Reinforcement Learning-Based Energy Management in Community Microgrids: A Comparative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Key Research Directions in Microgrid and Energy Community Management

2.1. Microgrid and Energy Storage Optimization

2.2. Grid Robustness and Resilience

2.3. Transactive Energy and Market-Based Coordination

2.4. Challenges

3. Materials and Methods

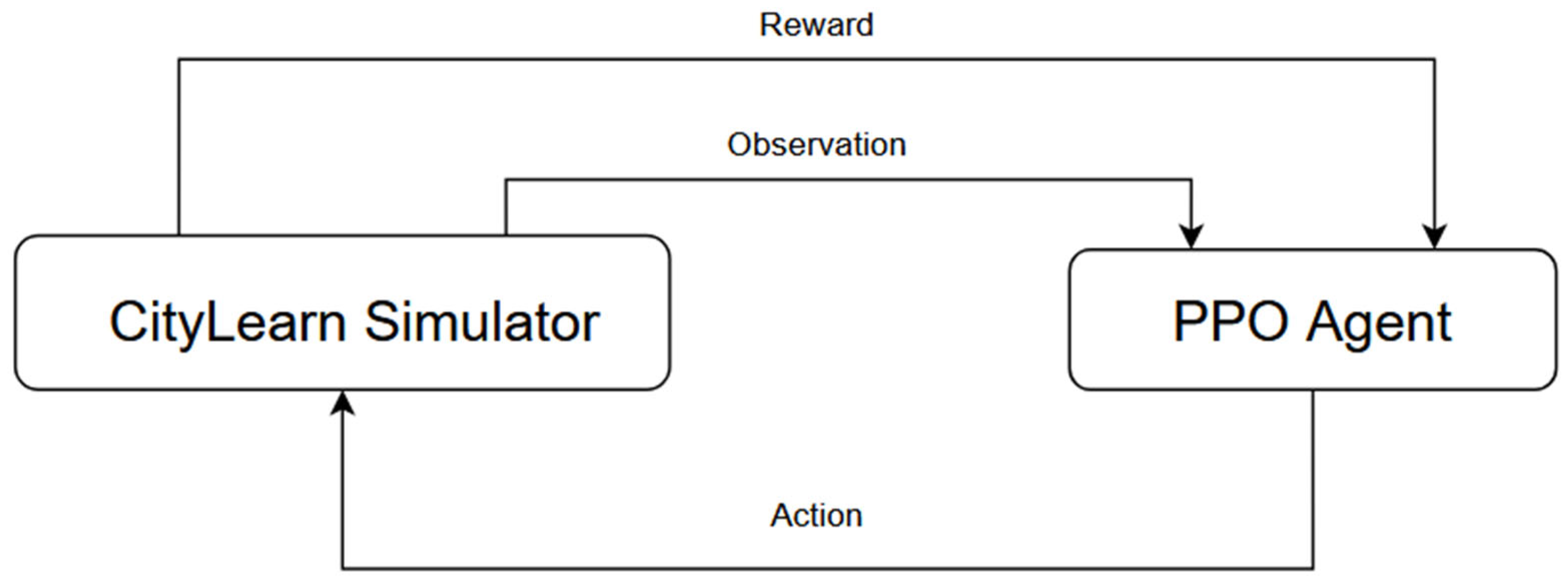

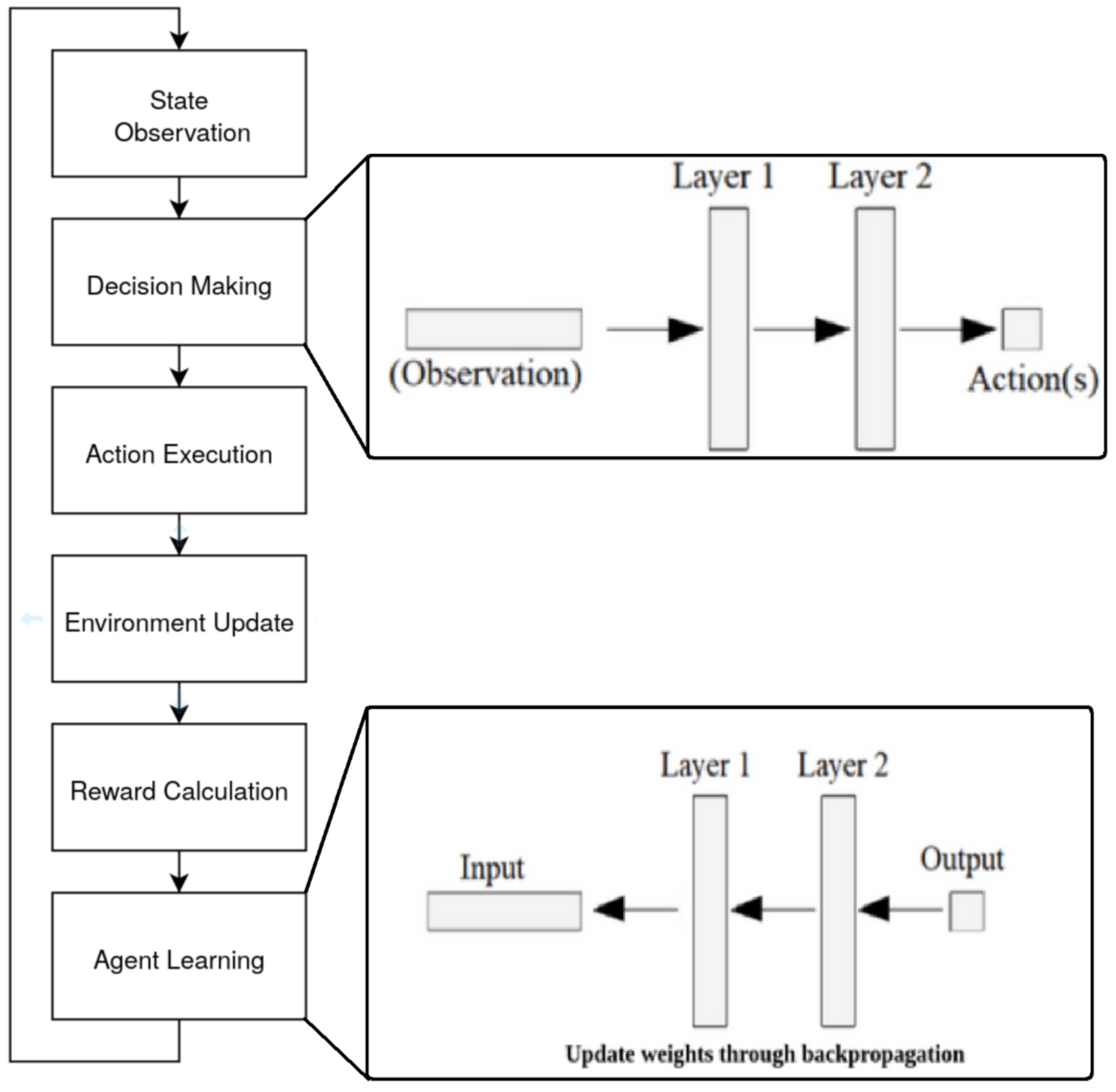

3.1. Overview of Methodology

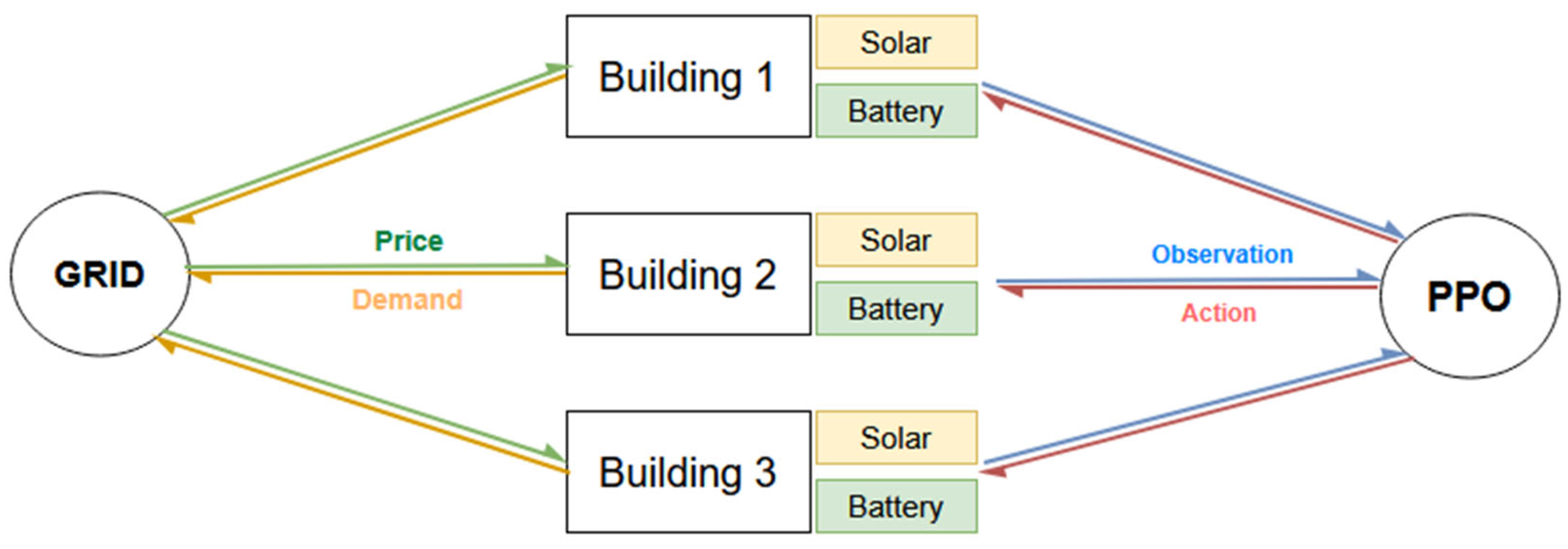

3.2. Simulation Environment

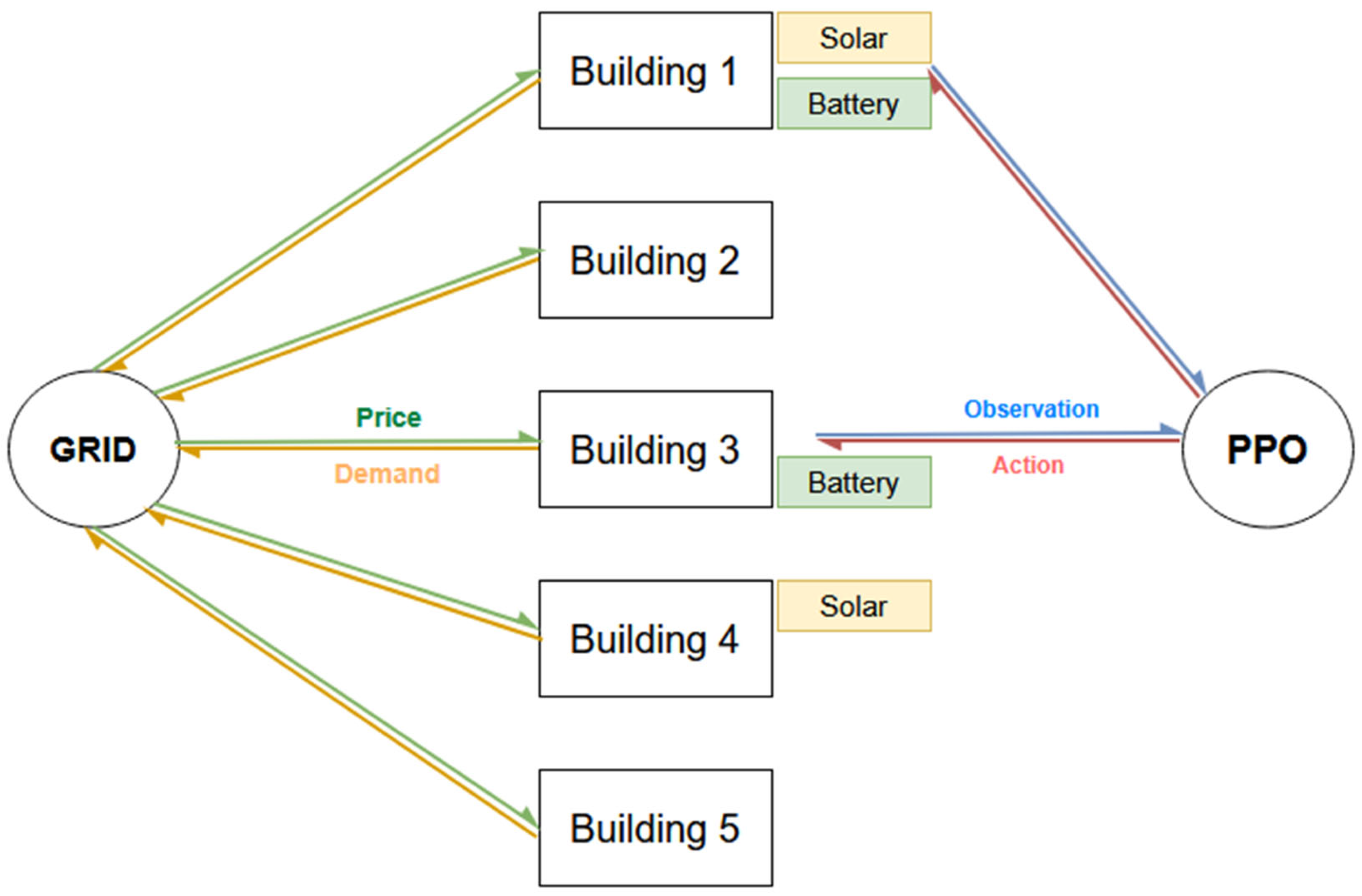

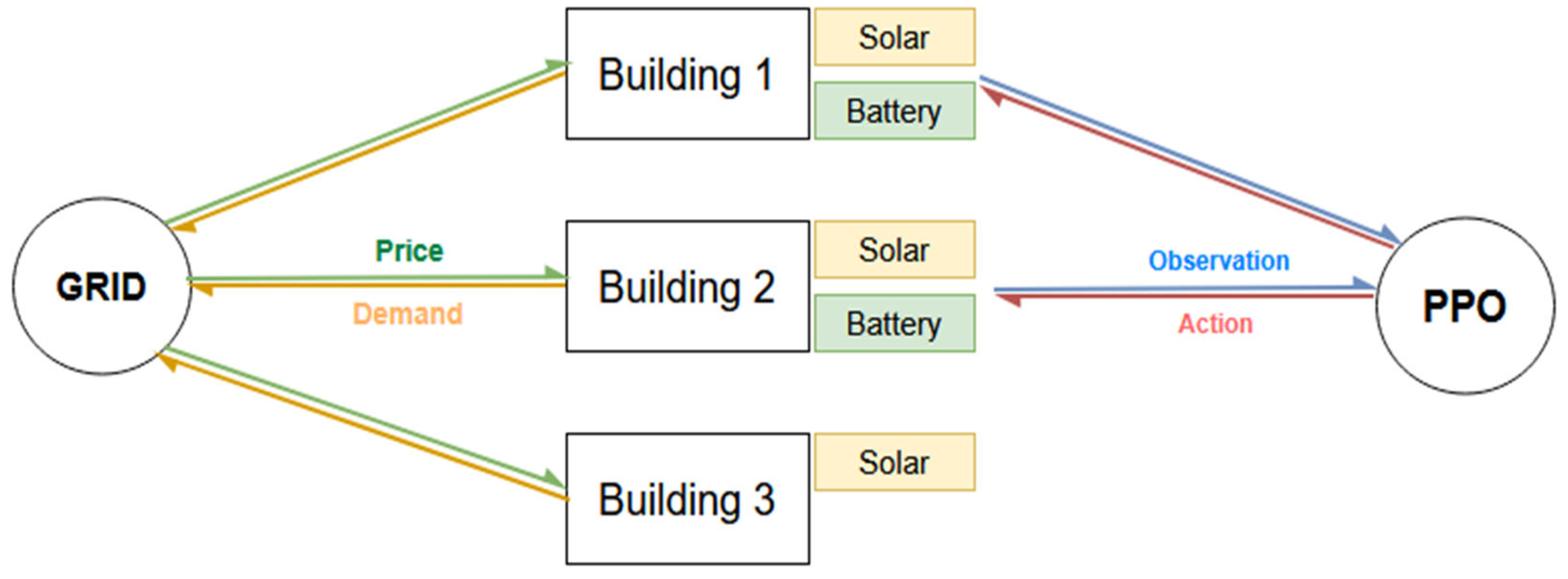

3.3. Community Configurations and Input Data

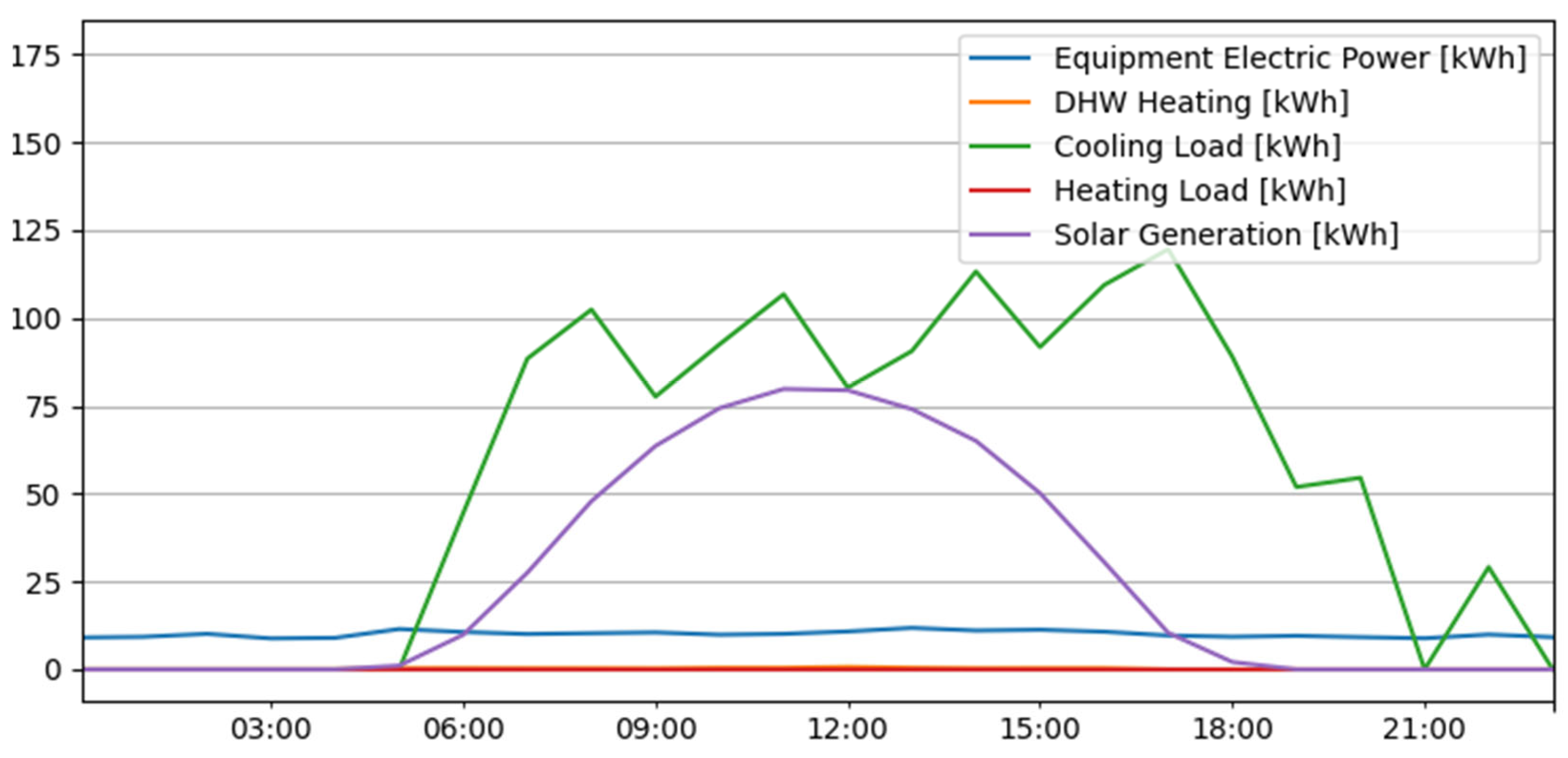

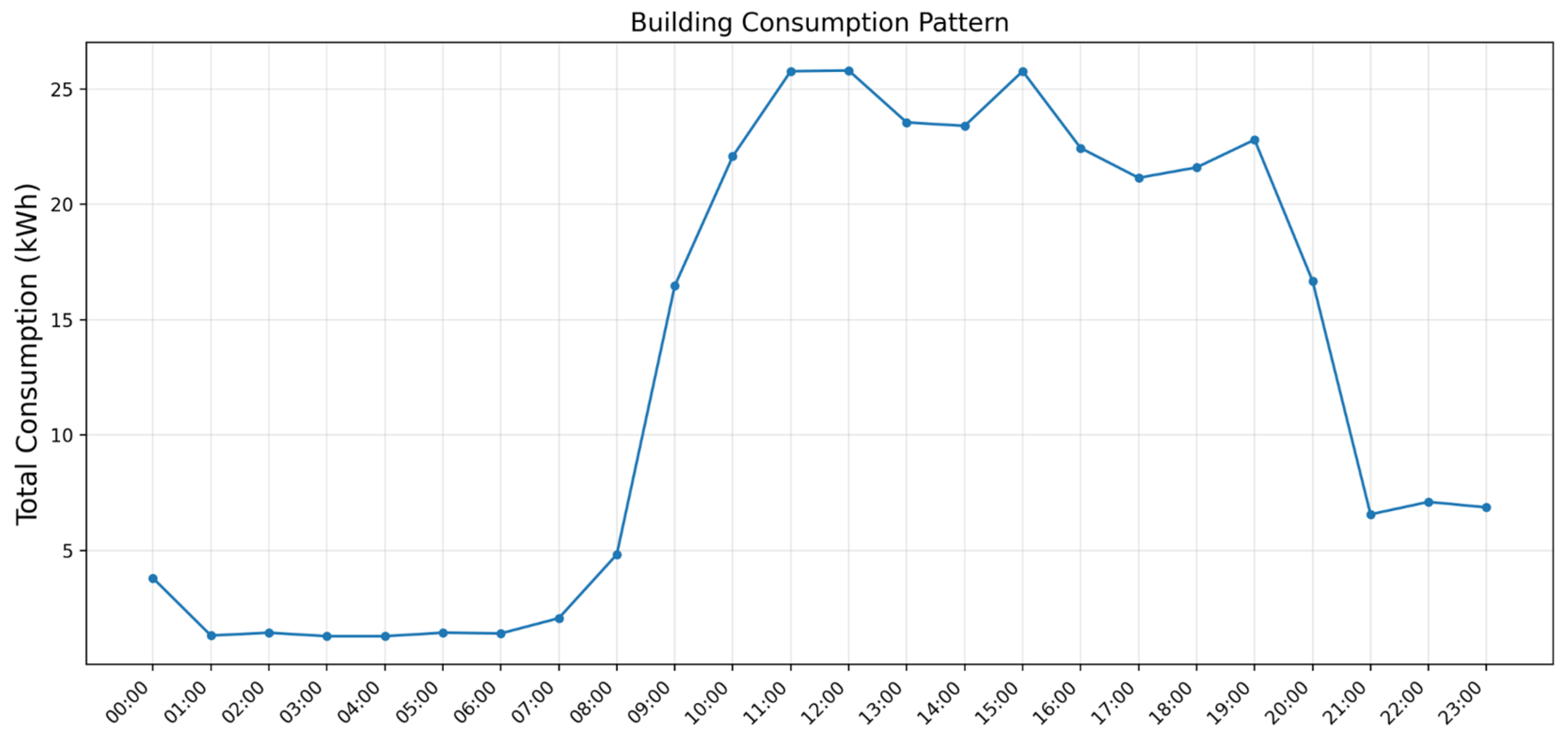

3.4. Load, PV, and Pricing Data Sources

3.5. State, Action and Reward Spaces

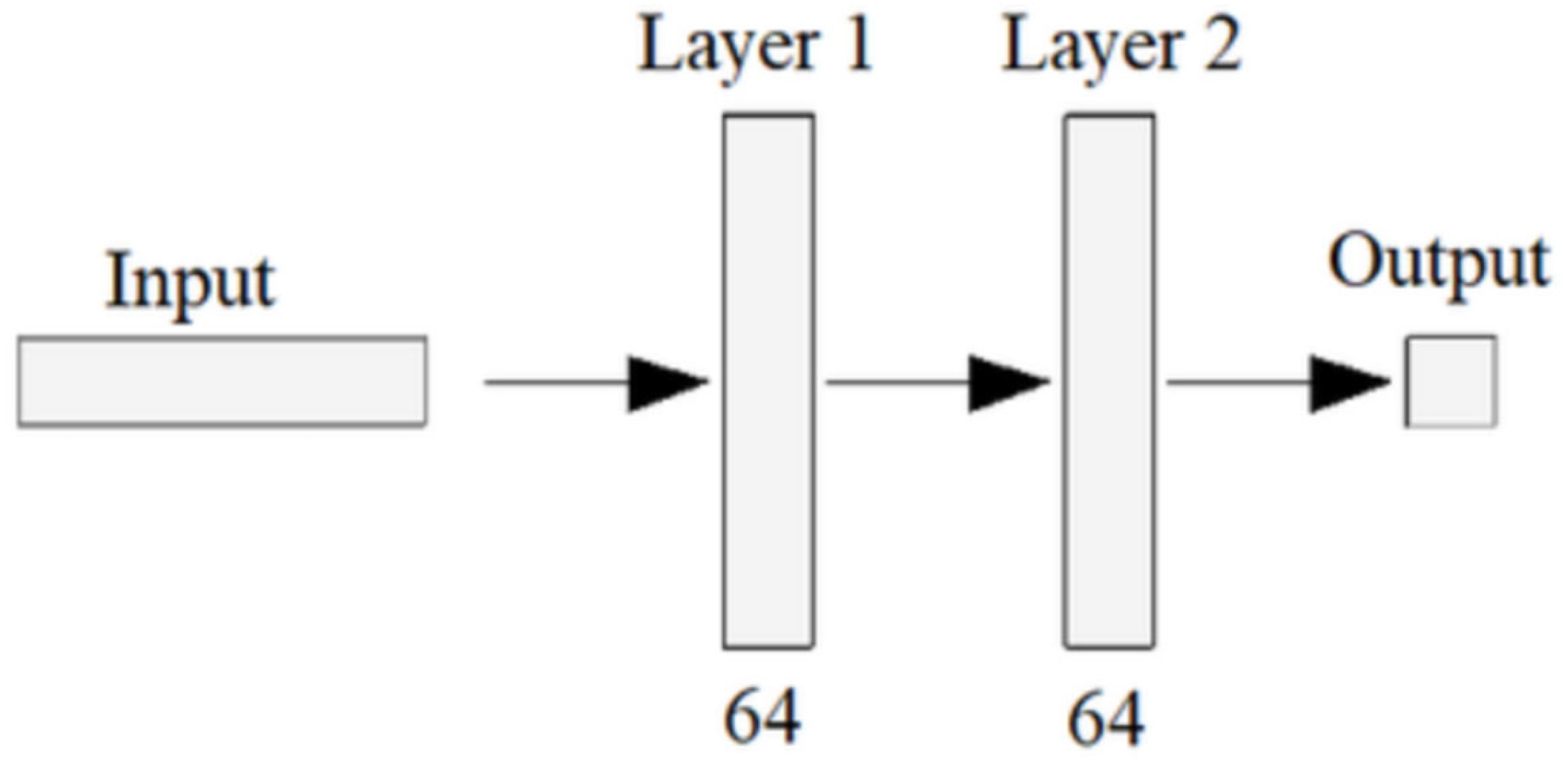

3.6. Algorithm and Training Parameters

3.7. Training Procedure and Evaluation Setup

3.8. Limitations and Assumptions

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vetter, V.; Wohlgenannt, P.; Kepplinger, P.; Eder, E. Deep Reinforcement Learning Approaches the MILP Optimum of a Multi-Energy Optimization in Energy Communities. Energies 2025, 18, 4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, G.; Guiducci, L.; Stentati, M.; Rizzo, A.; Paoletti, S. Reinforcement Learning for Energy Community Management: A European-Scale Study. Energies 2024, 17, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.; Mo, H.; Dong, D. Real-Time Energy Management Strategies for Community Microgrids. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.22931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, N.; Castro, R.; Lagarto, J. Sustainable energy trading and fair benefit allocation in renewable energy communities: A simulation model for Portugal. Util. Policy 2025, 96, 101986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Hong, P.; He, S.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, D. Multi-Layer Energy Management and Strategy Learning for Microgrids: A Proximal Policy Optimization Approach. Energies 2024, 17, 3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.; Li, X.; Sun, Y. Robust Energy Management Policies for Solar Microgrids via Reinforcement Learning. Energies 2024, 17, 2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, I.-H. Exploring the economic benefits and stability of renewable energy microgrids with controllable power sources under carbon fee and random outage scenarios. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 6017–6041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, P.; Qu, H.; Liu, N.; Zhao, K.; Xiao, C. Optimal Placement and Sizing of Distributed PV-Storage in Distribution Networks Using Cluster-Based Partitioning. Processes 2025, 13, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizki, A.; Touil, A.; Echchatbi, A.; Oucheikh, R.; Ahlaqqach, M. A Reinforcement Learning-Based Proximal Policy Optimization Approach to Solve the Economic Dispatch Problem. Eng. Proc. 2025, 97, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, S.K.; Shafei, H.; Li, L.; Aguilera, R.P.; Hossain, M.J.; Muyeen, S.M. Advancing microgrid cyber resilience: Fundamentals, trends and case study on data-driven practices. Appl. Energy 2025, 401, 126753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.S.; Ng, Y.T.; Low, J.S.C. Internet-of-Things Enabled Real-time Monitoring of Energy Efficiency on Manufacturing Shop Floors. Procedia CIRP 2017, 61, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellert, A.; Fiore, U.; Florea, A.; Chis, R.; Palmieri, F. Forecasting Electricity Consumption and Production in Smart Homes through Statistical Methods. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 76, 103426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Azim, M.I.; Lai, C.; Eicker, U. Smart home integration and distribution network optimization through transactive energy framework—A review. Appl. Energy 2025, 395, 126193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, O.; Elhajj, I.; Kayssi, A.; Chehab, A. An architecture for the Internet of Things with decentralized data and centralized control. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE/ACS 12th International Conference of Computer Systems and Applications (AICCSA), Marrakech, Morocco, 17–20 November 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Saad, W.; Mandayam, N.B.; Poor, H.V. Load Shifting in the Smart Grid: To Participate or Not? IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2016, 7, 2604–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.L.; Xing, B.; Patwardhan, A.; Hultman, N.; Zhang, H. Heterogeneous changes in electricity consumption patterns of residential distributed solar consumers due to battery storage adoption. iScience 2022, 25, 104352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, J.; Hong, T. Multi-objective optimization for optimal placement of shared battery energy storage systems in urban energy communities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 120, 106178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, I.S.F.; Perez, Y.; Suomalainen, E. Coupling small batteries and PV generation: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 126, 109835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidieh, M.; Ghassemi, M. Microgrids and Resilience: A Review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 106059–106080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Golshannavaz, S. Robust Co-planning of distributed photovoltaics and energy storage for enhancing the hosting capacity of active distribution networks. Renew. Energy 2025, 253, 123645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Xu, S.; Fang, J.; Ai, X.; Wen, J. A novel stable grand coalition for transactive multi-energy management in an integrated energy system. Appl. Energy 2025, 394, 126155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florea, A.; Berntzen, L.; Vintan, M.; Stanescu, D.; Morariu, D.; Solea, C.; Fiore, U. Prosumer networks—A key enabler of control over renewable energy resources. Renew. Energy Focus 2024, 51, 100648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulraiz, A.; Zaidi, S.S.H.; Ashraf, M.; Ali, M.; Lashab, A.; Guerrero, J.M.; Khan, B. Impact of photovoltaic ingress on the performance and stability of low voltage Grid-Connected Microgrids. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 105030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, J.P.; Yuangyai, N.; Gyawali, S.; Yuangyai, C. Blockchain-Based Smart Renewable Energy: Review of Operational and Transactional Challenges. Energies 2022, 15, 4911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.R.; Kumar, R.S.; Bajaj, M.; Kumar, B.H.; Blazek, V.; Prokop, L. A blockchain-enabled multi-agent deep reinforcement learning framework for real-time demand response in renewable energy grids. Energy Strategy Rev. 2025, 62, 101905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Tang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.-P.; Strbac, G. A Scalable Privacy-Preserving Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach for Large-Scale Peer-to-Peer Transactive Energy Trading. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 5185–5200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Eliassen, F.; Taherkordi, A.; Jacobsen, H.-A.; Chung, H.-M.; Zhang, Y. Energy Trading with Demand Response in a Community-based P2P Energy Market. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Communications, Control, and Computing Technologies for Smart Grids (SmartGridComm), Beijing, China, 21–23 October 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wu, J.; Long, C.; Ming, W. State-of-the-Art Analysis and Perspectives for Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading. Engineering 2020, 6, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François-Lavet, V.; Taralla, D.; Ernst, D.; Fonteneau, R. Deep Reinforcement Learning Solutions for Energy Microgrids Management. In Proceedings of the European Workshop on Reinforcement Learning (EWRL 2016), Barcelona, Spain, 3–4 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Canteli, J.R.; Nagy, Z. Reinforcement learning for demand response: A review of algorithms and modeling techniques. Appl. Energy 2019, 235, 1072–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisacane, O.; Severini, M.; Fagiani, M.; Squartini, S. Collaborative energy management in a micro-grid by multi-objective mathematical programming. Energy Build. 2019, 203, 109432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirinshahrakfard, P.; Suratgar, A.A.; Menhaj, M.B.; Gharehpetian, G.B. Multi-Objective Optimization of Peer-to-Peer Transactions in Arizona State University’s Microgrid by NSGA II. In Proceedings of the 2024 32nd International Conference on Electrical Engineering (ICEE), Tehran, Iran, 14–16 May 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharatovi, L.; Gantassi, R.; Masood, Z.; Choi, Y. A Multi-Objective Optimization Framework for Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading in South Korea’s Tiered Pricing System. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Canteli, J.R.; Dey, S.; Henze, G.; Nagy, Z. CityLearn: Standardizing Research in Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning for Demand Response and Urban Energy Management. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.10504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nweye, K.; Kaspar, K.; Buscemi, G.; Fonseca, T.; Pinto, G.; Ghose, D.; Nagy, Z. CityLearn v2: Energy-flexible, resilient, occupant-centric, and carbon-aware management of grid-interactive communities. J. Build. Perform. Simul. 2025, 18, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nweye, K.; Liu, B.; Stone, P.; Nagy, Z. Real-world challenges for multi-agent reinforcement learning in grid-interactive buildings. Energy AI 2022, 10, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, Z.; Vázquez-Canteli, J.R.; Dey, S.; Henze, G. The Citylearn Challenge 2021; ResearchGate: Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.; Tuovinen, M.; Ala-Juusela, M. Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) as a service in Finland: Business model and regulatory challenges. J. Energy Storage 2021, 40, 102720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga, J.; Zareipour, H.; Amjady, N. Energy Storage as a Service: Optimal sizing for Transmission Congestion Relief. Appl. Energy 2021, 298, 117095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Luther, M.; Horan, P.; Matthews, J.; Liu, C. Technical and economic analyses of PV battery systems considering two different tariff policies. Sol. Energy 2024, 267, 112189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groote, O.; Pepermans, G.; Verboven, F. Heterogeneity in the adoption of photovoltaic systems in Flanders. Energy Econ. 2016, 59, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurwidiana, N.; Sopha, B.M.; Widyaparaga, A. Modelling Photovoltaic System Adoption for Households: A Systematic Literature Review. Evergreen 2021, 8, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, K.A.K.; Kerekes, T.; Dolara, A.; Yang, Y.; Leva, S. Performance Assessment of Mismatch Mitigation Methodologies Using Field Data in Solar Photovoltaic Systems. Electronics 2022, 11, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Fata, A.; Brignone, M.; Procopio, R.; Bracco, S.; Delfino, F.; Barbero, G.; Barilli, R. An energy management system to schedule the optimal participation to electricity markets and a statistical analysis of the bidding strategies over long time horizons. Renew. Energy 2024, 228, 120617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Schema 1 | Solar PV | Battery Storage (Capacity/Nominal Power) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Building 1 | Yes (120 kW) | Yes (140 kWh, 100 kW) | Full setup |

| Building 2 | No | No | Grid-only |

| Building 3 | No | Yes (50 kWh, 20 kW) | Battery only |

| Building 4 | Yes (40 kW) | No | PV only |

| Building 5 | Yes (25 kW) | Yes (50 kWh, 25 kW) | Full setup |

| Schema 2 | Solar PV | Battery Storage (Capacity/Nominal Power) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Building 1 | Yes (70 kW) | Yes (140 kWh, 100 kW) | Full setup |

| Building 2 | Yes (70 kW) | Yes (100 kWh, 100 kW) | Full setup |

| Building 3 | Yes (300 kW) | No | PV only |

| Schema 3 | Solar PV | Battery Storage (Capacity/Nominal Power) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Building 1 | Yes (70 kW) | Yes (140 kWh, 100 kW) | Full setup |

| Building 2 | Yes (70 kW) | Yes (100 kWh, 100 kW) | Full setup |

| Building 3 | Yes (250 kW) | Yes (150 kWh, 100 kW) | Full setup |

| Parameter Group | Parameters (with Units) | Category Description |

|---|---|---|

| Time Indicators | Month, Day type, Hour, Daylight-savings status | Encodes the temporal context for each observation, including calendar position and whether daylight-saving is active. |

| Outdoor Weather, Current Conditions | Outdoor dry-bulb temperature (°C), Outdoor relative humidity (%), Diffuse solar irradiance (W/m2), Direct solar irradiance (W/m2) | Real-time meteorological signals describing ambient thermal and solar conditions. |

| Outdoor Weather, Forecasts | Temperature forecasts: 6 h/12 h/24 h (°C); Humidity forecasts: 6 h/12 h/24 h (%); Diffuse solar forecasts: 6 h/12 h/24 h (W/m2); Direct solar forecasts: 6 h/12 h/24 h (W/m2) | Short-term weather predictions used to anticipate external loads and renewable availability. |

| Indoor Environmental State | Indoor dry-bulb temperature (°C), Indoor relative humidity (%), Unmet cooling setpoint difference (°C), Indoor temperature setpoint (°C), Temperature deviation from setpoint (°C) | Characterizes thermal comfort conditions and deviations from operational targets within the building. |

| Energy Storage State-of-Charge | Cooling storage SOC (0–1), Heating storage SOC (0–1), DHW storage SOC (0–1), Electrical storage SOC (0–1) | Fractional state-of-charge values for all storage assets, representing available flexibility. |

| Building Loads & Electricity Flows | Non-shiftable load (kWh), Solar generation (kWh), Net electricity consumption (kWh) | Core energy-flow metrics including fixed loads, on-site generation, and net grid imports. |

| Thermal Demands & Device Performance | Cooling demand (kWh), Heating demand (kWh), DHW demand (kWh), Cooling electricity use (kWh), Heating electricity use (kWh), DHW electricity use (kWh), Device efficiencies | Captures thermal service requirements, corresponding electricity use, and performance indices (COP/efficiency) for each thermal device. |

| Grid & Market Signals | Carbon intensity (kgCO2/kWh), Electricity price ($/kWh), Electricity price forecasts: 6 h/12 h/24 h ($/kWh), Power-outage indicator (0/1) | Describes external grid conditions, including pricing, decarbonization signals, and supply interruptions. |

| Hyperparameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Training steps | 400,000 | Total number of environment interactions used for training. This determines the overall training duration. |

| Learning rate | 0.0001 | Step size for gradient updates. Small values slow down convergence but also ensure gradual stable learning. |

| Gamma | 0.99 | Discount factor which controls how much future rewards influence current decisions. |

| Batch size | 64 | Number of samples used per gradient update. |

| Steps per update | 2048 | Number of environment steps collected before each policy update. |

| Epochs | 10 | Number of passes over each batch during optimization |

| GAE Lambda | 0.95 | Generalized Advantage Estimation. Trades off bias and variance in advantage computation for smoother learning. |

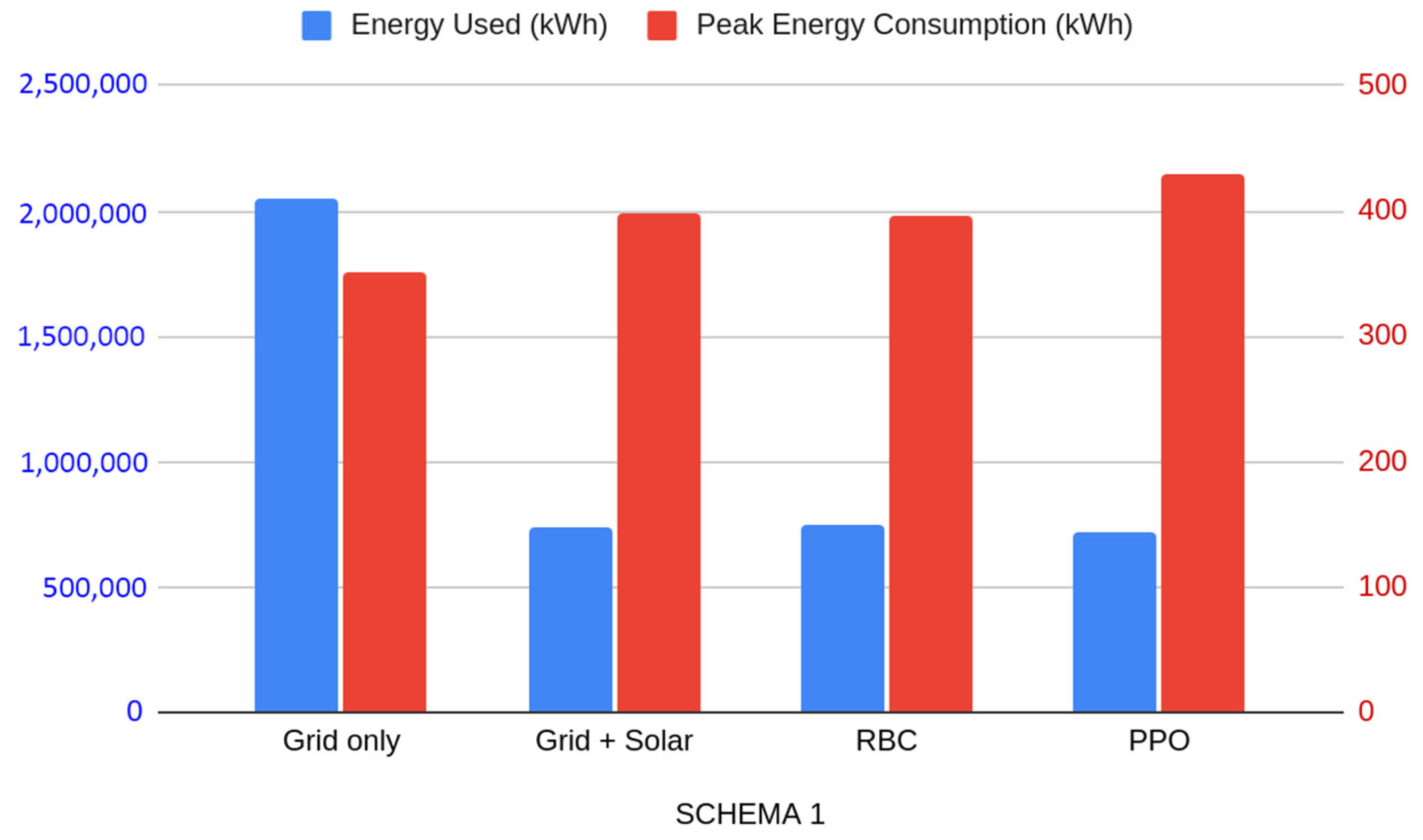

| SCHEMA 1 | Grid Only | Grid + Solar | RBC | PPO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual Cost ($) | 587,176.69 | 162,000.67 | 165,080.21 | 157,863.93 |

| Energy Used (kWh) | 2,044,709.71 | 736,365.63 | 750,364.67 | 717,566.10 |

| Carbon emissions (kg) | 1,094,800.08 | 413,185.86 | 421,040.27 | 402,635.01 |

| Peak Energy consumption (kWh) | 351.3 | 398.61 | 395.97 | 429.79 |

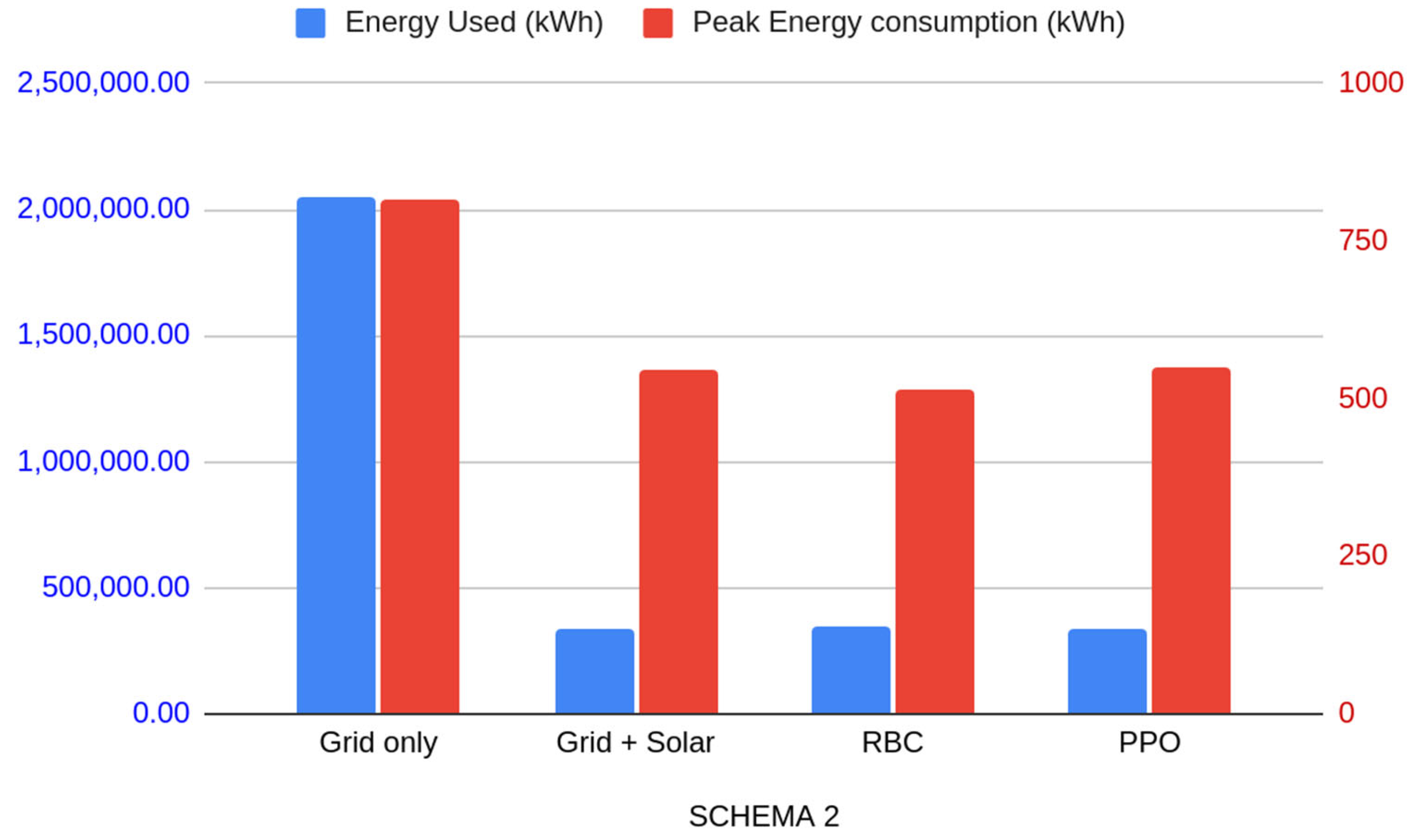

| SCHEMA 2 | Grid Only | Grid + Solar | RBC | PPO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual Cost ($) | 581,955.27 | 74,270.4 | 77,209.41 | 75,218.32 |

| Energy Used (kWh) | 2,051,007.59 | 337,594.4 | 350,952.56 | 341,902.95 |

| Carbon emissions (kg) | 1,109,990.13 | 189,428.1 | 196,924.1 | 191,845.78 |

| Peak Energy consumption (kWh) | 816.33 | 543.99 | 513.64 | 549.56 |

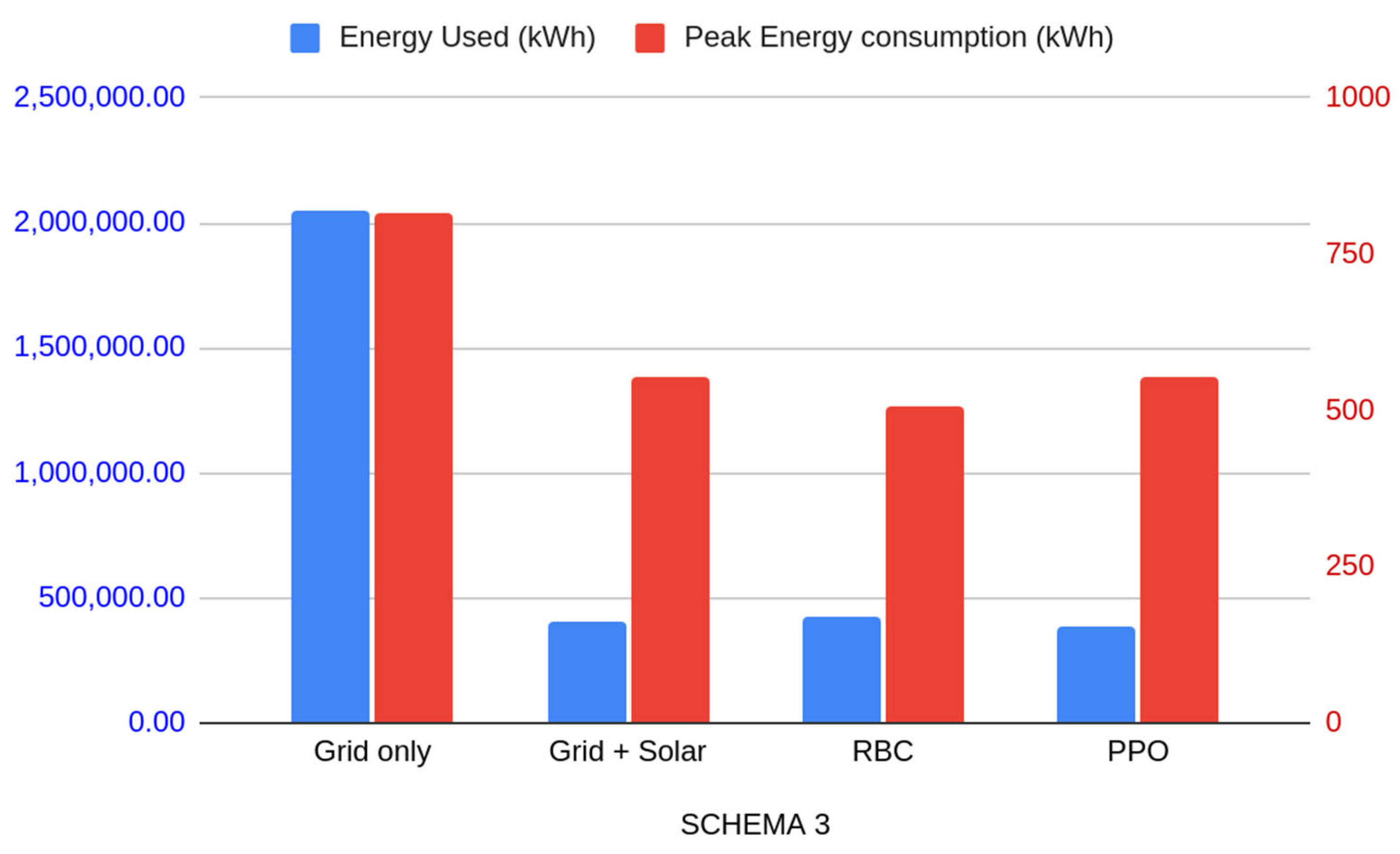

| SCHEMA 3 | Grid Only | Grid + Solar | RBC | PPO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual Cost ($) | 581,955.27 | 89,183.1 | 93,898.79 | 85,316.74 |

| Energy Used (kWh) | 2,051,007.59 | 405,378.7 | 426,811.46 | 387,801.47 |

| Carbon emissions (kg) | 1,109,990.13 | 227,463.22 | 239,490.68 | 217,602.01 |

| Peak Energy consumption (kWh) | 816.33 | 554.21 | 505.53 | 554.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moga, O.N.; Florea, A.; Solea, C.; Vintan, M. Reinforcement Learning-Based Energy Management in Community Microgrids: A Comparative Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310696

Moga ON, Florea A, Solea C, Vintan M. Reinforcement Learning-Based Energy Management in Community Microgrids: A Comparative Study. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310696

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoga, Olimpiu Nicolae, Adrian Florea, Claudiu Solea, and Maria Vintan. 2025. "Reinforcement Learning-Based Energy Management in Community Microgrids: A Comparative Study" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310696

APA StyleMoga, O. N., Florea, A., Solea, C., & Vintan, M. (2025). Reinforcement Learning-Based Energy Management in Community Microgrids: A Comparative Study. Sustainability, 17(23), 10696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310696