1. Introduction

As a major contributor to economic outcomes, food insecurity, and environmental strain, food waste is a far-reaching problem with national and global consequences. Worldwide, food waste amounts to over 1 billion tons and USD 940 billion in economic losses annually [

1]. In the U.S., 40% of food is lost or wasted each year, costing an estimated USD 218 billion [

2]. But, despite all this wasted food, food insecurity (i.e., uncertainty in having or inability to acquire adequate food for one’s household due to insufficient resources) affected 17 million U.S. households at some time during 2022 [

3]. This degree of food insecurity is in some ways a function of food prices, which can be reduced via reducing consumer food waste (i.e., lowering food demand and production [

4]). Finally, beyond its economic and societal impacts, food waste is the largest source of human-related methane emissions in the U.S. and contributes to a wide range of environmental impacts including climate change, air pollutants, water scarcity, biodiversity loss, and soil and water quality degradation [

2]. Thus, initiatives to reduce food waste have the potential to positively contribute to the economy, societal well-being, and the environment.

In June 2024, the U.S. White House, USDA, EPA, and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced the National Strategy for Reducing Food Loss and Waste and Recycling Organics as part of President Biden’s whole-of-government approach to tackle climate change, feed people, address environmental justice, and promote a circular economy [

5]. The strategy includes plans to develop, launch, and run a national food waste consumer education and behavior change campaign. Targeting consumers is a high priority for food waste reduction, given that roughly half of food waste occurs during the consumption phase by households and food service [

6]. Moreover, food waste at the consumption phase carries larger environmental and economic cost than food losses upstream (e.g., farms or manufacturing [

7]). As such, a consumer-facing behavior change campaign could have significant impacts, and its success depends on the effectiveness of its interventions.

To date, many consumer-facing food waste interventions have demonstrated mixed effectiveness for several reasons. First, there is a general lack of theoretical framing of intervention studies, such that the mechanisms through which interventions have their effects are not sufficiently articulated [

8]. Thus, it is difficult to determine why an intervention did or did not demonstrate significant effects on food waste behaviors or amounts. Second, studies demonstrate significant methodological heterogeneity, which makes it difficult to come to an overall assessment of existing interventions in the field. Specifically, several review and meta-analysis papers have emphasized that there is significant heterogeneity in terms of experimental design (i.e., including “fair” control conditions (An example of a “fair” treatment-to-control comparison is Roe et al. [

9]: the treatment group received a highly individualized food waste reduction intervention, and the control group received a highly individualized (“intensity-matched”) stress management intervention. This study represents a more rigorous test of the intervention when comparing treatment and control groups and exemplifies the need for appropriate control groups.)), measurement of the outcome variable (i.e., measuring wasted food, including a pre-intervention measure), and using adequate statistical analyses [

8,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Finally, many interventions utilize a one-size-fits-all approach and do not consider the need for tailoring interventions to particular households and lifestyles [

9]. This is particularly worrisome due to the most effective intervention likely being one that targets individuals’ specific interests and motivations—as has been demonstrated in several areas regarding behavioral change (e.g., health [

14]; well-being [

15]; workplace [

16]).

Thus, the current study is designed to compare two different intervention approaches in an online experiment using random assignment and measuring self-reported food waste and behaviors before and after the intervention. Specifically, we compare an informational intervention approach and a behavioral intervention approach, testing (1) which informational conditions demonstrate a stronger effect on food waste and behaviors (i.e., “save money” versus “save money, reduce environmental impact, and help others”) and (2) whether asking individuals to set if-then plans for themselves are incrementally effective relative to only providing food waste-related information. In doing so, we hope to extend the current literature by comparing these two common intervention paradigms.

2. Literature Review

The goal of the current study is to identify ways to help individuals reduce their household food waste. Thus, the amount of household food waste is the ultimate focus of this study. Borrowing language from intervention models in behavioral health and organizational science [

17,

18], food waste reduction is the distal outcome of the intervention. To impact distal outcomes, the intervention must first focus on impacting proximal outcomes: the behaviors, thoughts, and patterns that determine whether a household wastes more or less food (distally).

Thus, the current intervention adopts an informational and behavioral approach to influencing these proximal outcomes so as to, ultimately, reduce food waste. To guide the intervention’s design, we utilize the Theory of Planned Behavior [

19] as a framework to determine how best to intervene in the process of attaining one’s goal—which, in the present study, is food waste reduction.

In general, positive and cognitively accessible attitudes towards specific goal-relevant behaviors are more likely to give rise to those specific behaviors [

20]. Thus, informational interventions can be delivered that bolster goal-relevant attitudes and, indirectly, promote the attainment of those goals [

8]. However, there is often a gap between attitudes and behavior. In this regard, the Theory of Planned Behavior suggests that behavioral intentions are a more proximal determinant of behavior, but those intentions themselves are influenced by attitudes [

21]. Thus, behavioral interventions that focus on this proximal link between intentions and behaviors stand to be especially effective in promoting goal attainment [

22].

2.1. Informational Approach

In their review of food waste intervention studies, the [

8] found that many studies focus on informational messaging: making individuals aware of the costs and environmental impact of food waste; posting signage in grocery stores; tips to prevent food waste and so forth. In general, such an approach to behavior change assumes that people will utilize relevant, useful information and adjust their behaviors accordingly.

An informational approach to food waste reduction may be especially useful to the extent that it targets issues relevant to people’s lifestyles. Typically, messaging about food waste focuses on the potential to save money, to benefit the environment, and to feed families suffering from food insecurity [

23]. For example, the goals of the recently announced National Strategy for Reducing Food Loss and Waste and Recycling Organics [

5] are to “substantially reduce environmental impacts” and to “provide social and economic benefits that can help address the needs of underserved communities” (p. 4).

Thus, it seems critical to evaluate whether these messages can influence food waste behaviors and ultimately reduce food waste. However, it is possible that certain messages are more effective than others. In a nationally representative survey, saving money was found to be a key predictor of self-reported food waste amounts and was the most commonly cited concern related to food waste, whereas environmental concerns were seemingly less important—and even related to higher food waste [

24].

Therefore, the present study evaluated whether a money-saving message alone was as impactful as a holistic message about saving money, reducing environmental impact, and helping others. These messages were delivered in narrative fashion, as some evidence suggests that stories create more openness to information than information presented as facts and statistics [

25].

Hypothesis 1. Participants who are assigned to an informational intervention (i.e., a “save money” message or a “holistic” message) will demonstrate (a) increased food waste reduction behaviors and (b) decreased food waste, relative to participants who are assigned to a control condition (i.e., a “sitting behavior” message).

Research Question 1. Is there a difference in (a) food waste reduction behaviors and (b) food waste between participants who receive the “save money” message versus participants who receive the “holistic” message?

However, the provision of information alone may not be sufficient to change food waste behaviors. As stated by Hebrok and Heidenstrøm [

26]: “Informing consumers about food waste as a societal problem is not sufficient enough to change how they handle food as part of their complex and interwoven everyday lives” (p. 1437). For example, general information about the benefits of reducing food waste may not be utilized if the information is not perceived as directly relevant to their lifestyles [

27]. Thus, in the next section, we discuss a behavioral approach that may be impactful above and beyond an informational approach.

2.2. Behavioral Approach

As stated by the Theory of Planned Behavior, intentions are crucial predictors for behavior, but intentions alone are not sufficient to understand when a person will achieve their goals and execute the most appropriate behaviors [

28]. This is likely to be especially the case for intentions to reduce food waste because there are many other ongoing goal pursuits that occupy people’s daily lives and that may take priority, and, even more simply, reducing food waste is hard [

26].

However, mirroring the gap between attitudes and behavior, intentions, too, do not always lead to the intended behavior [

22]. One way to improve the effectiveness and situational relevance of intentions is via implementation intentions [

29], which are if–then action plans through which a person specifies a situation (“If situation

x arises…”) and an action to be performed (“… Then I will perform response

y”). By setting such intentions, people are more likely to attain their goals because they have made a relevant situational cue accessible and tethered it to an appropriate goal-directed action: “People are in a good position both to see and to seize suitable opportunities to pursue their goals” (p. 300, [

30]). Thus, when situational conditions match the cues formed while creating implementation intentions, people are more likely to recall and act upon their goals.

We reason that this behavioral approach to food waste reduction will be incrementally effective above and beyond a purely informational approach for several reasons. First, implementation intentions can effectively “shield” a person’s goal to reduce food waste from becoming derailed by other concerns and goal pursuits (e.g., having sufficient food for the whole family during holidays), while also ensuring that such goal pursuit does not allow people to overextend themselves [

31]. Thus, any food waste-related information may be better preserved by the act of setting intentions. Second, setting implementation intentions inherently involves tailoring one’s action plans to one’s household patterns, one’s lifestyle, and so forth, rather than taking a “one size fits all” approach to food waste reduction [

26]. Third, there is a significant amount of evidence that documents the effectiveness of implementation intentions on behavior change outcomes across a range of domains [

32]. As such, a recent review paper recommended intention-setting as a framework for food waste reduction [

33].

Therefore, the present study evaluated whether setting implementation intentions had a stronger impact on food waste relative to only reading informational food waste narrative messages.

Hypothesis 2. Participants who are assigned to set implementation intentions will demonstrate (a) increased food waste reduction behaviors and (b) decreased food waste, relative to participants who only receive the informational intervention and who do not set implementation intentions.

2.3. Current Study Design

The current study has been designed to compare informational versus behavioral approaches to household food waste interventions in the U.S. context. Due to the lightweight nature of these interventions, we have selected a relatively short time frame of two weeks to observe whether there are immediate, proximal changes in food waste behaviors and amounts, though it is possible that these interventions require longer periods of time for uptake and that their effects may regress over time. Additionally, we have opted to utilize self-reports for measures of key outcomes due to this method being previously validated [

24], straightforward to implement, and also relatively convergent with more objective, intensive measurement methods [

34,

35]. However, these methods are unlikely to be as accurate as objective methods, and they may be subject to additional biases. Finally, though we have sought to make all conditions as similarly “strong” to allow for a fair comparison [

36], it is possible that the purely informational approach is simply “weaker” than the behavioral approach [

8]. However, we preferred this comparison, even despite the possible difference in strength, because it closely approximates how these approaches are utilized in the “real world”.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

Prior to recruitment, we conducted a one-tailed power analysis using G*Power (3.1) with alpha set at 0.05 and power at 0.80 for both an independent t-test (i.e., comparing participants assigned to different conditions) and a dependent t-test (i.e., comparing participants over time). The required sample size to detect small effects (d = 0.20) was 310 per condition for the independent t-test and 272 per condition for the dependent t-test. Thus, given these power considerations and our financial resources, we aimed to recruit at least 1500 participants (i.e., due to there being five study conditions).

We initially recruited 1999 adults from Prolific, an online participant panel platform, to complete Survey 1. However, we did not invite 31 participants to complete Survey 2 (two weeks later) due to failing the embedded attention check or for otherwise demonstrating low effort in responding to the survey. Additionally, of this number, we were only able to allow 1500 to complete Survey 2 due to financial resource limitations. Thus, 1494 successfully completed Survey 1 and Survey 2 and was the final sample size for this study. As compensation for their time, participants received USD 12 dollars for completion of the full study (USD 5.00 for Survey 1 and USD 7.00 for Survey 2).

As can be seen in

Table 1 below, the sample consisted of a balanced representation of age, gender, household size, employment, and income generally consistent with national demographics. The sample comprised U.S. households. The sample reported an above-average level of education compared to the national average, with 86.9% of the sample having education beyond a high school graduate whereas only 63.3% of the nation is reported to have pursued education beyond high school [

37].

3.2. Procedure and Measures

This study involved two surveys: Survey 1 was completed by participants on Monday, 19 August 2024, and Survey 2 was completed by participants two weeks later between Monday, September 2, and Tuesday, September 3. Each survey took participants approximately 10–12 min to complete. The research was approved by the institutional review board of The MITRE Corporation.

In Survey 1, participants first provided informed consent and then reported their household’s food waste (in cups and tablespoons) and food waste-related behaviors over the past week. To measure household food waste, we adapted the self-report method used by [

24]. Participants were told: “Please think about all the food that gets thrown away or disposed of

at your home. By disposed food, we mean food that went in the trash bin, in the compost, or down the sink drain. This includes food wasted by all members currently residing in your household and any foods you purchased from a store, market, or a restaurant, obtained at a food bank or pantry, received as a gift, or grown or raised yourself.” Then, participants were asked to estimate approximately how many cups (i.e., the size of a closed fist) and tablespoons (i.e., the size of a thumb) of food was wasted in their households “in the past 7 days” for each of the following categories: fruit, vegetables, grains, protein, dairy, mixed, scraps, and oils, fats, and sugars. Excluding scraps, these amounts were summed to form a total measure of household food waste. Of note, despite noted limitations of self-reported food waste measures, this method has demonstrated moderate convergent validity with a diary-based, objective measure of food waste [

34].

To measure food waste-related behaviors, participants reported the frequency with which they enacted behaviors related to food acquisition (i.e., checking food at home before shopping, making and sticking to shopping lists), date label wasting (i.e., wasting food because it had passed its date label), and leftover usage (i.e., using leftovers as ingredients, eating leftovers as meals, prioritizing leftovers close to expiration, throwing away leftovers). These behaviors were measured by adapting items published in the MITRE Gallup State of Food Waste in America report [

24].

Next, participants were randomly assigned to one of three narrative messages: (1) a “money” message wherein a narrator described their attempts to reduce food waste in order to save money; (2) a “holistic” message wherein a narrator described their attempts to reduce food waste in order to save money, reduce negative environmental consequences, and help the food-insecure; or (3) a “sitting” control message that was unrelated to food waste and included a narrator’s description of their efforts to reduce sitting behavior to improve their health. The full text of these messages can be found in the online

Supplementary Materials S1–S3.

Then, participants who read the “money” and “holistic” messages were randomly assigned to either set implementation intentions or were not prompted to set implementation intentions. Participants assigned to set intentions were first told: “Implementation intentions are simple IF-THEN statements that describe (1) a situation (e.g., point in time, place) relevant to your goal, and (2) an action to be performed relevant to your goal. The basic structure of these statements is:

“IF I encounter situation X, THEN I will perform action Y!” Then, participants were instructed to make at least one or two implementation intentions to reduce food waste over the coming week in one of the following categories: (1) food acquisition (e.g., meal planning, grocery shopping), (2) food preparation (e.g., cooking, food storage), and (3) leftovers (e.g., using up leftovers, using leftovers in other meals). Participants were provided with examples for each (e.g., “IF I am going shopping, THEN I will make a shopping list beforehand.”). The full text of these instructions can be found in the online

Supplementary Materials S4.

One week after completing Survey 1, participants were sent a check-in message reminding them of the upcoming Survey 2 and also reminding them to keep track of their food waste. Participants who had set implementation intentions were reminded to enact their intentions.

Finally, two weeks following completion of Survey 1, participants were invited to Survey 2. Participants first completed the same food waste and food waste-related behavior measures in reference to the past week. Participants also completed a number of items regarding how they tracked food waste, their experiences with their implementation intentions, and demographic characteristics.

3.3. Study Design

The procedure described above resulted in a 2 (time: pre-vs. post-intervention) by 3 (informational condition: money vs. holistic vs. sitting) by 2 (behavioral condition: set intentions vs. did not set intentions) factorial design. The time factor was manipulated within participants, whereas the informational and behavioral conditions were manipulated between participants. Participants were randomly assigned to one of five study conditions, shown in

Table 2 below.

3.4. Data Analysis

Data was analyzed using R [

38]. The first step was to conduct bivariate mean differences to test whether there were significant changes in food waste amounts before and after the intervention across all conditions (i.e., Survey 1 vs. Survey 2). Analyses involved paired-sample

t-tests and calculation of Cohen’s

d effect sizes. The second step was to conduct multiple regression analyses to compare the effects of the money message versus the control message (Model 1), the holistic message versus the control message (Model 2), the money message versus the holistic message (Model 3), and the implementation intention-setting versus no intention-setting conditions (Model 4). All analyses controlled for pre-intervention levels of the four outcome variables in their respective analyses [

39]: food acquisition behaviors, date label wasting behavior, leftover usage behaviors, and food waste.

4. Results

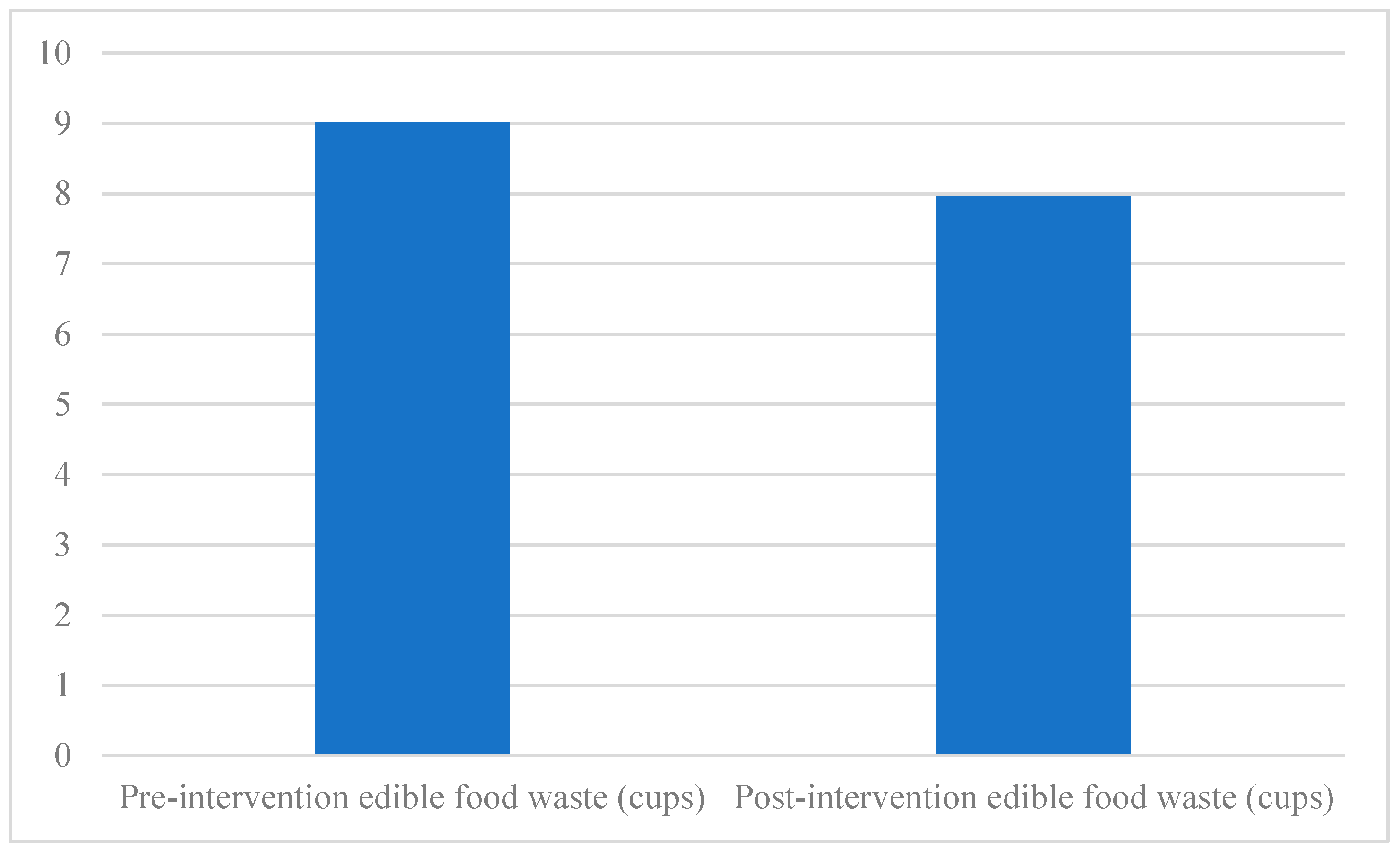

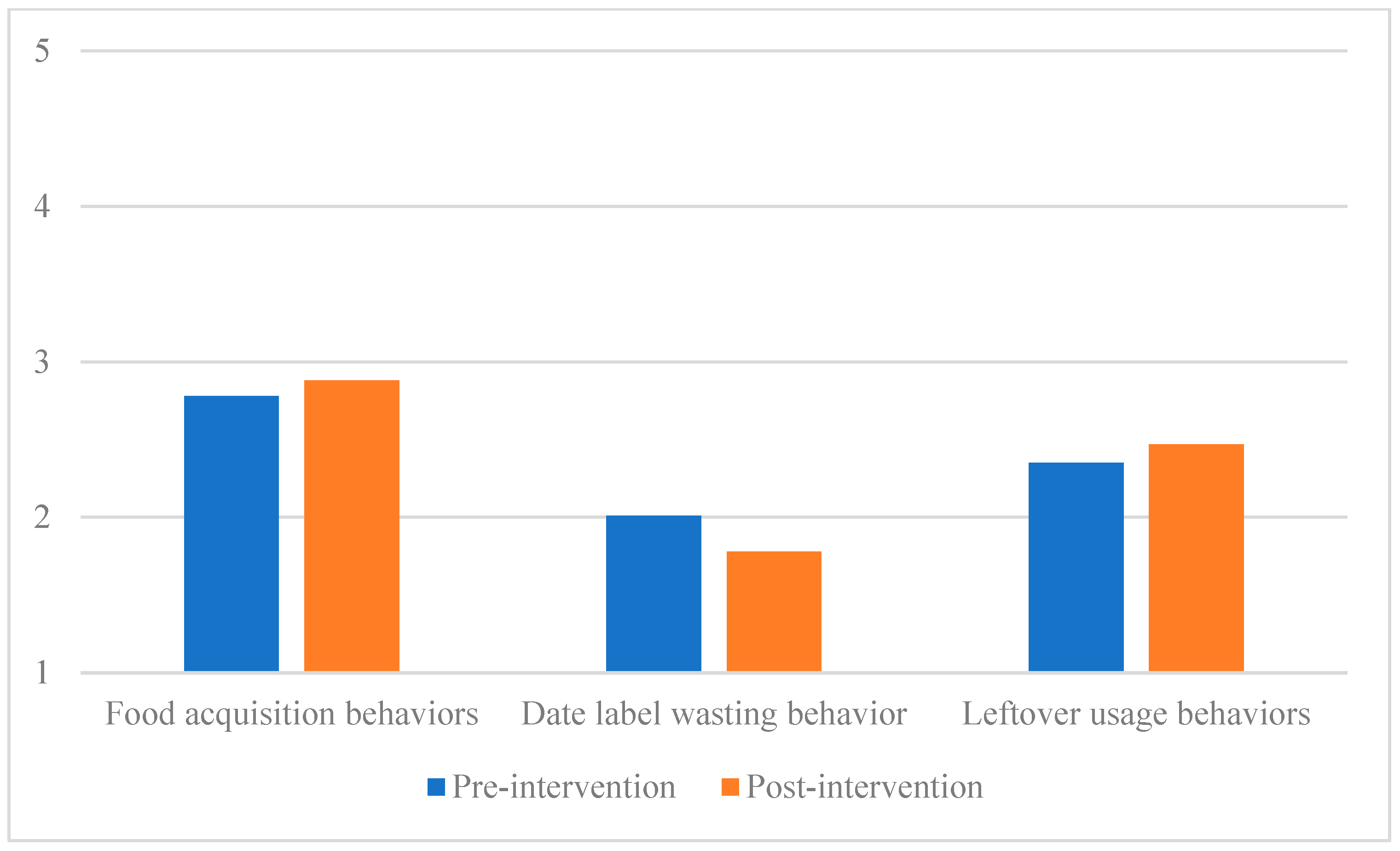

Descriptive statistics are shown for focal variables in

Table 3, and a visual of the mean differences in food waste and food behaviors is shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

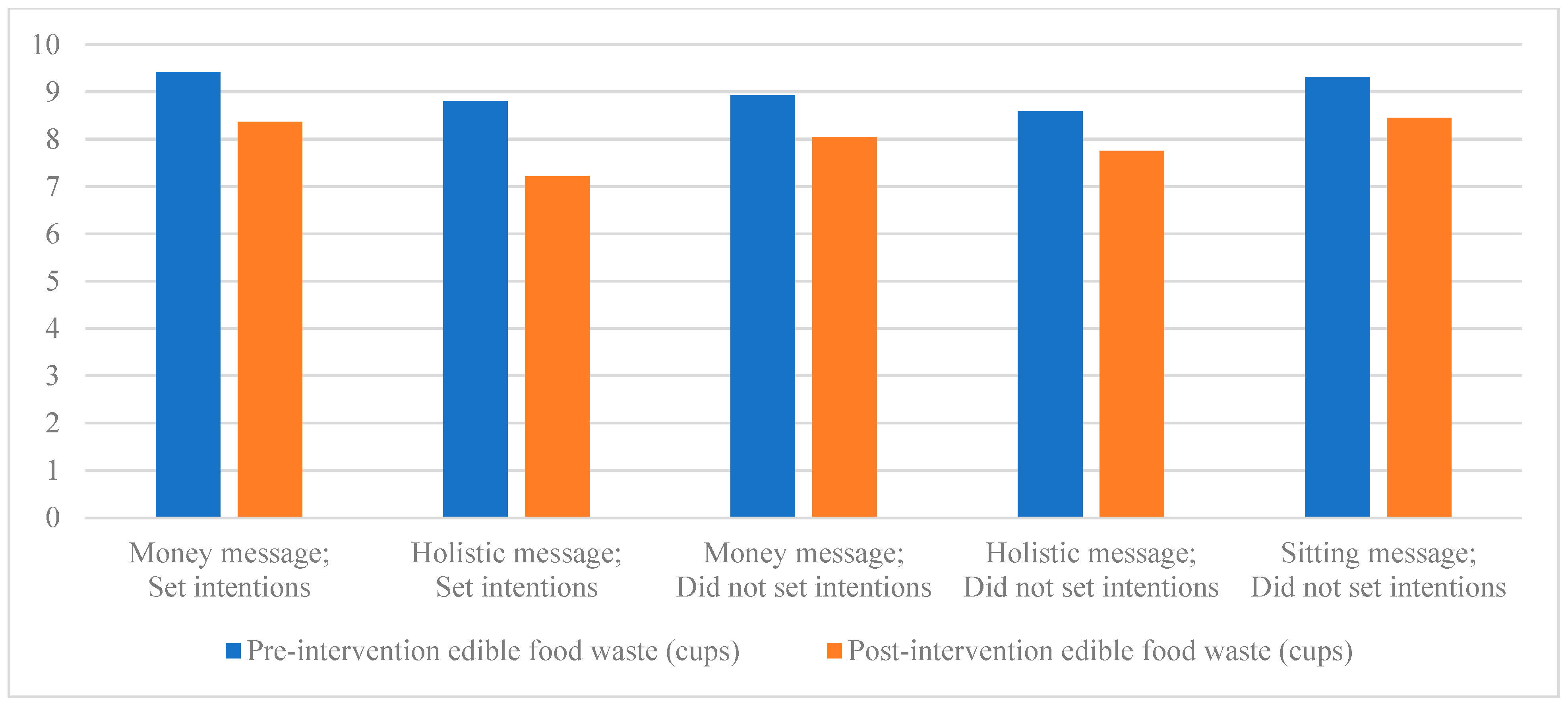

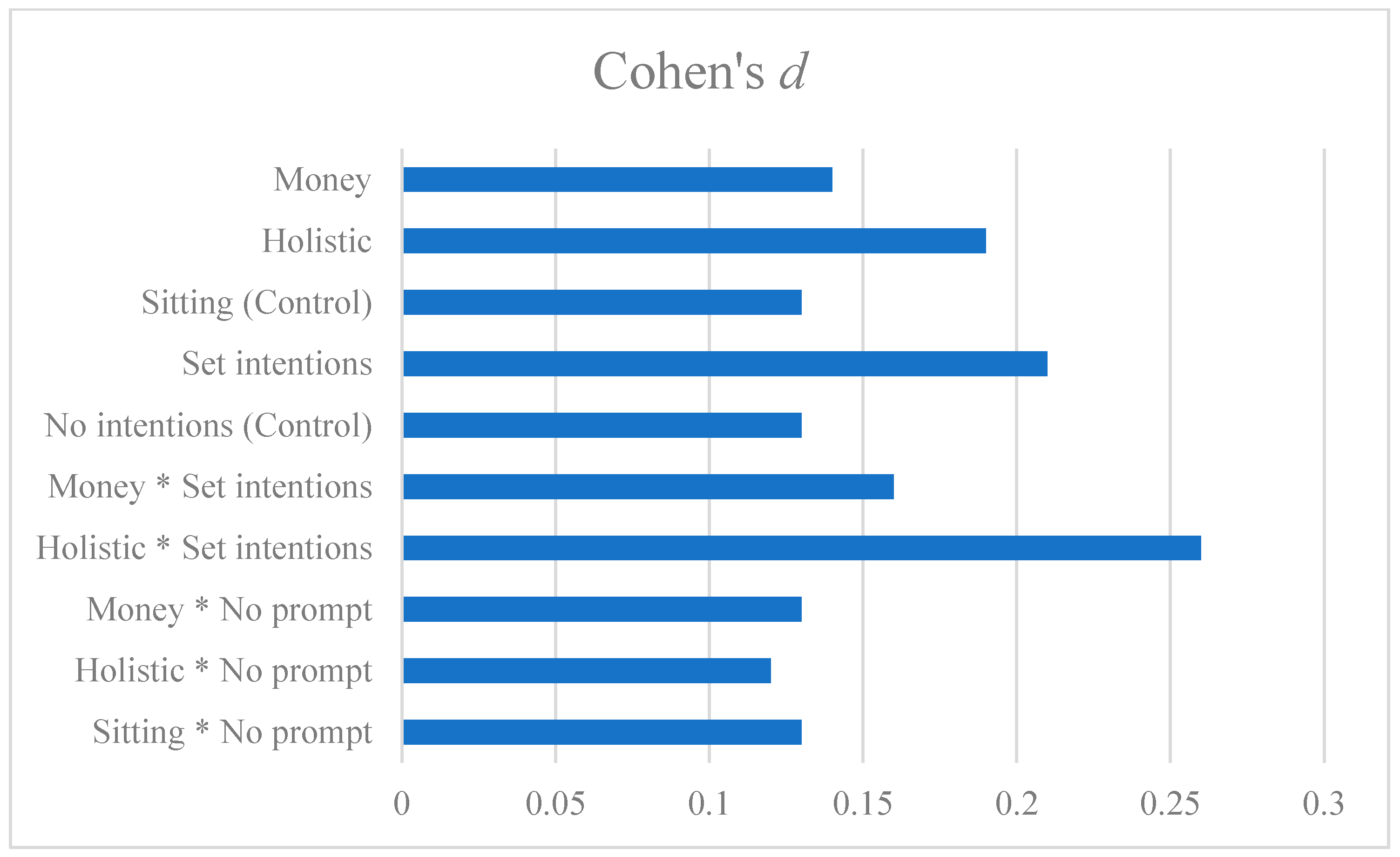

Prior to testing this study’s hypotheses and research question, we began by computing bivariate mean differences in food waste amounts across study conditions, as food waste reduction is the ultimate goal of these interventions. As can be seen in

Table 4 and

Figure 3, there was a significant reduction in post-intervention food waste across all study conditions. Furthermore, the largest effect sizes are associated with the combined condition where participants read the holistic message and then set implementation intentions (

d = 0.26), the implementation intention-setting condition (

d = 0.21), and the holistic message informational condition (

d = 0.19).

Figure 4 shows the distribution of these effect sizes for each condition, given that each is relatively small and may be more easily distinguished visually. Of note, there was a significant reduction in food waste in the control condition as well, which was comparable to the reductions in the message-only conditions with no prompts for implementation setting.

To test study hypotheses and research question, we conducted a series of multivariate tests using multiple linear regression for four separate outcomes: post-intervention food acquisition behaviors, date label wasting behavior, leftover usage behaviors, and food waste. In each model, we controlled for the pre-intervention level of each outcome. These results can be seen in

Table 5.

Beginning with Hypothesis 1a (Model 1 and Model 2 in

Table 5), we found that the “save money” message and the “holistic” message were associated with significant reductions in post-intervention date label wasting (relative to the control condition of the “reduce sitting” message), but otherwise neither message was associated with other post-intervention food waste reduction behaviors. Turning to Hypothesis 1b, neither message was associated with significant reductions in post-intervention food waste. Thus, Hypothesis 1a was partially supported, and Hypothesis 1b was not supported. Furthermore, in answer to Research Question 1, inspection of Model 3 results in

Table 5 reveals that there was no difference in effect on date label wasting between the money and holistic messages.

In summary, it appears that there may be some effects of messaging on a subset of food waste reduction behaviors, but purely informational approaches to behavior change may be limited in effectiveness. Moreover, although these messages were associated with significant reductions in the bivariate analysis (

Table 4), controlling for the effects of the pre-intervention level of the outcome may have washed out those effects in these analyses. Finally, we conducted a secondary analysis of Model 1 and Model 2 for post-intervention date label wasting including only individuals who did not set implementation intentions, and we found that the effects of the money message (vs. sitting;

B = −0.05,

SE = 0.08,

p = 0.56) and the holistic message (vs. sitting;

B = −0.09,

SE = 0.08,

p = 0.25) became non-significant. Therefore, messaging appears to have little practical utility as a food waste reduction effort.

Finally, turning to Hypothesis 2 and Model 4 results in

Table 5, we found that participants assigned to set implementation intentions demonstrated superior food waste reduction behaviors (i.e., higher food acquisition, less likely to waste food based on its date label, and higher leftover usage) relative to participants who did not set implementation intentions (i.e., information-only conditions). However, there was no significant difference in post-intervention food waste. Thus, Hypothesis 2a was supported, but Hypothesis 2b was not supported.

In summary, implementation intentions seemed to have enabled individuals to enact higher levels of behaviors that are associated with lower food waste, although there was no direct effect of the intentions on food waste itself. In an exploratory analysis, we tested whether post-intervention food waste reduction behaviors themselves predicted post-intervention food waste (while controlling for pre-intervention levels of all variables). We found that food acquisition behaviors were unrelated to food waste (B = −0.45, SE = 0.26, p = 0.08), but date label wasting behavior (B = 0.88, SE = 0.14, p < 0.001) and leftover usage behaviors (B = −1.78, SE = 0.27, p < 0.001) were significantly related to food waste. Therefore, the effect of the implementation intentions may be indirect, rather than direct, but this explanation is tentative and requires further exploration in future research. Messages alone, however, are clearly insufficient to promoting behavior change and furthering goals of food waste reduction in the household.

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to develop a consumer-facing food waste behavior change intervention that could be scaled up to a national food waste reduction campaign. To that end, using a two-time survey with pre- and post-intervention food waste and behavior measurements, we tested the effectiveness of a message-based, informational intervention approach and an action-based, behavioral intervention approach.

Our findings indicate that a message-based approach alone may have little practical utility as a food waste reduction tool. Relative to a control message unrelated to food waste, holistic and money-focused messages had significant impacts only on date label related behaviors, but not on food acquisition behaviors, leftover usage behaviors, or food waste itself. This is in line with Simões et al.’s [

40] assessment from a recent review paper: “But knowing the impacts is not as effective as knowing specific actions to reduce food waste, which suggests that information and awareness raising on the impacts of consumer food waste alone arenot enough to change consumer behavior” (p. 8). However, as noted by one reviewer, future research may test a stronger message-based approach by utilizing an in situ delivery method for the information, possibly relying on technological aids (e.g., mobile applications, reminders) that can ensure that the information is provided in a timely, relevant fashion [

17]. Additionally, as discussed by Castro et al. [

41], smartphone applications can provide a full suite of information within a person’s daily life, such as recipe ideas, sustainability information, and even a platform for sharing information and requests with other users. Thus, future research may consider testing this approach.

In contrast, an action-based approach involving setting implementation intentions did increase food waste reduction behaviors across food acquisition, leftover usage, and date label domains. While these effects on behavior did not translate into decreased food waste amounts relative to the control group, it is possible that such effects may take longer than one week to manifest. Indeed, Roe et al. [

9] tested a tailored food waste reduction intervention and similarly found promising results with regard to antecedent behaviors but a non-significant reduction in plate waste, which they attributed in part to the short duration of the intervention. Future studies examining intervention effects across longer durations with multiple measurement points are needed. Of note, this sample was more highly educated and thus not fully representative of national demographics, and so future studies may also test these interventions in samples of varying educational levels as well as levels that are nationally representative.

Interestingly, we observed small, statistically significant decreases in reported food waste between pre- and post-test across all participants, including those in the control group who did not receive food waste messages or set implementation intentions. Although the control group did not participate in the interventions, they did report their respective household food waste levels and behaviors during the pretest session. In line with the notion that “what gets measured gets managed,” it is possible that simply measuring food waste at pretest increased awareness and motivation to reduce food waste [

42]. It is also possible that the control group’s decrease in food waste was due to demand effects. Participants may have inferred the study’s focus was on food waste and responded with lower food waste levels at posttest in line with intuition of study aims. The finding of significant reductions in food waste amounts in the control group highlights the need for careful consideration of control group design in food waste intervention research. Simply observing pre- post decreases in food waste amounts in an intervention condition could be a measurement artifact, rather than an indication that the intervention itself caused the food waste change.

Future research investigating whether and how food waste measurement alone impacts behavior and waste outcomes is needed. The current study utilized self-report methods, which, though generally convergent with other methods [

34,

35], is likely to have produced an underestimate of actual food waste amounts and may have exerted a more obvious demand effect. Therefore, one possible approach to study measurement impacts includes having others report on a person’s food waste amounts, to reduce demand effects and biases that may motivate participants to report lower food waste at posttest. Another possible approach is to measure food waste amounts via curbside waste audits, rather than self-reported food waste. With this measurement approach, researchers collect, sort, and weigh food waste components of household trash streams, providing an objective estimate of food waste over time [

43]. If future studies with such methods find that measuring food waste itself is a viable, effective food waste reduction intervention, behavior change campaigns could consider implementing measurements with feedback (e.g., via trend line charts) as a potential tool to change behavior.

An additional direction for future research is to test for whom either informational or behavioral intervention approaches are more or less effective. As raised by one reviewer, demographics can influence outcomes, and in the current study we conducted an exploratory analysis of results by education level, income, and household size. Specifically, for participants who were assigned to set implementation intentions, we examined correlations between change in food waste pre-/post-intervention and education, income, and household size. We found only weak relationships: education was unrelated to change in food waste (r = −0.04, p = 0.36), income was negatively related to change in food waste (r = −0.09, p = 0.04), and household size was unrelated to change in food waste (r = −0.06, p = 0.14). Thus, it may be that behavioral approaches are slightly more effective for households with higher income levels, but future research may continue to explore this and other moderating demographic and lifestyle variables.

Finally, future research may consider testing alternative control conditions. Specifically, as raised by one reviewer, it is possible that the various intervention conditions were not matched in intensity and thus may have exerted a demand effect. We would suggest that asking participants to set implementation intentions to reduce their sitting behavior (as a control) is similar in strength to asking participants to set implementation intentions to reduce their food waste (as a treatment), in that both require participants to take steps to change aspects of their daily lifestyle. Indeed, past research has found that implementation intentions are effective for increasing physical activity [

44], meaning that this is a relatively like-for-like comparison. However, future research should test alternative control conditions to determine whether different results may appear.