Sustainable Accounting Under EU Sustainability Regulations: Comparative Evidence from Romania and European Case Studies on CSRD Implementation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Evolution of Sustainability Accounting

2.2. The Emergence of the CSRD and ESRS Frameworks

2.3. Empirical Evidence Across EU Member States: A Comparative Synthesis

| Author (Year) | Country/Region | Methodology | Key Indicators/Variables | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hummel (2024) [20] | European Union | Conceptual and legal analysis | CSRD legal framework, ESRS, EU Taxonomy | Highlights the transition from voluntary to mandatory sustainability reporting and the harmonization of EU standards. |

| Pantazi (2024) [19] | EU (legal perspective) | Doctrinal/comparative study | Legal requirements, disclosure obligations, and corporate transparency | Demonstrates the legal impact of CSRD, emphasizing accountability and compliance across EU firms. |

| Kosi & Relard (2024) [23] | Germany | Empirical survey | CSRD readiness, IT infrastructure, ESG competencies | Only 42% of firms report full preparedness; significant gaps in digitalization and ESG training. |

| Ebner (2024) [26] | Germany | Multiple-case study | Reporting practices, accountants’ roles, internal processes | Family-owned firms treat CSRD as a compliance exercise rather than a strategic initiative. |

| Krasodomska et al. (2024) [3] | Poland | Cross-sectional survey | Accountants’ perceptions, institutional and personal factors | Moderate acceptance of CSRD; barriers include lack of training and high implementation costs. |

| Raimo (2025) [24] | Europe (multinational sample) | Content analysis | Quality of integrated reports, alignment with ESRS and GRI | ESG reporting quality varies widely; many firms fail to meet comparability and transparency criteria. |

| Mangiuc et al. (2025) [21] | EU (conceptual) | Theoretical study | CSRD paradigm, sustainability accounting roles | Defines CSRD as a paradigm shift requiring new competencies and integrated accountability. |

| Lammers (2025) [25] | Netherlands | Multiple-case study | CSRD preparation processes, ESG governance, internal reporting | Identifies weak integration between financial and sustainability information systems. |

| Christensen (2024) [28] | Global | Theoretical analysis | Sustainability accounting, climate-risk management | Argues that accounting is evolving into a strategic instrument for managing climate-related risks. |

| Romé (2024) [27] | Sweden | Single-case study | CSRD implementation processes, resource allocation | Larger firms are more advanced; SMEs face difficulties in collecting and verifying ESG data. |

| Bulgaria—CSRD Readiness Assessment (2025) [29] | Bulgaria | Mixed methods (survey + interviews) | Readiness level, institutional barriers, and accountants’ perception | Low overall readiness; main barriers are a lack of local ESRS guidance and a weak IT infrastructure. |

| Shipbuilding Network Study (2025) [6] | EU (industrial network) | Case study | Value-chain reporting, sectoral ESG indicators | Shows that CSRD fosters collaborative ESG data reporting across industrial partners. |

| Integrated Reporting and CSRD (2025) [30] | Europe | Content analysis | Correlation between financial and non-financial indicators | Demonstrates convergence between integrated reporting and CSRD; emphasizes the need for accountant training. |

| Accounting for Sustainability: The New CSRD (2024) [17] | Global (EU-focused) | Conceptual/normative analysis | ESRS implementation, implications for the accounting profession | Stresses the need to redefine accounting competencies and adopt digital ESG tools. |

2.4. Derivation of Research Hypotheses

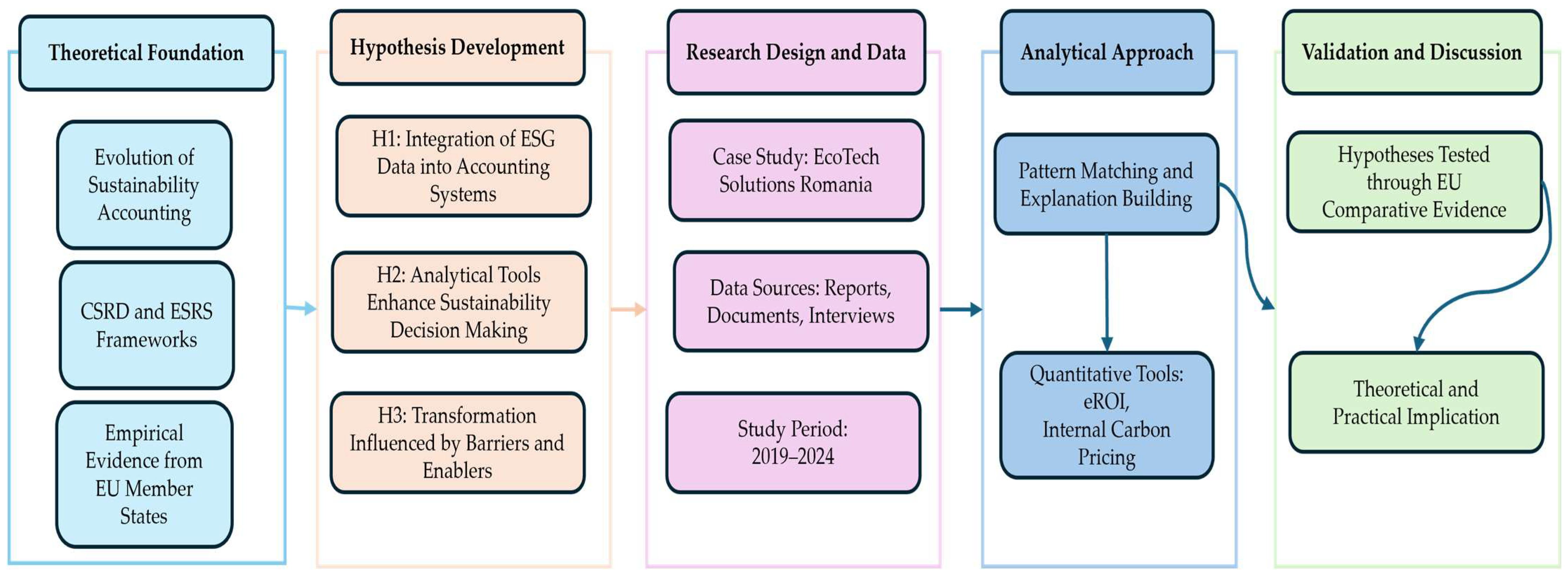

3. Methodology

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Transformation of the Accounting Function

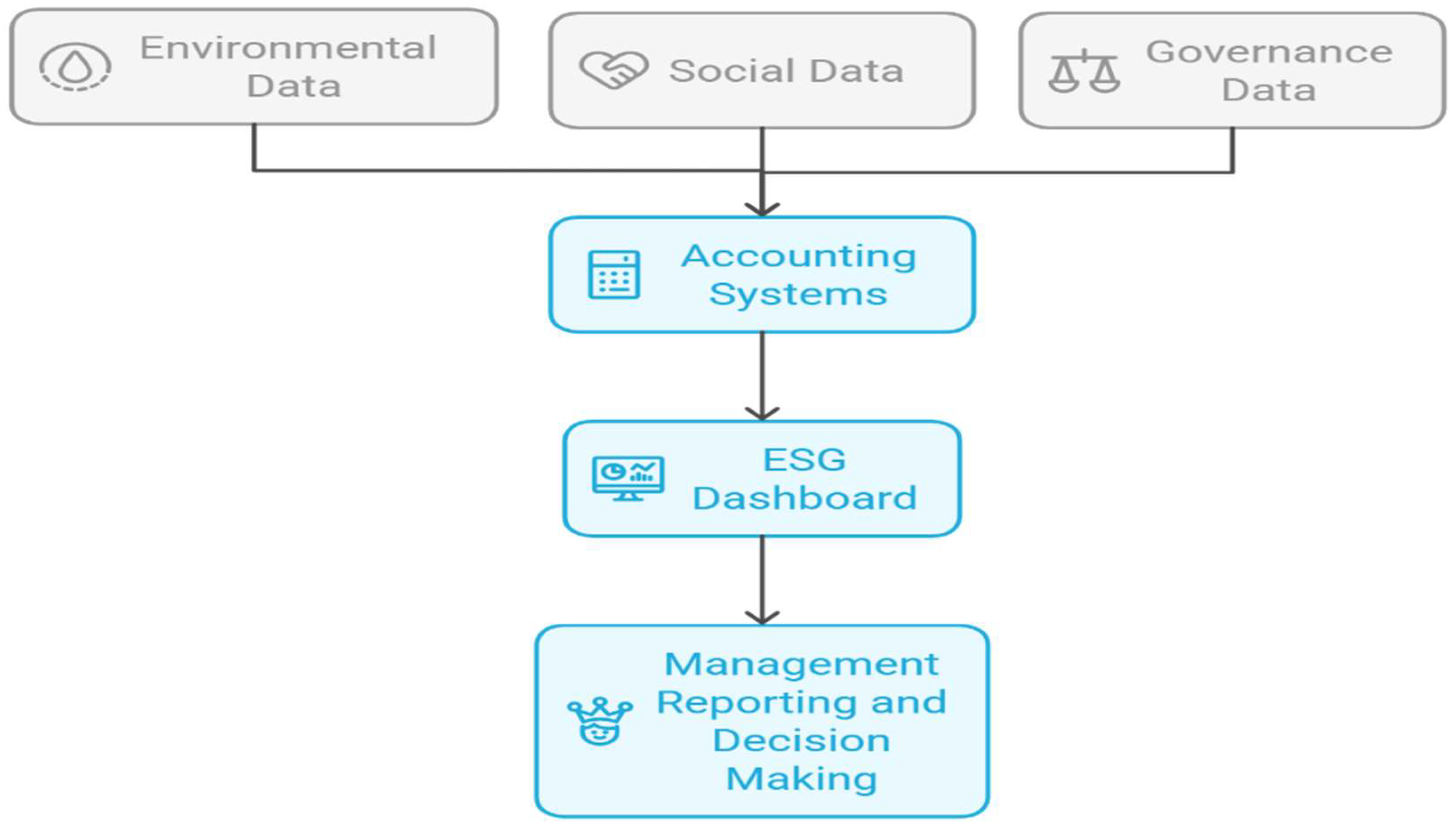

4.2. ESG Data Integration and Reporting Practices

4.3. Accountants’ Role and Skills in the CSRD Context

4.4. Barriers and Enablers Across the EU

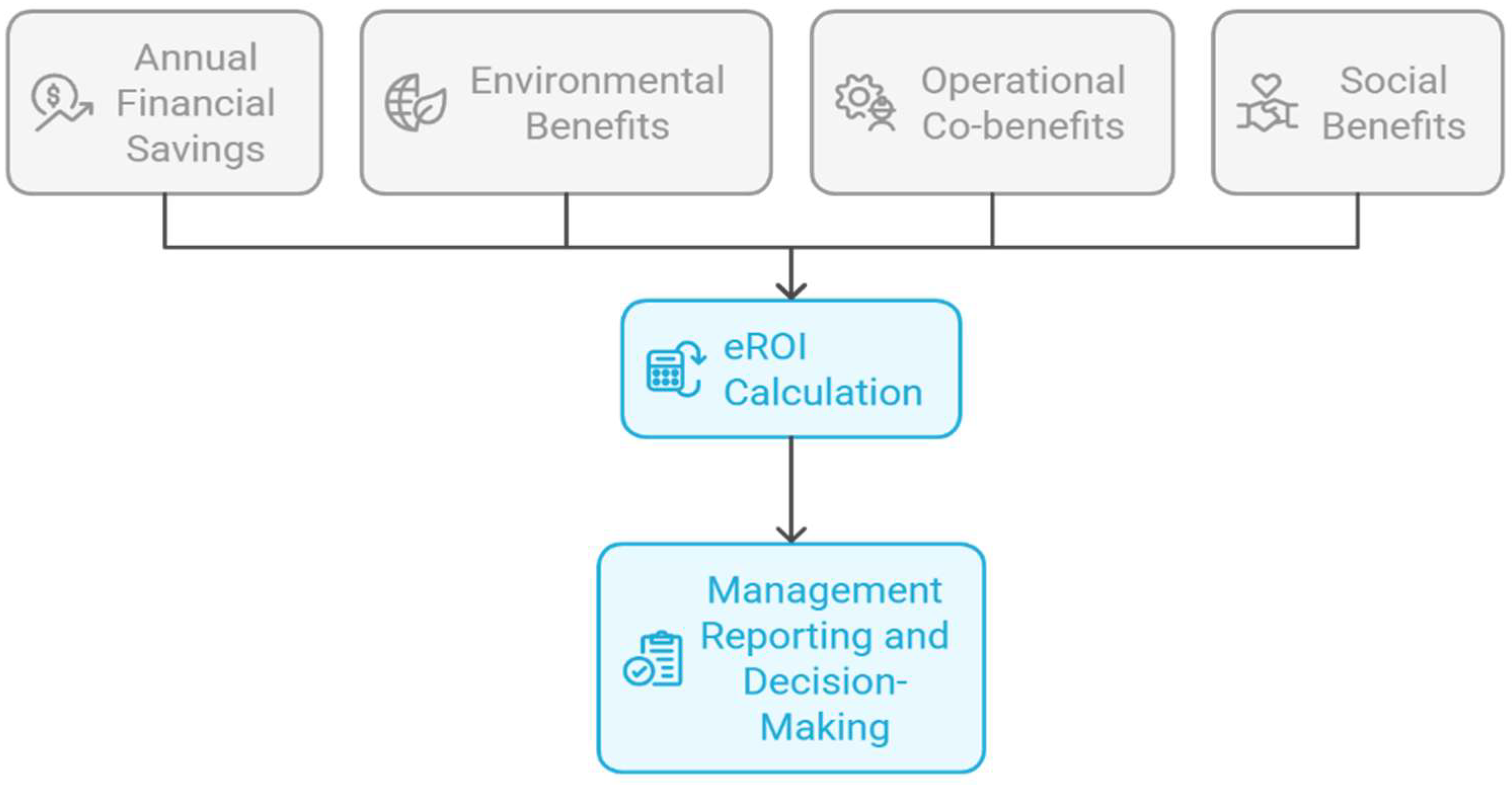

4.5. Extended ROI and Internal Carbon Pricing (Comparative Insight)

4.6. Interpreting the Results in a Comparative Context

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Comparative Insights Across the EU

5.3. Practical Implications and Transferability

5.4. Policy Implications

5.5. Limitations and Future Research

5.6. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Extended ROI (eROI) Model Structure

Appendix A.1. Conceptual Structure of the Extended ROI Model

Appendix A.2. Components of the eROI Mode

Appendix A.2.1. Financial Savings

Appendix A.2.2. Environmental Benefits

Appendix A.2.3. Operational Co-Benefits

Appendix A.2.4. Social Benefits

Appendix A.2.5. Confidentiality Note

Appendix A.2.6. Data Sources and Key Assumptions

Appendix A.3. Example of Extended ROI Calculation (Generic Illustration)

- Calculate financial savings based on reductions in annual electricity or heating use.

- Monetize environmental benefits by applying the internal carbon price to annual emission reductions.

- Estimate operational co-benefits, including reduced maintenance costs and productivity gains.

- Apply the eROI formula, integrating all components relative to initial investment costs.

Appendix A.4. Alignment with International Guidelines

References

- Kalbouneh, A.; Aburisheh, K.; Shaheen, L.; Aldabbas, Q. The Intellectual Structure of Sustainability Accounting in the Corporate Environment: A Literature Review. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2211370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD); L322/15; Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgum, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Krasodomska, J.; Zarzycka, E.; Zieniuk, P. Exploring Multi-Level Drivers of Accountants’ Opinions on the Changes Introduced by the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive. Account. Eur. 2024, 22, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrescu, A.G.; Bîlcan, F.R.; Petrescu, M.; Holban Oncioiu, I.; Türkeș, M.C.; Căpușneanu, S. Assessing the Benefits of the Sustainability Reporting Practices in the Top Romanian Companies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, V.F.; Chersan, I.C.; Gorgan, C. Early Disclosure of the Double Materiality Concept in a European Oil and Gas Company. In Proceedings of the 9th BASIQ International Conference on New Trends in Sustainable Business and Consumption, Oradea, Romania, 26–28 June 2025; ASE Publishing: Bucharest, Romania, 2023; pp. 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tănase, L.C.; Radu, V.; Tăbîrcă, A.I.; State, V.; Radu, F.; Marcu, L.; Voinea, C.M. Measuring CSR with Accounting Information Systems Through a Managerial Model for Sustainable Economic Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A.; Larrinaga, C. Progress: Engaging with the Challenges of Developing Sustainability Accounting and Accountability. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2019, 32, 2367–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che Kasim, C.F.; Yusoff, H.; Mohd Fahmi, F. Accountants’ Roles in Sustainability Accounting and Reporting: The Preliminary Findings. Corp. Gov. Organ. Behav. Rev. 2024, 8, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Romania’s Recovery and Resilience Plan; European Commission: Brussels, Belgum, 2021.

- Petricică, A.E. The Role of Accountants and the Accounting Profession in Achieving Sustainable Development. Proc. Int. Conf. Bus. Excell. 2023, 17, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramesti, A.A.; Novita, F. Hwihanus. The Role of Green Accounting in Promoting a Green Economy: Integrating Environmental Considerations into Financial Systems for Sustainable Development. JIMU J. Ilm. Multidiscip. 2024, 2, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherai, D.S.; Sabău Popa, D.C.; Rus, L.; Matica, D.E.; Mare, C. The Impact of Romanian Internal Auditors in ESG Reporting and Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, B.; Unerman, J. Fostering Rigour in Sustainability Accounting Research. Account. Organ. Soc. 2016, 49, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R. Is Accounting for Sustainability Actually Accounting for Sustainability … and How Would We Know? Account. Organ. Soc. 2010, 35, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, A.G. Accounting and the Environment. Account. Organ. Soc. 2009, 34, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). Professional Accountants in Business: A Framework for ESG Competency; IFAC: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.ifac.org/news-events/2022-08/companies-investors-and-professional-accountants-add-their-voices-call-global-alignment-between (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Sakiewicz, P.; Ober, J.; Kopiec, M. Challenges and Opportunities for CSRD Adoption in Poland. Technol. Organ. Manag. Ser. 2024, 214, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Burritt, R. Contemporary Environmental Accounting: Issues, Concepts and Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantazi, T. The Introduction of Mandatory Corporate Sustainability Reporting in the EU and the Question of Enforcement. Eur. Bus. Organ. Law Rev. 2024, 25, 509–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, K.; Jobst, D. An Overview of Corporate Sustainability Reporting Legislation in the European Union. Account. Eur. 2024, 21, 320–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangiuc, D.-M.; Kagitci, M. CSRD as a Paradigm Shift in Sustainability Reporting: From Voluntary Practice to Legal Requirement. Amfiteatru Econ. 2025, 27, 1193–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, C.A.; McNicholas, P. Making a Difference: Sustainability Reporting, Accountability and Organisational Change. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2007, 20, 382–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosi, U.; Relard, S. Are Firms Ready for the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive? Bus. Res. 2024, 17, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimo, N.; L’Abate, V.; Sica, D.; Vitolla, F. Integrated Reporting and the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive: Bridging the Gap or Growing Apart? Manag. Decis. 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammers, R. Adapting to the CSRD: A Multiple Case Study on How Companies Are Preparing. Master’s Thesis, Wageningen University and Research, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2025. Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/689537 (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Ebner, R. Multiple Case Study Analysis on the Consequences of Mandatory Sustainability Reporting in Private German Family Firms. Jr. Manag. Sci. 2024, 9, 1540–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romé, M.; Renz, J. Driving Sustainability through Regulation: A Case Study of CSRD Implementation in Companies. Master’s Thesis, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden, 2024. Available online: https://hj.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1864124/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Christensen, H.; Hales, J.; O’Dwyer, B.; Peecher, M.E. Accounting for Sustainability and Climate Change: Special Section Overview. Account. Organ. Soc. 2024, 113, 101568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolev, D.; Dikova, V. Corporate Sustainability Reporting in Bulgaria: Challenges and Opportunities. Econstor Work. Pap. 2025, 1937764230. [Google Scholar]

- Rep Romić, A.; Remlein, M.; Venturelli, A.; Pizzi, S. Assessment of the Readiness for the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). In The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD): A Practitioner’s Guide; Routledge: London, UK, 2025; Chapter 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). Final Report: Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures; Financial Stability Board: Basel, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2020/10/FINAL-2017-TCFD-Report-11052018.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Stiglitz, J.E.; Stern, N.; Duan, M.; Edenhofer, O.; Giraud, G.; Heal, G.M.; Winkler, H. Report of the High-Level Commission on Carbon Prices; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSRD Implementation in Bulgaria. CSRD-Directive.eu. 2024. Available online: https://csrd-directive.eu/csrd-harmonization-europe/csrd-implementation-bulgaria/ (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Macuda, M.; Kobiela-Pionnier, A. The Double Materiality Concept in Polish Listed Companies. Zesz. Teoretyczne Rachun. 2025, 49, 63–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albu, N.; Albu, C.N.; Filip, A. Corporate Reporting in Central and Eastern Europe: Issues, Challenges and Research Opportunities. Account. Eur. 2017, 14, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O. Sustainability Reports as Simulacra? A Counter-Account of A and A+ GRI Reports. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2013, 26, 1036–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakour, A.; Alaodat, H.; Alghazawi, A.; Al-Qaisi, E. The Role of Environmental Accounting in Sustainable Development: An Empirical Study. J. Appl. Econ. 2018, 8, 71–87. [Google Scholar]

| Indicator | Value (2024) | Change 2020–2024 |

|---|---|---|

| Turnover | EUR 42 million | +127% |

| Employees | 280 | +75% |

| EBITDA | EUR 8.4 million | +112% |

| Export markets | 7 EU countries | +4 |

| Emission intensity | 18.6 tCO2e/million EUR | −32% |

| % revenues from green products | 78% | +23pp |

| R&D investment | EUR 3.8 million | +146% |

| Subdivision | Specialists | % Time on Sustainability | Main ESG Roles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Accounting | 5 | 25% | ESG disclosure integration |

| Controlling and Reporting | 4 | 40% | ESG KPI monitoring |

| Taxation | 2 | 15% | Green tax incentives |

| Sustainability Accounting | 4 | 100% | Carbon accounting, CSRD/GRI reporting |

| Treasury | 2 | 10% | ESG risk management, green financing |

| Accounting Process | Pre-Transformation | Post-Transformation | Improvement Indicators | Implementation Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly closing | Exclusively financial | Integrated with ESG KPIs | Time reduction: 18% | Data reconciliation from diverse sources |

| Budgeting | Center-based | Activity-based + Impact | Accuracy +24% | Quantification of non-financial variables |

| Cost allocation | Traditional criteria | Includes ESG factors | Transparency +35% | Complex allocation methodologies |

| Asset management | Historical cost | Total cost of ownership + impact | ROI calculated +12% | Evaluation of externalities |

| Category | Romanian Case (EcoTech) | Comparable Findings in EU Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Data Quality | Inconsistent, fragmented | Similar in Bulgaria and Poland |

| IT Infrastructure | Limited ERP integration | Advances in Germany and Italy |

| Skills and Training | Partial, CFO-led | Stronger in Italy and the Netherlands |

| Leadership | Strong CFO commitment | Common success factor across the EU |

| Cross-functional collaboration | Established ESG committee | Similar trend in Germany and the Netherlands |

| Project | Investment (EUR) | Annual Financial Savings (EUR) | Classic Payback (Years) | Emission Reduction (tCO2e/Year) | Monetized Benefits (EUR/Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photovoltaic park | 380,000 | 82,000 | 4.6 | 185 | 27,750 |

| BMS modernization | 165,000 | 42,000 | 3.9 | 76 | 11,400 |

| Heat recovery | 120,000 | 28,000 | 4.3 | 62 | 9300 |

| LED + sensors | 85,000 | 32,000 | 2.7 | 48 | 7200 |

| Cogeneration | 420,000 | 76,000 | 5.5 | 124 | 18,600 |

| Thermal insulation | 140,000 | 38,000 | 3.7 | 84 | 12,600 |

| Total | 1,310,000 | 298,000 | 4.4 | 579 | 86,850 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petronela Alice, G.; Andreea Nicoleta, L.; Florinel, G.; Dan Marius, C.; Radu, V. Sustainable Accounting Under EU Sustainability Regulations: Comparative Evidence from Romania and European Case Studies on CSRD Implementation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10746. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310746

Petronela Alice G, Andreea Nicoleta L, Florinel G, Dan Marius C, Radu V. Sustainable Accounting Under EU Sustainability Regulations: Comparative Evidence from Romania and European Case Studies on CSRD Implementation. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10746. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310746

Chicago/Turabian StylePetronela Alice, Grigorescu, Liță Andreea Nicoleta, Gălețeanu Florinel, Coman Dan Marius, and Valentin Radu. 2025. "Sustainable Accounting Under EU Sustainability Regulations: Comparative Evidence from Romania and European Case Studies on CSRD Implementation" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10746. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310746

APA StylePetronela Alice, G., Andreea Nicoleta, L., Florinel, G., Dan Marius, C., & Radu, V. (2025). Sustainable Accounting Under EU Sustainability Regulations: Comparative Evidence from Romania and European Case Studies on CSRD Implementation. Sustainability, 17(23), 10746. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310746