Barriers and Enablers to Emergency Preparedness and Service Continuity: A Survey of Australian Community-Based Health and Social Care Organisations

Abstract

1. Introduction

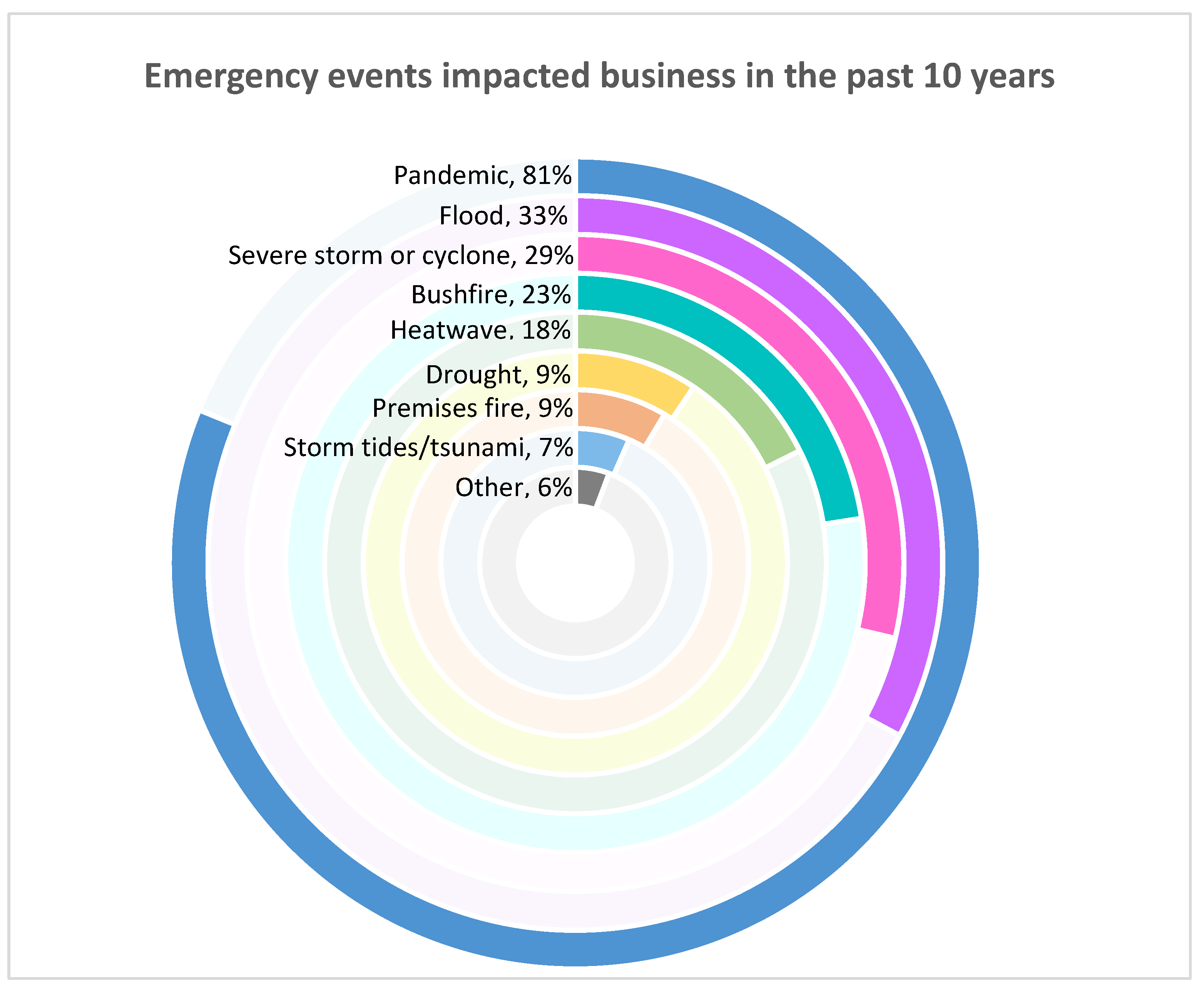

- How have extreme hazard events impacted CBOs’ businesses and their clients in the past ten years?

- What are CBOs’ intentions and capabilities for facilitating personal emergency preparedness with high-risk clients?

- What strategies have CBOs taken to prepare their business for emergencies?

- What organisational characteristics and preparedness strategies are instrumental to service continuity?

- What are the facilitators and barriers to the fulfilment of the aforementioned dual responsibilities?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Questionnaire Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Organisation and Client Profile

3.2. Service Continuity and Clients’ Wellbeing

3.2.1. Infrastructure and Property Damage

3.2.2. Utility and Supply Chain Disruption

3.2.3. Increased Demand for Services and Support

3.2.4. Workforce and Staffing Challenges

3.2.5. Isolated Clients in Need

3.3. Enabling Emergency Preparedness with High-Risk Clients

3.3.1. Emergency Preparedness Is Considered “Out of Scope”

3.3.2. Challenge Engaging with Clients with Cognitive Impairment and People Experiencing Homelessness

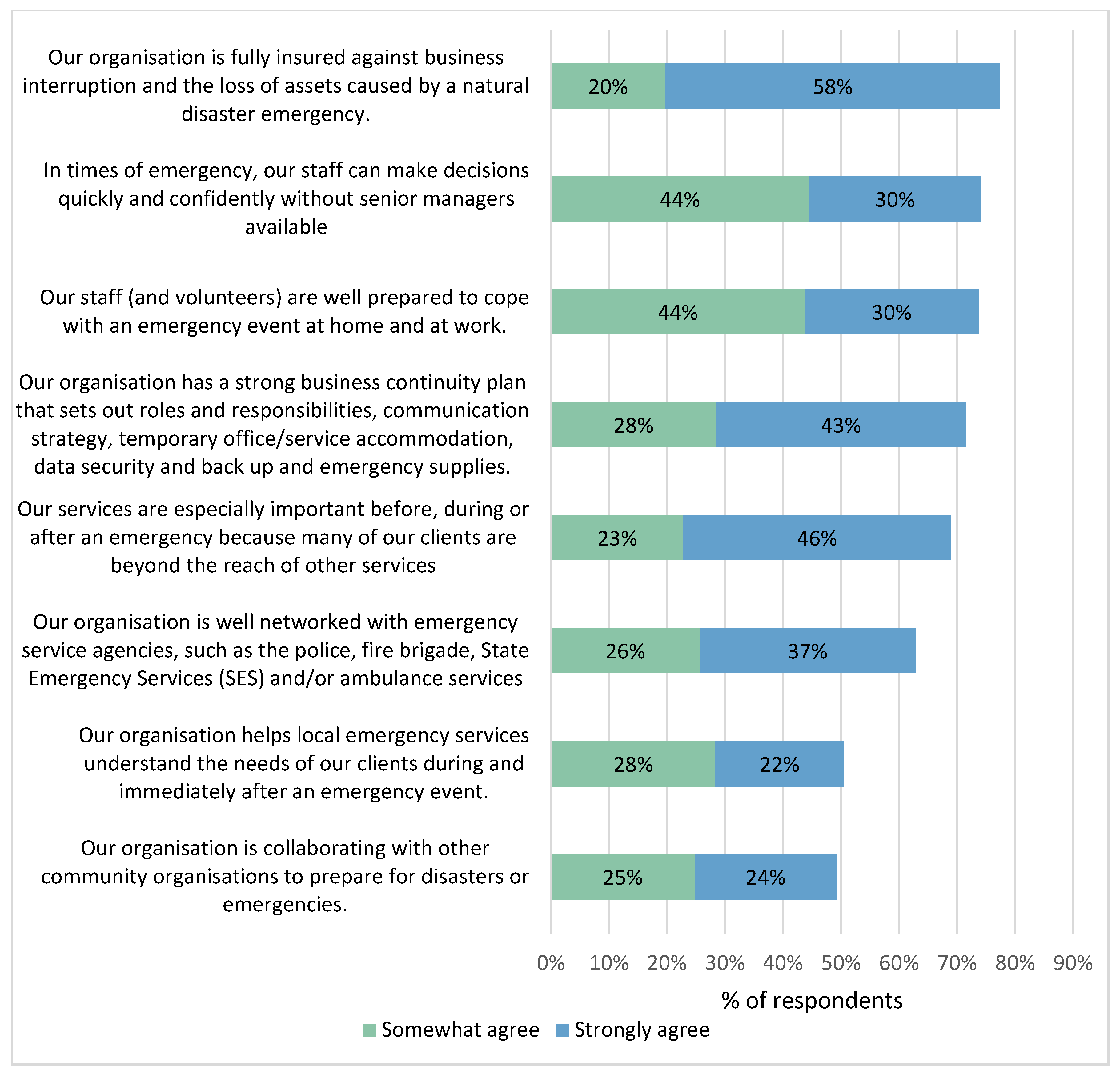

3.4. Factors Influencing Organisational Emergency Preparedness and Business Continuity Planning

3.4.1. Challenges in Planning for a Rapidly Changing Environment

3.4.2. Resource Constraints

3.4.3. Limited Access to Emergency Information and Guidelines

3.4.4. Inadequate Drills and Revisions

3.4.5. Lack of Collaboration with Other Organisations

3.5. Resources Needs for Developing and Implementing Business Continuity Plan

3.5.1. Strengthening Cross-Sector Collaboration and Peer Support

3.5.2. Tailored Training and Leadership Support

3.5.3. Financial Support

3.5.4. Accessible Tools and Templates

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of Emergency Events on Business and Clients

4.2. Organisational Emergency Preparedness to Ensure Service Continuity

4.3. Person-Centred Emergency Preparedness with High-Risk Clients

5. Recommendation

6. Strengths and Limitations

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACOSS | Australian Council of Social Service |

| BCPs | Business Continuity Plans |

| CBOs | Community-based Organisations |

| CSIA | Community Services Industry Alliance |

| DSS | Department of Social Services |

| DIEM | Disability Inclusive Emergency Management |

| MMM | Modified Monash Model |

| NBN | National Broadband Network |

| NDIS | National Disability Insurance Scheme |

| P-CEP | Person-Centered Emergency Preparedness |

| PPE | Personal Protective Equipment |

| RAT | Rapid Antigen Test |

| SESs | State Emergency Services |

| WACOSS | Western Australian Council of Social Services |

References

- Siller, H.; Aydin, N. Using an Intersectional Lens on Vulnerability and Resilience in Minority and/or Marginalized Groups During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Narrative Review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 894103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catholic Organization for Relief and Development Aid. Step-by-Step Guide to Inclusive Resilience. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/publication/step-step-guide-inclusive-resilience (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Ulubasoglu, M. The Unequal Burden of Disasters in Australia. Available online: https://knowledge.aidr.org.au/resources/ajem-october-2020-the-unequal-burden-of-disasters-in-australia/ (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Das, S.; Chatterjee, S.S. Examining and Working Across Differences—Older People from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds in Australia. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, H. Preparedness and Vulnerability: An Issue of Equity in Australian Disaster Situations. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2013, 28, 12–16. Available online: https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/agispt.20132324 (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Cong, Z.; Chen, Z.; Liang, D. Barriers to Preparing for Disasters: Age Differences and Caregiving Responsibilities. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 61, 102338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villeneuve, M. Disability-Inclusive Emergency Planning: Person-Centered Emergency Preparedness. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/publichealth/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190632366.001.0001/acrefore-9780190632366-e-343 (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- UNDRR. Poverty and Inequality as a Risk Driver of Disaster. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/understanding-disaster-risk/risk-drivers/poverty-inequality (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Adedokun, O.; Egbelakin, T.; Sher, W.; Gajendran, T. Investigating Factors Underlying Why Householders Remain in At-Risk Areas during Bushfire Disaster in Australia. Heliyon 2024, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgary, A.; Naeemi, P.; Ganguli, N.; Tofighi, M.; Attarian, K.; Fioretto, T. Road to Resettlement: Understanding Post-Disaster Relocation and Resettlement Challenges and Complexities Through a Serious Game. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2024, 15, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailie, J.; Matthews, V.; Bailie, R.; Villeneuve, M.; Longman, J. Exposure to Risk and Experiences of River Flooding for People with Disability and Carers in Rural Australia: A Cross-Sectional Survey. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e056210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDRR. Exclusion of At-Risk Communities a Major Barrier to Preventing Disaster Losses. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/news/new-report-exclusion-risk-communities-major-barrier-preventing-disaster-losses (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Gershon, R.R.M.; Kraus, L.E.; Raveis, V.H.; Sherman, M.F.; Kailes, J.I. Emergency Preparedness in a Sample of Persons with Disabilities. Am. J. Disaster Med. 2013, 8, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, J.; Hinton, C.F.; Sinclair, L.B.; Silverman, B. Enhancing Individual and Community Disaster Preparedness: Individuals with Disabilities and Others with Access and Functional Needs. Disabil. Health J. 2018, 11, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethel, J.W.; Foreman, A.N.; Burke, S.C. Disaster Preparedness Among Medically Vulnerable Populations. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 40, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, J.; Toal-Sullivan, D.; O’Sullivan, T.L. Household Emergency Preparedness: A Literature Review. J. Community Health 2012, 37, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gissing, A.; George, S. Community Organisation Involvement in Disaster Management. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/publication/community-organisation-involvement-disaster-management (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Victorian Council of Social Services. Building Resilient Communities: Working with the Community Sector to Enhance Emergency Management. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/53200_vcossbuildingresilientcommunities.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Mallon, K.; Hamilton, E.; Black, M.; Beem, B.; Abs, J. Adapting the Community for Climate Extremes: Extreme Weather, Climate Change & the Community Sector—Risks and Adaptations. Available online: https://nccarf.edu.au/adapting-community-sector-climate-extremes-extreme-weather-climate-change-community-sector/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Australian Council of Social Service; Victorian Council of Social Service. Australian National, State and Territory Councils of Social Service—Joint Submission to the Productivity Commission Draft Report into Natural Disaster Funding. Available online: https://assets.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/disaster-funding/submissions/submissions-test2/submission-counter/subdr197-disaster-funding_1.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Community Services Industry Alliance. Planning for Business Continuity in Times of Disaster. Available online: https://collaborating4inclusion.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/CSIA_Business_Continuity_Planning_Facilitation_Guide.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Mercy Corps. Community-Based Organization Disaster Response Preparedness Toolkit. Available online: https://nonprofitoregon.org/resources/community-based-organization-disaster-response-preparedness-toolkit-march-2021/ (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Community Council. Service Continuity Planning Guide for Community-Based Organizations. Available online: https://communitycouncil.ca/service-continuity-planning-guide-for-community-based-organizations-2009/ (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- Subramaniam, P.; Villeneuve, M. Advancing Emergency Preparedness for People with Disabilities and Chronic Health Conditions in the Community: A Scoping Review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 3256–3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Disability Insurance Scheme. Provider Registration and Practice Standards Amendment (2021 Measures No. 1) Rules 2021. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/F2021L01480/latest/text. (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/publication/sendai-framework-disaster-risk-reduction-2015-2030 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- National Emergency Management Agency. Australia’s National Midterm Review of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 Report. Available online: https://www.nema.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-08/Australia%27s%20National%20Midterm%20Review%20of%20the%20Sendai%20Framework%20for%20Disaster%20Risk%20Reduction%202015-2030%20Report.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Colling, R.L.; York, T.W. Emergency Preparedness—Planning and Management. In Hospital and Healthcare Security; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 591–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villeneuve, M. Person-Centred Emergency Preparedness: An Enablement Framework for Service Providers. Available online: https://collaborating4inclusion.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/2021-07-01-research-in-brief-p-cep-enablement-framework.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Zamawe, F. The Implication of Using NVivo Software in Qualitative Data Analysis: Evidence-Based Reflections. Malawi Med. J. 2015, 27, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health, Disability and Ageing. Modified Monash Model. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/rural-health-workforce/classifications/mmm (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Villeneuve, M.; Abson, L.; Pertiwi, P.; Moss, M. Applying a Person-Centred Capability Framework to Inform Targeted Action on Disability Inclusive Disaster Risk Reduction. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 52, 101979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN General Assembly. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Sinha, R.; Ola, A. Enhancing Business Community Disaster Resilience. A Structured Literature Review of the Role of Dynamic Capabilities. Contin. Resil. Rev. 2021, 3, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M.A.; Goldstein, J. The Visiting Nurse Service of New York’s Response to Hurricane Sandy. AJN Am. J. Nurs. 2014, 114, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.R.; Wilson, S.; Brock-Martin, A.; Glover, S.; Svendsen, E.R. The Impact of Disasters on Populations with Health and Health Care Disparities. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2010, 4, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, C.A.; Jansson, D.R. Concepts and Terms for Addressing Disparities in Public Health Emergencies: Accounting for the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Social Determinants of Health in the United States. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2022, 16, 2627–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raker, E.J.; Arcaya, M.C.; Lowe, S.R.; Zacher, M.; Rhodes, J.; Waters, M.C. Mitigating Health Disparities after Natural Disasters: Lessons from the Risk Project. Health Aff. 2020, 39, 2128–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moşteanu, N.R. Adapting to the Unpredictable: Building Resilience for Business Continuity in an Ever-Changing Landscape. Eur. J. Theor. Appl. Sci. 2024, 2, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiBella, J.; Forrest, N.; Burch, S.; Rao-Williams, J.; Ninomiya, S.M.; Hermelingmeier, V.; Chisholm, K. Exploring the Potential of SMEs to Build Individual, Organizational, and Community Resilience through Sustainability-Oriented Business Practices. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2023, 32, 721–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gin, J.L.; Levine, C.A.; Canavan, D.; Dobalian, A. Including Homeless Populations in Disaster Preparedness, Planning, and Response: A Toolkit for Practitioners. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2022, 28, E62–E72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral-Ramírez, M.; Niño-Barrero, Y.; DiBella, J. Lessons from the Implementation of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction from Latin America and the Caribbean. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2025, 16, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyte-Lake, T.; Claver, M.; Johnson-Koenke, R.; Dobalian, A. Home-Based Primary Care’s Role in Supporting the Older Old During Wildfires. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2019, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnard, K.; Bhamra, R. Organisational Resilience: Development of a Conceptual Framework for Organisational Responses. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 49, 5581–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzosa, E.; Judon, K.M.; Gottesman, E.M.; Koufacos, N.S.; Runels, T.; Augustine, M.; Hartmann, C.W.; Boockvar, K.S. Home Health Aides’ Increased Role in Supporting Older Veterans and Primary Healthcare Teams During COVID-19: A Qualitative Analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 1830–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crapis, C.; Chang, K.J.; Villeneuve, M. A Cross-Sectional Survey of Australian Service Providers’ Emergency Preparedness Capabilities. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 46, 4276–4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenendaal, J.; Helsloot, I. Organisational Resilience: Shifting from Planning-Driven Business Continuity Management to Anticipated Improvisation. J. Bus. Contin. Emerg. Plan. 2020, 14, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, R.; Gyllstrom, B.; Gearin, K.; Lange, C.; Hahn, D.; Baldwin, L.M.; Vanraemdonck, L.; Nease, D.; Zahner, S. Identifying Barriers to Collaboration Between Primary Care and Public Health: Experiences at the Local Level. Public Health Rep. 2018, 133, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattanasaeng, S.; Sukhotu, V. Business Continuity Management Deployment, Community Resilience, and Organisational Resilience in Private Industry Response to 2011 Ayutthaya Flooding. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2024, 32, e12627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission. New NDIS Practice Standards and Quality Indicators. Available online: https://www.ndiscommission.gov.au/rules-and-standards/ndis-practice-standards (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Australian Government. About the New Aged Care Act and Key Changes for Providers. Available online: https://www.agedcarequality.gov.au/providers/reform-changes-providers/about-new-aged-care-act-and-key-changes-providers (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- NEMA. Disability Inclusive Emergency Management. Available online: https://www.nema.gov.au/our-work/resilience/diem (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Community Services Industry Alliance. Disaster Management and Recovery Business Continuity and Disaster Management Planning. Available online: https://ncq.org.au/wp-content/uploads/CSIA-Business-Continuity-and-Disaster-Management-Template.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Australian Council of Social Service. Business Continuity Plan. Available online: https://resilience.acoss.org.au/the-six-steps/managing-your-risks/business-continuity-plan (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Western Australian Council of Social Service. Service Continuity Tools & Templates. Available online: https://www.wacoss.org.au/service-continuity-tools/ (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Le Pennec, M.; Raufflet, E. Value Creation in Inter-Organizational Collaboration: An Empirical Study. Source J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 148, 817–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bångsbo, A.; Dunér, A.; Dahlin-Ivanoff, S.; Lidén, E. Barriers for Inter-Organisational Collaboration: What Matters for an Integrated Care Programme? Int. J. Integr. Care 2022, 22, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeshu, P.; Fernando, T.; Therrien, M.-C.; Keraminiyage, K. Inter-Organisational Collaboration Structures and Features to Facilitate Stakeholder Collaboration. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Organisation Profile N (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| State | Service sector * | ||

| Queensland | 95 (39) | Disability | 136 (69) |

| New South Wales | 72 (30) | Housing, homeless | 65 (27) |

| Victoria | 43 (18) | Allied health | 39 (20) |

| Western Australia | 10 (4) | Aged care | 39 (20) |

| South Australia | 10 (4) | Children, youth and family | 30 (15) |

| Australian Capital Territory | 6 (2) | Nursing | 18 (9) |

| Tasmania | 6 (2) | Medical | 8 (4) |

| Northern Territory | 2 (1) | Other | 22 (11) |

| Organisation type | Remoteness † | ||

| Not-for-Profit | 122 (51) | Metropolitan areas | 139 (57) |

| Private | 101 (42) | Regional centres | 39 (16) |

| Public | 16 (7) | Large rural towns | 23 (10) |

| Size of organisation | Medium rural towns | 16 (7) | |

| Micro (<5 employees) | 43 (18) | Small rural towns | 20 (8) |

| Small (5–9 employees) | 63 (26) | Remote communities | 4 (2) |

| Medium (20–199 employees) | 93 (39) | Very remote communities | 1 (0) |

| Large (200 or more employees) | 40 (17) | ||

| Business structure | Service delivery mode | ||

| Company | 113 (47) | Indirect service (e.g., administration, program development) | 9 (4) |

| Incorporated association | 61 (26) | ||

| Sole trader | 24 (10) | Direct service delivery with clients, family or carers | 133 (55) |

| Joint venture | 6 (3) | ||

| Trust | 8 (3) | Combination of direct and indirect service delivery | 98 (40) |

| Partnership | 2 (1) | ||

| Other | 24 (10) | Other | 3 (1) |

| Client profile N (%) | |||

| Main client base * | Client age categories * | ||

| People with disability | 183 (76) | Children (<15) | 126 (52) |

| People with a mental health issue | 85 (35) | Youth (15–24) | 171 (70) |

| People experiencing homelessness | 69 (29) | Adult (25–64) | 217 (89) |

| Families and informal carers | 66 (28) | Elderly (65>) | 134 (55) |

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people | 56 (23) | ||

| Cultural and Linguistic Diversity people | 55 (23) | ||

| People experiencing domestic violence | 54 (23) | ||

| People with problematic drug and/or alcohol use | 32 (13) | Number of active clients | |

| Minimum | 0 | ||

| LGBTQI community | 32 (13) | Maximum | 130,000 |

| Refugees and migrants | 30 (13) | Average | 1307 |

| Other | 29 (12) | ||

| Themes | Indicative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Infrastructure and property damage | “Flood closed roads which prevented staff and clients from getting to the facility”-Nursing service provider, PID-05 “Cyclone damaged multiple buildings-Relocation of offices; stress to both staff and client”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-31 “Breakdown of electrical equipment due to roof leaking, Not being able to cook or use fridges. The impact was on the clients rather than the organisation.”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-38 “Several property fires over the 10 years...Future impact likely to be far greater as insurers are now refusing to insure social housing due to the increased risk.”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-06 “House fire-property was not able to be tenanted for 4 months.”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-21 |

| Utility and Supply Chain Disruptions | “Business continuity impacts due to Wi-Fi and power outages during severe storms in 2021”-Multiple service provider, PID-239 “Electricity was off for five days. We usually have hot summers; this year we had a consistent highest temperature of 40 degrees. Many of our crisis accommodation dwellings do not have air-conditioning. We have supplied portable breeze air, but these do next to nothing during the hottest part of the days.”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-19 “Cyclone isolated clients and staff from access services and work. During this period power as not connected which caused issues who required power to run essential equipment to maintain their health and well-being”-Disability service provider, PID-248 “COVID pandemic caused burden of sourcing PPE / RATs etc”-Disability service provider, PID-443 |

| Increased demand for services and supports | “Increased service requests for provisions of material aid and brokerage, Increased demand on referrals to crisis accommodation and or emergency housing arrangements”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-20 “Increase in client support before and after events to support clients which results in an increase in staff workloads and reduces availability to support clients with usual service delivery.”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-08 “Increased needs for mental health, domestic violence and employment support.”-Multiple service provider, PID-399 “Pandemic has clearly impacted clients’ financial circumstances as level of need for services is higher than ever, with accompanying increases e.g., domestic violence, use of alcohol and other drugs.”-Multiple service provider, PID-415 |

| Workforce and staffing challenges | “Staff being impacted by weather events personally… impacting on their ability to work and support the service/clients…Reduced staffing.”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-08 “Impacted on the ability of the staff to travel to family homes to provide services due to issues such as road closures; unsafe local conditions; public health orders; impact on staff availability due to personal caring responsibilities etc”-Multiple service provider, PID-169 “Pandemic impact has been mostly staff resilience and resulting in 23% turnover in our workforce up from 7%. Unplanned leave also remains high. Overall impact on the organisation is that teams are now greener and less experienced resulting in a drop in outputs and performance measures, decrease in quality, and an increase in risk. Senior managers now less strategic and much more operational which will likely have longer term impact on the future of the business.”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-06 “COVID left us unable to service many of our clients for a considerable time, and on re-entry with mandating vaccinations we lost a considerable amount of employees”-Multiple service provider, PID-434 |

| Isolated clients in need | “Flood and cyclones isolated clients and staff from access services and work. During this period power as not connected which caused issues who required power to run essential equipment to maintain their health and well-being”-Disability service provider, PID-248 “Telehealth is not always appropriate for children, people with intellectual disability or high needs.”-Allied health service provider, PID-30 “Older people and those with disability have been left isolated and frightened, often unable to engage with services due to stigma”-Multiple service provider, PID-444 “People sleeping rough that had no housing to safely stay in especially in high peak of COVID or lockdowns, peoples housing were impacted by floods and left homeless”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-14 “Isolation and deteriorating mental health conditions.”-Neighbourhood centre, PID-410 “Constantly changing Health Order made operational management challenging…. No guarantees that any referral we made could be supported by other organisations as the sector is under strain.”-Multiple service provider, PID-399 |

| Emergency Preparedness Activities with Clients | Done All of This Already | Done Some of This Already | Could Do This in the Future | Could Not Do This |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identify clients who are at risk in an emergency, e.g., chronic, physical and mental health condition affecting mobility, geographical location, barriers to access mainstream sources of information about impending danger (technology, communication and language barrier). | 59% | 34% | 4% | 2% |

| +Assoc.: Organisation size (p = 0.037), have been helping emergency services understand clients’ needs (p = 0.002). −Assoc.: Allied health sector (p = 0.047), omission from organisation’s mission statement (p = 0.011). | ||||

| Make referrals to community services that can help them to enhance their emergency preparedness, e.g., local emergency service personnel and council. | 43% | 34% | 19% | 5% |

| +Assoc.: CALD clients (p < 0.001), have been helping emergency services understand clients’ needs (p < 0.001) | ||||

| Assess clients to identify their level of emergency preparedness, e.g., awareness of local hazard risks, access to emergency information and alerts, understanding their role and responsibility in an emergency. | 32% | 41% | 23% | 4% |

| +Assoc.: Disability service sector (p = 0.009), have been impacted by storm tides/king tides in the past 10 years (p = 0.021), have been helping emergency services understand clients’ needs (p < 0.001) | ||||

| Assess clients to identify their personal strengths and support needs during emergencies to minimise risk, e.g., communication, technology, transport, living situation, personal supports, assistance animals, social connectedness, and health (medical management). | 39% | 38% | 19% | 5% |

| +Assoc.: Public sector (p = 0.012), disability service sector (p = 0.006), have been collaborating with other CBOs to prepare for emergencies (p = 0.019) −Assoc.: Allied health sector (p = 0.025), inadequate training in emergency preparedness (p = 0.037) | ||||

| Provide preparedness information, tools or resources to clients, their families or carers, e.g., information on local bushfire or flood risk, council preparedness resources, community service resources such as the Australian Red Cross emergency preparedness plan. | 29% | 36% | 27% | 9% |

| +Assoc.: Have been helping emergency services understand clients’ needs (p = 0.001) | ||||

| Explore preparedness information, tools, and resources with clients to encourage them to take steps to prepare, e.g., learn about local disaster risks together with your client, recognise gaps in knowledge (yours and theirs), and develop skills to stay informed during an emergency, such as how to find information about bushfires and floods, etc. | 21% | 35% | 35% | 10% |

| −Assoc.: public sector (p = 0.024), Inadequate tools to engage in emergency preparedness with clients (p = 0.007) | ||||

| Develop an emergency preparedness plan for or with clients that is tailored to their support needs in emergencies, e.g., household, or personal emergency checklist and kit, emergency supplies, supported accommodation, and a communication strategy (including contact list). | 29% | 33% | 30% | 8% |

| +Assoc.: Nursing sector (p = 0.002) −Assoc.: Allied health sector (p = 0.010) | ||||

| Strengthen support networks of clients. Build social connectedness to the key people your client will most likely rely on, so that they have a group of willing people to call on to provide support in an emergency, e.g., neighbours, friends, local neighbourhood centres, and a buddy system that pairs people with trusteed local community members who can assist them in an emergency. | 31% | 43% | 16% | 10% |

| +Assoc.: Public sector (p = 0.037), small organisation (p = 0.037), children, youth and family service sector (p = 0.020), have been impacted by drought (p = 0.047) or storm tides/king tides (p = 0.048) in the past 10 years, have been well networked with emergency service agencies (p < 0.001) −Assoc.: Have not been impacted by any hazard events in the past 10 years (p = 0.047), lack of time to include preparedness activities (p = 0.012) | ||||

| Provide formal support or education to clients to increase their active participation in taking steps to prepare for emergencies, e.g., helping them with programs such as the Person-Centred Emergency preparedness (P-CEP) Workbook, and using planning guides such as the Australian Red Cross ‘REDI PLAN’. | 16% | 31% | 39% | 14% |

| −Assoc.: Inadequate tools to engage in emergency preparedness with clients (p = 0.010) | ||||

| Practice emergency drills with clients, their families or carers to increase their familiarity, sense of preparedness and confidence, e.g., evacuating in a wheelchair, with a ventilator, and access to medication and ongoing care. | 20% | 17% | 37% | 26% |

| +Assoc.: Have been impacted by premises fire in the past 10 years (p = 0.012), have been collaborating with other CBOs to prepare for emergencies (p = 0.045) −Assoc.: Allied health sector (p = 0.037), number of clients (p = 0.045), inadequate training in emergency preparedness (p = 0.017), remoteness (p = 0.027) | ||||

| Themes | Indicative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Adopted practices to support high-risk clients’ emergency readiness | |

| Raising emergency awareness and resource sharing | “Wherever possible we educate our tenants about emergency preparedness and last year distributed the Person-Centred Emergency preparedness (P-CEP) booklet to all our Tenants along with general emergency information and emergency supplies. Our staff contacted local councils and made up emergency packs in preparation for the weather period.”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-16 |

| Engaging with clients’ formal and informal support networks | “All our clients have impaired decision making…. our manager keeps in close contact with the clients’ families and supports during any emergency. This has worked well managing the impact of the pandemic.”-Disability service provider, PID-110 “Key to supports are tenants’ informal networks. We therefore seek to house tenants who have lived locally for a long time so that they have this.”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-24 |

| Barriers to engage in emergency preparedness with high-risk clients | |

| Emergency preparedness is considered “out of scope” | “As Plan Managers, we provide administrative supports and have very limited in-person contact”-Disability service provider, PID-67 “Many of our clients are case managed by agencies external to our services. Clients have developed strategies with them”-Disability service provider, PID-103 “I work with clients under the care of parents or carers so do not need to do this as they do”-Disability service provider, PID-286 “We currently work to address the goals of the client. The client’s goal is not to be prepared for an emergency-and if it was, we would identify what barriers they currently have and what to do to get ready.”-Allied health service provider, PID-53 “We operate within contracted deliverables and whilst we encourage clients to have emergency plans…. we do not have resources or the agreement in our contracts to resource this.”-Carer service provider, PID-189 “Most of our clients are short term”-Nursing service provider, PID-05 “We are a “virtual” organisation using Cloud technology. We do not operate from business premises”-Disability service provider, PID-221 |

| Challenge in engaging with clients with cognitive impairment and people experiencing homelessness | “Our clients have complex intellectual disabilities with very limited capacity to comprehend or retain any instructions issued prior to any event. They rely on the training provided to staff due to mobility and other health related issues.”-Disability service provider, PID-131 “Most clients have significant cognitive disability which limits their participation in emergency planning”-Disability service provider, PID-333 “Participants and families have a fear surrounding emergencies and emergency response and prefer to stay at home, in a controlled environment”-Disability service provider, PID-158 “We can have all the planning and processes in place but how we reach out effectively to clients has been most difficult.”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-35 |

| Themes | Indicative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Setting emergency preparedness and business continuity planning as priority | “Our service is required to complete annual seasonal preparedness and to maintain a business continuity plan as part of our department of families, fairness and housing funding. This is a priority for our service.”-Multiple service provider, PID-239 “We have an Emergency and Disaster Management Plan and Policy, Evacuation Plan together with a Risk Management and Business Resilience Policy. Implementation of these Policies and Plans would not provide any great challenges before, during and after a disaster.”-Disability service provider, PID-127 “We do risk assessments for our clients to manage specific emergencies due to their living conditions and abilities…. risk management is part of our normal job. Our coordinators assist our clients to do risk management plans”-Disability service provider, PID-128 |

| Community and peer support | “In the pandemic we lost 80% of our volunteers who deliver our meals to clients, but we received a lot of community help which was great. There were several community organisations that helped regularly for several months.”-Meal service provider, PID-231 “Networking between colleagues also helped as it was specific to our workplace and created continuity within our plans.”-Allied health service provider, PID-249 |

| Government support | “We are funded to provide assistance through the state government when emergencies arise”-Aged care service provider, PID-113 “During COVID 19, we received instructions from government departments, and we follow their guidelines.”-Disability service provider, PID-128 |

| Smooth transition to remote work | “Due to our staff being able to deliver their service remotely (not including face to face meetings) our service is generally uninterrupted by disaster (i.e., COVID).”-Disability service provider, PID-61 “All our office and management staff have the ability to work from home if required. Our data system is all online and support workers also have access to this thru their phones. We are well equipped to deal with business continuity due to a disaster.”-Disability service provider, PID-304 |

| Drawing on previous disaster experience | “As a state-wide service provider with over 40 years in service delivery we have experienced many natural disasters. From this experience we have an understanding of how we continue to provide services.”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-43 “We already have a system of providing alternative workers or contracting out work so direct support to clients can continue with minimal disruption. This has worked effectively during the COVID-19 pandemic.”-Multiple service provider, PID-56 |

| Themes | Indicative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Challenges in planning for a rapidly changing environment | “No idea how to do this, would need support”-Allied health service provider, PID-18 “lack of knowledge or what to include.”-Disability service provider, PID-25 “With a predominately casual staff base, training staff and communicating information to make sure everyone follow the plan in the case of an emergency will be challenging…”-Disability service provider, PID-60 “The challenge is relevant and up to date information and systems that can be accessed 24/7 by appropriate members of staff. Business continuity cost money to ensure that systems are robust and flexible.”-Multiple service provider, PID-70 “There are also infrastructure issues associated with the elderly living in remote areas; there are areas where there is simply no towers to connect via mobile phones. Without communications, we are unable to provide support to our clients at any of these times.”-Multiple service provider, PID-415 |

| Resource constraints | “The main challenge is the resources and time required to prepare a plan based on scenarios of possible high risk situations.”-Disability service provider, PID-205 “Having available staff.... staffing is limited at present and current workload makes it difficult to include additional activities”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-11 “The main challenges for our service is the fact that we run on a very tight budget due to funding not meeting the need of the number of clients we support and house. There is no scope or ability of an already fatigued team to provide more support to additional clients who contact the service in need of help at the time of a disaster.”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-40 “It is challenging to maintain such deep knowledge during periods of high staff turnover and new staff take a very long time before they have the depth of knowledge in the organisational business to respond accordingly.”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-06 “A certificate III in Disability or Aged Care does not produce support staff who are capable of complying with these standards and there is no funding for providers to adequately train the workers.”-Multiple service provider, PID-37 “Staffing with emergency Assessment and planning skills is a major challenge.”-Multiple service provider, PID-243 “Our Housing Programs provided emergency packs-this limited what we could provide in the kits. I believe there should be funds made available to provide basic emergency kits for all Tenants in our program.”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-16 |

| Limited access to emergency information and guidelines | “Not knowing how widespread an area will be affected, how many staff will be affected in ways that may prevent them attending work… Lack of alternative emergency accommodation that meets the basic needs of clients…Capacity of evacuation centres to cope with people living with disability-everything from disability access to being able to manage behaviours of concern in this environment…Lack of community engagement in review of State Emergency Plan and legislation”-Disability service provider, PID-333 |

| Inadequate drills and revisions | “Constructing a plan that covers all potential disasters is very challenging and then having a plan that is not rehearsed can be troublesome.”-Multiple service provider, PID-436 |

| Lack of collaboration with other organisations | “Each organisation wants to remain independent and reluctant to work with others.”-Multiple service provider, PID-21 “As a micro-organisation, we also have limited interaction with emergency services to support the development of a plan that involves these services, therefore our focus has been mainly on staff safety, well-being (as well as their family considerations) and developing an environment where staff can work remotely whilst continuing to deliver supports across robust IT platforms.”-Disability service provider, PID-67 “The local hospital refused our residents during the bushfire disaster. This caused enormous anger and disruption.”-Disability service provider, PID-223 “Our organisation is small and works with several other large providers (e.g., residential disability care) and their decisions directly impact clients and our ability to offer services.”-Disability service provider, PID-461 |

| Themes | Indicative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Strengthening cross-sector collaboration and peer support | “Implementing a strong communication method that could be relied on if essentials services (phone /electricity) were interrupted.”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-37 “Sharing of stories and approaches online would also assist.”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-46 “More education on how to make and implement these plans better and make them user-friendly and not a manual that people do not wish to touch as it’s too daunting a task.”-Multiple service provider, PID-243 “Shared resources and partnerships with local councils around emergency plans”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-7 “More of a focus of the Peak organisations in being able to support organisations to develop and implement BCP’s might assist smaller organisations. Sharing of stories and approaches online would also assist.”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-46 “Emergency Services should be required to factor enabling continuity of services to people with disability into their plans. This would necessitate them knowing the needs of members of various communities and ensuring that these needs can continue to be met.”-Disability service provider, PID-333 |

| Tailored training and leadership support | “Specialist advice from someone who has experience in a range of disasters to overlook the business continuity plan etc to ensure that it somewhat addresses the situation that would arise within the business and community.”-Disability service provider, PID-436 “Training of both front-line staff as well as managers in the basics helps to install confidence that is drawn on through an emergency. Ta basic understanding of the risk, contractual, statutory and legal obligations that are drawn on to make informed but rapid decisions is critical when responding to a crisis.”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-6 “Training to ensure we have covered all basis of the plan; tools to use a guideline and funding to allow the staff and participants to practice an emergency plan.”-Disability service provider, PID-87 “Online training to understand what was required step by step…Feedback & assistance to solve difficult issues.”-Allied health service provider, PID-249 |

| Financial support | “Funding prior to disasters to prepare not after”-Housing and homelessness service provider, PID-14 “Funding for individual assessments with our clientele. Funding for developing resources required and personnel to engage with all appropriate locally based stakeholders that need to be included when developing individualised plans and emergency preparation.”-Disability service provider, PID-08 |

| Accessible tools and templates | “Any easy to use online template for a person-centred emergency preparedness plan would be beneficial as many of our clients may be able to access this themselves.”-Multiple service provider, PID-37 “Some kind of template to ensure that we do not forget an important element”-Disability service provider, PID-66 “We would appreciate there being some resources or tools available from the government departments and emergency services to assist micro-organisations develop stronger business continuity plans.”-Disability service provider, PID-67 “Framework for a good plan would be helpful, to ensure all areas covered”-Multiple service provider, PID-201 “Having access to draft templates that guide the organisation to plan for the most likely scenarios which will affect business continuity. Access to eLearning training packages for staff to increase awareness and underpin practical tasks in disaster preparedness, action and recovery for staff and clients.”-Disability service provider, PID-205 “An off the shelf template of a business continuity plan prefilled that can be amended for individual circumstances or leads the user through the development of the plan with prompters or options to select would be very helpful. For some business the business continuity plan is critical and will be complex, for others like ours which are smaller and only have one or two services could be considered essential and need to continue during an emergency situation, the business continuity plan can be much simpler.”-Multiple service provider, PID-115 |

| Key Findings | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

Most implemented activities:

| |

| |

Most implemented strategy:

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Ensuring service continuity during emergencies | |

Barriers:

| Enablers:

|

| Facilitating person-centred emergency preparedness for high-risk populations | |

Barriers:

| Enablers:

|

| |

| |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, K.-y.J.; Nila, F.H.; Yen, I.; Simpson, B.; Villeneuve, M. Barriers and Enablers to Emergency Preparedness and Service Continuity: A Survey of Australian Community-Based Health and Social Care Organisations. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10649. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310649

Chang K-yJ, Nila FH, Yen I, Simpson B, Villeneuve M. Barriers and Enablers to Emergency Preparedness and Service Continuity: A Survey of Australian Community-Based Health and Social Care Organisations. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10649. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310649

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Kuo-yi Jade, Farhana Haque Nila, Ivy Yen, Bronwyn Simpson, and Michelle Villeneuve. 2025. "Barriers and Enablers to Emergency Preparedness and Service Continuity: A Survey of Australian Community-Based Health and Social Care Organisations" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10649. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310649

APA StyleChang, K.-y. J., Nila, F. H., Yen, I., Simpson, B., & Villeneuve, M. (2025). Barriers and Enablers to Emergency Preparedness and Service Continuity: A Survey of Australian Community-Based Health and Social Care Organisations. Sustainability, 17(23), 10649. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310649