Mapping Existing Modelling Approaches to Maritime Decarbonisation Using Latent Dirichlet Allocation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Literature Review

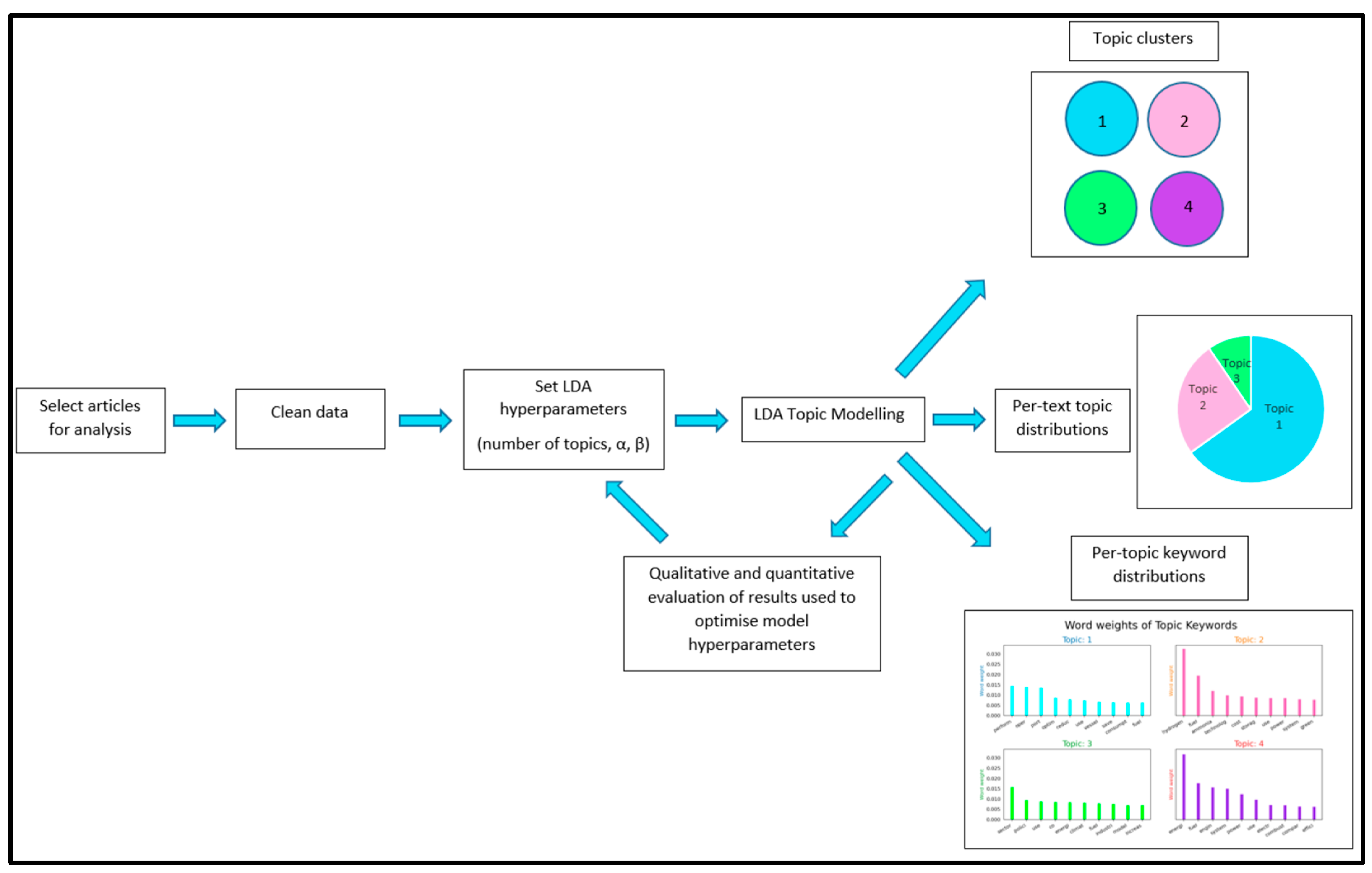

3. Materials and Methods

- Choose N~Poisson (ξ);

- Choose θ~Dir (α);

- For each of the N words wn;

- Choose a topic zn~Multinomial (θ);

- Choose a word wn from p (wn|zn, β), a multinomial probability conditioned on the topic zn.

4. Results and Discussion

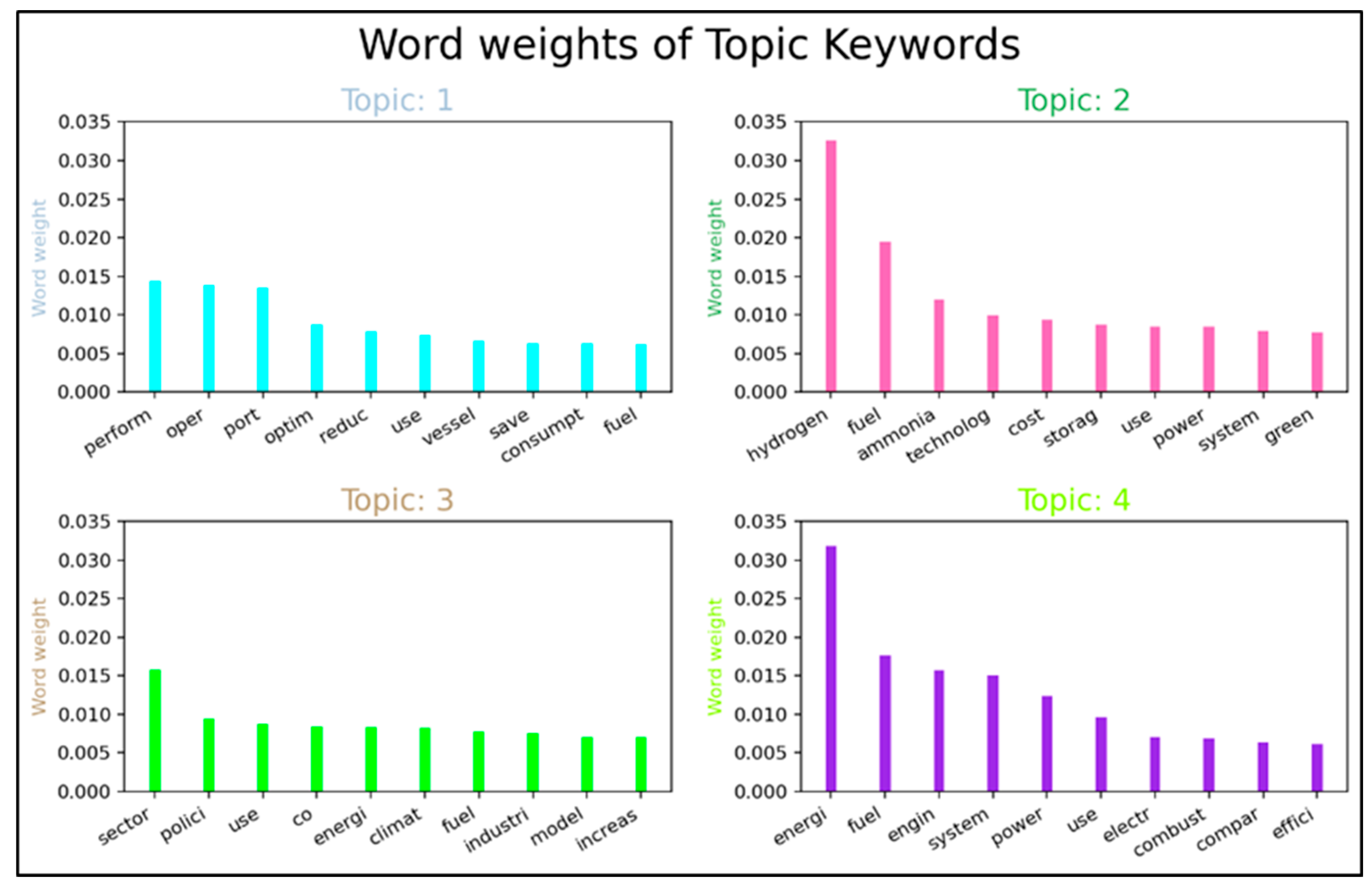

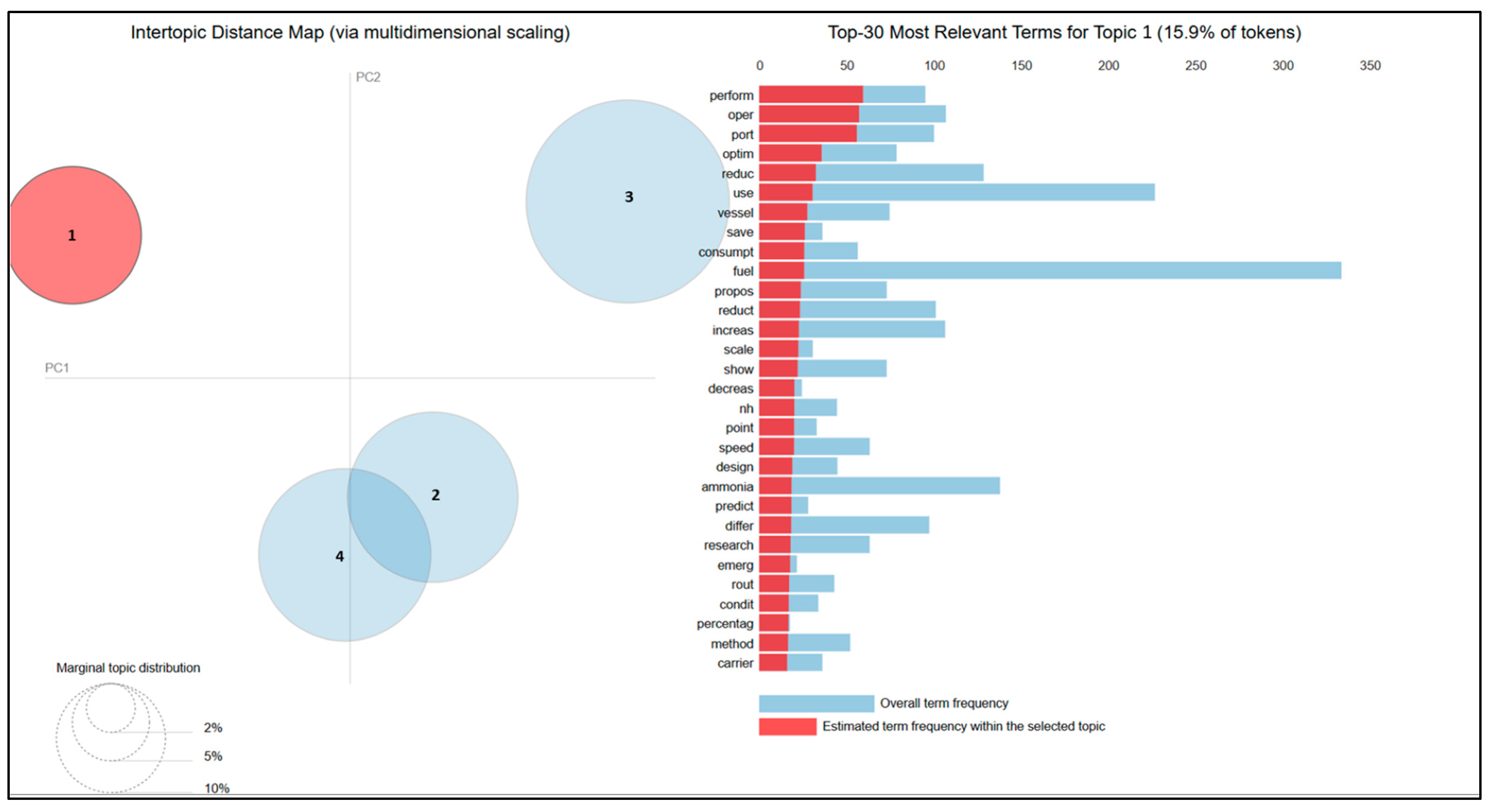

4.1. Per-Topic Word Distributions

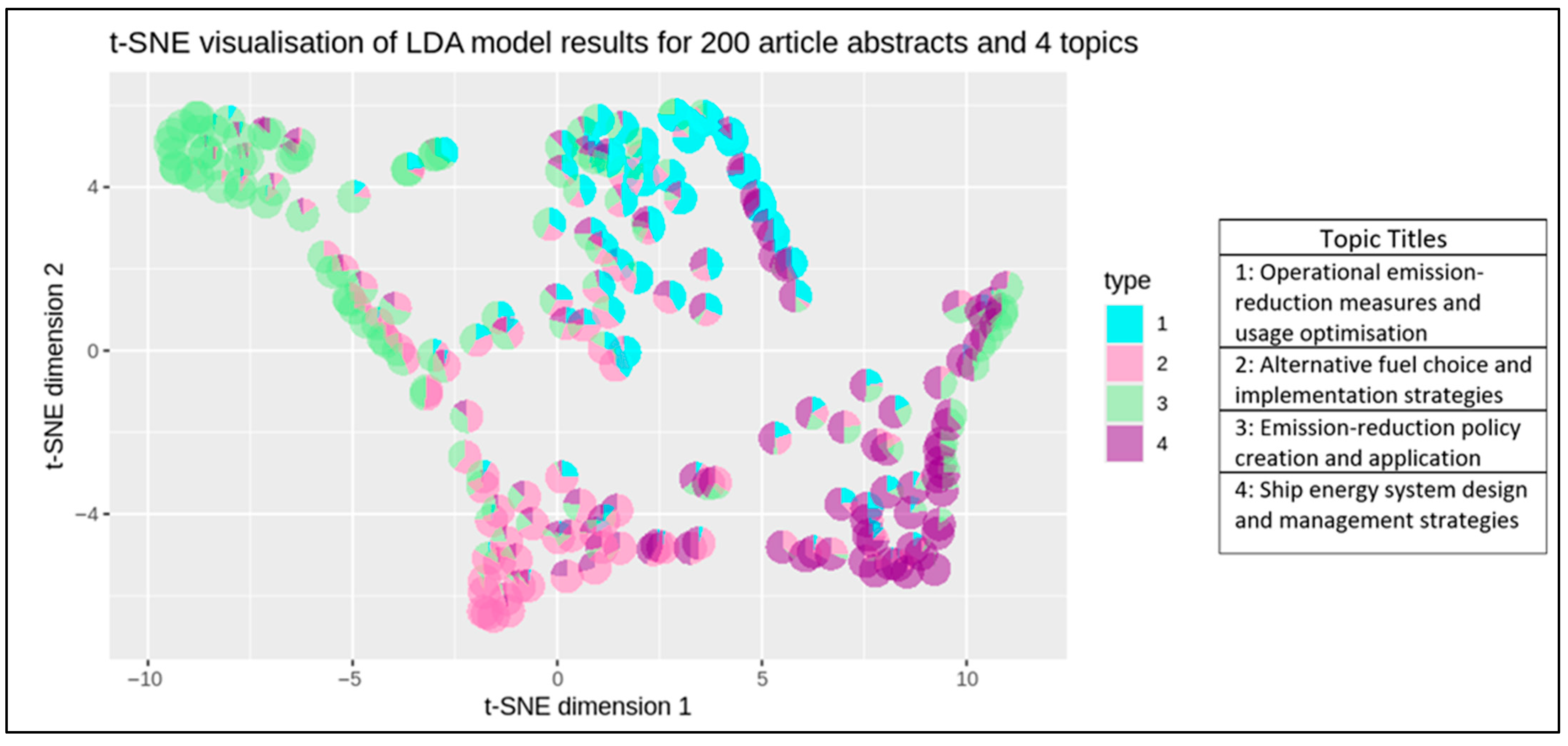

4.2. Per-Text Topic Distributions

5. Conclusions and Future Research Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maersk-McKinney Møller Centre for Zero Carbon Shipping. Available online: https://www.zerocarbonshipping.com/publications/maritime-decarbonization-strategy (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- International Maritime Organization. Fourth IMO Greenhouse Gas Study; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- International Maritime Organization. Annex 15 Resolution MEPC.377 (80) 2023 IMO Strategy on Reduction of GHG Emissions from Ships; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- The International Council on Clean Transportation. Available online: https://theicct.org/marine-imo-updated-ghg-strategy-jul23/ (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent Dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zis, T.P.V.; Psaraftis, H.N.; Ding, L. Ship weather routing: A taxonomy and survey. Ocean. Eng. 2020, 213, 107697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Fang, Z.; Fu, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, J. Literature review on emission control-based ship voyage optimization. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 93, 102768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, M.; Ventura, M.; Guedes Soares, C. Review of the Decision Support Methods Used in Optimizing Ship Hulls towards Improving Energy Efficiency. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivyza, N.L.; Rentizelas, A.; Theotokatos, G.; Boulougouris, E. Decision support methods for sustainable ship energy systems: A state-of-the-art review. Energy 2022, 239, 122288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, M.; Brunton, L. The Optimal Route: The Why and How of Digital Decarbonisation in Shipping; Thetius: London, UK, 2022; Available online: https://thetius.com/the-optimal-route (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Pakkanen, P.; Vettor, R. Decarbonization Support from Digital Solutions Providers. In Maritime Decarbonization: Practical Tools, Case Studies and Decarbonization Enablers; Lind, M., Lehmacher, W., Ward, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 403–416. [Google Scholar]

- Balcombe, P.; Brierley, J.; Lewis, C.; Skatvedt, L.; Speirs, J.; Hawkes, A.; Staffell, I. How to decarbonise international shipping: Options for fuels, technologies and policies. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 182, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chica, M.; Hermann, R.R.; Lin, N. Adopting different wind-assisted ship propulsion technologies as fleet retrofit: An agent-based modeling approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 192, 122559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karountzos, O.; Kagkelis, G.; Kepaptsoglou, K. A Decision Support GIS Framework for Establishing Zero-Emission Maritime Networks: The Case of the Greek Coastal Shipping Network. J. Geovisualization Spat. Anal. 2023, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Thellufsen, J.Z.; Zakeri, B.; Pickering, B.; Pfenninger, S.; Lund, H.; Østergaard, P.A. Trends in tools and approaches for modelling the energy transition. Appl. Energy 2021, 290, 116731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, D.; Lund, H.; Mathiesen, B.V.; Leahy, M. A review of computer tools for analysing the integration of renewable energy into various energy systems. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 1059–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deerwester, S.; Dumais, S.T.; Furnas, G.W.; Landauer, T.K.; Harshman, R. Indexing by latent semantic analysis. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Tech. 1990, 41, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayansky, I.; Kumar, S.A.P. A review of topic modeling methods. Inf. Syst. 2020, 94, 101582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankar, M.; Kasri, M.; Beni-Hssane, A. A comprehensive overview of topic modeling: Techniques, applications and challenges. Neurocomputing 2025, 628, 129638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.G.V.; Kotsia, I.; Patras, I. Max-margin Non-negative Matrix Factorization. Image Vis. Comput. 2012, 30, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, T. Unsupervised Leaning by Probabilistic Latent Semantic Analysis. Mach. Learn. 2001, 42, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, T. Probabilistic Latent Semantic Indexing. SIGIR Forum 2017, 51, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M.; Lafferty, J.D. Correlated Topic Models. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 4–7 December 2006; Schölkopf, B., Platt, J.C., Hoffman, T., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Blei, D.M.; Lafferty, J.D. A correlated topic model of Science. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2007, 1, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, C.E. Mixing Dirichlet Topic Models and Word Embeddings to Make lda2vec. arXiv 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootendorst, M. BERTopic: Neural topic modelling with a class-based TF-IDF procedure. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelov, D. Top2Vec: Distributed Representations of Topics. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmussen, C.B.; Moller, C. Smart literature review: A practical topic modelling approach to exploratory literature review. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghani, M.; Sprei, F.; Kazemzadeh, K.; Shahhoseini, Z.; Aghaei, J. Trends in electric vehicles research. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 123, 103881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acanfora, M.; Altosole, M.; Balsamo, F.; Micoli, L.; Campora, U. Simulation Modeling of a Ship Propulsion System in Waves for Control Purposes. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acciaro, M.; McKinnon, A.C. Carbon emissions from shipping: An analysis of new empirical evidence. Int. J. Transp. Econ. 2015, 42, 211–228. [Google Scholar]

- Adumene, S.; Islam, R.; Amin, M.T.; Nitonye, S.; Yazdi, M.; Johnson, K.T. Advances in nuclear power system design and fault-based condition monitoring towards safety of nuclear-powered ships. Ocean. Eng. 2022, 251, 111156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afewerki, S.; Karlsen, A. Policy mixes for just sustainable development in regions specialized in carbon-intensive industries: The case of two Norwegian petro-maritime regions. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2022, 30, 2273–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamoush, A.S.; Ballini, F.; Olcer, A.I. Ports’ technical and operational measures to reduce greenhouse gas emission and improve energy efficiency: A review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 160, 111508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamoush, A.S.; Olcer, A.I.; Ballini, F. Port greenhouse gas emission reduction: Port and public authorities? implementation schemes. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2020, 43, 100708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, M.; Lister, J.; Gillen, D. Toward a harmonization of sustainability criteria for alternative marine fuels. Marit. Transp. Res. 2022, 3, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autelitano, K.; Famiglietti, J.; Toppi, T.; Motta, M. Empirical power-law relationships for the Life Cycle Assessment of heat pump units. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2023, 10, 100135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balci, G.; Phan, T.T.N.; Surucu-Balci, E.; Iris, C. A roadmap to alternative fuels for decarbonising shipping: The case of green ammonia. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2024, 53, 101100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcombe, P.; Speirs, J.F.; Brandon, N.P.; Hawkes, A.D. Methane emissions: Choosing the right climate metric and time horizon. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2018, 20, 1323–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basic, B.B.; Krcum, M.; Gudelj, A. Adaptation of Existing Vessels in Accordance with Decarbonization Requirements-Case Study-Mediterranean Port. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman-Fonte, C.; da Silva, G.N.; Imperio, M.; Draeger, R.; Coutinho, L.; Cunha, B.S.L.; Rochedo, P.R.R.; Szklo, A.; Schaeffer, R. Repurposing, co-processing and greenhouse gas mitigation-The Brazilian refining sector under deep decarbonization scenarios: A case study using integrated assessment modeling. Energy 2023, 282, 128435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botana, C.; Fernandez, E.; Feijoo, G. Towards a Green Port strategy: The decarbonisation of the Port of Vigo (NW Spain). Sci. Tot. Environ. 2023, 856, 159198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bows-Larkin, A. All adrift: Aviation, shipping, and climate change policy. Clim. Policy 2015, 15, 681–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, K.Q.; Perera, L.P.; Emblemsvag, J. Life-cycle cost analysis of an innovative marine dual-fuel engine under uncertainties. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 134847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulak, M.E. A Frontier Approach to Eco-Efficiency Assessment in the World’s Busiest Sea Ports. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonomano, A.; Del Papa, G.; Giuzio, G.F.; Palombo, A.; Russo, G. Future pathways for decarbonization and energy efficiency of ports: Modelling and optimization as sustainable energy hubs. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 420, 138389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calise, F.; Duic, N.; Pfeifer, A.; Vicidomini, M.; Orlando, A.M. Moving the system boundaries in decarbonization of large islands. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 234, 113956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvillo, C.; Race, J.; Chang, E.; Turner, K.; Katris, A. Characterisation of UK Industrial Clusters and Techno-Economic Cost Assessment for Carbon Dioxide Transport and Storage Implementation. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2022, 119, 103695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameretti, M.C.; De Robbio, R.; Palomba, M. Numerical Analysis of Dual Fuel Combustion in a Medium Speed Marine Engine Supplied with Methane/Hydrogen Blends. Energies 2023, 16, 6651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardemil, J.M.; Calderon-Vasquez, I.; Pino, A.; Starke, A.; Wolde, I.; Felbol, C.; Lemos, L.F.L.; Bonini, V.; Arias, I.; Inigo-Labairu, J.; et al. Assessing the Uncertainties of Simulation Approaches for Solar Thermal Systems Coupled to Industrial Processes. Energies 2022, 15, 3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlou, M.; Babarit, A.; Gentaz, L. A new validated open-source numerical tool for the evaluation of the performance of wind-assisted ship propulsion systems. Mech. Ind. 2023, 24, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Zheng, S.; Chen, Y. Exploring Drivers Shaping the Choice of Alternative-Fueled New Vessels. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chircop, A. The IMO Initial Strategy for the Reduction of GHGs from International Shipping: A Commentary. Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 2019, 34, 482–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, A.; Cullinane, K. Potential for, and drivers of, private voluntary initiatives for the decarbonisation of short sea shipping: Evidence from a Swedish ferry line. Mar. Econ. Logist. 2021, 23, 632–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’Armi, C.; Micheli, D.; Taccani, R. Comparison of different plant layouts and fuel storage solutions for fuel cells utilization on a small ferry. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 13878–13897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damman, S.; Sandberg, E.; Rosenberg, E.; Pisciella, P.; Graabak, I. A hybrid perspective on energy transition pathways: Is hydrogen the key for Norway? Energy. Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 78, 102116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, A.; De Leon, R.; Krishnamoorti, R. Advancing carbon management through the global commoditization of CO2: The case for dual-use LNG-CO2 shipping. Carbon. Manag. 2020, 11, 611–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Fournas, N.; Wei, M. Techno-economic assessment of renewable methanol from biomass gasification and PEM electrolysis for decarbonization of the maritime sector in California. Energy. Convers. Manag. 2022, 257, 115440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Manuel-Lopez, F.; Diaz-Gutierrez, D.; Camarero-Orive, A.; Parra-Santiago, J.I. Iberian Ports as a Funnel for Regulations on the Decarbonization of Maritime Transport. Sustainability 2024, 16, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Micco, S.; Cigolotti, V.; Mastropasqua, L.; Brouwer, J.; Minutillo, M. Ammonia-powered ships: Concept design and feasibility assessment of powertrain systems for a sustainable approach in maritime industry. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 22, 100539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, G.H.S.; Miranda, V.d.S.; Carmo, B.S. Dynamic modelling, simulation, and control of hybrid power systems for escort tugs and shuttle tankers. J. Energy. Storage 2023, 72, 108091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Buzuku, S.; Elg, M.; Schonborn, A.; Olcer, A.I. Environmental Performance of Bulk Carriers Equipped with Synergies of Energy-Saving Technologies and Alternative Fuels. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, J.-O.; Yoon, J.-H.; Yeon, J.-H.; Kim, S.-W. Port Digital Twin Development for Decarbonization: A Case Study Using the Pusan Newport International Terminal. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, A.; Yan, X.; Bucknall, R.; Yin, Q.; Ji, S.; Liu, Y.; Song, R.; Chen, X. A novel ship energy efficiency model considering random environmental parameters. J. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2020, 19, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Enshaei, H.; Jayasinghe, S.G.; Tan, S.H.; Zhang, C. Quantitative risk assessment for ammonia ship-to-ship bunkering based on Bayesian network. Process Saf. Prog. 2022, 41, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foretich, A.; Zaimes, G.G.; Hawkins, T.R.; Newes, E. Challenges and opportunities for alternative fuels in the maritime sector. Mar. Transp. Res. 2021, 2, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragkos, P. Decarbonizing the International Shipping and Aviation Sectors. Energies 2022, 15, 9650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, S.; Bramstoft, R. Impact of endogenous learning curves on maritime transition pathways. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 054014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frkovic, L.; Cosic, B.; Puksec, T.; Vladimir, N. The synergy between the photovoltaic power systems and battery-powered electric ferries in the isolated energy system of an island. Energy 2022, 259, 124862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillingham, K.T.; Huang, P. Long-Run Environmental and Economic Impacts of Electrifying Waterborne Shipping in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 9824–9833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godet, A.; Nurup, J.N.; Saber, J.T.; Panagakos, G.; Barfod, M.B. Operational cycles for maritime transportation: A benchmarking tool for ship energy efficiency. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 121, 103840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, S.; Vijayakumar, R. Computational Analysis of the Effect of Hull Vane on Hydrodynamic Performance of a Medium-speed Vessel. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 2023, 22, 762–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groppi, D.; Kannan, S.K.P.; Gardumi, F.; Garcia, D.A. Optimal planning of energy and water systems of a small island with a hourly OSeMOSYS model. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 276, 116541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groppi, D.; Nastasi, B.; Prina, M.G. The EPLANoptMAC model to plan the decarbonisation of the maritime transport sector of a small island. Energy 2022, 254, 124342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Chen, J.; Chen, L.; Cao, J.; Fan, H. Safe Design of a Hydrogen-Powered Ship: CFD Simulation on Hydrogen Leakage in the Fuel Cell Room. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, M.; Petetin, H.; Jorba, O.; van der Gon, H.D.; Kuenen, J.; Super, I.; Granier, C.; Doumbia, T.; Ciais, P.; Liu, Z.; et al. Towards near-real-time air pollutant and greenhouse gas emissions: Lessons learned from multiple estimates during the COVID-19 pandemic. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 8081–8101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, R.A.; Kirstein, L.; Merk, O.; Martinez, L.M. Decarbonization Pathways for International Maritime Transport: A Model-Based Policy Impact Assessment. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, J.; Brynolf, S.; Fridell, E.; Lehtveer, M. The Potential Role of Ammonia as Marine Fuel-Based on Energy Systems Modeling and Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harahap, F.; Nurdiawati, A.; Conti, D.; Leduc, S.; Urban, F. Renewable marine fuel production for decarbonised maritime shipping: Pathways, policy measures and transition dynamics. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 415, 137906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harichandan, S.; Kar, S.K.; Rai, P.K. A systematic and critical review of green hydrogen economy in India. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 31425–31442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, G.; Zheng, P. Dynamic analysis of a low-carbon maritime supply chain considering government policies and social preferences. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2023, 239, 106564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, I.; Park, C.; Jeong, B. Life Cycle Cost Analysis for Scotland Short-Sea Ferries. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhoff, T.B.; Gkantonas, S.; Mastorakos, E. Analysing the Performance of Ammonia Powertrains in the Marine Environment. Energies 2021, 14, 7447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, H.; Shehzad, M.F.; Crawford, C. Transient modeling of a green ammonia production system to support sustainable development. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 39254–39270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.; Brodal, E. Optimization of a Mixed Refrigerant Based H2 Liquefaction Pre-Cooling Process and Estimate of Liquefaction Performance with Varying Ambient Temperature. Energies 2021, 14, 6090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kany, M.S.; Mathiesen, B.V.; Skov, I.R.; Korberg, A.D.; Thellufsen, J.Z.; Lund, H.; Sorknaes, P.; Chang, M. Energy efficient decarbonisation strategy for the Danish transport sector by 2045. Smart Energy 2022, 5, 100063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasevich, V.A.; Elistratov, V.V.; Lopatin, A.S.; Mingaleeva, R.D.; Ternikov, O.V.; Putilova, I.V. Technological aspects of Russian hydrogen energy development. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 57, 1332–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karountzos, O.; Kagkelis, G.; Iliopoulou, C.; Kepaptsoglou, K. GIS-based analysis of the spatial distribution of CO2 emissions and slow steaming effectiveness in coastal shipping. Air. Qual. Atmos. Health 2024, 17, 661–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvounis, P.; Theotokatos, G.; Boulougouris, E. Environmental-economic sustainability of hydrogen and ammonia fuels for short sea shipping operations. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 57, 1070–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazi, M.-K.; Eljack, F. Practicality of Green H2 Economy for Industry and Maritime Sector Decarbonization through Multiobjective Optimization and RNN-LSTM Model Analysis. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 6173–6189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazi, M.-K.; Eljack, F.; El-Halwagi, M.M.; Haouri, M. Green hydrogen for industrial sector decarbonization: Costs and impacts on hydrogen economy in qatar. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2021, 145, 107144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kistner, L.; Schubert, F.L.; Minke, C.; Bensmann, A.; Hanke-Rauschenbach, R. Techno-economic and Environmental Comparison of Internal Combustion Engines and Solid Oxide Fuel Cells for Ship Applications. J. Power Sources 2021, 508, 230328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, M.; Blanco-Davis, E.; Platt, O.; Armin, M. Life-Cycle and Applicational Analysis of Hydrogen Production and Powered Inland Marine Vessels. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, J.; Doenitz, E.; Schaetter, F. Transitions for ship propulsion to 2050: The AHOY combined qualitative and quantitative scenarios. Mar. Policy 2022, 140, 105049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondratenko, A.A.; Kulkarni, K.; Li, F.; Musharraf, M.; Hirdaris, S.; Kujala, P. Decarbonizing shipping in ice by intelligent icebreaking assistance: A case study of the Finnish-Swedish winter navigation system. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 286, 115652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koray, M. Assessment of dry bulk carriers regarding decarbonisation and entropy management. Sh. Offshore Struct. 2024, 19, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korican, M.; Frkovic, L.; Vladimir, N. Electrification of fishing vessels and their integration into isolated energy systems with a high share of renewables. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 425, 138997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korican, M.; Vladimir, N.; Fan, A. Investigation of the energy efficiency of fishing vessels: Case study of the fishing fleet in the Adriatic Sea. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 286, 115734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramel, D.; Franz, S.M.; Klenner, J.; Muri, H.; Munster, M.; Stromman, A.H. Advancing SSP-aligned scenarios of shipping toward 2050. Sci. Rep 2024, 14, 8965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramel, D.; Muri, H.; Kim, Y.; Lonka, R.; Nielsen, J.B.; Ringvold, A.L.; Bouman, E.A.; Steen, S.; Stromman, A.H. Global Shipping Emissions from a Well-to-Wake Perspective: The MariTEAM Model. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 15040–15050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzykowska-Piotrowska, K.; Piotrowski, M.; Organigciak-Krzykowska, A.; Kwiatkowska, E. Maritime or Rail: Which of These Will Save the Planet? EU Macro-Regional Strategies and Reality. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagouvardou, S.; Psaraftis, H.N.; Zis, T. Impacts of a bunker levy on decarbonizing shipping: A tanker case study. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2022, 106, 103257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, L.C.; Foscoli, B.; Mastorakos, E.; Evans, S. A Comparison of Alternative Fuels for Shipping in Terms of Lifecycle Energy and Cost. Energies 2021, 14, 8502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, L.C.; Mastorakos, E.; Evans, S. Estimates of the Decarbonization Potential of Alternative Fuels for Shipping as a Function of Vessel Type, Cargo, and Voyage. Energies 2022, 15, 7468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, L.C.; Mastorakos, E.; Othman, M.R.; Trakakis, A. A Thermodynamics Model for the Assessment and Optimisation of Onboard Natural Gas Reforming and Carbon Capture. Emiss. Control Sci. Technol. 2024, 10, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedevas, S.; Milasius, E. Methodological Aspects of Assessing the Thermal Load on Diesel Engine Parts for Operation on Alternative Fuel. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedevas, S.; Zaglinskis, J.; Drazdauskas, M. Development and Validation of Heat Release Characteristics Identification Method of Diesel Engine under Operating Conditions. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblanc, F.; Bibas, R.; Mima, S.; Muratori, M.; Sakamoto, S.; Sano, F.; Bauer, N.; Daioglou, V.; Fujimori, S.; Gidden, M.J.; et al. The contribution of bioenergy to the decarbonization of transport: A multi-model assessment. Clim. Change 2022, 170, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T.; Nguyen, H.P.; Rudzki, K.; Rowinski, L.; Bui, V.D.; Truong, T.H.; Le, H.C.; Pham, N.D.K. Management Strategy for Seaports Aspiring to Green Logistical Goals of IMO: Technology and Policy Solutions. Pol. Marit. Res. 2023, 30, 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jia, P.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Kuang, H. Ship carbon dioxide emission estimation in coastal domestic emission control areas using high spatial-temporal resolution data: A China case. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2023, 232, 106419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Fagerholt, K.; Schutz, P. Stochastic tramp ship routing with speed optimization: Analyzing the impact of the Northern Sea Route on CO2 emissions. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 350, 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Kou, Y.; Luo, M.; Li, L. Switching fuel or scrubbing up? A mixed compliance strategy with the 2020 global sulphur limit. Ocean Coast Manag 2023, 244, 106829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Lee, C.; Lee, W.-J.; Choi, J.; Jung, D.; Jeon, Y. Valuation of the Extension Option in Time Charter Contracts in the LNG Market. Energies 2022, 15, 6737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippkau, F.; Franzmann, D.; Addanki, T.; Buchenberg, P.; Heinrichs, H.; Kuhn, P.; Hamacher, T.; Blesl, M. Global Hydrogen and Synfuel Exchanges in an Emission-Free Energy System. Energies 2023, 16, 3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q. Emissions in maritime transport: A decomposition analysis from the perspective of production-based and consumption-based emissions. Mar. Policy 2022, 143, 105125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. The supervision and multi-sectoral guarantee mechanism of the global marine sulphur limit-assessment from Chinese shipping industry. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1028388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.; Skov, I.R.; Thellufsen, J.Z.; Sorknaes, P.; Korberg, A.D.; Chang, M.; Mathiesen, B.V.; Kany, M.S. The role of sustainable bioenergy in a fully decarbonised society. Renew. Energy 2022, 196, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallouppas, G.; Yfantis, E.A.; Ktoris, A.; Ioannou, C. Methodology to Assess the Technoeconomic Impacts of the EU Fit for 55 Legislation Package in Relation to Shipping. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmgren, E.; Brynolf, S.; Styhre, L.; van der Holst, J. Navigating unchartered waters: Overcoming barriers to low-emission fuels in Swedish maritime cargo transport. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 106, 103321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannarini, G.; Salinas, M.L.; Carelli, L.; Fasso, A. How COVID-19 Affected GHG Emissions of Ferries in Europe. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrero, A.; Martinez-Lopez, A. Decarbonization of Short Sea Shipping in European Union: Impact of market and goal based measures. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 421, 138481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Zhao, H.; Wang, K.; Zhang, R.; Hua, Y.; Jiang, B.; Tian, F.; Ruan, Z.; Wang, H.; Huang, L. Leakage Fault Diagnosis of Lifting and Lowering Hydraulic System of Wing-Assisted Ships Based on WPT-SVM. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masodzadeh, P.G.; Olcer, A.I.; Dalaklis, D.; Ballini, F.; Christodoulou, A. Lessons Learned during the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Need to Promote Ship Energy Efficiency. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, J.; Larkin, A.; Gallego-Schmid, A. Mitigating stochastic uncertainty from weather routing for ships with wind propulsion. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 281, 114674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateus, C.; Flor, D.; Guerrero, C.A.; Cordova, X.; Benitez, F.L.; Parra, R.; Ochoa-Herrera, V. Anthropogenic emission inventory and spatial analysis of greenhouse gases and primary pollutants for the Galapagos Islands. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 68900–68918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, A. The possible influence of the shipper on carbon emissions from deep-sea container supply chains: An empirical analysis. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2014, 16, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Wang, X.; Jin, J.; Han, C. Optimization Model for Container Liner Ship Scheduling Considering Disruption Risks and Carbon Emission Reduction. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshiul, A.M.; Mohammad, R.; Hira, F.A. Alternative Fuel Selection Framework toward Decarbonizing Maritime Deep-Sea Shipping. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshiul, A.M.; Mohammad, R.; Hira, F.A.; Maarop, N. Alternative Marine Fuel Research Advances and Future Trends: A Bibliometric Knowledge Mapping Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrowczynska, M.; Skiba, M.; Lesnika, A.; Bazan-Krzywoszanska, A.; Janowiec, F.; Sztubecka, M.; Grech, R.; Kazak, J.K. A new fuzzy model of multi-criteria decision support based on Bayesian networks for the urban areas’ decarbonization planning. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 268, 116035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller-Casseres, E.; Carvalho, F.; Nogueira, T.; Fonte, C.; Imperio, M.; Poggio, M.; Wei, H.K.; Portugal-Pereira, J.; Rochedo, P.R.R.; Szklo, A.; et al. Production of alternative marine fuels in Brazil: An integrated assessment perspective. Energy 2021, 219, 119444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller-Casseres, E.; Edelenbosch, O.Y.; Szklo, A.; Schaeffer, R.; van Vuuren, D.P. Global futures of trade impacting the challenge to decarbonize the international shipping sector. Energy 2021, 237, 121547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller-Casseres, E.; Szklo, A.; Fonte, C.; Carvalho, F.; Portugal-Pereira, J.; Baptista, L.B.; Maia, P.; Rochedo, P.R.R.; Draeger, R.; Schaeffer, R. Are there synergies in the decarbonization of aviation and shipping? An integrated perspective for the case of Brazil. iScience 2022, 25, 105248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muslemani, H.; Liang, X.; Kaesehage, K.; Wilson, J. Business Models for Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage Technologies in the Steel Sector: A Qualitative Multi-Method Study. Processes 2020, 8, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.; Fu, X.; Ogawa, D.; Zheng, Q. An application-oriented testing regime and multi-ship predictive modeling for vessel fuel consumption prediction. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2023, 177, 103261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulos, L.; Boulougouris, E. Simulation-Driven Robust Optimization of the Design of Zero Emission Vessels. Energies 2023, 16, 4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulos, L.; Boulougouris, E. A novel method for the holistic, simulation driven ship design optimization under uncertainty in the big data era. Ocean. Eng. 2020, 218, 107634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panoutsou, C.; Giarola, S.; Ibrahim, D.; Verzandvoort, S.; Elbersen, B.; Sandford, C.; Malins, C.; Politi, M.; Vourliotakis, G.; Zita, V.E.; et al. Opportunities for Low Indirect Land Use Biomass for Biofuels in Europe. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomaska, L.; Acciaro, M. Bridging the Maritime-Hydrogen Cost-Gap: Real options analysis of policy alternatives. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2022, 107, 103283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prause, F.; Prause, G.; Philipp, R. Inventory Routing for Ammonia Supply in German Ports. Energies 2022, 15, 6485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prause, G.; Olaniyi, E.O.; Gerstlberger, W. Ammonia Production as Alternative Energy for the Baltic Sea Region. Energies 2023, 16, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psaraftis, H.N.; Kontovas, C.A. Decarbonization of Maritime Transport: Is There Light at the End of the Tunnel? Sustainability 2021, 13, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauca, L.; Batrinca, G. Impact of Carbon Intensity Indicator on the Vessels’ Operation and Analysis of Onboard Operational Measures. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, C.G.; Lamas, M.I.; Rodriguez, J.d.D.; Abbas, A. Multi-Criteria Analysis to Determine the Most Appropriate Fuel Composition in an Ammonia/Diesel Oil Dual Fuel Engine. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, C.G.; Lamas, M.I.; Rodriguez, J.d.D.; Abbas, A. Possibilities of Ammonia as Both Fuel and NOx Reductant in Marine Engines: A Numerical Study. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, H.H.; Schinas, O. Empirical evidence of the interplay of energy performance and the value of ships. Ocean. Eng. 2019, 190, 106403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Z.; Huang, L.; Wang, K.; Ma, R.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, H.; Wang, C. A novel prediction method of fuel consumption for wing-diesel hybrid vessels based on feature construction. Energy 2024, 286, 129516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, B.R.; Duong, P.A.; Kang, H. Comparative analysis of the thermodynamic performances of solid oxide fuel cellegas turbine integrated systems for marine vessels using ammonia and hydrogen as fuels. Int. J. of Nav. Archit. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 15, 100524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadakata, K.; Hino, T.; Takagi, Y. Estimation of full-scale performance of energy-saving devices using Boundary Layer Similarity model. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2024, 29, 245–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvucci, R.; Gargiulo, M.; Karlsson, K. The role of modal shift in decarbonising the Scandinavian transport sector: Applying substitution elasticities in TIMES-Nordic. Appl. Energy 2019, 253, 113593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinas, O.; Bergmann, N. The Short-Term Cost of Greening the Global Fleet. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, H.; Solakivi, T.; Gustafsson, M. Is There Business Potential for Sustainable Shipping? Price Premiums Needed to Cover Decarbonized Transportation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzkopf, D.A.; Petrik, R.; Hahn, J.; Ntziachristos, L.; Matthias, V.; Quante, M. Future Ship Emission Scenarios with a Focus on Ammonia Fuel. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seck, G.S.; Hache, E.; Sabathier, J.; Guedes, F.; Reigstad, G.A.; Straus, J.; Wolfgang, O.; Ouassou, J.A.; Askeland, M.; Hjorth, I.; et al. Hydrogen and the decarbonization of the energy system in europe in 2050: A detailed model-based analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, O.; Tingas, E.-A. Computational investigation of ammonia-hydrogen peroxide blends in HCCI engine mode. Int. J. Engine Res. 2023, 24, 2279–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, T.; Peng, T.; Zhu, L.; Lu, Y.; Wang, L.; Pan, X. China’s transportation decarbonization in the context of carbon neutrality: A segment-mode analysis using integrated modelling. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 105, 107392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, T.; Xu, Y. Domestic and international CO2 source-sink matching for decarbonizing India’s electricity. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 174, 105824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmina, M.; Edelenbosch, O.Y.; Wilson, C.; Freeman, R.; Gernaat, D.E.H.J.; Gilbert, P.; Larkin, A.; Littleton, E.W.; Traut, M.; van Vuuren, D.P.; et al. Decarbonising the critical sectors of aviation, shipping, road freight and industry to limit warming to 1.5–2 °C. Clim. Policy 2021, 21, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinoda, T.; Budiyanto, M.A.; Sugimura, Y. Analysis of energy conservation by roof shade installations in refrigerated container areas. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 377, 134402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalmokaite, I.; Hassler, B. Dynamic capabilities and strategic reorientation towards decarbonisation in Baltic Sea shipping. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2020, 37, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavroulakis, P.J.; Koutsouradi, M.; Kyriakopoulou-Roussou, M.-C.; Manologlou, E.-A.; Tsioumas, V.; Papadimitriou, S. Decarbonization and sustainable shipping in a post COVID-19 world. Sci. Afr. 2023, 21, e01758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopford, M. Maritime governance: Piloting maritime transport through the stormy seas of climate change. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2022, 24, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strantzali, E.; Livanos, G.A.; Aravossis, K. A Comprehensive Multicriteria Evaluation Approach for Alternative Marine Fuels. Energies 2023, 16, 7498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, F.; Ji, F.; Xiong, Y. Energy and speed optimization of inland battery-powered ship with considering the dynamic electricity price and complex navigational environment. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, M.; Ventura, M.; Guedes Soares, C. Fuel Consumption Analysis of Single and Twin-Screw Propulsion Systems of a Bulk Carrier. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 2023, 22, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, M.; Ventura, M.; Soares, C.G. Optimization procedures for a twin controllable pitch propeller of a ROPAX ship at minimum fuel consumption. J. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2023, 22, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, M.; Ventura, M.; Soares, C.G. Review of current regulations, available technologies, and future trends in the green shipping industry. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 280, 114670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, M.; Vettor, R.; Ventura, M.; Soares, C.G. Effect of Propeller Cup on the Reduction of Fuel Consumption in Realistic Weather Conditions. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, H.-H.; Chang, Y.-H.; Chang, C.-W.; Wang, Y.-M. Analysis of the Carbon Intensity of Container Shipping on Trunk Routes: Referring to the Decarbonization Trajectory of the Poseidon Principle. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.C.D.; Harris, K.; Tifft, S.M.; Steward, D.; Kinchin, C.; Thompson, T.N. Adoption of biofuels for marine shipping decarbonization: A long-term price and scalability assessment. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2022, 16, 942–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Roman, D.; Dickie, R.; Robu, V.; Flynn, D. Prognostics and Health Management for the Optimization of Marine Hybrid Energy Systems. Energies 2020, 13, 4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R.R.; Gue, I.H.V.; Tapia, J.F.D.; Aviso, K.B. Bilevel optimization model for maritime emissions reduction. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 398, 136589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskar, B.; Sasmal, K.; Yiew, L.J. A case study for the assessment of fuel savings using speed optimization. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 274, 113990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten, K.H.; Kang, H.-S.; Siow, C.-L.; Goh, P.S.; Lee, K.-Q.; Huspi, S.H.; Soares, C.G. Automatic identification system in accelerating decarbonization of maritime transportation: The state-of-the-art and opportunities. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 289, 116232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trahey, L.; Brushett, F.R.; Balsara, N.P.; Ceder, G.; Cheng, L.; Chiang, Y.-M.; Hahn, N.T.; Ingram, B.J.; Minteer, S.D.; Moore, J.S.; et al. Energy storage emerging: A perspective from the Joint Center for Energy Storage Research. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 12550–12557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.T.; Browne, T.; Veitch, B.; Musharraf, M.; Peters, D. Route optimization for vessels in ice: Investigating operational implications of the carbon intensity indicator regulation. Mar. Policy 2023, 158, 105858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traut, M.; Gilbert, P.; Walsh, C.; Bows, A.; Filippone, A.; Stansby, P.; Wood, R. Propulsive power contribution of a kite and a Flettner rotor on selected shipping routes. Appl. Energy 2014, 113, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivyza, N.L.; Cheliotis, M.; Boulougouris, E.; Theotokatos, G. Safety and Reliability Analysis of an Ammonia-Powered Fuel-Cell System. Safety 2021, 7, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, K.; Katris, A.; Karim Zanhouo, A.; Calvillo, C.; Race, J. The potential importance of exploiting export markets for CO2 transport and storage services in realising the economic value of Scottish CCS. Local Econ. 2023, 38, 264–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, F.; Nurdiawati, A.; Harahap, F. Sector coupling for decarbonization and sustainable energy transitions in maritime shipping in Sweden. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 107, 103366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakili, S.; Schonborn, A.; Olcer, A.I. The road to zero emission shipbuilding Industry: A systematic and transdisciplinary approach to modern multi-energy shipyards. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 18, 100365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, C.I.; Martinez, A.; Oltra, R.; Gil, H.; Boronat, F.; Palau, C.E. Prediction of the Estimated Time of Arrival of container ships on short-sea shipping: A pragmatical analysis. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2022, 20, 2354–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschuur, J.; Salmon, N.; Hall, J.; Banares-Alcantara, R. Optimal fuel supply of green ammonia to decarbonise global shipping. Environ. Res. Infrastruc. Sustain. 2024, 4, 015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voniati, G.; Dimaratos, A.; Koltsakis, G.; Ntziachristos, L. Ammonia as a Marine Fuel towards Decarbonization: Emission Control Challenges. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Malmborg, F. At the controls: Politics and policy entrepreneurs in EU policy to decarbonize maritime transport. Rev. Policy Res. 2024, 42, 1243–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C.; Bows, A. Size matters: Exploring the importance of vessel characteristics to inform estimates of shipping emissions. Appl. Energy 2012, 98, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C.; Lazarou, N.-J.; Traut, M.; Price, J.; Raucci, C.; Sharmina, M.; Agnolucci, P.; Mander, S.; Gilbert, P.; Anderson, K.; et al. Trade and trade-offs: Shipping in changing climates. Mar. Policy 2019, 106, 103537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-N.; Nguyen, N.-A.-T.; Dang, T.-T.; Hsu, H.-P. Evaluating Sustainable Last-Mile Delivery (LMD) in B2C E-Commerce Using Two-Stage Fuzzy MCDM Approach: A Case Study from Vietnam. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 146050–146067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhong, M.; Wang, T.; Ge, Y.-E. Identifying industry-related opinions on shore power from a survey in China. Transp. Policy 2023, 134, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Hua, Y.; Huang, L.; Guo, X.; Liu, X.; Ma, Z.; Ma, R.; Jiang, X. A novel GA-LSTM-based prediction method of ship energy usage based on the characteristics analysis of operational data. Energy 2023, 282, 128910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-T.; Liu, H.; Lv, Z.-F.; Deng, F.-Y.; Xu, H.-L.; Qi, L.-J.; Shi, M.-S.; Zhao, J.-C.; Zheng, S.-X.; Man, H.-Y.; et al. Trade-linked shipping CO2 emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 945–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liang, C.; Aktas, T.U.; Shi, J.; Pan, Y.; Fang, S.; Lim, G. Joint Voyage Planning and Onboard Energy Management of Hybrid Propulsion Ships. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.D.B.; Cherubini, F.; Cavalett, O. Climate change mitigation of drop-in biofuels for deep-sea shipping under a prospective life-cycle assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 364, 132662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrle, L.; Wang, Y.; Boldrin, P.; Brandon, N.P.; Deutschmann, O.; Banerjee, A. Optimizing Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Performance to Re-evaluate Its Role in the Mobility Sector. ACS Environ. AU 2021, 2, 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Liu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Li, T.; Li, W. A digital twin framework for real-time ship routing considering decarbonization regulatory compliance. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 278, 114407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodfield, R.; Glover, S.; Watson, R.; Nockemann, P.; Stocker, R. Electro-thermal modelling of redox flow-batteries with electrolyte swapping for an electric ferry. J. Energy Storage 2022, 54, 105306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Li, T.; Chen, R.; Huang, S.; Xu, F.; Wang, B. Transient Performance of Gas-Engine-Based Power System on Ships: An Overview of Modeling, Optimization, and Applications. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Miao, B.; Chan, S.H. Feasibility assessment of a container ship applying ammonia cracker-integrated solid oxide fuel cell technology. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 27166–27176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhen, L. Joint Planning of Fleet Deployment, Ship Refueling, and Speed Optimization for Dual-Fuel Ships Considering Methane Slip. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhen, L. Nonlinear programming for fleet deployment, voyage planning and speed optimization in sustainable liner shipping. Electron. Res. Arch. 2022, 31, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhen, L.; Shao, W. Green Technology Adoption and Fleet Deployment for New and Aged Ships Considering Maritime Decarbonization. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wen, K.; Zou, X. Impacts of Shipping Carbon Tax on Dry Bulk Shipping Costs and Maritime Trades-The Case of China. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Zhen, L. Mathematical Optimization of Carbon Storage and Transport Problem for Carbon Capture, Use, and Storage Chain. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, H.; Liu, Q.; Wang, L.; Yang, L. Decision-Making on the Selection of Clean Energy Technology for Green Ships Based on the Rough Set and TOPSIS Method. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Lai, K. Role of carbon emission linked financial leasing in shipping decarbonization. Marit. Policy Manag. 2023, 52, 396–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Lai, K.; Wang, C. How to invest decarbonization technology in shipping operations? Evidence from a game-theoretic investigation. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2024, 251, 107076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Nielsen, C.P.; Song, S.; McElroy, M.B. Breaking the hard-to-abate bottleneck in China’s path to carbon neutrality with clean hydrogen. Nat. Energy 2022, 7, 955–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Chen, J.; Shi, J.; Jiang, X.; Zhou, S. Novel synergy mechanism for carbon emissions abatement in shipping decarbonization. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 127, 104059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Zhu, J.; Nian, V. Neural Network Modeling Based on the Bayesian Method for Evaluating Shipping Mitigation Measures. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Wang, S.; Peng, J. Operational efficiency optimization method for ship fleet to comply with the carbon intensity indicator (CII) regulation. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 286, 115487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepter, J.M.; Engelhardt, J.; Marinelli, M. Optimal expansion of a multi-domain virtual power plant for green hydrogen production to decarbonise seaborne passenger transportation. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2023, 36, 101236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhu, J.; Guo, H.; Xue, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, T.; Yang, L.; Zeng, X.; Su, P. Technical Requirements for 2023 IMO GHG Strategy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tomasgard, A.; Knudsen, B.R.; Svendsen, H.G.; Bakker, S.J.; Grossmann, I.E. Modelling and analysis of offshore energy hubs. Energy 2022, 261, 125219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Ma, W.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y. A sailing control strategy based on NSGA II algorithm to reduce ship carbon emissions. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2023, 66, 103099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Tsoulakos, N.; Kujala, P.; Hirdaris, S. A deep learning method for the prediction of ship fuel consumption in real operational conditions. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 130, 107425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, C.; Zheng, J.; Chen, L. Quantitative evaluation of China’s shipping decarbonization policies: The PMC-Index approach. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1119663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; He, Y.; Wu, N.; Zhang, F.; Lu, D.; Liu, Z.; Jing, R.; Zhao, Y. Assessment of cruise ship decarbonization potential with alternative fuels based on MILP model and cabin space limitation. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 425, 138667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Kouris, G.D.; Kouris, P.D.; Hensen, E.J.M.; Boot, M.D.; Wu, D. Investigation of the combustion and emissions of lignin-derived aromatic oxygenates in a marine diesel engine. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2021, 15, 1709–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X. Nonlinear control of decarbonization path following underactuated ships. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 272, 113784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Fagerholt, K.; Lindstad, E.; Zhou, J. Pathways towards carbon reduction through technology transition in liner shipping. Marit. Policy Manag. 2023, 52, 417–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Dai, L.; Hu, H.; Zhang, M. An environmental and economic investigation of shipping network configuration considering the maritime emission trading scheme. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2024, 249, 107013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, T.; Wang, N.; Wang, X.; Chen, R.; Li, S. Pilot diesel-ignited ammonia dual fuel low-speed marine engines: A comparative analysis of ammonia premixed and high-pressure spray combustion modes with CFD simulation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 173, 113108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhou, D.; Yang, W.; Qian, Y.; Mao, Y.; Lu, X. Investigation on the potential of using carbon-free ammonia in large two-stroke marine engines by dual-fuel combustion strategy. Energy 2023, 263, 125748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Duan, Y.; Sarkis, J. Supply chain carbon transparency to consumers via blockchain: Does the truth hurt? Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2024, 35, 833–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zis, T.P.V. The enhanced role of canals and route choice due to disruptions in maritime operations. Marit. Bus. Rev. 2024, 9, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zis, T.P.V.; Psaraftis, H.N. Impacts of short-term measures to decarbonize maritime transport on perishable cargoes. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2022, 24, 602–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehurek, R.; Sojka, P. Software Framework for Topic Modelling with Large Corpora. In Proceedings of the LREC 2010 Workshop on New Challenges for NLP Frameworks, Valletta, Malta, 17–23 May 2010; pp. 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, S.; Loper, E. NLTK: The Natural Language Toolkit. In Proceedings of the ACL-02 Workshop on Effective Tools and Methodologies for Teaching Natural Language Processing and Computational Linguistics, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 7 July 2002; pp. 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield, A.; Magnusson, M.; Mimno, D. Pulling out the stops: Rethinking stopword removal for topic models. In Proceedings of the 15th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Valencia, Spain, 3–7 April 2017; pp. 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Boyd-Graber, J.; Gerrish, S.; Wang, C.; Blei, D.M. Reading tea leaves: How humans interpret topic models. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–10 December 2009; Bengio, Y., Schuurmans, D., Lafferty, J.D., Williams, C.K.I., Culotta, A., Eds.; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bouman, E.A.; Lindstad, E.; Rialland, A.I.; Strømman, A.H. State-of-the-art technologies, measures, and potential for reducing GHG emissions from shipping—A review. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2017, 52, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrieu, P.-Y. La Décarbonation des Navires; Editions Maritimes d’Oléron: Saint-Denis d’Oléron, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sievert, C.; Shirley, K.E. LDAvis: A method for visualizing and interpreting topics. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Interactive Language Learning, Visualization, and Interfaces, Baltimore, MD, USA, 27 June 2014; pp. 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddy, M. On Estimation and Selection for Topic Models. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, La Palma, Spain, 21–23 April 2012; pp. 1184–1193. [Google Scholar]

- Hellinger, E. Neue Begründung der Theorie quadratischer Formen von unendlichvielen Veränderlichen. J. Reine Angew. Math. 1909, 136, 210–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaccard, P. Etude de la distribution florale dans une portions des Alpes et du Jura. Bull. Soc. Vaudoise Sci. Nat. 1901, 37, 547–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towards Data Science. Available online: https://medium.com/data-science/visualizing-topic-models-with-scatterpies-and-t-sne-f21f228f7b02 (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- van der Maaten, L.; Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2008, 9, 2579–2605. [Google Scholar]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Syed, S.; Spruit, M. Selecting Priors for Latent Dirichlet Allocation. In Proceedings of the 12th IEEE International Conference on Semantic Computing, Laguna Hills, CA, USA, 31 January–2 February 2018; pp. 194–202. [Google Scholar]

- Comoros, France, Solomon Islands and IWSA. MEPC 81/INF.39 White Paper on Wind Propulsion. Available online: https://www.wind-ship.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/MEPC-81-INF.39-White-paper-on-wind-propulsion-Comoros-France-Solomon-IWSA.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

| Topic Number | λ = 1 | λ = 0.5 | λ = 0 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | perform, oper, port | perform, port, oper | percentag, observ, schedul |

| 2 | hydrogen, fuel, ammonia | hydrogen, fuel, storage | infrastructure, advantage, element |

| 3 | sector, polici, use | sector, polici, climat | country, aviat, freight |

| 4 | energi, fuel, engin | energy, engin, system | heat, load, pump |

| Topic | Title |

|---|---|

| 1 | Operational emission-reduction measures and usage optimisation |

| 2 | Alternative fuel choice and implementation strategies |

| 3 | Emission-reduction policy creation and application |

| 4 | Ship energy system design and management strategies |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reece, L.; Claramunt, C.; Charpentier, J.-F. Mapping Existing Modelling Approaches to Maritime Decarbonisation Using Latent Dirichlet Allocation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10654. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310654

Reece L, Claramunt C, Charpentier J-F. Mapping Existing Modelling Approaches to Maritime Decarbonisation Using Latent Dirichlet Allocation. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10654. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310654

Chicago/Turabian StyleReece, Lily, Christophe Claramunt, and Jean-Frédéric Charpentier. 2025. "Mapping Existing Modelling Approaches to Maritime Decarbonisation Using Latent Dirichlet Allocation" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10654. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310654

APA StyleReece, L., Claramunt, C., & Charpentier, J.-F. (2025). Mapping Existing Modelling Approaches to Maritime Decarbonisation Using Latent Dirichlet Allocation. Sustainability, 17(23), 10654. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310654