L.; Djermani, F.; Meirun, T. Mediation-moderation model of green absorptive capacity and green entrepreneurship orientation for corporate environmental performance. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2024, 35, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Kim, Y.; Roh, T. Exploring the role of digital servitization for green innovation: Absorptive capacity, transformative capacity, and environmental strategy. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 207, 123614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, G.; Dhar, R.L. Green training in enhancing green creativity via green dynamic capabilities in the Indian handicraft sector: The moderating effect of resource commitment. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 121948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K.S.R.; Wäger, M. Building dynamic capabilities for digital transformation: An ongoing process of strategic renewal. Long Range Plan. 2019, 52, 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.N.; Tao, S.; Hanan, A.; Ong, T.S.; Latif, B.; Ali, M. Fostering Green Innovation Adoption through Green Dynamic Capability: The Moderating Role of Environmental Dynamism and Big Data Analytic Capability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, G.; Testa, F.; Boiral, O.; Iraldo, F. Organizational Learning for Environmental Sustainability: Internalizing Lifecycle Management. Organ. Environ. 2022, 35, 103–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannas, R. Exploring digital transformation and dynamic capabilities in agrifood SMEs. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2023, 61, 1611–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coreynen, W.; Matthyssens, P.; Vanderstraeten, J.; van Witteloostuijn, A. Unravelling the internal and external drivers of digital servitization: A dynamic capabilities and contingency perspective on firm strategy. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 89, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favoretto, C.; Mendes, G.H.S.; Oliveira, M.G.; Cauchick-Miguel, P.A.; Coreynen, W. From servitization to digital servitization: How digitalization transforms companies’ transition towards services. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 102, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.F.; Jing-Qin, S.A.; Higgins, A. How dynamic capabilities affect adoption of management innovations. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 862–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.; Bossink, B.; van Vliet, M. Microfoundations of companies’ dynamic capabilities for environmentally sustainable innovation: Case study insights from high-tech innovation in science-based companies. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 366–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, S.; Whetten, D.A. Organizational identity. In Research in Organizational Behavior; JAI Press: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Mesmer-Magnus, J.R.; Asencio, R.; Seely, P.W.; DeChurch, L.A. How Organizational Identity Affects Team Functioning: The Identity Instrumentality Hypothesis. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 1530–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, Z.G.; Cable, D.M.; Voss, G.B. Organizational identity and firm performance: What happens when leaders disagree about “who we are?”. Organ. Sci. 2006, 17, 741–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.P.; Wang, J.H.; Tou, L.L. The Relationship between Green Organization Identity and Corporate Environmental Performance: The Mediating Role of Sustainability Exploration and Exploitation Innovation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Pablo, A.L.; Vredenburg, H. Corporate environmental responsiveness strategies: The importance of issue interpretation and organizational context. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1999, 35, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S. Green organizational identity: Sources and consequence. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 384–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Chen, Y.S. Green organizational identity and green innovation. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 1056–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.H.; Ren, S.C.; Yu, J. Bridging the gap between corporate social responsibility and new green product success: The role of green organizational identity. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.H.; Yu, H.Y. Green Innovation Strategy and Green Innovation: The Roles of Green Creativity and Green Organizational Identity. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.W.; Chen, F.F.; Luan, H.D.; Chen, Y.S. Effect of Green Organizational Identity, Green Shared Vision, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment on Green Product Development Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaomin, Z.; Na, W.; Jia, W.; Qiang, F.; Zeqiang, F. Review on the connotation, characterization and application of environmental regulation. J. Environ. Eng. Technol. 2021, 11, 1250–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.L.; Yin, H.T.; Zhao, Y. Impact of environmental regulations on the efficiency and CO2 emissions of power plants in China. Appl. Energy 2015, 149, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.G.; Li, X.L.; Yuan, B.L.; Li, D.Y.; Chen, X.H. The effects of three types of environmental regulation on eco-efficiency: A cross-region analysis in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 173, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.N.; Zou, H.Y.; Coffman, D.; Mi, Z.F.; Du, H.B. The synergistic impact of incentive and regulatory environmental policies on firms’ environmental performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zeng, S.; Ma, H.; Chen, H. How political connections affect corporate environmental performance: The mediating role of green subsidies. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 2015, 21, 2192–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cainelli, G.; D’Amato, A.; Mazzanti, M. Resource efficient eco-innovations for a circular economy: Evidence from EU firms. Res. Policy 2020, 49, 103827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.S.; Coelho, A.; Cancela, B.L. The relationship between green supply chain and green innovation based on the push of green strategic alliances. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 1026–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhu, L. Enhancing corporate sustainable development: Stakeholder pressures, organizational learning, and green innovation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1012–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.H.; Geng, Y.; Lai, K.H. Circular economy practices among Chinese manufacturers varying in environmental-oriented supply chain cooperation and the performance implications. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 1324–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.C.; Farooq, U.; Alam, M.M.; Dai, J.P. How does environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance determine investment mix? New empirical evidence from BRICS. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2024, 24, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.W.; Zou, P.; Ma, Y. The Effect of Air Pollution on Food Preferences. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 410–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguir, I.; Stekelorum, R.; El Baz, J. Proactive environmental strategy and performances of third party logistics providers (TPLs): Investigating the role of eco-control systems. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 240, 108249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, M.; Weissenberger, B.E. Towards a holistic view of CSR-related management control systems in German companies: Determinants and corporate performance effects. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 294, 126084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A., Jr. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, E.S.; Kim, K.H.; Erlen, J.A. Translation of scales in cross-cultural research: Issues and techniques. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 58, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Acosta, P.; Popa, S.; Martinez-Conesa, I. Information technology, knowledge management and environmental dynamism as drivers of innovation ambidexterity: A study in SMEs. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 824–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A.; Thomas, J.B. Identity, image, and issue interpretation: Sensemaking during strategic change in academia. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 370–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappin, M.M.H.; Vermeulen, W.J.V.; Meeus, M.T.H.; Hekkert, M.P. Enhancing our understanding of the role of environmental policy in environmental innovation: Adoption explained by the accumulation of policy instruments and agent-based factors. Environ. Sci. Policy 2009, 12, 934–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zameer, H.; Yasmeen, H.; Wang, Y.; Saeed, M.R. Sustainability-oriented corporate strategy: Green image and innovation capabilities. Manag. Decis. 2024, 62, 1750–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; El-Kassar, A.N. Role of big data analytics in developing sustainable capabilities. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 1264–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epicoco, M. Patterns of innovation and organizational demography in emerging sustainable fields: An analysis of the chemical sector. Res. Policy 2016, 45, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Jie, X.W.; Wang, Y.N.; Zhao, M.J. Green product innovation, green dynamic capability, and competitive advantage: Evidence from Chinese manufacturing enterprises. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 146–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.R.; Xue, Y.J.; Yang, J. Boundary-spanning search and firms’ green innovation: The moderating role of resource orchestration capability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, T.; Feng, T.W.; Huo, B.F. Green supply chain integration and financial performance: A social contagion and information sharing perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 2255–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, B.B.; Huo, B.F.; Zhao, X.D. The impact of supply chain integration on performance: A contingency and configuration approach. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Xia, W.L.; Feng, T.W.; Jiang, J.J.; He, Q.S. How environmental orientation influences firm performance: The missing link of green supply chain integration. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, P.Y. Reexamining a model for evaluating information center success using a structural equation modeling approach. Decis. Sci. 1997, 28, 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, E.F.; Hollenbeck, J.R. Clarifying some controversial issues surrounding statistical procedures for detecting moderator variables: Empirical evidence and related matters. J. Appl. Psychol. 1989, 74, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Li, Z.H.; Drakeford, B. Do the Green Credit Guidelines Affect Corporate Green Technology Innovation? Empirical Research from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.M.; Yu, Y.; Du, K.R.; Zhang, N. How does environmental regulation promote green technology innovation? Evidence from China’s total emission control policy. Ecol. Econ. 2024, 219, 108137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhengiz, T.; Niesten, E. Competences for Environmental Sustainability: A Systematic Review on the Impact of Absorptive Capacity and Capabilities. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 162, 881–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Qu, Y.; Rehman, S.U.; Zafar, A.U.; Ding, X.A.; Abbas, J. Impact of knowledge absorptive capacity on corporate sustainability with mediating role of CSR: Analysis from the Asian context. J. Plan. Lit. 2022, 37, 175–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. The Determinants of Green Product Development Performance: Green Dynamic Capabilities, Green Transformational Leadership, and Green Creativity. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.X.; Jiao, J.L.; Tang, Y.S.; Xu, Y.W.; Zha, J.R. How global value chain participation affects green technology innovation processes: A moderated mediation model. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.J.; Luo, W.Y.; Guo, F.F.; Wang, P. How Digital Orientation Affects Innovation Performance? Exploring the Role of Digital Capabilities and Environmental Dynamism. Systems 2025, 13, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Cai, J.; Xiong, R.; Zheng, L.; Ma, D. Singular pooling: A spectral pooling paradigm for second-trimester prenatal level II ultrasound standard fetal plane identification. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025. early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Frequency | % of Samples |

|---|---|---|

| Job title | ||

| Grass-roots managers | 96 | 26.80 |

| Middle managers | 150 | 41.90 |

| Senior managers | 112 | 31.30 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 176 | 49.20 |

| Male | 182 | 50.80 |

| Characteristics | Frequency | % of Samples |

|---|---|---|

| Firm age | ||

| Less than 5 years | 36 | 10.10 |

| 6–10 Years | 69 | 19.20 |

| 11–15 Years | 111 | 31.00 |

| More than 16 years | 142 | 39.70 |

| Firm size | ||

| Fewer than 50 employees | 25 | 7.00 |

| 51–300 Employees | 101 | 28.20 |

| 301–1000 Employees | 98 | 27.40 |

| More than 1000 employees | 134 | 37.40 |

| Type of ownership | ||

| State-owned | 115 | 32.10 |

| Private | 176 | 49.20 |

| Foreign-owned | 50 | 14.00 |

| others | 17 | 4.70 |

| Industry | ||

| Manufacturing | 166 | 46.40 |

| Construction | 57 | 15.90 |

| Information transmission, software and information technology services | 64 | 17.90 |

| Wholesale and retail | 20 | 5.60 |

| Financial | 27 | 7.50 |

| Other industries | 24 | 6.70 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Job title | − | |||||||||||

| 2. Gender | 0.006 | − | ||||||||||

| 3. Firm age | −0.059 | 0.031 | − | |||||||||

| 4. Firm size | −0.043 | −0.008 | −0.011 | − | ||||||||

| 5. Type of ownership | −0.058 | 0.019 | −0.003 | −0.031 | − | |||||||

| 6. Industry | −0.105 * | −0.037 | 0.088 | 0.076 | −0.004 | − | ||||||

| 7. GKM | 0.057 | 0.037 | 0.007 | −0.011 | −0.013 | 0.003 | 0.786 | |||||

| 8. AC | 0.070 | −0.001 | 0.079 | 0.031 | 0.013 | 0.074 | 0.191 ** | 0.777 | ||||

| 9. TC | 0.010 | 0.076 | 0.078 | −0.022 | −0.016 | 0.035 | 0.247 ** | 0.510 ** | 0.767 | |||

| 10. GOI | −0.048 | 0.029 | −0.026 | 0.004 | 0.061 | 0.009 | 0.013 | 0.103 * | 0.228 ** | 0.764 | ||

| 11. IER | 0.068 | 0.014 | −0.052 | 0.086 | −0.106 * | 0.110 * | 0.129 * | 0.156 ** | 0.107 * | 0.211 ** | 0.915 | |

| 12. GTI | 0.153 ** | 0.032 | −0.055 | −0.043 | 0.014 | 0.042 | 0.423 ** | 0.291 ** | 0.297 ** | 0.047 | 0.093 | 0.768 |

| Mean | 2.040 | 1.510 | 3.000 | 2.950 | 1.910 | 2.320 | 3.716 | 3.492 | 3.428 | 3.452 | 3.366 | 3.630 |

| SD | 0.762 | 0.501 | 0.997 | 0.968 | 0.803 | 1.588 | 0.868 | 0.930 | 0.915 | 0.950 | 1.136 | 0.864 |

| GKM | AC | TC | GOI | IER | GTI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GKM | 1 | |||||

| AC | 0.218 | 1 | ||||

| TC | 0.277 | 0.590 | 1 | |||

| GOI | 0.013 | 0.121 | 0.252 | 1 | ||

| IER | 0.142 | 0.182 | 0.116 | 0.234 | 1 | |

| GTI | 0.477 | 0.343 | 0.331 | 0.053 | 0.103 | 1 |

| GTI | DC | AC | TC | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 |

| Control variable | ||||||||||

| Job level | 0.177 ** | 0.150 ** | 0.160 ** | 0.156 ** | 0.142 ** | 0.137 * | 0.047 | 0.031 | 0.091 | 0.002 |

| Gender | 0.059 | 0.032 | 0.027 | 0.032 | 0.013 | 0.019 | 0.091 | 0.076 | −0.015 | 0.121 |

| Firm age | −0.046 | −0.049 | −0.070 | −0.071 | −0.066 | −0.067 | 0.069 | 0.067 | 0.071 | 0.065 |

| Firm size | −0.036 | −0.033 | −0.035 | −0.037 | −0.032 | −0.035 | −0.005 | −0.003 | 0.031 | −0.020 |

| Type of ownership | 0.023 | 0.028 | 0.025 | 0.023 | 0.028 | 0.026 | −0.005 | −0.003 | 0.025 | −0.016 |

| Industry | 0.036 | 0.034 | 0.027 | 0.025 | 0.027 | 0.026 | 0.028 | 0.026 | 0.042 | 0.019 |

| Independent | ||||||||||

| GKM | 0.413 *** | 0.352 *** | 0.353 *** | 0.238 *** | 0.201 *** | 0.257 *** | ||||

| Mediator | ||||||||||

| DC | 0.354 *** | 0.257 *** | ||||||||

| AC | 0.167 ** | 0.139 ** | ||||||||

| TC | 0.195 *** | 0.128 * | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.033 | 0.204 | 0.142 | 0.144 | 0.258 | 0.261 | 0.015 | 0.079 | 0.054 | 0.073 |

| ΔR2 | 0.016 | 0.188 | 0.125 | 0.124 | 0.241 | 0.241 | 0.001 | 0.061 | 0.035 | 0.054 |

| F | 1.972 | 12.809 *** | 8.254 *** | 7.339 *** | 15.161 *** | 13.626 *** | 0.904 | 4.311 *** | 2.835 ** | 3.909 *** |

| Dependent Variable: GTI (Bootstrap 95%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable | Effect Type | Value | Boot SE | LLCI | ULCI | Rate (%) |

| GKM | Total effect | 0.413 | 0.048 | 0.320 | 0.507 | 100 |

| Direct effect | 0.352 | 0.048 | 0.258 | 0.446 | 85.23 | |

| Indirect effect | 0.061 | 0.018 | 0.029 | 0.101 | 14.77 | |

| DC | GTI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

| Control variable | ||||

| Job level | 0.042 | 0.052 | 0.142 ** | 0.130 * |

| Gender | 0.066 | 0.061 | 0.013 | 0.023 |

| Firm age | 0.073 | 0.074 | −0.066 | −0.070 |

| Firm size | −0.003 | −0.031 | −0.032 | −0.035 |

| Type of ownership | −0.015 | −0.013 | 0.029 | 0.029 |

| Industry | 0.026 | 0.019 | 0.027 | 0.027 |

| Independent | ||||

| GKM | 0.235 *** | 0.234 *** | 0.352 *** | 0.347 *** |

| Mediator | ||||

| DC | 0.257 *** | 0.256 *** | ||

| Moderator | ||||

| GOI | 0.180 *** | 0.179 *** | ||

| IER | 0.001 | 0.003 | ||

| Interaction term | ||||

| GKM × GOI | 0.185 *** | |||

| DC × IER | 0.109 * | |||

| R2 | 0.123 | 0.160 | 0.258 | 0.269 |

| ΔR2 | 0.103 | 0.138 | 0.239 | 0.248 |

| F | 6.141 *** | 7.366 *** | 13.438 *** | 12.763 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Hou, M.; Luo, W. Green Knowledge Management and Green Technology Innovation: Roles of Green Organizational Identity and Incentive Environmental Regulation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10781. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310781

Wang Z, Hou M, Luo W. Green Knowledge Management and Green Technology Innovation: Roles of Green Organizational Identity and Incentive Environmental Regulation. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10781. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310781

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zongjun, Mengmeng Hou, and Wenyi Luo. 2025. "Green Knowledge Management and Green Technology Innovation: Roles of Green Organizational Identity and Incentive Environmental Regulation" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10781. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310781

APA StyleWang, Z., Hou, M., & Luo, W. (2025). Green Knowledge Management and Green Technology Innovation: Roles of Green Organizational Identity and Incentive Environmental Regulation. Sustainability, 17(23), 10781. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310781