1. Introduction

In an era of increasing global environmental discourse, there is a growing collective emphasis on living in greater harmony with the natural world. This shift in awareness emphasizes practical stewardship, minimizing pollution, promoting waste recycling, and utilizing resources more efficiently to create a cleaner, healthier living environment for both current and future generations [

1]. This philosophy has catalyzed a significant trend across industries, characterized by eco-innovation in the business and construction sectors [

2]. This approach focuses on creating products, services, and processes that support sustainable development, create competitive advantages, and reduce negative environmental impacts [

3]. Concurrently, environmental management strategies have gained prominence, emphasizing material efficiency and accelerating technologies that drive innovation and stimulate responsible investment [

4].

The construction industry holds particular significance in this transition. As a major consumer of resources, its choices, from the selection of building materials to project execution, have a direct impact on waste generation and energy consumption. Thus, the industry is uniquely positioned to champion practices that support material efficiency and sustainable substitutes, contributing to a more circular economy [

3,

5].

However, Thailand’s business, tourism, and construction industries are currently facing a slowdown in growth [

6]. This is driven by rising raw material costs and a labor shortage in quantity and quality [

7]. The industry’s reliance on unskilled labor often results in output value below wage costs. Furthermore, raw materials and labor costs constitute approximately 80% of the total production cost for construction contractors. This situation is further compounded by a slowdown in the real estate sector due to stricter loan-to-value (LTV) regulations [

8], economic and political uncertainties, and the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic [

9], resulting in a noticeable deceleration in both industries. Household debt remains one of the biggest economic hurdles, with household debt to gross domestic product (GDP) at 86.8% as of June 2025, one of the highest in Asia [

10].

The construction materials industry, encompassing cement, steel, concrete, and glass, is a cornerstone of the Thai economy [

11]. The residential sector accounted for 35.7% of the total real estate market value in 2024 [

12]. Moreover, according to the Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council (NESDC), the construction and real estate sector collectively contributed approximately 6.5% to Thailand’s GDP in 2023, a significant share of the national economic output. The growth of this sector remains intrinsically linked to the performance of the real estate market. To better align with global sustainability trends and enhance competitiveness, Thai construction material entrepreneurs have increasingly invested in research and development, adopting advanced technologies such as industrial IoT [

13] and process automation to improve efficiency and production, while reducing costs and minimizing environmental impact [

14]. A key outcome of this innovation drive is the development of ‘eco-friendly construction materials’ [

15], including low-carbon cement and recycled aggregates, positioning the industry as a critical enabler of sustainable development [

16].

Modern buyers place greater importance on the location, security, and connectivity of a property, as well as its sustainability [

17]. Features such as energy efficiency and the use of eco-friendly materials are becoming increasingly important when purchasing a home [

15,

18]. Moreover, Shen et al. [

19] reported that developers are under pressure to implement sustainable green building practices while reducing carbon emissions and complying with Thailand’s Taxonomy Phase 2 environmental, social, and governance (ESG) framework. In such an environment, marketing and branding efforts will be crucial for establishing a reliable image and reassuring customers of a commitment, thereby inspiring consumer interest [

20].

Despite rebounding from the post-pandemic slump, the real estate sector in Bangkok faces its first-ever structural crisis in 2025 [

7]. Home loan growth is expected to turn negative for the first time due to a massive oversupply, poor consumer purchasing power, and stricter bank lending policies. The downturn, which experts say is worse than the pandemic, began in the low-end housing market but is now spreading to mid- and high-end housing. Experts also say price wars could ensue as property’s long-term value is destroyed, eroding homeowners’ wealth and threatening to undermine the broader economy. As such, the Bank of Thailand (BOT) [

21] has relaxed its LTV rule on new mortgage loans for a limited period from May 2025 to 1 July 2026, extending a lifeline to ailing parts of the Thai economy.

In the context of a developing country progressing towards future growth, Thailand has an increasingly strong and sustained demand for housing, with its main urban center being Bangkok. Thus, this research aims to examine the factors influencing the decision to purchase green housing [

22], particularly the impact of marketing communication (MC), environmental awareness (EA), and service quality (SQY) on home purchase intention (PI) [

23]. The results of this study will help businesses refine their marketing strategies, gain a deeper understanding of consumer needs, and ultimately establish a competitive edge in the growing market for green housing.

However, despite the growing global demand for sustainable housing, a significant research gap persists in the Thai context. While previous studies have often examined factors such as marketing communication, service quality, and environmental awareness in isolation or within different cultural contexts, there is a lack of integrated models that simultaneously examine how these factors interact to drive purchase intention. This study aims to fill this gap by developing and validating a comprehensive structural equation model (SEM) that elucidates the complex interrelationships between these constructs.

The primary objective of this research is to identify and validate the determinants of sustainable eco-friendly housing purchase intention (PI) among consumers in Bangkok, Thailand. Specifically, the study pursues the following research objectives (ROs):

RO1: To examine the direct effect (DE) of Marketing Communication (MC) on PI.

RO2: To investigate the direct effect (DE) of Service Quality (SQY) on PI.

RO3: To analyze the direct effect (DE) of Environmental Awareness (EA) on PI.

RO4: To develop and validate an SEM that predicts sustainable eco-friendly housing PI based on these three key constructs.

These objectives are operationalized through the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1: What is the DE of MC on the sustainable eco-friendly housing PI in Thailand?

RQ2: What is the DE of SQY on the sustainable eco-friendly housing PI in Thailand?

RQ3: What is the DE of EA on the sustainable eco-friendly housing PI in Thailand?

RQ4: To what extent can the integrated MC, SQY, and EA model explain the variance in sustainable eco-friendly housing PI in Thailand?

By addressing these questions, this study provides much-needed empirical evidence and a strategic framework for understanding the Thai sustainable housing market.

3. Materials and Methods

The present study adopted a quantitative, cross-sectional research approach to create a Structural Equation Model (SEM) explaining the sustainable eco-friendly housing PI among consumers in Thailand. A structured questionnaire and a sample of potential homebuyers were utilized in the study. Bangkok, Thailand, was selected as the study area because it is home to a dynamic real estate market and urban sustainability initiatives. While cross-sectional data provide valuable insights into the formation of intentions, causal relationships cannot be inferred from them. Therefore, future longitudinal research is recommended.

Further, the questionnaire included a consumer preferences section, which elicited information on the individuals involved in the decision-making process, the time of purchase, location and price preferences, and attitudes toward the importance of various eco-friendly features (rated on a 5-point Likert scale).

3.1. Conceptual Framework

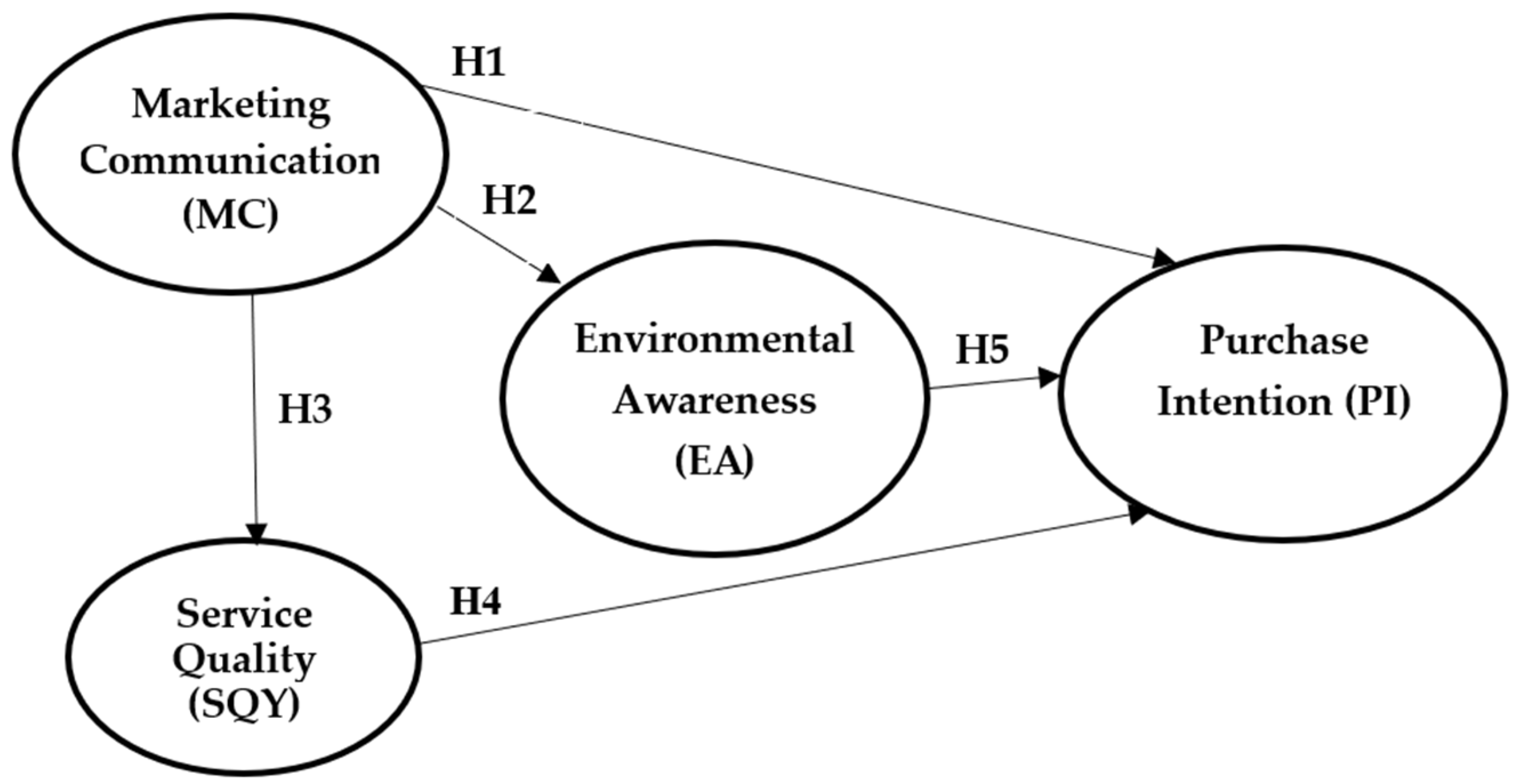

This conceptual framework (

Figure 1) postulates that three latent constructs, including marketing communication (MC), environmental awareness (EA), and service quality (SQY), have a direct and positive influence on consumers’ purchase intention (PI) in the sustainable housing market in Bangkok. The framework was developed based on an integrative literature review and verified by three academic experts in consumer behavior and green marketing to ensure that the constructs aligned with theory and fit within the contextual setting.

3.2. Population and Sampling

The target population consisted of potential homebuyers who had registered interest in or inquired about purchasing sustainable, eco-friendly homes in the Bangkok Metropolitan Region (BMR). This population segment was chosen because it reflects latent demand and awareness relevant to green housing adoption [

22,

53]. Bangkok was selected due to its high urban density and environmental initiatives. However, it is acknowledged that this approach limits the generalizability of the findings to the broader population of mainstream buyers who lack pre-existing interest.

3.3. Data Collection and Ethical Considerations

Data were collected in April and May 2025 using a mixed-mode approach, which combined structured face-to-face interviews and online surveys to enhance coverage and reduce sampling bias. Respondents were screened for inclusion criteria and provided informed consent prior to participation.

For in-person interviews, written consent was obtained under the authority of the Faculty of Hospitality Industry, Kasetsart University. For online participation, electronic consent was secured via Google Forms (“Yes, I agree to participate”). Respondents declining consent were automatically excluded.

All participants were informed of the study’s purpose, assured of anonymity, and reminded of their rights to voluntary participation. No identifying information was collected. Ethical approval was granted by the Kasetsart University Research Ethics Committee (KUREC) (Exemption No. KUREC-KPS68/109, 18 August 2025). The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision) and the NRCT Guidelines for Behavioral and Social Science Research [

54,

55].

3.4. Sample Size Determination

The sample size was determined according to SEM guidelines. According to Legate et al. [

56], an adequate SEM sample should comprise between 10 and 20 respondents per observed variable. With 16 observed indicators, a minimum of 320 respondents was required. The study achieved this target (n = 320), ensuring statistical power for model estimation and stable covariance structures. A priori power analysis (G*Power 3.1) confirmed sufficient sensitivity to detect medium effect sizes (f

2 = 0.15, α = 0.05, power = 0.95).

3.5. Sampling Technique

A multi-stage sampling strategy was applied to enhance representativeness and control for district-level variation (

Table 1).

Stage 1: Random Selection

All 50 Bangkok districts were assigned equal selection probability. Ten districts were randomly selected using a lottery method, with proportional allocation based on population size.

Stage 2: Purposive Screening

Within selected districts, potential respondents were screened using the qualifying question:

“Have you previously registered interest in purchasing an eco-friendly home?” (☐ Yes ☐ No)

Only “Yes” responses were included. This ensured that all participants were genuine potential buyers, not general residents.

3.6. Research Instrument and Measurement

Data were collected via a six-section structured questionnaire. Constructs were measured using five-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The original English questionnaire was translated into Thai using the DeepSeek V-3 AI model. This initial translation was then thoroughly reviewed and refined by a native English-speaking academic editor to ensure conceptual equivalence, linguistic accuracy, and contextual appropriateness. The instrument underwent pilot testing with 30 respondents for clarity, item comprehension, and scale reliability prior to full deployment (Cronbach’s α > 0.80 for all constructs).

The instrument underwent pilot testing with 30 respondents for clarity, item comprehension, and scale reliability prior to full deployment (Cronbach’s α > 0.80 for all constructs).

Section 1: Demographic variables (gender, age, marital status, education, income, occupation, housing type, living arrangement).

Section 2: Marketing Communication (MC)—5 items adapted from Mocanu and Szkal [

34] and Armstrong et al. [

31]; reliability α = 0.86.

Section 3: Service Quality (SQY)—5 items (tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, empathy); α = 0.87 [

53].

Section 4: Environmental Awareness (EA)—3 items reflecting cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions [

46,

48]; α = 0.89.

Section 5: Purchase Intention (PI)—3 items (satisfaction, trust, word-of-mouth intention) [

50]; α = 0.88.

3.7. Data Analysis Strategy

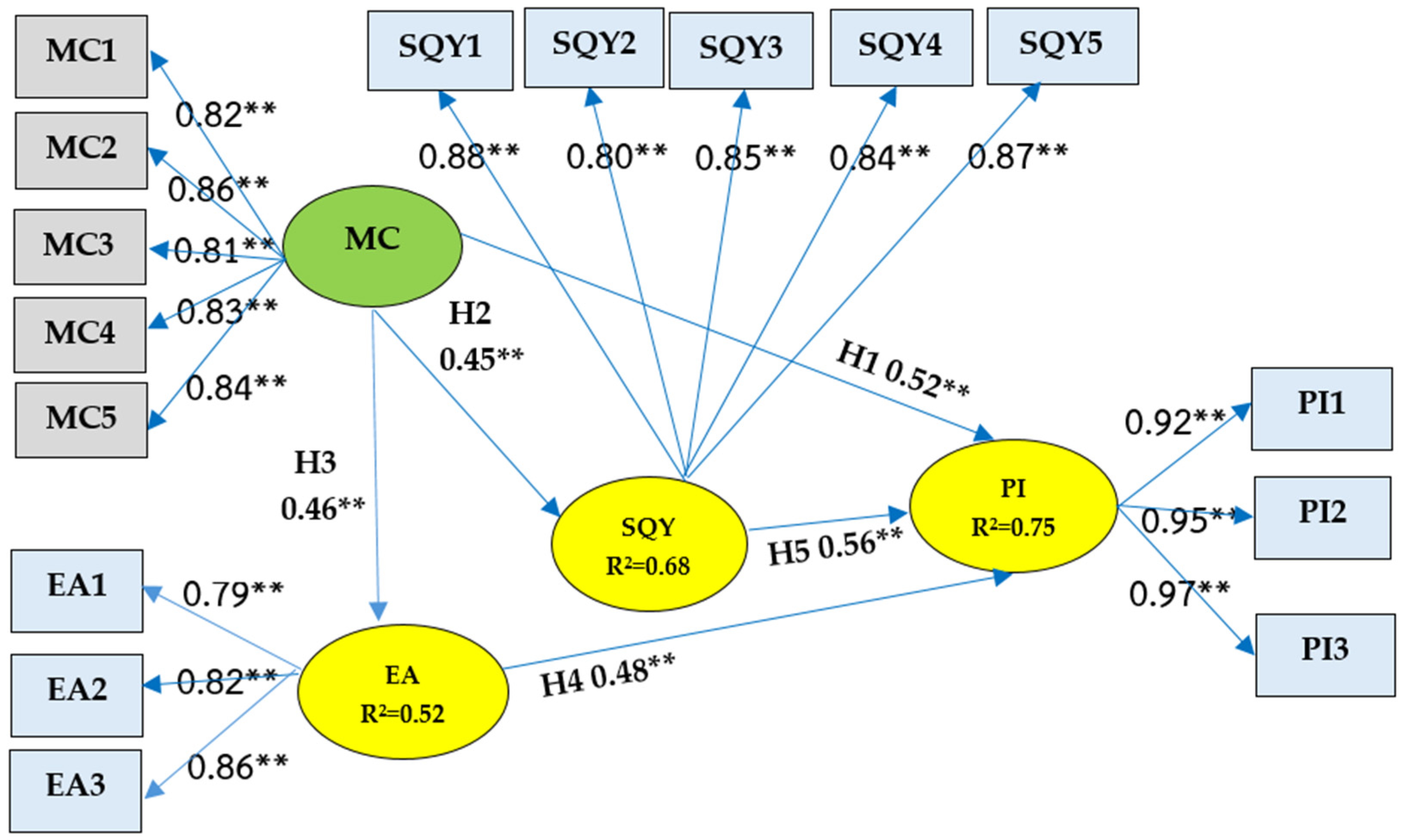

The normality of the data was assessed prior to SEM analysis. The skewness and kurtosis values for all observed variables fell within the acceptable range of ±2, indicating no severe departure from univariate normality. Data analysis followed a two-step SEM approach using LISREL 9.10.

3.7.1. Step 1: Measurement Model Validation

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to assess construct reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Composite reliability (CR > 0.7), average variance extracted (AVE > 0.5), and Fornell–Larcker criteria were used to verify validity [

56]. Harman’s single-factor test and variance inflation factors (VIF < 3.0) confirmed the absence of significant common method bias.

3.7.2. Step 2: SEM Assessment

The hypothesized model was tested for the DEs of MC, SQY, and EA on PI. Model fit was evaluated using χ2/df (<3.0), comparative fit index (CFI > 0.90), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI > 0.90), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < 0.08). Bootstrapping with 5000 resamples was employed to estimate standard errors and path stability, thereby enhancing the robustness of the results.

7. Theoretical and Practical Implications

From a practical standpoint, our findings offer a clear and actionable strategic roadmap for industry stakeholders:

For Developers: Making successful homes does not end at building “green” houses. This customer segment requires a new strategic orientation that:

Communicates value comprehensively: Craft multi-channel campaigns that articulate both the tangible benefits (e.g., “building materials that reduce heat by X%, leading to Y% savings on air conditioning”) and the intangible lifestyle value (e.g., “live in harmony with nature for a healthier family”) of eco-friendly features.

Operationalizes Service Excellence: Focus on the ‘Reliability’ (delivering projects on time with promised green specifications) and ‘Assurance’ (training sales staff to be knowledge experts on sustainable technologies) dimensions of SERVQUAL to build trust and reduce perceived risk.

Authentically Engages Environmental Values: Utilize “green storytelling” in show units, pursue credible third-party certifications, and provide transparent data on environmental impact to align with buyers’ values.

For policymakers, this result highlights the need to support public awareness campaigns and help develop comprehensive certification standards for environmentally friendly housing projects, thereby increasing consumer trust, reducing information asymmetry, and accelerating the market adoption of sustainable building practices.