Community Perceptions of Ecosystem Services from Homegarden-Based Urban Agriculture in Bandung City, Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Study Locations

- “How do you perceive the role of homegardens in improving food security within your community?”

- “What are the challenges you face in managing your homegarden, and how do you overcome them?”

- “In your opinion, how does urban agriculture contribute to environmental sustainability in your area?”

- “Can you describe how your community benefits from homegardens in terms of social cohesion and cultural practices?”

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Limitations of the Study

3. Results and Discussion

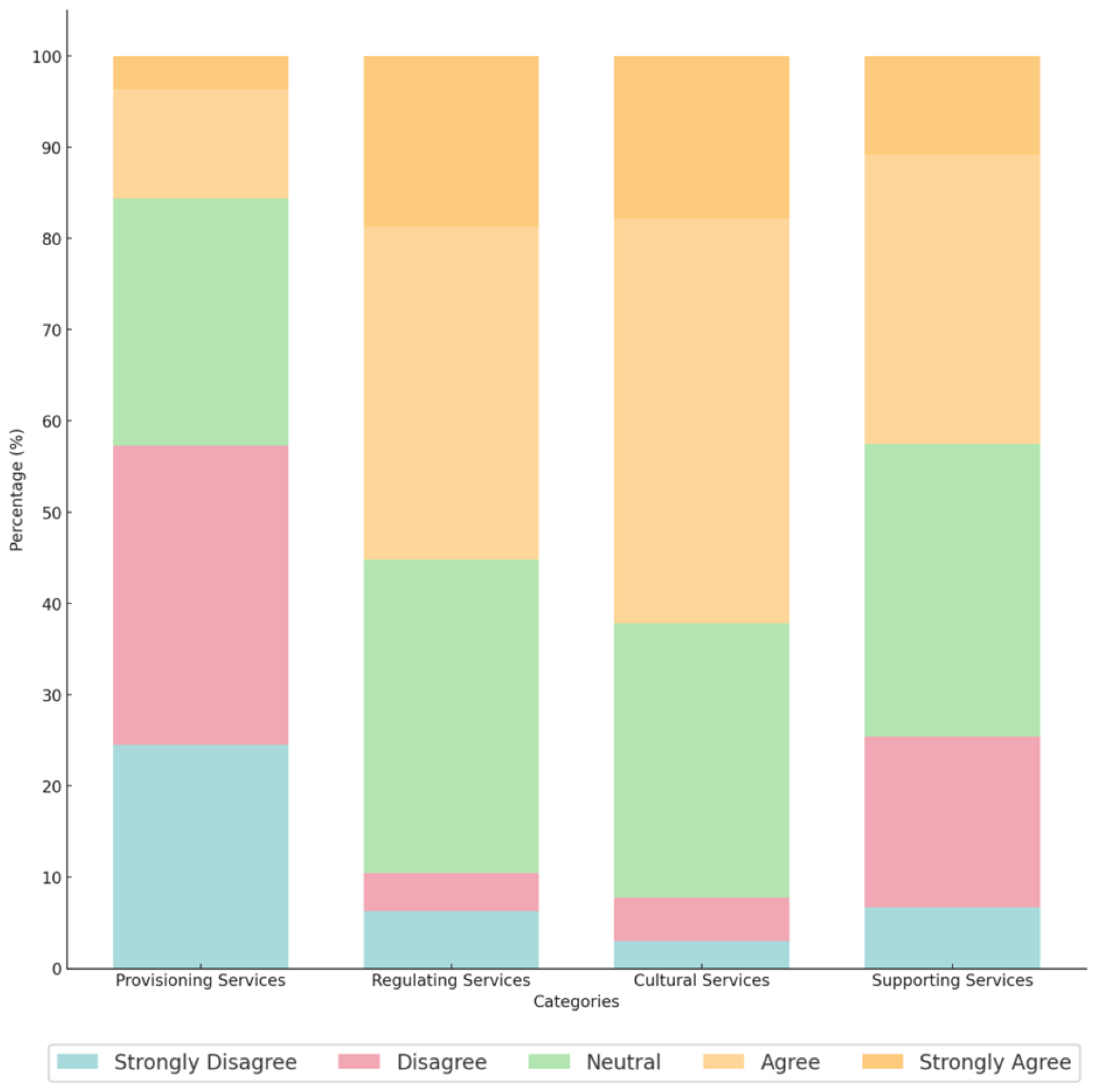

3.1. Provisioning Services

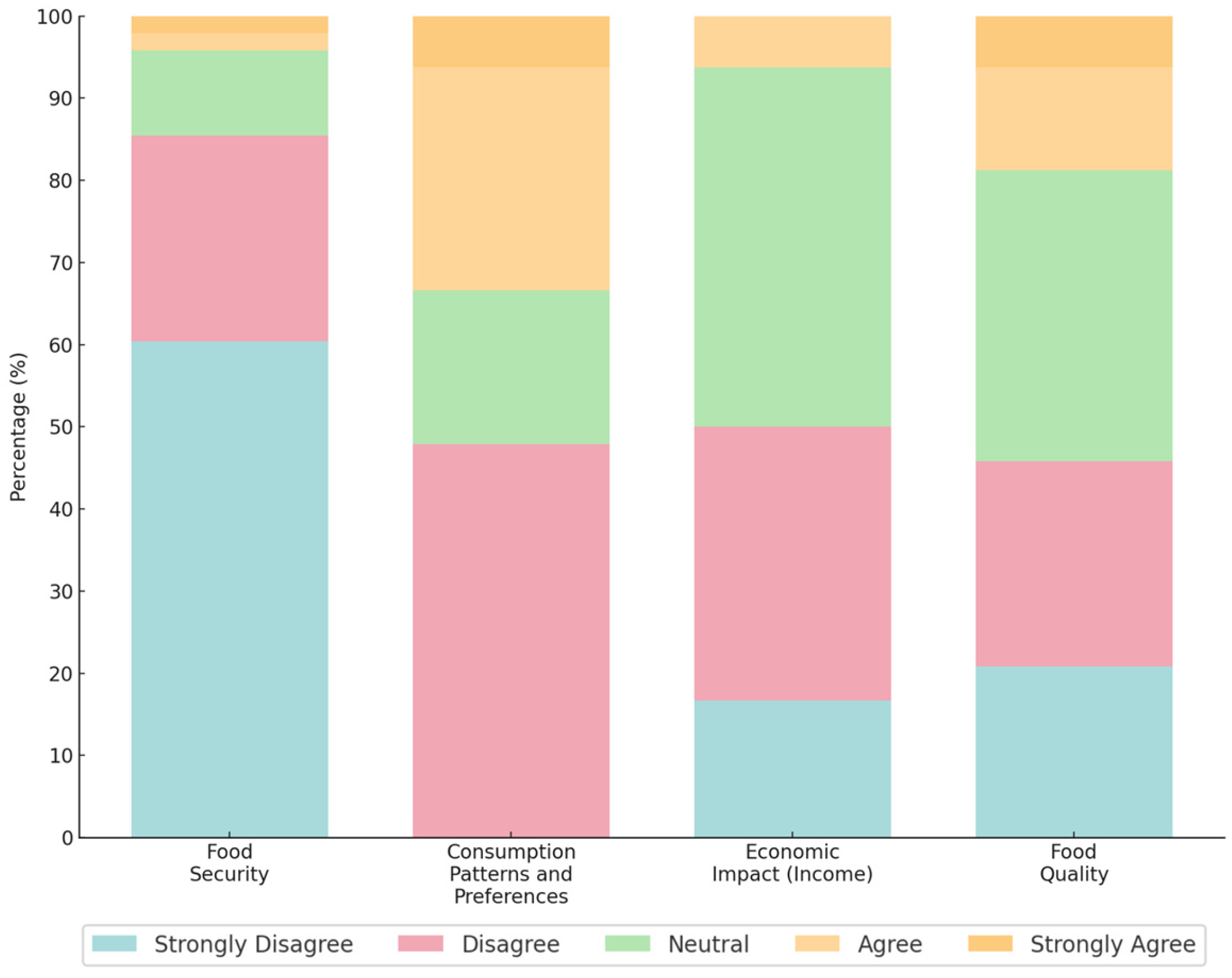

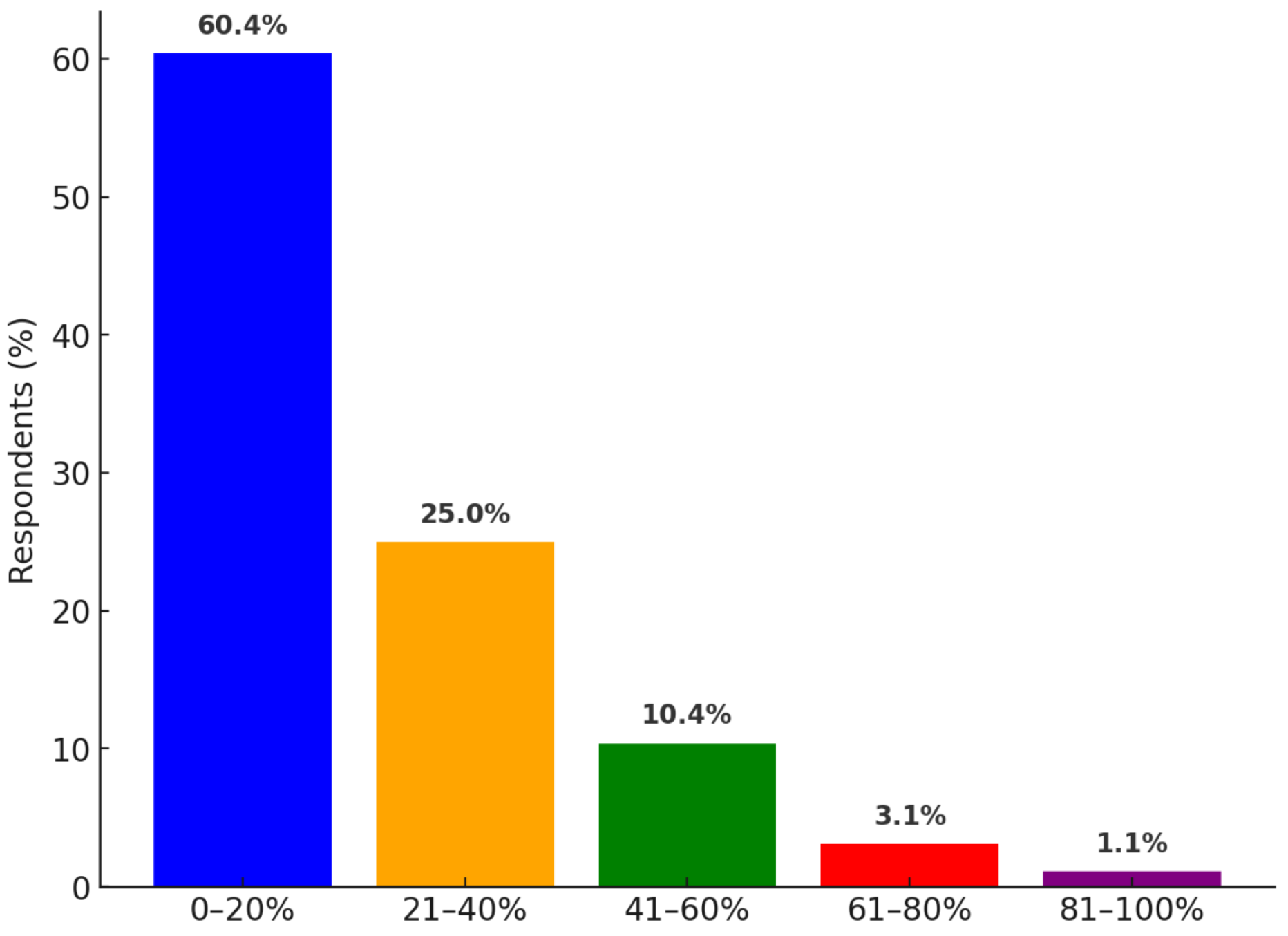

3.1.1. Perception of Food Security

3.1.2. Perception of Food Quality

3.1.3. Perception of Consumption Patterns and Preferences

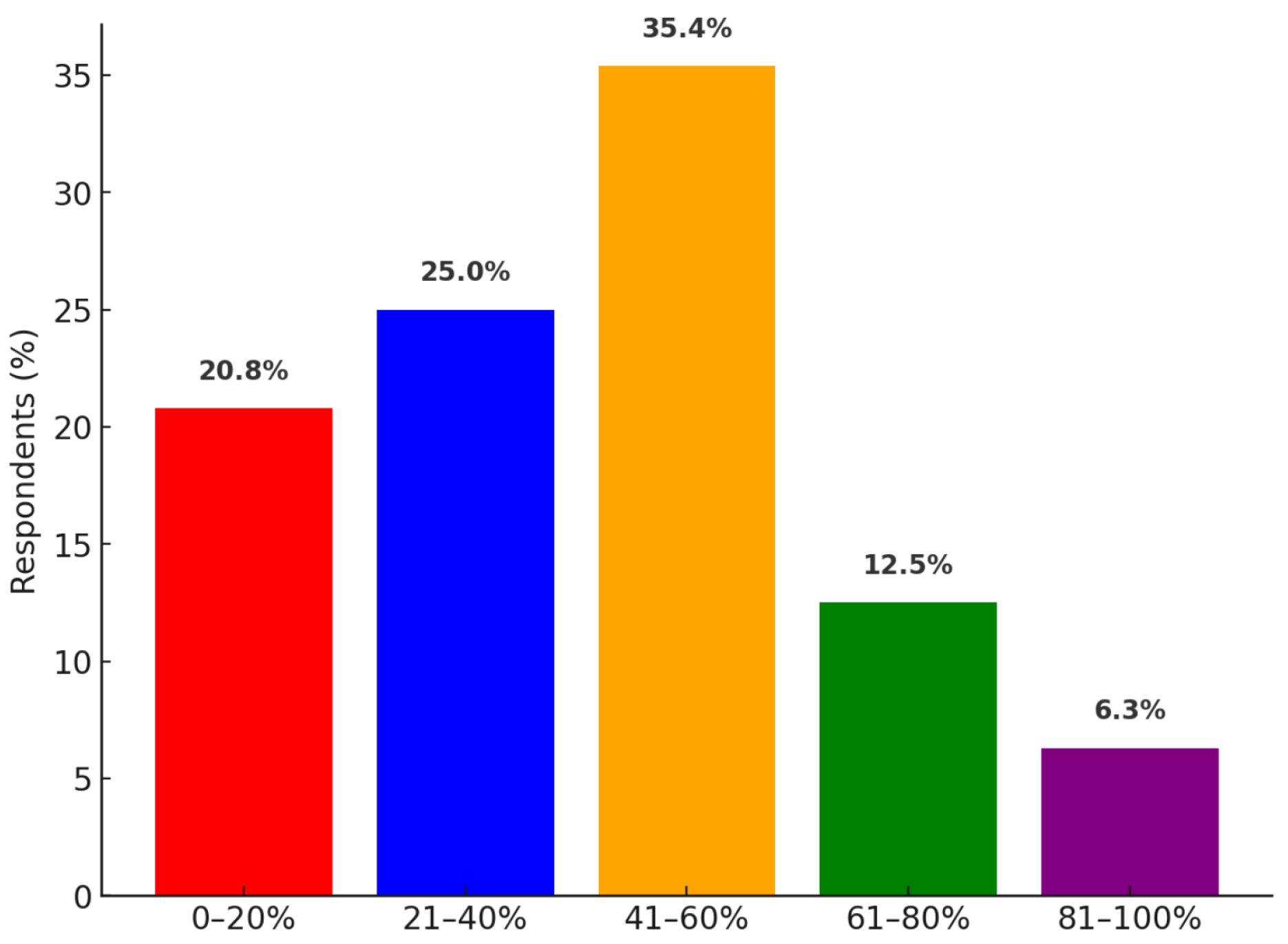

3.1.4. Perception of Economic Impact (Income)

3.2. Regulating Services

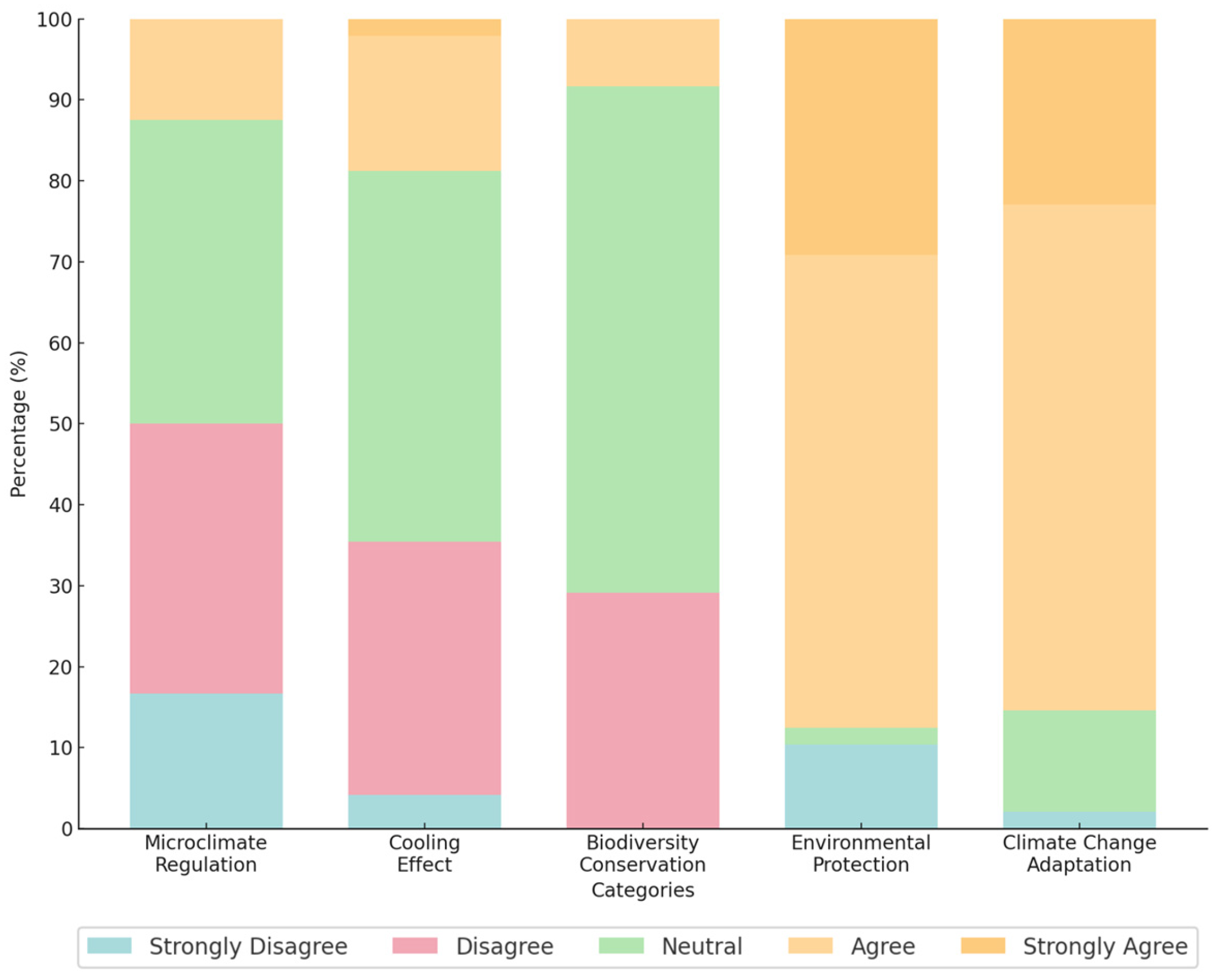

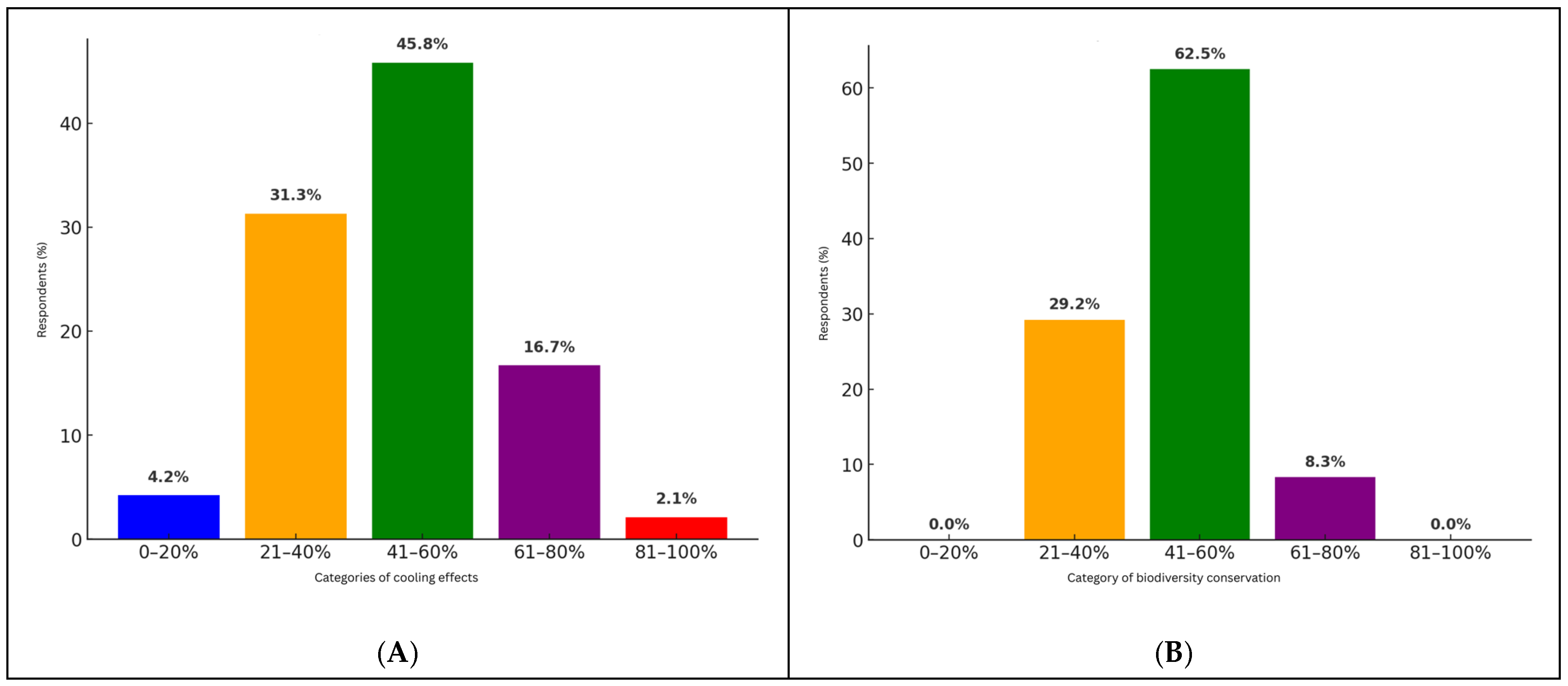

3.2.1. Perception of Microclimate Regulation and Cooling Effects

3.2.2. Perception of Biodiversity Conservation

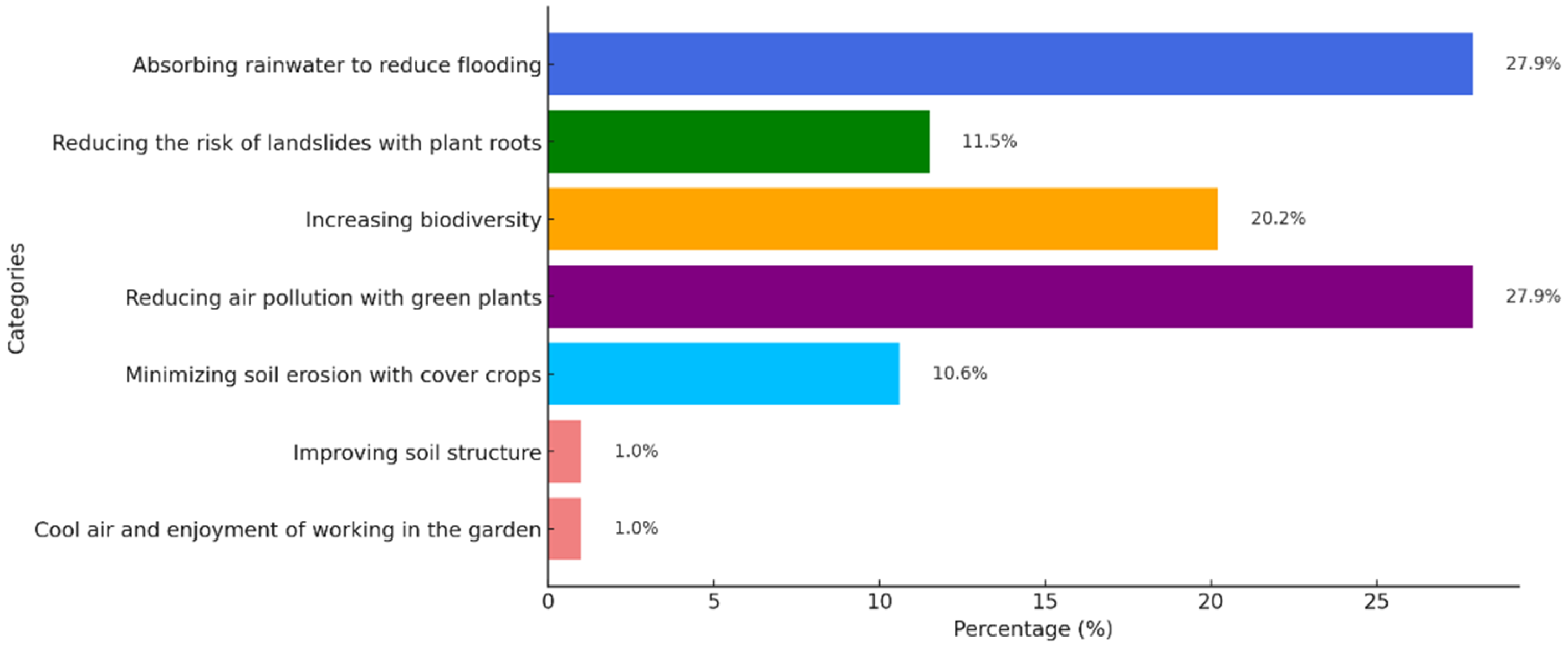

3.2.3. Perception of Disaster Risk Mitigation and Climate Change Adaptation

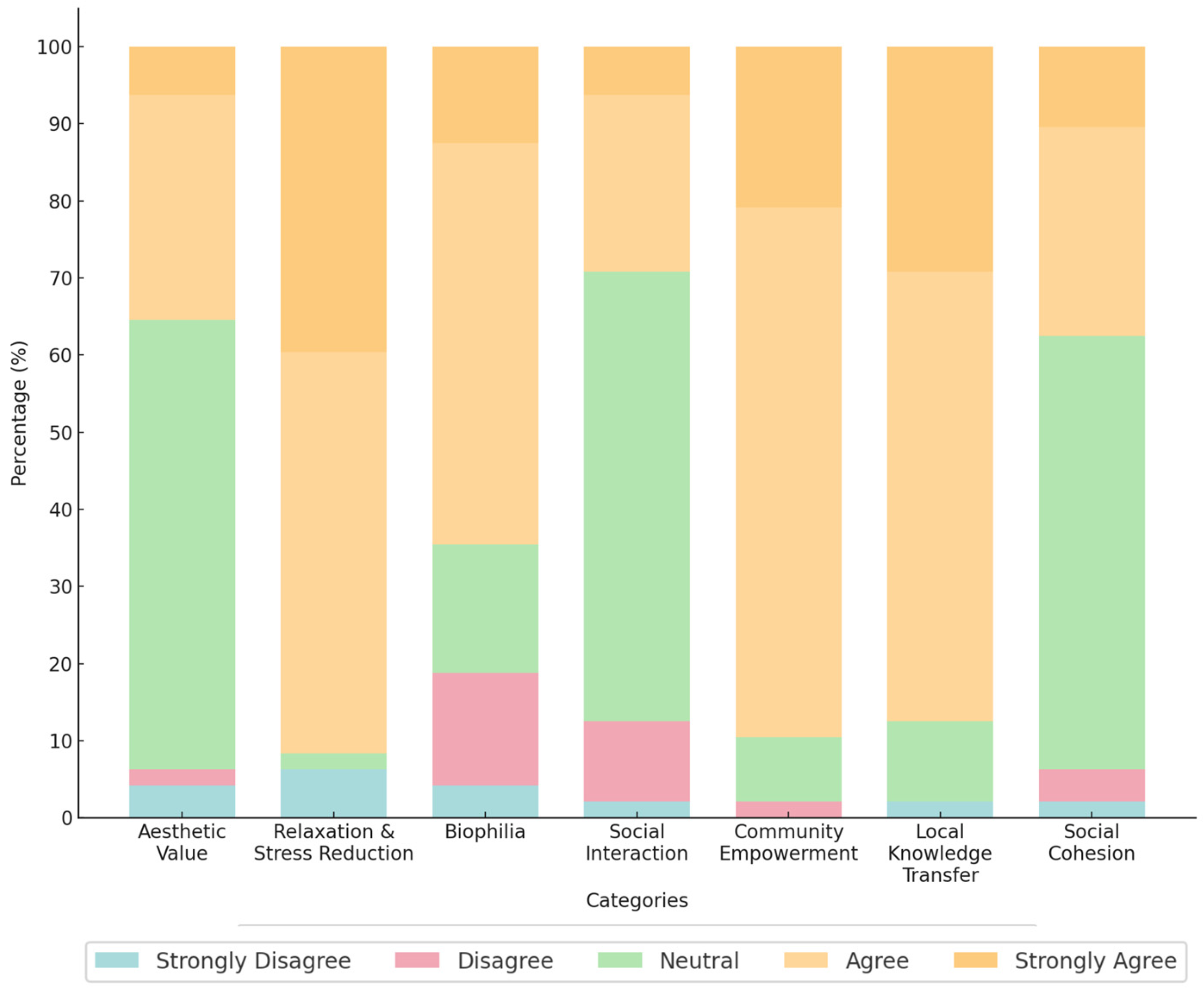

3.3. Cultural Services

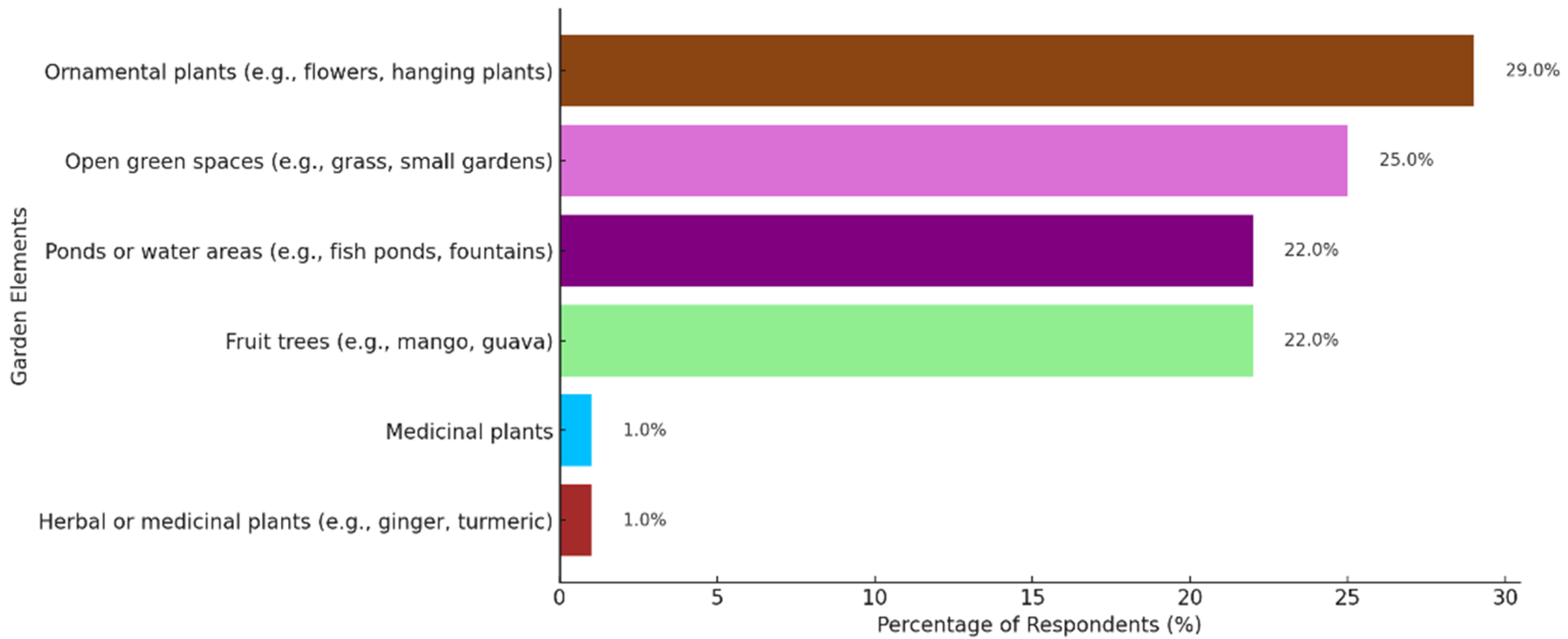

3.3.1. Perception of Esthetic Value

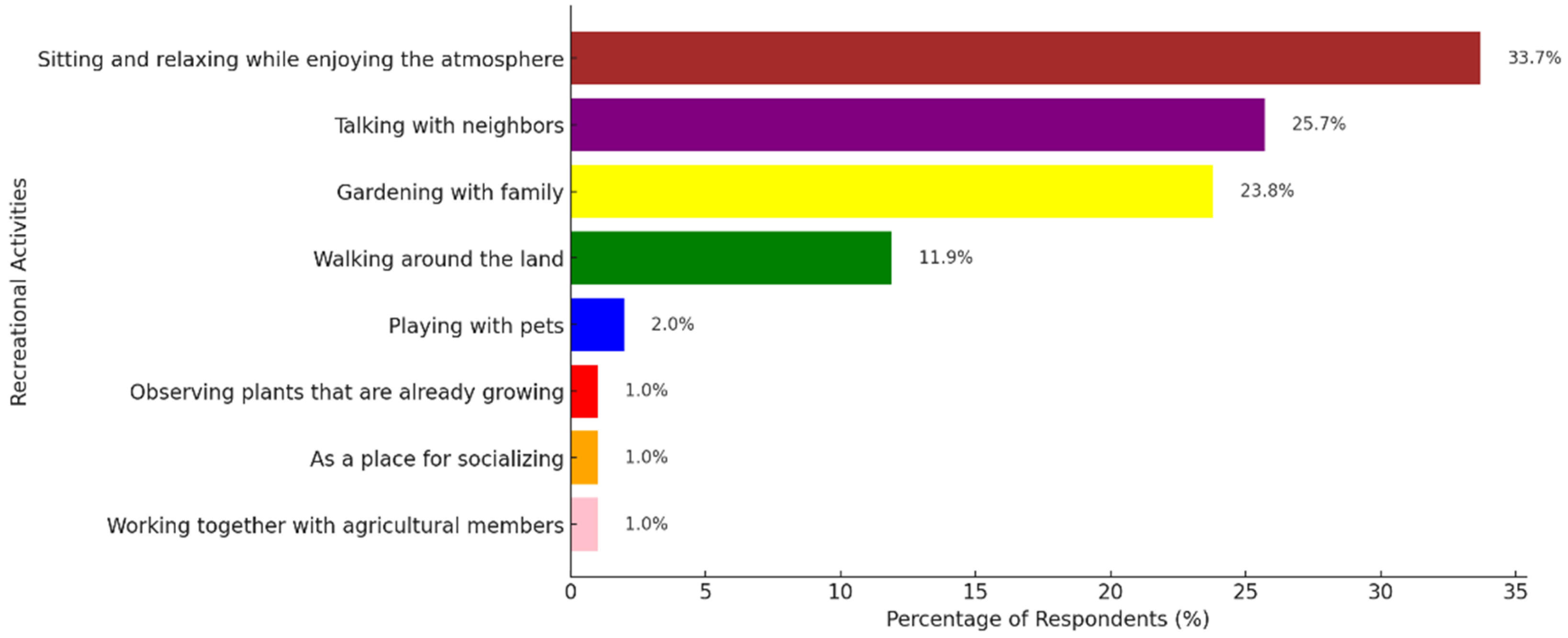

3.3.2. Perception of Relaxation and Stress Reduction

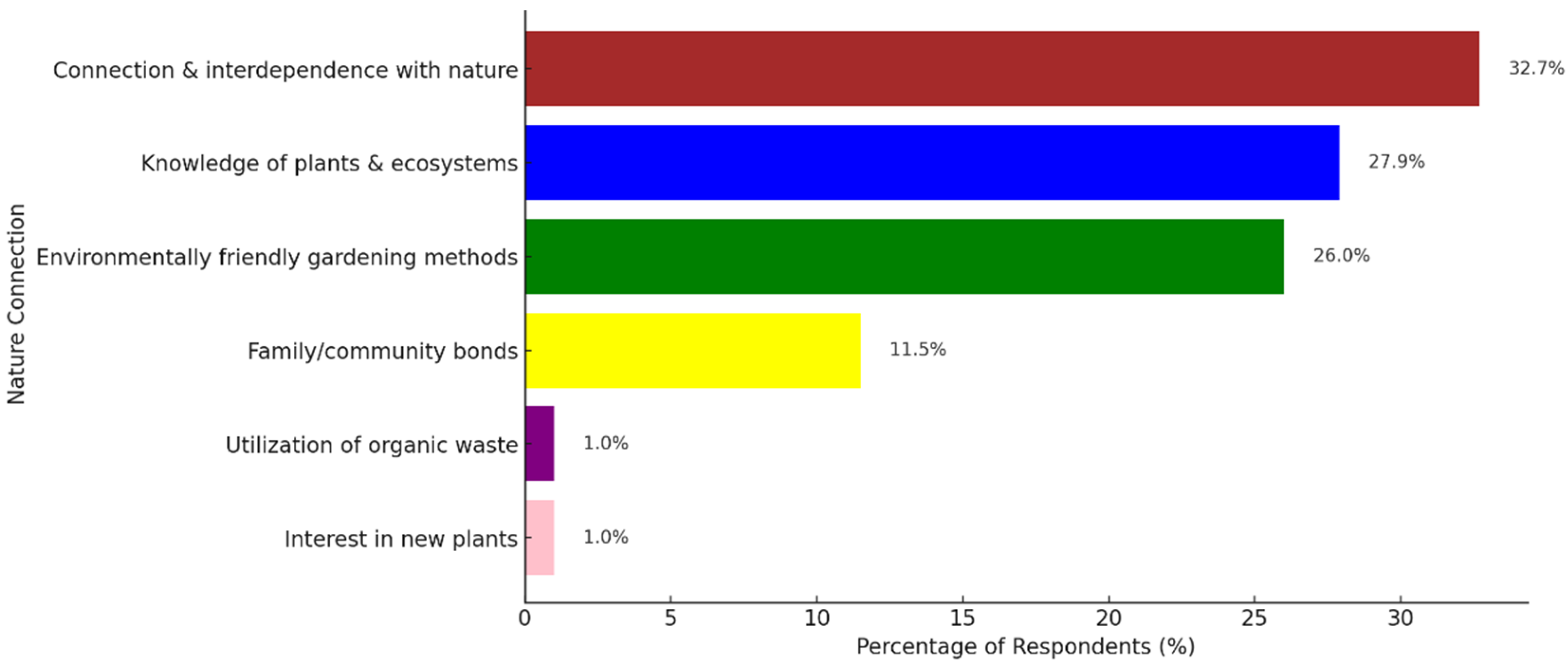

3.3.3. Perception of Biophilia

3.3.4. Perception of Social Interaction and Community Cohesion

3.3.5. Perception of Community Empowerment and Knowledge Sharing

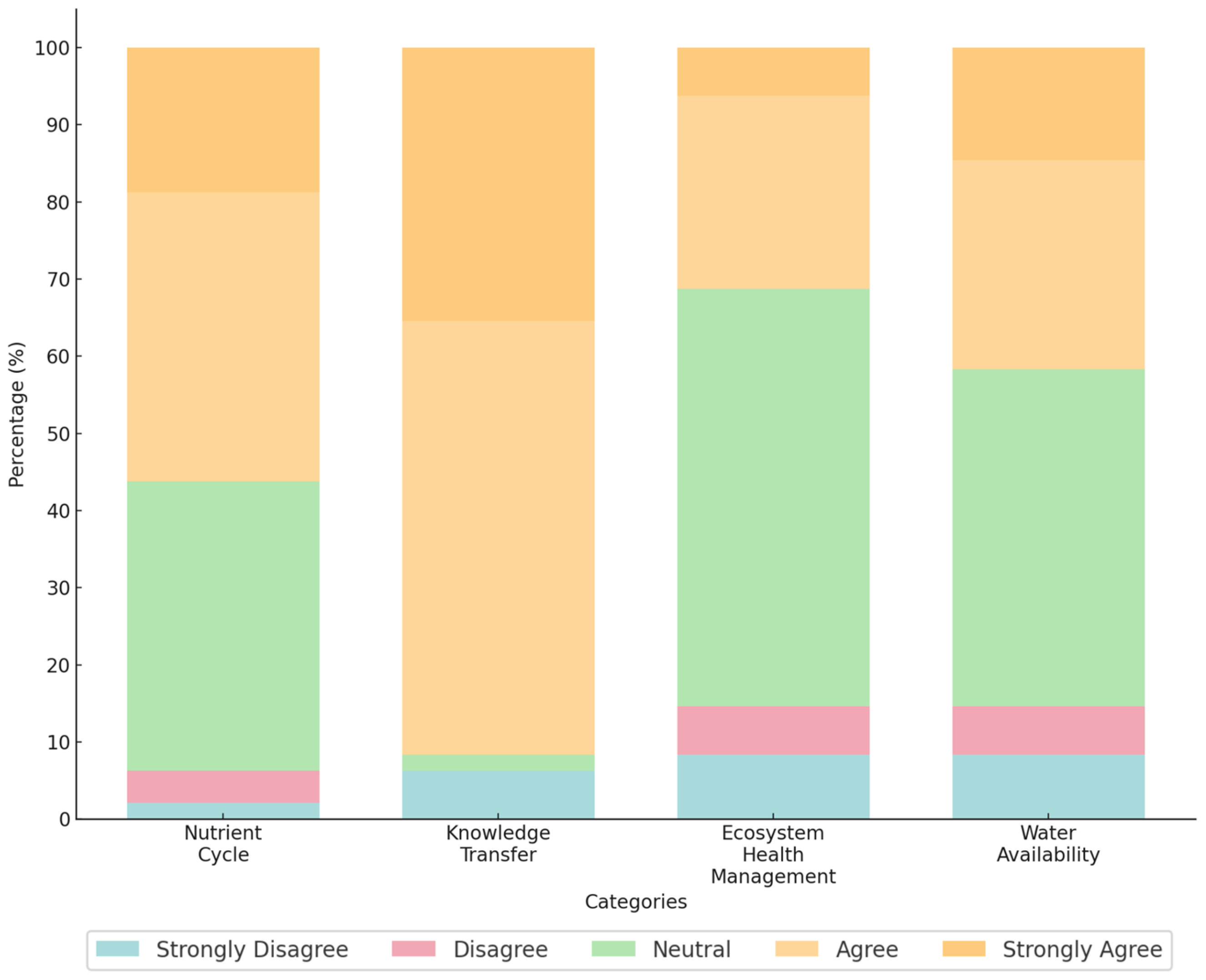

3.4. Supporting Services

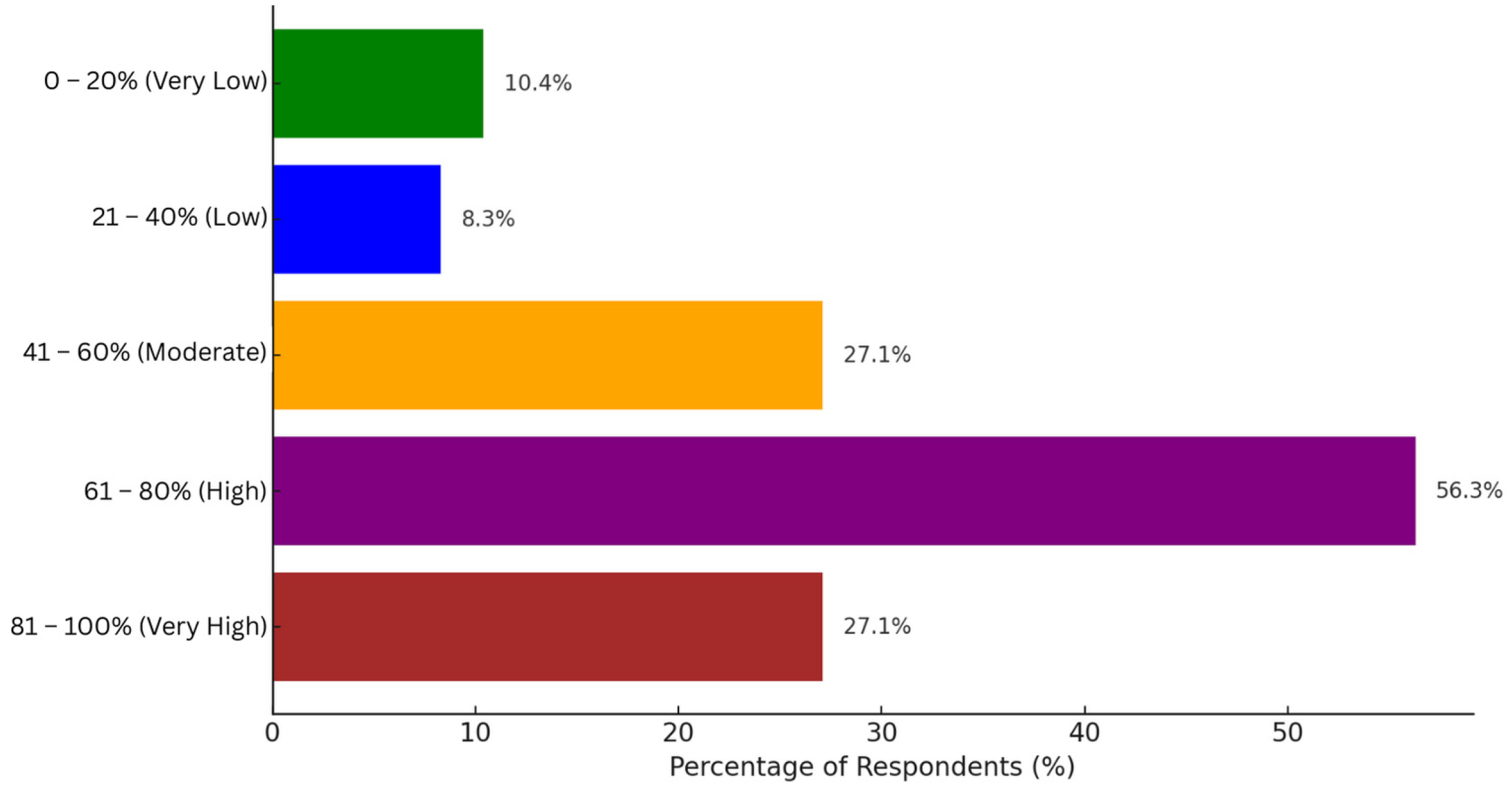

3.4.1. Perception of Knowledge Transfer Supporting Ecosystems

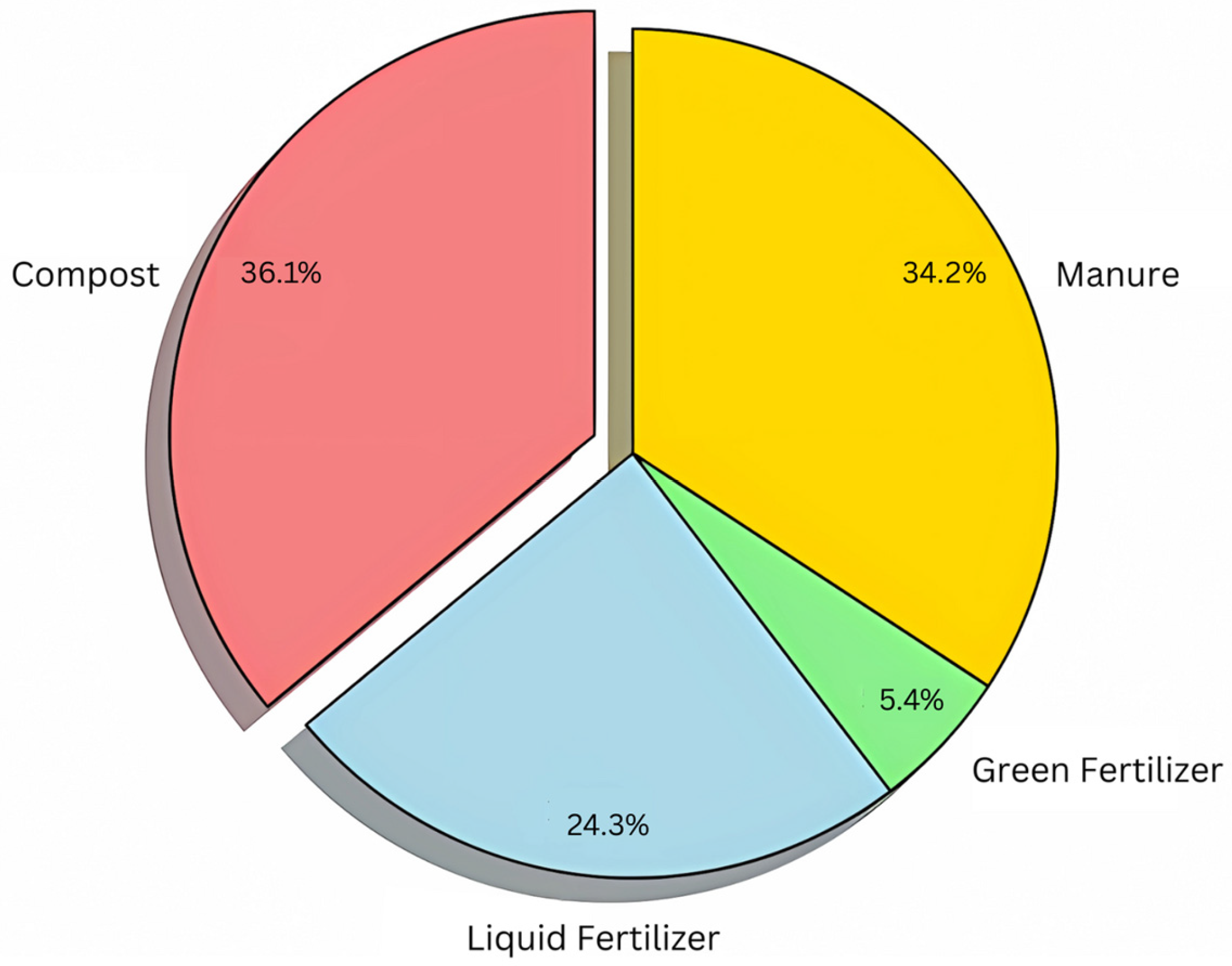

3.4.2. Perception of Nutrient Cycling and Soil Fertility

3.4.3. Perception of Ecosystem Health Management

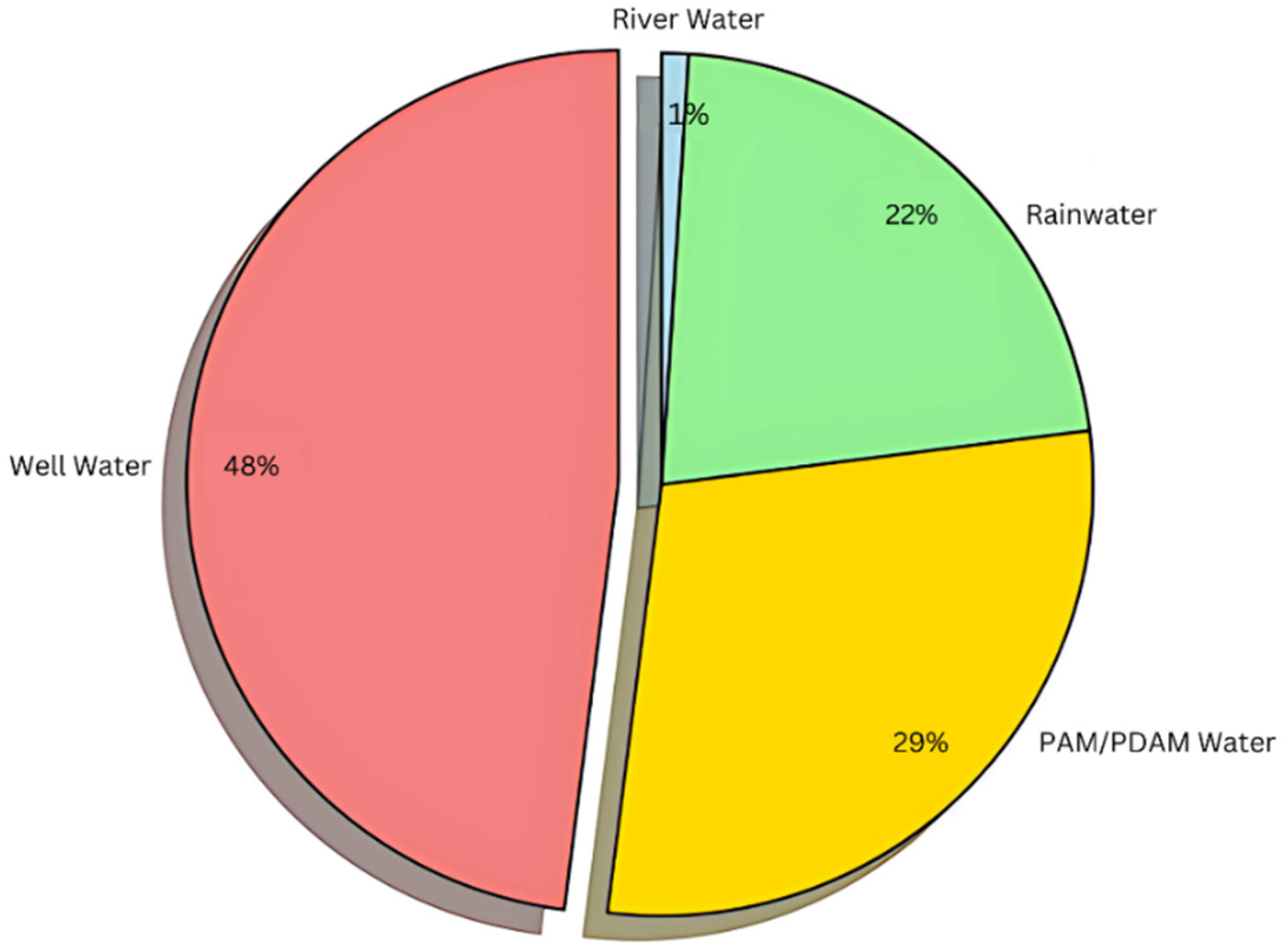

3.4.4. Perception of Water Availability

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giyarsih, S.R.; Armansyah; Zaelany, A.A.; Latifa, A.; Setiawan, B.; Saputra, D.; Haqi, M.; Lamijo; Fathurohman, A. Interrelation of Urban Farming and Urbanization: An Alternative Solution to Urban Food and Environmental Problems Due to Urbanization in Indonesia. Front. Built Environ. 2024, 9, 1192130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prastiyo, S.E.; Irham; Hardyastuti, S.; Jamhari, F. How Agriculture, Manufacture, and Urbanization Induced Carbon Emission? The Case of Indonesia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 42092–42103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pribadi, D.O.; Pauleit, S. The Dynamics of Peri-Urban Agriculture During Rapid Urbanization of Jabodetabek Metropolitan Area. Land Use Policy 2015, 48, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specht, K.; Schimichowski, J.; Fox-Kämper, R.; Specht, K.; Fox-Kämper, R.; Fox-Kämper, R.; Schimichowski, J. Multifunctional Urban Landscapes: The Potential Role of Urban Agriculture as an Element of Sustainable Land Management. In Sustainable Land Management in a European Context: A Co-Design Approach; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondhi, M.; Pratiwi, P.A.; Handini, V.T.; Sunartomo, A.F.; Budiman, S.A. Agricultural Land Conversion, Land Economic Value, and Sustainable Agriculture: A Case Study in East Java, Indonesia. Land 2018, 7, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunardi, S.; Ghulam, I.; Istiqomah, N.; Fadilah, K.; Safitri, K.I.; Abdoellah, O.S. Environmental Sustainability and Food Safety of the Practice of Urban Agriculture in Great Bandung. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2023, 18, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.A.; Gaw, L.Y.; Masoudi, M.; Richards, D.R. Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Sustainability: An Ecosystem Services Assessment of Plans for Singapore’s First “Forest Town”. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 610155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefani, M.C.; Orsini, F.; Magrefi, F.; Sanyé-Mengual, E.; Pennisi, G.; Michelon, N.; Bazzocchi, G.; Gianquinto, G. Toward the Creation of Urban Foodscapes: Case Studies of Successful Urban Agriculture Projects for Income Generation, Food Security, and Social Cohesion. In Urban Horticulture: Sustainability for the Future; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, N.; Reynolds, K. Resource Needs for a Socially Just and Sustainable Urban Agriculture System: Lessons From New York City. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2014, 30, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoellah, O.S.; Suparman, Y.; Safitri, K.I.; Basagevan, R.M.; Fianti, N.D.; Wulandari, I.; Husodo, T. Food Security of Urban Agricultural Households in the Area of North Bandung, West Java, Indonesia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, D.; Sitepu, G.L.; Nugraha, Y.R.; Permana Rosiyan, M.B. Social Metabolism in Buruan SAE: Individual Rift Perspective on Urban Farming Model for Food Independence in Bandung, Indonesia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soemarwoto, O.; Conway, G.R. The Javanese Homegarden; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kefale, B. Homegarden Agroforestry in Ethiopia—A Review. Int. J. Bio-Resour. Stress Manag. 2020, 11, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karyono, K. Traditional homegarden and its transforming trend. Bionatura 2000, 2, 218427. [Google Scholar]

- Iskandar, B.S.; Suryana, Y.; Mulyanto, D.; Iskandar, J.; Gunawan, R. Ethnomedicinal Aspects of Sundanese Traditional Homegarden: A Case Study in Rural Sumedang, West Java, Indonesia. J. Trop. Ethnobiol. 2023, 6, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, B.; Dahlan, M.; Arifin, H.; Nurhayati; Kaswanto; Nadhiroh, S.; Wahyuni, T.; Budiadi; Irawan, S. Landscape Character Assessment of Pekarangan towards Healthy and Productive Urban Village in Bandung City, Indonesia. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Environment, Agriculture and Tourism (ICOSEAT 2022); Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2022; Volume 26, pp. 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaiah, M.; Avtar, R. Urban Green Spaces and Their Need in Cities of Rapidly Urbanizing India: A Review. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, R.; Dewaelheyns, V.; Achten, W. Potential Ecosystem Services of Urban Agriculture: A Review. PeerJ Prepr. 2016, 4, e2286v1. [Google Scholar]

- George, M.A. Influence of Livelihood Assets on Biodiversity and Household Food Security in Tropical Homegardens Along Urbanisation Gradients. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 114049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Home Gardening and Urban Agriculture for Advancing Food and Nutritional Security in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyiola, A.O.; Babafemi, O.P.; Ogundahunsi, O.E.; Ojeleye, A.E. Food Security: A Pathway Towards Improved Nutrition and Biodiversity Conservation. In Biodiversity in Africa: Potentials, Threats and Conservation; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 79–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoellah, O.S.; Wulandari, I.; Safitri, K.I.; Fianti, N.D.; Basagevan, R.M.F.; Aini, M.N.; Amalia, R.I.; Suraloka, M.P.A.; Utama, G.L. Urban Agriculture in Great Bandung Region in the Midst of Commercialization, Food Insecurity, and Nutrition Inadequacy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royer, H.; Yengue, J.L.; Bech, N. Urban Agriculture and Its Biodiversity: What Is It and What Lives in It? Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 346, 108342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiryono; Kristiansen, P.; De Bruyn, L.L.; Saprinurdin; Nurliana, S. Ecosystem Services Provided by Agroforestry Home Gardens in Bengkulu, Indonesia: Smallholder Utilization, Biodiversity Conservation, and Carbon Storage. Biodiversitas 2023, 24, 2657–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z. On the Functions and Environmental Effects of Urban Agriculture. Int. J. Food Sci. Agric. 2023, 7, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J. Local Knowledge of Homegarden Plants in Miao Ethnic Communities in Laershan Region, Xiangxi Area, China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2024, 20, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoellah, O.S.; Schneider, M.; Nugraha, L.M.; Suparman, Y.; Voletta, C.T.; Withaningsih, S.; Parikesit; Heptiyanggit, A.; Hakim, L. Homegarden Commercialization: Extent, Household Characteristics, and Effect on Food Security and Food Sovereignty in Rural Indonesia. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 797–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwardi, A.B.; Navia, Z.I.; Mubarak, A.; Rahmat, R.; Christy, P.; Wibowo, S.G.; Irawan, H. The Diversity and Traditional Use of Home Garden Plants near Kerinci Seblat National Park, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 2024, 25, 3284–3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- deHaan, R.; Odame, H.H.; Thevathasan, N.V.; Nissanka, S.P. Local Knowledge and Perspectives of Change in Homegardens: A Photovoice Study in Kandy District, Sri Lanka. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourdes, K.; Gibbins, C.; Hamel, P.; Sanusi, R.; Azhar, B.; Lechner, A.M. A Review of Urban Ecosystem Services Research in Southeast Asia. Land 2021, 10, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Octarino, C.N. Efektivitas Pertanian Perkotaan (Urban Farming) Dalam Mitigasi Urban Heat Island Di Kawasan Perkotaan. ATRIUM J. Arsit. 2022, 8, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marando, F.; Heris, M.P.; Zulian, G.; Udías, A.; Mentaschi, L.; Chrysoulakis, N.; Parastatidis, D.; Maes, J. Urban Heat Island Mitigation by Green Infrastructure in European Functional Urban Areas. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 77, 103564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansanga, M.M.; Luginaah, I.; Bezner Kerr, R.; Dakishoni, L.; Lupafya, E. Determinants of Smallholder Farmers’ Adoption of Short-Term and Long-Term Sustainable Land Management Practices. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2021, 36, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthel, S.; Isendahl, C. Urban Gardens, Agriculture, and Water Management: Sources of Resilience for Long-Term Food Security in Cities. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 86, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paganin, G.; Orsini, F.; Migliore, M.; Venis, K.; Poli, M. Metropolitan Farms: Long Term Agri-Food Systems for Sustainable Urban Landscapes. Urban Book Ser. 2023, F813, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadani, H.; Rashid, S.M.; Parrah, J.D.; Khan, A.A.; Dar, K.A.; Ganie, A.A.; Gazal, A.; Dar, R.A.; Ali, A. Traditional Farming Practices and Its Consequences. In Microbiota and Biofertilizers, Vol 2: Ecofriendly Tools for Reclamation of Degraded Soil Environs; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, A.; Abdoellah, O.S.; Utama, G.L. Harnessing Cultural Heritage Knowledge for Sustainable Urban Agriculture in Bandung. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 495, 03002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfanuzzaman, M.; Dahiya, B. Sustainable Urbanization in Southeast Asia and Beyond: Challenges of Population Growth, Land Use Change, and Environmental Health. Growth Change 2019, 50, 725–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artmann, M.; Sartison, K. The Role of Urban Agriculture as a Nature-Based Solution: A Review for Developing a Systemic Assessment Framework. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, A.; De Marco, A.; Proietti, P.; Arellano Vazquez, D.A.; Gagliano, E.; Del Borghi, A.; Tacchino, V.; Spotorno, S.; Gallo, M. Carbon Farming of Main Staple Crops: A Systematic Review of Carbon Sequestration Potential. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, E.; Roth, M.; Norford, L.; Molina, L.T. Does Urban Vegetation Enhance Carbon Sequestration? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 148, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeshamurthy, A.N.; Kalaivanan, D.; Rajendiran, S. Carbon Sequestration Potential of Perennial Horticultural Crops in Indian Tropics. In Carbon Management in Tropical and Sub-Tropical Terrestrial Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zutter, C.; Stoltz, A. Community Gardens and Urban Agriculture: Healthy Environment/Healthy Citizens. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 32, 1452–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, L.; Stathopoulos, T.; Marey, A.M. Urban Microclimate and Its Impact on Built Environment—A Review. Build. Environ. 2023, 238, 110334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koay, W.I.; Dillon, D. Community Gardening: Stress, Well-Being, and Resilience Potentials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, S.; Haque, M.E.; Afrad, M.S.I.; Rahman, G.M.M.; Rahman, M.M. Farmers’ Perception Towards Forest Ecosystem Services and Human Well-Being. Eur. J. Agric. Food Sci. 2023, 5, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, J.; Hou, Y.; Wen, Y. Improving Well-Being of Farmers Using Ecological Awareness Around Protected Areas: Evidence From Qinling Region, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomala, V.; Grant, D. Exploring Supply Chain Issues Affecting Food Access and Security Among Urban Poor in South Africa. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2021, 33, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silitonga, R.M.; Wee, H.-M.; Jou, Y.-T. Framework for Blockchain Technology Adoption in Supply Chain for Small and Medium Indonesian Urban Farming: A Case Study. In Proceedings of the 5th IEEE Eurasian Conference on Educational Innovation 2022, ECEI 2022, Taipei, Taiwan, 10–12 February 2022; pp. 181–184. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland, D.A.; Phares, N.; Nightingale, K.D.; Weatherby, R.L.; Radis, W.; Ballard, J.; Campagna, M.; Kurtz, D.; Livingston, K.; Riechers, G.; et al. The Potential for Urban Household Vegetable Gardens to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 157, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushothaman, S.; Sadashiva, V.P.; Dhanush, K.M. Agroecological Impacts of Urban Demand for Fresh Vegetables: Preliminary Insights from Exploratory Surveys in Bengaluru. Ecol. Econ. Soc.–INSEE J. 2022, 5, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerster-Bentaya, M. Nutrition-Sensitive Urban Agriculture. Food Secur. 2013, 5, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandiyaraj, P.; Lekha, S.S.; Lakshmi, N.V.; Sanmaya, A.M.; Vinisha, V.; Gopika, B.; Chezhiyan, K.K.; Prithiviraj, M.R.; Willson, M.A.S.; Udhayavanan, U. Underutilized Vegetable Crops: Potential Sources of Nutrition and Livelihood Security. Eur. J. Nutr. Food Saf. 2024, 16, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, A.; Abdoellah, O.S.; Utama, G.L. Challenges and Opportunities of Urban Agriculture Programme Implementation in Indonesia: Social, Economic, and Environmental Perspectives. Local. Environ. 2024, 29, 1490–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmasary, A.N.; Koop, S.H.A.; van Leeuwen, C.J. Assessing Bandung’s Governance Challenges of Water, Waste, and Climate Change: Lessons from Urban Indonesia. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2021, 17, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulandari, I.; Husodo, T.; Mulyanto, D.; Abdoellah, O.S.; Amalia, C.A.; Farhaniah, S.S. Supporting Food Security through Urban Home Gardening, Rancasari Sub-District, Bandung City, West Java, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 2023, 24, 5618–5625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchette, A.; Trammell, T.L.E.; Pataki, D.E.; Endter-Wada, J.; Avolio, M.L. Plant Biodiversity in Residential Yards Is Influenced by People’s Preferences for Variety but Limited by Their Income. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, B.; Hauschild, M.Z.; Fernández, J.; Birkved, M. Contributions of Local Farming to Urban Sustainability in the Northeast United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 7340–7349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, R.W.; Sutrisno, J. Urban Farming Development Strategy to Achieve Sustainable Agriculture in Magelang, Indonesia. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2023, 13, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozdziewicz-Biechonska, J.; Brzezińska-Rawa, A. Protecting Ecosystem Services of Urban Agriculture Against Land-Use Change Using Market-Based Instruments. A Polish Perspective. Land Use Policy 2022, 120, 106296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuller, M.; Farrelly, M.; Marthanty, D.R.; Deletic, A.; Bach, P.M. Planning Support Systems for Strategic Implementation of Nature-Based Solutions in the Global South: Current Role and Future Potential in Indonesia. Cities 2022, 126, 103693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyé-Mengual, E.; Specht, K.; Vávra, J.; Artmann, M.; Orsini, F.; Gianquinto, G. Ecosystem Services of Urban Agriculture: Perceptions of Project Leaders, Stakeholders and the General Public. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyé-Mengual, E.; Gasperi, D.; Michelon, N.; Orsini, F.; Ponchia, G.; Gianquinto, G. Eco-Efficiency Assessment and Food Security Potential of Home Gardening: A Case Study in Padua, Italy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canedoli, C.; Bullock, C.; Collier, M.; Joyce, D.; Padoa-Schioppa, E. Public Participatory Mapping of Cultural Ecosystem Services: Citizen Perception and Park Management in the Parco Nord of Milan (Italy). Sustainability 2017, 9, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liere, H.; Egerer, M.; Sanchez, C.; Bichier, P.; Philpott, S.M. Social Context Influence on Urban Gardener Perceptions of Pests and Management Practices. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 547877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonde, K.M.; Tsehay, A.S.; Lemma, S.E. The Impact of Training on the Application of Modern Agricultural Inputs: Evidence from Wheat and Maize Growers in Northwest Ethiopia. Int. J. Train. Res. 2023, 21, 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, B.H.; Jang, E.J. Awareness of Daegu Citizens on Urban Agriculture. J. People Plants Environ. 2016, 19, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzke, N.; Konig, B.; Bokelmann, W. Plant Protection in Private Gardens in Germany: Between Growing Environmental Awareness, Knowledge and Actual Behaviour. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2021, 86, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neil, K.; Wu, J.; Bang, C.; Faeth, S. Urbanization Affects Plant Flowering Phenology and Pollinator Community: Effects of Water Availability and Land Cover. Ecol. Process 2014, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prastica, R.M.S.; Apriatresnayanto, R.; Marthanty, D.R. Structural and Green Infrastructure Mitigation Alternatives Prevent Ciliwung River from Water-Related Landslide. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2019, 9, 1825–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, M.N.; Wibowo, E.; Susilastuti, D.; Diana, T.B. Analysis of Factors Affecting Community Participation Expectations on Sustainability Urban Farming in Jakarta City. Int. J. Sci. Soc. 2022, 4, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X. Empowering Informal Settlements in Jakarta with Urban Agriculture: Exploring a Community-Based Approach. Urban Res. Pract. 2021, 14, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoni, V.D.N.; Ramli, N.N.; Shamsudin, M.N.; Hadi, A.H.I.A. Urban Agriculture and Policy: Mitigating Urban Negative Externalities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 75, 127710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantirasari, A.J.; Subianto, A.; Tamrin, M.H. Analysis Of City Government And Farming Community Partnership in Food Security Policy: Urban Farming Program. Soc. Sci. Humanit. J. 2024, 8, 5276–5288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, L.; Kuhns, J.; Nasr, J. Urban Agriculture Practice, Policy and Governance. In Routledge Handbook of Urban Food Governance; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.N. Geo-Sustainable Practices in Urban Agriculture: A Study of Sustainable Land Use and Natural Resource Conservation at Household Level. Res. J. Soc. Issues 2024, 6, 412–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpopi, C.; Burcea, S.G.; Popescu, R.I.; Burlacu, S. Evaluation of Romania’S Progress in Achieving Sdg 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities. Appl. Res. Adm. Sci. 2022, 3, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Mina, U.; Kumar, B.M. Homegarden Agroforestry Systems in Achievement of Sustainable Development Goals. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 42, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, Y. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Local Self-Government: Approaches and Strategies for Sustainable Education. Lex Localis J. Local. Self-Gov. 2024, 22, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, L.; Gray, L.E.; Thai, C.L. More Than Food: The Social Benefits of Localized Urban Food Systems. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 534219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.M.; Breuste, J.; Ahmad, A.; Aziz, A.; Aldosari, A. Quantifying the Impacts of Urbanization on Urban Agriculture and Food Security in the Megacity Lahore, Pakistan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhialdin, B.J.; Filimonau, V.; Qasem, J.M.; Algboory, H. Traditional Foodstuffs and Household Food Security in a Time of Crisis. Appetite 2021, 165, 105298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegner, A.B.; Sowerwine, J.; Acey, C. Does Urban Agriculture Improve Food Security? Examining the Nexus of Food Access and Distribution of Urban Produced Foods in the United States: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, S. Urbanisation and Food Insecurity Risks: Assessing the Role of Human Development. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 2015, 44, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, C.J.P.; Tonello, K.C.; Nnadi, E. Urban Gardens and Soil Compaction: A Land Use Alternative for Runoff Decrease. Environ. Process. 2021, 8, 1213–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, S.; Tarashkar, M.; Matloobi, M.; Wang, Z.; Rahimi, A. Understanding the Dynamics of Urban Horticulture by Socially-Oriented Practices and Populace Perception: Seeking Future Outlook through a Comprehensive Review. Land Use policy 2022, 122, 106398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Che, Y.; Marshall, S.; Maltby, L. Heterogeneity in Ecosystem Service Values: Linking Public Perceptions and Environmental Policies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, M.Y.; Hassan, M.L.; Anak Empidi, A.V.; Juraimi, U.F.; Mohd Noorazman, N.; Emang, D. Public Perceptions on the Importance of Ecosystem Services From Vulnerable Forest: A Case Study of Ampang Forest Reserve, Selangor, Malaysia. J. Manaj. Hutan Trop. 2024, 30, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y. Ecosystem Services and Public Perception of Green Infrastructure From the Perspective of Urban Parks: A Case Study of Luoyang City, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukharta, O.F.; Huang, I.Y.; Vickers, L.; Navas-Gracia, L.M.; Chico-Santamarta, L. Benefits of Non-Commercial Urban Agricultural Practices—A Systematic Literature Review. Agronomy 2024, 14, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Villarino, M.T.; Briz, T. With Sustainable Use of Local Inputs, Urban Agriculture Delivers Community Benefits beyond Food. Calif. Agric. 2022, 76, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, J.; Cilliers, E.J.; Cilliers, S.S.; Lategan, L. Food for Thought: Addressing Urban Food Security Risks Through Urban Agriculture. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, N.F.; Cai, Y.M.; Shen, Y.J.; Ji, X.Y.; Wu, X.W.; Zheng, X.R.; Cheng, W.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y.P.; Chen, X.; et al. Increasing Plant Diversity with Border Crops Reduces Insecticide Use and Increases Crop Yield in Urban Agriculture. eLife 2018, 7, e35103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, J.B.; Abias, M.; Mupenzi, C. Assessing the Use of Hillside Rainwater Harvesting Ponds on Agricultural Production, a Case of Unicoopagi Cooperative Union. Int. J. Nat. Resour. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 5, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Ouyang, Z.; Liu, H.; Cui, Z.; Lu, Z.; Crittenden, J.C. Courtyard Integrated Ecological System: An Ecological Engineering Practice in China and Its Economic-Environmental Benefit. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 133, 1363–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, B. Review: Agricultural Urbanism: Handbook for Building Sustainable Food & Agriculture Systems in 21st Century Cities. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2014, 34, 237–239. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, S.; Rao, N.; Koduganti, M.; Singh, C.; Poonacha, P.; Sharma, S.; Roy, P.; Mahalingam, A.; Nishant, S. Sowing Sustainable Cities: Lessons for Urban Agriculture Practices in India; Indian Institute For Human Settlements (IIHS): Bangalore, India, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Awang, N. Fostering Empowerment of Urban Community Gardening Through Urban Agriculture Initiatives in Malaysia. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2024, 14, 3115–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safitri, K.I.; Abdoellah, O.S.; Gunawan, B. Urban Farming as Women Empowerment: Case Study Sa’uyunan Sarijadi Women’s Farmer Group in Bandung City. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2021; Volume 249. [Google Scholar]

- Nazuri, N.S.; Rosnon, M.R.; Salim, S.S.M.; Ahmad, M.F.; Suhaimi, S.S.A.; Safwan, N.S.Z. Promoting Economic Empowerment Through Effective Implementation and Linking Social Capital in Urban Agriculture Programs. J. Law Sustain. Dev. 2023, 11, e726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, N.; Mahmoudi, D.; Simpson, M.; Santos, J.F.F. Socio-Spatial Differentiation in the Sustainable City: A Mixed-Methods Assessment of Residential Gardens in Metropolitan Portland, Oregon, USA. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 148, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, W.J.; Creswell, J.D. RESEARCH DESIGN: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; SAGE Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2022; Volume 283. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, C.; DeLong, A.; Diaz, J.M. Commercial Urban Agriculture in Florida: A Qualitative Needs Assessment. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2022, 38, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A.; Bell, E.; Reck, J.; Fields, J. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022; p. 412. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batini, C.; Cappiello, C.; Francalanci, C.; Maurino, A. Methodologies for Data Quality Assessment and Improvement. ACM Comput. Surv. 2009, 41, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.A.; Dunford, R.W.; Barton, D.N.; Kelemen, E.; Martín-López, B.; Norton, L.; Termansen, M.; Saarikoski, H.; Hendriks, K.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; et al. Selecting Methods for Ecosystem Service Assessment: A Decision Tree Approach. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 29, 481–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasada, I.; Benninger, S.; Weltin, M. Survey Data on Home Gardeners and Urban Gardening Practice in Pune, India. Data Brief. 2019, 27, 104652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, S.D.C.; Oelofse, M.; Hou, Y.; Oenema, O.; Jensen, L.S. Farmer Perceptions and Use of Organic Waste Products as Fertilisers—A Survey Study of Potential Benefits and Barriers. Agric. Syst. 2017, 151, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriyadi, E.I. Pemberdayaan Masyarakat Dusun Sanan Melalui Pemanfaatan Lahan Pekarangan Dengan Budidaya Sayuran Dan Tanaman Obat. J. Pengabdi. Kpd. Masy. Membangun Negeri 2022, 6, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputri, R.; Lestari, L.A.; Susilo, J. Pola Konsumsi Pangan Dan Tingkat Ketahanan Pangan Rumah Tangga Di Kabupaten Kampar Provinsi Riau. J. Gizi Klin. Indones. 2016, 12, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyanto, S.; Nurhadi, I.; Pintakami, L.B. Pemberdayaan Dan Penanganan Pola Konsumsi Pangan Masyarakat Di Wilayah Kota Batu. J. Ekon. Pertan. Dan Agribisnis 2022, 6, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalia, I.N.; Mahmudiono, T. Hubungan Pendapatan, Total Pengeluaran, Proporsi Pengeluaran Pangan Dengan Status Ketahanan Rumah Tangga Petani Gurem (Studi Di Desa Nogosari Kecamatan Rambipuji Kabupaten Jember). Amerta Nutr. 2017, 1, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- If’all; Unsunnidhal, L.; Hakim, I. Tumbuh Bersama: Mendukung Pertanian Lokal, Ketahanan Pangan, Kelestarian Lingkungan, Dan Pengembangan Masyarakat. J. Pengabdi. West Sci. 2023, 2, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armson, D.; Stringer, P.; Ennos, A.R. The Effect of Tree Shade and Grass on Surface and Globe Temperatures in an Urban Area. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Li, S.; Xing, X.; Zhou, X.; Kang, Y.; Hu, Q.; Li, Y. Cooling Benefits of Urban Tree Canopy: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Li, C.; Ye, L.; Xiao, L.; Gao, X.; Mo, L.; Du, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, G. Effect of the Roadside Tree Canopy Structure and the Surrounding on the Daytime Urban Air Temperature in Summer. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 316, 108850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suripto, S.; Jupri, A.; Farista, B.; Virgota, A.; Ahyadi, H. Ecological Valuation of City Parks (Case Study for Mataram City). J. Biol. Trop. 2021, 21, 1003–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Qiu, S.; Tan, X.; Zhuang, Y. Measuring the Relationship between Morphological Spatial Pattern of Green Space and Urban Heat Island Using Machine Learning Methods. Build. Environ. 2023, 228, 109910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, A.; Saha, P.; Patel, S.; Bera, A.; Barman, A.; Saha, P.; Patel, S.; Bera, A. Crop Diversification an Effective Strategy for Sustainable Agriculture Development. In Sustainable Crop Production—Recent Advances; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderi, A.R.; Arsi, A.; Utami, M.; Bintang, A.; Amanda, D.S.; Sakinah, A.N.; Malini, R. Peranan Serangga Untuk Mendukung Sistem Pertanian Berkelanjutan. Semin. Nas. Lahan Suboptimal 2021, 9, 249–259. [Google Scholar]

- Schueller, S.K.; Li, Z.; Bliss, Z.; Roake, R.; Weiler, B. How Informed Design Can Make a Difference: Supporting Insect Pollinators in Cities. Land 2023, 12, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocco, A.; Speranza, S.; Onofre Costa, A.; Soares, M.; Zappala, L.; Bugin, G.; Lenzi, L.; Ranzani, G.; Barisan, L.; Porrini, C.; et al. Agriculture and Pollinating Insects, No Longer a Choice but a Need: EU Agriculture’s Dependence on Pollinators in the 2007–2019 Period. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samways, M.J.; Barton, P.S.; Birkhofer, K.; Chichorro, F.; Deacon, C.; Fartmann, T.; Fukushima, C.S.; Gaigher, R.; Habel, J.C.; Hallmann, C.A.; et al. Solutions for Humanity on How to Conserve Insects. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 242, 108427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasi, R.; Brunori, E. Agrobiodiversity-Based Landscape Design in Urban Areas. Plants 2023, 12, 4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Lima, M.F. The Association between Maintenance and Biodiversity in Urban Green Spaces: A Review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 251, 105153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekarlangit, N.; Satwiko, P. Arsitektur Nabati: Respon Ruang Paska Pandemi COVID-19 Di Indonesia. MODUL 2023, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikanth, D.R.K. Advancing Sustainable Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review for Optimizing Food Production and Environmental Conservation. Int. J. Plant Soil. Sci. 2023, 35, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M. How Might Contact with Nature Promote Human Health? Promising Mechanisms and a Possible Central Pathway. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 141022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.B.; Chang, C.C.; Astell-Burt, T.; Feng, X.; Gardner, J.; Andersson, E. Nature Experience from Yards Provide an Important Space for Mental Health during Covid-19. Npj Urban Sustain. 2023, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felappi, J.F.; Sommer, J.H.; Falkenberg, T.; Terlau, W.; Kötter, T. Green Infrastructure through the Lens of “One Health”: A Systematic Review and Integrative Framework Uncovering Synergies and Trade-Offs between Mental Health and Wildlife Support in Cities. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 748, 141589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, M.; Wendel-Vos, W.; van Poppel, M.; Kemper, H.; van Mechelen, W.; Maas, J. Health Benefits of Green Spaces in the Living Environment: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Studies. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 806–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghibi, M.; Farrokhi, A.; Faizi, M. Small Urban Green Spaces: Insights into Perception, Preference, and Psychological Well-Being in a Densely Populated Areas of Tehran, Iran. Environ. Health Insights 2024, 18, 11786302241248314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabon, L.; Shih, W.-Y.; Jou, S.-C. Integration of Knowledge Systems in Urban Farming Initiatives: Insight from Taipei Garden City. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 18, 857–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, E.A. Perceptions and Knowledge of Ecosystem Services in Urban River Systems, Eastern Cape, South Africa. Urban Ecosyst. 2024, 27, 1905–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnaud, C.; Corbera, E.; Muradian, R.; Salliou, N.; Sirami, C.; Vialatte, A.; Choisis, J.P.; Dendoncker, N.; Mathevet, R.; Moreau, C.; et al. Ecosystem Services, Social Interdependencies, and Collective Action: A Conceptual Framework. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fida, N.N.; Purwandari, H. Hubungan Produktivitas Kerja Kelompok Dengan Keberlanjutan Program Urban Farming. J. Sains Komun. Dan Pengemb. Masy. 2022, 6, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukti, G.W.; Charina, A.; Andriani, R.; Kusumo, B.; Ir, J.; Km, S.; Sumedang, K.; Barat, J. Model Kolaborasi Petani Muda Dalam Ekosistem Wirausaha Pertanian (Sebuah Pengalaman Pada Petani Muda Hortikultura Di Jawa Barat). Mimb. Agribisnis J. Pemikir. Masy. Ilm. Berwawasan Agribisnis 2024, 10, 932–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthfiasari, A.; Nurhadi, N.; Purwanto, D. Kebijakan Petani Urban Di Tengah Keterbatasan Lahan Di Kota Cilacap. J. Socius J. Sociol. Res. Educ. 2022, 9, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasmini, L.; Fadilah, F.; Dwi Yulianto, U.; Fitria, W.; Suhendar, N.; Malik Adnani, W.; Nur Afifah Sunarya, S. PENERAPAN SISTEM HIDROPONIK UNTUK LAHAN PERKEBUNAN DI DESA CIBALONGSARI. J. Buana Pengabdi. 2021, 3, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adetya, A. Optimasi Program Urban Farming Untuk Mengatasi Kerawanan Pangan Di Daerah Perkotaan. Policy Brief Pertan. Kelaut. Dan Biosains Tropika 2024, 6, 766–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryani, S.; Nuraini, A.; Windiyaningsih, C.; Alviansyah, M.D.; Gumilar, M. Pendampingan Kemandirian Ekonomi Kerakyatan Melalui Program Pertanian Perkotaan “Budikdamber Dan Hidroponik Sistem Sumbu”. J. Pelayanan Dan Pengabdi. Kesehat. Untuk Masyarakat 2023, 1, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Jiang, P.; Wang, R.; Guo, J.; Xiao, H.; Wu, J.; Shaaban, M.; Li, Y.; Huang, M. Organic Fertilizer Substituting 20% Chemical N Increases Wheat Productivity and Soil Fertility but Reduces Soil Nitrate-N Residue in Drought-Prone Regions. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1379485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Liébana, N.; Crespo-Barreiro, A.; Mazuecos-Aguilera, I.; González-Andrés, F. Improved Organic Fertilisers Made from Combinations of Compost, Biochar, and Anaerobic Digestate: Evaluation of Maize Growth and Soil Metrics. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazcano, C.; Zhu-Barker, X.; Decock, C. Effects of Organic Fertilizers on the Soil Microorganisms Responsible for N2O Emissions: A Review. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, B.C.; Pramanik, P.; Bhaduri, D. Organic Fertilizers for Sustainable Soil and Environmental Management. In Nutrient Dynamics for Sustainable Crop Production; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, D.J.; Young, J.A.; Hains, B.J.; Hains, K. The Development of a Backyard Composting Project Through Community Engagement. J. Ext. 2023, 61, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A. Impact of Crop Residue and Green Manure Management in Rice Crop on Soil Nutrient Dynamics in Tarai Belt of Shivalik Himalaya, India. Int. J. Plant Soil. Sci. 2023, 35, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Manuel, D.B.; Op de Beeck, M.; Shahbaz, M.; Chen, Y.; Deng, X.; Xu, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, Z. Rotation Cropping and Organic Fertilizer Jointly Promote Soil Health and Crop Production. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 315, 115190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, M.R.; Veum, K.S.; Parker, P.A.; Holan, S.H.; Karlen, D.L.; Amsili, J.P.; van Es, H.M.; Wills, S.; Seybold, C.A.; Moorman, T.B. The Soil Health Assessment Protocol and Evaluation Applied to Soil Organic Carbon. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2021, 85, 1196–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, J.; Madureira, L.; Marques, C.; Silva, R. Understanding Farmers’ Adoption of Sustainable Agriculture Innovations: A Systematic Literature Review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaminuka, N.; Dube, E.; Kabonga, I.; Mhembwe, S. Enhancing Urban Farming for Sustainable Development Through Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Dev. Goals Ser. 2021, F2673, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toku, A.; Twumasi Amoah, S.; Nyabanyi N-yanbini, N. Exploring the Potentials of Urban Crop Farming and the Question of Environmental Sustainability. City Environ. Interact. 2024, 24, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Laghari, Y.; Wei, Y.-C.; Wu, L.; He, A.-L.; Liu, G.-Y.; Yang, H.-H.; Guo, Z.-Y.; Leghari, S.J.; Du, J.; et al. Groundwater Depletion and Degradation in the North China Plain: Challenges and Mitigation Options. Water 2024, 16, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, M.; Liaqat, M.U.; Baig, F.; Al-Rashed, M. Water Resources Availability, Sustainability and Challenges in the GCC Countries: An Overview. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yar, P. Urban Development and Its Impact on the Depletion of Groundwater Aquifers in Mardan City, Pakistan. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 11, 100426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Rao, L.; Connelly, S.; Raj, A.; Raveendran, L.; Shirin, S.; Jamwal, P.; Helliwell, R. Sustainable Water Resources through Harvesting Rainwater and the Effectiveness of a Low-Cost Water Treatment. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 286, 112223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-Elaty, I.; Kuriqi, A.; Ahmed, A.; Ramadan, E.M. Enhanced Groundwater Availability through Rainwater Harvesting and Managed Aquifer Recharge in Arid Regions. Appl. Water Sci. 2024, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saputra, A.; Abdoellah, O.S.; Utama, G.L.; Wulandari, I.; Mulyanto, D.; Suparman, Y. Community Perceptions of Ecosystem Services from Homegarden-Based Urban Agriculture in Bandung City, Indonesia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10726. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310726

Saputra A, Abdoellah OS, Utama GL, Wulandari I, Mulyanto D, Suparman Y. Community Perceptions of Ecosystem Services from Homegarden-Based Urban Agriculture in Bandung City, Indonesia. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10726. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310726

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaputra, Aji, Oekan S. Abdoellah, Gemilang Lara Utama, Indri Wulandari, Dede Mulyanto, and Yusep Suparman. 2025. "Community Perceptions of Ecosystem Services from Homegarden-Based Urban Agriculture in Bandung City, Indonesia" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10726. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310726

APA StyleSaputra, A., Abdoellah, O. S., Utama, G. L., Wulandari, I., Mulyanto, D., & Suparman, Y. (2025). Community Perceptions of Ecosystem Services from Homegarden-Based Urban Agriculture in Bandung City, Indonesia. Sustainability, 17(23), 10726. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310726