The Intersectional Lens: Unpacking the Socio-Ecological Impacts of Oil Palm Expansion in Rural Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Objective

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Site Selection

3.3. Data Collection and Data Sources

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results and Findings

4.1. Existing Conditions of Oil Palm Expansion in Rural Indonesia: Study in Riau, Central Kalimantan, and West Papua

4.2. Socio-Ecological Impacts and Environmental Justice Distribution

5. Discussion and In-Depth Synthesis

6. Research Implications

7. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ppid.riau. Riau’s Minimum Wage Increases by 8.61 Percent, Manpower and Transmigration Office: Companies Must Pay. ppid.riau.go.id. 2022. Available online: http://ppid.riau.go.id/berita/4805/ump-riau-naik-8-61-persen--kadisnakertrans--perusahan-wajib-bayar (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Mediacenter.riau. Riau’s 2024 Minimum Wage Increases by Rp3,294,625; Mediacenter.riau: Pekanbaru, Indonesia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lahay, S. Palm Oil Plantation Workers Continue to Be Marginalized; Mongabay: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Trisnawati, S. Central Kalimantan’s Minimum Wage to Increase by 8.8 Percent in 2023; Radio Republic Indonesia: Palangkaraya, Indonesia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wiko, S.; Amin, S. “Fraudulent Investment” Exposing the Burdens and Benefits of Palm Oil Investment in Papua. 2024. Available online: https://epistema.or.id/kabar/bodongnya-investasi-sawit-di-papua/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Suryaningsih, A.; Kristanti, D.; Nugroho, T.B. Expansion of Oil Palm Plantations: PT Agrapana Wukir Panca Social, Economic and Environmental Issues (Case Study of Pelalawan District, Riau). J. Soc. Sci. 2023, 4, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliani. Indonesian Palm Oil Workers’ Wages Are Dismal, Malaysia’s Can Reach IDR 17 Million! elaeis.co: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Berenschot, W.; Dhiaulhaq, A.; Hospes, O.; Afrizal; Pranajaya, D. Corporate contentious politics: Palm oil companies and land conflicts in Indonesia. Polit. Geogr. 2024, 114, 103166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efriani, E.; Dewantara, J.A.; Azahra, S.D. Resolving Conflicts between Corporate Cultivation Rights and Indigenous Community Property Rights: A Study of Abandoned Land in Indonesian Palm Oil Plantations. J. Glob. Innov. Agric. Sci. 2024, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

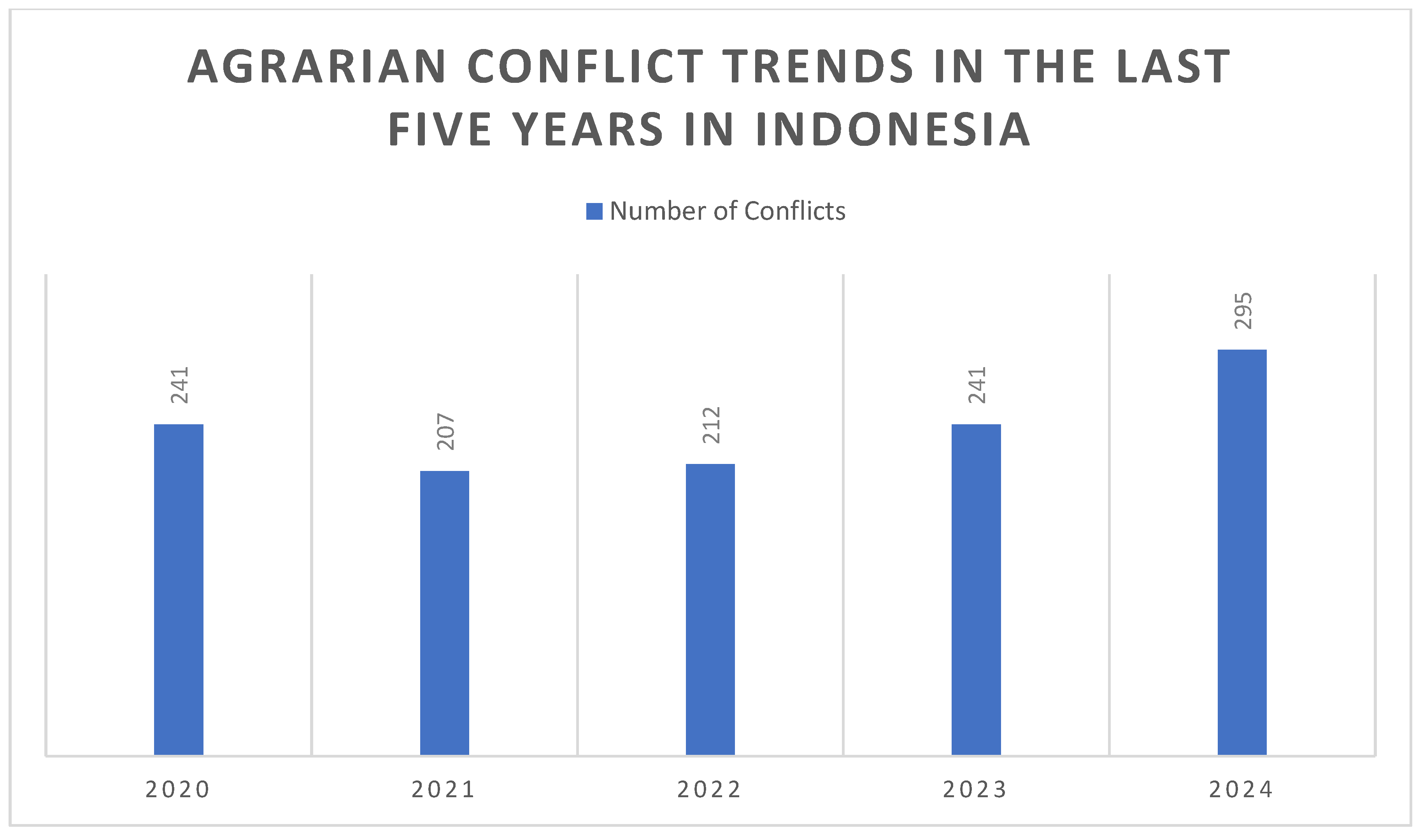

- Agrarian Reform Consortium (KPA). Agrarian Reform Consortium’s 2024 Year-End Notes: Is There Agrarian Reform Under Prabowo’s Command? A Report on Agrarian Conflict and Policy During the Political Transition; Agrarian Reform Consortium (KPA): Jakarta, Indonesia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ayompe, L.M.; Schaafsma, M.; Egoh, B.N. Towards sustainable palm oil production: The positive and negative impacts on ecosystem services and human wellbeing. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisnis.com. West Papua’s 2025 Minimum Wage Set at IDR 3.61 Million; Bisnis.com: Manokwari, Indonesia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cavicchioli, D.; Bertoni, D.; Pretolani, R. Farm succession at a crossroads: The interaction among farm characteristics, labour market conditions, and gender and birth order effects. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 61, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, L. Can Fairy Tales Come True? The Surprising Story of Neoliberalism and World Agriculture. Sociol. Rural. 2010, 50, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMAN. 2024 Year-End Notes Indigenous Peoples Alliance Of The Archipelago Power Transition & The Future Of Indigenous Peoples; AMAN: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Eliminating the Vulnerability of Female Workers to Exploitation in the Palm Oil and Fisheries Sectors; ILO: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Abram, N.K.; Meijaard, E.; Wilson, K.A.; Davis, J.T.; Wells, J.A.; Ancrenaz, M.; Budiharta, S.; Durrant, A.; Fakhruzzi, A.; Runting, R.K. Oil palm–community conflict mapping in Indonesia: A case for better community liaison in planning for development initiatives. Appl. Geogr. 2017, 78, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, A. Palm Oil Plantations Destroy Watersheds in West Papua; Kompas: Jakarta, Indonesia, 3 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- MerdekaPlanet. West Kalimantan Palm Oil Expansion: Are Workers Neglected Amidst Corporate Profits? Planet Merdeka: Petaling Jaya, Malaysia, 2 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Nare, M.; Moopi, P.; Nyambi, O. Global Coloniality and Ecological Injustice in Imbolo Mbue’s How Beautiful We Were (2021). J. Black Stud. 2024, 55, 349–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englert, S. Settlers, Workers, and the Logic of Accumulation by Dispossession. Antipode 2020, 52, 1647–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design; Sage Publication Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- WWF Indonesia. Study on Increasing Indonesian Palm Oil Production; WWF Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Woolf, N.H.; Silver, C. Qualitative Analysis Using NVivo: The Five-Level QDA® Method; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldana, J. Qualitative Data Analysis; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kansanga, M.M.; Bezner Kerr, R.; Lupafya, E.; Dakishoni, L.; Luginaah, I. Does participatory farmer-to-farmer training improve the adoption of sustainable land management practices? Land Use Policy 2021, 108, 105477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widianingsih, I.; Abdillah, A.; Hartoyo, D.; Sartika, S.; Putri, U.; Miftah, A.Z.; Adikancana, Q.M. Increasing Resilience, Sustainable Village Development and Land Use Change in Tarumajaya Village of Indonesia. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Medrilzam, M.; Dargusch, P.; Herbohn, J.; Smith, C. The socio-ecological drivers of forest degradation in part of the tropical peatlands of Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. For. Int. J. For. Res. 2014, 87, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustofa, R.; Syahza, A.; Manurung, G.M.E.; Nasrul, B.; Afrino, R.; Siallagan, E.J. Land tenure conflicts in forest areas: Obstacles to rejuvenation of small-scale oil palm plantations in Indonesia. Int. J. Law Manag. 2025, 67, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmawan, A.H.; Mardiyaningsih, D.I.; Komarudin, H.; Ghazoul, J.; Pacheco, P.; Rahmadian, F. Dynamics of Rural Economy: A Socio-Economic Understanding of Oil Palm Expansion and Landscape Changes in East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Land 2020, 9, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supriatna, J.; Djumarno, D.; Saluy, A.B.; Kurniawan, D. Sustainability Analysis of Smallholder Oil Palm Plantations in Several Provinces in Indonesia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrianto, A.; Komarudin, H.; Pacheco, P. Expansion of Oil Palm Plantations in Indonesia’s Frontier: Problems of Externalities and the Future of Local and Indigenous Communities. Land 2019, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.M. Securing oil palm smallholder livelihoods without more deforestation in Indonesia. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaim, M.; Sibhatu, K.T.; Siregar, H.; Grass, I. Environmental, Economic, and Social Consequences of the Oil Palm Boom. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2020, 12, 321–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affandi, M.I. Oil Palm Plantation Expansion: Changes in Agrarian Structure in Rural Areas; STPN Press: Hemel Hempstead, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Obidzinski, K.; Andriani, R.; Komarudin, H.; Andrianto, A. Environmental and Social Impacts of Oil Palm Plantations and their Implications for Biofuel Production in Indonesia. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, art25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juniyanti, L.; Purnomo, H.; Kartodihardjo, H.; Prasetyo, L.B. Understanding the Driving Forces and Actors of Land Change Due to Forestry and Agricultural Practices in Sumatra and Kalimantan: A Systematic Review. Land 2021, 10, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runtuboi, Y.Y.; Permadi, D.B.; Sahide, M.A.K.; Maryudi, A. Oil Palm Plantations, Forest Conservation and Indigenous Peoples in West Papua Province: What Lies Ahead? For. Soc. 2020, 5, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raharja, S.; Marimin; Machfud; Papilo, P.; Safriyana; Massijaya, M.Y.; Asrol, M.; Darmawan, M.A. Institutional strengthening model of oil palm independent smallholder in Riau and Jambi Provinces, Indonesia. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supriyanto; Arifin, N.; Sulistyowati, H.; Ruliyansyah, A.; Pramulya, M. The Portrait of Agronomic activity of Oil Palm Independent Small Holder in West Kalimantan Province, Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1165, 12028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descals, A.; Szantoi, Z.; Meijaard, E.; Sutikno, H.; Rindanata, G.; Wich, S. Oil Palm (Elaeis guineensis) Mapping with Details: Smallholder versus Industrial Plantations and their Extent in Riau, Sumatra. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuslaini, N.; Maulidiah, S. Governing sustainability: Land use change impact on the palm oil industry in Riau Province, Indonesia. Otoritas J. Ilmu Pemerintah. 2024, 14, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santika, T.; Wilson, K.A.; Meijaard, E.; Budiharta, S.; Law, E.E.; Sabri, M.; Struebig, M.; Ancrenaz, M.; Poh, T.-M. Changing landscapes, livelihoods and village welfare in the context of oil palm development. Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csevár, S.; Rugarli, Y. Greasing the Wheels of Colonialism: Palm Oil Industry in West Papua. Glob. Stud. Q. 2025, 5, ksaf026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariyanti, F.; Syahza, A.; Zulkarnain. Nofrizal Economic transformation based on leading commodities through sustainable development of the oil palm industry. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, H.; Okarda, B.; Dermawan, A.; Ilham, Q.P.; Pacheco, P.; Nurfatriani, F.; Suhendang, E. Reconciling oil palm economic development and environmental conservation in Indonesia: A value chain dynamic approach. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 111, 102089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipenda, C. A Transformative Social Policy Perspective on Land and Agrarian Reform in Zimbabwe. Afr. Spectr. 2024, 59, 89–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossome, L. Gender and development in the agrarian south. World Dev. 2025, 188, 106876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, L.; Luoma, C. Decolonising Conservation Policy: How Colonial Land and Conservation Ideologies Persist and Perpetuate Indigenous Injustices at the Expense of the Environment. Land 2020, 9, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamano, M.A. Indonesian Palm Oil Industry: Environment Risk, Indigenous Peoples, and National Interest. Law Humanit. Q. Rev. 2023, 2, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrizal; Putra, E.V.; Elida, L. Palm oil expansion, insecure land rights, and land-use conflict: A case of palm oil centre of Riau, Indonesia. Land Use Policy 2024, 146, 107325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afentina; McShane, P.; Wright, W. Ethnobotany, rattan agroforestry, and conservation of ecosystem services in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Agrofor. Syst. 2020, 94, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliani, E.L.; de Groot, W.T.; Knippenberg, L.; Bakara, D.O. Forest or oil palm plantation? Interpretation of local responses to the oil palm promises in Kalimantan, Indonesia. Land Use Policy 2020, 96, 104616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, S. Hunger as more-than-human communicative modality on the West Papuan oil palm frontier. Am. Anthropol. 2024, 126, 679–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorn, S.J. Resource extraction as a tool of racism in West Papua. Int. J. Hum. Rights 2023, 27, 994–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirasteh, S.; Mafi-Gholami, D.; Li, H.; Wang, T.; Zenner, E.K.; Nouri-Kamari, A.; Frazier, T.G.; Ghaffarian, S. Social vulnerability: A driving force in amplifying the overall vulnerability of protected areas to natural hazards. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Dong, M.; Yuan, J.; Lam, W.W.T.; Fielding, R. Community vulnerability to the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative synthesis from an ecological perspective. J. Glob. Health 2022, 12, 5054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehn, L.E.; Nelson, L.K.; Samhouri, J.F.; Norman, K.C.; Jacox, M.G.; Cullen, A.C.; Fiechter, J.; Pozo Buil, M.; Levin, P.S. Social-ecological vulnerability of fishing communities to climate change: A U.S. West Coast case study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemke, S.; Claeys, P. Absent Voices: Women and Youth in Communal Land Governance. Reflections on Methods and Process from Exploratory Research in West and East Africa. Land 2020, 9, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, D.; Cely-Santos, M.; Gemmill-Herren, B.; Babin, N.; Bernhart, A.; Bezner Kerr, R.; Blesh, J.; Bowness, E.; Feldman, M.; Gonçalves, A.L.; et al. Food Sovereignty and Rights-Based Approaches Strengthen Food Security and Nutrition Across the Globe: A Systematic Review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 686492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newig, J.; Jager, N.W.; Challies, E.; Kochskämper, E. Does stakeholder participation improve environmental governance? Evidence from a meta-analysis of 305 case studies. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2023, 82, 102705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barger, S.; Vaughan, M.B.; Aiu, C.; Akutagawa, M.K.H.; Beall, E.C.; Luck, J.; Cordy, D.; Maldonado, J. Kīpuka Kuleana: Restoring relationships to place and strengthening climate adaptation through a community-based land trust. Front. Sustain. 2024, 5, 1461787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton Manning, B.; Gould, C.; LaRose, J.; Nelson, M.; Barker, J.; Houck, D.; Steinberg, M. A place to belong: Creating an urban, Indian, women-led land trust in the San Francisco Bay Area. Ecol. Soc. 2023, 28, art8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, I.G. Indigenous communal land titling, the microfinance industry, and agrarian change in Ratanakiri Province, Northeastern Cambodia. J. Peasant Stud. 2024, 51, 267–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notess, L.; Veit, P.; Monterroso, I.; Andiko; Sulle, E.; Larson, A.M.; Gindroz, A.-S.; Quaedvlieg, J.; Williams, A. Community land formalization and company land acquisition procedures: A review of 33 procedures in 15 countries. Land Use Policy 2021, 110, 104461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crook, M.; Short, D.; South, N. Ecocide, genocide, capitalism and colonialism: Consequences for indigenous peoples and glocal ecosystems environments. Theor. Criminol. 2018, 22, 298–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmenta, R.; Cammelli, F.; Dressler, W.; Verbicaro, C.; Zaehringer, J.G. Between a rock and a hard place: The burdens of uncontrolled fire for smallholders across the tropics. World Dev. 2021, 145, 105521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usop, T.B.; Sudaryono, S.; Roychansyah, M.S. Disempowering Traditional Spatial Arrangement of Dayak Community: A Case Study of Tumbang Marikoi Village, Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. For. Soc. 2022, 6, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, N.I.; Rye, S.A. The relational state and local struggles in the mapping of land in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. J. Peasant Stud. 2025, 52, 343–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofi, R.M. Looking at The Legal Philosophy Regarding The Grabbing of Pantai Raja Customary Land. J. USM LAW Rev. 2025, 8, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Febrian, R.A.; Yuza, A.F. Plantation Sector Policy Governance by the Regional Government of Riau Province (Leading Commodities Study). J. Ilm. Peuradeun 2023, 11, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro-Chale, A.; Rivera-Castañeda, P.; Jeanett Ramos-Cavero, M.; Cordova-Buiza, F. Agricultural associations and fair trade in the Peruvian rainforest: A socioeconomic and ecological analysis. Environ. Econ. 2023, 14, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riffel, C. Constitutional Law-making by International Law: The Indigenization of Free Trade Agreements. Eur. J. Int. Law 2024, 35, 445–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, R. Developing a Trade and Indigenous Peoples Chapter for International Trade Agreements. In Indigenous Peoples and International Trade; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 248–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, D. Fair Trade vs. Swaccha Vyāpār: Women’s Activism and Transnational Justice Regimes in Darjeeling, India. Fem. Stud. 2014, 40, 444–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, L.; Molendijk, M.; Porras, N.; Spijkers, P.; Reydon, B.; Morales, J. Fit-For-Purpose Applications in Colombia: Defining Land Boundary Conflicts between Indigenous Sikuani and Neighbouring Settler Farmers. Land 2021, 10, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C.G.; Fry, A.; Libala, N.; Ralekhetla, M.; Mtati, N.; Weaver, M.; Mtintsilana, Z.; Scherman, P.-A. Engaging society and building participatory governance in a rural landscape restoration context. Anthropocene 2022, 37, 100320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, M.-T.; Schilling-Vacaflor, A. Indigenous Peoples and Multiscalar Environmental Governance: The Opening and Closure of Participatory Spaces. Glob. Environ. Polit. 2022, 22, 70–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadich, A.; Moore, L.; Eapen, V. What does it mean to conduct participatory research with Indigenous peoples? A lexical review. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Palm Oil Worker Wages (in IDR) | Minimum Wage 2022 | Minimum Wage 2023 | Minimum Wage 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Riau | Approximately IDR 2.8–3.6 million. Note: many daily/contract workers receive fluctuating incomes (wages per kg of fresh fruit bunches or daily) [7]. | IDR 2,938,564 [1] | IDR 3,191,662 [2] | IDR 3,294,625 [2] |

| Center Kalimantan | Approximately IDR 2.5–3.3 million (indicative; many daily/piecework workers; wages often depend on the piecework/harvest system, so monthly income varies and is sometimes below the minimum wage) [3]. | IDR 2,922,516 [4] | IDR 3,181,013 [4] | IDR 3,261,616 [4] |

| West Papua | Approximately IDR 2.5–3.4 million (indication/estimate; wage conditions in Papua/West Papua tend to vary greatly: some projects/labor providers use outsourcing with very low wages; there are also workers who receive wages close to/above the minimum wage, depending on the company). NGO field reports and investigations show wage vulnerability, outsourcing practices, and cases of violations [5]. | IDR 3,200,000 [12] | IDR 3,282,000 [12] | IDR 3,393,500 [12] |

| No. | Data Resources | References | Brief Relevance | Data Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Document Reports | Agrarian Reform Consortium (KPA). (2024) [10]. Agrarian Reform Consortium’s 2024 Year-End Notes: Is There Agrarian Reform Under Prabowo’s Command? A Report on Agrarian Conflict and Policy During the Political Transition. Retrieved from https://www.kpa.or.id/2025/01/adakah-reforma-agraria-di-bawah-komando-prabowo/ (accessed on 18 September 2025) | Provide critical insights into agrarian reform, indigenous rights, labor exploitation, and sustainability challenges linked to palm oil development. | Institutional reports |

| MAN. (2024) [15]. 2024 Year-End Notes of the Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago: Power Transition & the Future of Indigenous Peoples. Retrieved from https://www.aman.or.id/publication-documentation/304 (accessed on 18 September 2025) | ||||

| International Labour Organization (ILO). (2024) [16]. Eliminating the vulnerability of female workers to exploitation in the palm oil and fisheries sectors. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/resource/news/eliminating-vulnerability-female-workers-exploitation-palm-oil-and (accessed on 18 September 2025) | ||||

| WWF Indonesia. (2023) [24]. Study on Increasing Indonesian Palm Oil Production. Retrieved from http://www.wwf.id/id/blog/peningkatan-produksi-sawit-indonesia-berbasis-tipologi-intensifikasi-dan-ekstensifikasi-kebun (accessed on 18 September 2025) | ||||

| 2. | Government Documents and Website | Ppid Riau. (2022) [1]. Riau’s Minimum Wage Increases by 8.61 Percent, Manpower and Transmigration Office: Companies Must Pay. Retrieved from http://ppid.riau.go.id/berita/4805/ump-riau-naik-8-61-persen--kadisnakertrans--perusahan-wajib-bayar (accessed on 18 September 2025) | Highlight the intersections between labor conditions, wage policies, and palm oil production, which shape the socio-economic dimensions of oil palm expansion in rural Indonesia. | Government documents |

| Media Center Riau. (2023) [2]. Upah Minimum Provinsi Riau 2024 Naik Rp 3.294.625. Retrieved from https://mediacenter.riau.go.id/read/82292/sudah-ditetapkan-ump-riau-2024-naik-sebesar-r.html (accessed on 18 September 2025) | ||||

| 3. | Books | Creswell, J. W. (2007) [22], Woolf, N. H., & Silver, C. (2017) [25], Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2014) [26]. | Provides the methodological foundation for designing and conducting qualitative research to unpack the complex socio-ecological impacts of oil palm expansion. | Methodology |

| 4. | Previous Study | Ayompe, L. M., Schaafsma, M., & Egoh, B. N. (2021) [11]. Towards sustainable palm oil production: The positive and negative impacts on ecosystem services and human wellbeing. Journal of Cleaner Production, 278, 123914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123914 Berenschot, W., Dhiaulhaq, A., Hospes, O., Afrizal, & Pranajaya, D. (2024) [8]. Corporate contentious politics: Palm oil companies and land conflicts in Indonesia. Political Geography, 114, 103166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2024.103166 Busch, L. (2010) [14]. Can Fairy Tales Come True? The Surprising Story of Neoliberalism and World Agriculture. Sociologia Ruralis, 50(4), 331–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2010.00511.x Kansanga, M. M., Bezner Kerr, R., Lupafya, E., Dakishoni, L., & Luginaah, I. (2021) [27]. Does participatory farmer-to-farmer training improve the adoption of sustainable land management practices? Land Use Policy, 108, 105477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105477 Widianingsih, I., Abdillah, A., Hartoyo, D., Putri, S. S. U., Miftah, A. Z., & Adikancana, Q. M. (2024) [28]. Increasing resilience, sustainable village development and land use change in Tarumajaya village of Indonesia. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 31831. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82934-2 | Describe the socio-ecological impacts of palm oil through diverse lenses, ecosystem services and human wellbeing, corporate land conflicts, neoliberal agricultural dynamics, participatory knowledge exchange, and community resilience in land use change, enriching the intersectional analysis of oil palm expansion in rural Indonesia. | Research article |

| 5. | Media | Bisnis.com. (2025) [12]. West Papua’s 2025 Minimum Wage Set at IDR 3.61 Million. Retrieved from https://papua.bisnis.com/read/20241209/415/1822876/ump-2025-papua-barat-ditetapkan-rp361-juta#:~:text=Bisnis.com%2C%20MANOKWARI%20%2D%20Dewan,UMP%202024%20yaitu%20Rp3.393.500 (accessed on 18 September 2025) Trisnawati, S. (2025) [4]. Central Kalimantan’s Minimum Wage to Increase by 8.8 Percent in 2023. Radio Republic Indonesia. Retrieved from https://rri.co.id/daerah/1182755/upah-minimum-provinsi-pekerja-kalteng-naik-6-5-persen (accessed on 18 September 2025) MerdekaPlanet. (2025, May 2) [19]. West Kalimantan Palm Oil Expansion: Are Workers Neglected Amidst Corporate Profits? Planet Merdeka. Retrieved from https://planet.merdeka.com/hot-news/ekspansi-sawit-kalbar-nasib-buruh-terabaikan-di-tengah-keuntungan-korporasi-395131-mvk.html (accessed on 18 September 2025) Wiko, S., & Amin, S. (2024) [5]. “Fraudulent Investment”: Exposing the Burdens and Benefits of Palm Oil Investment in Papua. Retrieved from https://epistema.or.id/kabar/bodongnya-investasi-sawit-di-papua/ (accessed on 18 September 2025) Arif, A. (2024, May 3) [18]. Palm Oil Plantations Destroy Watersheds in West Papua. Kompas. Retrieved from https://www.kompas.id/artikel/perkebunan-kelapa-sawit-terbukti-merusak-daerah-aliran-sungai-di-papua-barat (accessed on 18 September 2025) | Illustrate how wage policies, labor conditions, and contested investment practices intersect with palm oil expansion, revealing both socio-economic vulnerabilities and corporate-driven inequalities in rural Indonesia. | Website |

| Dimension | Riau | Center Kalimantan | West Papua |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access to Land and Resources | The majority of land is controlled by large companies, with a plasma scheme for small farmers. There are many agrarian conflicts related to the conversion of customary forests. | Land is mixed between company concessions and local community ownership; overlapping permits are common. Community access to natural resources is limited, particularly productive land and secondary forests. | The land is still relatively vast, but formal control is in the hands of the state and corporations. Indigenous peoples have lost access to primary forests, rivers, and traditional food sources. |

| Smallholder Production Systems and Institutional Dynamics | Small farmers are bound by plasma patterns, limited autonomy, and dependence on companies. Local institutions are weak, with formal cooperatives rarely functioning optimally. | Smallholder farmers use a hybrid system: partly subsistence, and partly following the palm oil market. Village institutions have begun to regulate the distribution of inputs, but formal regulations are often ignored. | Indigenous farmers still use traditional subsistence systems, but are slowly integrating into the palm oil market system. Local institutions are very limited, with many decisions being made by companies and the provincial government. |

| Socio-Economic Conditions of Rural Communities | Income is relatively more stable due to integration into the palm oil market, but there is a high dependence on companies. Education and health services are moderate, and access to infrastructure is better. | Income is volatile due to dependence on palm oil yields and forest fires. Public services are limited, poverty rates remain high, and labor migration to cities is increasing. | Income is low and unstable, largely dependent on subsistence farming and seasonal work on palm oil plantations. Access to education and health services is very limited. |

| Technology Adoption and Knowledge Systems | Moderate technology adoption: use of fertilizers, pesticides, and modern harvesting techniques on plasma land. Dissemination of knowledge through companies and cooperatives. | Technology adoption varies; small farmers are limited to local knowledge, and the use of fertilizers and traditional tools is still dominant. Local innovations are beginning to emerge, such as crop rotation and controlled burning techniques. | Technology adoption is very low, and traditional practices are dominant. Formal technical knowledge is almost non-existent, and technology transfer is limited. |

| Ecological Transformation | Extensive deforestation, and conversion of primary and secondary forests into monocultures. Water and soil pollution due to palm oil waste. | Loss of secondary forests and peatlands, annual fires, soil degradation, and loss of biodiversity. | Loss of primary forests and rivers, habitat fragmentation, decline in the quality of river and terrestrial ecosystems, and threats to local biodiversity. |

| Narratives and Power Relations | The narrative of palm oil development as economic modernization of villages, but emphasizing corporate dominance. In unequal power relations, small communities are in a subordinate position. | The narrative of development is more mixed: there is talk of community welfare, but implementation is often controlled by companies. Power relations are complex, with negotiations between villages, investors, and the government. | The palm oil narrative is seen as an opportunity for national development, but the marginalization of indigenous peoples is high. Power relations are highly asymmetrical, with companies and the central government dominating decision-making. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mukhlis, M.; Daniswara, N.; Abdillah, A.; Sofiaturrohmah, S. The Intersectional Lens: Unpacking the Socio-Ecological Impacts of Oil Palm Expansion in Rural Indonesia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10570. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310570

Mukhlis M, Daniswara N, Abdillah A, Sofiaturrohmah S. The Intersectional Lens: Unpacking the Socio-Ecological Impacts of Oil Palm Expansion in Rural Indonesia. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10570. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310570

Chicago/Turabian StyleMukhlis, Mukhlis, Nirwasita Daniswara, Abdillah Abdillah, and Siti Sofiaturrohmah. 2025. "The Intersectional Lens: Unpacking the Socio-Ecological Impacts of Oil Palm Expansion in Rural Indonesia" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10570. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310570

APA StyleMukhlis, M., Daniswara, N., Abdillah, A., & Sofiaturrohmah, S. (2025). The Intersectional Lens: Unpacking the Socio-Ecological Impacts of Oil Palm Expansion in Rural Indonesia. Sustainability, 17(23), 10570. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310570