The Potential of Zero Liquid Discharge for Sustainable Palm Oil Mill Effluent Management in Malaysia: A Techno-Economic and ESG Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Techno-Economic Assessment of ZLD Technologies

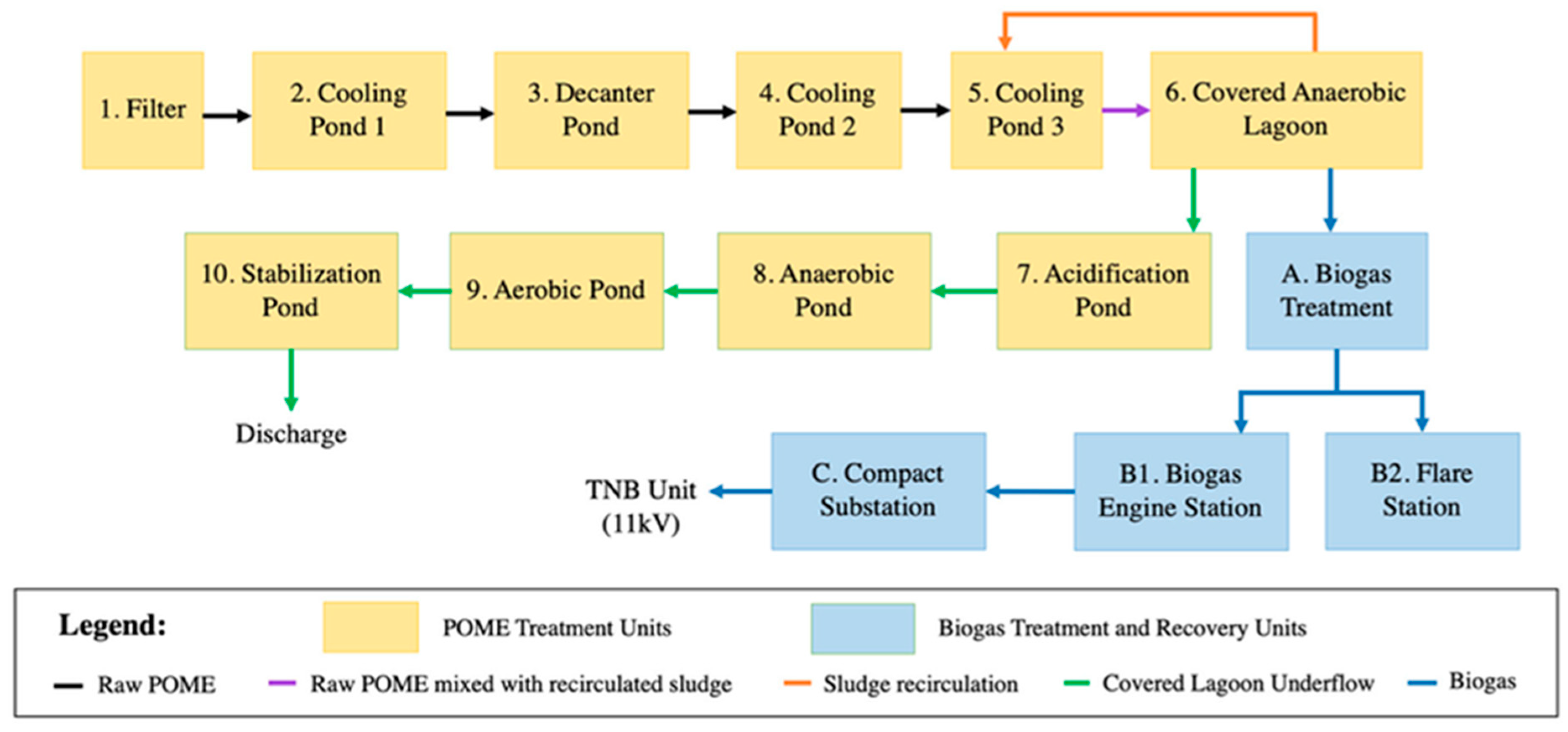

2.1. Current POME Treatment Stages

2.2. ZLD Implementation at Different POME Treatment Stages

2.2.1. Integration at Raw POME

- Required Pre-treatment and Challenges

- 2.

- Energy Demand and Operational Complexity

- 3.

- Quality and Value of Recovered Resources

2.2.2. Integration After Biological Treatment (Partially Treated POME)

- Benefits and Challenges

- 2.

- Energy Demand and Operational Complexity

- 3.

- Quality and Value of Recovered Resources

2.2.3. Integration as Post-Treatment (Highly Treated POME)

- Primary Objective

- 2.

- Specific Challenges

- 3.

- Energy Demand and Operational Complexity

- 4.

- Quality and Value of Recovered Resources

2.3. Solid Residue Consideration for ZLD System

2.4. Comparison of ZLD Technologies for POME Treatment

| Technology | Technical Performance | Drawbacks and Improvement Strategies | Economic Assessment | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reverse Osmosis (RO) & Nanofiltration (NF) | High water recovery (>90%), excellent removal of dissolved salts and organics. | Drawbacks: Severe membrane fouling from POME’s complex composition leads to flux decline and reduces lifespan. Improvements: Implement advanced pre-treatment (UF, MBR); use anti-fouling membranes. | CAPEX: Medium-High. OPEX: High (energy consumption 3–5 kWh/m3, chemical cleaning, membrane replacement). | [55] |

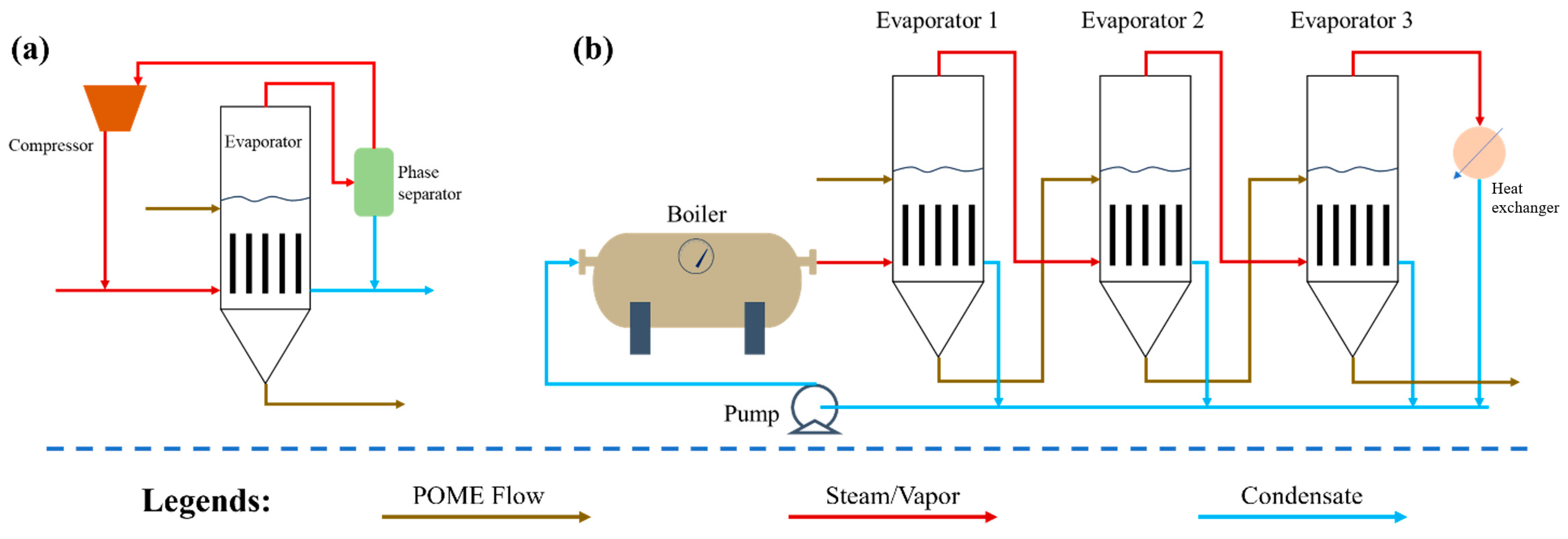

| Mechanical Vapor Recompression (MVR) | Very high water recovery (>95%), can handle high-strength POME, robust against organic load. | Drawbacks: High CAPEX and OPEX due to energy consumption; susceptible to corrosion. Improvements: Integrate with biogas energy; use corrosion-resistant materials. | CAPEX: High. OPEX: High (energy consumption 15–25 kWh/m3). May be offset by heat recovery. | [29] |

| Membrane Distillation (MD) | Effective for highly concentrated POME, high rejection of non-volatile solutes. | Drawbacks: High thermal energy demand; risk of membrane wetting. Improvements: Utilize mill’s low-grade waste heat; develop superhydrophobic membranes. | CAPEX: Medium-High. OPEX: High (Thermal energy consumption 150–250 kWh/mth). Potential for heat integration to lower cost. | [58] |

| Hybrid Systems (Anaerobic-UF-RO-MVR) | Superior performance, high water recovery (>99%), robust against varying POME composition. | Drawbacks: Very high CAPEX and operational complexity. Improvements: Implement modular designs; use smart control systems and digital twin technology for optimization. | CAPEX: Very High (complex system). OPEX: Moderate (energy is optimized, less membrane fouling). | [59] |

| Single-effect evaporator system (SEE) | Moderate water recovery per kg of steam, applicable to small mills | Drawbacks: High steam consumption, prone to fouling. Improvements: use anti-fouling agents, integration of waste heat. | CAPEX: Low to medium OPEX: High due to steam consumption. | [60] |

| Multi-effect evaporator system (MEE) | High water recovery per kg of steam, applicable to large throughput mills. | Drawbacks: Complex operation due to involvement of multiple units. Improvements: Use of smart integrated control system. | CAPEX: High OPEX: Medium due to efficient steam consumption. | [29] |

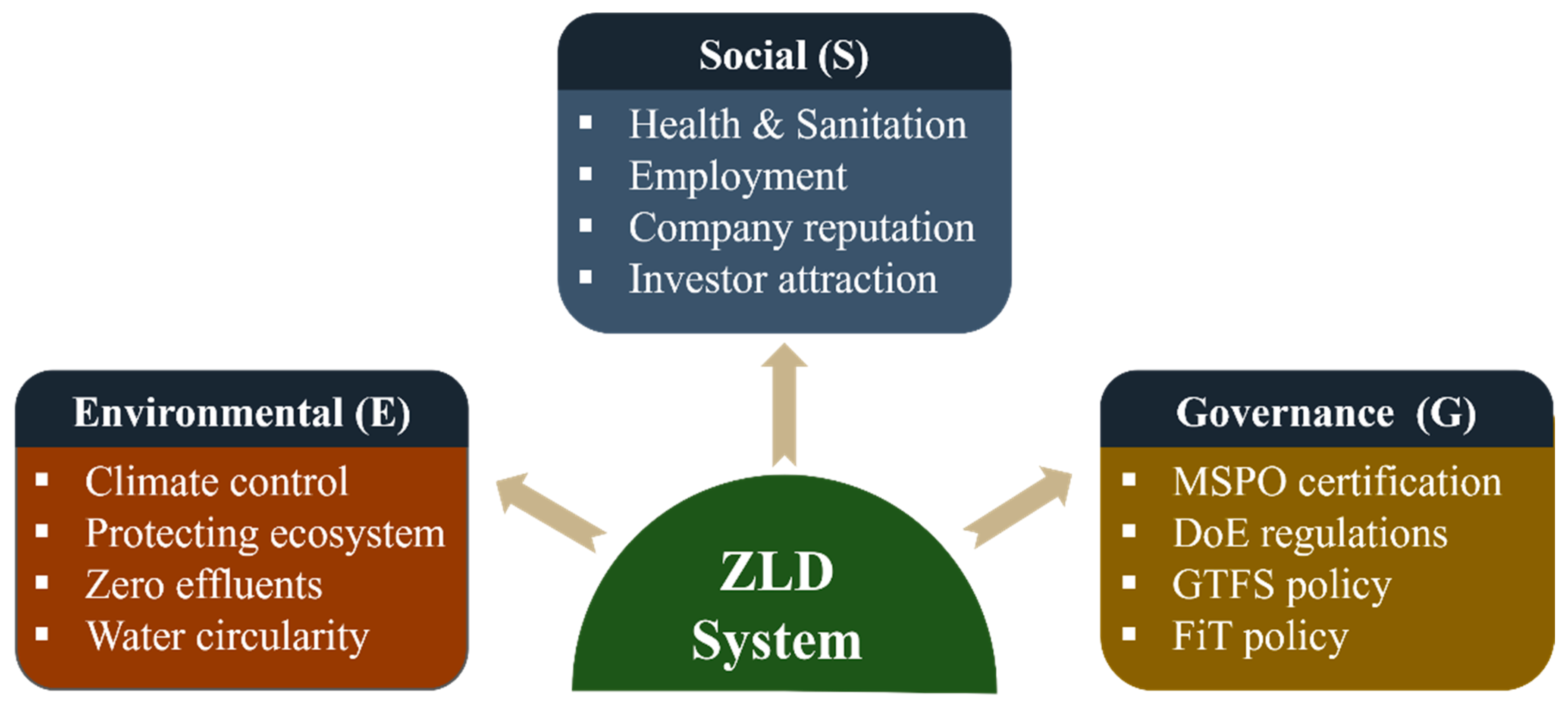

3. ESG Review of ZLD for POME for Advancing Sustainability

3.1. Environmental (E)

3.2. Social (S)

3.3. Governance (G)

3.4. Summary of ESG Review

4. Outlook and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BOD | Biochemical Oxygen Demand |

| CAPEX | Capital Expenditure |

| CH4 | Methane |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| DOE | Department of Environment (Malaysia) |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| FFB | Fresh Fruit Bunches |

| FiT | Feed-in Tariff |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| GTFS | Green Technology Financing Scheme |

| HDPE | High-Density Polyethylene |

| LCA | Life-Cycle Assessment |

| MBR | Membrane Bioreactor |

| MD | Membrane Distillation |

| MEE | Multi-Effect Evaporator |

| MF | Microfiltration |

| MSPO | Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil |

| MVR | Mechanical Vapor Recompression |

| NF | Nanofiltration |

| NPK | Nitrogen, Phosphorus, Potassium (fertilizer) |

| OPEX | Operational Expenditure |

| POME | Palm Oil Mill Effluent |

| RO | Reverse Osmosis |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal (United Nations) |

| SEE | Single-Effect Evaporator |

| TNB | Tenaga Nasional Berhad (Malaysian national grid operator) |

| TSS | Total Suspended Solids |

| UF | Ultrafiltration |

| UN | United Nations |

| VFA | Volatile Fatty Acids |

| WST 2040 | Water Sector Transformation 2040 |

| ZLD | Zero Liquid Discharge |

References

- Sabiani, N.H.M.; Alkarimiah, R.; Ayub, K.R.; Makhtar, M.M.Z.; Aziz, H.A.; Hung, Y.-T.; Wang, L.K.; Wang, M.-H.S. Treatment of Palm Oil Mill Effluent BT. In Waste Treatment in the Biotechnology, Agricultural and Food Industries; Wang, L.K., Wang, M.-H.S., Hung, Y.-T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 2, pp. 227–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mahmood, Q.; Qiu, J.-P.; Li, Y.-S.; Chang, Y.-S.; Chi, L.-N.; Li, X.-D. Zero discharge performance of an industrial pilot-scale plant treating palm oil mill effluent. Biomed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 617861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashiguchi, Y.; Zakaria, M.R.; Maeda, T.; Yusoff, M.Z.M.; Hassan, M.A.; Shirai, Y. Toxicity identification and evaluation of palm oil mill effluent and its effects on the planktonic crustacean Daphnia magna. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 710, 136277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madaki, Y.S.; Seng, L. Palm oil mill effluent (POME) from Malaysia palm oil mills: Waste or resource. Int. J. Sci. Environ. Technol. 2013, 2, 1138–1155. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M.A.; Yacob, S.; Shirai, Y.; Hung, Y.-T. Treatment of palm oil wastewaters. In Waste Treatment in the Food Processing Industry; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; pp. 101–117. [Google Scholar]

- Igwe, J.C.; Onyegbado, C.C. A review of palm oil mill effluent (POME) water treatment. Glob. J. Environ. Res. 2007, 1, 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. 2006. Available online: https://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2006gl/pdf/1_Volume1/V1_7_Ch7_Precursors_Indirect.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Yashni, G.; Al-Gheethi, A.; Mohamed, R.M.S.R.; Arifin, S.N.H.; Salleh, S.N.A.M. Conventional and advanced treatment technologies for palm oil mill effluents: A systematic literature review. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2021, 42, 1766–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z. An integrated method for palm oil mill effluent (POME) treatment for achieving zero liquid discharge—A pilot study. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 95, 148–155. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, M.S.K.; Badea, M.H.; Kambekar, M.A.A. Effluent Treatment Technologies for Zero Liquid Discharge System; The Institution of Engineers (India): Kolkata, India; p. 60.

- Wang, W.; Wu, F.; Yu, H.; Wang, X. Assessing the effectiveness of intervention policies for reclaimed water reuse in China considering multi-scenario simulations. J. Environ. Manage. 2023, 335, 117519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, S.; Baidurah, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Ismail, N.; Leh, C.P. Palm Oil Mill Effluent Treatment Processes—A Review. Processes 2021, 9, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teow, Y.H.; Takriff, M.S.; Masdar, M.S.; Mutalib, S.A.; Abdul, P.M.; Jahim, J.M.; Yaakob, Z.; Harun, S.; Yunus, M.F.M. Zero-Waste Technologies for the Sustainable Development of Oil Palm Mills. In Sustainable Technologies for the Oil Palm Industry. Latest Advances and Case Studies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 249–273. [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur, E. Towards the circular economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2013, 2, 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Panagopoulos, A. Techno-economic assessment and feasibility study of a zero liquid discharge (ZLD) desalination hybrid system in the Eastern Mediterranean. Chem. Eng. Process. Intensif. 2022, 178, 109029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Q.N.; Lau, W.J.; Jaafar, J.; Othman, M.H.D.; Yoshida, N. Membrane Technology for Valuable Resource Recovery from Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME): A Review. Membranes 2025, 15, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, G.T.; Chan, Y.J.; Lau, P.L.; Ethiraj, B.; Ghfar, A.A.; Mohammed, A.A.A.; Shahid, M.K.; Lim, J.W. Optimization of the Performances of Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME)-Based Biogas Plants Using Comparative Analysis and Response Surface Methodology. Processes 2023, 11, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumadi, J.; Kamari, A.; Wong, S.T.S. Water quality assessment and a study of current palm oil mill effluent (POME) treatment by ponding system method. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 980, 012076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muda, K.; Liew, W.L.; Kassim, M.A.; Loh, S.K. Performance evaluation of POME treatment plants. ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2006, 11, 2153–2159. [Google Scholar]

- Hamzah, M.A.F.; Jahim, J.M.; Abdul, P.M.; Asis, A.J. Investigation of temperature effect on start-up operation from anaerobic digestion of acidified palm oil mill effluent. Energies 2019, 12, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, B.J.; Lalung, J.; Ismail, N. Palm oil mill effluent (POME) treatment “Microbial communities in an anaerobic digester”: A Review. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2014, 4, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Poh, P.E.; Chong, M.F. Development of anaerobic digestion methods for palm oil mill effluent (POME) treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.J.K.; Han, T.M.; Wei, L.J.; Aun, N.C.; Amr, S.S.A. Polishing of treated palm oil mill effluent (POME) from ponding system by electrocoagulation process. Water Sci. Technol. 2016, 73, 2704–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, M.J.; Poh, P.E.; Tey, B.T.; Chan, E.S.; Chin, K.L. Biogas from palm oil mill effluent (POME): Opportunities and challenges from Malaysia’s perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 26, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.J.; Chong, M.F. Palm oil mill effluent (POME) treatment—Current technologies, biogas capture and challenges. In Green Technologies for the Oil Palm Industry; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Azmi, N.S.; Yunos, K.F.M. Wastewater treatment of palm oil mill effluent (POME) by ultrafiltration membrane separation technique coupled with adsorption treatment as pre-treatment. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2014, 2, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.A.; Zainal, B.S.; Jamadon, N.H.; Yaw, T.C.S.; Abdullah, L.C. Filtration analysis and fouling mechanisms of PVDF membrane for POME treatment. J. Water Reuse Desalin. 2020, 10, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.Y.; Mohammad, A.W.; Jahim, J.M.; Anuar, N. Palm oil mill effluent (POME) treatment and bioresources recovery using ultrafiltration membrane: Effect of pressure on membrane fouling. Biochem. Eng. J. 2007, 35, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.D.; Lim, J.S.; Alwi, S.R.W.; Walmsley, T.G. Comparative Assessment for Mechanical Vapour Recompression and Multi-effect Evaporation Technology in Palm Oil Mill Effluent Elimination. CET J.-Chem. Eng. Trans. 2021, 83, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Lestari, I.; Amalia, D.; Prastistho, W.; Angin, J.B.P.; Zenatik, M.H. Combination Process of Rice Husk Ash Coagulation and Electrocoagulation for Palm Oil Mill Effluent Treatment. Eksergi 2025, 22, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, M.H.; Al-Alawy, A.F.; Ahmed, T.A. Oil skimming followed by coagulation/flocculation processes for oilfield produced water treatment and zero liquid discharge system application. AIP Conf. Proc. 2021, 2372, 060006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmod, S.S.; Takriff, M.S.; AL-Rajabi, M.M.; Abdul, P.M.; Gunny, A.A.N.; Silvamany, H.; Jahim, J.M. Water reclamation from palm oil mill effluent (POME): Recent technologies, by-product recovery, and challenges. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 52, 103488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, M.S.H.; Haan, T.Y.; Lun, A.W.; Mohammad, A.W.; Ngteni, R.; Yusof, K.M.M. Fouling assessment of tertiary palm oil mill effluent (POME) membrane treatment for water reclamation. J. Water Reuse Desalin. 2018, 8, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.K.; Lee, K.T. Renewable and sustainable bioenergies production from palm oil mill effluent (POME): Win–win strategies toward better environmental protection. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011, 29, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.A.; Shukor, H.; Yin, L.S.; Kasim, F.H.; Shoparwe, N.F.; Makhtar, M.M.Z.; Yaser, A.Z. Methane Biogas Production in Malaysia: Challenge and Future Plan. Int. J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 2022, 2278211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, M.A.M. Performance Optimization of Industrial Scale In-Ground Lagoon Anaerobic Digester for Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME) Treatment. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Amosa, M.K.; Jami, M.S.; Muyibi, S.A.; Alkhatib, M.F.R.; Jimat, D.N. Zero liquid discharge and water conservation through water reclamation & reuse of Biotreated Palm Oil Mill Effluent: A review. Int. J. Acad. Res. 2013, 5, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.L.; Idris, I.; Chan, C.Y.; Ismail, S. Reclamation from palm oil mill effluent using an integrated zero discharge membrane-based process. Polish J. Chem. Technol. 2015, 17, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jami, M.S.; Amosa, M.K.; Alkhatib, M.F.R.; Jimat, D.N.; Muyibi, S.A. Boiler-feed and process water reclamation from biotreated palm oil mill effluent (BPOME): A developmental review. Chem. Biochem. Eng. Q. 2013, 27, 477–489. [Google Scholar]

- Abdurahman, N.H.; Rosli, Y.M.; Azhari, N.H. Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME) Treatment: A Review. In International Perspectives on Water Quality Management and Pollutant Control; BoD Books on Demand: Hamburg, Germany, 2013; p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- Haan, T.Y.; Ghani, M.S.H.; Mohammad, A.W. Physical and chemical cleaning for nanofiltration/reverse osmosis (NF/RO) membranes in treatment of tertiary palm oil mill effluent (POME) for water reclamation. J. Kejuruter. 2018, 24, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.U.; Rahman, M.A.; Othman, M.H.D.; Iftikhar, M.; Jilani, A.; Mehmood, S.; Shakoor, M.B.; Rizwan, M.; Yong, J.W.H. Innovative Solutions for Palm Oil Mill Effluent Treatment: A Membrane Technology Perspective. ACS EST Water 2025, 5, 3538–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristanti, R.A.; Hadibarata, T.; Yuniarto, A.; Muslim, A. Palm oil industries in Malaysia and possible treatment technologies for palm oil mill effluent: A review. Environ. Res. Eng. Manag. 2021, 77, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Date, M.; Patyal, V.; Jaspal, D.; Malviya, A.; Khare, K. Zero liquid discharge technology for recovery, reuse, and reclamation of wastewater: A critical review. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 49, 103129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riazi, F.; Fidélis, T.; Teles, F. Governance Arrangements for Water Reuse: Assessing Emerging Trends for Inter-Municipal Cooperation through a Literature Review. Water 2022, 14, 2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuniarto, A. Palm Oil Mill Effluent Treatment Using Aerobic Submerged Membrance Bioreactor Coupled with Biofouling Reducers. Ph.D. Thesis, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Johor Bahru, Malaysia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti, A.; Barbieri, G. Membrane Engineering for Biogas Valorization. Front. Chem. Eng. 2021, 3, 775788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M.S.M.; Abdel-Shafy, H.I.; Ibrahim, A.M. Zero liquid discharge of petrochemical industry wastewaters via environmentally friendly technologies: An overview. Egypt. J. Pet. 2025, 34, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P. Zero discharge of palm oil mill effluent through outdoor flash evaporation at standard atmospheric conditions. Oil Palm Bull. 2015, 71, 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Chandwankar, R.R.; Nowak, J. Thermal Process for Seawater Desalination: Multi-effect Distillation, Thermal Vapor Compression, Mechanical Vapor Compression and Multistage Flash. In Handbook of Water and Used Water Purification; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 465–502. [Google Scholar]

- Kandiah, S.; Batumalai, R. Palm oil clarification using evaporation. J. Oil Palm Res. 2013, 25, 233–235. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, M.; Duan, C.; Yue, P.; Li, T. Removal characteristics of dissolved organic matter and membrane fouling in ultrafiltration and reverse osmosis membrane combined processes treating the secondary effluent of wastewater treatment plant. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 83, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haan, T.Y.; Takriff, M.S. Zero waste technologies for sustainable development in palm oil mills. J. Oil Palm. Environ. Heal. 2021, 12, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Iskandar, M.J.; Baharum, A.; Anuar, F.H.; Othaman, R. Palm oil industry in South East Asia and the effluent treatment technology—A review. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2018, 9, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.L.; Chong, M.F.; Bhatia, S. Mathematical modeling of multiple solutes system for reverse osmosis process in palm oil mill effluent (POME) treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2007, 132, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.W.; Xin, N.H.; Mokhtar, N.M. Development of Bench-Scale Direct Contact Membrane Distillation System for Treatment of Palm Oil Mill Effluent. J. Appl. Membr. Sci. Technol. 2023, 27, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamad, N.A.S.; Mokhtar, N.M.; Naim, R.; Lau, W.J.; Ismail, N.H. Treatment of wastewater from oil palm industry in Malaysia using polyvinylidene fluoride-bentonite hollow fiber membranes via membrane distillation system. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 361, 124739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, I.A.; Chomiak, T.; Floyd, J.; Li, Q. Sweeping gas membrane distillation (SGMD) for wastewater treatment, concentration, and desalination: A comprehensive review. Chem. Eng. Process.-Process Intensif. 2020, 153, 107960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; Nawaz, M.H.; Rout, P.R.; Lim, J.W.; Mainali, B.; Shahid, M.K. Advances in Produced Water Treatment Technologies: An In-Depth Exploration with an Emphasis on Membrane-Based Systems and Future Perspectives. Water 2023, 15, 2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnaizy, R.; Dawood, F. Optimization of a single-effect evaporation system to effectively utilize thermal energy. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy Off. Publ. Am. Inst. Chem. Eng. 2009, 28, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, T.; Loh, L. Innovating ESG Integration as Sustainable Strategy: ESG Transparency and Firm Valuation in the Palm Oil Sector. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagaba, A.H.; Kutty, S.R.M.; Hayder, G.; Baloo, L.; Noor, A.; Yaro, N.S.A.; Saeed, A.A.H.; Lawal, I.M.; Birniwa, A.H.; Usman, A.K. A systematic literature review on waste-to-resource potential of palm oil clinker for sustainable engineering and environmental applications. Materials 2021, 14, 4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, D.L. Public–private partnerships in the water reuse sector: A global assessment. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2016, 32, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.V.; Varjani, S.; Srivastava, V.K.; Bhatnagar, A. Zero liquid discharge (ZLD) as sustainable technology—Challenges and perspectives. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2020, 58, 508–514. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bachi’, N.A.; Mohtar, W.H.M.W.; Zin, W.Z.W.; Takeuchi, H.; Hanafiah, Z.M. Recycled water for non-potable use: Understanding community perceptions and acceptance in Malaysia. Water Policy 2023, 25, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küfeoğlu, S. SDG-13: Climate Action. In Emerging Technologies: Value Creation for Sustainable Development; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 429–451. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, A.K. Sustainable water management through integrated technologies and circular resource recovery. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2025, 11, 1822–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küfeoğlu, S. SDG-12: Responsible consumption and production. In Emerging Technologies: Value Creation for Sustainable Development; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 409–428. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S.; Weitz, N.; Persson, Å.; Trimmer, C. SDG 12: Responsible consumption and production. In A Review of Research Needs. Technical Annex to the Formas Report Forskning för Agenda, 2030; Stockholm Environment Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Elewa, M.M. Emerging and conventional water desalination technologies powered by renewable energy and energy storage systems toward zero liquid discharge. Separations 2024, 11, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadalla, M.A.; Fatah, A.A.; Elazab, H.A. A novel renewable energy powered zero liquid discharge scheme for RO desalination applications. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2023, 8, 100407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MPOB. Malaysian Palm Oil Board MPOB; MPOB: Kajang, Malaysia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Grönwall, J.; Jonsson, A. The impact of zero coming into fashion: Zero liquid discharge uptake and socio-technical transitions in Tirupur. Water Altern. 2017, 10, 602–624. [Google Scholar]

- Prasath, G.A.; Velmurugan, D.; Ravichandran, S. The scenario of groundwater pollution after implementation of zero liquid discharge: An agricultural economic perspective. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Sociol 2024, 42, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodialbail, V.S.; Sophia, S. Concept of zero liquid dischare—Present scenario and new opportunities for economically viable solution. In Concept of Zero Liquid Discharge; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Malaysia, T.I. Corporate Integrity System Malaysia. 2025. Available online: https://transparency.org.my/pages/what-we-do/corporate-integrity-system-malaysia (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Majid, N.A.; Ramli, Z.; Sum, S.M.; Awang, A.H. Sustainable palm oil certification scheme frameworks and impacts: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, M.N.Z.; Fatah, F.A.; Noor, W.; Aris, N.F.M. A review on adoption of the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) certification scheme. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1397, 12035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, S.R.; Arzaman, A.F.M.; Razali, M.A.; Yasin, N.I.; Masrom, N.R.; Sabri, N.A.A.; Margono, M. The deployment of the Malaysian sustainable palm oil standard in the agriculture sector. Multidiscip. Sci. J. 2024, 6, 2024115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Water Sector Transformation (WST2040). 2025. Available online: https://wst2040.my/ (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Ludin, N.A.; Phoumin, H.; Chachuli, F.S.M.; Hamid, N.H. Sustainable energy policy reform in Malaysia. In Revisiting Electricity Market Reforms: Lessons for ASEAN and East Asia; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 251–281. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.N.H.N.; Amran, A.; Siti-Nabiha, A.K.; Rahman, R.A. Sustainable palm oil: What drives it and why aren’t we there yet? Asian J. Bus. Account. 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, W.; Heng, L.; Leong, Y. Malaysia renewable energy policy and its impact on regional countries. IET Conf. Proc. CP843 2023, 2023, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, G.; Tian, X.; Ding, G.; Zhang, H. Industry application of digital twin: From concept to implementation. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 121, 4289–4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, T.; Elimelech, M. The global rise of zero liquid discharge for wastewater management: Drivers, technologies, and future directions. Environmental science & technology. ACS Publ. 2016, 50, 6846–6855. [Google Scholar]

- Khoiruddin, K.; Boopathy, R.; Kawi, S.; Wenten, I.G. Towards next-generation membrane bioreactors: Innovations, challenges, and future directions. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2025, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromolaran, O.; Oyeku, O.G.; Falodun, O.I.; Unuabonah, E.I. Sustainable Management of Wastewater from Oil Palm Processing Industry. In Strategic Management of Wastewater from Intensive Rural Industries; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 213–231. [Google Scholar]

- Mwafy, E.A.; Mouneir, S.M.; El-Shamy, A.M. Flowing towards Sustainability: Achieving Water Neutrality through Effective Water Management. In Water Neutrality: Towards Sustainable Water Management; ACS Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2025; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H. Bibliometric Analysis on Socio-Technological Innovation in Water Governance under the High Water-Intensive Industry Perspective: A Case Based on the CDP Water Impact Index Report. Master’s Thesis, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Integration Point | Required Pre-Treatment | Energy Demand | Capital Required | Process Outputs | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw POME | High; Coarse solid removal, oil recovery | High | High | Solid discharge (biofertilizer), boiler feed water | Applicable to new plants replacing the ponding system. High risk of severe membrane fouling and scaling. High operational complexity. |

| After Biological Treatment | Minimal; removal of suspended solids | Moderate | Moderate | Concentrated solid, Reclaimed water | Installed after biological treatment; advantage of capturing biogas. Requires high technical expertise to couple both systems. Microbial management in biological stage is critical. |

| Post- Treatment | No pre-treatment | Low | Low | High Purity Reclaimed water | Installed after biological and post- treatment; easy installation to existing plant. Performance is highly dependent on the efficiency of upstream biological treatment. Membrane fouling remains a concern. |

| Parameter | Conventional Ponding System | ZLD System (Hybrid Systems) | Improvement | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land Area Occupied | 1–2 hectares (baseline) | 0.2–0.5 hectares | 70–85% Reduction | [24] |

| GHG Emissions | ~18 kg CO2-eq/m3 POME (uncaptured) | <1 kg CO2-eq/m3 POME (with biogas capture) | >95% Reduction | [7] |

| Water Recovery | 0% | 90–95% | 90–95% Recovery | [29,33] |

| BOD Removal Efficiency | ~90% (often non-compliant) | >99% | Significant enhancement | [33] |

| Payback Period | N/A (baseline) | 5–10 years (highly variable) | Dependent on financing and energy credits | [15,59] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Junaidi, M.U.M.; Ullah, A.; Mohd Amin, N.H.; Rabuni, M.F.; Amir, Z.; Adnan, F.H.; Nafiat, N.; Roslan, A.H.; Othman, M.F.H.; Noor Bakry, N.L. The Potential of Zero Liquid Discharge for Sustainable Palm Oil Mill Effluent Management in Malaysia: A Techno-Economic and ESG Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10665. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310665

Junaidi MUM, Ullah A, Mohd Amin NH, Rabuni MF, Amir Z, Adnan FH, Nafiat N, Roslan AH, Othman MFH, Noor Bakry NL. The Potential of Zero Liquid Discharge for Sustainable Palm Oil Mill Effluent Management in Malaysia: A Techno-Economic and ESG Perspective. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10665. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310665

Chicago/Turabian StyleJunaidi, Mohd Usman Mohd, Aubaid Ullah, Noor Hafizah Mohd Amin, Mohamad Fairus Rabuni, Zulhelmi Amir, Faidzul Hakim Adnan, Niswah Nafiat, Aiman Hakim Roslan, Muhamad Farhan Haqeem Othman, and Natasha Laily Noor Bakry. 2025. "The Potential of Zero Liquid Discharge for Sustainable Palm Oil Mill Effluent Management in Malaysia: A Techno-Economic and ESG Perspective" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10665. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310665

APA StyleJunaidi, M. U. M., Ullah, A., Mohd Amin, N. H., Rabuni, M. F., Amir, Z., Adnan, F. H., Nafiat, N., Roslan, A. H., Othman, M. F. H., & Noor Bakry, N. L. (2025). The Potential of Zero Liquid Discharge for Sustainable Palm Oil Mill Effluent Management in Malaysia: A Techno-Economic and ESG Perspective. Sustainability, 17(23), 10665. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310665