1. Introduction

Sustained economic growth serves as the primary driver of China’s modernization endeavors. Conducting potential growth range estimations under the low-carbon transition strategy for industrial sectors, aligned with carbon neutrality goals, is of great significance for boosting output growth in China’s industrial sectors and empowering the nation’s modernization. Rapid economic growth has long been a central objective of China’s sustainable development and macroeconomic policies [

1,

2]. In September 2020, the Chinese government explicitly proposed the “dual carbon” goals, marking the full entry of the domestic economy into a “new phase” of low-carbon transition and energy mix adjustment. It is evident that low-carbon transformation will define the core essence and guiding principle of economic growth in the coming decades. In reality, carbon emissions represent an environmental negative externality arising from economic growth. Currently, global climate change caused by excessive carbon emissions is increasingly constraining worldwide economic growth. It is noteworthy that, at the current stage, the economic growth of China’s industrial sectors remains heavily reliant on fossil energy. While carbon neutrality policies are promoting the low-carbon transition of these sectors, they also necessitate a restructuring of the engines driving economic development, making sustained growth in China’s industrial sectors more difficult. From an input–output perspective, there exist considerable differences in the input–output levels among various industrial sectors. As technology advances and public demand for environmental improvement continues to rise, the pursuit of “high output and low pollution” plays an increasingly pivotal role in the low-carbon transformation of industrial sectors. In terms of energy consumption, in general, increased energy consumption drives economic growth in industrial sectors, whereas reduced energy consumption triggers economic downturns [

3]. Therefore, the process of low-carbon transition directly exerts a direct impact on the economic growth of China’s industrial sectors.

To effectively ensure the economic growth of industrial sectors during the process of low-carbon transition, this article mainly aims to discuss the following issues. First, what impacts do fossil energy inputs and electric energy inputs have on the economic development of China’s industrial sectors at the current stage? Furthermore, within the same category of energy inputs-such as different types of fossil energy (e.g., coal and natural gas)-what specific effects do they exert on the economic development of China’s industrial sectors? Second, under the current macroeconomic structure, as the low-carbon transition in industrial sectors entails the gradual replacement of fossil energy with clean electricity, what impacts do different types of clean electricity inputs (e.g., solar power, hydropower) substituting for different fossil energy inputs (e.g., coal, natural gas) have on industrial sector economic development? Answers to these questions are crucial for effectively achieving economic growth objectives during the low-carbon transition of industrial sectors, and for facilitating the realization of a win–win outcome between carbon neutrality and economic growth.

In view of this, this paper aims to establish a theoretical framework, based on both theoretical deduction and empirical research, for measuring the economic growth potential range in the low-carbon transition of China’s industrial sectors from the perspective of energy inputs. It examines the impacts of developments in fossil energy sectors such as coal and petroleum, as well as clean energy sectors such as solar and wind power, on the outputs of other industrial sectors. Drawing on these findings, the paper further aims to optimize economic growth strategies for China’s industrial low-carbon transition from the energy input perspective. This approach not only responds to the academic question of how to achieve a win–win outcome between high-quality carbon neutrality and economic growth, but also provides decision-making support for the low-carbon transition of China’s industrial sectors.

2. Literature Review

Compared to the energy-economic characteristics of typical countries such as the United States and Germany, China faces greater challenges in achieving economic growth in its industrial sectors at this stage, primarily for the following reasons. First, time is tight, and the task is daunting. China has only 30 years from its peak carbon year to achieve carbon neutrality-a formidable challenge. Furthermore, China’s carbon emission peak is significantly higher than that of countries like the U.S. and Germany [

4,

5]. Second, the foundation is weak. Currently, major developed economies in Europe and North America have entered the post-industrialization stage. When most developed countries announced their carbon neutrality goals, their per capita GDP was substantially higher. For instance, in the peak carbon years of the U.S., Spain, and Italy, the share of the tertiary sector exceeded 70%, far exceeding China’s 70% share in 2024 (a high record) [

6]. Since the tertiary sector demands less fossil fuel consumption, a higher proportion of this sector in the peak year makes it easier to decouple economic growth from carbon emissions. Third, it must balance dual priorities. China is still in a phase of medium-to-high-speed economic growth, where sustaining economic growth remains a key development objective. Therefore, the low-carbon transition of China’s industrial sectors must simultaneously address both economic growth and climate governance targets. Notably, given that sustaining economic expansion remains a core development priority, the low-carbon transition of China’s industrial sectors must further advance two equally critical yet potentially conflicting goals: maintaining robust economic growth while fulfilling climate governance commitments.

Reducing fossil energy consumption in the process of energy mix adjustment constitutes a major trend for advancing both the low-carbon transition and further economic growth of China’s industrial sectors [

7,

8]. As the world’s largest coal producer and consumer-and coal being China’s primary source of primary energy-China’s industrial growth has long relied heavily on the extensive consumption of fossil energy [

9]. Domestic research on clean energy development has primarily focused on the low-carbon transition of the power sector, with most studies exploring development pathways for this transition [

10,

11,

12,

13]. These studies typically take carbon reduction as the core objective, and many scholars have analyzed the socioeconomic effects of the power sector’s transition toward low-carbon development [

14,

15,

16]. Regarding the low-carbon transformation of the power industry, academic consensus has been reached on several key conclusions: first, carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technology is key to achieving carbon emission reductions in the power sector [

17,

18,

19]; second, wind power and solar power will become the mainstay of the future power generation energy mix [

20,

21,

22]; third, the development of the power industry exerts a significant positive impact on economic growth [

23].

From the perspective of international research, the low-carbon economy and energy transition are also key research focuses in the field of global sustainable development. For example, Wang et al. not only illustrate the potential to reduce carbon emission costs through technological progress and institutional upgrades, but also reveal the potential economic benefits that photovoltaic (solar) and wind power-based energy transitions may yield for residents in the least developed regions, providing valuable insights and strategies for global carbon reduction initiatives [

24]. Wu et al. seek to realize economically feasible steel decarbonization by integrating global steel plant data with technological cost projections, contributing to global net-zero goals [

25]. Applying Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) models to identify win-win pathways that balance economic growth and low-carbon transition remains at the forefront of international research. Zhai et al. pioneered the “Lithium Battery Life Cycle Computable General Equilibrium (LCCGE) model,” which enables the accurate simulation of cascading impacts of alternative policies, technological approaches, and trade strategies on the economic performance of global supply chains and environmental footprints. They further designed a customized circular economy strategy tailored to their specific context [

26]. With the rapid development of artificial intelligence, some scholars have begun applying AI-based methods to research on the low-carbon transition. For instance, Li et al. proposed a framework that leverages deep learning to generate critical variables, in which a generative model is trained to produce numerous “synthetic mitigation scenarios” consistent with the Sixth Assessment Report of the IPCC [

27].

In summary, existing research has extensively explored the environmental governance effects of fossil fuel and clean energy consumption in facilitating the low-carbon transition of China’s industrial sectors. However, few studies have addressed the economic growth potential range of industrial sectors during this transition from an energy input perspective, nor have scholars adequately examined how the gradual substitution between fossil and clean energy impacts economic growth in the ongoing phase of industrial decarbonization.

To fill these gaps in the literature, this study offers the following contributions. First, while prior research has largely focused on analyzing the environmental-economic impacts of fossil and clean energy consumption through future scenario projections, this paper integrates China’s current industrial input-output levels and energy inputs into a unified analytical framework. By employing a static computable general equilibrium (CGE) model combined with constant elasticity of substitution (CES) production functions to construct sectoral nested structures, we examine how increased energy inputs affect economic growth during the low-carbon transition under existing input-output conditions. This approach offers a novel perspective for assessing the growth potential of China’s industrial decarbonization. Second, given the scarcity of research that accounts for current input-output levels, this study quantifies the economic growth potential range of China’s industrial sectors by separately increasing inputs of fossil fuel energy (coal, oil) and clean energy (solar power, wind power). The findings provide valuable policy references for economic growth during industrial low-carbon transitions across different countries.

3. Methodology

3.1. Model Framework

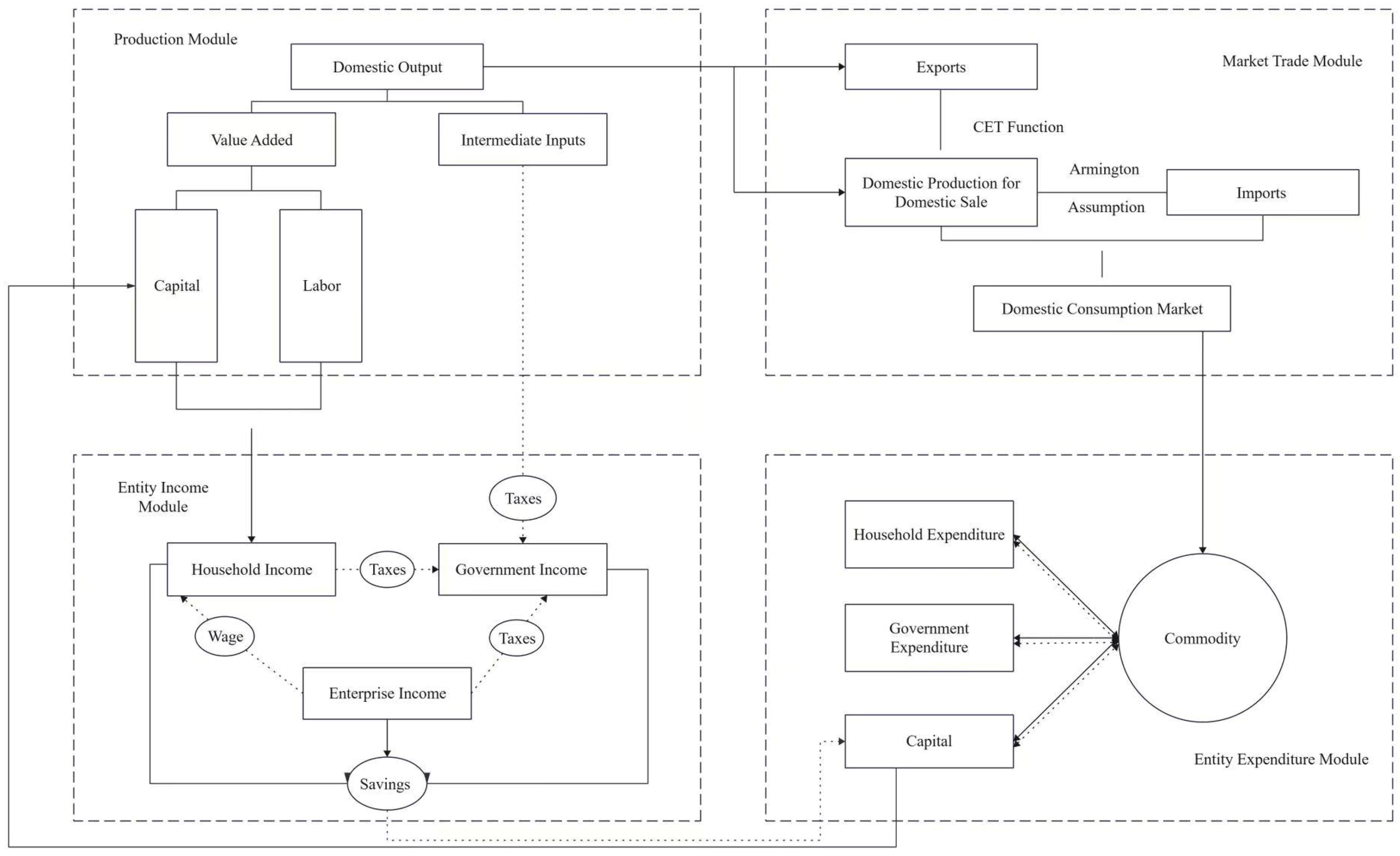

Figure 1 captures the macroeconomic structure of China as portrayed by the Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) model utilized in this study. For further details regarding the fundamental principles and core structure of the CGE model, readers are referred to the research by Jiang [

3]. This paper proposes two key modifications to the model: first, it focuses on China’s current input-output level by removing the model’s original time effect specification; second, it integrates an economic growth potential module. Given the distinct input-output linkages between fossil energy sectors (such as coal and oil) and clean energy sectors (such as solar and wind power), as well as the varying demands of other industrial sectors for different energy sources, increasing input in different energy sectors will have divergent effects on the output of other industrial sectors.

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the CGE model primarily employs economic methodologies to interconnect commodity production, consumption, and income-expenditure flows among various economic agents (including households and governments), thereby depicting China’s macroeconomic structure and simulating the macroeconomic impacts of changes in specific scenarios. In this study, the core research question focuses on how to strategically arrange the “substitution” of clean energy for fossil fuels in meeting energy demand during industrial sectors’ low-carbon transition-ensuring that sectoral output growth remains unimpaired or even enhanced-while simultaneously reducing fossil fuel consumption and boosting clean energy adoption. Accordingly, building upon China’s current input-output levels, this study quantifies output variations resulting from changes in different energy inputs by separately increasing fossil fuel and clean energy inputs in the production module shown in

Figure 1. The energy types analyzed include: coal, petroleum, natural gas, hydropower, thermal power, nuclear power, wind power and solar photovoltaic power. It should be noted that since the data in the input-output table are all value quantities, the “energy input” data referenced in this paper are also presented in value terms.

3.2. Energy Input Adjustment

It is important to note that adjustments to energy sector inputs necessitate attention to the heterogeneous impacts on the output of other industrial sectors-specifically, modifying inputs to different energy sectors will yield divergent effects on such output. Therefore, to quantify the economic growth potential of different energy sectors, this study employs the methods of increasing inputs to energy sectors by an identical value amount, thereby measuring the effects of such increases on the output of other industrial sectors. In Equation (1), KQINT represents the constant value amount of additional input to the energy sectors, where the subscript

i denotes the energy sector (including coal, oil, natural gas, wind power, hydropower, nuclear power, solar power, and thermal power, totaling eight types), and

n represents the number of energy sectors.

K0 denotes the mean proportion selected to determine the constant value of input.

3.3. Design for Calculating the Economic Growth Range

Under the scenario of additional energy input, this paper defines the economic growth potential of low-carbon transition in industrial sectors as the proportional change in the output of other industrial sectors resulting from the addition of a constant energy input. Consequently, the potential range of economic growth in this context refers to the interval of differences in output changes across industrial sectors when separately increasing one unit of fossil energy input versus one unit of electric energy input. It should be noted that since the thermal power sector is primarily dependent on fossil fuels for energy consumption, the electric energy input explicitly excludes thermal power. In Equation (2), QA

a2 represents the output value of industrial sectors after the energy input increase, QA

a1 represents the output value of industrial sectors before the energy input increase, and KQA

a represents the proportional change in the actual output value of each industrial sector per unit increase in energy input. In Equation (3), EVP

a represents the economic growth potential of low-carbon transition for industrial sectors. The subscripts max and min denote the maximum and minimum values, respectively; the subscript e denotes the hydropower, nuclear power, wind power, and solar power sectors; and the subscript f denotes the coal, oil, and natural gas sectors. EVPR represents the economic growth potential range of industrial sectors in low-carbon transition.

3.4. Data

The data used in this study are primarily derived from the 2020 149-sector input-output table published by China’s National Bureau of Statistics, the 2021 and 2024 China Statistical Yearbook, and the National Data website.

In line with the input-output balance principle and the energy consumption patterns of the respective year, the value data of the oil and natural gas industry sector were disaggregated into two distinct sectors: petroleum and natural gas. Following the same principle and the proportional consumption of various types of electricity in the corresponding year, the sector of “Production and Supply of Electricity, Heat, Gas, and Water” was disaggregated into hydropower, thermal power, nuclear power, wind power, and solar power sectors, while coal was classified as an independent sector. Based on industrial characteristics, agriculture and services were each defined as independent sectors, and the remaining secondary industries were categorized into mining, manufacturing, industry, and construction. Accordingly, the original 149 sectors in the national input-output table were reclassified into 14 sectors, with the detailed classification results presented in

Table 1.

4. Result Analysis

4.1. Increasing Energy Input

This study presents the changes in industrial sector output and other economic indicators subsequent to an increase in constant-value energy input to the electricity sector, as shown in

Table 2 and

Table 3, respectively. Overall, increasing energy input to the solar power sector exerts the greatest potential impact on the output of China’s industrial sectors at the current stage, followed by nuclear power, wind power, hydropower, and thermal power sectors. The results indicate that nuclear power also holds significant potential to influence industrial output, which may be attributed to the high energy efficiency of nuclear energy. First, relative to other power generation technologies, nuclear power provides long-term stable output unaffected by weather or seasonal variations, a reliability that is vital for industrial production and economic activity. Second, for an equivalent installed capacity, nuclear power produces substantially more electricity than alternatives such as wind power or hydropower. Moreover, compared with wind power and hydropower, the research, development, and deployment of nuclear technologies generate stronger spillover and driving effects on high-end industrial value chains. As technology advances, it is expected that the challenges hindering the promotion and application of nuclear power will be gradually addressed.

Unlike other electricity sectors, thermal power remains primarily dependent on fossil fuels for energy consumption. Notably, increasing energy input across different electricity sectors demonstrates that the potential impact of thermal power on industrial output, GDP (Gross Domestic Product), QLS (Labor Input), and UB (Resident Welfare) is significantly lower than that of solar, wind, nuclear, and hydropower. This suggests that China’s current economic growth is no longer heavily dependent on fossil fuels.

Furthermore, increasing energy input to the electricity sector has the most significant impact on the output of the industrial sector, while its effects on the mining, manufacturing, agricultural, service, and construction sectors decrease sequentially. This variation primarily stems from differences in energy usage dependency across various sectors. For example, the industrial sector’s development requires significantly more fossil energy than the service sector.

This study analyzes the changes in industrial sector output and other economic indicators subsequent to an increase in constant-value energy input to fossil energy sectors, as detailed in

Table 4 and

Table 5, respectively. It is evident that, at the current stage, increasing energy input to the petroleum and natural gas sectors not only drives more pronounced growth in output across other industrial sectors, but also contributes to greater improvements in indicators such as GDP (Gross Domestic Product), QLS (Labor Input), and UB (Resident Welfare). In contrast, increasing energy input to the coal sector results in the smallest growth in these indicators—indicating lower economic efficiency under constant-value energy conditions compared to the petroleum and natural gas sectors. Furthermore, increasing energy input to the natural gas sector at this stage demonstrates stronger effects on boosting output in the manufacturing, industrial, construction, and service sectors, while increasing input to the petroleum sector exerts a greater impact on enhancing output in the agricultural sector and mining sector.

Empirical results indicate that the growth effect of the thermal power sector, which currently has the largest installed capacity, on China’s economic development is significantly lower than that of other power sources. In contrast, nuclear, wind, and hydropower exert relatively stronger effects on current economic growth. Under China’s carbon neutrality target, the adjustment of the energy mix in the power sector primarily centers on increasing the share of solar, wind, and nuclear power. From an economic development perspective, the low-carbon transition of the power sector will help enhance momentum for economic growth. Therefore, the ongoing structural adjustments in the power sector-aimed at achieving carbon neutrality before 2060—incorporate not only the need to address global warming but also the actual economic growth demands of China’s industrial sectors at the current stage. Furthermore, although nuclear power exhibits a higher economic growth effect compared to solar and wind power in the current context, China’s power sector strategy by 2060 prioritizes the development of solar and wind power, while assigning nuclear power a secondary role. This may be attributed to concerns such as high investment costs, radioactive contamination, and thermal pollution associated with nuclear energy.

4.2. Potential Range of Economic Growth

From the perspective of economic development patterns, the early stages of economic growth are typically driven by high consumption of fossil fuels, leading to rapid economic expansion. When economic development reaches a certain stage, the growth rate slows down gradually, driven primarily by two key factors. First, during the process of economic growth, the negative environmental externalities arising from extensive fossil energy consumption eventually constrain further economic expansion. From a sustainable development standpoint, the non-renewable characteristic of fossil fuels including coal and oil necessitates renewable energy as the primary choice for human survival and development. As a result, countries around the world have consistently advocated for increasing renewable energy consumption. However, it is important to note that as renewable energy gradually replaces fossil fuels, it can also enhance the economic growth momentum of industrial sectors.

This study presents the potential range of economic growth gains resulting from the low-carbon transition of industrial sectors, as shown in

Table 6. Overall, for the agriculture, manufacturing, industry, construction, and service sectors, replacing coal with solar power offers the greatest potential for economic growth. For the mining sector, replacing coal with wind power demonstrates the highest potential, primarily due to the fact that solar and wind power exhibit higher energy efficiency than coal. Additionally, it is worth emphasizing that in the process of low-carbon development, the agricultural sector and mining sectors should reduce their reliance on hydropower as a substitute for oil consumption, whereas the manufacturing, industry, construction, and service sectors should minimize the use of hydropower as a replacement for natural gas in energy consumption.

5. Discussion

Our research concentrates on assessing the current effects of fossil energy and electricity inputs on the development of China’s industrial sectors, and presents a coherent theoretical and methodological framework to address the problems in this work. In the

Section 5 (Discussion), we mainly address the research questions raised in the “

Section 1 (Introduction)” part.

(1) Different types of energy inputs have significantly different impacts on the economic development of China’s industrial sectors at the current stage, and this difference even exists within the same type of energy (such as coal and natural gas). As Liu and Wang proposed, China’s energy transition will promote the transfer of capital and technology from high-pollution energy fields to clean energy fields, thereby improving the quality of the energy economy [

28]. During this process, the efficiency of different energy sources and the differences in technology exist. It is easy to imagine that the differences in the efficiency of use and technology of different energies in different industries will widen. Compared with previous studies, the problem addressed in this paper may have some unique aspects, expanding on the research of previous scholars. For example, Wang and Zhang suggested that in the short term, compared to sustainable energy, oil and natural gas have more advantages as substitutes for coal [

29]. Jiang et al. calculated the impact of reducing coal input on the regional economy [

3]. Based on previous research, this paper calculates the impact of different energy inputs on regional economic development and, by comparing these impacts, quantifies the economic development potential of different energies at the current stage.

(2) Replacing fossil-based energy inputs with different types of clean electricity has different impacts on the output of industrial sectors. Relevant research results support this finding. For example, Xu et al. proposed that in the power low-carbon transformation of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area, the combination of coal power, gas power, and non-fossil power development speed is economically optimal [

30]. This study finds that when photovoltaic and wind power are chosen to replace fossil energy, the output of industrial sectors is higher. Jiang et al. pointed out that subsidies for different energies minimize the loss to the overall macroeconomy and the profits of key power-consuming sectors; therefore, in the short term, China’s power industry should prioritize the rapid development of photovoltaic and wind power [

31]. This finding also supports our research results. Our analysis suggests that replacing fossil-based energy with different types of electricity in industrial sectors leads to markedly divergent impacts on sectoral output. This interesting discovery enriches the content of the existing literature in the field of energy economics.

6. Conclusions

This study, from the perspective of energy input, employs a CGE model to characterize China’s current macroeconomic structure. By increasing energy inputs in the coal, oil, natural gas, hydropower, thermal power, nuclear power, wind power, and solar power sectors, it estimates the potential range of economic growth derived from the low-carbon transition of China’s industrial sectors. The main findings and implications are as follows.

(1) Accelerate the enhancement of clean energy efficiency. During the low-carbon transition of industrial sectors, increasing input from fossil fuels versus clean energy has significantly different effects on output growth. For instance, increasing energy input in the oil and natural gas sectors leads to substantially higher output growth in agriculture, mining, manufacturing, industry, construction, and services compared to clean energy sources such as hydropower, solar, and wind power. Therefore, it is imperative to intensify efforts to improve the energy efficiency of clean energy sources, particularly solar and wind power, to strengthen economic growth momentum during the industrial low-carbon transition.

(2) Industrial sectors should rationally adjust energy demand based on their specific characteristics. Output growth exhibits heterogeneity across sectors when increasing the input of different energy types; even for the same type of energy, its impact differs among sectors. For example, increasing energy input to the electricity sector has a diminishing effect on output in the industrial, mining, manufacturing, agricultural, services, and construction sectors, in that order. At this stage, increasing input in the natural gas sector significantly boosts output in manufacturing, industry, construction, and services, while increasing input in the oil sector has a greater effect on output in agriculture and mining. Thus, industrial sectors should prioritize energy sources with higher economic growth potential to further enhance output growth momentum.

(3) The effect of energy substitution on output growth varies across industrial sectors, depending on the alternative energy sources adopted. For instance, when solar power replaces coal, the output growth rates in agriculture, manufacturing, industry, construction, and services all reach their maximum level. Similarly, when wind power replaces coal in the mining sector, output growth is also maximized. In contrast, output growth is minimized when hydropower replaces oil in agricultural and mining sectors (reflecting the difference between non-fossil and fossil energy impacts). Similarly, when hydropower replaces natural gas in manufacturing, industry, construction, and services, sectoral output growth is also the lowest.

7. Limitations

This study concentrates on analyzing the potential range of economic growth associated with the current low-carbon transformation of industrial sectors. It fails to account for the differences in power generation capacity among various types of energy sources or the technological aspects of electricity generation. In addition, the “energy input” data mentioned in this paper are all measured in value terms.

Author Contributions

J.W.: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Formal analysis, and Supervision. X.X.: Methodology, Conceptualization, and Writing—original draft, Formal analysis. G.D.: Methodology, Conceptualization, and Writing—review. L.W.: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Conceptualization, and Writing—review and editing, Formal analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Anhui Higher Educational Project of Excellent Scientific Research and Innovation Team (2023AH010026) and Anhui Graduate Education Quality Project (2024xscx079) and Doctoral Program in Anhui University of Science and Technology (2025cx1015).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the editor and all anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments, which greatly improved the quality of the manuscript. We also appreciate the organizations that provided valuable data for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, S. Energy Consumption CO2 Emission and Sustainable Development in Chinese Industry. Econ. Res. J. 2009, 44, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, L. An Empirical Research on Industry Structure and Economic Growth. Stat. Res. 2010, 27, 79–81. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, C.; Song, Z.; Feng, Z. Haze Governance and its Economic and Social Effects: An analysis of CGE Model Based On “Coal Restricted Area” policy. China Ind. Econ. 2017, 9, 44–62. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Yang, M. Peak Carbon Emission and Carbon Neutrality: China’s Path to Energy Transition in Modernization. Econ. Probl. 2024, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Z.; Bai, K.; Chen, X. Carbon Shadow Price and Potential Reduction in the Countries along the Belt and Road. Soc. Sci. Int. 2022, 1, 133–143+199. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, X.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, J. Research on the pathway for China’s transformation and development toward carbon neutrality. J. Beijing Inst. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 24, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Z.; Niu, D.; Li, W.; Wu, G.; Yang, X.; Sun, L. Improving the energy efficiency of China: An analysis considering clean energy and fossil energy resources. Energy 2022, 259, 124950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shang, P.; He, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D. Can China Achieve the 2020 and 2030 Carbon Intensity Targets through Energy Structure Adjustment? Energies 2018, 11, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Deng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Duan, L.; Hao, J.; Jiang, J. Air pollutant emissions from coal-fired power plants in China over the past two decades. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 741, 140326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, K.; Cui, X.; Zhou, J. Study on medium and long-term low-carbon development pathway of China’s power sector. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2018, 28, 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Yu, B.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, F.; Zhao, G.; Tang, B. The Path of Low-Carbon Transformation in China’s Power Sector Under the Vision of Carbon Neutrality. Chin. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 13, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Shi, D.; Pei, Q. Low-carbon transformation of China’s energy in 2015–2050: Renewable energy development and feasible path. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2018, 28, 8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, X.; Zhang, D.; Geng, Y.; Tian, L.; Fan, Y.; Chen, W. Research on the pathway and policies for China’s energy and economy transformation toward carbon neutrality. J. Manag. World 2022, 38, 35–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, K.; Xiang, P.; He, C.; Feng, S.; Liu, C.; Tan, X.; Chen, S.; Dai, C.; Deng, L. Impact Analysis of Zero Carbon Emission Power Generation on China’s Industrial Sector Distribution. J. Glob. Energy Interconnect. 2021, 4, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Xu, H.; Ren, S.; Cheng, B.; Zhao, D. Assessment of low-carbon transition path of power in GBA based on the CGE Model. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2021, 31, 90–104. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Q.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Pang, J.; Jin, J. The impacts of carbon tax on China’s macro-economy and the development of renewable energy power generation technology: Based on CGE model with disaggregation in the electric power sector. China Environ. Sci. 2020, 40, 3672–3682. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Yuan, Y.; Li, Z. Mapping the characteristics and sensitivities of China’s low-carbon energy supply in 2050. J. Tsinghua Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 2022, 62, 802–809. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Zhu, G. Analysis of Solutions to the Energy Transition, from the Perspective of “Carbon-Peak and Carbon-Neutralization”. Nanjing J. Soc. Sci. 2021, 12, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H. China’s energy transformation under the targets of peaking carbon emissions and carbon neutral. Int. Pet. Econ. 2021, 29, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, S. Environmental impact assessment of energy and power system transformation in China. Resour. Sci. 2023, 45, 1830–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kong, L. Developing Solar and Wind Power Generation Technology to Accelerate China’s Energy Transformation. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2019, 34, 426–433. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Ren, C.; Liang, Q. Economy-wide impacts of geopolitical turmoil on China’s energy environment and its countermeasures. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2023, 33, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Liu, S.; Hu, A. Effect of electricity development on China’s economic growth and its regional difference. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2016, 26, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Tanaka, K.; Ciais, P.; Penuelas, J.; Balkanski, Y.; Sardans, J.; Hauglustaine, D.; Liu, W.; Xing, X.; et al. Accelerating the energy transition towards photovoltaic and wind in China. Nature 2023, 619, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Meng, J.; Liang, X.; Sun, L.; Coffman, D.; Kontoleon, A.; Guan, D. Technological pathways for cost-effective steel decarbonization. Nature 2025, 647, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, M.; Wu, Y.; Tian, S.; Yuan, H.; Li, B.; Luo, X.; Huang, G.; Fu, Y.; Zhu, M.; Gu, Y.; et al. A circular economy approach for the global lithium-ion battery supply chain. Nature 2025, 646, 1114–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Zhu, R.; McJeon, H.; Byers, E.; Zhou, P.; Ou, Y. Using deep learning to generate key variables in global mitigation scenarios. Nat. Clim. Change 2025, 15, 760–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wang, Z. Is It Reasonable for China to Promote “Energy Transition” Now? An Empirical Study on the Substitution-Complementation Relationship among Energy Resources. China Soft Sci. 2019, 8, 14–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, X. Modelling sustainable energy transitions. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2020, 30, 74–82. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Wang, P.; Ren, S.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, D. Research on the speed control strategy of low carbon power transition based on CGE model-take the GBA as an example. Clim. Change Res. 2022, 18, 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Yang, Q.; Dong, K. Socio-economic, energy, and environmental effects of low-carbon transition policies on China’s power industry. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2022, 32, 30–40. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).