Binary and Ternary Blends of Construction and Demolition Waste and Marble Powder as Supplementary Cementitious Materials

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Construction and Demolition Waste as a Supplementary Cementitious Material

1.2. Marble Powder as a Supplementary Cementitious Material

2. Research Significance and Objectives

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Wastes Laboratory Treatment

3.1.1. Waste Marble

3.1.2. Construction and Demolition Wastes

3.2. Tests on Pastes and Mortars

3.2.1. Setting Time and Soundness of Pastes

3.2.2. Mortar Specimens Manufacturing

3.2.3. Workability

3.2.4. Mechanical Strength

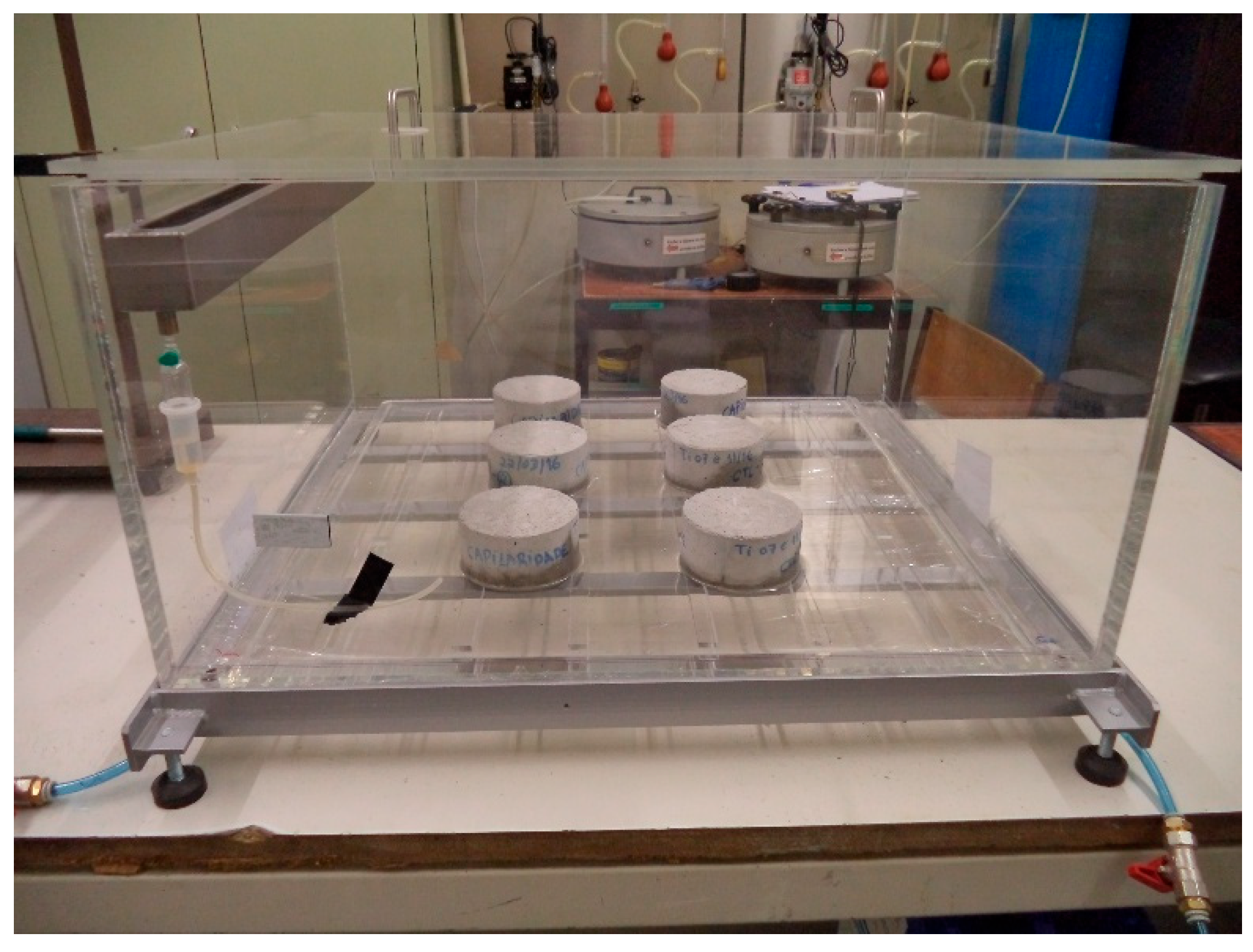

3.2.5. Durability Indicators

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Raw Materials Properties

4.2. Paste Level

4.3. Mortar Level

4.3.1. Fresh State

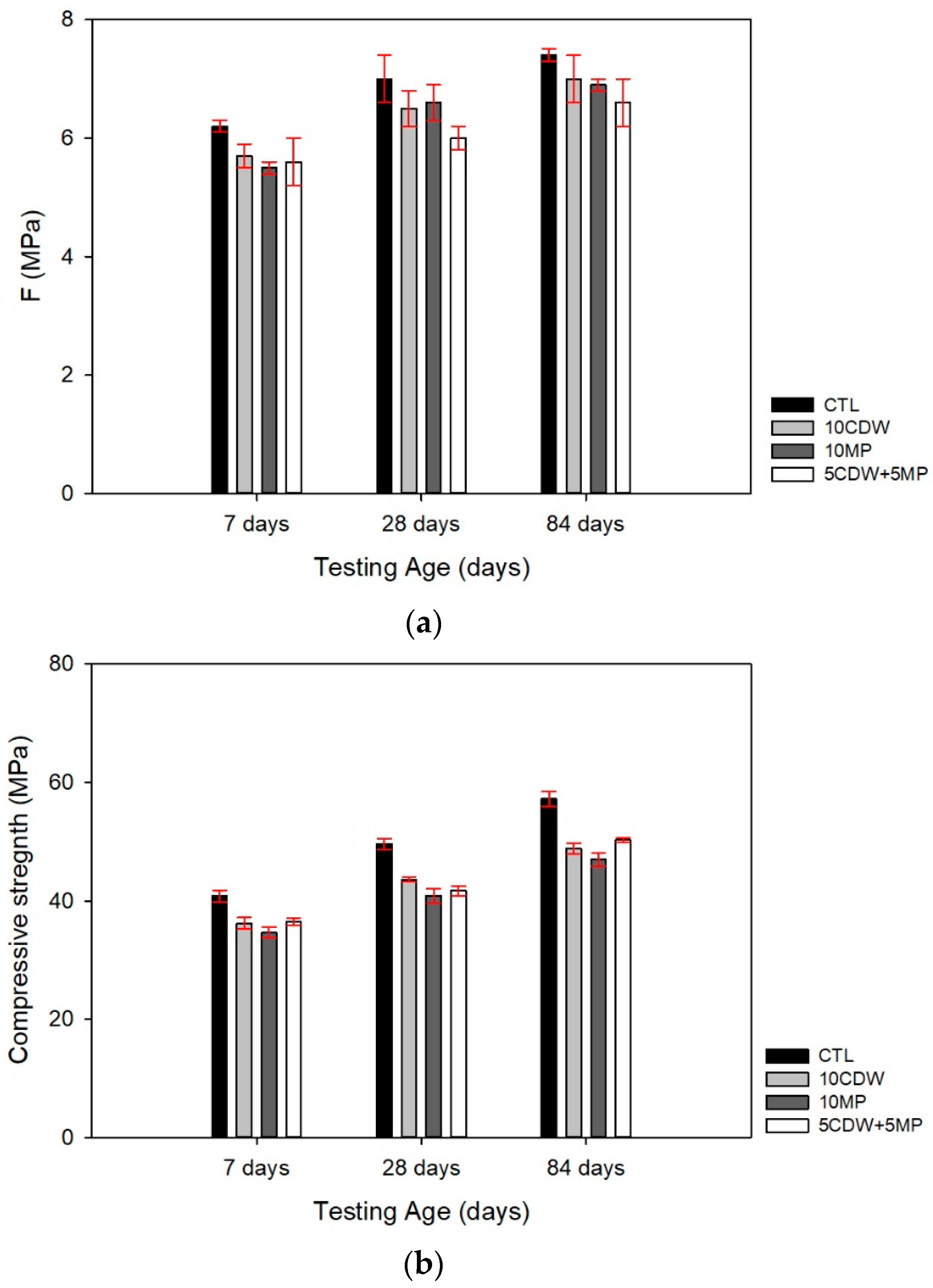

4.3.2. Mechanical Properties

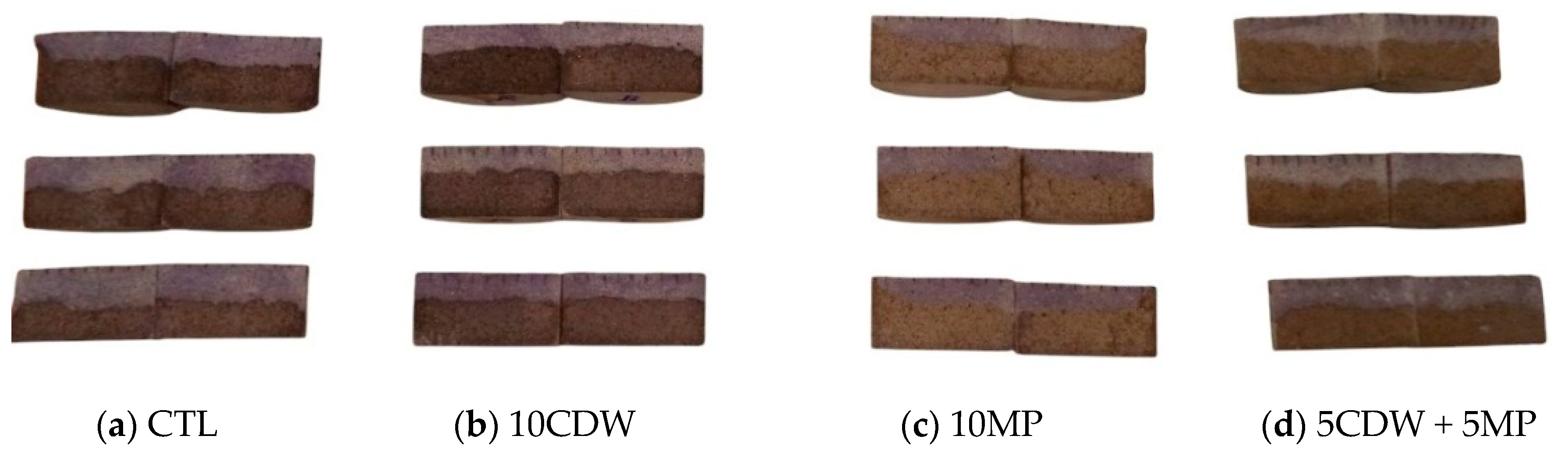

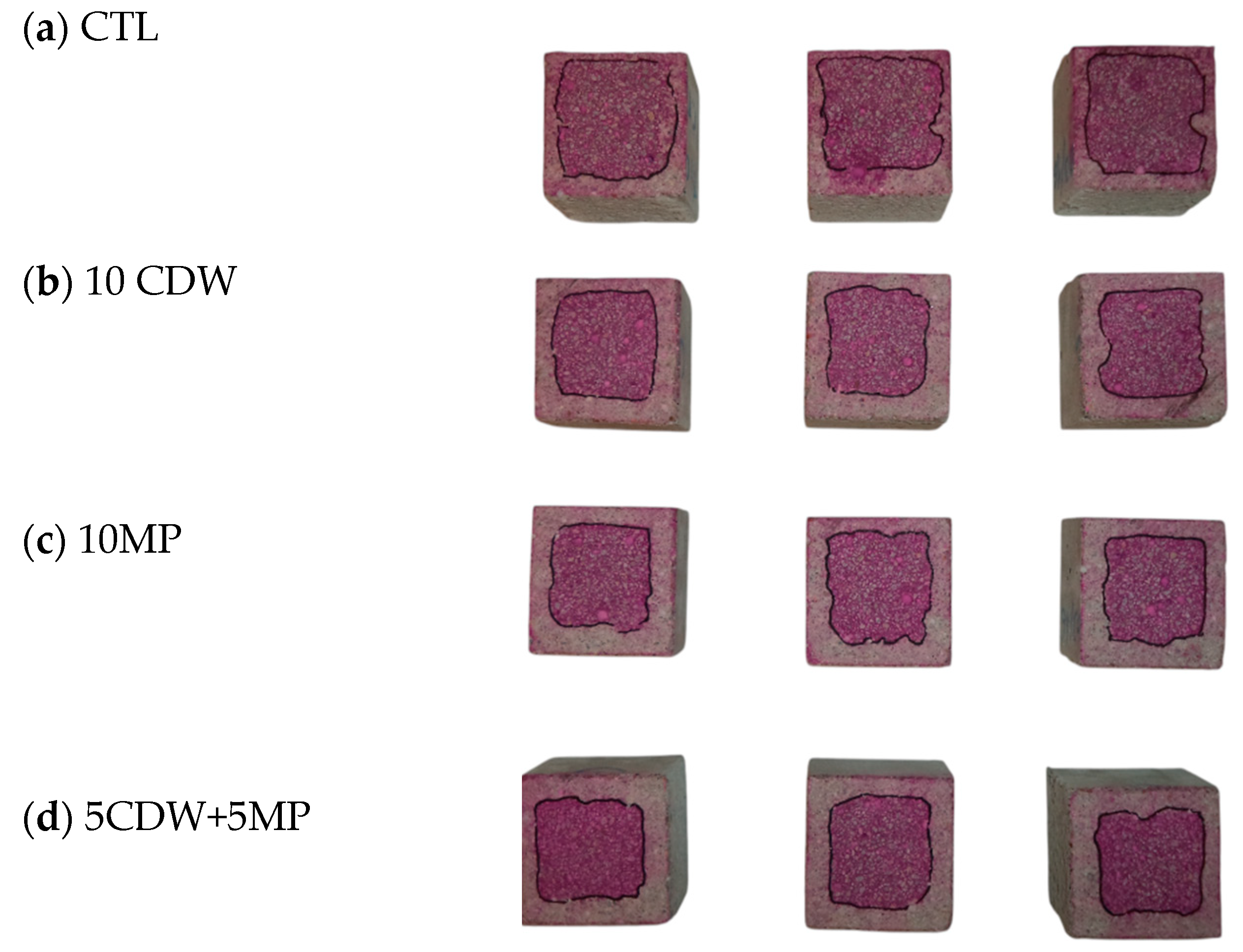

4.3.3. Durability Indicators

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDW | Construction and Demolition waste |

| h | hours |

| HR | Relative Humidity (%) |

| LF | Limestone filler |

| LOI | Loss on ignition (%) |

| MP | Waste marble powder |

| PC | Portland cement |

| SAI | Strength activity index (%) |

| SCMs | Supplementary cementitious materials |

| w/c | water to cement weight ratio |

| w/b | water to binder weight ratio |

References

- Ige, O.E.; Von Kallon, D.V.; Desai, D. Carbon emissions mitigation methods for cement industry using a systems dynamics model. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2024, 26, 579–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, S.V.; Irassar, E.F.; Rahhal, V.F. Recycled Construction and Demolition Waste as Supplementary Cementing Materials in Eco-Friendly Concrete. Recycling 2023, 8, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favier, A.; Scrivener, K.; Habert, G. Decarbonizing the cement and concrete sector: Integration of the full value chain to reach net zero emissions in Europe. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 225, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripley, K.M.; Saadi, F.H.; Burke, Z.L.H. Cost-motivated pathways towards near-term decarbonization of the cement industry. RSC Sustain. 2024, 3, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Deep Decarbonisation of Industry: The Cement Sector Cement Sector Overview; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Khaiyum, M.Z.; Sarker, S.; Kabir, G. Evaluation of Carbon Emission Factors in the Cement Industry: An Emerging Economy, Context. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waste and Supplementary Cementitious Materials in Concrete. ScienceDirect. Rafat Siddique. 2018. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/9780081021569/waste-and-supplementary-cementitious-materials-in-concrete (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Miller, S.A.; Habert, G.; Myers, R.J.; Harvey, J.T. Achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions in the cement industry via value chain mitigation strategies. One Earth 2021, 4, 1398–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, W.; Alexander, M.; John, V. Education for sustainable use of cement-based materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 114, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, D.; Lodato, C.; Damgaard, A.; Cristóbal, J.; Foster, G.; Flachenecker, F.; Tonini, D. Environmental and socio-economic effects of construction and demolition waste recycling in the European Union. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, H.S.; Pachiappan, T.; Avudaiappan, S.; Maureira-Carsalade, N.; Roco-Videla, Á.; Guindos, P.; Parra, P.F. A Comprehensive Review on Recycling of Construction Demolition Waste in Concrete. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Construction and Demolition Waste. European Commission. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/waste-and-recycling/construction-and-demolition-waste_en (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- de Andrade Salgado, F.; de Andrade Silva, F. Recycled aggregates from construction and demolition waste towards an application on structural concrete: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 52, 104452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, G.S.D.; Quattrone, M.; Ambrós, W.M.; Cazacliu, B.G.; Hoffmann Sampaio, C. Current Applications of Recycled Aggregates from Construction and Demolition: A Review. Materials 2021, 14, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soultana, A.; Galetakis, M.; Vasiliou, A.; Komnitsas, K.; Vamvuka, D. Utilization of Upgraded Recycled Concrete Aggregates and Recycled Concrete Fines in Cement Mortars. Recent Prog. Mater. 2021, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Y.F.; Lange, D.A.; Delvasto, S. Effects of the incorporation of residue of masonry on the properties of cementitious mortars. Rev. Construcción 2020, 19, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantero, B.; del Bosque, I.F.S.; de Rojas, M.I.S.; Matías, A.; Medina, C. Durability of concretes bearing construction and demolition waste as cement and coarse aggregate substitutes. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 134, 104722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, M.; Skocek, J.; Gołek, Ł.; Deja, J. Supplementary cementitious materials based on recycled concrete paste. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 387, 135743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, T.F.; Possan, E.; de Oliveira Andrade, J.J. Physical-chemical characterization of construction and demolition waste powder with thermomechanical activation for use as supplementary cementitious material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 437, 136907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.M.; Muntean, R. Marble Powder as a Sustainable Cement Replacement: A Review of Mechanical Properties. Sustainability 2025, 17, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tazzini, A.; Gambino, F.; Casale, M.; Dino, G.A. Managing Marble Quarry Waste: Opportunities and Challenges for Circular Economy Implementation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, B.; Saravanan, T.J.; Kabeer, K.I.S.A.; Bisht, K. Exploring the potential of waste marble powder as a sustainable substitute to cement in cement-based composites: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 401, 132887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Ahmad, W.; Amin, M.N.; Ahmad, A.; Nazar, S.; Alabdullah, A.A.; Abu Arab, A.M. Exploring the Use of Waste Marble Powder in Concrete and Predicting Its Strength with Different Advanced Algorithms. Materials 2022, 15, 4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Ahmad, S.; Ullah, I. Utilization of waste marble dust as cement and sand replacement in concrete. Discov. Civ. Eng. 2024, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secil—Companhia Geral de Cal e Cimento. Environmental Product Declaration: CEM I 42.5R Portland Cement. EPD Norway, NEPD-10063-2. 2025. Available online: https://www.secil.pt (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Nadu, T. Study on the Properties of Concrete Incorporated With Various Mineral Admixtures-Limestone Powder and Marble Powder (Review Paper). Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2015, 1, 3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Aggarwal, N.; Rashid, S.; Srivastava, A.; Khapre, R. Marble Dust as a Sustainable Cementitious Material: Investigating the Synergistic Effects of Curing Conditions. SSRN 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cai, D.; Wang, T.; Hu, Q.; Li, K. Experimental analysis on the effects of artificial marble waste powder on concrete performance. Ann. Chim. Sci. Mater. 2018, 42, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashish, D.K. Feasibility of waste marble powder in concrete as partial substitution of cement and sand amalgam for sustainable growth. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 15, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhan, B.; Gao, P.; Hu, L.; Qiao, M.; Sha, H.; Yu, Q. Effects of recycled concrete powders on the rheology, setting and early age strength of cement paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 401, 132899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Bai, H.; Ma, L. Utilization of Recycled Concrete Powder in Cement Composite: Strength, Microstructure and Hydration Characteristics. J. Renew. Mater. 2021, 9, 2189–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorjev, V.; Azenha, M.; De Belie, N. Second Life for Recycled Concrete and Other Construction and Demolition Waste in Mortars for Masonry: Full Scope of Material Properties, Performance, and Environmental Aspects. Materials 2024, 17, 5118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawki, M.A.; Elnemr, A.; Koenke, C.; Thomas, C. Rheological properties of high-performance SCC using recycled marble powder. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2024, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oza, R.B.; Kangda, M.Z.; Agrawal, M.R.; Vakharia, P.R.; Solanki, D.S.M. Marble dust as a binding material in concrete: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 60, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, A.M. Waste marble valorisation in 3D cementitious materials printing. In WASTES: Solutions, Treatments and Opportunities IV, Proceedings of the 6th International Conference, Coimbra, Portugal, 6–8 September 2023; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashaly, A.O.; El-Kaliouby, B.A.; Shalaby, B.N.; El-Gohary, A.M.; Rashwan, M.A. Effects of marble sludge incorporation on the properties of cement composites and concrete paving blocks. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashish, D.K. Concrete made with waste marble powder and supplementary cementitious material for sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 716–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, M.Y.; Yehualaw, M.D.; Nebiyu, W.M.; Nebebe, M.D.; Taffese, W.Z. Marble and Glass Waste Powder in Cement Mortar. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, S.; Pederneiras, C.M.; Farinha, C.B.; de Brito, J.; Veiga, R. Reduction of the Cement Content by Incorporation of Fine Recycled Aggregates from Construction and Demolition Waste in Rendering Mortars. Infrastructures 2021, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliabdo, A.A.; Elmoaty, A.E.M.A.; Auda, E.M. Re-use of waste marble dust in the production of cement and concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 50, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Li, W.; Wu, H.; Cao, C. Chloride permeability of concrete mixed with activity recycled powder obtained from C&D waste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 199, 652–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgalhud, A.A.; Dhir, R.K.; Ghataora, G. Limestone addition effects on concrete porosity. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 72, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokareva, A.; Kaassamani, S.; Waldmann, D. Fine demolition wastes as Supplementary cementitious materials for CO2 reduced cement production. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 392, 131991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, S.; Sousa-Coutinho, J. Construction and demolition waste as partial cement replacement. Adv. Cem. Res. 2019, 31, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Kang, Z.; Zhan, B.; Gao, P.; Yu, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Bi, W.; Yang, C.; et al. Short Review on the Application of Recycled Powder in Cement-Based Materials: Preparation, Performance and Activity Excitation. Buildings 2022, 12, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khyaliya, R.K.; Kabeer, K.I.S.A.; Vyas, A.K. Evaluation of strength and durability of lean mortar mixes containing marble waste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 147, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, D.; Cheng, S.; Xu, X.; Zhao, C.; Wang, X.; Wu, Q.; Bai, X. Sustainable reuse of ceramic waste powder as a supplementary cementitious material in recycled aggregate concrete: Mechanical properties, durability and microstructure assessment. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 52, 104418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgalhud, A.A.; Dhir, R.K.; Ghataora, G.S. Carbonation resistance of concrete: Limestone addition effect. Mag. Concr. Res. 2017, 69, 84–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.F.C. Resíduos de Mármore e Resíduos de Construção e Demolição no Cimento, FEUP. 2016. Available online: https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/handle/10216/83983 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

| Constituent Materials/Pastes ID | CTL | 10CDW | 10MP | 5CDW + 5MP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water (g) | 142 | 142 | 142 | 142 |

| Cement (g) | 500 | 450 | 450 | 450 |

| CDW (g) | - | 50 | - | 25 |

| MP (g) | - | - | 50 | 25 |

| Constituent Materials | CTL | 10CDW | 10MP | 5CDW + 5MP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water (g) | 225 | 225 | 225 | 225 |

| Cement (g) | 450 | 405 | 405 | 405 |

| Sand (g) | 1350 | 1350 | 1350 | 1350 |

| CDW (g) | - | 45 | - | 22.5 |

| MP (g) | - | - | 45 | 22.5 |

| CEM I 42.5 R | CDW | MP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific gravity (kg/m3) | 3080 | 2620 | 2710 |

| Blaine fineness (cm2/g) | 4246 | 8439 | 9631 |

| Main Oxide composition (%) | CEM I 42.5 R | CDW | MP |

| LOI | 2.27 | 8.17 | 43.12 |

| SiO2 | 19.16 | 72.27 | 1.51 |

| Al2O3 | 4.45 | 5.1 | 0.53 |

| Fe2O3 | 3.5 | 3.25 | 0.17 |

| CaO | 63.75 | 8.27 | 53.93 |

| MgO | 1.87 | 0.28 | 0.65 |

| Na2O | 0.22 | 0.31 | <0.20 |

| K2O | 0.9 | 1.84 | 0.1 |

| SO3 | 3.26 | 0.31 | <0.1 |

| Cl− | 0.05 | <0.02 | <0.02 |

| Paste Identification | Standard Consistency (mm) | Initial Setting Time (mm) | Final Setting Time (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTL | 8 | 157 | 227 |

| 10CDW | 8 | 155 | 224 |

| 10MP | 8 | 137 | 197 |

| 5CDW + 5MP | 4 | 150 | 229 |

| Mortar Identification | Average Workability (mm) |

|---|---|

| CTL | 217.3 |

| 10CDW | 216.9 |

| 10MP | 217.7 |

| 5CDW + 5MP | 214.8 |

| Mortar Identification | Dns (×10−12 m2/s) |

|---|---|

| CTL | 14.2 ± 1.8 |

| 10CDW | 12.8 ± 0.6 |

| 10MP | 13.0 ± 0.9 |

| 5CDW + 5MP | 15.1 ± 0.4 |

| Mortar Identification | Sorptivity (mg/(mm2·min0.5)) |

|---|---|

| CTL | 0.0753 ± 0.003 |

| 10CDW | 0.0705 ± 0.005 |

| 10MP | 0.0740 ± 0.003 |

| 5CDW + 5MP | 0.0588 ± 0.007 |

| Mortar Identification | Average Carbonation Depth (mm) |

|---|---|

| CTL | 3.80 |

| 10CDW | 5.40 |

| 10MP | 5.80 |

| 5CDW + 5MP | 5.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matos, A.M.; Coutinho, J.S. Binary and Ternary Blends of Construction and Demolition Waste and Marble Powder as Supplementary Cementitious Materials. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10769. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310769

Matos AM, Coutinho JS. Binary and Ternary Blends of Construction and Demolition Waste and Marble Powder as Supplementary Cementitious Materials. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10769. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310769

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatos, Ana Mafalda, and Joana Sousa Coutinho. 2025. "Binary and Ternary Blends of Construction and Demolition Waste and Marble Powder as Supplementary Cementitious Materials" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10769. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310769

APA StyleMatos, A. M., & Coutinho, J. S. (2025). Binary and Ternary Blends of Construction and Demolition Waste and Marble Powder as Supplementary Cementitious Materials. Sustainability, 17(23), 10769. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310769