A Hybrid Spatial–Experiential Design Framework for Sustainable Factory Tours: A Case Study of the Optical Lens Manufacturer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Spatial Organization and Experiential Elements in Tourism Spaces

2.2. Visitor-Centered Approaches to Experience-Driven Spatial Design

3. Materials and Methods

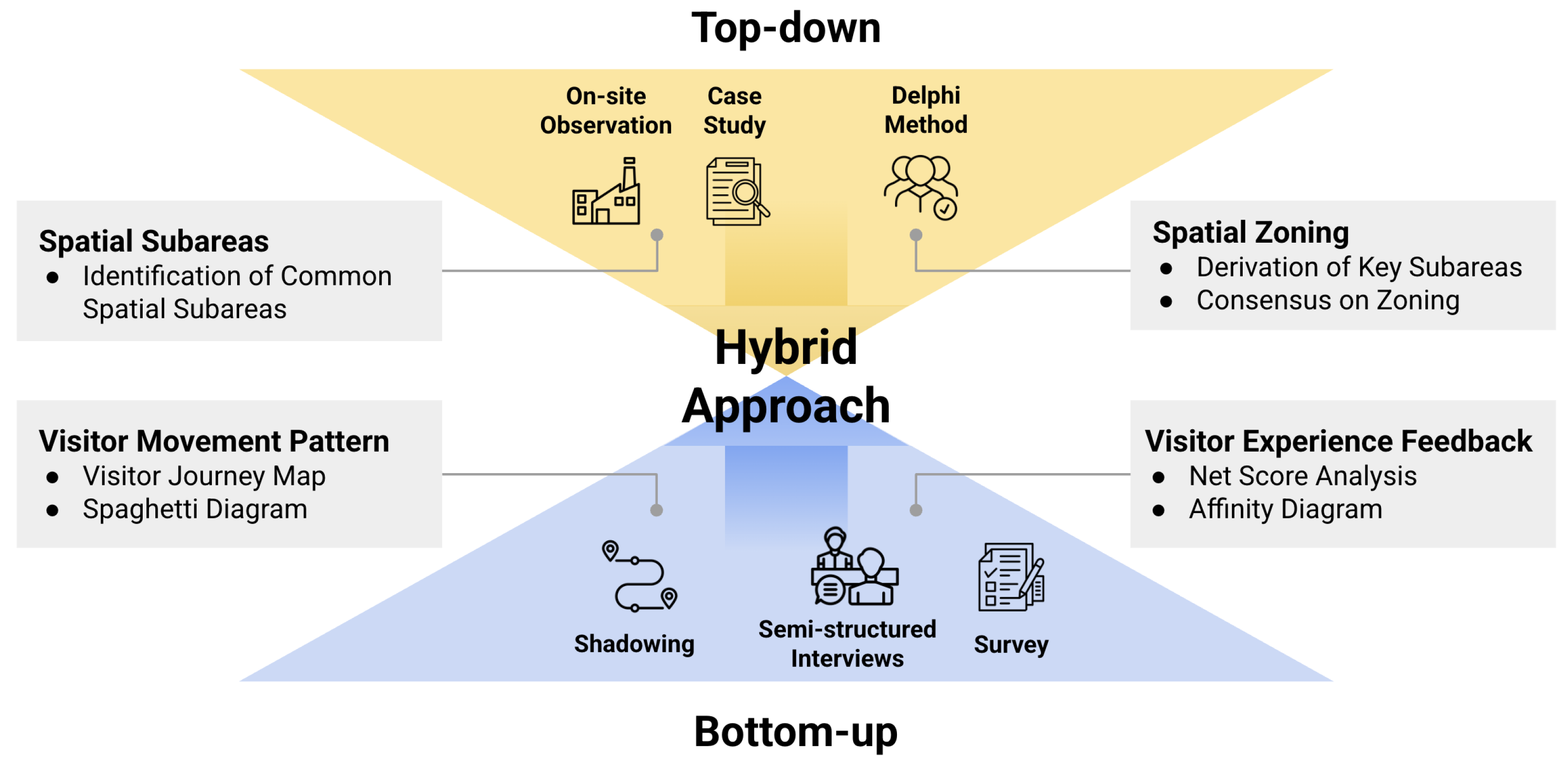

3.1. Research Framework: A Hybrid Approach

3.2. Top-Down Approach: Spatial Planning

3.2.1. Identifying Spatial Patterns in Factory Tours: Fieldwork and Case Analysis

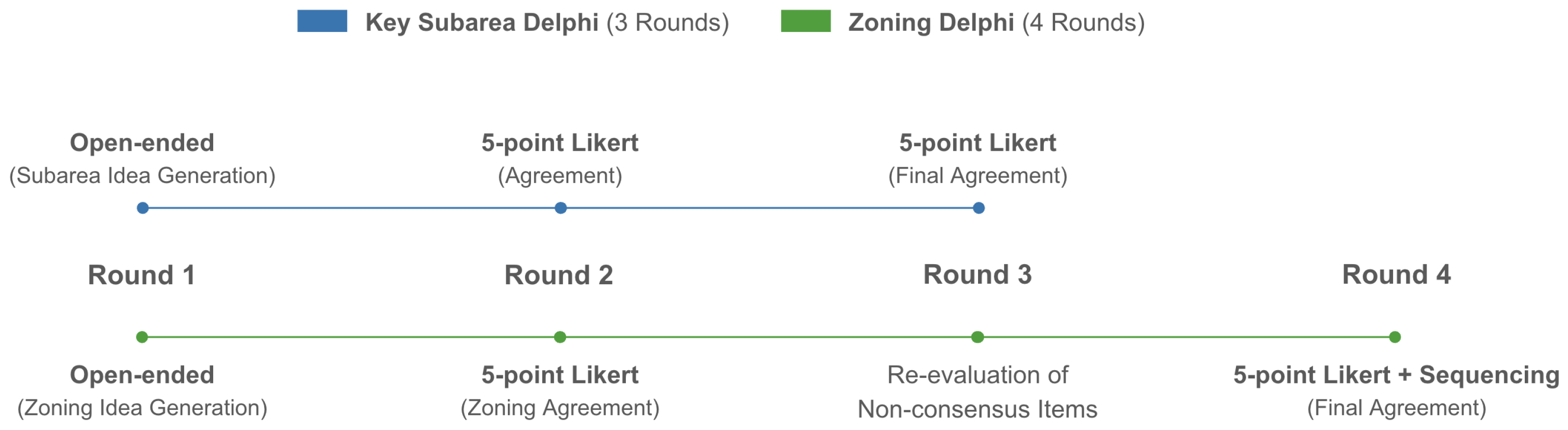

3.2.2. Delphi-Based Spatial Zoning and Key Subarea Identification

- First Delphi Round (13 February–29 March 2024): Focused on identifying and evaluating key subareas based on cross-national case analysis and site observations. The process involved three iterative rounds: (1) an open-ended questionnaire allowing additions or removals of subareas, and (2–3) two rating rounds using a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) to assess each subarea’s importance for visitor engagement and spatial planning.

- Second Delphi Round (17 February–25 March 2025): Focused on refining and validating the spatial zoning framework. Conducted in four rounds, the first two grouped and rated the 11 subareas into functional zones, while the latter two refined areas lacking consensus and finalized the preferred visitor flow sequence. Two experts from the first phase were replaced by new participants of a similar background, maintaining a 10-member panel.

3.3. Bottom-Up Approach: Visitor Behavior and Experiential Needs

3.3.1. Shadowing: Investigating Visitor Movement Patterns

3.3.2. Survey and Interview: Identifying Visitor Preferences and Pain Points

3.4. Research Setting: Hwa Meei’s Eye Fun Vision

4. Results

4.1. Top-Down Approach: Analysis of Spatial Zoning Strategies

4.1.1. Comparative Case Study of Factory Tours

4.1.2. Delphi Analysis of Spatial Zoning and Key Subareas

- Round 1: Added Information Center, Community Contribution, and Café; renamed categories (e.g., Founder and CEO → Company Founding Background and MVC; Hands-on Activities → Hands-on and Interactive Activities). Games and Quizzes were removed; Manufacturing Equipment merged with Manufacturing Process.

- Round 2: Entire Product History excluded (CVR = 0.2, agreement = 0.375, convergence = 1.25). Further renaming (e.g., Information Center → Information Desk; CSR → ESG).

- Round 3: Company ESG excluded (CVR = 0.4, agreement = 0.625, convergence = 0.75). Final 11 subareas: Information Desk, Company Founding Background and MVC, Company History, Company Product History, Manufacturing Process, Company Product Line Archive, Hands-on and Interactive Activities, DIY Workshop, Goods Shop, Café, Photo Zone.

- Round 1: Experts responded to open-ended questions to propose and refine initial zoning ideas. Based on their professional judgment, the 11 subareas were grouped according to functional and thematic coherence.

- Round 2: Using a 5-point Likert scale, experts rated the appropriateness of the proposed zones and key subarea groupings. Consensus was reached on four primary zones: Heritage·History, Manufacture·Product, Experience, and Convenience.

- Round 3: Items not meeting the convergence threshold were re-evaluated. This round focused on the naming and scope of the Convenience Zone and the placement of the Information Desk and Photo Zone. Experts agreed that the Convenience Zone label was appropriate and that the Information Desk could serve as an independent or embedded zone depending on contextual needs. The Photo Zone was deemed flexible and transferable across zones.

- Round 4: Experts conducted a final 5-point Likert-scale evaluation and determined the optimal visitor flow sequence. The Information Desk did not reach the statistical threshold for content validity (CVR = 0.00, convergence = 0.71), indicating that it was not associated with any specific thematic zone. The Photo Zone was reaffirmed as a flexible subarea adaptable across spatial layouts and movement designs.

- Heritage·History Zone: Includes subareas focused on the company’s founding background, mission–vision–core values (MVC), and corporate history.

- Manufacture·Product Zone: Highlights the manufacturing process and showcases a product line archive to convey technical expertise and innovation.

- Experience Zone: Consists of hands-on and interactive activities, including a DIY workshop, designed to engage visitors actively.

- Convenience Zone: Provides visitor amenities such as the retail shop and café, encouraging longer stays and enhancing comfort.

- Information Desk (**): Serves as a critical orientation point. Although not formally part of the four primary zones, it may be positioned independently or integrated contextually based on spatial layout and visitor flow.

- Photo Zone (*): A flexible key subarea that may be embedded within any of the four zones or configured, depending on curatorial intent and site constraints.

- Information Desk: Ranked 1st by 9 out of 10 experts, showing strong agreement. One expert also marked it with an asterisk to emphasize its foundational role.

- Heritage·History Zone: Ranked 2nd by 8 experts. The remaining two were assigned 1st and uncertain (2nd–4th).

- Manufacture·Product Zone: Received 3rd place from 8 experts; one placed it 2nd and another marked it as uncertain (2nd–4th).

- Experience Zone: Ranked 4th by 7 experts. Other rankings included 3rd (1 expert), 5th (1 expert), and uncertain (2nd–4th, one expert).

- Convenience Zone: Typically ranked 5th by 8 experts. Outliers included rankings of 4th and either 1st or 6th (ambiguous response).

- Photo Zone: Marked as uncertain by 5 experts. Among others, it was placed 6th by three experts and notably higher by two—1st and 3rd—indicating diverse perceptions of its importance.

4.2. Bottom-Up Approach: Insights from Visitor and Feedback

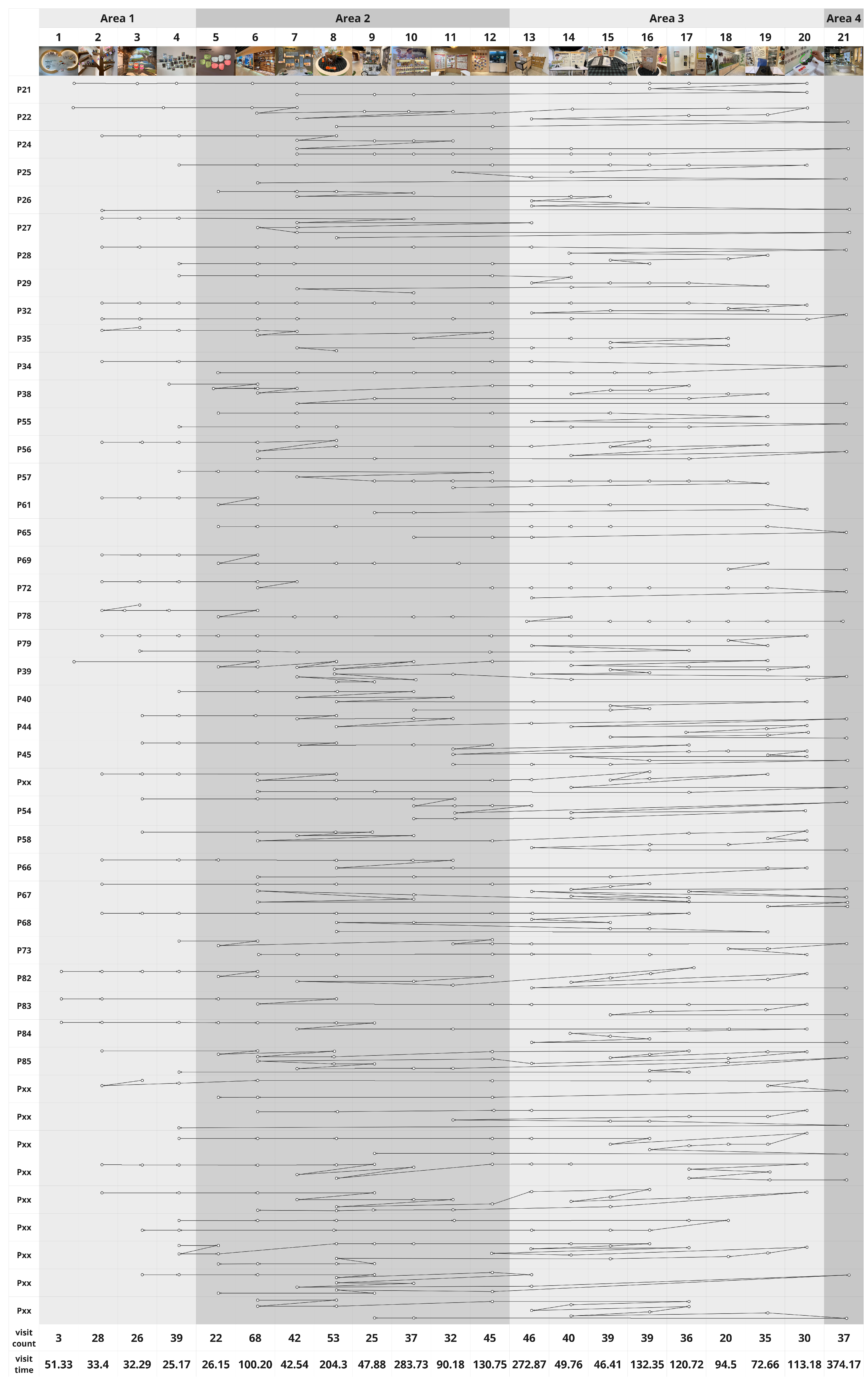

4.2.1. Visitor Movement Analysis via Journey Map and Spaghetti Diagram

- High-Engagement Subareas (8, 10, 13, 16, 21): Their strong performance suggests that tactile interaction, DIY elements, or sensory experiences drive prolonged interest. These areas should be preserved and potentially expanded to reinforce experiential value.

- Moderate-Engagement Subareas (5, 6, 7, 9, 12, 14, 15, 17, 19, 20): These subareas consistently attract visitors for a moderate duration. While functional, they may benefit from enhanced storytelling, interactive features, or environmental cues to deepen visitor immersion and elevate them to high engagement.

- Low-Engagement Subareas (1–4, 11, 18): These subareas failed to meet the visit count and dwell time thresholds. Their limited impact suggests a need for redesign, incorporating multimedia, gamification, hands-on displays, or spatial repositioning to increase visibility and engagement.

- Path Optimization: Identifies frequently and infrequently used routes. Complex or lengthy routes are flagged for simplification and improved wayfinding.

- Bottleneck Analysis: Detects areas of congestion or repeated visitor clustering, enabling layout adjustments or redistribution of foot traffic.

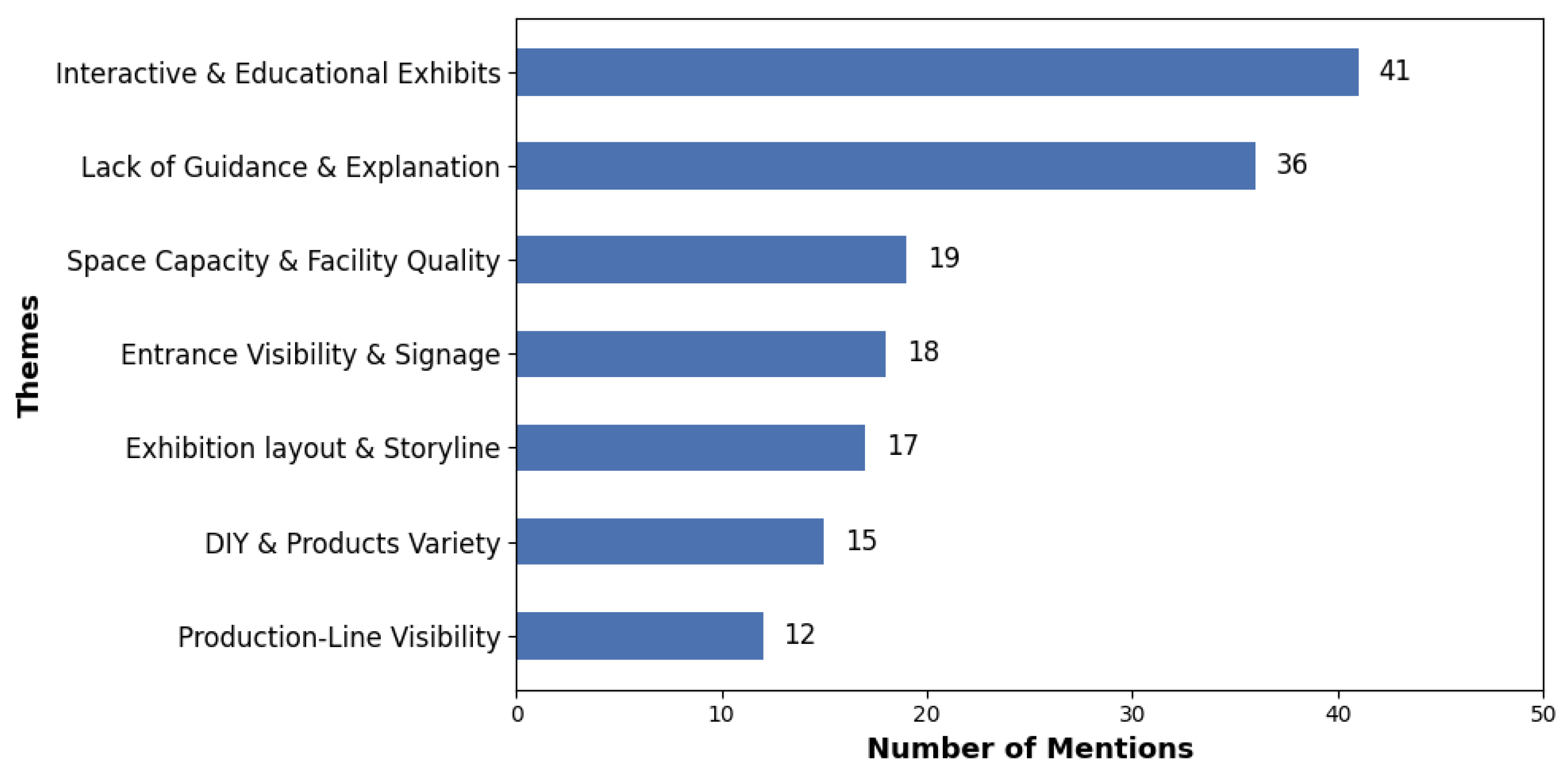

4.2.2. Visitor Feedback Analysis: Satisfaction Metrics and Thematic Insights

- Glasses DIY (No. 10): Visitors appreciated the opportunity to assemble and personalize glasses, finding the creative and educational activity. It encouraged parent-child interaction and was especially popular with families. The aesthetic quality of the final product and the ability to take it home further enhanced satisfaction.

- Hand–Eye Coordination Toy (No. 8): This subarea was praised for its entertaining and competitive nature. Visitors noted improvements in concentration and coordination and enjoyed the playful yet meaningful interaction it provided, particularly for children.

- Firsthand Experience for Colored Lenses (No. 17): Visitors enjoyed exploring various lens colors through immersive visuals. The experience was informative and memorable, offering a creative perspective on visual perception.

- Army Protective Eyewear (No. 18): Visitors struggled with unclear reservation and usage instructions. Technical malfunctions, limited accessibility for children, and confusion about interaction methods negatively impacted the experience. Improvements in guidance, equipment functionality, and inclusive design are needed.

- Different Eye Pathologies (No. 13): Users found the equipment difficult to operate due to vague instructions and poor accessibility (e.g., instruction height, device layout). Limited interactivity and emotionally unsettling content (e.g., disease imagery) further reduced engagement.

- See Hwa Meei (No. 1): Many visitors overlooked this introductory section due to excessive text, low visual appeal, and limited interactivity. Making the content more concise, visually engaging, and interactive could help draw attention and communicate the company’s story better.

4.3. Hybrid Approach: Integrated Spatial and Experiential Design for Factory Tours

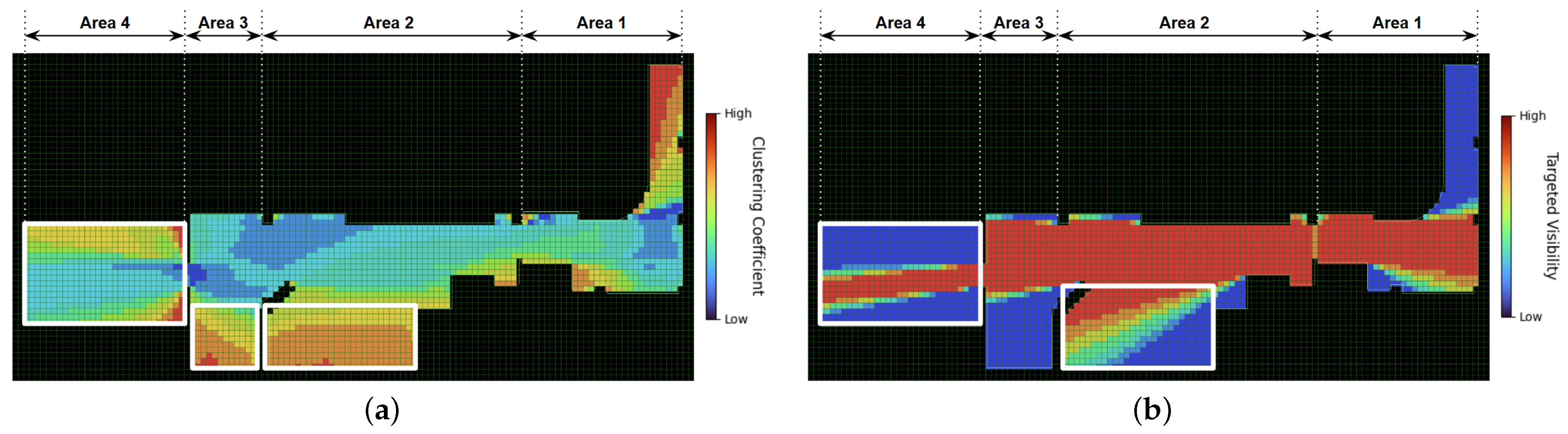

4.3.1. Integrating Zoning, Visitor Behavior, and VGA for Spatial Optimization

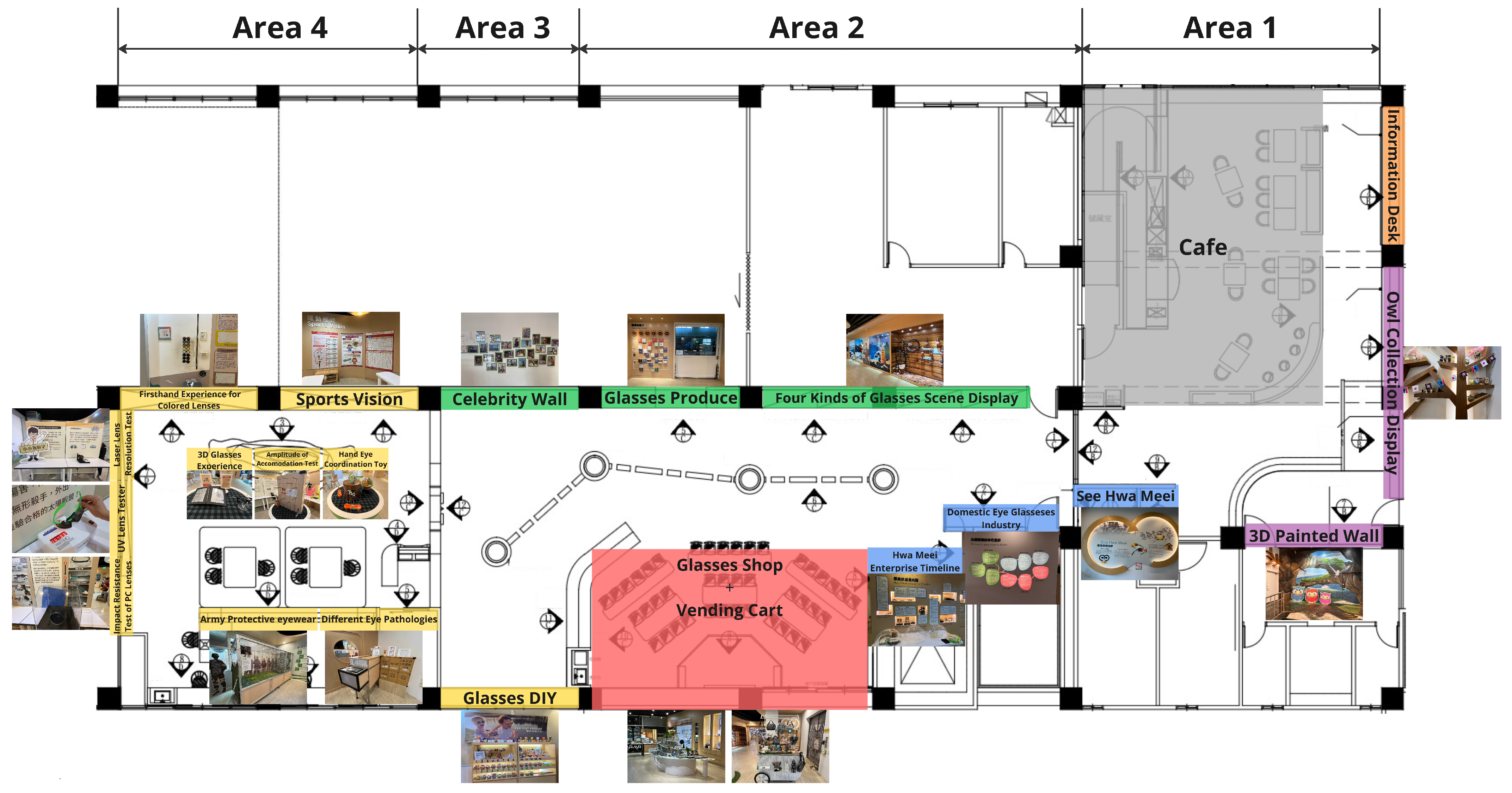

- Information Desk (Orange): Located at the entrance, the newly added Information Desk provides essential safety guidance and a comprehensive overview of the tour, improving visitor orientation and facilitating smoother transitions throughout the space.

- Photo Zone (Purple): Positioned adjacent to the entrance, this area includes the 3D Painted Wall and Owl Collection Display. Although outside the fixed tour route, it serves as a visually engaging prelude where visitors can casually interact and take photos before beginning the formal tour.

- Heritage·History (Blue): Starting with “See Hwa Meei” in Area 1 and continuing into Area 2 with the Domestic Eyeglass Industry and Enterprise Timeline exhibits, this zone introduces the company’s origins, mission, and legacy within the eyewear industry.

- Manufacture·Product (Green): Spread across the upper sections of Areas 2 and 3, this zone showcases Hwa Meei’s production processes and branding through exhibits such as the Four Types of Eyeglasses Display, Glasses Produce, and Celebrity Wall.

- Experience (Yellow): Located in the lower part of Area 3 and reconfigured Area 4, this zone provides hands-on programs such as the glasses DIY Workshop, aiming to deepen engagement through interactive and educational activities.

- Convenience (Red): Situated at the end of the visitor flow in Area 2, this zone includes the relocated Glasses Shop and Vending Cart, offering a comfortable and satisfying conclusion to the tour through retail interaction and staff support.

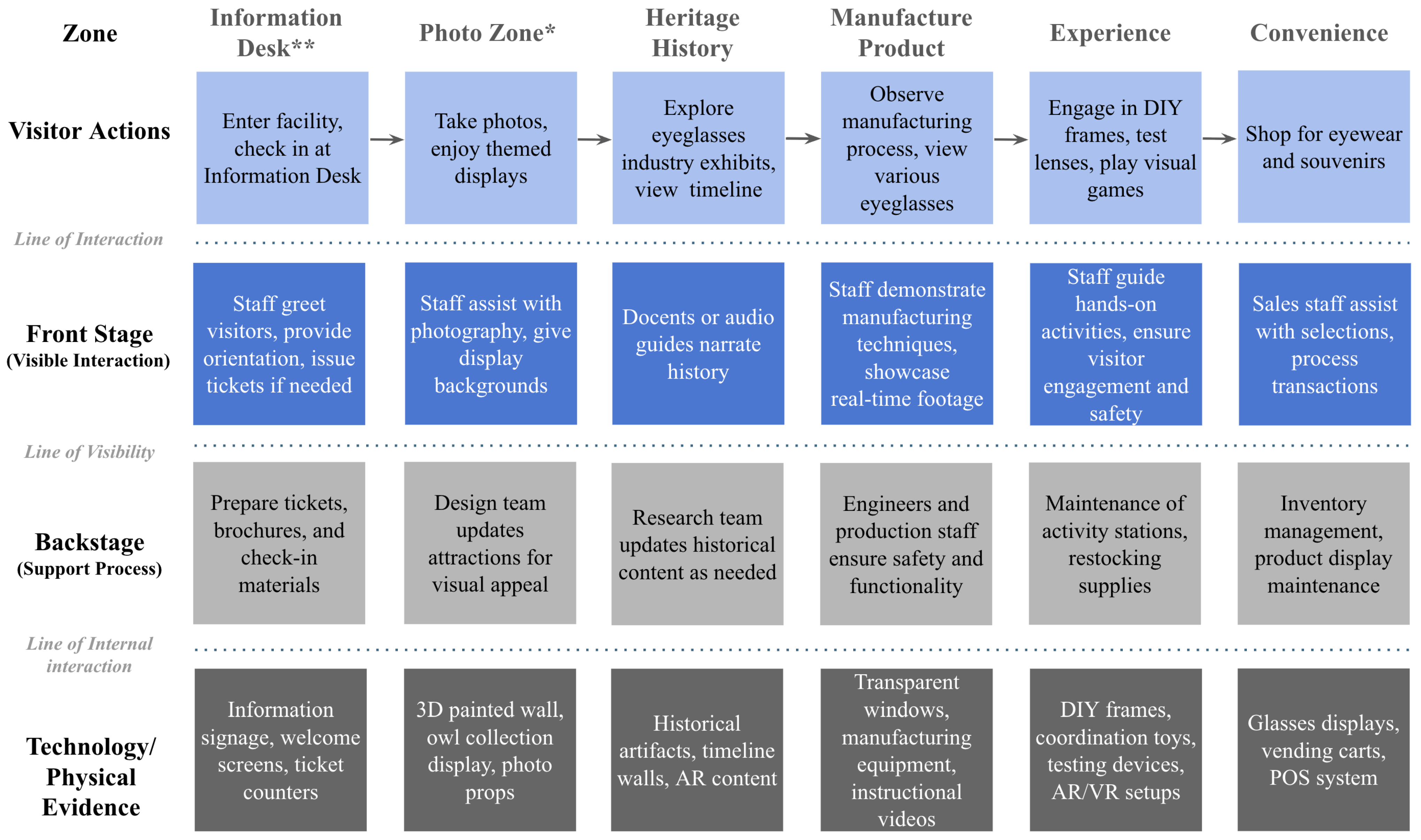

4.3.2. Service Blueprint Linking Spatial Zones and Visitor Experience

- Information Desk: The Information Desk offers essential guidance on the tour route and safety protocols, helping structure the visitor experience from the outset. Frontstage staff handle inquiries, while backstage teams manage informational materials and signage updates.

- Photo Zone: The Photo Zone is a visually engaging entry or exit point, where visitors can capture memories through installations like the 3D Painted Wall and Owl Collection. Design staff support by maintaining props and updating visual elements.

- Heritage History: The Heritage History Zone tells the story of Hwa Meei’s founding and industrial legacy through curated exhibits, timeline panels, and augmented reality (AR) content. Interpretive support is provided via docents or audio guides, with backstage teams managing historical curation and media systems.

- Manufacture·Product: The Manufacture·Product Zone offers direct views of live lens production, with staff explaining the process and engineers ensuring operational safety. This zone reinforces technical credibility through frontstage demonstration and backstage coordination.

- Experience: The Experience Zone engages visitors in hands-on activities, including DIY frame-making and lens testing. Frontstage facilitators lead the interactions, while backstage teams ensure the availability of materials and maintain AR/VR systems.

- Convenience: The Convenience Zone completes the tour with retail opportunities. Sales staff support visitors in product selection and purchase, while inventory and merchandising teams manage stock levels and display organization behind the scenes.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Twenty-One Subareas of ‘Eye Fun Vision’

Appendix B. Demographic Profile of Visitors

| Items | Number | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visit Type | Group with children | 71 | 69.61 |

| Group without children | 31 | 30.39 | |

| Visit Purpose | Just visit | 94 | 92.16 |

| Try or buy glasses | 3 | 2.94 | |

| Try DIY | 2 | 1.96 | |

| Prescription of eyeglasses | 1 | 0.98 | |

| Replace eyewear parts | 1 | 0.98 | |

| Learn about Hwa Meei | 1 | 0.98 | |

| Residence | Tainan | 43 | 42.16 |

| Kaohsiung | 14 | 13.73 | |

| Taichung | 11 | 10.78 | |

| Chiayi | 5 | 4.90 | |

| Yongkang | 5 | 4.90 | |

| Taoyuan | 5 | 4.90 | |

| Changhua | 4 | 3.92 | |

| Taipei | 3 | 2.94 | |

| Hsinchu | 2 | 1.96 | |

| Taitung | 2 | 1.96 | |

| New Taipei | 2 | 1.96 | |

| Yilan | 2 | 1.96 | |

| Pingtung | 2 | 1.96 | |

| Hualien | 1 | 0.98 | |

| USA | 1 | 0.98 | |

| Visit Duration | Less than 30 min | 23 | 22.55 |

| 30 min to 1 h | 44 | 43.14 | |

| More than 1 h | 35 | 34.31 |

Appendix C. Customer Journey Map of 45 Visitors

Appendix D. Themes Identified in Visitor Feedback

References

- Frew, E.A. Industrial Tourism: A Conceptual and Empirical Analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, Victoria University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Otgaar, A. Industrial Tourism: Where the Public Meets the Private; Erasmus University Rotterdam, Erasmus Research Institute of Management (ERIM): Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Report No. EPS-2010-219-ORG. [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro, Z.; Marques, J.; Sousa, C. Industrial tourism as a factor of sustainability and competitiveness in operating industrial companies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorochan, V. Definition of industrial tourism stages. Glob. Natl. Probl. Econ. 2014, 2, 60–61. [Google Scholar]

- Future Market Insights. Industrial Tourism Market Analysis by Experience Type, by End, by Tourist, by Booking Channel, and by Region—Forecast for 2025 to 2035. Available online: https://www.futuremarketinsights.com/reports/industrial-tourism-market (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Nasuno, I. Measures to revitalize industrial tourism in the Nagoya and Chukyo areas of Japan using structural equation modeling. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Hospitality and Tourism Management, Online, 27–28 October 2022; Volume 7, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, H. Service quality survey of technical visits for foreign visitors. J. Glob. Tour. Res. 2022, 7, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, H.I.; Liu, L.W.; Yang, L.S.; Hsieh, C.C. Strategic planning for Taiwanese industrial tourism parks themed on local characteristic industries. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2023, 14, 1942–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, H.Y.; Yang, C.H. Culture conservation and regeneration of traditional industries derived by tourism factory: Case study of Kwong Xi Paper Factory in Taiwan. Int. J. Humanit. Arts Soc. Sci. 2016, 2, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fu, Y. A comparative study of industrial tourism of cities in China. Chin. Stud. 2019, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-T. The Future Development Directions of Industrial Tourism in Korea; Seoul Research Institute: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Tourism Organization. Analysis of the Results of Industrial Tourism Project and Establishment of Activation Measures; Korea Tourism Organization: Wonju, Republic of Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H.-Y.; Park, J.-B.; Han, W.-M.; Yoo, G.-W. Status of Industrial Tourism Operations and Activation Measures; Korea Industrial Complex Corporation: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, M.A.; Orwig, R.A. Consumer experience tourism and brand bonding. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2002, 11, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eumseong County. Eumseong Tourism Factory. Available online: https://www.eumseong.go.kr/factory/index.do (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Taiwan Tourism Factory Website. Available online: https://www.tourismfactory.tw/en/ (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Danilov, V.J. A Planning Guide for Corporate Museums, Galleries, and Visitor Centers; Greenwood Press: Westport, CT, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cudny, W.; Horňák, M. The tourist function in a car factory Audi Forum Ingolstadt example. Bull. Geogr. Socio-Econ. Ser. 2016, 33, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, K.; Byrom, J.W. Corporate Museums in Japan: Institutionalising a Culture of Industry and Technology; University of Tasmania: Dynnyrne, Australia, 2007; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/102.100.100/493191 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Piątkowska, K. The corporate museum: A new type of museum created as a component of marketing company. Int. J. Incl. Mus. 2014, 6, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramshaw, G. Assembling heritage tourism: The BMW museum and factory tour. In Automobile Heritage and Tourism; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; pp. 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, T. Narrative Environments and Experience Design: Space as a Medium of Communication; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J.; Peponis, J. What Do We Mean by Building Function? E & FN Spon Ltd.: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, H.W.; Ling, G.J.; Yen, I.Y.; Hwang, K.P. Building brand equity through industrial tourism. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2017, 22, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, J.; Azevedo, A. Visitor journey mapping: The Chocolate Factory Museum in Viana do Castelo (Portugal). In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Tourism Research, Porto, Portugal, 14–15 March 2019; p. 407. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, C.H.; Peng, Y.J.; Wu, H.H. Evaluating service process satisfaction of a tourism factory—Using Brands’ Health Museum as an example. In Proceedings of the 2012 6th International Conference on New Trends in Information Science, Service Science and Data Mining (ISSDM), Taipei, Taiwan, 25–27 October 2012; pp. 244–247. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, T.M.; Chen, S.H.; Chen, T.F. The relationships among experiential marketing, service innovation, and customer satisfaction—A case study of tourism factories in Taiwan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.C.L.; Guo, J.A.; Luo, F.Y. Construction of experience aesthetics centered innovative experience design model for tourism factories—Example of industries in Douliu Industrial Park in Yunlin County. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Applied System Innovation (ICASI), Sapporo, Japan, 13–17 May 2017; pp. 1395–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh-Ching, H.; Chun-Yu, H.; Yun-Ci, Z. Discussing the innovative experience design model of tourism factory: A case study on Shiroi Koibito Park in Hokkaido, Japan. Educ. Innov. Appl. 2018, 1, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y. Analysis and suggestions on Chinese industrial tourism development. Int. Bus. Res. 2010, 3, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, J.; Ballantyne, R. Conceptualizing the visitor experience: A review of literature and development of a multifaceted model. Visit. Stud. 2016, 19, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.J. The theory of affordances (1979). In The People, Place, and Space Reader; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, D.A. The Psychology of Everyday Things; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M. Six views of embodied cognition. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2002, 9, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, G. Design in Architecture: Architecture and the Human Sciences; E & FN Spon Ltd.: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.F. Tourist satisfaction with factory tour experience. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2015, 9, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.L. The analysis of sustainable development strategies for industrial tourism based on IOA-NRM approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241, 118281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk, B.C. A conceptual model of spaces, space boundaries and enclosing structures. Autom. Constr. 1992, 1, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peponis, J.; Dalton, R.C.; Wineman, J.; Dalton, N. Measuring the effects of layout upon visitors’ spatial behaviors in open plan exhibition settings. Environ. Plan. Plan. Des. 2004, 31, 453–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S.-H. A study on spatial zoning in museums. J. Archit. Inst. Korea Plan. Des. 2005, 21, 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Tzortzi, K. Museum building design and exhibition layout. In Proceedings of the 6th International Space Syntax Symposium, Istanbul, Turkey, 12–15 June 2007; Volume 1215, p. 072. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.H. Development of brand exhibition hall design to improve corporate image—Focusing on the Samsung Delight renovation project. J. Korean Soc. Spat. Des. 2017, 12, 157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.H. A study on corporate exhibition hall plans for brand revitalization. In Proceedings of the Korean Society of Interior Design Conference, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 28 May 2011; Volume 13, pp. 220–223. [Google Scholar]

- Dera, R.; Ridzqo, I.F. Spatial zoning analysis of zoo in urban area as a preliminary assessment for improving the education and recreation roles. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, The 20th Sustainable, Environment and Architecture, Online, 10 November 2020; IOP Publishing Ltd.: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 738, p. 012064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateescu, M.; Kauffeld, S. Interactive external representations for knowledge-building processes and performance in dyads: An experimental study. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2024, 16, 100519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhanen-Hunter, L.M. Sustainable Tourism Planning: An Analysis of Queensland Local Tourism Destinations. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Queensland, St. Lucia, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, B.; Fyall, A.; Leask, A.; Reid, E. Engaging residents as stakeholders of the visitor attraction. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1159–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zátori, A.; Smith, M.K.; Puczkó, L. Experience-involvement, memorability and authenticity: The service provider’s effect on tourist experience. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nubani, L.; Puryear, A.; Kellom, K. Measuring the effect of visual exposure and saliency of museum exhibits on visitors’ level of contact and engagement. Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, J.; Yang, L. From functional space to experience space: Applying space syntax analysis to a museum in China. Int. Rev. Spat. Plan. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 8, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Yoon, H.J. Analysis of visitor movement patterns and behaviors in literary tourism using direct observation: A case study of the Kim Yu-Jeong Literature Village. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 35, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-K.; Hyung, S.-E.; Cho, K.-S. A proposal for regional design services to specialize regional tourism: Focusing on Jeonju Hanok Village. J. Ind. Des. Stud. 2013, 7, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, C.-J.; Jung, S.-U.; Park, M.-H. A study on museum spatial composition based on exhibition methods and visitor behavior analysis. J. Korean Inst. Inter. Des. 2003, 39, 108–115. [Google Scholar]

- Hilda, A. Movements and Behaviors in Exhibition Spaces: An Exploratory Case Study in a Science Center. Master’s Thesis, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.H. Circulation Planning and Visitor Behavior Characteristics in Museum Exhibition Spaces; Dongrim Publishing: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2008; Available online: https://product.kyobobook.co.kr/detail/S000000764694 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Nam, Y.; Ha, K.S. Ecotourism service design process and methodology. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2019, 19, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponsignon, F.; Holmqvist, J. A framework for designing visitor experiences in branded tourist attractions: Insights from a luxury Cognac brand. J. Vacat. Mark. 2023, 31, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulding, C. The museum environment and the visitor experience. Eur. J. Mark. 2000, 34, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyall, A.; Garrod, B.; Leask, A.; Wanhill, S. Managing Visitor Attractions; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sathyanarayanan, H.; Jiang, Y.; Caldas, L.; Cheshire, C. Visual engagement and comfort perceptions in pediatric patient rooms: A virtual reality and eye-tracking study using photographic stimuli. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2025, 18, 100636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linstone, H.A.; Turoff, M. The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Delbecq, A.L.; Van de Ven, A.H.; Gustafson, D.H. Group Techniques for Program Planning: A Guide to Nominal Group and Delphi Processes; Scott, Foresman and Company: Glenview, IL, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Lawshe, C.H. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers. Psychol. 1975, 28, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S. Studying actions in context: A qualitative shadowing method for organizational research. Qual. Res. 2005, 5, 455–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, D.; Vásquez, C. On shadowing the hybrid character of actions: A communicational approach. Commun. Methods Meas. 2008, 2, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, H.J. Tracking visitor circulation in museum settings. Environ. Behav. 1993, 25, 782–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanir, J.; Kuflik, T.; Sheidin, J.; Yavin, N.; Leiderman, K.; Segal, M. Visualizing museum visitors’ behavior: Where do they go and what do they do there? Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2017, 21, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirris, S.; Lindheim, T.; Askeland, H. Observation and shadowing: Two methods to research values and values work in organisations and leadership. In Researching Values: Methodological Approaches for Understanding Values Work in Organisations and Leadership; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalowitz, S.S.; Bronnenkant, K. Timing and tracking: Unlocking visitor behavior. Visit. Stud. 2009, 12, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yum, J.; Hung, Y.H.; Lee, J.H. Optimizing Tourism Factory Design: A Strategic Framework for Enhancing Visitor Experience Through Spatial Zoning and Visual Graph Analysis. In Proceedings of the DS 136: Asia Design and Innovation Conference (ADIC) 2024, Shanghai, China, 5–6 December 2024; pp. 379–389. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnsteinsson, Á. Analysis of an Assembly Process of Electric Detonators with Application of Lean Manufacturing. Master’s Thesis, Royal School of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Joffe, H. Thematic analysis. In Qualitative Research Methods in Mental Health and Psychotherapy: A Guide for Students and Practitioners; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2011; pp. 209–223. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Zimring, C. Can intensive care staff see their patients? An improved visibility analysis methodology. Environ. Behav. 2012, 44, 861–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A. Depthmap 4: A Researcher’s Handbook; Bartlett School of Graduate Studies, University College London: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

| N | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 35 | 40 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min. | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.75 | 0.78 | 0.62 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.49 | 0.42 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.29 |

| Number | Subarea | Visit Path | Visit Time | Behavior | Total Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | subarea 2 | 1 | 30 sec | Observing | 35 min |

| City / Country | Company | Sector | Subareas |

|---|---|---|---|

| Osan, Republic of Korea | Amore Factory | Cosmetics | Introduction of Founder/CEO, Photo Zone, Company History, Company Product History, DIY, Manufacturing Equipment, Manufacturing Process |

| Tainan, Taiwan | Eminent Luggage Tourist Factory | Luggage | Photo Zone, Introduction of Founder/CEO, Company History, Company Product History, Manufacturing Equipment, Manufacturing Process, Company Product Line, Quiz, DIY, Cafe, Goods Shop |

| Sabae, Japan | Megane Museum | Eyewear | Introduction of Founder/CEO, Company History, Company Product History, Entire Product History, Manufacturing Equipment, DIY, Cafe, Goods Shop, Company Product Line |

| Osaka, Japan | Shiseido Factory | Cosmetics | Manufacturing Process, Company Product History, Hands-on Activity, DIY, Company History, Photo Zone, Manufacturing Equipment, Manufacturing Process, Company Product Line |

| Oberkochen, Germany | ZEISS Museum | Eyewear | Company History, Company Product History, Goods Shop, Hands-on Activity, Company Product Line, Photo Zone |

| Lake Forest, USA | Oakley Factory Tour | Eyewear | Introduction of Founder/CEO, Company History, Hands-on Activity, Manufacturing Process, Company Product History, Goods Shop, Company Product Line, Cafe |

| Rank | Subarea | Number of Likes | Number of Dislikes | Net Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | 41 | 6 | 35 |

| 2 | 8 | 44 | 15 | 29 |

| 3 | 17 | 34 | 11 | 23 |

| 4 | 3 | 24 | 7 | 17 |

| 5 | 20 | 18 | 8 | 10 |

| 6 | 16 | 19 | 10 | 9 |

| 7 | 19 | 9 | 7 | 2 |

| 8 | 2 | 11 | 10 | 1 |

| 9 | 21 | 8 | 10 | −2 |

| 10 | 15 | 11 | 13 | −2 |

| 11 | 6 | 17 | 19 | −2 |

| 12 | 7 | 5 | 9 | −4 |

| 13 | 12 | 11 | 17 | −6 |

| 14 | 11 | 3 | 14 | −11 |

| 15 | 4 | 7 | 18 | −11 |

| 16 | 9 | 7 | 20 | −13 |

| 17 | 5 | 3 | 16 | −13 |

| 18 | 14 | 2 | 16 | −14 |

| 19 | 1 | 2 | 17 | −15 |

| 20 | 13 | 22 | 38 | −16 |

| 21 | 18 | 7 | 25 | −18 |

| Zone | Key Subareas | Subareas of Eye Fun Vision | Order |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heritage·History | Company Founding Background & MVC; Company History; Company Product History | See Hwa Meei; Domestic Eyeglasses Industry; Hwa Meei Enterprise Timeline | 2 |

| Manufacture·Product | Manufacturing Process; Company Product Line Archive | Celebrity Wall; Four Types of Eyeglasses Display; Glasses Produce | 3 |

| Experience | Hands-on & Interactive Activity; DIY Workshop | Glasses DIY; Hand Eye Coordination Toy; Different Eye Pathologies; Sports Vision; Firsthand Experiences for Colored Lenses; 3D Glasses Experience; Amplitude of Accommodation Testing; Laser Lens Resolution Test; UV Lens Tester; Impact Resistance Test of PC Lenses; Army Protective Eyewear | 4 |

| Convenience | Goods Shop; Cafe | Glasses Shop; Vending Cart | 5 |

| — | Information Desk ** | — | 1 |

| — | Photo Zone * | Owl Collection Display; 3D Painted Wall | * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yum, J.; Hung, Y.-H.; Lee, J.-H. A Hybrid Spatial–Experiential Design Framework for Sustainable Factory Tours: A Case Study of the Optical Lens Manufacturer. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310650

Yum J, Hung Y-H, Lee J-H. A Hybrid Spatial–Experiential Design Framework for Sustainable Factory Tours: A Case Study of the Optical Lens Manufacturer. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310650

Chicago/Turabian StyleYum, Joosun, Yu-Hsiu Hung, and Ji-Hyun Lee. 2025. "A Hybrid Spatial–Experiential Design Framework for Sustainable Factory Tours: A Case Study of the Optical Lens Manufacturer" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310650

APA StyleYum, J., Hung, Y.-H., & Lee, J.-H. (2025). A Hybrid Spatial–Experiential Design Framework for Sustainable Factory Tours: A Case Study of the Optical Lens Manufacturer. Sustainability, 17(23), 10650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310650