Incentive Mechanisms and the Allocation of Local Government Attention: A Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis of 36 Townships in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory and the Research Context

2.1. Conceptual and Theoretical Foundations of Governmental Attention

2.2. Analytical Strands in the Literature on Governmental Attention

| Theoretical Lens | Focus and Methods | Main Findings | Limitations | Representative References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attention Formation and Allocation | Behavioral and organizational studies; performance data; qualitative cases | Attention shifts with performance cues; negative feedback is more salient | Limited cross-level integration | Nielsen et al. (2014) [12] |

| Institutional Constraints | Institutional analysis; organizational theory | Rules and resource structures shape discretion and attention | Empirical work often fragmented | Yang et al. (2023, 2025) [15,18] |

| Incentive Mechanisms | Performance management; principal–agent designs | Incentives align behavior but risk goal displacement | Overemphasis on extrinsic drivers | Zhang et al. (2022) [21] |

| Normative and Care Ethics | Normative theory; frontline qualitative studies | Ethical duty and care shape attention beyond material incentives | Limited generalizability and integration | Rodela et al. (2025) [25] |

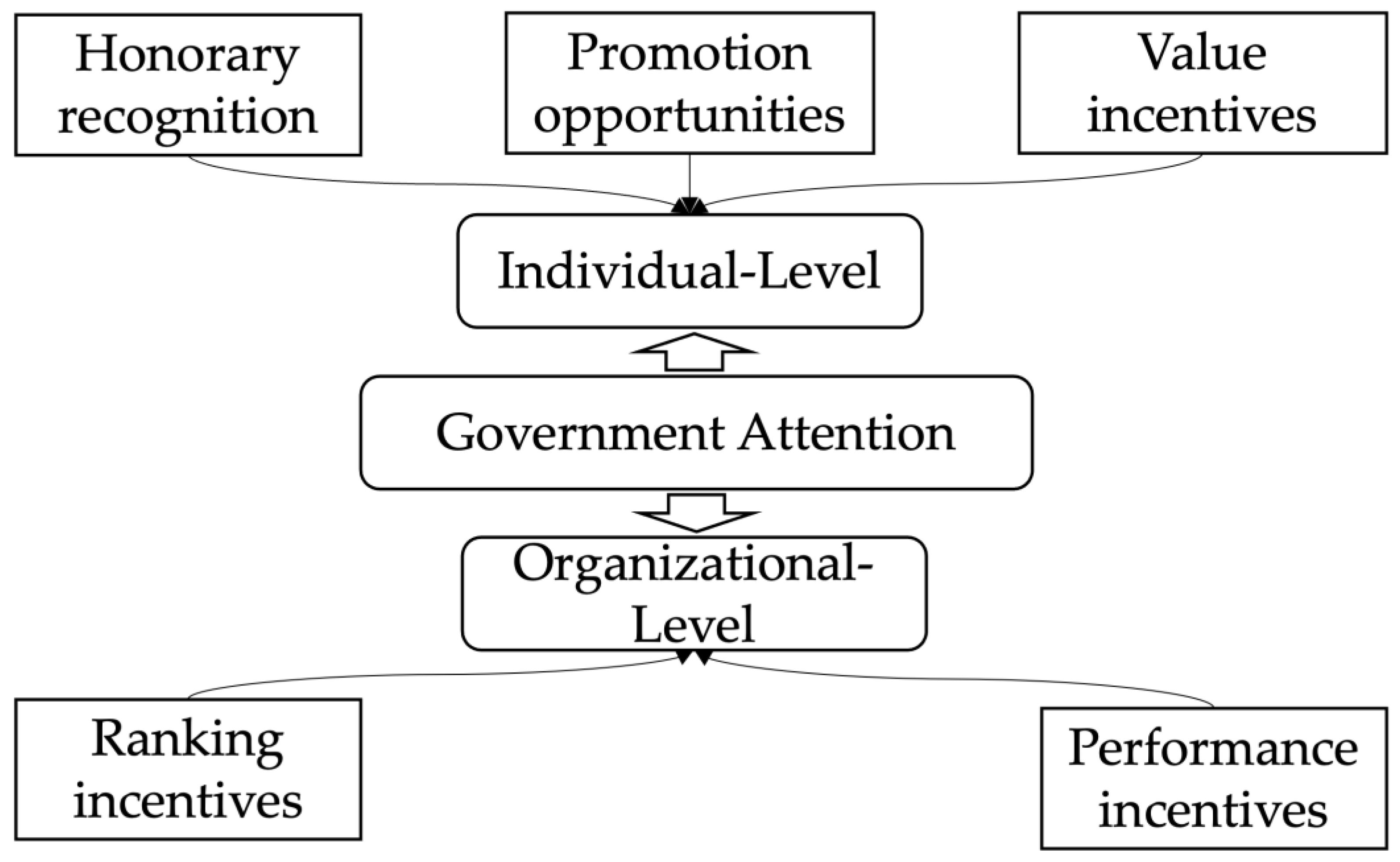

2.3. Determinants of Government Attention

2.3.1. Individual-Level Incentive Mechanisms

2.3.2. Organizational-Level Factors

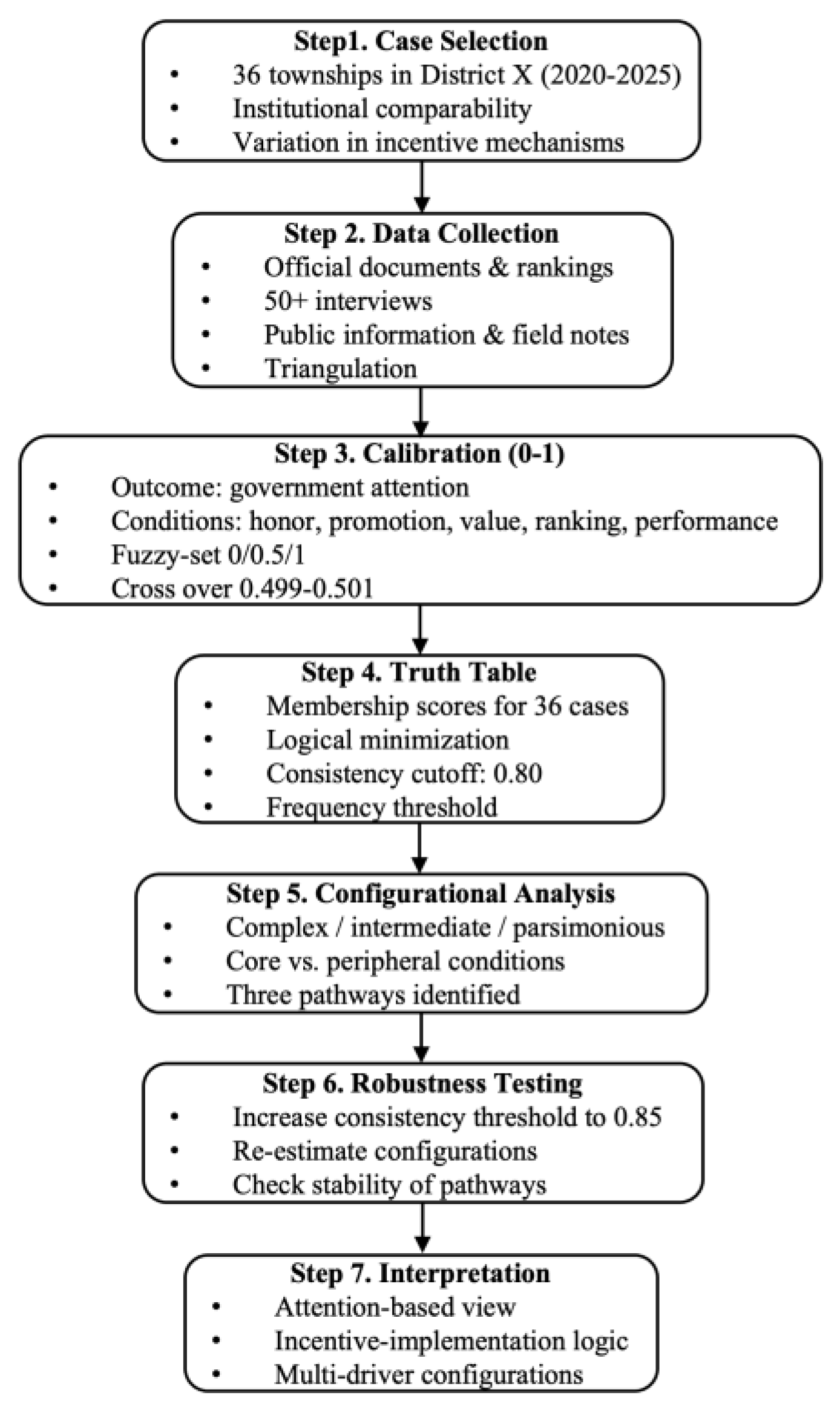

3. Research Design

3.1. Research Method

3.2. Data Sources

3.3. Variable Calibration and Data Triangulation

3.4. Variable Design

3.4.1. Outcome Variable

- (1)

- Individual attention focus

- (2)

- Organizational attention focus

3.4.2. Causal Conditions

3.5. Data Processing

4. Data Analysis and Empirical Results

4.1. Necessity Analysis

4.2. Configurational Analysis of Conditions

4.2.1. Competition-Driven Incentive Path

4.2.2. Honor–Value Compensatory Incentive Path

4.2.3. Comprehensive Incentive Path

4.3. Robustness Test

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- List A1. Sample Interview Guide

| ID | Gender | Age Group | Education | Affiliation | Contact Date | Follow-Up Date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 41–50 | University graduate | Township A—Administrative Staff | 01 | 13 July 2022 | 20 August 2024 |

| 2 | Female | 41–50 | University graduate | Township A—Mayor | 02 | 14 July 2022 | 18 August 2024 |

| 3 | Male | 31–40 | Postgraduate | Township B—Administrative Staff | 01 | 12 July 2022 | 29 August 2024 |

| 4 | Male | 31–40 | High school | Township BF—Party Secretary | 01 | 31 July 2022 | 23 August 2024 |

| 5 | Female | 51–60 | High school | Township B—Comprehensive Service Staff | 01 | 22 July 2022 | 20 August 2024 |

| 6 | Male | 51–60 | High school | Township C—Veterans Affairs Officer | 01 | 17 July 2022 | 29 August 2024 |

| 7 | Female | 51–60 | Postgraduate | Township C—Administrative Staff | 02 | 25 July 2022 | 16 August 2024 |

| 8 | Male | 41–50 | High school | Township D—Administrative Staff | 01 | 19 July 2022 | 18 August 2024 |

| 9 | Male | 41–50 | University graduate | Township D—Mayor | 02 | 13 July 2022 | 28 August 2024 |

| 10 | Male | 41–50 | High school | Township F—Veterans Affairs Officer | 01 | 18 July 2022 | 12 August 2024 |

| 11 | Female | 31–40 | University graduate | Township F—Service Center Director | 01 | 27 July 2023 | 17 August 2024 |

| 12 | Female | 31–40 | Postgraduate | Township I—Administrative Staff | 01 | 12 July 2023 | 13 August 2024 |

| 13 | Female | 51–60 | Postgraduate | Township I—Comprehensive Service Staff | 02 | 29 July 2023 | 21 August 2024 |

| 14 | Female | 31–40 | University graduate | Township J—Mayor | 01 | 20 July 2023 | 24 August 2024 |

| 15 | Female | 21–30 | Postgraduate | Township J—Comprehensive Service Staff | 01 | 22 July 2023 | 13 August 2024 |

| 16 | Female | 51–60 | Postgraduate | Township H—Mayor | 01 | 13 July 2023 | 18 August 2024 |

| 17 | Male | 41–50 | University graduate | Township H—Service Center Director | 02 | 17 July 2023 | 27 August 2024 |

| 18 | Female | 21–30 | High school | Township K—Service Center Director | 01 | 28 July 2023 | 19 August 2024 |

| 19 | Female | 51–60 | High school | Township K—Mayor | 02 | 23 July 2023 | 20 August 2024 |

| 20 | Male | 21–30 | Postgraduate | Township K—Party Secretary | 03 | 26 July 2023 | 17 August 2024 |

| 21 | Female | 51–60 | Postgraduate | Township I—Service Center Director | 01 | 29 July 2023 | 14 August 2024 |

| 22 | Male | 51–60 | University graduate | Township I—Veterans Affairs Officer | 02 | 19 July 2023 | 11 August 2024 |

| 23 | Female | 41–50 | University graduate | Township O—Mayor | 01 | 29 July 2023 | 16 August 2024 |

| 24 | Male | 21–30 | Postgraduate | Township O—Veterans Affairs Officer | 02 | 28 July 2023 | 14 August 2024 |

| 25 | Male | 51–60 | University graduate | Township M—Party Secretary | 01 | 23 July 2023 | 15 August 2024 |

| 26 | Female | 51–60 | University graduate | Township M—Administrative Staff | 02 | 30 July 2024 | 14 August 2025 |

| 27 | Female | 51–60 | High school | Township Mk—Comprehensive Service Staff | 01 | 22 July 2024 | 10 August 2025 |

| 28 | Male | 51–60 | Postgraduate | Township N—Mayor | 01 | 25 July 2024 | 22 August 2025 |

| 29 | Female | 41–50 | Postgraduate | Township Nl—Comprehensive Service Staff | 01 | 28 July 2024 | 17 August 2025 |

| 30 | Male | 41–50 | High school | Township LZ—Mayor | 01 | 16 July 2024 | 13 August 2025 |

| 31 | Male | 31–40 | Postgraduate | Township LZ—Comprehensive Service Staff | 02 | 10 July 2024 | 23 August 2025 |

| 32 | Male | 31–40 | University graduate | Township DP—Policy Researcher | 01 | 14 July 2024 | 25 August 2025 |

| 33 | Female | 31–40 | University graduate | Township DP—Administrative Staff | 02 | 27 July 2024 | 19 August 2025 |

| 34 | Female | 21–30 | Postgraduate | Township IF—Service Center Director | 01 | 15 July 2024 | 17 August 2025 |

| 35 | Female | 21–30 | Postgraduate | Township IF—Policy Researcher | 02 | 17 July 2024 | 23 August 2025 |

| 36 | Male | 21–30 | Postgraduate | Township PC—Administrative Staff | 01 | 14 July 2024 | 15 August 2025 |

| 37 | Male | 31–40 | Postgraduate | Township OF—Mayor | 01 | 21 July 2024 | 10 August 2025 |

| 38 | Male | 41–50 | University graduate | Township GH—Mayor | 01 | 26 July 2023 | 20 August 2025 |

| 39 | Female | 51–60 | University graduate | Township GK—Administrative Staff | 01 | 28 July 2023 | 19 August 2025 |

| 40 | Female | 31–40 | University graduate | Township JL—Administrative Staff | 01 | 17 July 2022 | 19 August 2025 |

| 41 | Male | 31–40 | High school | Township HO—Mayor | 01 | 18 July 2022 | 13 August 2025 |

| 42 | Female | 21–30 | University graduate | Township FP—Policy Researcher | 01 | 13 July 2023 | 21 August 2025 |

| 43 | Male | 31–40 | Postgraduate | Township W—Party Secretary | 01 | 27 July 2024 | 27 August 2025 |

| 44 | Female | 41–50 | Postgraduate | Township W—Veterans Affairs Officer | 02 | 27 July 2024 | 18 August 2025 |

| 45 | Female | 21–30 | Postgraduate | Township R—Policy Researcher | 01 | 26 July 2024 | 17 August 2025 |

| 46 | Male | 31–40 | High school | Township RO—Party Secretary | 01 | 15 July 2024 | 13 August 2025 |

| 47 | Female | 21–30 | University graduate | Township Y—Administrative Staff | 01 | 28 July 2024 | 15 August 2025 |

| 48 | Female | 51–60 | University graduate | Township DI—Mayor | 01 | 13 July 2024 | 12 August 2025 |

| 49 | Male | 51–60 | Postgraduate | Township GK—Administrative Staff | 01 | 16 July 2024 | 30 August 2025 |

| 50 | Male | 21–30 | University graduate | Township IL—Comprehensive Service Staff | 01 | 26 July 2024 | 20 August 2025 |

| ID | Honor Recognition | Promotion Opportunity | Value Incentive | Ranking Incentive | Performance Incentive | Government Attention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 0.501 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.501 |

| 2 | 1 | 0.499 | 0.499 | 0.501 | 0.499 | 0.499 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0.501 | 1 | 0.501 | 0.501 |

| 4 | 0.33 | 0 | 0 | 0.499 | 0 | 0.2495 |

| 5 | 1 | 0.501 | 0 | 0.501 | 0.501 | 0.501 |

| 6 | 0.33 | 0 | 0.499 | 0 | 0 | 0.2505 |

| 7 | 1 | 0.501 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.7505 |

| 8 | 0.33 | 0 | 0.499 | 0.499 | 0.499 | 0.499 |

| 9 | 0.33 | 0 | 0.499 | 0.499 | 0 | 0.2495 |

| 10 | 0.33 | 0.499 | 1 | 1 | 0.501 | 0.501 |

| 11 | 0.33 | 0.499 | 0.501 | 0 | 0 | 0.7505 |

| 12 | 1 | 0.501 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.501 |

| 13 | 1 | 0 | 0.499 | 1 | 0 | 0.499 |

| 14 | 0.33 | 0 | 0.499 | 1 | 0.499 | 0.7495 |

| 15 | 1 | 0.499 | 1 | 0.501 | 0.499 | 0.7495 |

| 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.2495 |

| 17 | 0.33 | 0 | 0.501 | 0.499 | 0.499 | 0.2495 |

| 18 | 1 | 0.501 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 19 | 0.67 | 0 | 0.499 | 0 | 0 | 0.7505 |

| 20 | 0.67 | 0.501 | 0.499 | 0.501 | 0.499 | 0.2495 |

| 21 | 1 | 0.501 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 22 | 1 | 0.501 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.7505 |

| 23 | 1 | 0 | 0.501 | 1 | 1 | 0.7505 |

| 24 | 1 | 0 | 0.501 | 0 | 0.499 | 0.7495 |

| 25 | 1 | 0.501 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 26 | 0.67 | 0 | 0.499 | 1 | 0.499 | 0.7505 |

| 27 | 0.33 | 0 | 0.499 | 0.499 | 0 | 0.2495 |

| 28 | 1 | 0.501 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 29 | 0.33 | 0.499 | 0.499 | 0 | 0.501 | 0.501 |

| 30 | 0.33 | 0 | 0.499 | 0 | 0 | 0.2495 |

| 31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2495 |

| 32 | 0.33 | 0.499 | 0.499 | 0 | 0.501 | 0.501 |

| 33 | 1 | 0.501 | 1 | 0.501 | 1 | 0.7505 |

| 34 | 0.33 | 0.501 | 1 | 0.501 | 0.501 | 0.7505 |

| 35 | 0.67 | 0.501 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 36 | 0.67 | 0 | 1 | 0.501 | 0.501 | 0.501 |

| Models from Subsample | Raw Coverage | Unique Coverage | Consistency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Honor recognition ×~ Promotion opportunity ×~ Performance incentive | 0.415 | 0.032 | 0.876 |

| Value incentive × Ranking incentive × Performance incentive | 0.524 | 0.167 | 0.880 |

| Honor recognition ×~ Value incentive ×~ Ranking incentive ×~ Performance incentive | 0.265 | 0.000 | 0.819 |

| Honor recognition × Promotion opportunity × Value incentive × Performance incentive | 0.337 | 0.048 | 0.966 |

| ~Honor recognition ×~ Promotion opportunity ×~ Value incentive × Performance incentive | 0.095 | 0.016 | 0.858 |

| Overall solution consistency | 0.856 | ||

| Overall solution coverage | 0.822 | ||

References

- Bao, R.; Liu, T. How does government attention matter in air pollution control? Evidence from government annual reports. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 185, 106435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.C. The politics of attention: How government prioritizes problems. Soc. Forces 2006, 85, 1042–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Wilson, J.; Tao, X.; Lv, B.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, W. Influence of government attention on environmental quality: An analysis of 30 provinces in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 100, 107084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhou, M.; Yu, H. Is more always better? Government attention and environmental governance efficiency: Empirical evidence from China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.A. Does performance information receive political attention? Public Adm. Rev. 2023, 83, 763–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. Administrative Behavior; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ocasio, W. Towards an attention-based view of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Miao, X.; Feng, E.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Y. Urban governmental environmental attention allocation: Evidence from China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2023, 149, 04022055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwaan, P.; Elemans, S.; André, S.; van Genugten, M. Attention please! Explaining local governments’ political attention for Europe. Local Gov. Stud. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawadhi, S.; Aldama-Nalda, A.; Chourabi, H.; Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Leung, S.; Mellouli, S.; Nam, T.; Pardo, T.A.; Scholl, H.J.; Walker, S. Building understanding of smart city initiatives. In Electronic Government, Proceedings of the 11th IFIP WG 8.5 International Conference, EGOV 2012, Kristiansand, Norway, 3–6 September 2012; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 40–53. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, B.D.; Baumgartner, F.R. The Politics of Attention: How Government Prioritizes Problems; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, P.A. Learning from performance feedback: Performance information, aspiration levels, and managerial priorities. Public Adm. 2014, 92, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S. A behavioral model of public organizations: Bounded rationality, performance feedback, and negativity bias. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2019, 29, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Meyer-Doyle, P. How performance incentives shape individual exploration and exploitation: Evidence from microdata. Organ. Sci. 2017, 28, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Qin, C.; Fan, B. Do institutional pressures increase reactive transparency of government? Evidence from a field experiment. Public Manag. Rev. 2023, 25, 2073–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, D.P.; Pandey, S.K. The big question for performance management: Why do managers use performance information? J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2010, 20, 849–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukhriddinovich, E.D. Analysis of the policy of the republic of Uzbekistan regarding international non-governmental organization. J. Political Sci. Int. Relat. 2020, 3, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W. Institutional Pressures and Bureaucratic Responsiveness: Why Do Public Agencies Respond to Freedom of Information Requests? Public Adm. Rev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, P.B.; Green-Pedersen, C. Institutional effects of changes in political attention: Explaining organizational changes in the top bureaucracy. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2015, 25, 165–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Wu, M. Multiple institutional pressures, government attention allocation, and regional environmental performance: A fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis study across (FSQCA) 30 provinces in China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1642985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Bi, Y.; Kang, F.; Wang, Z. Incentive mechanisms for government officials’ implementing open government data in China. Online Inf. Rev. 2022, 46, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanhill, S. Role of government incentives. In Global Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 367–390. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Yi, X.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y. Blockchain-based design of a government incentive mechanism for manufacturing supply chain data governance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugarin, M.; Vieira, L. Benefit sharing: An incentive mechanism for social control of government expenditure. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2008, 48, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rodela, R.; Williams, M.; Ohlsson, J.; Sandström, I. Six propositions for care-centric planning and governance that promote sustainable cities. npj Urban Sustain. 2025, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.J.; Fuenzalida, J.; Gómez, M.; Williams, M.J. Four lenses on people management in the public sector: An evidence review and synthesis. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2021, 37, 335–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abudureheman, M. The Impact of the Digital Economy on Energy Rebound: A Booster or Inhibitor? Economies 2025, 13, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, E.; Linder, C.; De Massis, A.; Eddleston, K.A. Employee incentives and family firm innovation: A configurational approach. J. Manag. 2024, 50, 1797–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drury, P. Designing incentive pay practices to motivate not alienate: Why firms adopt different payment practice configurations in different countries. Hum. Resour. Manag. Int. Dig. 2016, 24, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercure, J.F.; Salas, P.; Vercoulen, P.; Semieniuk, G.; Lam, A.; Pollitt, H.; Holden, P.B.; Vakilifard, N.; Chewpreecha, U.; Edwards, N.R.; et al. Reframing incentives for climate policy action. Nat. Energy 2021, 6, 1133–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Yan, Z.; Liang, X.; Yang, L.T. How can incentive mechanisms and blockchain benefit with each other? a survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 55, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, M.L.; Baekgaard, M.; Moynihan, D.P.; van Loon, N. Making sense of performance regimes: Rebalancing external accountability and internal learning. Perspect. Public Manag. Gov. 2018, 1, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L. Performance feedback, government goal-setting and aspiration level adaptation: Evidence from Chinese provinces. Public Adm. 2016, 94, 452–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neo, S.; Grimmelikhuijsen, S.; Tummers, L. Core values for ideal civil servants: Service-oriented, responsive and dedicated. Public Adm. Rev. 2023, 83, 838–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, P.J.; Workman, S.; Jones, B.D. Organizing attention: Responses of the bureaucracy to agenda disruption. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 517–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purba, I.B.A.H. Enhancing budget policy alignment: Insights from local government practices. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2025, 25, 019–023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Liao, W. Legislation, plans, and policies for prevention and control of air pollution in China: Achievements, challenges, and improvements. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1549–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragin, C.C. Redesigning Social Inquiry: Fuzzy Sets and Beyond; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ragin, C.C.; Rihoux, B. Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA): State of the art and prospects. Qual. Methods 2004, 2, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D.T.; Stanley, J.C. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research; Rand McNally: Chicago, IL, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Resane, K.T. Honorary degree qualifications from unaccredited institutions: Anathema for Pentecostal self-discovery. Stellenbosch Theol. J. 2024, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyawati, N.W.; Pg, D.S.W.; Rianto, M.R. Career development, motivation and promotion on employee performance. East Asian J. Multidiscip. Res. 2022, 1, 1957–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taba, M.I. Mediating effect of work performance and organizational commitment in the relationship between reward system and employees’ work satisfaction. J. Manag. Dev. 2018, 37, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Wang, C.; Zhai, W.; Li, W. “Honor list” and “shame roll”: Quasi-experimental evidence of the effect of performance feedback under political control. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2023, 33, 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barankay, I. Rank incentives: Evidence from a Randomized Workplace Experiment; 2012 Working Paper; Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012; Available online: https://repository.upenn.edu/items/69bf8b73-eaf9-4b4a-a910-b3afd753b0cc (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Bhattacharya, H.; Dugar, S. Status incentives and performance. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2012, 33, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, L. What drives the governance of ridesharing? A fuzzy-set QCA of local regulations in China. Policy Sci. 2019, 52, 601–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verweij, S. Achieving satisfaction when implementing PPP transportation infrastructure projects: A qualitative comparative analysis of the A15 highway DBFM project. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, K.; Fishbach, A. The experience matters more than you think: People value intrinsic incentives more inside than outside an activity. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 109, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, N. The effectiveness of monetary and promotion rewards in the public sector and the moderating effect of PSM (PSM-reward fit or PSM crowding out): A survey experiment. Adm. Soc. 2022, 54, 277–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, A.; Beikzad, J.; Abdollahfam, R. Identification and Prioritization of Indicators for Enhancing the Symbolic Capital of Managers (Case Study: SAIPA Automotive Group). Future Work. Digit. Manag. J. 2024, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Lin, J.; Song, F.; Ho, M.S. Performance and challenges of power sector reform in China since 2015. iScience 2025, 28, 113461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazear, E.P. Compensation and incentives in the workplace. J. Econ. Perspect. 2018, 32, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ienna, G.; Omodeo, P.D. The Bee and the Architect. Scientific Paradigms and Historical Materialism; Verum Factum: Venice, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X. Rigid control and embedded innovation: Philanthropy in Chinese higher education. In Advancing Research in Philanthropy and Education; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2025; pp. 101–133. [Google Scholar]

- David, N.; Brennecke, J.; Rank, O. Extrinsic motivation as a determinant of knowledge exchange in sales teams: A social network approach. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 59, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assanti, S. Configuring high-performance work systems in public administration: A set-theoretic approach to explain organizational performance in swiss municipalities. Front. Political Sci. 2025, 7, 1504394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oana, I.E.; Schneider, C.Q. A robustness test protocol for applied QCA: Theory and R software application. Sociol. Methods Res. 2024, 53, 57–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qomariah, N.; Nyoman, N.; Martini, P. The Influence of Leadership Style, Work Incentives and Work Motivation on the Employees Performance of Regional Revenue Agency. J. Econ. Financ. Manag. Stud. 2022, 5, 1942–1954. [Google Scholar]

- Bach, T.; De Francesco, F.; Maggetti, M.; Ruffing, E. Transnational bureaucratic politics: An institutional rivalry perspective on EU network governance. Public Adm. 2016, 94, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, B.; van der Wal, Z. Does Performance-Related-Pay work? Recommendations for practice based on a meta-analysis. Policy Des. Pract. 2023, 6, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliverti, A.J.; Tawfic, S. Caring states? Bureaucratic care, moral ideals and emotional dilemmas in British asylum and policing. Theor. Criminol. 2025, 13624806241310446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, P. Care ethics and public administration. In The Bloomsbury Handbook of Care Ethics; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2025; Volume 335. [Google Scholar]

- Bertelli, A.; Riccucci, N.; Canterelli, P.; Cucciniello, M.; Grose, C.; John, P.; Linos, E.; Thomas, A.; Williams, M. The (Missing?) role of institutions in behavioral public administration: A roundtable discourse. J. Behav. Public Adm. 2022, 5, e260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Deng, J.; Li, X.; Ma, J.; He, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, C. The mechanism of blockchain technology in safety risk monitoring. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Deng, J.; Li, X.; Huang, W.; Wang, C.; Wang, X. Investment in enhancing resilience safety of chemical parks under blockchain technology: From the perspective of dynamic reward and punishment mechanisms. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2025, 94, 105523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Data Source |

|---|---|

| Individual attention focus | In-depth interviews (staff/managers); personal reports (e.g., diaries, work logs); meeting minutes |

| Organizational attention focus | In-depth interviews; strategic plans; meeting minutes |

| Honorary recognition | Official award lists/bulletins; media reports of honors; interviews with honorees/officials |

| Promotion opportunities | Personnel promotion records; promotion policy documents; interviews on career paths |

| Value incentives | Mission/vision statements; value-oriented training materials; interviews about values |

| Ranking incentives | Published performance rankings; evaluation reports; interviews on ranking systems |

| Performance incentives | Bonus budget/reports; performance appraisal criteria; interviews on incentives |

| Variable Type | Dimension | Variable | Category | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Causal Condition | Incentive Techniques | Honor Recognition |

| 1 |

| 0.67 | |||

| 0.33 | |||

| 0 | |||

| Promotion Opportunities |

| 1 | ||

| 0.5 | |||

| 0 | |||

| Value Incentives |

| 1 | ||

| 0.5 | |||

| 0 | |||

| Ranking Incentives |

| 1 | ||

| 0.5 | |||

| 0 | |||

| Performance Incentives |

| 1 | ||

| 0.5 | |||

| 0 | |||

| Outcome Variable | Attention Focus | Individual Focus |

| 1 |

| 0.5 | |||

| 0 | |||

| Organizational Focus |

| 1 | ||

| 0.5 | |||

| 0 |

| Condition | High-Level Attention Focus | |

|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Coverage | |

| High honor recognition | 0.837 | 0.776 |

| Low honor recognition | 0.385 | 0.605 |

| High promotion opportunities | 0.441 | 0.974 |

| Low promotion opportunities | 0.809 | 0.641 |

| High value incentives | 0.845 | 0.807 |

| Low value incentives | 0.440 | 0.660 |

| High ranking incentives | 0.655 | 0.724 |

| Low ranking incentives | 0.535 | 0.661 |

| High performance incentives | 0.738 | 0.886 |

| Low performance incentives | 0.535 | 0.608 |

| Conditional Factors | High-Level Attention Focus | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Competition-Driven Incentive | Honor–Value Compensatory Incentive | Comprehensive Incentive | |

| Honor recognition | ● | ● | |

| Promotion opportunities | ○ | ● | |

| Value incentives | ● | ● | ● |

| Ranking incentives | ● | ||

| Performance incentives | ● | ○ | ● |

| Raw coverage | 0.524 | 0.348 | 0.337 |

| Unique coverage | 0.186 | 0.135 | 0.048 |

| Consistency | 0.880 | 0.918 | 0.966 |

| Overall consistency | 0.895 | ||

| Overall coverage | 0.738 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cai, H.; Wang, X.; Gao, E. Incentive Mechanisms and the Allocation of Local Government Attention: A Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis of 36 Townships in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310760

Cai H, Wang X, Gao E. Incentive Mechanisms and the Allocation of Local Government Attention: A Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis of 36 Townships in China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310760

Chicago/Turabian StyleCai, Huaping, Xue Wang, and Enxin Gao. 2025. "Incentive Mechanisms and the Allocation of Local Government Attention: A Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis of 36 Townships in China" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310760

APA StyleCai, H., Wang, X., & Gao, E. (2025). Incentive Mechanisms and the Allocation of Local Government Attention: A Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis of 36 Townships in China. Sustainability, 17(23), 10760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310760